CREATING SURFACES

Personal preferences

Are you someone who likes to build up or to break down? Do you prefer to utilize a found surface such as a textured paper or to work from scratch? Do you tend to want to keep surfaces simple and make the paint effects do most of the work, or do you prefer it when the texture facilitates the painting? You may say quite rightly that it all depends on what kind of surface is required and that you might employ a different technique for each individual case. However, that option depends on your knowing the full range of what’s possible with a wide variety of materials. Generally, people tend to stick to favourites and those they have had most experience with. Their choice may be a reflection of something within the individual personality and integral to other aspects of that person’s work.

We’ve already examined one specialized method of creating surface effects – making latex skin casts in Chapter 3 – and touched upon another – using Kapa-line foam – in Chapter 2. These are my personal preferences. I tend to try to make Kapa-line foam do whatever I want, regardless of whether there might be an easier method, just because it’s familiar to me. However, it’s never too late to become acquainted with something unfamiliar and hopefully this chapter will encourage that.

It also depends a great deal, of course, on what you have to hand, because whereas materials for construction are usually anticipated beforehand and bought in specially, materials for surfacing tend to get overlooked until the time comes. In order not to just ‘make do’ with whatever happens to be in the studio or in the kitchen, a well-stocked arsenal of possibilities might read as follows:

■ Fillers: polyfilla, acrylic texture medium.

■ Special papers: textured vinyl wallpaper, sandpaper, velour, marbled papers, embossed prints.

■ Scatter materials: granulated cork (fine, medium, coarse), vermiculite, sand, poppy seeds, mixed herbs.

■ Cladding materials: obeche wood, cork sheet, Kapa-line foamboard.

The question of how accurately a surface should be represented in scale is an important one. Take sand, for example. If we were to represent it exactly to scale, grain for grain, we would have to use a powder so fine that it would have no visible texture at all. The way sand as a mass is shaped by wind or water is another matter, but the basic texture of flat sand is best represented by fine sand itself or fine sandpaper, regardless of the fact that this is not strictly true to scale. A road or pavement surface of asphalt is a similar case. We can see that it has a certain texture, but at the scale of 1:25 this could, strictly speaking, be accurately represented using paint alone. Yet the effect produced using something with more depth, such as a painted sandpaper or lightly stippled polyfilla, is somehow more satisfying and looks more realistic.

If one nevertheless feels the need to be more specific with scale, it’s sometimes difficult to judge how prominent a texture should be. Even with something as small as a 1:25 chair the thicknesses of individual parts are measurable and, patience willing, controllable in the model. It is more difficult to measure and control the average depth of a texture in the same way. An easy answer is to say that one acquires a ‘feeling’ for the right scale in model work over time. While this is true, it relies on regular model-making and so doesn’t help much at the beginning. One possible solution is to take clear, flat-on reference photos of common surfaces, preferably at times of the day when the light accentuates them. These should be taken with a tape measure or metre rule in view. They can then be printed out at a good resolution, but with the size adjusted to conform to whatever scale one habitually uses, referring to the measurement gauge either to reduce or enlarge the image. Having them around while creating a texture is at least a step in the right direction.

Using fillers and pastes

The brand name Polyfilla has become a blanket term in people’s minds for a range of products, which, although they promise to do much the same thing, will differ considerably in their behaviour. Anyone who’s achieved a specific effect in one type and then tried the same using another will know this. Some fillers (speaking just of the ready-mixed ones) have a higher water content than others and so will only properly adhere to porous or properly ‘keyed’ (roughened) surfaces. They may shrink or crack more when drying and will be reduced almost to a dust at the mere suggestion of sanding. Others may be gritty, hence difficult to smooth out or stipple with, and they will harden like granite.

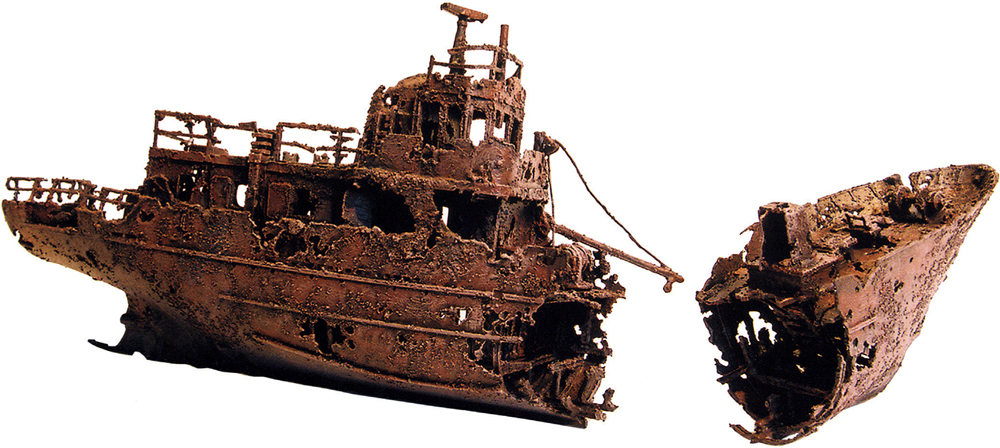

A combination of subtraction and addition was used to create the effects of corrosion on this 1:100 model of a wrecked ship made by David Lazenby. The styrene build was broken down in places using a Dremel tool and fine sand was added to paint for further texturing. Photo: courtesy of Lazenby Design Associates

Good, clear reference photos are an essential basis and it is far better to source a surface and take photos yourself. Here a measuring tape has been included to leave no doubt about size. Photo: David Neat

A page from a surfaces sample book showing different effects in Kapa-line foam. The labels contain details of how the effects were achieved.

MAKING SAMPLES AND KEEPING THEM

An important thing to remember when using a found texture or creating one from scratch is that changing the colour can dramatically alter the appearance of the texture. It is impossible to visualize, for example, how cork mat will look when painted a uniform white, or how a stippled polyfilla surface will change when it’s darkened. It’s even more difficult to anticipate the effect of washes that will give a tonal variation, or the dry-brushing effects dealt with in the next chapter, ‘Painting’. In this context it is therefore essential to make test samples before committing to a solution. In the case of creating a surface stippled in polyfilla, for example, it is important to make more than one test of the same effect, just to ensure that you are in full control of the process, which can vary a lot, simply with the angle of the brush.

Having taken the trouble to make these samples one might as well keep them for future reference, although they are useless if not archived in some handy form including notes on how they were done. There needs to be a conscious commitment to this because it is often the last thing one wants to think about when struggling against a deadline. But the effort in producing a well-documented sample book will be justified not only in terms of one’s own future reference, but also as inspiration and as an aid in dialogue with other people. These samples should not be too small and should be kept to a similar size. It’s easier to appreciate them if they’re mounted on a fairly neutral colour or black. Whenever possible, it’s best to include a little of the painted and the unpainted texture for comparison. The notes may have to be detailed if the surface was created in a specific way, for example in the case of stippling a texture medium, what kind of brush was used, whether the medium was diluted, how many coats, whether the surface was sanded afterwards and whether anything else such as sand was added to the mixture. This may not be obvious from just looking at the sample later and it’s best not to assume that you will remember all the details of how it was done.

Illustrating the variety of effects achievable with just a filler. These have been spread, stippled, impressed with a textured sponge, scraped or sanded. Painting with a thin wash will bring out the texture.