24

Developing Your Own Recipes

Now it’s time to take off the training wheels and strike out on your own. You have read about many of the various beer styles of the world and you should now have a better idea of the kind of beer you like best and want to brew. Homebrewing is all about brewing your own beer. Recipes are a convenient starting point until you have honed your brewing skills and gained familiarity with the ingredients. Do you need a recipe to make a sandwich? Of course not! You may start out by buying a particular kind of sandwich at a sandwich shop, but soon you will be buying the meat and cheese at the store, cutting back on the mayo a little, giving it a shot of Tabasco, using real mustard instead of that yellow stuff and voila—you have made your own sandwich just the way you like it. Brewing your own beer is the same process.

However, don’t forget to keep a notebook of everything that you do. It would be tragic to brew your best beer ever and then be unable to remember how you made it!

This chapter will present more guidelines for using ingredients to attain a desired characteristic. You want more body, more maltiness, a different hop profile, less alcohol? Each of these can be accomplished and this chapter will show you how.

Recipe Basics

Recipe design is easy and can be a lot of fun. Pull together the information on yeast strains, hops, and malts, and start defining the kind of tastes and characters you are looking for in a beer. Do you want it malty, hoppy, big-bodied, or dry? Choose a style that is close to your dream beer and decide what you want to change about it. Change just one or two things at a time so you will better understand the result. Make sure you understand the signature flavors of the style before you start adding or changing lots of things, otherwise you will probably end up with a beer that just tastes weird. You cannot achieve complexity without balance.

To help get your creative juices flowing, here is a rough approximation of basic recipes for the common ale styles assuming a 5 gal. (19 L) batch:

- pale ale—base malt plus a half-pound (225 g) of caramel malt

- amber ale—pale ale plus another half-pound (225 g) of dark caramel malt

- brown ale—pale ale plus a half-pound (225 g) of chocolate malt

- porter—amber ale plus a half-pound (225 g) of chocolate malt

- stout—porter plus a half-pound (225 g) of roast barley

Yes, those recipes are crude, but I want you to realize how little effort it takes to produce a different beer. When adding a new malt to a recipe, start out with a half-pound or less (≤225 g) for a 5 gal. (19 L) batch. Brew the recipe and then adjust up or down depending on your tastes. Try commercial beers that are available in each style, and use the recipes and guidelines in this book to develop a feel for the flavors the different ingredients contribute.

Read recipes listed in brewing magazines, even if they are all-grain and you are not a grain homebrewer. By reading an all-grain recipe and the descriptions of the malts they are using, you will gain a feel for what that beer would taste like and you will get an idea of the proportions to use. For example, if you look at five different recipes for a regular 5 gal. (19 L) batch of amber ale, you will probably notice that no one uses more than 1 lb. (450 g) of any one crystal malt—all things are good in moderation. If you see an all-grain recipe that sounds good, but aren’t ready to brew all-grain, use the principles given in chapter 4 to duplicate the recipe using extract and specialty grains for steeping. You may need to use a partial mash for some recipes, but most can be reasonably duplicated without.

The first thing you need to understand when designing your own recipes is that the base malt is the main ingredient, just like the bread in a sandwich. The other ingredients all play a supportive role, and should not overwhelm the main ingredient. Just like you don’t want an unbalanced sandwich, you don’t want one aspect to overwhelm the composition of the beer. The whole should be greater than the sum of its parts.

The second thing to understand is that beer styles are like sandwich styles; if you start making a bologna sandwich but use turkey instead, well, that’s a turkey sandwich, isn’t it? In other words, signature ingredients, such as roasted barley, are associated with specific styles, such as stout. You can use a little roasted barley in another recipe, such as a brown ale, but if you use too much, it’s now a stout.

The proportions of the ingredients are very important in a good recipe. The base malt is usually 80%–90% of the grain bill. A signature specialty malt can be 10% of the grain bill, but any other malts should be 5% or less. Now, granted, some porters and stouts will often have five different malts, but simpler is usually better. Too many flavors will start competing with one another and you achieve muddiness instead of complexity. Again, think of a sandwich. A good sandwich will have, at most, three main flavors playing off one another, and one of them is the bread. In beer, you have the base malt, the hop character, and your specialty malts. You can have one specialty malt to provide a signature character for the style, but the other specialty malts should only be complementary accents.

The signature specialty malt in pale styles, such as pale ale and Pilsner, is actually the base malt. You don’t want to crowd it with lots of other specialty malts; instead, you will use specialty malts only as complimentary accents, such as a little bit of Munich for more rich bread character, a little bit of light caramel for enhanced sweetness, or some flaked barley or flaked wheat for more body. As you move into the darker styles, such as brown ales, dunkels, bocks, and porters, the accent specialty malts are used to complement the signature specialty malt, which itself will be a highly toasted malt, a roasted malt, or (rarely) a dark caramel. The complementary malts should share a character of the signature malt, but add a little more variety to the signature flavor, such as adding a bit of smoked malt to the chocolate malt in a porter.

The yeast strain has a big impact on beer flavor. Take any ale recipe and change the ale yeast strain to a lager strain and you have a lager recipe (though not necessarily an example of a particular lager style). Look at information about yeast strains and determine what flavors different strains would give to the recipe. Use the calculations in chapters 4, 5, and 15 to estimate the gravity and IBUs of the beer. Plan the FG for your beer and decide what factors you will manipulate to achieve it, such as ingredients, mash schedule, yeast strain, and fermentation temperature. As the brewer, you have almost infinite control over the end result. Don’t be afraid to experiment.

Don’t get hung up on particular hop varieties for recipes; hops are very easy to substitute. If you are trying to brew a recipe to style but can’t find the hop that it calls for, then substitute a similar hop from the same region (see table 5.3). Try to choose a hop that has similar percentages of alpha acids and aromatic oils, and adjust the quantity and boil time to get the same IBU contribution. The results should be very similar to what’s intended in the original recipe.

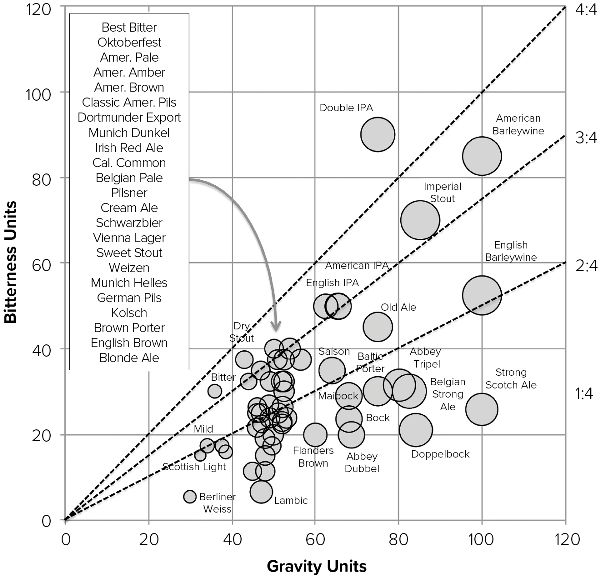

Lastly, keep in mind the balance between bitterness and maltiness in different styles. Maltiness is a complex term that has several facets. First it means malt flavor, the flavors of bread and bread crust that you can smell and taste in fresh malt. Second, maltiness is directly proportional, at least in part, to the strength of the OG. So maltiness can be represented by OG when plotting a chart of flavor balance, as in figure 24.1. It shows how many of the most common styles relate to one another in terms of bitterness and gravity. Most of the smaller styles (lower ABV) group very closely in the 1.040–1.060 OG versus 20–40 IBUs range, at a ratio of 2:4 (or 1:2). American IPA and double IPA are the only styles you see exceeding the 4:4 line (or 1:1).

SMASH and the Single Beer

The acronym SMASH stands for “single malt and single hop,” and it is a good way to focus on the signature flavors of hops and malts. You typically brew a style the way you normally would, but with only a single base malt, no specialty malts, and only a single hop variety used for all hop additions. While SMASH can produce a good beer, and is a great way to teach yourself to recognize specific hop varieties, it generally doesn’t produce an interesting beer.

A good way to explore new ideas and new recipes is a method my friend Drew Beechum calls “brewing on the ones.” The idea is to intentionally restrict yourself to one ingredient per category, so one base malt, one specialty malt, one adjunct (if using), one hop variety for the boil, one hop variety for dry hopping, and so on. It is similar to SMASH, but provides for a more practical level of complexity in a beer. This is because brewing on the ones allows you to round out the beer with a couple of extra ingredients, while maintaining the necessary discretion until you gain sufficient experience to experiment outside the box.

Figure 24.1. OG and %ABV vs Bitterness for Common Beer Styles. This chart shows the mean IBUs versus the mean OG for different beer styles according to the BJCP Style Guidelines. A lot of styles are not shown on this chart, because so many styles overlap in the 20–40 IBU and 1.040–1.060 OG region. The size of the circle indicates the relative % ABV, with the largest representing about 12% ABV and the smallest about 3% ABV. This chart can give you an idea of other beer styles to taste and brew for yourself.

Increasing the Body

Very often, brewers say that they like a beer but wish it had more body. What exactly is “more body”? Is it a physically heavier, denser beer? Does it denote more viscosity, and more flavor? It can mean all those things.

Proteins contribute most of the mouthfeel and body to a beer. Compare an oatmeal stout to a regular stout and you will immediately notice the difference. Brewers refer to these mouthfeel-enhancing proteins as “medium-sized proteins.” During the protein rest, proteolytic enzymes break down large proteins into medium-sized proteins, while peptidases cleave the ends of proteins into small peptides and individual amino acids. High-protein malts and adjuncts, like wheat and oatmeal, can substantially increase the body of the beer.

Increasing the total amount of fermentables in the recipe will increase the body, but will increase the alcohol as well. Unfermentable sugars can enhance the body without increasing the alcohol. Dextrins and other unfermentable sugars are long-chain sugars that cannot be broken down by the mash enzymes or consumed by the yeast. However, the effect of these sugars on mouthfeel is fairly limited, and some brewers suspect that dextrins are a leading cause of “beer farts,” which result when these unfermentable carbohydrates are finally broken down by bacteria in the large intestine.

Dark caramel and roasted malts, such as 80°L and 120°L crystal malt, Special “B,” chocolate malt, and roast barley, contain a high proportion of unfermentable sugars due to Maillard reactions. The total soluble extract (percent by weight) of these malts is close to that of base malt, but just because it’s soluble does not mean it is fermentable. These sugars are only partially fermentable and contribute both a residual sweetness and higher FG to the finished beer that can be perceived as body.

In addition to using the methods above, grain brewers can add dextrin malt, caramel malt, unmalted barley, or oatmeal. Grain brewing lends more flexibility in fine-tuning the wort than extract brewing.

Changing Flavors

What if you want a beer that tastes maltier? A bigger, more robust malt flavor is usually achieved by adding more malt or malt extract to the recipe. A 1.050 OG beer is maltier than a 1.035 OG beer. If you add more extract, be sure to increase the bittering hops proportionally to keep the beer balanced. This brings up another way to enhance the maltiness of a beer, which is to cut back on the flavor and aroma hop additions by 5–10 IBU. You can keep the total hop bitterness and balance the same by adding more bittering hops at the beginning of the boil, but, by cutting back on the middle and late hop additions, the malt flavors and aromas will be more dominant.

But what if you don’t want the increased alcohol level that comes with an increase in gravity? The solution will depend on what flavor profile you are trying to achieve. If you want a toastier malt flavor, substitute a pound or two of a toasted malt (e.g., Vienna, Munich, or amber) in place of some of the base malt to help produce the malty aromas of German bock and Oktoberfest. Change the type of caramel malt you are using if you want to change the sweet malt character of the beer. You can add carastan malt, or 20°L or 40°L caramel malt, in place of a 60°L–80°L caramel malt to produce a lighter, honey-like sweetness, or make use of the bittersweet 120°L caramel and Special “B.”

If the flavor profile tastes a bit flat, or you want to add some complexity to the beer, you can try substituting smaller amounts of a variety of specialty malts in place of a larger single specialty malt addition, while keeping the same OG. For instance, if a recipe calls for 0.5 lb. (225 g) of crystal 60°L malt, try using 0.25 lb. (115 g) each of crystal 40°L and crystal 80°L. For another example, if a recipe calls for 0.5 lb. of chocolate malt, try using just 0.25 lb. of chocolate malt and adding another 0.25 lb. of toasted malt or Caramunich. This will give you more flavors for the same strength beer.

The different growing regions around the world for the hop and malt varieties can also have a significant effect on the character of the beer. Sometimes these differences can be quite dramatic, and it’s a sign of a really good brewer to utilize this. Tasting the ingredients before brewing with them, either by chewing or making a tea from them, is a useful way to teach yourself these differences.

Yeast has a strong effect on beer flavor, and not just by directly contributing yeasty flavors or aromas. The degree of attenuation, the ester profile, and the resultant pH of the beer are all affected by the yeast strain and fermentation conditions, and can accentuate the hops, or the malt character. Some yeast strains add fruity, woody, or earthy notes, or can impart a whiff of spicy phenol. Brewers make the wort, but yeast make the beer.

The best brewers use every little trick: the right malt, the right hops, technique, yeast, temperature, and more, all working together to deliver a unified and memorable experience to the drinker.

Sugars Used in Brewing

Brewing beer is all about working with sugars—glucose, fructose, sucrose, maltose, and all the rest. If you are like me, you want someone to quickly explain it without getting too technical. I will do so, but please be patient because I need to lay some groundwork and describe the different building blocks. It won’t take long, and once you understand what everything’s made of it becomes a lot easier to explain what it means to brewing.

Sugars (technical name: saccharides) are made up of groups of three or more carbon atoms variously bonded to oxygen and hydrogen. The common sugars, like glucose and fructose, consist of a group of six carbon atoms and are therefore called hexoses. A monosaccharide is a single sugar group, a disaccharide is composed of two sugar groups joined together, a trisaccharide is three sugar groups joined together, and so on. Generally, saccharides consisting of many sugar groups joined together are called polysaccharides. Polysaccharides can consist of many thousands of sugar groups joined together in long, often multi-branched, chains.

The most common type of sugar is the monosaccharide glucose, (a.k.a. dextrose or corn sugar). Other monosaccharides relevant to brewing are fructose and galactose. Compositionally, glucose, fructose, and galactose are all the same, but they are isomers of each other. What this means is that, although their basic chemical formula is the same (C6H12O6), the different structural arrangement of each sugar gives them different properties. For instance, fructose (a.k.a. fruit sugar) is an isomer of glucose, but tastes sweeter than glucose.

In general, monosaccharides are sweeter tasting than the other saccharides, although sucrose (a disaccharide) is sweeter than glucose. In descending order of sweetness: fructose is sweeter than sucrose, which is sweeter than glucose, which is sweeter than maltose (disaccharide), which is sweeter than maltotriose (trisaccharide). Not that it really matters in fermentation, I just thought you would like to know.

Lots of different sugars can be used in brewing, but it really begs the question—why would we want to use anything other than the sugars that come naturally from the barley? Well, there are a few reasons:

- To raise the alcohol level without increasing the body of the beer.

- To reduce the body of the beer while maintaining the alcohol level.

- To add some interesting flavors.

- To prime the beer for carbonation.

The first two reasons are two sides of the same coin, of course, but they illustrate two different ways that refined-sugar adjuncts can be used to create different styles of beer. Belgian strong golden ale has an OG of 1.065–1.080 and uses partially refined sugar syrup to achieve a brilliantly clear, light-bodied beer with a high ABV. American light lager recipes have an OG of 1.035–1.050 and use high-maltose corn syrup or rice syrup solids to obtain a very light-bodied beer of average ABV that is perfect for a hot day with the lawn mower.

Different sugars have different flavors. The monosaccharides are usually considered to not have a definable flavor other than “sweet,” although the soda beverage industry seems to promote cane sugar over both beet sugar and high-fructose corn syrup for use in soft drinks. But other natural sugars, like honey and maple syrup, and processed sugars, like molasses, have characteristic flavors that make a nice accent for a beer. This is really what homebrewing is all about—taking a standard beer style and dressing it up for your own tastes. You can make a maple syrup porter, or a honey-raspberry wheat beer, or an imperial Russian stout with hints of rum and treacle. The possibilities are myriad. On the other hand, I have coined a phrase that will serve you well in your experimentation with sugars, “Discretion is the better part of flavor.” A beer with 20% molasses is going to taste like fermented molasses, not beer.

And let’s not forget the topic of priming, which is the addition of 2–3 gravity points of fermentable sugar to carbonate the batch. Most folks do their brewing at the boiling stage—they don’t want to change their flavor profile at the priming stage, they simply want an unobtrusive sugar to carbonate the beer. Other brewers actually look at this last stage of fermentation with an ulterior motive, wanting to add character with this final step. Whatever your goal, you can select one of several sugars to accomplish it (table 24.1).

Pure Glucose

The most common example of a simple brewing sugar is the corn sugar commonly used for priming. Corn sugar is about 92% solids and 8% moisture, with the solid portion consisting of about 99% glucose. Corn sugar is highly refined and does not contain any corn character. Brewers seeking a corn-like character for a classic American Pilsner need to cook and mash corn grits as part of an all-grain recipe. It is known that a relatively high proportion of glucose in a wort (>15%–20%) will inhibit the fermentation of maltose. Fermentation can also be impaired, or become stuck, if the yeast is underpitched or if the wort is lacking in FAN and other nutrients.

High-Maltose Syrups and Solids

There are corn syrups, rice syrups, and syrup solids available that are produced to have high maltose levels, making them more similar to wort than other refined food syrups. Maltose is a disaccharide made from two glucose units joined together. High-maltose corn syrups can be produced from corn in an actual mash or simply by using prepackaged enzymes on corn starch (this process is discussed in more detail in the sidebar on high-fructose corn syrup). The maltose corn syrup usually doesn’t have much, if any, corn character, but this type of product is suitable for brewers wanting to produce a light lager similar to Coors or Miller products.

Rice syrup solids are another maltose product, and there are different types. For example, one high-glucose type is about 75% sugars (50% glucose, 25% maltose), 20% other carbohydrates (dextrins), and 5% moisture. A high-maltose rice syrup solid would typically contain only 5% glucose, the rest being made up of 45% maltose and 45% other carbohydrates, and the same 5% moisture content. Extract brewers seeking to brew a Budweiser clone can use rice syrup solids and will obtain nearly the same malt character as the real thing (assuming that all the other brewing variables are also the same).

Sucrose-Type Sugars

Pure sucrose is the reference standard for all fermentable sugars, because it contributes 100% of its weight as fermentable extract and has zero percent moisture. Sucrose dissolved at 1 lb./gal. will form a solution that has a gravity of 1.046, or, in other words, an extract yield of 46 PPG (which equates to 384 PKL; see also chapter 13).

Lots of different brewing products are made from sucrose or the semi-refined byproducts of sucrose. Both sugar cane and sugar beet are used to make table sugar, and this refined product is indistinguishable whether it comes from cane or beet. However, when considering byproducts, you do not get useful brewing sugars from sugar beet, only sugar cane. Molasses is a common byproduct of sugar cane and is added to refined cane sugar to make brown sugar. The fermentation of molasses produces rum-like notes and sweet flavors, but there may be sharp, harsh notes as well. Brown sugar, which only contains a small amount of molasses, will only contribute a light rummy flavor. Partially refined cane sugars, like piloncillo or panela, demerara sugar, turbinado sugar, and muscovado, have better flavors than molasses, which often contains more impurities from the refining process. Here’s a quote from Sykes and Ling:

The impurities of the raw sugar derived from the beetroot are of a nauseous character, whilst those of sugarcane sugar have an agreeable, full, and luscious flavor; and so much is this the case, that the impure cane sugars are more valuable for brewing purposes than the refined, since the raw variety yield to the beer their luscious flavor. (and Sykes Ling 1907, p. 94)

Invert sugar syrups, such as Lyle’s Golden Syrup, are made from sucrose that has been hydrolyzed to separate the glucose and fructose. This has two effects: one, it makes the sugar more syrupy and less likely to crystallize; and two, it makes it sweeter. Invert sugar syrup is like artificial honey without the characteristic honey flavors. Golden syrup-type products tend to be a bit salty tasting due to the acid–base reactions that occur during manufacture. Treacle is partially inverted molasses combined with other syrups. The flavor contributions from treacle can be strong, so it is best to use it in heavier bodied beers like English strong ales, porters, and sweet stout. A recommended starting point for strongly flavored syrups is 8 fl. oz. (250 mL) per 5 gal. (19 L) batch.

Belgian candi syrups are a class of adjunct that originated in England in the early to mid-1700s, due to the high cost of sugar. These syrups were created from the remnants left in the kettle of boiling sugar into hard candy; the kettles were cleaned by pouring hot water onto the hot residue stuck to the bottom of the kettle and the resulting candi syrups were either incorporated into the next batch or stored for aftermarket sale. This syrup was money. Eventually sugar prices dropped with the advent of large sugar plantations in the New World, and the subsequent rise in sugar use and candy production led to greater availability of these syrups.

The candi syrups darkened due to Maillard reactions and developed a variety of unique flavors depending their origin and the length of time spent cooking in the kettle. These syrups became very popular coloring and flavoring adjuncts for British brewers, and this brewing practice spread to Belgium by the late 1800s. Today, these candi syrups are specifically produced for brewing and are available in several colors (degrees Lovibond), such as 5°L, 45°L, 90°L, 180°L, and 240°L. The lightest colors have flavors reminiscent of honey, light citrus, and golden raisins. The medium colors (45°L and 90°L) have caramel, toffee, vanilla, chocolate, and stone fruit flavors. The darkest colors have dark caramel, dark chocolate, coffee, and stone fruit flavors. Candi syrups are typically used at a rate of 1–3 lb. (0.5–1.4 kg) per 5 gal. (19 L) batch, depending on the style being made, and typically contribute about 32 PPG (267 PKL).

Maple Syrup

The sap from maple trees typically contains about 2% sucrose. Maple syrup is standardized at a minimum of 66 degrees Brix,1 and is typically composed of ≥95% sucrose. Grade B maple syrup can contain 6% invert sugar, while Grade A Light Amber will contain less than 1%. You will get more maple flavor from the Grade B syrup. The characteristic maple flavors tend to be lost during primary fermentation, so to retain as much flavor as possible it is recommended that the syrup is added after primary fermentation is over. This practice will also help the beer to ferment more completely, because it will not trigger inhibition of maltose fermentation as discussed in chapter 6. For a noticeable maple flavor, 1 gal. (3.8 L) of Grade B syrup is recommended per 5 gal. (19 L) batch.

Table 24.1—Common Brewing Sugars

| Sugar | PPG (PKL) | Fermentabilty | Constituents | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Corn sugar |

42 (351) |

100% |

Glucose (~8% moisture) |

Can be used for priming, or as a wort component to increase the alcohol while lightening the body of the beer. |

|

Rice syrup solids |

42 (351) |

Varies by grade, high-glucose grade is ~80% |

Glucose, maltose, other (~10% moisture) |

Can be used for priming, or as a wort component to increase the alcohol while lightening the body of the beer. |

|

Table sugar |

46 (384) |

100% |

Sucrose |

Can be used for priming, or as a wort component to increase the alcohol while lightening the body of the beer. |

|

Lyles Golden Syrup |

38 (317) |

100% |

Glucose, fructose (18% water) |

An invert sugar that has been broken down to fructose and glucose. A bit salty due to acids and bases used during processing. |

|

Belgian candi syrup |

32 (267) |

Varies ~50%–80% |

Sucrose, melanoidins |

Variety of color and flavor products. Key ingredient for many Belgian ale styles. |

|

Molasses / Treacle |

36 (300) |

Varies, ~50%–70% |

Sucrose, invert sugars, dextrins |

Composition varies, therefore degree of fermentability varies, probably around 50%–70%. Can cause rumlike or winelike flavors. |

|

Lactose |

46 (384) |

… |

Lactose (<1% moisture) |

Lactose is an unfermentable sugar—a disaccharide of glucose and galactose. Used in milk stouts to impart a smooth, sweet flavor. |

|

Honey |

38 (317) |

95% |

Fructose, glucose, sucrose (~18% water) |

Honey is a mixture of sugars high in fructose. Will impart honey-like flavors that depend on nectar source. |

|

Maple syrup |

31 (259) |

100% |

Sucrose, fructose, glucose (~34% water) |

Maple syrup is mostly sucrose. Grade B syrup will provide more maple flavor than Grade A syrup. |

|

Maltodextrin (powder) |

42 (351) |

… |

Dextrins (5% moisture) |

Maltodextrin powder contains a small amount of maltose, but is mostly unfermentable. Adds mouthfeel and some body. |

Notes: The extract yield of sucrose-based brewing syrups can be estimated by multiplying the percent solids (i.e., the inverse of percent moisture) or degrees Brix by the reference standard for sucrose, which is 46 PPG. The extract of powdered sugars can be estimated by subtracting the percent moisture and multiplying the remainder by 46 PPG.

Honey

Honey is about 18% water by weight. The other 82% is carbohydrates. Ninety-five percent of those carbohydrates are fermentable, typically consisting of 38% fructose, 31% glucose, 8% various disaccharides, and 4% unfermentable dextrins by weight. Honey contains wild yeast strains and bacteria, but its low water content keeps these microorganisms dormant. Honey also contains amylase enzyme, which can break down unfermentable sugars in the wort into highly fermentable sugars like maltose and sucrose. For these reasons, honey should be pasteurized before adding it to the fermentor. The National Honey Board (www.nhb.org) recommends that honey be pasteurized for 30 min. at 176°F (80°C), then cooled and diluted to the wort gravity. To retain the most honey flavor, and ensure best fermentation performance, the honey should be added to the fermentor after primary fermentation.

The NHB recommends the following percentages (by weight of total fermentables in the wort) when brewing with honey:

|

3%–10% |

This gives a subtle honey flavor in most light ales and lagers. |

|

11%–30% |

This allows a distinct honey flavor note to develop. Stronger hop flavors, caramelized or roasted malts, spices, or other ingredients should be considered when formulating the recipe to balance the strong honey flavors at this level. |

|

30%–66% |

The flavor of honey will dominate the beer. This range is associated with braggot, which is considered by the BJCP Style Guidelines2 to have a maximum honey-to-malt ratio of 2:1. |

|

>66% |

Any brew with more than 66% honey is considered to be a form of mead, according to the BJCP. |

Toasting Your Own Malt

As a homebrewer, you should feel free to experiment in your kitchen with malts. Oven-toasted base malt adds nutty and toasty flavors to the beer, which is a nice addition for brown ales, porters, bocks, and Oktoberfest beers. It is easy to toast-your-own, and the toasted grain can be used by both steeping and mashing. If steeped, the malt will contribute a high proportion of unconverted starch to the wort and the beer will be hazy, but a nice nutty, toasted flavor will be evident in the final beer. There are several combinations of time and temperature that can be used in producing these malts (table 24.2).

The principal reaction that takes place when you toast malt is the browning of starches and proteins, known as Maillard reactions. As the starches and proteins brown, various flavor and color compounds are produced. The color compounds are called “melanoidins,” which can improve the flavor stability of beer by slowing oxidation and staling reactions as the beer ages.

Since the Maillard reactions are influenced by the wetness of the grain, water can be used in conjunction with the toasting process to produce different flavors in the malt. Soaking the uncrushed malt in water for an hour will provide the water necessary to optimize the Maillard browning reactions. Toasting wet malt will produce more of a caramel flavor due to partial starch conversion taking place caused by the heat. Toasting dry grain will produce more of a toast or Grape-Nuts® cereal flavor that is perfect for nut-brown ales.

The toasted malt should be stored in a paper bag for two weeks prior to use. This will allow time for the harsher aromatics to escape. Commercial toasted malts are often aged for six weeks before sale. This aging is more important for the highly toasted malts, those that are toasted for more than 30 min. (dry) or 60 min. (wet).

Table 24.2—Grain Toasting Times and Temperatures

| Oven temp. | Dry/Wet | Time | Flavors |

|---|---|---|---|

|

275°F (140°C) |

Dry |

60 min. |

Light nutty taste and aroma. |

|

350°F (180°C) |

Dry |

15 min. |

Light nutty taste and aroma. |

|

350°F (180°C) |

Dry |

30 min. |

Toasty, Grape-Nuts® cereal flavor. |

|

350°F (180°C) |

Dry |

60 min. |

More roasted flavor, very similar to commercial brown malt. Can be harsh. |

|

350°F (180°C) |

Wet |

60 min. |

Light sweet toasty flavor. |

|

350°F (180°C) |

Wet |

90 min. |

Toasty, malty, slightly sweet. |

|

350°F (180°C) |

Wet |

120 min. |

Strong toasted/roasted flavor similar to brown malt, but slightly sweet. |

Discretion Is the Better Part of Flavor

There comes a time in every homebrewer’s development when they look at an item (e.g., maple syrup, molasses, Cheerios®, chile peppers, potatoes, pumpkins, loquat fruit, ginger root, spruce tips, heather, licorice, stale bread, mismatched socks) and say, “Hey, I could ferment that!” While many of the mentioned items will indeed work in the fermentor (socks work well for dry-hopping), it is easy to get carried away and make something that no one really wants to drink a second glass of. I thought I would like spiced holiday beer—I didn’t. I thought I would like a molasses porter—I didn’t. I thought I would like loquat wheat beer—four hours peeling and seeding three bags of those little bastards for something I couldn’t even taste!

Experimentation is fine and dandy, but be forewarned that you may not like the result. Refined sugars, like molasses, candy sugar, honey, and maple syrup, can taste wonderful in the right proportion, and that proportion should be strictly as an accent to the beer. Also, keep firmly in mind that you are brewing beer and not a liqueur. Refined sugars often generate fusel alcohols, which can have solventlike flavors. If you want to try a new fermentable or two in a recipe, go ahead, but use a small amount so that it doesn’t dominate the flavor. I feel hypocritical telling you to hold back after first saying to spread your wings and develop your own recipes. But I don’t want you to spend a lot of time making a batch that is undrinkable. Just because it can be done, doesn’t mean it should be done.

Okay, enough said.

In the next chapter, chapter 25, I will lead you through common problems and their causes and define some of the most common off-flavors.

1 Degrees Brix gives the sugar content of a solution by percent weight. It measures the solution density by refractometry, and the Brix scale is roughly equivalent to the Plato scale.

2 Beer Judge Certification Program, 2015 Beer Style Guidelines, http://www.bjcp.org/docs/2015_Guidelines_Beer.pdf