10 English word stress in L2 andpostcolonial varieties:systematicity and variation

1 Introduction

This paper brings together empirical insights from various studies on contact varieties of English (non-native and native English varieties) in an attempt to identify unity and variation in English stress placement. There is a growing body of work on prosody in non-native (L2) English (e.g. Capliez 2011; Chun 2002; Gut 2003, 2009; Trouvain and Gut 2007) as well as in varieties of English around the world (e.g. Gut 2005; Simo Bobda 2011; Zerbian 2013). Although English word stress has by now been widely investigated in L2 acquisition (see Altmann and Kabak 2011 for a review), comparative studies on its variable realisation in different varieties of English are crucially lacking. It is widely assumed that English stress is primarily lexical (cf. Giegerich 1992; Roach 2009) and that the placement of stress in L2 and postcolonial varieties can be prone to L1 effects (e.g. Altmann 2006; Kijak 2009). To that end, English word level stress constitutes an instructive research venue from both a theoretical and an empirical perspective since different encounters with such a notoriously complex word prosodic system may nevertheless exhibit recurrent patterns that are reflective of universal as well as specifically English-based acquisition-driven processes.

The primary aim of this paper is to understand unity and variation in English stress assignment by investigating an array of different L1s as well as different contact and learning situations, namely English as a Second Language (ESL), English as a Foreign Language (EFL), and postcolonial varieties of English. After a brief introduction to the facts of English stress and its variability, we will bring together three sorts of studies to pinpoint endogenous (timeless laws of phonetics and phonology, as well as English-specific variables) and exogenous (user-specific variables such as his or her L1 and level of proficiency) factors that predict systematicity and variation. In particular, we will report on a study on the production of stress in English nonce words by highly advanced ESL speakers with different L1s in the USA, and compare that with stress placement

Heidi Altmann, University of Stuttgart

Barış Kabak, University of Würzburg

in real English words by highly advanced EFL speakers in Germany. Finally, we will embed the observations from these experimental studies in the context of previous descriptions of stress placement in English postcolonial varieties, namely Cameroon and Nigerian English, to arrive at broader generalisations of the nature and dynamics of stress in Englishes and to explicate some potential factors in the genesis of non-convergence between standard varieties and postcolonial varieties in stress assignment.

2 English stress: Facts and findings fromnon-native speakers

This section presents some well-known facts of word-level stress in Standard Englishes at the interfaces between phonology, morphology and lexicon. Our primary aim here is one of description. As such, we do not evaluate existing theories of English stress, nor do we provide a new account. We also review a number of recent studies on the L2 acquisition and processing of English stress to explore systematicity and variation in non-native encounters with English stress and lay the ground for our experimental studies.

2.1 Facts: Systematicity and variability in English stress

Every learner of English has most likely struggled with stress assignment in English at some point in the learning process. While there are some regular patterns or tendencies, numerous exceptions can be identified for each of them, reflecting the complex diachronic development of the English language (e.g. Fikkert, Dresher and Lahiri 2006; Dresher and Lahiri 2005; Fournier 2007). What is generally accepted by now is that the position of primary stress in an English lexical word depends on different factors such as word class, syllabic structure or morphological composition. These, of course, come in addition to cases where stress simply has to be specified lexically.

Purely phonological accounts of English stress focus on the importance of syllable weight: In monomorphemic words, stress is assumed to usually fall on the penultimate syllable (i.e. the second syllable from the end) if it is heavy; if it is light, the preceding (antepenultimate) syllable is stressed (Chomsky and Halle 1968; Hayes 1982; Giegerich 1992).40 While this generalisation holds for most nouns, there are, however, quite a number of verb/noun or adjective/noun pairs that can be distinguished based on the position of stress. In such disyllabic pairs, nouns are stressed on the penultimate syllable and the corresponding verbs or adjectives on the final syllable (e.g. ˈsuspect (n.) vs. susˈpect (v.), ˈpermit (n.) vs. perˈmit (v.), ˈcontent (n.) vs. conˈtent (adj.)), suggesting that word class, a non-phonological construct, exerts an influence on stress placement in English and that primary stress in monomorphemic words will fall on one of the last three syllables. Another non-phonological factor influencing stress placement is morphological complexity, whereby regularities based on word class are additionally subject to the prosodic demands of inflectional and derivational morphemes (e.g. Kingdon 1958). For example, it is well known that some derivational suffixes cause stress to either shift further to the right within the stem (stress-shifting suffixes) or pull stress onto themselves (stress-attracting suffixes) (see Giegerich 1992 and Yavaş 2011 for textbook treatments). Examples for stress-attracting suffixes would be –ese or –ee as in Portuˈguese (cf. ˈPortugal), examiˈnee (cf. eˈxamine), for stress-shifting suffixes –al (e.g. poˈlitical, cf. ˈpolitics), –ify (e.g. soˈlidify, cf. ˈsolid) or –iary (beneˈficiary, cf. ˈbenefit).

For most of the general patterns described above, however, exceptional cases can be cited. These make the actual system much less predictable and more idiosyncratic. For example, there are many verbs and adjectives that are stressed on the first syllable (e.g. ˈborrow, ˈdifficult). Furthermore, there are several disyllabic nouns that are stressed on the final syllable (e.g., balˈloon, hoˈtel, caˈnoe, Juˈly, desˈsert), as well as those with final secondary stress (e.g., ˈsynˌtax, ˈraˌdar). Despite a heavy penultimate syllable, nouns such as ˈcalendar and ˈcolander (cf. coriˈander) must also be treated as exceptions to the English stress rule given above. One can even find (albeit rare) cases of words with primary stress on the pre-antepenultimate syllable (and even secondary stress on the final syllable) in the English lexicon (e.g. ˈcatamaˌran, ˈcaricaˌture), which violate the supposed three-syllable window from the right word edge for primary stress. Finally, there is considerable variation among Standard Englishes with respect to the placement of primary as well as secondary stress (e.g. General American: beˈret vs. Received Pronunciation: ˈberet; General American: ˈsecreˌtary vs. Received Pronunciation: ˈsecretary; see Tottie 2002 for further examples).

2.2 Non-native encounters: Acquiring and processingEnglish stress

The empirical investigation of the non-native production of word stress is a relatively young discipline in linguistic research. For a long time, segmental issues had been considered much more central to non-native speech and became the impetus behind the development of influential L2 speech models (e.g. Best’s [1995] Perceptual Assimilation Model; Flege’s [1995] Speech Learning Model) albeit without explicit predictions for the development of L2 prosody. Nevertheless, the importance of stress in non-native speech has long been acknowledged in the literature such that incorrect stress placement alone may lead to miscommunication (e.g. Hubicka 1980). For instance, Benrabah (1997: 163) propagates that “its importance as a clue to word-recognition in listening to speech makes it a ‘high-priority’ in language teaching”. Strikingly, though, word stress is excluded from Jenkins’ (2000) list of features of the Lingua Franca Core – i.e. those features that should be focused on in teaching English as a foreign language (EFL). However, given the fact that stress can be used as a cue in speech perception by English native speakers (e.g. Cutler 1984), and that misassigned primary stress in English has been shown to influence comprehensibility and intelligibility (Hahn 2004), Jenkins’ observation that English lexical stress, as well as individual vowel quality (which constitutes yet another cue for word stress in English), do not matter in EFL interactions as they do not lead to unintelligibility (see Deterding 2011 for a review) remains questionable.

Research on L2 stress has revealed what is also commonly found in other areas of L2 development: A prevalent cross-language transfer effect, on the one hand, and unique interlanguage patterns on the other. In particular, L2 learners have been shown to stress English words in accordance with strategies from their native language (Archibald 1992), or to produce some kind of default pattern that corresponds to neither their L1 nor the target language prosodic system (Archibald 1997; Pater 1997). The application of L1 strategies naturally hints at learners’ direct transfer of properties of the language they are familiar with to the less familiar language. Such a transfer presumably would not indicate an active involvement of a newly created prosodic system for the L2, at least on the surface. For example, Hungarian learners, who tend to place stress in English words at their left-edge, might be influenced by the regular Hungarian pattern of word stress on the initial syllable (Archibald 1992).

In the vast majority of stress production studies, however, learners were found to produce stress patterns that did not correspond to the ones in their L1 or in their L2, especially if they were required to produce English nonce words. These patterns might be due to novel strategies invented by learners or non-target like (i.e. non-converging) application of existing strategies in English. The French learners of English in the study by Pater (1997) are exemplary for the application of a unique non-converging learner pattern since they consistently stressed the leftmost (heavy) syllable, which is unlike any English native strategy and also unlike the French L1 pattern. In contrast, Guion, Harada and Clark (2004) found Spanish L2 learners to rely on the same factors for stress assignment as native speakers of English (analogy to known words, syllabic structure, lexical class), albeit not to the same extent or in the same relative distribution.

Albeit with some delay, the perceptual aspects of L2 stress have also received some attention. In particular, robust effects of one’s native language on the ability to perceive stress location or stress differences in words have been repeatedly shown in the psycholinguistic literature. For instance, French listeners, whose L1 has no lexically contrastive stress, were shown to exhibit difficulties with encoding stress contrasts (Dupoux, Peperkamp and Gallés 2001; Dupoux et al. 1997, 2008). “Stress deafness”, as Dupoux and colleagues termed this “impairment”, emerges only in tasks that tap phonological representations of stress. As such, the language-specific modulation of stress sensitivity stems from processing stress at an abstract phonological level rather than at a psycho-acoustic level (see Domahs et al. 2012; Schwab and Llisterri 2011). This suggests that at lower levels of processing, the phonetic differences may be discriminated and used by listeners, yet they may have difficulties with encoding stress in lexical representations. 41 Learner internal factors that have so far been identified as influencing the relative success in stress perception were the degree of predictability of stress position in the L1 (Altmann 2006; Peperkamp and Dupoux 2002), the presence or absence of lexical stress in the L1 (Altmann 2006 for English as L2), or the functional load of word stress in the L1 (Kijak 2009 for Polish as L2).

3 Case studies

In order to get a better understanding of how variation and systematicity manifest themselves in English stress assignment, we will now take a closer look at specific case studies on English stress placement in three distinct learning/ contact situations: learners residing in an English-speaking country and those residing in their home country, referred to here as ESL and EFL learners respectively, and a postcolonial variety of English, namely Cameroon/Nigerian English. While the EFL study tests the learners’ metalinguistic knowledge of stress patterns in the perception of existing English words by highly proficient German university students of English, both the ESL study and the observations from Cameroon/ Nigerian English refer to English stress assignment in production. An evaluation of the findings from perception and production studies as well as from different contact situations enables us to identify potentially similar strategies across different modalities and learning scenarios, thus yielding a more comprehensive overview of variation and systematicity in English stress assignment throughout distinct linguistic contexts.

3.1 Stress production in highly proficient ESL users

The first case study we report here concerns highly advanced non-native speakers of English who had been studying and residing in the USA for at least six months at the point of time of data collection. We investigated which strategies these learners might use to assign stress to words that they have never come across in the second language. It seems clear that there are different strategies available (cf. section 2.2), however, what is of interest in this context is to what extent English stress patterns differ across the different L1 groups. The data we discuss below were first reported in Altmann (2006), which we will re-analyse in the context of the central research questions raised in this paper.

Participants

A total of 80 university students from the University of Delaware participated in this study. Ten of them were native speakers of American English, all undergraduate students enrolled in introductory linguistics courses. The remaining participants were recruited from the international student community at the University of Delaware, all highly advanced learners as measured by standardised proficiency tests (Test of Spoken English and Michigan English Test) and speakers of a standard variety of their native language. In particular, there were 7 different non-native L1 groups with 10 participants each: Arabic, Turkish, French (all of them are languages with regular/ predictable word stress), Spanish (a language with primarily lexical stress), Japanese, Korean, and Chinese (all of them are pitch-accent or tone languages with no word-level stress).

Methodology

Forty-six nonce words were presented to the participants in orthographic form on a printed list in a pseudo-randomised order. Each word was broken down into its individual syllables, separated from each other by a dot (•) for easier reading. The nonce words were created based on the following criteria: (1) only open CV syllables were used, (2) each word was intended to contain at least one stressable (i.e. not schwa) vowel, which in the current case was restricted to a long/tense vowel or diphthong (indicated by double letters in orthography, e.g. <ee> or <oa>), (3) no more than two stressable syllables should be adjacent, conforming to the English rhythm rules (cf. Liberman and Prince 1977), and (4) no syllable corresponded to any existing English word. Application of these criteria yielded three different structures of words with two syllables (5 tokens per structure = 15 tokens in total, e.g. noo•dee), four different structures of words with three syllables (4 tokens per structure = 16 tokens in total, e.g. sa•foa•na), and 5 different structures of words with four syllables (3 tokens per structure = 15 tokens in total, e.g. ma•ley•da•zee).42

The task of the participants was to read each word out loud twice. Prior to the study, all participants were instructed that the nonce words are potential words of English and practiced the production task with a number of real and nonce words. In the main task, only the second production was used for analysis since this allowed the speakers to monitor and improve on their first reading in case it did not ‘sound good’ to them. The second recordings were transcribed and analysed with respect to the location of stress, which were determined by two phonetically trained (near-)native speakers of American English who listened to all the items. Inter-transcriber reliability was very high (90%) and cases of disagreement were discussed until a consensus was reached. If participants provided structures that were unintended but fell into some other structural type, these were grouped with the respective applicable alternative structure; where this was not possible, the item had to be excluded from analysis. This naturally resulted in unequal numbers of actual productions for each category and language group. Below we will only offer a qualitative analysis of the data to reach a holistic understanding of the patterns that emerged in each L1 and how those patterns compare to other L1s’ preferred stress location overall.

Results

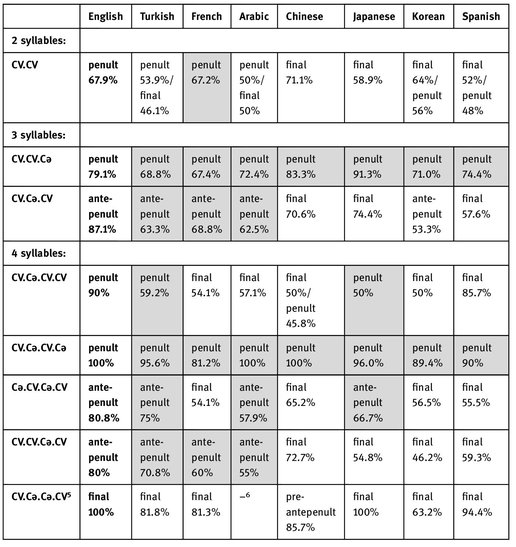

Table 1 presents the preferred stress position across words of different lengths for each structure that contained at least two potential positions of primary stress, which means that structures with only one full vowel are not included in the analysis since this would not involve speakers’ choices for or against a certain stress position due to the existence of only one potentially stressable vowel in a word. It also provides the percentage of how often each pattern was provided overall by the speakers of the respective L1 group. In cases where there were two options within 10% of occurrence, both choices are listed. It should be noted that in words with three full vowels, a score of 50% may still yield a difference of more than 10% from either of the other two possible stress positions.

As can be seen in Table 1, Turkish (6/7), French (5/7), Arabic (5/7) and Japanese (4/7) speakers produced most structures in agreement with the English native speakers’ stress patterns. English native speakers overwhelmingly preferred to stress the rightmost non-final stressable syllable, i.e., the penult if this contained a full vowel or otherwise the antepenult, a finding that has recently been confirmed by Domahs, Plag and Carroll (2014) as well. Strikingly, only four English participants actually produced the pattern CV.Cə.Cə.CV (with final primary stress placement), yielding a total of merely six tokens out of a possible total of thirty; all other English native speakers instead delivered pronunciations with differing structures for items of this type, changing one of the intended schwas into stressed tense vowels (which were subsequently counted towards those respective structural types in the current analysis) or into stressed lax vowels (making the following onset consonant ambisyllabic; these structures had to be discarded since they did not correspond to any of the structural types in our investigation). Thus, for example, the item goo•ve•ra•dee was pronounced (unchanged) as [guːvərəˈdiː], or (changed) as [gʊˈvɛrədiː] or [guːvə ˈrʌdiː]. Native speakers’ difficulty with this structure can be explained by the theoretical existence of a “three syllable window” from the right edge that is regularly available for English primary stress (see Domahs et al. 2014 for a CELEX analysis), which means that almost all English real words have primary stress on one of the three last syllables (cf. section 2.1.). Since in the case of CV. Cə.Cə.CV both the penultimate and antepenultimate syllables contain schwas, and the final syllable is obviously not the preferred position for stress by native speakers, this would only leave the pre-antepenult as the last potential target here. No English participant, however, produced primary stress on this syllable; instead the majority opted for deviating pronunciations that contained a different (stressable) vowel type in the penult or antepenult syllable, their preferred positions for primary stress. A few speakers did obey the intenoverwhelmingly preferred to stressded structure and had to resort to final stress for these words, as illustrated in the example above, which, however, does not provide a solid basis for a group wise comparison of stress placement for this type of words with the other L1s.

Table 1: Most preferred position of primary stress for nonce words by language (shaded cells indicate clear agreement43, 44, 45 with the English native group)

Considering the variable performance of the different L1 groups, the question arises as to why the Turkish, French, Arabic groups as well as the Japanese group showed most convergence with the native speaker population. Can this be due to the transfer of L1 prosody (e.g. employing similar stress patterns or experience with word-level lexical prominence)? Since stress placement in Arabic would yield the same stress patterns as those by the English group, we cannot be certain as to whether these learners applied L1 strategies or English-specific strategies. However, it was also the case that both the Turkish and the French participants displayed similar, target-like strategies for stress assignment for the vast majority of nonce word structures, which cannot be due to an L1-induced pattern. In the few cases where they showed divergence, however, the L1 strategy of making the final syllable prominent surfaced (both Turkish and French have regular stress on the final syllable; see Kabak and Vogel 2001 for Turkish; Dell 1985 for French). As for the Japanese learners, although they do not fully cohere typologically with the three rather “target-like” groups discussed above, their convergence with English native speakers can be due to the word-level prosody of Japanese, where pitch-accent arguably brings about a specific locus of prominence within a word, which is lexical. However, the fact that Spanish speakers, whose L1 also employs a lexical stress system, did not show target-like behavior is not consistent with an explanation based on the potential positive influence of Japanese prosody. Altogether then, it is not possible to postulate a purely L1-based account of convergence in L2 stress production in this study. Similarly, L1 influence also does not explain the cases of non-convergence, which we turn to below.

The remaining L2 groups only showed agreement with the target population if there was a schwa in the final syllable, which then necessarily had to lead to penultimate stress. What is striking, however, is the surprising overlap that can be found across the non-converging stress patterns: almost all of them are due to placing word stress on the final syllable. Since Chinese and Korean are both non-stress languages, this cannot be based on L1 strategies. It rather reflects some linear interlanguage strategy, whereby the learners put word-level prominence on the last syllable that can bear it. Thus, there were some common approaches for non-converging patterns that could be identified in all L2 groups: (i) the most prominent syllable was pushed towards the right edge (as opposed to the beginning of the word), and (ii) final stress was not an option in the case of schwa syllables. These approaches suggest that all learners had some sensitivity to the rhythmic structure of English. However, this prosodic knowledge did not always produce patterns that converge with those of the English native speakers since prominence was pushed too far to the right, thus ignoring the exceptional character that the final syllable obviously has for native speakers of English. It can therefore be considered a unique learner strategy since the most frequent position for stress in English lexical words is the penultimate or antepenultimate syllable and final stress is statistically not a common position in the native English lexicon in general (cf. Clopper 2002).

A somewhat mixed performance was that of the Spanish group, which patterned more with the non-stress languages for most structures. In the absence of orthographical marking, stress in Spanish would generally fall on the penultimate syllable, which is not observed in the data at hand: in cases where the final and the penultimate syllable contained a full vowel, the Spanish learners favoured the final syllable, which agrees with neither their L1 nor the L2. As such, Spanish learners’ English stress assignment strategies can be taken to yield a unique learner pattern, apparently the same one that the other non-converging L1 groups (i.e. those with no word stress in the L1) applied.

What can be concluded from these L2 production data is that highly proficient ESL learners often did not provide the same stress patterns as native English speakers. However, there was systematicity in the non-converging structures since they followed the same basic generalisation that was employed consistently by groups of learners from different L1s, i.e. placing primary stress on the final syllable, a pattern that was neither L1- nor L2-induced.

3.2 Stress identification in highly proficient EFL users

The point of departure in the second study was our longtime personal observations on incorrect stress realisations of some contextually-familiar English words (i.e. those used frequently in academic language) by German university students who persistently produce them with penultimate stress such as hypothesis (as [haɪpɔˈθi:sɪs]), and variable (as [vəˈɹaɪəbl]). Given the fact that German has lexical stress, such incorrect renderings of stress are unlikely to stem from a perceptual difficulty, or a general difficulty to store stress contrasts at the word-level, as discussed above. In particular, we investigated to what extent highly proficient L2 learners of English are able to correctly identify stressed syllables in such “problem” words upon carefully focusing on their respective stress patterns, and how confident and consistent they are in their identification.

Participants

Twenty-seven university students (23 female) with German as their L1 participated in the study in 2012. All were studying English either as their primary or secondary major at the University of Würzburg in Germany, and were participating in an advanced-level seminar on Second Language Phonology and Foreign Accent in the English Linguistics department at the time of testing (the experiment was conducted in the last session of the seminar). As such, they had explicit knowledge about English phonetics and phonology as well as empirical background in L2 phonology and foreign accent.

Methodology

The participants were asked to carefully listen to the pronunciation of 30 polysyllabic English words (see Appendix 2) presented in random order by means of two loudspeakers at a comfortable volume, and pay specific attention to word stress in two consecutive tests.46 The items were recorded by a phonetically trained near-native speaker of English (the first author), who modeled her pronunciation after the pronunciation given for General American English in the English Pronouncing Dictionary (Jones 2006). After having heard all the words, the participants were told to turn over the response sheet given to them, which listed in random order all the words that they had heard in the recording. For each word, they were instructed to mark the syllable with the strongest stress. Next, they were asked to indicate, again for each word, how confident they were in their stress judgement using a Likert scale from 1 to 5 (1: no confidence, 5: very high confidence). Additionally, they were requested to come up with at least one word that is phonologically similar to each word on the list. The primary aim of this sub-task was to increase their sensitivity to the phonological properties of the words, segmentally and suprasegmentally, the results of which we will not report here. There were 5 different response sheets, all containing the same items albeit in a different order to control for any order effects, and they were assigned to the participants in a consecutive order (Subject 1-List 1; Subject 2-List 2; . . . Subject 6-List 1, and so on). The participants were given 10 minutes to finish the task (Test 1). After a short break, they were asked to listen to the same 26 words again and do the same task (i.e. marking the primary stress and indicating their confidence level for each word) on a second response sheet that they received (Test 2). The items on the second response sheet had a different order than the ones on the first response sheet. They again had 10 minutes to finish the task. Finally, they were given a background questionnaire which requested, among others, information about their age, how important it is for them to have a native-like accent and to be fluent in English (5: Very Important, 4: Important, 3: Moderately Important, 2: Of Little Importance, 1: Unimportant) as well as a self-evaluation of their English skills in speaking, comprehension and writing (5: Very Good, 4: Good, 3: Acceptable, 2: Poor, 1: Very Poor). As expected, the participants reported to be highly motivated to be fluent in English and to have a near-native accent. Table 2 summarises the participants’ responses.

Results

A total of 1620 responses were obtained from the two tests. For each test, we analysed the number of incorrect stress assignments as well as the confidence level given to each incorrect response. Here we focus only on overall error patterns, without going into error analyses for each word or participant. The error rate was 11.5% for Test 1 and 7% for Test 2, indicating that the participants’ stress judgements became more reliable after an additional listening session. The generally low error rates may not be surprising given that, first of all, the participants were trained in English phonology and second language acquisition, and perhaps more crucially, that the task demanded explicit attention to stress. However, given the favorable conditions for monitoring and increased metalinguistic awareness, the existence of errors is instructive to understand the pervasiveness of stress difficulties in an L2. Furthermore, errors could not completely be eradicated in Test 2 although the participants heard the words again, suggesting a level of fossilisation in the lexical representation of stress.

| Syllable | % Errors in Test 1 (n=84) | % Errors in Test 2 (n=51) |

|---|---|---|

| initial | 29% (24) | 39% (20) |

| antepenult | 2% (2) | 10% (5) |

| penult | 60% (50) | 45% (23) |

| final | 9% (8) | 6% (3) |

The great majority of errors (90% in Test 1, and 88% in Test 2) came from words with three or more syllables. Of these polysyllabic words with diverging stress position, the majority of errors in both tests was due to the placement of stress on the penultimate syllable. The word that turned out to be most problematic was parenthesis, to which 63% of the participants responded with an incorrect stress pattern in Test 1. The great majority of these erroneous responses involved penultimate stress (83%). The second most problematic word was variable, which was marked incorrectly by 44% of the participants, all with antepenultimate stress. This was followed by reviewed (30 %) with initial stress. Among those who incorrectly responded to parenthesis and reviewed, the great majority could correct themselves in Test 2 (83% and 63% respectively). However, the erroneous stress pattern of variable was the most pertinacious: Only 33% of the participants could correct the stress pattern in Test 2. Another uniform pattern that emerged in the study involved calendar in Test 1, where all the erroneous answers (22% of all responses) involved penultimate stress; all were corrected, however, in Test 2. Table 3 summarises the distribution of errors to syllable positions in words with three or more syllables in Test 1 and Test 2.

Although the number of errors in Test 2 was considerably lower in comparison to Test 1, 72% of these were due to the repetition of the same erroneous stress pattern as the first time around. The remainder was due to new errors (i.e. items that were correctly marked in Test 1, but incorrectly marked in Test 2). Interestingly, 65% of the new errors involved initial stress. Altogether then the results show that the prevalent target positions for non–converging stress placement in polysyllabic words for German speakers are penultimate or initial syllables.

Concerning the confidence scores assigned to the erroneously marked words, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests with Holm-Bonferroni sequential correction reveal that there is a significant increase in the participants’ confidence levels from Test 1 to Test 2 when the errors are corrected in Test 2 (x = 3.02 vs. 3.94, Z = –4.014, p < 0.001). However, this was also the case when the participants committed the same error (3.23 vs. 3.83, Z = –2.888, p = 0.008), as well as when they made additional errors (3.44 vs. 4.13, Z = –2.230, p = 0.03).

In sum, this study shows that stress errors can be impervious to correction even for highly advanced L2 learners of English who have explicit knowledge about English stress and who are given an opportunity to monitor stress placement. The preponderance of initial and penultimate stress in non-convergence is on a par with some of the observations made in the production study with ESL speakers (see 3.1.) above: Learners were found to employ some unique strategy that native speakers would not (e.g. final stress in the ESL study, initial (i.e. pre-antepenultimate) stress in the EFL study). In addition, they also followed and generalised target-like strategies, as illustrated by the converging preference for a penultimate stress pattern in polysyllabic words, which however led to errors in the case of the EFL study only due to the lexical, exceptional nature of stress placement in some English words (e.g. analysis, hypothesis, phenomenon). An alternative explanation for some errors may be that these words exist as cognates in German, where they have penultimate stress.

3.3 Stress assignment in postcolonial varieties of English:Cameroon/Nigerian English

The lexicon of postcolonial varieties of English often illustrates stress placement that differs from that of the Standard Englishes (i.e. Received Pronunciation and General American). Once one steps away from a prescriptive comparison with the heritage language and considers these varieties as independent grammatical systems in their own right, it becomes obvious that they follow their own patterns and regularities. These patterns may originate from a more systematic application of stress patterns present in the “old Englishes”, they may, however, also be genuine innovations. In the following, we will take a closer look at the stress systems of Cameroon/Nigerian English to support the notion that deviation from standard norms should rather be seen as variation, which in turn should motivate researchers to get a better understanding of a potential system behind this variation.

As convincingly argued by Simo Bobda (1995, 2008, 2010), Cameroon and Nigerian English (as opposed to the “old English” targeted in institutional settings in these countries) can be subsumed under one common denominator regarding lexical stress in both varieties. Based on a reanalysis of an array of existing data (frequency counts as well as original experimental data), Simo Bobda (2010) provides an insightful account of stress placement in these varieties as being widely regular with respect to a number of relatively simple and transparent strategies, some of which will be presented in the following.

Many stress placement strategies in these new English varieties are incorporated from Standard Englishes (i.e. RP and GA)47, but more regularly applied, as exemplified in the following select examples. In disyllabic Cameroon/Nigerian English verb-noun pairs, for instance, the position of stress alternates just like it often does for such words in Standard English (i.e. initial stress on nouns, final stress on verbs: ˈsuspect (N) vs. susˈpect (V)), however, it is applied more systematically to nouns in the new varieties. This is evidenced in generally regular initial stress for disyllabic nouns e.g. ˈadvice, ˈextent or ˈsuccess, compared to Standard English adˈvic/se (V/N) or sucˈcess (N). Furthermore, syllable weight as a phonological factor also strongly affects stress placement, just like in Standard English, but to a larger extent, avoiding many exceptions that exist in RP or GA. This can be exemplified by words like multiˈply, reaˈlise, anˈnex or caˈlendar in Cameroon/Nigerian English (which are non-rhotic). In addition, the stress property of affixes is more streamlined than it is in Standard English, for example, the suffix -ly is consistently stress-neutral in these new varieties (ˈmilitari+ly, ˈnecessari+ly, ˈprimari+ly) but not always in Standard English (miliˈtari+ly, necesˈsari+ly, priˈmari+ly).

Cameroon/Nigerian English stress placement, however, also involves strategies that can be considered truly innovative. One such innovation is that the presence of a certain vowel or consonant in a final syllable rhyme may exert an effect on stress placement – a strategy that has no parallel in RP or GA, where the specific segmental content of a syllable (as opposed to its internal structure) has no such relevance. For instance, high front vowels in the final rhyme attract stress on this syllable. This tendency can be found for (especially female) first names, e.g. Juˈdy, Doˈris, for nationalities, e.g. Iraˈqi, Somaˈli, for prefixes, e.g. cenˈti+grade, poˈly+syllable, miˈni+skirt, but also for simple nouns such as bis ˈcuit, tenˈnis or speˈcies. In addition, there is a second stress placement strategy linked to segmental content which yields stress on final syllables ending in an alveolar nasal for (again especially female) first names, e.g. Eveˈlyn, Suˈsan.48 Another segmental strategy resulting in final stress can be found for verbs beyond two syllables length with final obstruents, e.g. embarˈrass, interˈpret.

As illustrated by the select phenomena above, stress placement in Cameroon/ Nigerian English often differs from that in Standard English. This, however, does not mean that speakers of these new varieties fail at approaching a certain target form but rather that they apply their own strategies that are not necessarily identical with the ones in the traditional standard varieties. Such strategies could even involve genuine original innovations of the new Englishes, in addition to a more general extension or simplification of existing strategies in the old Standard Englishes, as in the case of prevalent word-initial stress in disyllabic nouns. As such, what appear to be inconsistencies may stem from an interaction of conflicting patterns, as illustrated by words with the suffix –ism, which is pre-stressing in Cameroon/Nigerian English (materiˈalism, coloniˈalism), and thus does not yield final stress despite the presence of a high front vowel.

4 Discussion and conclusions

Comparing the findings of the three case studies and scenarios, the following picture emerges: Word stress can pervasively diverge from normative standards even among those who actively use the language on a daily basis, and, interestingly, even among trained learners who strive for native-like pronunciation. Furthermore, non-native English stress patterns that emerge across different L1 backgrounds may, on the one hand, show uniformity in certain aspects (e.g. preferring a relatively fixed location for stress placement), but may, on the other hand, result from unique learner-internal strategies that are neither L1- nor L2-induced (e.g. segmental content of final rhyme).

Across the different varieties in our database, we find a considerable amount of within- and across-group variation with some clear default patterns, which could be either converging with or diverging from the Standard English pattern, with only marginal modulation by the L1 of the speaker (e.g. in the case of cognates). We will unpack each of these factors below and discuss their implications in the context of previous observations and findings.

First, in all three studies presented above, learners apply regularisation strategies that comply with core prosodic properties of English (e.g. weight sensitivity, three syllable window, penult or antepenult preference) but may also overgeneralise across the learned lexicon. More specifically, converging patterns show a preponderance of penultimate stress placement, followed by antepenultimate stress depending on syllabic structure. Along these lines, van Rooy (2002) makes use of roughly the same principles, albeit expressed by ranked constraints, in order to account for stress patterns in Tswana English (a variety of Black South African English). In particular, stress in Tswana English is right-aligned to the word, avoiding however the final syllable unless it is superheavy, culminating in the above mentioned core properties of English. More specifically, in van Rooy’s Optimality Theoretic account, the ranking SUPERHEAVY >> NONFIN(ALITY) >> ALIGN-R(IGHT) ensures that penultimate syllables attract stress, with superheavy final syllables still being able to receive stress. The interplay of these constraints with the correspondence constraint OUTPUT-OUTPUT IDENT(STRESS) accounts for the fact that certain suffixes may require stress to appear on antepenultimate syllables.49

Second, there were patterns that converged neither with the L1 of the speaker nor with the target language. The above mentioned stress-attracting segmental composition of certain final syllables in Cameroon/Nigerian English (e.g. the presence of high vowels) constitute one such innovative factor, which parallels Tswana English speakers’ tendency to stress the final syllable if it is superheavy (van Rooy 2002). Likewise, we saw a preponderance of non-target-like final stresses in the ESL study, which can be considered an extension of the strategy found in Tswana English since this also applied to CV syllables and not only to superheavy ones.

Third, we have seen cognate effects insofar as the stress patterns of the highly proficient German speakers of English are concerned. This is not surprising given that, first of all, real words were used in our EFL study and, secondly, English and German share a considerable number of cognates. This is on a par with Flege and Bohn’s (1989) findings, where Spanish L2 speakers of English residing in the USA (mean LOR = 2.3 years) resembled English native speakers more closely in producing the stress alternation in able-ability (in terms of stress location, duration and intensity differences between the unstressed and stressed syllables) than in pairs like satan-satanic, where there was a greater between-and within-group differences. The authors speculated that Spanish speakers relied on the stress pattern of the Spanish cognate Satan (with final syllable stress), leading to “smaller average duration and intensity ratios for the Spanish than English speakers in the first vowels in Satan and satanic” (Flege and Bohn 1989: 57). Similarly, the non-convergence between the Spanish and English speakers in the production of the pair apply-application was also attributed to a cognate effect. While it is not possible to tease apart the role of word familiarity from cognate effects in Flege and Bohn’s (1989) study, it would be highly plausible that L2 learners acquire stress alternations on a word-by-word basis and resort to an L1-based strategy where lexical representations in the L2 are not intact. Coupled with our results, where we additionally see both rule-governed (albeit overgeneralised) and lexical effects, it would not be too far-fetched to suggest that English stress assignment, both in old varieties as well as the ones we discussed here, is a by-product of both static, stored, lexicalised patterns as well as more rule-based, computable ones.

Finally, highly advanced L2 speakers also exhibit intra-speaker variability or fossilised stress representations that are impervious to correction even under high-monitor settings, which we take to be reminiscent of how non-convergence has possibly originally emerged in postcolonial varieties. Especially since correction or possibilities to model one’s pronunciation after speakers of old varieties were less likely in postcolonial varieties given the ecology and special sociolinguistic dynamics of language contact situations, learner-initiated generalisations that diverge from standards were prone to eventually become static.

In conclusion, the comparison of three different L2 English scenarios allowed us to shed some light on what kinds of general properties English language users are able to extract regarding stress assignment in English and how much they might add to the newly emerging system independently. Word stress in World Englishes is likely to become more fixed and predictable given well known laws of simplification and regularisation in language change and contact. This is perhaps inevitable especially given that there are instances of regularisation even in old English varieties. For example, a preference for initial stress in Southern American English as well as African American English for words that are standardly stressed on other syllables (e.g. July, police, TV, insurance etc.) has been widely noted (see Kretzschmar 2008: 49; Baugh 1983: 62–64). If word stress is an evanescent feature in lexical representations and a less salient marker of linguistic identity than for instance vowels and consonants, linguistic leveling within varieties and dialect leveling across varieties (especially given increasing globalisation) might make word prosody more similar across paradigms in the lexicon. The unifying English word stress patterns in the varieties we examined here can be taken as indications of an incipient change that may eventually eradicate complexities and exceptions in word prosody.

References

Altmann, Heidi. 2006. The perception and production of second language stress: A cross-linguistic experimental study. Newark, DE: University of Delaware dissertation. http://ifla.uni-stuttgart.de/files/altmann-dissertation.pdf (accessed 07 March 2014)

Altmann Heidi & Barış Kabak. 2011. Second language phonology. In Nancy C. Kula, Bert Botma & Kuniya Nasukawa (eds.), The Continuum companion to phonology, 298–319. London/ New York: Continuum.

Archibald, John. 1992. Transfer of L1 parameter settings: Some empirical evidence from Polish metrics. Canadian Journal of Linguistics 37. 301–339.

Archibald, John. 1997. The acquisition of English stress by speakers of nonaccentual languages: Lexical storage versus computation of stress. Linguistics 35(1). 167–181.

Baugh, John. 1983. Black street speech: Its history, structure and survival. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Benrabah, Mohamed. 1997. Word-stress: A source of unintelligibility in English. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching 35(3). 157–165.

Best, Catherine T. 1995. A direct realist view of cross-language speech perception. In Winifred Strange (ed.), Speech perception and linguistic experience: Issues in cross-language research, 171–204. Timonium, MD: York Press.

Capliez, Marc. 2011. Experimental research into the acquisition of English rhythm and prosody by French learners. Lille, France: Université de Lille dissertation.

Chomsky, Noam & Morris Halle. 1968. The sound pattern of English. New York: Harper & Row.

Chun, Dorothy M. 2002. Discourse intonation in L2: From theory and research to practice. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Clopper, Cynthia G. 2002. Frequency of stress patterns in English: A computational analysis. Indiana University Linguistics Club Working Papers 2 (1). https://www.indiana.edu/~iulcwp/pdfs/02-clopper02.pdf (accessed 07 March 2014)

Cutler, Anne. 1984. Stress and accent in language production and understanding. In Dafydd Gibbon & Helmut Richter (eds.), Intonation, accent and rhythm: Studies in Discourse Phonology, 77–90. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Dell, François. 1985. Les règles et les sons. Paris: Hermann.

Deterding, David. 2011. English language teaching and the lingua franca core. Proceedings of the 17th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences (ICPhS), Hong Kong, August 17–21 August, 92–95.

Domahs, Ulrike, Safiye Genç, Johannes Knaus, Richard Wiese & Barış Kabak. 2012. Processing (un)predictable word stress: ERP evidence from Turkish. Language and Cognitive Processes 28 (3). 335–354.

Domahs, Ulrike, Ingo Plag & Rebecca Carroll (2014). Word stress assignment in German, English and Dutch: Quantity-sensitivity and extrametricality revisited. Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics 17. 59–96.

Dresher, B. Elan & Aditi Lahiri. 2005. Main stress left in Early Middle English. In Michael Fortescue, Eva Skafte Jensen, Jens Erik Mogensen & Lene Schøsler (eds.), Historical Linguistics 2003. Selected papers from the 16th International Conference on Historical Linguistics, Copenhagen, 10–15 August 2003, 75–85. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Dupoux Emmanuel, Christophe Pallier, Núria Sebastián Gallés & Jacques Mehler. 1997. A destressing ‘deafness’ in French? Journal of Memory and Language 36. 406–21.

Dupoux Emmanuel, Sharon Peperkamp & Núria Sebastián Gallés. 2001. A robust method to study stress ‘deafness’. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 110 (3). 1606–18.

Dupoux Emmanuel, Nuria Sebastián Gallés, Eduardo Navarrete & Sharon Peperkamp. 2008. Persistent stress ‘deafness’: The case of French learners of Spanish. Cognition 106 (2). 682–706.

Fikkert, Paula, B. Elan Dresher & Aditi Lahiri. 2006. Prosodic preferences: From Old English to Early Modern English. In Ans van Kemenade & Bettelou Los (eds.), The handbook of the history of English, 125–150. Oxford: Blackwell.

Flege, James Emil & Ocke-Schwen Bohn. 1989. An instrumental study of vowel reduction and stress placement in Spanish-accented English. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 11., 35–62.

Flege, James Emil. 1995. Second-language speech learning: Theory, findings, and problems. In Winifred Strange (ed.), Speech perception and linguistic experience: Issues in cross-linguistic research, 233–277. Timonium, MD: York Press.

Fournier, Jean-Michel. 2007. From a Latin syllable-driven stress system to a Romance versus Germanic morphology-driven dynamics: In honour of Lionel Guierre. Language Sciences 29 (2–3). 218–236.

Giegerich, Heinz J. 1992. English Phonology: An introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Guion, Susan G., Tetsuo Harada, & J. J. Clark. 2004. Early and late Spanish-English bilinguals’ acquisition of English word stress patterns. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 7(3). 207–226.

Gut Ulrike. 2003. Prosody in second language speech production: The role of the native language. Fremdsprachen Lehren und Lernen 32. 133–152.

Gut, Ulrike. 2005. Nigerian English prosody. English World-Wide 26 (2). 153–177.

Gut Ulrike. 2009. Non-native speech. A corpus-based analysis of the phonetic and phonological properties of L2 English and L2 German. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Hahn, Laura D. 2004. Primary stress and intelligibility: Research to motivate the teaching of suprasegmentals. TESOL Quarterly 38 (2). 201–223.

Hayes, Bruce. 1982. Extrametricality and English stress. Linguistic Inquiry 13 (2). 227–276.

Hubicka, Olga. 1980. Why bother about phonology? Practical English Teaching 1(1). 22–24.

Jenkins, Jennifer. 2000. The phonology of English as an international language: New models, new norms, new goals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jones, Daniel. 2006. English pronouncing Dictionary. Cambridge: University Press.

Kabak, Barış & Irene Vogel. 2001. The phonological word and stress assignment in Turkish. Phonology 18. 315–360.

Kabak, Barış, Kazumi Maniwa, Kazumi & Nina Kazanina. 2010. Listeners use vowel harmony and word-final stress to spot nonsense words: A study of Turkish and French. Journal of Laboratory Phonology 1 (1). 207–224.

Kachru, Braj B. 1985. Standards, codification and sociolinguistic realism: The English language in the outer circle. In Randolph Quirk & Henry Widdowson (eds.), English in the world: Teaching and learning the language and literatures, 11–30. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kijak, Anna. 2009. How stressful is L2 stress? A cross-linguistic study of L2 perception and production of metrical systems. The Hague: LOT Publications.

Kingdon, Roger. 1958. The groundwork of English stress. London: Longman.

Kretzschmar, William A. Jr. 2008. Standard American English pronunciation. In Edgar W. Schneider (ed.), Varieties of English. Volume2: The Americas and the Caribbean, 37–51. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Liberman, Mark & Alan Prince. 1977. On stress and linguistic rhythm. Linguistic Inquiry 8. 249–336.

Pater, Joe. 1997. Metrical parameter missetting in second language acquisition. In S.J. Hannahs & Martha Young-Scholten (eds.), Focus on phonological acquisition, 235–261. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Peperkamp, Sharon & Emmanuel Dupoux. 2002. A typological study of stress ‘deafness’. In Carlos Gussenhoven & Natasha Warner (eds.) Papers in Laboratory Phonology 7, 203–240. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Roach, Peter. 2009. English phonetics and phonology: A practical course, 4th edn. Cambridge University Press.

van Rooy, Bertus. 2002. Stress placement in Tswana English: The makings of a coherent system. World Englishes 21 (1). 145–160.

Schwab, Sandra & Joaquim Llisterri. 2011. Are French speakers able to learn to perceive lexical stress contrasts? Proceedings of the 17th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences (ICPhS), Hong Kong, August 17–21, 1774–77.

Simo Bobda, Augustin. 1995. The phonologies of Nigerian English and Cameroon English. In Ayo Bamgbose, Ayo Banjo & Andrew Thomas (eds.), New Englishes: A West African perspective, 248–268. Ibadan: Mosuro Publishers.

Simo Bobda, Augustin. 2008. Predictability of word stress in African English: Evidence from Cameroon English and Nigerian English. In Augustin Simo Bobda (ed.), Explorations into language use in Africa, 161–181. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Simo Bobda, Augustin. 2010. Word stress in Cameroon and Nigerian Englishes. World Englishes 29(1). 59–74.

Simo Bobda, Augustin. 2011. Understanding the innerworks of word stress in RP and Cameroon English: A case for a competing constraints approach. International Journal of English Linguistics 1(1). 81–104.

Tottie, Gunnel. 2002. An introduction to American English. Malden, MA & Oxford: Blackwell.

Trouvain, Jürgen & Ulrike Gut (eds.), Non-native prosody: Phonetic description and teaching practice. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Yavaş, Mehmet. 2011. Applied English phonology, 2nd edn. London: Blackwell.

Zerbian, Sabine. 2013. Prosodic marking of narrow focus across varieties of South African English. English World-Wide 34(1). 26–47.

Appendix 1:

Structures of nonce words created for Study 1 (V denotes a tense vowel):

2 syllables:

Cə•CV, CV•Cə, CV•CV

3 syllables:

Cə•CV• Cə, CV•Cə•CV, CV•CV•Cə, CV•Cə•Cə

4 syllables:

Cə•CV•Cə•CV, CV•Cə•CV•Cə, CV•Cə•CV•CV, CV•Cə•Cə•CV, CV•CV•Cə•CV

Appendix 2:

List of words presented in Study 2:

Disyllabic words: confused, constant, laptop, occur, police, refer

Polysyllabic words: analysis, annual, attention, calendar, component, computer, continuous, dictionary, examine, formulate, hypothesis, interpret, manipulated, memory, paradise, parenthesis, phenomenon, proposal, qualitative, reference, reviewed, speculation, treatment, variable