11 Prosodic marking of focus in transitivesentences in varieties of South AfricanEnglish50

1 Introduction

English is one of the official languages in South Africa and the language of teaching and learning. Nevertheless, English in South Africa is not a homogeneous variety. Despite the end of apartheid South Africa remains a heterogeneous society with the different ethnic groups in the country having their own culture and language. The resulting recognisable varieties of English that coexist in the country are still referred to with reference to ethnic groups such as Indian, Black, Coloured and White South African English. The differences in the phonological systems of these varieties have been described in the respective chapters in Mesthrie (2008).

There are not only differences across different ethnic varieties, but also the English spoken within an ethnic group shows considerable linguistic variation across speakers. The present chapter focuses on the speech of Black speakers.51 Black South African English (BlSAfE) emerged as an ethnic variety of South African English due to the segregation politics of apartheid South Africa (1948 to 1994). Its speakers are multilingual in one or more of the local Bantu languages and English. BlSAfE has phonological and syntactic features (van Rooy 2004) which clearly mirror the influence of the local Bantu languages. Because of this discernible influence of the local Bantu languages, this variety will be

Sabine Zerbian, University of Stuttgart & University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg

referred to as an L2 variety. This variety continues to exist in present-day South Africa. However, due to Black economic empowerment and increased opportunities in education and profession, a middle class has emerged among the Black population. The linguistic norms of this group differ remarkably from BlSAfE. Although these speakers are largely still multilingual in English and one or more of the South African Bantu languages, their English does not immediately show phonological and/or syntactic markers of this multilingual background. Mesthrie (2010: 13) suggests that a new dialect has emerged and characterises this accent as “the prestige styles used by young people of colour, who have non-racial peer groups and behave in ways associated traditionally with Whites”. He proposes the sociolinguistic term “crossing over” to be used for this accent “that is not traditionally associated with people of one’s presumed ethnicity” (Mesthrie 2010: 13). This term will also be used here to refer to this “new” variety among Black speakers.

More and more studies investigate segmental aspects pertaining to vowels in the “new” variety of Black middle-class speakers (Da Silva 2008; Mesthrie 2010; Wilmot 2014). They find that although white norms might be approached and even adopted by some speakers (e.g. Black females’ /u/-fronting, Wilmot 2014), the variety is not identical to White South African English (WSAfE) (Mesthrie 2010). The present study addresses the considerably lesser-studied aspect of variation in suprasegmental phonology among the group of Black multilingual speakers of both the “crossing over” variety and BlSAfE, with the aim of finding out if the same constraints on the outcome operate in English as a second language (L2) or as a “new” variety. Data from these two varieties are compared to the speech of monolingual speakers of WSAfE.

The suprasegmental phenomenon under consideration is the use of prosody for the marking of focused and given constituents. In English, prosodic focus marking results in an increase of intensity, length and fundamental frequency on the focused constituent, making it prosodically prominent. At the same time, constituents which are given in discourse are deaccented. The Bantu languages of South Africa, which always are the first and/or additional languages of Black speakers of South African English, have not been reported to use purely prosodic means to mark focused or given constituents (Zerbian 2007 for Northern Sotho; Swerts and Zerbian 2010 for Zulu). Rather, morphosyntactic means such as left- and right-dislocation of given constituents are used (cf. Zerbian 2006 for Northern Sotho). Thus, the difference in the use of prosody between English and the South African Bantu languages makes the South African English of multilingual speakers interesting varieties to study. Zerbian (2013) investigated acoustic cues of focusing nouns and adjectives in modified noun phrases in groups similar to the ones in the current study. It was found that speakers of BlSAfE do not manipulate F0 and intensity on the basis of focus. Speakers of the “crossing over” variety (termed “postacrolect” in Zerbian 2013) do not change intensity for focus marking. This study used semi-spontaneous speech, and the results indicate that a difference exists in the phonetic implementation of prosody across these three varieties.

The present chapter presents the results of a study which tested the same research question, this time using read speech and, more importantly, varying focus within a sentence (and not within a noun phrase as in Zerbian (2013)). The domain of deaccenting is said to vary across languages: Whereas English deaccentuates both within phrases and sentences, Egyptian Arabic does not deaccentuate neither within sentences nor within phrases (Hellmuth 2005), and Italian has been reported to allow deaccenting within sentences but not within phrases (Ladd 1996: 177). It is therefore necessary to test whether the phonetic implementation of focus in these varieties differs also in sentences. At the same time, the current chapter interprets the results of both studies to address one of the leading questions of the volume, namely whether the same phonological constraints operate in English as a L2 or as a “new” variety.

The article is structured as follows: Section 2 provides the background concerning prosodic marking of information structure (focus and givenness) in WSAfE, by presenting the results of an experimental study for this group of speakers. It will emerge that in WSAfE focus and givenness are marked prosodically in a similar way to what has been reported for other L1 varieties of English, such as Southern Standard British English or General American English. Sections 3 and 4 present the results of the same study conducted with Black speakers of South African English for the two varieties described above. Section 5 discusses the results.

2 Prosodic marking of focus and givenness inWhite South African English

2.1 Background

The prosodic marking of focused constituents in transitive sentences in English is well-researched. It is generally agreed that the nuclear accent shifts to the constituent in focus (in (1a), (1b) and (1c) indicated by capital letters), resulting in a significant increase of fundamental frequency (F0), duration and intensity on the primarily stressed syllable of this constituent as compared to a non-focused rendering (see Breen et al. 2010 for a recent review). The prosodic prominence that accompanies focus in English can in principle be realised on all lexical categories in a transitive sentence, i.e. on the subject, the verb or the object.

In (1), as in the experiment to be reported on below, focus on a constituent is unambiguously established by means of a preceding wh-question. This approach follows a definition of focus as an indication of alternatives (cf. Krifka 2008).

- (1)

- What may Lila mow?

Lila may mow [the MEAdow]F.

- Who will mow the meadow?

[LIla]F may mow the meadow.

- What may Lila do to the meadow?

Lila may [MOW]F the meadow.

- What may Lila mow?

The following subsection lays out in detail the methodology with which the data were collected from speakers of the varieties of South African English under consideration in the present study.

2.2 Methodology

The methodology closely resembles the paradigm first used by Xu (1999) for Mandarin Chinese and subsequently applied to other languages, such as English in Xu & Xu (2005). A similar paradigm was also followed by Breen et al. (2010) for General American English.

2.2.1 Material

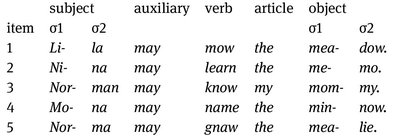

Five stimulus sentences were created that were comparable in segmental make-up. 52 The stimulus sentences are shown in (2).

- (2) Stimulus sentences

To control for focus, each stimulus sentence was preceded by a question, evoking broad focus as well as focus on the subject, verb and object respectively, thus rendering the other constituents discourse-given by having been explicitly mentioned in the question. The answers were presented in writing on a screen, together with their questions, accompanied by a picture illustrating the action. Each sentence occurred once in each focus condition. One additional set was provided to become familiar with the task but was excluded from analysis. The repetitions necessary for quantitative analyses were thus provided by the five different stimulus sentences rather than by repetitions of identical sentences. The same order of focused constituent was maintained across all 5 sets: Broad focus, subject focus, verb focus and finally object focus. Sentences with differing focus structures followed each other directly without any intervening fillers in order to make speakers aware of the potential for ambiguity. It was decided that the stimuli sentences were presented in direct contrast to each other and not randomised (cf. Xu 1999), because sometimes speakers only reliably mark contrasts when they are made aware of ambiguity (cf. Snedeker and Trueswell 2003; Breen et al. 2010: 1089). In addition, the focused target words were underlined in the answers in order to reduce errors (cf. Xu 1999). The reasoning is that if prosodic means are available to speakers they will then know exactly where to produce them (due to underlining) and no errors occur because of the focus structure not having been processed correctly. If no prosodic means are available to the speaker, then the underlining will not be able to evoke prominence anyway.

2.2.2 Recording

Recordings were conducted in a quiet office at the Department of Linguistics of the University of Cape Town in February/March 2012. A microphone was placed approximately 20 to 30 cm in front of the participant’s mouth. Participants were asked to read out loud both the question and the answer, before proceeding to the next slide at their own pace. In case of hesitations, the participants were asked to repeat both the question and the answer. Three sets of stimuli sentences were presented together, and after a short break, in which a different task was administered, another two sets of stimuli sentences were presented.

2.2.3 Subjects

Data from nine white speakers were analysed for whom English was their first and only language. They are speakers of General South African English (GenSAfE), the standard variety spoken predominantly by white middle-class speakers (Bekker 2009). The term GenSAfE does not refer to any specific ethnicity and is used in the present chapter when this specific reference is not considered relevant. They were aged between 18 and 23, and were students at the University of Cape Town in different disciplines. Five speakers were male, four were female.

2.2.4 Preparation of data analysis

The recordings were directly digitised onto the hard disk of a PC laptop for further analysis. Syllables were delineated and are the unit of display in the graphs in Figures 1 to 8. Data extraction was carried out using ProsodyPro (Xu 2013) for the software Praat (Boersma and Weenink 2012). Praat provides automatic vocal pulse marking which was manually corrected for missing or incorrect values in case of obvious octave jumps, using the ProsodyPro script. The data were first inspected visually for F0 changes over the course of the utterances. Subsequently, duration, mean F0 and mean intensity were measured for the stressed syllables of the subject, object and verb.

2.3 Results for White South African English

2.3.1 Visual inspection of F0 contours

As a first approach to the data, F0 contours averaged across stimuli and speakers were inspected for each focus condition. There are four logical possibilities of how focus and givenness can be realised prosodically: (1) through prosodic marking of the focused constituent, (2) through prosodic marking of given constituents, and (3) by prosodic marking of both the focused and the given constituents. Furthermore, speakers may (4) not use any prosodic marking at all.

The following two parameters were thus considered when inspecting the F0 contours visually:

- – To what extent is there prosodic focus marking, i.e. to what extent do focused constituents show on average an increased pitch compared to a baseline of broad focus?

- – To what extent is there givenness marking, i.e. to what extent is a lower pitch observable on given elements as compared to a baseline of broad focus?

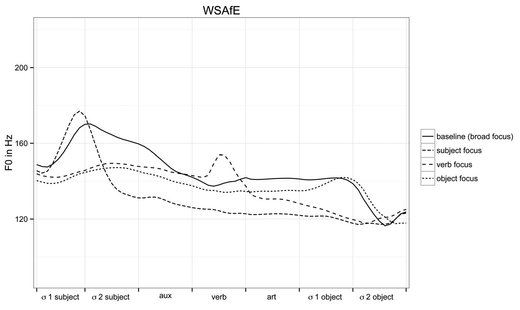

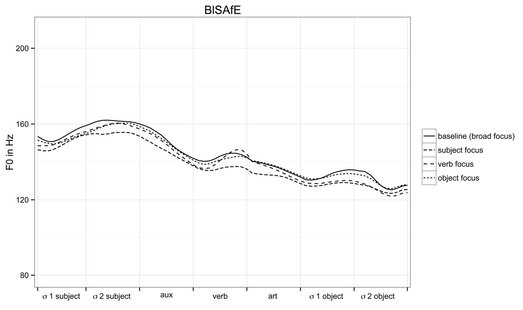

The answer to the broad focus question “What is happening?” served as the baseline as it represents an all-new utterance in which no constituent is particularly in focus. The following graph shows the F0 contours averaged across the five stimulus sentences and across speakers. In order to account for gender-related differences in pitch among speakers, the F0 values obtained for each speaker were first converted to their logarithms (using the log() function in R). The logarithmic values were averaged across all sentences and speakers, and the resulting mean was converted back to Hz values for the visual display in Figure 1. In all figures, a pitch range of 130 Hz is displayed. Data are time-normalised by taking ten measures of each syllabic interval. For the labels of the x-axis see (2).

The solid line represents the baseline. In comparison to the baseline we find that focus results in a higher F0 in the case of subject and verb focus for these speakers of WSAfE. Givenness results in a lower F0 as compared to the baseline and moreover in postfocal deaccentuation in the case of subject and verb focus. In the case of object focus, the accent on the object is nearly as high as the one on the subject. In the broad focus context, the pitch accent on the object is realised lower than the one on the subject. In object focus context, both pitch accents are of equal height, rendering the second accent perceptually more prominent. A qualitative analysis of the pitch patterns speaker-by-speaker reveals that eight out of nine speakers mark focus and givenness prosodically by either pitch lowering only (3/9) or by both pitch lowering and pitch expansion (5/9). Only one speaker does not seem to apply either. In sum, what can be seen from the graphical display in Figure 1 is that in WSAfE we find clear marking of both focus and givenness by means of F0.

Figure 1: F0 average across all speakers and utterances for WSAfE

2.3.2 Inferential analysis

In order to further examine prosodic focus and givenness marking, the three acoustic parameters relevant for focus, namely maximum F0, intensity and duration, were measured on the stressed syllables of the subject, object and the full verb. Linear mixed models (Bates and Sarkar 2007) were fitted with maximum F0/duration/intensity of the stressed syllable as the dependent variable, focus as a fixed factor and speaker as a random factor. This was done in order to investigate whether these three measures are significantly different from each other when comparing focused and given constituents to the baseline of all-new sentences. The results are presented for each of the measures in turn and are summarised in 2.4.

2.3.2.1 Maximum F0

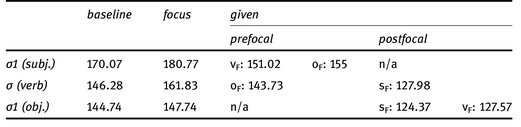

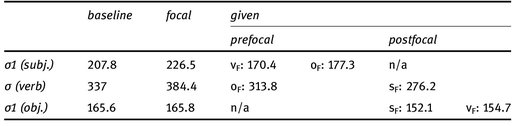

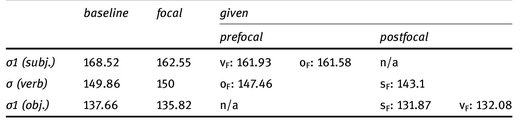

The mean values of maximum F0 for each of the constituents across all utterances and speakers are presented in Table 1 (using log-values in the analysis, cf. 2.3.1.). The results of the linear mixed models are given below. The significance level was set at p = 0.05.

Table 1: Means of maximum F0 of stressed syllables, differentiated by focus condition (in Hz)

For prosodic focus marking by means of F0 it was found that

- – a focused subject has a significantly higher F0 than a subject in the baseline (t = –2.66; p = 0.0086)

- – a focused verb has a significantly higher F0 than a verb in the baseline (t = –4.08; p < 0.001)

- – a focused object does not differ significantly in F0 from an object in the baseline (t = –0.7; p = 0.486)

For givenness marking by means of F0 it was found that

- – a given subject has a significantly lower F0 than a subject in the baseline, both in the case of verb focus (VF) and object focus (OF) (vF: t = –5.12; p < 0.001; oF: t = –6.21; p < 0.001)

- – a given verb only has a significantly lower F0 than a verb in the baseline if it appears postfocally, thus in the case of subject focus (sF: t = 5.46; p < 0.001), but not if it occurs prefocally as in the case of object focus (oF: t = –0.72; p = 0.4735)

- – a given object has a significantly lower F0 than an object in the baseline, both in the case of verb focus (VF) and subject focus (SF) (sF: t = –5.16; p < 0.001; vF: t = –4.24; p < 0.001)

2.3.2.2 Duration

In order to examine whether duration is influenced by information structure (focus/givenness), duration was measured on the stressed syllables of the subject, the object and the full verb. The mean values across all utterances and speakers are presented in Table 2.

Table 2: Means of duration of stressed syllables, differentiated by focus condition (in ms)

In order to test whether the differences in duration between the different conditions are significant, a linear mixed model was fitted with duration of the stressed syllable as the dependent variable, focus as a fixed factor and both speaker and item as random factors. Item was chosen to be included as a random factor because there are some slight differences in segmental structure between the different target sentences.

For prosodic focus marking by means of duration it was found that

- – a focused subject has a significantly longer duration than a subject in the baseline (t = −2.3; p = 0.0227)

- – a focused verb is significantly longer than a verb in the baseline (t = −2.812; p = 0.0055)

- – a focused object is not significantly longer as compared to the baseline (t = −0.044; p = 0.9651)

For prosodic givenness marking by means of duration it was found that

- – a given subject has a significantly shorter duration than a subject in the baseline both in the case of verb focus and object focus (vF: t = −4.543; p < 0.001; oF: t = −3.755; p < 0.001)

- – a given verb is significantly shorter only postfocally, i.e. in the case of subject focus (sF: t = −3.662; p < 0.001), not prefocally, i.e. in the case of object focus (oF: t = −1.399; p = 0.1638)

- – a given object is significantly shorter both in the case of subject and verb focus (sF: t = −3.719; p < 0.001; vF: t = −2.959; p = 0.0036)

2.3.2.3 Intensity

The mean values of intensity in the stressed syllable of subject, verb and object across all utterances and speakers are presented in Table 3.

Table 3: Means of intensity of stressed syllables, differentiated by focus condition (in dB)

For prosodic focus marking by means of intensity it was found that

- – a focused subject does not have significantly higher intensity than a subject in the baseline (t = –0.52; p = 0.6061)

- – a focused verb does not have significantly higher intensity than a verb in the baseline (t = –0.53; p = 0.5937)

- – a focused object does not have significantly higher intensity than an object in the baseline (t = 0.52; p = 0.6063)

For prosodic givenness marking by means of intensity it was found that

- – a given subject has a significantly lower intensity than a subject in the baseline both for verb and object focus (vF: t = −3.09; p = 0.0024; oF: t = −3.22; p = 0.0016)

- – a given verb has a significantly lower intensity than a verb in the baseline both pre- and postfocally (oF: t = −2.37; p = 0.019; sF: t = −6.77; p < 0.001)

- – a given object has a significantly lower intensity than an object in the baseline (sF: t = −8.27; p < 0.001; vF: t = −5.73; p < 0.001)

2.4 Summary of the results for WSAfE

The inferential analysis of F0 confirms the visual impression shown in section 2.3.1. We find a significant on-focus F0 increase in this group of speakers for subject and verb focus. We also find off-focus F0 lowering when comparing a given subject to its realisation in the baseline. For the verb, F0 lowering can only be observed for postfocal but not for prefocal occurrence. The F0 lowering on given subjects renders an object prosodically prominent although it is itself not marked with on-focus pitch expansion.

For duration, a corresponding pattern emerges. The durations of the stressed syllable of the verb and subject are significantly longer in the focus condition than in the baseline condition. Given constituents are nearly always shorter than the same constituents in the baseline condition. For the verb, a distinction into prefocal and postfocal has to be made: only postfocal verbs are shorter than in the baseline.

For intensity realisation, there is no significantly increased intensity rise on the focused constituent as compared to the baseline. We do find consistent intensity decreases on given constituents though: Intensity drops on the subject when another constituent is in focus. For verb and object, we find an intensity decrease if they occur after the focused constituent. Again, the verb shows a slight difference in intensity reduction between pre- and postfocal position although the intensity decrease is significant in both instances.

Thus, the overall pattern of prosodic focus and givenness marking found in WSAfE is similar to the one reported for Southern Standard British English and General American English (cf. Breen et al. 2010 for a recent overview). Prosodic marking for both focus and givenness can be found. The acoustic parameters F0, duration and intensity conspire to render the focused element prosodically prominent by either increased pitch, loudness and duration and/or decreased values in the ways described in detail above.

Against this background, the realisation by Black speakers of South African English will be discussed in the following two sections, starting with Black speakers of the “crossing over” variety in section 3 and continuing with the L2 BlSAfE in section 4.

3 Prosodic marking of focus and givenness in the“crossing over” variety of Black speakers

3.1 Methodology and speakers

The methodology followed the one described in section 2.2. for the speakers of WSAfE. Data of seven Black speakers of the “crossing over” variety were analysed. They were aged between 18 and 22, and were students at the University of Cape Town in different disciplines. Six of them were female, one was male. All speakers were multilingual, speaking English and one or more of the South African Bantu languages (Xhosa (3), Zulu (3), Pedi (1), and Tswana (1); one speaker gave two languages). Their pronunciation was judged by two trained linguists to resemble GenSAfE, showing no obvious linguistic traces of the South African Bantu languages. Self-reports showed that all speakers in this group had attended a private or ex-model-C high school. Both school types are dominantly White or mixed in terms of peer structure. The term “ex-model-C”, when used in describing South African schools, refers to those schools which were formerly reserved for Whites and which in the early 1990s, when these schools were opened to other race groups, elected to receive state funding of staff members, while allowing for their own policies of admission. Such schools retain a reputation for providing a better education than other public schools and many have seen a significant influx of black students since even before the end of apartheid, leading to a more racially-integrated situation in these schools, where students have more access to GenSAfE norms than is the case in government schools (cf. Hofmeyr 2000).

Recording, data preparation and analysis followed the same protocol as reported in sections 2.2. and 2.3. The results will be presented in a parallel fashion, with a summary in section 3.4.

3.2 Visual inspection

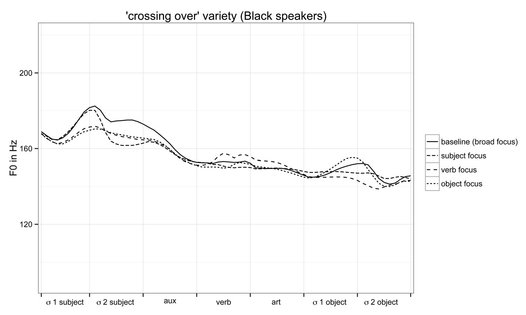

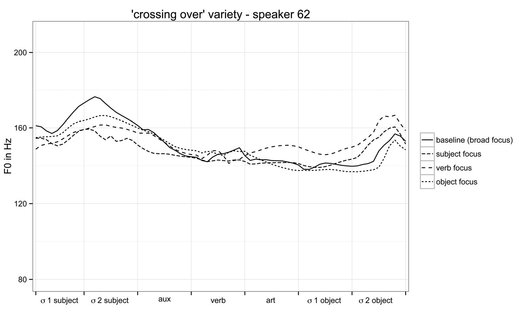

Figure 2 shows the F0 contour averaged across all stimuli sentences and all speakers for the four focus conditions. Values have been normalised for F0 and are shown in a pitch range of 130 Hz.

Figure 2: F0 averages across all speakers and utterances for the “crossing over” variety (Black speakers)

For the group as a whole, F0 is slightly increased on the focused constituents. Given subjects are realised below the baseline, given verbs are realised like the baseline, and given objects have lower F0 values. The pattern is not as clear as with the speakers of WSAfE though. Looking at each speaker individually, we find that two patterns emerge across the seven speakers.

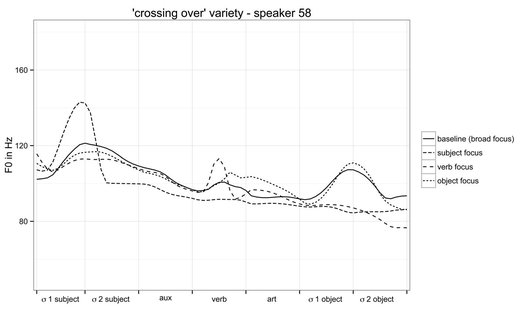

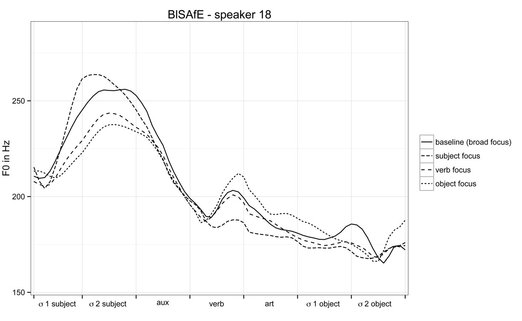

In two speakers53, we find that F0 is manipulated depending on focus by both F0 increase on the focused constituent and F0 decrease on the postfocal constituents as compared to the baseline. The F0 pattern is similar to the one seen in WSAfE. An example is provided in Figure 3.54

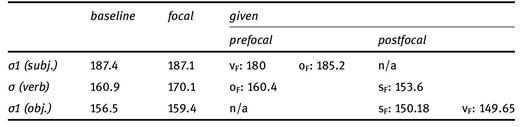

Five speakers55 do not seem to manipulate F0 on the basis of focus in any systematic way, neither in marking the prominent syllable with an F0 peak nor by lowering the pitch of given elements. An example is provided below in Figure 4 (note that this speaker consistently produces high rising terminals).

Figure 3: F0 averages for speaker 58 (male, “crossing over” variety, Tswana speaker)

Figure 4: F0 averages for speaker 62 (female, “crossing over” variety, Zulu speaker)

3.3 Inferential analysis

As before, the three acoustic measures relevant for focus, namely maximum F0, intensity and duration, were measured on the stressed syllables of the subject, object and the full verb. Linear mixed models were fitted with maximum F0/duration/intensity on the stressed syllable as the dependent variable, focus as a fixed factor and speaker as a random factor. This was done in order to investigate whether these three measures are significantly different from each other when comparing focused and given constituents to the baseline. The results are presented for each of the measures in turn and are summarised in 3.4.

3.3.1 Maximum F0

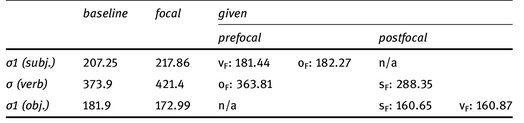

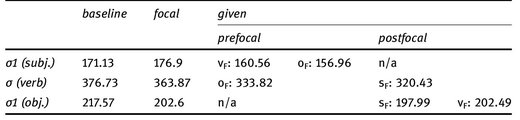

The mean values across all utterances and speakers are presented in Table 4. The results of the linear mixed models are reported below.

Table 4: Means of maximum F0 of stressed syllables, differentiated by focus condition (in Hz)

For prosodic focus marking by means of maximum F0 it was found that

- – a focused subject is not significantly higher in F0 than in the baseline (t = 0.66; p = 0.5125)

- – a focused verb is significantly higher in F0 than in the baseline (t = –3.33; p = 0.0011)

- – a focused object is not significantly higher in F0 than in the baseline (t = –0.74; p = 0.4606)

For prosodic givenness marking by means of maximum F0 it was found that

- – a given subject is marginally significantly lower in F0 as in the baseline in the case of verb focus but not significantly lower in F0 in object focus (vF: t = −2.65; p = 0.0092; oF: t = −1.19; p = 0.2346)

- – a given verb is only postfocally significantly lower in F0 than in the baseline, i.e. in the case of subject focus (sF: t = −2.72; p = 0.0075), not prefocally, i.e. in the case of object focus (oF: t = −0.17; p = 0.8668)

- – a given object is not significantly lower in F0 than in the baseline (sF: t = −1.70; p = 0.0912; vF: t = −1.87; p = 0.0646).

3.3.2 Duration

The mean values across all utterances and speakers are presented in Table 5. The results of the linear mixed models are reported below.

Table 5: Means of duration of stressed syllables, differentiated by focus condition (in ms)

For prosodic focus marking by means of duration it was found that

- – a focused subject is not significantly longer than in the baseline (t = 0.939; p = 0.3496)

- – a focused verb is not significantly longer than in the baseline (t = −1.759; p = 0.0812)

- – a focused object is not significantly longer than in the baseline (t = 1.549; p = 0.124)

For prosodic givenness marking by means of duration it was found that

- – a given subject is significantly shorter than in the baseline (vF: t = –2.31; p = 0.0227; oF: t = −2.234; p = 0.0274)

- – a given verb is significantly shorter than in the baseline only postfocally, i.e. in the case of subject focus (sF: t = −3.135; p = 0.0022), not prefocally in the case of object focus (oF: t = −0.373; p = 0.7096)

- – a given object is significantly shorter than in the baseline in both subject and verb focus (sF: t = −3.66; p < 0.001; vF: t = −3.661; p < 0.001)

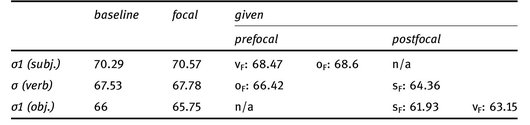

3.3.3 Intensity

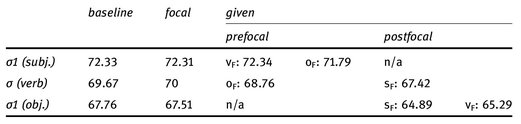

The mean values across all utterances and speakers are presented in Table 6. The results of the linear mixed models are reported below.

Table 6: Means of intensity of stressed syllables, differentiated by focus condition (in dB)

For prosodic focus marking by means of intensity it was found that

- – a focused subject does not have a significantly higher intensity than a subject in the baseline (t = 0.04; p = 0.9674)

- – a focused verb does not have a significantly higher intensity than a verb in the baseline (t = −0.55; p = 0.5822)

- – a focused object does not have a significantly higher intensity than an object in the baseline (t = 0.38; p = 0.7028)

For prosodic givenness marking by means of intensity it was found that

- – a given subject does not have a significantly lower intensity than a subject in the baseline (vF: t = 0.01; p = 0.9889; oF: t = −0.95; p = 0.3433)

- – only in the postfocal position does a given verb have a significantly lower intensity than in the baseline (sF: t = −3.72; p < 0.001). The same is not true for the prefocal occurrence in case of object focus (oF: t = −1.52; p = 0.1316)

- – a given object has a significantly lower intensity than an object in the baseline, both in subject and verb focus (sF: t = −4.36; p < 0.001; vF: t = −3.79; p < 0.001)

3.4 Summary of the results for the “crossing over” variety ofBlack speakers

There is more variation and a less consistent pattern in the use of prosody for the marking of focus and givenness in the “crossing over” variety of Black speakers. Average maximum F0 is only increased in the case of verb focus as compared to the baseline. In subject and object focus, no increase of F0 takes place. This is contrary to speakers of WSAfE, who show a significantly higher F0 in the focus conditions for all constituents except objects. For F0 on given constituents, it emerges that F0 is only significantly lower on the subject when the verb is focused and on postfocal verbs. This last finding concerning the verb is in agreement with Xu and Xu’s (2005) work on English and with the findings for the speakers of WSAfE, namely that there is a clear difference between pre-and postfocal focus and givenness in verbs. Moreover, the effect in the “crossing over” variety of Black speakers is not as strong as in WSAfE.

Concerning duration, the primary stressed syllable of a focused constituent is never lengthened compared to the baseline rendition. The stressed syllables of given constituents (except a prefocal verb) are considerably shortened as compared to the baseline.

As for intensity, there is no difference in intensity on a focused constituent compared to its rendition in the baseline, similar to what was found for speakers of WSAfE. For the subject, no difference in intensity can be found when comparing given realisations to the baseline. Thus, this group of speakers does not realise the decrease in intensity observed in the group of speakers of WSAfE. For the verb and object, there is a decrease in intensity in the given realisation when the constituents occur postfocally. For the verb, a real difference emerges between prefocal and postfocal realisation. This is parallel to what was found for speakers of WSAfE.

4 Prosodic marking of focus and givenness inBlSAfE (L2 by Black speakers)

4.1 Methodology and speakers

The methodology followed the one described in section 2.2. Data of 18 speakers of BlSAfE were analysed. The speakers were aged between 18 and 25, and were students at the University of Cape Town in different disciplines. Eight were male speakers, 10 were female. All speakers were multilingual, speaking English and one or more of the South African Bantu languages (Zulu (5), Xhosa (5), Sotho (2), Pedi (3), Tswana (2), Tsonga (2), Venda (2); three speakers gave two languages). Despite the different Bantu languages represented in this group, they are considered together as Wissing (2002) argues that there are no major differences by home (or ancestral) language, at least at the segmental level. Their English pronunciation showed clear traces of the South African Bantu languages, as confirmed by the two trained linguists who also listened to the speakers of the “crossing over” variety (see van Rooy 2004 for the phonological features of this variety). The group was slightly heterogeneous in terms of schooling background. Self-reports show that eight speakers of this variety had attended ex-DET schools in the past. The acronym “DET” stands for “Department of Education and Training” and refers to schools which were under the jurisdiction of this department and which were formerly for black students only. Such schools are often referred to as “township schools”, alluding to the fact that they usually serve township communities and are usually located in such areas. They are considered to provide an education which is lower in quality to that provided by other public schools, as these schools were under-resourced during apartheid. As the vast majority of students and teachers in these schools are black and there are very few, if any speakers of GenSAfE in these schools, access to GenSAfE norms through socialisation is minimal as there has been less racial integration in these schools (cf. Hofmeyr 2000). The other speakers had attended either government schools or, in two cases, ex-model-C schools.

A differentiation is commonly made in the literature on BlSAfE into mesolect and acrolect (e.g. van Rooy 2004). The acrolect, by definition, is closer to GenSAfE, but has been shown to be characterised by considerable variation in its vowel system (van Rooy 2004: 139). Observations like these led Mesthrie (2010: 28) to conclude that no stable acrolect of BlSAfE has developed. So even among educated speakers, such as the students who participated in the current study, considerable variation is expected to occur.

Recording and data preparation followed the same protocol as reported in sections 2.2. and 2.3. The results are presented in a parallel fashion, with a summary of the results in section 4.4.

4.2 Visual inspection

Figure 5 shows the pitch contour averaged across all stimuli sentences and all speakers for the four focus conditions. Again, values have been converted to their log-values for averaging, cf. 2.3.1.

For the group as a whole, we see only very fine differences in F0 between focus contexts. There seems to be accentuation on postfocal constituents in both subject and verb focus with very slightly reduced F0. No clear evidence exists for on-focus F0 increase.

A speaker-by-speaker investigation shows considerable variation as was to be expected in this group. Three of the four logical possibilities of focus marking are attested. For six speakers (6/18) F0 is manipulated on the basis of focus by both F0 increase on the focused constituent and F0 decrease on postfocal constituents in at least some cases. The marking is clearer in some cases than in others. Overall, the pitch differences are very small. An example is given in Figure 6.56

Figure 5: F0 averages across all speakers and utterances for BlSAfE

Figure 6: F0 averages for speaker 18 (female, BlSAfE, speaker of Tswana and Tsonga)

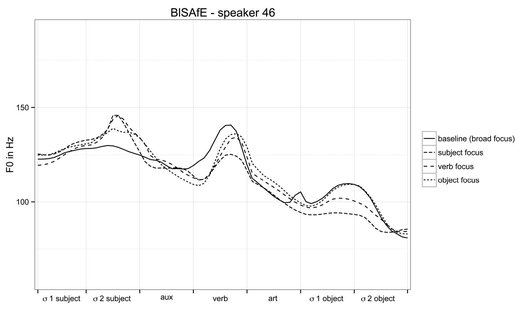

Four speakers (4/18) do not show a pitch peak on the focused constituent but do show (very slight) lower pitch on some postfocal elements. Again, the differences are often rather subtle, as in the example in Figure 7.57

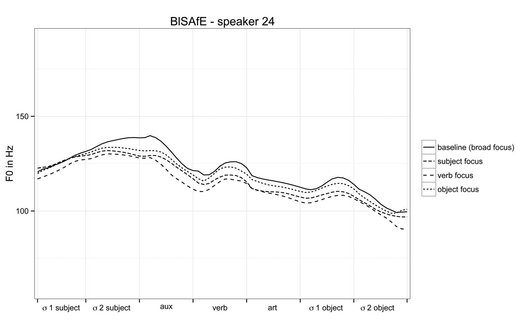

Eight speakers (8/18) do not seem to manipulate F0 depending on focus, neither in marking the prominent syllable with an F0 increase nor by lowering F0 on postfocal elements, as illustrated in Figure 8.58

Figure 7: F0 averages for speaker 46 (male, BlSAfE, Xhosa speaker)

Figure 8: F0 averages for speaker 24 (male, BlSAfE, Tsonga speaker)

4.3 Inferential analysis

In order to examine whether any consistent cues emerge in the prosodic marking of focus and givenness in the group as a whole, the three acoustic parameters relevant for prominence, namely maximum F0, intensity and duration, were measured on the stressed syllables of the subject, object and the full verb. Linear mixed models were fitted with maximum F0/duration/intensity of the stressed syllable as the dependent variable, focus condition as a fixed factor and speaker as a random factor. The results are presented for each of the measures in turn and are summarised in section 4.4.

4.3.1 Maximum F0

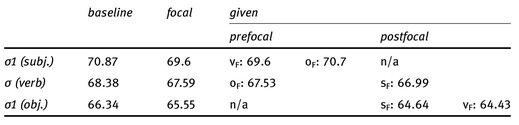

The mean values of maximum F0 across all utterances and speakers are presented in Table 7 (with their log-values used for analysis, see 2.3.1.).

Table 7: Means of maximum F0 of stressed syllables, differentiated by focus condition (in Hz)

For prosodic focus marking by means of F0 it was found that

- – a focused subject has a significantly lower F0 than a subject in the baseline (t = 3.55; p < 0.001)

- – a focused verb does not have a significantly higher F0 than a verb in the baseline (t = –0.1; p = 0.92)

- – a focused object does not differ significantly in F0 from an object in the baseline (t = 1.77; p = 0.0783)

For givenness marking by means of F0 it was found that

- – a given subject has a significantly lower F0 than a subject in the baseline (vF: t = −3.93; p < 0.001; oF: t = −4.18; p < 0.001)

- – a given verb only has a significantly lower F0 postfocally, i.e. in the case of subject focus (sF: t = −4.45; p < 0.001), but not prefocally, i.e. in the case of object focus (oF: t = −1.57; p = 0.1173)

- – a given object is significantly lower in F0 than in the baseline (sF: t = −5.59; p < 0.001; vF: t = −5.4; p < 0.001)

4.3.2 Duration

The mean values of duration across all utterances and speakers are presented in Table 8 and tested for significance below. Item was included as a random factor in the linear mixed models because there are some slight differences in segmental structure between the different stimuli sentences.

Table 8: Means of duration of stressed syllables, differentiated by focus condition (in ms)

For prosodic focus marking by means of duration it was found that

- – a focused subject is not significantly longer than a subject in the baseline (t = –0.933; p = 0.3513)

- – a focused verb is not significantly longer than a verb in the baseline (t = 0.881; p = 0.3791)

- – a focused object is significantly shorter than an object in the baseline (t = 3.358; p < 0.001)

For givenness marking by means of duration it was found that

- – a given subject is only significantly shorter than in the baseline in the case of object focus (oF: t = −2.318; p = 0.021), not in the case of verb focus (vF: t = −1.714; p = 0.0875)

- – a given verb is significantly shorter than in the baseline (oF: t = −2.965; p = 0.0032; sF: t = −3.849; p < 0.001)

- – a given object is significantly shorter than in the baseline (sF: t = −4.349; p < 0.001; vF: t = −3.355; p < 0.001)

4.3.3 Intensity

The mean values of intensity across all utterances and speakers are presented in Table 9 and tested for significance below.

Table 9: Means of intensity of stressed syllables, differentiated by focus condition (in dB)

For prosodic focus marking by means of intensity it was found that

- – a focused subject has a significantly lower intensity than in the baseline (t = 3.33; p = 0.001)

- – a focused verb has a significantly lower intensity than in the baseline (t = 2.43; p = 0.0155)

- – a focused object has a significantly lower intensity than in the baseline (t = 2.05; p = 0.0409)

For givenness marking by means of intensity it was found that

- – a given subject also has a significantly lower intensity than in the baseline (vF: t = −3.32; p = 0.001; oF: t = –3.07; p = 0.0023)

- – a given verb has a significantly lower intensity than in the baseline (oF: t = −2.64; p = 0.0086; sF: t = –4.27; p < 0.001)

- – a given object has a significantly lower intensity than in the baseline (sF: t = −4.38; p < 0.001; vF: t = –4.93; p < 0.001)

4.4 Overall results for BlSAfE

A lack of F0 increase can be observed on focused items in contrast to speakers of WSAfE. F0 is never higher on a focused constituent as compared to its realisation in the baseline. On a focused subject, F0 is surprisingly significantly lower than in the baseline.

For F0-lowering on given constituents, the pattern is similar to the one observed in WSAfE, though the differences are by far less clear (comparing the visual displays in Figures 1 and 5 as well as the average values in Tables 1 and 7). The most striking difference lies in the absence of focus marking by F0 and the stable initial high F0 on the subject.

Concerning the realisation of duration, the duration of the stressed syllable of the verb and subject is never significantly longer in the focus condition than in the baseline. The stressed syllable of the object is even significantly shorter in focus condition than in the baseline. Given constituents are always realised significantly shorter, except for a given subject in the case of verb focus.

An unexpected finding is the significantly higher intensity in the baseline as compared to the focused condition for all constituents. As the baseline was always elicited as the first question-answer pair in all sets of stimuli sentences, this might well be due to a generally higher intensity on the first rendering of an utterance compared to the following ones. Although this does not seem to have been happening for the other groups of speakers, the intensity measures of the group of BlSAfE were not taken into further consideration.

5 Discussion

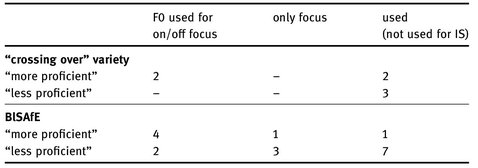

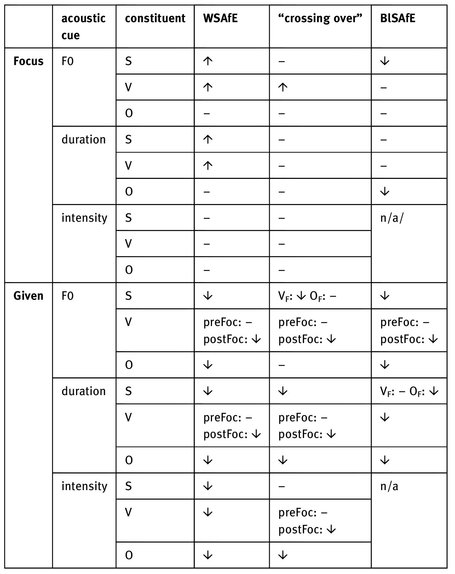

Before entering into a discussion of the results, Table 10 provides the overall results of the three groups of speakers.

Table 10: Comparison of acoustic cues used for focus and givenness in the three varieties (– = no significant difference, ↑ = significantly higher than baseline, ↓ = significantly lower than baseline)

A complex pattern of phonetic variation between the three varieties emerges from the overview in Table 10. What these results show is that all three varieties differ in their use of the three acoustic correlates of prominence. WSAfE shows similar cues as the well-described General American English (Breen et al. 2010) in using both an increase of F0 and duration on focused constituents as well as a decrease of these same parameters (and additionally intensity) for the marking of given constituents. Together, these acoustic changes amount to clearly marking the information structure of an utterance prosodically. What we see in the pattern of these speakers is what Ladd (1980: 67) refers to when he says that in English prosodic focus marking and deaccentuation can be considered “opposite sides of the same coin”.

The multilingual speakers of South African English varieties select some of the features of WSAfE and use them in specific contexts. For prosodic marking of focus, we see in the “crossing over” variety of Black speakers that only one of the acoustic correlates is selected (namely F0) and only for verb focus. Thus, we do not find any categorical use of an acoustic cue for focus. The use of a significantly lower F0 by speakers of BlSAfE in the case of subject focus and of significantly shorter duration in the case of object focus is surprising and cannot be explained in any principled way. It might be interpreted as a reflection of the fact that acoustic parameters are not manipulated in a systematic way depending on focus in this variety.

Interestingly, nearly the same pattern emerges in all three varieties for the use of the acoustic cues for given constituents. In general, F0, intensity and duration are significantly lower on given constituents. Even the different prosodic treatment of a given verb occurring prefocally and postfocally is present in the English varieties by Black speakers. Givenness marking on postfocal constituents has been analysed in two ways in the literature: As deaccentuation and as postfocal compression. The term deaccentuation refers to a deletion of pitch accents due to discourse-specific rules (Gussenhoven 2011). Consequently, if pitch accents are deleted, the resulting F0 contour should be entirely flat. This is what we see with speakers of WSAfE (Figure 1): the F0 contour does not show any sign of a pitch accent after the focused constituent in the case of subject and verb focus. However, Ladd warns that deaccenting “does not depend on anything as straightforward as ‘failure to be assigned stress’ or ‘low pitch’ ” (Ladd 1980: 57). Instead he describes that the typical case of deaccenting shows a constituent whose “level of stress” appears quite reduced (Ladd 1980: 55) and is “perceived by inferring a rhythmic structure in which the deaccented item is weaker than it would be if it were not deaccented” (Ladd 1980: 57). This makes deaccentuation comparable to postfocal compression (PFC). This term goes back to the studies by Xu (1999) on focus intonation in Mandarin Chinese and refers to a compression of F0 range and intensity of post-focus constituents. The F0 contour might still show reflexes of pitch accent albeit in a reduced range. The statistical results show a significant lowering of F0 on given constituents as compared to the baseline. (Intensity will not be considered here given that there are no reliable data for speakers of BlSAfE.) The numbers on their own do not reveal which of the two analyses is most suited to the case at hand. The visual inspection of the F0 tracks of those Black speakers who do show some marking of givenness suggests an interpretation of deaccentuation for the Black speakers of the “crossing over” variety (speaker 58, see Figure 3) because the F0 contour remains entirely flat after the focused constituent in subject and verb focus, not giving any indication of an additional pitch accent on following content words. The BlSAfE speakers who show prosodic givenness marking still seem to realise some reduced pitch accent on postfocal content words, see e.g. the F0 track of speaker 18 (Figure 6), which shows a very slight peak on the postfocal object in verb focus and a slight peak on the verb in subject focus. Such a pattern would support an analysis as postfocal compression. These observations can only serve as an initial hypothesis for further research on this issue, which is clearly needed. But it is a very interesting hypothesis as it implies that the English varieties of Black speakers might differ in givenness marking: the “crossing over” variety uses a pattern of givenness marking similar to WSAfE, the L2 variety uses a pattern where traces of pitch accents can still be seen, though reduced in range.

It is not surprising to find an absence of focus marking in the L2 variety BlSAfE. As Coulmas points out (2005: 78–79), intonation is one of the most conservative features of speech, while segmental phonetic features are more likely to change in language contact. In the case at hand, the Southern Bantu languages do not seem to mark focus and givenness prosodically (Zerbian 2007 for Northern Sotho; Swerts and Zerbian 2010 for Zulu), and hence the absence of focus marking in BlSAfE could be considered such a persisting L1 influence.59 An alternative interpretation would be that the absence of prosodic focus marking is a universal aspect of L2 speech, given that it has been found for many L2 speakers of English with different L1s (e.g. Gut 2009). Only further research on language pairings in which both languages show prosodic focus marking can provide a final answer to this question.

How does the variability observed in the prosodic patterns within the speaker groups relate to the Bantu languages of the speakers and/or their proficiency in English? As far as the Bantu languages involved are concerned, no consistent pattern emerges. Speakers of the Nguni languages (comprising Zulu and Xhosa) are among those speakers who show prosodic focus marking by means of F0 as well as among those who do not. The same holds for speakers of the Sotho-Tswana languages (comprising Sotho, Tswana, Pedi) and Tsonga. Though a more controlled study is definitely needed to carefully investigate the influence of the different Bantu languages on the prosody of English by Black speakers, the data available suggest that no phonological differences are involved. Thereby, Wissing’s (2002) observation of a lack of major differences due to the ancestral language can be extended to prosody.

Testing for proficiency in South African English, on the other hand, is not a trivial task, and the procedure used here can only give a first impression but should not be considered reliable to draw conclusions. We administered the grammar part of the Oxford Placement Test (2004 edition) excluding the questions pertaining to question tags (due to a different usage of question tags in South African English; Minow 2010: 72). Black speakers were assigned to two groups depending on their score. The threshold was set arbitrarily to 90% of correct answers. 90% or above will be referred to as “more proficient”, less than 90% as “less proficient”. The following distribution emerges:

The distribution might suggest a tendency that among those speakers who use F0 for the marking of focus are more “more proficient” speakers, and among those who do not use F0 or use F0 less are more “less proficient” speakers. However, we do not consider our test of English proficiency representative and reliable for the South African context, and therefore refrain from any conclusions concerning this issue.

What is interesting from a theoretical perspective is the phonetic marking of givenness in BlSAfE. Other English L2 varieties have been reported to lack deaccentuation (Gumperz 1982 for Indian English as cited in Ladd 2008: 232; Gut 2005 for Nigerian English; and recently Gut, Pillai and Zuraidah 2013 for Malaysian English). In addition, given that many languages of the world are reported to lack deaccentuation (see Cruttenden 2006 for an overview), it can be assumed that prosodic givenness marking is a marked feature (cf. Rasier and Hiligsmann 2007, Zerbian to appear for markedness of prosody). Marked features are difficult to acquire (Eckman 1977). Studies by Wu and Chung (2011) and by Chen, Guion-Anderson and Xu (2012) on different groups of bilingual speakers have confirmed that postfocal compression is not easily transferred from language to language. It is thus surprising to find givenness marking in the L2 variety BlSAfE. As it is a marked feature it should be difficult to acquire. The question is, though, whether the difference (which clearly emerges as statistically significant from the analysis) is phonological or solely phonetic. The interpretation for BlSAfE as postfocal compression based on the inspection of the pitch tracks already suggests that the difference might not be phonological. The smaller effect sizes suggest that differences are less salient. It also needs to be pointed out that although present phonetically, the linguistic cues used for givenness marking might not be interpreted by listeners. In Zerbian (to appear), listeners had to deduce the information-structural structure of SVO sentences uttered by speakers of WSAfE and BlSAfE in different focus conditions, solely based on the prosody of the utterances. Results show that utterances produced by speakers of BlSAfE were more often misjudged with respect to their information structure than utterances produced by speakers of WSAfE. The difference is significant and is fully in line with the production data presented in the present study. In the special case of subject focus, there was a significant difference between all three varieties, with BlSAfE again showing the highest number of cases of misjudgements. The statistical difference between the baseline and givenness marking that emerged in the current study could thus be interpreted as a mere phonetic effect. In work on focus prosody, it is suggested that focus and emphasis have much in common, not least prosodic cues. Emphasis can be considered as “an optional paralinguistic overlay to the prosodic realization, if any, of semantic focus” (Downing and Pompino-Marschall 2013: 666). By the same token, slight phonetic reduction of given material might be an optional paralinguistic overlay to the prosodic realization of givenness.

In a study on the prosodic expression of focus in modified noun phrases, Zerbian (2013) found for comparable groups of speakers of South African English that speakers of BlSAfE do not manipulate intensity and F0 on the basis of focus (duration was not considered). This result is in line with the current study which also did not find any prosodic marking of focus. For Black speakers of the “crossing over” variety, (called postacrolect SAfE in Zerbian 2013) is was found that F0 but not intensity was changed due to focus. In the present study, F0 emerged as a possible cue to prosodic focus marking only for verb focus, not in general. It needs to be noted though that Zerbian (2013) investigated the parameters within the noun phrase whereas in the present study the acoustic cues were compared to a baseline of broad focus. Also, in the present study the stimuli sentences were read out whereas Zerbian (2013) investigated semi-spontaneous speech. As already mentioned in the introduction, the two studies are a necessary complementation of each other as languages have been shown to differ in the domains of prosodic marking of information structure. Taken together, the two studies show that varieties of South African English spoken by Black speakers do not reliably mark focus prosodically, neither in the phrasal domain nor in the sentence domain. Givenness is marked within the sentence, though further research on its perception strongly suggests that it is only a slight but statistically significant phonetic difference, at least in BlSAfE.

The “crossing over” variety of Black speakers emerges as both different from the L2 variety BlSAfE as well as similar: Different in some phonetic cues used for focus marking (e.g. increased F0 on the verb when in focus; see also results in Zerbian 2013). Similar in its overall absence of systematic focus marking by prosody, at the same time showing prosodic givenness marking. However, the phonology of givenness marking might again be different across the two Black varieties, though more research is clearly needed. This answers one of the leading questions of this volume in the positive: It seems as if different constraints operate on English as a second language and a newly emerging variety. The exact mechanisms, however, are not yet clear. Given the sociolinguistic situation in South Africa and the ongoing change in the linguistic landscape (cf. Mesthrie 2010), the ”crossing over” variety cannot be considered a stable variety. Some of its present features are documented by the findings of the current study, and it will be interesting to see whether and into which direction this variety might develop. So why is it different from GenSAfE? Influence from the South African Bantu languages does not suggest itself readily as in the case of BlSAfE to explain why prosodic focus marking is largely absent, because we do not find segmental traces of the Bantu languages. It could be an extreme example for the inertness of prosody to change so that a pattern known from the local Bantu languages persists even when there are no segmental traces present in the variety. Alternatively, it could be a universal feature, possibly linked to markedness considerations (cf. Zerbian, to appear). Or, extralinguistic features could be a driving factor behind the absence of focus marking, such as the conscious or unconscious wish not to sound “too white” (cf. Rudwick 2008). Further phonetic and sociolinguistic research is necessary to find answers to these questions.

References

Bates, Douglas & Dipanwita Sarkar. 2007. lme4: linear mixed-effects models using S4 classes. (R package version 0.9975–11).

Bekker, Ian. 2009. The vowels of South African English. Potchefstroom: North-West University dissertation.

Boersma, Paul & David Weenink. 2012. Praat: Doing phonetics by computer. [Computer program]. http://www.praat.org

Breen Mara, Evelina Fedorenko, Michael Wagner & Edward Gibson. 2010. Acoustic correlates of information structure. Language and Cognitive Processes 25 (7/8/9). 1044–1098.

Chen, Ying, Susan Guion-Anderson & Yi Xu. 2012. Post-focus compression in second language Mandarin. In Qiuwu Ma, Hongwei Ding & Daniel Hirst (eds.), Proceedings of Speech Prosody 2012: 6th International Conference, Shanghai, China, May 22–25, 410–413. Shanghai: Tongji University Press.

Coulmas, Florian. 2005. Sociolinguistics: The study of speaker’s choices. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cruttenden, Alan. 2006. The de-accenting of given information: A cognitive universal? In Giuliano Bernini & Marcia L. Schwartz (eds.), Pragmatic organization of discourse in the languages of Europe, 311–355. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Da Silva, Arista B. 2008. South African English: A sociolinguistic investigation of an emerging variety. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand dissertation.

Downing, Laura J. & Bernd Pompino-Marschall. 2013. The focus prosody of Chichewa and the Stress-Focus constraint: A response to Samek-Lodovici (2005). Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 31 (3). 647–681.

Eckman, Fred. 1977. Markedness and the Contrastive Analysis Hypothesis. Language Learning 27 (2). 315–330.

Gumperz, John Joseph. 1982. Discourse strategies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gussenhoven, Carlos. 2011. Sentential prominence in English. In Marc van Oostendorp, Colin J. Ewen, Elizabeth V. Hume & Keren Rice (eds.), The Blackwell companion to phonology, 2778–2806. Malden, MA & Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Gut, Ulrike. 2005. Nigerian English prosody. English World-Wide 26 (2). 153–177.

Gut, Ulrike. 2009. Non-native speech: A corpus-based analysis of phonological and phonetic properties of L2 English and German. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Gut, Ulrike, Stefanie Pillai & Zuraidah Mohd Don. 2013. The prosodic marking of information status in Malaysian English. World Englishes 32(2). 185–197.

Hellmuth, Samantha. 2005. No de-accenting in (or of) phrases: Evidence from Arabic for cross-linguistic and cross-dialectal prosodic variation. In Sónia Frota, Marina Vigário & Maria João Freitas (eds.), Prosodies, 99–112. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Hofmeyr, Jane. 2000. The emerging school landscape in Post-Apartheid South Africa (Speech presented for the Independent Schools Association of South Africa, 30 March 2000), cited in Alan Morris, A decade of Post-Apartheid: Is the city in South Africa being remade? Safundi 5(1–2), 2004.

Krifka, Manfred. 2008. Basic notions of information structure. Acta Linguistica Hungarica 55 (3). 243–276.

Ladd, D. Robert. 1980. The structure of intonational meaning: Evidence from English. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Ladd, D. Robert. 1996. Intonational phonology, 1st edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ladd, D. Robert. 2008. Intonational phonology, 2nd edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mennen, Ineke. 2004. Bi-directional interference in the intonation of Dutch speakers of Greek. Journal of Phonetics 32 (4). 543–563.

Mesthrie, Rajend (ed.). 2008. Varieties of English 4: Africa, South and Southeast Asia. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Mesthrie, Rajend. 2010. Socio-phonetics and social change: Deracialisation of the GOOSE vowel in South African English. Journal of Sociolinguistics 14 (1). 3–33.

Minow, Verena. 2010. Variation in the grammar of Black South African English. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Rasier, Laurent & Philippe Hiligsmann. 2007. Prosodic transfer from L1 to L2: Theoretical and methodological issues. Nouveaux cahiers de linguistique francaise 28. 41–66.

Rudwick, Stephanie. 2008. Coconuts and Oreos: English-speaking Zulu people in a South African township. World Englishes 27 (1). 101–116.

Snedeker, Jesse & John Trueswell. 2003. Using prosody to avoid ambiguity: Effects of speaker awareness and referential context. Journal of Memory and Language 48. 103–130.

Swerts, Marc & Sabine Zerbian. 2010. Intonational differences between L1 and L2 English in South Africa. Phonetica 67 (3). 127–146.

van Rooy, Bertus. 2004. Black South African English: Phonology. In Edgar W. Schneider, Kate Burridge, Bernd Kortmann, Rajend Mesthrie & Clive Upton (eds.), A handbook of varieties of English. Volume 1: Phonology, 943–952. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Wilmot, Kirstin. 2014. “Coconuts” and the middle-class: Identity change and the emergence of a new prestigious English variety in South Africa. English World-Wide 35 (3). 306–337.

Wissing, Daan. 2002. Black South African English: A new English? Observations from a phonetic viewpoint. World Englishes 21 (1). 129–144.

Wu, Wing Li & Lisa Chung. 2011. Post-focus compression in English-Cantonese bilingual speakers. In Proceedings of the 17th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences, Hong Kong, China, August 17–21, 148–151.

Xu, Yi. 1999. Effects of tone and focus on the formation and alignment of f0 contours. Journal of Phonetics 27. 55–105.

Xu, Yi. 2013. ProsodyPro – A tool for large-scale systematic prosody analysis. In Proceedings of Tools and Resources for the Analysis of Speech Prosody (TRASP 2013), Aix-en-Provence. 7–10.

Xu, Yi & Ching X. Xu. 2005. Phonetic realization of focus in English declarative intonation. Journal of Phonetics 33. 159–197.

Zerbian, Sabine. 2006. Expression of information structure in the Bantu language Northern Sotho. ZAS Papers in Linguistics 45. ZAS: Berlin.

Zerbian, Sabine. 2007. Investigating prosodic focus marking in Northern Sotho. In Enoch Oladé Aboh, Katharina Hartmann & Malte Zimmermann (eds.), Focus strategies in African languages: The interaction of focus and grammar in Niger-Congo and Afro-Asiatic, 55–79. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Zerbian, Sabine. 2013. Prosodic marking of narrow focus across varieties of South African English. English World-Wide 34 (1). 26–47.

Zerbian, Sabine (to appear). Syntactic and prosodic focus in contact varieties of South African English. English World-Wide.

Zerbian, Sabine (to appear). Markedness considerations in L2 prosodic focus and givenness marking. To appear in Prosody and languages in contact: L2 acquisition, attrition, languages in multilingual situations, ed. E. Delais-Roussarie, M. Avanzi & S. Herment. Berlin: Springer.