The evening gown and the mackintosh offered different lenses to writers seeking to explore the relationship between people and the things they wore. The evening gown provided a seemingly appealing sartorial form to middle- and upper-class women eager to enjoy the pleasure of individualizing, bespoke dress. Fiction and nonfiction of the period suggests, however, that the gown’s articulation of a range of negative gender roles denied many wearers a sense of control and self-expression; whether the gowns invoked a “world of mourning” or a lost venue for aesthetic pleasure, writers position the garment as yoking women to a material array that assembled not confident, attractive subjects but things that were embarrassed, saddened, and viewed with cynicism.

The mackintosh seems worlds apart from the evening gown, which was exemplified by leisure and expense. A coat that was, for many years, associated with the poor and the dispossessed, it became a trope for the loss of individuality, for exposure to violence, and even for death. The mac came to serve as a reminder of the object world’s surprising persistence and thus its contrast to the fragility of human bodies. If evening gowns assembled women in ways that turned them into abject things, mackintoshes disassembled individuals: in the best cases, humans become masses; in the worst cases, they become corpses.

In this chapter, I take up the fancy-dress costume, which highlights the relationship between self and surface. Fancy dress holds out and withholds the promise that one can be what one wears. Like the evening gown, it proffers access to idealized subjectivities assembled through the cooperation of persons and things; like the mackintosh, it demeans because it refuses to cooperate—to work in harmonious assembly—with those who wear it. That only a very few literary characters can transcend their ordinary selves through fancy dress—indeed, that only two literary characters can abandon all pretense to an ordinary self—reveals a significant point of agreement across writers of modernist and popular fiction: only the very wealthy, extraordinary individual can manipulate a material world in which the self is the surface. While the repeated representations of fancy dress suggest that writers were intrigued by new models of the self that might be activated through clothing, such models seldom materialize. To be modern seemingly meant the desire for a flexible identity that remained out of reach for most Britons.

Fancy dress was a prevalent form of early-twentieth-century entertainment, a pervasive sartorial practice that made its way into cartoons, fiction, films, advice manuals, dancing guides, and other print media. The popularity and representation of fancy dress in the twentieth century has received little scholarly attention. Terry Castle, who writes about British masquerade practices in the eighteenth century, argues that masquerade had become marginalized in fiction by the turn of the twentieth century, when costume moved into “minor…subgenres such as the detective novel or the Harlequin romance type of pulp fiction.”1 While I will examine one text that fits this description (Dorothy L. Sayers’s Murder Must Advertise, which Castle briefly mentions), I challenge her claim on two counts: by discussing a range of texts in which fancy dress features and by rejecting the assumption that the presence of fancy dress in popular work qualifies as marginalization.2

Before proceeding, however, a brief definition of what may seem a baggy term is in order. The OED defines “fancy dress” as “a costume arranged according to the wearer’s fancy,”3 which suggests that fancy dress is limited by only the wearer’s imagination and originality. In the early twentieth century, fancy-dress balls and parties were largely invitation only and attended by social equals, whose costumes did not serve as genuine disguises. A costume did not leave the wearer’s personality behind but temporarily infused his or her appearance with historical, artistic, or creative properties. In other words, fancy dress was intended to catch the eye and to encourage audiences to view the self differently without, generally, obscuring the identity. One late-nineteenth-century example, a costume worn by George J. Nicholls, is illustrative. Nicholls dressed as a side of bacon for the Covent Garden Fancy Dress Ball in April 1894, at which he won first prize for his costume (figure 3.1).4 The photograph makes plain that those who knew Nicholls would have been able to identify him; while his Dadaesque costume envelops his body, his face is uncovered. This image has appeared in many humorous posts on the Internet, but fancy dress allowed Nicholls—then a young man entering the grocery and provisions trade—to embody his love of bacon, a love so great that he would write the book Bacon and Hams in 1917. The costume thus emerges as a materialization of career aspirations, and Nicholl’s choice to dress as a thing—indeed, as meat that used to be alive—also demonstrates the way that fancy dress enabled people to play with the idea of being something other than human. Nicholl’s costume at once materializes his thoughts about his profession and covers an agential, thinking being in the guise of inert flesh.

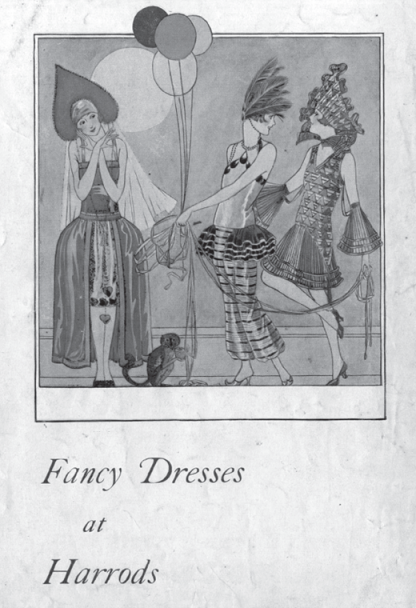

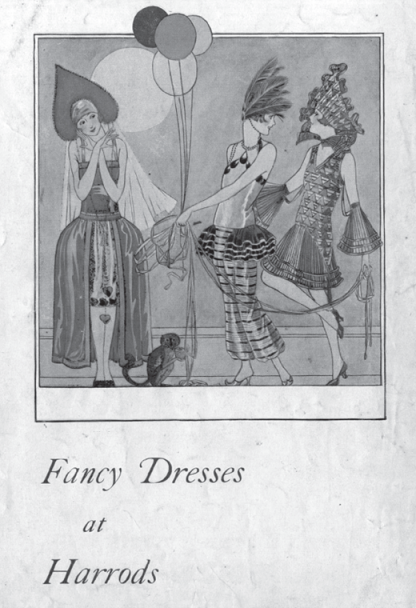

Like the evening gown, fancy dress was normally worn by members of the upper and middle classes. Fancy dress could be rented, purchased at major retailers (such as Harrods), or bespoke, and men and women could adopt a popular type (such as Pierrot), a historical character, a place, an era, or an abstract idea. As articles and advertisements in fashion periodicals and newspapers suggest, fancy dress seemingly offered Britons a wide range of lenses to place over their normal identities—to enhance, but not disguise, their everyday appearance and persona. In the periodical press of the day, fancy-dress costumes emerged as the supreme sartorial form for projecting an idealized self, one that would be free from the quotidian demands of social norms and practicality that governed many garments.

While magazines and advice manuals celebrate the creative possibilities that fancy dress offered wearers, many novels and cartoons instead depict those in costumes as at the mercy of their clothes. Writers who aimed at a popular audience used fancy dress to reinforce the difference between subjects and objects—between persons and things. Current theoretical work complicates this binary; for example, anthropologist Daniel Miller argues that “there is no true inner self. We are not Emperors represented by clothes, because if we remove the clothes there isn’t an inner core. The clothes [are] not superficial, they actually [are] what made us that we think we are.”5 Miller’s work (and that of others) places an emphasis on the power of things, which work in harmony with persons to materialize a self. In this kind of argument, things play an active role; there is no opposition between subject and object but a profound synthesis between the two that we call the self. What we see in most early-twentieth-century work, however, is a rejection of this hypothesis; in the majority of the examples I discuss in this chapter, subject and object remain distinct and often at odds with each other.

The uneasy laughter and outright anxiety experienced by many British characters in fancy dress insist that people are more than what they wear. Most representations of fancy dress depict costumes as emphasizing (through correspondence or contrast) the existing qualities of the characters wearing them. Wealthy characters are what they wear, but this is less a sign that they have transcended their everyday identities than a materialization of upper-class vanity, perversity, and immodesty.6 And middle-class characters fare no better; the aspirations captured in their fancy dress repeatedly fall short because they simply cannot become the costumes they adopt. After examining how popular forms maintain depth ontology—the belief that a self is located somewhere “inside” an individual—in the face of the potential challenge of fancy dress, I turn to two novels that celebrate the potential of persons to become things or, rather, to become different persons with the help of things. Virginia Woolf—herself immersed in a social circle where fancy dress was common—learned from fancy dress an appreciative and flexible understanding of the relationship between self and clothing that is reflected in Orlando. Woolf was not alone in creating a protagonist who can be what she wears. In Murder Must Advertise, Sayers similarly endows Lord Peter Wimsey with the uncanny ability to enjoy multiple selves through costume. In these two works, different in both cultural register and genre, fancy dress inspires ontological experiments that look ahead to postmodern models of identity. At the same time, the radical experiments are limited by a shared sense that aristocratic birth, wealth, education, and talent are necessary to evade depth ontology: fancy dress proffers a self that may be all surface, but only a limited number of characters get to enjoy the pleasures that such selfhood supplies.

If the 1920s and 1930s were the zenith of fancy dress, the 1940s and 1950s were its nadir. The few examples that emerged in this period are colored by nostalgia for prewar life. Doubtless, the wartime economy and postwar shortages made the idea that one could have clothing simply for “dressing up” a pleasurable fantasy. As with secondhand clothes, total war rendered the relationship between self and garment less troubling than it had been. Such historical shifts position the first half of the twentieth century as a particularly vivid moment during which writers, and their contemporaries, trained their eyes on the relationship between persons and garments.

An Epidemic of Fancy Dress

With the exception of the war years, the first four decades of the twentieth century witnessed a boom in the popularity and widespread use of fancy dress. This category of garb was not, of course, invented in the period; as Castle notes in her study of eighteenth-century masquerade, fancy dress first became popular in the 1720s. The masquerades that Castle writes about mixed social classes of participants who wore costumes that disguised their identities and features, but in the late eighteenth century, “these festivities were brought into the home and became part of the family’s private life.”7 In part, the abandonment of public fancy-dress parties stemmed from the criminality and loose moral behavior that the disguises promoted. Costume balls again became socially respectable in the mid-nineteenth century only because of Queen Victoria’s enthusiasm for historical costumes that did not conceal the wearers’ faces.8 Nanette Thrush argues that Victoria and her court used historical costumes “to differentiate their interest in ‘fancy dress’ from the licentious masques of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.”9 By flavoring fancy dress with educational and cultural virtues, upper-class Victorians were able to add costume parties and balls to a season’s social events. As time went on, and as the middle class also warmed up to fancy dress, other types of costume became common, though historical fancy dress remained popular.

The nineteenth century witnessed the social redemption of fancy dress, but the twentieth century most widely embraced the costuming craze. Dress historians Anthea Jarvis and Patricia Raine observe that “in the years immediately preceding the First World War the wearing of fancy dress reached near epidemic proportions.”10 The outbreak of the war temporarily decreased the occasions for which fancy dress was thought to be appropriate—Jarvis and Raine note that “the anxieties and economies of wartime soon put a halt to its more frivolous aspects, although throughout the war pageants and tableaux vivants played an important part in raising funds for war charities”11—but what remains noteworthy from our historical vantage point is the presence of fancy dress in explicitly military venues. For example, some interned British and German soldiers were allowed to hold fancy-dress parties to help pass the time in captivity. The Illustrated Sunday Herald reported on a “Fancy Dress Ball for Germans” on April 11, 1915. According to a guard at one Irish prison, the German internees had “a fancy dress ball, at which they dressed up as Red Indians, clowns, Jack Johnsons, squaws, ballet girls, cowboys, etc.”12 Fancy dress was considered appropriate for soldiers no longer on active duty as well as their captors. In contrast, civilians were never able to enjoy fancy dress unless it were under the guise of war work. The Illustrated Sunday Herald column “Through the Eyes of a Woman” reported that “a dreadful rumour got about that the frivolous Lady X had given a masked ball, but she had only asked a few friends to bring their pet brands of respirators so that she could choose one for her husband’s regiment.”13 The continued presence of fancy dress—and references to it—during the war years indicates how prevalent and widely embraced fancy dress had become by the second decade of the twentieth century. And after World War I, as Jarvis and Raine simply state, “there appeared to be no escape from fancy dress.”14

In the 1920s, periodicals depicted fancy dress as pleasurable, fashionable play. As British Vogue reported on July 25, 1928,

Never has London suffered such an attack of costumitis. Not content with the costume balls that crowd every night…addicts stray into other people’s “plain clothes” dances. Thus, at Dorchester House (the Last Ball at), a highly decorous and distinguished company, trying to recover discarded pre-war grandeur, were startled by an invasion of wild monkeys from Lady Hillingdon and Mrs. Gerard Leigh’s joint ball.15

Vogue elsewhere offered stylish fancy-dress suggestions so its readers would be inspired to range beyond “wild monkeys.” For example, the article “By Their Fruits and Flowers Ye Shall Know Them,” published in the Late January 1923 issue, suggests costumes such as “Citron” and “Pineapple.”16 These types of pieces underline the high premium placed on original fancy dress, and while Vogue aimed at an upper-class readership, other periodicals ensured that less-well-off Britons could make their own fancy dress. Weldon’s Patterns was just one of several publications that provided designs for costumes, including one for “records” that was popular with young women in Blackpool in the 1930s.17

Fancy dress was, moreover, addressed by advice manuals, which guided readers in how to adopt an appropriate costume. In his book How and What to Dance, Geoffrey D’Egville urges “both sexes to take into consideration their personal characteristics, such as build, complexion, colour of hair, etc., before selecting their costumes. Incongruities such as a short stout man with glasses disguised as Mephistopheles, or a tall Spanish-looking lady as Little Red Riding Hood are absurd.”18 Such books offered help but also highlighted the challenge of selecting an appropriate costume, a challenge that became the subject of many jokes in popular novels and cartoons. If D’Egville’s suggestions did not provide enough guidance, Britons could seek out a copy of Ardern Holt’s Fancy Dresses Described: or, What to Wear at Fancy Balls, first published in 1875 and reissued in six editions through 1900. The book’s introduction (subtitled “But, What Are We to Wear?”) informs readers that they could find “several hundred” suggestions in the volume, in addition to guidance on decoration, dances, hairdressing, and other topics. Holt offers ideas that range from “Alphabet” to “Charles I, Period” to “Zenobia.” Those who desired historical accuracy and a British origin in their fancy dress could turn to Mrs. Charles H. Ashdown’s British Costume During XIX Centuries (Civil and Ecclesiastical), which drew on manuscripts, tomb effigies, and other sources to offer, for example, details about the appearance and construction of men’s tabards during the reign of Edward II.19 Holt urged her readers “to study what is individually becoming to themselves, and then to bring to bear some little care in the carrying out of the dresses they select, if they wish their costumes to be really a success.”20 Ashdown, for her part, regretted the “painful anachronisms” occasioned by historically incorrect costumes.21 Such descriptions underline the work as well as the pleasure that went into selecting and wearing a fancy-dress costume.

Depending on a person’s wherewithal, fancy dress could be made at home, rented, purchased off the rack, or bespoke. Companies like Clarkson’s rented and styled costumes, and visits to the famous shop were chronicled in Vogue.22 The department store Debenham and Freebody partnered with Holt and advertised that “any of the Dresses described in [her] book can be made to order.”23 Not to be outdone, Harrods offered its own selection of costumes, as evidenced by Fancy Dresses at Harrods, a catalog published in November 1927 that illustrates fancy dress for men, women, and children. The costumes, which could be purchased, ranged from the elaborate, such as the “Turkish Delight” guise shown on the cover, which cost 11 guineas, to the basic (figure 3.2).24 All the costumes in this catalog were quite high end; the least expensive was a men’s “Jazz Clown” outfit, which was an “economical” 18 shillings and 6 pence, still outside the budgets of most British consumers.

Such advertising materials provide evidence of the range of options in the period; other sources give a sense of what people actually wore. Some fancy-dress balls were amply documented, both by reporters and in photograph albums published to commemorate the events. Among the most lavish was undoubtedly the Devonshire House Ball, which was held in 1897 to celebrate Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee.25 Fabulous costumes, such as Lady Arthur Paget’s gem-encrusted rendition of Cleopatra’s attire (made by the couturier Worth),26 communicated the wearer’s wealth and standing and support Thrush’s point that fancy dress often “went far beyond modern conceptions of costume to a level of extravagance that is nothing less than stunning” (figure 3.3).27 Paget’s “oriental” costume, which gave her the chance to pile on the gems, demonstrates that fancy dress could serve as an occasion to display one’s wealth beyond that offered by the ordinary evening gown.

The costumes of wealthy men and women were also documented in society columns and the fashion press, such as a photograph of Lady Abdy that was published in the August 22, 1928, issue of Vogue (figure 3.4).28 Although this is but one example of a twentieth-century fancy-dress costume, its spectacular nature and its appearance in Vogue provide insight into the heights to which fancy-dress wearers might aspire. According to the caption, Abdy’s costume represented “sea mist: large amber coloured balloons shrouded in a cloud of grey and green tulle rise from the waist and float about the silver cockleshell head-dress.”29 In large part, this specific spectacle warranted the attention of Vogue readers because Abdy had selected a creative and unique natural feature to portray; the bespoke origin of Abdy’s costume—the originality of her dress—made it worthy of this profile. Abdy’s fancy dress, moreover, employed a contemporary fashion vernacular: the moyen âge line of her costume was stylish for evening wear in the late 1920s and had been popularized by the French designers Jean Patou and Coco Chanel, among others. Abdy’s gown and inspiration, therefore, suggest two important challenges to appearing in fancy dress: the selection of an appropriate, and appropriately unusual, idea for the costume, and the integration of contemporary styles into it. Discussion of Abdy’s costume would not be complete without considering one of her most notable accessories: the cockleshell hat. This arresting headgear proclaims the wearer’s mastery of modernity through its evocation of a shell as an architectural, not a realist, form. Abdy was crowned with a construction reminiscent of the Eiffel Tower and of the bones of skyscrapers going up in cities around the world; her costume thus referenced the natural world through ultra-modern styles and materials. This costume thus proclaimed the wearer’s creativity, wealth, and aristocratic status while highlighting her personal beauty; from our historical vantage point, the photograph also demonstrates the high stakes involved in achieving a creative, flattering costume.

As this brief introduction to fancy dress has demonstrated, the wearing of costumes was widespread among the middle and upper classes, and the costumes could be spectacular. They offered an outlet for creativity and fun—as Fancy Dresses at Harrods enthuses, “Dressing up!…What fun masquerades are!”30—but they also demanded a fair degree of money, taste, and time if they were to be a success. Writers in the early twentieth century repeatedly took up fancy dress, doubtless because it was such popular garb both before and after World War I. Their attitude toward such dress speaks, however, less to the pleasure that such garments offered wearers than to the genre’s inability to make wearers anything other than what they were. While readers catch glimpses of fancy dress’s aspirational qualities—of the hope that costumes may assist individuals in transcending their everyday selves—such yearning is more often punished than realized. Moreover, on the rare occasions when a transformation is effected through fancy dress, it is not the transformation that the characters desire. These types of representations emphasize the immobility of Britons in an interwar class society; whereas some characters gain access to garments and accessories formerly out of their reach, punishment for wearing aspirational fancy dress reminds readers that class was not only an economic but a social hierarchy that few could transcend.

Being “Natural Always”: Middlebrow Representations of Fancy Dress

British authors who wrote for a popular audience deployed fancy dress to highlight the relationship between persons and the things they put on. Although I examine an exception at the end of this chapter, the majority of such works use costume to reinforce depth ontology—the idea that a self is located deep within a person’s psyche or being. The class of the characters depicted in middlebrow works plays a significant role in how fancy dress is inflected: wealthy characters wear fancy dress that materializes their negative traits, while middle-class (and the very occasional working-class) characters are mocked for wearing costumes that cannot conceal who they “truly” are. The sheer number of characters who appear in fancy dress suggests that the practice of costuming raised profound questions about the potentialities of clothing: Can a person enhance or otherwise alter his or her identity through a “simple” change of attire? The answer, in texts that extend from cartoons in Punch to novels by E. M. Delafield, P. G. Wodehouse, and Evelyn Waugh, is a resounding no. While most of these authors treat fancy dress lightheartedly, their repeated rejection of the aspirations embodied in this form betrays a collective disquiet about the potency of things, which may work in assemblage with a person and, in so doing, change who that person “really” is. The rare works in which a character is changed through wearing a costume configure the experience as a cautionary tale: they suggest that such a transformation is not that to which the wearer aspired. Together, such examples demonstrate what Faye Hammill has called a key quality of the English middlebrow—its lack of pretension31—and suggest that fancy dress punished pretentious characters of all classes.

Middlebrow fiction of the period consistently mocks wealthy characters and “intellectuals” whose fancy dress serves to emphasize their negative traits. Delafield’s Diary of a Provincial Lady, for example, concludes with a party at which some guests wear fancy dress. The host, snobbish Lady B., receives her guests “in magnificent Eastern costume, with pearls dripping all over her, and surrounded by equally bejewelled friends.”32 When she “smiles graciously and shakes hands without looking at any of us,”33 readers can infer that Lady B.’s vanity and sense of social superiority are reflected in her costume. Delafield’s social satire takes aim not only at the local aristocracy (who fancy themselves Eastern potentates) but also at self-professed intellectuals who similarly adopt costumes that materialize an inflated sense of self-worth. The narrator is “greeted by an unpleasant-looking Hamlet, who suddenly turns out to be Miss Pankerton.”34 Pankerton’s highbrow pretensions and domineering personality are perfectly captured by her Hamlet costume, which offers not a gender-bending take on identity (à la Orlando) but a literalization of Pankerton’s masculine style and sense of intellectual superiority. Delafield extends her satire when Pankerton “accusingly” asks why the protagonist is not wearing fancy dress and insists, “It would do me all the good in the world to give myself over to the Carnival spirit. It is what I need.”35 Readers are meant to regard the “Carnival spirit” as an affectation, as pride and self-satisfaction; wealthy “highbrow” characters embrace fancy dress that literalizes their everyday personae, and Delafield implies that her narrator has been wise to wear ordinary dress to the party. She does not appear spectacular, but she does look appropriate.

Like Delafield, Evelyn Waugh repeatedly deploys fancy dress in his satire, and such garments serve to magnify the character defects of the upper class. In Waugh’s fiction, the shallow Bright Young Things materialize their pursuit of pleasure, superficiality, and shamelessness particularly clearly through costumes. From Waugh’s perspective, fancy dress as a practice reveals the bankruptcy at the heart of the pleasure-bent, liquor-filled 1920s. The biblical allusion of the title of Vile Bodies,36 for example, is profaned during a conversation between the protagonist, Adam, and his on-again, off-again fiancée, Nina, about all the parties they have attended, including “Masked parties, Savage parties, Victorian parties, Greek parties, Wild West parties, Russian parties, Circus parties, parties where one had to dress as somebody else.” This reminiscence ends with the phrase “Those vile bodies,”37 which at once reflects and judges the frenetic leisure and abject physicality of the Bright Young Things. Their corruption and waste of time are encapsulated in the list of fancy-dress themes, a constantly changing array of garb that visually manifests their folly. Adam, Waugh’s middle-class-author figure, hopes to escape the round of parties and is notably never depicted in fancy dress. As someone who is in, but not of, the orbit of the Bright Young Things, Adam focalizes Waugh’s criticism of upper-class characters.

Waugh’s satire, like Delafield’s, takes particular aim at wealthy women in fancy dress; in Waugh’s novel, such attire not only materializes character flaws but poses a threat to the respectable middle class. Miss Runcible, a feckless society beauty whose behavior offers staple material to the gossip columnists in Vile Bodies, wears fancy dress at the “Savage” party, a “Hawaiian costume” that makes her “the life and soul of the evening.”38 While Runcible’s costume and behavior are accepted by her cohort—indeed, they are of so little note that neither the narrator nor the other partygoers describe them—Waugh’s satire of his character becomes clear after she spends the night in the home of Jane Brown, daughter of the prime minister du jour. The Brown family enjoys (temporary) political power, but Waugh indicates that the Browns are not of Runcible’s class and do not enjoy her celebrity status; the prime minister’s son, for example, works “in a motor shop.”39 When Runcible comes downstairs the next morning still wearing her Hawaiian costume, the prime minister is shocked by their encounter: ”Suddenly the door opened and in came a sort of dancing Hottentot woman half-naked.”40 Part of the joke here is about the prime minister’s conventional and conservative response to Runcible, but the novel focuses more attention on Runcible’s extreme exposure in her costume, which materializes her decadence and impropriety. Fancy dress may be amusing, Vile Bodies implies, but it also facilitates departures from conventional attire that push the boundaries of decency. Moreover, Runcible’s fancy dress serves as a vector for her negative influence on the Brown family’s fortunes. The character unwittingly brings down the government after she is photographed leaving No. 10 Downing Street “trailing garlands of equatorial flowers.”41 In Waugh’s novel, Hawaiian fancy dress signals Runcible’s lack of substance—like the costume, there is little to her—and the damage that extends outward from a few garlands. The mere suggestion that the prime minister tolerates Runcible’s fancy dress suffices to ruin his political career, a turn of events that (however amusing) sounds Waugh’s caution: the superficiality endemic to the upper classes and evident in their fancy dress can suck the life out of respectable homes and politicians.

In the 1930s, Waugh repeatedly turned to fancy dress as a sartorial form that neatly materializes the character flaws of wealthy Britons. In his hilarious short story “Cruise (Letters from a Young Lady of Leisure),” his shallow narrator gets her costume idea—to dress as a sailor—for an onboard fancy-dress ball from the ship’s purser. Such balls were “a popular feature of holiday cruises, which enjoyed a boom in the 1920s.”42 Waugh’s character is, however, disappointed by the reaction to her costume:

Well the Ball we had to come in to dinner in our clothes and everyone clapped as we came downstairs. So I was pretty late on account of not being able to make up my mind whether to wear the hat and in the end did and looked a corker. Well it was rather a faint clap for me considering so when I looked about there were about twenty girls and some women all dressed like me so how cynical the purser turns out to be. Bertie looked horribly dull as an apache. Mum and Papa were sweet. Miss P. had a ballet dress from the Russian ballet which couldn’t have been more unsuitable so we had champagne for dinner and were jolly and they threw paper streamers.43

Fancy dress makes visible the narrator’s lack of creativity or originality; her appearance in the sailor costume underlines her status as a generalized “young lady of leisure,” a type that Waugh represents as all of a (vacuous) piece. Notably, her wealthy companions are equally satirized through fancy dress that is conventional (her brother’s “dull” Apache costume) or, if creative and modern, “unsuitable” (Miss P.’s Russian-ballet costume). In “Cruise,” it seems that there are no costumes that are at once seemly and striking. Fancy dress serves to expose the correspondence between the appearance and the personae of the Bright Young Things in Waugh’s fiction: they and their costumes are shameless (Miss Runcible in her Hawaiian garb) and substance-less (the narrator of “Cruise” in her sailor suit). Such representations of fancy dress suggest that there is nothing more—no hidden depths—to Waugh’s characters.

Middlebrow works thus employ fancy dress to satirize wealthy and “intellectual” characters whose foolish costumes precisely reflect their pretension, immodesty, and lack of originality. Such examples suggest that these characters lack depth of any kind. There is almost no self to speak of in Lady B., Miss Runcible, and others like them, and they certainly do not know (what there is to know about) themselves. A related form of fancy-dress humor focuses on characters who attempt to but cannot take on new physical qualities or personal traits by donning costumes.44 This type of humor particularly punishes characters who put on aspirational fancy dress: costumes that materialize more wealth, education, and breeding than the wearers are thought to possess ordinarily. Like the satires of upper-class characters, these works support depth ontology because the self cannot be refashioned by material objects, and characters are inconvenienced and shamed because they cannot achieve the heights to which their costumes aspire. If fancy dress purportedly offers the wearer the ability to alter her appearance and identity for an evening, middlebrow texts suggest that, instead, the garment reveals the folly of even trying to “better oneself” temporarily.

Punch, “that barometer of middle-class conservative opinion” in D. J. Taylor’s words,45 exemplifies the embrace of depth ontology. Its cartoons repeatedly mock middle- and working-class characters’ desire to enhance their ordinary selves through fancy dress. In 1936, for example, the weekly depicted a couple wearing false noses and carrying balloons at a seaside “Carnival Week.” The man queries his companion: “Ethel, why can’t we be natural always?”46 This cartoon mocks the notion that fancy dress can ever be “natural”—can ever express a person’s genuine personality. This image, which may be described as gently mocking, has company in more pointedly negative representations of characters who want to transcend their class and condition through fancy dress. In 1938, the magazine ran a cartoon in which two working-class characters ask a costumer, “’Ave you any Elizabethan fancy gent’s suitings?”47 The incredulity on the costumer’s face draws attention to the disjunction between his customers’ working-class appearance and accents and their desired type of fancy dress. Such men, the cartoonist suggests, could never carry off the costume of an Elizabethan gentleman: their aspiration and naïve faith in the power of clothing to transform them are simply laughable.

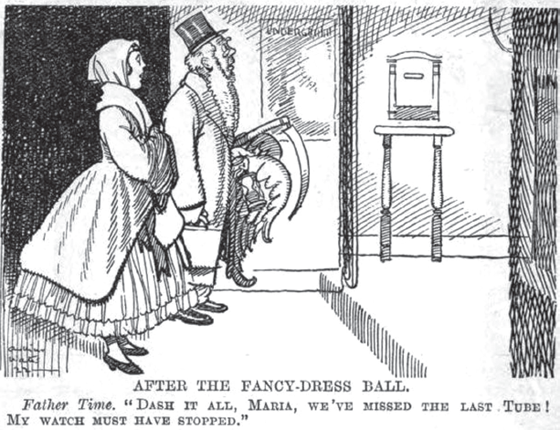

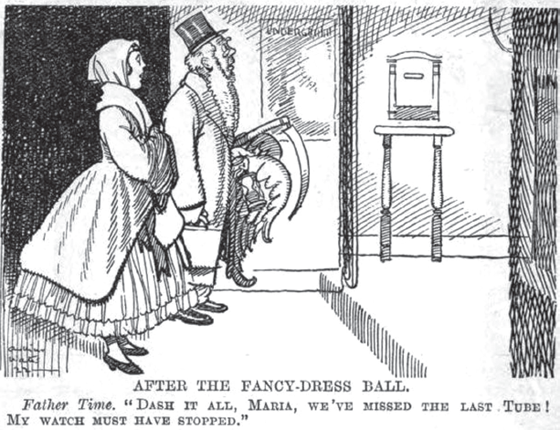

These types of characters are the repeated targets of Punch’s cartoonists. There are, for example, several jokes about men dressed as Father Time not knowing the correct time (figure 3.5). Although the ways in which class works in such cartoons may not be immediately evident, the uncomfortable situations in which these characters find themselves—Father Time and his wife have missed the last subway train, a circumstance that would matter only to someone who cannot afford a private car or taxi—repeatedly point to the folly of men and women who attempt to better themselves in any way through fancy dress. Such betterment may be of small (knowing the correct time) or large degree, but it is seldom achieved. This type of joke was also prevalent in periodicals other than Punch; W. K. Haselden (cartoonist for the Daily Mirror) and Joseph Lee (Evening News) repeatedly depict people who cannot live up to the virtues of an idea or a character represented in their fancy dress.

Even characters slightly lower on the economic and social scale than middlebrow protagonists end up being punished for donning aspirational costumes. P. G. Wodehouse’s Right Ho, Jeeves! chronicles the misadventures of yet another friend of Bertie Wooster who cannot manage to get engaged to the woman he loves. When Gussie Fink-Nottle appears in Wooster’s sitting room dressed as Mephistopheles, the occasion allows Wooster to denigrate fancy-dress costumes and parties in general terms before taking aim at Fink-Nottle’s unusual selection:

The spectacle before me was enough to nonplus anyone. I mean to say, this Fink-Nottle, as I remembered him, was the sort of shy, shrinking goop who might have been expected to shake like an aspen if invited to so much as a social Saturday afternoon at the vicarage. And yet here he was, if one could credit one’s senses, about to take part in a fancy-dress ball, a form of entertainment notoriously a testing experience for the toughest.

And he was attending that fancy-dress ball, mark you—not, like every other well-bred Englishman, as a Pierrot, but as Mephistopheles—this involving, as I need scarcely stress, not only scarlet tights but a pretty frightful false beard.48

Wooster decries Fink-Nottle’s specific costume because it will make him stand out, and for a moment, the joke seems to be about Wooster’s excessive caution in the matter of fancy dress. As the scene develops, however, Fink-Nottle reveals that Jeeves—Wooster’s omnicompetent valet—has recommended that particular fancy dress: “He said that the costume of Pierrot, while pleasing to the eye, lacked the authority of the Mephistopheles costume” and further explains, “Jeeves is a great believer in the moral effect of clothes. He thinks I might be emboldened in a striking costume like this.”49 Fink-Nottle then reports that while the costume has yet to embolden him, he still has faith that he will rise to the level of his garments:

I feel a most frightful chump now, yes, but who can say whether that will not pass off when I get into a mob of other people in fancy dress. I had the same experience as a child, one year during the Christmas festivities. They dressed me up as a rabbit, and the shame was indescribable. Yet when I got to the party and found myself surrounded by scores of other children, many in costumes even ghastlier than my own, I perked up amazingly, joined freely in the revels, and was able to eat so hearty a supper that I was sick twice in the cab coming home.50

Fink-Nottle’s childhood memory of a costume’s transformative power gives him hope that he “might quite easily pull off something pretty impressive.”

His hopes are completely dashed when he takes a cab to the wrong address and cannot correct his mistake or pay the taxi driver, having left his ticket to the dance, his money, and his latchkey at home. Jeeves, seeking to explain why his normally good advice has failed in this instance, explains that “these aberrations of memory are not uncommon with those who, like Mr. Fink-Nottle, belong essentially to what one might call the dreamer-type,” and Wodehouse’s point is made: a good costume cannot bestow on Fink-Nottle qualities that he does not possess. Fink-Nottle might aspire to a commanding, powerful form of masculinity, but he cannot ultimately achieve his dreams by changing into fancy dress. Wodehouse’s reader might suspect that only Jeeves—an aristocrat of taste, if not birth—could make such aspirational attire work for him.

Works such as Right Ho, Jeeves! depict characters who wish for fancy dress to overpower them, expressing the hope that, at times, working-, middle-, and even upper-class Britons could be borne along by things they had selected with a particular end in view. When such transformations actually occur in popular publications, however, a disquiet sets in as the characters in fancy dress lose control of themselves and end up punished for their pretensions. While characters fantasize about challenging depth ontology, those who find their fancy dress shaping their behavior and impact on others are inconvenienced and shamed. Costumes, such stories demonstrate, can alter their wearers, but not always for the better and seldom in the manner that they hoped.

The mildest examples of such transformations are featured in Punch. Arthur Moreland’s “Simple Stories: The Fancy-Dress Dance” tells the tale of Mr. Boomer, who looks nothing like Henry VIII—he is described as “little” and “very small”—but who attends a dance dressed as the king because his domineering wife wants to go as Catherine of Aragon. The character thus contravenes the advice provided in such books as Geoffrey D’Egville’s How and What to Dance and Ardern Holt’s Fancy Dresses Described, but his folly initially bears fruit. When the Boomers arrive at the dance, “everybody started clapping and then laughing because they looked so silly,” but “Mr. Boomer’s silliness didn’t last long because something had been coming over him ever since he had put on the costume. And directly he came into the hall and saw the Vicar dressed up as Cardinal Wolsey it came over him altogether that he was really Henry VIII.”51 What “came over” Boomer is less a vague “something” than the transformative power of his costume, which makes him feel and behave like the famous monarch. Boomer orders “Cardinal Wolsey” to procure a divorce for him, treats other partygoers as his wives, and responds with kingly anger to those who remonstrate with him. Boomer is finally persuaded to go home when his wife speaks to him in character (“my liege it is time we wended homewards”), and he recovers his normal self only when she tells him, “You looked very nice as Henry VIII considering you are almost a dwarf.”52 The short tale concludes with Boomer being told, “Mind you lock up everything before you go to bed,”53 a reminder that the character has returned to his old role as henpecked husband.

In this story, Boomer is temporarily transformed by aspirational fancy dress, or, rather, he is transformed through a costume based on his wife’s aspirations. All his conversion requires is a good costume and the happenstance of context for it, which is provided by the vicar’s appearance as Cardinal Wolsey. Identity, the sketch seems to suggest, is less inherent than contextual and sartorial. Despite the story’s brief intimation that garments can transform people in the right circumstances, Moreland emphasizes the transient nature of such experiences when Boomer’s transformation is reversed and hints that the character may later regret many of his actions as Henry VIII. Although his marriage remains unscathed, the story represents Boomer as offending numerous powerful people at the fancy-dress party, including the vicar, Mrs. Crow (who lives in the largest house in town), and her husband (who becomes “angry”). When Boomer leaves the party, the consensus of “everybody” is that “perhaps he has gone a little too far.”54 If fancy dress effects a transformation, the story suggests, then that change is not generally for a character’s long-term good.

The dangerous transformative power of aspirational costume is rendered even more starkly in Daphne du Maurier’s best-selling novel Rebecca. Unlike the popular texts I have discussed to this point, du Maurier writes in a tragic, not a comic, vein; as a result, her representation of fancy dress is the darkest of the lot. Despite this significant difference, however, du Maurier’s text similarly punishes a character who seeks to better herself through fancy dress. As readers of the novel will remember, the narrator and protagonist of Rebecca is an impoverished (albeit genteel) young woman who suddenly finds herself elevated to upper-class status when she marries the wealthy Maxim de Winter. Despite her good fortune, the narrator never feels herself of the class into which she has married, and she provides an outsider’s view of the elite to which she so desperately wishes to belong.55 Because Rebecca was written and published during the lead up to World War II, scholars have read the novel as critical of the class that partied as Hitler rose to power.56 What critics have not examined, however, are the class concerns embedded in du Maurier’s depiction of fancy dress; while the narrator enthuses that the fancy-dress ball to be held at Manderley, Maxim’s ancestral home, will be “mad ridiculous childish fun!”57 it instead offers a sinister lesson in aspirations punished and the unpredictable changes that costumes can work.

With the encouragement of the baleful Mrs. Danvers, the house-keeper at Manderley, du Maurier’s young protagonist decides to adopt the costume of Caroline de Winter, who is memorialized in a portrait by Sir Henry Raeburn that hangs in the house’s gallery. The narrator knows that Caroline was a sister of Maxim’s “great-great-grandfather. She married a great Whig politician, and was a famous London beauty for years.”58 These details, which are irrelevant to the precise garments in which Caroline was painted, suggest why the young woman so readily accepts Danvers’s suggestion. While “I always loved the girl in white,”59 in reproducing Caroline’s appearance for the fancy-dress party, the narrator clearly hopes to approximate not only the sitter’s wardrobe but also her class, confidence, and powers of attraction. To an insecure and decidedly unglamorous nobody, the fancy-dress costume of Caroline de Winter holds out the possibility of self-improvement, if for only a night. She might finally feel not only in but of Manderley.

When the costume arrives, it briefly works the wished-for magic. In her dress and wig, the narrator is “amazed at the transformation. I looked quite attractive, quite different all together. Not me at all. Someone much more interesting, more vivid and alive.”60 Here, du Maurier captures the possibility of being “quite different” in a costume. That the protagonist describes her appearance as “not me at all” but better than her everyday self seems to indicate that the costume will emerge as a rare example of aspirations achieved. Note, too, that in the costume the narrator looks “more…alive”; the novel hints at the liveliness that may be conferred by material objects, a liveliness that the human body and persona do not possess on their own. Under the fancy dress, “my own dull personality was submerged at last,”61 and the protagonist “watched this self that was not me at all and then smiled; a new, slow smile.”62 Du Maurier’s character could not be clearer: fancy dress has provided her with a new body and self, an experience that controverts models of identity premised on interiority. She even makes plain that her face, which is not covered by the costume, is different: “The eyes were larger surely, the mouth narrower, the skin white and clear.”63 No surgery or other type of self-care generates this change, which suggests that good fancy dress may enable physiological transformations. Finally, a reader may think, here is a literary character who can improve her lot through a costume.

Before proceeding with my analysis of this scene, it is instructive to pause and compare the young protagonist’s experience to this point with mirror scenes discussed earlier, specifically in the works by Rebecca West and Virginia Woolf analyzed in chapter 1. In those novels, characters gaze into a mirror and see not themselves but things; reflections of women in evening gowns do not consolidate the characters’ sense of self but profoundly alienate that self, making it seem less human. Evening gowns, which, like fancy dress can be aspirational attire, are repeatedly represented as failing to help their wearers achieve the status of the Ideal-I, Jacques Lacan’s formulation of a coherent, self-sufficient body and psyche. Du Maurier, in contrast, suggests that fancy dress may provide access to something approaching that state, but what her protagonist sees in the mirror is not an Ideal-I but an Ideal-other: as the narrator “paraded up and down in front” of her reflection, she “did not recognize the face that stared at me in the glass.”64 For a moment, Rebecca suggests that fancy dress, more than any other type of attire, offers women and men the opportunity to assemble a new and improved self through the cooperation of wearer and garments.

It is, however, a brief moment. When the narrator reveals herself to her husband, her sister-in-law Beatrice, and her brother-in-law Giles, they respond with shock and anger. “What the hell do you think you are doing?” Maxim asks before ordering her to “go and change.”65 As the protagonist runs to her room, Danvers looks on in triumph. Beatrice later explains the narrator’s “terrible mistake”: “[T]he dress, you poor dear, the picture you copied of the girl in the gallery. It was what Rebecca did at the last fancy dress ball at Manderley. Identical. The same picture, the same dress. You stood there on the stairs, and for one ghastly moment I thought…”66 The young protagonist has aspired to appear as Caroline de Winter and has instead appeared as a dead (and, as readers later learn, monstrously sexual) woman. Her night and her aspirations have been shattered.

Rebecca offers an admittedly extreme example of the critique of aspirational fancy dress. While the protagonist enjoys “becoming” Caroline de Winter in the privacy of her room and in the reflection in her mirror, she is shocked and horrified to become Rebecca-in-costume in the eyes of Maxim, Beatrice, and Giles. Significantly, becoming Rebecca (however momentarily) initiates a series of events that permanently alter the protagonist, who is unable to return to her old self even after she discards her fancy dress. Although she rejoins the party in an ordinary blue evening gown and thinks, “I might have been my old self again,”67 she is emphatically not her old self. She suffers throughout the evening, enduring a party at which she had hoped to shine.

Post-costume, the narrator realizes that her time in fancy dress did transform her, albeit not in the ways she had hoped. She observes, “The girl who had dressed for the fancy dress ball…had been left behind,”68 and she begins to see the ways that material objects—like the costume—merge her old self with Rebecca: “That mackintosh I wore, that hand-kerchief I used. They were hers. Perhaps she knew and had seen me take them. Jasper had been her dog, and he ran at my heels now. The roses were hers and I cut them.”69 The fancy-dress portrayal of Caroline de Winter literalizes the fact that the protagonist walks in her predecessor’s shoes (literally, in her fancy dress). When Maxim later regretfully observes, “It’s gone forever, that funny, young, lost look that I loved” and “you are so much older,”70 readers see that the narrator has developed a new, hybrid identity. She is no longer the ingénue, nor is she the decadent, sexually wayward Rebecca: she has become something in between.

Rebecca thus implies that aspirational fancy dress can challenge depth ontology, as costume provides first a desired and then an undesirable transformation. In both cases, fancy dress has the power to change who the protagonist is, and her self is revealed to be partly in her and partly on her, an artifact of what she wears and the history of those garments. The changes that fancy dress effects are, however, uncontrollable, and as the novel continues, du Maurier repeatedly links fancy dress (and the parties at which it is worn) with negative, undesirable outcomes. Immediately after the costume ball, Rebecca’s body is discovered in the cabin of her sunken boat, and the de Winters are immersed in the formalities of an inquest and consumed by fear that Maxim’s role in the death of his first wife will come to light. The local newspaper seizes on the timing of the discovery of Rebecca’s body; the protagonist reads “the little line about myself at the bottom, saying whom Maxim had married as his second wife, and how we had just given the fancy dress ball at Manderley. It sounded so crude and callous, in the dark print of the newspaper.”71 Two London papers follow suit, making “great play of the fact that Rebecca’s body had been found the day after the fancy dress ball, as though there was something deliberate about it.”72 These reports represent the de Winters’ exposure to public gossip and legal scrutiny, but they also underline du Maurier’s own “deliberate” choice to juxtapose the fancy-dress ball with the discovery of Rebecca’s corpse. This decision sharpens the novel’s critique of Maxim’s class and lifestyle—Gina Wisker observes that the de Winters’ “fairytale lifestyles are exposed through the contradictions of the text as artifice, a dangerously decadent, culpably blinkered sham”73—but it more importantly highlights the binary between body and self, thing and person, complicated by the protagonist’s fancy-dress costume. After the narrator has been taken for Rebecca, the corpse surfaces, seemingly of its own volition, no longer the husk of a personality but mere matter. All we are is stuff, the corpse seems to say; dead or alive, we are things known to ourselves and others through material objects. As Maxim notes, the identification of Rebecca’s body will be possible even if it has decomposed beyond recognition: “[H]er things will be there still.”74 Such things—Rebecca’s rings, the protagonist’s costume—make du Maurier’s characters who they are in life and death.

Rebecca offers an extreme version of the larger critique of fancy dress: when wealthy characters wear costumes, their personality flaws are materialized; when lower- and middle-class characters wear fancy dress, they are mocked and punished for aspiring to better their condition, even if for only a night. In fiction and cartoons, characters who hoped to be spectacular in their costumes become instead spectacles, and at their most extreme, costumes effect undesirable changes. If, as contemporary theorists like Daniel Miller argue, “stuff actually creates us in the first place,”75 popular literature works to contravene this understanding of self and stuff. Identity is located in a self, not on a body, such texts repeatedly insist. Moreover, representations of fancy dress instruct readers that the material world does not behave according to our wishes. This resistance to the possibilities inherent in costume (and in other types of dress) is startling, but it suggests that most writers accepted a class system that might have been challenged by models of selfhood indebted to materiality (instead of interiority).76 For two writers, however, the promise of a transformation through fancy dress would fuel radical experiments with character. Having learned about the potential of fancy dress from their own experiences of wearing or observing it, Virginia Woolf and Dorothy L. Sayers would not reinforce depth ontology but leave it behind.

“Abandonment at Not Being One’s Usual Self”: Bloomsbury, Fancy Dress, and Orlando

It is striking to note how many of the recollections of Bloomsbury parties focus on costumes. When asked about the parties held in the interwar years, George “Dadie” Rylands unequivocally asserted that “the parties were mostly fancy-dress parties.”77 He focused on “a marvelous party, called the Sailors’ Party, in which we all had to go wearing naval costume. I went as a lower-deck type, and Lytton went as a full Admiral of the Fleet. As you can imagine, with his beard and his cocked hat and his sword he was impressive.”78 As this account suggests, fancy-dress parties complemented Bloomsbury’s campy play with gender, frankness about sexuality, and pleasure in mocking authority; Lytton Strachey’s guise as an admiral, for example, worked in ironic tension with his status during World War I as a conscientious objector and with his penchant for younger men. Fancy-dress parties such as the one Rylands remembered often served to mark birthdays but also were thought appropriate to celebrate artistic accomplishments, such as the opening of exhibitions. Bloomsbury’s fancy dress, however, offered more than a brief opportunity for revelry and celebration. Virginia Woolf saw in costumes a chance to abandon her normal self for an evening, and she embraced fancy dress that did not flatter her normal traits and features but deviated quite far from them. This sartorial practice influenced one of Woolf’s best-known novels, Orlando, which contains photographs of sitters clad in costumes and employs a model of character (and thus of self) based on principles that Woolf came to understand through wearing fancy dress.79 Dorothy L. Sayers, like Woolf, celebrates the transformative power of costume but only when it is employed by aristocratic, extremely wealthy, and cultured individuals.

Virginia Woolf and her sister, Vanessa Bell, wore fancy dress on many documented occasions, and their choices suggest that they enjoyed the way in which costumes could contrast with, instead of enhance, their everyday selves. Ironically, the best documentation of their costumes comes from people who did not appreciate the sisters’ decisions. The most detailed record of the Artists Revels of 1909, for example, comes from the pen of Ottoline Morrell, who was disappointed in their selections: “Vanessa’s Madonna-like beauty surely could have found a happier alias than that of a Pierrot, and Virginia [Stephen] was hardly suited to pose as Cleopatra, whose qualities, as I had imagined them, were just those that Virginia did not possess.”80 Morrell’s comments may seem merely frivolous, but they point to a fundamental disagreement about the proper relationship between costume and wearer: Should fancy dress enhance one’s persona, thus rendering aspects of the self highly visible, or should it contrast with one’s “self,” thus complicating and perhaps transforming it in the process? Morrell clearly embraced the former view, while the sisters seemed to be leaning toward the latter. While Virginia Stephen did not record her reasons for choosing to attend as Cleopatra, it is possible that she selected the costume precisely because it would materialize qualities she did not possess but could put on, albeit temporarily.

Other costumes worn by Woolf and Bell similarly suggest that the sisters reveled in the opportunity to transform (and not simply beautify) themselves through fancy dress. In “Am I a Snob?” Woolf remembers her costume—and the reaction to it—for the ball to celebrate the end of the Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition in 1912. She and Bell “dressed ourselves up as Gauguin pictures and careered round Crosby Hall. Mrs. Whitehead was scandalized. She said that Vanessa and I were practically naked.”81 No pictures of these costumes survive, but the sisters’ transformation was racial and sexual: if they were not in fact “practically naked,” they must have displayed more flesh than was common in the period; and by disguising themselves as Tahitian women, they would have complicated their racial and national identities. It is instructive to compare the Gauguin-inspired costumes with those donned in the Dreadnought hoax of 1910, which similarly involved racial and sexual transgression, particularly for Virginia Stephen, the lone woman who participated.82 While the Dreadnought costumes concealed the wearers’ English identities—disguised them as someone else, however fictional—the Gauguin-themed costumes complicated the sisters’ selves by, in Woolf’s words, filtering them through the “variegated lights” of Postimpressionism.83 Fancy dress allowed Virginia and Vanessa to materialize artistic commitments at odds with the status of respectable British middle-class virgin and wife, respectively.

There are intermittent references to additional fancy-dress parties in the sisters’ diaries and letters throughout the 1920s and 1930s. Although their costumes are not always described, these documents recall the impact of wearing fancy dress in glowing terms. In January 1923, Woolf recalled a costume party as stimulating and transformational: “Suppose one’s normal pulse to be 70; in five minutes it was 120: & the blood, not the sticky whitish fluid of daytime, but brilliant & prickling like champagne.”84 In her “mother’s laces,” Woolf thought of Shakespeare and concluded that he “would have liked us all tonight.”85 On this occasion and others, fancy dress created sparkling new selves for Woolf and Bell. In January 1930, for example, they wore costumes to an “Alice in Wonderland” party held to celebrate Angelica Bell’s birthday. This is the only Bloomsbury fancy-dress event to have been photographed, though the image is, unfortunately, out of focus (figure 3.6). Virginia Woolf was disguised as “the March hare” and wore white as well as “a pair of hare’s ears, and a pair of hare’s paws.”86 Leonard Woolf dressed as the Carpenter; Bell’s costume was not recorded.

Like her earlier costumes, which had allowed Woolf to put on a new role for a night, her fancy dress—“a hare…and mad at that”—left her “encouraged by the extravaganza.”87 As she wrote to Clive Bell, she “turned…and tapped Dotty on the nose” and complained that “she flared up like a costermonger; damned my eyes;…; and swore that I had wiped all the powder from her face.”88 Dorothy Wellesley’s costume is not identified in Woolf’s letter, but it obviously did not cover her face, as she wore standard makeup with it. Her reaction to Woolf’s gesture suggests that she shared Morrell’s standards for fancy dress, which she regarded as enhancing, not mocking or ironizing, female beauty. March hares were not compatible with these criteria.

Throughout the 1930s, Woolf continued to enjoy the play with identity that fancy dress afforded.89 As she would write of a costume party held in 1939, fancy dress offered “a kind of liberation…, tipsiness & abandonment at not being one’s usual self.”90 This personal experience with fancy dress doubtless informed Woolf’s increasingly radical approach to character, which surfaces in Orlando’s suggestion that there may not be a “self” under a costume—that costume and self are one. While scholars have noted that Woolf’s fantastical “biography” provides a literary example of Judith Butler’s theory of gender performance,91 I argue that Woolf’s novel depicts identity itself as a performance. By means of fancy dress, Woolf came to see selfhood as assembled by the cooperation of person and material objects: Orlando argues that selves are multiple and dependent on what one wears.

Of course, this isn’t to say that Woolf regarded all fancy dress as liberatory. Her novel Jacob’s Room uses costume to highlight the difference between the educational and economic status of men and women. As the impoverished and lovelorn Fanny Elmer struggles to make sense of Tom Jones, she muses, “There is something…about books which if I had been educated I could have liked—much better than ear-rings and flowers, she sighed, thinking of the corridors at the Slade and the fancy-dress dance next week. She had nothing to wear.”92 Elmer’s inability to appreciate Henry Fielding’s novel—or her inability to like it better than fancy dress—rests squarely on her inadequate learning, and Woolf aligns women with the pleasures of costumes and men with the benefits of higher learning throughout this section of the novel. Although Jacob Flanders, the novel’s protagonist and Elmer’s love interest, briefly goes along with plans for the fancy-dress ball, “and though he looked terrible and magnificent and would chuck the Forest, he said, and come to the Slade, and be a Turkish knight or a Roman emperor (and he let her blacken his lips and clenched his teeth and scowled in the glass), still—there lay Tom Jones.”93 Jacob’s Room thus represents fancy dress as an example of the unsatisfying pleasures available to the uneducated Elmer, an artist’s model for whom fancy dress serves as a transient—and ultimately disappointing—form of self-expression.

The contrast between Jacob’s Room and Orlando, published a mere six years later, could not be starker. In Woolf’s later work, she offers to a character the “liberation…, tipsiness & abandonment at not being one’s usual self” that costume allows,94 and Orlando’s “selves” are achieved not only through the novel’s famous sex change but through an attitude toward clothing that treats all garb as fancy dress. In other words, while Orlando contains no textual references to fancy dress per se, it displays what Woolf most valued in such costumes: the ability to be not disguised but different from what one had been before. Orlando all but dismantles depth ontology, as Woolf’s main character is (almost entirely) what he or she wears. Things emerge not as more powerful than people but as mutually constitutive, and ontological distinctions between self and surface are largely abandoned.95 This experiment offers a radical contrast to the texts discussed in the previous section; at the same time, it is important to remember that only one extraordinary character enjoys the power to make things do her bidding.

The illustrations that pepper Orlando underline the ways in which fancy dress shaped Woolf’s attitude toward her character. These images, readers and scholars have long understood, include a range of media: reproductions of paintings from Vita Sackville-West’s childhood home, Knole; society portraits and snapshots of Sackville-West; and photographs taken expressly for publication in Orlando. The last category includes images of Woolf’s niece Angelica Bell and Sackville-West in fancy dress. Vanessa Bell, who took these photographs, and her sitters assembled the individual costumes; Sackville-West, for example, was instructed to bring “your curls and clothes” to one photo shoot.96 As R. S. Koppen has noted, “What is striking is the degree of care taken in the assembling and production of these illustrations, and at the same time the fun that was obviously generated by the fancy dress and the staging involved.”97 The costumes depicted in these photographs are far from historically accurate—”Orlando about the year 1840” is represented by Sackville-West in a “checked wool skirt, an eastern shawl and a garden hat”98—but they point generally to the investment of Woolf (and the Bloomsbury circle) in fancy dress and specifically to the ways in which this sartorial form influenced the novel. In the pages of Woolf’s mock biography, Angelica, for example, is “The Russian Princess as a Child”; while readers who were intimates with the Woolfs and Bells would have known that she was also a specific young girl, that knowledge would be filtered by the transformation effected by the costume. In other words, within the pages of the novel, this illustration works a kind of material magic, demonstrating the power of fancy dress to offer new forms of identity, if for only an evening or, in Orlando, the time it takes to turn a page.

The character of Orlando pays little attention to clothing until after the dramatic scene of transmogrification that turns him into a woman. The narrator’s response to that metamorphosis initially suggests that Orlando has an essential self that is entirely independent of all material trappings, including her sexed body: “Orlando had become a woman—there is no denying it. But in every other respect, Orlando remained precisely as he had been. The change of sex, though it altered their future, did nothing whatever to alter their identity.”99 This description, which insists that Orlando’s identity remains intact after the sex change, seems to affirm depth ontology, positing a self so deeply rooted that even becoming a woman cannot alter it. Orlando’s face remains “practically the same,” and “her memory…went back through all the events of her past life without encountering any obstacle.”100 As Orlando’s life as a woman unfolds, however, the narrator suggests that it is less what is in the body than what is on it that makes Orlando who she is.

Although the narrator’s struggle over the relationship between clothing and self will be familiar to many readers, revisiting that quandary through Woolf’s experience of fancy dress and the novel’s photographs of costumed figures sheds new light on the material constitution of Orlando’s identity. When Orlando is in England and dressed as a woman, the narrator muses that the character’s behavior had changed and that “the change of clothes had, some philosophers will say, much to do with it. Vain trifles as they seem, clothes have, they say, more important offices than merely to keep us warm. They change our view of the world and the world’s view of us.”101 This line of reasoning suggests that the things on a body make a person who he or she is. It is precisely this aspect of fancy dress, a form of garment worn for events premised on changing “the world’s view of us,” that compelled Woolf and her contemporaries. The narrator continues, “There is much to support the view that it is clothes that wear us and not we them; we may make them take the mould of arm or breast, but they mould our hearts, our brains, our tongues to their liking.”102 This mutual constitution of object and person, and Woolf’s personification of clothing, positions garments as more than inert matter: if they can change heart, brain, and tongue, they assemble personality, self, and identity rather than reflect an interior being.

After floating the theory that “clothes make the (wo)man” in a profound sense, Woolf’s narrator abandons this line of reasoning. This retreat reminds the reader not only of the narrator’s conservative bent—he or she is, after all, the persona who can scarcely behold the sex change—but also of the appeal of depth ontology, which rigidly separates person from object. The narrator notes, “That is the view of some philosophers and wise ones, but on the whole, we incline to another. The difference between the sexes is, happily, one of great profundity. Clothes are but a symbol of something hid deep beneath.”103 The desire that identity and personality be a stable entity “hid deep beneath” both garments and body points to the investment in depth ontology felt by Woolf’s narrator and, as we have seen, many of her contemporaries. The popular examples examined earlier, which direct laughter or fear at costumes that aim to change their wearers, underline a collective unease with the idea that, in Miller’s words, “clothing plays a considerable and active part in constituting the particular experience of the self, in determining what the self is.”104 Although “philosophers and wise ones” like Miller may think otherwise, Woolf’s narrator and many of her contemporaries insist on locating the self inside rather than outside characters. The narrator thus defends against the creeping suspicion that identity is more changeable and random than purposeful.

Orlando’s biographer soon realizes that this defense of depth ontology is impossibly flimsy. After positing clothes as symbol, the narrator confronts “a dilemma. Different though the sexes are, they intermix. In every human being a vacillation from one sex to the other takes places, and often it is only the clothes that keep the male or female likeness, while underneath the sex is the very opposite of what is above.”105 Here, Woolf’s use of the word “sex” (which she does not distinguish from “gender”) obfuscates the precise changes “underneath” clothing. In the world of Orlando, it seems perfectly possible that the narrator means that miraculous sex changes occur daily; less fantastically, the narrator may be speculating on gender identity or sexual orientation. Regardless of how the term “sex” is employed in this passage, what most matters is that “clothes…keep the male or female likeness”—clothes assemble the sex of the person who wears them. Because sex was such a central component of self in Woolf’s day (as, indeed, in our own), the narrator concludes that the self may be so transitory—so vacillating—that humans need garments to materialize the appearance of a stable identity. According to this view, clothing provides a consistency that personality, identity, sex, and self lack.

As Woolf’s mock biography continues, the fancy-dress principle—the concept that clothing confounds ontology by making persons through things—emerges in full flower as all of Orlando’s clothing comes to seem costume. As the eighteenth century unfolds, the narrator finds it difficult to keep track of Orlando because “she found it convenient to change frequently from one set of clothes to another.”106 These continual changes of clothing go beyond the normal sartorial contortions that an eighteenth-century lady would have experienced; as the narrator observes, “She had, it seems, no difficulty in sustaining the different parts, for her sex changed far more frequently than those who have worn only one set of clothing can conceive.”107 Orlando’s frequent transformations illuminate the difference between Woolf’s character and historical figures in the eighteenth or even the twentieth century; instead of having everyday garments and special-occasion ensembles—instead of wearing a costume that filters and reconstructs the self for only evening parties and performances—every garment that Orlando dons constructs a different self. Woolf thus plays with the possibility that her character may not be her “usual self”108—may not have a “usual self”—because clothing lets her sustain a range of selves. These selves, and the costumes that construct them, are, moreover, explicitly queer: “From the probity of breeches she turned to the seductiveness of petticoats and enjoyed the love [emotional or physical, the narrator does not say] of both sexes equally.”109 Freed from a stable, singular identity, Orlando is also freed from a stable (that is, confining) sexuality—multiple selves increase “the pleasures of life,”110 reports the narrator.

The narrator’s description of some of those selves demonstrates that clothing constructs not only sex and sexual orientation (always important in Orlando) but distinct beings. I quote at length to give the flavor of the garments the character wears and the selves they enable:

So then one may sketch her spending her morning in a China robe of ambiguous gender among her books; then receiving a client or two (for she had many scores of suppliants) in the same garment; then she would take a turn in the garden and clip the nut trees—for which knee breeches were convenient; then she would change into a flowered taffeta which best suited a drive to Richmond and a proposal of marriage from some great nobleman; and so back again into town, where she would don a snuff-coloured gown like a lawyer’s and visit the courts to hear how her cases were doing…; and so, finally, when night came, she would more often than not become a nobleman complete from head to toe and walk the streets in search of adventure.111

Thus a reader sees that Orlando wears clothing to assemble who she is at different times: a reader, a wealthy landowner, a gardener, a potential marital partner, a legal petitioner, and a nobleman. Some, but not all, of these selves are sexed and gendered; some, but not all, of Orlando’s clothing is dictated by specific physical activities. The novel relishes the thought that all clothing may be fancy dress, that one can be coherent and yet have the qualities of one’s being constantly change to suit the moment. Orlando’s clothes, like fancy dress, do not disguise; they multiply possibilities and suggest that one is in part what one wears.

Orlando finds such quick changes difficult to sustain after the eighteenth century. The nineteenth century influences her to marry, and Orlando subsequently becomes a mother, but these life events are significantly motivated by the clothing she adopts. As she muses on the alterations the nineteenth century has wrought, the character thinks, “Tomorrow she would have to buy twenty yards or more of black bombazine, she supposed, to make a skirt. And then (here she blushed), she would have to buy a crinoline, and then (here she blushed) a bassinette.”112 Orlando’s blushes reveal the character’s (Victorian) modesty about the pregnancy that a crinoline may conceal, but the novel’s description makes it appear that bombazine and crinoline are enough to impregnate the character: clothing implants the idea of motherhood and facilitates entry into that state. The biographer indeed notes that, in Orlando’s case, “the crinoline [was] blushed for before the husband” and blames “the irregular life she had lived before.”113 Such attempts to rationalize Orlando’s behavior do not conceal the fact that she, in the nineteenth century, as before, dresses for the person she wants to become—that she designs a costume that will mold her heart, brain, tongue, and even uterus as long as she wears it.114 Although this dress will create an Orlando seemingly different from the eighteenth-century character—she becomes a wife and a mother—readers soon see how little these changes influence her. Her child, a boy, is twice mentioned by the narrator, and her husband remains with Orlando only briefly.

The conclusion of Woolf’s novel most clearly depicts the model of identity that Orlando’s many costume changes impart. This section posits each “human spirit” as a collection of selves that surface in different conditions.115 Orlando “had a great variety of selves to call upon,”116 and the narrator lists some of them, each of which requires a specific set of clothes to adopt and abandon. As the novel embraces a model of identity that is changeable, deliberate, and transitory, the narrator briefly alludes to a “Captain self, the Key self, which amalgamates and controls” all others.117 Here, the novel appears to advance a version of depth ontology, but the Key self refuses to arrive for some time. As Orlando switches from self to self, from memory to memory, she may seem incoherent and (as some have argued) ill, but what Woolf instead depicts is the instability of self when it is not dressed for a particular part.118

Orlando finally settles—for the space of the book’s final pages, if not for all time—on a particular self only through the memory of another character, who is identified by his clothes. She recalls a figure who may have been Shakespeare: “ ‘[H]e sat at Twitchett’s table,’ she mused, ‘with a dirty ruff on.’ ”119 This memory, constructed as it is through place and dress, launches Orlando into a recollection of her lifelong work as an author, and the narrator describes the impact as “the addition of this Orlando, what is called, rightly or wrongly, a single self, a real self.”120 In this passage, Orlando’s biographer once more refuses to specify what he or she believes—the passive voice and “rightly or wrongly” identifies only possibilities—but the actions of the character demonstrate that this self, too, needs a costume to remain “single” and “real.” At this moment, Orlando again changes her clothes, this time adopting “a pair of whipcord breeches, and leather jacket.”121 The breeches are, perhaps, incidental to the character’s identity as author, but the jacket importantly features a pocket large enough to contain a bound copy of The Oak Tree, Orlando’s prize-winning verse.122 In these garments, the author tours her house, walks to (and sits underneath) the tree that inspired her verses, and muses about her long history. In the novel’s final moments, even the character’s accessories inflect a particular self: Orlando helps her husband return to her by bearing her necklace “so that her pearls glowed” and “burnt like a phosphorescent flare in the darkness.”123 Through her breeches, jacket, and finally pearls, Orlando is able to put together the specific self that the reader encounters in the novel’s present day; as the narrative concludes, one can only wonder what dress, what self, Orlando will adopt in the speculative life that continues beyond the final page of the book.