MALBEC

Well, this grape is a native of southwest France. But try telling that to a modern wine drinker. It’s far more likely that today’s enthusiast will say ‘Argentina’. And they’d be right. But 10 years ago when asked to respond to the question – ‘What is Malbec’?, you’d have been met with a blank stare and a distinct lack of interest. Thanks to Argentina, Malbec is now a seriously thrilling star in the red wine firmament.

In its birthplace of Bordeaux and its traditional French home base of Cahors, it was going nowhere – fast. It’s a soft, juicy grape that gives lovely dark, damsony, perfumed, purple wine in a dry warm climate – but in Bordeaux, it was not replanted after the severe frost of 1956. So its ability to soften the Bordeaux blend has been supplanted by the Merlot – which is less susceptible to coulure and rot and gives a more regular crop.

It is a blending component in many southwest reds, but leads the field only in Cahors, where it must comprise at least 70 per cent of the blend. In a warm dry year (not that common) it can give deep dark wines tasting of damson skins and tobacco leaf. It is grown to a limited extent in the Loire, where it is called Cot, but it rarely ripens fully there.

It was first propagated in Argentina in 1852 (the oldest vines still growing are from 1861), but the cuttings came from Bordeaux, not from Cahors, and the Malbec in Argentina now seems to be rather different from that in Cahors. There is far greater clonal diversity in Argentina than in France, with everything from vines with small berries and lots of concentration to the opposite. The ideal spot for it in Mendoza is 1000m (3280ft) altitude and above – which covers a lot of land including the Uco Valley, because the ground rises to the Andes very gradually. Vistalba, Luján de Cajo, Agrelo are leading areas near Mendoza City; La Consulta, Tupungato and Gualtallary are important in Uco. The newest, highest-altitude wines, planted at 1440m (4700 ft) and above, have elegance, finer tannins, better acidity and fabulous, dark-scented fruit.

A vine-pull scheme in Argentina, in the 10 years to 1993, uprooted a lot of Malbec, most of it more than 50 years old.

Chile already has some Malbec, and it’s doing surprisingly well in cool spots. California uses it as a blender and Washington State in its own right. There are some historic plantings in South Australia, and a few plots in New Zealand, where it contributes richness and scent.

THE TASTE OF MALBEC

At its best, carefully grown and skilfully vinified in Argentina, Malbec has a dark purple colour, a thrilling damson and violet aroma (this violet aroma comes from a molecule called beta-ionnona, since you asked), a lush fat dark fruit flavour and a positively soothing ripe tannic structure. It can take new oak aging, but it’s a pity to smother its natural delicious ripeness with wood. In Cahors the flavour is more likely to be raisins, damson skins and tobacco. In both Chile and Australia you occasionally get the violet perfume and you usually get the soft, ripe, lush texture, but Argentina, by taming the tannins and maximizing the perfume and the lush, chubby texture, is leading the way.

Nicolás Catena can take a lot of the credit for propelling Malbec onto the world stage. He returned to his family winery in Argentina from the USA keen to make wine in the style of California’s Napa Valley Cabernets, but, realizing that by far the best supplies of mature vines in Argentina were Malbec, had no trouble in focusing his attention on them. Mendoza is, in fact, ideally suited to Malbec, with excellent vineyard sites rising from about 1000m (3280ft) in height up to 1500m (4900ft). At higher altitudes, the big difference between day and night temperatures makes the grapes take several more weeks to ripen compared to the hotter, lower altitude Mendoza sites, giving wines of great concentration, balance and scent.

Château du Cèdre

Malbec, alias Auxerrois, is the mainstay of Cahors in southwest France: this cuvée, called Le Cèdre, is 100% Auxerrois from 30-year-old vines. Aged in new oak barrels for 20 months, it will last for at least 10 years.

Juan Benegas

The Benegas family are one of the pioneers of Argentine wine. This Malbec marries grapes from 100-year-old Maipu vines with high-altitude Gualtallary fruit in a fine example of modern Argentine Malbec.

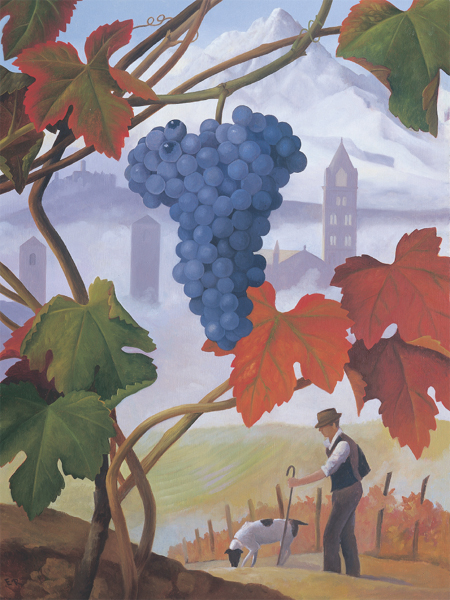

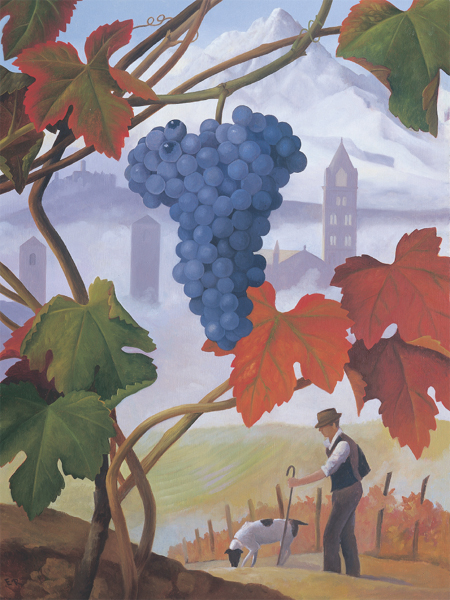

Malbec vineyards in the region of Luján de Cuyo in the province of Mendoza, Argentina with the Andes in the background. The cold nights found at high altitudes here extend the growing season, allowing crucial extra ripeness while still conserving acidity. Even so, it’s difficult to get soft tannins at less than 14% alcohol. And while Malbec rots in wet weather, there is precious little rain this side of the Andes, so rot is not a problem.

Malbec may be blended with Cabernet and Merlot in small amounts in New Zealand and Australia, for extra aroma and fatness of texture.

CONSUMER INFORMATION

Synonyms & local names

Known in the Loire Valley and the South-West of France as Cot or Côt – in Cahors it is called Auxerrois but this is not the same as the white Auxerrois of Alsace. On Bordeaux’s Right Bank, around Libourne, it is called Pressac. In Argentina, where it is called Malbec, the spelling Malbeck is also found.

Best producers

FRANCE Armandière, la Caminade, du Cèdre, Clos la Coutale, Clos de Gamot, Clos d’un Jour, Clos Triguedina, Cosse-Maisonneuve, les Croisille, de Gaudou, Lamartine, Mas des Etoiles, Mas del Périé, du Prince, la Reyne, les Rigalets.

ARGENTINA Achaval-Ferrer, Alamos Ridge, Alta Vista, Altos Las Hormigas, Altos de Medrano, Altos de Temporada, Andeluna, Anubis, Balbi, Juan Benegas, Luigi Bosca, Bressia, Humberto Canale, Catena Zapata, Colomé, Domaine Vistalba, Etchart, Fabre, Finca El Retiro, O Fournier, La Agricola, La Rural, Medalla, Nieto Senetiner, Noemía, Norton, Salentein, Terrazas de Los Andes, Michel Torino, Trapiche, Weinert.

CHILE Altamana, Viña Casablanca, De Martino, Concha y Toro, Lomo Larga, Montes, MontGras, Morandé, Odfjell, Valdivieso, Viu Manent.

AUSTRALIA Jim Barry, Bleasdale, Cullen, Delatite, Ferngrove, Leasingham, Wendouree, Zonte’s Footstep.

NEW ZEALAND Esk Valley, Mills Reef.

SOUTH AFRICA Druk my Niet, Fairview.

RECOMMENDED WINES TO TRY

Fifteen Argentinian wines

Alta Vista Serenade

Altos Las Hormigos Terroir

Andeluna 1300 Malbec

Anubis Mendoza Malbec

Benegas Estate Malbec

Finca El Retiro Malbec Mendel Finca Remota

Catena Zapata Nicasia Vineyard Malbec

Bodegas Fabre Grand Vin

La Agricola Santa Julia Malbec Reserva Nieto

Noemía J Alberto

Norton Reserva Malbec

O Fournier Alfa Crux Malbec

Senetiner Cadus Malbec

Terrazas de Los Andes Las Compuertas

Zuccardi Aluvional

Ten Cahors wines

Ch. du Cèdre Cahors le Cèdre

Clos la Coutale Cahors

Clos de Gamot Cahors Cuvée Vignes Centénaires

Clos d’un Jour Un Jour

Clos Triguedina Cahors Prince Probus

Dom. Cosse-Maisonneuve Le Sid

Ch. les Croisille Cahors Tradition

Ch. de Gaudou Cahors

Ch. Lamartine Cahors Cuvée Particulière

Ch. la Reyne Cahors

Nine other wines containing Malbec

Jim Barry McCrae Wood Cabernet Sauvignon Malbec (Australia)

Viña Casablanca San Fernando Miraflores Estate Malbec (Chile)

Cullen Mangan East Block (Australia)

Esk Valley Hawkes Bay Reserve The Terraces (New Zealand)

Montes Reserve Malbec (Chile)

MontGras Reserva Malbec (Chile)

Morandé Chilean Limited Edition Malbec (Chile)

Valdivieso Reserve Single Vineyard Malbec (Chile)

Wendouree Cabernet/Malbec (Australia)

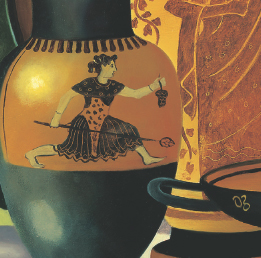

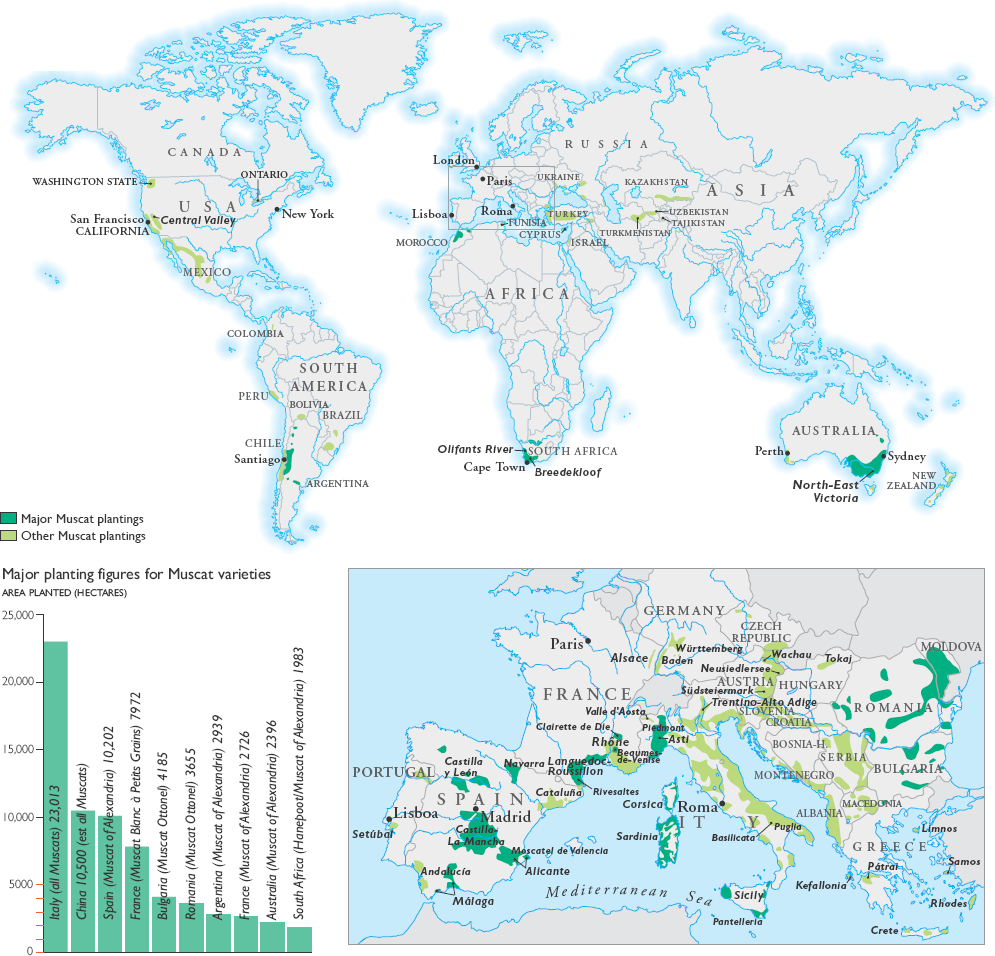

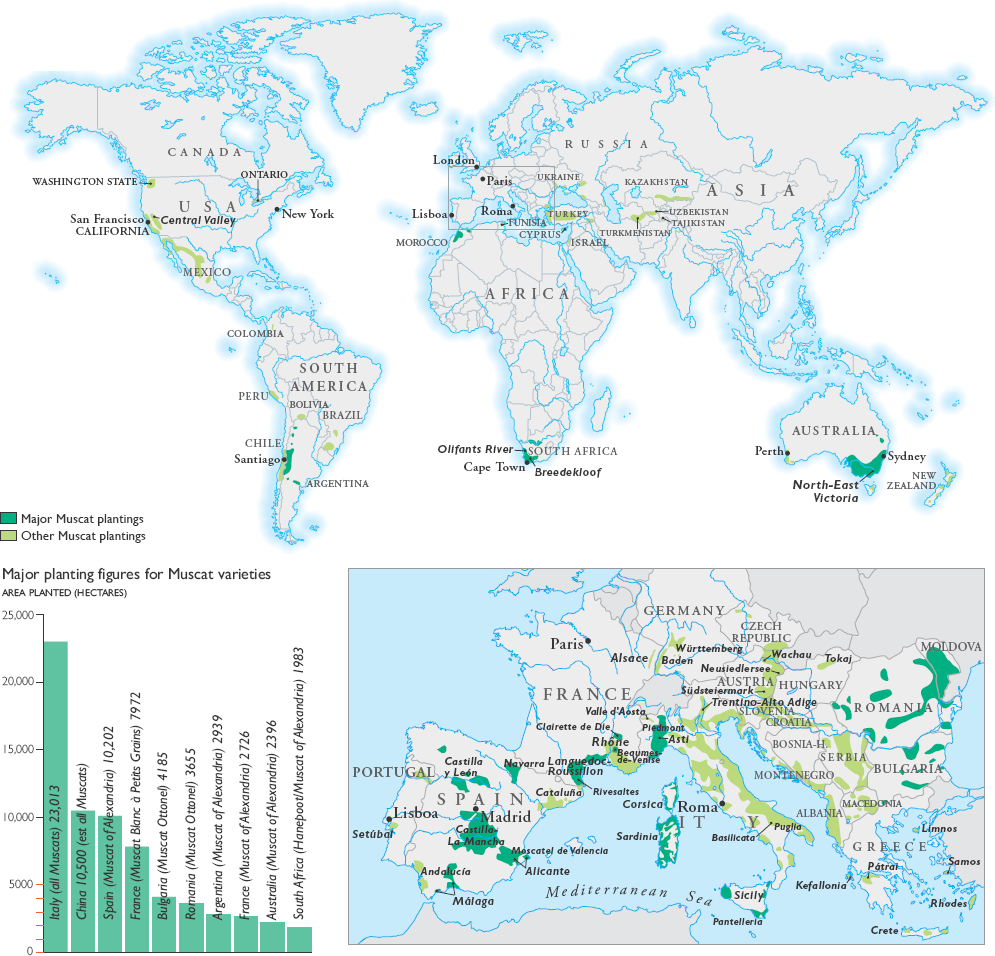

MALVASIA

I think the most gorgeous Malvasia I ever had was pink and frothy, heady with the scent of rose petals and hothouse grapes, and it was from northern Italy. We were all entranced by it, but nobody could really say why it was like that – or even if it had ever been like that before. But that’s the thing about Malvasia – it’s not so much a single grape as a whole family. France uses the name of Malvoisie as a synonym for a whole range of grapes, none of which are Malvasia Bianca. And the various Malvasias are mostly unrelated; so think of the name as being a style rather than a family. Most Malvasia is white, but there are a sufficient number of black versions to produce a range of pink and red wines.

Italy and Iberia are its main homes. As a dry white it is blended with Trebbiano all over central Italy, generally to Trebbiano’s benefit because while Trebbiano is often marked by a singular lack of flavour or texture, Malvasia is generally quite fat and soft and should add a bit of peachy plumpness when young and nutty depth when mature. But not too mature: one or two years old is mature in these sorts of wines. In Lazio’s Frascati, where Malvasia certainly improves the blend, the local version is Malvasia di Candia, though the more aromatic Malvasia Puntinata or Malvasia del Lazio is regarded more highly and makes wines with less of a tendency to flabbiness. Emilia’s Malvasia is also called Malvasia di Candia. There is also a Malvasia di Toscana, which is usually only fit for uprooting. In Friuli there is Malvasia Istriana, which is well structured and flavoursome, producing bright, fresh, scented whites here and in Slovenia and Croatia. A few producers barrel-age it and that can produce wines of surprising intensity.

Passito or fortified sweet white Malvasia – the latter have more aroma – is a speciality of southern Italy, though many wines are almost extinct. The few survivors are really good. Malvasia delle Lipari is the best known; others are Malvasias di Bosa, di Grottaferrata, di Planargia and di Cagliari. Black Malvasia Nera is found in Puglia and Tuscany, and adds a very interesting dark, rich quality to Tuscan Sangiovese reds as well as a chocolaty, sometimes grapy warmth to Puglian blends. There is also some in Piedmont.

Malvasia is found in Rioja and Navarra in Spain and old-fashioned, barrel-aged white Riojas benefit from the Malvasia fatness fleshing out the skinnier Viura. You find it in different forms in Portugal, especially the Douro (Malvasia Fina and the inferior Malvasia Rei, which could be the same as Palomino), Beiras, Estremadura and Madeira, where it produces the rich, smoky, acidic Malmsey (see here). There is a scented version in California, and a little in Greece, and knowing Malvasia, it’ll keep turning up in a good few more places yet, under some pseudonym or other.

THE TASTE OF MALVASIA

With so many subvarieties it is difficult to generalize about Malvasia’s flavour, but where lesser versions can be flabby and low in acidity, tending to oxidize easily, better Malvasias are characterful and aromatic, though not as exotically so as Muscat, with flavours of peaches, apricots and white currants. Istrian Malvazija from Croatia is fresh and scented with wild flowers and peach blossom. Sweet ones are apricotty and rich, red ones dark and chocolatey. In Madeira, where it’s usually called Malmsey, the taste is intense, smoky and treacly but cut with a very insistent acidity.

The word ‘Malvasia’ is rarely found on Madeira labels. The traditional name for Madeira wine made using Malvasia grapes is Malmsey. Indeed, for a time the name Malmsey simply referred to the darkest and richest style of Madeira wine and other grapes – in particular Negramoll – could be used. But despite Malvasia grapes being rare on the island, a serious independent producer like Justino will be able to ensure his wines are made of the grape stated on the label. About time too.

La Stoppa

One of Malvasia’s many variants. Ths one from La Stoppa in the Colli Piacentini in Emilia-Romagna is sweet, fizzy and low in alcohol.

Henriques & Henriques

Henriques & Henriques is one of the only Madeira wine companies to have significant vineyard holdings. The wines are always finely focused.

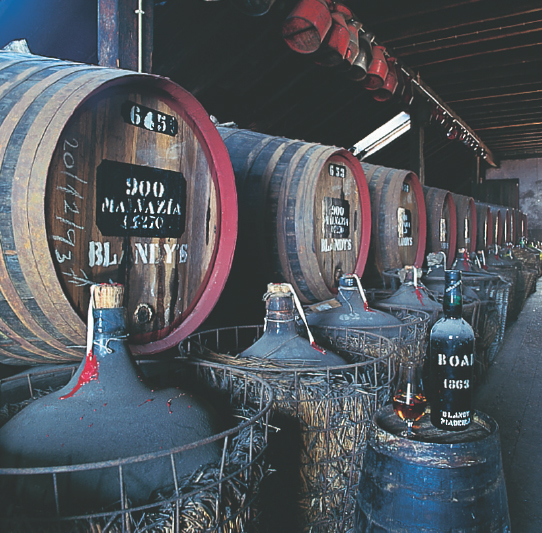

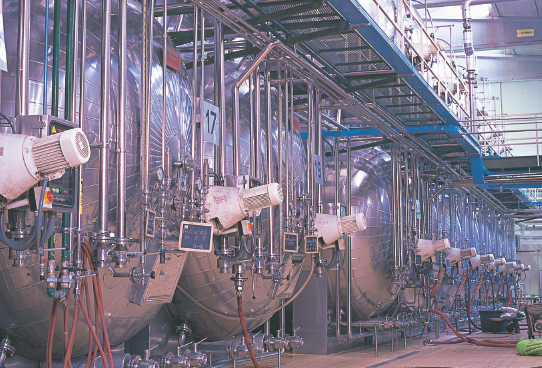

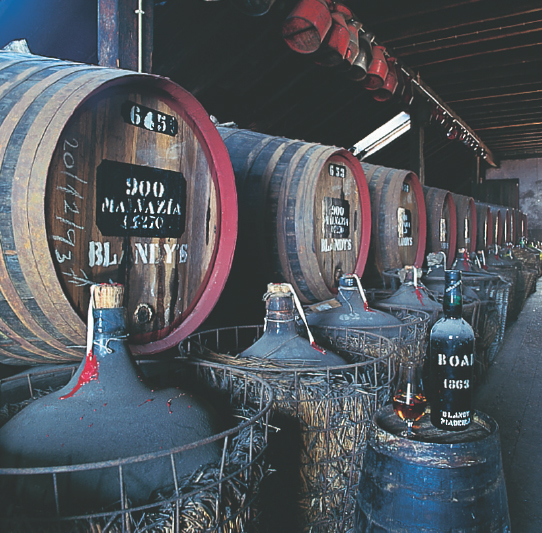

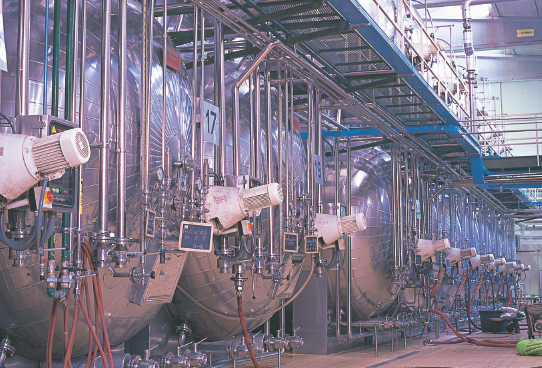

Barrels of Malmsey at the Madeira Wine Company. Because Madeira gains its character from the aging process more than from the grape or from the winemaking, Malmsey Madeiras do not have the peachy, apricot aromas of most Malvasias. Malmsey is the sweetest style of Madeira but even so never loses its acid bite and smoky tang. In Madeira several different strains, or even different grapes, go by the name of Malvasia. Plantings of all Malvasias put together on the island are very small.

Malvasia is one of the hardest of all vines to pin down, simply because it isn’t just a single vine, and not all vines called Malvasia are necessarily related. They’re not even necessarily the same colour.

CONSUMER INFORMATION

Synonyms & local names

Widely planted in Italy and Iberia, there are many different subvarieties of Malvasia Bianca, usually called Malvasia this or that. Not to be confused with the name Malvoisie which is rarely used as a synonym for Malvasia. Malmsey is a style of wine using Malvasia grapes on the island of Madeira.

Best producers

ITALY/Friuli-Venezia Giulia Borgo del Tiglio, Ca’Ronesca, Paolo Caccese, Cormons co-op, Sergio & Mauro Drius, Edi Kante, Lorenzon/I Feudi di Romans, Eddi Luisa, Marega, Alessandro Princic, Dario Raccaro, Schiopetto, Villanova; Emilia-Romagna Forte Rigoni, Luretta, Gaetano Lusenti, La Stoppa, La Tosa, Vigneto delle Terre Rosse; Tuscany (Vin Santo) Avignonesi, Badia a Coltibuono, Fattoria di Basciano, Bibbiano, Bindella, Cacchiano, Capezzana, Fattoria del Cerro, Corzano e Paterno, Fontodi, Isole e Olena, Romeo, San Felice, San Gervasio, San Giusto a Rentennano, Selvapiana, Villa Sant’Anna; Lazio Castel del Paolis; Sicily Colosi, Carlo Hauner.

SPAIN Carballo, El Grifo, Abel Mendoza.

PORTUGAL/Madeira Barbeito, Barros e Souza, H M Borges, Henriques & Henriques, Vinhos Justino Henriques, Madeira Wine Company (Blandy, Cossart Gordon, Leacock, Rutherford & Miles), Pereira d’Oliveira.

CROATIA Coronica, Kabola.

USA/California Bonny Doon, Robert Mondavi, Sterling Vineyards.

RECOMMENDED WINES TO TRY

Ten dry Italian wines

Borgo del Tiglio Collio Malvasia

Castel del Paolis Frascati Superiore Vigna Adriana

Sergio & Mauro Drius Friuli Isonzo Malvasia

Forte Rigoni Colli di Parma Malvasia

Edi Kante Carso Malvasia

Luretta Colli Piacentini Malvasia Boccadirosa

Dario Raccaro Collio Malvasia

Schiopetto Collio Malvasia

La Tosa Colli Piacentini Malvasia Sorriso di Cielo

Vigneto delle Terre Rosse Colli Bolognesi Malvasia

Five sweet Malvasia Italian wines

Colosi Malvasia delle Lipari Passito di Salina

Carlo Hauner Malvasia delle Lipari Passita

Isole e Olena Vin Santo

La Stoppa Colli Piacentini Malvasia Passita Vigna del Volta

San Giusto a Rentennano Vin Santo

Three Spanish Malvasia wines

Carballo La Palma Malvasía Dulce (sweet) (Spain)

El Grifo Lanzarote Malvasía Dulce (sweet) (Spain)

Abel Mendoza Rioja (Blanco) Fermentado en Barica (Spain)

Five Madeira wines

Barbeito Malmsey

Blandy 15-year-old Malmsey

Cossart Gordon 1920 Malmsey

Henriques & Henriques 15-year-old Malmsey

Justino 10-year-old Malvasia

MALVASIA NERA

A black form or forms of Malvasia (see here). In Italy Malvasia Nera is found in the province of Bolzano in Alto Adige, and in Puglia, Sardinia, Basilicata, Calabria, Tuscany and Piedmont. It may be blended with Negroamaro in Puglia, and Sangiovese in Tuscany. It often has a black plum richness and hint of floral scent. In Piedmont it has two DOCs, Malvasia di Castelnuovo Don Bosco and Malvasia di Casorzo. Both can be sweet, sparkling and gently aromatic. Best producers: (Italy) Francesco Candido, Leone de Castris, Roda del Golfo, Cosimo Taurino.

MALVOISIE

This ought to be a French synonym for Malvasia, but it isn’t. Instead, it is a name applied locally to several different varieties in France, among them Pinot Gris (Malvoisie is also the name by which Pinot Gris is known in Switzerland’s Valais), Maccabéo, Bourboulenc, Clairette, Torbato and Vermentino (also known by the name of Malvoisie in Spain and Portugal). Best producers: (France) Vignerons Catalans, Jacques Guindon.

MAMMOLO

Mammole is the Italian word for ‘violets’, of which Mammolo is said to smell. It is planted in such small quantities now that few Tuscan reds owe much to it. It is permitted in Chianti but has largely been bypassed in the rush to improve Sangiovese. There is also a little planted in the Vino Noble di Montepulciano region and it appears in Corsica as Sciacarello. Best producers: (Italy) Antinori, Boscarelli, Contucci, Dei, Poliziano, Castello di Volpaia.

MANDILARIA

Widely planted Greek vine that makes dark, powerful, tannic wine, and is found on various islands, including Crete. Best producers: (Greece) CAIR, Archanes co-op, Paros co-op.

MANTONICO

A Calabrian grape good for both dry and sweet passito wines. Montinico is a synonym for Pagadebit (see here). Best producer: (Italy) Librandi.

MARATHEFTIKO

Cypriot variety traditionally grown to beef up the less interesting Mavro, but now being taken a bit more seriously. The wines have lots of colour and body, and are nicely aromatic. Best producers: Aes Ambelis, Ezousa, Vasa.

MARÉCHAL FOCH

Early ripening and with good resistance to winter cold, this French hybrid is popular in Canada and New York State, where it may be made as a varietal. It makes attractively soft, sometimes jammy, sometimes smoky red wines, and may be aged in oak for more substance. Carbonic maceration is used to make lighter wines. It is named after the First World War French general. Best producers: (Canada) Stoney Ridge, Quails’ Gate; (USA) Wollersheim.

MARIA GOMES

The name given to Fernão Pires (see here) in the Bairrada region of northern Portugal. Best producers: (Portugal) Caves Aliança, Luís Pato, Messias, Quinta de Pedralvites.

MARSANNE

See here.

MARSELAN

A 1961 French crossing of Cabernet Sauvignon and Garnacha favoured by a few growers in southern France and Spain, and also the Americas and China. They have good reason: it makes structured, balanced wines of good colour and aroma.

MARZEMINO

Don Giovanni operatically enjoys Marzemino just before being swallowed up in Hell, and while Marzemino may not be everyone’s idea of the perfect last wish, it is very attractive in less desperate circumstances.

It is found in Trentino and to a lesser extent in Veneto and Lombardy, and has typically northern Italian grassy acidity and cherryish fruit, combined with good colour and ripeness. In Trentino it is usually made as a varietal wine for drinking young; in Lombardy it may also be blended with Sangiovese, Barbera, Groppello and Merlot, though probably not all at once. Sweet passito versions also exist, perhaps blended with other grapes. DNA fingerprinting has shown that it is closely related to Teroldego, and fairly closely to Lagrein. Best producers: (Italy) Battistotti, La Cadalora, Cavit, Concilio Vini, De Tarczal, Isera co-op, Letrari, Mario Pasolini, Eugenio Rosi, Simoncelli, Spagnolli, Vallarom, Vallis Agri.

Armando Simoncelli

Marzemino is one of the most refreshing and mouthwatering of northern Italy’s red grapes – making perfect mountain picnic wine.

MATARO

An Australian name for Mourvèdre (see here), now little used.

MATURANA

An old Riojano vine which practically died out in the early part of the 20th century, this has now been rediscovered and authorized for the Rioja blend. There is also a red version, Maturana Tinta, not related and probably the same as Trousseau and Bastardo. Both colours are regarded in Rioja as of high quality.

MAUZAC

A grape of southwest France with a rustic, green apple skins flavour that is best in sparkling versions, Mauzac is found principally in the Gaillac and Limoux regions. It probably takes its name from either the town of Mauzac in Haute-Garonne, or from that of Meauzac in Tarn-et-Garonne. It is usually blended with other grapes – Len de l’El in Gaillac, Chardonnay and Chenin Blanc in Limoux. In Gaillac it appears in many guises, from dry to sweet, still to sparkling. In Limoux it has been partly supplanted by Chardonnay.

In Limoux it is made into sparkling Blanquette de Limoux and Crémant de Limoux, though usually by the Champagne method rather than the old méthode ancestrale (this basically relied on the fermentation dying down in the autumn – Mauzac ripens late and so the fermentation was not finished before the winter – and then starting again in the spring, by which time the only partially fermented wine would have been bottled). Now the grapes are more likely to be picked earlier for acidity and the Champagne method is used to make a good sparkling wine. Mauzac can produce berries that vary in colour from green through russet and pink to black; Mauzac Noir from the Tarn, however, is a different vine altogether. Best producers: (France) l’Aigle, Gineste, Maison Guinot, Labarthe, Robert Plageoles.

MAVRO

The main red grape of Cyprus is of pretty low quality, and there may be limits to what the most inventive modern winemaking can do with it. Since the name merely means ‘black’ it may, however, cover several different grapes. It is used in the local sweet Commandaria.

MAVRODAPHNE

A Greek vine which makes sturdy, rich red wines, in particular the porty Mavrodaphne of Pátras. It is nearly always made sweet, and treating it this way seems to bring out all its aroma; dry versions, are, however, now being made, with more concentration and extraction. Best producer: (Greece) Achaia-Clauss.

MAVROTRAGANO

Greek vine found on Santorini; the name is probably used for more than one variety. It was on the point of dying out when it was rediscovered, and while still grown in tiny amounts, its wines are impressive. It’s best made into a dry wine, but the tannins need to ripen fully to soften their grip; the wines are dark and spicy, very aromatic, and with a vibrant personality. Best producer: (Greece) Hatzidakis.

Hatzidakis

The Mavrotragano variety covers only 2% of Santorini’s vineyards, but its dark, spicy, powerful wine is impressive, by itself or in blends.

MAVRUD

Mainly found in Bulgaria, late-ripening, small-berried Mavrud makes weighty, solid red wines of character but no particular elegance and it adds a broad-shouldered rustic power when blended with Cabernet or Merlot. It is high in tannins and colour and takes well to oak aging. Best producers: (Bulgaria) Assenovgrad, Maxxima, Santa Sarah.

MAZUELO

The Rioja name for Carignan/Cariñena (see here). It brings acidity, colour and tannin to the blend, but is less prized than Tempranillo. Best producers: (Spain) Amézola de la Mora, Berberana, Martinez Bujanda, CVNE, Muga, La Rioja Alta, Marqués de Riscal.

MELNIK

Bulgarian vine capable of quite high quality wines. It is found mainly around the town of the same name, near the Greek border, and it needs plenty of heat to ripen. Its wines have very good colour and balance and sometimes assertive tannins, and a certain rich warmth, particularly with oak aging. They can be smoky, coffeeish and toffeeish and very appealing, and can improve in bottle. There is a softer, earlier ripening clone that can be easier to drink.

MELON DE BOURGOGNE

This is the one and only grape behind Muscadet, and so closely is it identified with the wine that the grape’s other name is Muscadet. But as one might gather from this name, it originally came from Burgundy and travelled west to reach the western end of the Loire Valley around the city of Nantes. It had been much planted in Burgundy, until its destruction was ordered in the early 18th century whereupon, according to the ampelographer Galet, the growers, in order to save such a useful vine, engineered confusion with Chardonnay and managed to get some Chardonnay torn up in its place. There is still some, albeit only a little, planted on the Côte d’Or.

The Burgundy growers favoured Melon so much because of its resistance to cold – although it buds early, so is apt to be hit by spring frosts – and its generous and regular yields. Its secondary buds are fertile, so even after frost it may be able to produce some sort of a crop. It is, however, subject to some of the growers’ worst nightmares, in the form of downy and powdery mildew and grey rot, and may have to be picked before complete maturity to avoid the worst effects of these.

In the Pays Nantais, where it was introduced after the freezing winter of 1709 which pretty much destroyed whatever grapes were there, it has a poor reputation for high acidity and low flavour, and the best that is usually said of it is that it goes well with the local fruits de mer. But in fact winemaking standards have been rising – skin contact, lees stirring and barrel fermentation for the best wines (not usually new barrels, which can unbalance the flavours) all help to give greater weight and richness. There are even some vins de garde being made, and these can improve in bottle for a decade, becoming honeyed with flavours of quince and ripe greengage. Such wines are, of course, not the norm. Muscadet is still at heart a simple wine for drinking young, but even the négoçiants, who still control 80 per cent of the market, and supermarkets have started to stock better examples. In an era where we are turning against oaky styles and too much aggressive Sauvignon, there’s something to be said for the mellow, reflective charm of decent Muscadet. Growers’ wines are the best bet. Sur lie wines, bottled off their lees, have the greatest depth, and the schist soils of the Sèvreet-Maine region give the best quality.

The Coteaux de la Loire appellation has good terroir but is small, and the sandy soil of the Côtes de Grand Lieu appellation produces light wines for very early drinking.

In California and Australia there has been considerable confusion between Melon and Pinot Blanc, with even cuttings from the University of California at Davis being wrongly identified as Pinot Blanc. Plantings are more or less sorted out now, however. Best producers: (France) Chéreau-Carré, Luc Choblet, l’Ecu, Pierre Luneau, Louis Métaireau, Ragotière.

MENCÍA

This grape of northwestern Spain traditionally gives light, fresh, acidic reds with a raspberry and blackcurrant leaf flavour not unlike a slightly raw Cabernet Franc, and good tannin. It has become increasingly fashionable and is now making many darker examples, often heavily influenced by oak. Which is a pity, since Mencía is delicious drunk young, without oak. It is a rather reductive variety, however, and an enthusiastic adoption of screwcaps has created too many rather sulphidic examples. More careful winemaking will cure this.

It is found in Valdeorra, Ribeiro and, above all, in Bierzo, where it is the main red grape and where it may be blended with Garnacha Tinta. It is delicious young, and doesn’t need the oak it is sometimes smothered in. It is the same vine as Portugal’s Jaen where it can also make delightful juicy reds (see here). Best producers: (Spain) Jesús Nazareno co-op, Moure, Priorato de Pantón, Vire dos Remedios

MENU PINEAU

A grape of the Loire Valley, also known as Arbois, now in decline. The wine is relatively low in acidity and supple.

MARSANNE

I used to think that Marsanne and Roussanne were the Siamese twins of white Rhône grapes; one was never mentioned without the other, but one was also clearly more favoured. Roussanne was always described as far more fragrant and refined, and the clumsier Marsanne was chided for marching in and taking over most of Roussanne’s best sites. Well, it’s true Marsanne has largely supplanted Roussanne in the northern Rhône – it’s a far more reliable cropper which inevitably influences growers’ decisions – but it’s a good grape. And if the only Marsanne you had ever tasted was Tahbilk’s in Australia or the mighty, throat-filling beautiful beast of a mature Hermitage you’d say it was a superb grape. Anyway, it dominates the white blends in Hermitage, Crozes-Hermitage, St-Joseph and St-Péray but is not permitted in Châteauneuf-du-Pape, whereas Roussanne is.

If Marsanne is to have character it must be grown in the right place, and then vinified with care. In too hot a climate the wine produced becomes flabby; in too cool a spot it has an undeveloped simple, bland flavour. And it’s another of those grapes you can’t overcrop – it becomes neutral and characterless. As for new oak, more than just a splash squashes the grape’s personality.

Most Marsanne is made to be drunk young, within just a few years of the harvest. Grapes for this style are often picked before full ripeness to retain acidity, but you risk having a wine without any real taste. That’s why in the Languedoc Marsanne is often blended with the more aromatic Viognier. If you do let the grapes ripen fully on the vine, as they often do in Hermitage and sometimes in Australia, you get high-alcohol wines that can age a good while, and though they often go through a dumb phase after a few years when they taste flat and unforthcoming, after about 10 years they emerge darker in colour and more complex in flavour, and with an oily, weighty, honeyed character accompanied by nuts and quince fruit. Hermitage and the better wines of the Rhône are the best candidates for this sort of aging; there are also a few suitable examples in Australia, where it is planted in small quantities in Victoria for high-quality wine.

There is some Marsanne in Switzerland, where it produces good wine called Ermitage in the Valais region, and there’s some in France’s Savoie, where it is known as Grosse Roussette or Avilleran. California has a bit of Marsanne, but so far the wine tends to be dull and gluey in flavour.

THE TASTE OF MARSANNE

When young it has a minerally edge, often with a citrus, peachy flavour. With age this matures into a rich palate of honeysuckle and jasmine, acacia honey and perhaps a touch of apricot or quince; it is aromatic, quite oily, nutty, and surprisingly heavyweight. Accordingly, it can partner rich food very well when it’s mature. As a young wine it’s equally good with or without food.

The Tahbilk winery in central Victoria is one of the most beautiful in Australia, and has Australian National Trust classification. Tahbilk’s association with Marsanne can be traced as far back as the 1860s although none of these plantings have survived. Vines dating from 1927 are still in use and reputed to be the oldest Marsanne vines in the world. Chateau Tahbilk Marsanne was served to the young Queen Elizabeth II when she visited the winery in 1953. The wine has a distinct honeysuckle aroma and flavour and is very good young as well as improving with up to 12 years’ aging in bottle.

Domaine de Trévallon

This intense wine from Provence is a blend of 45% each Marsanne and Roussanne and 10% Chardonnay; since it fits into no AC rules, it is classified as IGP.

Guigal

A powerful but mildly scented Marsanne wine from Hermitage in the Rhône Valley, impressive when young but also capable of aging for decades.

Picking Marsanne grapes in Chapoutier’s Chante-Alouette vineyard at the top of the Hermitage hill in the northern Rhône. Chapoutier uses Marsanne to make several single-vineyard Hermitage wines as well as a Hermitage Vin de Paille. For the vin de paille the grapes are picked extra ripe and then left to dry indoors for two months before being fermented into an intensely sweet dessert wine.

Marsanne can be a bit of a love-it-or-hate-it grape; but much depends on how well it is handled. Bland, gluey Marsanne is no one’s idea of a good time; but get the balance right and you’ll be rewarded with one of the most unusual whites of all, with weight and complexity and the ability to transform from a bright honeysuckle, fresh youth to a deep, waxy, quincy maturity.

CONSUMER INFORMATION

Synonyms & local names

Known in Savoie as Grosse Roussette and in Switzerland as Ermitage or Ermitage Blanc.

Best producers

FRANCE/Rhône Beaucastel, Belle, Chapoutier, Chave, Coursodon, Cuilleron, Delas, Entrefaux, Florentin, Gaillard, Gripa, Grippat, Guigal, Jaboulet, Lionnet, l’Oratoire St-Martin, Perret, Pradelle, Remizières, Marcel Richaud, Sorrel, Cave de Tain, Trollat, Villard; Provence Clos Ste-Magdelaine, la Ferme Blanche, Pibarnon, Trévallon; Languedoc-Roussillon Alquier, Estanilles, Fabas Augustin, Jau, Lascaux, Pech-Latt.

SWITZERLAND Gilliard, Caves Imesch.

ITALY Bertelli, Casòn Hirschprunn.

SPAIN Celler Mas Gil.

USA/California Cline, Qupé, Tablas Creek; Washington State McCrea Cellars; Virginia Horton.

AUSTRALIA All Saints, Cranswick, D’Arenberg, Marribrook, Mitchelton, Tahbilk, Turkey Flat.

CHILE Errázuriz.

RECOMMENDED WINES TO TRY

Eleven northern Rhône white wines

Chapoutier Ermitage Cuvée de l’Orée

Chave Hermitage Vin de Paille

Pierre Coursodon St-Joseph Blanc le Paradis St-Pierre

Yves Cuilleron St-Joseph Blanc le Lombard

Delas Hermitage Blanc Marquise de la Tourette

Pierre Gaillard St-Joseph Blanc

Grippat Hermitage Blanc

Guigal Hermitage Blanc

Jaboulet Crozes-Hermitage Blanc la Mule Blanche

Sorrel Hermitage Blanc les Rocoules

Cave de Tain Hermitage Au Coeur des Siècles

Ten other French wines containing Marsanne

Domaine Alquier Roussanne/Marsanne

Ch. de Beaucastel Côtes du Rhône Blanc Coudoulet de Beaucastel

Clos Ste-Magdelaine Cassis

Ch. des Estanilles Coteaux du Languedoc Blanc

Ch. Fabas Augustin Minervois (Blanc)

Ch. de Jau Côtes du Roussillon Blanc de Blancs

Ch. de Lascaux Coteaux du Languedoc Pierres d’Argent

Domaine de l’Oratoire St-Martin Côtes du Rhône-Villages Blanc Haut-Coustias

Ch. de Pibarnon Bandol (Blanc)

Domaine de Trévallon Vin de Pays des Bouches-du-Rhône (Blanc)

Eight other Marsanne wines

Bertelli St-Marsan Bianco (Italy)

Casòn Hirschsprunn Contest (Italy)

Cline Cellars Marsanne-Roussanne (California)

Robert Gilliard Ermitage Réserve Choucas (Switzerland)

Caves Imesch Ermitage du Valais (Switzerland)

Celler Mas Gil Clos d’Agon Blanco (Spain)

Tahbilk Marsanne (Australia)

Turkey Flat Butcher’s Block White (Australia)

MERLOT

Merlot: from Grape to Glass

Geography and History here; Viticulture and Vinification here; Merlot around the World here; Enjoying Merlot here

Merlot’s name is said to be derived from merle, French for blackbird, which apparently loves its sweet, early-ripening fruit. Being planted like fury around the world, Merlot has done particularly well in the Napa Valley where the California poppy, as orange as a blackbird’s bill, grows wild.

So what reason would you give for Merlot becoming the world’s most popular red wine style? Would it be because the great Bordeaux reds of St-Emilion and Pomerol, the lush and heady and insanely expensive wines like Pétrus, Le Pin and Pavie are all based on Merlot? Sounds like a good reason. Or would it be because you can make large amounts of red wine out of Merlot which has no hard edges and very little evident flavour so that millions of people who don’t really like red wine at all, can somehow swallow this innocuous brew? Well, I hate to say it, but the second reason is why you’ll find it planted anywhere on the planet where a red grape can ripen.

It all began in 1991, when the prime time USA television show ‘60 Minutes’ covered a phenomenon they titled ‘The French Paradox’, based on the fact that the French eat large amounts of fat and yet have far less heart disease than nations who eat less. So what’s the secret? Supposedly, red wine. Knock back a couple of glasses of red every day and your ticker will glide faultlessly towards a healthy, vigorous old age.

Ever since Prohibition ended in 1933, American wine producers have been trying to turn the USA into a nation of wine drinkers – with limited success. But there’s nothing the Americans like better than being told you can live forever and if the man on the telly tells you you must knock back a couple of glasses of red a day – suddenly millions of Americans who have never drunk wine before are queuing up for their daily dose. American consumption of red wine quadrupled within the year. But these were novice wine drinkers. They didn’t necessarily like the flavour of red wine very much – and what they needed was something that was soft, easy and mild, and yet discernibly, undeniably red. One wine fitted the bill perfectly – California Merlot. It was even easy to pronounce. Suddenly Merlot’s perceived weaknesses were its unique selling point. California couldn’t plant the stuff fast enough, and sold out every vintage, making oceans of, frankly, forgettable but glugglable mellow red. Yet Merlot’s background is a lot more serious than this.

Merlot has traditionally been Bordeaux’s ‘other’ red grape, overshadowed by Cabernet Sauvignon, the dark aristocratic grape that dominates Medoc and Pessac-Léognan. Merlot was planted here too, but simply to soften the Cabernet. Only in St-Émilion and Pomerol was Merlot dominant. When American critics began to swoon over these wines in the 1980s, realizing that their ability to mix the fabled reputation of Bordeaux with a wine you could glug back at only a couple of years old would play brilliantly back home in the States, Merlot finally stepped out from Cabernet’s shadow.

Merlot’s sudden dash to stardom wasn’t lost on the less prestigious Bordeaux regions which always had trouble ripening their Cabernet Sauvignon. As the worldwide rush for red swept through Bordeaux, resulting in a current planting ratio of 88 per cent red to 12 per cent white in a region that was traditionally 50-50 – Merlot was the favoured variety because it didn’t mind damp, clay soils, it didn’t need a massive amount of sun, and it usually gave you a nice, plump bank manager-pleasing crop of something reasonably soft, if a little bit earthy. Much more attractive than thin stalky Cabernet. Bordeaux is now 64 per cent Merlot.

If Bordeaux went mad for Merlot, so did nearly everywhere else. France’s Languedoc and northern Italy have tons of it, mostly making wines that risk being a byword for nothing very much. Spain has a lot, though Merlot is hardly suited to the warm conditions. More encouragingly, it’s really taken off in Eastern Europe – Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova, Croatia all make large amounts of eminently enjoyable Merlot: easy-going red. It’s become a star grape in Chile and New Zealand, Washington State and British Columbia – and California: Napa and Sonoma make some pretty serious stuff. Where else? Oh, pretty much everywhere, really: New York, Brazil, Malta, Bolivia – I’m not joking. Australia has a lot, but has never really got it to work. And the elephant in the room? China. Already the fourth biggest plantings in the world. What will it taste like? We’ll soon know.

GEOGRAPHY AND HISTORY

At first glance the map showing where Merlot is found in the world might look remarkably similar to that of Cabernet Sauvignon. And why not? After all, in Bordeaux they collaborate to excellent effect, and many a Cabernet Sauvignon grower in South Africa, California, Australia and Eastern Europe has found that the traditional Bordeaux blend seems to work pretty well.

And yet there are differences. Merlot is saved from a role of eternal bridesmaid to Cabernet Sauvignon by two factors: its liking for cooler climates than Cabernet Sauvignon, and its ability to produce soft, rich-textured, low-acid, low-tannin red. The latter appeals to many red wine drinkers who don’t care for the rasp of tannin and acidity, but love the appetizing black cherry and chocolate and fruitcake flavours with which Merlot is packed. The former appeals to winemakers in climates that are warmer than typical Pinot Noir conditions (i.e. barely warm enough to ripen any red varieties), but just too cool for Cabernet Sauvignon. In these sites, where Cabernet Sauvignon will turn out too green and raw for fun, Merlot can ripen to soft, silky sweetness. So while the maps of the two varieties might look much the same, they disguise differences of emphasis. Above all, Merlot inhabits the cool fringes and the damper soils where growers look at Cabernet Sauvignon every year and wonder whether to persevere with it. Here Merlot excels.

Merlot likes warmer conditions too, but doesn’t prosper with too much heat because it actually ripens too fast and never develops its lovely plummy personality. This would explain why a lot of budget-priced Californian and Australian Merlot lacks guts. And it needs a firm hand in the vineyard, since it will overcrop like mad if you let it. If you’ve ever stared in disappointment at a glass of pale, flavourless north Italian Merlot, you’re looking at the results of a massively overcropped vineyard. It is far from being as forgiving of unskilful viticulture as Cabernet Sauvignon. Merlot may have wide appeal, but it doesn’t work as an all-purpose grape for lackadaisical producers.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Merlot seems to be native to Bordeaux, but it gets scant attention from commentators on the region until 1784, when a local official called Faurveau named it as one of the best vines in the Libournais region on the Right Bank of the Dordogne; by the mid-19th century it was being planted in the Médoc on the Left Bank of the Gironde for the sake of its ability to blend well with Cabernet Sauvignon and Malbec.

Where did it spring from? It’s part of a local family of grapes which seem to have been interbreeding for centuries. Merlot’s father is Cabernet Franc (which probably originated in the Basque country) and its mother is a terminally obscure little number called Magdeleine Noire des Charentes discovered in an abandoned vineyard near St-Malo in Brittany. I say ‘abandoned’ – St-Malo hasn’t been a wine area for hundreds of years; it’s famous for cider! Honestly, you marvel at the persistence – and the luck – of those scientists who spend their lives trying to unravel the rampant promiscuity of ancient grape varieties. Magdeleine Noire had various names, usually referring to its early ripening, which was around the Feast of Ste Magdelaine on 22 July. So at least we can see where Merlot’s early ripening habits come from. Cabernet Franc and Carmenère are the two vines with which Merlot is most easily confused, and in Chile the confusion was only sorted out in 1997.

Merlot seems to have been noted in Italy at much the same time as it was moving into the Médoc. It is first recorded in the Veneto (as Bordò) in 1855, and in the Swiss canton of Ticino between 1905 and 1910. However, it was brought to Switzerland from Bordeaux, not from Italy.

The limestone côte or hillside on the edge of the town of St-Émilion is one of the best spots for Merlot in the whole of Bordeaux. Merlot is often thought of as a soft, mild wine, but from these steeply sloping vineyards the wines can rival those of the Haut-Médoc on the other side of the Gironde for complexity and longevity, and yet they do retain a delightful suppleness from youth through to maturity.

The glitzy new château building at Château Pavie shows the flamboyant self-confidence of Bordeaux’s modern Right Bank. Pavie’s Merlot-dominated, rip-roaring wines create controversy with every vintage.

The Clos de l’Oratoire barrel chai in St-Émilion. Merlot comprises about 80% of the blend here, the balance being Cabernet Franc, and the result is an impressively juicy, fleshy, robust wine.

VITICULTURE AND VINIFICATION

It is unusual for a grape to become so fashionable without there being any real consensus about how it should be grown and made. If there is a benchmark style, it is presumably that of Pomerol and St-Émilion, but in much of Bordeaux Merlot has long been as much of an insurance policy as a grape appreciated for its own distinct virtues. Its failings as a varietal wine include poor flavour profile: it can be a doughnut wine, with a hole in the middle of the palate.

Clonal variation is important, and there is undoubtedly more work to be done here. It is possible that only 60 or 70 per cent of Merlot’s potential has so far been realized, as anyone who has suffered a lean, mean Merlot vin de pays will testify.

Climate

The climate in the Libournais – the Right Bank of the Dordogne in Bordeaux, where Merlot is concentrated – is actually warmer than that of the Médoc across the Gironde on the Left Bank. The Libournais has less rain and warmer days, but more chance of frost and colder nights. One might think that such conditions would favour Cabernet Sauvignon, with its greater resistance to cold, and greater need of warmth for ripening, and no doubt the French wine authorities reasoned the same way when they insisted on Cabernet Sauvignon being planted on the lower slopes here in the 1970s. But warmer weather can’t compensate for colder soil – at least, not in Bordeaux – and the soils in the Libournais are mostly cold, damp clay. Merlot’s early budding, early ripening habit means that it can cope with cold soils and still ripen, though early budding increases the risk of frost damage. It is also sadly subject to rot because of its thin skin: the vintages of 1963, 1965 and 1968 were even more rot-ridden in St-Émilion and Pomerol than elsewhere in Bordeaux, and if autumn rains threaten, growers fearfully eye their Merlot crop since the grapes could begin to split and rot within a couple of days. Its thin skin also makes it dangerously susceptible to rot in humid climates.

But at least it buds and ripens up to two weeks earlier than Cabernet Sauvignon, which makes it a better bet in most parts of New Zealand; the same is true of Austria, Germany, northern Italy, Switzerland, New York State and Canada.

Though its reputation is for soft, plummy flavours, it can all too easily exhibit a herbaceous green streak. A touch of herbaceous greenness was long thought of as part of the St-Émilion style, until the present vogue for lush, ultra-ripe wines took over; Washington State, New Zealand, Switzerland and the Veneto in northern Italy have all had problems with greenness, which can often be overcome by better canopy management. Even Australian examples are far from being perfectly ripe all the time. Much Californian Merlot avoids any risk of underripeness by being planted in the hot Central Valley – but the downside is that the wines frequently taste baked and lacking in freshness.

Soil

According to Galet (1998), Merlot likes cool soils that retain their humidity in summer; in dry soils, says Galet, the grapes don’t fill out properly. Jean-Claude Berrouet, the previous technical director of Château Pétrus in Pomerol (his son Olivier has now taken over), believes that, on the contrary, water stress is more important than soil temperature for Merlot, and that it performs far better on well-drained soil than at the foot of a slope. Well, they’re both experts. Take your pick. Château Pétrus itself is located on a tiny blister of clay that bulges through the topsoil of ferruginous sand and gravel, and that imparts more than usual structure to the wine; it is clay and iron that give the wines of Pomerol the backbone that most Merlots lack – helped, usually, by a little Cabernet Franc for perfume and acidity. The percentage of clay in some Pomerol vineyards is as high as 60 per cent.

In the sand, clay–limestone (argilo-calcaire) and gravel-over-limestone soils of St-Émilion, too, the traditional blend is with Cabernet Franc. Styles vary with the terroir: sandier soils give looser-knit wines; clay gives more substance, limestone more elegance and perfume.

Clones – and confusion

In much of the New World, clone and climate currently make more difference to style than soil type. Stephan von Neipperg of Château Canon-la-Gaffelière in St-Émilion believes there are only two or three really good clones of Merlot, though many more than that are available. Some give structure; others have larger berries, larger yields and give soft, early-drinking wine. The right choice of rootstock can also help to control the vigour of this naturally vigorous vine and help keep its cropping under control.

I find it difficult to believe this impressive, elegant building is now Le Pin. When I first visited, you literally had to kick the chickens out of the cobwebby garage where the wine was made. But in 2011 this beauty was built. The vineyard is bigger than on my first visit – all of 2.5ha (6 acres) of surprisingly pebbly clay soil where the Merlot ripens particularly fast. And the pine trees? They’re the same.

Some plantings in California, Australia and Austria are strongly suspected of being Cabernet Franc rather than Merlot: in the Napa Valley, Duckhorn’s best block turned out to be Cabernet Franc; and Christian Moueix of Bordeaux confirms that as long ago as the early 1980s he’d thought that some of the Merlot in California was Cabernet Franc. One grower even reckons he can’t tell the difference between the two varieties until their third year. In Chile there’s been confusion with Carmenère since the 19th century.

Yields

Overcropped Merlot produces a thin, stringy, weedy wine, light in colour and vegetal in flavour. Conversely, some vins de garage in St-Émilion may have yields of as low as 26hl/ha; normal Bordeaux yields reach 60hl/ha, and are generally higher than those of Cabernet Sauvignon unless reduced by the vine’s tendency to poor fruit set. In the Midi yields may rise to 80hl/ha; over 100hl/ha quality falls rapidly. In New Zealand yields are between 8–10 tonnes/ha; in California’s Napa Valley, between 4–4.5 tons/acre; in Argentina, where yields are generally high, 12 tonnes/ha is considered low, and 18 tonnes/ha is not unusual.

Michel Rolland, worldwide consultant winemaker, Merlot specialist, and advocate of ultra-ripe, lush wines, believes that yields of the grape throughout the world are too high. ‘It doesn’t like too much sun, and it is difficult to make very expressive, complex Merlot if the climate is too hot. But if you reduce the yield you can improve quality’.

When to pick

This is one of the main focuses of debate between winemakers around the world. A characteristic of Merlot is that once ripe, it must be picked quickly. It will rush from ripeness to overripeness in a matter of days, sometimes even a matter or hours; in this it is less accommodating than Cabernet Sauvignon.

There are two schools of thought about when to pick. Michel Rolland favours late picking, and welcomes fruit with an element of overripeness. ‘The picking date is vital. Get that wrong and everything else will be wrong; you will lose 80 per cent of the potential. Many properties in Bordeaux pick between a few days and a week too early. But the crop level is the main factor. If the crop is too big, you can wait until Christmas, and it won’t ripen. The ideal crop is 40–50hl/ha. At that level you can successfully delay picking for eight to 10 days more. And if you remove some of the leaves, there is less risk of rot, so you can wait.’

Chris Camarda makes some of Washington State’s most successful Bordeaux blends under his Andrew Will label. The relentless sunshine in the Washington vineyards would make you think it would be too hot for the cool-loving Merlot – but check out that heavy coat Chris is wearing as he considers his Merlot harvest. It may be sunny, but it isn’t hot at vintage time in the near-desert conditions of eastern Washington.

The other side of the Merlot coin, that which advocates traditional elegance, finesse and potential for longevity above richness and lushness, is represented by Christian Moueix of JP Moueix who points out that overripeness means loss of acidity. ‘We want light, elegant wines for drinking, not body-building wines for winning tastings.’

WINEMAKING: THE GREAT DEBATE

At the higher quality levels, Merlot is a wine with an identity crisis. It needs elegance, complexity, fine tannins and silky texture – but can winemakers best achieve that ideal by treating the grape like Pinot Noir, or by treating it like Cabernet Sauvignon?

The issues revolve around extraction and oak. Should Merlot be heavily extracted and tannic, and aged in a high proportion of new oak? Or should it be lighter, more delicate? Fashion is changing. Until a few years ago, it dictated heavy extraction and tannin, soupy textures and high alcohol, but now lighter reds are finding favour again. Napa still focuses on weight, and St-Emilion is divided, but the rest of the world is returning to elegance, recognizing that not all Merlot is naturally as structured as Pétrus, or as concentrated as Valandraud; and that if it’s not, it cannot be made so by long aging in new oak.

Consultant winemaker Michel Rolland recommends extracting the phenols (colour and flavour compounds) at the beginning of the fermentation process with a shorter, faster maceration with frequent pumping over. Researchers in Bordeaux are trying to build up a better picture of Merlot by analyzing the structure of its tannins and phenolic compounds. By compiling a dossier of the aromas and flavours most frequently found in the wine, they hope to arrive at a clearer understanding of its potential.

I have to say, some of the most beautiful St-Émilions I’ve enjoyed have been made in the lighter style, because Merlot gains a gorgeous soft butter and toffee smoothness with age if you don’t try to force more weight and colour out of the grape than it naturally possesses. However, if you’re after something altogether more powerful and lush, Michel Rolland clearly has the answer in Bordeaux and around the world.

MERLOT AROUND THE WORLD

How many great varietal Merlot wines are there in the world? A lot depends on what you mean by ‘great’. If you mean dark, muscle-bound bruisers built for the long haul, or slow-developing intellectual beauties that take a generation to reveal their treasures, then the answer is – there aren’t many. But if greatness can be measured in a hedonistic way, if succulence, sensuous fruit and a perfume that fills your head with sweet ripeness could be called great, there’d be quite a few. High alcohol, dark colour, low tannins and acidity and a cauldron-full of nice, ripe fruit is what Merlot is best at. Pleasure, in other words. But are they great? Look. I’m too thirsty to argue. Hand me the bottle. I’ll drink, you fret.

Bordeaux

Merlot has quietly been staging a takeover in Bordeaux, spurred on by the worldwide demand for softer, earlier-drinking wine. It now constitutes some 56 per cent of plantings overall – but that figure disguises its minority role in the better parts of the Médoc and Graves, where it makes up an average of 25 per cent of the blend, and its dominance in St-Émilion and Pomerol. In the outlying areas of Bordeaux – the areas collectively known as the Côtes – it is very often the majority grape.

In St-Émilion it accounts for more than 60 per cent of plantings; in Pomerol about 80 per cent. In both these appellations it is commonly blended with some Cabernet Franc; there is a little Cabernet Sauvignon in St-Émilion, and some, though less, in Pomerol.

The standard Bordeaux blend of Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet Franc, with or without the addition of Malbec or Petit Verdot, has a lot to recommend it. Merlot adds softness and fleshiness, Cabernet Franc adds perfume and Cabernet Sauvignon adds the all-important structure. Merlot on its own is generally less long-lived, although St-Émilion and Pomerol can be tight and closed when young, and like Médoc and Graves reds, can need some years to open. It is the crasse de fer – the iron-rich clay subsoil – that imparts structure to Pomerol’s Merlot; the very structure that can be so wanting elsewhere. Château Pétrus is made from 95 to 100 per cent Merlot in most years; Le Pin and Gazin are 90 per cent Merlot. But at some Pomerol châteaux, for example Lafleur with its particularly gravelly, mineral-rich soil, the amount of Merlot in the vineyards goes down to 50 per cent with old Cabernet Franc taking up the rest.

The heart and the muddy boots of Michel Rolland are most at home in the clay-clogged vineyards of Bordeaux’s Right Bank where he grew up, but much of his year is spent travelling since he is the most successful and famous wine consultant in the world, with rich, mouthfilling Merlot reds very much a calling card.

In St-Émilion the vin de garage phenomenon – wines made on so small a scale that one could envisage making them in one’s garage – was fuelled by Merlot. Yields of 30hl/ha or less are the rule here, from tiny vineyards (Gracia is 3ha/7.4 acres; Clos Nardian is 1.52ha/3.75 acres; La Mondotte is a positive giant at 4.3ha/10.6 acres). Picking may be by individual berry; viticulture may be organic or biodynamic; oak will almost certainly be 100 per cent new, and may even be 150 per cent new, this remarkable figure being achieved by putting the wine into 100 per cent new oak to begin with, and then racking it into more new oak.

These wines have enormous and seductive richness and a few have joined the mainstream; otherwise the fashion has peaked amid question marks over longevity.

Vins de garage could be made anywhere: they’re the equivalent of a bigger estate creaming off the very best vat, or couple of vats; something that bigger estates are usually loath to do because of its detrimental effect on the rest of the blend. However, the principle has been accepted across the globe by winemakers and growers (not necessarily of Merlot) who want to make a fast impact.

Other French Merlots

Merlot has now overtaken Carignan and Grenache as France’s most planted grape variety. It is a recommended variety for appellation contrôlée wines and vins de pays in Provence, the Languedoc, the Southwest, the Ardèche, the Charente, the Corrèze, the Drôme, Isère, the Loire, Savoie and Vienne, though in the South it is a fairly recent arrival, having only been recommended there since 1966. In the Southwest it is a traditional part of many appellation contrôlée blends. In the Languedoc most Merlot goes into vins de pays, both varietals and blends. Most are soft, fruity wines for early drinking.

Château Palmer

Palmer often contains 40% Merlot, high for a top Haut-Médoc wine. The result is classic Margaux perfume married with seductive softness of texture.

Château Pétrus

If anyone doubts that Merlot can age, show them a mature Pétrus: nowadays it’s 100% Merlot. But it does come from a unique, Merlot-friendly terroir.

Le Macchiole

You’d expect Bolgheri on the Tuscan coast to be too warm for the cool-loving Merlot, but some of Italy’s most successful Merlots are from here.

Merlot vineyard at Tenuta dell’ Ornellaia owned by Marchese Lodovico Antinori at Bolgheri. so near the sea that locals in this part of Tuscany used to reckon that the wines from round here tasted of salt. That was before the super-Tuscan brigade got cracking. This Merlot, called Masseto, is one of the world’s best.

Italy

Merlot fever has hit Italy in a big way: in the mid-1990s it was Italy’s fifth most planted grape, but current plantings have pushed it to fourth, even ahead of Barbera. In the northeast it has traditionally been regarded as a high-volume producer, and clones were chosen primarily for their yield. It wasn’t given the best sites, and the wine was easy-drinking stuff, not intended to be taken seriously. This is true of the Veneto, Trentino and Alto Adige, though Merlot from Alto Adige is benefiting from better clones and more attention to site. The best wines come from Friuli, Tuscany and Umbria, and they are very good indeed. Some is varietal; a lot is blended with Sangiovese, and is valued for adding richness without dominating the blend in the way that Cabernet Sauvignon does. In Tuscany it is increasingly being planted in the warmer Maremma, and alcohol levels can easily reach 14 per cent, though acidity doesn’t seem to suffer; perhaps it is added. In more northerly parts of Tuscany, Merlot’s low acidity is often seen as a useful softener for the more acidic local grapes.

Rest of Europe

Almost all of Europe grows Merlot. In Switzerland’s southern canton of Ticino, Merlot accounts for 85 per cent of production. It needs warm sites here, and vineyards no higher than 450m (1480ft), to produce wines of any substance; the best are well structured, and have some oak aging. Some Merlot here is made ‘white’ – pale pink, in other words.

Elsewhere it is concentrated in the cooler areas: it has made little impact in Iberia, though it has experimental status in Rioja. (There are moves to get practically everything on to the list of approved grapes in Rioja.) There is some in Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia & Montenegro, some in Austria and Germany, and more in Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary and Moldova; much is blended with Cabernet Sauvignon.

California

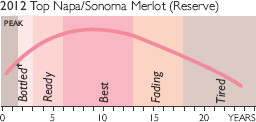

Experience is telling here. More and more Merlot is being planted, and once the current plantings come on stream, California will be the world’s fourth largest producer of Merlot, after Bordeaux, Italy and the Languedoc. Post-phylloxera plantings are on more suitable rootstocks than before, and much has been learnt about trellising: Merlot grows particularly long shoots, which need to be tied, often to an extra moveable wire. Site selection is also better. Cooler spots that wouldn’t suit Cabernet Sauvignon are being chosen – Carneros, for example, gives good bright flavours to Merlot, though Cabernet doesn’t ripen well there. Parts of Napa, like Oakville and Stags Leap, give richer wines, and hillside sites like Howell Mountain, where Cabernet is structured and long-lived, impart similar qualities to Merlot.

These, and other parts of California like Mendocino, Alexander Valley, Dry Creek Valley, Sonoma Valley and the warmer areas of Monterey, are where the serious Merlots are coming from. Some are huge wines, so massive that they make Pomerols look feeble. Extreme ripeness – the US market recoils at any hint of herbaceousness – is obtained by leaving the grapes on the vines for as long as possible, and alcohol levels are high. But those who want light Merlot (or perhaps Merlot lite) are also being catered for. A lot is being planted in the hot Central Valley for high-volume, low-intensity wine. And by low, I mean low.

Castello di Ama

Castello di Ama already makes one of the most sensuous and approachable of Chianti Classico wines. This Merlot is in the same delicious vein.

Leonetti Cellar

This Merlot brought attention to Walla Walla, an area in Washington State that is now making some of the Pacific Northwest’s most impressive reds.

Merryvale Vineyards

Merryvale is based near St Helena in central Napa, but the grapes for this Merlot come from the cooler vineyards down toward Carneros and San Pablo Bay.

North America

Cabernet Sauvignon is the leading red grape in Washington State with almost 10,293 acres/4165ha planted, with Merlot following behind in second place with 8235 acres/3332ha of vines in 2011. Merlot gives richer flavours here than Cabernet Sauvignon, and while the wines are riper and plummier than they were, they still tend to be drier than Californian examples, with more freshness and often more personality. Site selection, control of irrigation and later picking have all helped. Cold eastern Washington winters remain a problem for the variety. Classic Bordeaux blends are also successful, and at the moment seem the best way of using Merlot here. Oregon seems generally too cool, and fruit set is poor. New York State is more promising: Long Island’s long growing season means that Merlot ripens reliably here, and Merlot is now the most planted red variety in Virginia. Merlot is important in Canada, and is British Columbia’s most planted variety, as Canadians strive to make grand reds.

South America

The term ‘Chilean Merlot’ used to be somewhere between a euphemism and a nickname, but Chile’s Merlot vineyards are now well sorted out. The reason was that much Chilean Merlot was a field blend of Merlot and Carmenère: the original cuttings were taken to Chile from Bordeaux before phylloxera and propagated as Merlot ever since. Nobody had thought to question the vines’ identity until it was realized in the early 1990s that a lot of Chilean Sauvignon Blanc was in fact the less aromatic Sauvignonasse, or Sauvignon Vert. French ampelographers were then invited to look over the vineyards, and came up with the unsettling discovery that a great deal of the ‘Merlot’ was not Merlot at all.

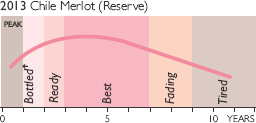

The two grapes are now separated in new plantings, but it will be years – decades, even – before the existing mixed plantings are superseded. New varietal Merlots on the market are now genuine, but some of the best still boast the extra flavours of Carmenère. According to the latest official figures (2011), Chile has 11,432ha (28,250 acres) of Merlot and 10,040ha (24,810 acres) of Carmenère, respectively the third and fifth most planted varieties in the country. The problem is not that Carmenère is an inferior grape – indeed, it can have greater quality in Chile than Merlot – but that they ripen at different times. Merlot ripens some three weeks before Carmenère, so unless you have each vine marked in the vineyard and can pick the two varieties separately, you will either end up with ripe Merlot and underripe Carmenère, or overripe Merlot and ripe Carmenère, but whereas over-ripe Merlot spoils a blend by being too jammy, under-ripe Carmenère adds a fascinating and refreshing green peppery, leafy, savoury character if mixed with ripe Merlot, which is a uniquely Chilean combination.

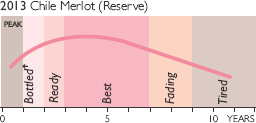

Site selection is fashionable now in Chile, and Merlot often seems to be less interesting than Pinot Noir and Syrah to those producers planting in the cooler regions of the far north and south (the north counts as cool when it’s coastal and is cooled by sea breezes; it’s actually cactus country). The Central Valley regions are still Merlot’s stronghold and plantings outside the regions of Maipo, Cachapoal, Colchagua, Maule and Curicó are small or non-existent.

Merlot in Chile: a tale of two vines

‘We were the origin of the discovery that a lot of Chilean Merlot is actually Carmenère,’ say Paul Pontallier and Bruno Prats. These leading Bordeaux winemakers (Pontallier makes the wine at Château Margaux, and Prats used to own Cos d’Estournel) joined forces in the late 1980s to make wine near Santiago in the Maipo Valley – the estate, now called Viña Aquitania, is located at 700–800m (2300–2625ft).

They bought two batches of Merlot vines to plant, and soon realized that if one was Merlot, the other had to be something else. An ampelographer friend from France eventually identified the mystery vine as Carmenère. ‘The latter blends well into Chilean reds,’ says Pontallier, because ‘Merlot doesn’t behave in Chile as it does in Bordeaux: it is harsher than in Bordeaux, whereas Cabernet Sauvignon is softer here. So the classic Bordeaux blend may not be the best thing for Chile.’

The differences between the varieties seem to be glaringly obvious if you look at this post-harvest vineyard scene at Casa Lapostolle’s Clos Apalta in the Colchagua Valley. Look at the different colours of the vine leaves – the green ones are the late-ripening Cabernet Sauvignon, the red ones are Carmenere whose name refers to the redness of the leaves and is derived from an old French word for ‘red’ – carmine. The yellow leaves are Merlot, so how did they ever mix up Carmenère and Merlot?

Hawkes Bay is one of New Zealand’s best regions for Merlot, the country’s most successful ‘Bordeaux’ red variety. It ripens earlier and more completely than the other varieties, and provides crucial richness and softness to blends in conditions that are still a little on the cool side for Cabernet Sauvignon.

Merlot in Argentina is less planted than Cabernet Sauvignon or Malbec, and can be trickier to grow. High yields may well be part of the problem. The best, most concentrated wines come from the Mendoza hills at around 1100m (3610ft) and above. Merlot is important in Uruguay for softening the toughness of Tannat, and there’s a fair bit in Brazil.

Australia

Recent years have seen a substantial increase in plantings and Merlot is now the third most popular red variety, but is still some way behind Shiraz and Cabernet. At the moment a lot is still blended with Cabernet Sauvignon, but the number of varietal wines is increasing as growers understand it better. Paul Lapsley, of Coldstream Hills in the Yarra Valley, believes that the clones in Australia are particularly poor. But new clones, released over the last few years, should help to improve flavours and the bane of the Merlot grower’s life, poor fruit set.

New Zealand

New Zealand growers like Merlot because, unlike Cabernet Sauvignon, it’s a reliable ripener in cool climates. Merlot is now the country’s fifth most planted grape, and second most popular red after Pinot Noir. It is at its best in the North Island, with the South Island being a little chilly even for Merlot. Over half the plantings are in Hawkes Bay, particularly in Gimblett Gravels and the Ngtarawa Triangle, where it produces dense, dark wines that dominate the local Bordeaux blends. Most of the rest is in Auckland and Marlborough: it may have a good future in cool-climate Marlborough, where Cabernet Sauvignon is a poor ripener. Blends are usually with the other Bordeaux varieties; some producers prefer a Cabernet Franc and Malbec blend.

South Africa

By 2013 Merlot accounted for just under 7 per cent of total plantings; Cabernet Sauvignon, by contrast, was top with 11 per cent. Since there was no Merlot planted in the country at all until the 1980s, that is a rapid increase – and expect plantings to continue to rise.

Two basic styles of Merlot are emerging in South Africa: the soft, juicy, easy-drinking version, and something altogether more impressive, powerful and potentially long-lived. One-third of the vines are planted in Stellenbosch, with a fair number also in Paarl, followed by Worcester and Malmesbury and cool-climate Constantia. New virus-free clones have helped its advance in recent years.

Asia

China has taken to Merlot in a big way as part of the classic red Bordeaux blend and may well have the largest Merlot plantings in the world after France by the time you read this – things are moving at lightning speed in Chinese

Bedell Cellars

Bedell make some of New York’s best reds on the sandy loam soils of Long Island’s North Fork. The elegant label shows their love of modern art. .

Tapanappa

Australia’s largest limestone area is South Australia’s Limestone Coast, with Wrattonbully at its heart. Tapanappa’s Whalebone Vineyard takes full advantage to produce soft but beautifully balanced red wines.

Craggy Range

Craggy Range make use of Merlot’s suitability for the warm Gimblett Gravels in New Zealand’s North Island to produce the rich, sensuous but powerful Sophia Merlot.

Vergelegen

Vergelegen’s Helderberg vineyards are cooled by strong southerly winds whipping in from False Bay, creating one of South Africa’s freshest, juiciest Merlots.

ENJOYING MERLOT

A great deal of the time, the question of how well Merlot ages is irrelevant. Most is made to be drunk young, even immediately: modern Merlot is the epitome of the red wine that gets all the bottle age it needs on the way back from the wine shop.

That is true both of simple, juicy Merlots and of big, concentrated ones. Merlot’s low tannins and low acidity make it a less than obvious wine for the cellar; the majority of Merlots not only don’t need bottle age, but often positively don’t want it. Age these wines and your patience will be rewarded by fading fruit and disintegrating structure.

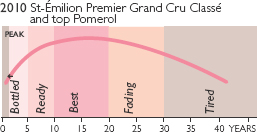

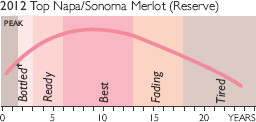

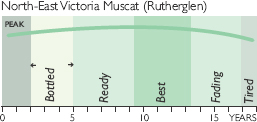

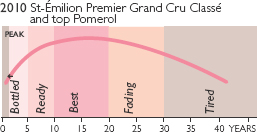

Yet Merlot can age perfectly well as part of the Bordeaux blend – and not just because it has Cabernet Sauvignon to prop it up. St-Émilions and Pomerols, usually with little or no Cabernet Sauvignon in the blend, will easily last a decade, and the very best wines will see in their 30th birthday. Such wines need time to come round in the first place: from two or three years to longer, depending on the property and the vintage. Top Pomerols and St-Émilions with decades ahead of them are, however, exceptions even in Bordeaux: normally if a Bordeaux proprietor simply wants to make earlier-maturing wine, he plants more Merlot and doesn’t prune too hard.

The structure of Merlot from Bordeaux is also found in the best examples from California, Italy and elsewhere. There is no question about these balanced wines having the grip and backbone to last at least 10 years and perhaps more; the question is how many get the chance.

The taste of Merlot

This is where one has to raise the biggest question mark of all. Merlot tastes of all sorts of things: it can be anything you want, from light and juicy through Pinot Noir-silky to Cabernet-oaky and extracted. What should it taste like? That’s the very question that winemakers across the world are asking themselves. The lack of benchmarks means that there is no easy answer.

At its best it is succulent and silky, with velvety tannins: ‘smooth’ is the word that has cropped up most often in US market research. Fruit flavours can be of strawberry, raspberry, black cherry, blackcurrants, plums, damsons, figs or prunes. Fruitcake flavours are often found in Bordeaux. There can be spice, too: cinnamon and cloves and a touch of sandalwood, and truffles, tobacco, liquorice and toasted nuts. Warm climates can give stewed fruit flavours; cool ones, or overcropped vines, can give minty, lean, herbaceous notes. It can be gamy, chocolatey or coffeeish; yet for every Merlot that exhibits such appetizing complexity there are 20 examples that aim for no more than sweet juicy fruit and that seductively velvety texture.

To many a Californian winemaker, Merlot is about texture more than flavour. Texture is what they believe consumers notice most; and if Merlot mania is a fair guide, perhaps they’re right. But what they are often really saying is ‘lack of texture’: blandness, total smoothness, with a flavour as mild as can be, sometimes helped along with a little sugar. This is lowest common denominator ‘wine without tears’, and the phenomenon has been massively boosted by the claims of red wine being good for your heart. These claims meant that millions of people who didn’t like red wine, and never drank it, would drink it for their health – so long as it didn’t taste like red wine. Many of the budget-priced commercial American Merlots are merely trying to satisfy that market. Good luck to them. May it keep their customers healthy. I’ll stay healthy by drinking equal amounts of something slightly more interesting.

Merlot was the wine that made Chile famous, but Merlot wine wasn’t necessarily made from Merlot grapes in those days – the Merlot vineyards were co-planted with Carmenère, a rare Bordeaux grape at one time thought to be extinct. Indeed, Carmenère used to be called Merlot, while Merlot was called Merlot-Merlot! Nowadays, Carmenère sails under its own colours, as does Merlot, and 20 Barrels is a high quality special selection of true Merlot. Angelus has made one of the top St-Émilions for 20 years, and was promoted to the highest classification of 1er Grand Cru Classé (A) in 2012. Merlot is St-Émilion’s leading grape variety, and Angelus is usually 90% Merlot.

MATCHING MERLOT AND FOOD

Merlot makes soft, rounded, fruity wines that are easy to enjoy without food, but it is also a good choice with many kinds of food. Herby terrines and pâtés, pheasant, pigeon, duck, goose and spicier game dishes all blend well with Merlot. It can also partner subtly spiced curries and tandoori dishes. Meaty casseroles made with wine are excellent with top Pomerol châteaux; and the soft fruitiness of the wines is perfect for savoury foods with a hint of sweetness such as ham, savoury pancakes and gratins.

CONSUMER INFORMATION

Synonyms & local names

Also known as Merlot Noir, and in Hungary as Médoc Noir. Not to be confused with the unrelated Merlot Blanc, also found in Bordeaux but now almost extinct.

Best producers

FRANCE/Bordeaux/St-Émilion

Angélus, Ausone, Beau-Séjour Becot, Canon, Canon-la-Gaffelière, Clos Fourtet, Grand-Mayne, Magdelaine, Monbousquet, la Mondotte, Pavie. Pavie-Macquin, le Tertre-Roteboeuf, Troplong-Mondot, Valandraud; Bordeaux/Pomerol le Bon Pasteur, Certande-May, Clinet, la Conseillante, l’Église-Clinet, l’Evangile, la Fleur-Pétrus, Gazin, Hosanna, Latour-à-Pomerol, Petit-Village, Pétrus, le Pin, Trotanoy.

ITALY/Veneto Maculan; Friuli Borgo del Tiglio, Livio Felluga, Graf de la Tour, Russiz Superiore; Tuscany Castello di Ama, Avignonesi, Castelgiocondo, Ghizzano, Le Macchiole, Ornellaia, Petrolo, San Giusto a Rentennano, Tua Rita; Lazio Falesco; Sicily Planeta.

SPAIN Can Rafols dels Caus, Pago del Ama, Torres (Atrium).

SWITZERLAND Brivio, Huber, Werner Stucky, Tamborini, Vis, Zanini, Christian Zündel.

ISRAEL Barkan, Dalton, Margalit.

USA/California Arrowood, Beringer, Buccella, Chateau St Jean, Frog’s Leap, Matanzas Creek, Merryvale, Newton, Pahlmeyer, Rubissow, Shafer, Truchard; Washington State Andrew Will, Canoe Ridge, L’Ecole No 41, Leonetti, Long Shadows, Northstar, Quilceda Creek, Woodward Canyon; New York Bedell, Lenz, Macari, Paumanok, Shinn Estate, Wölffer.

CHILE Carmen, Casa Lapostolle, Viña Casablanca, Concha y Toro, Cono Sur, Errázuriz, Gillmore, Viña Leyda.

AUSTRALIA Brand’s, Coldstream Hills, Elderton, Fermoy Estate, Irvine, Parker Coonawarra Estate, Tapanappa, Tatachilla, Yalumba.

NEW ZEALAND Alluviale, Craggy Range, Esk Valley, Fromm, C J Pask, Sacred Hill, Trinity Hill, Villa Maria.

SOUTH AFRICA Bein, Eagles’ Nest, Laibach, Shannon, Steenberg, Thelema, Vergelegen.

RECOMMENDED WINES TO TRY

Ten classic Bordeaux red wines (as well as the Best producers, left)

Ch. Canon-de-Brem Canon-Fronsac

Ch. Canon-la-Gaffelière St-Émilion

Clos Fourtet St-Émilion

Ch. la Conseillante Pomerol

Ch. Gazin Pomerol

Ch. Grand-Mayne St-Émilion

Ch. Fontenil Fronsac

Ch. Latour-à-Pomerol Pomerol

Ch. Pavie-Macquin St-Émilion

Ch. Roc de Cambes Côtes de Bourg

Seven good-value Bordeaux reds

Ch. d’Aiguilhe Côtes de Castillon

Ch. Annereaux Lalande-de-Pomerol

Ch. Carsin Premières Côtes de Bordeaux Cuvée Noir

Ch. Pitray Castillon-Côtes de Bordeaux

Ch. la Prade Côtes de Francs

Ch. Segonzac Premières Côtes de Blaye

Ch. Siaurac Lalande-de-Pomerol

Six top Italian Merlots