On the face of it, fancy dress has little in common with second-hand attire. Fancy dress is elective, worn by individuals who can afford to purchase or make an outfit for one occasion; secondhand clothing is the lot of those who cannot buy new garments even if they might be worn every day. Fancy dress is aspirational and often quite spectacular; secondhand garments save face and generally try to avoid notice. In moving from fancy dress to secondhand attire, we track down the social and economic scale.

When placed side by side, however, fancy dress and secondhand clothing collectively highlight the complex relationship between self and surface; they point to how persons understand who they are in relation to the things they wear. If representations of fancy dress interrogate the idea that costumes can transform the self—that one can aspire to, and occasionally reach, new heights through the cooperation of wearer and costume—representations of secondhand clothing highlight an inverse process. Used clothes challenge depth ontology by suggesting that self and surface are so connected that garments can detach from and mobilize aspects of the initial wearer’s identity. This relationship to materiality is troubling for characters who sell or donate their old clothes, but it poses the most significant problem for those who must accept or purchase castoffs.

Consider, for example, Rachel Ferguson’s middlebrow novel Alas, Poor Lady, which chronicles the diverging fortunes of five originally upper-middle-class sisters. The three who marry live out their days in relative comfort, but the two who do not drift into increasing poverty. Ferguson uses the arrival of the well-off sisters’ castoffs to reflect on the role of secondhand attire in Mary and Grace Scrimgeour’s social lives and sense of self. The two sisters discover that “the passed-on gown can influence social opportunity. It wasn’t likely, Mary pondered, that people would invariably recognize it in drawing-rooms of friends known also to the relations, but it was at least possible.”1 The verb “recognize” points to the close relationship between clothing and the initial owner; Ferguson identifies a dress not as a freestanding object but as belonging to the first person who wore it, even when on the body of another woman. The narrator suggests, moreover, that this realization only skims the surface of what secondhand attire does to Grace and Mary:

[N]either of the sisters got as far as the discovery that the wearing of other people’s frocks and coats also robs of personality: that with the putting of them on an actual dimming of individuality can set in.

The governess. The spinster. The Aunt Sallies of life and standbys of British serialized humour. Submerged in other people’s Garments.2

Alas, Poor Lady here suggests that secondhand attire, no matter how finely constructed, flattering, or well preserved, diminishes the personality and individuality of those who wear it. Moreover, a used coat or dress remains someone else’s garment; it “submerges” subsequent owners under the original owner’s impress. The two Scrimgeour sisters can neither lay claim to a culturally valued subjectivity—they are, as the narrator notes, “the governess” (Grace), “the spinster” (both sisters), and “Aunt Sallies”—nor even hold onto disparaged identities as they drown under their well-meaning sisters’ clothes. Fortunately, Mary and Grace remain largely unaware of what the castoffs they wear do to them.

Ferguson’s assessment of secondhand clothing was not idiosyncratic or unusual in the literature published between the wars. Drawing from a range of popular and experimental fiction, I argue that representations of secondhand clothing highlight an economy of subjectivity mediated through used garments. Secondhand attire provides the most direct example of human subjects reduced and diminished through garment actants—of those at the mercy of their clothes. Characters who donate or sell their clothing part with more than mere material; their things take part of the donors with them. And those who buy castoffs discover that they become auxiliary to the original owner of the attire as garments serialize characters. Representations of used garments figure a limited economy; the hierarchy between subject and object—the wearers of garments and the garments themselves—is leveled or at least realigned as humans become absorbed and influenced by their dress. Equally important, the secondhand garment troubles the boundaries between different owners and characters, presenting a dividual model of the person. Representations of castoffs point to a shared experience of the world, a shared interaction between people and objects, that works to unravel individualism.3

Examining the limited economy of secondhand clothing provides both a historical and a critical payoff. The trade in used clothes offers a window onto economic changes that threatened British social class between the wars; this optic sheds light on the profound role of things in constituting identity in the early twentieth century. As historian Ross McKibbin has documented, the British middle class generally spent double what the working class devoted to clothing, not only because the middle class had more disposable income but also because clothing represented a “different order of urgency,” since garments constructed class identity: “Suitable clothing was necessary both for the job and for social status: it was one of the last things that could be sacrificed.”4 Middle-class men and women who struggled in the difficult economic climate between the wars were driven to the used-clothing market to appear suitable. Dress historians have long asserted that Great Britain experienced a “democratization of dress” in the early twentieth century, but this argument ignores the booming trade in secondhand clothing. The “new poor”—a class of people economically disadvantaged after World War I—found themselves, often for the first time, having to resort to used clothes in order to maintain a respectable appearance. There were almost as many forms of and prices in the secondhand-clothing trade as there were in the sale of new garments; used garments could be worn and appreciated, but they had to be fully distanced from their original owners and in “like-new” condition to avoid the “submersion” that Ferguson’s novel outlines.

Representations of secondhand clothing also offer insight into stylistic and affective differences between middlebrow and modernist texts, which approach used garments with quite different emphases. Secondhand attire repeatedly receives comic treatment in cartoons in Punch and in fiction aimed at a middlebrow audience.5 Examples point to the difficulty of maintaining one’s identity when discarding used clothes: whether they are driven to raise money by finding a market for old garments or are encouraged to engage in acts of charity by donating castoffs, characters demonstrate that to give away clothing is to give away oneself (figuratively or literally). Readers and viewers are encouraged to laugh at characters in these texts, which use the comic mode to dispel the anxiety that the “new poor” felt about their sudden dependence on the secondhand-clothing trade. While middlebrow fiction suggests that used clothing was a component of many people’s wardrobes, it highlights the fact that the self is not self-contained but dependent on material and experiences that assemble it; identity, such texts demonstrate, can thus be partitioned and mobilized through material items that take unpredictable journeys away from the self.

In contrast to this comedic treatment, high-modernist representations of secondhand garments generally take on a tragic or militant cast. James Joyce, Jean Rhys, and Virginia Woolf figure selling, buying, and wearing used clothing as endangering individuality. Although they depict specific, narrow circumstances under which characters may purchase secondhand clothing without damage to their sense of self, they more often imply that the relational pressures of used garments cause the very borders of a character to break down. A dress one sells may take something of the original owner with it; a coat one buys may defamiliarize one’s own arms and torso. In these examples, it becomes unclear who or what is wearing whom. Characters feel that they cannot become or be themselves but are the auxiliaries of another self, a self distributed by a used garment.

Examined together, texts aimed at different reading publics express a shared sense of how secondhand clothing affects those who wear it and opposing attitudes about that impact. If everyone agreed that clothing can extract, circulate, and impose the initial wearer’s personality and identity on another, then they disagreed about how to regard that economy. Middlebrow characters—perhaps reflecting the tastes of their writers and readers—choose not to dwell on such assumptions. The comic representation of secondhand attire reflects a comparative degree of comfort with looking—and reading and writing—like others. Modernist characters and narrators, in contrast, regard the sharing of clothes as an unbearable imposition, one that particularly forces artist-figures to be less true to themselves and their art. The alignment of attitudes between reading publics and sartorial style—an alignment that, as I will demonstrate, does not apply to other secondhand objects—suggests that used attire, however prosaic, became a site of conflict between persons and (some of) the things they wore.

The New Poor and Old Clothes: Modern Experiences of the Secondhand

Advertisements for secondhand-clothing dealers haunt the margins of fashion periodicals of the 1920s and 1930s. Issues of Vogue and Eve reported on the latest Paris models, but small notices reminded readers that many women came into contact with designers like Coco Chanel and Paul Poiret—as well as less august names—only after other women had worn the garments and decided to sell them. Scholarship on fashion in modernity generally focuses on the rise of industrialization and mass-production and the emergence of designer brands; Beverly Lemire speaks for many scholars when she asserts that secondhand apparel was socially acceptable and widely worn only before industrialization made cheaper, ready-made garments available.6 Stanley Chapman, for his part, asserts that by 1860, 80 percent of the population of Britain purchased ready-made clothing.7 Such arguments, which focus on the nineteenth century, occlude the ongoing demand for secondhand merchandise that persisted well into the twentieth century, when preindustrial forms of the clothing trade quietly persevered at the edges of modernization.

Although middle-and upper-class individuals wore secondhand clothes less frequently after nineteenth-century advances in mass-production lowered the cost of textiles and ready-to-wear clothing, secondhand-garment stores remained a fixture of many cities and neighborhoods (figure 4.1). They functioned not only as a source of inexpensive clothing but also as an opportunity for moralizing. For example, in his essay “The Londoner Out and at Home,” George R. Sims observes that “second-hand clothes shops abound all over the Metropolis, and they are usually stocked to the full limit of their space. If the faded finery of a second-hand clothes shop could speak, it could tell many a tale of the great human comedy, and alas! Of the great human tragedy also.”8 As Sims’s comments make plain, individual garments and the volume in each shop were thought to bear witness to the lives of people who had long abandoned their clothing. Such figuration seems the privilege of a writer who does not himself patronize this type of establishment, but the educated classes could treat the “faded finery” in used-clothing shops only with philosophical distance before 1914.

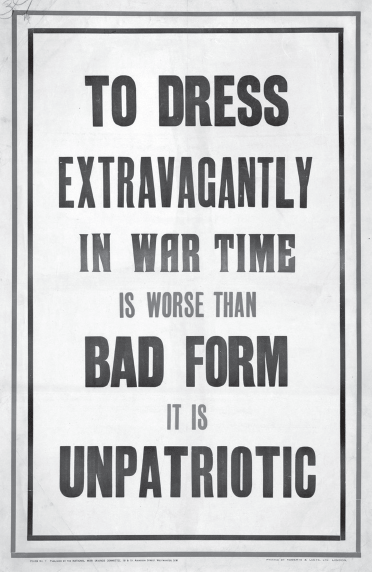

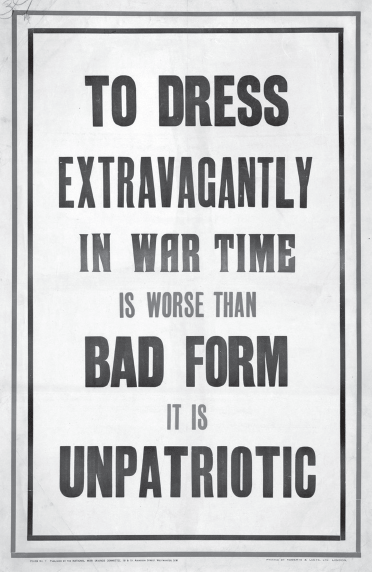

The secondhand-clothing trade resurged during World War I. Between 1914 and 1918, a popular means of raising money for charity involved holding fairs or bazaars where working-class individuals could purchase designer clothing donated by aristocrats and even royalty.9 As the war lingered on, the National War Savings Committee urged British citizens to limit their clothing budgets and to donate what they might have spent on new clothes to war bonds and loans (figure 4.2).

Cartoons in Punch suggest that complying with such directives led individuals to wear outmoded, and perhaps secondhand, clothing; it was “rotten bad form” to wear “quite new” garments, although one suspects that few people sported visible patches or crushed top hats (figure 4.3). This image reflects, perhaps, hyperbole on behalf of the cartoonist and magazine, but other periodicals quoted society women who claimed to have turned their back on fashion for the duration of the conflict.10 During a national crisis, wearing used clothing could be made palatable because it was patriotic.

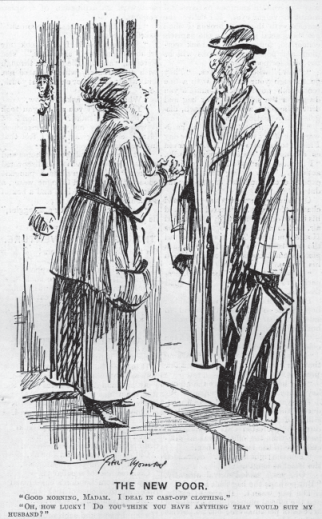

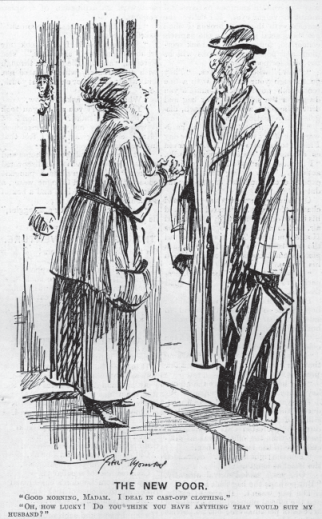

While consumers hoped for a return to normal patterns of consumption after the war, a class self-identified as the “new poor” found that it could no longer afford a prewar standard of living. According to Simon Gunn and Rachel Bell, postwar “newspapers were full of stories of the ‘new poor,’ of well-to-do families who had fallen on hard times caused by inflation and the effects of post-war economic dislocation.”11 In January 1920, the Queen, a women’s periodical aimed at the upper class, described this category as “those classes of education and refinement who have to meet the enormous increases in the cost of the barest necessities with steadily decreasing incomes, often enough on incomes reduced to the vanishing point by the loss of husband and father, or heavily encumbered, having the erstwhile breadwinner ill or disabled by wounds.”12 The Lady, for its part, exhorted its readers to adjust to the new economic situation with good grace: “In these days of increasing expenditure and diminishing income it behooves us—the New Poor—to adapt ourselves to altered circumstances.”13 Such adaptation included purchasing secondhand clothing, as a cartoon titled “The New Poor” makes clear (figure 4.4). The man at the door has come to purchase castoff clothing from the type of household that would have sold such garments in the past. The woman responds, however, with an undisguised eagerness: “Oh, how lucky! Do you think you have anything that would suit my husband?” Although the dealer’s face registers some surprise, the cartoon suggests that the declassing of many people had shifted previous patterns of consumption and that readers of Punch would recognize the situation it depicts.

Advertisements in British periodicals indicate the extent of demand for secondhand clothing in the 1920s and 1930s as well as the lines along which such businesses were run. The sheer number of notices for individual dealers shows either that there were more people getting into the trade or that there was more demand for their goods (or both); while the Late May 1924 issue of Vogue has thirteen ads for used-clothing dealers,14 the October 31, 1928, issue contains twenty-six.15 The doubling in number of these advertisements was accompanied by an increasing variety of secondhand-clothes dealers. Some firms worked entirely by post and offered to send “all correspondence under plain envelope” so that a client’s neighbors would not discover the sources of his or her “new” attire.16 Other dealers operated “dress agencies,” consignment or secondhand shops that were directed at declassed consumers; they included Patricia Carr, who promoted “a new Dress Agency run on original lines for the ‘new poor,’ ”17 and “The New Poor and Molly Strong Dress Agency, run by gentlewomen in the interests of gentlewomen.”18 Vogue itself, while continuing to feature new clothing and designs in its articles and illustrations, appears to have acknowledged the need for such businesses, touting “The Shoppers’ and Buyers’ Guide” as a place to find buyers for (if not sellers of) castoff clothing: “Here, when you are tired of your clothes and yet can’t afford to give them away, is the name of a discreet firm who will buy them from you.”19 Whether a reader chose to patronize a trader who did business by mail order or a dealer who owned a physical shop, Vogue promised discretion and anonymity, qualities that underline the potentially shaming nature of the transaction. The “new poor,” such advertising suggests, were not habituated to buying secondhand garments, and if necessity compelled them to do so, they would seek to put distance between themselves, the previous owners of the clothing they purchased, and even the traders who dealt in castoff clothing.20

While little information about secondhand-clothing dealers has survived—as Lemire writes, the secondhand trade was “largely invisible” and left “few records”21—the archives of Robina Wallis, who ran such a business by post between 1926 and 1959, indicate how British consumers felt about buying used clothing.22 Wallis inherited the business from her mother and moved it from Devon to Cornwall. After building her clientele through advertisements in the Lady, a weekly women’s magazine, she sent and received garments from as far north as Scotland to the southern coast of England. Wallis acquired clothing from society women, including the Duchess of Roxburghe and Lady Victor Paget, as well as from women in more modest circumstances. Some of Wallis’s clients bought and sold apparel, which suggests that certain garments made their way through multiple owners over time.

Many letters from Wallis’s customers demonstrate that women who patronized secondhand-clothing dealers expected and received garments that were modish, in good condition, and, to all outward appearance “new.” For example, Barbara Armstrong wrote to request a “smart black evening frock in either lace or georgette” and asserted, “I want a really good model.”23 Armstrong evidently got precisely what she wanted, later writing that the black lace evening dress “was most successful.”24 In addition to satisfying specific requests, Wallis received correspondence that praised her merchandise in general terms. Mrs. Alderson Archer, who was evidently recovering from an illness, confessed that “I feel clothes are a bit of a nuisance when one isn’t feeling well, but, if one gets just what one wants, it certainly does cheer one up.”25 Although Archer’s praise is conditional—“if one gets just what one wants”—her letter suggests that she thought it possible to acquire such garments on the secondhand market. These letters, and others like them in the archive, demonstrate that many customers were open to and satisfied with the clothes they bought secondhand. If such purchases were necessitated by economic circumstances and thus not a purely free choice (as they can be in today’s vintage-clothing market), the writers frame their purchases as flattering and emotionally fulfilling.

At other times, however, Wallis’s clientele wrote to express their frustration with secondhand garments that she had sent on approval. Their complaints indicate that used clothes were often unappealing or in poor condition, bearing traces of the first owner’s inadequate taste or insufficient care. A. Bailey, writing from lower Hampshire, thanked Wallis for a parcel but rejected some of the items it contained: “The jumper [sweater] is not as smart as I wanted. I wonder if you have another one. I am sorry to give you so much trouble but I wanted a very nice one.”26 Bailey’s desire for something more fashionable—by “smart,” she meant highly stylish—points to an obvious condition of purchasing secondhand garments: because the original owners had generally worn them for at least one season, castoffs were unlikely to be in the latest styles and served as a reminder that someone else had enjoyed them first. Other women did not want the most eye-catching modes available—G. Birch returned a sequined coat in 1935, as it was “a little too striking for me”27—because such styles were suitable for only the kind of woman who owned a lot of clothes and could wear each piece infrequently. Thus whether a used garment was unfashionable or too stylish, it reminded clients like Bailey and Birch that another woman had worn it earlier, and often in very different financial circumstances.

The letters in the Wallis archive also make it plain that many secondhand garments bore traces of the original owner.28 Lesley Paul wrote to return an ensemble because of its condition: “[T]he coat and skirt is just rather well worn for what I want as I am invited to a very smart ‘house party’ in August. It includes some of my relations who would know at once that it was not new as they see me every day!”29 Paul, who wanted to keep her purchase of secondhand garments secret from even close “relations,” could wear only clothing that looked unworn. Other buyers could not afford to be so choosy. A. Linton, who wrote from Edinburgh, used condition to negotiate more favorable terms from Wallis. In an undated letter, she noted that “the tweed suit fits well, but it has several large stains on the front of the skirt—perhaps you didn’t notice them—I would give £3 for it.”30 These letters delineate the range of clients who purchased secondhand clothes. Some buyers insisted on “like-new” items, while others were willing to take flawed merchandise, provided that it was inexpensive. Perhaps Linton thought that she could remove the stains from the skirt, but it is also possible that she needed the suit so much that she would live with its imperfections. If so, the “large stains” would become an ongoing sign of the bodily experiences of another woman and would visually fix Linton in the class system.

Buying used clothing was thus a strategy that a range of people used to supplement or fill a wardrobe. It allowed comparatively well-off women to purchase designer garments for a fraction of the items’ original cost; it also enabled poor women to dress themselves appropriately on a small budget.31 And yet, the secondhand-garment market was replete with frustrations. An undated letter from M. A. Smith lamented, “The suit fits nicely but the color is too light and makes me look so big. I was very disappointed.”32 Smith’s letter implies that the suit’s original owner lacked taste, since the color was inappropriate for women of their size; her complaint bespeaks the frustration that Smith experienced at having to work within the parameters of another woman’s history and choices. Although many women were satisfied with their purchases—the letters from Armstrong and Archer are not isolated—the secondhand market required patience, flexibility, and negotiation in order to achieve that satisfaction. And it was replete with reminders that other consumers were more fortunate.

The Wallis archive, and the many advertisements for secondhand-clothing shops and dealers published in periodicals between the wars, thus serves to complicate the impression of commentators in the period (and later dress historians) that dress was democratized in the first half of the twentieth century. In 1929, the Encyclopaedia Britannica, for example, confidently opined:

Class distinctions, in so far as they are indicated by dress, have disappeared. It is not easy to detect differences of degree among the great bulk of the people. Partly this is due to the spread of democratic ideas and institutions. Cheap means of transport, for example, bring all classes together. The intermixing produces similarity in style of attire. Partly, also, the cause is economic. There are more wage-earners, at better rates of pay. There has been a tremendous increase in the number of women wage-earners. Every one has more money available to spend on dress.33

This assessment that “every one” could afford to spend money on clothing was widespread. Twenty-three years later, C. Willett Cunnington similarly opined that “fashion has now become a democratic expression instead of being, as it once was, the exclusive symbol of the upper class outlook.”34 These kinds of assertions are celebratory, and they offer an appealing account of period fashion (and material culture more generally) as free from the taint of class, which characterized dress in earlier eras.

The problem, however, is that such accounts are wrong. While it is true that, as Gilles Lipovetsky argues, Chanel and other designers popularized styles that made it “no longer obligatory for the upper classes to dress with ostentatious luxury,” such “dressing down” did little to help those on the other end of the economic scale “dress up.”35 As Christopher Breward observes, “Few even in the 1930s could afford the new clothes in the shops.”36 Secondhand dealers provided options to buyers for whom new clothing was out of reach, but the very need for such businesses—and the very fact that they had to operate discreetly—reinforced class distinctions. Purchasing items from Wallis was not “a democratic expression” but a reminder that the buyer’s social and sartorial aspirations were at odds with her economic class. Wearing a skirt with stains, returning a suit because it was well worn or in an unflattering shade, and rejecting a sweater that was “not as smart as [the purchaser] wanted” are all experiences that confronted the new (and old) poor, with their limited access to appropriate and attractive dress. A woman might hope for a garment that was clean and new, but she might be able to buy only an item marked by the initial owner. Even if observers thought that Wallis’s clients were well turned out, the individuals wearing secondhand attire knew that their appearance was achieved by dint of a discreet dealer, a modicum of luck, and hard bargaining. The secondhand-clothing market thus serves to trouble narratives about the triumph of mass-production in the twentieth century.37

The range of real-life experiences with secondhand attire that I have detailed is replicated in period cartoons, fiction, and nonfiction. Occasionally, the acquisition of used clothing proceeds smoothly, particularly if characters are able to purchase such garments through the distancing medium of secondhand shops. Notably, however, British literature emphasizes the proximity inculcated through castoffs and the concern that secondhand clothes enchain wearers: garments take something away from those who discard them and impinge on the selfhood of subsequent wearers. Writers align feelings of self-deprecation, shame, and even anger with a category of clothing that has, seemingly, a life of its own—or, rather, a life siphoned off that of the first purchaser. They suggest that castoffs acquire something of the original owners’ personality and distribute that personhood, a function that limits subsequent wearers’ ability to own them fully. Secondhand garments thus render class materially as well as trouble the boundaries of the body and the individual, locating characters in hierarchical relationship with one another and radically expanding the notion of embodiment. By enchaining wearers to initial owners—individuals who cannot control the movement of their distributed selves—secondhand garments imply that buyers and sellers are diminished by contact with garments that appropriate power from the human in a zero-sum game.

Popular Culture’s Comedies

At the turn of the twentieth century, secondhand clothes made an occasional appearance in the fiction published in middlebrow magazines. Elizabeth C. Pilkington’s story “Milly’s Old Lavender Gown” serves as an early exemplar of a subject that would become increasingly common after World War I when, as I have documented, many people were driven to purchase secondhand garments for the first time. The short piece begins with the title character’s lament that her family must sell their old clothes because “we can’t afford to give them.”38 Milly’s sister exhorts the family members to discard everything they can, so Milly reluctantly goes to her wardrobe to retrieve a cotton dress that “seemed to shrink into the background.”39 Pilkington here animates the frock, which appears to “shrink” and thus reflects Milly’s sentimental attachment to a dress that she had worn during a brief flirtation abroad. Divesting herself of the dress, in Milly’s view, means putting aside pleasurable memories as well as her desire for the future; her clothes take with them “my treasured hopes—they and my old lavender gown find a grave in Mrs. Briggs’s big black bag!”40

Readers of the Windsor, in which this story was published, could rest assured, however, that the “grave” would not entirely consume Milly’s dress or dreams. Like many publications of its type, the magazine offered fiction with happy endings, and the plot of Pilkington’s tale turns when the gown is purchased by a servant in the household of Milly’s former beau:

[W]ho was this coming down the plantation towards him but the veritable “Sweet Lavender” herself!—lissom figure, golden-brown hair, deep blue eyes, and even the same lavender gown, butterflies and all.

He stood as one petrified: but as the figure drew nearer the golden hair assumed a carroty hue…and there stood before him a respectful-looking woman-servant from the house.41

The dress has the power to deceive the eyes, if only at a distance; although the story painstakingly explains that the servant does not look like Milly, the frock can evoke her appearance even when worn by another. As a result of this apparition, Rupert Courtenay-Leigh locates Milly and proposes marriage. In the final paragraph, the protagonist plans similar unions for her sisters, and her fiancé predicts, “No doubt my wife will prove a wonderful maker of marriages when even her old gown turned matchmaker.”42 “Milly’s Old Lavender Gown” thus redeems the title character’s inadequate means, loneliness, and unwilling sale of her dress through the conceit that the garment distributes her identity—her persona—and bears witness to her existence in a remote location.43 The gown thus emerges as the most important “character” in the story; it becomes a shadow self that advances the character’s hopes and the story’s narrative. Pilkington’s gentle animation of the dress serves to palliate Milly’s involvement in an economic exchange that she would prefer to avoid; participation in the secondhand-clothing trade could be redeemed through the conventions of coincidence and the romance plot.

This comedic understanding of used garments is echoed in many other works read by middlebrow publics between the wars. These texts not only reflect an era when an increasing number of British citizens bought and sold castoffs but also, more importantly, shape that experience through a positive tone that emerges in sharp contrast to that of contemporary modernist fiction. Middlebrow novels and cartoons depict the need to sell (and, occasionally, buy) castoff clothing as humorous, an example of the shared predicament in which the “new poor” found themselves. While the taint of the secondhand market threatens characters’ social status and self-worth, and garments are occasionally animated, optimism colors representations of used garb. In part, readers are encouraged to position themselves with the creators of such portrayals, who can clearly see what their characters do wrong. The repeated humor directed at secondhand-clothing exchange, however, reveals a strategy to defuse the anxiety and shame of buying old garments at a time when the new was at a premium. I trace representations of secondhand clothing in popular texts from the most intimate, casual exchanges (such as purchasing or receiving an item from a friend) through sellers and buyers of castoffs in professional markets. While sellers come in for a greater degree of ribbing than buyers—middlebrow texts were more willing to mock the upper and middle classes than those on the bottom rung of the economic ladder—these accounts depict the secondhand garment’s power to tarnish the subject who exchanges it, to enchain individuals in a relationship through the agency of an object. The one exception is historical fiction, which illuminates why the modern castoff was so troubling.

Writers direct some of the most cutting humor at middle-class characters who procure used clothes from friends, the most intimate form of acquisition. In Molly Keane’s Devoted Ladies, a middlebrow novel devoted to romantic intrigues in an Anglo-Irish hunting set, a character ignominiously nicknamed “Piggy” bewails the fate of a “black Patou dress Joan gave me, rather lovely, cut with a terrible deep V at the back and that marvelous swathed line.”44 The name Jean Patou, a French designer popular in both Great Britain and the United States in the 1920s and 1930s, was associated with elegance, expense, and high style. But Piggy’s dressmaker, whom she charged with remaking the three-year-old gown so that it would fit her, had unwittingly destroyed it. Piggy and the seamstress “sought to recapture the infernal subtleties of Mr. Patou’s three-year-old inspiration. Their minds in a fog, their hands cold, their mouths full of pins, to what strange shapes had they tortured this hellish garment before despair had settled in on them and they sought to put it back as it was before and could not.”45 Instead of remaking the dress into an innovative new garment or adapting Patou’s dated vision, the dressmaker and Piggy find their time, emotional energy, and labor wasted by the “hellish garment” they mangle through their efforts. This dress remains “the black dress she [Joan] wore at hunt balls three years ago” and cannot be made to fit Piggy.46 In fact, this may have been Joan’s intention, as the character is repeatedly represented as using her “friends”: the Patou dress thus works on behalf of Joan in remaining stubbornly resistant to Piggy’s appropriation.

Keane’s characters are largely deaf to the unflattering ways in which trade in secondhand garments positions them, but cartoons published in Punch in the 1920s depict characters as shamefully exposed by their attempts to sell or donate their clothes. In part, the humor hinges on the original owner’s overvaluation of his or her used clothing, as in an August 19, 1925, cartoon in which a “lady” tries to sell a “real golf-coat.” The old-clothes man responds, “Is it a nine or eighteen moth-’ole, or ’aven’t yer counted ’em?”47 The dumbfounded look on the lady’s face expresses her shock and surprise at this assessment, and readers are expected to chuckle not only at the buyer’s clever wordplay but at the would-be seller’s conviction that her castoff is particularly valuable. Although this assumption is never articulated, this cartoon relies on the seller’s presence in the garment—the fact that the coat works as a component of the owner’s identity.48 In offering a “real golf-coat” to the wardrobe dealer without acknowledging its condition, this seller has opened herself to mockery and laughter. Such a cartoon would be funny, one suspects, only to readers who would pride themselves on never making a similar mistake.

Other Punch cartoons similarly suggest that owners are often unpleasantly surprised by the value of their castoffs—or by precisely why they are valued. A cartoon from 1924 depicts a “Grateful recipient” in the act of taking used boots from the “Vicar’s wife,” a scenario that presents a seemingly ordinary charitable act. In this cartoon, however, the donor receives not only thanks but a shaming reference to her size as the recipient states, “My missus ’as such long feet, an’ yours are the only boots I can get to fit ’er with any comfort.”49 The surprise on the lady’s face indicates that she has opened herself to an indirect insult—a comment on her large feet—through her act of charity. Here, donating a castoff serves to broadcast an unflattering aspect of the donor’s physique that she would doubtless prefer to keep private; once the boots are in the hands of the recipient, they distribute biological facts about the donor’s body. This cartoon suggests that one peril of engaging in the secondhand market is that the donor gives herself, as well as an object, away. Proximity of donor and recipient, or of buyer and seller, generates Punch’s humor, which repeatedly depicts the secondhand garment as tarnishing the first owner with unintended consequences as it changes hands.

These examples, albeit humorous, point to one of the reasons that the “new poor” may have preferred to deal with the secondhand market through the post. Traders like Robina Wallis are never the subject of Punch’s brand of comedy, in large part because the distance between buyer and seller provided a cushion of privacy that protected the original owner of garments. Distribute your garments over enough distance, Wallis’s clients may have assumed, and they will never come back to haunt you. But middlebrow fiction still directs humor at protagonists’ transactions with professional secondhand-clothing traders, which open characters to judgment and embarrassment. E. M. Delafield’s Diary of a Provincial Lady, for example, represents the title character’s attempts to rectify a negative bank balance by selling her old clothes: “Financial situation very low indeed, and must positively take steps to send assortment of old clothes to second-hand dealer for disposal.” She later

collect[s] major portion of my wardrobe and dispatch to address mentioned in advertisement pages of Time and Tide as prepared to pay Highest Prices for Outworn Garments, cheque by return. Have gloomy foreboding that six penny stamps will more adequately represent value of my contribution, and am thereby impelled to add Robert’s old shooting-coat, mackintosh dating from 1907, and least reputable woolen sweater.50

The lady raids not only her own closet but also that of her husband in an attempt to raise money. Unlike the donors in the Punch cartoons, Delafield’s protagonist is well aware of the probable low value of her castoffs. Such savvy does not, however, prevent disappointment: “Rather inadequate Postal Order arrives, together with white tennis coat trimmed with rabbit, which—says accompanying letter—is returned as unsalable. Should like to know why.”51 Selling her clothes to a professional trader cannot help the lady realize the sums she wants, and even distance cannot prevent a mild form of insult. Her family’s castoffs—reflections, at a remove, of her family’s choices and taste—are remunerated inadequately, making the lady feel more than usually inadequate as well. The dealer’s rejection also helps to underline the lady’s folly in purchasing a sport jacket—a tennis coat—trimmed with an impractical material. The judgment that this item is “unsalable” reflects badly on the lady’s discernment, and it positions her as less a “fashion victim”—a phrase that suggests that a wearer is at the mercy of bad design—than a victim of her earlier decision. The jacket will linger in her closet, an unworn reminder of this embarrassing episode.

Delafield’s novel reveals and reinforces a set of middlebrow assumptions about the “new poor” and the secondhand trade: this class may look fashionable even as individuals struggle to make ends meet; secondhand dealers never pay sellers what they believe their garments are worth; and to sell one’s clothes is to open oneself to insult, though working with a professional trader at a distance serves to mitigate the sting. The lady learns that discarding garments is a complicated act, serving as it does to circulate the original owner’s economic struggles, physical shortcomings, or fashion sense around the country through the mobility of attire. Discarding clothing puts characters’ identities, as well as their castoffs, on the market; in choosing to sell items with which they have had intimate contact, characters in middlebrow fiction distribute aspects of themselves beyond the body boundary. In contrast to the fancy-dress costume, which offers a few fictional characters in the period the opportunity to enjoy additional selves, the secondhand garment diminishes the individual who originally owned it by absorbing the self and traveling uncontrollable paths. Sellers may be slightly richer for having sold old clothes, but they pay for their small profits—or acts of charity—through a reduced sense of confidence, control, and self.

Representations of working-class recipients of secondhand clothing are relatively rare in popular fiction, doubtless because the demand for castoffs reminded readers of economic disparities that were difficult to treat lightly. Flora Thompson’s Lark Rise (1939), the first book in her immensely popular Lark Rise to Candleford trilogy, serves as an exception. The setting for Thompson’s novel—Oxfordshire in the 1880s and 1890s—helped to assuage the difficulties of this subject; her book offers a nostalgic treatment of rural working-class life, which had vanished by the time Lark Rise was published.52 Because of this historical distance, and because her characters are members of a respectable, rural working class, Thompson could treat the castoff’s power to enchain wearers positively; in contrast to others writing in the 1920s and 1930s, she constructs secondhand clothing as distributing original owners and thus helping families and communities to cohere.

Thompson’s characters rely on secondhand garments, which they receive from “daughters, sisters, and aunts away in service, who all sent parcels, not only of their own clothes, but also of those they could beg from their mistresses.”53 Like the two sisters in Rachel Ferguson’s Alas, Poor Lady, which was published just two years before Lark Rise, Thompson’s characters receive castoffs from family members, garments that come from intimate contacts and are identified with the donors. The correspondence between the two novels ends there, however: unlike Ferguson’s protagonists, Thompson’s characters desire and even prefer familial hand-me-downs to clothes that come from elsewhere:

The daughter’s or other kinswoman’s clothes were sure to be appreciated, for they had usually already been seen and admired when the girl was at home for her holiday, and had indeed helped to set the standard of what was worn. The garments bestowed by the mistress were unfamiliar and often somewhat in advance of the hamlet vogue, and so were often rejected for personal wear as “a bit queer” and cut down for the children.54

This passage identifies two factors that shape the hamlet’s opinion of what used clothing is wearable. It demonstrates, as Lark Rise notes elsewhere, that the rural community “had a fashion of its own, a year or two behind outside standards.”55 This “lag” partially accounts for the difference between Lark Rise and Alas, Poor Lady, in which the sisters receive hand-me-downs in 1920s London. If one operates outside or slightly behind the fashion system, Thompson’s novel suggests, secondhand attire is acceptable and even welcome. More important, however, is the novel’s assertion that the association of a dress or skirt with a specific kinswoman makes that item of clothing most desirable. The relative’s contact with the garment, and her contact with her family while wearing that garment, makes it doubly familiar: it is intimately associated with a family member and previously known. In wearing a sister’s, a daughter’s, or another relative’s clothes, the characters in Lark Rise link themselves to a relation working in service (generally in a larger town or city); if others in the hamlet recognize a dress as secondhand, it serves as a sign of enchainment with a successful family member—someone who is employed, helping to support the family back home, and a tastemaker for the community.

Such garments remained familiar—associated with the initial wearer—throughout their useful lives. In Candleford Green (1943), Laura dresses “for the Church Social in the cream nun’s veiling frock in which she had been confirmed and in which her cousins Molly and Nellie had been confirmed before her.”56 The character is untroubled by the dress’s rich history, by the manner in which it links her with her cousins, because she has no other means to acquire clothing. Her family, which is among “those too poor to buy at all at first-hand,”57 must accept what they receive. Because Thompson sets her fiction in the late nineteenth century, and because all her characters come from the rural working class, she can depict secondhand clothing in a manner quite different from that of her contemporaries. Indeed, Lark Rise throws into relief some reasons that castoffs are so much more troubling for characters in other middlebrow novels. Ferguson’s protagonists, who resent having to wear their sisters’ old clothing, “had been used to [their] own original garments and the privacy and self-respect of that which is made for [their] own body and no one else’s.”58 Thompson’s characters have not had that experience—they can never regard clothing as the possession of the individual and not the family. As a result, the fictional inhabitants of Lark Rise welcome clothing that was made for and worn by other bodies.

Thompson’s work focuses on—indeed, celebrates—a historical moment when fashion was the province of cities and when the rural poor could not expect to own many new garments. Her novels do not always depict secondhand clothing in a positive light, however; they suggest that purchasing used garments from a shop—clothes that have no familiar associations—sets up characters for humiliation. Laura and her mother watch as one young woman leaves the hamlet to go into service, wearing

a bright blue, poplin frock which had been bought at the secondhand clothes shop in the town—a frock made in the extreme fashion of three years before, but by that time ridiculously obsolete. Laura’s mother, foreseeing the impression it would make at the journey’s end, shook her head and clicked her tongue and said, “Why ever couldn’t they spend the money on a bit of good navy serge!” But they, poor innocents, were delighted with it.59

Thompson does not depict the young woman’s shaming when she arrives at her destination, and the narrator’s voice offers sympathy to the “innocent” character who purchased a completely outmoded and loud secondhand garment. While this young woman would likely be perceived as poor and rustic no matter what she wore, a castoff from a family member in service would not have been made in “the extreme fashion,” nor would it be quite so outmoded. Thompson’s novel thus represents secondhand clothes from family members as safer, more appropriate attire than used clothes from a shop; if the former distribute the personae of relations and link each person who wears them to the donor, the latter are alien and isolating.

Thompson’s treatment of secondhand clothing thus serves to sharpen the precise anxieties expressed in other middlebrow works. If novels by Ferguson, Keane, and Delafield; cartoons published in Punch; and other texts depict sellers and buyers of used garments as embarrassed by items that absorb and distribute personhood, such an experience is produced through historical, geographical, and class conditions that do not pertain to Thompson’s characters. By setting Lark Rise at the end of the nineteenth century, and by focusing on a way of life long gone at the time she was writing, Thompson could figure secondhand clothing as one of the forms of intimate exchange that supported and bettered life in England’s rural villages.60 In the 1920s and 1930s, however, middle- and upper-class British citizens in towns and cities had come to expect to wear new clothing; the ideal had become, in Ferguson’s words, clothing purchased or “made for [one’s] own body and no one else’s.”61 Individuals who found this ideal impossible to attain and resorted to the secondhand market were repeatedly reminded that their financial and social position ought to be better than it was. In the historical window between the wars, secondhand clothes emerged as a material resister of the gap between expectations and economic reality: no wonder sellers saw the need to profit from their old clothes as giving themselves away; and no wonder buyers regarded themselves as imprinted by garments made for, and shaped by, the bodies of others comparatively more privileged.

Varied as they are, popular representations of the secondhand-clothing trade share one important quality: although the type and texture of their treatment varies, they regard the exchange of castoffs lightly. Characters may be surprised or briefly discomfited to discover that they have “given themselves away” in selling or donating used clothing, but the garments’ ability to absorb aspects of the original owners—and to distribute their identities in ways that elude prediction or control—does not do extensive damage. Work written for a highbrow audience, in contrast, casts the used garment as far more sinister. These texts suggest that in wearing secondhand clothing, the human can be serialized—that castoffs create asymmetrical relationships as people are diluted by garments that either take something of the self with them or muddle the boundaries between different individuals. Secondhand clothing can render individuals secondary and subordinate to the clothes they once wore or that necessity requires them to put on.

High Modernism and the Problem of Proximity

At the same time the middlebrow work I have discussed was published, high modernists offered quite different visions of what it meant to buy and sell used clothing. Their texts, which often focus on protagonists struggling to establish a unique identity in a resistant social sphere, occasionally represent used apparel as acceptable, particularly when it can be purchased through the distancing medium of a shop. More often, however, they treat secondhand garments as imperiling individualism. They repeatedly suggest that characters cannot maintain their selves under the pressure of clothes that belong to known others; they also express the suspicion that the human might be auxiliary to the object world, worn and manipulated by purportedly inert material.62 Used clothing emerges as so imbued with the bodies and selves with which it has contact that secondhand boots, pants, and dresses create a dividual human, one characterized by a compromised—because communal—self. If Flora Thompson’s late Victorian English laborers take a communal and familial identification as primary, her modernist contemporaries wrote characters who fervently desire an individual relationship to clothing—indeed, who want to exempt themselves from all manner of serial relationships.

This is not to say that modernist texts never see the humor in the necessity to wear used clothing. Ulysses, for example, deploys secondhand garb to have great fun at a minor character’s expense. In “Sirens,” Father Cowley and Ben Dollard remember that Molly Bloom used to run a secondhand-clothing business.63 They call it “the other business,” which Don Gifford glosses as “Molly and Bloom collected and sold secondhand clothes and theatrical costumes.”64 The fact that Cowley and Dollard do not explicitly identify the trade suggests that there is something disreputable in selling secondhand clothes. Such disrespect could stem from the fact that Molly works in a culture that naturalizes women’s domestic, but not commercial, labor or from the long historical association between Jewish men and women and the old-clothes trade.65 The novel thus briefly references the Blooms’ former business as a sign of ethnic difference and the gender distortions created by colonial poverty.

Instead of focusing on the business, however, characters in Ulysses are much more preoccupied with one specific occasion related to the Blooms’ secondhand stock. Dollard says he “remember[s] those tight trousers,”66 a memory that Bloom later fills out: “Ben Dollard’s famous. Night he ran round to us to borrow a dress suit for that concert. Trousers tight as a drum on him. Musical porkers. Molly did laugh when he went out. Threw herself back across the bed, screaming, kicking. With all his belongings on show. O, saints above, I’m drenched! O, the women in the front row! O, I never laughed so many!”67 In “Penelope,” Molly too recalls “Ben Dollard…the night he borrowed the swallowtail to sing out of in Holles street squeezed and squashed into them and grinning all over his big Dolly face like a wellwhipped childs botty didn’t he look a balmy bullocks sure enough that must have been a spectacle on the stage.”68 All three characters recollect Dollard’s bodily exposure in a pair of tight secondhand pants. Bloom and Molly remember that the trousers emphasized Dollard’s genitals as well as his girth; the poor fit resulted in an unwitting and comic sexual display, and the high-cultural spectacle of musical performance was transformed into an obscene exhibition facilitated by secondhand trousers. Although none of the characters identifies the original owner of the suit, and Dollard does not experience it as a vector for the distributed persona of someone else, the trousers draw attention to the role of clothing, which constitutes individuals as artists, in performance. Dollard’s pants do not fail in the spectacular ways that other manmade objects do, but they become resistant things through a poor fit that denaturalizes his identity as a purveyor of high-cultural entertainment. Since the pants, in Molly’s view, will be the most obvious and entertaining aspect of “Dollard’s” performance, he becomes subordinate to the dress suit he borrows.

While Joyce deploys secondhand trousers to generate humor at the expense of a minor character in Ulysses, used clothing represents a significant (and decidedly uncomic) threat to Stephen Dedalus. He wears used clothes in both A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Ulysses, and differences among the examples from these texts clarify the precise manner in which particular castoffs impinge on the self. In Portrait of the Artist, secondhand clothing is intimately tied to Stephen’s escape from Ireland. The end of the novel documents his acquisition of “new secondhand clothes” as part of his preparation for life in Paris: “April 26. Mother is putting my new secondhand clothes in order. She prays now, she says, that I may learn in my own life and away from home and friends what the heart is and what it feels. Amen. So be it. Welcome O life! I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.”69 Although Stephen, who has by this point assumed his position as the novel’s first-person narrator, uses the adjective “new” to identify the clothes that will help his body fly by the nets of family, nation, and Church, a reader quickly detects the oxymoron in the phrase “new secondhand,” which gestures toward Stephen’s poverty and qualifies the preparations for his escape.70 Portrait of the Artist uses his secondhand attire to code an economic problem, but it is important to note that only the reader, and not Joyce’s character, regards the garb in this light. Stephen records the acquisition of the garments in a neutral manner, and this detail is placed in close proximity to his highly emotional final declarations, including “Welcome O life!”71 and “Old Father, old artificer, stand me now and ever in good stead.”72 Stephen’s “new secondhand clothes” are thus not separate from, but associated with, his artistic ambitions and pursuit of exile.

Portrait of the Artist provides no other details about the secondhand garments that Stephen takes on his journey, but Ulysses opens with the journey ended ignominiously and Stephen, once again, in secondhand togs. In his conversation with Buck Mulligan on the roof of the Martello tower, Buck asks Stephen, “How are the secondhand breeks [trousers]?” to which Stephen simply responds, “They fit well enough.”73 Buck then continues:

—The mockery of it, he said contentedly, secondleg they should be. God knows what poxy blowsy left them off. I have a lovely pair with a hair stripe, grey. You’ll look spiffing in them. I’m not joking, Kinch. You look damn well when you’re dressed.

—Thanks, Stephen said. I can’t wear them if they are grey.

—He can’t wear them, Buck Mulligan told his face in the mirror. Etiquette is etiquette. He kills his mother but he can’t wear grey trousers.74

This passage signals Stephen’s poverty and respect for the mourning rituals of the period; as I discussed in chapter 1, mourning dress was pervasive in Britain in the early twentieth century, and while gray garments were appropriate for half-mourning, only black could be worn in the period immediately following a close relative’s death. The exchange is also significant because Buck draws attention to the original owner of Stephen’s trousers and thus to the fact that they are secondhand. Stephen’s trousers (unlike Dollard’s borrowed pants) fit, but Buck emphasizes their castoff status and specifically their anonymous origins (“God knows [who] left them off”). He speculates that their original owner must have been both diseased (“poxy”) and unattractive (“blowsy”). He thus positions the secondhand trousers not as inert material but as linked to the body and persona of the man who sold them.

Read in this light, Stephen’s “secondleg” pants might imperil his health—they could literally carry infection—and they enchain him with another man whose qualities may influence Stephen. Perhaps for these reasons, Buck offers Stephen a pair of his own pants, which he represents as flattering and implicitly free from the taint of the other pair. If Stephen is going to face the world in clothes that distribute another person, then Buck’s offer conveys an opportunity to put on the known, the healthy, and the familiar. In his refusal to wear Buck’s pants, Stephen cites mourning conventions, but his reflections later in the novel suggest that he resents wearing Buck’s clothing.

In “Proteus,” readers learn that Stephen concurs that clothing distributes the person who originally wore it. As Stephen reclines on the rocks and contemplates his footwear, Ulysses points out that he wears Buck’s shoes: “His gaze brooded upon his broadtoed boots, a buck’s castoffs nebeneinander [juxtaposed or next to each other]. He counted the creases of rucked leather wherein another’s foot had nestled warm. The foot that beat the ground in tripudium, foot I dislove.”75 The passage renders Stephen’s body strange to him as it first identifies the boots as his, and then recalls Buck’s feet in the same boots. The next sentence identifies the feet in the boots as having “beat the ground in tripudium,” a “solemn, religious three-beat dance” that Stephen will perform in “Circe.”76 In this sentence, Stephen either is once again seeing the feet in the boots as his, perhaps in a future time, or is recalling a dance performed by Buck that is not recorded in Ulysses. As a result, the final phrase—“foot I dislove”—is either Stephen’s or Buck’s foot, an irresolvable identification generated and maintained by the secondhand boots. The German word nebeneinander nicely captures Stephen’s problem: in putting on Buck’s castoffs, he juxtaposes himself with the friend from whom he wants to be distinguished.

This passage provides an acute example of Garry Leonard’s observation that “Joyce shows us self-awareness is the result of an unanticipated gap in the narrative of the self, a gap that briefly exposes selfhood as a fiction.”77 Secondhand attire, I am arguing, has the power to produce such gaps; because Stephen cannot view the boots as a neutral commodity, they disrupt the fiction of his independence and self-authoring.78 His musings also highlight the problem of possession acutely raised by the castoff: Does Stephen own these boots, or does Buck? Or, to put it differently, might the used boots take possession of Stephen himself?

As Stephen takes on Buck’s distributed persona through used clothing, Ulysses points to the problem of wearing garments whose histories are all too familiar. Joyce’s character can never lace up “his broadtoed boots” without recalling the man who first wore them; the boots thus conjure up the “brother soul” who, Stephen speculates, “will now leave me.”79 The boots have a history with a specific body, and while that body may not have marked the clothing in a manner perceivable by the senses, Stephen constructs such a mark. Although he insists on being accepted “as I am. All or not at all,”80 the boots have the power to qualify or taint who he is. They refuse the inert role of the commodity and position Stephen and Buck in a serial relationship—one in which Buck comes first.81

Joyce’s representations of secondhand garments thus mirror the accounts of other writers in the period who depict used clothing as constructing associations between people through material goods that extract and impose aspects of the original owner’s being. For a character who wants to exempt himself from all reciprocal obligations, hand-me-downs from a friend signal a sartorial colonization, a material form of association that reminds the would-be artist of his dependence on and enchainment with others.82 While Stephen might pride himself on self-fashioning, he is instead partially fashioned by others through the medium of used clothing. What serves as a form of mild embarrassment or an occasion for self-deprecating humor in middlebrow texts becomes an experience that rankles: Joyce’s nascent modernist artist resists secondhand clothes that render him nebeneinander, and he resents the limited economy in which castoffs force him to participate.

Joyce’s texts imply that if one has to wear used clothing, it does the least damage to one’s integrity if it comes through a shop or another venue that obscures the garment’s origins. Jean Rhys’s characters similarly emphasize the import of distancing secondhand garments from the bodies who first wore them. They routinely purchase used clothing, including Julia Martin in After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie, who procures a few items in preparation for a trip from Paris to London. The narrator reports, “The idea of buying new clothes comforted her, and she got out of bed and dressed. At three o’clock she was back at her hotel, carrying the clothes she had bought at a secondhand shop in the Rue Rocher—a dark grey coat and hat, and a very cheap dress, too short for the prevailing fashion.” Although the dress she purchases is not fashionable, and when she “dressed herself in the new clothes,…the effect was not so pleasing as she had hoped,”83 her disappointment with the coat, hat, and dress appears to stem from a general problem of fashionability, not from the garments’ status as someone else’s castoffs. Like the Stephen Dedalus of Portrait of the Artist, Julia can regard her acquisitions as “new” and “secondhand” at once, and she uses the adjective “new” two times in describing the used garments. Because Julia buys these garments at a shop, her experience of consumption is almost identical to the purchase of genuinely new clothing; by decisively separating a garment’s first and second owners, the store on the Rue Rocher provides the distance that obscures a given item’s history and renders it acceptable.

Contrast this experience with that of Rhys’s protagonist Teresa in “A Solid House,” a short story set during an air raid.84 She is forced to buy unattractive secondhand clothing from her landlady, Miss Spearman, but Teresa is most upset when she observes her own castoff languishing in Spearman’s stock: “[S]he recognized her own black dress in the cupboard. It was next to a shapeless purple coat. A cast-off self, it stared back so forlornly, so threateningly that she turned her eyes away.”85 Rhys’s story presents the inverse of Buck and Stephen’s boots. While Stephen experiences frustration and alienation because he wears boots that mobilize their original owner, Teresa finds herself unsettled by the proximity of the unsold castoff, which her imagination animates. In her view, the dress can see—it stares—and feel: it regards its owner with sadness and anger. As in “Illusion,” the short story by Rhys discussed in chapter 1, in “A Solid House,” Rhys figures the garment as a quasi-subject; while the emphasis falls differently in the stories, in both the unworn garment emerges as malign. In “A Solid House,” the dress’s purported malevolence stems from its status as not just a castoff but a “cast-off self,” a thing that has captured something of Teresa’s history and identity—of who she was while wearing it. The garment-self is not valued by the marketplace, as Spearman identifies it as “well cut” but also “depressing” and not worth very much,86 a comment that sheds light on Teresa’s own figurative worth. In this example, the secondhand dress confronts its original owner because it is not (yet) distributed. Moreover, “A Solid House” suggests that if the dress is sold for the cheaper price that Spearman recommends, it will move downward in the marketplace, devaluing Teresa’s selfhood and history with it.

This movement is cast as sorrowful and threatening in Rhys’s story, and it is useful to remember that similar experiences were treated lightheartedly in texts aimed at popular audiences of the same period. The narrator of Delafield’s Diary of a Provincial Lady, for example, is shocked to discover that a “grey georgette [dress] only sacrificed reluctantly at eleventh hour from my wardrobe” for a local rummage sale has been priced at a mere “three-and sixpence.”87 The dress’s value to the narrator, who regards parting with it as a sacrifice, is challenged by its low worth in the estimation of the community, but she does not dwell on this discovery, nor does she anthropomorphize the frock. In a less kindly version of this situation, the “fussy little man” in a cartoon published in Punch on September 22, 1926, attempts to retrieve some of his garments, which his wife donated to a charity rummage sale, only to be scathingly informed that he might find them “at the fourpenny stall.”88 In these texts, readers are encouraged to laugh with or at characters who overestimate the value of their old clothes. The comedy takes some of the sting out of the discovery; if buying and selling used garments disappoints fictional characters across cultural strata, only modernist novels figure the castoff as a painful threat to individuality and selfhood.

One final example illustrates British modernism’s charged response to secondhand clothing, which it collectively depicts as a form of material interdependence that thwarts independent action and development. In chapter 2 of her polemic Three Guineas, Virginia Woolf responds to a “letter” that requests, in part, donations of used clothing to be sold at “bargain prices” to “women whose professions require that they should have presentable day and evening dresses which they can ill afford to buy.”89 Woolf asks why the representative of professional women is so poor “that she must beg for cast-off clothing for a bazaar,”90 a query that launches the author into an exploration of the continued economic disparities between professional men and women and of the difficulty that women faced in entering the professions. While the need for secondhand clothing recedes into the background of her analysis, it seems clear that Woolf (like Joyce and Rhys) regarded the consumption of genuinely new clothing as a norm for all but the working class; her selection of the castoff as a telling detail locates Three Guineas at a particular historical moment when Woolf (and many others) assumed that most people ought to be able to purchase new garments. If, as she reflects elsewhere, “a castoff dress here and there are the perquisites of the private servant,”91 the castoff is emphatically not desirable for the daughters of educated men, representing as it does a form of material dependence that compromises the “weapon of independent opinion”92 that, Woolf argues, women must wield if their social and political activities are to work for peace. Three Guineas positions women’s poverty—encapsulated in the fact that they can “ill afford to buy” new clothes—as a threat to independent thinking and action; like the castoff in the fiction of Joyce and Rhys, used clothing in Woolf’s polemic figures an interrelationship that compromises those who must put on the dresses—and even stockings—that have been molded to another body.

In her influential study Adorned in Dreams, Elizabeth Wilson has argued that the modern consumer was “fearful of not sustaining the autonomy of the self…. The way in which [he or she] dress[ed] may [have] assuage[d] that fear by stabilizing…individual identity.”93 But if and when characters in and subjects of modernist fiction and nonfiction are forced to dress in the clothing of people they know, or if they cannot sell their old clothes, Wilson’s formulation is reversed. Instead of “stabilizing…individual identity,” secondhand garments compromise it: they trouble boundaries between self and other at the material and psychological levels. The proximity of used garments to multiple owners complicates the status of the individual in such works, insinuating that humans are dividual creatures constituted by objects that have histories that precede and survive them. Although the characters and authors I have discussed do not welcome this knowledge, readers are reminded that the self is not autonomous or stable: it is instead, sometimes literally, walking in another man’s shoes.

The Threat of Secondhand Style

As I have argued, secondhand garments rendered people at the mercy of their clothes in the early twentieth century due to a specific historical circumstance: a number of consumers were obliged to purchase the castoffs of others after becoming used to genuinely new clothing. While the economic problems faced by the new and old poor undoubtedly meant that individuals and families bought other material goods on the secondhand market, such purchases are represented as unproblematic. Consider, for example, Stephen Dedalus in Portrait of the Artist, who owns a copy of Horace and regards the pages as “human” because they were turned by two brothers whose names are inscribed on the flyleaf.94 Previous ownership infuses the book with warmth and human interest, perhaps because Joyce’s character wants to make a distinction between market (clothing) and symbolic (written word) economies.95 But this difference also inheres in the fact that clothing admits of a more intimate relationship to the original owner than do other objects; secondhand clothes are most comfortable, and least alienating, when the original owner cannot be identified. As noted in the introduction, Jacques Lacan’s model of the mirror stage and Charles Cooley’s “looking-glass self” theorize that garments and accessories become one with the human body at the crucial moment when an infant first apprehends her reflection or when an adult attempts to imagine his identity in the eyes of others. The process of self-awareness can proceed smoothly if the objects that help to assemble identity cooperate—if they do not communicate histories separate from that of the human subject working to consolidate a self-owning, self-determining individuality. The fictional treatment of secondhand attire illustrates the obverse of this process and the temptation to animate matter in a way that complicates modern identity. A character finds it difficult to extract a castoff item from the first owner’s selfhood; if the owner and the garment remain close to each other, the process is all but impossible.

Between the wars, a range of writers depicted used clothing as particularly able to compromise individuality. Whether in cartoons, short fiction, or novels, they suggest that part of the original owner stays with a garment that he or she wore. This association works at several levels. Most basically, a castoff conveys information about the person who first wore it, such as the size of his feet, the extent of his or her parsimony, or the shape of her body. More significantly, secondhand clothes can carry memories and identity, such as the way Buck Mulligan’s boots convey his personality whenever Stephen Dedalus looks at them on his own feet.

Texts across a range of cultural registers trace the activity of the used garment as thing, but there is a marked difference in tone. In part, the comedy with which most popular works take up the subject stems from the general style that writers employ; as Faye Hammill has noted, middlebrow prose is often characterized by “witty, polished surfaces” that, as in the examples discussed, minimize the difficulties that characters encounter.96 Modernist writers seldom minimize difficulties; moreover, they are invested in models of the artist—specifically in an iconoclastic individualism—that colors their protagonists.97 As Fredric Jameson argues, literary modernism was

predicated on the invention of a personal, private style, as unmistakable as your fingerprint, as incomparable as your own body. But this means that the modernist aesthetic is in some way organically linked to the conception of a unique self and private identity, a unique personality and individuality, which can be expected to generate its own unique vision of the world and to forge its own unique, unmistakable style.98

This investment in the unique, the personal, and the private was shared by artists who worked in other media: witness the words of architect Le Corbusier, who in 1919 opined (in a reference to music and architecture) that “to rise above oneself is a profoundly individual act. One doesn’t do so with second-hand clothing.”99 Anne Anlin Cheng, who reads this passage, observes, “Art, it would appear, cannot be born from secondhand clothing.”100 This is indeed modernism’s claim. Castoffs functioned as tropes as well as material goods in the interwar years; Le Corbusier used secondhand attire as the figurative opposite of the original, the independent, and the transformative. Characters like Stephen Dedalus appear to have been schooled at Le Corbusier’s knee; when literally wearing secondhand attire whose initial owner he knows, Stephen frets about his relationship to the donor and about his ability to live autonomously and to create in a “unique, unmistakable style.”

Such investment in newness—in garments that few consumers could afford—is also espoused by popular writers when they construct characters who self-identify as highbrow artists. For example, Sax Rohmer’s The Orchard of Tears—the one “serious” work by the author of the popular Fu Manchu novels—depicts an illustrator who reacts with anger after being dubbed “the Dana Gibson of the trenches”:

“There is a certain type of critic,” he said, “who properly ought to have been a wardrobe dealer: he is eternally reaching down the ‘mantle’ of somebody or other and assuring the victim of his kindness that it fits him like a glove. Now no man can make a show in a second-hand outfit, and an artist is lost when folks begin to talk about the ‘mantle’ of somebody or other having ‘fallen upon him.’ ”101

Rohmer’s character adopts modernism’s attitude toward secondhand clothing and, in so doing, baldly explicates why writers like Joyce, Rhys, and Woolf were so suspicious of the castoff: no “man [sic] can make a show” in either a used suit or secondhand style, he claims, eliding material that one might wear with art that one might create. Like Le Corbusier’s contemporary remark, Rohmer aligns self with surface; both artists aver that subject and garment-object are so aligned that one can be no more than what one wears. These comments illustrate the obverse of fancy dress, which promised that one might be transformed—indeed, bettered—through a new garment that conferred qualities and talents that one did not possess in ordinary clothes. For modernist writers, secondhand clothes had the opposite quality: they degrade, they muddle, and they qualify the person who wears them. By blurring borders between characters—by placing them in a serial relationship that compromises the ability to “rise above,” to “make a show,” or to exercise independent opinion in life or art—such works both suggest that the bourgeois individualist subject is a myth and mourn their characters’ inability to inhabit that subjectivity.

Le Corbusier, Sax Rohmer, James Joyce, Jean Rhys, and Virginia Woolf saw in the sartorial world a correlative for artistic forms. They and their characters idealize modern commerce—the trade in the new—in a manner that few of their contemporaries could afford to emulate. If texts aimed at a middlebrow readership recognized the sartorial circumstances that many British citizens had to negotiate between the wars, modernist writers resisted the “foul rag and bone shop” that Yeats would so memorably invoke in “The Circus Animals’ Desertion.”102 Yeats’s speaker might resolve to “lie down” in the mire for poetic inspiration,103 but he (like many modernist characters) emphasizes the abjection of the “old rags” on offer. Secondhand clothes offered an opportunity to think through the way the material world mediates human relationship and identity; the used dress, shoes, or trousers exemplifies the profound interconnection between persons and suggests that garments, more than other objects, highlight the serialization of people who would prefer to see themselves as unique individuals. While a range of writers recognize this fact, the realization was almost unbearable to those authors who aimed to break with tradition and who constructed characters who would resist a range of norms. Those who view clothing as an intimate part of the self—who see garments as part of their owner—refuse the shared narrative that might be inscribed through the castoff; or, if forced to wear it, they feel a profound dispossession and loss of selfhood.