Chapter 15

Roaring through the ’20s with Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover

IN THIS CHAPTER

Being unfit for the presidency: Harding

Being unfit for the presidency: Harding

Staying silent and accomplishing nothing: Coolidge

Staying silent and accomplishing nothing: Coolidge

Reacting too slowly to the Great Depression: Hoover

Reacting too slowly to the Great Depression: Hoover

This chapter covers the three Republican presidents of the golden 1920s. Times were good: The economy was booming until 1929, and the country wasn’t involved in any foreign conflicts. So the presidents didn’t do much.

Harding was too busy playing poker and cheating on his wife to run the country. Coolidge didn’t want to do anything but sleep. And Hoover reacted to the Great Depression a little too late. Today, all three presidents are considered failures. None of them even cracks the top-20 list of presidents.

Living the High Life: Warren G. Harding

Harding’s administration is famous for its corruption. Harding himself wasn’t crooked, but he appointed many friends who used their positions to enrich themselves, which reflected badly on Harding.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 15-1: Warren G. Harding, 29th president of the United States, and his dog Laddie.

Harding was one of the most immoral and hypocritical individuals to ever occupy the White House. He married for money and had many adulterous affairs (fathering a child with one mistress). The Republicans paid one of his long-time girlfriends to go to Europe so that she’d be out of the way during the presidential campaign. Even though he supported prohibition, he had his own distributor provide him and his poker buddies with liquor in the White House. By 1923, these actions came back to haunt him. However, his premature death at the age of 57 saved him from many embarrassments.

Harding’s early political career

The Ohio Republican Party recruited Harding to run for the Ohio state senate in 1898. He won his initial race and was reelected in 1900. In 1903, he became the lieutenant governor of Ohio, a post he held for two terms.

While working in the Ohio state government, Harding befriended Harry M. Daugherty, a major leader in the Ohio Republican Party. Daugherty became his trusted advisor and campaign manager.

When Harding lost the race for governor in 1910, he wanted to retire from politics. His wife and friends had other ideas. They talked him into staying active in politics. In 1914, he won a seat in the U.S. Senate.

Becoming president by default

By 1919, Harding’s political handler, Daugherty, believed that Harding was ready for the presidency. He sent Harding to speak all over the country.

At the Republican convention, Harding, a second-rate candidate, seemed a long shot. However, when the party couldn’t agree on a candidate, Harding started looking better. After a long night in one of the famous smoke-filled rooms, the Republican Party agreed on Harding. Calvin Coolidge, the governor of Massachusetts, became his vice-presidential candidate.

After winning the nomination, Harding stayed in Ohio and campaigned from his front porch. His handlers didn’t want him to mingle with the voters: They were afraid that he would offend and alienate them.

President Warren Gamaliel Harding (1921–1923)

Harding’s inaugural speech set the tone for what was to come. His address was the worst in U.S. history. A British reporter called it “the most illiterate statement ever made by the head of a civilized government.” Harding’s treasury secretary, after listening to many of Harding’s speeches, said, “His speeches left the impression of pompous phrases moving over the landscape in search of an idea. Sometimes these meandering words would actually capture a straggling thought and bear it triumphantly, a prisoner in the midst, until it died of servitude and overwork.”

Defrauding and scandalizing the nation

Harding’s first priority as president was to organize a weekly poker game that his whole cabinet was required to attend. Many political decisions took place while the president and his cabinet played cards.

Harding’s cabinet contained some of the best and worst people to ever serve the United States. Harding appointed his friends, referred to as the “Ohio Gang,” to high-level cabinet positions. The Ohio Gang started defrauding the government soon after they entered office. Following are some of the more famous scandals under Harding:

- Charles Forbes, the head of the Veteran’s Bureau, defrauded the government of $200 million. Harding allowed him to flee the country. When he returned, years later, Forbes went to jail. Forbes was the first U.S. cabinet member to be sentenced to jail.

- Harry M. Daugherty, the attorney general, sold alcohol during Prohibition. During Prohibition, it was illegal to make or distribute alcohol.

Albert B. Fall, the secretary of the interior, was involved in the Teapot Dome Scandal.

Teapot Dome was a federal facility where the U.S. Navy drilled for and stored oil. In 1922, Fall leased the facility to two oil companies that paid him $400,000. Fall went to jail for his actions in 1929.

Succeeding despite himself

Harding had his moments. His administration was successful in a few areas, where his accomplishments included

- Reducing income taxes

- Protecting U.S. industries from foreign competition with the Fordney McCumber Act — an act that increased tariffs

- Restricting immigration from Europe with the Immigration Act of 1921

- Allowing blacks in federal government positions

- Signing a separate peace treaty with Germany, officially ending the war in Europe

Calling the Washington Conference

In 1921, Harding called for a conference in Washington between the great powers. The Washington Conference resulted in the Five Power Treaty, which limited the number of ships and aircraft carriers that the five great powers in the world could have. (The five great powers at the time were the United States, Great Britain, France, Japan, and Italy.) The conference further established the Four Power Treaty, signed by the United States, Japan, Great Britain, and France. In it, the four countries pledged to recognize each other’s possessions in the Pacific. The conference proved to be the most notable achievement of the Harding administration.

In 1921, Harding called for a conference in Washington between the great powers. The Washington Conference resulted in the Five Power Treaty, which limited the number of ships and aircraft carriers that the five great powers in the world could have. (The five great powers at the time were the United States, Great Britain, France, Japan, and Italy.) The conference further established the Four Power Treaty, signed by the United States, Japan, Great Britain, and France. In it, the four countries pledged to recognize each other’s possessions in the Pacific. The conference proved to be the most notable achievement of the Harding administration.

Dying suddenly

By 1923, Harding had fallen into despair. All the scandals, involving some of his best friends, got to him. He decided to tour Alaska. He suddenly became ill on his trip home, so he stopped in San Francisco to rest. He died there on August 2, 1923, of a possible stroke.

Quietly Doing Nothing: John Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge’s nickname was “Silent Cal.” How appropriate! As president, Coolidge didn’t do much. The United States was at peace and doing well during his term. So Coolidge, shown in Figure 15-2, enjoyed the presidency — he slept a lot and was fairly anti-social. Instead of trying to prevent the approaching Great Depression, Coolidge sat back, believing that the government had no role in the economy.

Coolidge’s early career

Governing Massachusetts

As governor, Coolidge didn’t do much. But one event defined his term and turned him into a household name. In 1919, police officers in Boston formed a union and asked for more money. When the city refused, they went on strike. The mayor of the city suspended the union leaders and relied on state troopers to police the city. The mayor’s plan wasn’t sufficient. The crime rate went up. Criminals had a field day without the normal police force in place.

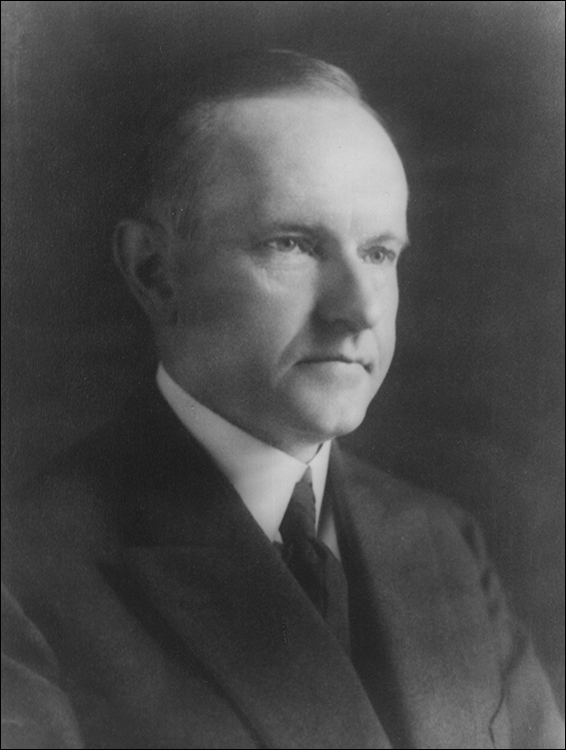

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 15-2: Calvin Coolidge, 30th president of the United States.

President Wilson applauded Coolidge’s actions, as did businesses nationwide. The resulting publicity helped him win reelection easily.

Becoming vice president

At the Republican convention in 1920, the Massachusetts delegation pushed Coolidge for the presidential nomination. They failed to get him nominated, although he did get the vice-presidential slot as a consolation prize. Coolidge accepted the bid happily. In 1920, he was elected vice president after resigning as governor. As vice president, Coolidge regularly joined Harding’s cabinet meetings — the first vice president to do so.

President Calvin Coolidge (1923–1929)

When Coolidge became president, he dealt with the scandals of Harding’s administration by firing the attorney general, Daugherty, and forcing the resignation of the secretary of the navy. He then proceeded to appoint well qualified, incorruptible people to office. His best appointment was Frank Kellogg as secretary of state.

In keeping with his values, Coolidge went straight to the people to explain the changes. Coolidge held many press conferences and had his State of the Union addresses reported live on radio.

In 1924, the economy was booming, and Coolidge was a shoo-in for reelection. The Republican Party renominated him. He easily defeated Democrat John W. Davis. Coolidge received almost twice as many popular votes as Davis, as well as 382 electoral votes.

Serving a second term

In 1925, the world was good. The U.S. economy was doing well, and there were no major international conflicts. Coolidge reduced the national debt and fought government intrusion in the economy. He repeatedly vetoed farm bills that would have allowed the government to purchase agricultural surpluses and keep prices for these goods high. His motto was simple: If it’s not broken, why fix it?

Showing his racism

On social policy issues, Coolidge held fairly racist views. He supported restrictions on immigration and publicly stated that Nordic races deteriorate when mixed with other races. In his view, the United States, being a Nordic country, had to restrict immigration from other non-Nordic countries.

Excelling in foreign policy

Coolidge’s greatest accomplishment came in the area of foreign policy. The subject bored him, but his secretary of state Frank Kellogg excelled in it. The passage of the Kellogg-Briand Act in 1928 was Coolidge’s crowning achievement in foreign policy. Secretary of State Kellogg received the Nobel Peace Prize for his accomplishments.

Choosing not to run

Coolidge was immensely popular. Had he decided to run for the presidency in 1928, he could have easily won. Instead, he issued a brief statement while on vacation in the summer of 1927, saying, “I do not choose to run for president in 1928.” There were no explanations attached to his message. Coolidge had just had enough. With the death of his son in 1924, Coolidge stopped enjoying the presidency. He believed that it was time to step down.

Coolidge retired in 1929 and wrote his autobiography. He sat on the boards of several corporations and became a trustee at his alma mater, Amherst College. Coolidge died of a heart attack in January 1933.

A Great Humanitarian, but a Bad President: Herbert Hoover

Herbert Hoover, shown in Figure 15-3, is the most maligned president in U.S. history. Many blame him for the Great Depression, which is quite unfair. He actually set the foundation for Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal policies (see Chapter 16 for more on these policies). Too bad his efforts weren’t better publicized. Hoover wasn’t a politician — he never ran for office before becoming president — and he didn’t know how to reach out to the public and explain his policies. Not hearing anything different, the average U.S. citizen didn’t think that the president cared. So he was voted out of office.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 15-3: Herbert Hoover, 31st president of the United States.

On the other hand, Hoover was quite a man. He was a self-made millionaire and a great humanitarian. Hoover not only organized relief efforts to Europe during and after World War I, but he also became active after World War II when President Truman called him back into service. With these efforts, Hoover literally saved millions of Europeans from starvation.

Hoover’s early career

Hoover was in London when WWI broke out. Right away, he wanted to help. His first task was to bring home the thousands of U.S. citizens that were stranded in Europe. (He assisted over 120,000 U.S. citizens.) Hoover then took on the more demanding job of feeding and clothing thousands of Europeans. From 1914 to 1919, Hoover headed the Commission for the Relief of Belgium. He supervised the distribution of millions of tons of aid to Belgium and northern France.

President Wilson was impressed with Hoover’s activities, so in 1917, he called him back home to become the U.S. food administrator. This position required Hoover to make sure that the United States could feed its military and the Allied troops in Europe. Hoover was so successful that Wilson sent him back to Europe after WWI to help starving Europeans. As the head of the American Relief Administration, Hoover provided food to 300 million people across Europe. By 1920, his job was done. It was time to move on.

Entering politics

When the Republicans retook the White House in 1921, President Harding appointed Hoover secretary of commerce. Hoover reorganized the department and extended federal control over the public airwaves and the airline industry. He also standardized sizes for basic items such as tires, nuts, and bolts.

In addition, Hoover continued to be active in the area of disaster relief. He organized aid to Russia and later took on the Mississippi river flood relief. By 1928, the Great Humanitarian was known to every U.S. citizen.

Becoming president

In 1927, President Coolidge shocked the nation when he refused to run for reelection. Hoover was ready to become president, so he sought the Republican nomination. He received the nomination on the first ballot with no opposition.

The general election was even easier for Hoover. The Democrats nominated Governor Al Smith of New York for the presidency. Smith was Catholic. This topic became a hot campaign issue. Many in the United States believed that a Catholic wouldn’t be loyal to the Constitution because he owed loyalty to the pope. The solid Democratic South was heavily Protestant, and it refused to back a Catholic. When the results of the presidential election came in, Hoover had won in a landslide. He won 444 electoral votes, including five Southern states not carried by a Republican since the end of Reconstruction.

President Herbert Clark Hoover (1929–1933)

Dealing with the Great Depression

By spring 1930, the Great Depression was in full swing. Hoover dealt with the economic situation by implementing the following programs:

- The Agricultural Marketing Act (1929): This act, passed before the Great Depression started, allowed the federal government to make loans to farmers in need. The act also allowed the government to buy their surplus goods, keeping prices for these goods high.

- The Hawley-Smoot Tariff (1930): This tariff increased charges on foreign goods. It led to an international trade war and hurt the world economy.

- The Reconstruction Finance Corporation (1932): This agency provided federal money to banks, railroads, insurance companies, and, later, local and state governments in need.

- The Glass-Steagall Act (1932): This act released government gold reserves to stimulate the economy.

- The Federal Home Loan Bank Act (1932): This act provided for low-interest loans to homeowners who needed money to make their mortgage payments.

Despite all of Hoover’s efforts, the Great Depression got worse. Hoover refused to implement unemployment benefits because he believed that local governments could take care of unemployed citizens. Local governments were, however, broke. Now, 12 million U.S. citizens were unemployed, 5,000 banks had gone bankrupt, and 32,000 businesses had gone under. Hoover’s political career was over.

Burning down Hooverville

The last straw in Hoover’s presidency occurred in 1932. About 15,000 WWI veterans marched to Washington, D.C., to redeem monetary certificates they had received in 1924 as payment for their military service. The certificates were not cashable until 1945.

The Senate refused the veterans’ request to redeem the certificates. Many veterans went home, but approximately 2,000 stayed in Washington, D.C., setting up a tent city called “Hooverville.”

President Hoover ordered General MacArthur and the military to disperse the veterans. General MacArthur did more than that. He went in with tanks and burned down Hooverville. The assault led to the death of a baby.

The public was incensed. Hoover’s career was finished. With elections only months away, Hoover was likely to lose, and lose he did. In the 1932 elections, Hoover won only 59 electoral votes. His Democratic opponent, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, received 472 electoral votes. Roosevelt also won seven million more votes in the popular election than Hoover.

Staying active in retirement

Hoover retired in 1933. He went back to California and became active in charitable organizations. He started the Hoover Library on War and then donated the 200,000 books he acquired to Stanford University.

Later, Hoover toured Europe. He met Hitler and warned the United States of German aggression. In 1939, Hoover went back to the United States to organize relief funds. He provided relief to Finland after it came under attack by the Soviet Union.

After World War II, President Truman asked Hoover to analyze the need for relief in Europe and then provide whatever relief was necessary. Hoover traveled to 38 countries in Europe and again did a superb job.

Truman was impressed with Hoover’s performance, so he asked him to streamline government operations. The Hoover commission completed the job successfully. In 1953, President Eisenhower asked Hoover to start a second commission for the same purpose. Again, Hoover succeeded.

In 1955, Hoover retired at age 81. He died at the age of 90 in 1964.

Warren G. Harding, shown in

Warren G. Harding, shown in  Harding’s years as a senator were undistinguished. He supported the conservative wing of the Republican Party, pushing for higher tariffs and the abolition of the manufacturing and sale of liquor. In 1919, he opposed the Treaty of Versailles, which established the League of Nations. In other words, Harding was a loyal Republican who pleased the party leadership.

Harding’s years as a senator were undistinguished. He supported the conservative wing of the Republican Party, pushing for higher tariffs and the abolition of the manufacturing and sale of liquor. In 1919, he opposed the Treaty of Versailles, which established the League of Nations. In other words, Harding was a loyal Republican who pleased the party leadership. Harding created his campaign slogan, “A Return to Normalcy,” by mistake. He meant to say “normality,” but he misspoke. The term stuck, and the Republican Party used it to convey that they wanted to take the country back to the good old days of pre-World War I America. The slogan sat well with a nation ready to forget about World War I.

Harding created his campaign slogan, “A Return to Normalcy,” by mistake. He meant to say “normality,” but he misspoke. The term stuck, and the Republican Party used it to convey that they wanted to take the country back to the good old days of pre-World War I America. The slogan sat well with a nation ready to forget about World War I. Mrs. Harding didn’t allow an autopsy. So nobody really knows what Harding died of. At the time, there were rumors that Mrs. Harding had poisoned him after finding out about all the affairs her husband had. So far, these rumors haven’t been substantiated.

Mrs. Harding didn’t allow an autopsy. So nobody really knows what Harding died of. At the time, there were rumors that Mrs. Harding had poisoned him after finding out about all the affairs her husband had. So far, these rumors haven’t been substantiated.