Jung-min Lee and Elise C. Kohn

BACKGROUND AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Ovarian cancer is the most common cause of gynecologic cancer death, and fifth leading cause of cancer death in women in the United States.

Ovarian cancer is the most common cause of gynecologic cancer death, and fifth leading cause of cancer death in women in the United States.

In 2016, approximately 22,280 cases were diagnosed in the United States, resulting in 14,240 deaths, a pattern that has been relatively stable for at least two decades.

In 2016, approximately 22,280 cases were diagnosed in the United States, resulting in 14,240 deaths, a pattern that has been relatively stable for at least two decades.

The median age at diagnosis is 63, with approximately 70% of new diagnoses at or beyond 55 years of age.

The median age at diagnosis is 63, with approximately 70% of new diagnoses at or beyond 55 years of age.

Lifetime risk of developing an epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is approximately 1 in 70 (1.4%). It can be as high as 60% and 30% for patients with germline deleterious BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation (gBRCAm), respectively.

Lifetime risk of developing an epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is approximately 1 in 70 (1.4%). It can be as high as 60% and 30% for patients with germline deleterious BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation (gBRCAm), respectively.

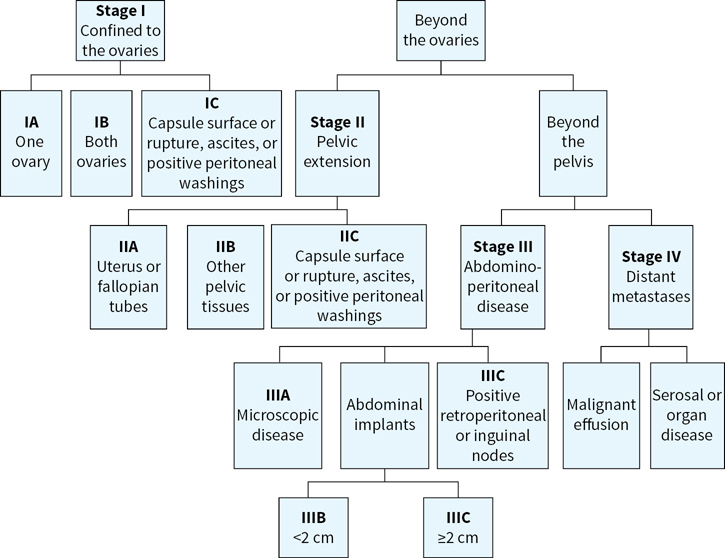

The majority of EOCs (~75%) are diagnosed at advanced stage (III/IV; Fig. 17.1).

The majority of EOCs (~75%) are diagnosed at advanced stage (III/IV; Fig. 17.1).

The EOC overall 5-year survival is 45%, with >75% of early-stage (stage I) patients alive at 5 years.

The EOC overall 5-year survival is 45%, with >75% of early-stage (stage I) patients alive at 5 years.

FIGURE 17.1 A flow chart for ovarian cancer the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging. Patients are staged at diagnosis based on the extent of the spread of the ovarian cancer. Correct staging is critical as it impacts treatment decisions.

MOLECULAR AND CELLULAR PATHOLOGY

Epithelial histology accounts for 90% of all ovarian cancers.

Epithelial histology accounts for 90% of all ovarian cancers.

EOCs are graded using a two-type grade classification system of low grade and high grade (and ungraded clear cell).

EOCs are graded using a two-type grade classification system of low grade and high grade (and ungraded clear cell).

EOCs consist of several molecular-pathological entities:

EOCs consist of several molecular-pathological entities:

•Low malignant potential (borderline; LMP) neoplasms account for approximately 15% of EOCs. They are defined by limited layers of stratified epithelial proliferation, without ovarian stromal invasion. They can progress to invasive low-grade serous malignancies.

•Low-grade serous ovarian cancer (LGSOC) may be found concomitant and/or in continuity with serous LMP cancers. BRAF V600E and KRAS mutations can be found in up to 70% of serous LMP tumors with the frequency dropping to approximately 40% in invasive low-grade cancers. LGSOC is more slowly growing and has been inferred to be less susceptible to cytotoxic chemotherapy.

•Clear cell and low-grade endometrioid cancers may be contiguous and progress from ovarian endometriosis. They share up to 40% somatic mutation in ARID1a, and may be found as a mixed subtype. Clear cell cancers are more aggressive and have a worse outcome in early stage than other non–high-grade serous EOC.

•Primary mucinous and transitional cell carcinomas. These are extremely rare. True mucinous carcinoma of the ovary must be separated anatomically and histopathologically from mucinous cancers of other origins, especially appendiceal malignancies. Nearly 80% of mucinous ovarian cancers have KRAS mutation. If there is extension beyond the ovary, the appendix must be cleared of malignancy for a pathologic conclusion of mucinous carcinoma of the ovary.

•High-grade serous or endometrioid ovarian cancer (HGSOC) are now shown to originate in the serous epithelium of the fallopian tube.

•HGSOC are more aggressive and disseminate early within the abdominal cavity upon presentation, although parenchymal invasion is often a late event.

•HGSOC, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal carcinomas are now considered a single clinical entity (“EOC”).

•Mixed Muellerian malignant tumor or carcinosarcoma is a variant of EOC with sarcomatous appearing histology and carcinomatous molecular changes. It appears to be an aggressive variant of HGSOC.

The remaining 10% of ovarian cancers consist of sex-cord stromal or germ cell histology.

The remaining 10% of ovarian cancers consist of sex-cord stromal or germ cell histology.

•Sex-cord stromal tumors are mesenchymal and include granulosa cell and Sertoli–Leydig cell tumors. They are most often benign and can begin at post puberty. Granulosa cell tumors account for 70% of sex-cord stromal tumors and may produce estrogen. Sertoli–Leydig cell tumors may produce testosterone.

•Germ cell neoplasms include dysgerminoma, teratoma, and yolk sac (endodermal sinus) tumors. Malignant germ cell tumors are treated similarly to testicular cancer.

RISK FACTORS

Table 17.1 lists risk factors for ovarian cancer.

Table 17.1 lists risk factors for ovarian cancer.

gBRCAm women have high lifetime risk for the development of EOC, up to 60% for BRCA1 and 40% for BRCA2, respectively.

gBRCAm women have high lifetime risk for the development of EOC, up to 60% for BRCA1 and 40% for BRCA2, respectively.

Women with a strong family history without an identified deleterious germline mutation also have a high lifetime risk for the development of EOC.

Women with a strong family history without an identified deleterious germline mutation also have a high lifetime risk for the development of EOC.

TABLE 17.1 Risk Factors for Ovarian Cancer

Increased Risk |

Increasing age

|

Genetic factors

|

Reproductive factors

|

Environmental factors

|

Decreased Risk |

Reproductive factors

|

Gynecologic surgery

|

PREVENTION

The use of oral contraceptives is protective against EOC for the general population. Increasing duration of use is associated with larger reductions in EOC risk.

The use of oral contraceptives is protective against EOC for the general population. Increasing duration of use is associated with larger reductions in EOC risk.

Risk reduction salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) has been shown to reduce the lifetime risk of ovarian/tubal/peritoneal cancer to less than 5% in high-risk women. RRSO is recommended for high-risk women defined as those with familial ovarian cancer syndromes, and/or gBRCAm. Surgery is recommended after completion of childbearing and, where feasible, approximately 10 years earlier than the age of diagnosis of the youngest affected family member.

Risk reduction salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) has been shown to reduce the lifetime risk of ovarian/tubal/peritoneal cancer to less than 5% in high-risk women. RRSO is recommended for high-risk women defined as those with familial ovarian cancer syndromes, and/or gBRCAm. Surgery is recommended after completion of childbearing and, where feasible, approximately 10 years earlier than the age of diagnosis of the youngest affected family member.

The use of salpingectomy without oophorectomy remains controversial and untested. If used, it should be considered in women of childbearing potential who wish to have children after which oophorectomy should be done.

The use of salpingectomy without oophorectomy remains controversial and untested. If used, it should be considered in women of childbearing potential who wish to have children after which oophorectomy should be done.

RRSO has been shown to decrease the risk of breast cancer up to 50% in gBRCAm carriers.

RRSO has been shown to decrease the risk of breast cancer up to 50% in gBRCAm carriers.

RRSO is not recommended for women at average risk.

RRSO is not recommended for women at average risk.

SCREENING

The FDA released a formal recommendation against using any screening tests for ovarian cancer on September 7, 2016.

The FDA released a formal recommendation against using any screening tests for ovarian cancer on September 7, 2016.

The 2012 Reaffirmation Recommendation Statement of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reiterated its recommendation against screening for EOC in women who are asymptomatic and without known genetic mutations that increase its risk.

The 2012 Reaffirmation Recommendation Statement of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reiterated its recommendation against screening for EOC in women who are asymptomatic and without known genetic mutations that increase its risk.

•Mounting evidence suggests that annual screening with transvaginal ultrasonography (TVU) and serum cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) does not reduce mortality. High false-positive rates leading to intervention are associated with subsequent harm, such as unnecessary surgical intervention.

Women with a family history of breast/ovarian cancer should be offered genetic counseling and genetic testing if interested.

Women with a family history of breast/ovarian cancer should be offered genetic counseling and genetic testing if interested.

Familial ovarian cancer syndrome patients and known gBRCAm carriers who have not undergone RRSO may be offered screening consisting of a pelvic examination, TVU, and a CA-125 blood test every 6 months beginning between the ages of 30 and 35 years, or 5 and 10 years earlier than the earliest age of first EOC diagnosis in the family. There are no data demonstrating survival benefit of screening high-risk patients.

Familial ovarian cancer syndrome patients and known gBRCAm carriers who have not undergone RRSO may be offered screening consisting of a pelvic examination, TVU, and a CA-125 blood test every 6 months beginning between the ages of 30 and 35 years, or 5 and 10 years earlier than the earliest age of first EOC diagnosis in the family. There are no data demonstrating survival benefit of screening high-risk patients.

Women with high-risk families in whom deleterious mutations are not found (BRCA1, BRCA2 or Lynch syndrome–associated genes) can be referred for panel testing for lower abundance deleterious germline mutations. Absent such testing and confirmation of a genetic risk, such women are treated similarly to those in whom genetic risk is identified. RRSO is recommended; absent RRSO, screening as for high-risk women is reasonable.

Women with high-risk families in whom deleterious mutations are not found (BRCA1, BRCA2 or Lynch syndrome–associated genes) can be referred for panel testing for lower abundance deleterious germline mutations. Absent such testing and confirmation of a genetic risk, such women are treated similarly to those in whom genetic risk is identified. RRSO is recommended; absent RRSO, screening as for high-risk women is reasonable.

SERUM BIOMARKERS

CA-125 is a high-molecular-weight glycoprotein and marker of epithelial tissue turnover produced by ovarian, endocervical, endometrial, peritoneal, pleural, colonic, and breast epithelia.

CA-125 is a high-molecular-weight glycoprotein and marker of epithelial tissue turnover produced by ovarian, endocervical, endometrial, peritoneal, pleural, colonic, and breast epithelia.

•CA-125 is increased in approximately 50% of early-stage and >90% of advanced-stage serous and endometrioid EOC.

•Specificity of CA-125 for ovarian cancer is poor. It can be increased in many benign conditions, such as endometriosis, first trimester pregnancy, pelvic inflammatory disease, uterine fibroids, benign breast disease, cirrhosis, and in response to pleural or peritoneal effusions of any cause, and other epithelial malignancies.

•CA-125 is FDA approved for use as a biomarker for monitoring EOC response to treatment and recurrence. It is neither approved nor recommended for screening.

•The reliability of following CA-125 concentrations during molecularly targeted therapy is unknown.

Human epididymis protein 4 (HE4) is a glycoprotein also expressed in some EOC. It is increased in >50% of tumors that do not also express CA-125. HE4 testing is FDA approved as a biomarker for monitoring EOC recurrence and response to treatment. It is neither approved nor recommended for screening.

Human epididymis protein 4 (HE4) is a glycoprotein also expressed in some EOC. It is increased in >50% of tumors that do not also express CA-125. HE4 testing is FDA approved as a biomarker for monitoring EOC recurrence and response to treatment. It is neither approved nor recommended for screening.

DIAGNOSIS AND EVALUATION

EOC is not a silent disease. Symptoms are present, though nonspecific.

EOC is not a silent disease. Symptoms are present, though nonspecific.

Several studies suggest usefulness of a Symptom Index Tool to identify women who may have EOC: new (within 1 year) and persistent (more than 12 times/month) pelvic/abdominal pain, increased abdominal size/bloating, difficulty eating/feeling full, and urinary urgency/frequency should trigger evaluation by a gynecologic oncologist.

Several studies suggest usefulness of a Symptom Index Tool to identify women who may have EOC: new (within 1 year) and persistent (more than 12 times/month) pelvic/abdominal pain, increased abdominal size/bloating, difficulty eating/feeling full, and urinary urgency/frequency should trigger evaluation by a gynecologic oncologist.

Stromal tumors can produce virilization, precocious puberty, amenorrhea, and/or postmenopausal bleeding, depending on patient age, and type and amount of ectopic hormone produced.

Stromal tumors can produce virilization, precocious puberty, amenorrhea, and/or postmenopausal bleeding, depending on patient age, and type and amount of ectopic hormone produced.

The preoperative workup of a patient with a suspected ovarian malignancy is summarized in Table 17.2.

The preoperative workup of a patient with a suspected ovarian malignancy is summarized in Table 17.2.

Early referral to a gynecologic oncologist is strongly recommended.

Early referral to a gynecologic oncologist is strongly recommended.

Diagnosis can be made by laparoscopy, or biopsy, especially in situations where surgical extirpation may not be considered optimally done and neoadjuvant therapy is being considered. The extent and quality of surgical debulking has a prognostic role.

Diagnosis can be made by laparoscopy, or biopsy, especially in situations where surgical extirpation may not be considered optimally done and neoadjuvant therapy is being considered. The extent and quality of surgical debulking has a prognostic role.

TABLE 17.2 Workup for Patient with a Pelvic Mass and/or Suspected EOC

History of present illness, attention to issues related to Symptom Index Tool (see text) |

Family history |

Gynecologic history |

Physical examination, including cervical scraping for PAP smear |

Labwork: full panels with added:

|

Imaginga

|

a Value of PET and MRI uncertain; PET/CT interpretability may be compromised by lack of IV and oral contrast.

TREATMENT

Surgery

Proper EOC diagnosis and staging require tissue.

Proper EOC diagnosis and staging require tissue.

Standards of care are now either primary debulking or tissue sampling for diagnosis with interim debulking after initiating neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Standards of care are now either primary debulking or tissue sampling for diagnosis with interim debulking after initiating neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

•Primary debulking surgery includes laparotomy with en bloc TAH/BSO tumor removal, abdominal fluid sampling, tumor debulking, and pathologic assessment of the abdomen, including diaphragms, paracolic gutters, and serosal surfaces. Unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy can be considered in women with stage I grade 1/2 tumors who wish to preserve fertility. Completion of salpingo-oophorectomy is recommended upon completion of child-bearing.

•Interval debulking uses the same complete extent of surgery, but occurs after 3–4 cycles of neoadjuvant therapy.

•The goal of surgery, whether primary or interval, is “R0” or no visible disease. Optimal debulking remains no lesion greater than 1cm residual in largest diameter. Data indicate better outcome for women undergoing surgical debulking by a gynecologic oncologist.

Stage I disease with favorable prognostic features (grade 1/2, stage IA/B, non–clear cell histology) can be treated by surgery alone.

Stage I disease with favorable prognostic features (grade 1/2, stage IA/B, non–clear cell histology) can be treated by surgery alone.

Initial Chemotherapy

The current international consensus standard of care for all stage IC and stages II–IV is adjuvant chemotherapy. That chemotherapy should include a platinum and a taxane and should be administered for 6 cycles, with fewer cycles considered acceptable for IC (GOG-157).

The current international consensus standard of care for all stage IC and stages II–IV is adjuvant chemotherapy. That chemotherapy should include a platinum and a taxane and should be administered for 6 cycles, with fewer cycles considered acceptable for IC (GOG-157).

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) can be administered with interval debulking for advanced-stage patients. In such cases the total neoadjuvant and adjuvant exposure should be 6 to 8 cycles of combination chemotherapy. NACT with interval debulking has been shown to be noninferior to primary debulking surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) can be administered with interval debulking for advanced-stage patients. In such cases the total neoadjuvant and adjuvant exposure should be 6 to 8 cycles of combination chemotherapy. NACT with interval debulking has been shown to be noninferior to primary debulking surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy.

Adjuvant chemotherapy remains the recommendation for all histologic types, types I and II, ovarian cancers.

Adjuvant chemotherapy remains the recommendation for all histologic types, types I and II, ovarian cancers.

Combination intraperitoneal/intravenous chemotherapy with platinum and taxane has been shown in numerous trials to be superior to intravenous chemotherapy in optimally debulked advanced stage ovarian cancer patients.

Combination intraperitoneal/intravenous chemotherapy with platinum and taxane has been shown in numerous trials to be superior to intravenous chemotherapy in optimally debulked advanced stage ovarian cancer patients.

Dose-dense paclitaxel/carboplatin therapy is not superior to every 3-week paclitaxel therapy, although it appears that every 3 weekly paclitaxel/carboplatin with bevacizumab is superior to 3 weekly paclitaxel/carboplatin in a post hoc unplanned subset analysis (GOG0262).

Dose-dense paclitaxel/carboplatin therapy is not superior to every 3-week paclitaxel therapy, although it appears that every 3 weekly paclitaxel/carboplatin with bevacizumab is superior to 3 weekly paclitaxel/carboplatin in a post hoc unplanned subset analysis (GOG0262).

NACT and adjuvant chemotherapy regimens are summarized in Table 17.3.

NACT and adjuvant chemotherapy regimens are summarized in Table 17.3.

Paclitaxel and docetaxel have been shown to yield similar outcomes in adjuvant therapy (SCOTROC1).

Paclitaxel and docetaxel have been shown to yield similar outcomes in adjuvant therapy (SCOTROC1).

Carboplatin dosing should be based on the Calvert formula for calculating AUC (http://ctep.cancer.gov/content/docs/Carboplatin_Information_Letter.pdf) dosing of carboplatin [AUC × (GFR + 25)], where GFR is the calculated glomerular filtration rate. If a patient’s GFR is estimated based on serum creatinine measurements by an isotope dilution mass spectrometry (IDMS) method, FDA recommends that physicians consider capping the dose of carboplatin for desired exposure (AUC) to avoid potential toxicity due to overdosing.

Carboplatin dosing should be based on the Calvert formula for calculating AUC (http://ctep.cancer.gov/content/docs/Carboplatin_Information_Letter.pdf) dosing of carboplatin [AUC × (GFR + 25)], where GFR is the calculated glomerular filtration rate. If a patient’s GFR is estimated based on serum creatinine measurements by an isotope dilution mass spectrometry (IDMS) method, FDA recommends that physicians consider capping the dose of carboplatin for desired exposure (AUC) to avoid potential toxicity due to overdosing.

Patients can demonstrate hypersensitivity to paclitaxel with the initial treatment doses due to an anaphylactoid reaction to either the paclitaxel and/or its vehicle. Treatment can be changed to docetaxel, which has a different vehicle if premedication with steroids, H1 and H2 blockers, and/or slower infusion is not sufficiently protective.

Patients can demonstrate hypersensitivity to paclitaxel with the initial treatment doses due to an anaphylactoid reaction to either the paclitaxel and/or its vehicle. Treatment can be changed to docetaxel, which has a different vehicle if premedication with steroids, H1 and H2 blockers, and/or slower infusion is not sufficiently protective.

Platinum hypersensitivity is an anaphylactic, true atopic reaction and presents in later cycles (usually >6 to 10 exposures).

Platinum hypersensitivity is an anaphylactic, true atopic reaction and presents in later cycles (usually >6 to 10 exposures).

•Cisplatin and carboplatin can be cross-substituted, depending on the severity of the reaction. The two agents can have cross-sensitivity because the bioactive moiety is the same.

•Women having a history of platinum allergy may be retreated using slow infusion and premedication with steroids and H1/H2 blockers.

Phase III studies suggest that bevacizumab given during adjuvant carboplatin/paclitaxel and in maintenance prolongs PFS and does not improve OS (GOG218 and ICON7).

Phase III studies suggest that bevacizumab given during adjuvant carboplatin/paclitaxel and in maintenance prolongs PFS and does not improve OS (GOG218 and ICON7).

A meta-analysis of six randomized maintenance trials confirmed no improvement in OS (HR 1.07; 95% CI, 0.91 to 1.27; N = 902). This analysis did not include bevacizumab maintenance therapy.

A meta-analysis of six randomized maintenance trials confirmed no improvement in OS (HR 1.07; 95% CI, 0.91 to 1.27; N = 902). This analysis did not include bevacizumab maintenance therapy.

TABLE 17.3 Adjuvant Chemotherapy and Therapy for Recurrent Disease

Recurrent or Persistent Disease

Recurrence occurs in >80% of stage III/IV patients; recurrent EOC is not curable, although subsequent complete remissions may occur.

Recurrence occurs in >80% of stage III/IV patients; recurrent EOC is not curable, although subsequent complete remissions may occur.

No OS benefit was observed in a RCT comparing early treatment of relapse (based upon increased CA-125 alone) versus observation until symptoms or physical examination trigger disease assessment (MRC OV05/EORTC 55955).

No OS benefit was observed in a RCT comparing early treatment of relapse (based upon increased CA-125 alone) versus observation until symptoms or physical examination trigger disease assessment (MRC OV05/EORTC 55955).

Secondary cytoreduction surgery can be considered for women with recurrence-free intervals of ≥12 months. Its value is being examined in an ongoing phase III trial (GOG-0213).

Secondary cytoreduction surgery can be considered for women with recurrence-free intervals of ≥12 months. Its value is being examined in an ongoing phase III trial (GOG-0213).

Patients with a progression-free interval of ≥6 months have platinum-sensitive disease, although this is a continuum. Second-line platinum-based therapy, single agent or combination, improves survival in women with platinum-sensitive EOC (Table 17.3).

Patients with a progression-free interval of ≥6 months have platinum-sensitive disease, although this is a continuum. Second-line platinum-based therapy, single agent or combination, improves survival in women with platinum-sensitive EOC (Table 17.3).

Recurrence within 6 months of, or progression on, initial platinum-based chemotherapy is defined as platinum-resistant disease.

Recurrence within 6 months of, or progression on, initial platinum-based chemotherapy is defined as platinum-resistant disease.

Sequential single-agent chemotherapy is preferred for platinum-resistant/refractory patients, due to increased toxicity without sufficient evidence of increased benefit of combinations (Table 17.3).

Sequential single-agent chemotherapy is preferred for platinum-resistant/refractory patients, due to increased toxicity without sufficient evidence of increased benefit of combinations (Table 17.3).

Cisplatin/gemcitabine is the one combination chemotherapy regimen with RCT-documented benefit.

Cisplatin/gemcitabine is the one combination chemotherapy regimen with RCT-documented benefit.

Topotecan, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, or weekly paclitaxel with bevacizumab has been shown to be superior on PFS to chemotherapy alone and is licensed in the United States (AURELIA).

Topotecan, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, or weekly paclitaxel with bevacizumab has been shown to be superior on PFS to chemotherapy alone and is licensed in the United States (AURELIA).

Use of Molecularly Targeted Agents

Bevacizumab has modest single agent activity in relapsed ovarian cancer, both platinum sensitive and platinum resistant. It is licensed in the United States and Europe in combination with chemotherapy for platinum-resistant recurrent EOC (Table 17.3).

Bevacizumab has modest single agent activity in relapsed ovarian cancer, both platinum sensitive and platinum resistant. It is licensed in the United States and Europe in combination with chemotherapy for platinum-resistant recurrent EOC (Table 17.3).

PARP inhibitors have demonstrated clinical activity in recurrent EOC with gBRCAm. Olaparib is licensed in the United States for gBRCAm carriers with EOC who had more than three chemotherapy treatment (Table 17.3).

PARP inhibitors have demonstrated clinical activity in recurrent EOC with gBRCAm. Olaparib is licensed in the United States for gBRCAm carriers with EOC who had more than three chemotherapy treatment (Table 17.3).

Clinical trials investigating other targeted agents and immunotherapy either in combination or single agents are ongoing.

Clinical trials investigating other targeted agents and immunotherapy either in combination or single agents are ongoing.

Nonepithelial Ovarian Cancer

Most patients with ovarian germ cell tumors are diagnosed with early-stage disease. Lymph node metastases are rare. Unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, if contralateral ovary is uninvolved, is possible in women who wish to preserve fertility.

Most patients with ovarian germ cell tumors are diagnosed with early-stage disease. Lymph node metastases are rare. Unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, if contralateral ovary is uninvolved, is possible in women who wish to preserve fertility.

BEP chemotherapy (bleomycin/etoposide/cisplatin) should be considered after surgery for germ cell tumors: nondysgerminoma, all but stage I grade 1 disease, and ≥stage II dysgerminoma.

BEP chemotherapy (bleomycin/etoposide/cisplatin) should be considered after surgery for germ cell tumors: nondysgerminoma, all but stage I grade 1 disease, and ≥stage II dysgerminoma.

Most ovarian sex-cord stromal tumors are low grade, early stage at presentation, and have excellent survival. Radiation to gross residual tumors and hormonal therapy with progestin for granulosa cell tumors are considered after surgical resection.

Most ovarian sex-cord stromal tumors are low grade, early stage at presentation, and have excellent survival. Radiation to gross residual tumors and hormonal therapy with progestin for granulosa cell tumors are considered after surgical resection.

Many malignant stromal tumors including granulosa cell tumors produce estrogen; hence, evaluation of the endometrium for malignant change is needed.

Many malignant stromal tumors including granulosa cell tumors produce estrogen; hence, evaluation of the endometrium for malignant change is needed.

Radiation

Radiation therapy (RT) plays a limited role in the treatment of EOC in the United States. Tumors of ovarian and tubal origin are sensitive to RT. RT should be considered for solitary metastases with functional consequences (brain metastases, distal bowel obstruction, bleeding).

Experimental Therapy/Immunotherapy

Patients with ovarian cancer of all stages, at diagnosis and at recurrence, should be encouraged to participate in clinical trials (www.clinicaltrials.gov).

SUPPORTIVE CARE

Common Treatment Toxicities

Myelosuppression: Carboplatin-related bone marrow suppression is a cumulative toxicity (see Chapter 34).

Myelosuppression: Carboplatin-related bone marrow suppression is a cumulative toxicity (see Chapter 34).

Nausea/vomiting: Carboplatin is less emetogenic than cisplatin. Both acute and delayed nausea/vomiting should be monitored and addressed therapeutically (see Chapter 38).

Nausea/vomiting: Carboplatin is less emetogenic than cisplatin. Both acute and delayed nausea/vomiting should be monitored and addressed therapeutically (see Chapter 38).

Renal dysfunction

Renal dysfunction

•Great care should be taken in patients with borderline or abnormal renal function.

•Serum creatinine-based calculations of GFR underestimate renal dysfunction in patients who have received platinums.

Neurotoxicity

Neurotoxicity

•Both platinums and taxanes cause neuropathy. Platinums cause demyelinating injury and can leave long-lasting neuro-residuals. Taxanes and other chemotherapies cause axonal degeneration, which is recoverable.

•Grade 3 to 4 neuropathy can have long-term effects and may require substitution or discontinuation of the offending agent(s). Dose modification of drugs with grade 2 neuropathy may be needed to avoid grade 3 to 4 neuropathy.

Perforation

Perforation

•Bevacizumab causes a 5% to 11% risk of gastrointestinal perforation in EOC patients.

•Possible risk factors for perforation include previous irradiation, tumor involving bowel, and early tumor response.

Obstruction

Obstruction

Patients can present with both bowel and urinary tract obstruction. Presenting symptoms include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, abdominal distention, abdominal and/or back pain, and infrequent bowel movements or urination.

Patients can present with both bowel and urinary tract obstruction. Presenting symptoms include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, abdominal distention, abdominal and/or back pain, and infrequent bowel movements or urination.

Initial treatment for bowel obstruction may be conservative, with bowel rest and nasogastric suction, but many patients will require bypass surgery.

Initial treatment for bowel obstruction may be conservative, with bowel rest and nasogastric suction, but many patients will require bypass surgery.

The aggressiveness of intervention should be balanced with the patient’s prognosis, health status, and goals of care. Management with analgesics, antiemetics, anticholinergics, etc. and/or endoscopic placement of drainage tubes are options for poor surgical candidates.

The aggressiveness of intervention should be balanced with the patient’s prognosis, health status, and goals of care. Management with analgesics, antiemetics, anticholinergics, etc. and/or endoscopic placement of drainage tubes are options for poor surgical candidates.

Occasionally, RT to a particular mass causing obstruction may be appropriate.

Occasionally, RT to a particular mass causing obstruction may be appropriate.

SUMMARY

EOC is the most common cause of death among women with gynecologic malignancies and the fifth leading cause of cancer death in women in the United States.

EOC is the most common cause of death among women with gynecologic malignancies and the fifth leading cause of cancer death in women in the United States.

Limited disease with high-risk features and advanced disease need adjuvant paclitaxel/carboplatin.

Limited disease with high-risk features and advanced disease need adjuvant paclitaxel/carboplatin.

For women who experience a recurrence, the selection of therapy is commonly based upon response to initial platinum-based treatment.

For women who experience a recurrence, the selection of therapy is commonly based upon response to initial platinum-based treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the Intramural Program of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute and the Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program, Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, National Cancer Institute.

Suggested Readings

1.Aghajanian C, Blank SV, Goff BA, et al. OCEANS: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial of chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent epithelial ovarian, primary peritoneal, or fallopian tube cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2039.

2.Armstrong DK, Bundy B, Wenzel L, et al. Intraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:34–43.

3.Bristow RE, Zahurak ML, Diaz-Montes TP, et al. Impact of surgeon and hospital ovarian cancer surgical case volume on in-hospital mortality and related short-term outcomes. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;115:334–338.

4.Burger RA, Brady MF, Bookman MA, et al. Incorporation of bevacizumab in the primary treatment of ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2473.

5.Frederick PJ, Ramirez PT, McQuinn L, et al. Preoperative factors predicting survival after secondary cytoreduction for recurrent ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21(5):831–836.

6.Goff BA, Mandel LS, Drescher CW, et al. Development of an ovarian cancer symptom index. Cancer. 2007;109:221–227.

7.Hunn J, Rodriguez GC. Ovarian cancer: etiology, risk factors, and epidemiology. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;55(1):3–23.

8.Kim G, Ison G, McKee AE, et al. FDA approval summary: olaparib monotherapy in patients with deleterious germline BRCA-mutated advanced ovarian cancer treated with three or more lines of chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(19):4257–4261.

9.Kurman RJ, Shih IM. Pathogenesis of ovarian cancer: lessons from morphology and molecular biology and their clinical implications. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2008;27:151–160.

10.Ledermann J, Harter P, Gourley C, et al. Olaparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1382–1392.

11.Moyer VA. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Ovarian Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Reaffirmation Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(12):900–904.

12.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) Ovarian Cancer. Version 4. 2017. Available at: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/ovarian.pdf. Last accessed on November 14, 2017.

13.Pujade-Lauraine E, Hilpert F, Weber B, et al. Bevacizumab combined with chemotherapy for platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer: The AURELIA open-label randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014.

14.Pujade-Lauraine E, Wagner U, Aavall-Lundqvist E, et al. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin and carboplatin compared with paclitaxel and carboplatin for patients with platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer in late relapse. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(20):3323–3329.

15.Rustin GS, Van der Burg ME, Griffin CL, et al. Early versus delayed treatment of relapsed ovarian cancer (MRC OV05/EORTC 55955): a randomized trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1155–1163.

16.Vergote I, Trope C, Amant F, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy or primary surgery in stage IIIC or IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:943–953.