A number of significant developments made the mid-1950s a major turning point for European football. In politics, a thaw in the relations between East and West made it possible for teams from opposite sides of the Iron Curtain to play each other, a change that was symbolised by two major events in 1954: the World Cup final in Switzerland, which brought together West Germany and Hungary, and the participation of 18 teams from Eastern and Western Europe in the 1954 International Youth Tournament. Inter-European club football was also seeing a renaissance, with several ideas for club competitions being launched, including one from France’s sports daily L’Équipe in December 1954. Last, but by no means least, 1954 also saw the founding of a European football organisation that would encourage the further Europeanisation of the game.

5.1 UEFA: A New Body for European Football

When the new statutes adopted by FIFA’s extraordinary congress in November 1953 came into force, in February 1954,1 Europe’s associations had to come together to select their six representatives (two vice-presidents and four ordinary members) on FIFA’s executive committee. This meeting also provided an opportunity to constitute a more formal body, as Ottorino Barassi had suggested in the spring of 1952 (see Sect. 2.3), in which national associations could discuss issues relating to European football.

The three members of the standing committee appointed at the meeting of European associations in Zurich in May 1952—Barassi, José Crahay and Henri Delaunay—took steps to organise this discussion.2 Delaunay, the committee’s secretary, contacted the 31 associations FIFA considered to be European,3 but he was unsure where the borders of European football lay and had to ask FIFA’s secretary general, Kurt Gassmann, whether Turkey could participate in the meeting. Gassmann consulted FIFA’s leaders before replying, on 19 March 1954, that Turkey should be placed in the future Asian grouping because the Turkish FA’s headquarters were in Ankara, on the Asian side of the Bosporus.4 As a result, Turkey was not invited to the meeting of European associations, which the standing committee scheduled for 12 April 1954, in Paris, alongside a match between France and Italy.

Out of the 31 associations Delaunay invited to Paris, 22 attended the meeting5 and 9 sent apologies for their absence.6 The presence of the English and Scottish associations was a sign that their leaders were gradually rallying to the idea of creating closer ties between Europe’s associations, unlike the countries of Eastern European, whose reluctance to go down this road was shown by the absence of all the Soviet bloc associations except Hungary and Czechoslovakia. Both countries’ associations supported Gustav Sebes’ bid for a FIFA vice-presidency, but Czechoslovakia’s Josef Vogl expressed his opposition to forming a European group. Henri Delaunay responded to this comment by reminding Vogl that the issue had already been decided at the meetings in Zurich, Paris and Helsinki. However, this was not entirely accurate: as I indicated in Chapter 2, the agreement reached during these meetings was to hold talks, not to appoint common representatives to FIFA’s executive committee. In fact, whether and how a European body should be formed was still subject to much debate that the Paris meeting failed to settle, as Thommen noted a few days later in a letter to Rimet.7 What is more, the delegates were also unable to agree on which of the 11 applicants (from 11 national associations) should be chosen to fill Europe’s six seats on FIFA’s executive committee. The need to turn down five of the applicants made this a highly sensitive issue, so Stanley Rous moved to postpone the decision until the eve of the next FIFA congress, due to be held in June in Switzerland, in order to allow further reflection. Rous’ motion was designed to avoid conflict between the associations by giving them time to conduct the informal discussions needed to form alliances and reach compromises. It also shows how much the experience of working within FIFA since the interwar years had taught Europe’s leaders about recognising and avoiding possible bones of contention (Vonnard 2018a, see Sect. 1.2).

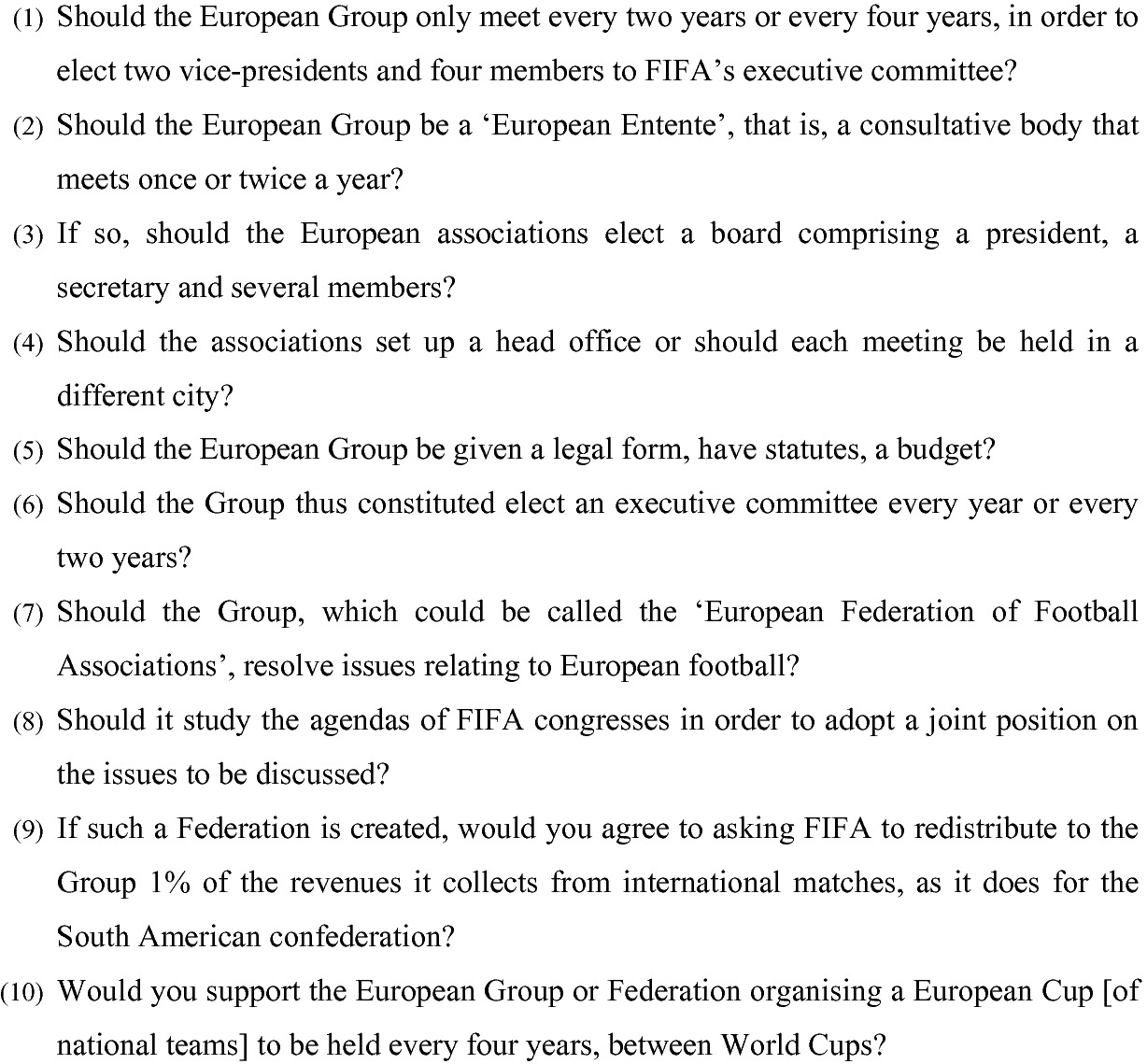

Questionnaire sent to European associations in May 1954

(Source Freely translated from the French. Minutes of the Belgian FA executive committee, 24 April 1954. BNA, URBSFA, executive committee [1953–1954])

Delaunay sent out the questionnaire with a cover letter in which he described the three options available to the national associations. First, they could create a body whose main purpose would be to elect Europe’s members on FIFA’s executive committee, as set out in Article 17 of FIFA’s new statutes. Second, they could set up a more ambitious organisation, referred to as a ‘consultative entente’, whose occasional meetings would provide a forum in which to exchange views and express wishes.9 Third, they could choose the most comprehensive option of creating a group with a legal form, similar to the South American confederation, which Delaunay explicitly named. He also reminded them that whichever option they chose, the resulting body would remain subordinate to FIFA.

The response rate was very high, as 22 of the 31 associations contacted completed the questions, 4 (Bulgaria, East Germany, Iceland, Soviet Union) said they would prefer to wait before giving their answers, and only 5 (Albania, Hungary, Poland, Wales, Romania) failed to acknowledge receipt of the document.

A summary of the associations’ replies,10 drawn up by the standing committee, showed that most of the associations were in favour of creating a formal entity, similar to the second option proposed by Delaunay. This entity’s main task would be to elect representatives to FIFA’s executive committee and to meet once a year to discuss issues relating to European football. The favoured way of doing this was to appoint an executive body and to set up a head office at its secretary general’s place of residence. Each committee meeting and annual general meeting would be held in a different European city as a way of involving as many associations as possible. Hence, in the spring of 1954, Europe’s national associations decided to cross the Rubicon and form a continental entity.

- a.

Address all questions concerning football in Europe.

- b.

Review the agendas of FIFA congresses.

- c.

Bring together the different viewpoints of FIFA members on issues on the congress’ agenda and, if possible, agree on common positions on these issues.

- d.

Appoint the two vice-presidents—without the participation of the British associations or the USSR—and the four members of FIFA’s executive committee who, under Article 17 of the FIFA Statutes, are eligible for election by the European associations.14

Whereas the first point gave the future grouping the right to deal with issues relating to European football, the other three emphasised the intention to remain close to FIFA and highlighted the fact that creating a European entity was primarily a response to the changes in FIFA’s statutes. Hence, the organisation the European associations were asked to consider was one with limited prerogatives.

The next meeting, in Basel on 15 June 1954, was attended by the leaders of 25 associations,15 who quickly agreed to create a European Grouping of Football Associations. They then moved on to the issue of who should be elected to FIFA’s executive committee. As Rous had hoped, delaying the decision from the April meeting had enabled the associations to come to an agreement, with the result that every candidate was elected to either FIFA’s executive committee or the European Grouping’s executive committee. The leaders appointed to the European executive committee were (in alphabetical order): José Crahay, Henri Delaunay, Joseph Gerö, George Graham, Ebbe Schwartz and Gustav Sebes. Thus, the Basel meeting, which had taken place in ‘a more friendly atmosphere than the Paris meeting [of 12 April]’,16 formally founded a representative body for European football, which was officially recognised by FIFA’s executive committee on 21 June 1954.17

The European Grouping’s priority was to get the national associations to approve the statutes drawn up by the standing committee. With this in mind, the new executive committee was charged with preparing a final draft for presentation to the Grouping’s first congress, scheduled for 1955. The executive committee used its first meeting, held immediately after the FIFA congress, to appoint Ebbe Schwartz as president and Henri Delaunay as secretary general (see Sect. 6.1).18 It also drew up a timetable for drafting the new statutes and agreed to meet again, in Copenhagen in October 1954, in order to continue the discussions. In the meantime, Delaunay corresponded regularly with the leaders of Europe’s national associations as he continued working on the statutes.19

As planned, the executive committee met again in Copenhagen, on 29–30 October, where they discussed the draft statutes and decided how best to consolidate the existence of the new confederation, which they named the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA). According to Gasparini (2011, p. 53), there were two advantages to using the term Union, rather than Grouping. First, Union is more legally binding and infers stronger links between the organisation’s members. Second, it suggests a coalition in which each association remains autonomous, rather than delegating its power to a central authority. This important point mirrored the measures FIFA took in the 1930s to ensure it did not interfere in the internal affairs of its member associations (Vonnard 2018a, see Chapter 1).20 The executive committee removed the sentence: ‘[the organisation] will not provisionally adopt any official character’ from the draft statutes and decided that would adopt a legal form ‘in the country where the Group’s registered office is located’.21 Finally, it set an annual membership fee of 250 Swiss francs per association (based on the 260 Swiss francs fee the associations paid to FIFA each year)22 and agreed to send a registration form to every association. These decisions, which would be discussed at UEFA’s first congress, in Vienna in March 1955, show that the executive committee wanted to act swiftly to give UEFA solid roots.

UEFA’s elite also looked at measures it could use to develop European football, such as launching a European competition for national teams, thereby following the South American model (see Chapter 7). A competition such as this would have the added advantage of enhancing UEFA’s legitimacy and the small amount of money raised from international matches would help cover the cost of executive committee meetings and the travel expenses of delegates attending UEFA’s congress.

The delegates at UEFA’s Vienna congress were keen to develop the organisation, but, as discussed below (see Sect. 5.4), they rejected the idea of setting up a competition for national teams. More positively, they unanimously approved, with virtually no amendments, the new statutes put forward by the executive committee, decided to expand the executive committee from six to eight members, and agreed to UEFA sponsoring a match between Great Britain and the rest of Europe in the summer of 1955—inspired by the ‘FIFA game’ that were played between England and a FIFA team in 1938, 1947 and 1953 (Dietschy 2015; Vonnard 2019a)—in order to celebrate the Northern Ireland FA’s 75th anniversary. The congress also proved itself to be a valuable forum for discussing a wide variety of questions relating to European football by addressing several other issues, including sports betting,23 the broadcasting of matches and the possibility of drawing up a calendar for international matches.

Work to solidify UEFA’s existence continued through May 1955 with the opening of a dedicated bank account in Paris and the creation of a letterhead bearing the acronym ‘UEFA’.24 The executive committee then moved on to the match between Great Britain and the ‘Rest of Europe’ that was due to be played that summer. This match would benefit UEFA in two main ways. First, the revenues it received from the game (a small percentage of the total) would boost the organisation’s finances. Second, putting together a ‘Rest of Europe’ team to play a Great Britain team, was an excellent way of strengthening ties between national associations. The match was a success, attracting 58,000 spectators and reporters from several European sports dailies. Although some UEFA member associations were not represented on the pitch, this was due to circumstances rather than a deliberate decision by UEFA’s executive committee. The game included players from Austria, Denmark, Belgium, France, Italy, Portugal, Sweden, Yugoslavia and the four British associations. Players from several other countries declined to take part in the match, to the disappointment of the British associations, which, according to L’Équipe, ‘regret[ed] the absence of the Hungarians, [and] especially the Russians, Germans and Spaniards’.25 By bringing together the entire continent’s football community, the match encouraged further rapprochement between the countries of Europe, and including as many countries as possible enabled UEFA to demonstrate its pan-European nature.

UEFA standing committees (early 1959)

Commissions | Creation date | Number of membersa |

|---|---|---|

Executive | 1954 | 9 |

Champion Clubs’ Cup | 1956 | 5 |

Appeals | 1956 | 3 |

Finance | 1957 | 4 |

Youth | 1957 | 5 |

Cup of Nationsb | 1956 | 5 |

Television | 1958 | 3 |

Coordinating the work of these commissions was a considerable task for the secretary general, especially as of October 1958, when the executive committee asked to be sent a copy of each committee’s minutes so it could stay abreast of progress.30 The secretary general also contributed to many other tasks, such as developing projects for new competitions, drawing up an international calendar, ensuring consistent standards of refereeing, maintaining relations with other continental confederations and producing the UEFA Bulletin, which had expanded to include articles on all aspects of European football. On the eve of the 1958 congress, the executive committee met without Delaunay, who was asked not to attend, to discuss ways of alleviating the secretary general’s workload. Several solutions were put forward, particularly by José Crahay, the Belgian FA’s and Belgian Olympic Committee’s secretary general, who was sympathetic to Delaunay’s situation and insisted he needed assistance. To this end, Crahay suggested appointing an administrative secretary who could take on some of Delaunay’s work and who should be assisted by the subordinate staff essential to UEFA’s smooth running. The congress that followed these discussions also decided that it was time for UEFA to employ a general secretary and to establish a permanent headquarters by asking the French FA to provide three new offices.31 The executive committee sent its request to the French FA in the autumn of 1958 and quickly received a positive reply. However, UEFA’s leaders felt that the work required to expand the French FA’s premises accordingly would be too expensive.32 On 5 March 1959, a sub-commission composed of UEFA’s finance committee and UEFA’s president, Ebbe Schwartz, met the president of the French FA, Pierre Pochonnet, who was told that UEFA had decided to leave Paris and set up a separate headquarters.

As a result, the executive committee started looking for a home for UEFA, finally settling on Switzerland, which had the advantages of being ‘neutral’,33 thereby facilitating relations with countries from both sides of the Iron Curtain, and of having a well-developed banking system that would allow UEFA to manage its finances more effectively. In fact, problems with its bank account in Paris had led UEFA to open an account in Switzerland in 1957, in order to facilitate financial exchanges with its member associations.34 Finally, the fact that FIFA and many other international organisations, including the IOC and FIFA but also the European Broadcasting Union (see Sect. 6.3), were based in Switzerland is also likely to have influenced UEFA’s choice.

UEFA’s move to Switzerland ended Delaunay’s future as secretary general because he did not want to move his family (he had two young children at the time).35 According to Jacques Ferran, ‘Pierre Delaunay did not have the ambition or the desire to give up French football to go there, so we knew in advance he would say [no], that he [would] prefer to keep [his position at] the French Federation’.36 The need to appoint a new secretary general appears to have been another factor in UEFA’s choice of Switzerland for its headquarters, because the man they favoured for the position in the spring of 1959 was FIFA’s deputy secretary, Hans Bangerter, who had made it clear he wanted to stay in Switzerland.37 In his autobiography, the influential English leader Stanley Rous—who was appointed in 1959 UEFA vice-president—said that he had known Bangerter for several years and held him in high regard. Of course, Bangerter would have preferred to take over as FIFA’s secretary general from the ageing Kurt Gassmann, who was expected to retire soon (he eventually retired in 1961). However, according to Rous (1979, pp. 134–135), Bangerter was too young to have a real chance of obtaining a position that tended to be awarded in recognition of a long career in football administration. On the other hand, Rous felt that Bangerter’s dynamism would be a significant asset for the young UEFA.

Bangerter was only 30, but he already had a lot of experience in sports administration. After studying at a technical school in Bern, he worked at the Federal Gymnastics Centre in Magglingen, where he was responsible for welcoming foreign visitors and course participants. This is where he met Rous. His appointment as FIFA’s deputy secretary in 1953 allowed him to work with the experienced Kurt Gassmann and to forge closer relations with European football’s most influential leaders, such as Barassi and Thommen. Bangerter had three other qualities that made him an excellent candidate for the position of secretary general of an international organisation. First, he was from Switzerland, whose neutrality made him less liable to accusations of bias by either side of the political divide and made it easier for him to travel throughout Europe. Second, he had a strong sense of diplomacy, a crucial asset for this type of position (Quin 2012; Vonnard 2017), which he had cultivated during his time in Magglingen and at FIFA. Third, he spoke and wrote all three of UEFA’s official languages (English, French and German) fluently.

By the summer of 1959, UEFA was ready to move from Paris and Bangerter’s appointment as secretary general sealed the decision to relocate to Switzerland. Now, it was a matter of finding suitable premises. When other avenues failed,38 Bangerter, with help from Ernst Thommen, managed to secure offices for UEFA in the House of Sports currently being built in a Bern suburb, which would also house the Swiss FA’s new headquarters (Vonnard 2019c).

In order to avoid offending Pierre Delaunay and the French FA, and to ensure a smooth transfer of responsibilities to the new general secretary, the executive committee proposed adding another seat to its board, so UEFA’s members would have ‘the opportunity to elect Pierre Delaunay to the executive committee as a member’.39 This proposal was accepted at an extraordinary UEFA congress in December 1959, which also approved a motion to move the organisation’s headquarters to Switzerland by 16 votes to 9, with 3 abstentions. The congress’ minutes do not provide further details of this vote but, according to an article in L’Équipe by Jacques Ferran, the countries of Eastern Europe, Greece and Portugal wanted to keep the headquarters in Paris.40 Their objections to the move were explained by Yugoslavia’s Mihailo Andrejevic, who felt that the issue had been pushed through by the executive committee without being formally discussed by the national associations.

The administrative decisions taken in Paris solidified UEFA’s position. Moreover, the secretariat was growing rapidly, as Bangerter recruited three administrative secretaries, Ilse Schmidlin, Suzanne Otth and Ursula Krayenbuehl (Tonnerre et al. 2019), to help with the work. It was also becoming more professional, as can be seen in UEFA’s official documents, which now followed standardised formats (with precise headings and numbered pages) and systematically included drafting dates and signatures.

international sports betting;

drawing up a calendar of international matches;

establishing a training camp for coaches;

defining a category of matches for promising players;

organising the broadcasting of matches.

Moreover, UEFA’s annual congresses provided a forum for around 60 delegates representing approximately 30 member associations. Like FIFA’s congresses, these gatherings were also social occasions that helped strengthen the ties between the leaders in attendance. For example, all the delegates at the 1955 congress in Vienna visited the grave of Joseph Gerö, UEFA’s first vice-president, who had passed away at the end of 1954. This ceremony projected an image of a united European organisation that commemorated its dead, which was strongly reflected in the speech given beside Gerö’s grave.41 Finally, from the very beginning UEFA had helped national associations take part in international competitions, either by providing financial support for team travel, especially in the case of the International Youth Tournament, or by facilitating the organisation of matches by standing as guarantor for any eventual deficit (as in 1958, when Luxembourg, a small association with limited resources, hosted some games of the International Youth Tournament).42 As part of its efforts to improve the standard of European football, the executive committee decided in March 1960 to set up a course for coaches and trainers, which would be overseen by executive committee member and former Hungarian national team coach Gustav Sebes.43

These actions had enabled UEFA, in just five years, to establish itself as a significant player in the development of European football. At the same time, it had shown itself willing to test the geographical boundaries of European football.

5.2 Where Do UEFA’s Borders Lie?

Since the interwar period, the demarcation lines of European football had been set by the World Cup qualifiers (Vonnard 2018a, see Sect. 1.1). However, the creation of a European grouping gave this issue new importance, especially with respect to the position of Turkey, which had applied for UEFA membership in 1955. Turkey was keen to join UEFA because, compared with playing in Asia, where football was still relatively undeveloped, playing in Europe would help Turkey raise the standard of its football. In addition, Turkish football had historical links with many European countries and the country had regularly played teams from southeast Europe in the Balkan Cup since becoming affiliated to FIFA in 1923 (Breuil and Constantin 2015, p. 594). In the early 1950s, Turkey began playing countries in Western Europe, including West Germany, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland, and was included in the European section of the World Cup qualifiers, while Turkey’s youth team had competed in the 1953 and 1954 International Youth Tournaments. As a result, by September 1955 Kurt Gassmann was able to note that Turkey played ‘most of [its] international matches […] against European associations’.44 Finally, the structure of the Turkish FA and the decisions its leaders took, particularly with regard to legalising professional football (in 1952), were similar to those of its European counterparts.

These factors suggest that Turkey should be considered part of the ‘Europe of football’, an opinion shared by Özgehan Senyuva and Sevecen Tunç, for whom Turkey’s being part of UEFA was ‘a natural thing’ (2015, p. 575). More broadly, Turkey’s involvement in European football was consistent with the Turkish government’s desire to be part of the emerging Europe. To this end, Turkey had joined the Council of Europe in 1949 and aimed to participate in the development of economic Europe (Vaner 2001). UEFA formally discussed Turkey’s affiliation at its first official congress in Vienna in 1955.

UEFA’s executive committee debated Turkey’s membership application on the eve of the congress and decided to ask the congress to express its view. The delegates voted in favour of Turkey’s application, thereby enabling ‘the Turkish Association to be provisionally registered in the European Grouping, pending FIFA’s approval’.45 The congress also approved affiliation requests from Iceland, Greece and Poland, thereby increasing UEFA’s membership to 31 associations. Turkey’s affiliation was a more complex issue, but the warm reception its request received from UEFA’s member associations shows that numerous leaders already considered Turkey to be part of Europe, at least in football terms. UEFA’s president, Ebbe Schwartz, opened the discussion by endorsing Turkey’s affiliation and by reading a supporting letter from Yugoslavia’s Mihailo Andrejevic and Greece’s Constantin Constantaras. Their support was due both to the close footballing ties these countries had enjoyed with Turkey since the 1920s and to the favourable geopolitical context that had been generated when Turkey signed political-economic-military alliances with these two countries in August 1954 (Oikonomidis 2011, p. 506).

In their letter, Andrejevic and Constantaras pointed out that the Turkish FA’s sporting activities had ‘always been carried out within the framework of the European continent’.46 This was also Turkey’s main argument, whose football executives highlighted the fact that Turkey had never been part of Asian football. However, UEFA’s member associations were not all completely in favour of Turkey’s affiliation. Sir Stanley Rous briefly looked back on the debate in the book commemorating UEFA’s 25th anniversary (1979, p. 79), but without identifying the dissenting voices and the nature of their objections. Nevertheless, most of UEFA’s member associations supported Turkey and the congress recommended asking FIFA to endorse the Turkish FA’s affiliation. A few months later, the Turkish FA’s president, Hasan Polat, laid out his association’s case in a letter to FIFA in which he highlighted UEFA’s position that ‘the Turkish FA should be considered an Association belonging to this Union’.47 The ball was now in FIFA’s court. Leaving the final decision to FIFA seems to have been a way for UEFA’s member associations to dispose of a troublesome issue, especially as they had received another thorny request in the form of a membership application from the Israeli FA.48

Although the Israeli leaders put forward some of the same arguments as their Turkish counterparts, Israel’s request was more difficult for FIFA to deal with49 for three main reasons. First, Israel’s position on the international scene was controversial and diplomatic relations with its Arab neighbours had been severed following the 1948–1949 Arab-Israeli war, which led to Israeli independence. Tensions with its neighbours were to peak once again in 1956 due to the outbreak of the Suez crisis. These events prevented Israel ‘having sports relations with the closest Asian associations’.50 Therefore, Israel did not apply to join UEFA purely for sporting reasons; it was also motivated by political factors that prevented it finding opponents among its immediate neighbours.

Second, there was also tension between Israel and certain European countries with which it did not have diplomatic relations, notably Germany. In addition, the United States’ support for Israel automatically led the countries of the Eastern Bloc to oppose it (Claude 2008), which is why Israel tried to make as much political capital as it could from its two 1956 Olympic Games qualifying matches against the Soviet Union (Harrif 2009). These diplomatic issues raised the question of whether admitting Israel would create problems within UEFA. What is more, Israel was a very young country, having come into existence in 1948 only, so, even though it had quickly been integrated into the international sports scene,51 it did not have a long tradition of playing football in Europe. As a result, it could not rely on significant support from UEFA’s member associations, unlike Turkey.

The third reason was the question of whether Israel could be considered part of Europe. Where Europe’s boundaries lie is debatable, but the definition adopted by UEFA’s executive committee stems from a nineteenth-century geographical conception52 which places Israel firmly outside Europe. Turkey, however, can be considered to belong to Europe because (a small) part of the country—the area around Istanbul—is within Europe. Israel, on the other hand, has no physical connection with Europe and was therefore considered part of the Middle East. Consequently, Israel differed greatly from Turkey in terms of its political situation, its (limited) footballing ties with Europe and its geographical location, and therefore had a much weaker case for being granted UEFA membership.

On 14 August 1955, UEFA’s executive committee finally ruled that it ‘does not accept [Israel’s application], but decided, before taking a final decision, to seek FIFA’s opinion’.53 The minutes of this meeting do not provide any justification for this decision, but FIFA’s subsequent discussions with UEFA shed light on its position. FIFA’s executive committee examined Israel’s, Turkey’s and Cyprus’ (which had also applied to join UEFA) requests at its meeting of 17–18 September 1955. Gassmann, commenting on the meeting’s agenda, felt it was time for the executive committee to make a decision on an issue that he saw as unequivocal: ‘geographically and politically speaking, [these] associations belong de facto and de jure to the Asian continent. Both federations have their headquarters in the capital of their country. To consider them as European associations would be to deny the obvious’.54

By ‘geographically speaking’, Gassmann was referring to the fact that both countries’ associations had their headquarters outside Europe, as the Turkish FA was based in Ankara, which was considered to be part of Asia. What he meant by ‘politically speaking’ is less clear, although he was probably referring to Turkey having its seat of government in Ankara, and therefore in Asia. Gassmann had made this point to Henri Delaunay in April 1954, when he asked him if Turkey could be invited to the discussions on creating a European grouping.55 Gassmann’s position may also have been influenced by footballing considerations that he does not mention, as the newly created Asian confederation would benefit from having the particularly dynamic Turkish and Israeli FAs as members. Hence, FIFA may have felt that depriving the Asian confederation of these two associations would work against the goal of boosting the game in the Near and Middle East. However, UEFA’s door was not entirely closed to Turkey, Israel and Cyprus, because FIFA’s secretary general gave UEFA the right to include them in its competitions, if it so wished. FIFA was also prepared to issue special authorisations, for example, to take part in the International Youth Tournament—created in 1948 (see Sect. 2.1)—especially given the absence of such an event in Asia. As a final point, Gassmann noted that the distribution of qualifying groups points for the World Cup is based on economic and sporting considerations, as well as geographical location, thereby implying that these three countries could sometimes be included in the European zone.

FIFA’s executive committee applied the criteria set out by Gassmann and decided not to ‘comply with these requests since the countries of these three associations are undoubtedly part of the Asian continent’.56 On 20 September 1955, Gassmann wrote to all three associations informing them that they were indisputably part of Asia.57 UEFA’s executive committee took note of FIFA’s ruling at its meeting on 18 March 1956, where it agreed to follow FIFA’s advice in the case of Israel, but to contest it in the cases of Cyprus and Turkey. To this end, it requested permission to put the issue to the next FIFA congress, which could then decide ‘clearly on the situation of these countries vis-à-vis the European Union’.58 This request confirms that UEFA saw a big difference between Turkey and Israel, a view that was reiterated at the 1956 UEFA by a member of the Portuguese delegation, Joao Figueira, and which appears to have been shared by the vast majority of Europe’s football executives. Figueira’s argument that the Turkish FA should be able to join the confederation of its choosing because the country spans two continents, led UEFA’s president and secretary general to propose ‘that the European Union confirm its recognition of Turkey’s national association, [so] this association can enjoy all its rights as a UEFA member’.59 However, this was not enough to persuade FIFA to change its stance.

The Turkish FA tried to negate FIFA’s position by actively participating in UEFA’s activities, regularly attending its congress and, from 1958–1959, sending its national champion to take part in the Champions Clubs’ Cup, which had been created in 1955. Similarly, Turkey’s national team was one of the 17 teams that took part in the first edition of the European Cup of Nations, in 1958. The following year, FIFA’s executive committee finally accepted the Turkish FA’s request to be included in the European qualifying zone for the 1962 World Cup. Thus, Turkey had become a ‘virtual member’ of UEFA, to adopt the expression Peter Beck used to describe the British associations’ position vis-à-vis FIFA in the 1930s (2000).

According to Senyuva and Tunç (2015, p. 575), the main opponent of Turkey’s accession to UEFA was Gassmann, FIFA’s secretary general. This being said, although Gassmann was indeed reluctant to see Turkey become part of UEFA, the decisive factor appears to have been FIFA’s conception of Europe’s boundaries, rather than Gassmann’s personal point of view, as the Turkish FA was allowed to join UEFA when it moved its headquarters from Ankara to Istanbul in 1962.60 On the contrary, no progress was made in the case of Israel. FIFA’s executive committee refused to consider a new request from the Israeli FA in 1958, as it arrived after the statutory deadline for inclusion on the congress agenda. Consequently, Israel continued to be considered part of Asia (Dietschy 2020b, p. 32). Two years later, it was UEFA’s executive committee that refused Israel’s request to include the winner of its national championship in the Champion Clubs’ Cup, again on the grounds of the country’s ‘geographical situation’.61

Israel’s and Turkey’s62 requests are interesting because they throw light on UEFA’s conception of the ‘Europe of football’, which was mainly based on a nineteenth-century geographical definition of Europe (Pécout 2004). This conception of Europe’s borders left a certain amount of leeway for incorporating Turkey into Europe, but it made it much more difficult to consider Israel a European country. It was within this territory that European football developed and that UEFA began setting up competitions, starting with a club tournament: the European Champion Clubs’ Cup.

5.3 Creating Competitions for Clubs

UEFA’s former deputy secretary general, Markus Studer, wrote in 1998 that UEFA had been founded to organise competitions (1998, p. 98). However, setting up an international sport organisation does not automatically lead to the creation of competitions. FIFA, for example, waited almost 25 years before organising its own tournament (Eisenberg et al. 2004; Dietschy 2010, see Chapter 2). At UEFA, only one of the six goals in the draft statutes presented to its first congress, in Vienna, explicitly addressed competitions, stating that UEFA reserved the right ‘to organise at its convenience and at least every four years a European Championship for which [UEFA] alone will be competent to set the rules and conditions’.63 The congress delegates even went as far as to reject the motion to create a European Cup of Nations, thereby showing that launching competitions was not at all a priority for them (see Sect. 5.4). However, Markus Studer’s comment is not entirely unfounded, because organising competitions very quickly became UEFA’s main focus. What was the reason for this shift?

Pan-European sports competitions were quite rare during the first half of the twentieth century. In fact, the only sports to set up European championships before World War II were boxing (launched in 1924) (Loudcher and Day 2013) and athletics (launched in 1934) (Roger and Terret 2012). This started to change in the mid-1950s, when many sports began discussing projects for new European competitions (Dufraisse et al. 2019). Basketball, for example, created an inter-city cup.64 Football was a major contributor to this dynamic, with several actors (heads of national associations, club executives, journalists) proposing major competitions, especially for clubs. Two ambitious projects were launched almost simultaneously in the mid-1950s: the Inter-Cities Fairs Cup and a European cup for clubs.

The Inter-Cities Fairs Cup, a tournament between ‘scratch teams’ representing cities which had hosted major international fairs, was the brainchild of Barassi, Rous and Thommen, who conceived the event as a way of building new synergies between European football and business (Vonnard 2019a, pp. 1032–1033). Rous noted in his memoirs that the event was also intended to foster a new spirit of cooperation in the post-war period, through football’s ability to overcome old rivalries and create new friendships (1978, p. 145).

The Inter-Cities Fairs Cup was officially launched on 4 June 1955 with a match between Basel XI and London XI. Twelve teams took part: Basel XI, FC Barcelona, Birmingham City, Cologne XI, Frankfurt XI, Leipzig XI, London XI, FC Lausanne-sport, Inter Milan, Staevnet, Vienna XI and Zagreb XI.65 Difficulties in scheduling matches led to this first tournament taking three years to complete, but it was still a success.66 As an indication of its importance, the tournaments’ annual congress brought together numerous national association leaders and influential European clubs. However, Barassi, Rous and Thommen knew the football world well enough to realise the importance of not stepping on the toes of the organisations in charge of European football (see Chapter 2), primarily FIFA, but also the young UEFA. One way they did this was by involving only city teams, whose lack of official status meant they did not come under the auspices of national and international football associations.

The promoters of the second project, a European cup for clubs, did not take this precaution. It was a far more ambitious proposal in terms of the number of teams involved, as the aim was to create a European cup between 16 clubs from 16 different countries. The competition was first mooted on 15 December 1954, by Gabriel Hanot, a senior football journalist at L’Équipe.67 The history of the European Cup has been studied in great detail by some scholars (see notably Vonnard 2012 and for a summary see Vonnard 2014), so I will concentrate on UEFA’s takeover of the project rather than describe the whole process involved in launch the competition.

Hanot’s idea combined the new possibilities offered by air travel and by the introduction of floodlighting into stadiums, which meant mid-week evening matches could be played throughout the year. His proposal would also help meet both the clubs’ need for new sources of revenues in order to finance professional football and the sports press’s eagerness for new events to cover (Montérémal 2007). As a result, he quickly obtained support from several major European clubs and influential sports newspapers (Bola in Portugal, La Gazzetta dello Sport in Italy, Les Sports in Belgium, Marca in Spain).

If clubs, newspapers, and even national or professional leagues, can bypass the control and authority of the national associations, of FIFA and possibly of the statutory groups [Europe] has set up, the very existence of national associations may be put at risk, especially when it comes to such [a competition].70

In May 1955, UEFA’s executive committee asked its FIFA counterpart for permission to take over the event and for the title ‘Europe’ to be reserved for UEFA.71 Claiming the exclusive right to include the word ‘Europe’ in a tournament name was a strong sign that UEFA wanted to exert a monopoly over European football. FIFA’s executive committee approved UEFA’s request and set three conditions for the event: clubs must gain their national association’s consent before taking part; the word ‘Europe’ should be used only for matches involving national teams72; UEFA must manage the competition.

As soon as the committee set up by the clubs and journalists handed over the reins, on June 1955, UEFA’s executive committee asserted its authority by renaming the event the European Champion Clubs’ Cup. Although there was not enough time before the competition’s first edition, scheduled for the coming September, to change the clubs involved, which had been chosen by L’Équipe’s journalists, it was decided that future editions of the tournament would be between the national champions of all UEFA’s member associations.

Taking over the Champion Clubs’ Cup was crucial to UEFA’s development for a number of reasons (Vonnard 2016). First, it gave UEFA a new task: organising the first pan-European football tournament. FIFA’s executive committee approved UEFA’s rules for the competition at its meeting of 17–18 September 1955. It also asked UEFA to take over the Fairs Cup, whose first edition was already underway.73 This request shows that UEFA was beginning to be seen as the main organiser of European competitions. Running the Champion Clubs’ Cup not only gave greater weight to leading members of UEFA’s executive committee, such as Crahay, Delaunay and Schwartz, who had campaigned for UEFA to set up competitions (especially the European Cup of Nations), it also increased UEFA’s legitimacy with its member associations. As a result, associations that had not been represented at the meeting in Paris called by the Cup’s initiators, Hanot and Ferran, quickly put forward clubs from their countries to take part in the competition. This was the case for CNAD Sofia (Bulgaria), Dudelange (Luxembourg), Gwardia Warsaw (Poland), Dinamo Bucharest (Romania) and Spartak Sokolovo Prague (Czechoslovakia), as well as Galatasaray Istanbul, even though its national association (Turkey) was not a UEFA member (see Sect. 5.2).74

Second, the Champion Clubs’ Cup—whose successful first edition ensured it continued the following year—helped finance UEFA’s activities, as the new rules introduced for the competition’s second edition, in 1956–1957, allocated 1% of the gross revenue from every match and 5% of the gross revenue from the final to UEFA.75 In his 1954–1955 report, UEFA’s secretary general noted to his satisfaction that more than 800,000 spectators attended the 29 Champion Clubs’ Cup matches, that is, an average of 28,000 spectators per match.76 Demand for tickets for important matches far exceeded the capacity of the stadiums, as is illustrated by the 1956–1957 quarter-final between CDNA Sofia and Red Star Belgrade, when the Bulgarian club received 400,000 ticket requests for the 40,000 places available in its stadium.77 According to France Football, more than two million spectators attended Champion Clubs’ Cup matches during the 1959–1960 season, an average of 41,000 spectators per match. Only six matches were played in front of less than 10,000 spectators, allowing the article to conclude: ‘everywhere, now [the Champion Clubs’ Cup] is known and prized. It attracts crowds everywhere it goes’.78 The additional revenues UEFA earned from the competition enabled it to expand its activities, especially in the field of training (for referees and coaches), in the late 1950s and beyond.

The third contribution resulted from the fact that administering the Champion Clubs’ Cup forced UEFA to expand its structure. The competition’s first edition had been organised by UEFA’s executive committee, but it quickly became apparent that this task would be better accomplished by a separate body. Consequently, a permanent commission was set up to organise the tournament, starting with the second edition, in 1956–1957. This was one of UEFA’s first permanent commissions. Interestingly, its members were all men who were active in UEFA, namely Crahay, Sir George Graham and Augustin Pujol. The commission played a mostly technical and administrative role, conducting draws for matches, deciding on the match schedule and the dates and locations of the finals, and answering questions from the clubs. In parallel with establishing this body, the competition regulations were substantially revised and set out in 16 articles covering participants’ rights and obligations, the competition’s seasonal limits and recommendations on the refereeing of matches.

The Champion Clubs’ Cup not only strengthened UEFA’s existence, it marked a wider turning point in the history of European football, as it was the first truly pan-European club competition (Vonnard 2019a). Although other large, supranational tournaments existed before the Champion Clubs’ Cup (Mittag 2007), most notably the Mitropa Cup (Quin 2016), created in the 1920s, the Champion Clubs’ Cup was different in three significant ways. Most importantly, perhaps, it involved many more countries than previous competitions. At the height of its popularity, in the mid-1930s, the Mitropa Cup, involved clubs from just half a dozen countries,79 which played a total of 32 matches. In contrast, the first edition of the Champion Clubs’ Cup was contested by 16 clubs from 16 countries and the competition expanded rapidly: 22 clubs (all national champions) took part in the 1956–1957 edition and almost 30 national associations had teams registered for the competition at the end of the decade. This meant organising a large number of matches (55 during the 1958–1959 season), but it also fostered new exchanges between Europe’s football associations.

The second major difference concerned the competition timetable. Champion Clubs’ Cup matches were held throughout the football year, whereas Mitropa Cup games were concentrated into a four-to-five month period. Holding matches during the same period as the domestic championships was a novelty introduced by the Champion Clubs’ Cup. In fact, the new competition helped boost the importance of the domestic championships because becoming national champion meant qualifying for the ‘European Cup’, which was rapidly gaining in popularity and receiving wide coverage in both the sports and generalist press. Many sports newspapers began creating special European Cup sections containing analyses of matches, sometimes several weeks before they were played. To this end, journalists would often use performances in recent domestic league matches to assess the current form of an opposing club.80

Finally, the Champion Clubs’ Cup was open only to a country’s national champion, so the same teams rarely featured in consecutive editions of the competition. For example, only seven of the twenty-six teams that took part in the 1958–1959 competition had competed in a previous edition of the tournament. This ‘turnover’ of clubs allowed new connections to be built across all the different sectors of Europe’s football community, partly because of the number of people who accompanied teams to away matches. In fact, teams travelling to European matches generally had a large entourage of technical staff, club executives, national association members and journalists from the local and national press. This is why when the plane carrying the Manchester United team home from a match in Belgrade crashed near Munich in 1958 (Gaylor 2008), the victims included three members of the club’s staff and eight journalists (from the local and national press), as well as eight players. Ties with other countries were also increased by the tendency for clubs to use their trips abroad to schedule other matches. For example, when the Hungarian team Voros Lobogos travelled to France in December 1955 for a match against Stade de Reims, the club’s executives also scheduled three friendly games, against Grenoble and Nice, a week after the European Champions Clubs’ Cup game, and against Lyon in January 1956, although this final match meant doing another trip to France.81

Hence, the Champion Clubs’ Cup was a true break with pre-existing supranational tournaments and marked the beginning of a new phase in the history of European competitions. By making success in a club’s national championship the passport to a prestigious European competition, it also gave a boost to domestic football. As such, a European-level change had a significant impact on the development of football at the national level.

The success of the Champion Clubs’ Cup encouraged UEFA to see it as the first step in establishing other European competitions. Thus, on 18 March 1956, its executive committee ‘took note of a proposal by Dr Frey to create a similar event to the European Champion’s Cup, to be played among the winners of national cups’.82 Although no decision was taken on this matter, the proposal was discussed. The French journalist Gabriel Hanot was highly enthusiastic about the idea and used his coverage of UEFA’s annual congress in Lisbon, in June 1956, to support it: ‘L’Équipe will encourage [UEFA’s leaders], as it did for the [European champions clubs’ cup]’.83 L’Équipe’s influence should not be underestimated because the paper had already contributed greatly to the launch of the Champion Clubs’ Cup. In fact, L’Équipe was keen to both foster sporting exchanges across Europe and develop its own network of journalists, which is why its journalists had actively contributed to creating a European club competition in basketball in October of that year.84

Nevertheless, the idea of a national cup winner’s cup lay dormant until November 1957, when Spanish, Augustin Pujol, put a detailed proposal to his colleagues on UEFA’s executive committee. Pujol believed ‘this competition would interest the winners of the English, Spanish, French and Portuguese cups this year’.85 The executive committee finally gave its blessing to a revised proposal submitted by Pujol just before the start of the 1958 annual congress and decided ‘to form a committee, composed of Crahay, Graham, Frey and Pujol, to draw up the regulations, which would be submitted for approval to the next Congress, with the aim of implementing it for the 1959-1960 season’.86

Associations refusing to participate: Albania, Belgium, Denmark, England, Iceland, Netherlands, Soviet Union, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and West Germany;

Associations not yet wishing to answer: France, Italy, Luxembourg and Northern Ireland;

Associations agreeing to participate: Austria, East Germany, Ireland, Romania, Scotland and Turkey.

Twenty-one of UEFA’s thirty-one members replied to the consultation, which shows that most of Europe’s national associations took UEFA’s communications seriously. However, there was less support for the competition than the executive committee had expected, because 11 associations were unwilling to enter teams in the competition. And because it had been agreed that the competition would go ahead only if 10 associations or more were in favour, the executive committee did not take the idea forward.

The cup winners’ cup project is interesting because it shows both the executive committee’s desire to expand UEFA’s activities and some associations’ reluctance to move forward too quickly, despite the success of the Champion Clubs’ Cup in increasing exchanges in European football. This contrast was made even clearer by the difficult birth of the European Cup of Nations.

5.4 The Difficult Road Towards a European Cup of Nations

In a paper published in 2012, Fabien Archambault (2012) highlighted the difficulties involved in developing the ‘Europe du football’ during the 1950s. The information presented in the previous paragraphs suggests a more nuanced picture. However, there was one issue for which Archambault’s conclusion was justified: the launch of a European cup for nations.

Following the 1955 congress’ refusal to support a European competition for national teams, the executive committee set up a special commission to examine the issue in greater detail.88 Despite the commission’s advances, UEFA’s 1956 congress, in Lisbon, rejected the idea of creating such a competition89 mainly due to ‘differences of opinion on where football’s geographical boundaries lie, the turbulence of European geopolitics and the rivalries dividing Europe’s football leaders’ (freely translated from the French, Dietschy 2017, p. 26). However, the congress asked the special commission to continue its work and even strengthened it by expanding it from three members to five.

It was hoped that the enlarged commission would encompass the opinions of all the different forces within UEFA, which could then work together to find a compromise that would enable the competition to go ahead. One of the new members was Poland’s Lyzek Rylski, who joined Hungary’s Gustav Sebes as a second representative of the Soviet bloc. The presence of two Eastern Europeans beside three Western Europeans reflects the rapprochement between East and West that had begun following Stalin’s death. This process was given a boost in February 1956, when the Soviet Communist Party’s first secretary published the ‘Khrushchev Report’, in which he recognised the crimes committed during Stalin’s reign. This acknowledgement helped open the way for significant discussions between the leaders of the Eastern and Western blocs, ensuring that 1956 would be an ‘important date in European history’ (Rémond 2010, p. 351). The other new member of the commission was Spain’s Augustin, who had shown his support for UEFA’s expansion at the 1956 congress by backing both the idea of employing a full-time secretary general90 and the proposal to create a cup winners’ cup. The remaining two members of the commission were Austria’s Alfred Frey, who was also in favour of creating a cup winners’ cup, and Greece’s Constantin Constantaras.

The congress ensured the different forces within UEFA were represented on the commission in order to make sure the discussions progressed as smoothly as possible. They also chose representatives from national associations that believed UEFA should expand. In this respect, it is interesting to note that they were from countries which were generally absent from the European organisations that had emerged since the early 1950s. For example, the Franco regime became increasingly active in international sport, especially basketball and football, in the second half of the 1950s (Simón 2015a). Was this desire to become involved in sport a way for the authoritarian regimes of countries such as Spain and the Soviet Union to avoid being excluded from European cooperation projects?91

In addition to these internal UEFA decisions, influential voices in European football were advocating the creation of a tournament for European national teams and putting pressure on UEFA’s elite to make a final decision. Once again, Gabriel Hanot and Jacques Ferran were two of the competition’s greatest proponents and readily used the pages of L’Équipe to push UEFA on the issue. Reporting from the 1956 Lisbon congress, Hanot wrote that the delegates had decided to create a European Cup of Nations92 when they had, in fact, made no such decision. A few months after the congress, Jacques Ferran, who had written a long series of articles aimed at trying to move the matter forward,93 declared that the absence of a European competition involving all nations was a threat to European football’s prestige. He added: ‘the simplest, most obvious ideas encounter a thousand unexpected obstacles when they are confronted with the men responsible for putting them into practice. Since 1954, UEFA has been wavering, dithering and beating around the bush’.94 Ferran was not, of course, an entirely disinterested observer, as a new competition would mean more news and therefore more sales for the newspaper. However, Ferran was also showing support for the UEFA secretary general, Pierre Delaunay, who had taken over his father’s torch within UEFA but was struggling to bring the tournament into being.

The expanded study commission’s discussions resulted in a new version of the tournament proposal, which was sent to the national associations on 25 April 1957. In the covering letter, Pierre Delaunay explained that the members of the commission had tried to address potential criticisms, in particular by ‘reducing to a minimum the number of matches likely to be played by the countries involved, in order not to prejudice the establishment of their own international calendar’.95 The new proposal also provided more details on how revenues from the competition would be shared.

The commission’s proposal addressed the main concerns that had been raised over the past two years by limiting the time frame for the tournament, explaining how revenues would be distributed between the various bodies involved (UEFA, FIFA, national associations), and ensuring the tournament’s independence from the World Cup. Furthermore, a few hours before the 1957 congress opened, UEFA’s executive committee responded to a last-minute remark from the European members of FIFA’s executive committee by adding an amendment to Article 1 of the proposal stating that the competition will not take place until FIFA’s executive committee has given its approval.96 Despite the tournament supporter’s measured proposals and willingness to compromise, there was still a lot of resistance to the proposal, especially from members of FIFA’s executive committee. Barassi (and Rous), for example, expressed deep concerns that UEFA was trying to move too quickly and that the Cup of Nations would be a competition too many in an already crowded calendar. They even claimed that it could jeopardise friendly matches, which were very important sources of revenue for the national associations.97

Despite these reservations, the 1957 congress approved the proposal to set up a European Cup of Nations by 15 votes to 7, with 4 abstentions.98 Most of the associations agreed on the need for further work to produce a detailed and comprehensive proposal for discussion and final approval at the next congress. Consequently, the competition’s supporters spent the next year developing the project and convincing as many associations as possible to participate in the event. The 1958 congress would be the moment of truth: if a majority of the associations approved the proposals, the competition would go ahead; if not, the idea would be abandoned.

The debate was heated, but, thanks to the study commission’s efforts, 17 associations agreed to take part in the competition and the tournament could be launched. But this did not stop the tournament’s fiercest opponents, led by Barassi, Rous and Thommen, trying to postpone it once again, contending that further deliberation was needed. They even went as far as to suggest that UEFA was appropriating the national associations’ right to choose their opponents for international matches. Nevertheless, these attempts to obstruct the competition failed, and the congress gave it its approval. Even the Soviet bloc had come to fully embrace the competition in an apparent instance of the Soviet Union applying its new political doctrine of ‘peaceful coexistence’ to football. Indeed, the country’s policy was no longer to bring down capitalism but to prove the superiority of communism in all areas, including sport. Hence, the USSR’s leaders were now keen to see the country and its satellites compete in major sports competitions and contribute to the work of international sports organisations (Dufraisse 2020). The European Cup of Nations was an opportunity to implement this policy because it would allow Soviet bloc countries to play those of the capitalist bloc. And, after winning gold at the 1956 Olympic Games and reaching the quarter-finals of the 1958 World Cup, the Soviet regime was confident it had a team capable of demonstrating the superiority of the communist system (Edelman 1993, pp. 128–133).

The draw for the first edition of the Cup of Nations was held just a few hours after the congress ended, partly as a way of ensuring there was no backtracking on the decision to launch the tournament and thereby avoid possible conflicts within UEFA, but also because the competition was due to start the following month. The 17 countries that went into the draw were (in alphabetical order): Austria, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, East Germany, France, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Soviet Union, Spain, Turkey and Yugoslavia.

It is noteworthy that Spain, which had strongly supported the project, and France and Denmark, the home countries of UEFA’s secretary general and president, took part in the competition, whereas the British, West German and Italian associations, which had fiercely opposed the competition, were absent, as were several small but influential European footballing nations, such as Belgium, Sweden and Switzerland. Consequently, the tournament would not have been able to go ahead without the participation of all eight Soviet bloc countries (including Yugoslavia).

The new competition continued and expanded the exchanges within European football that had begun during the interwar period, as the first rounds of the inaugural European Cup of Nations included matches between countries that had never played each other before, such as Spain versus Poland, and whose governments were at the opposite ends of the political spectrum—fascist Spain and communist Poland. Similarly, East Germany played Portugal for the first time, and the matches between Czechoslovakia and Ireland and between Austria and Norway were only the second time these countries had met in football history. However, the first edition of the tournament saw some problems. On the hand, all the political barriers were not open so easily as illustrated the refusal of Spain to play against Soviet Union in the quarter of final (see Sect. 6.1).

On the other hand, attendances at the semi-finals and final, which were played in France in early July, were lower than hoped for, probably because the timing was far from ideal. This period, which was apparently chosen at the insistence of the Soviet bloc countries, not only clashed with another extremely popular competition, the Tour de France, it meant the matches took place at the end of the increasingly long domestic season, which ended in the middle of June and which was usually followed by friendly club matches. As a result, it was difficult for the teams to prepare properly and some of them were unable to field their best players.99 Both these factors undoubtedly dented the competition’s popularity with the public. Although the two semi-finals attracted 30,000 and 28,000 spectators, only 18,000 people braved the rain to watch the final between the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia at the Parc des Princes in Paris.100

Nevertheless, by the early 1960s, the idea of European competitions had been accepted by most of the European football community, including the national association leaders who had initially opposed them. The undeniable success of the Champion Clubs’ Cup paved the way for the creation of the European Cup Winners’ Cup in 1961, while the vast majority of UEFA’s member associations took part in the second edition of the European Cup of Nations. Even the Inter-Cities Fairs Cup, which remained outside UEFA’s control, grew substantially, leading to discussions within UEFA as to whether it should gather the competition into its fold (see Sect. 8.2).

Creating and organising these competitions strengthened UEFA’s position and fostered exchanges within the European football community. They also increased the executive committee’s desire to develop numerous aspects of European football, a goal that would not have appeared very realistic at the start given the political divisions between UEFA’s member countries.