Chapter 18

Liking Ike: Dwight David Eisenhower

IN THIS CHAPTER

Serving his country

Serving his country

Retiring from his military career

Retiring from his military career

Becoming president

Becoming president

Dwight David Eisenhower is one of the most beloved presidents in U.S. history. He presided over the booming economy of the golden 1950s when times were good. He ended the war in Korea, prevented the Soviet Union from expanding, and stood up for U.S. rights in regard to U.S. allies. Later in his presidency, he became the godfather of U.S. nuclear military might. At home, Eisenhower built the U.S. interstate highway system and started the long process of desegregation. He was a moderate who appealed to a broad range of U.S. citizens. His political legacy is one of compromise and bargaining.

Eisenhower’s Early Military Career

Eisenhower graduated from West Point military academy in 1915. After World War I (WWI) broke out, Eisenhower went to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, to train a tank corps. After World War I ended, Eisenhower became a career soldier. He was transferred to Camp Meade, Maryland, where he met his lifelong friend, George Patton. Next, in 1922, Eisenhower went to Panama to serve under General Conner, an expert on U.S. military history. Conner renewed Eisenhower’s interest in the topic of U.S. military history and encouraged him to attend the Command and Generals Staff School in Kansas. Eisenhower attended the school and graduated first in his class in 1926. He continued his studies at the Army War College, from which he graduated in 1929.

In 1932, Eisenhower became an aide to General Douglas MacArthur. He went with MacArthur to the Philippines to prepare the island for a possible Japanese attack. In the Philippines, Eisenhower organized his first military unit. He trained native Filipinos and prepared them for independence. (The Philippines, at this point, was still controlled by the United States.) His unit fought with distinction when the Japanese attacked. In 1939, Eisenhower returned to the United States.

Getting ready for World War II

In 1939, WWII broke out in Europe when Germany attacked Poland. The United States slowly became involved in the conflict (see Chapter 16). Eisenhower continued to train troops. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, he was chosen to head the War Plans Division, which put him in charge of planning all U.S. military operations. Eisenhower supported the successful “Europe First” strategy. He believed that it was essential to defeat Germany first, before the United States turned against Japan. Franklin Roosevelt agreed, placing Eisenhower in charge of European operations.

Eisenhower went to Great Britain to organize the Allied offensive against Germany. Eisenhower was ready to invade and liberate France from German control, but British Prime Minister Winston Churchill objected and instead argued for an invasion of North Africa. Eisenhower disagreed with Churchill, but he followed his orders. The invasion of North Africa turned into a disaster at first, when German forces defeated Eisenhower’s troops. It took months for the Allies to recover and finally drive German forces out of North Africa.

Next came the invasion of Italy. Again, Eisenhower disagreed with his superiors and argued against the attack. Eisenhower was right to disagree with his superiors — they should have listened to him. The Allied forces didn’t gain control of Italy until Germany surrendered in 1945.

Liberating France

In December 1943, Eisenhower finally received the command he wanted. He was put in charge of “Operation Overlord,” the invasion of France. As supreme commander of all Allied forces, Eisenhower controlled over 150,000 troops and thousands of aircraft and tanks.

To succeed, Eisenhower had to take a gamble. The Germans expected him to attack in northeastern France. German fortifications were heavy there, and the Allies would have had a tough fight on their hands. But Eisenhower changed plans at the last minute and attacked at Normandy. To fool the Germans, Eisenhower had the Allied Air Force attack the northeastern part of France: He wanted the Germans to believe that he was about to attack there. His gamble paid off. On June 6, 1944, the invasion of France, or D-Day, started at Normandy. By September 1944, Allied forces had liberated France. Eisenhower was an international hero.

Finishing off Germany

After the successful invasion of France, Eisenhower became a five-star general — the highest rank in the army. He didn’t have time to celebrate. Germany launched its final offensive of World War II (WWII) in December 1944. It took Eisenhower three months to stop the attack and go back on the offensive. He entered southern Germany in March 1945. The German military surrendered to Eisenhower on May 7, 1945, ending the war in Europe.

Retiring from the Military

When the war was over, Eisenhower had the unpleasant duty of demobilizing, or releasing soldiers from their military service. In the next two years, the size of the U.S. army shrunk from over 8 million troops down to 1 million troops. Eisenhower was appalled by the massive cutbacks, so he retired from the military in 1948.

Both the Republicans and the Democrats approached Eisenhower to ask him to run for the presidency. He refused. Instead, he wrote a bestseller on his exploits in WWII entitled Crusade in Europe, and he became the president of Columbia University in New York. He served as president of the university for two years, but he didn’t like academia very much.

Defending NATO

In 1950, Eisenhower eagerly accepted President Truman’s offer to head the new North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Eisenhower, a firm believer in NATO, went back to Europe.

Squeaking by

In 1952, Eisenhower was the most popular politician in the United States. Unfortunately, presidential nominees weren’t chosen by the people: They were chosen by a small number of party activists. The party activists supported Taft.

At the Republican presidential convention, a junior senator from California saved the day for Eisenhower. He put pressure on the California delegation, leading them to cast all of their 70 votes for Eisenhower. The junior senator from California was none other than Richard Nixon, who received the vice-presidential nod for his deeds.

Campaigning in 1952

President Truman knew that nobody could beat Eisenhower. Truman actually decided in 1948 that he wouldn’t seek reelection. When Eisenhower became the Republican nominee, Truman almost changed his mind. He figured that he was the only Democrat who might be able to beat Eisenhower. However, in March 1952, he announced that he wouldn’t seek reelection. Eisenhower easily defeated the Democratic candidate, Adlai Stevenson.

Eisenhower’s campaign told the public that only he could end the war in Korea, which had started in 1950. His slogan was simple: “I shall go to Korea.” Both the left and the right loved him for his approach to the war. The right believed that he would invade China to end the war, and the left thought that he would sit down and work out a peace agreement. In addition, Eisenhower proclaimed that he would roll back communism, or liberate countries under communist control. When the votes were in, Eisenhower had won big. He received 55 percent of the vote and won 39 of the 48 states.

President Dwight David Eisenhower (1953–1961)

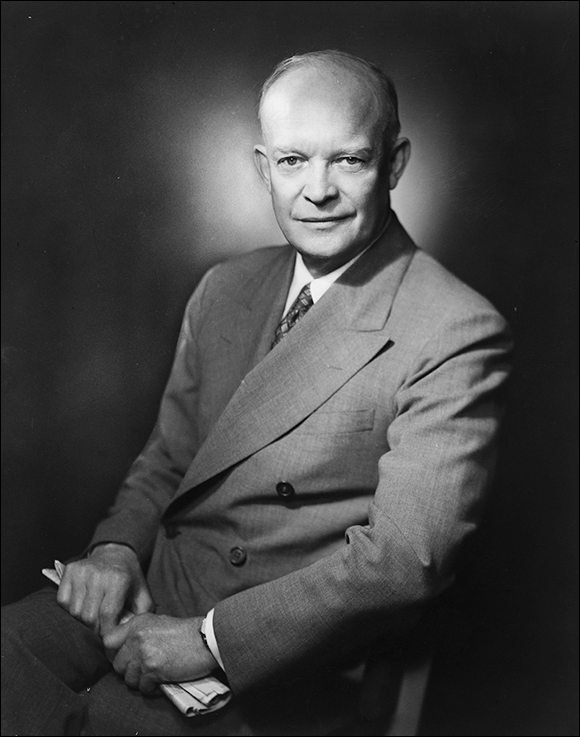

When Eisenhower, shown in Figure 18-1, entered the White House, many conservatives hoped that he would roll back or even destroy the welfare state Roosevelt had created with his New Deal policies. Eisenhower disappointed them. He actually increased the welfare state by including the self-employed in the Social Security program — this added seven million people to social security roles. In addition, Eisenhower increased the minimum wage to $1 an hour and spent heavily on public works projects. It was Eisenhower who provided the money to build our present-day interstate highway system.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

FIGURE 18-1: Dwight D. Eisenhower, 34th president of the United States.

Eisenhower was moderate in the area of civil rights, believing that the states should deal with the issue that was a thorn in his side throughout his presidency. But, when forced into it, Eisenhower acted strongly and provided the foundation for desegregating the country in the 1960s.

Dealing with the Brown vs. the Board of Education case

Early in his term, Eisenhower ignored civil rights. It was an explosive issue that polarized the country, and he didn’t want to upset his numerous supporters in the South. Eisenhower also believed in states’ rights. He claimed that the issue of civil rights was one for the states, and not the federal government, to deal with.

But, in 1954, the Supreme Court forced Eisenhower to deal with the civil rights issue with its landmark ruling in the case of Brown vs. the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. The Supreme Court declared segregation in public schools illegal in the United States, sparking a storm of protest in the South.

Managing military matters

Eisenhower changed U.S. military strategy, mostly as a means to balance the budget, as soon as he entered office. Under Truman, the United States ran a large budget deficit, which Eisenhower considered unacceptable. So he looked for a way to save money. He found it in the military.

Changing nuclear strategy

In 1953, the United States relied upon a large standing army, with nuclear weapons to back up the armed forces. Eisenhower changed this strategy. He knew that nuclear weapons were cheaper than troops, so he cut back the size of conventional forces and increased the number of nuclear weapons in the U.S. arsenal. The change allowed him to balance the budget. However, a new military strategy had to be put into place to justify his cutbacks. The Doctrine of Massive Retaliation was the answer.

At the time, the doctrine seemed a credible way to make the United States safe from a nuclear attack. Although the Soviet Union possessed nuclear weapons, it didn’t have the means to deliver them. Missiles were not yet available, and the Soviets didn’t have any air bases close enough to the United States to launch a strike.

Ending the war in Korea

To the great disappointment of many, Eisenhower did not escalate the war in Korea, which began in 1950 when North Korea invaded South Korea (see Chapter 17). Many conservatives hoped that Eisenhower would invade China to end the war. Eisenhower refused, seeking instead a peaceful solution.

Eisenhower told the Chinese leadership that unless they agreed to an armistice, he would use whatever weapons it took to finish the war, including nuclear weapons. Within months, the war was over.

Getting involved in Vietnam

In 1954, France’s efforts to squash a grassroots movement for independence in Indochina weren’t going well, so they asked Eisenhower for help. (See the “Conflict in Vietnam” sidebar in Chapter 20 for background on Indochina.) Eisenhower refused, stating that “… the jungles of Vietnam would swallow up division after division of U.S. troops.”

Instead, Eisenhower supported peace talks, which resulted in the division of Vietnam in 1954: North Vietnam became a communist state, while South Vietnam turned itself into an anti-communist right-wing dictatorship.

Eisenhower feared that the North might threaten the South. Eisenhower worked to protect the South by helping the South Vietnamese both militarily and economically. He feared that if South Vietnam went communist, the rest of Asia might follow suit. Eisenhower justified U.S. involvement by saying, “You might have the broader consideration that might follow what you would call the falling domino principle. You have a row of dominos set up, you knock over the first one, and what will happen to the last one is the certainty that it will go over very quickly.” Before Eisenhower left office, the United States had military advisors in South Vietnam to train soldiers.

Changing foreign policy

A major change in U.S. foreign policy took place in 1954. Previously, the country had operated under the Truman Doctrine and the idea of containment — the policy of not allowing the Soviet Union to expand any further.

Leading Hungary astray

Hungary put the Rollback Doctrine to a test in 1956 and discovered that it was all talk. Hungary was a part of the Soviet empire that dominated Eastern Europe. In 1956, a new reformist government came to power in Hungary. The leader, Imre Nagy, tried to remove Hungary from the Soviet bloc.

Believing that they could rely upon U.S. help, as the Rollback Doctrine claimed, the Hungarians seceded from the Warsaw Pact. The Soviets weren’t amused: They invaded Hungary. Hungary, hoping for and expecting U.S. aid, fought back.

Help never came — Eisenhower did not want to risk nuclear war — and almost 50,000 Hungarians died in two weeks of fighting before it was all over. Hungary remained communist until 1989.

Disappointing allies over the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal crisis took up Eisenhower’s time in 1956 (see the sidebar in this section titled “The story of the Suez Canal”).

Eisenhower faced a dilemma when Britain and France asked the United States to help defend their rights to control the Suez Canal in Egypt. He didn’t want the United States to appear to be restoring colonialism in the area. Eisenhower didn’t want to help the British and French maintain control in the Middle East, either, so he denied U.S. aid.

Britain and France withdrew from Egypt, and the conflict was resolved peacefully. But France was furious. The new French President Charles de Gaulle pulled France out of NATO and started to build nuclear weapons.

Running for reelection

In 1955, Eisenhower suffered a heart attack and was ready to retire. But the Republican Party pleaded with him to run for reelection. The party knew that he was the only candidate who could beat the Democrats, who had regained control of Congress in the 1954 elections.

Eisenhower begrudgingly agreed to run again. He faced off against Democrat Adlai Stevenson one more time. This time he won big, garnering 57 percent of the vote and 457 electoral votes, compared to Stevenson’s 42 percent of the vote and 73 electoral votes.

Losing the technology race to the Soviets

In 1957, the United States was in for a major shock. The Soviet Union not only perfected missile technology but also put the first satellite (Sputnik) into orbit around the earth. Having nuclear missiles allowed the Soviet Union to target the U.S. mainland for the first time, making the Doctrine of Massive Retaliation obsolete.

Eisenhower replaced the Doctrine of Massive Retaliation with one called Flexible Response. The new doctrine stated that the United States would keep its options open in case of an attack against it or an ally. Eisenhower proclaimed that the United States would reserve the right to use either conventional or nuclear forces.

With the Soviet threat suddenly real, the U.S. populace went into a state of shock and panic. People built bunkers in their backyards to protect themselves and their families in the case of a nuclear attack, and schools held drills teaching children to “duck and cover.”

Eisenhower had to act — and act he did. The navy, air force, and army received money to build nuclear missiles. By 1961, all three branches had missiles, and the United States had regained its military superiority.

Changing military strategy one last time

Eisenhower developed the doctrine of the TRIAD, relying on three different types of nuclear weapons for the defense of the country. The three types were

- Land-based missiles: These were located in silos throughout the country.

- Submarine-based missiles: Eisenhower based these in submarines that were located throughout the world.

- Atomic bombs carried in strategic bombers: These bombers were located in the United States and Europe.

The idea behind TRIAD was simple: If the Soviet Union launched a first strike, it might destroy the U.S. land-based missiles and/or the U.S. bombers before the United States had a chance to launch them. But the missiles in submarines would be intact and could be used to initiate a counterstrike against the Soviet Union. This strategy made an attack against the United States irrational, because the U.S. could still destroy the Soviet Union in a second strike. This strategy is referred to as deterrence.

Facing communism in the backyard

In 1959, the unthinkable happened: A country in Latin America went communist. Suddenly the United States faced a communist country in its own hemisphere. The country was Cuba, where Fidel Castro initiated a communist revolution in 1959. Castro toppled the pro-U.S. dictator, Battista, and established a communist regime in Cuba.

Eisenhower responded fairly aggressively. He drew up plans for an invasion of Cuba, but he didn’t have enough time left in his term to finish the job. So he left it up to his successor.

Trying to negotiate a test ban

Eisenhower wanted to go out with a bang in 1960. He was concerned about the arms race and the possible use of nuclear weapons. He called for a major arms control meeting between the United States, the Soviet Union, Great Britain, and France. Eisenhower wanted to push the Soviet leader Khrushchev into accepting a ban on nuclear testing.

Before the countries were to meet for the conference, a U.S. spy plane was shot down over the Soviet Union, and its pilot, Gary Powers, was captured by the Soviets. Khrushchev wanted Eisenhower to apologize for the incident. When Eisenhower refused to apologize, the arms control meeting was cancelled.

Staying active in retirement

Eisenhower wasn’t able to run for a third term — the Republican party passed the 22nd Amendment in 1951, restricting presidents to serving only two terms. In 1961, Eisenhower retired to his farm in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, to write his memoirs.

In 1960 and 1964, Eisenhower hit the campaign trail for Republican candidates Richard Nixon and Barry Goldwater. He was disappointed when John Kennedy won the presidency in 1960. Eisenhower believed that Kennedy was too young and inexperienced to be a successful president.

Between 1965 and 1969, Eisenhower suffered three more heart attacks. The third attack, in 1969, killed him. Eisenhower died at the age of 78. He is still one of the most beloved presidents in U.S. history. Eisenhower’s last words were “I want to go; God take me.”

Britain wanted Eisenhower to attack the German capital of Berlin before Soviet troops could reach it. Eisenhower refused. He knew that an attack on Berlin would kill thousands of U.S. soldiers. More importantly, the Yalta agreement had already divided the German capital into four zones of occupation. So he would have had to sacrifice thousands of U.S. lives and then give the Soviets their zone. Instead of acting, he sat back and let the Soviets attack and conquer Berlin. The Soviet Union lost over 100,000 men in the attack.

Britain wanted Eisenhower to attack the German capital of Berlin before Soviet troops could reach it. Eisenhower refused. He knew that an attack on Berlin would kill thousands of U.S. soldiers. More importantly, the Yalta agreement had already divided the German capital into four zones of occupation. So he would have had to sacrifice thousands of U.S. lives and then give the Soviets their zone. Instead of acting, he sat back and let the Soviets attack and conquer Berlin. The Soviet Union lost over 100,000 men in the attack. Republican Party politics brought Eisenhower into the presidential race in 1952. The frontrunner for the Republican nomination was Senator Taft of Ohio, who opposed NATO. Eisenhower considered NATO necessary for the survival of a free Europe. Eisenhower feared that without it, the Soviet Union would dominate the whole continent. Eisenhower announced his candidacy for the Republican nomination in an effort to prevent Taft from becoming the nominee.

Republican Party politics brought Eisenhower into the presidential race in 1952. The frontrunner for the Republican nomination was Senator Taft of Ohio, who opposed NATO. Eisenhower considered NATO necessary for the survival of a free Europe. Eisenhower feared that without it, the Soviet Union would dominate the whole continent. Eisenhower announced his candidacy for the Republican nomination in an effort to prevent Taft from becoming the nominee. President Eisenhower was the only president to serve in both WWI and WWII.

President Eisenhower was the only president to serve in both WWI and WWII. Some southern states blatantly refused to accept the decision to start integrating public schools. It was up to Eisenhower to enforce the ruling, which he did in 1957 when the governor of Arkansas, Orval Faubus, called out the National Guard to prevent black children from attending white schools. Eisenhower sent federal troops to Arkansas to enforce the Supreme Court decision and protect the black children from white mobs. As Eisenhower said, “Mob rule cannot be allowed to override the decisions of our courts.”

Some southern states blatantly refused to accept the decision to start integrating public schools. It was up to Eisenhower to enforce the ruling, which he did in 1957 when the governor of Arkansas, Orval Faubus, called out the National Guard to prevent black children from attending white schools. Eisenhower sent federal troops to Arkansas to enforce the Supreme Court decision and protect the black children from white mobs. As Eisenhower said, “Mob rule cannot be allowed to override the decisions of our courts.” The Doctrine of Massive Retaliation was simple. The United States threatened any country that committed an act of aggression against it or any of its allies with a massive nuclear attack. This stance, in turn, ruled out such an attack, because the aggressor faced total destruction.

The Doctrine of Massive Retaliation was simple. The United States threatened any country that committed an act of aggression against it or any of its allies with a massive nuclear attack. This stance, in turn, ruled out such an attack, because the aggressor faced total destruction.