5 Differences in the perception of Englishvowel sounds by child L2 and L3 learners

1 Introduction

In recent years it has become widely acknowledged that the process of third language (L3) acquisition differs from the process of acquiring a second language (L2) in a number of important ways. Language learners who are already users of two languages are likely to bring a greater range of linguistic repertoires and competencies into the task at hand than those who have no previous experience with learning additional languages. When getting to grips with non-native phonologies, L3 learners may be more knowledgeable than L2 learners about phonetic–phonological articulatory rules and perception, and may also build on higher levels of phonological awareness (Gut 2010: 21). Such learners may have developed, for instance, greater awareness about their native language (L1) sound system and how it differs from that of other languages. They may also have developed specific approaches to noting and articulating new sounds. With greater cognitive flexibility2 relating to additional linguistic knowledge and competencies, L3 learners can thus be expected to pursue a quantitatively and qualitatively different path to the acquisition of additional phonologies than L2 learners.

Although well-established theoretically, empirical evidence for the assumed facilitating effect of bilingualism on learning additional phonologies has been scarce and inconclusive. One of the related questions that remains unanswered is whether the advantage for a bilingual engaged in acquiring a new phonology can be related to her broadened experience with a non-native sound system, or whether specific experience with a language that is phonologically similar to the target language is required for such an effect to become evident. The present study seeks to add to this understudied area by examining the different patterns of cross-linguistic vowel perception in native Polish child L2 and L3 learners of English after about three years of residence in Ireland.

Romana Kopečková, University of Münster

2 Effects of bilingualism on L3 phonologicalcompetence

Additive effects of bilingualism on general aspects of L3 proficiency have been demonstrated in a great number of studies conducted in bilingual communities and classrooms around the world (for a review, see Cenoz 2003). When it comes to the realm of L3 phonology, however, only a few studies have addressed the long-standing question of whether knowledge of two (or more) sound systems is better than one, and these studies present rather mixed results. For instance, Enomoto (1994) reported a superior performance by adult bilinguals over English-speaking monolinguals in a discrimination task involving Japanese single and geminate stops (“iken” versus “ikken”), theorising that bi/multilinguals possess higher levels of cognitive flexibility and that they search for structure in perceptual tasks more than monolinguals do. Similarly, Cohen, Tucker and Lambert (1967) found English-French bilinguals to be significantly more accurate than their monolingual counterparts at producing a range of initial consonant clusters that did not occur in either of their languages. In a study conducted within the same large-scale research project but with elementary school children, Davine, Tucker and Lambert (1971) also documented enhanced perceptual sensitivity for combinations of sound sequences on the part of the bilinguals, although this time the improved ability extended only to the sounds of the children’s second language rather than to novel sounds in general. More recently, research by Bialystok, Luk and Kwan (2005) produced findings along similar lines: Hebrew-English and Spanish-English bilingual children performed significantly better than English monolingual children did on a phoneme counting task and non-word decoding task; but in the same study the performance of Chinese-English bilinguals was comparable to that of English monolinguals, suggesting that not all bilingual groups benefited from their previous language learning experience. Patihis, Oh and Mogilner (2013) attempt to explain these findings through their own research with speakers of different language backgrounds –bilingual Spanish, bilingual Armenian and trilingual speakers discriminating stop consonants in Korean. The Spanish-English bilinguals performed like English monolinguals and less accurately than the Armenian-English bilinguals in the study, suggesting that the bilingual advantage may not lie so much in greater cognitive flexibility but rather in positive L1/L2 transfer. This would coincide with the findings by Werker (1986), who noted no significant differences between bi/trilinguals and monolinguals discriminating phonetic distinctions non-existent in their languages, i.e. Hindi retroflex/dental syllable and Thomson glottalised velar/glottalised uvular syllable. Beach, Burnham and Kitamura (2001) reported the same results with monolingual English and bilingual Greek-English adults discriminating unfamiliar Thai bilabial stop contrasts. The conclusion drawn from these studies was that specific rather than broad linguistic experience is needed to facilitate perceptual ability in an L3. However, even this is open to further enquiry, since in a recent study with primary and secondary school children learning English in the Basque country, Gallardo del Puerto (2007) demonstrated that various levels of bilingualism do not necessarily predict L3 perceptual competence, neither globally nor with respect to individual phonemes. This suggests that other factors may play a more prominent role in L3 phonological acquisition than has been found for other domains of L3 learning. As noted by Cabrelli Amaro (2012: 36), a great deal of more research is clearly needed to determine to what extent knowledge of previous sound systems facilitates L3 phonological acquisition, and what factors are the key determinants in the process.

3 Models of multilingualism and non-nativespeech learning

Recent years have seen an increased interest in the exploration of the complex process of additional language learning, as a result of which a number of models of multilingualism have been developed with the aim to pinpoint and explain the specifics of language learning in multilingual contexts. One such influential model is Hufeisen’s Factor Model (2005), which identifies the various linguistic and learning factors involved and shows how these are inter-related in time. At the outset of language acquisition, neurophysiological factors (e.g. general language aptitude and age) and learner external factors (e.g. type/ amount of input and learning environments) are posited as decisive influences for the learner. At the point of learning their first foreign language, affective (e.g. motivation, attitudes and perceived distance between languages) and cognitive factors (e.g. language awareness and learning strategies) together with the linguistic characteristics of the learner’s L1 and L2 modulate the learning process, providing the bilingual with the foundation for multilingualism. It is the foreign-language specific factors, however – the individual foreign language learning experiences and strategies, engagement in L2 to L3 transfer, and interlingual connections – that are considered in the model to be unique for the language learning process of the multilingual. These can vary across and within learners, with each learner developing a specific combination of factors with time. Multilingualism is thus seen in this model as a dynamic process, which will not be fundamentally different beyond L3 learning thanks to the specific foreign language factors, which may change in mode but will not be complemented by any other – fundamentally different – factors upon L4/Ln encounter. In the context of the present investigation, it is thus to be noted that even though manifold factors will interact in complex ways in both L2 and L3 phonological acquisition, the latter will be characterised in particular by extended perceptual search for interlingual connections.

A more general, albeit compatible, picture of the process of L3/Ln acquisition is portrayed in Herdina and Jessner’s Dynamic Model of Multilingualism (2002). This perspective conceives of multiple language learning as a dynamic, complex, non-linear, open, and self-organising process with a tendency to settle in “attractor states”. No seemingly stable characteristics of the learner are regarded as absolute, but are seen rather, as being the result of an internal self-organisation settling into a preferred attractor state. During L3 phonological acquisition, for example, competing L2 perceptual targets may function as attractors in the learner’s target phonology; given the availability of such resources as the learner’s motivation and attitudes towards her languages, input, and feedback, these attractors may be weakened over time, while others such as target-like L3 production may be strengthened. The language systems in the multilingual mind are posited to be interdependent, with the key factor being the M(ultilingualism)-factor, referring to “an emergent property, which can contribute to the catalytic or accelerating effects in L3 acquisition (. . .) a heightened level of metalinguistic awareness in multilingual learners and users, which can be seen as a function of interaction between the systems” (Jessner 2013: 179). In this model, as in Hufeisen’s Factor Model, multilingualism is thus closely related to the concept of cross-linguistic influence, whereby transfer phenomena interact with other variables of dynamic nature.

The basic notion of transfer is fundamental to most current models of non-native phonological acquisition. Although largely developed with an L2 learner in mind, and thus not explicitly asserting the possibility of transfer from an L2 to an L3, models such as the Perceptual Assimilation Model (PAM) (Best 1995; Best and Tyler 2007) and the Speech Learning Model (SLM) (Flege 1995, 2007) provide a useful account of the learning process during non-native segmental acquisition. Both models maintain that L2 perceptual processing is guided by the basic cognitive mechanism of equivalence classification, whereby comparisons between the target phonetic realisations and the phonological organisation of the learner’s L1 (and possibly additional languages in the context of L3 phonological acquisition) are drawn. While engaged in the comparison and identification of phonemic patterns in the face of the inherent sensory variability found in the ambient language, learners will find certain non-native segments especially challenging. The models predict that the more similar the target sounds are to the L1 counterparts, the more difficult they will be for the learner to perceive accurately. This is because the learner will judge such phones as being a realisation of L1 segments, due to her extensive experience with perceiving a range of variants to realise the specific sounds. In contrast, sounds that are novel are predicted to be perceived with ease, since these have no counterparts to be compared with and assimilated to (Flege 1987). If this process is extended to L3 acquisition, L3 sounds that are similar to those of the learner’s L1 (and possibly L2) can then be expected to be more difficult to categorise accurately. Child learners are predicted in Flege’s model to be advantaged in this learning process, because their L1 sound system may not constitute as strong an “attractor” of the target sounds as is the case for an adult learner with a well-established inventory of L1 phonetic categories (Baker et al. 2008; Kopečková 2012). With growing experience in learning the target language, all learners are nevertheless able to refine their perception of the specific speech sounds, although not necessarily to a native-like level of accuracy (Flege and MacKay 2004). What seems to be an important point of generalisation here is that learning an additional sound system requires a degree of re-sensitisation of perceptual skills and a more conscious attention to specific phonetic contrasts. It may be hypothesised that L3 phonological acquisition builds on such a re-sensitisation to new phonetic contrasts; it remains to be shown whether this learning process is stimulated by general cognitive flexibility or rather L1/L2 transfer, facilitated by previous exposure to specific segments similar to and/or different from those occurring in the target language.

The focus of the present exploratory study is on the role of bilingualism in the acquisition of L3 phonology. In particular, this study examines cross-linguistic perception of English vowel sounds by Polish children living in Dublin, with the aim of addressing the following research questions:

- 1) Will Polish L3 child learners exhibit different perceptual mapping of English vowel sounds than their L2 counterparts?

- 2) If so, can the different patterns of cross-linguistic perception be related to their L2(s)?

Addressing these questions is hoped to enhance our understanding of one of the key issues discussed in this volume, the question of whether there is a fundamental difference between learning English phonology as a second and as a third/additional language.

4 Irish English and Polish vowel sounds

In this study, vowel sounds were chosen for investigation because of their suitability for testing language-specific sound categorisations, and also because of the different phonological structures of the Polish and Irish English vowel inventories, which lend themselves to use in a test of the predictions offered by the PAM and SLM discussed above.

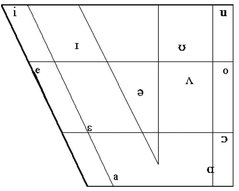

Standard descriptions of the Irish English vowel inventory (Hughes, Trudgill, and Watt 2005; Wells 1982) distinguish twelve vowels and three diphthongs: two front tense vowels /i/, /e/, three front lax vowels /ɪ/, /ε/, /a/, one central vowel /ə/, three back lax vowels /ʊ/, /ʌ/, /α/, and three back tense vowels, /u/, /o/, and /ɔ/. The diphthongs are comprised of /aɪ/, /aʊ/, and /ɔɪ/ sound combinations. The most salient vowel sound of Irish English is /ʌ/ (as in but), which is typically produced as a mid-centralised, back, somewhat rounded vowel, and as such is more precisely transcribed as  (Kallen 1994) or

(Kallen 1994) or  (Hickey 2008). In the variety of English spoken in Dublin, there exists free variation between neutralisation of the vowel (i.e. its realisation as /ʊ/) and /ʌ/ (Hughes, Trudgill, and Watt 2005: 115).

(Hickey 2008). In the variety of English spoken in Dublin, there exists free variation between neutralisation of the vowel (i.e. its realisation as /ʊ/) and /ʌ/ (Hughes, Trudgill, and Watt 2005: 115).

Figure 1: Irish English vowel chart (Ní Chasaide 2001: 93)

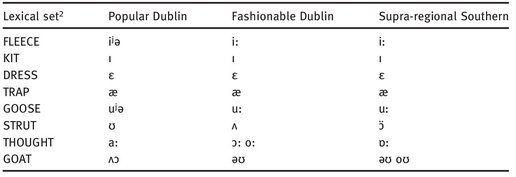

It is worth mentioning that the past two decades have seen changes in vowel sound realisations in Dublin English as a result of the changing socio-economic climate of Ireland’s capital city. Distinguishing between popular (local) Dublin English, a fashionable (cosmopolitan) variety of English spoken in the capital, and a supra-regional Southern (neutral) variety of Irish English, Hickey (2008) notes the following possible realisations of lexical sets in Dublin English:

Table 1: Lexical sets for Irish English vowels (Hickey 2008: 85) 3

As shown in Table 1, the largest variation in the realisation of Irish English vowels in today’s Dublin is thus likely to be occurring in the lexical sets of STRUT, THOUGHT and GOAT. In contrast, the phonological input to which the children in this study may have been exposed in terms of the FLEECE, KIT, DRESS and TRAP lexical sets appears fairly uniform, following the standard description of the Irish English vowel inventory (Figure 1).

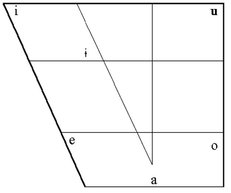

In comparison with Irish English, the Polish language vowel inventory is discernibly much smaller and lacking regional variation. Gussmann (2007: 2) identifies six oral vowels and two nasal nuclei: four front vowels /i/, /ɨ/, /ε/, /a/, two back vowels /ɔ/, /u/, and two mid vowels /ε/, /ɔ/, which are followed by a nasalised labio-velar glide, in some cases a nasalised palatal glide. The orthographic nasal vowels <ę and ą> are thus sometimes regarded as diphthongs rather than as typical nasal vowels. The Polish vowel chart, excluding the nasal vowels, is reproduced in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Polish vowel chart (Jassem 2003: 105)

As seen in Figure 1 and Figure 2, the English vowels /i/ and /ɪ/ are close in articulatory vowel space to Polish /i/ and /ɨ/, although Polish speakers are known to assimilate both sounds into a single Polish vowel /i/ (Szpyra-Kozłowska 2010). The vowel sounds /ε/, /u/ and /o/ can be regarded as very similar in both languages, albeit involving subtle acoustic differences (Sobkowiak 2003: 146–155). The specific Irish English /ʌ/ differs from any conceivable Polish sound, stretching between Polish /a/, /o/ and /u/. The vowel /æ/ does not exist in Polish either, and is realised half-way between Polish /e/ and /a/. The Irish English /əʊ/ is produced higher and more frontally in the oral cavity, and as such differs from Polish /o/ substantially.

To examine whether there exists a bilingual advantage in L3 speech perception, the present study included multilingual4 Polish children who were also learners of German, French, Irish and Spanish (see Table 3 below for specific language combinations). With the exception of Spanish, the other languages include expanded vowel sound inventories – like Irish English – when compared to Polish. They are all rich in front vowels, although English (and indeed Irish English, which is significantly influenced by the vowel backness of Irish phonology) appears unique among the languages in its somewhat back and unrounded series of vowels (Delattre 1965: 54; Wells 1982: 417–450). It remains to be shown whether the experience of these language constellations on the part of the L3 learners can suggest a broad-based or specific-based bilingual advantage.

5 The present study

5.1 Participants

A total of 8 children was recruited from a larger sample of participants in the Polish Diaspora Project (Singleton, Regan, and Debaene 2013) and closely matched on a number of key background variables, including on socio-economic background. As shown in Table 2, the Polish children were about 13 years old and had resided in Dublin for almost three years at the time of the study. Their first brief contact with English took place in Poland, however, in a classroom setting rather than in an immersion setting in Ireland. Neither of the children’s English learning environments involved any focused phonetic training. The children used Polish with their families on a daily basis and in a Polish weekend school on Saturdays. Their full-time education took place via English within the Irish post-primary educational system. When tested formally (Anglia Placement Test 2009), their proficiency in English ranged from beginner to upper-intermediate (see Table 3 below). They all reported a balanced use of English and Polish in their everyday life.

For the purpose of the present study, the children were divided into two subgroups depending on whether English was their sole additional language (L2 group) or whether they were learning English alongside one or more additional languages (L3 group). These included German, Irish, French and Spanish, all of which were being learned by the children as a foreign language in a formal learning setting for an average of two hours per week for each language. These additional languages were regarded by the Polish children as their much weaker languages. Designing the study on the basis of these sub-groups allowed the question of whether the same acquisition processes are at play when English phonology is learnt as an L2 or L3/additional language to be examined; albeit on a very small, limited scale given the size of the subject sample.

Table 2: Group characteristics of the participants in the study

| L2 group (N=4) | L3 group (N=4) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 12.75 (range: 12–14) | 12.75 (range: 12–14) |

| Age at arrival | 10.00 (range: 9–12) | 10.25 (range: 9–12) |

| Age of first English exposure | 9.00 (range: 8–10) | 9.75 (range: 9–10) |

| Length of residence in Dublin | 2.75 | 2.50 |

| L1 Polish with family | Yes | Yes |

| Attendance at Polish weekend school | Yes | Yes |

| Daily school instruction in English | Yes | Yes |

| Balanced use of English and Polish in everyday life | Yes | Yes |

| Additional languages | No | German (1) |

| Irish (1) | ||

| German & French (1) | ||

| German, French & Spanish (1) | ||

| Note: The mean and range values for age-related data and length of residence are given in years. | ||

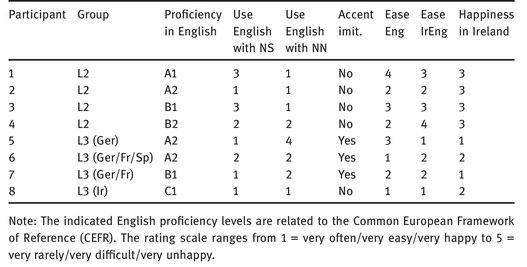

When it comes to the learners’ engagement with English and their attitudes towards the language, Table 3 shows that the L2 child learners used English with native speakers less frequently than the L3 group did, and in turn the L3 group reported less frequent contact with non-native speakers. Also, the L3 children seemed to enjoy imitating the (Irish) English accent; they found English easier to learn and Irish English easier to understand than L2 children did. They also expressed greater levels of happiness about living in Ireland than did their bilingual counterparts.

Table 3: Individual characteristics of the participants in the study

5.2 Instruments

This study was conducted within a larger research project, for which a battery of tasks was used to examine the children’s competence in the English language. This set of language tasks is described in detail in Kopečková (2012: 240–243). The test selected for the present research was a perceptual assimilation task, which employs a “fit index” metric conveniently combining data on cross-language identification and goodness of fit ratings into a single value. Weighting the identification scores by the goodness of fit ratings helps to raise the scores of those identifications that are considered good exemplars of the native category by the learner and, in turn, to lower the scores of those identifications that are selected because they have no good competitors.

The perceptual assimilation task tested the children’s judgement of cross-linguistic phonetic similarity in terms of eight (Irish) English vowels and six Polish vowels, placed within a /bVt/ word context (beat, bit, bat, bet, boat, bought, boot and but for English, and bity, byty, buty, bety, baty, and boty for Polish). The task was administered to the children twice and in two different orders; in each case, they first heard the English word and matched the vowel in the stimuli to one of the six Polish keywords shown on screen (or rather to the Polish vowel sound) to which they believed it was most similar. For example, when they heard the word beat, the task was to decide which Polish sound was most similar to English /i/ in that word. Second, the participants made goodness of fit judgements regarding the similarity of the English vowel they had just heard and the Polish vowel they had chosen, using a 7-point Likert scale, with a score of “1” indicating that the sounds were not at all alike and a score of “7” indicating that the sounds were a complete match. For example, it was predicted that the Polish children would rate /i/ in beat as very similar to the Polish vowel /i/ in bity. The children were encouraged to use the entire scale and to follow their first impression in completing the task. Each child listened to a total of 16 stimuli (8 items x 2) via loudspeakers and marked their responses into an answer sheet by circling their choices.

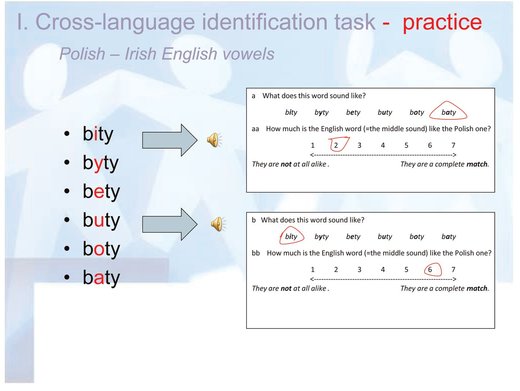

To ensure that the children understood the task, and to lend validity to the task, they were asked to read aloud the list of the Polish keywords from the screen and to concentrate on how “the middle sound” of the word sounded to them. Then the children underwent a brief practice session in which they were encouraged to discuss their first impressions about the stimuli, and were also offered visual prompts on screen with possible answers. They were reminded that it was important to approach this task bearing in mind that there were no “right” or “wrong” answers, and, accordingly, it was suggested to them that basing their answers on spontaneous impression was the best strategy. Figure 3 below depicts the screen that the children could see during the practice session.

The background information about the children’s language learning histories reported above was elicited by means of a pen-and-paper questionnaire administered either in Polish or English, depending on the children’s choice. In addition, the Polish children’s English proficiency levels were formally examined through a standardised placement test (Anglia Placement Test 2009) suitable for use with young learners and located within the general descriptive scale of the CEFR. The whole testing session took about 60 minutes to complete (out of which the perceptual assimilation task took about 10 minutes) and was organised in the children’s Polish school. The researcher interacted with the children in both English and Polish. This research approach – together with the fact that each session was conducted in pairs or groups of three – helped to create a relaxed environment for the children throughout the testing session.

Figure 3: Perceptual assimilation task: practice session screen

6 Results

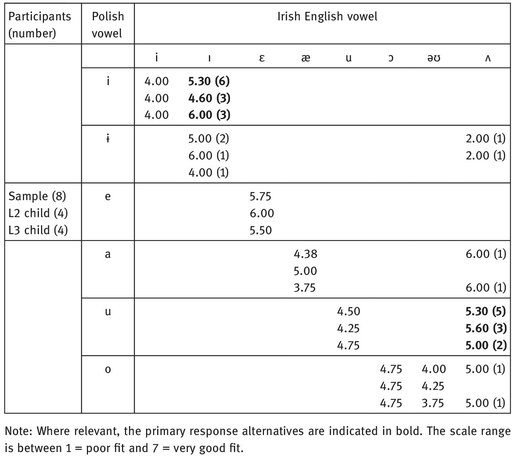

Analyses of the cross-language identification judgements revealed that the child L2 and L3 learners in this study selected the same Polish vowels as the primary response alternative in their classification of the tested Irish English sounds, while diffuse patterns were identified only in individual cases for the vowels /ɪ/ and /ʌ/. As shown in Table 4 below, all the children who participated in the study identified the English vowel /i/ (as realised in beat) as being closest to the Polish vowel /i/ (as realised in bity). In contrast, six of the eight children perceived the English /ɪ/ (as realised in bit) as being most similar to the same Polish /i/, while the remaining two children (one L2 learner and one L3 learner) found this English central vowel to be closer to the Polish /ɨ/ (as realised in byty). The English vowels /e/, /æ/ and /u/ (as in bet, bat and boot) were identified as corresponding, respectively, to the Polish /e/, /a/ and /u/ (as in bety, baty and buty). The Polish /o/ (as realised in boty) was perceived as relating to both /ɔ/ and /əʊ/ in English (as realised in bought and boat, respectively). The specific Irish English vowel /ʌ/ (as realised in but) was classified as Polish /u/ by the majority of the children, with one L2 child perceiving this vowel as being somewhat similar to the Polish /ɨ/ and two L3 children mapping the vowel into the Polish /a/ and /o/, respectively.

Table 4: Fit indices for tested Irish English vowels in terms of Polish vowels

The degree of similarity between the vowel sounds concerned was calculated by multiplying the proportion of responses receiving primary and secondary identification by the mean goodness rating for that identification, assuming that the higher the similarity rating (fit index) for the English vowel, the higher the perceived similarity between that vowel and a corresponding Polish sound. Overall, as seen in Table 4, in the top line of the three lines of responses for each Polish vowel, the English /ɪ/, /ε/, /u/ and /ɔ/ were considered by all the children to be good perceptual fits with the native Polish counterparts /i/, /e/, /u/ and /o/, with the mid front vowels in particular being perceived as good fits (fit index of 5.75 out of 7). Those learners who chose the primary identification for the specific Irish English vowel /ʌ/ as fitting Polish /u/ or /a/ rated these sounds as being fairly similar also. The remaining tested vowels /i/, /æ/ and the diphthong /əʊ/ were rated by the two groups of children conservatively in respect to the Polish vowel counterparts, i.e. at around point 4 on the 7-point scale.

Upon closer inspection of Table 4, notable differences5 can be observed for at least three mapping patterns shown in the L2 and L3 child learners’ performance on the perceptual assimilation task (see the second and third lines for the L2 and L3 participant groups, respectively). The L3 learners discerned a discrepancy between the English /æ/ and the Polish alternative /a/ to a greater extent than the L2 learners did, noting a fairly low perceptual fit between the two segments (fit index of 3.75 versus 5.00, respectively). The L3 learners were additionally more nuanced in distinguishing between the English minimal pair sounds /i/ and /ɪ/. Of note is the fact that they assimilated the English /ɪ/ into the Polish /i/ to a greater extent than the L2 learners did, but the overall pattern of distinction on the part of the L3 learners showed a clear disambiguation between the minimal pair sounds (with fit indices of 4 and 6, respectively, as compared to fit indices of 4 and 4.6 for L2 learners). The L3 learners’ nuanced differentiation between the English /ɔ/ and /əʊ/ as compared to Polish /o/ (fit indices of 4.75 and 3.75, respectively, and 4.75 and 4.25 for L2 learners) is also indicative of their greater perceptual accuracy as is their apparent search for a suitable category for the specific Irish English vowel /ʌ/ when offering viable /a/, /o/ and /u/ alternatives. Overall, therefore, the performance on the perceptual assimilation task by the two groups of Polish child learners in this small-scale study suggests a trend for a bilingual advantage in the perception of English as an L3. Further research is warranted, with an expansion in sample size and data points allowing for analyses with greater statistical power, and an examination of the development in the children’s further L3 perceptual learning.

7 Discussion

The results of the present study suggest that the two groups of Polish L2 and L3 child learners of English differed in their perception of similarities between the target vowel sounds and their L1 counterparts. The L3 learners performed with greater perceptual sensitivity, both in terms of segments and minimal pairs not existent in their L1 (e.g. /ʌ/ and /ɛ/ versus /æ/) and segments similar, albeit not identical, in their L1 (e.g. /ɛ/ and /u/). Given that the distinctions concerned occur in the L3 learner’s additional languages (German, French and Irish), it was impossible to strictly tease apart whether their perceptual faculty could be related to enhanced cognitive flexibility per se – facilitated by a general exposure to and use of their additional foreign languages – or rather to a specific experience with L2 segmental learning. Most recent research in the area has suggested that L3 learners may not necessarily possess greater flexibility than L2 learners in changing phoneme category boundaries, but rather that the former – if exposed to specific L1/L2 contrasts similar or identical to those in the target language – tend to apply narrow positive transfer, building on their greater awareness about specific interlingual connections. In a study with monolingual English, bilingual Spanish, bilingual Armenian and trilingual adults discriminating Korean as an unfamiliar language, Patihis, Oh and Mogilner (2013) showed that the advantage from early childhood non-English exposure or current bilingualism was specific only to languages with similar phonemic categories (such as Armenian with Korean as the target). In contrast, when data from the participants whose languages included similar contrasts to Korean were excluded, no significant differences were found between the monolingual, bilingual or trilingual participants on the phoneme discrimination task. This would be also suggestive of the performance by the multilingual children in this study who reported knowledge of both German and French. These L3 learners showed the most accurate perceptual mapping patterns, which may have been a result of a combined cross-linguistic influence (cf. De Angelis 2007: 21); apparently, their perception of cross-linguistic similarity was reinforced by the presence of near-identical phonetic features and contrasts existent in both their non-native languages (Delattre 1965: 51), resulting in what may be called “double positive transfer”. Such a combined cross-linguistic influence would seem to support a narrow L1/L2 transfer advantage in the perception of L3 phonemes, i.e. advantage related to the L3 learner’s specific exposure to similar kinds of phoneme distinctions in her languages and compliance with the basic mechanism of equivalence classification.

Additional variables were likely to mediate this bilingual advantage. In accord with the predictions of current models of multilingualism (e.g. Hufeisen 2005), the L3 child learners in this study were engaged in a qualitatively different learning experience than their L2 counterparts. Reporting more frequent contact with native speakers of Irish English and feeling at greater ease with living in the target language country, the L3 learners in this study seem to have been exposed to more meaningful phonological input and feedback (albeit not to explicit phonetic training) and identified with the target language more, all of which may have enhanced their perceptual skills. Indeed, as pointed out by Moyer (2013: 47), learner-specific factors inevitably operate alongside language-specific and context-specific factors during phonological development. The L3 learner’s distinct learning trajectories will vary and dynamically evolve, which is also likely to be one of the reasons why some studies with comparable groups of learners reported mixed results or results that conflict with those reported here (e.g. Gallardo del Puerto 2007).

While acknowledging the qualitative and quantitative difference between L3 and L2 phonological acquisitions (cf. Hoffmann 2001), this study suggests that both processes build on the basic cognitive mechanism of equivalence classification. Acquiring English segmental phonology as an L2 or as an L3/additional language do not appear to be fundamentally distinct phenomena in this regard, since the underlying mechanism of mapping the varied realisations of the target language into the existing categories is to guide both. With their extended phonetic-phonological repertoires, L3 child learners seem, however, to be in a better position to attune their perceptual processing of L3 speech, i.e. to re-sensitise and modify their perception of L3 sounds in the direction of the sound categories established during L1 and L2 acquisition.

8 Conclusion

The present exploratory study sought to add to the limited research into L3 phonology and the effects of bilingualism on L3 sound perception. More specifically, it addressed one of the pertinent questions posed in the current volume, i.e. whether there is a fundamental difference between learning English as an L2 and an L3 sound system. The findings of the present study, albeit based on a small sample of participants, suggest that both learning processes build on the basic cognitive mechanism of equivalence classification, which is modulated by the specific linguistic and non-linguistic experience of the learner. The interesting finding seems to be that a gradual change in the perceptual sensitivity of child L3 learners can occur in the context of balanced L1/L3 exposure and a concurrent learning of an L2 as a foreign language as early as after three years of residence in the target language country. In light of this finding, it is conceivable that young learners engaged in the acquisition of postcolonial varieties of English can similarly capitalise on their extended experience with learning additional sound systems, especially those which include specific phonemes similar to those in the target language.

Recruitment of closely-matched participants on key variables deemed important in multilingual speech learning remains one of the greatest challenges in further research in this understudied area of language acquisition. Use of varied methodological tools, which approximate natural phonological processing, will also be needed in any research effort to gain a better understanding of the way additional phonologies are learnt. In the current exploratory study only a limited number of participants and stimulus material were employed. It is important that further studies expand the sample sizes studied and examine language combinations and phonetic features which can tap as far as possible into the effect of specific versus non-specific multilingual linguistic experience on perceptual performance.

References

Anglia Placement Test. 2009. Anglia Examination Syndicate, Chichester University. http://www.anglia.org (accessed 21 January 2009).

Baker, Wendy, Pavel Trofimowich, James Emil Flege, Molly Mack & Randall Halter. 2008. Child-adult differences in second-language phonetic learning: The role of cross-language similarity. Language and Speech 51(4). 317–342.

Beach, Elizabeth Francis, Denis Burnham & Christine Kitamura. 2001. Bilingualism and the relationship between perception and production: Greek/ English bilinguals and Thai bilabial stops. The International Journal of Bilingualism 5 (2). 221–235.

Best, Catherine T. 1995. A direct realist view of cross-language speech perception. In Winifred Strange (ed.), Speech perception and linguistic experience: Issues in cross-language research, 171–204. Timonium, MD: York Press.

Best, Catherine T. & Michael D. Tyler. 2007. Nonnative and second-language speech perception: Commonalities and complementarities. In Ocke-Schwen Bohn & Murray J. Munro (eds.), Language experience in second language speech learning: In honor of James Emil Flege, 13–34. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Bialystok, Ellen, Gigi Luk & Ernest Kwan. 2005. Bilingualism, biliteracy, and learning to read: Interactions among languages and writing systems. Scientific Studies of Reading 9 (1). 43–61.

Cabrelli Amaro, Jennifer. 2012. L3 phonology: An understudied domain. In Jennifer Cabrelli Amaro, Suzanne Flynn & Jason Rothman (eds.), Third language acquisition in adulthood, 33–60. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Cenoz, Jasone & Fred Genesee. 1998. Psycholinguistic perspectives on multilingualism and multilingual education. In Jasone Cenoz & Fred Genesee (eds.), Beyond bilingualism: Multilingualism and multilingual education, 16–32. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Cenoz, Jasone. 2003. The additive effect of bilingualism on third language acquisition: A review. The International Journal of Bilingualism 7 (1). 71–87.

Cohen, Stephen P., G. Richard Tucker & Wallace E. Lambert. 1967. The comparative skills of monolinguals and bilinguals in perceiving phoneme sequences. Language and Speech 10 (3). 159–168.

Davine, M., G. Richard Tucker & Wallace E. Lambert. 1971. The perception of phoneme sequences by monolingual and bilingual elementary school children. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Sciences 3 (1). 72–76.

De Angelis, Gessica. 2007. Third or additional language acquisition. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Delattre, Pierre. 1965. Comparing the phonetic features of English, French, German and Spanish: An interim report. Heidelberg: Groos.

Enomoto, Kayoko. 1994. L2 perceptual acquisition: The effect of multilingual linguistic experience on the perception of a “less novel” contrast. Edinburgh Working Papers in Applied Linguistics 5. 15–29

Flege, James Emil. 1987. The production of “new” and “similar” phones in a foreign language: Evidence for the effect of equivalence classification. Journal of Phonetics 15 (1). 47–65.

Flege, James Emil. 1995. Second-language speech learning: Theory, findings, and problems. In Winifred Strange (ed.), Speech perception and linguistic experience: Issues in cross-language research, 233–277. Timonium, MD: York Press.

Flege, James Emil. 2007. Language contact in bilingualism: Phonetic system interactions. In Jennifer Cole & José Ignacio Hualde (eds.), Laboratory Phonology 9, 353–382. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Flege, James Emil & Ian R. A. MacKay. 2004. Perceiving vowels in a second language. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 26 (1). 1–34.

Gallardo del Puerto, Francisco. 2007. Is L3 phonological competence affected by the learner’s level of bilingualism? International Journal of Multilingualism 4 (1). 1–16.

Gussmann, Edmund. 2007. The phonology of Polish. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gut, Ulrike. 2010. Cross-linguistic influence in L3 phonological acquisition. International Journal of Multilingualism 7 (1). 19–38.

Hammarberg, Björn. 2010. The languages of the multilingual: Some conceptual and terminological issues. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching 48 (2/3). 91–104.

Herdina, Philip & Ulrike Jessner. 2002. A dynamic model of multilingualism: Perspectives of change in psycholinguistics. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Hickey, Raymond. 2008. Irish English: Phonology. In Bernd Kortmann & Clive Upton (eds.), Varieties of English 1: The British Isles, 71–104. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Hoffmann, Charlotte. 2001. Towards a description of trilingual competence. The International Journal of Bilingualism 5 (1). 1–17.

Hufeisen, Britta. 2005. Multilingualism: Linguistic models and related issues. In Britta Hufeisen & Robert J. Fouser (eds.), Introductory readings in L3, 31–46. Tübingen: Stauffenburg Verlag.

Hughes, Arthur, Peter Trudgill & Dominic James Landon Watt. 2005. English accents and dialects: An introduction to social and regional varieties of English in the British Isles, 4th edn. London: Hodder Arnold.

Jassem, Wiktor. 2003. Polish. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 33 (1). 103–107.

Jessner, Ulrike. 2013. On multilingual awareness or why the multilingual learner is a specific language learner. In Miroslaw Pawlak & Larissa Aronin (eds.), Essential topics in applied linguistics and multilingualis: Studies in honor of David Singleton, 175–184. Heidelberg: Springer.

Kallen, Jeffrey L. 1994. English in Ireland. In Robert Burchfield (ed.), The Cambridge history of the English language volume 5: English in Britain and overseas: Origins and development, 148–196. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kopečková, Romana. 2012. Differences in L2 segmental perception: The effects of age and L2 learning experience. In Carmen Muñoz (ed.), Intensive exposure experiences in second language learning, 234–255. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Moyer, Alene. 2013. Foreign accent: The phenomenon of non-native speech. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ní Chasaide, Ailbhe. 2001. Phonetics. In David Little (ed.), Introduction to language study, 70–100. Dublin: CLCS Trinity College Dublin.

Patihis, Lawrence, Janet S. Oh & Tayopa Mogilner. 2013. Phoneme discrimination of an unrelated language: Evidence for a narrow transfer but not a broad-based bilingual advantage. The International Journal of Bilingualism 0 (0). 1–14. http://ijb.sagepub.com/content/early/2013/02/21/1367006913476768.full.pdf+html (accessed 30 October 2013).

Singleton, David, Vera Regan & Ewelina Debaene (eds.). 2013. Linguistic and cultural acquisition in a migrant community. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Sobkowiak, Włodzimierz. 2008. English phonetics for Poles, 3rd edn. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Poznańskie.

Szpyra-Kozłowska, Jolanta. 2010. Phonetically difficult words in intermediate learners’ English. Paper presented at the 6th International Symposium on the Acquisition of Second Language Speech New Sounds 2010, Adam Mickiewicz University Poznań, 1–3 May.

Wells, John C. 1982. Accents of English 2: The British Isles. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Werker, Janet F. 1986. The effect of multilingualism on phonetic perceptual flexibility. Applied Psycholinguistics 7 (2). 141–155.