LESSON 4

What’s the Weather Like?

天気はどう?

Tenki wa Dō

In this lesson you will learn how to describe weather and climate, how to conjugate adjectives and verbs, and the important distinction between plain forms and polite forms.

|

[cue 04-1] |

Basic Sentences

1. |

今日は暑いです。昨日も暑かったです。明日はどうでしょう。 Kyō wa atsui desu. Kinō mo atsukatta desu. Asu wa dō deshō. It’s hot today. Yesterday was hot also. I wonder how the weather will be tomorrow. |

|

2. |

雨が降るから,うちにいましょう。 Ame ga furu kara, uchi ni imashō. Because it will rain, let’s stay home. |

|

3. |

雨が降ったから,うちにいました。 Ame ga futta kara, uchi ni imashita. Because it rained, I stayed home. |

|

4. |

天気がよくなったから,外に遊びに行きました。 Tenki ga yoku natta kara, soto ni asobi ni ikimashita. Because the sky cleared up, I went out for fun. |

|

5. |

山田さんは優しいし, 頭がいいし, きれいだし。 Yamada-san wa yasashii shi, atama ga ii shi, kirei da shi. Ms. Yamada is kind, smart, and pretty…. |

|

6. |

冬になると雪がよく降ります。 Fuyu ni naru to yuki ga yoku furimasu. When the winter comes, it snows very often. |

|

7. |

今もまだ雪が降りつづいています。 Ima mo mada yuki ga furi-tsuzuite imasu. It is still continuing to snow now. |

|

8. |

「日本では雪が降りますか。」 “Nihon de wa yuki ga furimasu ka.” “Does it snow in Japan?” |

「場所によって違います。」 “Basho ni yotte chigaimasu.” “It is different depending on the place.” |

9. |

「スキーをしたことがありますか。」 “Sukī o shita koto ga arimasu ka.” “Have you (ever) skied?” |

「いいえ, ありません。」 “Īe, arimasen.” “No, I haven’t.” |

10. |

「ここは洪水になることがありますか。」 “Koko wa kōzui ni naru koto ga arimasu ka.” “Do floods occasionally occur here?” |

「はい, あります。」 “Hai, arimasu.” “Yes, they do.” |

11. |

いつ庭掃除をするつもりですか。 Itsu niwa-sōji o suru tsumori desu ka. When do you intend to sweep the yard? |

|

12. |

だんだん涼しくなってきましたね。 Dandan suzushiku natte kimashita ne. It is gradually getting cooler. |

|

13. |

「そちらの天気はどうですか。」 “Sochira no tenki wa dō desu ka.” “How is the weather there (in your place)?” |

「今日は曇っていますよ。」 “Kyō wa kumotte imasu yo.” “It’s cloudy today (here).” |

14. |

兄はもう結婚しています。 Ani wa mō kekkon shite imasu. My big brother is already married. |

|

15. |

田中さんはまだ来ていませんね。 Tanaka-san wa mada kite imasen ne. Mr. Tanaka has not come yet. |

|

16. |

傘を持っていった方がいいよ。 Kara kasa o motte itta hō ga ii yo. It’s better to bring an umbrella. |

|

17. |

テレビがつけてあります。 Terebi ga tsukete arimasu. The TV is turned on. |

|

|

[cue 04-2] |

Basic Vocabulary

WEATHER

晴れ hare |

clear sky |

曇り kumori |

cloudy sky |

風 kaze |

wind |

雨 ame |

rain |

小雨 kosame |

drizzle |

雪 yuki |

snow |

霧 kiri |

fog |

雷 kaminari |

thunder |

日 hi |

the sun |

SKY

空 sora |

sky |

青空 azora |

blue sky |

曇り空 kumori-zora |

cloudy sky |

夕焼け空 yūyake-zora |

the sky at sunset |

TEMPERATURE & HUMIDITY

寒い samui |

is cold |

暑い atsui |

is hot |

暖かい atatakai |

is warm |

涼しい suzushii |

is cool |

蒸し暑い mushi-atsui |

is hot and humid |

SEASONS

春 haru |

spring |

夏 natsu |

summer |

秋 aki |

fall |

冬 fuyu |

winter |

梅雨 tsuyu |

rainy season |

WEATHER-RELATED ITEMS

傘 kasa |

umbrella |

レインコート reinkōto |

raincoat |

レインブーツ reinbūtsu |

rain boots |

手袋 tebukuro |

gloves |

ミトン miton |

mittens |

マフラー mafurā |

scarf |

レッグウォーマー reggu wōmā |

leg warmer |

ISLANDS IN JAPAN

北海道 Hokkaidō |

Hokkaido |

本州 Honshū |

Honshu |

九州 Kyūshū |

Kyushu |

四国 Shikoku |

Shikoku |

沖縄 Okinawa |

Okinawa |

CULTURE NOTE Weather in Japan

Japan consists of four major islands: Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, and Shikoku, and nearly 7,000 islands in all, including numerous tiny islands where no one can live. The total land area of Japan is 145,902 square miles (380,000 square kilometers), only 1/25 of the total area of the United States. Most of the land is mountainous, and the flat portion where people can live is very limited. Japan is a small country, but it is long. Japan can be seen as a chain of islands that goes northeast to southwest and measures about 1,700 miles (3,000 kilometers) in length. Japan’s northern end is near 45° N., about the same as Montreal, Canada, and its southern end is near 20° N., about the same as the southern part of Florida. As might be expected, the climate is very different across the country. Everywhere in Japan except Hokkaido has a rainy season, called tsuyu. In Tokyo, it rarely snows, but its summer is quite muggy. Hokkaido is dry, but its winter is severe. Most of the northern areas suffer from high accumulations of snow in winter. Kyushu and the southern islands including Okinawa have very mild winters but very hot summers.

COLORS

赤 aka |

red color |

赤い akai |

is red |

青 ao |

blue color |

青い aoi |

is blue |

黒 kuro |

black color |

黒い kuroi |

is black |

白 shiro |

white color |

白い shiroi |

is white |

ピンク pinku |

pink |

オレンジ orenji |

orange |

SHAPES, SIZES, AND QUALITIES

丸・円 maru/en |

circle |

丸い marui |

is round |

四角 shikaku |

square |

四角い shikakui |

is square |

大きい ōkii |

is big |

小さい chīsai |

is little |

長い nagai |

is long |

短い mijikai |

is short |

いい ii |

is good |

悪い warui |

is bad |

だめ(だ) dame (da) |

(is) no good, won’t do |

VERBS

晴れる・晴れます hareru/haremasu |

(the sky) gets clear |

曇る・曇ります kumoru/kumorimasu |

(the sky) gets cloudy |

降る・降ります furu/furimasu |

(rain or snow) falls |

寝る・寝ます neru/nemasu |

goes to bed, sleeps |

遊ぶ・遊びます asobu/asobimasu |

enjoys oneself |

休む・休みます yasumu/yasumimasu |

rests |

急ぐ・急ぎます isogu/isogimasu |

hurries |

開く・開きます aku/akimasu |

(something) gets opened |

開ける・開けます akeru/akemasu |

opens (something) |

こわれる・こわれます kowareru/kowaremasu |

(something) gets broken |

こわす・ こわします kowasu/kowashimasu |

breaks (something) |

Structure Notes

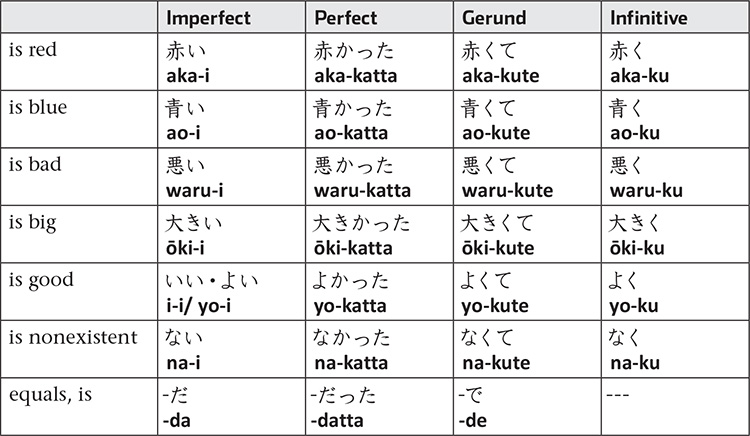

4.1. Adjectives

There are three classes of inflected forms in Japanese: verbs, adjectives, and the copula. You have observed the similar inflections of the verbs (shimasu, shimashita, shimashō) and the copula (-desu, -deshita, -deshō). Adjectives also have inflections for the same categories:

暑いです atsui desu

it’s hot

暑かったです atsukatta desu

it was hot

暑いでしょう atsui deshō

it will (probably) be hot

The negative of adjectives is a phrase consisting of the plain INFINITIVE + arimasen (or nai desu) ‘does not exist.’

暑くありません atsuku arimasen

it’s not hot

暑くないです atsuku nai desu

it’s not hot

暑くありませんでした atsuku arimasen deshita

it was not hot

暑くなかったです atsuku nakatta desu

it was not hot

暑くないでしょう atsuku nai deshō

it will (probably) not be hot.

This is discussed further in 5.11.

4.2. Plain and polite forms

For the same inflectional category, like imperfect or perfect, a Japanese verb, adjective, or copula may have two forms: a plain form and a polite form. In familiar speech, only the plain forms occur. But in polite speech, the plain forms are limited in occurrence to some place other than at the end of the sentence. So, in the polite style of talking, you will say both of the following sentences:

雨が降りました。

Ame ga furimashita.

It rained.

雨が降ったから,うちにいました。

Ame ga futta kara, uchi ni imashita.

Because it rained, I stayed home.

Occasionally you will hear a polite form used somewhere other than at the end of the sentence. For instance, someone may say:

雨が降りましたから,うちにいました。

Ame ga furimashita kara, uchi ni imashita.

Because it rained, I stayed home.

In fact, before the particle ga meaning ‘but, and,’ the polite form is the usual thing. And before the particle keredomo ‘but, however,’ many people prefer to use the polite form.

The moods that occur at the end of a sentence are limited to the imperfect, perfect, and tentative. But within a sentence, there are a number of other moods, such as the gerund (see 3.9) and the infinitive (see 4.3, 4.5, 4.6, and 4.8). Here are some examples of the use of plain and polite forms within sentences:

寒いと関節が痛みます。

Samui to kansetsu ga itamimasu.

When it’s cold, my joints hurt.

疲れたから, もう寝ます。

Tsukareta kara, mō nemasu.

I’m tired, so I’ll go to bed now.

父は心臓病で亡くなりましたが,母は癌でなくなりました。

Chichi wa shinzōbyō de nakunarimashita ga, haha wa gan de nakunarimashita.

My father died of heart disease, but my mother died of cancer.

英語の教師だったけれども, 英語を話す国に行ったことはありません。

Eigo no kyōshi datta keredomo, Eigo o hanasu kuni ni itta koto wa arimasen.

I was an English teacher, but I have never been to any English-speaking countries.

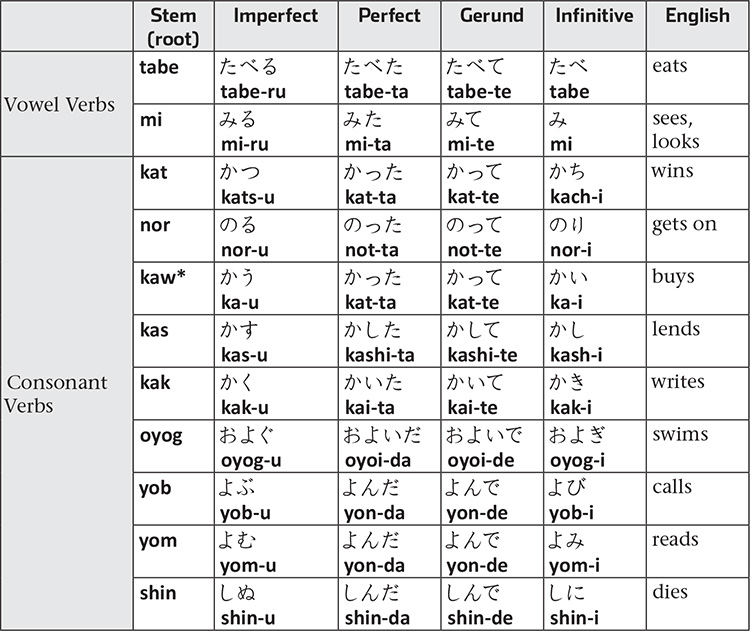

4.3. Shapes of the plain forms

Any Japanese inflected form may be broken up into a “stem” and an “ending.” (Some call stems “roots,” referring to the form without any endings.) Japanese verbs fall into two main classes: consonant verbs and vowel verbs. The consonant verbs are those with a stem that ends in a consonant; the vowel verbs are those with a stem that ends in a vowel. Vowel stems end only in -e or -i:

(1) -i as in 見る mi-ru

sees

(2) -e as in 食べる tabe-ru

eats

Consonant stems end in one of the following nine sounds (verbs are usually mentioned by the plain imperfect form: kau ‘buys’):

(1) -t[s] as in 勝つ kats-u

wins

(2) -r as in 乗る nor-u

rides

(3) -[w] as in 買う ka-u

buys

(4) -s as in 貸す kas-u

lends

(5) -k as in 書く kak-u

writes

(6) -g as in 泳ぐ oyog-u

swims

(7) -b as in 呼ぶ yob-u

calls

(8) -m as in 読む yom-u

reads

(9) -n as in 死ぬ shin-u

dies

You will notice certain peculiarities in the above list of stem-final consonants. Verbs like kau ‘buys’ are said to be consonant verbs, but the consonant with which they end, w, just doesn’t occur in Japanese except before the sound a (as in watashi ‘I’). This means that for some of the endings, like the imperfect, these w-ending-stem verbs don’t display this stem-final consonant at all. That is why we put the w in brackets—to show that it disappears before every vowel except a. You will notice another sound in brackets—the s of the verb katsu ‘wins.’ This verb stem basically ends in just -t, but the sound t does not occur before the sound u in Japanese, so that before an ending beginning with u, the t is replaced by ts. In a similar way, since the combination ti does not normally occur in Japanese, before the infinitive ending -i, the t becomes ch— kach-i ‘wins.’ Since the sound si does not occur, the infinitive of hanas-u ‘speaks’ turns out to be hanash-i ‘speaking.’ There is only one verb with a stem ending in -n, shinu ‘dies,’ and this is often replaced by a euphemism nakunaru ‘passes away.’ The verb shinu is included in our list only for completeness. Here are some models showing the formation of the plain forms:

* The w at the end of a consonant verb is pronounced and heard only if it is followed by the vowel a.

The endings, then, are as follows:

Imperfect:

-ru after a vowel stem, -u after a consonant stem

Infinitive:

(-ZERO) after a vowel stem, -i after a consonant stem

Perfect:

-da after -g, -b, -m, and -n stems; -ta after all other stems

Gerund:

-de after -g, -b, -m, and -n stems; -te after all other stems

The ZERO ending is an ending that has no shape at all. Notice that multiple verbs might have exactly the same form, for example, the gerund forms of katsu ‘wins’ and kau ‘buys’ in the above table are both katte. Often the pitch accents are different in such cases, but you can always distinguish them by the context in which each is used.

4.4. Learning the forms

Now, how should one go about learning these inflectional forms? You have read a description of how they are put together, and that may be of some help to you. But in order to be able to make up the forms for a new verb you hear, you will want to compare it with a verb you already know and make its forms by analogy, using the old verb for a model. You can take the verbs used in the lists here for your models. Learn their forms well, and then make forms for other verbs on their patterns.

When you come across a new verb, the first thing you want to know is: is it a consonant verb or a vowel verb? Unless the verb ends in -eru or -iru in the imperfect, there is no doubt about it, but if the verb does end in -eru or -iru, you don’t know whether it is a consonant verb or a vowel verb until you check one of the other forms, such as the infinitive or the perfect.

In this book we will show two imperfect forms, plain and polite, in the Basic Vocabulary section, so that you can clearly tell whether any of the -eru and -iru verbs are consonant verbs or vowel verbs: if you get the same form after removing -ru and -masu, the verb is a vowel verb. For example, take taberu and tabemasu ‘eats,’ and remove -ru and -masu from taberu and tabemasu, respectively. You get exactly the same form, which is tabe. This means that taberu is a vowel verb. Do the same for kaeru and kaerimasu ‘returns.’ After removing -ru and -masu, you get kae and kaeri, which are different. This means that kaeru ‘returns’ is a consonant verb. No need to be alert all the time. You just need to be alert if you see a verb that ends in -eru or -iru. The following are pairs of consonant verbs and vowel verbs whose plain imperfect forms are exactly the same.

Vowel Verb |

Consonant Verb |

iru/imasu stays, exists (いる) |

iru/irimasu is necessary (要る) |

kiru/kimasu wears on body (着る) |

kiru/kirimasu cuts (切る) |

neru/nemasu sleeps (寝る) |

neru/nerimasu kneads (練る) |

kaeru/kaemasu changes (変える) |

kaeru/kaerimasu returns (帰る) |

Most verbs with the imperfect ending in -eru or -iru are vowel verbs, so it is a good idea to memorize a small list of -eru/-iru ending “consonant” verbs. The following list is not exhaustive, but is helpful.

散る/散ります chiru/chirimasu

falls, scatters

入る/入ります hairu/hairimasu

enters

走る/走ります hashiru/hashirimasu

runs

減る/減ります heru/herimasu

decreases

要る/要ります iru/irimasu

is necessary

煎る/煎ります iru/irimasu

roasts

帰る/帰ります kaeru/kaerimasu

returns

限る/限ります kagiru/kagirimasu

limits

蹴る/蹴ります keru/kerimasu

kicks

切る/切ります kiru/kirimasu

cuts

参る/参ります mairu/mairimasu

goes

混じる/混じります majiru/majirimasu

mixes

ねじる/ねじります nejiru/nejirimasu

twists

練る/練ります neru/nerimasu

kneads

握る/握ります nigiru/nigirimasu

grasps, takes hold

茂る/茂ります shigeru/shigerimasu

grows thick

仕切る/仕切ります shikiru/shikirimasu

divides

知る/知ります shiru/shirimasu

knows

しゃべる/しゃべります shaberu/shaberimasu

chats

滑る/滑ります suberu/suberimasu

slides

照る/照ります teru/terimasu

shines

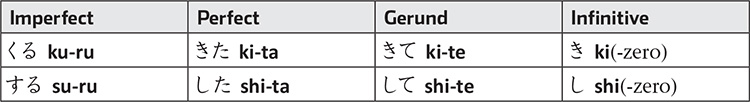

4.5. Irregular verbs

There are only a few common verbs that have considerable irregularities of inflection. The verbs kuru (kimasu) ‘comes’ and suru (shimasu) ‘does’ are irregular in the plain imperfect itself. (We would expect something like *ki-ru and *shi-ru if the verbs were regular.) Nearly everywhere else these verbs behave the way you would expect a vowel verb ending in -iru to behave:

The verb ik-u ‘goes’ is irregular only in the way the stem changes the -k to -t instead of -i before the t-endings. (We might have expected a form like *i-ita instead of the actual it-ta, if the verb were regular.) There is one other verb that is irregular in the imperfect only. This is the verb i(w)-u ‘says, tells.’ We write this form iu, but it is often pronounced yū.

Note that the perfect and gerund forms of iu ‘says,’ iku ‘goes’ and ir-u ‘is necessary’ are the same: itta, itte. You can tell them apart only by the rest of the sentence. (But some people pronounce yutta and yutte for ‘said’ and ‘saying.’) There are some verbs whose masu-forms lacks r. For example, the polite imperfect form of kudasaru is not kudasarimasu but kudasaimasu. Similarly, the polite imperfect form of irassharu ‘to exist’ is not irassharimasu but irasshaimasu.

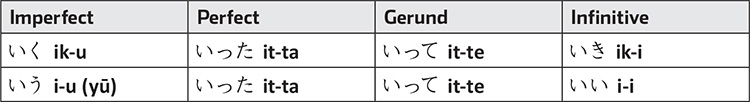

4.6. Adjectives and the copula

Adjectives in Japanese end in:

-ai like akai

is red

-oi like aoi

is blue

-ui like warui

is bad

-ii like ōkii

is big

They are inflected simply by adding certain endings to the vowel before the -i, which is the imperfect ending itself:

Imperfect |

Perfect |

Gerund |

Infinitive |

い -i |

かった -katta |

くて -kute |

く -ku |

The copula is somewhat irregularly inflected, so the forms are best learned as separate words rather than being broken into stem and ending. The adjective ii ‘is good’ has an alternate form yoi ‘is good.’ The other forms are all based only on the form yoi.

Here are some examples of inflected forms of adjectives and the copula used in sentences:

山田さんは優しいし, 頭がいいし, 悪いところがないし, きれいだし。

Yamada-san wa yasashii shi, atama ga ii shi, warui tokoro ga nai shi, kirei da shi.

Ms. Yamada is kind, smart, no bad qualities, pretty…

10年前はまだ家も安かったし,手続きも簡単だった。

Jū-nen mae wa mada ie mo yasukatta shi, tetsuzuki mo kantan datta.

Ten years ago, houses were still cheap and (purchase) procedures were simpler.

昨日は雨が降って寒くて,最悪の天気で本当に困った。

Kinō wa ame ga futte samukute, saiaku no tenki de hontō ni komatta.

Yesterday, it rained, it was cold, and it was the worst weather, and we were in real trouble.

急に涼しくなって,海岸も人がいなくなって,静かになってしまいましたね。

Kyū ni suzushiku natte, kaigan mo hito ga inaku natte, shizukani natte shimaimashita ne.

It became cooler all of a sudden, people disappeared from the beaches, and it became completely quiet.

今日は天気がよくて,風もなくて,洗濯物を干すには最高の日でよかった。

Kyō wa tenki ga yokute, kaze mo nakute, sentakumono o hosu ni wa saikō no hi de yokatta.

Today, the sky was clear, no strong wind, and so it was an ideal day for hanging out the wash.

4.7. Uses of the plain imperfect and perfect

Both imperfect and perfect are used before the particle kara with the meaning ‘because’:

そこにあるから soko ni aru kara

because it’s there

そこにあったから soko ni atta kara

because it was there

Notice the difference in meaning between GERUND + kara and PERFECT + kara:

友達が来てから,いっしょにご飯を食べました。

Tomodachi ga kite kara, issho ni go-han o tabemashita.

After my friend came, we had dinner together.

友達が来たから,いっしょにご飯を食べました。

Tomodachi ga kita kara, issho ni go-han o tabemashita.

Because my friend came, I had dinner with him.

Before keredomo ‘however, but,’ both imperfect and perfect occur:

私は学校へ行ったけれども勉強しませんでした。

Watashi wa gakkō e itta keredomo benkyō shimasen deshita.

I went to school, but I didn’t study.

私は学校へ行くけれどもあまり勉強しません。

Watashi wa gakkō e iku keredomo amari benkyō shimasen.

I go to school, but I don’t study very much.

Before the particle to meaning ‘when,’ only the imperfect occurs:

春になると,お天気がよくなります。

Haru ni naru to, otenki ga yōku narimasu.

When it gets to be spring, the weather gets nice.

子どもは先生を見ると,すぐ部屋の中へ入りました。

Kodomo wa sensei o miru to, sugu heya no naka e hairimashita.

As soon as they spotted the teacher, the children went into the room.

雪が降ると, うちにいて遊びます。

Yuki ga furu to, uchi ni ite asobimasu.

When it snows, we stay home and enjoy ourselves (here).

Before the phrases koto ga suki desu ‘likes to,’ koto ga dekimasu ‘can,’ and tsumori desu ‘intends to,’ only the imperfect occurs:

泳ぐことが好きです。

Oyogu koto ga suki desu.

I like to swim.

泳ぐことが好きでした。

Oyogu koto ga suki deshita.

I used to like to swim.

泳ぐことが好きでしょう。

Oyogu koto ga suki deshō.

You must like to swim.

山へ行くつもりです。

Yama e iku tsumori desu.

I intend to go to the mountains.

山へ行くつもりでした。

Yama e iku tsumori deshita.

I intended to go to the mountains.

山へ行くつもりでしょう。

Yama e iku tsumori deshō.

You must be planning to go to the mountains.

Before the phrase koto ga aru ‘there exists the fact of,’ either imperfect or perfect is used, depending on the meaning. If you use the imperfect, the meaning is ‘sometimes’:

公園へ行って散歩することがあります。

Kōen e itte sanpo suru koto ga arimasu.

I sometimes go to the park and take a walk.

秋にも寒いことがあります。

Aki ni mo samui koto ga arimasu.

It is sometimes cold in autumn, too.

If you use the perfect before koto ga aru, the meaning is ‘has ever done, once did’:

日比谷公園へ散歩に行ったことがありますか。

Hibiya-kōen e sanpo ni itta koto ga arimasu ka.

Have you ever been (gone) to Hibiya Park for a walk?

そこへ行ったことはありません。

Soko e itta koto wa arimasen.

I’ve never been there.

神戸へ旅行したことがあります。

Kōbe e ryokō shita koto ga arimasu.

I once took a trip to Kobe.

もうそこへ行ったことがありましたが,前の旅行は冬でした。

Mō soko e itta koto ga arimashita ga, mae no ryokō wa fuyu deshita.

I had already been there (once), but the trip before was (in) winter.

4.8. Uses of the infinitive

The infinitive is a noun-like form of verbs and adjectives. There is no copula infinitive, except in the impersonal style (de ari), where the copula is always a phrase.

Verb and adjective infinitives are used before various particles just as nouns are.

鞄を取りに行きました。

Kaban o tori ni ikimashita.

I went to pick up the suitcase.

遅くまで勉強しました。

Osoku made benkyō shimashita.

I studied till late.

For emphatic contrast, a verb infinitive is sometimes followed by the particle wa and some form of the verb suru:

泳ぎはしませんでしたが,遊びはよくしました。

Oyogi wa shimasen deshita ga, asobi wa yoku shimashita.

I DIDN’T do any swimming, but I DID do a lot of playing.

Similarly, an adjective infinitive is followed by wa and a form of the verb aru:

小さくはありましたけれども,悪くはありませんでした。

Chīsaku wa arimashita keredomo, waruku wa arimasen deshita.

It WAS small, but it WASN’T bad.

The adjective infinitive often modifies other verb and adjective forms without any particle—this is similar to the ADVERB use of nouns without particles:

寒くなりました。

Samuku narimashita.

It got cold.

早く歩いてください。

Hayaku aruite kudasai.

Please walk fast.

髪を短くしました。

Kami o mijikaku shimashita.

I made my hair short.

The infinitive yoku (-ii ‘is good’) has three slightly different meanings: ‘well; often; a lot’:

よくなりました。

Yoku narimashita.

He got well.

雨がよく降ります。

Ame ga yoku furimasu.

It rains a lot.

ここは台風がよく来ます。

Koko wa taifū ga yoku kimasu.

Typhoons often come here.

The meanings ‘often’ and ‘a lot’ are similar to English ‘a good deal’ as in ‘it rains a good deal’ and ‘she goes to the movies a good deal.’

The verb infinitive is easy to find: just remove the -masu from the polite forms such as tabe-masu, nomi-masu, shi-masu, etc. The verb infinitive is used to make compound verbs. For example, you can add the verb tsuzukeru ‘continues something’ to any verb infinitive to make a compound verb with the meaning ‘continues to do something’:

話しつづける hanashi-tsuzukeru

continues talking

飲みつづける nomi-tsuzukeru

goes on drinking

見つづける mi-tsuzukeru

keeps on looking

Another kind of compound verb is made with the verb naosu ‘repairs, fixes, cures’ added to the infinitive; this means ‘does something again (correcting one’s error)’:

書きなおす kaki-naosu

writes again, corrects

読みなおす yomi-naosu

reads again (correctly this time)

Somewhat similar are compound verbs made by attaching kaeru ‘changes something’ (do not confuse kae-ru with kaer-u ‘returns’) to an infinitive:

乗りかえる nori-kaeru

changes trains (‘ride-changes’)

言いかえる ii-kaeru

rephrase

Still another kind of compound verb is made by adding either hajimeru ‘begins something’ or dasu ‘puts something out; starts something’ to an infinitive:

読みはじめる yomi-hajimeru

begins to read

走りだす hashiri-dasu

starts to run

A special type of compound is made by adding sugiru ‘is in excess’ to a verb infinitive (or to just the stem of an adjective, or to a copular noun):

食べすぎる tabe-sugiru

eats too much

働きすぎる hataraki-sugiru

overworks

遅すぎる oso-sugiru

is too late

大きすぎる ōki-sugiru

is overly large

静かすぎる shizuka-sugiru

is too quiet

The following sentences have compound verbs:

三日前から雨が降りだして, 今もまだ降りつづけています。

Mikka mae kara ame ga furi-dashite, ima mo mada furi-tsuzukete imasu.

It started to rain three days ago, and it is still raining now.

誠は言いだしたら全然人の話を聞かない。

Makoto wa ii-dashitara zenzen hito no hanashi o kikanai.

Makoto does not listen to anyone once he starts saying something.

食べすぎないようにしなくてはいけません。

Tabe-suginai yō ni shinakute wa ikemasen.

You must try not to overeat.

品川で乗りかえてください。

Shinagawa de nori-kaete kudasai.

Please change trains at Shinagawa.

考えなおして, 働きはじめました。

Kangae-naoshite, hataraki-hajimemashita.

I reconsidered, and started working.

マンガを読みすぎました。

Manga o yomi-sugimashita.

I read comic books too much.

Finally, the verb infinitive is the source of many derived nouns:

休み yasumi ‘vacation’ from yasumu (rests)

はなし hanashi ‘story’ from hanasu (speaks)

はじめ hajime ‘beginning’ from hajimeru (begins)

泳ぎ oyogi ‘swimming’ from oyogu (swims)

通り tōri ‘street’ from tōru (passes)

There are a few nouns derived from adjective infinitives like chikaku ‘vicinity’ from chikaku ‘being near,’ as in Ginkō wa chikaku ni arimasen ‘There is no bank in the vicinity.’

A special kind of noun is derived by adding the noun kata ‘manner’ to the infinitive. The meaning of these nouns is ‘way or manner of (do)ing’:

食べ方 tabekata

way of eating

話し方 hanashikata

way of talking

歩き方 arukikata

way of walking

読み方 yomikata

way of reading

書き方 kakikata

way of writing

仕方 shikata

way of doing, means

Here are some example sentences:

犬のような食べ方をしないで,箸かフォークで食べなさい。

Inu no yō na tabekata o shinaide, hashi ka fōku de tabenasai.

Don’t eat like a dog, but eat with chopsticks or a fork.

この漢字の読み方と書き方を教えてください。

Kono kanji no yomikata to kakikata o oshiete kudasai.

Please teach me how to read and write this kanji.

「もう間に合わないね。」

“Mō maniawanai ne.”

“We cannot make it anymore. (It’s too late.)”

「仕方ないよ。」

“Shikata nai yo.”

“There’s nothing we can do (so let’s give up).”

4.9. The plain negative

The plain form of the verb arimasu ‘exists’ is aru. The negative form of this is not a verb at all, but the adjective nai, ‘is non-existent (= does not exist).’ The adjective nai, then, is the plain adjective form corresponding to the polite verb form arimasen. The plain negative of other verbs are also adjectives derived from the verb stems by the addition of the suffix -(a)nai—this is discussed in 5.11. Here are some examples of the adjective nai:

車がないから電車に乗って行きます。

Kuruma ga nai kara densha ni notte ikimasu.

I don’t have a car, so I go by train.

傘がなかったから濡れてしまいました。

Kasa ga nakatta kara nurete shimaimashita.

As I did not have an umbrella, I got wet.

ここに置いておいたのに財布がなくなりました。

Koko ni oite oita no ni saifu ga nakunarimashita.

I placed it here, but my wallet disappeared (became nonexistent).

うっかりしていて財布をなくしました。

Ukkari shite ite saifu o nakushimashita.

I was absent-minded and lost my wallet (made it nonexistent).

Note that nakusuru is also treated as nakus-u, a consonant verb.

4.10. Particle も mo

The particle mo means ‘even’ or ‘also.’ After numbers it is sometimes equivalent to ‘as little as’ or ‘as much as.’ When there are two phrases in a row, each ending in mo, the translation is ‘both… and…’ if the predicate is affirmative and ‘(n)either…(n)or…’ if the predicate is negative.

今日も雨ですね。

Kyō mo ame desu ne.

Today is also a rainy day. (It is raining again today.)

簡単な漢字も書けなくなってしまいました。

Kantan na kanji mo kakenaku natte shimaimashita.

I became unable to write even easy kanji characters.

お酒は一杯も飲めません。

O-sake wa ip-pai mo nomemasen.

I cannot drink even a glass of sake.

靴を5足も買ったんですか。

Kutsu o go-soku mo katta n desu ka.

You bought as many as five pairs of shoes?

ビールもワインも好きです。

Bīru mo wain mo suki desu.

I like both beer and wine.

ビールもワインもウイスキーも好きです。

Bīru mo wain mo uisukī mo suki desu.

I like beer, wine, and whiskey.

ビールもワインも好きじゃありません。

Bīru mo wain mo suki ja arimasen.

I don’t like either beer or wine.

4.11. Expressing the time of the event ‘when …’ (…と …to, …時 …toki, …間 …aida)

The particle to occurs after the plain imperfect with the meaning ‘when, whenever, if.’ Another way to say ‘when,’ with reference to some specific time, is to use either the imperfect (with present meaning) or the perfect (with past meaning) and follow this with the noun toki ‘time.’ If you mean ‘during the interval of …,’ you can use the word aida ‘interval’ preceded by either the imperfect or the perfect (depending on the meaning) in the progressive form. Aida or toki can be followed by wa, ni, or ni wa.

窓の外を見ると雪が降っていた。

Mado no soto o miru to yuki ga futte ita.

When I looked outside through the window, it was snowing.

春になると花が咲く。

Haru ni naru to hana ga saku.

When it is spring, flowers blossom.

忙しいとあまり食べませんが, 暇だとつい食べ過ぎてしまいます。

Isogashii to amari tabemasen ga, hima da to tsui tabe-sugite shimaimasu.

If I’m busy, I don’t eat much, but if I’m doing nothing, I tend to overeat before I know it.

道をわたる時には右と左をよく見てください。

Michi o wataru toki ni wa migi to hidari o yoku mite kudasai.

When crossing a street, look to your right and left carefully.

電車の中で変な荷物を見た時はすぐに車掌に言ってください。

Densha no naka de hen na nimotsu o mita toki wa sugu ni shashō ni itte kudasai.

When you see a strange package in a train, please let the conductor know as soon as possible.

小さい時から泳ぎは得意でした。

Chīsai toki kara oyogi wa tokui deshita.

I’ve been good at swimming since I was little.

洗濯をしている間に掃除もします。

Sentaku o shite iru aida ni sōji mo shimasu.

While doing laundry, I also clean.

冬の間は何もしません。

Fuyu no aida wa nani mo shimasen.

I don’t do anything during the winter.

4.12. Particle から kara meaning ‘since’ and ‘because’

The particle kara after a noun usually means ‘from’ in a physical sense: Kōbe kara ‘from Kobe.’ From this it is extended to mean ‘from’ or ‘after’ or ‘since’ in a temporal sense: kinō kara ‘from yesterday, since yesterday,’ sore kara ‘from that, after that,’ Nihon e kita toki kara ‘from the time I came to Japan, since I came to Japan.’ After a GERUND also, it has the meaning of ‘after’:

ご飯を食べてから,テレビを見ました。

Go-han o tabete kara, terebi o mimashita.

After eating, we watched TV.

However, after the plain imperfect or perfect, this particle means ‘since’ in the causal sense of ‘because’:

雨が降ったから,行けませんでした。

Ame ga futta kara, ikemasen deshita.

Because it rained, I could not go there.

You will find it convenient to translate this kara as ‘so,’ since the word so fits into English syntax at about the same point that kara fits into Japanese syntax. The main difference is that we often pause BEFORE so, but the Japanese pause AFTER kara. The above Japanese sentence is repeated here with an English translation with so:

雨が降ったから,行けませんでした。

Ame ga futta kara, ikemasen deshita.

It rained, so I could not go there.

In English, we say things like ‘I HAVE BEEN ill since last night. I’ve BEEN in Japan since last year,’ using a present perfect even though we are still ill or in Japan at the time we are talking. In Japanese, the imperfect is used for these situations: Sakuban kara byōki desu. Kyonen kara Nihon ni imasu. Here are some examples of the uses of kara in a variety of contexts, in conjunction with gerund, perfect, and imperfect forms of verbs, adjectives, and the copula:

気温が急激に下がってから池の水が凍ってしまいました。

Kion ga kyūgeki ni sagatte kara ike no mizu ga kōtte shimaimashita.

As soon as the temperature dropped drastically, the pond froze.

お父さんが帰ったからゲームは隠した方がいいよ。

Otōsan ga kaetta kara gēmu wa kakushita hō ga ii yo.

As your dad has gotten home, it is better to hide the game.

今日は寒いから厚いジャケットを着た方がいいですよ。

Kyō wa samui kara atsui jaketto o kita hō ga ii desu yo.

It is cold today, so it is better to wear a thick jacket.

雪が降ったから学校が休校になった。

Yuki ga futta kara gakkō ga kyūkō ni natta.

As it snowed, the school was closed.

梅雨だから、雨がよく降る。

Tsuyu da kara, ame ga yoku furu.

Because it is rainy season, it rains a lot.

4.13. Multiple particles

Sometimes a word is followed by more than one particle. In such cases, the meaning of the last particle restricts the meaning of the entire phrase leading up to it. For example, in the phrase Nihon de wa, the particle wa sets off Nihon de ‘in Japan’ as the topic. In koko ni mo arimasu ‘there’s some here too,’ the particle mo gives a special ‘also’ meaning to the phrase koko ni ‘in this place.’ In Tokyō kara no densha ‘the train from Tokyo,’ the particle no makes the entire phrase modify densha (what kind of a densha? the sort about which you can say Tōkyō kara).

Particles that occur after other particles are usually only the topic particle wa, the subject particle ga, the object particle o, and the intensive particle mo; these particles have somewhat more general meanings than those of to ‘with,’ ni ‘at, to,’ e ‘to,’ de ‘at,’ made ‘till,’ kara ‘from,’ etc. The particles wa, ga, o, and mo never occur in sequences with each other—their meanings are mutually exclusive.

田中さんとは最近話していません。山田さんともあまり話していません。

Tanaka-san to wa saikin hanashite imasen. Yamada-san to mo amari hanashite imasen.

I haven’t talked with Mr. Tanaka lately. I haven’t talked with Mr. Yamada much, either.

居酒屋にはよく行きます。カラオケボックスにもよく行きます。

Izakaya ni wa yoku ikimasu. Karaoke bokkusu ni mo yoku ikimasu.

We go to an izakaya bar very often. We also often go to a karaoke box, too.

12課からが難しいんです。12課からをよく勉強してください。

Jūni-ka kara ga muzukashii n desu. Jūni-ka kara o yoku benkyō shite kudasai.

Lesson 12 onwards is difficult. Please study Lesson 12 onwards carefully.

4.14. こと koto

The word koto means ‘thing (that you can’t touch or see)’; there is another word mono that usually means ‘thing (that you can touch or see).’ Mono is also a humble word for ‘person’ (= hito); a vulgar synonym (in both meanings) is yatsu. (Kono yatsu, sono yatsu, ano yatsu, and dono yatsu are usually abbreviated to koitsu, soitsu, aitsu, and doitsu, respectively.)

Sometimes the word koto means ‘act’ or ‘fact.’ In this lesson there are two special expressions with koto: (iku) koto ga arimasu ‘there exists the fact of (my going) = (I) sometimes (go)’ and (itta) koto ga arimasu ‘there exists the fact of my having (gone) = I have (gone), I once (went).’ Note that the difference in meaning between these two expressions is carried by the mood of the verb in front of koto: the perfect (itta) is used with the meaning ‘once did, ever did’ (negative ‘never did’); the imperfect (iku) is used with the meaning ‘sometimes does’ (negative ‘never does’). If you want to put either expression entirely in the perfect, you change the mood of the verb arimasu: iku koto ga arimashita ‘there existed the fact of my going = I sometimes went,’ itta koto ga arimashita ‘there existed the fact of my having gone = I had once gone.’

The relationship between the plain forms of the verb (iku and itta) and the word koto is that of modifier to modified, with the meaning ‘which (does or is).’ That is, a koto WHICH iku or itta, a koto ABOUT WHICH YOU CAN SAY iku or itta. The plain inflected forms in Japanese can modify a noun (like koto) directly, without any particle. Nouns, on the other hand, have to be followed by the particle no (or a modifying form of the copula na or no, see 5.3) to modify another noun. The modifier relationship is further discussed in 5.1. More examples of expressions with koto:

「その本を読んだことがありますか。」

“Sono hon o yonda koto ga arimasu ka.

“Have you (ever) read that book?”

「いいえ, ありません。」

“Īe, arimasen.”

“No, I haven’t.”

シカゴには行ったことがありません。去年まではニューヨークにも行ったことがありませんでした。

Shikago ni wa itta koto ga arimasen. Kyonen made wa Nyū Yōku ni mo itta koto ga arimasen deshita.

I haven’t been to Chicago yet. Until last year I had never even been to New York.

「あの人の声が嫌だと思うことはありませんか。」

“Ano hito no koe ga iya da to omou koto wa arimasen ka.”

“Don’t you sometimes (ever) dislike his voice?”

「時々ありますね。」

“Tokidoki arimasu ne.”

“I sometimes do.”

ここでは冬はあまり寒くありませんが, 雪が降ることもあります。

Koko de wa fuyu wa amari samuku arimasen ga, yuki ga furu koto mo arimasu.

The winter is mild here, but it occasionally snows.

アメリカでは日本のテレビを見ることはありません。

Amerika de wa Nihon no terebi o miru koto wa arimasen.

In America we never have the chance to watch Japanese TV programs.

Another use of the noun koto is in the phrases koto ga suki desu ‘likes to’ and koto ga kirai desu ‘dislikes to.’ The basic meaning of these phrases, preceded always by a plain imperfect form, is ‘the fact (of doing something) is liked’ and ‘the fact (of doing something) is disliked.’ Here are some additional examples of these phrases:

人の悪口を言うことが好きなんですか。

Hito no warukuchi o iu koto ga suki na n desu ka.

Do you like to speak ill of others behind their back?

人の名前を覚えることが苦手です。

Hito no namae o oboeru koto ga nigate desu.

I’m not good at remembering people’s names.

A further use of koto is in the phrase koto ga dekimasu ‘can (do something), is able to.’ The basic meaning of this expression is something like ‘the fact (of doing something) is produced,’ but it is the usual way to say ‘can.’ If the verb is suru, the whole phrase is often abbreviated to dekiru: benkyō (suru koto ga) dekiru ‘can study,’ yasuku (suru koto ga) dekiru ‘can make it cheaper.’ This is not the expression used to translate the English ‘can’ that is used for ‘may’ in the sense of permission, as in ‘Father says I can go.’ That expression is translated by a special phrase discussed in note 8.6. Instead of PLAIN IMPERFECT + koto ga dekimasu, sometimes you will hear a noun derived from the infinitive + ga dekimasu; the meaning then is something more specific like ‘knows how to’ rather than the general meaning ‘is able to’ (which includes the specific meaning).

まだ泳ぐことができません。妹もまだ泳ぎができません。

Mada oyogu koto ga dekimasen. Imōto mo mada oyogi ga dekimasen.

I still cannot swim. My little sister still cannot swim either.

まだ車を運転することができません。兄もまだ車の運転ができません。

Mada kuruma o unten suru koto ga dekimasen. Ani mo mada kuruma no unten ga dekimasen.

I still cannot drive a car. My big brother still cannot do so either.

もう少し早く印刷することができませんか。

Mō sukoshi hayaku insatsu suru koto ga dekimasen ka.

Could you print them a bit earlier?

安くできませんか。

Yasuku dekimasen ka.

Can you make it cheaper?

4.15. つもり tsumori

Tsumori is a noun with the meaning ‘intention.’ Preceded by the plain imperfect (like suru ‘does’) and followed by some form of the copula (like desu ‘is’), this noun makes a phrase with the meaning ‘it is (someone’s) intention to (do something) = someone plans to do something.’

明日天気がよければ庭掃除をするつもりです。

Asu tenki ga yokereba niwa-sōji o suru tsumori desu.

If the weather is good, I plan to sweep the yard tomorrow.

いつになったら片付けるつもりですか。

Itsu ni nattara katazukeru tsumori desu ka.

When do you intend to put (them) away?

If you want to change the tense of the expression ‘it WAS somebody’s intention to do something, someone planned to do something,’ you just change the mood of the copula: suru tsumori deshita.

昨日は勉強するつもりでしたけれども, 天気がよかったので友達と公園に行きました。

Kinō wa benkyō suru tsumori deshita keredomo, tenki ga yokatta node tomodachi to kōen ni ikimashita.

I had intended to study yesterday, but the weather was nice, so I went to the park with my friends.

However, sometimes you will hear shita tsumori desu ‘it is my intention to have (done)’ ‘I have tried to’:

きれいに書いたつもりです。

Kirei ni kaita tsumori desu.

I have tried to write neatly.

4.16. More adverbs

You have seen some nouns used without particles to modify predicates or whole sentences in 3.2. Here are some more adverbs you will want to know, some of which cannot function as nouns:

少し sukoshi

a little, some, a bit

ちょっと chotto

a little, some, a bit

毎晩 maiban

every evening

毎朝 maiasa

every morning

最近 saikin

lately

たくさん takusan

lots

大変 taihen

very (lit., awfully, terribly)

たいてい taitei

usually

普通 futsū

usually

時々 tokidoki

sometimes

度々 tabitabi

often

だんだん dandan

gradually

なかなか nakanaka

quite, rather, completely, at all

ずいぶん zuibun

very (much)

とても totemo

completely, quite

相当 sōtō

rather, considerably

大分 daibu

mostly, for the most part

結構 kekkō

quite

父は朝はたいていごはんを食べますが, 時々パンを食べます。

Chichi wa asa wa taitei go-han o tabemasu ga, tokidoki pan o tabemasu.

My father usually eats rice in the morning, but he sometimes eats bread.

大変お世話になりました。

Taihen o-sewa ni narimashita.

You have helped me a lot.

漢字がなかなか書けませんでしたが, 最近書けるようになりました。

Kanji ga nakanaka kakemasen deshita ga, saikin kakeru yō ni narimashita.

I could not write kanji very easily, but I recently learned to write it.

ずいぶん上手に話せるようになりましたね。単語も相当知っているようだし。

Zuibun jōzu ni hanaseru yō ni narimashita ne. Tango mo sōtō shitte iru yō da shi.

You have learned to speak quite well, haven’t you? You seem to know a lot of vocabulary.

度々申し訳ありませんが,ちょっと質問がありまして。

Tabitabi mōshiwake arimasen ga, chotto shitsumon ga arimashite.

I’m sorry to keep bothering you, but I have some questions.

普通はとても優しくていい人なのですが, 怒ると結構わがままなことを言います。

Futsū wa totemo yasashikute ii hito na no desu ga, okoru to kekkō wagamama na koto o iimasu.

Normally, he is a kind and nice person, but once he gets angry, he says quite selfish things.

4.17. More gerund expressions

The verbs motsu ‘holds, has, owns’ and toru ‘picks up, takes’ are used in several expressions meaning ‘brings, takes, carries (things)’: motte iku ‘holds and goes = takes’; totte iku ‘picks up and goes, carries (off)’; motte kuru ‘holds and comes = brings’; totte kuru ‘picks up and comes, carries (over).’ Remember, to take or bring PEOPLE requires the verb tsureru, as in hito o tsurete kuru ‘brings someone (else),’ and it is generally used only when the person being brought is socially inferior to the one bringing. Here are some more examples:

今日は雨がふりそうだから傘を持っていった方がいいよ。

Kyō wa ame ga furi sō da kara kasa o motte itta hō ga ii yo.

It looks like rain today, so it’s better to bring an umbrella.

隣の息子は夜中に友達をたくさんうちに連れて来て大騒ぎをする。

Tonari no musuko wa yonaka ni tomodachi o takusan uchi ni tsurete kite ōsawagi o suru.

My next-door neighbor’s son brings many of his friends home at night and they make a lot of noise.

あ, お箸をわすれた。ちょっと持って来て。

A, ohashi o wasureta. Chotto motte kite.

Oh, I forgot chopsticks. Could you bring them?

In English, when someone goes on an errand and returns, we mention his GOING and DOING THE ERRAND; we usually skip saying he came back: ‘He went and got his laundry.’ ‘He went and met Taro (and came back).’ ‘I’m going to go fix the car.’ ‘Let’s go buy that book.’ The Japanese usually skip the part about going, and mention DOING THE ERRAND and COMING back:

あの部屋が空いているか見て来ましょうか。

Ano heya ga aite iru ka mite kimashō ka.

Shall I go and see whether that room is unused?

悪いけど牛乳買って来てくれない?

Warui kedo gyūnyū katte kite kurenai?

Could you go and buy some milk?

4.18. Gerund (te-form) + いる iru

In Lesson 2, we found that the verb iru (imasu) means ‘stays, (a living being) exists (in a place)’:

私は日本にいます。 Watashi wa Nihon ni imasu. I am in Japan.

In Lesson 3, we found that a gerund (te-form) plus the verb iru means ‘(somebody or something) is doing something’:

「今お母さんは何をしているの。」

“Ima okāsan wa nani o shite iru no?”

“What is your mother doing now?”

「隣のおばさんとしゃべっているよ。」

“Tonari no obasan to shabette iru yo.”

“She is chatting with the woman next-door.”

With intransitive verbs—those that do not ordinarily take a direct object, like ‘goes, comes, gets tired, gets cloudy, clears up, becomes,’ there is another meaning for GERUND + iru. With intransitive verbs denoting a single, specific act, like ‘gets to be something, becomes, goes, comes, changes (into),’ the most usual meaning of this construction is the present RESULT of an action that has ALREADY taken place. So tsukarete imasu usually doesn’t mean ‘is getting tired,’ but more often it means just ‘is tired’ (is in a state resulting from having become tired). The idea is that you got tired and then exist.

今疲れていますから後にしてください。

Ima tsukarete imasu kara ato ni shite kudasai.

I’m tired now, so could we do it later?

兄はもう結婚しています。

Ani wa mō kekkon shite imasu.

My big brother is already married.

子どもはもう寝ています。

Kodomo wa mō nete imasu.

The children are already asleep.

父は出張で今仙台に行っています。

Chichi wa shutchō de ima Sendai ni itte imasu.

My father has gone to Sendai for a business trip.

林さんは大阪に住んでいます。

Hayashi-san wa Ōsaka ni sunde imasu.

Mr. Hayashi lives in Osaka.

マイクさんはまだ来ていませんよ。

Maiku-san wa mada kite imasen yo.

Mike has not come yet.

Remember that with the construction GERUND + iru, the subject can be either a living being or an inanimate object. With iru all by itself, the subject is ordinarily limited to a living being. Here are more examples.

ご飯はもうできています。

Go-han wa mō dekite imasu.

The meal is already ready.

空が晴れていますね。

Sora ga harete imasu ne.

The sky is clear, isn’t it?

今日は曇っていますね。

Kyō wa kumotte imasu ne.

It’s cloudy today.

霧がかかっています。

Kiri ga kakatte imasu.

It’s foggy.

雷がなっています。

Kaminari ga natte imasu.

It is thundering.

絵がかかっています。

E ga kakatte imasu.

A picture is hung.

However, with an inanimate object, GERUND + iru is possible only if the verb is an intransitive verb. If it is transitive, the construction GERUND + aru is used instead of GERUND + iru.

絵がかけてあります。

E ga kakete arimasu.

A picture is hung.

4.19. 遊ぶ asobu

The verb asobu means ‘enjoys oneself.’ It is used for English ‘plays, has fun, goes on a pleasure trip, pays a (social) call, visits (for pleasure),’ and other expressions. Here are some examples:

去年北海道に遊びに行きました。

Kyonen Hokkaidō ni asobi ni ikimahsita.

Last year I went to Hokkaidō.

子どもが公園で遊んでいます。

Kodomo ga kōen de asonde imasu.

The children are playing at the park.

今晩遊びに来ませんか。

Konban asobi ni kimasen ka.

Won’t you come to visit (us) this evening?

|

[cue 04-3] |

Conversation

Alison (A) is talking with Makoto (M) at her house.

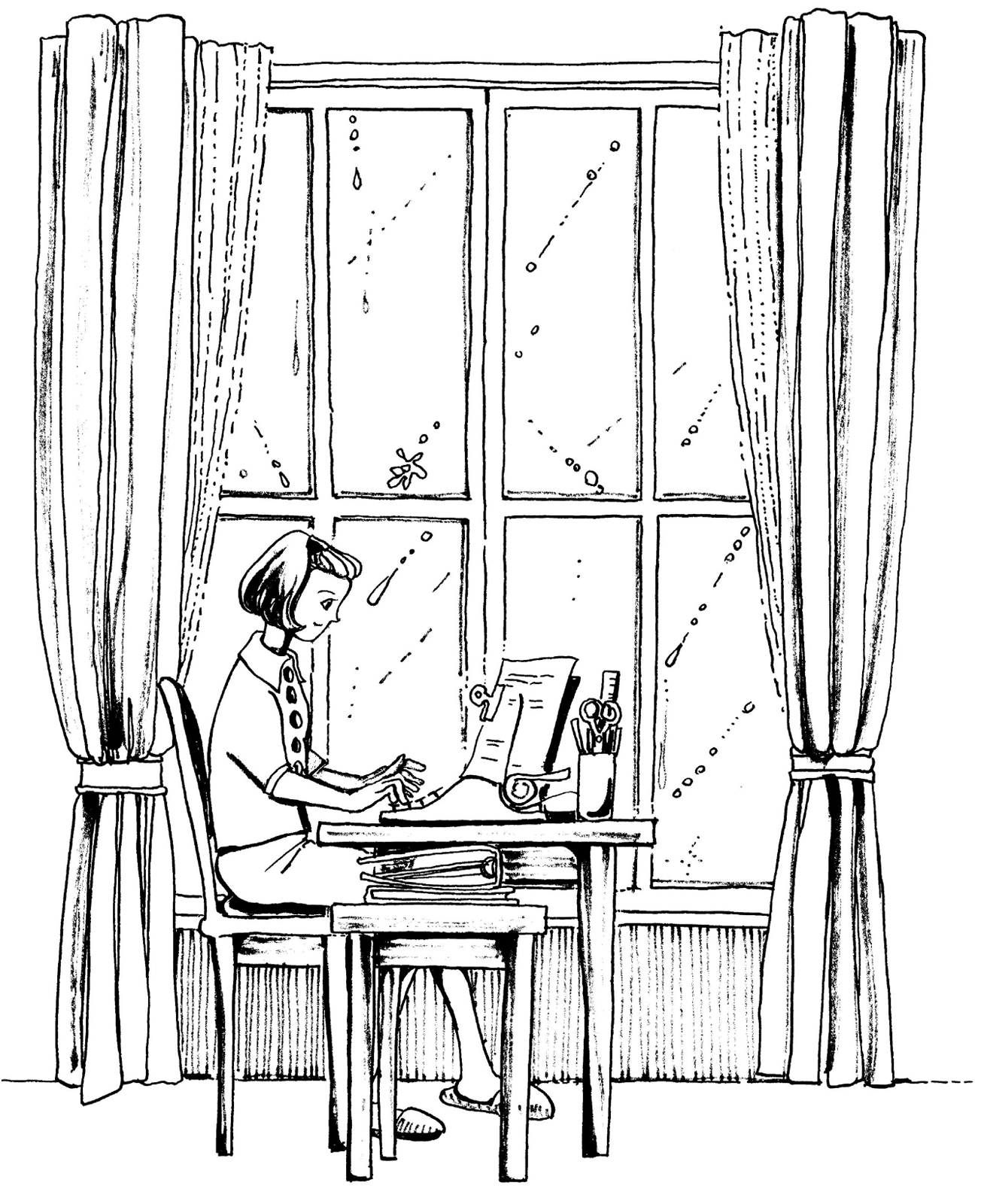

A. ここのところ毎日雨ですね。

Koko no tokoro mainichi ame desu ne.

It has been raining every day lately.

M. ええ。日本では6月は梅雨ですから6月になると雨がよく降るんです。

Ē. Nihon de wa rokugatsu wa tsuyu desu kara rokugatsu ni naru to ame ga yoku furu n desu.

Right. June is a rainy season in Japan, so it rains very often in June.

A. ああ, そうですか。

Ā, sō desu ka.

Oh, really.

M. 毎日雨なんて嫌ですよね。

Mainichi ame nante iya desu yo ne.

It’s so annoying when it rains every day, don’t you think?

A. そうですか。私は雨が好きなんです。

Sō desu ka. Watashi wa ame ga suki na n desu.

Really? I love rain.

M. え?ちょっと変わっていますね。

E? Chotto kawatte imasu ne.

What? You’re weird.

A. 大雨や雷は嫌いですが,しとしと雨が降るのは好きなんです。

Ōame ya kaminari wa kirai desu ga, shitoshito ame ga furu no wa suki na n desu.

I hate heavy rain, thunder, and so on, but I love quiet rain.

M. どうしてですか。

Dō shite desu ka.

Why?

A. 何か心が落ち着いて部屋の中で仕事がよくできるんです。

Nani ka kokoro ga ochitsuite heya no naka de shigoto ga yoku dekiru n desu.

I somehow feel calm and can work in the room better.

M. ああ,確かに。天気がいいと家やオフィスにいるのが嫌になりますからね。

Ā, tashika ni. Tenki ga ii to ie ya ofisu ni iru no ga iya ni narimasu kara ne.

Oh, that’s right. If the weather is good, we don’t feel like staying at home or at the office, that’s why.

Exercises

I. Match the illustrations and phrases:

Example: さむいです

samui desu

1.———— です

———— desu

2.———— です

———— desu

3.———— です

———— desu

II. Fill in the blanks with properly inflected forms of the verbs and adjectives.

1. 何を ———————— いますか。

Nani o ————————— imasu ka.

What are you EATING?

2. 日本の映画を ———————— ことがありますか。

Nihon no eiga o ————————— koto ga arimasu ka.

Have you ever SEEN a Japanese film?

3. そこで ———————— ことがありますか。

Soko de —————————— koto ga arimasu ka.

Have you ever had a SWIM there?

4. 駅で横田さんに ———————— つもりでした。

Eki de Yokota-san ni ————————— tsumori deshita.

I intended to MEET Miss Yokota at the train station.

5. 雪が ———————— からバスが遅れました。

Yuki ga ————————— kara basu ga okuremashita.

Because it SNOWED, the bus was delayed.

6. 地下鉄に ———————— 来ました。

Chikatetsu ni ————————— kimashita.

I came here by (TAKING THE) subway.

7. お酒を ———————— に行ってきます。

O-sake o ————————— ni itte kimasu.

I’ll go to BUY some liquor.

8. あまり早く ———————— と疲れますよ。

Amari hayaku ————————— to tsukaremasu yo.

If you WALK too fast, you get tired.

9. 暇 ———————— と,ついテレビを見てしまいます。

Hima ———————— to, tsui terebi o mite shimaimasu.

When I AM free, I tend to WATCH TV too much.

10. アメリカに ———————— ときも日本語を話しました。

Amerika ni ————————— toki mo Nihongo o hanashimashita.

Even when I LIVED in America, I spoke Japanese.

11. 姉はもう結婚 ———————— います。

Ane wa mō kekkon ————————— imasu.

My sister is married.

12. 松本さんはまだ ———————— いませんか。

Matsumoto-san wa mada ————————— imasen ka.

Hasn’t Mr. Matsumoto COME yet?

III. Explain the difference between the two sentences in each set.

1. a. 父は東京へ行きます。 Chichi wa Tōkyō e ikimasu.

b. 父は東京へ行っています。 Chichi wa Tōkyō e itte imasu.

2. a. 晩ご飯を食べてうちに帰ります。 Ban go-han o tabete uchi ni kaerimasu.

b. 晩ご飯を食べにうちに帰ります。 Ban go-han o tabe ni uchi ni kaerimasu.

3. a. 香港に行くことがあります。 Honkon ni iku koto ga arimasu.

b. 香港に行ったことがあります。 Honkon ni itta koto ga arimasu.

4. a. きれいに書くつもりでした。 Kirei ni kaku tsumori deshita.

b. きれいに書いたつもりです。 Kirei ni kaita tsumori desu.

5. a. カメラを壊しました。 Kamera o kowashimashita.

b. カメラが壊れました。 Kamera ga kowaremashita.