4 Cross-linguistic influence in second vs.third language acquisition of phonology

1 Cross-linguistic influence

The term cross-linguistic influence was first introduced by Sharwood-Smith (1983) to refer to transfer-related phenomena in a theory-neutral manner. It is intended to cover a wider range of linguistic influences including interference, transfer, borrowing or language loss triggered by the coexistence of various language systems.

Cross-linguistic influence in second language acquisition research has been traditionally perceived to be a one-to-one type of transfer between the native and the target language. However, as early as the 1980s, some scholars attempted to broaden this understanding by pointing not only to the native tongue but also to other non-native languages as potential sources of influence in the acquisition of subsequent languages. For instance, Gass and Selinker (1983: 372) define language transfer as “the use of native language (or other language) knowledge [...] in the acquisition of a second (or additional) language”. Along the same lines, Sharwood-Smith (1994: 198) provides the following definition of CLI, according to which it pertains to “the influence of the mother tongue on the learner’s performance in and/or development of a given target language; by extension, it also means the influence of any ‘other language’ known to the learner on that target language”.

Such a broader view going beyond L1 influence has been fully embraced by researchers working on third or additional language acquisition such as Cenoz, Hufeisen and Jessner (2001) and De Angelis (2007). A number of empirical studies conducted from the multilingual perspective have allowed to challenge some well-established assumptions that identify the native language as the only or prevailing source of transfer and, consequently, to modify the existing theoretical models. This resulted in a new conceptualisation of transfer-related phenomena, acknowledging various interactions between non-native languages and a simultaneous influence of more than one language on the target language being acquired. Therefore, the traditional one-to-one type of transfer associated with SLA was replaced by a suggestion of a many-to-one type of interference and

Magdalena Wrembel, Faculty of English, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland magdala@wa.amu.edu.pl

a proposal of the so called ‘combined cross-linguistic influence’ (De Angelis 2007: 21).

The studies conducted to date have largely confirmed the assumption of combined CLI and, at the same time, identified a number of factors that seem to condition the source, direction and relative strength of the influence of previously learnt languages (both native and non-native) on the subsequently acquired language systems. Among the factors most frequently discussed in the literature are typological proximity, psychotypology, target/source language proficiency, order of acquisition of particular languages, recency of use, type of exposure and length of residence (cf. De Angelis 2007; Cenoz 2001).

As far as typological proximity is concerned, scholars generally agree that cross-linguistic influence is most likely to occur between languages which are closely related rather than those which are not (e.g. Cenoz 2001; De Angelis 2007; Williams and Hammarberg 1998). Research findings in this field demonstrate that multilinguals tend to be influenced mostly by the languages from their linguistic repertoire that are or are perceived to be the closest to the target language, although there are also less frequent cases of reliance on distant languages. The factor of language distance can be seen as an objective formal measure of a genetic relationship between language families or as learners’ subjective perception of that language distance, i.e. psychotypology. According to Kellerman (1987), transferability is conditioned by two constraints, namely psychotypology and prototypicality, i.e. more prototypical forms/features in the source languages determine a higher degree of CLI into the target language, especially if these languages are perceived to be related/similar. A further distinction is drawn in the area of factors conditioning CLI between relatedness (i.e. genetic affiliation or typological proximity between languages belonging to the same or different language family or group) and formal similarity (i.e. explicit identification of similarity between unrelated languages with respect to some language components or features, De Angelis 2007).

The proficiency factor is also commonly acknowledged in the literature as conditioning the source and strength of cross-linguistic influence. On the whole, research results so far have mostly attested CLI at the early stages of acquisition of the target language, when the proficiency level in this additionally acquired language is relatively low and learners tend to resort to transfer more frequently as a coping strategy (e.g. Ringbom 1987; Odlin 1989; Hammarberg and Hammarberg 2005; Wrembel 2010). Furthermore, Odlin (1989) claims that transfer characteristic for the low proficiency level in the target language is usually negative, as opposed to the positive type of transfer which typically occurs at more advanced stages of acquisition when learners take advantage of their previous linguistic knowledge much more. Interestingly, some scholars pointed also to proficiency level in the source language as an important variable for CLI, although few systematic studies investigated it further. It tentatively appears that other non-native languages can be sources of cross-linguistic influence irrespective of how proficient the multilingual learners are (cf. Ringbom 1987; De Angelis 2007), however, some claim that the proficiency threshold level in a non-native language must be sufficiently high in order to exert influence on another currently acquired foreign language (e.g. Fernandes-Boëchat 2007).

Other CLI-related factors involve the length of residence and exposure to a foreign language environment which are generally found to influence the amount and type of transfer. Nonetheless, recency of use has been identified as one of the focal factors in several studies on multilingualism since 1960s (cf. Vildomec 1963). The underlying assumption is that recent use tends to trigger more potential influence due to the previous activation of some linguistic information stored in the mind of a multilingual (cf. Williams and Hammarberg 1998). Finally, the order in which languages were acquired was also found to determine the amount and type of cross-linguistic influence (Dewaele 1998).

Recent developments in investigations on transfer phenomena have resulted in a proposal of a complex scheme put forward by Jarvis and Pavlenko (2007: 20) that aims at characterising various types of cross-linguistic influence. The developed classification tries to account for CLI with respect to ten dimensions including (1) the area of language knowledge (e.g. phonological, semantic, lexical transfer etc.), (2) directionality (forward, reverse, lateral, multidirectional transfer), (3) cognitive level (linguistic vs. conceptual transfer), (4) type of knowledge (implicit vs. explicit), (5) intentionality (intentional vs. unintentional transfer), (6) mode (productive vs. receptive), (7) channel (aural vs. visual), (8) form (verbal vs. nonverbal), (9) manifestation (overt vs. covert) and (10) outcome (positive vs. negative). For the purpose of the present study, the notion of directionality of CLI will be particularly relevant. Therefore it will be described in more detail. The distinction between “forward transfer” (L1 → L2) as well as “reverse” or “backward transfer” (L2 → L1) is used rather conventionally in the SLA literature (e.g. Gass and Selinker 2001). These terms could be potentially extended to third or additional language acquisition provided that the sequential order of acquisition of L1, L2, L3, Ln is unambiguous and relevant, which is rarely the case, taking into account an array of other factors conditioning CLI. In an attempt to account for the complex nature of third or additional language acquisition, Jarvis and Pavlenko (2007) introduced the term “lateral transfer” to refer to any influence of a non-native (or post-L1) language on another non-native language (e.g. L2 → L3, L3 → L4). Furthermore, “bidirectional or multidirectional transfer”refers to the cases in which two or more languages from the multilinguals’ repertoire function simultaneously as source and recipient languages (L1 ↔ L2, L2 ↔ L3).

2 VOT in second and third language acquisitionand new varieties of English

Voice onset time of initial plosives is frequently selected as the focus of investigations on interference-related phenomena in foreign language acquisition for several reasons. On the one hand, it is recognised as a significant feature correlated with a high degree of a perceived global foreign accent (e.g. Major 1990). On the other hand, due to the precise nature of the acoustic measurements of VOT, it allows for statistical comparisons and hypothesis testing. The subsequent overview of the literature shows major findings and differences in methodological approaches on cross-linguistic influence in VOT patterns in research on second language acquisition (SLA), third language acquisition (TLA) and the acquisition of new varieties of English.

2.1 VOT in SLA

As pointed out by Hansen Edwards and Zampini (2008) stop consonants are amongst the most widely studied classes of sounds in second language acquisition research with a focus on one acoustic cue, namely voice onset time. The SLA literature provides a lot of evidence of transfer of L1 VOT values in the acquisition of L2 aspiration patterns of stops, especially at the lower levels of L2 proficiency (e.g. Flege 1987; Flege and Hillenbrand 1987). More advanced learners were found to be able to approximate native speaker norms and to differentiate L1 and L2 with respect to VOT (e.g. Caramazza et al. 1973; Flege 1987, 1991). Only the most proficient L2 learners were reported to be able to produce foreign language aspiration patterns with a mean VOT duration that was like the one of the monolingual native speakers of the target variety (Flege 1987). The inability to distinguish between differently aspirated plosives in the L1 and L2 by inexperienced L2 learners was explained by means of the proposed mechanism of equivalence classification which blocks the formation of a new phonetic category in case when L1 and L2 sounds are not sufficiently dissimilar (Flege 1987; Flege and Hillenbrand 1987).

According to Flege’s (1995) Speech Learning Model (SLM), early acquirers are able to establish separate phonetic categories for L1 and L2 stops, however, late L2 learners are more likely to create a new “merged” L2 category, which may deflect away from both L1 and L2 categories in order to maintain the phonetic contrast between the two languages. Such “compromise” or “hybrid” VOT values for both languages were evidenced in several SLA studies (Flege 1987; Flege and Eefting 1988; Major 1992). The results suggest that also L1 phonetic representations may get restructured as the result of L2 acquisition and the production of native language VOT values may be affected by the shift towards more target-like values in the L2, thus resulting in the so called regressive transfer (e.g. Waniek-Klimczak 2011). Furthermore, a number of studies have explored various factors that may influence the degree to which L2 learners are able to approximate native-like VOT durations. The most frequently explored factors included the age of acquisition, the effects of the speaking rate or language mode activation. Many researchers found that early bilinguals are more likely to produce initial plosives with target language durations than those subjects who started acquiring the second language at a later age (e.g. Flege 1991). Moreover, language proficiency was shown as a significant factor influencing the degree to which L2 learners are able to approximate native-like VOT durations (e.g. Flege and Hillenbrand 1984; Flege 1987). Since VOT length may alter as a function of the speaking rate, some studies were conducted also on the factor of rate-related VOT adjustments that need to be made by L2 learners in an attempt to approximate target norms (cf. Schmidt and Flege 1996). The influence of other languages the participants of these studies knew has been ignored completely though.

2.2 VOT research in TLA

By contrast, the mutual influence of all languages of multilinguals is the focus of studies from the perspective of third language acquisition (TLA), although relatively few studies to date have explored VOT patterns in this framework, where L3 phonological acquisition remains an understudied domain (cf. Cabrelli Amaro 2012). In the earliest reported study in this area, Tremblay (2007) analysed the acoustic measurements of voice onset time of four L1 English/L2 French bilinguals at the early stages of acquisition of L3 Japanese. The results showed similar VOT values for the L2 French and L3 Japanese which were much lower than for the long-lag L1 English VOT. The findings were interpreted as an indication of the L2 effect on L3 phonological acquisition, although the L3 VOT values approximated L2 French and, at the same time, native Japanese target norms. Moreover, the participants’ sample was very limited. Interestingly enough, no task effect was found as the VOT patterns in L3 did not differ significantly with respect to the task performed, i.e. word list reading or delayed repetition.

A comprehensive study by Llama, Cardoso and Collins (2010) investigated whether the “L2 status” or language typology was the determining factor in the production of voiceless stops in stressed onset position in L3 Spanish. The experiment was based on target word list reading and involved two groups of learners; one with L1 English and L2 French, the other with L1 French and L2 English. The results indicated that the cross-linguistic influence from the L2 rather than typological proximity or the L1 transfer alone seemed to be the stronger predictor in the acquisition of VOT patterns in L3. However, the findings were not unambiguous as to the prevailing source of CLI pointing to the interaction of both native and non-native influences on the third language phonology. Particularly noteworthy is the application of a mirror-design methodology which allowed for a reliable verification of the research hypothesis. However, the lack of data in the participants’ L1s and the reliance on the literature reference values as a baseline instead appears to be a shortcoming of this valuable study.

Wunder (2010), on the other hand, analysed text reading samples of eight L1 German speakers with respect to the VOT values in their L2 English and L3 Spanish. Her findings were mixed pointing to either L1 effect or combined L1 German and L2 English cross-linguistic influence on the aspiration patterns in L3 Spanish. The largest pool of VOT measurements was assigned to the category of ‘hybrid’ values in which it was not possible to determine whether the source of influence on L3 VOT were the L1 German or native Spanish values. In conclusion, Wunder stated that her results contradicted previous research demonstrating a prevailing L2 influence on L3 phonology (e.g. Hammarberg and Hammarberg, 2005).

Similar results were reported by Sypiańska (2013) who examined VOT of word-initial /p, t, k/ in multilinguals with the following language repertoire: L1 Polish, L2 Danish and L3 English. Her findings attested a combined influence of both L1 and L2 on the VOT patterns in L3 English. An interesting case of a regressive transfer was also observed since the effect of L3 English was visible in increased VOT values in L1 Polish and L2 Danish in the trilingual group when compared to a bilingual control group with L1 Polish and L2 Danish. Sypiańska concluded that all component languages of multilingual subjects interact and influence one another in the global language entity.

In a series of parallel studies Wrembel (2011, 2014) investigated VOT patterns in trilingual acquisition as a selected phonetic dimension of a foreign accent in order to complement previous research on perceived foreign accentedness based on L3 accent ratings (cf. Wrembel 2012a, 2012b). The results of the studies involving different language combinations – (1) L1 Polish, L2 English and L3 French; (2) L1 Polish, L2 English and L3 German – revealed that the multilingual subjects contrasted between VOT duration in all three language systems (i.e. the mean values for /p, t, k/ in stressed onset positions were significantly different in L1, L2 and L3). The reported L3 values corresponded to compromise VOT durations and were intermediate between the L1 and L2 mean VOT. The findings corroborated the coexistence of the L1 and L2 effect, and substantiated the assumption of a combined cross-linguistic influence in L3 acquisition. It was concluded that further research on different multilingual groups with various linguistic repertoires may be necessary to provide more evidence for these findings.

2.3 VOT in studies on new English varieties

Investigations into initial plosive voicing contrasts are relatively scarce in research in new varieties. To the best of my knowledge, a series of studies were conducted to this effect in the South African context (Wissing 2005; Wissing and Pretorius 1996) as well as from an Asian perspective (Poedjianto 2002; Shahidi and Rahim 2011). These mainly focus on L1 influence although the possible influence of language proficiency has also been studied. Like in SLA studies, further languages the participants speak remain uninvestigated.

Poedjianto (2002) investigated the voicing contrast in the Indonesian variety of English. The findings did not indicate any voicing contrast in Indonesian English between /p/-/b/ in the beginner learners, unlike the general case with English /p/-/b/. However, taking into consideration that the main indicator of the voicing contrast in Surabaya Indonesian is phonation (i.e. stiff and slack voice) the author hypothesises that there will be some adjustment made to reduce slackness along with the increase of VOT in Indonesian English. Moreover, Poedjianto predicts that VOT will progressively get longer across proficiency levels.

The production of initial plosives in the Malaysian variety of English was explored by Shahidi and Rahim (2011). Unlike in English, Malay voiceless plosives are always unaspirated. The acoustic measurements of the participants’ productions of Malay and English voiced and voiceless obstruents demonstrated short lag VOT values for both languages for /p, t, k/ ranging between 10–30 ms) and a voicing lead for the voiced plosives. The phonetic realisations of Malaysian English initial plosives were found to be significantly different (i.e. lower) from the native English values. The authors concluded that the voicing patterns for Malay and Malaysian English are nearly identical thus corroborating the claim of L1 influence.

The investigations into VOT patterns in African varieties of English feature studies by Wissing and Pretorius (1996) on Setswana, one of the Sotho languages of South Africa, and by Wissing (2005) on the aspiration of voiceless stop consonants in Southern Sotho. Sotho has a dual system in which the presence or absence of aspiration is phonemic, unlike in English where aspiration is phonetically motivated. Moreover, Sotho languages are characterised by long voicing lag in voiceless plosives. The results of Wissing and Pretorius’ (1996) study showed that voice onset time values for /p, t, k/ produced by Setswana speakers of English exceeded those reported for native English. Wissing’s (2005) study yielded comparable results with strongly aspirated voiceless plosives observed both in the Southern Sotho native renditions (in the 80–96 ms range) as well as their productions of the respective consonants in English (in the 55–90 ms range). In a detailed account for individual results the author proposes a specific explanation of language interference based on some category confusion (in case of significantly shorter aspiration in /p/) rather than the typical negative transfer from the L1. All in all, the mean VOT values in this variety of English appear to be intermediate between the speakers’ native tongue and expected English values, yet L1 influence is strongly noticeable.

In summary, studies in the framework of third language acquisition consider the largest number of different types of CLI and the widest range of potentially influencing factors compared to studies carried out in the framework of second language acquisition or new English varieties. It is the aim of this study to demonstrate the advantages of a multifaceted approach to investigating CLI from which studies on L2 acquisition and new English varieties could profit.

3 Study

3.1 Aims and research questions

The present study constitutes a part of a larger scale project into third language phonological acquisition based on a series of studies on VOT patterns in different language combinations conducted by the author. Previous results of investigations on VOT patterns in L3 French and L3 German were presented in Wrembel (2014).

The study aims to further investigate the complexity of transfer of voice onset time (VOT) patterns in trilingual acquisition. Its major objective is to explore the sources of cross-linguistic influence (CLI) in the acquisition of VOT in L3 French by L1 German learners with an advanced competence in L2 English. Furthermore, the major goal of this contribution is to compare the tendencies in VOT acquisition patterns found in L3 to those observed in research on SLA or new varieties of English.

The languages involved in the present study all make a phonological distinction between two categories of stops, however, their phonetic realisation differs. English and German belong to the category of the so called aspirating languages (cf. Lisker and Abramson 1964), which differentiate between voiceless aspirated and voiceless unaspirated plosives, whereas French is a voicing language, in which there is a distinction between voiced and voiceless unaspirated plosives. In English /p/, /t/, /k/ are implemented as long-lag stops with VOT around 60–80 ms (Lisker and Abramson 1964), while in German the average VOT values are said to be between 30 and 50 ms (Angelowa and Pompino-Marschall 1985). In turn, in French /p/, /t/, /k/ are implemented as short-lag stops with mean VOT values around 20–30 ms (Caramazza et al. 1973).

The study poses the following research questions in order to address the specified objectives:

- 1) Do multilingual subjects differentiate among their L1, L2 and L3 with regard to VOT values?

- 2) Do L3 VOT patterns approximate the participants’ L1 German, L2 English or the L3 native French norms?

- 3) Which factors have an influence on the CLI found for VOT production in the three languages?

- 4) Do the trends observed in L3 acquisition of VOT resemble the ones reported in studies on SLA and new English varieties?

On the basis of the overview of the literature on third language acquisition, three potential general outcomes as to the sources of CLI were hypothesised: (1) native L1 German would be a prevailing source of cross-linguistic influence for the acquisition of VOT patterns in L3 French; (2) the influence of L2 English, the so called “foreign language effect” would override the native language in shaping L3 VOT values; (3) both the native and non-native languages would have an impact on the VOT values in the L3, thus collaborating the assumption of a combined cross-linguistic influence.

With regard to the comparison between patterns of VOT acquisition it was hypothesised that (1) similar trends are observed in the acquisition of a second language, third language or new varieties; (2) the trends differ significantly, thus reflecting the specific nature of these three contexts of acquisition.

3.2 Participants and procedure

The study involved 18 native speakers of German who were students at the University of Münster, Germany at the time of data collection. There were 15 female and 3 male participants and their mean age was 29 years (SD = 5.6), ranging from 22 to 43 years old. For all of the participants English was their second language (L2) and French was their third language (L3) both in terms of chronology and the dominance of use. The level of proficiency in L2 English was advanced (C1, according to CEFR) with an average length of training being 14 years (SD = 4.6) and the age of onset at 10 years old (SD = 1.6). In case of L3 French, the participants’ proficiency level was intermediate (B1/B2 level according to CEFR). Foreign language proficiency level was self-declared by the participants based on internal course placement assessment procedures. The average amount of time of formal training in French (YFT) was 7 years (SD = 3.3), whereas the mean age of onset of learning (AOL) equalled 13 years (SD = 1.5). The total number of foreign languages known by the participants equalled on average 3.3 (SD = 1.1) ranging from 2 to 7. Their self-evaluation of the general language competence in L3 French on a scale from 1–5 (1 = very poor, 5 = very good) equalled 3.3 (SD = 0.8), similarly to the self-evaluation of L3 pronunciation which was 3.4 (SD = 0.9) corresponding to a category between satisfactory and good. The participants had undergone general linguistic training, however, no practical training of the phonetic feature under investigation was reported.

The data collection procedure involved all three language systems of the multilingual participants, i.e. L1 German, L2 English and L3 French. The stimuli consisted of three word lists with 18 target words in the respective languages. The target words included voiceless plosives /p, t, k/ in stressed onset positions in the following context of high, mid and low vowels, in mono- and disyllabic words, thus generating a total of 18 items per language list. The words were randomised and embedded in carrier phrases in particular languages (i.e. Ich sage. . . , I am saying . . . , Je dis. . .). The recordings were made in a clearly specified language mode in the natural order of acquisition of the languages involved, with German as first, English as second and French as third. The participants were asked to read the lists at a natural speed with a few minutes’ break interval between the recordings. The interaction with the researcher was carried out in the language of the subsequent recording to promote the activation of the respective languages. Finally, a language background questionnaire was administered to tap the subjects’ language history and use.

The stimuli were recorded with the application of Audition CS5.5 as 16-bit mono files at 32000 Hz sampling frequency. Tokens were excluded from the analysis if the target words were mispronounced. A total of 1512 tokens were subjected to an acoustic analysis performed using PRAAT 5.2.15 (Boersma and Weenick 2010). Voice onset time was measured in milliseconds (ms) as the interval between the release burst and the beginning of the regular vocal fold vibrations.

3.3 Results

The analysis of the results was based on the acoustic measurements of mean voice onset time of the target words read in the carrier phrases in L1 German, L2 English and L3 French and it involved (1) mean VOT values for L1, L2 and L3, (2) the comparison to VOT reference values, (3) the analysis of the context effects and (4) the analysis of variance and correlation analysis accounting for the relationships between independent variables. The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS.

3.3.1 Mean VOT values for L1, L2 and L3

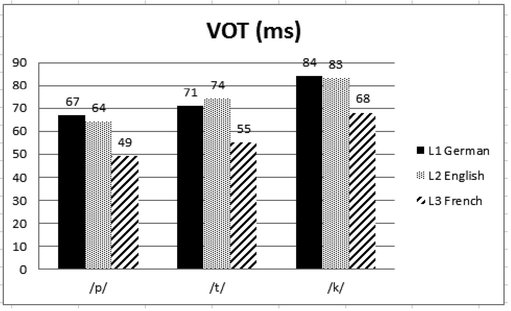

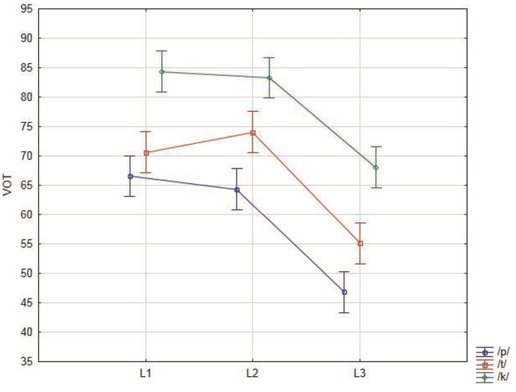

Figure 1 presents the mean results of VOT measurements for the voiceless plosives /p/, /t/, /k/ in stress onset positions in the participants’ L1 German, L2 English and L3 French. The VOT values produced in the participants’ first and second language were relatively similar (L1 German /p/ = 67 ms, /t/ = 71 ms, /k/ = 84 ms; L2 English /p/ = 64 ms, /t/ = 74 ms, /k/ = 83 ms), and were characterised by a longer lag than the values for L3 French (/p/ = 49 ms, /t/ = 55 ms, /k/ = 68 ms).

Figure 1: Mean VOT (ms) values

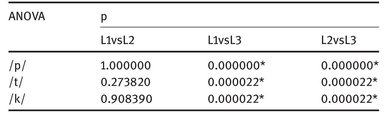

Across-language comparisons of means for /p/ /t/ /k/ were performed by means of the analysis of variance and a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test. Repeated-measures ANOVA pointed to significantly different values for initial voiceless plosives between L1 German and L3 French as well as between L2 English and L3 French (p < .05), however, the difference between mean VOT values in L1 German and L2 English was not statistically significant.

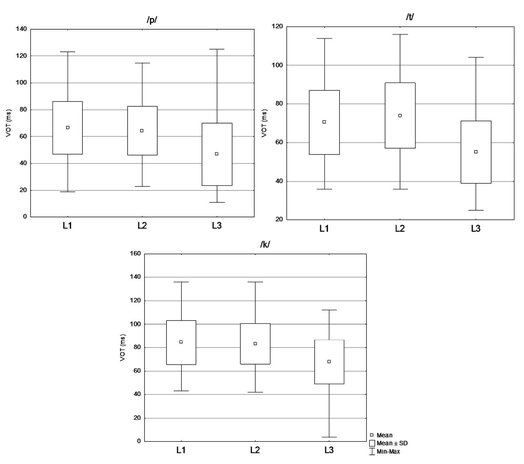

The following box plots (Figure 2–4) illustrate the observed tendencies in VOT patterns in the respective languages separately for the stressed onset plosives /p/, /t/ and /k/. While the distribution in L1 German and L2 English shows only negligible discrepancies with respect to VOT means, standard deviation as well as the minimum-maximum range, the mean values for L3 French remain significantly lower although the minimum-maximum range is even more pronounced.

The language effect was thus observed to hold only between the third language and the remaining two phonological systems. The mean voice onset time values in L3 French were considerably lower than the respective values in L1 German and L2 English, which, on the other hand, display very similar patterns of distribution.

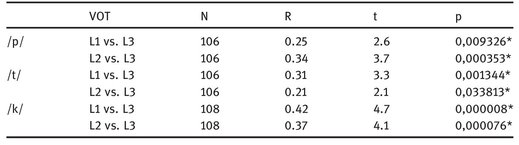

In order to investigate the relationship between the VOT values observed in L3 French and those of the native L1 German as well as L2 English the Pearson correlation analysis was applied. The calculated coefficients pointed to positive weak to moderate correlations between the mean VOT values. In case of voiceless bilabial plosive /p/ the correlation between non-native languages (L3 French and L2 English) was slightly higher (R = .34) than the one between the L3 and the native German VOT values (R = .25). For the alveolar and velar plosives /t/ and /k/ the correlations were slightly stronger between L3 and L1 rather than L3 and L2, although they were in the weak range for /t/ (R = .31 vs. R = .21 respectively) and in the medium range for /k/ (R = .42 vs. R = .37 respectively). It appears impossible to state unequivocally whether L3 VOT values were correlated more with the native values or those of another foreign language as the differences between the coefficients were relatively small.

Figures 2–4: Box plots for /p/ /t/ /k/ in L1 German, L2 English and L3 French

Table 2: Pearson’s correlations between L3 VOT values and L1 and L2

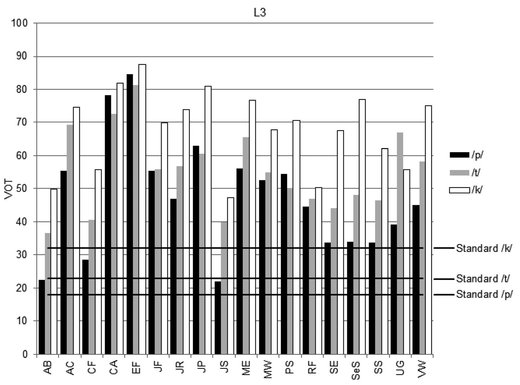

3.3.2 Individual variation

The analysis of VOT measurements investigated also the individual variation in the generated VOT values for /p/ /t/ /k/. Due to space limitations, only the individual distribution for L3 French is presented, which is of most relevance for the present study. As can be seen from Figure 5, nearly all of the participants with a few exceptions (CA, EF, JP) followed the universal VOT pattern, with bilabials plosives yielding the shortest VOT values, and velar – the longest. The greatest variability seems to be visible for /p/, whereas /t/ and /k/ tended to generate less interspeaker variation. Individual average VOT measures are presented against the selected reference VOT values for French (Caramazza et al. 1973). On the whole, the observed L3 values surpass the reference VOT measurements, with such individuals as CA, EF representing the most extreme departures from the norm. On the other hand, the L3 performance of some individual participants like AB, CF, JS appears to be fairly close to the French norm VOT values.

Figure 5: Individual variation in L3 French VOT for /p/ /t/ /k/ against the reference VOT values

3.3.3 Comparison with L1 reference values

One-sample t-tests were administered to compare the calculated mean VOT durations for /p, t, k/ in L1 German, L2 English and L3 French to the reference values often quoted in the literature for the respective languages. The overall finding was that the VOT measurements differed significantly from the native norms as reported in the literature (see Table 3). More specifically, the VOT values for voiceless stops in L1 German of the multilingual participants were found to be significantly longer than the reference VOT German values quoted in the literature (Angelowa and Pompino-Marschall 1985), i.e. /p/ 66.6 vs. 36 ms; /t/ 70.6 vs. 39 ms; /k/ 84.3 vs. 47 ms. As far as the VOT measurements in L2 English are concerned they were demonstrated to be closer to the reference range (Lisker and Abramson 1964), especially in the case of /k/ (83.3 vs. 84 ms), however, the bilabial and alveolar stops were realised on average with a longer lag than the reference values (/p/ 64.3 vs. 59 ms; /t/ 74 vs. 67 ms). Although the differences were found to be statistically significant for /p/ and /t/, they were still within the accepted 5–10 ms range.

Considerable VOT lengthening was also observed for L3 French when compared to the literature reference values (Caramazza et al. 1973), with /p/ equal to 46.8 vs. 18 ms; /t/ 55.1 vs. 23 ms; /k/ 68 vs. 32 ms). All in all, the French stops were implemented by the multilingual participants as long-lag and thus the L3 phonetic norms were not approximated successfully. The findings demonstrated “compromise” values for L3 French that were longer than typical French native values but shorter than the values observed for both L1 German and L2 English. It is thus impossible to tease apart the influence of the first or the second language on the values in the third language as the values for the participants’ native German and L2 English did not differ significantly from one another.

Table 3: Comparison to VOT reference values in L1 German, English and French, p < .01. (1Angelowa and Pompino-Marschall 1985; 2 Lisker and Abramson 1964; 3 Caramazza et al. 1973)

A potential explanation for the mismatch in the observed L1 German VOT values in this study compared to the reference values from Angelowa and Pompino-Marschall’s (1985) study could be related to dialectal differences among the participants; in the former study representing mainly the Western Low German area, whereas in the latter participants came from the South German region. Braun (1996) provides relevant support for this suggestion on the basis of her comparison of VOT values in various regional varieties of German in which the VOT values for North-Western German speakers tend to be higher resembling those reported in the present study. Consequently, this fact could have also contributed to the present participants’ rather successful renditions of target-like VOT values for English /p, t, k/.

3.3.4 Analysis of variance

A two-factor ANOVA between languages (L1, L2, L3) and VOT durations of the voiceless plosive sounds /p, t, k/ was performed as part of the analysis of variance. Although the differences in VOT values within the factors of language (F (2; 959) = 92.6, p < .05) and segments (F (2; 959) = 89.6, p < .05) were shown to be significant, the interaction between languages and segments on the VOT values was not found to be significant (F (4; 959) = 0.93, p > .05). The lack of interaction between languages and segments did not depend on the type of language as presented in Figure 6.

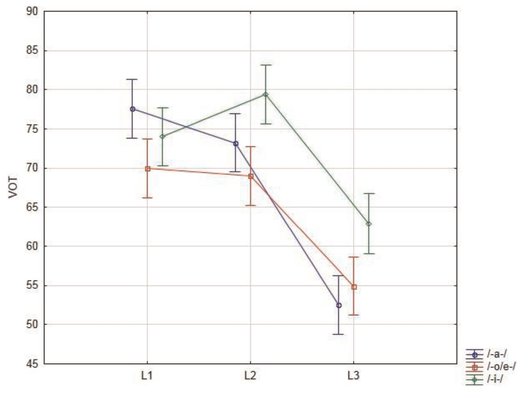

In order to investigate the interaction of the vowel context and the language on the observed VOT durations, a two-factor analysis ANOVA was performed for the factors of the language (L1, L2, L3) and the context of the vowel following the voiceless plosives in stressed onset positions in the target words (_/a/, _/i/, _/e, o/). In accordance with universal tendencies, the context of high vowels (e.g. /i/) should generate longer VOT values in the preceding plosives than the context of low vowels (e.g. /a/). The results of the analysis indicate that there are significant differences in VOT values within the factor of languages (F (2; 959) = 79.5, p < .05) and the vowel context (F (2; 959) = 11.5, p < .05). Moreover, there is also a significant interaction between the two factors (F (4; 959) = 3.98, p < .05) which depends on the type of the language (see Figure 7).

Different patterns of interaction can be observed in the respective languages with only L3 French following closely the universal patterns, i.e. the longest VOT values in the high vowel context /i/, medium for the mid vowels /e/, /o/, and the shortest for the low vowel context /a/. In the L1 German the universal tendencies were not fully observed, with the /a/ context generating on average the longest VOT values, whereas in L2 English the mid and low vowel contexts yielded different VOT duration patterns than the expected ones.

Figure 6: The interaction between the language and segment factors

3.3.5 Correlation analysis of factors influencing VOT production

The analysis of the results involved also the computation of linear Pearson’s correlation between different independent variables and the observed mean VOT durations in particular languages. The selected variables involved such factors as the participants’ age (AGE); the years of formal training in L2 English and L3 French (L2_YFT, L3_YFT); the starting age of learning of both foreign languages (L2_AOL, L3_AOL), proficiency level in L2 English and L3 French (L2_Prof, L3_Prof); self-evaluation of general language proficiency in both languages (L2_self-eval, L3_self-eval); self-evaluation of pronunciation competence in L2 and L3 (L2_self-eval PRON, L3_self-eval PRON); and the total number of foreign languages known by the participants (N_TOTAL).

No significant Pearson’s correlations were found for the observed values in L1 German and L2 English; however, L3 French displayed some interesting patterns of dependence. A positive moderate correlation was found between the years of instruction in L2 English and an average VOT duration in L3 French (r = 0.52, p = 0.03), i.e. the longer the training in English, the longer the VOT values in L3 French. Moreover, a significant negative correlation between the self-evaluation of pronunciation in L3 and VOT length in L3 for /p/ and /t/ was observed (r = –0.51, p = 0.03), i.e. the better one’s self-assessment of L3 oral performance in French, the lower the observed VOT values in L3 which corresponds to more native-like French VOT patterns. The correlations between the remaining variables did not prove significant.

Furthermore, another Pearson’s correlation analysis was performed to investigate any dependence across the selected factors. The analysis pointed to a number of significant correlations (see Table 4) including a strong positive correlation between the amount of training in L3 and the self-evaluation of L3 general competence (r = 0.69, p < .05) as well as between the amount of training in L3 and L3 proficiency level (r = 0.72, p < .05). Moreover, a strong positive correlation was found between self-evaluation of general L3 proficiency and self-evaluation of L3 pronunciation (r = 0.78, p <. 01) as well as between self-evaluation of general L3 proficiency and L3 proficiency level (r = 0.87, p <. 01). Also self-evaluation of L3 pronunciation correlated significantly with L3 proficiency level (r = 0.58, p < .01).

Table 4: Pearson’s correlations between the independent variables (*p < 0.05)

4 Discussion

The study aimed to explore the interactions between three phonological systems of multilingual subjects based on their productions of voice onset time patterns and to investigate the sources and directions of cross-linguistic interference in this area. To this end, VOT values in the participants’ L1 German, L2 English and L3 French were measured acoustically and compared to one another as well as to the reference values for native German, English and French speakers. The results of the present study will also be compared to previously conducted studies on L3 phonological acquisition of VOT patterns. A further goal of this contribution is to discuss the findings in the light of parallel studies concerning second language acquisition as well as the new varieties of English.

In the following sections the three research questions posed in the study will be discussed.

RQ 1: Do multilingual subjects differentiate among their L1, L2 and L3 with regard to VOT values?

The findings demonstrated that the participants in the present study did not distinguish between the VOT length in their native German and fairly proficient L2 English, however, they produced voiceless plosives in stressed onset positions in the L3 French with values significantly different from the previous two language systems.

It is worth noting that the L3 VOT intervals were not assimilated either to the typical reference values for native French or the subjects’ L1 German or L2 English values. The observed VOT values for L3 French were found to be intermediate between the target values and the ones established for L1 and L2, i.e. they were longer than the values typical of native French but shorter than those recorded in the participants’ renditions of L1 German/L2 English VOT.

English and German are both categorised as aspirating languages, however, traditionally the VOT values for voiceless plosives reported in the literature for English are longer than the respective ones reported for German. This trend was not reflected in the present study in which the multilingual implementations of /p, t, k/ in L1 German and L2 English were found to be nearly identical. The subjects did not differentiate between their L1 and L2 language systems in terms of VOT durations. The potential interpretation could be that they perceived the systems as not distinct enough in this respect and formed a category assimilation. An alternative account may concern the reliability of reference values provided in the literature as they can be partially questioned on methodological grounds, e.g. due to potentially different means of data elicitation procedures used. It should be stressed though that in the series of studies previously conducted by the author on different language combinations, the VOT reference values from the literature for Polish and English (cf. Keating, Mikoś, and Ganong III 1981; Lisker and Abramson 1964) were fully corroborated by the results of the studies (Wrembel 2011, 2014).

On the whole, the multilingual participants showed some evidence of restructuring their phonetic space. The observed category assimilation between L1 German and L2 English VOT may have stemmed from an advanced level of proficiency in English as well as a long exposure to this language, the recency and intensity of L2 use. The hypothesised VOT lengthening in native German values when compared to the reference literature values could have been triggered by the well established long-lag values in L2 English. This phenomenon can be interpreted as evidence for the so called “regressive transfer” or multidirectional cross-linguistic influence that has been attested previously in the SLA literature (e.g. Flege 1987; Waniek-Klimczak 2011).

What seems particularly relevant is the fact that the participants did not identify voiceless plosives in a newly acquired additional foreign language in terms of their native German categories, as they implemented /p, t, k/ in L3 French as shorter lag than the already established VOT patterns. They demonstrated some awareness of the different realisation of the target sounds in French which was reflected in the attempted modifications of the implementation of initial voiceless plosives in L3 French as hybrids between the native norm and the established VOT values for the first and second language.

The results differ from those generated in a series of similar studies conducted by the present author (cf. Wrembel 2011, 2014), which involved L1 Polish subjects with L2 English and L3 French or German. In those studies foreign language categories proved sufficiently dissimilar acoustically from the established inventory of L1 phonetic categories for the subjects to modify their realisations of /p, t, k/ in their respective foreign languages. Consequently, the implementations of voiceless plosives differed significantly across all the language systems of the multilingual participants.

In an attempt to look at the present findings from the perspective of second language acquisition, we may interpret the lack of any significant differences in VOT measures between L1 German and L2 English and thus similar realisations of the voiceless plosives distinction as the result of the phenomenon of equivalence classification as stipulated by Flege (1995) in his Speech Learning Model. Moreover, it appears that a modified category, different from the L1 German and L2 English systems was formed for voiceless plosives in stressed onset positions in L3 French. This ability of learning new patterns of segmental articulation did not seem to diminish after a critical period as all the participants were late learners. These findings seem to be in line with Flege’s (1995) SLM, which claims, among other things, that the phonetic system of a learner remains adaptive throughout lifetime and open to modifications of phonetic categories, which was the case both for the participants’ L1 and L3 VOT categories.

As far as research on SLA is concerned, there have been some reports of bilinguals being able to maintain the phonetic contrast between the two languages with respect to VOT durations (cf. Flege 1987, 1991), however, in the majority of the cases this was conditioned either by an early onset of second language acquisition or considerable advancement in the level of L2 proficiency.

Since research on this particular phonetic feature is rather scarce in studies of new varieties, it is more difficult to draw some firm conclusions. To the best of my knowledge, the existing studies did not corroborate the hypothesis of differentiation with respect to VOT patterns between the L1 (be it an Asian or African indigenous language) and the subjects’ L2 classified as a new variety of English (cf. Wissing 2005; Wissing and Pretorius 1996; Poedjianto 2002; Shahidi and Rahim 2011).

RQ 2: Do L3 VOT patterns approximate the participants’ L1 German, L2 English or the L3 native French norms?

As far as the observed L3 French VOT is concerned, the findings pointed to some compromise or “hybrid” values in L3 which were intermediate between L1 German / L2 English mean VOT values and the reference norms for native French. Since the reported values for L1 German and L2 English were clustered together it is impossible to tease apart the role of the L1 and L2 as the potential sources of cross-linguistic influence for the acquisition of VOT patterns in the third language. The conducted Pearson correlation analysis indicated positive weak to medium correlations between the mean VOT values in L3 French vs. L1 German as well as between L3 French vs. L2 English. It is not feasible to state unequivocally whether L3 VOT values were correlated more with the native values or those of another foreign language, i.e. English as the differences between the coefficients were relatively small.

RQ 3: Which factors have an influence on the CLI found for VOT production in the three languages?

It may be hypothesised that the typological proximity between language repertoires could have exerted some influence on the VOT acquisition patterns. The effect of typology could thus explain the observed category assimilation between L1 German and L2 English VOT values. On the other hand, the perception of French as being less typologically related to either German or English resulted in more divergent L3 VOT values. However, in the previous studies by the present author no conclusive evidence of the typology effect was observed as there were striking similarities between VOT patterns in L3 French and L3 German irrespective of the typological proximity between the language combinations involved. However, a closer examination of the findings pointed to partial approximation to German norms in one of the study which may be attributed to closer typological proximity between English and German. All in all, it cannot be stated unequivocally whether it was the systems of the L1 or the previously acquired L2 that exerted the greatest impact on the phonetic modification of L3 categories in the present study. Similarly to Gut’s (2010) study no conclusive evidence of L1 or L2 influence on the third language was found.

The author’s previous studies (Wrembel 2014) provided evidence for the coexistence of the L2 effect and underlying L1 interference in the acquisition of VOT patterns in L3, as the participants’ long lag VOT values in L2 English were found to exert an impact on the productions of /p, t, k/ in L3 French and German. The impact of L1 Polish proved to be more noticeable in case of L3 French (Study 1) as these two languages are so-called “voicing” languages which make a distinction between voiced and voiceless unaspirated stops, whereas the effect of L2 English prevailed in L3 German VOT patterns; these two languages can be categorised as “aspirating” languages which distinguish between voiceless aspirated and voiceless unaspirated stops (cf. Lisker and Abramson 1964). Consequently, the studies substantiated the assumption of a combined cross-linguistic influence in third language acquisition as suggested by De Angelis (2007). Moreover, the findings were, to some extent, consistent with previous studies on L3 phonological acquisition (Wrembel 2010; Llama, Cardoso and Collins 2010; Wunder 2010) which pointed to combined CLI from both native and non-native languages, yet they contradicted findings by Ringbom (1987) or Pyun (2005) who observed the prevailing influence of the L1 phonology on L3 acquisition.

In second language acquisition research, the acquisition of foreign language phonology is perceived to be primarily constrained by the transfer of established neuro-motor routines from the first language. The existing research on voice onset time patterns in new English varieties seems to confirm the major assumption from the SLA perspective concerning the prevailing impact of the first language on the acquisition of VOT durations in L2. This also holds true for studies on English acquired as a new variety. Shahidi and Rahim (2011) found that the phonetic realisations of Malaysian English initial plosives were nearly identical with the short VOT durations (10–30 ms) for /p, t, k/ in L1 Malay. Likewise, Wissing and Pretorius (1996) and Wissing (2005) demonstrated that L1 speakers of Sotho languages produced the voiceless stops in their African varieties of English with a long lag close to their native language renditions (55–90 ms). Furthermore, Poedjianto (2002) reported the lack of any voicing contrast in Indonesian English between /p/-/b/ following the L1 pattern in the subjects’ Surabaya Indonesian in which phonation acts as the main indicator of the voicing contrast. However, as this study has demonstrated, to fully account for potential CLI the focus on the L1 needs to be widened and the other languages the speakers know need to be taken into account as well.

Moreover, this study has shown that while investigating potential sources of cross-linguistic influence for the acquisition of L3 phonology, it is worth exploring potential language universal effects. The results demonstrated that the observed VOT patterns in all the languages in the present study revealed strong universal effects of the place of articulation and some effects of the vowel context. The findings of the present as well as previous studies (Wrembel 2014) demonstrated progressively longer VOT values for velars when compared to alveolars and bilabials, i.e. the so-called place of articulation hierarchy [ph < th < kh]. As far as the vowel context is concerned, VOT tended to be longer when a plosive was followed by a high rather than a low vowel, which is in line with the language universal effects reported for voice onset time (cf. Maddieson 1997).

The present analysis tried to investigate any potential dependencies among the observed VOT patterns in L1, L2 and L3 and a number of independent variables including the participants’ age, the years of formal training in L2 English and L3 French, the age of learning of both foreign languages, proficiency level in L2 English and L3 French, self-evaluation of general language proficiency in both languages, self-evaluation of pronunciation competence in L2 and L3, and the total number of foreign languages known by the participants. Some interesting correlations were found for L3 French, including a moderate positive correlation between the years of instruction in L2 English and an average VOT duration in L3 French and a significant negative correlation between the self-evaluation of pronunciation in L3 and VOT length in L3 French. The former confirms the assumption that the longer period of exposure to the first foreign language (L2) the more likely it is to exert a stronger influence on the additionally acquired foreign language (L3), in this case by lengthening VOT values characteristic for L2 English. The latter correlation indicates that the better one’s self-assessment of L3 oral performance in French the lower the observed L3 VOT values which corresponds to more native-like French VOT patterns. However, the correlations with the remaining independent variables did not prove to be significant.

Apart from proficiency, previous studies on English as an L2 have investigated the factor of age of acquisition which was shown not to be influential in this study. In previous research on new English varieties only the factor of second language proficiency has been considered so far (Poedjianto 2002; Wising 2006). The present study has demonstrated that it would be beneficial to include the factors of years of instruction and self-reported competence in the target language.

RQ 4: Do the trends observed in L3 acquisition of VOT resemble the ones reported in studies on SLA and new varieties?

The SLA literature on the acquisition of aspiration patterns of voiceless stops provides a lot of evidence for transfer of native L1 VOT values in the realisation of L2 stops (e.g. Flege 1987; Flege and Hillenbrand 1987). Furthermore, as stipulated by Flege (1995) in his Speech Learning Model late onset L2 learners are more likely to create a new “merged” L2 category, which may deflect away from both L1 and L2 categories in order to maintain the phonetic contrast between the two languages. Such “compromise” or “hybrid” VOT values for both languages are widely reported in some SLA studies (Flege 1987; Flege and Eefting 1988; Major 1992). However, more advanced learners were found to be able to approximate native target norms and to differentiate L1 and L2 with respect to VOT (e.g. Caramazza et al. 1973; Flege 1987, 1991). On the other hand, the production of native L1 VOT values may also be affected by the shift towards more native-like values in the L2, thus resulting in a regressive CLI as evidenced, for instance, by Waniek-Klimczak (2011). Recapitulating, in the SLA literature a category assimilation is commonly attested to occur between the L1 and L2 categories, thus forming a hybrid between the native and target values. However, in SLA studies the influence of other languages the participants might speak is typically not controlled for. This is taken into account in studies on third language acquisition where potential “compromise” values are conceptualised as having a different, more complex nature because of the coexistence of three or more language systems in the multilingual participants’ minds. Therefore, it is far more difficult to hypothesise what such a hybrid may look like and the possibilities for interactions among the phonological systems within the multilinguals’ repertoires are numerous.

The potential scenarios in the acquisition of third language phonology may involve as follows: (1) separate values for all the language systems of the multilingual participant, i.e. full divergence, (2) different VOT values for at least two languages involved, i.e. partial divergence/convergence, (3) compromise between the observed values for L1, L2 or L3 and the respective native norms, i.e. hybrid values, or (4) the lack of any significant differences in the VOT intervals among all the language systems of a multilingual in case when such a difference would be expected, i.e. full category assimilation. The first case of a full divergence was evidenced, for instance, in Wrembel’s study (2014), where the participants differed among their phonetic realisations of initial voiceless plosives in L1 Polish, L2 English and L3 French or German. In turn, a partial divergence/convergence was found in the present study, in which the VOT values for L1 German and L2 English were conflated possibly due to a close typological proximity, whereas the VOT values for L3 French remained distinct from the previous two language systems. Different forms of hybrid values were attested in the L3 VOT studies by Wunder (2010), Sypiańska (2013), Wrembel (2014) or the present study. They involved various examples of a compromise between the reported VOT durations for the multilingual subjects’ L1, L2 or L3 and the respective native norms. The case of full category assimilation in terms of VOT values for the L1, L2, L3, Ln of a multilingual has not been reported, to the best of my knowledge, in the TLA literature.

The scarce research on VOT acquisition patterns in new varieties has demonstrated quite a strong phonetic adjustment of the localised variety of English to the norms of the indigenous languages. In the available accounts of the realisations of the initial voiceless plosives in South African English, Malaysian English or Indian English the observed VOT values pointed to a considerable L1 transfer and adherence to the local native norms, however, some irregularities were noticed, and the tendencies showed some correlations with L2 proficiency levels. Moreover, it was not taken into account that the majority of these speakers of a new English variety are in fact multilingual and might demonstrate CLI from various other sources.

As expected, the developing TLA methodology has demonstrated the most complex patterns of cross-linguistic influence so far. The results are mixed, yet the prevailing trend points to both the native and non-native languages as having an impact on the VOT values in the L3, thus collaborating the assumption of a combined cross-linguistic influence. The area seems not to be fully explored yet due to the complexity of factors and a number of confounding variables such as proficiency levels in L2 and L3, the order of acquisition of particular languages, the frequency of use, etc. Attempts have been made to control for some of these variables examining the VOT acquisition patterns in different language combinations (see a series of studies by the present author).

5 Conclusion

The present article was intended to provide new insights into the phenomenon of cross-linguistic influence in multilinguals’ voice onset time patterns. The findings pointed to some compromise values in L3 French which were intermediate between L1 German / L2 English mean VOT and the reference values for native French. The effects of typology and advancement in L2 use were put forward to explain the observed category assimilation between L1 German and L2 English VOT durations. The subjects demonstrated some sensitivity to VOT patterns in learning a new phonetic system of the additional foreign language which was reflected in the implementation of initial voiceless plosives in L3 French as hybrids between the established VOT values for the first and second language and the target French norm. All in all, the multilingual participants showed some evidence of restructuring their phonetic space, however, in the present study it is impossible to tease apart the roles of the L1 and L2 as potential sources of cross-linguistic influence for the acquisition of VOT patterns in the third language.

A number of comparisons were drawn between the present study and a series of parallel studies on TLA conducted by the author, as well as similar research on voice onset time carried out from the perspective of SLA and new varieties. The presented discussion attempted to address the observed similarities as well as differences in the process of learning English as a second or third/ additional language or as a new variety. Further research is still needed to investigate in more depth the complex interaction between the phonological systems of multilingual learners and to provide further evidence to verify the multiple sources and directions of cross-linguistic influence.

References

Angelowa, T. & Bernd Pompino-Marschall. 1985. Zur akustischen Struktur initialer Plosiv-Vokal-Silben im Deutschen und Bulgarischen. Forschungsberichte des Instituts für Phonetik und sprachliche Kommunikation der Universität München 21. 83–96.

Boersma, Paul & David Weenick. 2010. Praat: Doing phonetics by computer. Version 5.2.15 http://www.praat.org

Braun, Angelika. 1996. Zur regionalen Distribution von VOT im Deutschen. In Angelika Braun (ed.), Untersuchungen zu Stimme und Sprache. (Zeitschrift für Dialektologie und Linguistik, Beiheft 96.), 19–32. Stuttgart: Steiner.

Cabrelli Amaro, Jennifer. 2012. L3 phonology: An understudied domain. In Jennifer Cabrelli Amaro, Suzanne Flynn & Jason Rothman (eds.), Third language acquisition in adulthood, 33–60. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Caramazza, A., G. Yeni-Komshian, E. Zurif & E. Carbone. 1973. The acquisition of a new phonological contrast: The case of stop consonants in French-English bilinguals. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 54. 421–428.

Cenoz, Jasone. 2001. The effect of linguistic distance, L2 status and age on cross-linguistic influence in third language acquisition. In Jasone Cenoz, Britta Hufeisen and Ulrike Jessner (eds.), Cross-linguistic influence in third language acquisition: Psycholinguistic perspectives, 8–20. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Cenoz, Jasone, Britta Hufeisen & Ulrike Jessner (eds.). 2001. Cross-linguistic influence in third language acquisition: Psych olinguistic perspectives. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

De Angelis, Gessica. 2007. Third or additional language acquisition. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Dewaele, Jean-Marc. 1998. Lexical inventions: French interlanguage as L2 versus L3. Applied Linguistics 19 (4). 471–490.

Fernandes-Boëchat, M. H. 2007. The CCR Theory: A cognitive strategy research proposal for individual multilingualism. Revista Luminária 8(1). FAFIUV: União da Vitória-PR, http://www.ieps.org.br/luminaria.pdf.

Flege, James Emil. 1987. The production of “new” and “similar” phones in a foreign language: Evidence for the effect of equivalence classification. Journal of Phonetics 15 (1). 47–65.

Flege, James Emil. 1991. Age of learning affects the authenticity of voice-onset time (VOT) in stop consonants produced in a second language. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 89. 395–411.

Flege, James Emil. 1995. Second-language speech learning: Theory, findings, and problems. In Winifred Strange (ed.), Speech perception and linguistic experience: Issues in cross-linguistic research, 233–277. Timonium, MD: York Press.

Flege, James Emil & Wieke Eefting. 1988. Imitation of a VOT continuum by native speakers of English and Spanish: Evidence for phonetic category formation. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 83. 729–740.

Flege, James Emil & James Hillenbrand. 1987. Differential use of closure voicing and release burst as cue to stop voicing by native speakers of French and English. Journal of Phonetics 15. 203–208.

Gass, Susan M. & Larry Selinker (eds.). 1983. Language transfer in language learning. Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

Gass, Susan M. & Larry Selinker. 2001. Second language acquisition. An introductory course, 2nd edn. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Gut, Ulrike. 2010. Cross-linguistic influence in L3 phonological acquisition. International Journal of Multilingualism 7(1). 19–38.

Hammarberg, Björn & Britta Hammarberg. 2005. Re-setting the basis of articulation in the acquisition of new languages: A third-language case study. In Britta Hufeisen & Robert J. Fouser (eds.), Introductory readings in L3, 11–18. Tübingen, Germany: Stauffenburg Verlag.

Hansen Edwards, Jette G. & Mary L. Zampini. 2008. Phonology and second language acquisition. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Jarvis, Scott & Aneta Pavlenko. 2007. Crosslinguistic influence in language and cognition. London: Routledge.

Keating, Patricia A., Michael J. Mikoś & William F. Ganong III. 1981. A cross-language study of range of voice onset time in the perception of initial stop voicing. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 70. 1260–1271.

Kellerman, Eric. 1987. Aspects of transferability in second language acquisition. Nijmegen: Katholieke Universiteit te Nijmegen PhD thesis.

Lisker, Leigh & Arthur Abramson. 1964. A cross-language study of voicing in initial stops. Word 20. 384–422.

Llama, Raquel, Walcir Cardoso & Laura Collins. 2010. The influence of language distance and language status on the acquisition of L3 phonology. International Journal of Multilingualism, 7 (1). 39–57.

Maddieson, Ian. 1997. Phonetic Universals. In William J. Hardcastle & John Laver (eds.), The Handbook of Phonetic Sciences, 619–639. Oxford: Blackwell.

Major, Roy. 1990. L2 acquisition, L1 loss, and the critical period hypothesis. In Jonathan Leather & Allan James (eds.), Proceedings of the 1990 Symposium on the Acquisition of Second Language Speech: New Sounds 90, 14–25. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam Press.

Major, Roy. 1995. Native and nonnative phonological representations. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching 33 (2). 109–128.

Odlin, Terence. 1989. Language transfer: Cross- linguistic influence in language learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Poedjianto, Ninik. 2002. Production of word-initial /p/-/b/ in Indonesian English. Paper presented at the 2002 BAAP Colloquium, University of Newcastle upon Tyne, 25–27 March 2002.

Pyun, Kwan-Soo. 2005. A model of interlanguage analysis – the case of Swedish by Korean speakers. In Britta Hufeisen & Robert J. Fouser (eds.), Introductory readings in L3, 55–70. Tübingen: Stauffenburg Verlag.

Ringbom, Hakan. 1987. The role of the first language in foreign language learning. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Schmidt, Anna Marie. & James Emil Flege. 1996. Speaking rate effects on stops produced by Spanish and English monolinguals and Spanish/English bilinguals. Phonetica 53. 162–179.

Shahidi, A.H. & Aman Rahim. 2011. An acoustical study of English plosives in word initial position produced by Malays. The Southeast Asian Journal of English Language Studies, 17 (2). 23–33.

Sharwood-Smith, Michael. 1983. On first language loss in the second language acquirer: Problems of transfer. In Susan M. Gass & Larry Selinker (eds.), Language transfer in language learning, 222–231. Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

Sharwood-Smith, Michael. 1994. Second language learning: Theoretical foundations. London: Longman.

Sypiańska, Jolanta. 2013. Quantity and quality of language use and L1 attrition of Polish due to L2 Danish and L3 English. Poznań: Adam Mickiewicz University. Unpublished PhD dissertation.

Tremblay, Marie Claude. 2007. L2 influence on L3 pronunciation: Native-like VOT in the L3 Japanese of English-French bilinguals. Paper presented at the Satellite Workshop of ICPhS XVI, Freiburg, Germany, 3–4 August.

Vildomec, Veroboj. 1963. Multilingualism. Leyden: Sythoff.

Waniek-Klimczak, Ewa. 2011. Aspiration and style: A sociophonetic study of the VOT in Polish learners of English. In Magdalena Wrembel, Malgorzata Kul & Katarzyna Dziubalska-Kolaczyk (eds.), Achievements and perspectives in SLA of speech: New Sounds 2010, 303–316. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Williams, Sarah & Björn Hammarberg. 1998. Language switches in L3 production: Implications for a polyglot speaking model. Applied Linguistics 19 (3). 295–333.

Wissing, Daan & Rigardt Pretorius. 1996. Voiceless plosives of Tswana: An acoustic-perceptual investigation. South African Journal of Linguistics 14 (Supplement 34). 83–102.

Wissing, Daan. 2005. Aspiration of English voiceless stop consonants in Southern Sotho: A case study. South African Journal of African Languages, 25 (3). 189–205.

Wrembel, Magdalena. 2010. L2-accented speech in L3 production. International Journal of Multilingualism 7 (1). 75–90.

Wrembel Magdalena. 2011. Cross-linguistic influence in third language acquisition of voice onset time. In Wai-Sum Lee and Eric Zee (eds.), Proceedings of the 17th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences 17–21 August 2001, CD-ROM, 2157–2160. Hong Kong: City University of Hong Kong.

Wrembel, Magdalena. 2012a. Foreign accent ratings in third language acquisition: The case of L3 French. In Ewa Waniek-Klimczak & Linda R. Shockey (eds.), Teaching and researching English accents in native and non-native speakers, 31–48. Heidelberg: Springer.

Wrembel, Magdalena. 2012b. Foreign accentedness in third language acquisition: The case of L3 English. In Jennifer Cabrelli Amaro, Suzanne Flynn & Jason Rothman (eds.), Third language acquisition in adulthood, 281–309. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Wrembel, Magdalena. 2014. VOT Patterns in the Acquisition of Third Language Phonology. Concordia Working Papers in Applied Linguistics (COPAL) 5. 750–770.

Wunder, Eva-Maria. 2010. Phonological cross-linguistic influence in third or additional language acquisition. In Katarzyna Dziubalska-Kolaczk, Magdalena Wrembel & Magorzata Kul, Proceedings of the 6th International Symposium on the Acquisition of Second Language Speech: New Sounds 2010, 566–571. Poznań: Adam Mickiewicz University.