ENJOYING SANGIOVESE

Sangiovese can age, and age well, but most of its wines are intended to be drunk within a year or two of the harvest; they may develop an almost tomato-like leanness if left hanging around for too long. In fact, with so many different styles and qualities being made in Italy and with many of these being very recent innovations, it’s pretty tricky to generalize about aging. In most regions there are a few producers trying to do something smart with Sangiovese that could merit aging, but even they themselves couldn’t guarantee you a successful conclusion, especially when the use of new oak has been overdone.

The longest-lived wines are Brunello di Montalcino and the finest Sangiovese-based super-Tuscans. (Originally these all held the lowly status of vino da tavola, but now they have to move up the ranks of the Italian wine classification system, to DOC or IGT – Indicazione Geografica Tipica). In a good vintage these wines may well keep for 20 years, but most can start to be drunk after about five.

Vino Nobile di Montepulciano and the lighter Rosso di Montalcino can also be broached after five years, or sometimes less; all these should be drunk within eight to ten years. Carmignano has roughly the same lifespan.

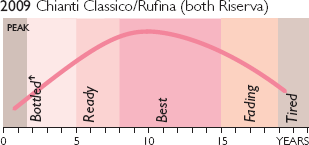

Chianti is even more variable. Most basic Chianti should be drunk within three or four years of the vintage; Riserva may need a year or two more before it is ready. The very top wines, but only these, may last up to 15 years or more.

Other Italian Sangioveses should be drunk young unless they come from a producer who is specifically making a wine for aging. The same goes for New World Sangioveses: nearly all should be drunk within three or four years, and examples from Argentina are good within a year of the vintage.

The taste of Sangiovese

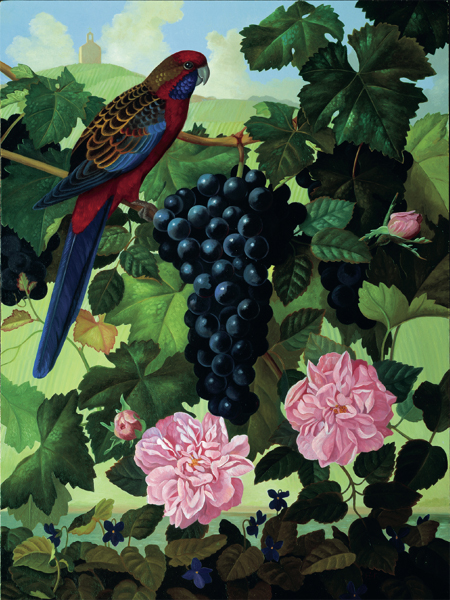

The traditional flavours of Tuscan Sangiovese are of bitter cherries and violets, with a certain tomatoey savouriness to the fruit, a definite rasp of herbs and a tea-like finish. Acidity is high and so is tannin: upfront fruit flavours are not the be-all and end-all of traditional Tuscan reds.

That has partly, though by no means entirely, changed. Those traditional flavours are likely nowadays to be richer and more concentrated, with better textures and finer tannins; the acidity is still there, but the greater concentration of flavour makes it less obvious.

The most international styles have a seasoning of vanilla and spice from new oak barriques, and the fruit leans more towards black cherry, plums and mulberries; where Cabernet Sauvignon joins the blend it is likely to be disproportionately dominant, with blackcurrant and plum flavours. These may become less noticeable as the wine ages.

Less ripe and concentrated Sangiovese can be stringy and rustic; that from warm climates can be heavier, broader and more alcoholic, tasting rather stewy and soupy and lacking the finesse of Tuscany’s finest.

New World flavours vary from oaky, plummy Cabernet lookalikes to attractively bright, cherry-fruited bottles to those with high alcohol but unripe tannins. None so far really have the poise and finesse of good Montalcino. Not for the first time, emulators have found it surprisingly difficult to capture the quintessence of Italy.

Brunello di Montalcino is now the world’s most famous and sought-after Sangiovese wine, but this success dates from as recently as the 1980s. It is well-deserved, since the best vineyards are fairly high, with infertile friable rocky soils. They are warmer than those of nearby Chianti, and also dryer, due to the looming Monte Amiata diverting most of the region’s bad weather away from the vines. Constanti’s 10ha (25 acres) of vines just below the hilltop town of Montalcino deliver consistently intense but elegant wines. Australia makes a richer, fruiter style, but Penfolds and others manage to keep the sweet sour Sangiovese character along with the juicier fruit.

MATCHING SANGIOVESE AND FOOD

Tuscany is where Sangiovese best expresses the qualities that can lead it, in the right circumstances, to be numbered among the great grapes of the world. And Tuscany is very much food-with-wine territory. Sangiovese-based wines such as Chianti, Rosso di Montalcino or Montepulciano, Vino Nobile and the biggest of them all, Brunello, positively demand to be drunk with food – such as bistecca alla fiorentina (succulent grilled T-bone steak), roast meats and game, calves’ liver, porcini mushrooms, casseroles, pizza, hearty pasta dishes and almost anything in a tomato sauce (Sangiovese’s acidity helps here), and tangy Pecorino cheese.

CONSUMER INFORMATION

Synonyms & local names

Also known (especially in Tuscany) as Sangioveto, Brunello or Prugnolo Gentile and Morellino. Corsica calls it Nielluccio.

Best producers

TUSCANY/Brunello di Montalcino

Agostini Pieri, Altesino, Argiano, Biondi-Santi, Brunelli, Camigliano, Caparzo, Casanova di Neri, Casanuova delle Cerbaie, Case Basse, Castelgiocando/Frescobaldi, Centolani, Cerbaiona, Ciacci Piccolomini d’Aragona, Donatella Cinelli Colombini, Col d’Orcia, Costanti, Fuligni, La Gerla, Greppone Mazzi, Lambardi, Lisini, Mastrojanni, Siro Pacenti, Pian dell’Orino, Pian delle Vigne, Piancornello, Pieve Santa Restituta/Gaja, La Poderina, Poggio Antico, Pogio San Polo, le Potazzine, Salvioni, San Giuseppe, Livio Sassetti, Scopetone, Sesti, Talenti, Valdicava, Villa Le Prata; Carmignano Ambra, Arteminio, Capezzana, Piaggia, Pratesi, Villa di Trefiano; Chianti Classico Riserva Ama, Antinori, Badia a Coltibuono, Bibbiano, Il Borghetto, Brancaia, Cacchiano, Capaccia, Carpineto, Casaloste, Castellare, Castell’in Villa, Collelungo, Colombaio di Cencio, Casa Emma, Felsina, Fonterutoli, Fontodi, Isole e Olena, Il Mandorlo, Monsanto, Il Palazzino, Paneretta, Panzanello, Poggerino, Poggio al Sole, Poggiopiano, Querciabella, Rampolla, Ricasoli, Riecine, Rietine, Rignana, Rocca di Castagnoli, San Felice, San Giusto a Rentennano, San Polo in Rosso, Casa Solo, Terrabianca, Vecchie Terre di Montefili, Vignamaggio, Villa Cafaggio, Villa Calcinaia, Villa Rosa; Chianti Rufina Basciano, Bossi, Colognole, Frascole, Frescobaldi, Grati/Villa di Vetrice, Grignano, Lavacchio, Selvapiana, Trebbio; Vino Nobile di Montepulciano Avignonesi, Bindella, Boscarelli, La Braccesca/Antinori, Le Casalte, La Ciarlana, Dei, Del Cerro, Fassatti, Gracchiano, Il Macchione, Nottola, Palazzo Vecchio, Poliziano, Redi, Romeo, Salcheto, Sanguineto I e II, Trerose, Valdipiatta; other central Italy Boccadigabbia, La Carraia, Castelluccio, Lungarotti, Zerbina.

GREECE Karipidis.

USA/California Alexander Valley Vineyards, Altamura, Bonny Doon, Frey, Monte Volpe, Ortman, Pedroncelli, Seghesio, Sobon Estate; New Mexico Luna Rossa; Washington State Cavatappi. Kiona, Leonetti, Long Shadows.

AUSTRALIA Brown Brothers, Cardinham Estate, Chapel Hill, Coriole, Crittenden, Greenstone, Oatley, Penfolds, Pizzini, Scaffidi, Stonehaven.

ARGENTINA Norton.

SOUTH AFRICA Bouchard Finlayson, Kleine Zalze, Morgenster.

RECOMMENDED WINES TO TRY

20 classic Tuscan reds (Sangiovese and with other Tuscan varieties)

Biondi-Santi Sassoalloro

Castello di Brolio Chianti Classico

Castellare I Sodi di San Niccolò

Fattoria di Felsina Fontalloro

Castello di Fonterutoli Chianti Classico Riserva

Fontodi Flaccianello

Frescobaldi Chianti Rufina Montesodi

Isole e Olena Cepparello

Castello di Lilliano Anagallis

La Massa Chianti Classico Giorgio Prima

Monte Bernardi Sa’etta

Montevertine Le Pergole Torte

Castello della Paneretta Quattrocentenario

Poggio Scalette Il Carbonaione

Fattoria Petrolo Torrione

Riecine La Gioia

Rocca di Montegrossi Geremia

San Giusto a Rentennano Percarlo

Selvapiana Chianti Rufina Riserva Vigneto Bucerchiale

Castello di Volpaia Coltassala

Five Tuscan Sangiovese-Bordeaux blends

Antinori Tignanello

Castello di Ama Chianti Classico La Casuccia

Castello di Fonterutoli Siepi

Querciabella Camartina

Poggerino Primamateria

Nine New World Sangiovese wines

Bouchard Finlayson Hannibal (South Africa)

Coriole McLaren Vale Sangiovese (Australia)

Dalle Valle Napa Valley Pietre Rosse (California)

Long Shadows Saggi (Washington State)

Leonetti Walla Walla Valley Sangiovese (Washington State)

Ortman Paso Robles (California)

Penfolds Cellar Reserve (Australia)

Pizzini Sangiovese Shiraz (Australia)

Seghesio Omaggio (California)

Intensive research is pushing the quality of Sangiovese further and further forward. We have probably not yet seen the best it can do – and if that applies to Tuscany, which it does, it applies even more to the New World.

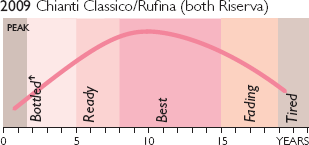

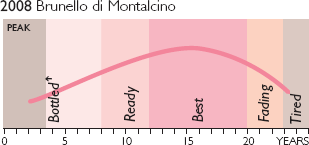

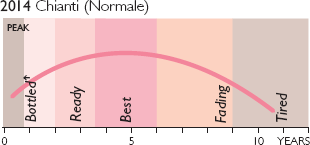

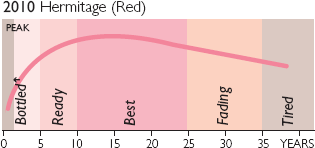

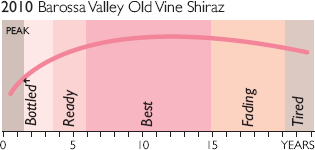

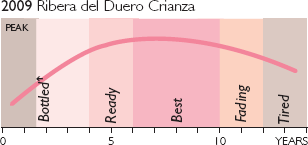

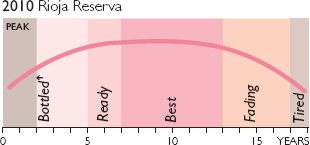

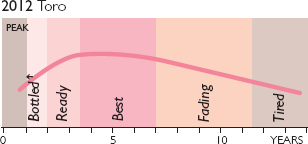

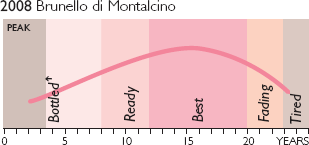

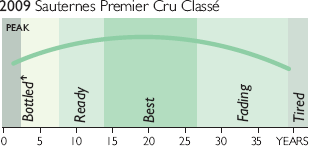

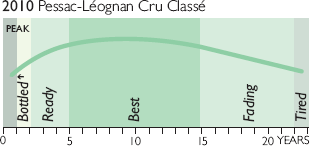

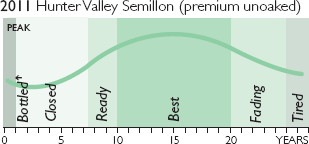

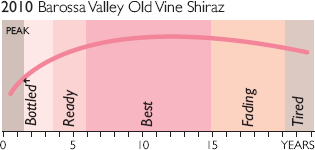

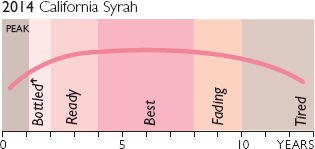

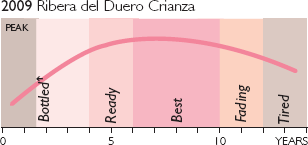

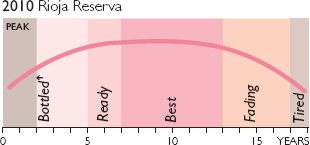

Maturity charts

Simple wines can and should be drunk within a few years; more concentrated, tannic versions need longer.

2009 was a hot, dry year in Tuscany, but the best Chiantis from the top estates are dark, ripe and long-lasting.

2008 was a hot year, but the heat wasn’t extreme and nights were cool, creating deep, balanced wine which will age well.

The 2011 vintage saw very difficult weather conditions in Tuscany; near drought in summer and blistering heat. Drink the wines young. .

SAUVIGNON BLANC

Sauvignon Blanc: from Grape to Glass

Geography and History here; Viticulture and Vinification here; Sauvignon Blanc around the World here; Enjoying Sauvignon Blanc here

A piece of the trellis from the potager garden at the château of Villandry illustrates the Loire Valley’s long association with Sauvignon Blanc. The flavours of Sauvignon Blanc are linked to myriad fruit and vegetables but none more so than gooseberries. Behind the trellis stretch the vineyards and hills of the Marlborough region in New Zealand’s South Island, the world’s new classic area for Sauvignon Blanc.

Why on earth does everyone make such a goddammed fuss about Sauvignon Blanc? Why can’t they let it be? After all, it’s such a simple grape, isn’t it? The wine’s not complex, it’s not intellectually challenging, it’s just a cracking good drink. You get a bottle, you whack it in the chiller, you whip off the screwcap, slosh it into everybody’s glass and – hey – crisp, pure, tangy, thirst-quenching, yum. What a great drink! And I mean drink. A good glass of Sauvignon Blanc is like a good Gin & Tonic or a good chilled pint of golden ale. Just drink it. That’s what it’s there for.

The trouble is, winemakers can’t leave well alone. They can’t quite believe that what their audience love so much is Sauvignon’s simplicity. Especially since a great part of Sauvignon’s appeal is in its slightly underripe citrous, leafy flavours in a world gone mad for ripeness and even overripeness. One of the most worrying dogmas in wine today is a determination to achieve maximum phenolic ripeness in the wine grapes, and abhor anything with a sniff of underripeness about it. People who bang on about maximum ripeness – I wonder, have they ever tasted a perfect pear, a perfect Cox’s apple or a perfect plum. Perfection is always at the ‘just ripe’ stage, never at the overripe stage.

The bigger argument with Sauvignon Blanc is between methoxypyrazine proponents and devotees of thiols. Sorry about the science. In bluntest terms, methoxypyrazines are the green element in Sauvignon’s flavours, whereas thiols are the more exotic, tropical (if you’re lucky) passion fruit flavours – if you’re not lucky, armpit. I mean it. And not a washed one, either. I call Sauvignon a green grape – one that revels in the cool side of its personality, the green side, and one which is therefore almost always at its best coming from cool areas and cool vintages. The great classic cool area is Marlborough in New Zealand’s South Island, followed by the cool coastal regions of South Africa and Chile. Grapes have a natural green quality from those areas. They also get decently ripe because the sun shines most of the time. And that makes it possible to keep crunchy, lime zesty, leafy freshness in the wine and add just a little exotic passion fruit and nectarine ripeness. Doesn’t that make your mouth water? Well, that’s probably the perfect style.

It’s strange saying that the great classic areas for Sauvignon are places where grapes were hardly planted 30 years ago, sometimes hardly planted 10 years ago. But it’s true. Sauvignon Blanc has been growing in Bordeaux and the Loire Valley for centuries. Bordeaux has made some great wines from it in Pessac-Léognan, but only as part of a blend with Semillon. The Loire made the most famous Sauvignons in pre-New Zealand history, but they had names like Sancerre or Pouilly Blanc Fumé – they never mentioned the grape’s name on the label, so you didn’t know you were drinking it.

It took the South Island of New Zealand, and the Marlborough region in particular, to show Sauvignon’s astonishing flavours. This was an entirely new wine area with no terroir, no history, no reputation to protect. People realized that this brilliant, pungent, aggressively green yet exotically ripe style of wine was unlike anything the world had ever seen before. There had never been a wine with such outspoken, cut-glass purity of flavours whose whole purpose is to be refreshing and pleasurable.

I think it’s fair to say that New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc changed the wine world by changing our ideas of what wine could be like, just as the Chardonnays of California and Australia did. And for a long time these two wines occupied seats in the opposite corners of the White Wine boxing ring: the pungent, green, aggressive Sauvignon, bare and unoaked, and the warm, round, soft, creamy, spicy, tropical Chardonnay with oak a key part of its attraction. Now, many other varieties are filling in the gaps between the two, but in the early years of the Wine Revolution, when we looked for leaders we found two whites – sexy Chardonnay, swathed in oak, and Sauvignon, naked as nature intended – and with attitude. Chardonnay has already started to reinvent itself in a perkier, less oaky style. Let’s leave Sauvignon as it is.

GEOGRAPHY AND HISTORY

I’m tempted to say there’s no geography and no history of Sauvignon Blanc before 1973. That’s when the first Sauvignon vines were planted in the Marlborough region of New Zealand’s South Island. Within a few years they’d produced a wine of such shocking, tongue-tingling pungency that the world of wine was never the same again. Well, I’m tempted, but in fact Sauvignon Blanc had been around elsewhere for donkey’s years, except that it never gave a wine with half so much excitement as New Zealand’s offerings, and you virtually never saw the name Sauvignon on the label, so in any case you probably didn’t know you were drinking it.

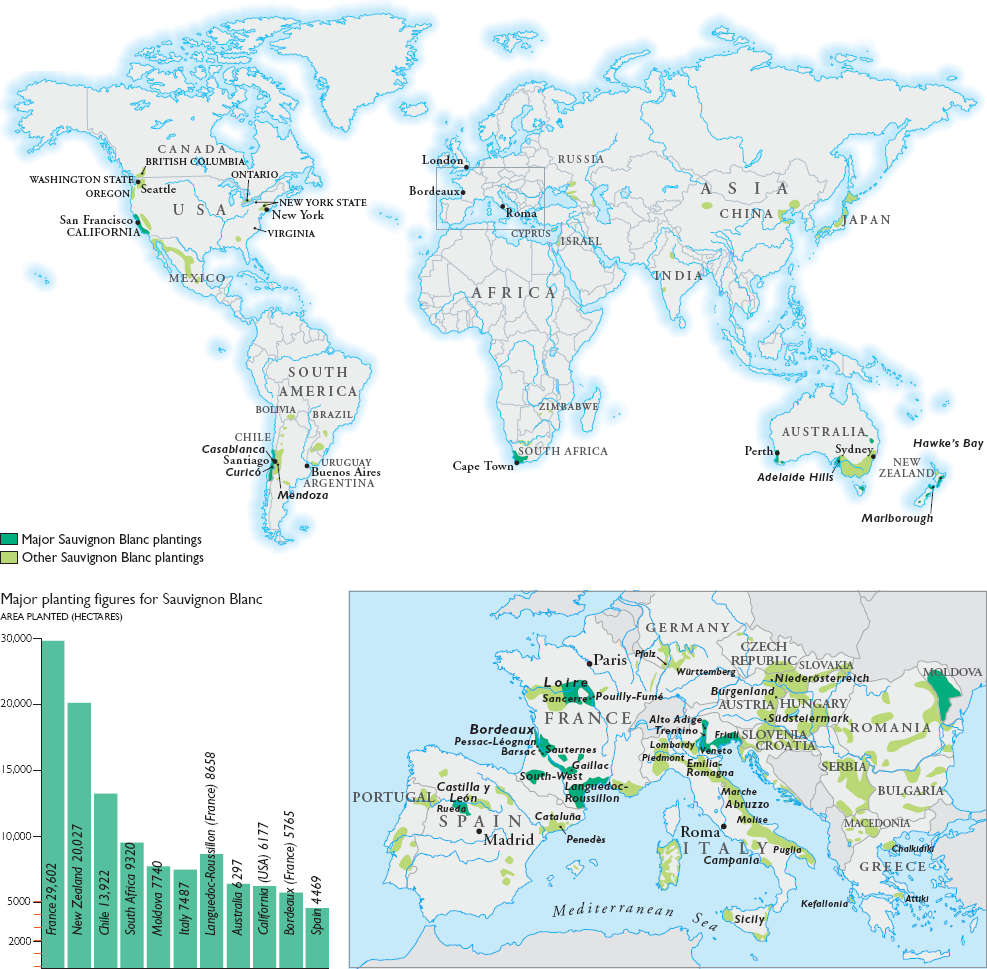

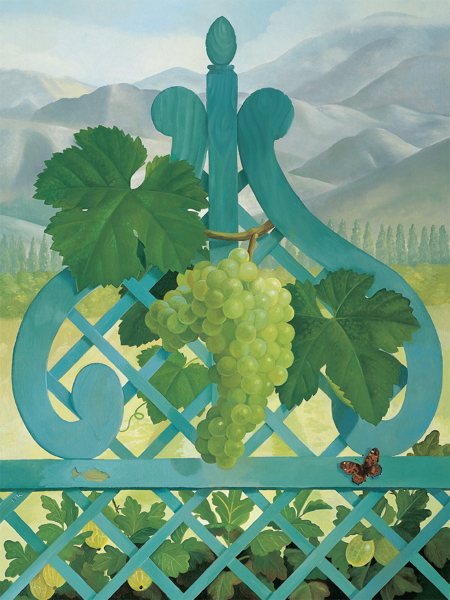

But look at the map – it’s all over the place. New Zealand, sure, Australia, South Africa, Chile, northern Italy, Hungary, the Loire Valley, Bordeaux – almost everywhere you look you’ll find Sauvignon planted. Which might imply it’s a marvellously adaptable grape. But in fact it isn’t. Sauvignon Blanc is, in fact, quite picky about its site, and what we’re seeing at the moment is a sorting-out of styles, with only some places succeeding.

New Zealand, which first made us realize what Sauvignon could do, is suffering from a bit of an attack of confidence. Having shown the world how good Sauvignon could be, producers are now striving to find different experiences and flavours. I’d say: remember what made you famous in the first place; the audience still love it. By all means search for different sites and conditions which will naturally produce different flavours, but don’t try to force the issue. Rant over.

Drier, sometimes tangy, sometimes more delicate, more subtle wines are appearing from South Africa in a variety of areas, both coastal and inland. Chile’s coastal sites are providing real zing. Australia, with a few exceptions, is proving that Sauvignon grows better elsewhere. And California struggles gamely on. France just keeps on going much the same as usual.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Both southwest France and the Loire Valley claim Sauvignon Blanc as an indigenous grape. The Loire looks more likely, but at some time in or before the 18th century, and presumably in Bordeaux, it got together with Cabernet Franc to produce the seedling that became known as Cabernet Sauvignon, and if it had done nothing else in its existence, wine lovers would have to thank it for that.

Its current fame in the southwest, however, is of quite recent date. Until the late 1980s it languished behind Sémillon and Ugni Blanc in terms of the numbers of hectares planted and its wine was generally rather raw and earthy. If it did indeed originate in the southwest and spread from there to the Loire (the opposite seems more likely), then we would have a rare instance of the sort of happy accident by which a vine that produces generally indifferent wine at home (and frankly ‘indifferent’ is high praise for most of the Bordeaux Sauvignon that was creeping out into the critical spotlight until the 1990s) suddenly excels elsewhere.

The Sauvignon Blanc planted in Bordeaux in the 19th century must have been mixed up with Sauvignon Vert, alias Sauvigonasse, a pretty uninspired poor relation of the real Sauvignon. Since Chile got its Sauvignon from Bordeaux cuttings before phylloxera and the two were mixed up there, it is reasonable to assume its field blend was inherited.

There is also a pink mutation of Sauvignon Blanc, known as Sauvignon Gris: Chile and Bordeaux both have some of this. It gives 20 per cent lower yields than Sauvignon Blanc, one degree more alcohol and a less pungent but spicier aroma. The berries are more deeply coloured than those of Sauvignon Blanc. However, Sauvignon Gris seems not to be the same as the Sauvignon Rouge mutation found in small quantities in the Loire. And modern history – well, that started in New Zealand, in 1973.

Vineyards in the rolling hills above Bué and Venoize in the Sancerre appellation in the eastern Loire Valley. There are 14 different communes in the appellation, so wine styles are necessarily heterogeneous. In fact, the much-vaunted differences between Sancerre and Pouilly-Fumé are far less than the differences to be found within the Sancerre appellation, with its varying soil types and its hills that rise to 400m (1320ft).

Pale chalky soils – these are at Bué – are crucial to the freshness and minerality of the best Sancerres, and their alkaline nature gives finely balanced, sharply focused flavours.

The late Didier Dagueneau was always the Pouilly-Fumé producer most determined to push the boundaries. Here his son Benjamin shows off his new egg-shaped oak fermenter.

VITICULTURE AND VINIFICATION

The ideal style of Sauvignon Blanc seems to be up for grabs at the moment. There are far fewer really raw, green, underripe flavours around. The good greenness you’ll find is that of nettles, blackcurrant leaves, lime zest and green apple skins – thrillingly refreshing, when you can find it. But there is a trend to greater ripeness, and that brings a risk of low acidity which some producers correct by throwing buckets of tartaric acid into the vat. It sort of works – but you can taste the acidity separately if they’ve been too enthusiastic. Overripe Sauvignon goes oily, sweaty and over-rich, which is even less nice. So warmer regions just don’t suit it. Many producers in Australia, New Zealand and South Africa deal with the problem by picking at different levels of ripeness – some underripe, some perfectly ripe, and some overripe. Done cleverly, this can produce palate-tingling wines of seamless balance. But why not plant the vines in a cool but sunny spot in the first place?

Climate

To get that too-often-elusive balance between sugar ripeness, acidity and aroma, the right climate is crucial. Once you’ve got it then the soil can certainly influence the flavour of Sauvignon; but the climate must be the first priority for anyone thinking of planting Sauvignon Blanc.

It’s both a late budder and an early ripener: it doesn’t therefore need enormous heat. In France it flourishes in both the maritime climate of Bordeaux and the more continental climate of Sancerre in the Loire Valley; New Zealand’s climates, too, are maritime. Slow ripening gives better flavour development, but optimum aroma occurs just before optimum sugar ripeness. This is important. The greatest intensity of aroma is found just before the ideal balance of sugar and acidity; choosing the picking date means a slight compromise in one direction or the other. Ideally, it should, of course, be as slight as possible. Part of the improvement in quality in Sancerre in recent years has been produced by better-judged picking dates; and while logically these should be later, since the wines clearly taste riper, better balanced and more interesting than they did, most growers, when questioned, claim they pick earlier. Global warming, they say, has advanced the maturity of the grapes. I’d say awareness of the success of Sauvignon from New Zealand’s South Island is an equally likely answer.

In New Zealand, different systems of canopy management have been aimed at producing riper grapes in a cool but sunny climate and with soils of high potential vigour. Fatter, more tropical wines have become common, but with raised levels, too, of residual sugar. There’s a bit of a battle going on between the green, zesty champions and the tropical fruit boys. Since New Zealand set a world standard for tangy, citrus styles that other wine countries desperately try to copy, the move to a fatter, riper, indeed sometimes sweaty style is bonkers.

In warmer climates growers generally pick early to keep acidity in their grapes, but in so doing seldom get the best aromas. California is a classic example: few of its Sauvignon Blanc wines have any character, so much so that the belief that Americans don’t like Sauvignon Blanc becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

In Chile, many winemakers pick Sauvignon Blanc at several different times: unripe for grapes with high malic acid; riper for red and green pepper flavours; at perfect ripeness, and at overripeness. Where did they learn such habits? Why, the South Island of New Zealand, and as some New Zealand producers try to soften up their wines they should remember the original, brilliant formula.

Soil

The question of soil and Sauvignon Blanc is really confined to France, with a glance at New Zealand; no other countries pay such attention to the issue.

In the Loire Valley soils in Sancerre and neighbouring Pouilly vary from chalk over Kimmeridgean marl – this produces the best balanced wines, with richness and complexity – to the compact chalk, or caillotte, found at the base of the hills – this gives finesse and perfume – to flint, or silex, which gives wines with a certain gunflint sparkiness and vigour. There are also warm terraces of sandy or gravelly soil near the river which give spicy, floral flavours to wines which are the earliest maturing of all. Marl gives wines that age better, but the longest-lasting wines come from silex.

In Bordeaux the soils usually allotted to Sauvignon are more alluvial and produce high yields, which accounts for the lesser pungency of the wine here.

In New Zealand’s Marlborough region the soils are particularly varied. Stony or sandy soils over shingle with poor fertility and good drainage compete with heavier, fertile clays and fertile silt. All produce good but different styles of Sauvignon. Further south in the Awatere Valley a mixture of silt loams, gravels and sands produce exciting results, and there is even limestone in the Ure Valley.

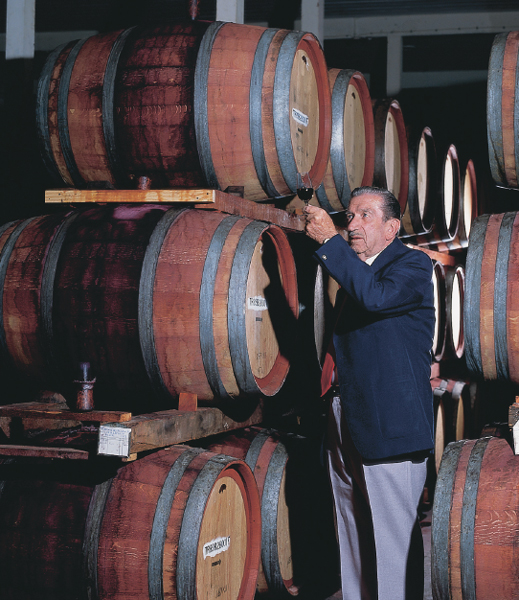

Kevin Judd was the original winemaker at mould-breaking Cloudy Bay in Marlborough, New Zealand, whose startling Sauvignon Blanc changed our wine world for ever. Now he has a new winery, Greywacke, also in Marlborough. Here he is taking a bit of a nap on some old barrels containing Wild Sauvignon. The dog looks thirsty.

In the Sauvignon Blanc heartland of the flood plain of the Wairau Valley soil types, both fertile and infertile, run in bands that go from east to west. This means that if vines are planted from north to south, then a single row can contain vigorous, late-ripening vines with large canopies and weaker, early-ripening ones with small canopies. Interestingly, this mix of weak and strong, of tropical and citrus, unripe and ripe, can produce really interesting, pungent stuff. The heavier soils tend to be later ripening, and give more herbaceous flavours; stony soils are warmer and thus earlier ripening, and give riper, lusher flavours. Mix them cleverly and you’ve got pungency plus ripeness.

Sauvignon Blanc vines at Montana’s Brancott Estate near Blenheim, Marlborough – the original Sauvignon vineyard in the South Island. Blenheim usually gets more sunshine hours than any other town in New Zealand, thanks to the Southern Alps, which provide a handy rain shadow. Yet it’s still quite cool in viticultural terms, so Sauvignon Blanc doesn’t race to overripeness and flabbiness.

Yields

If what you’re after with Sauvignon Blanc is aromatic, crisp, fresh wine for early drinking, then yields are not an enormous problem. The maximum yield in Sancerre is 68hl/ha, including the plafond limite de classement, by which growers are allowed an increase in yield in prolific years, and actually Sauvignon Blanc tolerates these sort of levels reasonably well. If you want more serious, fatter, weightier wines, ones that will last and improve for several years, then 50hl/ha is enough. At 40hl/ha the wine may well be very serious, with extract and staying power, but it will not be most people’s idea of Sancerre. Yields are lower than this at good Graves and Pessac-Léognan estates in Bordeaux: under 40hl/ha at a few estates, notably Château Pape-Clément, but more usually between 40hl/ha and 55hl/ha. Since most top Bordeaux whites are barrel-fermented, these lower yields are crucial for a deep, balanced, ageworthy wine.

In the New World yields are higher again: at least six tons per acre (108hl/ha) in California, and around 8–12 tonnes per hectare (58–87hl/ha) even in Chile’s relatively low-yielding Casablanca Valley. In the Central Valley yields can top 15 tonnes per hectare (109hl/ha).

At the winery

Fermentation temperatures are a major point of difference between producing Sauvignon in the Loire Valley and the New World. In the Loire, fermentation (either in steel or wood) is at 16–18°C (61–64°F), in order to avoid the tropical fruit aromas that the New World seeks with its cooler temperatures. These relatively warm fermentations produce wines that are minerally rather than exuberantly fruity: Loire winemakers prefer their wines to reflect their terroir rather than the grape variety.

Denis Dubourdieu, Professor of Enology at Bordeaux University and high priest of Sauvignon, whose work has lifted Bordeaux Sauvignon to a level inconceivable 20 years ago, points out that it is the peaks of temperature during barrel fermentation – these peaks can touch 25°C (77°F) – which give richness and varietal aroma to the wine. Fermentation in stainless steel, with tightly controlled temperatures, gives wines with fewer terroir characteristics but the potential for explosive varietal fruit.

But there are far more ways of tinkering with Sauvignon in the winery than merely adjusting fermentation temperatures. Pre-fermentation skin contact is used by some producers for more expressive fruit flavours.

When South Island New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc first hurled itself on to our unsuspecting palate with thrilling flavours of gooseberry, green pepper, asparagus and passionfruit, one reason for the wine’s intensity was an unavoidable period of skin contact. Why? Well: there were no wineries at the time in the whole of South Island and grapes had to travel by truck and ferry all the way to Auckland up through North Island. At the height of harvest time that could mean grapes and juice sloshing around together for up to 24 hours. A wine of particular pungency could always be blamed on a traffic jam at the ferry.

The gooseberry/green pepper/lime zest flavours come from a group of flavour compounds called methoxypyrazines, which can be created, even in warmer areas, by shading the grapes from the sun. Many producers now eschew methoxypyrazines in favour of the more tropical-tasting, lusher thiols, but these carry with them an ever-present threat of armpit sweat. A skilful viticulturalist will try to balance the canopy shading to maximize the good points of both.

Aging on the fine lees works well: the lees protect against oxidation, and if the wine is in barrel they prevent it from becoming too oaky. Bâtonnage is used to increase weight; there is even some malolactic fermentation and new oak creeping into the Loire, though the style is atypical and I don’t find the addition of creaminess and the reduction in tangy acidity that malolactic brings to be a particularly attractive objective. New oak is more usually thought of as belonging to Bordeaux and the New World: the term Fumé Blanc, which has no legal meaning, may be applied to New World Sauvignons (or indeed wines from other white grapes) with new oak aging. Most of the examples come from California where the term originated. I suppose the idea for the name came from Pouilly-Blanc Fumé in the Loire, but the flavours of these wines have nothing whatever to do with traditional Loire Sauvignon Blanc.

SAUVIGNON BLANC AROUND THE WORLD

Frankly, I generally prefer my Sauvignon Blanc as a pure thrilling blast of all the grape has to offer – unashamed, unblended, love it or loathe it. But some faint hearts prefer to temper the wine’s fierceness by blending – and Sémillon is usually the grape of choice. Indeed, in Pessac-Léognan, even I actually prefer the Sémillon-Sauvignon Blanc blend.

France: Loire Valley

The finest appellations here for Sauvignon Blanc are Sancerre and its neighbour, Pouilly-Fumé; and in spite of the tradition that Pouilly-Fumé is marked by a characteristic whiff of gunflint, the difference between the two wines is less than differences found between Sancerre’s different soils and villages. The ‘Fumé’ was appended to Pouilly to distinguish the area’s Sauvignon from its Chasselas, which has the AC of Pouilly-sur-Loire.

At the moment Sancerre is a more go-ahead AC than Pouilly-Fumé. The older style of grassy, gooseberryish fruit is being replaced by richer, more peach and melon notes. The growers of the Loire have certainly been spurred into doing better by the success of New Zealand’s South Island. New Zealand Sauvignon is not made in a style they admire. They want to achieve something different. Hmm. That’s fair enough. But I would suggest that their first step towards making the best wine they can might be to respect New Zealand’s brilliance, rather than turn their noses up at it.

Lesser, but cheaper, and attractive, distinctive wines are produced nearby in Quincy, Reuilly and Menetou-Salon. These are snappy, fresh wines, but lack the depth of a good Sancerre or Pouilly-Fumé: Quincy is the most intense and gooseberryish; Reuilly and Menetou-Salon have some of the Sancerre snap and nettly tang; Touraine Sauvignon is satisfyingly green and crunchy.

France: Bordeaux

Denis Dubourdieu, Professor of Enology at Bordeaux university and highly respected enologist, has been the greatest single influence behind the enormous improvement in quality of Sauvignon Blanc at all levels. Winemaking, viticulture and clones have all improved, particularly in the last 10 years; even basic Bordeaux Blanc (which may be 100 per cent Sauvignon or Sémillon, or a blend of Sauvignon and Sémillon with or without a little Muscadelle) is now pretty reliably fresh. The scented dry white wines of the Graves and Pessac-Léognan are often fermented and aged in new oak.

In the sweet wine appellations of Sauternes, Barsac, Loupiac, Cérons, Cadillac and Ste-Croix-du-Mont, the proportion of Sauvignon Blanc in the vineyards varies between 10 and 40 per cent. Its thin skin makes it highly susceptible to botrytis, and its acidity adds freshness to the blend.

Rest of France

Sauvignon Blanc is widely planted throughout the southwest, and is particularly successful in Gascony and the Dordogne. In the Languedoc it is fairly popular for IGP wines, usually made in a slightly fat, fruity style. However, the warm climate and high yields combine to make it difficult to produce tangy Sauvignon with Loire-style aroma and freshness though there are one or two standouts. Burgundy has one tiny outpost at St-Bris near Chablis.

Rest of Europe

Spain’s most notable Sauvignon Blanc comes from the Rueda DO in Castilla y León, where it was introduced in the early 1980s. Styles are ripe, but the peachy fruit is balanced by a nettly acidity, usually achieved by picking the grapes as early as August. Some new oak may be used. It is also an authorized variety for the La Mancha and Rioja DOs.

Austrian versions of Sauvignon Blanc often have classic nettly, blackcurrant-leaves fruit, and restrained, understated, often excellent wines come from the Sudsteiermark region.

It is not known when Sauvignon Blanc was first planted in Italy, but it seems, in its early days at least, to have been grown alongside Sauvignonasse. Its first port of call was in Piedmont, although such Sauvignon Blanc as is made there today (there isn’t much, and Gaja’s is the best) was planted in the 1980s and 1990s. It is a grape of the Italian North and produces its most typical varietal aromas further east, in Collio, Friuli and Alto Adige. Italian producers may make Sauvignon as a varietal, or they may blend it with anything and everything: Chardonnay, Müller-Thurgau, Ribolla, Picolit, Vermentino, Inzolia, Tocai, Malvazia Istriana, Pinot Bianco and Erbamatt (a very rare white from Lake Garda).

The grape has potential for good quality in central and eastern Europe; there are large plantings in Romania and Moldova; the Czech Republic, Slovenia and, especially, Hungary are making appetizing wines.

Alphonse Mellot

Wine from 87-year-old vines in the La Moussière vineyard, fermented and aged in 900-litre vats to mark the 19th generation of winemaking Mellots.

Château Couhins-Lurton

This property produces a wonderfully rich and intense barrel-fermented Sauvignon Blanc which, unlike most Pessac-Léognan wines, contains no Sémillon.

Cloudy Bay

The most famous New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc of them all, Cloudy Bay achieved instant cult status with its first vintage in 1985.

New Zealand

The first Sauvignon Blanc was not planted in Marlborough, in the South Island, until the 1970s, when Montana made the inspired decision to plant a trial plot. The main attraction of this then little-known region was its cheapness, and its possible suitability for Müller-Thurgau, then a far more important vine in New Zealand. Montana’s first Marlborough Sauvignon was made in 1980; it is now the leading region for the grape. The typical Marlborough style of Sauvignon Blanc – the climate is cool, dry and sunny – is distinctly tangy and citrussy, though some producers now seek more tropical fruit. The Awatere subzone to the south produces Marlborough’s sharpest, most mouthwatering Sauvignons, lime zest fresh with tomato leaf and green capsicum crunch. Elsewhere in the South Island, Nelson’s wines are softer, but citrous and Central Otago’s are bitingly fresh. In the North Island, Hawkes Bay wines are mellow and some Wairarapa examples are tangy and earthy.

Chile and South America

Much of Chile’s original Sauvignon Blanc is in fact Sauvignonasse, though just how much is not clear: a distinction between the two varieties was made in the early 1990s. Plantings after about 1995 are of Sauvignon Blanc proper. The leading region though not the largest, is the cool Casablanca Valley, where plantings began in about 1990, but far more is planted further south in the Central Valley in much hotter conditions. Casablanca, with its Mediterranean climate, has similar daily temperature variation to Marlborough. The new regions, where everybody is scrambling to find land and grapes, are nearby San Antonio and Leyda, Limarí, coastal Aconcagua and several other new, chilly coastal locations, as well as Bío-Bío and further south. The wines are light and crisp but intense, with flavours ranging from gooseberry, mint and tomato leaf to light green melon and crunchy apple flesh and greengage plums. Sauvignon Blanc is also found in Mexico, Argentina, Uruguay and Bolivia. In Brazil, according to Galet, the vine called Sauvignon Blanc is really Seyval Blanc.

Wine was first made at Steenberg in Constantia in 1695. Vines were replanted in the 1990s as it became clear that the vineyards were ideally suited to cool climate varieties, with False Bay (seen in the distance) chilling the air and slowing ripeness. These vines produce one of South Africa’s best Sauvignon Blancs.

Australia

Australia isn’t a Sauvignon paradise. There are good examples from Adelaide Hills, Padthaway, Orange and Tasmania, and Margaret River, in Western Australia, makes some excellent blends with Semillon. But on the whole one has to wonder if Australia is really suited to it. Most wines are simple and may taste slightly confected.

USA

Sauvignon Blanc is widely planted in California and even though it is now the third most planted white grape, it still lies way behind Chardonnay and French Colombard. Oaked versions of the wine often use the name Fumé Blanc. There is some in Washington State and Oregon, but acreage is declining. It is also planted on Long Island, New York State, and in Virginia.

South Africa

Vivid flavours of nettles, herbs, lime zest and gooseberries are common here. In the last decade, South Africa has become one of the world’s most stylish Sauvignon producers, by making a considerable effort in identifying numerous different sites which give a variety of fascinating flavours, sometimes green but gentle, sometimes really crunchy. The West Coast north of Durbanville, and the far south near Cape Aghulas, produce the tangier styles, but the gentler delights come from Elgin, Constantia, Robertson and Stellenbosch.

Casa Marin

Chile has outstanding growing conditions for Sauvignon near the coast, where stiff Pacific breezes keep temperatures down and freshness up.

Henschke

Henschke are better known for their profound Shiraz reds, but they also take advantage of the cool Adelaide Hills to produce crisp Sauvignon.

The Berrio

Wonderfully snappy Sauvignon from Elim, on the tip of Africa, where breezes from the Antarctic Benguela Current provide chilly conditions.

ENJOYING SAUVIGNON BLANC

Generally speaking, Sauvignon Blanc is not a wine made to last. Its attraction is its youthful freshness and zest, and the fact that it can be drunk immediately, in the spring following the harvest. Most Sauvignon Blancs, if kept longer than a couple of years, fade rapidly and lose their aroma.

Those that will improve in bottle come not just from particular areas but from particular growers who take a decision to make a wine for keeping. This means, first and foremost, restricting yields: serious, ageworthy wines do not come from the same generous crops as light, early-drinking ones.

The best Marlborough Sauvignon Blancs intensify their flavours for between five and 10 years, depending on the vintage. Top Sancerres and Pouilly-Fumés can develop in bottle for five to eight years, developing flavours of honey and toast to replace those of nettly fruit, but always keeping a mineral streak; top white Graves and Pessac-Léognan change dramatically with age. They often start out with nettly acidity, bright nectarine fruit and gentle custardy oak and change over 10 to 15 years to magnificently deep nutty, creamy wines. Domaine de Chevalier, Smith-Haut-Lafitte, Malartic-Lagravière, Haut-Brion and Laville-Haut-Brion can last even longer, and may well stay in excellent shape for 20 years or even longer.

Sweet wines are made from blends of Sauvignon and Sémillon in Sauternes and Barsac, and sometimes from pure Sauvignon in California and New Zealand. Classed growth Sauternes reach maturity after a decade or so, but are nevertheless delicious younger; California and New Zealand sweet versions vary in their ageability, but most will improve for up to five years. Top Australian examples are beautiful at two to three years, but should age for a decade or so.

The taste of Sauvignon Blanc

When I’m trying to describe why I absolutely love the flavour of Sauvignon Blanc, I have to accept it’s one of those grapes some wine people simply can’t stand. That’s okay. They don’t have to drink it. All I ask is that they don’t try to change it into something bland and soft or they’ll find me challenging them to a furious fistfight. I love its taste of gooseberries, its taste of green peppers sliced with a silver knife, passion fruit and kiwi scattered with lime zest, nettles crushed up with blackcurrant leaves. These are the kind of flavours that make Sauvignon for me irresistibly refreshing.

If you like riper tastes, well, Sauvignon develops a spectrum of white peach, nectarine and melon masking any excess acidity; wines with a touch of botrytis may have a whiff of apricot. Sancerre and Pouilly-Fumé often have a minerally streak, particularly if they are grown on flinty silex soil: generally clay gives more richness, chalk lightness and perfume.

Lower fermentation temperatures produce a range of tropical fruit flavours: pineapple, banana and guava – dangerous unless balanced by good acidity.

New oak aging will give the wines a vanilla sheen; malolactic fermentation may add butter to the palate. With bottle age Sauvignon takes on tastes of honey and toast and quince, less obviously fruity, but rich and complex.

Botrytized sweet wines have flavours of pineapple and marzipan, oranges and apricots, with often piercing acidity to cut through the richness.

Although Sauvignon Blanc originates in Western France, its modern fame rests squarely on New Zealand’s shoulders. New Zealand Sauvignon hit the world in the 1980s with tingling, mouthwatering green fruit and a citrussy attack that virtually ushered in an entire new era of modern white wine. Astrolabe continue the tradition in the coolest part of Marlborough on the South Island – Awatere Valley, dry, challenging and open to the cold southern winds. Domaine de Chevalier makes one of France’s classier, barrel-fermented whites by blending 30% Semillon in with the Sauvignon Blanc – a practice also copied in other parts of the world like California, South Africa, Western Australia and New Zealand.

MATCHING SAUVIGNON BLANC AND FOOD

This grape makes wines with enough bite and sharpness to accompany quite rich fish dishes as well as being an obvious choice for seafood and for Thai dishes. The characteristic acid intensity makes a brilliant match with dishes made with tomato, but the best match of all is white Sancerre or Pouilly-Fumé with the local sharp crottin goats’ cheese of the Upper Loire Valley. With their strong, gooseberry-fresh taste, Sauvignons make good thirst-quenching apéritifs.

CONSUMER INFORMATION

Synonyms & local names

Sometimes called Blanc Fumé in the central Loire; there are variations called Jaune, Noir, Rose or Gris and Violet according to the berry colour; it is called Muskat-Silvaner or Muskat-Sylvaner in Germany and Austria (though Steiermark often uses the name Sauvignon Blanc); oaked versions are also known as Fumé Blanc in California and Australia. The variety Sauvignon Vert or Sauvignonasse is unrelated.

Best producers

FRANCE/Pouilly-Fumé J-C Chatelain, Didier Dagueneau, Ladoucette, Masson-Blondelet, de Tracy; Sancerre G Boulay, H Bourgeois, F Cotat, F Crochet, Alphonse Mellot, Vacheron; Bordeaux/Pessac-Léognan Brown, Dom. de Chevalier, Couhins-Lurton, Fieuzal, Haut-Brion, la Louvière, Malartic-Lagravière, Smith-Haut-Lafitte; Graves Clos Floridène.

ITALY Colterenzio co-op, Peter Dipoli, Edi Kante, Lageder, Vie di Romans, Villa Russiz.

AUSTRIA Gross, Lackner-Tinnacher, Neumeister, Polz, E Sabathi, Sattlerhof, E & M Tement.

SPAIN Hermanos Lurton, Palacio de Bornos, Marqués de Riscal, Javier Sanz, Sitios de Bodega, Torres.

USA/California Araujo, Brander, Coquerel, Dry Creek, Flora Springs, Grgich Hills, Heitz, Honig, Kenwood, Mondavi, St Supery, Spottswoode.

AUSTRALIA Angullong, Bannockburn, Bird in Hand, Brookland Valley, Larry Cherubino, De Bortoli, Hanging Rock, Houghton, Karribindi, Katnook, Lenton Brae, Logan, Longview, Nepenthe, S C Pannell, Philip Shaw, Shaw & Smith, Stella Bella, Tamar Ridge, Word of Mouth.

NEW ZEALAND Astrolabe, Blind River, Brancott, Cloudy Bay, Dog Point, Gladstone, Greywacke, Lawson’s Dry Hills, Man O’War, Matua Valley, Neudorf, Palliser, Pegasus Bay, Sacred Hill, Saint Clair, Stoneleigh, Te Kairanga, Te Mata, TerraVin, Vavasour, Villa Maria, Yealands.

CHILE Casa Marín, Casas del Bosque, Concha y Toro, Cono Sur (20 Barrels), Errázuriz, O Fournier, Viña Leyda, Luis Felipe Edwards, Montes, San Pedro (Castillo de Molina), Santa Rita (Floresta), Undurraga.

SOUTH AFRICA Graham Beck, Cape Point, Cedarberg Ghost Corner, Constantia Glen, Neil Ellis, Flagstone, Fleur du Cap, Fryer’s Cove, Hermanuspietersfontein, Iona, Klein Constantia, Mulderbosch, Oak Valley, Quoin Rock, Springfield, Steenberg, Thelema, Vergelegen.

RECOMMENDED WINES TO TRY

Ten New Zealand Sauvignon wines

Astrolabe Marlborough

Blind River Marlborough

Cloudy Bay Marlborough

Dog Point Marlborough

Te Kairanga Wairarapa

Greywacke Marlborough

Saint Clair Marlborough

Vavasour Marlborough Single Vineyard

Villa Maria Marlborough Clifford Bay Reserve

Yealands Marlborough

Five classic Loire Sauvignon wines

J-C Chatelain Pouilly-Fumé

Francis & Paul Cotat Sancerre Chavignol la Grande Côte

Lucien Crochet Sancerre Cuvée Prestige

Didier Dagueneau Pouilly-Fumé Pur Sang

Alphonse Mellot Sancerre Cuvée Edmond

Eight classic Sauvignon-dominated dry white Bordeaux wines

Ch. Brown Pessac-Léognan

Domaine de Chevalier Pessac-Léognan

Ch. Couhins-Lurton Pessac-Léognan

Ch. la Louvière Pessac-Léognan

Ch. Malartic-Lagravière Pessac-Léognan

Ch. Margaux Bordeaux Pavillon Blanc

Ch. Pape-Clément Pessac-Léognan

Ch. Smith-Haut-Lafitte Pessac-Léognan

Eleven other New World Sauvignon wines

Casa Marín Cipreses (Chile)

Cederberg Ghost Corner Sauvignon Blanc (South Africa)

Concha y Toro Terrunyo (Chile)

Errázuriz Aconcagua Coastal (Chile)

O Fournier Centauri (Chile)

Luis Felipe Edwards Marea de Leyda (Chile)

Montes Outer Limits (Chile)

Viña Leyda Sauvignon Blanc (Garuma) (Chile)

Shaw & Smith Sauvignon Blanc (Australia)

Steenberg Black Swan (South Africa)

Vergelegen Sauvignon Blanc (South Africa)

The exciting thing about Sauvignon Blanc is its wonderful, unabashed fruit salad bowlful of flavours, all tumbling over one another. These tastes are most obvious when the wine is young, but, especially when barrel-fermented and blended with Sémillon, Sauvignon can produce deep, complex, long-lasting wines.

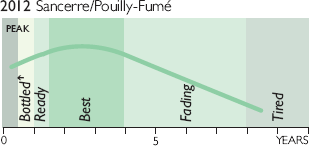

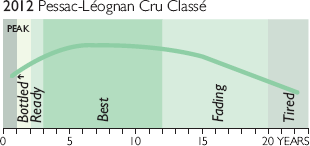

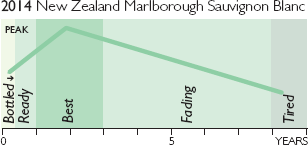

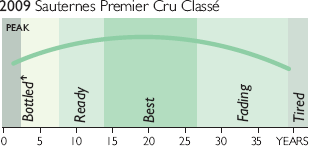

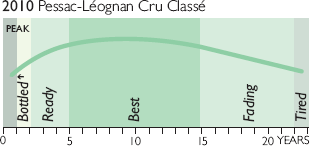

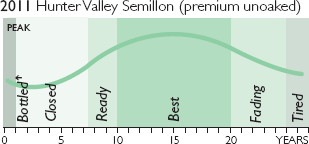

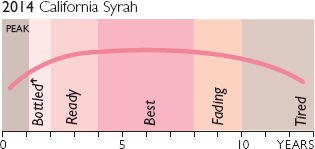

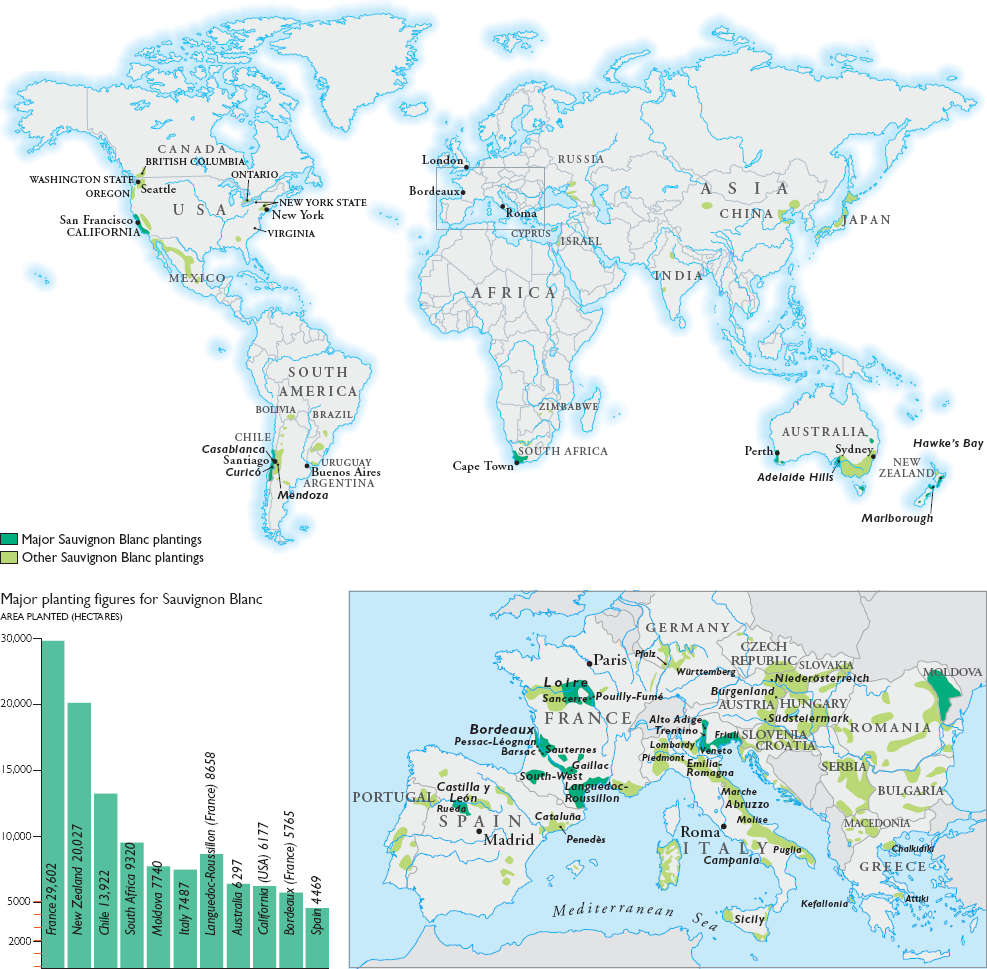

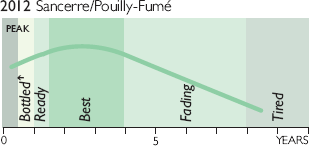

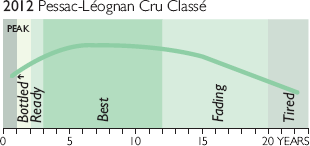

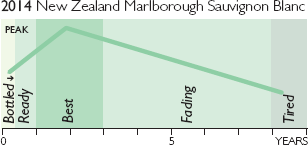

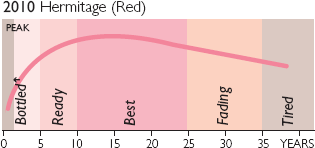

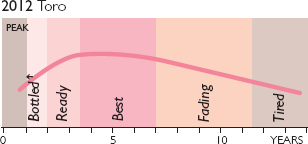

Maturity charts

Sauvignon is usually made for early drinking, though some Sancerres and Pouilly-Fumés will keep and improve for much longer.

A few producers make Sancerre that will age in bottle, but generally it is a light, fresh wine intended for early drinking.

Recent vintages, even of slow developers like Dom. de Chevalier, are brilliant young, but also age beautifully.

A couple of years in bottle is generally enough for even the top wines; more everyday bottles are best drunk within the year of the vintage.

SAUVIGNONASSE

It was only in the early 1990s that a distinction was made in Chilean vineyards between Sauvignon Blanc, which was what producers thought they had, and Sauvignonasse, which was what they actually did have much of the time. The two varieties look similar: it is an easy mistake to make. And since the original cuttings of ‘Sauvignon Blanc’ that populated Chile’s vineyards came from Bordeaux in the 19th century, the Chilean field mix merely reflected the 19th century Bordelais field mix.

Sauvignonasse is also known as Sauvignon Vert, but unlike Sauvignon Gris (also found in small amounts in Chile) it is not a mutation of the more pungent Sauvignon Blanc. Sauvignonasse did share the vineyards of Bordeaux with Sauvignon Blanc, but it lacks the assertive nose, the acidity and the staying power of the latter. Until it’s about three months old it can have quite good aroma and flavour, but it is an aroma of green apples rather than the blackcurrant leaf and gooseberries of Sauvignon Blanc. It has little character if picked underripe, and reaches high levels of alcohol – up to 14.5 per cent – very easily. Acidity, however, drops rapidly, and at more than 13 per cent alcohol the wine can taste dull and featureless.

It’s not clear just how much Sauvignonasse lingers in Chilean vineyards – the authorities recognize only Sauvignon Blanc, so that’s how it appears in the records – but it may be as little as 200ha (500 acres). New plantings in the north and on the coast are all Sauvignon Blanc.

Sauvignonasse used to be known as Tocai Friulano in Italy, where it was imported in the 19th century, but its official name now is simply Friulano to prevent confusion with Hungary’s Tokaji. It would be interesting to see if Chile could produce versions as impressive as those of the best growers of Collio and Colli Orientali del Friuli by dramatically lowering yields and taking their winemaking a little more seriously. See also Sauvignon Blanc here.

SAUVIGNON GRIS

An alternative name for Sauvignon Rosé, which is a pink-skinned version of Sauvignon Blanc (see here). It is much less aromatic than Sauvignon Blanc, but makes powerful, rather interesting wines. Chile has some, as does Bordeaux: Château Smith-Haut-Lafitte in Pessac-Léognan, for example, sometimes adds around 5 per cent Sauvignon Gris to its dry white which is otherwise entirely Sauvignon Blanc. Best producers: (France) Carsin, Courteillac, la Ragotière.

Savagnin vines growing on the limestone and marl soils of the Château Chalon appellation, in the Jura region of eastern France. The Vin Jaune from here is one of the very few flor-growing wines in the world. I’m not convinced that it’s as good as good sherry, but I’m beginning to understand its hidden charms.

SAUVIGNON VERT

An alternative name for Sauvignonasse and its official title in Chile.

SAVAGNIN

A very old variety that probably comes from northeast France (where its main stronghold is still the Jura) or southern Germany. There is a possibility that it is directly descended from wild vines; but on the other hand, Pinot might be one of its parents. The only thing that is certain is that Savagnin has an enormous number of mutations. Gewürztraminer, Traminer and Heida (Païen) are all, in fact, Savagnin, even though all are discussed separately in this book. And they are very different.

For Savagnin Rose and its aromatic form Gewürztraminer, see Gewürztraminer here. Here we’ll look at Savagnin Blanc, which seems to be its earliest form.

Savagnin is found in the Jura region, and is best known for the local speciality Vin Jaune, though it also makes straight table wines of startling structure, pungency and minerality. For Vin Jaune, the Savagnin ripens late, being picked at 13 to 15 per cent potential alcohol in November or even December. The flor-like yeast covering, here called voile or veil, grows more slowly and more thinly than the flor of Jerez (see Palomino Fino here), and dies earlier. There is no solera system used in the Jura; in Jerez and the other sherry towns it is the constant refreshing of wine in solera that keeps the flor alive. In addition, the much cooler temperatures of the Jura do not encourage such lavish growth. The wine is left in cask for six years and three months, by the end of which time it has developed a pungent, oxidized, nutty flavour with piercing acidity. Once bottled it is said to be able to last 50 years or more. I’m still keeping my one bottle.

Savagnin is grown throughout the Jura region, and while it is a permitted addition to any white wine there, it is usually kept for Vin Jaune. To recap, there is also a Savagnin Rose which is the same as Traminer (see here). The musqué form of Savagnin Rose is the more aromatic Gewürztraminer (see here). Australia makes good examples tasting of green apple core and lemony acid, although the growers thought they were planting Albariño. In Switzerland, as Heida or Païen it is full-bodied and fairly spicy. It‘s a speciality of the Valais, and is grown high up (1100m/3610ft high up) in Visperterminen. Best producers: (France) Arlay, Jean Bourdy, Hubert Clavelin, Jean-Marie Courbet, Durand-Perron, l’Étoile, Henri Maire, Montbourgeau.

SAVAGNIN NOIR

A name occasionally used in the Jura and parts of Switzerland for Pinot Noir (see here). It should not be confused with the local grape Savagnin (see left).

SAVATIANO

Greece’s workhorse grape, usually neutral and low in acidity, and used for inexpensive branded wines and for retsina. More acidic grapes, especially Assyrtiko and Roditis, are often added to retsina to give balance. The pine resin is added in pieces to the must, and removed only when the wine is racked. If grown on good sites and picked slightly earlier, Savatiano can produce surprisingly well-structured wines. Best producers: (Greece) Achaia-Clauss, Kourtakis, Semeli Winery, Skouras, Strofilia.

SCHEUREBE

Scheurebe was long thought to be a crossing of Riesling with Silvaner, aimed at finding an improved version of Riesling – or possibly a more perfumed version of Silvaner, depending on who you talked to. However, while one of its parents is certainly Riesling, the other is unknown.

Its wine lacks the taut elegance of good Riesling and even at its best tends to be clumsier, but it is complex and rich at high Prädikat levels, making powerful sweet wines with a fantastic flavour of ripe pink grapefruit swathed in honey which age quite well, though not for as long as equivalent Rieslings. It ripens to higher sugar levels, is high-yielding, and seems to produce its most exciting wines in the Pfalz. When made dry, there is a danger of catty, white grapefruit flavours if the grapes are underripe; Scheurebe like this can be raw and aggressive. It is, however, far and away the most successful of the modern German crossings, and the only one highly regarded by serious winemakers.

In Austria it is known as Sämling 88 (see here) – seedling number 88 was the seedling selected from all those propagated by Scheu in 1916. Best producers: (Germany) Andreas Laible, Lingenfelder, Müller-Catoir, Hans Wirsching, Wolff-Metternich; (Austria) Alois Kracher.

SCHIAVA

This Italian red grape (or grapes, since the name covers several more or less similar but genetically different vines) produces perfectly pleasant everyday wines in Trentino-Alto Adige, but doesn’t seem capable of anything of real excitement. It yields generously, and gives wines of light smoky strawberry fruit and a mildly creamy texture. Concentration, depth and complexity, however, are generally lacking. It is declining as growers see the greater commercial opportunities of weightier reds, but still covers a substantial area.

Its Italian name means ‘little slave’ – the variety is very amenable, though its Süd-Tirol German name, Vernatsch, means ‘of local origin’, suggesting that it has long been thought of there as being a local variety. The name it is given in Germany itself, Trollinger, also suggests a link with the Tyrol. Records of the vine in Trentino-Alto Adige go back to the 13th century. (See Vernatsch here and Trollinger here.) The range of Schiavas includes Schiava Grigia, or Grauvernatsch; Schiava Gentile, or Edelvernatsch; and Schiava Grossa, or Grossvernatsch; and Schiava Lombarda. Schiava Grossa is the least distinguished, but particularly high yielding, so inevitably it is the most planted.

It is the main grape in DOC Santa Maddalena, where it may be given more character by Lagrein or some other red grape and I have to say I’ve had some really lovely gentle, fresh picnic wines sitting among the vines high above the city of Bolzano. It is also found in numerous other DOC and non-DOC wines in the area. Declining Schiava may be, but in the high mountains of Alto Adige in early summer, well, find me a more delightful red than one of these. Best producers: (Italy) Cornaiano co-op, Cortaccia co-op, Franz Gojer, Gries co-op, Lageder, Josephus Mayr, Thomas Mayr, Niedermayr, Georg Ramoser, Hans Rottensteiner, Heinrich Rottensteiner, San Michele Appiano co-op, Santa Maddalena co-op, Termeno co-op.

SCHIOPPETTINO

A fairly characterful northeastern Italian variety recently rescued from terminal decline. It is native to Friuli, and is also known there as Ribolla Nera. Its flavour is peppery and raspberryish, fairly light in body and alcohol, and with high acidity. There is also a local young and fizzy version. Best producers: (Italy) Dorigo, Davide Moschioni, Petrussa, Ronchi di Cialla, Ronco del Gnemiz, La Viarte.

SCHÖNBURGER

A German crossing (Pinot Noir with a crossing of Chasselas Rose and Muscat Hamburg) now more grown in England than in Germany, where it is concentrated in the Rheinhessen and Pfalz. It ripens easily, yields well and is disease-resistant. Its berries are pink but it is used for making white wine. Its perfume is heavy and somewhat Muscatty which is very attractive in a light English wine grown in England’s cool climate, but can be rather cloying in wine from warmer climes. Best producers: (Canada) Gehringer; (England) Carr Taylor, Danebury.

SCHWARZRIESLING

The German name for Pinot Meunier (see here); it is found mostly in the Württemberg. region. Best producers: (Germany) Dautel, Drautz-Able, Fürst zu Hohenlohe-Öhringen, von Neipperg.

SCIACARELLO

A grape once thought to be unique to Corsica but now revealed as the Tuscan Mammolo. However, since it’s probably been growing in Corsica since the 11th century, you can see why the Corsicans claimed it as their own. It is at its best in the southwest of the island, around Sartène and Ajaccio, and while its wines are light in colour and not particularly tannic, they have a lively herby pepperiness. With age they develop hints of woodsmoke and tobacco. The name means ‘the grape that bursts under the teeth’ and – guess what – the grapes have tough skins and lots of juice. Best producers: (France) Albertini Frères, Clos Capitoro, Clos Laudry, Martini, Peraldi, Torraccia.

SCUPPERNONG

A vine found in the southwestern states of the USA and in Mexico, Scuppernong is a Vitis rotundifolia vine, and belongs to the genus Muscadinia. The thick-skinned berries grow in small clusters and are low in sugar; chaptalization is normal. Pressing can be difficult, too, because of the thick, fleshy pulp. The flavour is strong and musky and the wines are usually made sweet.

Virginia Dare, a North Carolina wine that enjoyed great popularity in the early years of the 20th century, was made from Scuppernong and named after the first child born in the American colonies to English settlers. It seems bizarre now, with the dominance of California as a USA grape grower, but, largely due to Scuppernong, North Carolina was, for a time in the 19th century, the USA’s most prolific grape grower, and Scuppernong is still the official state fruit.

SEIBEL

A group of French hybrids produced by Albert Seibel (1844–1936). Seibel 4643, also known by the somewhat ambitious name of Roi des Noirs, used to be widely planted in western France, though is so no longer: its wine was rustic and dark. Other Seibels include 7053, otherwise known as Chancellor; and 5279, or Aurore, both early ripeners planted here and there in North America.

SÉMILLON

Sémillon: from Grape to Glass

Geography and History here; Viticulture and Vinification here; Sémillon around the World here; Enjoying Sémillon here

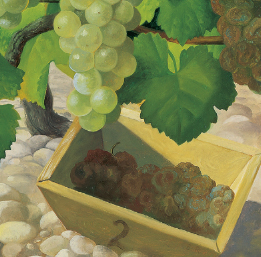

Seen here in the honeyed autumnal light evocative of its precious golden wine, Château d’Yquem is the supreme example of the majestic sweet wines of Sauternes. Pickers will go through the vineyards up to a dozen times during the harvest, picking only the most ‘nobly rotted’ grapes in a constant attempt to make the best sweet wine in the world.

You can’t say that Sémillon hasn’t been given a chance. Half the wine countries in the world have given it a chance, and almost as many have decided that it can’t seem to produce anything remotely interesting, so let’s rip most of it out again. That happened in South Africa – where it was very popular largely because Semillon rewarded the very favourable, benign vineyard conditions there with oceans of dull, tasteless juice that just happened to be fine for distilling into brandy if little else. Luckily brandy was what most South Africans drank at the time. Chile was overrun with it for much of the 20th century. Argentina and the rest of South America also gave it its head, and Sémillon thanked them by making wines that were a byword for dullness and which revelled in attracting sulphur like carrion attracts crows.

And, of course, there’s Bordeaux in southwest France. Bordeaux has the biggest plantings in the world, but even these are a fraction of what they used to be. Barely 50 years ago, half of Bordeaux’s production was white, mostly from the Sémillon grape. Now Bordeaux has 121,270ha (299,665 acres) of vines. Only 7021ha (17,350 acres) of these are Sémillon, and the most important of these are to the southeast of the city of Bordeaux, in Graves, Pessac–Léognan and Sauternes. And it’s here that Sémillon can excel, though not without help. In the first case, human intervention has discovered that if you ferment Sémillon in barrels it takes on a wonderful waxy, creamy quality. Blend it with Sauvignon, which adds crispness, leafiness, citrous tang, and you have memorable dry white wine, as good as white Burgundy. A few people round the world have succeeded with this formula, mostly in South Africa and Western Australia.

But it’s greatest triumph is due to nature’s helping hand. In the Sauternes region, nature creates perfect conditions for the grapes to rot in the vineyard. Now, rot is the curse of the red wine grower. Yet rot is the making of the crop in Sauternes. But not any old rot. Noble rot, so called because it concentrates the sugar in the grapes without turning the juice sour and undrinkable, needs very special conditions to flourish, and in Sauternes’ little patch of land it gets them. The local rivers Ciron and Garonne get very foggy in the autumn mornings. If that fog is compounded by rain, we’re in trouble. All kinds of rot will threaten, none of them noble. But if the sun fills the sky and burns off the morning fog, the whole vineyard becomes muggy and humid – and hot. And in these conditions noble rot sets to work thinning the skins of the Sémillon grape and intensifying the sugar to such an extent that memorable sweet wine is created.

There’s one other place where terrible weather has conspired to make great Semillon wine – Australia’s Hunter Valley, north of Sydney. Nature knows that no sane person would try to grow grapes there, and ever since the first magnificent obsessives decided to have a go in the 1830s nature has done her best to flout their efforts. She’s washed away the decent soils with a never-ending succession of tropical storms. She’s arranged subtropical heat during the summer, brackish bore water unfit for irrigation, and frequent winter droughts, just in case you were thinking you might build a few dams to store water to help your vines survive. And to make quite sure you got the message that grape-growing is doomed in the Hunter, she arranges cyclones to sweep down the coast and batter the valley just before the hapless grapes are ripe – just so you know who’s really in charge. And without me attempting to seek refuge in rhyme or reason, it is precisely these woeful conditions that have created the classic Hunter Valley Semillon.

In the occasional perfect summer, with the grapes fully ripe and the harvest safely in, Hunter Semillon is full and fat, a bit blowzy – good grog, but quick to flower and fade. But in the years when nature does her worst, when the grape’s alcohol level sometimes barely reaches 10 per cent alcohol, the result – if you wait 10 years for it to mature – is one of the world’s great classic whites. Unsurprisingly, completely unlike any other white wine in the world.

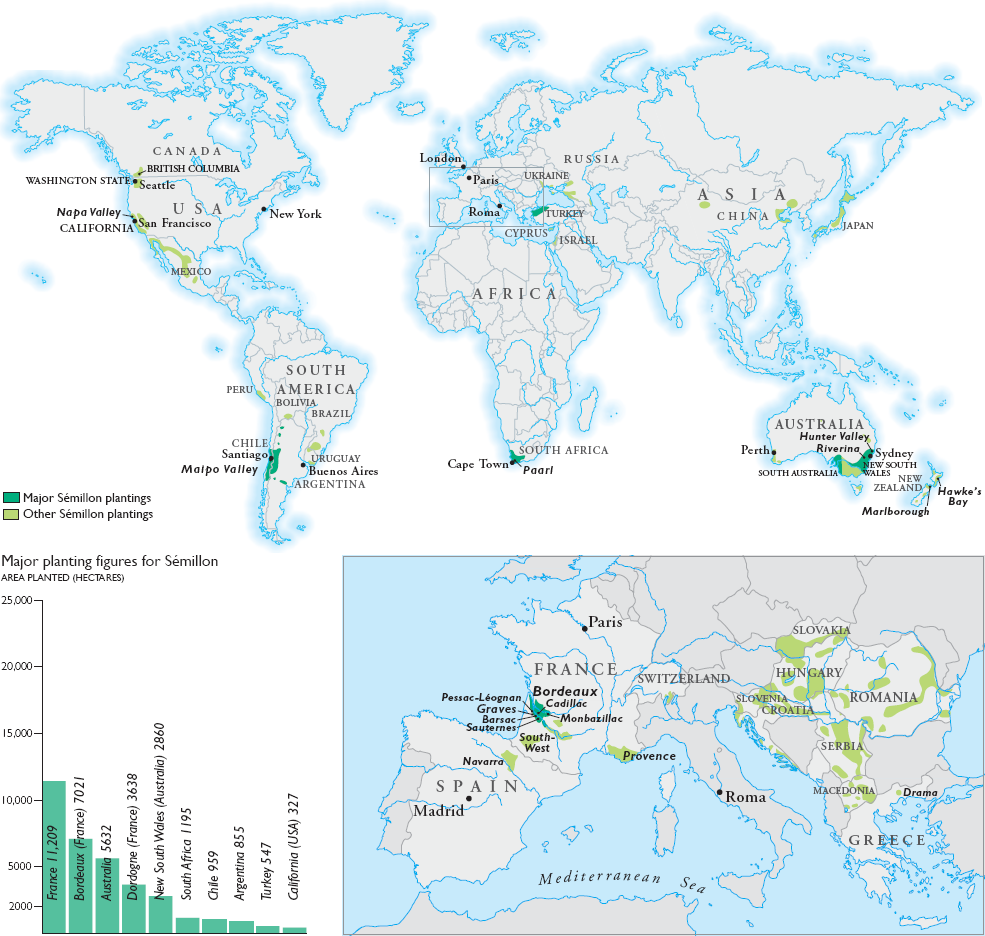

GEOGRAPHY AND HISTORY

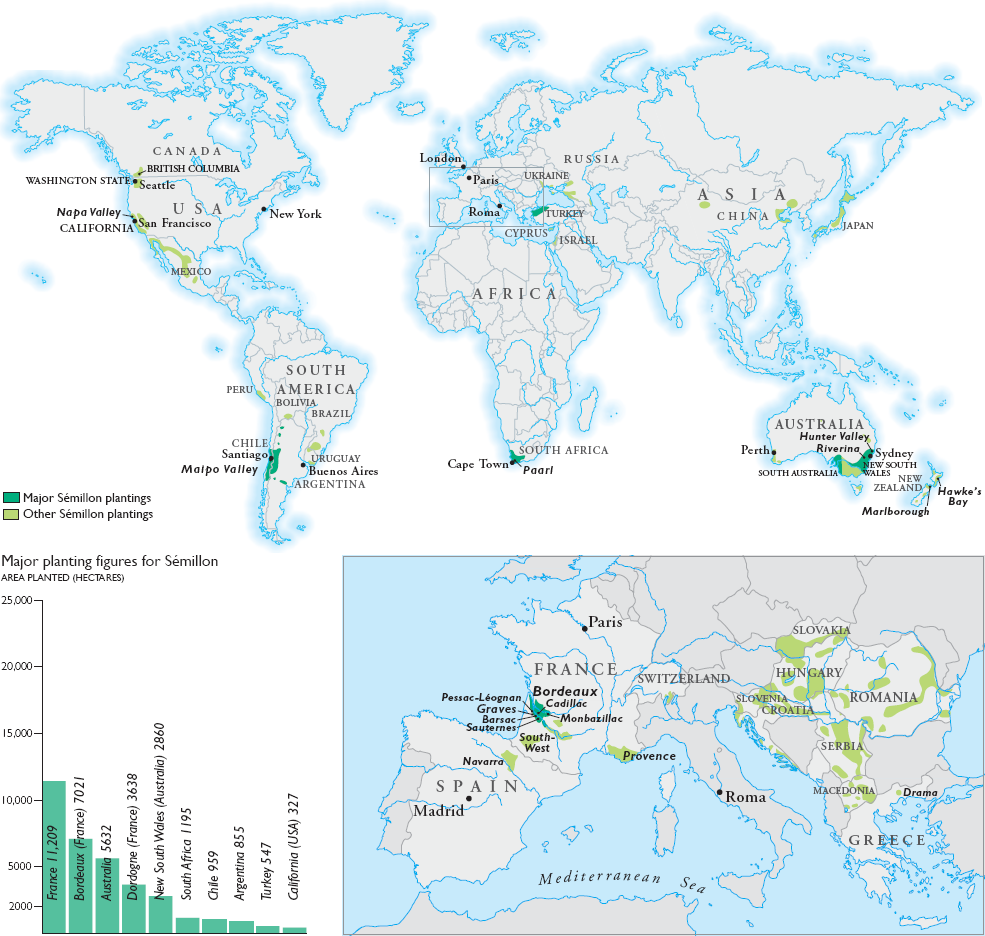

Where has all the Sémillon gone? Look at the map and it’s just isolated patches: southwest France has the most, and there’s some in Australia, some in Chile and other South American countries, and a bit in South Africa.

Yet 50 years ago some three-quarters of Chile’s white vines were Semillon (it’s usually seen without the accent in New World winemaking countries). It smothered South Africa – in 1822 it covered 93 per cent of the vineyard area, and was referred to with perfect logic simply as Wyndruif, or wine grape.

Chile now has much less. South Africa has much, much less. First of all, Sémillon gave way to Chardonnay; now white grapes are in their turn giving way to red. And Sémillon, planted all over the world for its disease resistance and its ability to produce large quantities of grapes, might have had its day, were it not for two facts. One is that it produces outstanding sweet wine in Sauternes and Barsac on the left bank of the Garonne in Bordeaux. The other is that it produces outstanding dry wine in Australia’s Hunter Valley north of Sydney, and blended with Sauvignon, in Western Australia’s Margaret River, a few spots in South Africa, and, above all, in Pessac-Léognan and Graves, next door to Sauternes. And that’s just enough of a CV to keep Sémillon being planted around the world.

The thing is, Sémillon was planted as an all-purpose grape – you could make dry or sweet wine from it, sherry, brandy, whatever. Yet it isn’t an all-purpose grape. At high yields it is dilute and thin; when underripe it is green and stringy. Even its sweet wines usually need a touch of Sauvignon Blanc to brighten them up. And then, in misty, humid Sauternes and the subtropical Hunter Valley where the conditions are hardly suitable for grape growing at all, it produces world-class wine. So why does it make so few great wines in much easier conditions? Let’s have a look.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The ampelographer Galet thinks that Sémillon probably originated in Sauternes and spread from there to the rest of the Gironde. It was found in St-Émilion by the 18th century, and indeed St-Émilion used to be one of its local synonyms; nowadays this is a synonym for the Ugni Blanc variety, which Sémillon does not remotely resemble. It was still planted in St-Émilion on a small scale, along with Sauvignon Blanc and Muscadelle, for white wines well into the 20th century, and even now there are a few fugitive vines there.

When was Sauternes first made sweet? The usual date given, for want of concrete evidence of an earlier date, is the mid-19th century. To suppose that it was not made sweet before, however, requires a suspension of disbelief: Tokaj had been famous for its botrytis-affected sweet wines since the late 17th century, so the technique of making sweet wines from botrytized grapes was well known; and Botrytis cinerea occurred in Sauternes and Barsac then just as it does now. Picking in the region in the 18th century was not until late November; in Cadillac – on the right bank of the Garonne – the Abbé Bellet, who kept records of every vintage from 1717 to 1736, confirms that by October the grapes were affected by noble rot, and were picked in selective tries. He does not confirm that only the rotten ones were used, but if the non-rotten ones had been the most desired, and had been picked in the first trie, it is hard to see the point of further pickings. Clearly the selective trips through the rows of vines were to pick out the grapes affected by noble rot. And he would have found it pretty hard to make ordinary dry wine from such grapes.

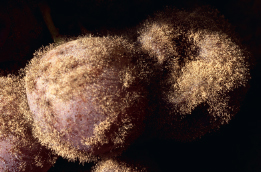

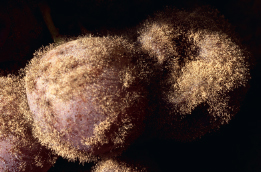

If you judged a grape solely on its appearance, it’s hard to see why anyone would make wine from ugly, squishy, noble-rotted grapes. But squeeze the gooey syrup from the grapes and lick your fingers and the fabulous rich flavour will persuade you in a flash.

A golden autumn day at Château Suduiraut at Preignac in the Sauternes appellation. This is just the sort of weather that favours the development of noble rot: humid, foggy nights are essential, but if dampness persists throughout the day, the rot will turn grey and ignoble and there will be little chance of rich, sweet wine.

A carved coat of arms at Château d’Yquem, Sauternes. The Sauvage family owned d’Yquem until 1785, when the Lur-Saluces family acquired it. They held it until 1999, when it was bought by LVMH.

A gooey mess of nobly rotten Sémillon grapes. Grapes in this state may look hideous but they are highly desirable for their super-concentrated sugars. They are difficult to press and slow to ferment.

VITICULTURE AND VINIFICATION

I can see why Sémillon was such a popular variety in the old days. It will grow just about anywhere and will recklessly produce gigantic crops of grapes. Which taste of...? Er, nothing really. Just vatsful of juice of no discernible personality but enough sugar to ferment into whatever kind of concoction you fancy. From dry white to sweet, from sherry to brandy. But in one or two little corners of the globe, if you really restrict its crop and vinify it skilfully, it has for centuries produced world-class dry and sweet whites. It buds slightly later than Sauvignon Blanc but ripens earlier, and is actually less subject to noble rot than Sauvignon. It is resistant to most other diseases, but rainy years can produce attacks of grey rot. This is caused by the same fungus as noble rot, but has different, more harmful results – most importantly it tastes horrible.

Climate

It is an unarguable fact that if you were to match your vine varieties with your sites on a rigid degree-day basis you would never plant Semillon in the Hunter Valley. It is, by this reckoning, far too warm there to produce dry Semillon, and indeed far too humid, especially when the humidity takes the form of tropical downpours at harvest time. But Semillon thrives there, and even more curiously, it is rainy years that often produce the best Hunter Semillon, years which are so poor in accepted terms that the alcohol level hardly reaches 10 per cent. There’s got to be a reason. Up to a point, there is. So here’s the science. It still won’t all add up, because Hunter Semillon is one of the wine world’s great enigmas. But here goes.

That the region produces such good Semillon is partly due to its cloud cover: the temperature may rise to 42°C (108°F) during the day, but the sunlight is muted. The Hunter has a relatively low ratio of hours of bright sunshine to effective day degrees, and this helps to keep sugar levels down. (It also helps to mitigate tannins and astringency in the red wines of the region.) The humidity also helps: high afternoon relative humidity is associated with higher acidity levels in grapes, and low-acidity Semillon needs all the help it can get in this department.

The climate in the Hunter Valley could hardly be less like that of Bordeaux, except that autumn humidity here is essential for the growth of Botrytis cinerea in Sauternes. Early morning mists, caused by the confluence of the ice-cold river Ciron and the warmer Garonne, spread back up the Ciron valley and encourage the growth of botrytis in the neighbouring Sauternes vineyards. The botrytis has the effect of concentrating both sugar and acidity, again giving the grape’s low acidity levels a helping hand.

Interestingly, Bordeaux’s relative humidity and sunshine hours compare with those of the Upper Hunter, though of course the latter is much, much hotter. The Lower Hunter, however, has less relative humidity than Bordeaux, and slightly fewer sunshine hours.

Soil

In the Hunter Valley the usual soils for growing vines are light, sandy ones, simply because heavy soils become quagmires after heavy rain. In a way, suitable doesn’t come into it in the Hunter. There are some soils that will support vines – whatever variety – and there are poor clays that won’t support anything at all. Period. The best-drained soils in the Lower Hunter Valley include the friable loam and friable red soils. In the Upper Hunter black silty loams over dark clay loam are successful; the red-brown duplex soils, which resemble those of the Lower Hunter, are better drained, which is not automatically an advantage in this hotter, drier region where irrigation is essential.

The soil in Sauternes is sandy gravel in varying depths over calcareous clay; Barsac is much flatter, and lacks the gravel of Sauternes. Barsac has well-drained, sandy, limy soil, and vine stress can be a problem in very dry years. In Sauternes, by contrast, the clay subsoil can be poorly drained where the topsoil is very thin: Château d’Yquem put in some 10km (6 miles) of drainage in the 19th century to correct this. Because Sémillon ripens earlier than Sauvignon Blanc, it may be planted on more clayey soil in Sauternes; it is sometimes suggested that clay can favour the development of botrytis. Sauvignon Blanc may be planted on the gravel. In the Graves, however, where a different style of wine is desirable, Sémillon gets the warmer soils and the better-exposed sites. The AC rules state that the vines must be eight years old for Sauternes; some châteaux maintain that they don’t get good levels of botrytis until they are 10. Root depth seems to be a factor in determining whether rot turns noble or grey; shallow-rooted vines tend to get grey rot.

Picking grapes is never easy work – it’s backbreaking at the best of times. But when you have to search each cluster for berries of the right degree of noble rot, as is happening here at Château d’Yquem in Sauternes, then it requires great concentration. Only skilled pickers can be trusted with such a task.

Cultivation and yields

In Bordeaux growers may leave a long cane in order to have some spare buds in case of spring frost; what may happen is that the buds at the end of the cane grow vigorously and impede the development of those further down. The cane may be trained in an arcure to balance this.

Yields must be low if quality is the aim. Sauternes is the lowest: the legal limit is 25hl/ha, and most leading properties make much less. Yquem famously makes just one glass of wine per vine, or 9hl/ha. In Monbazillac legal maximum yields have been cut from an overgenerous 40hl/ha to a sensible 27hl/ha. In the lesser regions of Bordeaux yields may reach 80–100hl/ha. Australian yields are around 3.5 tons per acre or 8 to 9 tonnes per hectare (roughly 60hl/ha); in New Zealand Semillon produces thinner, grassier wine at 10–17 tonnes/ha.

At the winery

The big question with Sémillon is to oak or not to oak? It certainly has a great affinity with oak, in particular with new oak, and the increased proportion of new oak used by the Sauternes châteaux since the mid-1980s has been a factor in the improvement of the region’s wines. In the Graves, too, it is commonly fermented and aged in new oak; in youth these blends of Sémillon and Sauvignon Blanc can seem too intensely oaky but they age remarkably well. New oak here is being used with a more delicate hand than it was a few years ago, as is sulphur in Sauternes: Sémillon oxidizes easily, and one of the effects of noble rot is to make it require extra sulphur to protect it against oxidation. It takes a strong nerve for a grower to hold back. A few Sauternes are still noticeably sulphurous in youth, though this should fade with age.

They look terrible, don’t they – awful, soggy, covered with furry rot. But this is noble rot at work, and the worse the grapes look, the sweeter their juice will be and the more luscious the wine.

The alternative style in Bordeaux and the southwest is the stainless steel-fermented one of crisp fruit and youthful acidity. Such wines are not intended to age, and a large proportion of Sauvignon Blanc is essential if the wine is to have sufficient flavour; young, unoaked Sémillon can taste lemony and grassy, but that’s about all. If it doesn’t have Sauvignon to help it along, then it needs oak. Sometimes, as in the great Sémillon-based dry whites of the Graves and Pessac-Léognan, it gets both.

In Australia, unoaked Semillon is a classic style of the Hunter Valley north of Sydney, where unpredictable, subtropical conditions often mean the grapes have to be picked very early or they rot on the vine. These wines, neutral – indeed positively acidic and tart – in youth, mature (after a decade or so) into rich, honeyed toastiness – tasting for all the world as though they had spent their infancy in new oak barrels, although they haven’t. Australian wine buffs love to bemuse visiting Brits in blind tastings with these unoaked beauties that we unerringly pronounce to be mature French Burgundy. The Hunter has toyed with oak-aging and now mostly rejected it; in South Australia, too, producers have mostly pulled back on the oak, though some is still successfully used in Western Australia. For the consumer, and perhaps for the producer, oak-aging means that the wine has more complexity at a young age: unoaked Hunter ones are beloved by those who know them, but they are about as far removed from wines for instant gratification as it is possible for a white wine to get. It’s not a difficult wine to make. As Bruce Tyrrell says, ‘just chuck it in a tank and leave it’.

SÉMILLON AND BOTRYTIS

What makes Sémillon and Botrytis cinerea so suited to each other? And what makes some rot noble and delicious and other rot merely grey and unpleasant-tasting?

Noble rot and grey bunch rot are the same fungus: both are Botrytis cinerea. The fungus is now thought to infect the berry at fruit set, and can develop in either direction, depending on circumstances; and it is by no means unknown to have grey rot and noble rot together, even on the same cluster.