The decision to decentralise FIFA, taken by the extraordinary congress in Paris in November 1953, triggered the creation of continental confederations in Africa and Asia, just as it had in Europe. This process led not only to the ‘continentalisation’ of FIFA during the second half of the 1950s, but also to major changes in the way its executive committee managed the organisation.

One of the greatest impacts resulted from the continental confederations’ demands that FIFA support their development, which gradually called into question FIFA’s dominant position in world football. In this process, UEFA played a major role and at the end of the 1950s appeared as a leading continental confederation.

7.1 The Continentalisation of FIFA

Wishing to take stock of the reforms agreed by the extraordinary congress in November 1953 (see Sect. 4.2), FIFA’s leaders reviewed the situation just before the 1954 congress. They realised that the actions taken by Asia’s and Europe’s associations meant that these two continents would soon have their own confederations to stand alongside the existing Central American, North American and South American confederations.

Europe, they felt, had already formed its own grouping, even if such a body had not yet been officially created. For FIFA’s executive committee, ‘the minutes of the body’s assembly held on 12 April in Paris’,1 which noted the drafting of statutes for a European body and the date of a meeting to discuss them—15 June 1954, two days after FIFA’s congress—were enough to justify its supposition. It was, however, less certain about the situation in Asia and Africa. FIFA’s secretariat had received information about a meeting in Manila in May 1954, but it involved only 12 of the 24 Asian associations affiliated to FIFA, and no action appeared to have been taken by Africa’s associations.

Discussions on the executive committee’s new composition spilled over into the debates at FIFA’s congress, on 21 June 1954. Jules Rimet used his opening address, his last as FIFA president, to once again warn his colleagues of the risks that breaking-up FIFA’s unity posed for its further development. His speech was followed by a debate on how the decisions taken at the 1953 extraordinary congress should be implemented, during which Rodolphe Seeldrayers conceded that the executive committee’s interpretation of the Thommen compromise differed slightly from the exact wording agreed in Paris. Under this interpretation, national associations would have to join together in continental organisations in order to be eligible for the executive committee seats allocated to their region. Consequently, the 1954 congress would have to decide whether Africa and Asia had continental organisations. If not, the congress would be free to fill these seats by electing members from any region.

The discussion stopped here and did not resume until it was time for the elections. In fact, the only position up for election was president. Here, the congress opted for continuity by electing Seeldrayers, who had served on the executive committee since the 1920s, to take over from Jules Rimet. The congress then noted the nominees for the positions of vice-president put forward by the British associations (1 vice-president), the Soviet Union (1 vice-president), the South American confederation (1 vice-president) and the European associations (2 vice-presidents). When it came to the committee’s ordinary members, the North, Central and South American confederations each nominated one member and the grouping of European associations, whose constitutive congress had chosen four representatives a few days before FIFA’s congress, nominated four members. This moment was when the debate on the seats allocated to the African and Asian associations resumed, and with great vigour. Sudan’s delegate, Dr. Halim, acknowledged the absence of a continental organisation for Africa but felt that, ‘the time has come for African and Asian associations to appoint their own representatives’.2 His Egyptian colleague, Abdel Aziz Abdalla Salem, and Yugoslavia’s Mihailo Andrejevic conveyed a similar message. Hence there was a clear divide between Western Europe and South America, which insisted that the African and Asian associations had to form continental organisations before being allocated seats on the executive committee, and Africa, Asia and Eastern Europe, which were demanding greater recognition for Africa and Asia within FIFA.

In the end, the only way to break the deadlock was to hold a vote. The result was a defeat for the executive committee, whose recommendations were rejected by 23 votes to 17, and a victory for the African associations, who were now able to choose their representative on the committee. Similarly, the Asian grouping, created in Manila in May 1954, also gained official recognition, but when the Asian associations named their executive committee representative, China protested because it had not been invited to the meeting in Manila and therefore maintained that the Asian grouping did not represent the Chinese association. Rimet ended the discussion by evoking FIFA’s long-standing policy of not interfering in its members’ internal affairs and declaring this to be a matter for the Asian confederation, not for FIFA.

Composition of FIFA’s executive committee under the 1954 statutes

Function | Voting body |

|---|---|

President | Congress |

Vice-president (1) | USSR |

Vice-president (1) | 4 British associations |

Vice-president (2) | European associations |

Vice-president (1) | South American confederation |

Member (4) | European associations |

Member (1) | South American confederation |

Member (1) | Central American confederation |

Member (1) | North American confederation |

Member (1) | African associations |

Member (1) | Asian associations |

The following months saw Africa’s, Asia’s and Europe’s national associations begin the process of creating continental bodies and drawing up provisional statutes, which they then submitted to FIFA.3 By 1956, the new continental bodies were up and running and able to hold meetings of their member associations prior to FIFA congresses in order to discuss organisational matters and their positions on the issues on the congress agenda. In terms of their structure, these bodies adopted similar models to FIFA and the South American confederation, whose continental competition they were also keen to emulate. Progress in this area was extremely rapid and Africa was ready to hold its first continental tournament, hosted by Sudan, in February 1957.4

Many of the new countries created by the decolonisation process reorganised the way they administered football and replaced the colonial-era elite with new, more politicised leaders who did not share the (Western) European elite’s ideal that football should be apolitical (e.g. Ghana, Nicolas and Vonnard 2019). Furthermore, the newly decolonised countries wanted greater international recognition so, according to Paul Dietschy, “at the same time that these new nations started knocking on the door of the UN, they began applying for FIFA membership” (Dietschy 2020b, p. 33). As a result, the new leaders of these national associations did not hesitate to put pressure on FIFA to address political issues. South Africa offers a case in point. At this time, South Africa had two football associations because the country’s white football association would not accept black players (Bolsmann 2010, pp. 36–37). In the late 1950s, the Asian and African confederations wanted FIFA to take action by excluding the South African FA until it accepted all players, no matter the colour of their skin. In contrast, FIFA’s predominantly European executive committee refused to take a stand on the issue, citing the old mantra of not mixing politics with sport (Darby 2008).

Another of the continental confederations’ aims was to boost football in their region, for which they requested logistical and financial support from FIFA. For example, in October 1957, Asia’s executive committee member, Jack Skinner, expressed his wish to run a refereeing course during the 3rd Asian Games, due to be held in Tokyo from 20 May to 1 June 1958. His colleagues agreed to help by covering the travel and accommodation expenses involved in sending Stanley Rous to Tokyo as the course instructor.5

The new confederations’ demand to receive a percentage of the gross revenues FIFA receives from international football matches was a much more substantial request. Doing so would give these confederations a similar right to that accorded to the South American confederation under Article 31, paragraph 5, of FIFA’s statutes, according to which associations affiliated to the South American confederation ‘shall pay only 1% [of a match’s gross revenue] to FIFA for matches played between them, while the other 1% shall be paid to [their continental entity]’.6 UEFA’s executive committee set the ball rolling on this issue in 1955 when it expressed its intention to ‘ask the Fédération Internationale de Football Association to include on its next congress agenda a proposal to ensure that only 1% of the gross revenue from international matches played between European countries is paid to FIFA; [and that] 1% is paid to the European Union’.7 However, FIFA’s European executive committee members, especially Barassi and Thommen, were unhappy with the request from their counterparts at UEFA. On 3 December 1955, FIFA’s emergency committee—composed of Drewry, Lotsy and Thommen—reported that ‘a reduction in this percentage would have a disastrous effect on FIFA’s financial situation’.8 In fact, in 1954 FIFA obtained almost 71% (158,878.28 Swiss francs) of its income (excluding World Cup income) from international matches.9 Because a large percentage of these revenues undoubtedly derived from matches involving European teams (detailed figures are not available), redistributing a proportion to UEFA would significantly impact FIFA’s finances. Aware of the need to provide financial support to UEFA (and the continental confederations in general), the members of the emergency committee, all of whom were European, began examining alternative solutions, such as abolishing the British associations’ exemption from paying a percentage of its revenue from its ‘Home Internationals’ tournament (accorded when they re-joined FIFA in 1946), but without success.

FIFA’s delaying tactics did not weaken UEFA’s resolve, especially given the similar demands now being made by the other continental confederations. For example, the Confederation of African Football’s (CAF) draft statutes, which it sent to FIFA at the beginning of 1956, included a plan to finance its operations by ‘splitting with FIFA the revenue from international matches played between members of the African Football Confederation’.10 UEFA’s conviction that FIFA had the means to support the continental confederations was bolstered by FIFA’s increasingly solid financial position, as demonstrated by its ability to acquire a new headquarters in the centre of Zurich. Hence, UEFA’s executive committee was extremely disappointed by the lack of support from FIFA’s European executive committee members, who were supposed to represent and defend UEFA’s interests within FIFA. This is why, at a meeting in March 1956, UEFA’s executive committee decided to present its proposals for discussion at the next FIFA congress.11

In the weeks that followed, several measures were taken to resolve the problem. José Crahay and Pierre Delaunay paid an unofficial visit to FIFA’s secretary general to discuss several items on the agenda of the forthcoming FIFA congress, particularly the UEFA’s request to receive a proportion of the revenues from international matches collected by FIFA.12 As he had done many times in the recent past (Vonnard 2019c), Ernst Thommen stepped in as mediator and drew up a possible compromise solution, which he presented to a FIFA executive committee meeting in Lisbon, a few days before the 1956 FIFA congress at which the matter was due to be discussed. Thommen’s proposal was to increase the percentage of revenues FIFA received to 2% and for FIFA to redistribute a quarter of this amount to the relevant continental confederation. To convince the confederations to accept the proposal, he urged the members of the executive committee to actively discuss the matter with each one. However, the executive committee was not unanimously in favour of Thommen’s idea, as its non-European members, especially the Asian confederation’s member, Jack Skinner, preferred UEFA’s proposal.13

At the same time, the South American confederation’s new president, Carlos Dittborn, met with UEFA’s executive committee during its preparatory meeting for the 1956 UEFA congress, which would take place a few days before the FIFA congress. Dittborn offered South America’s support on a number of issues, including UEFA’s proposal for sharing FIFA’s earnings from international matches. A few hours later, UEFA’s congress unanimously backed its executive committee’s proposal and charged the French FA with presenting the motion to the forthcoming FIFA congress.14 FIFA’s congress quickly approved the motion, thanks to the support of a ‘large majority’15 of the other continental confederations, and it was added to FIFA’s statutes. From now on, FIFA would redistribute half of the amount it received from each international match (2% of the match’s gross revenues) to the continental confederation concerned. Although this measure did not apply to matches played as part of the World Cup, it was a key step in the continental confederations’ gradual emancipation from FIFA, as it not only put them on a more secure financial footing, it also showed that, either individually or jointly, they could successfully bring issues before FIFA.

The confederations’ growing independence made FIFA more difficult to manage and complicated the relations between the members of its executive committee, as they were now likely to put their continent’s interests ahead of FIFA’s. Doing so would greatly weaken FIFA’s traditional collegial approach to management. On 22 July 1957, Karel Lotsy, who had been a member of the executive committee since the 1930s, exhorted his colleagues not to forget that they represented the executive committee and should always present its majority position during congresses.16 However, undoubtedly aware that committee members’ opinions diverged on numerous issues, a few months later a compromise was reached in which ‘the president may [authorise an officer] of the executive committee to speak on behalf of the minority’.17

As Sugden and Tomlinson (1997) have shown with respect to the race for the FIFA presidency, relations between continental confederation and FIFA, and especially between UEFA and FIFA, were not always harmonious. This continental confederations’ growing importance led to the idea that they should be made full members of FIFA and therefore have the right to submit amendments to FIFA’s statutes. The idea was first discussed by UEFA’s executive committee on the eve of the 1956 FIFA congress, but it did not put a concrete proposal to the assembly. UEFA’s rapid development contributed to the continentalisation of the FIFA and played a role in the recognition of the continental confederations within the international federation.

7.2 Achieving Autonomy from FIFA

The decisions UEFA’s elite took between 1955 and 1960 boosted European football and enabled UEFA to establish itself as its governing body. However, UEFA’s rapid rise created tensions with the European members of FIFA’s executive committee, who, despite having helped create UEFA and being in favour of it developing, believed it should remain subordinate to FIFA. A primary cause of these tensions was a series of decisions taken by UEFA’s executive committee in 1956 and 1957 that called into question FIFA’s superior status.

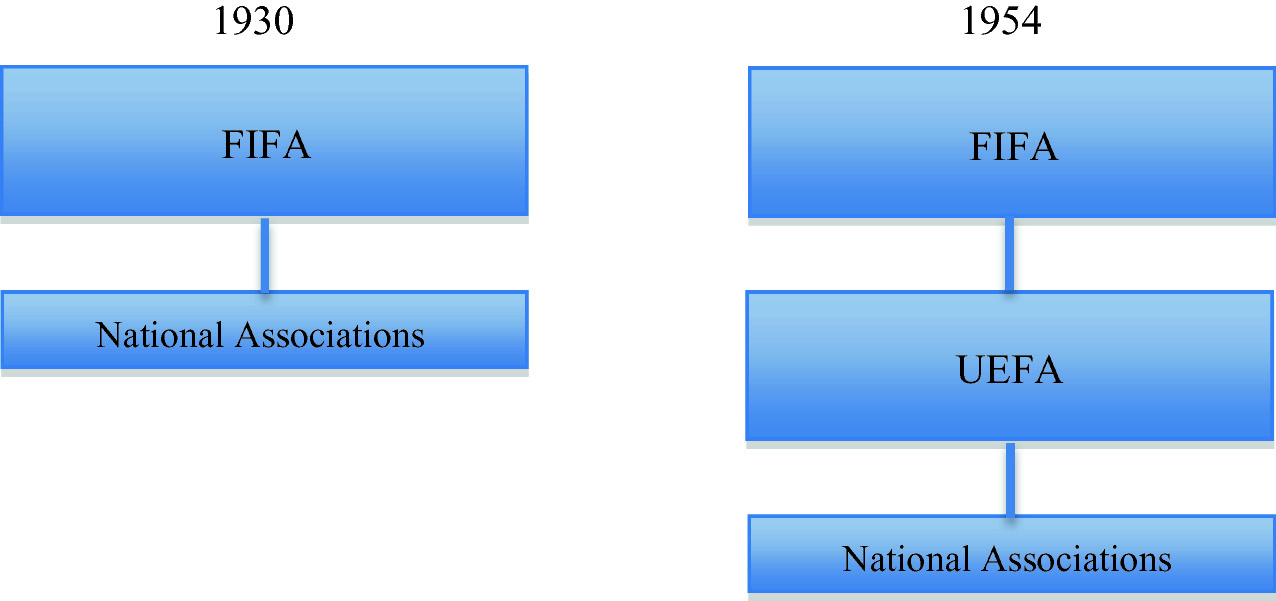

European football bodies in 1930 and 1954

Although there were many subjects on which FIFA and UEFA agreed, as noted above with respect to the creation of the European Chamipons Clubs’ Cup (see Sect. 5.3) and the issue of setting UEFA’s geographical boundaries (see Sect. 6.2), disagreements began to emerge in 1955, triggered by UEFA’s takeover of the International Youth Tournament. FIFA had run the tournament since 1949, but by the mid-1950s it was being suggested that it should be handed over to UEFA. One reason for this was the lack of a specific commission for youth tournaments within FIFA, which meant its secretariat had to organise the competition in conjunction with the host country’s organising committee (see Sect. 2.1). These dealings with national associations often exasperated FIFA’s secretary general, Gassmann, who expressed his frustration in September 1955: ‘Once again, we had to remind the associations on several occasions to send us their comments and suggestions. Twelve of the nineteen accepted our invitation. It is with regret that we note this lack of collaboration’.19 Given the tense political situation between Eastern and Western Europe, organising the tournament required a lot of work, which FIFA’s secretariat had neither the time nor the resources to do. For example, FIFA was criticised for East Germany being unable to take part in the 1955 tournament because the Italian government failed to provide its team with the necessary visas. This intrusion of politics into football raised a huge outcry and resulted in FIFA’s secretariat receiving nearly 80 telegrams and letters of protest from various members of Europe’s football community. Another important reason for entrusting the tournament to UEFA was South America’s desire to start a similar competition for its continent.20

These tournaments must, however, be played in accordance with the provision of the regulations set up by the executive committee which shall be in force in all continents. The executive committee shall supervise the tournaments and delegate one or several members to control the application of the provisions of the general regulations.21

On 5 January 1956, Kurt Gassmann contacted UEFA’s secretary general, Pierre Delaunay, to ask him if UEFA would be willing to take over the European version of the competition as of 1957. In his letter, Gassmann informed Delaunay that FIFA would devolve only the running of the tournament to UEFA and, consequently, ‘[UEFA’s] executive committee [will] only deal with the general regulations governing the tournament, which would be the basis for it. It must be the same for all youth tournaments, no matter where they take place’.22 Delaunay immediately agreed to include the issue on the agenda of the next UEFA executive committee meeting, scheduled for March.23

The transfer of responsibility for the tournament to UEFA was clearly acknowledged in Gassmann’s secretary general’s report for 1954–1955, which was published in March 1956. Gassmann wrote that ‘in the future - i.e., from 1957 onwards - the tournament in Europe must be organised by the Union of European Football Associations’,24 which would, nevertheless, have to comply with the regulations established by FIFA, whose executive committee would retain control over the tournament. UEFA’s executive committee formally accepted FIFA’s proposal on 18 March 1956.25

Although FIFA saw passing responsibility for organising the tournament to UEFA as a simple transfer, UEFA felt it was an ideal time to review the competition’s rules, especially the new rule under which there would be no designated winner. Ottorino Barassi had introduced this rule in his role as president of the organising committee for the 1955 edition in Italy, at least partly in response to Karel Lotsy’s earlier criticisms of the declining spirit of fraternity in the competition (Marston 2016, p. 144). Not designating a winner was intended to make the tournament, which also included a programme of cultural activities, more convivial. UEFA’s proposal to reinstate the idea of a tournament winner was not well received by FIFA’s executive committee, especially its European members, who had been responsible for the recent amendments to the tournament’s rules.

In order to ensure a smooth handover, delegates at the 1956 UEFA congress agreed to create a special committee for youth football. For this task, they chose men who had experience of youth football,26 including England’s Stanley Rous, who had launched the tournament in 1948 and who was a great proponent of youth football; Germany’s Karl Zimmermann, who had helped organise the 1953 tournament in Germany; France’s Louis Pelletier, who chaired the French FA’s youth commission; and Czechoslovakia’s Joseph Vogl, who was involved in youth football in his country. They were joined by José Crahay, representing UEFA’s executive committee, who was strongly in favour of UEFA developing competitions. In addition to their experience and desire to develop youth football, the committee’s members represented all the different forces and blocs within UEFA, except Scandinavia. Creating this committee enabled UEFA to take over the organisation of the tournament. FIFA’s and UEFA’s secretary generals corresponded frequently on this subject throughout the summer of 1956. On July 6, Gassmann reminded Delaunay of the spirit in which FIFA’s executive committee had entrusted the European youth tournament to UEFA.27 He also sent Delaunay documents he felt would be useful and said he would be available to meet if necessary. Gassmann’s actions were as much a way of demonstrating FIFA’s hierarchical superiority as a way of supporting UEFA’s secretary general. Delaunay responded by informing Gassmann that UEFA’s executive committee had made all necessary provisions.28

A few weeks later, Delaunay provided an update on the progress that had been made, noting that a meeting of the UEFA committee set up to run the tournament would take place on 28–29 September and be followed by a discussion about the competition by UEFA’s emergency committee. These meetings, he added, would examine possible changes to the tournament’s rules because UEFA’s leaders did not share FIFA’s opinion on the conditions for organising the youth tournament. Delaunay’s remarks were a turning point in the relations between UEFA and FIFA and elicited an immediate reaction from Gassmann, who wrote to Delaunay to remind him that ‘the tournament must be organised according to the guidelines established by the FIFA executive committee’.29 For Gassmann, UEFA would be going beyond its remit if it tried to change the tournament’s rules. Feeling that FIFA was losing its influence over UEFA, Gassmann wrote to FIFA’s new president, Arthur Drewry, who had been appointed by the 1956 congress following the death of his predecessor, Rodolphe Seeldrayers. Drewry hoped the presence on UEFA’s youth committee of Stanley Rous, who had similar views to the European members of FIFA’s executive committee, would prevent any reforms being approved. However, Rous was in the minority on the committee and was therefore unable to block the proposed changes.30

UEFA obviously intended to run the tournament independently of FIFA’s decisions and recommendations, and FIFA’s executive committee realised it would be impossible to convince UEFA’s leaders to act differently. FIFA could, however, express its disapproval of the way UEFA was managing the event, which it did by refusing its request to use the trophy from previous tournaments on the pretext that it was ‘not intended for the junior tournament of a single continent’.31

In April 1957, a few weeks after the first UEFA-organised edition of the tournament, José Crahay presented the changes to the tournament’s regulations as an attempt to ‘increase the [tournament’s] success in both sporting and entertaining terms’.32 The main change was to reinforce the tournament’s competitive aspect by reinstating the principle of an overall winner. In fact, even if the tournament committee approved of FIFA’s attempt to reduce the focus on competition, it was obvious that the teams involved were still trying to win the tournament. The altercation over the youth tournament came to an end in June 1957, when FIFA’s executive committee acknowledged ‘that the organisation of this tournament had passed entirely into the hands of the Union of European Football Associations’.33 The youth tournament’s transfer to UEFA highlighted not only the European confederation’s growing independence from FIFA but also the differences in the way the European members of FIFA’s executive committee, notably Barassi, Lotsy and even Thommen, viewed football administration compared with their UEFA counterparts. As Kevin Tallec Marston (2016, p. 152) rightly noted, UEFA’s approach was not a complete break from FIFA’s attitude; rather, it was a case of FIFA focusing on football as a means to build fraternity, whereas UEFA’s priority was the competitive side of football.

The reasons why the two organisations had different outlooks may be found in their social and career backgrounds. Both organisations’ leaders had had long careers in national football administration before rising to the top of FIFA or UEFA. Hence, as secretary general or president of their national association, they visited many of Europe’s capitals to attend FIFA congresses and accompanied their national teams to matches around the world. These trips enabled them to build a large store of relational capital and to develop a cosmopolitan world view. Although little information is available about many of these leaders’ early careers (Vonnard 2017), most of them appear to have come from middle-class backgrounds which suggests that most of them had enjoyed a university (or similar) education. As a result, the leaders of both organisations would have had similar cultural capital and most of them spoke two or three European languages. Some had also lived in a foreign country. This was the case for Delaunay, who lived in London when he was in his twenties, and Sebes, who spent several years in France during the 1930s.

Despite these similarities, there were other areas in which the profiles and backgrounds of FIFA’s and UEFA’s leaders differed. Most importantly, the men who composed UEFA’s executive committee embodied a new generation of European football executives, most of whom had not been top-class players or referees. The two remaining members of the old guard, Gustav Sebes and Henry Delaunay, were rare exceptions to this rule, as Sebes had played briefly in France (Hadas 1999) and had coached Hungary’s 1954 World Cup team, and Delaunay had been a national-level referee (Wahl 1989). In contrast, although the other members of the executive committee had played football in their youth, they never played at a high level and therefore probably had a different relationship to the game to their predecessors. Another difference was that three of the six members of UEFA’s executive committee (Crahay, Delaunay and Graham, plus Stanley Rous, who can be seen as Graham’s replacement, from 1958) had served as secretary general of their national association. This would have precluded them from rising to the top of FIFA, as football executives who had been paid for their services were not allowed to sit on its executive committee.34 Thus, the election of Crahay, Delaunay and Graham to UEFA’s executive committee shows that from the very beginning, UEFA’s leaders wanted to distance themselves from FIFA’s customs and traditions, and follow their own path. The presence of national association secretaries on UEFA’s executive committee is significant, because their managerial experience would have given them a technocratic view of football administration, rather than the idealistic view typical of most national association presidents. Consequently, they are more likely to have seen developing football, especially professional football, as more important than more general ideals, such as football’s social utility, which are more relevant to amateur football. Their presence was also a sign of the gradual professionalisation of European football that was occurring due to the need to effectively administer the growing number of matches being played and the ever-expanding range of tasks executives were being asked to carry out.

In 1956, FIFA also gave into the above-mentioned request for revenue redistribution. This was yet another step in the gradual moving apart of the two organisation’s executive committees. The tension increased again two years later, when UEFA asked FIFA to redistribute revenues from World Cup matches. The percentage FIFA finally agreed to redistribute not only made a significant contribution to UEFA’s finances and its ability to expand its activities, it confirmed its ability to act independently from FIFA. UEFA’s executive committee demonstrated this independence in October 1958, when it removed the acronym ‘FIFA’ from the header on UEFA correspondence and the organisation’s statutes.35

However, having a strained relationship with FIFA would not be in Europe’s long-term interest, as FIFA’s continuing international expansion was certain to erode Europe’s dominance over the world governing body. With this in mind, the European members of FIFA’s executive committee met with UEFA’s executive committee at the beginning of 1959 in order to try and get the relationship between the two bodies back onto a more favourable footing. Stanley Rous’s election to UEFA’s executive committee may have facilitated the dialogue, as Rous was on good terms with Barassi and Thommen. Whether or not this was the case, on 5 March 1959 UEFA’s president, Ebbe Schwartz, expressed his satisfaction that relations between the two organisations were improving.36 Thommen took the process further in December 1959 by setting up a FIFA-UEFA consultation committee, which he hoped would improve ties between the organisations’ executive committees. The consultation committee held its first meeting in Paris, after which Thommen wrote to UEFA’s executive committee to express both his satisfaction with the meeting and his conviction that the procedure was an important step in ensuring a good understanding between FIFA and UEFA.37 The aborted European Cup of Nations quarter-final between the Soviet Union and Spain (see Sect. 6.1) provided an opportunity for FIFA and UEFA to demonstrate their new-found entente and their acceptance of each other’s areas of responsibility. When the Soviet Union filed a complaint with FIFA, in May 1960, FIFA’s emergency committee refused to consider the matter because it concerned a competition organised by UEFA and ‘therefore the UEFA executive committee is competent to decide on the dispute’.38

During its first few years, UEFA gradually secured its independence from FIFA, which enabled it to establish a monopoly over the administration of European football. This policy influenced the other continental confederation and also the South American body who was until the mid-1950s a model for the new entities that were emerging in Africa, Asia and Europe.

7.3 Inspiring the South Americans in Return

In Europe, South America’s approach served as inspiration for the discussions that led to the creation of the UEFA (see Sect. 2.3 and Chapter 4) and as noted in the previous section heavily influenced its request to receive a percentage of the revenues FIFA collected from international matches. South America’s continental competitions, such as the Copa America, which date back to 1915, the South American youth tournament, first held in 1954, and the Pan-American confederation’s Pan-American Championship, launched in 1952,39 were also seen as examples to follow. However, UEFA’s rapid development influenced the other confederations, even South America.

In a paper on ‘contrastive history’, Michael Werner and Bénédicte Zimmermann noted: ‘When we study contacts between societies, we frequently observe that objects and practices are not only interrelated, they also evolve as a result of this relationship’ (freely translated from the French, 2003, p. 12). This approach is closely linked to the concept of ‘cultural transfer’, which focuses on the arrival and development of a practice in a territory and illuminates its progressive change under the influence of the cultural context (Fontaine 2019).40 Applying this concept to football’s new continental bodies suggests that interactions between their leaders are likely to have influenced the way they structured their confederations. Thus, given UEFA’s rapid development and the well-organised nature of its national associations, its actions would be expected to influence those of non-European leaders, particularly those of the South American confederation.

The first example of this influence concerned UEFA’s response to the need to find new sources of revenue to cover its ever-increasing expenses. As UEFA’s activities expanded by, for example, taking over the organisation of the International Youth Tournament from FIFA—as explained in the previous section—its executive committee needed to cut costs and find additional income.41 Having already obtained a percentage of the revenues FIFA received from non-World Cup international matches played in Europe (see Sect. 7.2), a request that was inspired by a similar agreement between FIFA and the South American confederation, it took the unprecedented step of asking FIFA to extend the system to World Cup matches. That UEFA was prepared to make such a groundbreaking request and that FIFA’s executive committee considered it, in 1957 and 1958, shows the European confederation’s growing self-confidence and increasing importance within the world governing body. In a tentative first step, UEFA wrote to FIFA’s executive committee on 28 February 1957 to ask whether FIFA would contemplate sharing the percentage of gross revenues it received from World Cup matches, so 4% went to FIFA and 1% went to UEFA,42 and whether such an agreement had been reached with any of the other confederations. FIFA’s secretary general, Kurt Gassmann, conveyed the executive committee’s unequivocal response: ‘the 5% of gross revenues from the 1958 World Cup qualifiers will go entirely to FIFA’.43 Gassmann also noted that FIFA had no agreement to redistribute a percentage of these revenues with the other continental confederations and was not contemplating any such agreements. Undeterred by this response, UEFA’s executive committee decided to go on the offensive and put the issue to FIFA’s next congress.44 Once again, UEFA was showing its willingness to challenge the authority of FIFA’s executive committee.

UEFA felt its request was reasonable given the apparent robustness of FIFA’s finances, a judgment that was based, at least partly, on FIFA’s ability to record a surplus for the previous year. Although the 21,171.86 Swiss francs profit FIFA posted for 1956 may seem small, it was rare for FIFA to make a profit, especially in a non-World Cup year, so any profit was seen as a sign of financial good health. This was confirmed the following year, when FIFA’s surplus increased to 74,671 Swiss francs.45 In addition, FIFA had more than CHF2 million in assets.46 Nevertheless, FIFA was unwilling to bow to UEFA’s request. In his 1956–1957 activity report, UEFA’s secretary general noted that FIFA’s executive committee disagreed with the national associations that felt FIFA should the 5% of gross revenues it received from World Cup matches by redistributing 1% of these gross revenues to the appropriate continental confederation.47 Delaunay’s report refers to national associations, rather than continental bodies, because the confederations were not yet considered members of FIFA. Undoubtedly as a way of avoiding further discord, FIFA agreed to discuss the matter at its next congress.

As negotiations continued through the first few months of 1958, Barassi and Thommen attempted to mediate. Their discussions with a delegation from UEFA’s finance committee finally resulted in a compromise under which FIFA would retain all the revenues it earned from the 1958 World Cup but accede to UEFA’s request for the 1962 edition.

Why did FIFA, and especially Barassi and Thommen, change their minds? One reason may be the support UEFA had received from other continental confederations, particularly the South American confederation, which had made a similar request via the Brazilian FA. This demand was never mentioned by FIFA’s executive committee, so it was probably filed after UEFA’s request. Another possible hypothesis is that the continental confederations were preparing an alliance so they could present a united front at the FIFA congress. Whatever the reason for FIFA’s decision, during UEFA’s 1958 annual congress, the chairman of UEFA’s finance committee, Peco Bauwens ‘welcome[d] the fact that an agreement with FIFA seems to have been reached on this point’.48 UEFA’s member associations were also happy with Barassi and Thommen’s proposed compromise, which they approved at the UEFA congress. A few days later, FIFA’s congress agreed ‘by a large majority’49 that the confederations would now obtain 1% of the gross revenues from World Cup matches, out of the 5% received by FIFA. In addition to strengthening UEFA’s and the other confederations’ finances, this decision enabled UEFA’s leading executives to position themselves as particularly active players in their confederation’s development and made UEFA’s actions a source of inspiration for the other continental bodies.

UEFA’s statutes,

the rules of the European Champion Clubs’ Cup,

the rules of Europe’s referees commission,

the rules of the International Youth Tournament.

This letter raises at least two interesting points. First, why did Ramos de Freitas contact FIFA for this information, rather than going directly to UEFA? Was it because he saw UEFA as subordinate to FIFA and therefore felt he should contact FIFA first? Second, why did the South American confederation need these documents? Was it considering reforming its own structure? None of the information provided by FIFA’s correspondence with the South American confederation provides precise answers to these questions.

On the other hand, it is clear that the South Americans asked for the rules of the Champion Clubs’ Cup because they were looking to create a similar competition for South American clubs. As L’Équipe reported in the summer of 1959,51 the South American confederation was discussing the possibility of transposing the increasingly successful European Champion Clubs’ Cup to South America. The result was the Copa Libertadores, the first edition of which took place during the 1959–1960 season, with matches taking place mainly in the spring. Of course, the Copa Libertadores did not follow exactly the same format as the Champions Cup, but it appears to have been inspired by the European competition.

The other continental confederations followed suit during the 1960s by launching their own club competitions. Thus, by the end of the 1950s, UEFA had become an inspiration for all the world’s confederations and much more influential within FIFA.