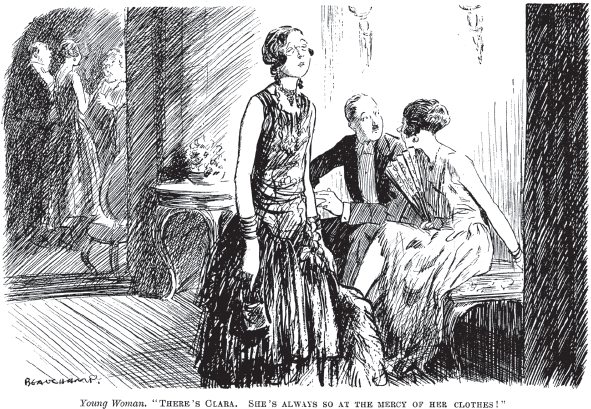

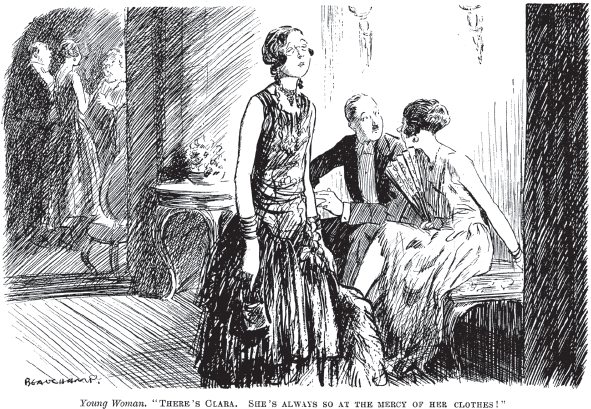

The sketch depicts a young woman in evening dress—shoulders hunched, eyes closed, head tilted in weariness. In the background, another woman confides to her male escort, “There’s Clara. She’s always so at the mercy of her clothes!” (figure 1.1). Clara is fashionably attired, her evening gown, necklace, and other accessories flattering and harmonious; yet both the observer’s comment and Clara’s facial expression suggest that she is “at the mercy” of something. Because Clara’s clothing is her only visible attendant, the evening gown appears to impinge and impose on its wearer, oppressing a young woman who should instead be enjoying the party in the background.

This cartoon, published in Punch, was not alone in representing a woman “at the mercy of” her evening gown. Although many British women undoubtedly found aesthetic pleasure in wearing such attire, early-twentieth-century texts repeatedly represent women’s evening dress as an assemblage in which humans, garments, and accessories work in concert but seldom in harmony. Reading across British mass-market fiction, modernist essays and narratives, and films as well as considering the experiences of historical figures, I demonstrate that the evening gown—a garment that had a long history of use by middle- and upper-class women—resists human agency and solicits harmful connections. Representations of the gown often figure this material creation/object as a participant in events and actions that endangered individual women, rendering them vulnerable to murder, rape, and social stigma as well as to less dramatic (but still traumatic) moments of public awkwardness and shame. The gown, in the texts I analyze in this chapter, emerges as a silent actant that can motivate individual behavior, create opportunities, and make itself available to multiple interpretations. At home, in private, it could be the locus of much joy and aesthetic pleasure; in public, it could suddenly turn on its wearer, rendering her “at the mercy of her clothes.”

A range of associations had accrued to the evening gown by the early twentieth century, associations that help to illuminate why Clara’s creator—cartoonist Kenneth Beauchamp—may have selected this item of clothing for his sketch. As Elizabeth Grosz has argued about things in general, a “thing has a history: it is not simply a passive inertia against which we measure our own activity. It has a ‘life’ of its own, characteristics of its own, which we must incorporate into our activities in order to be effective.”1 In donning an evening gown, a woman like Clara had to adapt its “life” to her own—to put on not only a dress but also a set of practices and expectations that were undergoing radical challenge. In incorporating this material object, women often experienced a transformation beyond that achieved through any “extreme makeover”: they found themselves in situations where the dress, and not its wearer, appeared to exercise helpful or harmful agency.

Popular and feminist modernist representations of women in evening dress explore a paradox: even though evening gowns were characterized by sumptuous materials and beautiful designs, writers of the period consistently choose to depict them in a negative, threatening, and even animate manner. There is variation among the texts, but there is striking unanimity about the gown’s role in producing negative experiences that range from unwilled labor to stabbing. Moreover, some of these texts figure the garment as producing a kind of postsubjective sexuality, in which desire is not grounded in an individual but is mobile and unpredictable. Less inert than involved, the evening gown possesses a nonpurposive (but effective) agency that can queer gender identity and sexual orientation. As my readings will indicate, the evening gown often works in tension with humans; at moments, it even seems to speak and emote.

While a variety of authors share the general sensibility that women are “at the mercy of” evening dress, they part ways when modernists pay greater attention than do popular writers to the emotional appeal of the garment. Virginia Woolf, Rebecca West, and Jean Rhys figure the gown with intense longing;2 in their work, the dress solicits desire and calls into being emotional bonds that keep women in thrall to a conservative and regressive garment. This profound yearning for evening dress betrays these women’s ambivalence about the relationship between embodied forms of aesthetic practice and the gendered coding of sartorial genres. The evening gown thus emerges as a point of contact between different kinds of fiction and a place where attitudes toward conventional dress diverge: animate objects threaten women, but only feminist texts weigh in on why such objects cannot simply be left behind. For Woolf, West, and Rhys, evening dress lingers precisely because it has the potential to offer bodily pleasure and to serve as an aesthetic medium, however resistant.

Such resistance emerges most clearly by examining the evening dress of Ottoline Morrell, the aristocratic salonnière and patron whose fanciful garb was skewered by her contemporaries in letters, diaries, and romans à clef. Extant examples of Morrell’s evening gowns as well as her design credo suggest that she might easily have been regarded as a fashion innovator—as someone not “at the mercy of her clothes”—rather than as the embodiment of bad taste. That Morrell instead became the butt of several writers’ and artists’ humor (a position little challenged by scholars until recently) helps us to understand a specific problem with evening dress in the early twentieth century. At a time when women’s educational, economic, sexual, and political options underwent significant realignment, and when women’s daytime dress evolved to reflect changing activities and roles, nonconformity in women’s evening dress elicited profound and often nasty criticism. Morrell found her evening dresses and accessories extracted and assembled into fictional characters and plots over which she exercised no control.

As creators of texts that were also powerful objects, many early-twentieth-century writers configured the evening gown into a cautionary tale about the tension between material objects (and representations of those objects) and human wearers. In this particular historical window, representations of the evening gown depict women at its mercy; placing it on the bodies of their characters allowed writers to think about the resistance of the object world and to explore the way in which women, too, are objects. Representations of the dress defamiliarize a garment that is active and agentic, and the women who wear it discover that they could buy, but never truly own, the evening gown.

Evening Gowns as Particular Things

Even though a unique set of concerns and questions constellated around women’s evening dress in the early twentieth century, the gown was not a new garment. As Jane Heglund writes, “There is a consensus among dress historians that evening dress materialized as a discrete category in the mid-1820s” when women’s magazines began to identify garments in fashion plates with the label.3 Although such categorization might suggest general agreement about the gown, Heglund notes that “there are surprisingly complex expectations related to appropriateness of fashionable dress for evening,”4 suggesting that codification did not simplify the question of what a woman might wear. As Vanity Fair reported in March 1923, “There are several degrees of formality in evening dress. It is in just as bad taste to wear too elaborate a gown to a public restaurant as it is to wear too informal a frock to the opera.”5 In short, while evening dress as a category had existed for about seventy-five years by the turn of the twentieth century, the phrase pointed not to one kind of dress but to a range of garments suited—or ill suited—to such leisure pastimes as dances, court presentations, and dining. Unlike men’s evening wear, which offered a formalized and limited set of choices, women’s evening dress served as a mobile display of an individual’s taste and social sense, demonstrating the wearer’s comprehension of norms or her inability (or unwillingness) to follow them.

While a range of garments fall under the label “evening dress,” the category collectively serves as a temporal, class, and gender node—a material confederation of time, privilege, and femininity. Twentieth-century evening dress, unlike its nineteenth-century ancestors, appeared in sharp contrast to the garments that women wore during the day. Quentin Bell observed, for example, that in the 1920s and 1930s “one style, that of futile exercise, is used for day wear; another, that of futile repose, serves for the evening.”6 Although Bell’s use of the word “futile” appears to fudge the difference between day and evening wear, this opposition is further refined by dress historian C. Willett Cunnington, who quotes an unidentified fashion journal in support of his argument: “ ‘The great variation between day and evening clothes is the result of the present-day liking for clothes designed for specific occasions.’ For the day costume was, in effect, becoming almost an ‘occupational’ costume, designed primarily for that use and not for sex attraction.”7 This opposition between exercise/occupation and repose/sex attraction, an opposition that maps onto daytime and evening activities, defines the evening gown and manifests itself in the particular materials and cut of the gown from year to year. Although the general line of day and evening dress may be parallel at any one time (hobble skirts for walking and evening dress, for example), the cut, materials, and trimmings of evening dress distinguish it as a garment suited to times and places where daytime dress could, according to fashion norms, not go.

Its opposition to daytime, and particularly occupational, dress allows the evening gown to materialize class as well as temporality. Because of the sheer expense of such garments, they articulated a woman’s economic status; in 1912, for example, a woman might pay 3.5 guineas for a summer suit and 5.5 for an evening dress, and in 1922, a “knitted woolen day dress” would cost 5 guineas, while an evening gown of velvet and georgette would cost 23 guineas.8 As sociologist Georg Simmel argued in 1908, the expense of evening dress could mystify the qualities of those who wore it:

Inasmuch as adornment usually is also an object of considerable value, it is a synthesis of the individual’s having and being; it thus transforms mere possession into the sensuous and emphatic perceivability of the individual himself. This is not true of ordinary dress which, neither in respect of having nor of being, strikes one as an individual particularity; only the fancy dress…, which gather[s] the personality’s value and significance of radiation as if in a focal point, allow[s] the mere having of the person to become a visible quality of its being.9

Simmel’s analysis suggests that evening dress enabled economic class to materialize social class; that is, the evening gown is not a dress that a woman owns but a stance and a position that she becomes. His argument foreshadows the profound interpenetration of human and thing that contemporary theorists sometimes refer to as an assemblage; in Simmel’s formulation, a human body in evening dress foments a visible identity that is simply different from the same body in “ordinary dress.”10 The materials, construction, and design of a gown rendered a woman as not just wealthy but finer than her less privileged counterparts.

Although Simmel casts this process as a kind of mystification, British evening dress was less sartorial false consciousness than a means of constructing class differences that were increasingly under stress in the twentieth century. As the century unfolded, and particularly after World War I, more and more women entered the workforce and increased their purchasing power. As a result of the so-called democratization of dress, a greater number of women could afford evening gowns, and in the view of some observers, this meant that class differences were less visible than they had been. The democracy-of-dress theory is addressed in chapter 4, but one example can illuminate the general argument: “Fashion has now become a democratic expression instead of being, as it once was, the exclusive symbol of the upper class outlook.”11 The evening gown was not, however, a form that lent itself to ready-to-wear and mass-production, and thus it served to synthesize superior having and being long after other garments had become available at a range of prices. For example, in his discussion of evening fashions of 1933, Cunnington writes that “as the skin-tight dress called for great skill in cut and fit[,] the cheaper models found it a difficult fashion to follow with success.”12 Even uncomplicated styles of evening dress were not easy for the middle and working classes to emulate. In 1929, the Encyclopaedia Britannica noted that when patterns became “quite simple” in 1924, dressmaking firms “began to make false jewels to match models and even to make perfumes to agree with the lines and colours of their models.”13 As Gilles Lipovetsky argues, evening gowns remained markers of “social distinctions and social excellence” through sumptuous, elaborate designs characterized by distinctive labels, shapes, and fabrics (figure 1.2).14 In short, some types of garments were less “democratic” than others; the evening dress continued to require a great deal of disposable income throughout the first half of the twentieth century.

While the evening gown thus materialized time and class, it was, most importantly, a means of assembling gender and emphasizing what was presumed to be heterosexuality. As Heglund observes, it is “a special form of dress that amplifies a woman’s femininity and often proclaims her desirability.”15 It specifically “draws attention to a woman’s body and serves to define her gender, establishing her as an object to be gazed upon by her audience.”16 Through emphasizing a woman’s body and producing her status as an object, the garment facilitated British courtship rituals, which required young women to wear the gown when “coming out” and older women to wear it for socializing and chaperoning. Elizabeth Wilson explains how carefully such dress positioned and pitched the cause of the women who wore it:

The dress of the…virgin on the marriage market had…subtly to convey family status as well as personal desirability: seductiveness, albeit virginal; along with apparent submissiveness and a willingness to obey, the ability to run a household should be suggested; the ethereal qualities of the Angel in the House must somehow be combined with the suggestion of sufficient health and strength to bear a large family. And in a society, or at least in a class, in which women outnumbered men, the importance for a woman of distinguishing herself from her rivals should not be overestimated.17

It is difficult to imagine such a complicated assemblage, balancing as it would spiritual and moral qualities with suggestions about the wearer’s reproductive capacity. Wilson’s prose endows the dress with almost mystical powers, and the passage implies that a young woman wearing such a gown could be silent, so loudly would her garment “speak.” Dressmakers had to negotiate the tensions between the body and the gown carefully; Lady Duff Gordon, better known as the couturier Lucile, recalled that her dresses for debutantes were often controversial: “Matchmaking mothers would stare anxiously at their daughters when I had dressed them in something that showed every line of their lithe young bodies and murmur: ‘Are you quite sure, dear Lady Duff Gordon, that it does not look too suggestive?’ ” She dismissed such suspicions, but showing the “line” of bodies was precisely the purpose of her designs and of the evening gown generally.18

Later in the century, commentators became willing to admit that the purpose of evening dress was to showcase the female body. In 1941, Cunnington baldly described evening dress as “a type of costume in which sex attraction is always a powerful motif.”19 The styles of the 1920s and 1930s had made this motive impossible to ignore. In the 1930s,

the conspicuous features of sex appeal were confined to the evening, when the “nudity principle,” carried on from the late Twenties, was further developed by moulding the dress to fit the body “clinging like a wet cloth.” This was achieved by cutting the material on the cross, and for the first half of the decade a thinly veiled anatomical demonstration, accentuated by the lavish display of bare backs, left nothing to the imagination.20

At such moments, the evening gown emerged as a means of hyper-genderization; emphasizing the body, femininity, and beauty, it positioned women as clothed and yet exposed in designs that demanded increasing levels of physical fitness and slimness.21 The bias cut, or “cutting the material on the cross” in Cunnington’s words, emphasized the wearer’s breasts, waist, and derrière, while a close fit suggested that a woman’s shape was not molded by foundation garments.

Throughout the early twentieth century, the evening dress materialized time, class, and gender in a surprisingly consistent manner. Although particular styles came and went—the S-shaped silhouette, flapper line, and bias cut looked quite different from one another—the function of evening dress was to produce a woman for leisure activities in which courtship and heterosexual attraction were the important, and often the main, features. Even World War I, which so altered women’s daytime pursuits and the ratio of men to women at dances, dinners, and other entertainments, little affected the garment. Some couturiers closed their ateliers for the duration of the conflict, and the Standard Dress movement briefly offered patterns that may have obscured class differences.22 Styles, however, continued to evolve and kept the gown’s function intact. Even commentators who want to suggest that the war altered the form ultimately imply that it was surprisingly resilient. Cunnington argues that in 1917, “owing to war conditions the evening dress…declined into almost a makeshift affair.” He continues, however, to observe that “the waistline, when apparent, is definitely higher than formerly,”23 which suggests that the gown evolved in a recognizable manner. Unlike the mackintosh, which was uniquely transformed by international conflict, the evening gown emerged as, if not ahistorical, stubbornly resistant to radical change. Although the cut of such dress altered dramatically over time, the manner in which it framed and positioned women remained consistent: as a sartorial genre, it seemed less reflective of most modern women’s lives than, for example, the sportswear that was increasingly popular for daytime attire.

For this very reason, commentators regarded British women’s evening dress as a particularly conservative form, and the twentieth century threw this tendency into high relief. Because the role associated with the garment was precisely the role challenged by many women in the period—and because other clothing evolved rapidly during the same time frame—evening dress could be, for the first time, perceived as a throw-back. As Cunnington observed in 1941,

It seems to be a rule that while sport has gradually done much to break down social conventions as regards the body, the evening dress has done nothing; this is due, of course, to the difference of the underlying motive, the one being a radical breaking away from sex-attraction and the other a conservative clinging to it. If we want to see modern dress design at its best with genuine inspiration we turn to the sports costume; if we want to see it at its worst, without inspiration and feebly imitative, we find it in the evening dress of today.24

As this passage demonstrates, dress historians regarded the garment as less socially significant and interesting than other garb that expressed changing attitudes toward women’s bodies and pursuits. Breaking away from the motive of “sex-attraction” was “radical” and resulted in innovative designs, materials, and styles; the evening gown, while changing from year to year, allowed for less experiment. It thus plays a comparatively minor role in some period dress histories. As the Encyclopaedia Britannica enthused in 1929, “The evolution of modern feminine dress, corresponding closely to the emancipation of women at the beginning of the 20th century, provides one of the most captivating pages in the history of modern civilization.”25 The entry illustrates “evening costume,” but the section on modern dress concludes by emphasizing “the influence of sport” on women’s clothing.26 Thus the emancipation of women would not spell an end to the evening gown, but it would highlight the garment’s relationship to dated versions of femininity.

Given this “life” of the evening gown, in which it served to materialize leisure, privilege, and femininity, it seems little wonder that so many feminist writers expressed a profound unease with and distrust of evening dress. But the garment is also represented in British popular culture of the period in surprisingly ambivalent ways. While we might expect that the evening gown would be an object of desire in films, fiction, and serials addressed to a popular audience—that such texts would convey images of enviable upper-class luxury—it instead emerged as a key player in assemblages that endanger women. The gown thus seems less desirable than risky, less enviable than an example of the limits of human control.

Overexposed: Evening Gowns in British Popular Culture

A woman in evening dress is threatened with violence and death; recollections of accidents are constructed around descriptions of evening gowns. Popular forms such as films, fashion magazines, and memoirs suggest that the sleeveless, décolleté styles of the early twentieth century correlated with a social exposure that threatened to ruin women in fashionable evening wear. In part, this seems a matter of simple titillation: if the sight of a woman in danger is exciting, a well-dressed woman in danger might increase one’s visual pleasure. But many representations of the evening gown in popular narratives go beyond mere titillation: fashion journalism points to the evening dress as the (unwilled) mirror of mourning clothes, and memories of a gown destroyed by total war suggest that the garment models the potential fate of the person who once wore it. In a range of cultural formats during the period, the gown looks less like a pleasurable object to consume than a material constellation of dangerous situations and painful memories to avoid.

The biograph film A Ballroom Tragedy (1905), for example, depicts a woman who is punished with the participation of her evening wear. Biographs offered a popular form of visual entertainment in the years before longer films—and the cinemas that showed them—were technically possible. Placed in or near seaside promenades, arcades, shopping areas, and other spaces where people congregated for leisure, biograph machines offered sixty seconds of moving pictures for a small fee. A viewer inserted his or her coin into a slot and then leaned into the machine, gazing through an eyepiece to watch the flickering image. There was a voyeuristic pleasure to watching these pieces, a pleasure captured in their nickname: “What the Butler Saw” machines.27 The films themselves were often suggestive, and a viewer expected to see shameless behavior of some kind.

The plot of A Ballroom Tragedy—if one can even call it a plot—is straightforward.28 Two couples meet and exchange partners, but when one couple takes advantage of their apparent seclusion to kiss, the gentleman’s original partner returns and exacts murderous vengeance. The titillation of this short film clearly depended on the characters’ transgression of gender norms and expectations. A viewer might anticipate that the original male escort of the woman in white, who enjoys the stolen kisses, will demand satisfaction from her partner in animal lust, but it is (seemingly) a female rival who instead murders her counterpart. More radically, the viewer could read the scene as a closeted lesbian drama: perhaps the murderer slays not a rival but an unfaithful lover. The lesbian’s apparitional quality (as Terry Castle has theorized)29 would account for the killer’s simply leaving the scene of the crime, with no notice taken of her disappearance. This reading highlights a fact that period fashion commentators elided: the sexual attraction mobilized by the evening gown was not necessarily heterosexual (a point I return to in my discussion of Jean Rhys’s “Illusion”).

While the woman in white is murdered in response to her behavior and not to her gown, on closer inspection, behavior, body, and attire emerge as inextricable—as an assemblage. It is clear that we are meant to distinguish between the film’s female protagonists through their garments. The two men in the film are all but indistinguishable from each other because their evening dress is so similar. Although the man who kisses the murder victim wears a white waistcoat, in contrast to the black waistcoat of the other man, the men’s clothing is otherwise identical: black ties, tails, and trousers. Men’s evening wear does not signal anything special about the wearer; in A Ballroom Tragedy, the men are only the backdrops to more meaningful sartorial forms.30

The evening gowns of the female characters, however, construct their roles before the sexual transgression and murder take place, and their dresses emerge not only as frameworks for human interaction (as texts) but as opportunities for action (as tools). The murder victim wears a far more revealing dress than does her counterpart. Although a long feather boa swathes part of her neck and shoulders, her white gown’s half-sleeves cover only her lower arms, and the tops of her breasts are clearly visible when she faces the camera. Moreover, the gown is largely backless, and the woman’s exposed back is precisely where the knife enters her flesh. While satin or silk would offer little resistance to a blade, the fact that the main character is literally stabbed in the back points to a correlation between her exposure and her murder—it suggests that the cut of her gown encouraged a particular assault. As the woman in white transforms from subject to object, human to corpse, in front of the viewer’s eyes, her dress emerges as quietly volitional: it does not kill its wearer, but it provides a literal and figurative opening (even, perhaps, an invitation) to the woman with a knife.

In contrast, the murderer’s dress covers her body. The satin gown has half-sleeves that conceal her upper arms, and a modest neckline exposes only her throat and upper sternum. This dress is less striking than that worn by the woman in white, and it proclaims the wearer’s comparative propriety. The dress might also serve to conceal her weapon; viewers have no way of knowing whether her attack was premeditated, but her more voluminous draperies could conceal a knife or dagger. A Ballroom Tragedy thus uses the evening gown to illuminate how the garment participates in events instead of serving as inert matter. The film revolves around gowns that project the wearers’ sexual mores and collaborate in producing particular actions. Without the specific dresses worn by each character, the women’s values would remain illegible and the plot of the brief film less feasible.

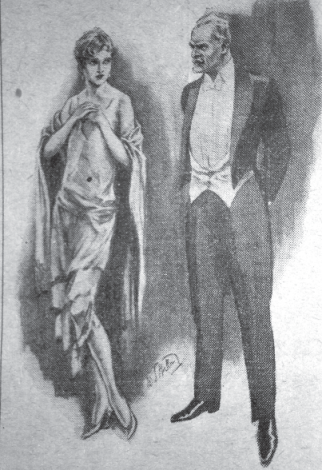

In film and mass-market fiction, images of women in evening dress threatened with violence present gowns as a menacing sartorial genre, as garments that expose not only women’s bodies but their lives. “The Harvest of Folly” (1928) by Kathlyn Rhodes, serial fiction published in the Sunday Graphic, provides representative examples of a type: the woman in a fashionable evening gown who is vulnerable to a specifically (in this case, hetero-) sexual violence. The story, which chronicles the attempt of Lesley Chester to retrieve a letter documenting a “youthful folly,” is illustrated by images of the main female characters in sumptuous gowns whose low necks and lack of sleeves correlate with a social exposure that threatens to ruin them. For example, when Lesley pleads with Lord Thirsk, a much older roué, for the return of the letter, she wears an evening gown, “the light shining on white neck and white shirt front.”31 The text highlights the contrast between women’s exposure and men’s composure: Thirsk’s “shirt front” may be visually parallel to Lesley’s neck, but his garments cover him, while hers expose her body and, seemingly, her past. Although Thirsk offers to give Lesley the letter if she will marry him, the illustration suggests that he menaces her with rape instead. As she clutches her hands to her chest and presses her knees together—strategies that work to compensate for the gown’s revealing cut—the caption reads, “Lord Thirsk…I want my letter more than anything in the world, but I can’t pay your price for it,” a line that implies that Thirsk has asked for a sexual, instead of a marital, payment (figure 1.3).

In this image and others in “The Harvest of Folly,” the gown—and the flesh it bares—positions the female character as open to unwelcome advances because of the very absence of boundary between body and world. Instead of working with the human body it clothes, the gown works against that body in a kind of negative-feedback loop that increases the garment’s power as the character’s agency diminishes. Although Thirsk obligingly dies of a heart attack and frees Lesley from this first threat, the rest of the story follows Lesley and her cousin Rosemary as they are “terrified,” offered (potentially drugged) Eastern cocktails, and otherwise imperiled while wearing white, pink, and black evening dresses (figure 1.4). In most of these illustrations, the characters place a hand on their neck (thus covering décolletage) or press their knees together, bodily responses to specific dangers and to a dress that provides little protection. Through illustrations and plot, “The Harvest of Folly” frames British evening gowns as conventional fashions that uniquely (no one is threatened in a tennis frock) and persistently expose upper-class women to negative experiences. It is as though the revealing styles of evening fashions in the 1920s made what women offered—and stood to lose—most clear to readers of the Sunday Graphic. Although the advice columns in the paper suggest that few readers could afford the kinds of dresses worn by the characters in Rhodes’s story, the evening gown helps to assemble types of women whose virginity and reputation hold a high value.

Films and popular fiction suggest, then, that the evening gown imperiled women in the first three decades of the twentieth century. While A Ballroom Tragedy and “The Harvest of Folly” were largely aimed at working- and middle-class audiences, even the upper class, which regularly bought and wore evening gowns, used complementary images for the dress. In such cases, it became a physical imperative to mourn, its implication less of present danger than of recent or impending loss. In 1920, the British women’s magazine Eve observed that the current craze for the tango was accompanied by a narrow sartorial style at seeming odds with the dance itself: “[W]e do, p’raps, take our tango with an arriere tang of melancholy. We are faintly funereal, and there is certainly something somewhat mute-like about the black and white garb of our dancers.”32 Thus dresses defined women as melancholic and silent; presumably, some women enjoyed the tango and accompanying parties, but this column described the fashions worn to them as formulating a general look of sorrow. Two years later, the Gentlewoman reported,

[B]lack no longer is the decree issued by Paquin [French designer]. It is with a sigh of relief that one hears the reign of black has ended. Our functions and parties were becoming positively funereal. Everywhere black. It was deadly and uninteresting, and though, I admit, exceptionally smart for occasions, it was certainly being overdone. Well, now it’s ended. Dame Fashion can now work one of her dramatic miracles that please her so much, and switch the world of mourning into a world of hope and spring.33

This striking passage points to the way in which some writers framed fashion as a form of foreign sovereignty that painted evening entertainments in a monotone. It would take a “miracle” to alleviate the “world of mourning” described in the column. Although the writer identifies a specific source for the color of evening gowns in the name of Jeanne Paquin, she also gestures toward intangible social forces in the personification of fashion and thus vacillates between causal explanations for the escape from the funereal. But “Dame Fashion” proved to be fickle, and later that decade, Jean Patou, in just one such example, was promoting a dress called Fugue in British Vogue. Constructed of sheer black tulle and black beaded fabric, the dress brought the “positively funereal” back into fashion—but, of course, the color had never left.34

The “world of mourning” and melancholy repeatedly described in the British fashion press of the 1910s and 1920s seems counterintuitive. If women did not like the black gowns offered by designers, surely they could have purchased dresses in other colors. But British women were repeatedly called on to wear mourning in the early decades of the twentieth century, a practice that extended to evening dress. After the deaths of Queen Victoria in 1901 and King Edward in 1910, for example, many British citizens, especially those in the upper class who could afford to do so, dressed in mourning. As Juliet Nicolson observes, Queen Mary, to provide just one (admittedly elevated) illustration, was obliged to wear mourning dress five times in a fifteen-year period.35 Magazines like the Ladies Field illustrated mourning evening dress for women in the court,36 and the Times published many advertisements for “Court and General Mourning,” including at least one placed by Maison Paquin.37 The Messel Family Dress Collection archives many black evening gowns and capes worn by Maud Messel that date from 1910 to 1914. Their sumptuous trimmings and materials included silk chiffon, sateen, and taffeta as well as jet beads, velvet ribbon, Guipure lace, braid, and sequins, all in black (figure 1.5; see figure 1.2). Some of these dresses were made by Mrs. Neville, a London designer, which demonstrates that mourning was not anti-fashion but resulted in the incorporation of black into garments, including the evening gown.

In addition to royal deaths, many women had private reasons to don mourning clothes during World War I, as a result of the influenza epidemic of 1918 and 1919, or after isolated deaths from natural causes. Vanessa Stephen wore such an evening dress in 1897 after the death of her half-sister Stella. Her dressmaker “concocted a dress that suggested mourning yet was also fashionable and pretty: transparent black material sewn with tiny silver sequins hung over a white underdress.”38 Her biographer’s description of the dress as “pretty” but also fitting within the codes of mourning illustrates the way that this specific evening dress synthesized the wearer’s loss and her ability to remain fashionable and desirable. Moreover, women who once purchased mourning attire sometimes continued to wear black; as the Illustrated London News observed in 1910, black “is…becoming to a great many women who have, perhaps, seldom allowed themselves the opportunity of seeing themselves attired in exclusively black until national feeling required the change.”39

Although mourning dress gradually fell out of favor during the twentieth century, it did not become rare in Britain until the 1950s.40 Fashion columnists’ laments about the prevalence of black in evening dress—and their characterization of such dress as melancholic and funereal—point to a specific period when such garments were a form of mourning. It seems little wonder that the funereal would itself become fashionable in a period when so many women were called on to observe social rituals of mourning. Surprisingly, however, columnists repeatedly lamented that black dresses themselves materialized emotional states, and they represented women as unequal partners with gowns that assembled negative affective experiences long after mourning proper had ended.41

Such gowns could also lead women into situations that would require mourning. The “fate” of specific dresses recalled in memoirs positions the evening gown as a victim of the violence, death, and destruction so widely visited on material of all kinds during and after World War I. The Viscountess Rhondda (Margaret Haig), who was active in the Women’s Social and Political Union and was one of the founders (and later editor) of Time and Tide, used evening dress to capture the vulnerability of humans and garments to military threat. Although she seldom describes specific garments in her book This Was My World, evening gowns emerge as exceptions, and one provides a way back into the memory of the sinking of the Lusitania. As a young woman, Haig worked as her father’s confidential secretary, which required an appropriate wardrobe: “In the evenings—almost every evening—we went out, either to the theatre or to dinner parties. With money supplied by my father, I bought a lot of frocks in which I fancied myself very much, particularly in one black velvet evening one.”42 To this point in her account, Haig’s experience of evening dress seems positive, an example of such gowns working in a harmonious assemblage with, and not against, a wearer. After mentioning the black velvet gown—the only gown that she specifies in this section of her memoir—Haig describes the fate of this dress and others: “[T]hey all went down in the Lusitania.”43 Haig and her father survived, but her garments did not, and their watery fate highlights what might have easily happened to Haig herself. The writer no doubt lost many possessions in the sinking of the ship, but it is the loss of her evening dress, and especially the black velvet gown, that Haig recollects in her memoir, a choice that points to a particular linkage between woman and gown. While the evening dresses in A Ballroom Tragedy and “The Harvest of Folly” testify to the dangers of overexposure that the gowns permit, Haig’s memoir singles out the black evening dress to represent her bodily exposure to military violence. Collectively, such texts reveal evening gowns as singularly cathected garments in fiction and memory—as a form of dress repeatedly chosen to construct and represent physical and emotional harm.

Instead of mobilizing a wearer’s taste and social competence, the evening dresses in films, popular fiction, fashion journalism, and memoirs participate in terrifying events and conjure negative memories. Evening dress thus serves to trouble certainties, especially about mortality, and representations of it emphasize the ways in which sartorial forms subtend and complicate human (particularly women’s) agency. Grosz, in assessing the relationship between human bodies and things, has argued that “the thing and the body are correlates: both are artificial or conventional, pragmatic conceptions, cuttings, disconnections, that create a unity, continuity, and cohesion out of the plethora of interconnections that constitute the world. They mirror each other: the stability of one, the thing, is the guarantee of the stability and on-going existence or viability of the other, the body.”44 As the representations addressed in this section suggest, however, the thing can also create discontinuity and disconnection—it can remind readers, viewers, and individuals that the body is not guaranteed an ongoing existence. In fact, evening dress often suggests that this particular thing can make a body less viable. The evening gown of the early twentieth century served to articulate this condition particularly well, in large part because of social practices and events peculiar to Britain. It helped to create and illuminate the exposure of women to revenge, assault, and even international conflict.

Although the evening gown was a form of conventional attire and undoubtedly provided pleasure for countless women, mass media and memoir did not naturalize the garment but instead highlighted its ability to construct particular kinds of subjects—murder victim, murderer, mourner, and survivor among them. Striking parallels emerge between such representations and those produced by professional writers, whom one might expect to reject the garment’s conservative gender norms. And, indeed, the work of Virginia Woolf, Rebecca West, and Jean Rhys conveys suspicion of and anger toward this form of dress. These writers express more pointedly political reservations about the garment than we have yet seen, but their letters, stories, and essays also highlight the sensory pleasure that evening attire solicited. They thus articulate a profound uncertainty about a gown that beautified and crippled simultaneously and highlight the power and life of the garment. These complicated representations of the evening gown illuminate human–nonhuman relationships that are ubiquitous but uneasy.

The World’s Worst Failure(s)

Given the evening gown’s articulation of sex appeal and upper-class leisure, it seems little wonder that the fiction and nonfiction of professional women writers contain extensive meditation on the dress. What is unanticipated are the largely consistent ways in which these writers represent the evening gown: through figures of death, failure, mourning, and depression. Strikingly, feminist authors ascribe these emotions not only to women but to the gown itself, animating the garment with an affective life and the power to direct human behavior. Such representations of the evening gown are also tinged with melancholy—with admissions of attachment to and pleasure in dresses and styles that emerge as threats to the lives and careers that the writers painstakingly carved out for themselves. In part, the ambivalence stems from the history of the gown; as Diana Crane reminds readers, by the turn of the twentieth century, “fashionable clothing embodied gender ideals that no longer corresponded to the realities of women’s lives, as women became better educated, entered the workplace in greater numbers, and participated in political activities.”45 It thus makes sense that feminists often highlighted the evening gown’s regressive powers. At the same time, this critique threatened to make inaccessible an ongoing source of visual, auditory, and corporeal pleasure, rendering professional women frustrated and occasionally angry.

In August 1901, Virginia Stephen—not yet the famous writer Virginia Woolf—confessed her lack of success as a debutante in a letter to her friend Emma Vaughan: “Really, we can’t shine in Society. I don’t know how it’s done. We aint popular—we sit in corners and look like mutes who are longing for a funeral.”46 The simile was clearly meant to amuse Vaughan, but the image of Virginia and her sister Vanessa attired in evening gowns but longing for (and sometimes wearing) a formal ritual of mourning is an acute example of Woolf’s “frock consciousness.” This feeling, which Woolf discusses in her memoir “Am I a Snob?,” encompasses a painful sense of inferiority centered on her appearance in and purchase of clothing.47 While Woolf was no more comfortable in casual than in evening dress, she writes about the latter both very early and late in her adult life; accounts of gowns feature in her letters and diaries as early as 1901, and she returned to evening dress in “22 Hyde Park Gate” (1920), “Old Bloomsbury” (1921–1922), and “A Sketch of the Past” (1939). In these texts, Woolf represents failures and transgressions achieved through the evening gown to mark her nascent challenges to traditional gender roles as well as to admit the compelling allure of a sartorial competence that she never achieved.

Her youthful letters capture the norms of adult female behavior as refracted through one particular act: donning an evening gown. The young writer was delighted by and interested in her debutante apparel. In a letter from 1901, she reports the delivery of several gowns that, in her words, “deserve to be shown.”48 Her appearance in such gowns must have been strikingly different from the images we now have of her, in which she is demurely covered to the neck by layers of fabric and lace. In “A Sketch of the Past,” Woolf describes the process of donning her evening wear in a passage that provides a glimpse of how she may have looked in 1901: “At seven thirty we went upstairs to dress. However cold or foggy, we slipped off our day clothes and stood shivering in front of washing basins. Each basin had its can of hot water. Neck and arms had to be scrubbed, for we had to enter the drawing room at eight with bare arms, low neck, in evening dress.”49 Woolf’s descriptions emphasize her body’s exposure in evening gowns as well as the materials that went into making and accessorizing them; one dress was made of satin and ornamented with “long white gloves,” “satin shoes,” and a necklace of amethysts or pearls.50 White satin and amethysts became tropes for evening dress in Woolf’s memoirs; thus attired, Virginia and Vanessa would depart for the evening’s engagements.

Although in hindsight Woolf would recall 7:30 as the time when “dress and hair overcame paint and Greek grammar,”51 at the time she enjoyed the “thrill” of her evening gowns and the circumstances they enabled: “[F]or the first time one was in touch with a young man in white waistcoat and gloves; and I too…in white and gloves. If it was unreal, there was a thrill in that unreality.”52 The “white and gloves” serve as a reminder of the “road most traveled” for young women of the author’s class at the turn of the twentieth century. In reading such descriptions, it becomes clear that she was, literally, outfitted in expensive garments that assembled her status as a potential, and traditional, wife and mother.

But Woolf felt that the gowns, gloves, and amethysts never quite fit. Or, rather, despite her apparent beauty, she felt herself out of harmony with objects through which she moved. Her confession that “we aint popular—we sit in corners and look like mutes who are longing for a funeral” thus marks a failure that is at once social and aesthetic. Although “mutes” might signal a literal silence, the conflation of the oral and the visual in this letter indicates that there was also something wrong with her “look”: she looked like a mute. Instead of harmonizing with the attire that might have rendered her an attractive debutante, she appeared silent and mournful. Like the fashion press, then, these letters align the evening gown with the funereal even when that dress was not fabricated in mourning colors.

Later correspondence suggests that the young writer found the gown an alienating form because it required mastery over an object world that she seldom achieved. Subsequent public appearances in evening gowns were marred when Virginia Stephen, “all glorious without,” scandalized bystanders as an undergarment—presumably her drawers, since she describes it as “not the one one talks about”53—fell to the floor. Such public humiliations serve as a reminder of the difficulty of coordinating the wearing of a gown, underclothing, and accessories before the invention of the zipper, elastic, or Velcro: each piece could misbehave and mar the “glory” that the assembled result was meant to convey.

Woolf’s attempts to experiment with less conventional evening fashions were no more successful than her appearance in designer gowns. “A Sketch of the Past” chronicles an evening gown “made cheaply but eccentrically, of a green fabric, bought at Story’s, the furniture shop. It was not velvet; nor plush; something betwixt and between; and for chairs, presumably, not dresses.”54 At once a trial balloon and an attempt by a wallflower to mimic the wall, to provide herself with better “cover,” this dress made the wearer “apprehensive, yet, for a new dress excites even the unskilled, elated.”55 The green dress highlights the evening gown’s ability to elicit pleasure—its potential to serve as a form of aesthetic expression and to create affective bonds between human and thing. This experiment, was, however, short-lived.

The author’s half-brother and escort, George, rejected this gown, instructing her to “tear it up.” This rejection, Woolf wrote, was based on the gown’s “infringement of a code”56—its perceptual challenge to values that the evening dress traditionally communicated. The dress thus expressed, in material form, Virginia Stephen’s desire to contrast with fashionable debutantes: it relayed, as an object, the young woman’s nascent quest for a form of difference. That Woolf recalls the green dress over three decades later to illuminate a conflict with her half-brother, whom she characterizes as a “fossil of the Victorian age,” suggests the import of this specific evening gown to her construction of personal history. This passage allows the author to highlight her eventual escape from the “fossil,” but the upholstery dress, and its categorical rejection by George, leads into a metaphoric description of his violent response. George was, Woolf writes, a “machine” that “bit” into her “with innumerable sharp teeth.”57 Although her other half-brother liked the green dress, George’s “teeth” kept her from wearing it again in his presence. The dress, which initially materialized the young writer’s eccentric and creative take on the evening gown, thus came to represent her lack of agency in her turn-of-the-century, patriarchal household.

Woolf’s evening gowns, then, are textually linked with mourning, embarrassment, and (failed) insurrection. Although many of her metaphors are infused with wit and irony, her sense that “the coffin of my failure” was firmly “nailed” by her inability to incorporate the evening gown signals an ambivalent response to her largely unwitting noncon-formity.58 By the time Woolf wrote “A Sketch of the Past” in 1939, the coffin of her social and sartorial failure could signal the fact that she was always destined to become the kind of woman who would marry Leonard Woolf, remain childless, and publish some of the twentieth century’s most important novels and feminist polemics. And yet, we should not let the trajectory of Virginia Woolf’s life obscure Virginia Stephen’s sartorial mortification.

At the time they occurred, the young woman’s forays in evening gowns left her conflicted. For all of her jokes, she confessed that she felt “all the pretty young Ladies far removed into another sphere.”59 And in her diary, she wrote that it was a really noble ambition” to merge one’s behavior with an elegant appearance: “You have, for a certain space of time to realise as nearly as can be, an ideal. You must consciously try to carry out in your conduct what is implied by your clothes; they are silken—of the very best make—only to be worn with the greatest care, on occasions such as these. They are meant to please the eyes of others—to make you something more brilliant than you are by day.”60 We might be tempted to excavate Woolf’s famous irony from these lines, but for a time she saw in the evening gown an “ideal” to which she might aspire. Her suggestion that such dress might make one “more brilliant than you are by day” echoes Simmel’s claim that the gown assembles higher states of being than those achieved through ordinary dress; the writer, significantly, articulates the gown’s activity in the same diction used for intellectual achievement—brilliance. Virginia Stephen’s knowledge of Greek, grammar, and writing set her apart from other young women her age, but her admiration for an elegant appearance—and her frustration that she could not achieve it—is captured in the coffins and funerals with which she represents evening dress.

Like Woolf, Rebecca West understood the appeal and menace of evening dress.61 In “The World’s Worst Failure,” West’s titular disaster is embodied by women in evening dress, and the category encompasses those who make a successful appearance and those who are marred by various imperfections. The text asserts that the garment is incompatible with intellectual achievement; moreover, the piece suggests that material objects solicit affective bonds that motivate unworthy work—that “brilliance” at night (Virginia Stephen’s word) comes at the cost of a dimming of one’s talents by day.

West’s narrator begins by describing a French woman who emerges as the perfect example of well-dressed femininity:

Her body was not the loosely articulated thing of arrested and involuntary movements that serves as the fleshly vehicle of most of us, but was very straight and still, with the grace of flowers arranged by a florist, with a dress so beautiful that one imagined it hard and permanent like a jewel, yet so supple of texture that one could have crushed it into a handful. It was the aim of her fragility to rouse such thoughts of violence.62

“The World’s Worst Failure” casts the woman in evening dress as neither self-willed nor entirely safe. West’s metaphor of flowers that have been arranged by another frames the woman as less self-articulating than styled. Such figurative language also underlines the perishable nature of the woman in the gown; while her dress may have the permanence of a mineral, she herself provokes the desire to crush, assault, and destroy. West’s use of the passive voice represents the woman as only partially responsible for arousing desire. To be elegant and well attired thus emerges as a sartorial expression of object status—the inorganic world (“like a jewel”) impinges on the organic flower/body and renders it, too, a thing.63

As the essay continues, West represents the French woman in her gowns as on par with other items in the object world that take their meaning from interaction with human subjects. Noting the woman’s boredom and loneliness, West ascribes her condition to a lack of use: “One perceived in her discomfort that there must be many sorts of pain of which no cognizance is taken in this world: the anguish of the chair on which nobody sits, the wine that is not drunk, the woman bred to please when there is no one at hand to be pleased.”64 West’s comparisons liken the fashionable woman—and the essay aligns fashionability specifically with the evening dress—to an animal or object. While such a thing may feel pain, an emotional response that West credits and recognizes, the writer seems to set herself above or outside this object world, where she writes about but does not experience the impact of “the system of the chic.”65 The essay articulates an ontological binary (subject/object) but also begins to complicate objects by attributing emotional states to them; these are things that West thinks through but that also themselves think and feel.

As the piece continues, however, West suggests that there can be no simple rejection of the evening gown—no subject position above or out-side the anguished object world. The narrator examines her own appearance in a mirror:

And I—I was a black-browed thing scowling down on the inkstain that I saw reflected across the bodice of my evening dress. I was immeasurably distressed by this by-product of the literary life. It was a new evening dress, it was becoming, it was expensive. Already I was upsetting the balance of my nerves by silent rage; I knew I would wake up in the night and magnify it with an excited mind till it stained the world; that in the end I would probably write some article I did not in the least want to write in order to pay for a new one. In fact I would commit the same sin that I loathed in these two women. I would waste on personal ends vitality that I should have conserved for my work. And I was sinning for the same reason, for what could make me drape myself in irrelevant and costly folds of petunia satin, and what could make me forfeit my mental serenity at their defacement, if it were not for some deep and overlaid but sturdy instinct for elegance?66

The speaker is roused to anger—to “silent rage”—by her appearance; in the mirror, West apprehends herself as a damaged object far from the ideal that such a reflection might consolidate.67 She, too, becomes a “thing” experiencing the kind of pain “of which no cognizance is taken in this world.” The ink stain points to a bleeding of the narrator’s professional (daytime) pursuits into her personal (evening) life, an exchange that travels in both directions: her literary pen mars the gown, and its replacement will mandate intellectual work of the kind she would other-wise avoid. The power of the pen is thus equaled by the power of “petunia satin,” which might be “irrelevant” but also answers a desire—West calls it an “instinct”—for beautiful gowns and the fantasy of self-consolidation that such gowns may enable.

West’s entire description expresses skepticism about sensual and aesthetic pleasure; it is “work,” and not the garment, that the speaker values even as she knows that she will commit herself to the labor necessary to replace the dress. The passage thus illustrates West’s acceptance of, in Kathryn Laing’s words, “a variety of negative assumptions about femininity and the feminine,”68 but it more importantly illuminates the push–pull of the object world, which alters West’s career plans and trajectory. “The World’s Worst Failure” deploys the gown to highlight both woman’s status as thing (the French woman, the narrator in the mirror) and the garment’s ability to direct agency, a power normally ascribed to human subjects. At this moment, woman and dress have an inextricable relationship in which the position of “primary” and “accessory” blur, and West thus draws attention to the evening gown’s singular ability to complicate the subject/object binary. If the essayist acknowledges that pleasure ensues when dress and wearer work as a harmonious (if heterogeneous) assemblage, West can represent the pursuit of such pleasure only as folly: the essay concludes that the love of dress renders woman “the world’s worst failure.”69 Replete with images of rage and disappointment, West’s essay inscribes the evening gown as a material site of negotiation and struggle.70

Like Woolf and West, Jean Rhys examined the intimate relationship between women and evening dress that led to feelings of frustration, loss, and anger. Her short story “Illusion” (1927) animates the evening dress, thus building on the work of her contemporaries. It also portrays the tortured relationship between woman and dress as the result of a particularly British malady: a closeted desire for sartorial pleasure. Reversing West’s optic and viewing a British woman, Miss Bruce, from the perspective of the unidentified Parisian narrator, “Illusion” suggests that there is something anti-British about fashionable evening dress and that the garment both suffers at the hands of women and makes them suffer.

The opening paragraphs of the story establish the main character, Miss Bruce, as a British artist living in the Latin Quarter. The narrator’s descriptions position Bruce as an exemplar of British femininity: “One thought of her as a shining example of what character and training—British character and training—can do. After seven years in Paris she appeared utterly untouched, utterly unaffected, by anything hectic, slightly exotic or unwholesome.”71 Rhys’s subtle irony casts Bruce’s style as a form of sensible British habitus; her daytime attire is a personal uniform (serge dress in the summer and tweed costume in the winter), and when going out in the evening, “she put on a black gown of crêpe de chine, just well enough cut, not extravagantly pretty.”72 By the time the reader reaches the meat of Rhys’s story, Bruce has been firmly established as a British woman in, but not of, Paris. She also has been established as a queer character; the narrator observes that Bruce speaks with a “thoroughly gentlemanly intonation” and “looks appraisingly” at pretty women when they pass her.73 While Rhys’s story does not go so far as to explicitly identify Bruce as homosexual—indeed, the character ignores the “worship of physical love” “going on all the time all around her”—readers in the know may have readily identified the character as queer or as a closeted lesbian.74

The plot of “Illusion” revolves around the narrator’s exploration of Bruce’s boudoir. Bruce has been hospitalized, and the narrator must prepare an overnight bag for her. Opening Bruce’s wardrobe—“a big, square solid piece of old, dark furniture, suited for the square and solid coats and skirts of Miss Bruce”75—she makes a discovery: the tweedy Bruce collects exquisite gowns that she does not wear in public. The narrator finds a “glow of colour, a riot of soft silks”: “In the middle, hanging in the place of honour, was an evening dress of a very beautiful shade of old gold: near it another of flame colour.”76 The evening gowns occupy a place of honor in Bruce’s closet because they are the pinnacle of feminine fashion—the garment most able to produce an idealized class and femininity. Yet these gowns are never worn.

Bruce’s decision to buy, but never publicly wear, her evening gowns results in two outcomes. It first reveals a surprising side to the queer, British Bruce, and here Rhys sounds a great deal like West writing a decade earlier. The narrator guesses that Bruce was tempted to purchase the gowns by “the perpetual hunger to be beautiful and that thirst to be loved which is the real curse of Eve.”77 Notably, the narrator imagines that Bruce could assemble a flattering look with her garments and makeup; the problem inheres in her unwillingness to venture outside her apartment when thus transformed. After donning a new dress and cosmetics, the narrator speculates, Bruce would “gaze into the glass at a transformed self” and think, “No impossible thing, beauty and all that beauty brings. There close at hand, to be clutched if one dared.”78 Unlike West’s narrator, Rhys’s character consolidates an ideal through the evening gown; the object, and the objectified reflection in the glass, enables a fantasy of unity and control that so few literary characters achieve through the garment. Despite this success, “somehow she never dared.”79 This passage casts Bruce as a closeted devotee of the chic who experiences profound pleasure in and desire for the kind of feminine display that the evening gown allows.80

Bruce never makes this display by wearing her gorgeous gowns to parties, perhaps because she has constructed a professional persona—”clean, calm and sensible”81—that she cannot reconcile with the daring, beautiful thing she perceives in the mirror. Moreover, her sexual persona, which might better be described as an asexual persona, would be undone by a dress that emphasizes femininity. Invested in a form of depth ontology (surface/depth) that privileges masculine British character traits instead of feminine appearance, Bruce restricts herself to material assemblages that convey who she thinks she “really” is. As an artist, like the West of “The World’s Worst Failure,” she regards evening fashions as an indulgence for models (female objects) but not for painters (male subjects); the story concludes with her admiring another woman’s hands and arms in a “gentlemanly manner.”82 Such behavior puts her dresses, and her desire for them, back in the literal and figurative closet.

In addition to revealing a repressed side of Bruce’s, and Britain’s, sartorial life, the narrator’s descriptions of Bruce’s wardrobe animate the gowns inside. She fantasizes about a new dress arriving and becoming all but articulate: “ ‘Wear me, give me life,’ it would seem to say to her.”83 But such life is seldom granted, and before she leaves Bruce’s apartment, the narrator regards the dresses as locked up and aware of their imprisonment: the evening gown of old gold “appeared malevolent, slouching on its hanger; the black ones were mournful.”84 After animating the objects with this personification, the narrator further anthropomorphizes the gowns as she “felt a sudden, irrational pity for the beautiful things inside. I imagined them, shrugging their silken shoulders, rustling, whispering about the anglaise who had dared to buy them in order to condemn them to life in the dark.”85 Bruce’s French-speaking dresses are, figuratively, buried alive. Endowing the dresses with speech, the narrator casts them as French subjects repressed by a British woman who dares not wear them. Once again framing Bruce’s inability to wear the evening gowns as a peculiarly national condition, the narrator imagines the dresses not as objects but as things that may have desires for the future at odds with those of the woman who nominally owns them. But one has to consider the perspective of the object to see it as a thing—as more than inert matter—and Bruce seemingly does not adopt this view.86

Or perhaps she does. “Illusion” concludes with a recovered Bruce describing the contents of her wardrobe as a “collection” as she “carefully” stares over the narrator’s head. Refusing to meet her friend’s gaze, Bruce states, “I should never make such a fool of myself as to wear them…. They ought to be worn, I suppose.”87 Here, Bruce appears to concur with the narrator’s compassion for the garments that will not be worn. “Illusion” echoes West’s description of the “many sorts of pain of which no cognizance is taken in this world: the anguish of the chair on which nobody sits, the wine that is not drunk,”88 and, Rhys might add, the evening gown that is not worn. The story reveals the repressed passion of Bruce and makes the reader pity her self-denial and depicts the death-in-life of the Parisian gowns that, like Bruce’s desires, remain closeted. A dress, Rhys suggests, solicits a woman’s purchase but, more importantly, wear; women who ignore the garment’s vital objective run the risk of repressing the object world’s needs and their own. The story thus encourages readers to listen to the thing, an activity that is not an abstract philosophical exercise: “Illusion” suggests that in the desires of the thing, one will find the desires of the so-called self.

The evening gown became a touchstone for Virginia Woolf’s, Rebecca West’s, and Jean Rhys’s examinations of garments, traditional forms of femininity, and the lives of women artists. Because it reveals the body during evening entertainments far removed from professional achievement, it became a profoundly intense site of frustration, humiliation, and anger. Woolf’s anguished experiences with evening dress convey her dismay at unwitting nonconformity and her resentment when thwarted in her attempts at fashionable experiment; West endows the garment with life by blurring the subject/object binary and by recording the dress’s power to impinge on her profession; and Rhys maps such problems onto a British, national femininity and expresses the interpenetration of the life of the thing and that of the human. Together, such representations frame the garment as embodying conservative gender roles but also as expressing its own trajectory toward a public life. These texts complicate and question long-accepted assumptions about the object world’s passivity, in part through unsettling the subject/object binary and in part through an affective response to things. Feminist writers cast women in the evening gown as at the mercy of their clothes; such representations uncover power sharing between people and garments that does not always prioritize human needs.

While Woolf and West viewed evening dress as the province of women who were not like them (Woolf’s “pretty young ladies,” West’s French woman), it also becomes clear that, for these women, the gowns solicited desire even if such desire was “pathetic” (Woolf), a mark of “failure” (West), or an “illusion” (Rhys). The glimpses we get of sartorial pleasure—West’s “petunia satin,” Rhys’s “riot of soft silks,” and others—often recede into the background, but they do not disappear. The evening gown held out the possibility that it might give aesthetic pleasure to the wearer and might “make [a woman] something more brilliant than [she is] by day.” It was this very possibility that Ottoline Morrell explored.

Making It Quaint: Ottoline Morrell’s Experiments in Evening Dress

While Woolf, West, and Rhys generally purchased their evening gowns from dressmakers and couturiers, and thus did not wear their own designs, some of their contemporaries used the garment as a platform for aesthetic experimentation. One of them was Ottoline Morrell, an aristocrat, artistic patron, and society hostess whose unusual garb is one of the reasons she is so well remembered.89 Her unconventional evening gowns were not, or not only, careless or gaudy but an artistic venture that should be placed alongside other modernist aesthetic experiments.90The way we read Morrell’s gowns matters because we can then parse the negative representations of her appearance in the works of her contemporaries; if, as Alfred Gell has argued, “vulnerability stems from the bare possibility of representation” of the self in and as object(s),91 Morrell provides an especially poignant example of how, when, and why evening gowns assembled a caricature. Morrell’s fearless venture into an everyday aesthetic praxis was on a par with the goals of the Omega Workshops in its daring, if not in its eventual popularity, but the artists and writers who knew her insisted on inscribing her style as, at best, characterized by aristocratic excess and, at worst, a lamentable failure. Like the main character of Woolf’s short story “The New Dress,” which I will also discuss, Morrell’s gowns served to complicate human agency in romans à clef and literary history.

So what did Morrell’s garments look like? Many of her gowns that have been archived by the Fashion Museum in Bath date to the 1910s and 1920s and indicate the hallmarks of Morrell’s mature style. When she wore sleeveless gowns, she often festooned them with wide lace collars, which would have concealed her upper arms.92 Her gowns were either high-waisted or more daringly fashioned with a long straight bodice, dropped waist, and flared skirt. Such garments were the product of collaboration with her dressmaker, Miss Brenton, and occasionally with her daughter’s lady’s maid, Ivy Green. Morrell would provide the inspiration for the gowns, usually in the form of postcards or sketches, as well as the fabrics and trimmings for their construction. Brenton, for her part, weighed in on designs and assembled gowns quickly. As Morrell’s biographer Miranda Seymour has noted, the gowns “seldom cost more than three guineas,” a pittance for a woman who was the half-sister of the Duke of Portland. In Seymour’s words, this low cost was due to rapid production: “[S]eams were skimped, lining was not used, fastenings were minimal, hems and turnings were often tacked into position.”93 Brenton sometimes would “stretch” materials to prevent the need to buy additional yards of costly silks and satins. In one gown, for example, a cuff was pieced together with scraps that would normally have ended up on the dressmaker’s floor.94 Seymour likens such garments to “theatrical props” and writes that “Ottoline’s dresses were designed, not for comfort, but to stir the imagination of the viewer.”95

Morrell’s appearance was thus an expression of being not in, but in negotiation with, fashion.96 Her attitude toward dress design is reflected in a letter to Morrell from Brenton, who lamented that “it is so difficult to keep out of the fashions as the narrow frocks do suit you so much…but we must make our things quaint and unusual by the colouring or embroidering.”97 Morrell and Brenton’s design credo indicates that the dresses they produced were meant to resist, not follow, current styles; if a fashionable line suited Morrell, an evening dress would be made of unusual materials. The designs and fabrics thus worked in dynamic tension with one another. In a black velvet and copper print gown, for example, a modern pattern competes with pouf beret (melon) sleeves, a style popular in the 1830s (figure 1.6). The contrast between the historical allusion—or anachronism—and the modern materials makes this dress an example of that most modern of mantras: Pound’s “make it new.” Thus we might articulate Morrell’s credo as “make it quaint” or “make it unusual”; in either case, her style was meant to flatter and to signal a departure from fashionable norms.

Such gowns underline Morrell’s sense of tradition—in this case, fashion’s traditions—and of the “historical sense” that T. S. Eliot, for his part, was defining as “indispensable” for modern poetry. Read, if you will, Eliot’s famed treatise “Tradition and the Individual Talent” while imagining him not as the marmoreal author of The Waste Land but as a fashion columnist for Vogue:

[T]the historical sense involves a perception, not only of the pastness of the past, but of its presence; the historical sense compels a [designer] to [create] not merely with his own generation in his bones, but with a feeling that the whole of the [history of costume] of Europe…has a simultaneous existence and composes a simultaneous order. This historical sense, which is a sense of the timeless as well as of the temporal and of the timeless and of the temporal together, is what makes a [designer] traditional. And it is at the same time what makes a [designer] most acutely conscious of his place in time, of his contemporaneity.98

While Eliot would, no doubt, be horrified to have his model of aesthetic praxis applied to Morrell’s gowns, his argument—not only here, but generally—usefully helps us frame the designs, materials, and effects of Morrell’s dresses as a careful blending of stylistic allusion with innovation, and of traditional and modern materials into something new. With a silk-taffeta gown, Morrell balanced the fabric’s modern print with handmade lace, which adorns the collar.99 Paired with staid colors or prints, the lace would have seemed a traditional trimming for a British aristocrat’s gown, gesturing toward generations of bespoke clothing, high-quality materials, and refined dress. Tacked to the neckline of a gown constructed of fabric with an unusual print, however, the lace positions the dress in relation to the “standards of the past” (Eliot again) and stakes a claim for the innovation of the gown and, by association, its wearer.

Such designs attracted the attention of two major fashion photographers and the fashion press. Morrell was repeatedly photographed by Baron Adolf de Meyer, the first fashion photographer to be officially appointed by American Vogue and a contributor to Alfred Stieglitz’s Camera Work. Although his photographs of Morrell were not, to my knowledge, featured in Vogue, she was twice profiled in that magazine.100 In 1928, Morrell’s personal sense of style was celebrated in a full-page photograph taken by Cecil Beaton, the most famous fashion photographer of his day (and one of the best-known such photographers of all time) (figure 1.7). The identification of Morrell in the photo’s caption underlines one of the reasons that she was a particularly appropriate sitter for Vogue: she embodied the balance the magazine tried to strike among coverage of high fashion, the avant-garde, and Britain’s social elite.101

Beaton’s photograph and Vogue’s caption displays Morrell at her sartorial zenith. There is ample allusion to history in Morrell’s style, including her pearls, her favored beret sleeves, and the brocade pattern of the gown’s fabric. The reference to her “Goya manner” similarly locates Morrell historically; her appearance works in a tradition of high-art forms that Vogue’s readers were expected to recognize. At the same time, Morrell’s fan is decidedly modern, almost futurist, in design, adding a piquant counterpoint to the traditional elements of the costume. Finally, the off-the-shoulder cut of the gown balances the historical and the contemporary, alluding both to the 1820s (Goya’s final decade) and to the influence of Spanish art on postwar fashion, particularly between 1921 and 1925.102 Morrell’s “Goya manner” was thus of the past and the present, an assemblage of inspirations, styles, and forms that made her unique.

Through the lens of Beaton, and in the pages of Vogue, Morrell emerged as a significant practitioner of a unique style, one that combined traditional and innovative elements and took its place among both the fashionable and the avant-garde. Despite this celebration, Morrell was well aware of the occasions when her sartorial experiments failed. In her memoir, Morrell recalled a trip to stay with “established people” when she found her own clothing inappropriate: “I packed my best dresses, which somehow, when shaken out and worn, seemed absurdly fantastic and unfitting for the company and the surroundings. These that at home I was so proud of and thought so lovely would suddenly be transformed into tawdry ‘picturesque’ rags, making me feel foolish and self-conscious in wearing them.”103 As Morrell’s reflection indicates, new surroundings could alter her affective relationship to a garment as the object world impinged on and reconfigured it. This description neatly captures the dynamic relationships among the body in a gown, the gown itself, and the physical environment around it; had Morrell felt comfortable in her dresses, it seems likely that she would have ignored the role of things (dress and surroundings) in assembling that state. It is instructive to compare Morrell’s reflections with those of her feminist contemporaries. While Morrell, unlike Woolf, West, and Rhys, aligned evening gowns with artistic expression, her dresses’ construction and challenge to fashion’s emphasis on the new rendered them as alienating as West’s ink-stained petunia satin gown and Virginia Stephen’s green dress. The perceptual changes triggered by relocation—the affective bonds broken in a new setting—rendered Morrell’s gowns unstable and shameful.

Equally significant, Morrell understood her ideas and values on such occasions as parallel with her gowns: “All my own feelings and enthusiasms, like my dresses, I felt sure, would seem absurd and fantastic if I allowed them to be seen.”104 While Morrell could choose to conceal her passionate opinions—could forestall speech-acts that would isolate her from or set her in opposition to others—her dresses materialized decisions and commitments that she had made earlier and rendered her nonconformity visible. Morrell’s example illuminates the ways in which sartorial assemblages become disruptive when they reflect decisions made at an earlier time.105 Morrell might decide to remain silent, but she could not quiet, alter, or explain away a gown once she entered a room wearing it.