3 Rothicity in Malaysian English:The emergence of a new norm?

1 Introduction

Malaysian English (MalE) is classified as a New English together with other postcolonial varieties of English such as Indian and Singapore English. These varieties developed from the time English was brought over by, in most cases, the British. Their historical link with Britain (and in some cases America) set these varieties apart from English as a foreign language (EFL) contexts. In many of the postcolonial settings, both the educated and local forms of English are still used for intra-national communication by a certain percentage of the population, and the presence of English in education, business, local media and creative works may still be strong in these contexts. However, different language settings and language policies following the withdrawal of Britain from their colonies have affected the extent to which English is used and learnt in these postcolonial countries. For example, in many postcolonial contexts, English may be considered as a second language (ESL) with reference to it being learnt or used as a second language after one or more indigenous languages or a national language. Different language settings and language policies have also resulted in postcolonial varieties of English developing distinctive linguistic features.

In Malaysia, English is considered to be a second language (L2) but this is only true in the sense that it is the second compulsory language taught in Malay medium schools. The use of the term L2 does not mean that English is the second language learnt by the majority of Malaysians. Neither does it imply that it is the second most used language in Malaysia. The dominance of English in Malaysia is context-driven and restricted to particular domains, and for many multilingual Malaysians, it may be the third or other language which is learnt in school with varying degrees of success.

Only approximately two per cent of Malaysians speak English as a first language (L1) (Crystal 1997: 58). This is one of the features of postcolonial settings where there is likely to be speakers, albeit a minority, who claim English as a first language. These L1 speakers of English grow up speaking English at home and will tend to use it as a dominant language for communication even if they

Stefanie Pillai, University di Malaya, Kuala Lumpur

subsequently learn other languages like Malay or Mandarin. For example, in a study on the use of English among Malaysian undergraduates, those who claimed to be L1 speakers of English said that they always used English at home (Pillai 2008a), and similar to another group of L1 speakers interviewed in Pillai and Khan (2011), also said that they tend to use mainly English when communicating with relatives and friends. The undergraduate English L1 speakers were in their early twenties and were of Chinese and Indian origin, while the ones in Pillai and Khan (2011) were of Portuguese Eurasian descent and were aged between 39 to 68 years old. Despite their different ethnic backgrounds, they all considered English rather than their heritage languages to be their first language based on the fact that they first learnt to speak English at home. There are also some Malaysians who grow up speaking English and one or more languages at home. This distinguishes the English-as-an-L1-speakers from the majority of Malaysians who do not learn or speak English at home. They instead learn it either from the time they enter pre-school (from 4 to 5 years old) or primary school (from 7 years old). As mentioned earlier, English may not necessarily be the second language this group learns or speaks, and some of them may become highly proficient in English and use English as much as or more than other languages because of their social, educational background and profession. Thus, to refer to this entire group as L2 speakers may not provide an accurate picture of their actual proficiency and/or use of English.

Instead, in multilingual settings such as Malaysia, labels such as English as an L1, L2 or ESL are not always useful due to the diversity in how and when and to what extent English is learnt and used. The Portuguese Eurasian group in Pillai and Khan (2011) all said that they used mainly English at the workplace, while the undergraduates who were studying at a public university tended to use both English and Malay depending on to whom they were speaking, and what they were doing. The use of English among the two groups of speakers mirrors the current situation in Malaysia, where the public sector generally functions in Malay, while the private sector, which is focused in cities like Kuala Lumpur and Penang, still largely operates in English. Thus, as reported in McArthur (2002: 335), about “25% of city dwellers use it [English] for some purposes in everyday life. It is widely used in the media and as a reading language in higher education and for professional purposes”. The importance that is placed on English in the professional setting can be seen in the numerous complaints by employers about the poor command of English among Malaysian graduates (Downe et al. 2012; Survey by Manpower Inc. 2008 cited in The National Graduate Employability Blueprint 2012–2017 2012).

Further, language use and fluency in English and other languages function in a multidimensional manner taking into account a host of factors. As Canagarajah and Wurr (2011: 3) point out, “[m]ultilinguals adopt different codes for different contexts and objectives. From this perspective, the objective of their acquisition is repertoire building rather than total competence in individual languages”. Within this repertoire may also be a different ‘types’ of English such as colloquial and Standard English which users can weave in and out of depending on the context in which English is being used (Govindan and Pillai 2009). For example, the variety of English used at home is likely to be the colloquial variety of Malaysian English (Pillai 2008a). Thus, even for those for whom English is a first or dominant language, the variety of MalE that is used, especially the spoken variety, displays distinct linguistic features compared to other varieties of English (e.g. Pillai 2012). In terms of pronunciation, for example, there is a noticeable lack of contrast between vowel pairs such as /ɪ/ – /iː/, /e/ –/æ/, and /ʌ/ – /ɑː/ (Pillai et al. 2010). Such features of pronunciation are likely to have been ‘learnt’ at home or in schools from Malaysian teachers, and then are used when communicating in English with fellow Malaysians. Over time, they could become an accepted “tacit endonormative standard” (Gut 2007: 355). This is perhaps one of the distinguishing features between some postcolonial varieties and EFL contexts. Thus, whilst it has been suggested that language background affects English pronunciation, in situations like in Malaysia, where English is generally learnt from fellow Malaysians, the language background of speakers may not be the only mitigating factor as there are particular pronunciation features which are common across Malaysians, making it possible to distinguish, for example, between a Malaysian and Hong Kong or Mainland Chinese English speaker. Further, unlike typical L2 contexts in which English is learnt in a non-English context, English is used in Malaysia with a colloquial variety thriving alongside a more acrolectal one.

While EFL contexts generally lean towards a native model of English, usually either British or American English, some postcolonial countries may have shifted to their own model of English as a norm. Gut (2007: 356) explains this as a shift to an “endonormative orientation” in her Norm Orientation Hypothesis, where distinct linguistic features systematically emerge over generations as speakers begin looking towards their own variety of English as a norm. One such example is Singapore (Gut 2007: 356), which incidentally is also placed in the fourth phase, “endonormative stabilization”, of Schneider’s Dynamic Five-Phase Model of the Evolution of New Englishes (2003: 243).

In Malaysia, however, whilst some features of pronunciation seem to be more systemically established than others (e.g. the lack of vowel contrast), others, such as rhoticity, do not appear to be so. A variety of English is considered rhotic when the <r> in the spelling of the word is pronounced in the syllable coda either as the only consonant (e.g. paper#) or before another consonant (e.g. card) (Trudgill and Hannah 2008: 20). This <r> in the spelling of English words that occurs in the syllable coda position is often called post-vocalic /r/. However, the term “non-prevocalic /r/” (e.g. Trudgill and Hannah 2008: 11) is perhaps more apt for this feature of rhoticity compared to “post-vocalic /r/”. The latter could include instances in non-rhotic varieties where the <r> in the spelling is pronounced before a vowel, such as in intervocalic positions in a word (e.g. carry) and across word boundaries (e.g. four eggs). In contrast, the term “non-prevocalic /r/” applies to the pronunciation of orthographic <r> in word final positions preceding a pause and preceding a consonant (Salbrina and Deterding 2010). Since there is inconsistency in the terms used in the literature, the original terms used by the authors will be maintained when discussing their work, but the term coda /r/ is used when discussing the findings in the present study.

2 Previous studies

2.1 Rhoticity in Malaysian English

Although MalE, having its roots in British English, is considered a non-rhotic variety (e.g. Baskaran 2004), the pronunciation of coda /r/ has been reported in this variety. For example, Ramasamy (2005) found instances of rhoticity among younger Malaysian Indian speakers. She examined the production of this feature among middle-class Malaysian Indians who were all of Tamil origin, and based on auditory examination, she found no evidence of such realisation among her older speakers (47–54 years old). However, she found that the younger speakers, particularly the 14 to 17 year olds tended to pronounce the <r> in coda position. Based on her findings, she suggests that rhoticity is an emerging phenomenon in the speech of young Malaysian Tamils. Pillai (2014) also found sporadic realisations of rhoticity among Malaysian speakers who were in their twenties. Ramasamy (2005) suggests that rhoticity among her younger speakers is due to the influence of American media. The influence of American media on young MalE speakers has also been suggested by Rajadurai (2006), although thus far, no other instances of the consistent use of other forms of American English pronunciation, such as flapping or the use of unrounded /ɒ/ have been reported.

Phoon, Abdullah and Maclagan (2013), however, did not find any instance of coda /r/ being realised by Indian speakers in their study. This could be attributed to the fact that none of the speakers in their study, who were aged between 19 to 22 years old, used English as a first or dominant language. This differs from the younger (14–17 years old) speakers in Ramasamy’s (2005) study who had all acquired English at home and used it as a dominant language. Further, none of the speakers in Ramasamy’s study were from Tamil medium primary schools whilst the ones in the study by Phoon, Abdullah and Maclagan (2013) were. This suggests that the Indian speakers in Phoon, Abdullah and Maclagan’s (2013) study were predominantly second language speakers of English compared to the ones in Ramasamy’s (2005) study who used English as their first language. None of the latter spoke their heritage language, Tamil, fluently. The use of English as a first or dominant home language is not an uncommon phenomenon among middle class and above Indian families (e.g. David, Naji and Kaur 2003; Schiffman 1995), and it may be that rhoticity is more evident in this group of speakers. This could be due to more exposure to American media and the influence of peers.

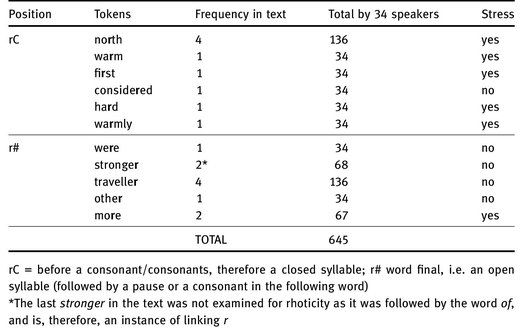

All 15 speakers in Phoon, Abdullah and Maclagan’s (2013) study were in fact second language speakers of English, with the Chinese and Indian speakers having attended vernacular primary schools where the medium of instruction is Mandarin or Tamil. It has to be stated here that the term ‘second’ is with reference to English not being the first language of the speakers, and does not necessarily reflect the order of use or learning as the speakers are all multilingual, with at least one other language, Bahasa Malaysia or Malay, in their language repertoire. The speakers’ overall self-rating for speaking in English was between weak to average based on the mean of 2.8 (SD = 0.6) on a scale from 1 to 5 (1 = very weak and 5 = very good) (Phoon, Abdullah and Maclagan 2013: 12). This again contrasts with the ones in Ramasamy’s (2005) study who were all reported to be fluent speakers of English. Perhaps this might explain why Phoon, Abdullah and Maclagan (2013) did not find any evidence of rhoticity among their Indian speakers. They did, however, find instances of the coda /r/ being produced by their Chinese speakers, but only in 7% of the selected tokens. Yet, in an earlier study of ten Chinese Malaysians aged between 19 to 26 years old, all of whom were recruited based on the criteria that they were exposed to English since birth and used it as a dominant home language, Phoon and Maclagan (2009: 32) found that although there was evidence of rhoticity among all but one of their speakers none of them were “consistently rhotic” with less than 25% of coda /r/s in 990 words being realised. Phoon and Maclagan (2009: 32) did, however, report that the speakers were more inclined to realise the coda <r> preceding a consonant (e.g. bird) compared when it was in word final position (e.g. hair). This inconsistency in realisations of coda /r/ in these word positions is reflected in the different studies that have mentioned rhoticity in MalE. Table 1 summarises these findings from some of the studies that were discussed in this section of the paper.

Table 1: Table 1 Rhoticity in Malaysian English

None of the studies on rhoticity in MalE thus far indicate that there is a consistent display of rhoticity in MalE. This contradicts Kirkpatrick (2007: 123), who states that one of the differences between Malaysian and Singapore English is that “Singaporean English is non-rhotic, but Malaysian speakers produce the post-vocalic /r/ in certain contexts”. He does not, however, elaborate on what these contexts are. This clearly does not apply to all Malaysians in general as we are talking about a large number of speakers of different ages with varying levels of fluency in English, who come from different language backgrounds and social backgrounds, and who live and work in different parts of Malaysia.

Although the results on this phenomenon remain largely inconclusive with a general perception that MalE is becoming more “American”, largely due to auditory impressions of rhoticity, it appears that age and language backgrounds may be related to the presence of rhoticity among Malaysian speakers. There have been no attempts to examine the emergence of rhoticity as a possible development of a new pronunciation norm, signalling a move away from an endonormative norm, British English. This is perhaps one of the key differences between postcolonial and EFL contexts. Speakers in the former, having had a longer encounter with English and a longer period over which particular linguistic features including pronunciation features have developed, could have entered a phase where these features may become established norms in the variety, and hence have a endonormative orientation. Speakers in the latter context (e.g. China, Indonesia and Korea) tend to have an exonormative orientation.

The study reported in this chapter examines the use of rhoticity among two age groups (20–29 and 30–45 years) from three main ethnic groups (Malay, Indian and Chinese) in order to answer the following research questions: (1) To what extent do Malaysian speakers pronounce coda /r/ both before a consonant and in word-final position (2) To what extent is there a relationship between rhoticity and speakers for whom English is an L1, and those for whom it is not? (3) Is there more evidence of rhoticity among younger speakers? The assumption underlying these questions is that there will be more evidence of rhoticity among the younger group, in particular among the MalE L1 group, who predominantly use English . We can expect linguistic innovations like new pronunciation features to be seen in this group rather than among those for whom English is not a first or dominant language. The findings will also be discussed with reference to rhoticity in neighbouring varieties of English who share the same British English legacy, namely, Singapore and Brunei English. This will be done in order to establish if similar trends are emerging among these neighbouring varieties, and if this is related to whether the patterns of use are related to the acceptance of an indigenous or external variety of English as a norm among these postcolonial varieties of English.

2.2 Rhoticity in neighbouring varieties of English

A study on rhoticity in Singapore English by Tan (2012) found that the level of education and socio-economic status of Singapore speakers influences the use of coda /r/ (Tan 2012 used the term postvocalic /r/) and intrusive /r/, the realisation of /r/ at the end of a word which ends with a vowel, e.g. law when it is followed by a word beginning with a vowel e.g. law and order. Her speakers were Chinese Singaporeans who were English-Mandarin bilinguals. Those with a higher level of education and socio-economic status showed a higher tendency to produce post-vocalic /r/. On the other hand, those with a lower level of education tended to produce the highest percentage of intrusive /r/ compared to those with a higher level of education. Tan (2012: 19) reports that “there is a direct correlation between education level and socioeconomic status of the speaker and the production of postvocalic-r and intrusive-r in SgE. Speakers of higher education levels and socioeconomic status have a tendency to produce postvocalic-r, and speakers of low education levels and socioeconomic status have a tendency to produce the intrusive-r”. This is similar to Tan and Gupta’s (1992) finding that the production of coda /r/ is a prestige feature for some speakers of Singaporean English. Poedjosoedarmo (2000) also found evidence of rhoticity among educated Singapore English speakers, particularly among Chinese speakers. All these findings on Singapore English contradict Kirkpatrick’s (2007: 123) claim that “Singaporean English is non-rhotic”.

Still, at this point in time, rhoticity cannot be considered a definitive feature of Singapore English as it does not cut across ethnic or social groups. For instance, Salbrina and Deterding (2010) found that only one of the 12 Singapore Malay speakers in their study could be deemed to be rhotic, whereas about half of the 18 Brunei Malay speakers were rhotic. Thus, unlike MalE and Singapore English, Brunei English is more likely to be rhotic. Salbrina and Deterding (2010) attribute this to Brunei Malay which is rhotic and also to the influence of American media.

Salbrina and Deterding (2010) analysed their data, which were obtained from the Wolf Passage (Deterding 2006), both perceptually and acoustically. Words with coda /r/ in word final positions and preceding consonants were extracted from the recordings of this passage. For the acoustic analysis, the third formant (F3) of the vowel preceding /r/ was measured at its start and end. They found that the average F3 for the r-coloured vowels were significantly lower than the non-rhotic ones, thus generally confirming their perceptual findings and also showing that there is a relationship between rhoticity and lower F3 values. Tan (2012) also measured F3 to confirm her auditory analysis for instances of postvocalic, intrusive and linking-/r/.

In short, whilst rhoticity in Brunei English may be attributed to the influence of Brunei Malay, rhoticity in Singapore English appears to be developing as a prestige norm. Although the use of rhoticity may be attributed to the influence of American media, in the absence of other features of American English pronunciation and given Singapore’s “endonormative orientation” towards English (Gut 2007: 356), this feature could well be an example of an emerging feature of Singapore English pronunciation.

3 Methodology

The speakers in this study comprised 34 speakers from two age groups: 20–29, 30–45 years. The data were obtained from the Corpus of Spoken Malaysian English, which is being developed at the Faculty of Languages and Linguistics, University of Malaya (Pillai et al. 2010; Pillai, Mohd. Don, and Knowles 2012). Each group was recorded reading the North Wind and the Sun text (see Appendix). Each group comprised speakers from the three main ethnic groups in Malaysia (Malay, Chinese and Indian), to examine if there was any observable pattern of rhoticity among a particular ethnic group. The speakers in the 30–45 year old age group comprised five speakers in the Malay and Chinese groups and four in the Indian one. They were all English language teachers and lecturers who were fluent in English, and used English extensively at work and at home. In the Indian group three of the speakers said that they grew up speaking English and used English predominantly English in most contexts. All three considered English to be their first language. The 20–29 year age group consisted of undergraduate speakers who were divided into L1 and and non-L1 speakers. This was based on their answers in a questionnaire where they were asked to state what they considered to be their first and second languages. They were given the option to indicate more than one language as their first language, if they grew up speaking those languages. There were also other questions in the questionnaire which asked them to indicate what language or languages they spoke to each of their parents, and other family members, when they started learning the languages they know, and to whom and when they use these languages. As expected, the L1 group reported more frequent use of English. They used mostly English in family and social contexts, and at university.

There were five speakers in the younger L1 group (two Chinese, two Indians and one speaker of mixed parentage), and five speakers in each of the three ethnic groups in the L2 group. The first language for the Chinese group was Cantonese, and for the Indian group it was Tamil. All were undergraduates majoring in languages and linguistics. Speaker codes were devised according to (i) whether they were L1 MalE speakers; (ii) whether they were in the older (O) or younger (Y) group; (iii) their ethnic group (M = Malay, C = Chinese, I = Indian, MX = mixed parentage). A number was then allocated to each speaker in a group. For example, an older Chinese speaker may be identified as OC1, and a younger one as L1YC1.

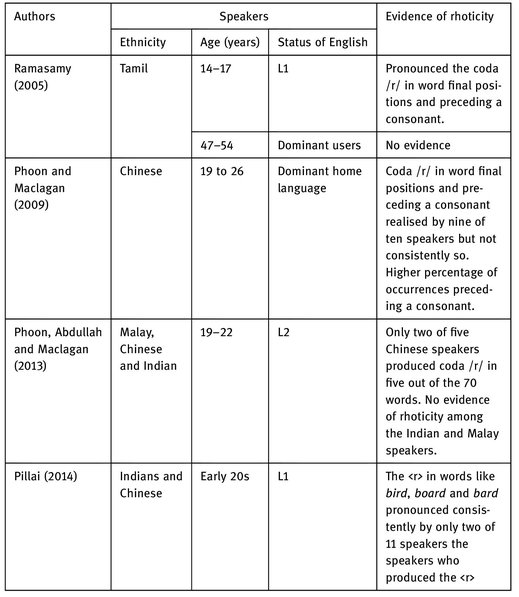

A total of 19 words per speaker were extracted from the recordings (printed in bold in the Appendix), which should have resulted in 646 tokens in all. However, one speaker (L1YI1) did not produce the second more in the text (see Appendix), and thus a total of 645 words were extracted and examined. The words which were analysed are presented in Table 2. A perceptual analysis was first carried out where the author and another researcher indicated whether they found the /r/ to be realised or not in the tokens. Using Praat Version 5.3.01 (Boersma and Weenink 2013), the values of the third formant of the vowels in both rhotic and non-rhotic tokens were then measured and compared to see if the rhotacised tokens contained vowels with a lower F3 compared to the non-rhotacised ones (Love and Walker 2012; Hayward 2000; Salbrina 2010; Salbrina and Deterding 2010). This was based on the assumption that “[v]ariations in the frequency of F3 indicate the degree of r-colouring: the lower the F3, the greater the degree of rhoticity” (Ladefoged 2003: 149). In Standard Malay, /r/ is produced as an alveolar trill. However, <r> is not always realised in word final positions (e.g. lebar) in the varieties of Malay used in Peninsular Malaysia unlike the varieties in the two states neighbouring Brunei (Aman et al 2000; Omar 1977). None of the Malay speakers or any of the other speakers participating in this study produced /r/ in the rhotic tokens as an alveolar trill or any other form of /r/ which was not an approximant. Thus, the lowering effect of F3 was not caused by other possible realisations. It should be noted that the realisations of /r/ as taps and trills reported by Chinese (Phoon and Maclagan 2009), Malay and Indian MalE speakers (Phoon, Abdullah, and Maclagan 2013) refer to /r/ in syllable onset positions and are thus, not related to instances of rhoticity.

As Salbrina and Deterding (2010: 125) point out “the correlation between lowered F3 and R-colouring is only approximate, partly because it is not always possible to derive reliable estimates of F3”. Bearing this in mind, the mid-point of the F3 of the tokens were measured, using the automatic formant tracking feature in Praat, and hand corrected where necessary.

4 Findings and discussion

The perceptual examination of the sounds, done by the author and another researcher, yielded an agreement of 97% between the two raters in the first instance. Agreement was then reached for the few cases of disagreement upon listening to the contested cases again. Based on the perceptual analysis, three speakers in the older group showed evidence of rhoticity (see Table 3). It is also interesting to note that only two speakers (L1OI3 and L1YC2), incidentally both L1 speakers, in all the recordings produced a linking /r/ in the phrase stronger of, which shows that Malaysian speakers in general do not have this phonological feature. Among the younger group, only four out of the 15 speakers produced rhotacised tokens in the non-L1 group. Contrary to expectations, only one of the L1 speakers (L1YC2) pronounced coda /r/, and this only in four of the 19 words that she read, thus debunking the assumption that the L1 speakers, particularly the younger ones, are purveyors of the emergence of rhoticity in MalE.

The findings of the acoustic analysis show that the average F3 value of the vowels preceding a pronounced coda /r/ (Mean = 2566Hz, S.D. = 418Hz) is significantly lower than that of the vowels preceding coda /r/ that was not realised (Mean = 2951Hz, S.D. = 346Hz): (t = 4.5, df = 643, independent samples, two-tailed, p < 0.001).

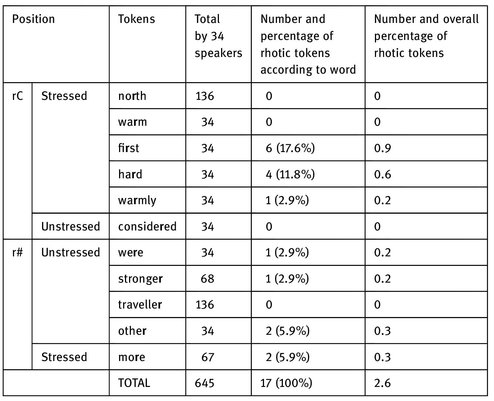

In total, only 17 out of 645 (2.6%) words were rhotic, and these were produced by only eight of the 34 or 20.6% of the 34 speakers (see Table 3 and 4). Both coda /r/ before consonants (e.g. in first, hard, warmly) and word final coda /r/ (e.g. in other, more, were, stronger) were found among these words (see Table 4). As can be seen in Table 4, the incidence of rhoticity among the stressed closed syllables (11 out of 272 or 4%) is only slightly higher than that for the stressed open syllables (2 out of 67 or 3%), and thus, given these small numbers, it is not possible to say for sure in which environments the coda /r/ is more likely to be realised. There was, however, a larger difference between rhotic tokens in the stressed syllables (13 out of 339 or 3.8%) compared to unstressed syllables (4 out of 306 or 1.3%) as can be seen in Table 4. This may be an indication that rhoticity is more common in stressed syllables.

| Speakers | Rhotacised tokens | Percentage of rhotic tokens per speaker |

|---|---|---|

| OM1 | None | 0 |

| OM2 | first hard warmly | 15.8 |

| OM3 | None | 0 |

| OM4 | first hard other | 15.8 |

| OM5 | None | 0 |

| OC1 | None | 0 |

| OC2 | None | 0 |

| OC3 | None | 0 |

| OC4 | first | 5.3 |

| OC5 | None | 0 |

| OI1 | None | 0 |

| L1OI2 | None | 0 |

| L1OI3 | None | 0 |

| L1OI4 | None | 0 |

| YM1 | None | 0 |

| YM2 | None | 0 |

| YM3 | first hard | 10.5 |

| YM4 | None | 0 |

| YM5 | None | 0 |

| YC1 | hard other | 10.5 |

| YC2 | more | 5.3 |

| YC3 | None | 0 |

| YC4 | first | 5.3 |

| YC5 | None | 0 |

| YI1 | None | 0 |

| YI2 | None | 0 |

| YI3 | None | 0 |

| YI4 | None | 0 |

| YI5 | None | 0 |

| L1YC1 | None | 0 |

| L1YC2 | first more were stronger | 21.1 |

| L1YI1 | None | 0 |

| L1YI2 | None | 0 |

| L1YMX1 | None | 0 |

None of the speakers realised more than 50% of the 19 tokens of coda /r/ in the text they read (see Table 3), which indicates that similar to Singapore English, rhoticity is not a common phenomenon among MalE speakers at this point in time. This could well be because of the influence of British English on both these postcolonial varieties, but the findings that rhoticity is being perceived as a prestige variety in Singapore English also indicates the possibility of moving from one exonormative norm to another (e.g. from British to American English). It further suggests that a pronunciation feature may at first be increasingly used due to, for example, the influence of media and entertainment (also said to be the case for Brunei English). This feature could later become accepted as part of the indigenous norm to the extent that it is no longer seen with reference to the exonormative norm, but as part of the endonormative norm.

The inconsistent use of rhoticity is also reflected in the way the same word may have the coda /r/ produced in one instance but not in another by the same speaker (e.g. more by YC2 and L1YC2, and stronger by L1YC2).

Table 4: Word position of rhotic tokens

As mentioned previously, there is also no overwhelming evidence of rhoticity among the younger L1 speakers as might have been expected. This suggests that it is not a developing pattern among those in their twenties. We can also assume that these speakers acquired a non-rhotic variety from their parents. The L1 speakers from both age groups were all non-rhotic except for L1YC2. Although this finding should be treated with caution given the small number of speakers, it may be the case that L1 speakers who have a tendency to use English more frequently and in more contexts, are not rhotic, at least not in the age groups examined.

The data in this study does not indicate any ethnically based patterns expect for the fact that none of the non-L1 Indian speakers in both age groups pronounced coda /r/. The small number of rhotic tokens produced by three Malays (two from the older group and one from the younger one) and five Chinese speakers (four from the younger group including one Chinese L1 speaker compared to one from the older group) is not sufficient enough for us to come to any conclusions about whether rhoticity is more common among the Malays and Chinese. A total of three speakers from the older group (two Malays and one Chinese), produced seven rhotic tokens compared to five speakers from the younger group who produced ten tokens (see Table 3). None of these speakers though could be considered rhotic based on their inconsistent production of the non-prevocalic /r/. Further, the production of the /r/ could be attributed to the fact that they were reading a text rather than speaking spontaneously. For example, Tan and Gupta (1992) found a higher percentage of post-vocalic /r/ being produced when their speakers were reading a passage and a word list compared to when they were being interviewed. Compared to the five younger speakers who produced a total of ten rhotacised tokens, there is no overwhelming evidence that the younger speakers were necessarily more rhotic than the older ones.

5 Conclusion

In relation to the first research question, the combination of perceptual and acoustic findings shows no consistent realisation of coda /r/ among the Malaysian speakers in this study. R-lessness therefore appears to cut across the two age-groups, the three ethnic groups and L1 and non-L1 speakers of MalE. Based on this, MalE appears to still be a non-rhotic variety. Both groups acquired this non-rhotic variety of English in Malaysia from Malaysian family members or teachers who would have presumably been non-rhotic as well. Like the older group, the younger groups (who are in their twenties) of MalE speakers, being non-rhotic, are likely to pass on this non-rhotic variety to their children or students. The findings tentatively suggest that we are not likely to see MalE become rhotic quite so soon as Brunei English (see Deterding, this volume) or as Singapore English, where rhoticity is becoming prestigious.

Given the overall inconsistent use of rhoticity among the speakers and especially the lack of rhotic realisations among the L1 speakers, there is no indication that rhoticity is developing as a prestige feature in MalE at present. Unlike Singapore, where it is reported that a “shift to an endonormative orientation [...] has been completed” (Gut 2007: 356), Malaysia is still fixated on British English as a norm. For example, it is stipulated that British English should be used as a pedagogic model: “[t]eachers should use Standard British English as a reference and model for teaching the language. It should be used as a reference in terms of spelling and grammar as well as pronunciation for standardization” (Curriculum Development Division Ministry of Education 2012: 4). There is still a general sense that the local variety of English is not “good” enough or an “incorrect” variety (Pillai 2008b) and therefore, an exonormative norm, in this case, British English, is still considered the reference model. It may be the case that the influence of American English and American media and entertainment will influence younger generations of Malaysians to become increasingly rhotic despite the current exonormative orientation towards British English. However, perhaps it is not so much about whether there is a shift from one exonormative norm to another (especially in view of the fact that other features of American English pronunciation have not been reported in MalE), but about whether rhoticity in itself becomes a distinguishing feature of or a norm in MalE. If this were the case in the future, and if there were a shift to an endonormative orientation by then, the acceptance of this feature would no longer be tied to it being a feature of American English but of MalEng.

In relation to the second and third research question, there was no obvious relationship between L1 and non-L1 speakers of English, or older and younger speakers with rhoticity although the tendency was for the latter to show more non-rhotic tendencies. Returning to the lack of rhotic tokens found in this study, whilst this would suggest that MalE is not rhotic at this point in time, the small number of speakers in this study make the findings tentative. Further studies on even younger groups of speakers from different educational and language backgrounds (e.g. international and local public schools) may reveal more about the realisation of coda /r/ in MalE. A study of speakers in Sabah and Sarawak, which border Brunei, may also show different patterns of use, as they may display more instances of rhoticity due to the variety of Malay in these States being rhotic.

Acknowledgements

The study reported in the paper was funded in part by a research grant from the University of Malaya RG159-10HNE.

References

Aman, Idris, Rosniah Mustaffa, Zharani Ahmad, Jamilah Mustafa and Mohammad Fadzeli Jaafar. 2011. Aksen standard bahasa kebangsaan: Realiti, Identiti dan Integrasi [National language standard accent: Reality, identity and integration]. In Idris Aman (ed.), Aksen bahasa kebangsaan: Realiti, identiti dan integrasi [National language accent: Reality, identity and integration], 72–82. Bangi: Penerbit Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia.

Omar, Asmah. 1977. The phonological diversity of the Malay dialects. Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka.

Baskaran, Loga. 2004. Malaysian English: Phonology. In Edgar W. Schneider, Kate Burridge, Bernd Kortmann, Rajend Mesthrie & Clive Upton (eds.), A handbook of varieties of English. Volume 1: Phonology, 1034–1046. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Boersma, Paul & David Weenink. 2013. Praat: Doing phonetics by computer. Version 5.3.57. http://www.praat.org/ (accessed 27 October 2013).

Canagarajah, A. Suresh & Adrian J. Wurr. 2011. Multilingual communication and language acquisition: New research directions. The Reading Matrix 11(1). 1–15.

Crystal, David. 1997. English as a global language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Curriculum Development Division Ministry of Education. 2012. Dokumen kurikulum standard sekolah rendah (KSSR): Bahasa Inggeris sekolah kebangsaan: Year 3 [Standard primary school curriculum document: English language for national schools: Year 3]. Putrajaya: Ministry of Education Malaysia. http://web.moe.gov.my/bpk/v2/kssr/index.php/dokumen_kurikulum/tahap_i/modul_teras_asas/bahasa_inggeris (accessed 19 January 2014).

David, Maya Khemlani, Ibtisam M. H. Naji & Sheena Kaur. 2003. Language maintenance or language shift among the Punjabi Sikh community in Malaysia? International Journal of the Sociology of Language 160–161. 1–24.

Deterding, David. 2006. The North Wind versus a Wolf: Short texts for the description and measurement of English pronunciation. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 36 (2). 187–196.

Downe, Alan G., Siew-Phaik Loke, Jessica Sze-Yin Ho & Ayankunle Adegbite Taiwo. 2012. Corporate talent needs and availability in Malaysian service industry. International Journal of Business and Management 7 (2). 224–235.

Govindan, Indira & Stefanie Pillai. 2009. English question forms used by young Malaysian Indians. The English Teacher 38. 74–94.

Gut, Ulrike. 2007. First language influence and final consonant clusters in the new Englishes of Singapore and Nigeria. World Englishes 26(3).346–359.

Hayward, Katrina. 2000. Experimental phonetics. Harlow: Longman.

Kirkpatrick, Andy. 2007. World Englishes: Implications for international communication and English language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ladefoged, Peter. 2003. Phonetic data analysis: An instruction to fieldwork and instrumental techniques. Oxford: Blackwell.

Love, Jessica & Abby Walker. 2012. Football versus football: Effect of topic on /r/ realization in American and English sports fans. Language and Speech 56 (4). 443 –460

McArthur, Tom. 2002. The Oxford guide to World Englishes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Phoon, Hooi San & Margaret Anne Maclagan. 2009. Chinese Malaysian English phonology. Asian Englishes 12 (1). 20–45.

Phoon, Hooi San, Anna Christina Abdullah & Margaret Maclagan. 2013. The consonant realizations of Malay-, Chinese- and Indian-influenced Malaysian English. Australian Journal of Linguistics 33 (1). 3–30.

Pillai, Stefanie. 2008a. A study of the use of English among undergraduates in Malaysia and Singapore. Southeast Asian Review of English 48. 19–38.

Pillai, Stefanie. 2008b. Speaking English the Malaysian way: Correct or not? English Today 96 (24.4). 42–45.

Pillai, Stefanie. 2012. Colloquial Malaysian English. In Bernd Kortmann & Kerstin Lunkenheimer (eds.), The Mouton world atlas of variation in English, 573–584. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Pillai, Stefanie. 2014. The monophthongs and diphthongs of Malaysian English: An instrumental analysis. In Hajar Abdul Rahim & Shakila Abdul Manan (eds.), English in Malaysia: Postcolonial and beyond, 55–86. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Pillai Stefanie & Mahmud Hasan Khan. 2011. I am not English but my first language is English: English as a first language among Portuguese Eurasians in Malaysia. In Dipika Mukherjee & Maya Khemlani David (eds.), National language planning and language shifts in Malaysian minority communities: Speaking in many tongues, 87–100. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Pillai, Stefanie, Zuraidah Mohd. Don, Gerald Knowles & Jennifer Tang. 2010. Malaysian English: An instrumental analysis of vowel contrasts. World Englishes 29 (2). 159–172.

Pillai, Stefanie, Zuraidah Mohd. Don & Gerald Knowles. 2012. Towards building a model of Standard Malaysian English pronunciation. In Zuraidah Mohd. Don (ed.), English in multicultural Malaysia: Pedagogy and applied research, 195–211. Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press.

Poedjosoedarmo, Gloria. 2000. The media as a model and source of innovation in the development of Singapore Standard English. In Adam Brown, David Deterding & Low Ee Ling (eds.), The English language in Singapore: Research on pronunciation, 112–120. Singapore: Singapore Association for Applied Linguistics.

Rajadurai, Joanne. 2006. Pronunciation issues in non-native contexts: A Malaysian case study. Malaysian Journal of ELT Research 2. 42–59.

Ramasamy, Sheila Adelina. 2005. Analysis of the usage of post vocalic /r/ in Malaysian English. Kuala Lumpur, University of Malaya MA research report.

Salbrina, Sharbawi. 2010. The sounds of Brunei English: 15 years on. South East Asia: A Multidisciplinary Journal 10. 39–56.

Salbrina, Sharbawi & David Deterding. 2010. Rhoticity in Brunei English. English World-Wide 31 (2). 121–137.

Schiffman, Harold F. 1995. Language shift in the Tamil communities of Malaysia and Singapore: The paradox of egalitarian language policy. Southwest Journal of Linguistics 14 (1–2). 151–165.

Schneider, Edgar W. 2003. The dynamics of new Englishes: From identity construction to dialect birth. Language 79(2). 233–281.

Tan, Ying-Ying. 2012. To r or to to r: Social correlates of /ɹ/ in Singapore English. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 218. 1–24.

Tan, Chor Hiang & Anthea Fraser Gupta. 1992. Post-vocalic /r/ in Singapore English. York Papers in Linguistics 16. 139–152.

The National Graduate Employability Blueprint 2012–2017. 2012. Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia Putrajaya 2012. http://jpt.mohe.gov.my/PENGUMUMAN/GE%20blueprint%202012–2017.pdf (accessed 30 March 2014).

Trudgill, Peter & Jean Hannah. 2008. International English: A guide to the varieties of Standard English, 5th edn. London: Hodder Education.

Appendix

The North Wind and the Sun were disputing which was the stronger when a traveller came along wrapped in a warm cloak. They agreed that the one who first succeeded in making the traveller take his cloak off should be considered stronger than the other. Then the North Wind blew as hard as he could but the more he blew the more closely did the traveller fold his cloak around him and at last the North Wind gave up the attempt. Then the Sun shone out warmly and immediately the traveller took off his cloak. And so the North Wind was obliged to confess that the sun was the stronger of the two.