CHAPTER 1

Overview of US Middle Market Corporate Direct Lending

This book focuses on the investment opportunity in US middle market corporate direct lending (or direct loans), a large and rapidly growing segment of the global private debt market. Direct loans are illiquid (nontraded) loans made to US middle market companies, generally with annual earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) ranging from $10 million to $100 million. These middle‐market corporate borrowers are of an equivalent size to those companies found in the Russell 2000 Index of medium and small stocks but, in aggregate, they represent a much larger part of the US economy compared to the Index. The US corporate middle market includes nearly 200,000 individual businesses representing one‐third of private sector gross domestic product GDP and employing approximately 48 million people.1

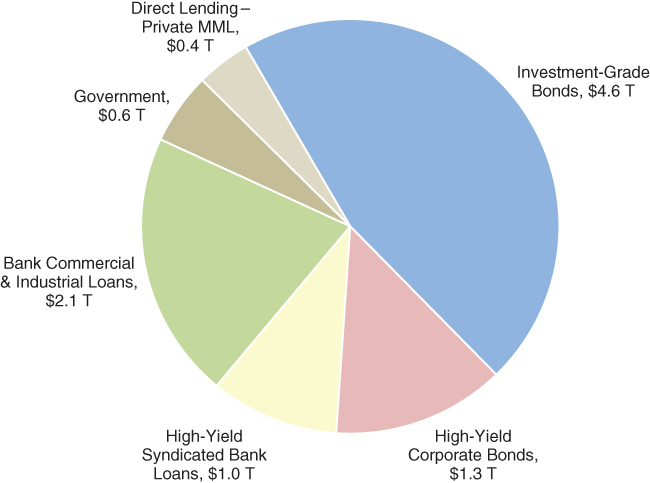

Exhibit 1.1 illustrates where direct corporate lending fits within the multiple sources of long‐term debt financing provided to US companies as of December 31, 2017. Long‐term debt financing to US companies totaled approximately $10 trillion. By comparison, equity financing to US companies totaled approximately $24 trillion.2

EXHIBIT 1.1 Breakdown of the $10 trillion US corporate debt market.a

Traded, investment‐grade bonds represent almost one half of corporate debt financing, but this debt is issued by the largest US companies. High yield (non‐investment‐grade) bonds and bank loans represent one‐half of investment‐grade bond issuance. These companies are also larger, with EBITDA over $100 million where scale allows them to access the traded broker markets. Bank commercial lending, the market where direct lenders compete, is $2.1 trillion in size. The US government, through government‐sponsored enterprises (GSEs) and agencies, makes direct loans to companies in generally depressed or subsidized industries, such as agriculture. These loans are estimated at $0.6 trillion.

The size of the direct lending US middle market loans is estimated to equal $400 billion, based upon Federal Reserve data and other sources. While small compared to traditional sources of corporate financing, the direct loan market has significant potential for growth if it can continue to claim market share from the bank C&I loan business.

THE RISE OF NONBANK LENDING

Commercial banks have been the traditional lenders to US middle market companies. The Federal Reserve reports that US banks hold roughly $2.1 trillion in commercial and industrial (C&I) loans on their balance sheets, which is mostly comprised of middle market business loans. Banks also make loans to larger companies that are not held on their balance sheets. Instead these larger loans are sold and syndicated across many investors, which are subsequently traded as private transactions in the secondary market. These traded loans are also referred to as broadly syndicated loans (BSLs), also known as leveraged loans. The size of the leveraged loan market is roughly $1 trillion, or half the size of bank C&I loans. These larger, traded bank loans have become very popular among institutional and retail investors through pooled accounts, mutual funds, and exchange‐traded funds (ETFs), providing a yield advantage to investment‐grade bonds while maintaining daily liquidity.

Loans to middle market companies are too small for general syndication and therefore are held by the originating bank. The investment opportunity in middle market loans for nonbank asset managers principally came about as an outcome of the 2008–2009 global financial crisis (GFC), and the years following, when increased capital requirements and tighter regulation on corporate lending made holding middle market corporate loans more expensive and restrictive for most banks. As banks decreased their lending activity, nonbank lenders took their place to address the continued demand for debt financing from corporate borrowers.

Direct loans are typically originated and held by asset managers that get their capital from private investors rather than bank deposits. Asset managers are regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission and are not subject to the same investment restrictions placed upon banks. Investors are primarily institutional rather than retail, representing insurance companies, pension funds, endowments, and foundations. Retail investors have had access to direct loans mainly through publicly traded business development companies (BDCs), which are discussed in Chapter 12.

There are approximately 180 asset managers in the United States that invest in direct middle market corporate loans. Many of them began direct lending during and soon after the GFC and recruited experienced credit professionals from banks that either went into bankruptcy (Bear Sterns, Lehman Brothers) or had their activities sharply curtailed. GE Capital, the financing arm of General Electric, also faced important financial problems during the GFC. GE Capital, through its subsidiary Antares, was at one point the largest US nonbank lender. The subsequent exodus of credit and deal professionals provided significant intellectual capital to the nascent nonbank lending industry.

While banks continue to hold a key advantage over asset managers by having a low cost of funds (i.e., bank deposits), this is offset by higher capital requirements, which ties up shareholder equity, and restrictions on the type of business loans that can be made by banks and the amount of leverage they can offer to borrowers. While these regulations may ease over time, particularly with the more business‐friendly Trump administration, which could entice banks to re‐enter the market, the loss of talent during and after the GFC, and subsequent weakening of banks' relationships with borrowers, makes this a challenging prospect.

Finally, the growth of nonbank lending has also been helped by a new type of corporate borrower, the private equity sponsor. Private equity has seen steady growth since it began over 30 years ago but its role in the US economy has picked up significantly since the GFC, particularly in the middle market. These private equity–sponsored companies are professionally managed, use debt strategically in financing, and require timeliness, consistency, and flexibility from lenders as well as attractive pricing. The advent of direct lending by professional asset managers has given private equity sponsors an alternative and preferred source of financing. Currently roughly 70% of direct loans are backed by private equity sponsors.

DIRECT LENDING INVESTORS

Investor interest in middle market direct lending has been driven by several factors. First and foremost is their attractive yields, ranging from 6% for the least risky senior loans to 12% for riskier subordinated loans. These yields compare with 2–3% for liquid investment‐grade bonds, as represented by the Bloomberg Barclays Aggregate Bond Index, a widely used investment grade bond index, and 4–5% for broadly syndicated non‐investment‐grade loans, as represented by the S&P/LSTA Leveraged Loan Index, an index used to track the broadly syndicated loan market.

Investors are also attracted to direct loans because coupon payments to lenders (investors) are tied to changes in interest rates and have relatively short maturities (typically five‐ to seven‐year terms, which are typically refinanced well before the end of the loan term). The floating‐rate feature is particularly important in periods of rising interest rates. Interest rates for direct loans are set by a short‐term base rate (or reference rate) like three‐month London Interbank‐Offered Rate (Libor) or US Treasury bills, plus a fixed coupon spread to compensate for longer‐term default risk and illiquidity. Bank loan investors will see their yields increase as interest rates rise through quarterly adjustments to their base rate. In many respects, rising interest rates are beneficial for direct loan investors.

Conversely, most bond funds primarily hold fixed‐rate securities, whose yields do not adjust to rising interest rates. Instead rising rates cause bond prices to fall, in line with the duration of the bonds. A typical bond mutual fund has a five‐year duration, a measure of average bond life. In this example, if interest rates for bonds with a five‐year weighted average duration rise one percentage point, the bond fund will experience a 5% decline in value (five‐year duration multiplied by 1% interest rate increase), offsetting any benefit from increased yield. Direct loans have only a three‐month duration and a one‐percentage‐point increase in rates will have only a temporary 0.25% (25 basis point) price decline. The direct loan yield will reset at the next calendar quarter and its value will return to par.

Direct loans generally have a shorter life than their five‐ to seven‐year maturities suggest, which can be both good and bad. The average life of a direct loan has averaged approximately three years, much shorter than their stated maturity due to their being refinanced from corporate actions, such as acquisition of the borrower by another company, or prepayment by the borrower to get a lower interest rate. The good news is that direct loans are not as illiquid as their maturity suggests. At a three‐year effective life, one‐third of the loans pay off every year, which makes their liquidity profile attractive compared to private equity funds, whose effective life is seven to nine years on average.

However, if prepayments result from the borrower refinancing at a lower interest spread, then the lender is potentially worse off in terms of future yield, which causes the price of the loan to decline. Most loan documents include prepayment penalties, which go to the lender (investor), but these do not always provide sufficient compensation for the foregone income.

Most US middle market direct corporate loans are backed by the operational cash flow and assets of the borrower. Companies generally borrow from one lender whose security in case of default is all borrower assets but for trade payables and employee claims. The lender is said to have a senior, first‐lien claim in default. Some companies have additional lenders whose claims in default come after the senior lenders have been paid off. These are subordinated, second‐lien lenders who receive additional interest income for the greater risk of loss they take.

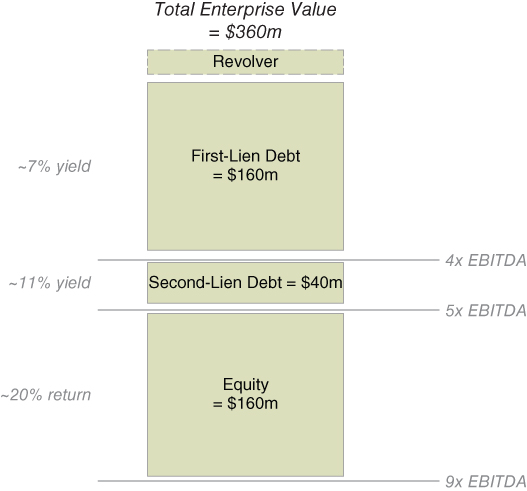

Direct Lending Illustration

Exhibit 1.1 illustrates a balance sheet of a middle market company with $40 million in EBITDA. The company is worth $360 million, or nine times (9x) EBITDA. Companies generally have a small amount of revolving credit for working capital purposes. “Revolvers” allow the borrowing company the right to draw capital as needed, paying an interest rate on amounts drawn as well as a fee on undrawn capital. These can be direct loans provided by an asset manager but, since they entail a high degree of servicing relative to the interest rates charged, are typically provided by a bank.

Most debt capital in our example is provided by a senior, first‐lien, direct loan equal to $160 million, which equals 4x EBITDA. This direct loan has first claim on assets in bankruptcy excepting trade receivables, which would satisfy any revolver amount outstanding.

The company also has a $40 million second‐lien loan in place equal to 1x EBITDA but subordinated to the first lien and revolver debt. Historically, banks provided the senior first‐lien loan and nonregulated, nonbank institutional investors provided the subordinated second‐lien loan. Direct lending has increasingly left the nonbank asset manager to provide all debt financing, perhaps with the sole exception of the revolver, for middle market companies.

Companies can also have unitranche loans in place that combine first‐ and second‐lien loans into one. Unitranche loans have become more common in recent years as borrowers seek a single source of debt financing.

Finally, equity financing equal to $160 million provides the remaining capital that completes this company's balance sheet. Equity has historically been provided by the owner operator but increasingly it is the private equity sponsor that provides equity capital and who also puts in place professional managers to run the business.

The type of lending illustrated in Exhibit 1.2 is often referred to as leveraged finance because the amount of debt represents a higher multiple (leverage) of EBITDA than might be typical of investment‐grade debt of a large multinational company. Rating agencies typically assign a non‐investment‐grade rating to direct loans. This is due to the higher debt leverage multiple, the relatively small size of the borrower, and the private ownership of the company, as opposed to public listing. Consequently, direct loan performance is more closely correlated to non‐investment‐grade junk bonds, or broadly syndicated bank loans, rather than investment‐grade corporate bonds found in indices like the Bloomberg Barclays Aggregate Bond Index.

EXHIBIT 1.2 Capital structure of a $40 million EBITDA company.

With this overview as an introduction, Chapter 2 provides a detailed description of the historical investment characteristics of US middle market direct loans.