Chartres, about 50 miles southwest of Paris, gives travelers a pleasant break in a lively, midsize town with a thriving, pedestrian-friendly old center. But the big reason to come to Chartres (shar-truh) is to see its famous cathedral—arguably Europe’s best example of pure Gothic.

Chartres’ old church burned to the ground on June 10, 1194. Some of the children who watched its destruction were actually around to help rebuild the cathedral and attend its dedication Mass in 1260. That’s astonishing, considering that other Gothic cathedrals, such as Paris’ Notre-Dame, took literally centuries to build. Having been built so quickly, the cathedral has a unity of architecture, statuary, and stained glass that captures the spirit of the Age of Faith like no other church.

While overshadowed by its cathedral, the town of Chartres also merits exploration. Discover the picnic-perfect park behind the cathedral, check out the colorful pedestrian zone, and wander the quiet alleys and peaceful lanes down to and along the small river.

Chartres is an easy day trip from Paris (even if you leave Paris in the afternoon and return later in the evening). But with its statues glowing in the setting sun—and with hotels and restaurants much less expensive than those in the capital—Chartres also makes a worthwhile overnight stop. If you’ll be here at night, don’t miss the light show—Chartres en Lumières—when dozens of Chartres’ most historic buildings are colorfully illuminated, adding to the town’s after-hours appeal (mid-April-mid-Oct; details at TI). Chartres’ historic center is quiet Sunday and Monday, when most shops are closed.

Chartres is a one-hour ride from Paris’ Gare Montparnasse (14/day, about €16 one-way; see here for Gare Montparnasse details). Jot down return times to Paris before you exit the Chartres train station (last train generally departs Chartres around 21:30).

Upon arrival in Chartres, head for the cathedral. Allow an hour to savor the church on your own as you follow my self-guided tour. But don’t miss the mesmerizing cathedral tour at noon led by Malcolm Miller; also consider the informative tour at 14:45 by Anne-Marie Woods (details on both tours provided later). Take another hour or two to wander the appealing old city. On Saturday and Wednesday mornings, a small outdoor market sets up a few short blocks from the cathedral on Place Billard.

Tourist Information: The TI is in the historic Maison du Saumon building (Mon-Sat 9:30-18:30, Sun 10:00-17:30, closes earlier Nov-April, 10 Rue de la Poissonnerie, tel. 02 37 18 26 26, www.chartres-tourisme.com). It offers specifics on cathedral tours and also rents audioguides for the old town (€5.50, €8.50/double set, about 2 hours). The narration offers little more information than my self-guided walk but is relaxing and easy to follow. Skip the Chartres Pass, which is sold here.

The TI has a small map that shows the floodlit Chartres en Lumières sites, and information on the Petit Train you can take to see them all (check the website or ask at the TI for details).

Arrival in Chartres: Exiting Chartres’ train station, you’ll see the spires of the cathedral dominating the town. It’s a 10-minute walk up Avenue Jehan de Beauce to the cathedral. The free minibus, called the Filibus, runs to near the cathedral (departs 3/hour Mon-Sat 8:30-19:00), or you can take a taxi for about €7.

The last train to Paris usually leaves around 21:30 (verify for your day of travel).

If arriving by car, you’ll have fine views of the cathedral and city as you approach from A-11 autoroute.

Helpful Hints: To get online, head to the TI (free Wi-Fi and guest computer) or try the McDonald’s (free Wi-Fi, Place des Epars). A launderette is a few blocks from the cathedral (by the TI) at 16a Place de la Poissonnerie (daily 7:00-21:00). If you need to call a taxi, try tel. 02 37 36 00 00.

Main Entrance (West Facade), c. 1150

Main Entrance (West Facade), c. 1150

The Rose Windows—North, South, and West

The Rose Windows—North, South, and West

Chapel of Our Lady on the Pillar

Chapel of Our Lady on the Pillar

The Noah Window and Tower Climb

The Noah Window and Tower Climb

South Exterior—Flying Buttresses

South Exterior—Flying Buttresses

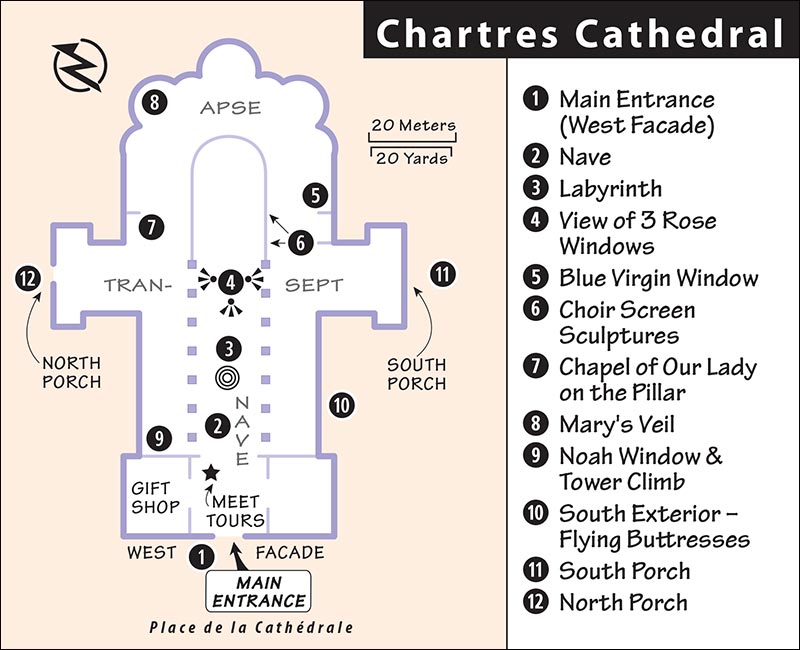

(See “Chartres Cathedral” map, here.)

The church is (at least) the fourth one on this spot dedicated to Mary, the mother of Jesus, who has been venerated here for some 1,700 years. There’s even speculation that the pagan Romans dedicated a temple here to a mother-goddess. In earliest times, Mary was honored next to a natural spring of healing waters (not visible today).

In 876, the church acquired the torn veil (or birthing gown) supposedly worn by Mary when she gave birth to Jesus. The 2,000-year-old veil (now on display) became the focus of worship at the church. By the 11th century, the cult of saints was strong. And Mary, considered the “Queen of All Saints,” was hugely popular. God was enigmatic and scary, but Mary was maternal and accessible, providing a handy go-between for Christians and their Creator. Chartres, a small town of 10,000 with a prized relic, found itself in the big time on the pilgrim circuit.

When the fire of 1194 incinerated the old church, the veil was feared lost. Lo and behold, several days later, townspeople found it miraculously unharmed in the crypt (beneath today’s choir). Whether the veil’s survival was a miracle or a marketing ploy, the people of Chartres were so stoked, they worked like madmen to erect this grand cathedral in which to display it. Thinkers and scholars gathered here, making the small town with its big-city church a leading center of learning in the Middle Ages (until the focus shifted to Paris’ university).

By the way, the church is officially called the Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Chartres. Many travelers think that “Notre-Dame” is in Paris. That’s true. But more than a hundred churches dedicated to Mary—“Notre-Dames”—are scattered around France, and Chartres Cathedral is one of them.

Cost: Free, €5.50 to climb the 300-step north tower (free on first Sun of the month, in the off-season, and for kids under 18).

Hours: Church—daily 8:30-19:30; tower—May-Aug Mon-Sat 9:30-12:30 & 14:00-17:30, Sun 14:00-17:30, Sept-April closes at 16:30 (entrance inside church, after gift shop on left). Mass times vary by season: usually Mon-Fri at 9:00 and/or 11:45; Sat at 11:45 and 18:00; Sun at 9:15 (Gregorian), 11:00, and 18:00 (some services held in the crypt). Confirm times by phone or online—tel. 02 37 21 59 08, www.cathedrale-chartres.org (click “Infos Pratiques,” then “Horaires des Messes”).

Restoration: A multiyear restoration is underway, though you should see few signs of it in 2017.

Tours: Malcolm Miller, a fascinating English scholar who moved here almost 60 years ago when he was 24, has dedicated his life to studying this cathedral and sharing its wonder through his guided lecture tours. He’s slowing down a bit, but his 1.25-hour tours are still riveting even if you’ve taken my self-guided tour. No reservation is needed; just show up with cash (€10, €5 for students, includes headphones that allow him to speak softly, Easter-mid-Oct Mon-Sat at 12:00; no tours last half of Aug, on religious holidays, or if fewer than 12 people show up). Tours begin just inside the church at the Visites de la Cathédrale sign. Consult this sign for changes or cancellations. He also offers private tours (tel. 02 37 28 15 58, millerchartres@aol.com). Miller’s guidebook provides a detailed look at Chartres’ windows, sculpture, and history (sold at cathedral).

Charming American expat Anne-Marie Woods is Malcom Miller’s understudy and is equally passionate about the cathedral. She leads worthwhile 1.5-hour tours of the cathedral that include the vast crypt (daily at 14:45, tel. 02 37 21 75 02, www.cathedrale-chartres.org).

You can rent audioguides inside the cathedral, to the right as you enter. Routes include the cathedral (€4.20, 45 minutes), the choir only (€3.20, 25 minutes), or both (€6.20, 70 minutes). Binoculars are a big help for studying the cathedral art (rent at souvenir shops around the cathedral).

Crypt: Beneath the cathedral are extensive remnants of earlier churches, a modern copy of the old wooden Mary-and-baby statue, an amazing 2,000-year-old well, and frescoes from the 12th and 13th centuries. The only way to see the crypt is on a tour. Anne-Marie Woods’ tour (see above for details) includes the crypt and helps bring it to life, but I’d avoid the more frequent 30-minute tours in French with English handout (€3, 5/day late June-mid-Sept, fewer on Sun and off-season, start at the gift shop inside the cathedral’s north tower, tel. 02 37 21 75 02).

Self-Guided Tour

Self-Guided TourHistorian Malcolm Miller calls Chartres a picture book of the entire Christian story, told through its statues, stained glass, and architecture. In this “Book of Chartres,” the text is the sculpture and windows, and its binding is the architecture. The complete narrative can be read—from Creation to Christ’s birth (north side of church), from Christ and his followers up to the present (south entrance), and then to the end of time, when Christ returns as judge (west entrance). The remarkable cohesiveness of the text and the unity of the architecture are due to the fact that nearly the entire church was rebuilt in just 30 years (a blink of an eye for cathedral building). The cathedral contains the best and most intact library of medieval religious iconography in existence. Most of the windows date from the early 13th century.

The Christian universe is a complex web of heaven and earth, angels and demons, and prophets and martyrs. Much of the medieval symbolism is obscure today. While it’s easy to be overwhelmed by the thousands of things to see, make a point to simply appreciate the perfect harmony of this Gothic masterpiece.

• Start outside, taking in the...

Main Entrance (West Facade), c. 1150

Main Entrance (West Facade), c. 1150Chartres’ soaring (if mismatched) steeples announce to pilgrims that they’ve arrived. For centuries, pilgrims have come here to see holy relics, to honor “Our Lady,” and to feed their souls.

The facade is about the only survivor of the intense, lead-melting fire that incinerated the rest of the church in 1194. The church we see today was rebuilt behind this facade in a single generation (1194-1260).

Compare the towers. The right (south) tower, with a Romanesque stone steeple, survived the fire. The left (north) tower lost its wooden steeple in the fire. In the 1500s, it was topped with the flamboyant Gothic steeple we see today.

The emaciated column-like statues flanking the three west doors are pillars of the faith. These kings of Judah, prophets, and Old Testament big shots foretold the coming of Christ. With solemn gestures and faces, they patiently endure the wait.

What they predicted came to pass. History’s pivotal event is shown above the right door, where Mary (seated) produces Baby Jesus from her loins. This Mary-and-baby sculpture is a 12th-century stone version of an even older wooden statue that burned in 1793. Centuries of pilgrims have visited Chartres to see Mary’s statue, gaze at her veil, and ponder the mystery of how God in heaven became man on earth, as He passed through immaculate Mary like sunlight through stained glass.

Over the central door is Christ in majesty, surrounded by animals symbolizing Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. Over the left door, Christ ascends into heaven after his death and resurrection.

• Enter the church (from a side entrance if the main one is closed) and wait for your pupils to enlarge.

Nave

NaveThe place is huge—the nave is 427 feet long, 20 feet wide, and 120 feet high. Notice the height of the entrance doors compared to the tourists...the doors are 24 feet tall!

The long, tall central nave is lined with 12 pillars. These support pointed, crisscrossed arches on the ceiling, which lace together the heavy stone vaulting. The pillars themselves are supported by flying buttresses on the outside of the church (which we’ll see later). This skeleton structure was the miracle of Gothic design, making it possible to build tall cathedrals with ribbed walls and lots of stained-glass windows (see the big saints in the upper stories of the nave). Chartres has 28,000 square feet of stained glass. The nave—the widest Gothic nave in France—is flanked by raised side aisles. This design was for crowd flow, so pilgrims could circle the church without disturbing worshippers.

Try to picture the church in the Middle Ages—painted in greens, browns, and golds (like colorful St. Aignan Church in the old town, described later in my self-guided walk). It was packed with pilgrims, and was a rough cross between a hostel, a soup kitchen, and a flea market. The floor of the nave slopes in to the center, for easy drainage when hosing down the dirty pilgrims who camped here. Looking around the church, you’ll see stones at the base of the columns smoothed by centuries of tired pilgrim butts. With all the hubbub in the general nave, the choir (screened-off central zone around the high altar) provided a holy place with a more sacred atmosphere.

Taking it all in from the nave, notice that, as was typical in medieval churches, the windows on the darker north side feature Old Testament themes—awaiting the light of Christ’s arrival. And the windows on the brighter south side are New Testament. Regardless of which direction they face, the highest windows—way up in the clerestory—are dark from decades of candle soot. As the ongoing cleaning job proceeds, more of the interior will be bright and sparkling like the apse (area behind the front altar).

• On the floor, midway up the nave, find the...

Labyrinth

LabyrinthThe broad, round labyrinth inlaid in black marble on the floor is a spiritual journey. Labyrinths like this were common in medieval churches. Pilgrims enter from the west rim, by foot or on their knees, and wind around, meditating, on a metaphorical journey to Jerusalem. About 900 feet later, they hope to meet God in the middle. (The chairs are removed on Fridays from Lent to November 1). To let your fingers do the walking, you’ll find a small model of the maze just outside the gift shop, where the tours begin.

• Walk up the nave to where the transept crosses. As you face the altar and gleaming choir, north is to the left.

The Rose Windows—North, South, and West

The Rose Windows—North, South, and WestThe three big, round “rose” (flower-shaped) windows over the entrances receive sunlight at different times of day. All three are predominantly blue and red, but each has different “petals,” and each tells a different part of the Christian story in a kaleidoscope of fragmented images.

Stained glass was created as a way to teach Bible stories to the illiterate medieval masses...who apparently owned state-of-the-art binoculars. The windows were used in many ways—to tell stories, to allow parents to teach children simple lessons, to help theologians explain complex lessons, to enable worshippers to focus on images as they meditated or prayed...and, of course, to light a dark church in a colorful and decorative way.

The brilliantly restored north rose window charts history from the distant past up to the birth of Jesus. On the outer rim, a ring of semicircles, ancient prophets foretell Christ’s coming. Then (circling inward) there’s a ring of red squares with kings who are Jesus’ direct ancestors. Still closer, circles with white doves and winged angels zero in on the central event of history—Mary, the heart of the flower, with her newborn baby, Jesus.

This window was donated by Blanche of Castile, mother of the future King Louis IX (who would build Paris’ stained-glass masterpiece of a church, Sainte-Chapelle). Blanche’s heraldry frames the lower edge of the window: yellow fleur-de-lis on a blue background (for France) and gold castles on a red background (for her home kingdom of Castile).

The south rose window, with a similar overall design, tells how the Old Testament prophecies were fulfilled. Christ sits in the center (dressed in blue, with a red background), setting in motion radiating rings of angels, beasts, and instrument-playing apocalyptic elders who labor to bring history to its close. The five lancet windows below show Mary flanked by four Old Testament prophets (Jeremiah, Isaiah, Ezekiel, and Daniel) lifting New Testament writers (Luke, Matthew, John, and Mark) on their shoulders. (In the first window on the left, see white-robed Luke riding piggyback on dark-robed Jeremiah.) These demonstrated how the ancients prepared the way for Christ—and how the New Testament evangelists had a broader perspective from their lofty perches.

In the center of the west rose window, a dark Christ rings in history’s final Day of Judgment. Around him, winged angels blow their trumpets and the dead rise, face judgment, and are sent to hell or raised to eternal bliss. The frilly edge of this glorious “rose” is flecked with tiny clover-shaped dewdrops.

• Now walk around the altar to the right (south) side and find the window with a big, blue Mary (second one from the right).

The Blue Virgin Window

The Blue Virgin WindowMary, dressed in blue on a rich red background, cradles Jesus, while the dove of the Holy Spirit descends on her. This very old window (mid-12th century) was the central window behind the altar of the church that burned in 1194. It survived and was reinserted into this frame in the new church around 1230. Mary’s glowing dress is an example of the famed “Chartres blue,” a sumptuous color made by mixing cobalt oxide into the glass (before cheaper materials were introduced). The Blue Virgin was one of the most popular stops for pilgrims—especially pregnant ones—of the cult of the Virgin-about-to-give-birth. Devotees prayed, carried stones to repair the church, and donated to the church coffers; Mary rewarded them with peace of mind, easy births, and occasional miracles.

Below Mary (bottom panel), see Christ being tempted by a red-faced, horned, smirking devil.

The Zodiac Window (two windows to the left) shows the 12 signs of the zodiac (in the right half of the window; read from the bottom up—Pisces, Aries, Gemini in the central cloverleaf, Taurus, Cockroach, Leo, Virgo, etc.). On the left side are the corresponding months (February warming himself by a fire, April gathering flowers, and so on).

• Now turn around and look behind you.

The Choir Screen—Life of Mary

The Choir Screen—Life of MaryThe choir (enclosed area around the altar where church officials sat) is the heart (coeur) of the church. A stone screen rings it with 41 statue groups illustrating Mary’s life. Although the Bible says little about the mother of Jesus, legend and lore fleshed out her life. Take some time to learn about the Lady this church is dedicated to.

Scene #1 (south side) shows Mary’s dad hearing the news that Mary is on the way. In #4, Mary is born, and maidens bathe the new baby. In #6, Mary marries Joseph (sculpted with the features of King François I). In scene #7, an angel announces to Mary that she’ll be the mother of the Messiah, and (#10) she gives birth to Jesus in a manger. In #12, the Three Kings—looking like the three musketeers—arrive. In #14, Herod orders all babies slaughtered, but Mary’s son survives to begin his mission.

Next come episodes from the life of Jesus. On the other side of the choir screen, in #27, Jesus is crucified and, in #28, lies lifeless in his mother’s arms. Scene #34 depicts the Ascension, as Jesus takes off, Cape Canaveral-style, while his awestruck followers look up at the bottoms of his rocketing feet. In #39, Mary has died and is raised by angels into heaven, where (#40) she’s crowned Queen of Heaven by the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost.

The plain windows surrounding the choir date from the 1770s, when the dark mystery of medieval stained glass was replaced by the open light of the French Enlightenment. The plain windows and the choir are some of the only “new” features. Most of the 13th-century church has remained intact, despite style changes, revolutionary vandals, and war bombs.

• Do an about-face and find the chapel with Mary on a pillar.

Chapel of Our Lady on the Pillar

Chapel of Our Lady on the PillarA 16th-century statue of Mary and baby—draped in cloth, crowned and sceptered—sits on a 13th-century column in a wonderful carved-wood alcove. This is today’s pilgrimage center, built to keep visitors from clogging up the altar area. Modern pilgrims (including lots of new moms pushing strollers) honor the Virgin by leaving flowers, lighting candles, and kissing the column.

• Double back a bit around the ambulatory, heading toward the back of the church. In the next chapel you encounter (Chapel of the Sacred Heart of Mary), you’ll find a gold frame holding a fragment of Mary’s venerated veil. These days it’s kept—for its safety and preservation—out of the light and behind bulletproof glass.

Mary’s Veil

Mary’s VeilThis veil (or tunic) was supposedly worn by Mary when she gave birth to Jesus. It became the main object of adoration for the cult of the Virgin. The great King of the Franks, Charlemagne (742-814), received the veil as a present from Byzantine Empress Irene. Charlemagne’s grandson gave the veil to Chartres in 876. In 911, with the city surrounded by Vikings, the bishop hoisted the veil like a battle flag and waved it at the invaders. It scared the bejeezus out of them, and the town was saved.

In the frenzy surrounding the fire of 1194, the veil mysteriously disappeared, only to reappear three days later (recalling the Resurrection). This was interpreted by church officials and the townsfolk as a sign from Mary that she wanted a new church, and thus the building began. Recent tests confirm that the material itself, and the weaving technique used to make the cloth, date to the first century A.D., lending support to claims of the relic’s authenticity.

• Return to the west end and find the last window on the right (near the tower entrance).

The Noah Window and Tower Climb

The Noah Window and Tower ClimbRead Chartres’ windows in the medieval style: from bottom to top. In the bottom diamond, God tells Noah he’ll destroy the earth. Next, Noah hefts an axe to build an ark, while his son hauls wood (diamond #2). Two by two, he loads horses (cloverleaf, above left), purple elephants (cloverleaf, right), and other animals. The psychedelic ark sets sail (diamond #3). Waves cover the earth and drown the wicked (two cloverleafs). The ark survives (diamond #4), and Noah releases a dove. Finally, up near the top (diamond #7), a rainbow (symbolizing God’s promise never to bring another flood) arches overhead, God drapes himself over it, and Noah and his family give thanks.

Chartres was a trading center, and its merchant brotherhoods donated money to make 42 of the windows. For 800 years, these panes have publicly thanked their sponsors. In the bottom left is a man making a wheel. More workers are to the right. The panels announce that “these windows are brought to you by...” the wheel-, axe-, and barrelmaking guilds.

• To climb the north tower, find the entrance nearby. Then exit the church (through the main entrance or the door in the south transept) to view its south side.

South Exterior—Flying Buttresses

South Exterior—Flying ButtressesSix flying buttresses (the arches that stick out from the upper walls) push against six pillars lining the nave inside, helping to hold up the heavy stone ceiling and sloped, lead-over-wood roof. The ceiling and roof push down onto the pillars, of course, but also outward (north and south) because of that miracle of Gothic architecture: the pointed arch. The flying buttresses push back, channeling the stress outward to the six vertical buttresses, then down to the ground. The result is a tall cathedral held up by slender pillars buttressed from the outside, allowing the walls to be opened up for stained glass.

The church is built from large blocks of limestone. Peasants trod in hamster-wheel contraptions to raise these blocks into place—a testament to their great faith.

South Porch

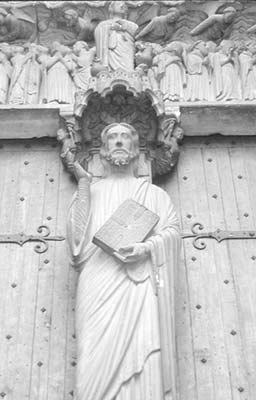

South PorchThe three doorways of the south entrance show the world from Christ’s time to the present, as Christianity triumphs over persecution.

Center Door—Christ and Apostles: Standing between the double doors, Jesus holds a book and raises his arm in blessing. He’s a simple, itinerant, bareheaded, barefoot rabbi, but underneath his feet, he tramples symbols of evil: the dragon and lion. Christ’s face is among the most noble of all Gothic sculpture.

Christ is surrounded by his apostles, who spread the good news to a hostile world. Peter (to the left as you face Jesus), with curly hair and beard, holds the keys to the kingdom of heaven. Paul (to the right of Jesus) fingers the sword of his martyrdom and contemplates the inevitable loss of his head. In fact, all of these apostles were killed or persecuted, and their faces are humble, with sad eyes. But their message prevailed, and under their feet they crush the squirming rulers who once persecuted them.

The final triumph comes above the door in the Last Judgment. Christ sits in judgment, raising his hands, while Mary and John beg him to take it easy on poor humankind. Beneath Christ the souls are judged—the righteous on our left, and the wicked on our right, who are thrown into the fiery jaws of hell. Farther to the right (above the statues of Paul and the apostles), horny demons subject wicked women to an eternity of sexual harassment.

Left Door—Martyrs: Eight martyrs flank the left door. St. Lawrence (second from left) cradles the grill (it looks like a book) on which he was barbecued alive. His last brave words to the Romans were: “You can turn me over—I’m done on this side.” St. George (far right on right flank) wears the knightly uniform of the 1200s, when Chartres was built and King Louis IX was crusading. Depicted beneath the martyrs are gruesome methods of torture, such as George stretched on the wheel. Many of these techniques were actually used in the 1200s by Christians against heretics, Muslims, Jews, and Christian Cathars.

• Reach the north side by circling around the back end of the church. As you walk, enjoy the peaceful park, fine views over the town, and the church’s architecture. Ponder the exoskeletal nature of Gothic design and the ability of medieval faith to mobilize the masses.

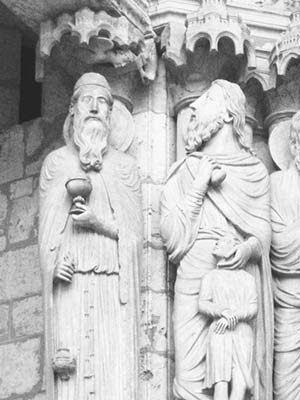

North Porch

North PorchIn the “Book of Chartres,” the north porch is chapter one, from the Creation up to the coming of Christ.

Look between the double doors to see Baby Mary (headless), in the arms of her mother, Anne, marking the end of the Old Testament world and the start of the New.

History begins in the tiny details in the concentric arches over the doorway. God creates Adam (at the peak of the outermost arch, just to the left of the keystone) by cradling his head in his lap like a child.

Next, look at the statues that flank the doors. Melchizedek (farthest to the left of Mary and Anne), with the cap of a king and the cup of communion, is the biblical model of the rex et sacerdos (king-priest), the title bestowed on King Louis IX.

Abraham (next to Melchizedek) holds his son by the throat and raises a knife to slit him for sacrifice. Just then, he hears something and turns his head up to see God’s angel, who stops the bloodshed. The drama of this frozen moment anticipates Renaissance naturalism by 200 years.

John the Baptist (fourth to the right from Mary/Anne), the last Old Testament prophet, who prepared the way for Jesus, holds a lamb, the symbol of Christ. John is skinny from his diet of locusts and honey. His body and beard twist and flicker like a flame.

All these prophets, with their beards turning down the corners of their mouths, have the sad, wise look of having been around since the beginning of time and having seen it all—from Creation to Christ to Apocalypse. Over the door is the culmination of all this history: Christ on his throne, joined by Mary, the Queen of Heaven. These sculptures are some of the last work done on the church, completing the church’s stone-and-glass sermon.

Imagine all this painted and covered with gold leaf in preparation for the dedication ceremonies in 1260, when the Chartres generation could finally stand back and watch as their great-grandchildren, carrying candles, entered the cathedral.

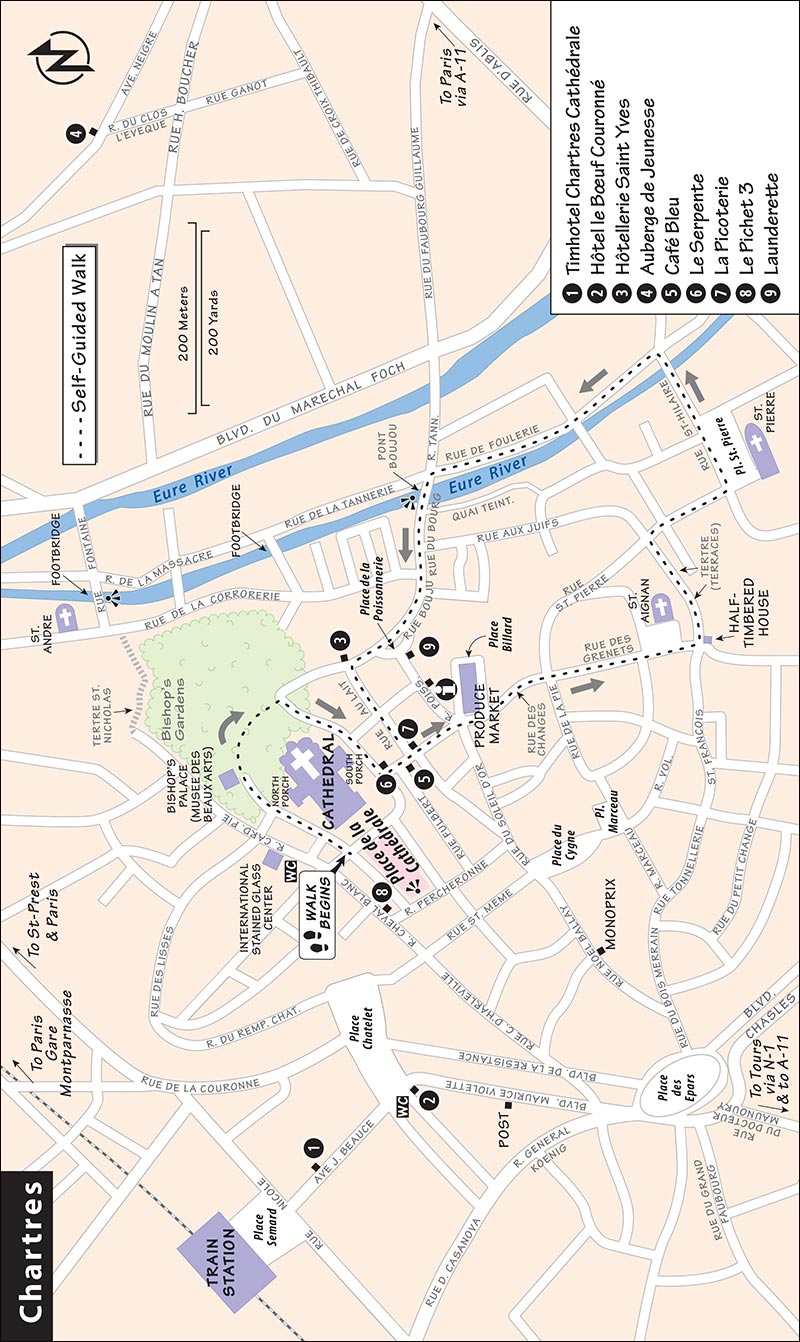

(See “Chartres” map, here.)

Chartres’ old town bustles with activity (except Sun and Mon) and merits exploration. You can rent an audioguide from the TI, or better, just wander (follow the route shown on the map on here).

In medieval times, Chartres was actually two towns—the pilgrims’ town around the cathedral, and the industrial town along the river, which was powered by watermills. This self-guided walk takes you on a 45-minute loop around the cathedral, through the old pilgrims’ town, down along the once-industrial riverbank, and back to the cathedral.

• Begin at the square in front of the church.

Cathedral Close: Around the cathedral was a town within the town. Essentially a precinct run by the church, it was called the “close” of Notre-Dame (cloître Notre-Dame). Looking at the square in front of the church, imagine a walled-in cathedral town with nine gates. It was busy, with a hospital, a school (Chartres was a leading center of education in the 12th century), a bishop’s palace, markets, fairs, and lots of shops—many of them tucked up against the church between its huge buttresses. Chartres was on the medieval map because of the cathedral and its relic. The town was all about the church. For example, in the medieval mind, the foundation of truth was the number three—the Trinity. Nine (three times three) was also a good number. Chartres consisted of three entities—the town, the close, and the church. And each was sure to have nine gates or doors.

About 20 paces in front of the cathedral’s main door, a modern plaque in the pavement points pilgrims to Santiago de Compostela in northwest Spain, home of the tomb of St. James (notice the pilgrim with his walking stick and the stylized scallop shell symbolizing the various routes from all over Europe converging on Santiago). For a thousand years, the faithful have trekked from Paris to Chartres and on to Santiago, a thousand miles away. And for centuries, pilgrims have stoked the economy of Chartres.

• Circle the cathedral clockwise, passing a fine 24-hour clock as you round the corner, and then find the striking carvings of the north porch (described on here). Head under a stately 18th-century wrought-iron gate to the...

Bishop’s Palace and Grounds: The bishop essentially ruled from here until the French Revolution secularized the country. This fine building has housed King Henry IV (here for his coronation), Napoleon, and—since 1939—the city’s Museum of Fine Arts (Musée des Beaux Arts). An ivy-covered arcade, running from near the church to the palace, is all that remains of a covered passageway designed to make the bishop’s commute more pleasant. Stand close to the banister as you survey the lower levels of the bishop’s terraced gardens and enjoy a view of the lower town. From here, you can see why this point has been a strategic choice since ancient times. Beyond the gardens nestles the lower town, which was centered not on the church but on the river, which powered the local industry.

• From the bishop’s garden, continue circling around the cathedral until you reach its south porch (described on here). Turn left onto...

Rue des Changes: This “street of the money changers” runs south from the cathedral. The layout, street names, and building facades of this historic district all date back to a time when businesses catered to the needs of pilgrims rather than tourists. At Rue de la Poissonnerie (where fish were sold), side-trip half a block left, to a fine old half-timbered building called Maison du Saumon (House of Salmon). It dates from about 1500, and as you might guess from the carvings, it faced the former fish market. Today it’s Chartres’ TI.

Back on Rue des Changes, a few more paces brings you to the sky-blue open-air produce market on Place Billard (open Sat and Wed until 13:00). Chartres’ castle stood here until 1802, when it was demolished with revolutionary gusto to make way for the market.

• From here, Rue des Changes turns into Rue des Grenets. For a detour into a bigger-than-you-thought pedestrian zone of shops, colorful lanes, and café-dappled squares, turn right up Rue de la Pie to Place Marceau (the hub of this network) and Rue Noël Ballay (the main shopping drag). Return to Rue des Grenets, and continue walking away from the cathedral.

Rue des Grenets: Farther down the street is the Church of St. Aignan. Squat, crumbling, and lopsided, this is the oldest of Chartres’ parish churches. Remember: Locals didn’t worship in the great cathedral (that was for visitors—like us); they worshipped in the town’s simple parish churches. This one is built upon the tomb of a fourth-century bishop of Chartres (his statue stands in front of the choir). Its interior, dating from about 1625, shows how colorful a stone church could be. The vibrant colors, lavish decoration, and vaulted wood ceiling are astonishing, given the plain exterior. The wood ceiling reminds us that churches could burn.

Continue down Rue des Grenets to a tall, skinny half-timbered house. As the population grew, so did the fire hazard, and the town required half-timbered buildings to be plastered over for safety. Today, the town government—interested in pumping up the touristic charm—pays folks to peel away the plaster and re-expose those timbers. You can see that this building is one of the oldest—the tilting lintel and the asymmetrical windows are dead giveaways.

Turn left at the house and drop down the tertre, a series of stair-step terraces that link the upper and lower towns. The well-worn stone benches along the way evoke a day when washerwomen, laden with freshly washed laundry, rested as they climbed the hill after a trip to the river.

• At the bottom, turn right on Rue St. Pierre, then find the Church of St. Pierre (great photo-op of flying buttresses and a delicate yet decrepit interior). Follow Pont St. Hilaire a block below the church, and—bam!—Eure at the river.

The Eure River: This is another photogenic spot, with old buildings, humpback bridges, and cathedral steeples in the distance. As in nearly any industrial town back then, waterwheels provided power. The river was once lined with busy mills and warehouses. The worst polluters were kept downstream (dyers, tanners, slaughterhouses). The names of the riverside lanes evoke those times: Rue du Massacre, Rue de la Tannerie, and Rue de la Foulerie (named for a process of cleaning wool).

When the industry moved out to make room for Chartres’ growing population, laundry places replaced the old mills. These were two-story structures—the wash cycle downstairs at the river, then the dry cycle upstairs, where vents allowed the wind to blow through. You can still see some of the mechanisms designed to accommodate periodic changes in the river level. The last riverside laundry closed in the 1960s.

• Turn left on Rue de la Foulerie, and follow the river back toward the cathedral. The bridge at Rue du Bourg was once the town’s main bridge. Cross it and climb uphill—you’ll see Queen Bertha’s Staircase (Escalier de la Reine Berthe), a one-of-a-kind half-timbered spiral staircase. Soon after, turn left up the stairs, and you’re back at the cathedral. From here, consider stopping by the...

International Stained Glass Center (Centre International du Vitrail): This low-key center on the north side of cathedral is worth a visit to learn about the techniques behind the mystery of this fragile but enduring art (€6.50, Mon-Fri 9:30-12:30 & 13:30-18:00, Sat 10:00-12:30 & 14:30-18:00, Sun 14:30-18:00, 5 Rue du Cardinal Pie, 50 yards from cathedral, tel. 02 37 21 65 72, www.centre-vitrail.org).

Here you’ll gaze into the eyes of original stained-glass windows from the 12th to the 17th century. The windows you see were gathered from several parish churches around Chartres that were destroyed during the French Revolution. You’ll also see several windows from the nearby churches of St. Aignan and St. Pierre (both described earlier). Finish your visit in the 12th-century vaulted wine cellar to enjoy contemporary windows made using modern techniques.

Panels describe the displays, many of which are original windows from area churches. Ask at the entrance about the 25-minute video in English describing the process of blown glass and the 10-minute French-only video explaining how it is turned into stained glass (easy to follow for non-French speakers). The center also offers five-day classes; call ahead or email for topics and dates.

($$$$ = Splurge, $$$ = Pricier, $$ = Moderate, $ = Budget)

$$ Timhotel Chartres Cathédrale,*** a block up from the train station, is comfortable and well run. Don’t let the facade fool you—inside is a comfy place with a huge fireplace in the lobby and 48 well-kept rooms. Several rooms connect—good for families—and many have partial cathedral views (pricier rooms come with more space and cathedral views, family rooms, good buffet breakfast—extra, but one breakfast per couple free for Rick Steves readers, minibars, air-con, handy and safe pay parking, 6 Avenue Jehan de Beauce, tel. 02 37 21 78 00, www.timhotel.com, chartres@timhotel.fr).

$ Hôtel le Bœuf Couronné*** is more like a vintage two-star hotel, with 17 colorful, good-value rooms and a handy location halfway between the station and cathedral (family rooms, elevator, no air-con, good restaurant with views of the cathedral, reserve ahead for pay parking, 15 Place Châtelet, tel. 02 37 18 06 06, www.leboeufcouronne.com, resa@leboeufcouronne.fr).

$ Hôtellerie Saint Yves, which hangs on the hillside just behind the cathedral, delivers well-priced simplicity with 50 spic-and-span rooms in a renovated monastery with meditative garden areas. Single rooms have no view; ask for a double room with views of the lower town (small bathrooms, good breakfast—extra, 1 Rue Saint Eman, enter via Rue des Acacias, tel. 02 37 88 37 40, www.hotellerie-st-yves.com, contact@hotellerie-st-yves.com).

Hostel: ¢ Auberge de Jeunesse, a 20-minute walk from the historic center, is located in a modern building with good views of the cathedral from its terrace (includes breakfast, dirt cheap meals, 23 Avenue Neigre, tel. 02 37 34 27 64, www.auberge-de-jeunesse-chartres.fr, auberge-jeunesse-chartres@wanadoo.fr).

($$$$ = Splurge, $$$ = Pricier, $$ = Moderate, $ = Budget)

Dining out in Chartres is a good deal—particularly if you’ve come from Paris. Troll the places basking in cathedral views, and if it’s warm, find a terrace table (several possibilities). Then finish your evening cathedral-side, sipping a hot or cold drink at Le Serpente.

$$ Café Bleu offers a great view terrace and an appealing interior. It serves classic French fare at acceptable prices (closed Tue, 1 Cloître Notre-Dame, tel. 02 37 36 59 60).

$$ Le Serpente saddles up next door to the cathedral, with terrific view tables and an adorable collector’s interior. The cuisine is good, basic bistro fare and fairly priced. Simple dishes and to-go food are available from the room at the back (daily, 2 Cloître Notre-Dame, tel. 02 37 21 68 81).

$ La Picoterie serves up a cozy interior and inexpensive fare (omelets, crêpes, salads, and such) with efficient service (daily, 36 Rue des Changes, tel. 02 37 36 14 54).

$$ Le Pichet 3 is run by endearing Marie-Sylvie and Xavier. This local-products shop and cozy bistro make a fun lunch stop. Sit on the quiet street terrace or peruse the artsy inside. Laura serves lots of fresh vegetables and a good selection of plats—try the rabbit with plums (Thu-Tue 11:00-dusk, closed Wed and for dinner off-season, 19 Rue du Cheval Blanc, tel. 02 37 21 08 35).