CHAPTER 6

Adjustments to the School Environment

Teachers may receive physician notes indicating that one of their students has sustained a concussion; the physician may recommend academic accommodations. Some notes may be detailed, listing academic accommodations best suited for a particular student and his or her concussion. However, others may provide few details, thereby requiring educators to determine whether the student requires academic assistance and, if so, in what form.

Appropriate environmental and coursework adjustments can be made in a way that allows students with concussion to continue participating in class while also recovering. Students who have sustained concussions typically require short-term adjustments while they are still symptomatic. This chapter opens with a brief discussion of interventions that students who have sustained concussions may receive outside of the school in a rehabilitation setting and at home. Next, appropriate school-based educational plans are discussed in relation to symptom clusters. Extracurricular involvement of students and special grading considerations during recovery are addressed. The chapter also includes guidance to help school teams determine if a child with persistent postconcussion symptoms requires a 504 plan or further evaluation for an individualized education program (IEP). Finally, the chapter concludes with a note on dealing with students who may malinger or continue to report symptoms when they have actually resolved.

INTERVENTION IN A CLINICAL SETTING AND AT HOME

In addition to school-based services, many students who have sustained concussions are actively engaged in rehabilitation in a clinical setting. They may also be receiving medical and pain management in the form of therapy and/or medications. It is helpful when school personnel are fully informed about such treatments so they can provide documentation to other health care providers about any effects—both positive and negative—that are seen at school. For example, a medication may make a student very sluggish at certain points in the school day. Dosage amounts or time of administration may need to be adjusted.

Parents will likely be given recommendations from their child’s physician regarding recommendations for rest and recovery at home. Following are a few common home-based recommendations:

Plenty of rest during the day and plenty of sleep at night.

Plenty of rest during the day and plenty of sleep at night.

No late nights or overnights with friends while symptoms persist.

No late nights or overnights with friends while symptoms persist.

Maintain the same bedtime both on weekdays and weekends.

Maintain the same bedtime both on weekdays and weekends.

Encourage daytime naps or rest breaks when your child becomes fatigued.

Encourage daytime naps or rest breaks when your child becomes fatigued.

Limit activities that require much thinking or concentration. This includes homework, computer work, texting, driving, movies, television, social gatherings, long period of reading, and video games.

Limit activities that require much thinking or concentration. This includes homework, computer work, texting, driving, movies, television, social gatherings, long period of reading, and video games.

Avoid loud environments and loud music, particularly through earbuds.

Avoid loud environments and loud music, particularly through earbuds.

Limit physical activities, particularly those that might result in another blow to the head.

Limit physical activities, particularly those that might result in another blow to the head.

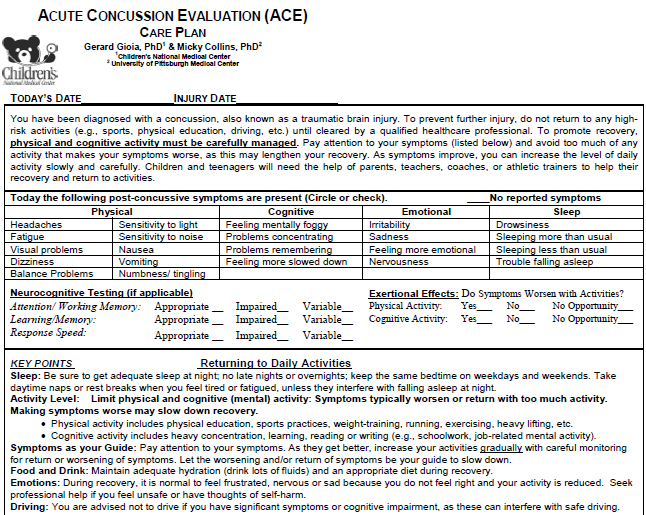

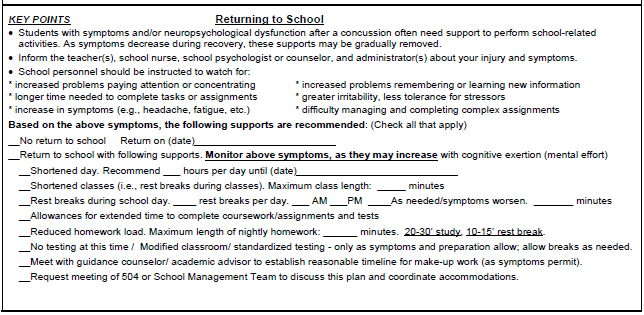

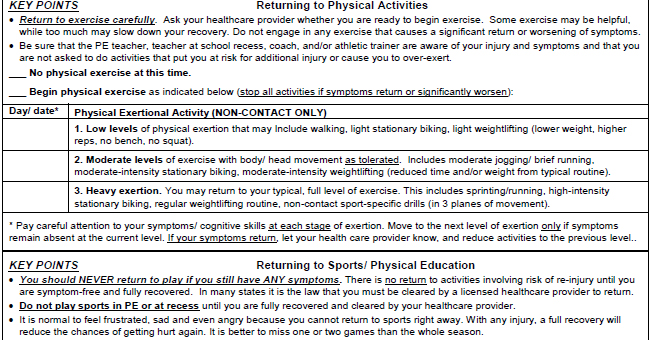

Figure 6.1 is one example of what a care plan, issued by a physician, might look like.

Because the aforementioned activities are what many children spend most of their time doing, parents should also guide their child toward quiet activities that require little cognitive or physical exertion during the acute phase of concussion recovery. A few examples include playing with pets, baking cookies, and visiting with a few friends. With the guidance of a qualified health care professional, parents should monitor their child’s symptoms periodically to guide recovery.

It is relatively common for emergency departments to suggest that students with concussions not return to school until they have been seen by or cleared by a health care provider. Such a suggestion can lead to students being out of school for extended periods of time while waiting to be seen by a doctor. This extended time away from school may not be reasonable or necessary (McAvoy, 2012). Medical professionals may also suggest that students not return to school until they are symptom free. While it is advised that students wait until they are symptom free before returning to sports, they do not need to be symptom free to return to school as long as symptoms are not severe and educators make appropriate school-based adjustments to meet the student’s needs.

Figure 6.1. Acute Concussion Evaluation (ACE) care plan. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: HeadsUp. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/HEADSUP

SCHOOL-BASED POSTCONCUSSION PLANS

The concussed brain requires both physical and mental rest to recover from the injury. A student’s focus and ability to learn can be affected by a concussion. Decreasing cognitive activity through absence from school or shortened class periods can help decrease symptoms and facilitate healing. Further, physical activities after a concussion can magnify existing symptoms and increase the risk of a student sustaining a second concussion before the first has healed. Thus, school-based postconcussion plans should also include provisions to decrease physical activities.

A postconcussion plan uses a particular student’s symptoms to inform educational support. It is helpful to “front-load” academic and environmental adjustments and gradually withdraw them as the student’s condition improves (Halstead et al., 2013). It is important to keep in mind that students may be reluctant to accept adjustments and will instead push through symptoms to complete work. This may be partially due to the anxiety that is associated with work piling up (Halstead et al., 2013; Sady, Vaughan, & Gioia, 2011). This is not healthy for the student.

Adjustments, accommodations, and modifications

Literature related to returning to school while recovering from concussion often refers to academic adjustments, accommodations, or modifications during the recovery process. Sometimes these terms are used interchangeably. However, this book primarily uses the term adjustments. This is to emphasize the temporary and flexible nature of these changes, whether they are adjustments to the school environment or adjustments in academic expectations (McAvoy, 2012). The terms accommodation and modification are commonly used in discussions related to Section 504 plans or IEPs. While these plans can sometimes be instituted for students who have sustained concussions, as is discussed in the next chapter, they are not required for all students who are recovering from concussions. Thus, the words accommodations and modifications are deliberately used sparingly throughout this text.

Some districts may prefer the use of the term “informal accommodations” instead of “adjustments” (reserving the term “formal accommodations” for those implemented with a Section 504 plan). Each reader is encouraged to determine which terms are preferred in their own regions.

General adjustments for most students

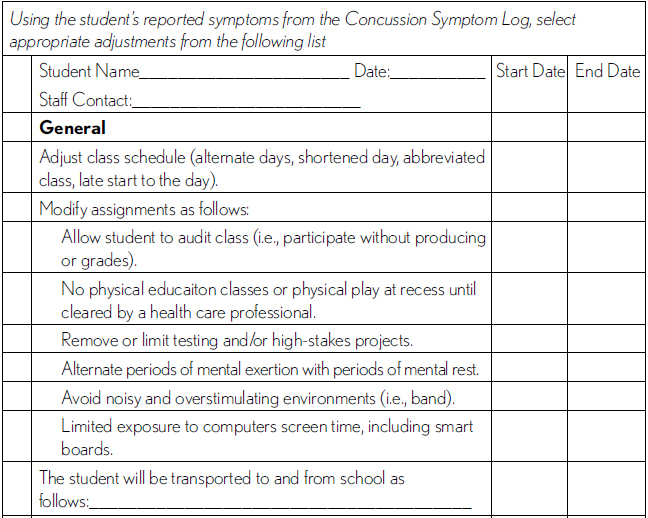

Most students who are recovering from a concussion will benefit to some degree from general alterations to their school day and/or work load. Some of these strategies and considerations are described in the follwoing:

Modified schedule

A modified schedule might involve a shortened day or shortened class periods. For some, the modified schedule might mean that the student only attends core classes instead of electives and/or has rest periods during the day. The student may also start the day late, particularly if his or her school starts very early in the morning. A couple of extra hours of sleep may be particularly healing for the student who is recovering from a concussion.

Modified assignments

Because the concussed brain takes longer to process information and must work harder to do so, it is generally best to allow students to postpone assignments and projects or to complete shortened assignments until they feel better. Grades should be based on this adjusted work. Students who feel well enough to take a test should be permitted to have extended time so their brain has sufficient time to process information.

Prioritize work

As much as possible, avoid having work build up. Students who fall behind in their work can become very stressed and frustrated. This, in turn, can lead to exacerbation of symptoms, particularly emotional symptoms. The concussed student’s brain is overwhelmed by the significant chore of re-establishing neurochemical equilibrium. This can make catching up on schoolwork impossible. Thus, the school concussion team must decide what is essential and what is not. Once the team has decided what work has to be done, written due dates for each academic task can help the student to prioritize work.

One of the greatest gifts that can be given to concussed students is excusals from unnecessary work (McAvoy & Eagan Brown, n.d.). This means that the work is not building up and that the student will not be penalized for not completing it. Perhaps the student can be permitted to “audit” a class during the recovery period, which means participation without producing work or being graded. This may be appropriate for elective classes. Because middle and high school students typically take multiple classes, it can be very difficult for them to make up all missed work. Thus, nonessential work should be waived to help lighten the workload. Following are suggested ways for determining how to modify a student’s work load (Heinz, 2012):

Excused assignments—not to be made up

Excused assignments—not to be made up

Accountable assignments—responsible for content, not process

Accountable assignments—responsible for content, not process

Responsible assignments—must be completed by student and will be graded

Responsible assignments—must be completed by student and will be graded

Transportation to and from school

In most cases, a student recovering from a concussion should not be permitted to drive. A school bus can be a loud environment with lots of physical jostling. Ideally, a parent or other responsible adult would drive the student to and from school during recovery. If this is not feasible, modifications should be discussed that could be implemented for the bus ride, including riding at the front of the bus, wearing earplugs, and/or having a “buddy” to ensure the student is not shoved or bothered.

No physical activity

This is generally described as physical activity that can increase heart rate; this recommendation includes no physical education (PE) class, no physical play at recess, and no athletic practices or games.

Alternate periods of mental rest with mental exertion

This can ensure that the student is not engaging in prolonged periods of cognitive exertion, which can exacerbate symptoms. The periods of mental exertion can be gradually increased as tolerated.

Avoid noisy and overstimulating environments

Upon return to school, it is generally advised that students avoid settings such as band class, busy hallways, and the loud, bright cafeteria if such environments make symptoms increase. This environmental consideration is discussed in more detail in the physical symptom section.

Carly

Although Carly’s concussion recovery was relatively short in duration, her school implemented appropriate adjustments to the school environment during her recovery. She had ample rest time during the school day; her teacher helped her avoid times and places during the day that were loud, bright, and overstimulating. During PE class Carly rested in the nurse’s office. During recess, one of Carly’s friends read books out loud to her. Carly’s mom drove her to and from school for a few days. Mrs. Lang excused Carly from all homework with no penalty and reduced the number of math problems she was asked to complete during class time. Carly was excused from Friday’s written spelling test and told to instead practice spelling the words out loud with her friend during a break.

While the aforementioned adjustments and considerations are generally helpful for most students who are recovering from a concussion, it is also important that the concussion team map accommodations onto specific symptom categories (see Exhibit 6.1).

For students with cognitive symptoms

Minimize distractions

Such students should be allowed to take tests in a quiet room. They can also be given preferential seating in the classroom, typically at the front of the classroom where they can be monitored and have fewer distractions.

Break down or limit assignments

To prevent students from becoming cognitively overwhelmed, give them pieces of assignments that can be completed in small chunks of time (this will vary based on the child’s age and preinjury level of functioning). Consider providing a short break before giving the next piece of the task. Reduce repetition to maximize cognitive stamina. For example, perhaps a student could complete five math problems instead of 20 covering the same material.

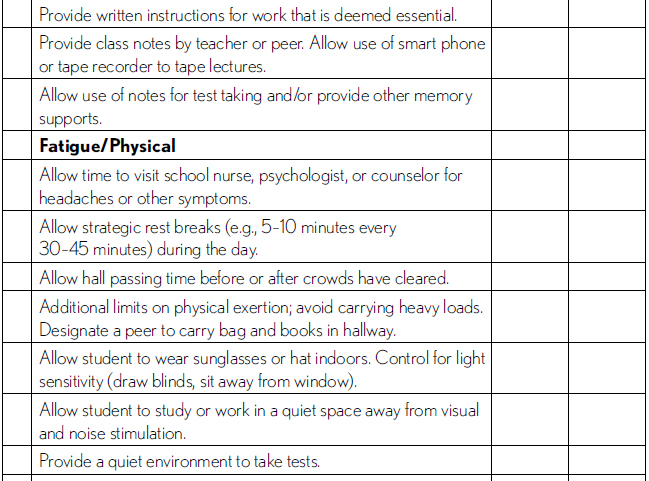

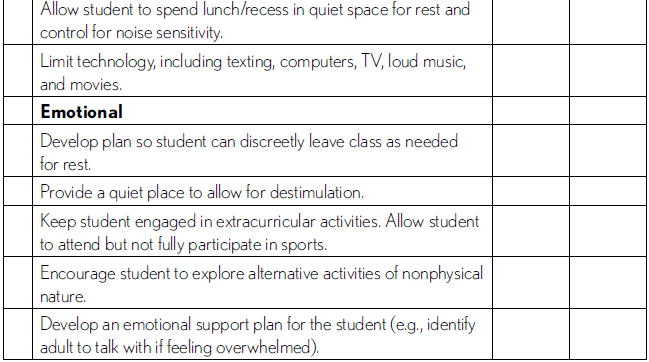

EXHIBIT 6.1

Academic Adjustments for Concussions

Adapted from: brain101.orcasinc.com and http://www.cdc.gov/concussion/headsup/youth.html.

Provide extended time to complete tests and assignments

As mentioned earlier, teachers can excuse certain assignments, and they can adjust due dates or expectations for others.

Avoid substituting mental activities for physical ones

If a child is being excused from physical activity, such as PE class, avoid automatically using that as a time to “make up” school work. Cognitive exertion can be just as exhausting as physical exertion for a student who is recovering from a concussion. Keep in mind the analogy of the student with a broken arm. (If a student had a broken arm and therefore could not complete a lengthy written test, you would not instead have the student play basketball.)

Give written instructions

Processing auditory information and holding information in one’s short-term memory can be difficult for many students, particularly those with concussions. Avoid this by giving concise written instructions, or even having the student write the instructions himself or herself.

Emphasize important information

Dense text on a page can be overwhelming. Use highlighting or color coding to emphasize key passages.

Provide other supports for memory

These might include providing class notes or fact sheets, allowing the student to record class sessions, allowing the student to take open-book or open-note tests, or helping the student develop ways to memorize information (e.g., rehearsal, repetition, mnemonic devices).

Provide assistance in the form of people

A student may benefit from the temporary use of a reader, scribe, note taker, and/or tutor.

Facilitate organization

Educators can help students with concussion use a planner, chart, checklist, or device to keep track of due dates and assignments. They can also check whether a student understands expectations by having the student restate information in his or her own words.

Allow alternative methods for demonstrating knowledge

Allow students to demonstrate their understanding of course material by giving oral rather than written responses.

For students with physical symptoms

Avoidance of sensory overload

If a student has sensitivity to light, he or she should be permitted to avoid bright lights by moving the seat away from windows, dimming the lights in a room, or being allowed to wear sunglasses or a hat. If a student has sensitivity to loud noises, he or she should be excused from classes and events with excessive noise, including band/choir, industrial arts class, pep rallies, assemblies, and dances. It can also be helpful to allow the student to eat lunch in a quiet location rather than the loud, bright cafeteria.

Designate a quiet spot

Allow the student time to rest in the school nurse’s office or to visit the school counselor if he or she is experiencing symptoms such as headaches. Strategic rest breaks (e.g., 5–10 minutes every 30 minutes) might be scheduled during the day for prevention of symptoms. Provide a quiet environment for taking tests, as well as a quiet work space for studying and completing schoolwork away from visual or noise stimulation.

Limit technology

Students with physical symptoms should also avoid or limit texting, computers, TV, loud music, and movies (especially 3D movies).

Excuse from activities that require exertion

Until physical symptoms have resolved, the student should not participate in gym, sports practice, or carry heavy loads (such as stacks of books).

For students with emotional, behavioral, or social symptoms

Allow breaks from the environment

Allow the student to leave the room without penalty if a situation becomes frustrating or the student becomes emotional. Concussion recovery can be emotionally taxing and the experience of crying in front of classmates can be traumatic for some students.

Encourage seeking help

The school psychologist, counselor, or social worker can be a tremendous source of emotional support for the student during the school day. Make sure the student meets and becomes familiar with this person before there is a highly charged emotional situation. Encourage the student to communicate difficulties to his or her parents or another trusted adult.

Monitor peer relations

A student may feel isolated from peers and social networks. School personnel, particularly school psychologists or counselors, can talk with students about these issues and provide support or encouragement. Keep the student engaged in extracurricular activities as appropriate. For example, a student might be permitted to attend, but not fully participate in, sports practice and games.

Encourage alternative activities

Help the student explore activities of a nonphysical nature that can provide social engagement and peer support.

Avoid singling out the student in front of peers

All teachers and concussion team members should be encouraged to provide these adjustments and supports as privately and unobtrusively as possible.

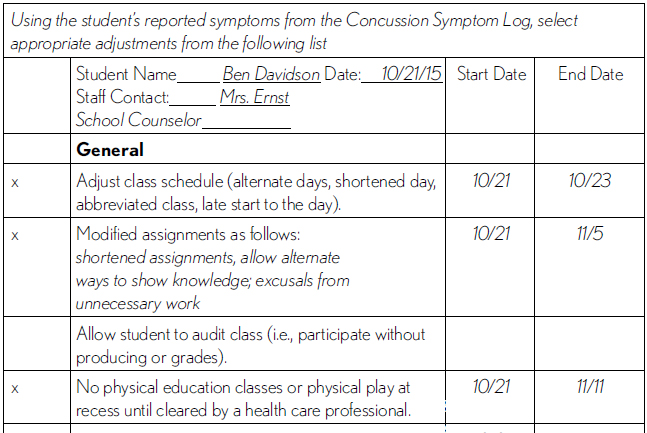

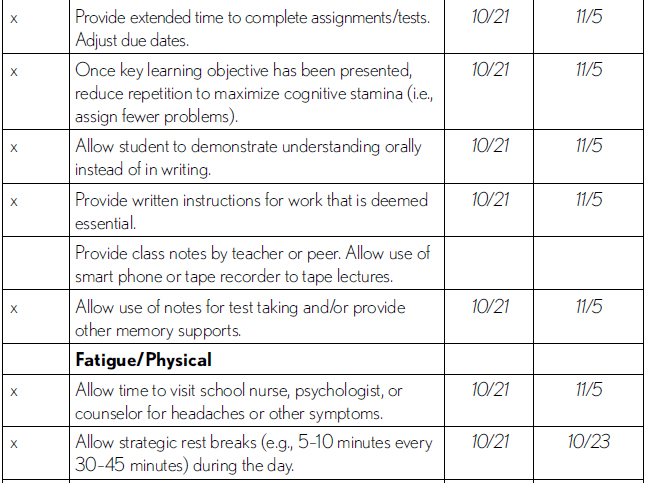

Ben

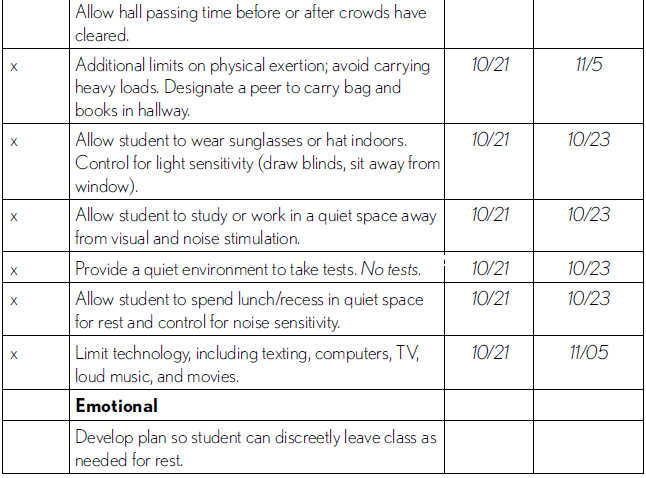

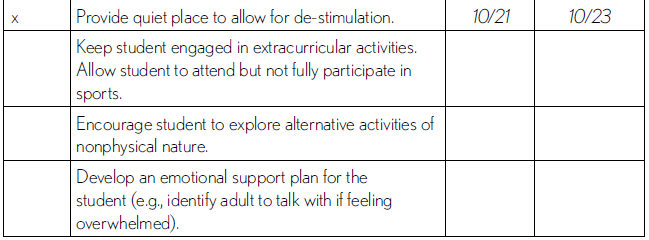

The concussion team at Ben’s school completed the Concussion Symptom Tracking Log seen in Chapter 4. The following academic adjustments were selected based on the type and duration of symptoms he was experiencing. Adjustments were generously applied during the first couple of days when symptoms were still mild to moderate; however, during the second and third week of recovery, they were decreased (see Exhibit 6.2).

EXHIBIT 6.2

Ben’s Academic Adjustments for Concussions

DECISION MAKING DURING RETURN TO ACADEMICS

Learning new material can be very difficult for a student who is recovering from a concussion. This is because the concussed brain is recalibrating neurons that have gone out of whack. Thus, teachers need to be sensitive to the fact that while students need to be accountable for course objectives, the concussed brain is compromised. It is not efficiently processing new learning. Information presented to students while they are recovering from concussions is difficult to convert into memory and conceptualize overall. Educators can allow participation at school to an extent that does not worsen symptoms. As academic adjustments are no longer needed, the concussion team leader (CTL), in collaboration with other members of the concussion management team (CMT), can withdraw a student’s academic adjustments. The end date of each adjustment should be noted on the Academic Adjustments for Concussions form.

Cognitive demands can gradually increase as long as there is no change in symptoms. However, if symptoms increase or worsen, the activity should be discontinued and the student should be permitted complete cognitive rest for 20 minutes. If symptoms improve with this rest, the student can restart the activity at or below the same level that produced symptoms (Nationwide Children’s Hospital, 2012).

For example, Ben was working on math problems at his desk and began to get a headache. His teacher had him stop working on the math sheet and sent him down to the nurse’s office to lie down for 20 minutes and his headache went away. When he returned, he only had five problems left, so his teacher had him complete the sheet and then resume regular activities with the rest of the class.

If the symptoms do not improve even with 20 minutes of rest, the student should discontinue the activity and resume when symptoms have lessened, such as the next day. So, using the aforementioned example, if Ben rested in the nurse’s office for 20 minutes and his headache did not improve, he should have been sent home, been allowed to continue to rest in the nurse’s office, or perhaps been permitted to return to the classroom for an activity involving less cognitive exertion, such as listening to an audio book or watching his teacher lead a science experiment.

EXTRACURRICULAR INVOLVEMENT DURING RECOVERY

The concussion team may need to discuss the student’s extracurricular involvement during the recovery period. It can certainly be upsetting for teachers to put great effort into accommodating the concussed student’s needs in the classroom and then see that same student running up and down the bleachers, socializing at a school football game on Friday night while the loud band plays in the background.

Every student’s situation varies depending on the student’s age, level of involvement with extracurricular activities, and the nature of concussion symptom severity and duration. A blanket policy banning all social activity and extracurricular involvement for prolonged periods of time can exacerbate feelings of depression, anxiety, isolation, and despair.

It might be most helpful to significantly restrict extracurricular involvement—including something as simple as after school meetings—during the acute recovery phase, allowing the student to put all of his or her energy into getting better and performing as well as possible at school. However, if recovery is protracted for weeks or months, it may be beneficial for the student to have some extracurricular involvement added to the recovery plan to keep him or her socially engaged and upbeat.

In such a case, the concussion team might discuss activities in terms of their likelihood of provoking symptoms. Playing percussion in the band might exacerbate headaches, while participating in after school student council meetings might not be a problem. A field trip to an amusement park would not likely be advised, but one to a nature center would not be as likely to provoke symptoms. In such a situation, it would be ideal if a parent could drive the student in order to avoid the bumpy bus ride and also serve as an extra chaperone—not one relied on for supporting other children—so the student could be taken home early if necessary. If there is a once-in-a-lifetime event such as prom or graduation, the concussion team might discuss how the student can participate safely, perhaps by wearing earplugs, attending for a shortened period of time, and not dancing (McAvoy & Eagan Brown, 2015).

SPECIAL GRADING CONSIDERATIONS

Whether a student is newly injured or has been struggling with concussion symptoms for months, it can be difficult for teachers to determine whether to administer exams and how to assign grades. Again, there are no hard and fast rules, but the following considerations can help guide a school team’s decisions on this issue.

Regarding exams, it is important that teachers consider the reasons tests are administered. Generally the purpose is both to evaluate a student’s mastery of the class material and to facilitate the assignment of a grade for that quarter. When a student is in the acute stages of recovering from a recent concussion, the process of taking an exam might exacerbate symptoms and prolong recovery. Further, because of fatigue and slow processing, an exam is unlikely to yield an accurate representation of the student’s knowledge of the subject matter. Additionally, the student may have missed school immediately after injury and may have missed content coverage, thereby leading to gaps in his or her knowledge. Essentially, it might not be fair to test the student on the material and, in fact, it might make symptoms worse.

In such situations, a teacher might consider exempting the student from the midterm or final examination altogether and base the student’s grade on work completed prior to the concussion. If insufficient work was completed before the end of the grading period to justify a grade, the teacher might consider another way to evaluate the student’s mastery of the course content. For example, instead of taking a lengthy written test, perhaps the student could complete an oral examination or multiple choice test, both of which are less cognitively taxing.

Some students might not want to have their grade based on work completed prior to the concussion because they were hoping to bring their grades up with final exams. Rather than having such students push through a final exam schedule, it might be beneficial to space out exams, allowing for ample rest between tests, and to limit this to only one or two classes.

For students who are struggling with prolonged symptoms or who may have missed a great deal of class and/or received adjustments for months, teachers may question whether they have mastered the course content sufficiently to pass the class. Assigning a grade for such students can be difficult. In such situations, teachers are advised to talk with one another and seek guidance from an administrator and the concussion team. Planning ahead for the last month of instruction can be helpful, as the teacher can determine the essential knowledge required for the student to exit the class. If the student has not received that instruction, the material must be retaught before it can be assessed and graded. McAvoy and Eagan Brown (2015) offer the following strategies on how to do this:

Focus on essential material in the last month before grading

Focus on essential material in the last month before grading

Reduce semiessential material

Reduce semiessential material

Remove nonessential material altogether

Remove nonessential material altogether

Forget about “make-up” work unless it is essential to current knowledge

Forget about “make-up” work unless it is essential to current knowledge

Once the student has received the essential knowledge for course completion, the teacher can then determine the best way to assess that knowledge. Again, it is important to avoid having work build up, as that can be incredibly stressful for students recovering from concussions. Suggestions can be given to the student to help reinforce skills and knowledge, but a report card full of incompletes and work building up from one semester to the next will be counter-productive for concussion recovery.

Damien

Damien missed weeks of instruction after his car accident. Then, once he returned to school, his concussion interfered with his ability to learn new material and to complete work that was on par with his classmates. He had six teachers and, without the guidance and support of a concussion team, they struggled to determine how to assign his grades for the semester.

His English teacher allowed him to do an oral report on Of Mice and Men instead of the written report everyone else completed. The class took a test every Friday on sentence structure/compound sentences; the teacher did not count the grades for the tests administered on the days Damien was absent. When he was present, Damien took the tests, which had four multipart questions and took about 20 minutes to complete—and he did well on them. She graded Damien’s in-class work on the days he was present, which involved participating in group discussions and answering written and oral questions in class. She provided study guides that had the answers filled in rather than requiring that he complete them as homework. Damien earned a B+ in the class, which was the same grade he had before his car accident.

Damien’s history teacher also made appropriate adjustments during his recovery period. Students completed packets in class, which was part of her regular instruction, and did not exacerbate Damien’s symptoms. For the final exam, Damien was given a multiple choice test instead of an essay exam. He earned a B in the class.

Damien’s science teacher typically had the class do an activity each day, which involved a project with classmates at Damien’s table. They completed analysis questions, discussed how the experiment worked, and related their findings to scientific principles. Because much of his science grade was based on these activities, and Damien’s teacher had no way of having him make up these activities, Damien’s teacher based his grade for this part of the class on the days he was there. This was helpful, as he did well with these hands-on group projects. However, Damien struggled to remember information on the tests and did not consistently turn in his homework. He earned a C in science.

Spanish was difficult for Damien, as it involved a great deal of drill and practice and new learning. There was a great deal of in-class packet work and the prolonged cognitive exertion made his symptoms flare. Damien was expected to complete all the same work as other students, and received no adjustments. He failed his exam and dropped Spanish after the first quarter.

Damien played trombone in the school band. The pressure of blowing into his trombone plus the cacophony of the band was excruciating. Damien almost always ended up with a headache after band class. The class included “challenges” of people in higher chairs and he fell from second chair to last. He dropped band.

His math teacher said that because Damien was at school, he was responsible for all the same work as everyone else—same classwork, same homework, same tests. Damien failed math that quarter.

SPECIAL PLANS FOR STUDENTS WITH PERSISTENT PROBLEMS

Most students only require temporary, informal academic adjustments after a concussion. If managed appropriately, concussion symptoms should resolve within a few weeks. However, the nature of the concussion, the student’s history of concussions, and other pre-existing conditions can all affect recovery. Approximately 10% to 20% of students who have sustained concussions may have symptoms that extended beyond 3 or 4 weeks (Collins, Lovell, Iverson, Ide, & Maroon, 2006).

If a student’s concussion symptoms persist, academic accommodations and student support may be provided through multi-tiered systems of support, a more formalized health plan, or through options provided under federal law: Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 or, in very rare cases, an IEP under the Individuals with Disabilities in Education Act (IDEA, 2004). The process of qualification and types of plans may vary from state to state.

Multitiered systems of support

A multitiered system of support (MTSS), sometimes referred to as response-to-intervention (RTI), is a stepwise progression of intervention services that allows school professionals to provide interventions of increasing intensity to students who are identified as needing them most. At each level, school professionals use ongoing assessment to determine whether additional support or instruction is needed.

MTSS is a continuum along which student needs are met. By using problem-solving processes, educators can analyze why a student is struggling and determine which interventions are most appropriate.

In concussion cases, the majority of students will be responsive to general short-term academic adjustments. However, some students will continue to experience symptoms that interfere with their educational performance. In such cases, more targeted interventions or academic accommodations (beyond temporary minor “adjustments”) may be required. In very rare concussion cases, a disability may be identified that requires intensive supports such as special education services and long-term modification of the curriculum.

Section 504 plans

Because most concussions resolve within a few weeks, short-term adjustments at school can be arranged without the need for a formal 504 plan (Popoli, Burns, Meehan, & Reisner, 2014). However, if a student requires significant academic adjustments for a prolonged period of time or attendance is significantly compromised, the school might consider formalizing adjustments into a Section 504 plan—essentially making the academic adjustments into an accommodation plan (McAvoy, 2012). Accommodations described in a 504 plan would be similar to those described earlier, such as environmental adaptations and behavioral strategies.

Section 504 is part of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, which was designed to protect the rights of individuals with disabilities in programs and activities that receive federal funding from the U.S. Department of Education. Section 504 requires that school districts provide a free and appropriate public education (FAPE) to students with disabilities regardless of the nature or severity of the disability. This act helps to ensure that students who have disabilities—including disabilities those that are not severe enough to warrant an IEP—receive services and accommodations to meet their educational needs.

Some parents or school teams erroneously believe that a child with a concussion must immediately receive a 504 plan if the child requires accommodations upon return to school. Many students with concussions will not have symptoms of sufficient severity or duration to qualify for a 504 plan. Thus, a medical diagnosis of concussion does not automatically mean that a child should receive a 504 plan. The medical disability must cause substantial limitation to one or more major life activities, such as learning.

If a 504 plan is deemed appropriate for a given student’s situation, it is advised that the school concussion team determine which problematic symptoms require accommodations and tailor appropriate interventions accordingly. In such cases, communication among the family, school team, and medical providers must be coordinated, documented, and ongoing—this is a student who is expected to get better and who should eventually no longer require the plan (more information about Section 504 law is available at www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/504faq.html).

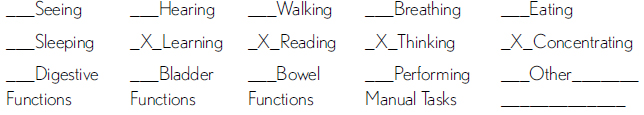

Julia

Julia’s symptoms persisted for 3 months and did not show signs of abating. In collaboration with Julia’s parents, her school team ultimately decided to write a 504 plan for Julia, formalizing the adjustments she had been receiving into accommodations (see Exhibit 6.3). Different districts will have different formats and procedures for these plans. Whereas some students’ 504 plans for other disorders might be reviewed and revised on an annual basis, Julia’s team reviewed her 504 plan monthly because of the expectation that her symptoms would eventually diminish.

EXHIBIT 6.3

Julia’s Academic Accommodations With a 504 Plan

Student’s Name Julia Martinez DOB 4/02/99

School Kennedy High School Parent’s Name Rebecca Martinez and Alfonso Perez

Grade 11 Date of Plan Initiation 3/15/16

Sources of Evaluation Information:

Medical diagnosis of concussion—Children’s Hospital Medical Center; see attached medical information

Ongoing monitoring of symptoms and results of academic adjustments—Kennedy HS concussion team; see attached

Specify the qualifying physical or mental impairment: Concussion

Check affected major life activities:

Accommodation Needed

No physical education class or vigorous physical activity

Avoidance of loud and overstimulating environments; excused from assemblies, permitted to eat lunch in classroom

Take tests in a separate setting and provide extended time

No more than one test per day

Allow rest breaks in nurse’s office without penalty

Reduce class assignments and homework to critical tasks only; exempt nonessential work; base grades on adjusted work

Allow option of demonstrating understanding of material orally rather than in writing when possible

Give paper copies of notes from smartboard or lectures

Individualized education programs

If a disability adversely affects a student’s educational performance, that student may be eligible for an IEP under IDEA (2004). Every school district is responsible for finding and identifying students with disabilities; therefore, if the severity and duration of concussion symptoms warrant a full evaluation, the school team might consider eligibility under the special education category of “traumatic brain injury” (TBI). This is preferable to a less specific eligibility category, such as “other health impairment” (OHI), although the team does need to evaluate all areas of suspected need and consider whether alternative classifications might be more appropriate.

Students who are eligible for IEPs under the TBI category may require significant modifications to the curriculum in order to be successful academically. The IEP may include adjustments to a student’s workload, instructional delivery, or instructional environment. As such, students may receive part of their instruction in a separate classroom, taught by a special educator. The vast majority of students who sustain concussions will not require an IEP. However, a student who has sustained multiple concussions and thereby sustained permanent impairment may require this level of support.

By implementing an effective plan upon returning to school (including a return to school concussion management protocol and a mechanism for monitoring symptoms to allow for fine-tuning of adjustments), the school team can more easily determine whether a more formal action such as a Section 504 plan or full evaluation under IDEA is warranted (Zirkel & Eagan Brown, 2015).

STUDENTS WHO MALINGER

The vast majority of students who have experienced a concussion have legitimate symptoms and may try to hide how awful they feel. However, a few may exaggerate or feign illness in order to escape work, continue receiving academic adjustments, to get attention, or to avoid resuming their sport. This is made particularly difficult by the fact that concussion symptoms are subjective. Frankly, it can be difficult to know when a student is lying.

If a student has medical documentation of a concussion, he or she should be helped as much as the school is able to provide assistance. Communication among the concussion team members—all facets, including parents, the medical team, the academic team, and the athletic team—can help identify students who are malingering or trying to take advantage of the situation. If a concern about the legitimacy of a student’s reported symptoms arises, the concussion team can meet to determine what steps should be taken. Direct communication among team members—including the student’s parents—and documentation by the CTL can be helpful.

Ben

Even though Ben was only in elementary school, his father had great football aspirations for his son. In fact, Ben was never really interested in the sport and played largely to please his father. Although Ben’s concussion symptoms had resolved months earlier, at the start of the new practice season, Ben told his mother that his headaches and dizziness had returned.

Ben’s mother shared this with the school counselor, Ms. Ernst, who was also the CTL, and asked her to check in with Ben to see if he had additional symptoms that emerged in the classroom. As Ms. Ernst talked with Ben, she realized she was uncovering a problem between Ben and his dad. Ben did not want to play football again. He did not enjoy the sport and he was afraid of being injured again. Through his experiences the previous year, Ben learned that symptoms were a way out of football. When he had headaches and dizziness, he did not have to go to practices or play in games. Ms. Ernst talked more with Ben about how he was feeling and helped him feel safe in his discussion with her.

At one point, Ms. Ernst asked, “Do you enjoy playing football?”

Ben looked down, “Not really.”

“Whose idea was it to play last year?” Ms. Ernst asked.

“My dad’s,” Ben said. “A paper came home from school about it and he saw it on the counter. I wouldn’t have asked to do it, but he was real excited. He talked all about how he used to play in school.”

“Are there other sports you’d rather be playing?”

Ben looked up. “Well, a few of my friends are doing the running club that Mr. Caulfield and Ms. Lamb have started.” He paused. “I don’t think running would give me headaches. It would probably make me feel better.”

Ms. Ernst knew that if Ben were truly re-experiencing concussion symptoms that any rigorous physical activity would be prohibited. But she suspected that Ben might be using symptoms as a ticket out of the fall football season. At the same time, she knew that her experiences with concussion was managing the educational side of helping students with concussion symptoms safely return to school. She was not a doctor and didn’t want to make assumptions about Ben’s medical condition.

“Have you talked with your parents about this?” she asked.

“No,” said Ben. “My dad is all excited about me playing football this year. He even talked about maybe helping coach my team.”

Ms. Ernst talked a bit more with Ben and together they decided she would speak to his mother before the end of the school day to share Ben’s reluctance about resuming play on the football team. His mother was, in fact, relieved, as she did not want Ben playing football anymore either.

“His dad got his chance to play when he was in high school,” she said. “This is Ben’s life and he gets a say in the sport he wants to play.”

REFERENCES

Collins, M., Lovell, M. R., Iverson, G. L., Ide, T., & Maroon, J. (2006). Examining concussion rates and return to play in high school football players wearing newer helmet technology: A three year prospective cohort study. Neurosurgery, 58(2), 275–286. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000200441.92742.46.

Halstead, M. E., McAvoy, K., Devore, C. D., Carl, R., Lee, M., Logan, K., … Council on School Health (2013). Returning to learning following a concussion. Official Journal of the American Pediatrics, 132(5), 948–957. doi:10.1542/Peds.2013-2867.

Heinz, W. (2012). Return to function: Academic accommodations after a sports-related concussion. The OA Update, 4(2), 16–18.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act, 20 U.S.C. § 1400 (2004).

McAvoy, K. (2012). Returning to learning: Going back to school following a concussion. NASP Communique, 40(6), 1, 23–25.

McAvoy, K., & Eagan Brown, B. E. (2015). Get schooled on concussion. Retrieved from http://www.getschooledonconcussions.com/topic-log.html

Nationwide Children’s Hospital. (2012). A school administrator’s guide to academic concussion management. Retrieved from http://www.nationwidechildrens.org/concussions-in-the-classroom

Popoli, D. M., Burns, T. G., Meehan, W. P. III., & Reisner, A. (2014). CHOA concussion consensus: Establishing a uniform policy for academic accommodations. Clinical Pediatrics, 53(3), 217–224. doi:10.1177/0009922813499070.

Sady, M. D., Vaughan, C. G., & Gioia, G. A. (2011). School and the concussed youth: Recommendations for concussion education and management. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America, 22(4), 701–719. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2011.08.008.

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, 34 C.F.R. Part 104.

Zirkel, P. A., & Eagan Brown, B. E. (2015). K-12 students with concussions: A legal perspective. The Journal of School Nursing, 31(2), 99–109. doi:10.1177/1059840514521465.