2

Society of American Indians and the American Indian Institute

This chapter examines Henry Cloud’s activist and intellectual work as a member and founder of the Society of American Indians (SAI). Specifically, it focuses on his efforts to free Geronimo, an Apache, as well as his people—who had been imprisoned after their capture by the U.S. military in 1886—and his efforts to assist the Apaches who chose to stay in Oklahoma with their land-allotment struggle against the federal government.1 It discusses how Henry applied his Ho-Chunk and Yale education to fight for the Apaches. Ultimately, Henry Cloud was a Ho-Chunk intellectual shaped by his Ho-Chunk warrior training. As such, he relied on the SAI as a pantribal hub to support the Apaches’ struggle against the federal government.

In addition, this chapter considers Henry Cloud’s powerful working and marital relationship with Elizabeth Bender Cloud, whom he met in Madison, Wisconsin, at the fourth annual SAI conference. Elizabeth’s childhood on the White Earth Reservation and her white schooling encouraged her to use both virtual and geographic hubs to challenge colonial, assimilationist strategies to separate her from her Ojibwe family. As an Indigenous intellectual, like Henry, Elizabeth was subversive. Although she relied on settler-colonial rhetoric in her writings, she asserted Indigenous perspectives. Similarly, by working both inside and outside of the home, Elizabeth combined an Ojibwe sense of a gendered identity with white notions of domesticity. In fact, Henry and Elizabeth followed Native notions of complementary gender roles: Henry was often away fund-raising for the American Indian Institute, and Elizabeth stayed home and ran the school. Elizabeth and Henry worked together as a “power couple” in a respectful, nonhierarchal Indigenous partnership.

Society of American Indians

Henry Cloud was a founding member of the SAI, a Native pantribal hub of a select group of Native American leaders that supported dialogue regarding Native issues and ideas. Well-known members included Arthur C. Parker (Seneca), the first editor of the American Indian Magazine, and Charles E. Eastman (Dakota), the editor of Collier’s and other eastern magazines, as well as John Oskison (Cherokee), Gertrude Bonnin (Yankton Nakota), Marie Baldwin (Ojibwe), and Rosa B. LaFlesche (Ojibwe). Non-Indians could be associate members, but they could not vote. One prominent non-Indian member was Gen. Richard Henry Pratt.2

By allowing only Native Americans to become full members, the SAI, unlike other Indian reform groups, emphasized that Natives themselves should solve the “Indian problem.”3 Native Americans developed the SAI’s goals and objectives within a general public atmosphere of white reform groups and federally enforced paternalism. For example, the Friends of the Indian, a coalition of white reform groups and individuals, met annually at Lake Mohonk. Their members included the Women’s National Indian Association, the Indian Rights Association, missionaries, and individual white reformers. The Friends of the Indian’s mission was to save Natives from heathenism and transform them from savages to industrious American citizens.4

In October 1911 Cloud helped to organize the SAI’s first annual conference in Columbus, Ohio. He was a member of the advisory board in 1911, 1912, 1917, and 1919 and chaired the board in 1912. From 1911 to 1912 he was also vice president of membership, recruiting Native members and non-Native associate members. As vice president of education in 1916 and 1918, he was the spokesman of the SAI’s educational platform. Finally, from 1915 to 1917 he was a member of the editorial board of the American Indian Magazine, the SAI’s journal.5 The American Indian Magazine was a way for Native intellectuals to support this pantribal hub across geographic distance, maintaining a sense of Native community, identity, and belonging. It was a platform to fight for Indigenous concerns and rights.

Cloud never became president of the SAI, even though there was discussion about the possibility. In a written response to Parker’s 1914 letter about him potentially becoming president, Cloud emphasized his lack of experience, since he was still in his late twenties.6 He also declined because he was busy laboring to found a Native college-preparatory high school in Wichita, Kansas, the American Indian Institute. Cloud’s work with a wide range of Indigenous leaders gave him not only the opportunity to learn from other Natives and discuss Indigenous issues but also the chance to meet my grandmother, Elizabeth, during the aforementioned SAI conference. They eventually had five children: Marion, Anne Woesha (my mother), Ramona, Lillian, and Henry II, who died from pneumonia when he was three years old. Indeed, both Elizabeth and Henry became important leaders in national Native affairs.

Cloud’s Fight for Geronimo and His People

In 1908, while still an undergraduate at Yale University and in his early twenties, Cloud began his successful campaign to release the Chiricahua Apaches from Fort Sill. Cloud heard about the Apache situation from Walter Roe, his informally adoptive, white missionary father, who lived in Colony, Oklahoma, which was about forty miles from Fort Sill. The fact that Cloud learned about the Apache struggle from Roe shows how Cloud used a colonial relationship with a white missionary for Native goals and objectives. His Ho-Chunk warrior training as a member of the Thunderbird Clan taught him the importance of leadership and fighting for his people and certainly must have influenced his decision to support Geronimo and resist the federal government. The Chiricahua Apaches, the last survivors of Geronimo’s people, had valiantly fought official U.S. governmental actions to move them onto increasingly smaller and smaller reservations. But, finally, after evading U.S. government troops for nearly a decade, they were captured in 1886. The Apaches were ultimately taken to Fort Sill, where they resided in terrible housing, were given insufficient rations, and endured severe weather.7 The government initially refused to allow Cloud to work on behalf of the Fort Sill Apaches, since the Apaches had not granted him official permission. Geronimo met with Cloud and gave him authorization to act on their behalf. In 1933 Cloud explained that his training at Yale helped him fight for the Apaches’ release.8 In one of Cloud’s Yale classes on the U.S. Constitution, he studied constitutional principles of attainder and corruption of blood. Article 3, section 3, clause 2, prohibits punishing descendants for the crimes of their ancestors. Cloud argued that by being detained, the children of the Apaches were being punished for their ancestors’ behavior. And so, as a modern-day educated Ho-Chunk warrior, Cloud applied the U.S. Constitution to help him fight for Geronimo and his band’s freedom.

The Dawes Allotment Act was a major strategy to dispossess Natives of millions of acres of land. It followed after the federal government forcibly removed Native Americans from their lands, including five successive Ho-Chunk removals in the 1800s. The Allotment Act was yet another settler-colonial tactic of land dispossession. It attempted to assimilate Natives into U.S. society by changing their communal connection to land to an individual one and by encouraging our Native ancestors to farm land allotments. The government marked the best land as “surplus” and set this land aside for whites. These superior lands had precious minerals and rich agriculture potential, while the land set aside for Natives was often insufficient for agricultural use and did not have water for irrigation. In addition, as discussed in the introduction, this land allotment supported patriarchal notions of the nuclear family: heads of household (meaning men) received 160 acres, married Native women received no land, single adults received 80 acres, and children received 40 acres. This distribution was the case until an 1891 amendment changed the terms so that any Native adult, regardless of family status, would receive 80 acres. The act attacked not only Natives’ communal relationships to land but also their powerful feelings of spiritual, emotional, and physical connection to that land.9 Therefore, it encouraged alternative, nongeographic networks of belonging in the form of Native hubs. Since Indigenous peoples were living apart from one another on individual allotments, these hubs—not based in geographic space—were a way to remain connected to their communal Native sense of identity and gender.

In the following sections, I discuss Henry Cloud’s intellectual and activist efforts to support the Apaches’ land struggle. The Apache prisoners of war, who refused to move to Mescalero, were pressured to leave Fort Sill as a condition of their freedom. At the same time, these Apaches insisted the government give them unused allotment lands from the Kiowa-Comanche-Apache reservation lands near Fort Sill.10 In 1912 and 1913 Henry wrote to the commissioner of Indian Affairs, Cato Sells, to complain that the government had not provided the Apaches with rations and land allotments as promised.11 On October 7, 1913, he met with the Apaches again, who were still imprisoned at Fort Sill, and learned more about the land-allotment struggle. Although government officials had promised the prisoners 160 acres of improved land, they were reneging on this promise: they informed the Apaches they would receive only 80 acres of good agricultural land for each head of household. Cloud also learned why government officials had reduced the number of acres from 160 to 80 acres; they believed the Apaches would lease the land and “debauch themselves with laziness and drink,” a rationale reflecting racist and colonial assumptions of this period. Cloud, after meeting with the Apaches, began crafting a brief to support their fight against the government. On October 16, 1913, Cloud outlined the key facts of the case:

While at Pahuska, Okla. I had a long interview with Special Agent Ellis on the Apache matter. . . .

If the appraisements [of] $3200 for 160 acres is correct, (and such are the average appraisements for 160 acres and 80 acres respectively), the $100,000 is barely sufficient to give 80 acres of good agricultural land for each man, woman and child.

The reading or wording of the law relating to the Apaches is subject to the general allotment act of 1887 where it specifies 160 acres of grazing land or 80 acres of agricultural land for each man, woman and child.

The law leaves the whole matter to the discretion of the Sec. of Int. and Sec. of War as to detailed arrangements. Whatever they (the sec. of war and sec. of Int.) decide upon are called rulings.

[Ernest] Stecker claims that rulings are for either 160 acres of grazing land or 80 acres of agricultural land. If all this is true of course we can only have recourse to new legislation, which is a difficult matter.

Granting that the appraisements are reasonable both to the Kiowa-Comanches and to the Apaches and granting that the law is fixed as specified above, the three men, in my opinion are acting in good faith and are doing the best possible under the circumstances.

But . . . let me state the other side so far as I have come.

In all three hundred thousand dollars were appropriated for the whole Apache band, $200,000 at first and $100,000 later. It does not take, it did not take all of the $200,000 to move and settle the Apaches in Mescalero. A portion of that sum belongs to those who chose to remain at Fort Sill.

This ought to increase the $100,000 immediately available to at least give some of the men at Fort Sill 160 acres of good agricultural land.

The understanding all along has been for 160 acres of good agricultural land.

No farmer unless he irrigates can hope to make a living on 80 acres and it is doubtful on 160 acres.

I have the facts to support B and C and will get the data for condition A.

D) The Indians have proved themselves capable of stock farming. They have had an experience of 25 years or more.

In my telegram to you I did mention the fact that I laid the whole case before [the white reformers and members of the Indian Rights Association] [Samuel] Brosius and [Matthew] Sniffen. . . . The next step for me is to go to Washington and determine how the $300,000 appropriated is to be apportioned and to lay the matter before both the Sec. of Interior and Sec. of War. I shall see the Commissioner about . . . the Fort Sill matter also.12

This letter shows how insightfully Cloud understood key elements of both sides of the case, including the central importance of the Allotment Act of 1887.13 Cloud alludes to the progressive identity of the Apaches, who were choosing to stay in Oklahoma, writing they had “proved themselves capable of stock farming.” In support of the Apaches, Cloud argues that the secretaries of the interior and war ultimately had discretionary power regarding the number of acres the Apaches would receive. In contrast, Ernest Stecker, a government official, argues that the number of acres was fixed; meaning only new legislation could increase the Apaches’ allotment to 160 acres of improved land. At the same time, Cloud agrees with government officials that only 80 acres would be available if indeed the number of acres was set, and the Apaches, Kiowas, and Comanches accepted the land appraisement.

On the Apaches’ side, Cloud challenges government officials’ claim that only $100,000 was available for the purchase of land, arguing that it was insufficient, that there was money left over from the Apaches’ resettlement to Mescalero, and that $300,000 in total had been appropriated. Moreover, this letter demonstrates how hard Henry worked in support of the Apaches, including meeting with government officials and traveling to Washington DC to talk to the secretaries of the interior and war, establishing his place on the national stage as a young man. He was able to combine his Ho-Chunk education—which motivated him to bring Indigenous perspectives to bear on government affairs and taught him oratory skills—with his Yale training, which educated him in colonial strategies of argument and important legal concepts. And Cloud used this dual education to systematically and quickly gather evidence in support of the Apaches’ side of the case—only nine days passed between this letter and his initial meeting with the Apaches. Finally, this letter points to Cloud’s work with the white reform group, the Indian Rights Association, as well as his work with the Society of American Indians.

Cloud, Apaches’ Land Struggle, and the SAI

Cloud brought the Apaches’ land-allotment struggle to the SAI, an important and powerful pantribal hub, so the organization could lobby the federal government on the Apaches’ behalf. The society unanimously supported a brief Cloud wrote, and copies were sent to the secretaries of war and the interior, the commissioner of Indian Affairs, and Congressman C. D. Carter.14 On October 25, 1913, Cloud presented his brief, “The Case of the Fort Sill Apaches Again,” to the SAI and asked for their support. In other words, Cloud shared his Native intellectual ideas with a pantribal hub of Indigenous intellectuals. Through this hub Cloud could receive feedback on his struggle in support of the Apaches from a powerful network of Indigenous intellectuals. Therefore, thanks to the pantribal platform of the SAI, Cloud did not work in an intellectual vacuum but instead gained support and insight from many astute Native intellectuals.

In his Native-centric brief Cloud recounts how an exhausted group of Apaches surrendered in New Mexico in 1886 to Indian scouts rather than to the U.S. military. The Apaches were then forcibly taken to Forts Pickens and Marion in Florida; the Mount Vernon barracks in Alabama; and finally to Fort Sill, Oklahoma. After twenty-seven years of penal servitude, an act of Congress freed the prisoners and then became law on June 30, 1913. Notably, Cloud discusses that $300,000 in total was allocated to help provide land for the Fort Sill Apaches’ resettlement. Ultimately, 176 Apaches resettled in Mescalero, New Mexico, and 80 chose to stay in Oklahoma. Cloud wrote,

At a Council meeting ordered by the Secretary of the Interior on December 1st, . . . 1912, . . . it was proposed to buy 160 acres of improved land for each head of family. . . . 160 acres of good agricultural land at least for each head of a family was the intent and purpose of the law under which these Indians are now being allotted. . . . Actual land conditions . . . make it impossible to make a living on 80 acres. . . . In a letter . . . of October 14th, 1913, the President of the Cameron State of Agriculture . . . a man who knows the region . . . says: “It is my . . . firm belief that the average farmer cannot nor does not make a living on a farm of 160 acres land in this southwestern country. . . . The Apache Indians have been trained as stock-raisers. They have shown fitness for such a life. . . . As to the fitness of these Indians let me read you portions of a letter written by R. A. Bellinger, then Secretary of Interior, to Moses E. Clapp, Chairman Committee on Indian Affairs, United States Senate, under date of February 18th, 1910: “During the fifteen years that the Apaches have lived at Fort Sill, under the supervision of the Military authorities, they have become prosperous, peaceful and contented: they have been taught to care for themselves in large measure as agriculturalists, stock-raisers and mechanics: they individually cultivate considerable pieces of land: they own and brand their own cattle as individuals.”15

Cloud encourages others to prompt action. He shows his sensitivity to the Apache warriors’ experiences by describing their surrender, emphasizing their decision to submit to Native scouts rather than the U.S. military, an allusion to their warrior pride even in defeat. Cloud also employs various rhetorical strategies to argue in support of the Apaches. He recalls the government promise of 160 acres of improved land and the purpose and intent behind the law. He cites an agricultural expert to prove the harsh, unacceptable conditions of the land that was provided, and he cites a military expert to bolster his Native-centric argument about the Apaches’ “fitness” to receive 160 acres of improved land. In fact, Cloud’s use of the words “fitness” and “individually” shows his ability to utilize the colonizers’ categories against them by emphasizing the Apaches’ progressive identity as assimilated Natives living the life the federal government intended for them. Thus, Cloud challenges government officials’ negative, racist assumptions that the Apaches would lease the 160 acres and “debauch themselves with laziness and drink.”16 He ends the brief pleading for the full 160 acres of good agricultural land, summarizing the main points of his argument and reminding the federal government about “treaty stipulations,” “fair dealing,” and “justice.” All these astute rhetorical strategies demonstrate Cloud’s Ho-Chunk intellectual prowess enhanced by his Yale educational training. While at Yale, he studied debate, oratory, and the colonizer’s own arguments. In these ways Cloud indigenized his colonial training to fight for the Apaches and against the federal government.17 And this act of indigenizing shows his subversive Ho-Chunk strategy of doubleness speech. Cloud combined white and Native rhetoric for Indigenous goals and objectives.

Soon after Henry brought the Apaches’ land struggle to the SAI, Elizabeth sent a letter to the society on behalf of Margaret Giard, an Ojibwe, in support of her claim for an allotment on the White Earth Reservation:

The mother’s name was Margaret . . . Giard. They settled here around 1885 and settled on a certain piece of land. Soon after that Mrs. Giard was put on the roll and allotted this piece of land. Then for some reason she was taken off the roll and was told to allow two nephews of hers to hold it and after she could definitely ascertain her rights she would be given the allotments again. But when she was again put back on the rolls her original allotments could not be obtained. She has lived here for twenty-seven years and now that the nephews are growing to manhood, the son Pete Giard wants to put them on this improved piece of property. I consider this an injustice as these boys could have obtained allotments elsewhere. Mrs. Giard is a widow and should this be allowed she will be turned out of a home that has been improved by years of hard labor. They asked me to write to the Society on behalf of their rights as Indians. . . . As a member of the Society I believe in doing good for any worthy Indian family and if the Society can in some way help them it would be for the good of the race.18

In this letter, as a modern Ojibwe warrior woman, Elizabeth acts as this elderly woman’s protector, challenging the behavior of Giard’s nephews. Elizabeth also emphasizes the unpredictable and gendered nature of settler-colonial allotment policy; one moment Giard had land, and the next moment her male relatives had her land instead. Initially, according to the Allotment Act, married women were not entitled to land, but this changed with an 1891 amendment, as discussed earlier. It seems that the Allotment Act affected Native women in arbitrary and unfair ways, since Native males could be given land that once belonged to an older female relative. Much like Henry’s use of the SAI to back the Apaches in their fight for land, Elizabeth used the SAI as a vehicle to support the rights of an Ojibwe elder to receive her land allotment. Therefore, the SAI was a Native, gendered, intellectual, and activist hub that the Clouds relied on to fight in support of Indigenous land and interests.

It was Elizabeth’s and Henry’s mutual involvement in the SAI that brought them together. There are many potential reasons why Elizabeth and Henry became a couple. Both suffered through the federal boarding schools, excelled academically, read voraciously, had a deep commitment to their people, and, most important, were devout Christians. In the following section I discuss Elizabeth’s Ojibwe childhood, her training in white schools, and how she, like Henry, used Native hubs to maintain her tribal identity and her connection to her Ojibwe people.

Elizabeth Georgian Bender’s Childhood and White Schooling

Elizabeth Georgian Bender was born on April 2, 1887, in Fosston, Minnesota, near the White Earth Reservation.19 Her Ojibwe name was Quay-Zaince, meaning a twin, and Elizabeth’s twin sister died at birth. She learned about the Ojibwe world from her mother, Mary Razier, a “full-blood” Ojibwe with an Ojibwe name of Pay Sha Deo Quay. Mary had some white schooling but preferred to speak Ojibwe, and she taught all her children to speak Ojibwe fluently. Mary was a healer, a midwife, and the daughter of a medicine man. Albertus Bender, her husband, a German American, lived and worked in the logging camps. He had blazing blue eyes and married Mary when she was around fifteen or sixteen.20 He learned to speak Ojibwe before he married Mary Razier, so Elizabeth grew up in an Ojibwe-speaking home. They had three daughters, Anna, Elizabeth, and Emma and seven sons, John, Frank, Charles, Albertus, Fred, George, and James.21

My mother, Woesha, loved her grandmother profoundly, until Mary’s death at seventy-three years old. She told me stories of the log-cabin home, where Mary lived alone in her old age. It was ten miles from the Canadian border, in countryside covered with evergreen trees, except where the land was cleared for farming. And my grandfather, Henry Cloud, also loved Mary dearly. She treated him like a son, and he enjoyed helping and supporting her, including building her the cabin she lived in until she passed away.22 Woesha traveled with her family every summer to visit her grandmother Mary. They gathered all kinds of berries around her cabin and saw many animals, including bear and porcupine. Mary kept her log-cabin home immaculate, decorated it with her craftwork, and set up her loom outside in a tent. During Elizabeth’s childhood Mary tended a garden that kept her family happy and satisfied with vegetables, fruit, and flowers; she also canned meat for the long, cold winters. My mother once told me, with a glint in her eye, that Mary could shoot a deer and skin it with one hand tied behind her back. As a child, I would imagine this elderly Ojibwe woman, with a shotgun in her hands, peering down the long barrel and firing. Mary was an independent, strong Ojibwe woman who was able to fend for herself after her husband passed away. Indeed, Mary, early in her marriage, lived near Albertus’s relatives, but she was unhappy there. So she returned to the White Earth Reservation with her children in tow, and Albertus followed her. Mary and Albertus lived on Mary’s 160-acre allotment, where they built a house, a granary, and a farm.23 Mary taught Elizabeth not only to speak the Ojibwe language but also to live as an Ojibwe woman.24

Traditionally, Ojibwe men and women held complementary roles. Women tended the gardens and prepared the meat and fish that men brought home from the hunt. Women undoubtedly directed and managed their own activities. The men who helped did not oversee the women but played assisting roles. Ojibwe women not only prepared the venison and bear’s meat but also had a voice in determining who would receive the divided portions. Fur traders mentioned bartering directly with Ojibwe women for processed furs. Ojibwe women’s power—especially in terms of their control over the ownership and distribution of resources—should not be underestimated.25

Furthermore, in the nineteenth century U.S. government sources described three Ojibwe women as leaders of their bands: “The head chief of the Pillagers, Flatmouth, has for several years resided in Canada, his sister, Ruth Flatmouth, is in her brother’s absence the Queen or leader of the Pillagers: two other women of hereditary right acted as leaders of their respective bands, and at the request of the chiefs were permitted to sign the agreement.” In 1889 government negotiators were encouraged to explain to Congress why Ojibwe women were permitted to sign official arrangements and settlements. Ojibwe women leaders did not seem to present a problem for Ojibwe people, but only for whites.26

My mother, Woesha, did not remember Elizabeth saying anything more about her German American father, Albertus. My aunt Marion, like her sister Woesha, described spending every summer with her Ojibwe grandmother, Mary. But Marion saw her German grandfather only once, when she was six years old. Elizabeth always privileged the Ojibwe aspects of her identity, over the German American one. She maintained a close connection with her Ojibwe mother, Mary, and her siblings, but not with Albertus. Also, Elizabeth had white cousins, her father’s relatives, somewhere in Minnesota, but she never looked them up.27

As a child, Elizabeth helped her parents with chores both inside and outside of the home, challenging white gendered notions of female domesticity and showing she was taught a flexible and fluid Ojibwe notion of gender. Elizabeth wrote, “I used to help my mother in the housework and also used to help my father with the outside work when it was necessary; there was nothing I enjoyed as much as working out in the open air.”28 By discussing her childhood in a fund-raising letter for Hampton Institute (a boarding school she later attended), Elizabeth performs Ojibwe hub making through storytelling, making a connection to her Ojibwe family while away at a boarding school.29 Indeed, Elizabeth’s discussion of gender as a child on her reservation challenges the domesticity training she had at Pipestone and Hampton boarding schools, which emphasized that girls should be confined to the domestic sphere.30 Many years later Woesha encouraged her mother, Elizabeth, to write her life story. One day, as the two of them sat together talking, Elizabeth said proudly to Woesha, “My father said I was as good as any of my brothers. I could clean out the barns (around the cattle stalls) as well as any boy.”31 This is an extremely significant comment about Elizabeth’s fluid sense of Ojibwe gender identity and her interest in working outside the private sphere.

At the age of nine Elizabeth attended her first white school, the Sisters School of Saint Joseph, a Minnesota Catholic school about 150 miles away from the White Earth Reservation. She wrote, “I stayed there for two years and then came home and spent two years at home.”32 After this she spent the next four years at Pipestone, a federal boarding school that was established in 1893. In a 1905 letter Elizabeth wrote,

When I was ten years old I was sent to an Indian government school in Minnesota, called Pipestone Industrial School. The school consists of a large school building, dining hall, boys’ building, girls’ laundry, a large red barn, and a few teachers’ cottages. The girls and boys go to school only half a day the whole year round, the other half being devoted to manual training, such as girls working in the sewing room, laundry, kitchen and baking, and the boys working in the tailor shop, carpenter shop and on the farm. . . . I had two sisters and two brothers there, and we spent four years in going to school there. . . . We had to spend a term of three years there before we were allowed to return home!33

Even though Elizabeth wrote this letter to a “friend” of Hampton Institute (another boarding school she later attended) to fund-raise for the school, there is camouflaged critique of Pipestone. Her use of the word “only” in her description of going to school “only half a day the whole year round” points to an indirect criticism of the lack of academic rigor in her Pipestone boarding-school training. Elizabeth also assertively places an exclamation point in the narrative. In this way she critiques the federal boarding-school policy that separated Native children from their families for long stretches of time. The exclamation point speaks volumes about her negative feelings toward this boarding-school practice. It was necessary to camouflage her criticism during a time when Native people suffered much racism and could not truthfully express their points of view. In a 1900 letter she mentions that she “liked” Pipestone federal boarding school.34 She very well could have felt forced to write she liked the training there. Thankfully, her sisters and brothers accompanied her to these coercive surroundings. Thus, despite the hostility of the colonial environment, her tight family network enabled Elizabeth to create an Ojibwe family—centric hub, which could act as a buffer to some degree.

In her Hampton fund-raising letters, she discusses the lands and people of White Earth. She wrote, “I live on an Indian reservation, and it is situated in a very beautiful spot, among hundreds of small and large lakes. Every fall the Indians find a great pleasure hunting wild ducks on these lakes.”35 Her writing expresses a deep sense of connection to her land and people. She transforms a fund-raising letter, a potentially tedious boarding-school assignment, into a memory of beauty and an ancestral connection to an Ojibwe sense of place. Leslie Marmon Silko writes, “Our stories cannot be separated from the geographical locations, from actual physical locations on the land. . . . And our stories are so much a part of these places that it is almost impossible for future generations to lose them—there is a story connected to every place, every object in the landscape.” According to Silko, Indigenous peoples maintain a connection to the stories of their people, a sense of a Native oral tradition, through maintaining a connection to land.36 By remembering an Ojibwe sense of place, Elizabeth accesses the stories of her people, her Ojibwe identity, hundreds of miles away, from a white-controlled boarding school. Elizabeth challenges the settler-colonial strategy of separation by creating an Ojibwe hub and maintaining a sense of connection.

When Elizabeth describes the experiences of other Native girls and boys at Hampton whose families are far away, she again contests the colonial treatment of family separation: “I came in the fall of 1903 with twenty-three other Indian girls and boys. They all had come from their western homes to go to an institution that they had heard so much of. Some of them were rather homesick and lonesome after arriving here, but I was rather fortunate in having a big sister here. Hampton is just like a home with plenty of room for a big family, and I couldn’t get lonesome if I tried.”37 Here Elizabeth is being subversive by emphasizing how other children felt homesick and lonesome because they were very far away from their families. She indirectly critiques the boarding-school policy of separating Native children from their parents. At the same time, she emphasizes again how the presence of her siblings created a cushion for her in a colonial boarding-school situation. Her description of Hampton as a home away from home once more shows how she and her siblings created an Ojibwe family hub in the midst of colonialism.

Elizabeth’s white father, Albertus, encouraged her to go to Pipestone federal boarding school and later to Hampton Institute, but her Ojibwe mother did not. Elizabeth wrote,

When I went home [from Pipestone], and told my parents of my intentions [to go to Hampton], my father approved, but my mother did not. I told her of the beautiful things I had heard about Hampton, but she said, “It’s far, far away from the land of sky-tinted water.” Of course, she said this to me in the Indian language (Chippewa when translated this is what she said). I finally persuaded her for me to come, and I hated to leave home. My parents felt dreadfully bad the day I left, but my father said, “I want you to study hard, and be a good girl.” I have tried hard to live up to the parting advice he gave me.38

Elizabeth emphasizes her parents’ opposing views of white schooling. Her Ojibwe mother wanted Elizabeth to stay home with her people, while her father wished her to attend white schools. These opposing viewpoints must have been difficult for Elizabeth. Her writing combines her parents’ wishes. On the one hand, she wants to “study hard, and be a good girl” for her father, but she also emphasizes her deep attachment to her Ojibwe home and mother by emphasizing that she “hated to leave.” She also mentions that she understands her mother speaking to her in Ojibwe. Thus, through storytelling, Elizabeth participated in Ojibwe hub making, maintaining a connection to her Ojibwe mother, identity, and language—even while hundreds of miles away from the White Earth Reservation.

While Elizabeth felt a close connection to her parents, her older sister, Anna, did not. Anna’s white schooling started earlier than Elizabeth’s. At age six Anna was sent to the Lincoln Institute in Philadelphia, a federal boarding school. Two of her brothers, Charles and John, went to the nearby “Educational Home on forty-ninth street,” Lincoln, a boarding school for Indigenous boys. After seven years at the school, when it was time to return home to Minnesota, Anna “had no reason for wanting to go home,” she wrote, “except that other students went to theirs. I seldom heard from my parents and was so young when I came away that I did not even remember them.” She continued,

How miserable I felt when the time came to go! It was to me the leaving of a home instead of returning to one. . . . My mother met me at the station bringing with her my two younger sisters and two younger brothers whom I had never seen. They greeted me kindly but they and everything being so new and strange that I burst into tears. To comfort me my mother took me into a store close by and bought me a bag of apples. . . . As we gathered around the table later a great wave of homesickness came over me. I could not eat for the lump in my throat and presently I put my head down and cried good and hard, while the children looked on in surprise. When my father returned from work he greeted me kindly but scanned me from head to foot. He asked me if I remembered him and I had to answer no. He talked to me kindly and tried to help me recall my early childhood, but I had never known many men and was very shy of him. At last he told me I had changed greatly from a loving child to a stranger.39

Anna’s beautiful prose describes the heart-wrenching experience of my grandmother’s sister, my ancestor, no longer remembering her parents and never having met her younger siblings. Her mother, Mary, bought her a bag of apples to distract her from something so horrible, from not recollecting her own mother. Her father, Albertus, spoke harsh words to his own child, telling her she had transformed into an outsider.

Anna’s sad recollection of returning “home” to strangers, her own Ojibwe family, shows the deleterious impact of separating a young child of six years old from her closest relatives for many years. To feel connected to one’s home and family, one must have regular contact. The Native boarding schools’ policy of separating young children from their families was agonizing for the entire Bender family. In this context Mary’s strong reluctance toward Elizabeth leaving to go to Hampton boarding school was reasonable and understandable.

After becoming reacquainted with her sister Elizabeth, Anna felt less lonely than before, but she stated, “I had much to learn and much to endure those next few months that I cannot tell you here.” As her descendant, I wonder what Anna had to endure while she was home at White Earth. She very likely was struggling with feelings of disconnection and confusion regarding her place within her own loving family. Anna spent about three months at White Earth and then prepared to leave for Pipestone, accompanied by her brothers and sisters. “I will remember the day my brothers and sisters and I went away. It was a bitter cold day and we were six miles away from the station. We did not know that a team was coming for us so we started off early in the morning and got three miles before the team came and picked us up, and we went on to Pipestone we [and] two other students.”40 Anna’s description of their departure for boarding school, a scene of children walking together in the bitter cold, expresses a sense of sadness and loneliness.

Anna had already determined before she left Pipestone that she would go to Hampton Institute unless her family needed her back home. A teacher at Pipestone, a former Hampton Institute student, encouraged her to attend Hampton. This teacher “could do almost anything when anybody was sick she could take their places from office work to cooking including sewing[,] matron, nursing and teaching. We used to call her Jack of All Trades and I used to think to myself, ‘If that is the way they educate people at Hampton, there is the place I want to go,’ so the next fall I boarded the train for Hampton.” Anna’s description of her decision to go to yet another white boarding school was consistent with settler-colonial strategies to encourage Natives to move from one colonial environment into another and to focus on vocational rather than college-preparatory training. Anna’s goal at Hampton was to become a typist, and she sought a “general education” in the program.41

Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute was at first a boarding school for African Americans. It started to enroll Native students only in 1878. Samuel Armstrong, son of missionaries, established Hampton. Its Indian department was a forerunner of a federal boarding-school system, a colonial-educational process created to assimilate Natives into American society. The purpose of the private, nondenominational school was to train “the hand, the head and the heart” of youngsters, teaching them to be models and teachers of their people. In many ways Hampton was similar to other settler-colonial, off-reservation federal boarding schools. Hampton snatched students away from their far-off reservation homes; controlled and regulated every single aspect of their education; highlighted white “civilized” religion, culture, and language instead of Native cultural ways and education; launched a summer outing system where students were put in white homes to continue learning English and white culture; and regulated students in military style, with divisions, inspections, and drills.42

Hampton Institute, however, was different from federal-government schools in multiple ways. The school’s roots educating African American students shaped the school’s subsequent program for Natives. The mission was to train Native students to be examples who would train other Indigenous people. Hampton had a more moderate stance in regard to assimilation as compared to other schools, such as Carlisle, whose motto was, “kill the Indian, save the man.” Hampton did not want its Native students to merge with white society but rather to return to the reservations, where they could teach their people. Hampton worked to encourage a “missionary sentiment,” and it was not under control of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Initially, its Native students were supported through private donors, which explains why Elizabeth was encouraged to write fund-raising letters. But once their educational program proved successful, the institute received federal support. Because of the concern that students would “go back to the blanket” or return to tribal ways as soon as they returned home, Hampton’s employees maintained contact with alumni. Follow-up correspondence reinforced the education Natives had received at the school. It convinced critics that Hampton graduates continued to practice the lessons they had learned, and it proved to potential funders the importance of appropriating money for Indian education.

Both Elizabeth and her older sister, Anna, were exemplary students at Hampton, who attended there along with their siblings Emma, Fred, and George.43 Being together with siblings at Hampton must have softened the emotional blow of being away from their parents, enabling them to create an Ojibwe hub in the midst of a white boarding school. Elizabeth and Anna excelled academically and were active in a number of organizations. They were members of the Josephines, a female literary society, and they wrote for the student-run school newspaper, Talks and Thoughts. The school officials even asked them to visit rich whites and fund-raise for the school. At Hampton students were encouraged to celebrate Native American and African American art forms. This relative openness to cultural difference (as compared to Carlisle and other boarding schools) helps explain why much of Hampton’s Talks and Thoughts was devoted to Native American folklore. The school’s founder, Armstrong, encouraged students to write about their cultural traditions in the newspaper. Armstrong’s openness, however, in no way changed his judgment of more fundamental deficiencies of Native people.44 Only hard work and proper Christian training, according to Armstrong, could eventually remedy Natives’ shortcomings. The Bender sisters were encouraged to sing in their Ojibwe language in front of white audiences for fund-raising purposes. Even though Hampton emphasized the civilization of Native students, school authorities referenced the students’ tribal past whenever it proved helpful for obtaining financial support for Hampton. Elizabeth and Anna were subject to whites viewing them as exotic and as living proof that they had been transformed from “savage” to “civilized” Natives.

Elizabeth wrote in Talks and Thoughts about hers and Anna’s fund-raising trip for Hampton, but she leaves out any description of hers and Anna’s parlor performances for white audiences. One could view her decision not to focus on their presentations as a moment of resistance, a desire to not dwell on their experiences being used as Native exotic objects for the benefit of Hampton. While in the earlier fund-raising letter, Elizabeth places an exclamation point as a subversive challenge to policies of separation, this time she writes about the smiles on the faces of boarding-school students. This potentially shows that Elizabeth felt less comfortable being truthful while writing for the student-run paper. In her article Elizabeth concentrates instead on her sightseeing trips to Carpenter and Independence Halls in Philadelphia and to the zoological garden, aquarium, and the Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her discussion of her sightseeing trip emphasizes her status as a Native intellectual and her desire to expand her mind. The Museum of Natural History was the most interesting, according to Elizabeth, because “it contained so many Indian ornaments, weapons, domestic utensils, medicines, and I believe every imaginable thing that the different tribes of America used.”45 In her description of the wide range of Native artifacts, Elizabeth created a Native hub, connecting to her Indigenous identity both in a geographic place, the museum, and virtually, through writing. It was also a way for her to show pride in Native history and Indigenous peoples’ accomplishments.46

The Indian Service

Many of the Ojibwe students at Hampton, like Elizabeth and her sister Anna, worked in the Indian Service.47 Hampton encouraged graduates to serve as examples and teachers for their people, to spread the school’s colonial training.48 In her time with the federal Indian Service, Elizabeth occupied a complicated role as a colonial agent. At the same time, she used her role as a teacher to critique the government, expose the widespread trachoma situation, and improve education for Native students.

Elizabeth taught on the Blackfeet Reservation. She complained that the “Indian Service is not a ‘bed of roses’ by any means and there are some features that are very discouraging. There is a certain class who are incompetent; who possess no love for the work they are in; only as a means of livelihood.” Elizabeth calling her Indian Service colleagues “incompetent” was a strong indictment of the Indian Service overall. When Elizabeth first came to teach on the Blackfeet Reservation, the school provided instruction only until the fourth grade, and later school officials added instruction until the seventh grade. Elizabeth wrote, “We try to follow the state course as near as possible, considering we do not use the state books. But we aim to make our grades correspond to the grades of the state so that our children may enter the same grade should they enter a public school.”49 This attempt to improve education for Native children, trying to provide them with similar education as white children received in the public schools, was another challenge to colonialism. Elizabeth believed that the Society of American Indians could help improve the Indian Service for the better.50

While Henry was busy fund-raising for the American Indian Institute, Elizabeth discussed her experience at the Indian Service during her address, “A Hampton Graduate’s Experience,” at Hampton’s anniversary in 1915, which was later published in the Southern Workman. Elizabeth courageously exposes the rampant trachoma on the Blackfeet Reservation: “This brings me to the horrors of trachoma and my observation among the Plains Indians. It is a disease that without medical attention gradually impairs the sight until blindness results. Upon the examination of one hundred and fifty children in our school, forty-three were found to be afflicted with trachoma. The Government sent out specialists about three years ago, and they found that, out of the Indian population of 300,000, 50,000 had trachoma.” Elizabeth helped treat the trachoma cases before she was transferred to work at the Fort Belknap Reservation, where the trachoma situation was even worse. Someone told Elizabeth that it was the “one-eyed reservation,” and she felt it was almost true. She continued, “I cite these instances because I feel so strongly these problems that are confronting our people; and they are problems that we can all help to remedy, whether our vocation in life is that of a teacher, carpenter, nurse, or blacksmith. If you cannot get a doctor to treat this disease, be interested enough to treat the cases in your own community. Think of it! Nearly thirty percent of all Indian children are in danger of becoming blind. Nearly 17,000 Indians boys and girls are in danger of complete blindness.” At this point in her talk, she was directly addressing the Native students in the audience, encouraging them to become leaders and actively work to deal with the terrible disease. At the beginning of her address, she anticipated health problems on the Blackfeet Reservation: “On the bench was an Indian mother, cuddling in her arms a sickly looking baby and trying to soothe its fretfulness. I learned afterward that they were all of the same family, and were there to take a midnight train in order to see if they could get medical aid which the government doctor could not adequately give the sick infant.”51 Here Elizabeth sharply criticizes the government health services for their inadequate health care on the Blackfeet Reservation.

As a Christian woman, Elizabeth spoke out against the “horrors of the grass dance, the sun dance, and the use of mescal” during her Hampton address.52 Elizabeth, like Henry, criticized Natives’ use of peyote. In fact, all the members of the SAI organized against the Natives’ use of peyote. In contrast, my mother, Woesha, taught me to respect all religious traditions, including Indigenous ceremonies. Woesha drove our family to watch the sun dance on the Pine Ridge Reservation when it was no longer illegal. Reading Elizabeth’s description of Indigenous spiritual traditions as “horrors” is disturbing, although it is an accurate reflection of her time.

Elizabeth resigned after her second year teaching on the Blackfeet Reservation. Instead, she decided to pursue health care, following in her mother’s footsteps. She took a nurses’ training course in Philadelphia at Hahnemann Hospital until she was convinced by her former co-workers and pupils to resume teaching in Browning, Montana.53 Henry, “her sweetheart,” visited her:

Henry Roe Cloud dropped in on us this morning between trains. When the doorbell rang I was surprised to see him standing there, hat in hand, and that pleasant smile. This all happened at the hospital where I am detailed now, and we were having quite a Hampton party in Lavina’s [surname unknown] room. There we sat, Angel, Carmen [surname unknown], and I talking and discussing war, cards, Carlisle and then Mr. Roe Cloud joined us. . . . He wanted to stay longer but had a meeting with Dr. McKenzie and D. Jones at five o’clock in Washington. He certainly is a busy fellow.54

This gathering together of Indigenous people—a Native hub—occurred in the room of her Indigenous friend, Lavina. Here Elizabeth expresses her deep sense of pride in Henry, who had many important meetings to attend, in regard to fund-raising for his Native college-preparatory high school. Elizabeth’s letter also points to a network or hub of Native intellectuals, who gathered together, and met at Native boarding schools, including Hampton and Carlisle.

Elizabeth mentions her friend Angel, who most likely was Angel Decora, the Ho-Chunk artist and intellectual. Decora taught at Carlisle and was an established artist, already published in Harper’s Magazine and with studios in New York and Boston. In Decora’s autobiography, published in the 1911 issue of the Red Man, Carlisle’s newspaper, she discusses that young Indians had a talent for pictorial art, Natives’ artistic knowledge is worth recognition, and Natives at Carlisle are developing these talents and may contribute to American art.55 Decora emphasizes Natives’ inherent artistic talent, the value of Indigenous art, and its prominent location in American art—challenging dominant perceptions of Native cultural achievements as lower on the evolutional scale than those of whites. She also discusses Emma, who was most likely her sister, who attended their Native hub gathering, showing how Elizabeth maintained connections with her Ojibwe family.

In 1913 the Indian Service transferred Elizabeth to Fort Belknap School in Harlem, Montana. She taught Assiniboine and Gros Ventre children in Harlem for a year and then returned to Hampton to resume postgraduate work in home economics. In 1915, two years later, Elizabeth was once again teaching—this time at Carlisle Indian School, the first federal boarding school, founded by Richard H. Pratt in Pennsylvania, as already mentioned. In 1916, while at Carlisle, Elizabeth wrote about white notions of womanhood in the Carlisle paper, Red Man. Her article, “Training Indian Girls for Efficient Home Makers,” begins in a covertly subversive manner: “DO NOT intend to tire the reader with long drawn out stories of broken treaties, the misappropriation of Indian money, nor do I intend to dwell on the subject of how we have been starved . . . on various reservation[s]. . . . We hear a great deal about developing leaders for leadership and are apt to forget that our girls are to be the sources of such leadership, too, for they represent our homemakers and homekeepers.” Even though Elizabeth emphasizes that she will not discuss the terrible impact of colonialism on Natives (by using capital letters), she still rebelliously reminds the reader of past abuses. Elizabeth argues that Native women are important sources of leadership, while emphasizing Indigenous women’s role within the domestic sphere, as taught in federal boarding schools.

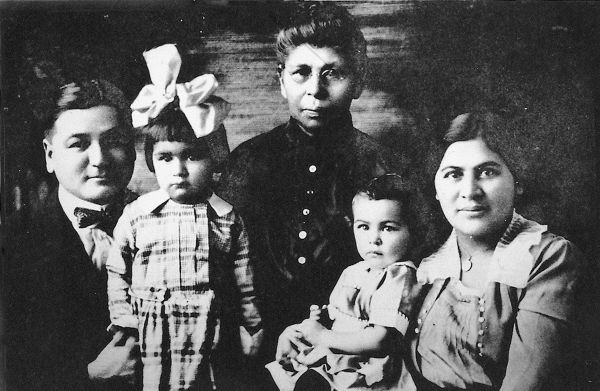

Fig. 4. Henry and Elizabeth at the center of the photo. Elizabeth’s sister Emma is to the left, and Carmen, a friend, is to the right. Photograph courtesy of the Cloud family.

However, insofar as subservience—as opposed to leadership—was foundational to white notions of domesticity, Elizabeth creatively combines Ojibwe and white notions of gender. At the same time, her article reproduces gendered, colonial ideas about domesticity. Since “the home is the very core of civilization,” Elizabeth argues that Native Americans’ successful integration into U.S. society was in the hands of Indigenous women. She portrays the reservation as places where “unkempt homes which are breeding places for filth and disease outnumber the homes of cleanliness and Christian training, and thousands and thousands of acres of Indian land rich in undeveloped resources, are lying idle.”56

Elizabeth follows settler-colonial and racist ideas that Natives’ homes were dirty and in need of Christian influence, and she follows colonial notions that Indigenous lands lay idle and needed to be developed. She, regrettably, also wrote, “Can we expect to develop great, strong Christian leaders in spite of such home conditions? Yes, we can. We can take our youth away from home, send them off to such schools as Haskell, Carlisle, or Hampton for a period of years, and have them associate with high minded instructors who shall teach them that the home is the very core of civilization, that the ideal home shall permeate its environment and bring it into keeping with that of their school.” Here Elizabeth follows gendered, settler-colonial strategies for civilizing Native women through the imposition of white, female gender norms. In this article she agrees with the policy of separating Native children from their families, which is very different from her subversive use of the exclamation point in one of her early Hampton fund-raising letters, in which she underscores how difficult it was to be away from her family for so long. This diametrically opposed change in perspective could reflect how her audience of white Carlisle officials influenced her writing, encouraging her to communicate in a very gendered, settler-colonial manner. She wrote this article while she was a teacher at Carlisle, possibly feeling compelled to write something her superiors would have agreed with, to keep her job.

Furthermore, according to Lucy Maddox, Native intellectuals during this time often combined white and Native rhetoric to be heard in the public sphere. Like Henry, Elizabeth mixed Indigenous and settler-colonial perspectives in her writing and speaking, which enabled her to be heard in the public domain during a very racist and colonial time.57 At the same time, Elizabeth praised Carlisle for creating a “model home cottage” that instructed Native women “how to cook over a common stove, take care of kerosene lamps, and prepare three meals a day in the most wholesome and economical way . . . to learn the art of cooking cereals, vegetables, eggs, fish, bread, cake, and pastry, besides the proper setting of a table and the preparation and serving of family meals.”58 Here Elizabeth again supports white notions of women’s domestic roles, criticizes reservation life, promotes assimilation, and, even more painfully, encourages the allotment of Native lands.

Unfortunately, in this article Elizabeth’s Ojibwe warrior woman identity was mute, covered and camouflaged by white-centric rhetoric. Instead, she spoke primarily from a “good Indian woman” voice, a voice that points to the reality of working and living at a bastion of settler colonialism, Carlisle Indian School. As Elizabeth’s granddaughter, reading this article, imbued with settler-colonial notions of gender and supporting assimilation and allotment, was indeed difficult, agonizing, and challenging. It was also surprising since later Henry, as a modern Ho-Chunk intellectual and warrior, fought back against allotment in his role as coauthor of the Meriam Report and the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934.

Reading this essay, I remembered that central to my work of decolonization is confronting the hard truths of colonization and discussing how my grandparents, at times, were complicit in settler colonialism. My work to face these excruciating colonial moments is integral to my Native feminist ethic. At the same time, I remembered their Native intellectual contemporary Luther Standing Bear and his simultaneous support and rejection of the assimilation campaign against Natives.59 In his book My People the Sioux, for example, he discusses traveling to recruit fellow Lakotas to attend the federal boarding school, Carlisle, and paints a positive picture of Carlisle. In contrast, in his next book, The Tragedy of the Sioux, he discusses how he was a bad Indian, a hostile; he does not discuss any desire to stay at Carlisle or portray this federal boarding school in such a positive light. This ambivalence between Native and settler-colonial perspectives in both Elizabeth’s and Standing Bear’s portrait of Carlisle gestures at how Native intellectuals, during this racist and colonial period, were strongly encouraged to mimic white culture and discourses. Consequently, they were not comfortable expressing total honesty about their experiences or perspectives. Instead, they used doubleness, camouflage, and masking to protect themselves. It seems that Standing Bear became more comfortable being honest in his later publications as compared to his first book.

Henry and Elizabeth Get Married

My grandparents, Henry Roe Cloud and Elizabeth Georgian Bender, announced their engagement in 1915 and married on June 14, 1916. They got married at the home of Charles and Marie Bender, Elizabeth’s brother and his wife, in Philadelphia. Charles Albert Bender, who was a great pitcher for the Philadelphia Athletics, was eventually inducted in the 1953 Baseball Hall of Fame. Later on Henry described his relationship with his wife, Elizabeth, to a good friend of his, Harold Buchannan. He told him that he was happily married to Elizabeth, he was deeply proud of her, and he was proud to be her life partner. He told Harold that Elizabeth had often been his guidepost.60

In 1916 Henry described the racism he and his new wife, Elizabeth, experienced. He discussed their visits with affluent whites for the purpose of fund-raising for his college-preparatory high school for Indian boys. A letter to Mary Roe demonstrates the positive influence of Cloud’s published autobiography, which underscores his identity as a self-made man:

That noon in going to the hotel for lunch we were taken for Negroes and sent to the kitchen for our lunch. When I asked for the ladies wash room and toilet room the proprietors pointed to a slop bucket and told me to wash there. When I asked her if that was all they had, she said “yes.” Needless to say we did not eat in the kitchen nor wash in the slop place. We ate in the dining room with all the members of the Harvard club. Elizabeth and I felt pretty blue for two days. The first time she went with me to make an appeal [for money] I got such brusque treatment and such insult from piggish folk.

The world has its two sides but Christian philosophy melts it all. We took it as part of the game. We visited the McCormicks and I shouldn’t be surprised if they give us as much as $3,500. One of the finest experiences in my life came after this affair at Lake Geneva. Mr. McCormick invited Elizabeth and me to dinner. To my great surprise he said, “We will drive over to my mother’s place and see her [for] five minutes!” As soon as she came out she said, “Why, Henry Cloud I know all about you. I have read [about] your beautiful life in the Southern Workman. I am so happy to meet you and Mrs. Cloud.”61

Henry highlights his feeling of power as an educated Native man by sharing how he rejected eating in the hotel’s restaurant because of racist treatment, deciding instead to dine at the Harvard club. He emphasizes his and my grandmother’s resilience and strength, quickly recuperating from feeling “blue” and viewing their racist experience as “part of the game,” while stressing their exceptional fund-raising skills. Cloud highlights two sides of white society—one racializes him, and the other gives him respect. Rather than seeing my grandfather through a racist lens, Mrs. McCormick discusses his published autobiography and portrays my grandfather’s life as “beautiful.” Henry attributes his respectful treatment to Christianity, since the McCormicks were Christians. Indeed, his rhetorical use of the self-made man and his Christian identity most likely supported the elderly Christian woman’s positive impression of him.

American Indian Institute

Henry Cloud’s desire to improve Native education motivated him to found the American Indian Institute, originally named the Roe Indian Institute (after his white adopted father, Walter Roe), an early Native college-preparatory high school for Indigenous boys. According to my mother, Woesha, her parents wished the school could have also included Native girls, but funders were not interested. My grandparents were living in an intensely sexist time, when men and young boys were privileged over women and young girls. Dominant society was following patriarchal notions of gender. Therefore, males were encouraged to attend college more often than females.62 As late as 1918 the Commission on the Reorganization of Secondary Education argued for a two-track system. White girls and girls of color were encouraged to train for vocations, while students, mostly boys, were guided to take college-preparatory courses. It was not until 1932 that this sexist policy was supposed to change at the school. It was announced in the Wichita Beacon newspaper that a cottage was to be built, because Native girls would be admitted soon to the American Indian Institute.63 When I found this newspaper article in our Cloud family archival material, I was surprised to discover the school planned to admit girls, since my mother, Woesha, did not tell me this. I wondered if this really came to pass and hoped that it did.

From 1910 to 1931 Henry Cloud fund-raised for the school, developed its curriculum, and co-ran the school with his wife, Elizabeth, starting in 1915, when the school opened its doors. Henry must have received valuable educational advice and counsel from his wife, as she was trained as a teacher, an experience and profession Henry did not share. His later involvement in the Meriam Survey taught him that his own abusive educational experiences in a government boarding school were not isolated, but common throughout Indian Country. Federal-government schools for Native Americans offered vocational training that was of little use to their students, both on and off the reservation. Even the education provided at the famous Carlisle and the Hampton Institute was heavily vocational. Cloud chose Wichita, Kansas, as the school’s site, because of its central location, to encourage Native students from all over the country to attend.

During the first few years, Native students were able to utilize classrooms in Fairmount College’s basement and lived in a small cottage. Once new buildings could be financed and built, the main campus was situated at Wellesley Avenue and Twenty-First Street in Wichita. The school included one large dormitory; a smaller two-story dormitory with five bedrooms on the upper floor, a kitchen, dining room, bathroom, and a library; a one-story cottage; a driveway with two stone gates; and a flagpole. The cottage was big enough for a teacher’s apartment and to house five students. A barn, agricultural structures, and wheat fields were part of the campus too.64

My aunt Marion Hughes described her early years at the school. “When I was small and growing up, we lived on campus, which later became the home of other people who worked at the school.” Later, she described, her dad bought property to the east of the school, a home and forty acres. The school was on a hill, then there was a valley, then the Cloud home, with a barn and outbuildings at the house. She continued, “We used to play in that barn, and in the hay. The field to the east was always put in wheat. . . . My sisters and I sure used to play on the haystack. It was out from the city [of Wichita], five minutes into town, but we didn’t grow up in the city. It was on the east side of Wichita. It was pretty flat towards Colorado [Street], but there were hills to the east, the Flint Hills, which went more than 200 miles northeast.”65 My aunt Marion also discussed how she and her sisters always considered these Native students their big brothers. Marion’s description shows how the school provided a warm, fun Native home and hub for my aunt and her siblings. Furthermore, Marion and her siblings always appreciated the visits of their cherished Ojibwe grandmother, Mary Razier, Elizabeth’s mother.

The school opened in September 1915, with seven students enrolled, including George Martin of Alaska (tribal affiliation unknown), William Ohlerking (Cheyenne and Sioux), Harry Coonts (Pawnee of Oklahoma), Walter Laslay (tribal affiliation unknown, of Iowa), Robert Chaat (Comanche of Oklahoma), David C. Hamilton (Cheyenne of Oklahoma), and Burney O. Wilson (Mechoopda of California). During the second year, enrollment increased to fourteen.

Because the American Indian Institute served a relatively few number of Indigenous students, class sizes were small, and students could receive an excellent college-preparatory education, including, for example, science, history, language arts, and foreign-language courses. Henry Cloud hired Native teachers—an early form of Native hiring preference—who could act as Indigenous role models while providing first-rate instruction. James Ottipoby, a Comanche and a graduate from Hope College in Michigan, taught history. Roy Ussery, a Cherokee, was the science teacher, and Robert C. “Charlie” Starr, a Cheyenne-Arapaho and a graduate of Oklahoma State University, was an instructor of agriculture. Because it was a Christian nondenominational high school, students also received biblical history instruction. As the school increased in size, a three-story dormitory was planned. There was not enough money for this building until May 1921. It was named after a benefactor from Chicago, Elizabeth Voorhees and was therefore called Voorhees Hall. It was large enough to house thirty to forty students. There were two apartments on the bottom floor, and the rest of the building included two big meeting rooms that were used for study hall in the evening.66

Fig. 5. American Indian Institute, originally called Roe Indian Institute—the small sign in the photo uses the original name. Photograph courtesy of the Cloud family.

Henry Cloud provided Native leadership education for Indigenous boys. He hoped that his school could educate a new generation of Native American leaders by giving Native American boys a Christian-based, nondenominational high school education. Harry Coonts, a Pawnee who attended the school, explained his understanding of the leadership training he received there: the American Indian Institute “taught Christian leadership, that is to say an Indian man was to fight for his people to get justice.”67 Cloud encouraged his students to transform a Christian, individualized, masculine identity into one that incorporated an educated warrior identity, encouraging them to fight for the well-being of tribes, to be of service to Native Americans, and to right the wrongs of the federal government.

Fig. 6. Henry holding his eldest daughter, Marion, on his lap. In the center of the photo is Elizabeth’s mother, Mary Razier. Elizabeth holds her daughter Anne Woesha on her lap. Photograph courtesy of the Cloud family.

Harry Coonts, who became the president of his tribal council, is an example of the American Indian Institute’s successful Native leadership training. The following is his testimony to Cloud, regarding his tribal situation:

We, the Pawnees—the members of the Pawnee Council, are the eyes of this Tribe. . . . You [Cloud] used to say that the removal of the Pawnees constitutes one of the saddest marches ever in this land. We then numbered 10,000, now we are only 800. In the treaty of 1857 we ceded to the United States 25 to 26 counties a record of which will be found in the Omaha Cession 1856 and 1857 section: all lands lying north of Platte River to the point west where the two forks of the Platte River separates. . . . Within this tract of land was reserved for Pawnees thirty miles east and west and 15 miles north and south. The United States Government promised, by treaty, to pay Pawnees $30,000 annually. That is what we are receiving today. The government also promised to educate Pawnees in the same treaty. A school was to be turned over to them after the fulfillment of the treaty. I want you to understand today that the government owes an education to the Pawnees. The Pawnees have been loyal to the Department. The Pawnees have ceded a great territory to the United States. . . . In 1917–1918 a Competency Commission came from the District of Columbia. This Competency Commission issued patents to individual Indians because they could speak a little English. . . . Not one of those so called competent Indians has a foot of land left today. This business of declaring Indians competent to take care of themselves has made a very hard road for the Pawnees. . . . When you get to Washington D.C. tell the Secretary of the Interior that you were with the Pawnee council, that one of them was your first students to come to your school, that he was telling you the real facts about the trust period needs to be extended to these people, that the government must not turn them loose upon their resources, that it would be nothing less than a crime. . . . So, on behalf of the Pawnee Council say that the tribal sentiment is strong for the extension of the trust period.68

Demonstrating his Cloud-inspired educated warrior skills, Coonts exposes the abuses of the federal government, including forcing the Pawnees on a horrific march, and implies that this removal caused the loss of many of his ancestors’ lives. He argues that the government owed the Pawnees an education in exchange for the Pawnees ceding massive amounts of land. Coonts uncovers the often terrible cost of being declared competent, precipitating the loss of even more Pawnee land, and the importance of the government extending the trust period (rather than losing trust status and no longer having Indian-specified legal status and rights). Indeed, Coonts discusses how Cloud taught him Native-centric history, helping him understand the government’s injustices.

The federal government established Competency Commissions to determine whether individual Natives were competent enough to use their lands allotted to them during the General Allotment Act of 1887. Individuals, who were determined to be competent, were issued fee patents regarding their land. While a fee patent gave power to the allottee to decide whether to keep or sell the land, the enormous loss of Native lands was almost inevitable and unavoidable, given the harsh economic reality of the time and lack of access to credit and markets. Department of the Interior officials knew that virtually 95 percent of fee-patented land would eventually be sold to whites, supporting more Indigenous land dispossession.69

Later, in the 1949 commencement speech for graduating Mount Edgecumbe Alaska Native students, Henry Cloud discussed other pivotal educated Ho-Chunk warrior values, which he must have taught his American Indian Institute students, including pride and courage. By encouraging his students to become educated warriors for their people, Cloud defied the federal boarding-school training that taught Natives to be ashamed of their tribal identities, cultures, histories, and philosophies and focus on subservience rather than Native leadership. Motivating Native students to feel a sense of pride and courage was an antidote to the colonial boarding-school regimen of shame and subservience. Therefore, Cloud worked from a traditional Ho-Chunk educational perspective to encourage Native students to regain a sense of prideful, Indigenous humanity; to become motivated by ancestral warrior courage; and to stand up and fight for Native people and challenge colonialism. Similarly, Paulo Freire emphasizes the importance of regaining one’s humanity while experiencing oppression as an empowering aspect of working for social change.70 Notably, reclaiming a sense of Indigenous pride is paramount to becoming tribal sovereign peoples. According to Cloud,

And the [Indian] race needs pride in your origin. Never be ashamed that you are an American Indian or Native of Alaska. Never be ashamed. I am thinking of the Iroquois [Haudenosaunee] tribe in the States. They had self-government. . . . They had a constitution followed upon that of the clan organization. . . . . Benjamin Franklin took lessons from their tribal organization and put [these lessons] in the US constitution of the United States of America. Your [Indian] race has accomplished things of that sort of world import. You should lift your head and be proud that you are a Native American. And then you should have courage. The Indian race despises a coward. . . . There is philosophy among my [Ho-Chunk] people when the smoke of battle clears away let the enemy see the scars on your face [not] on your back. Face forward in the fight [against] all odds and costs. That is applicable to your vocation and anything you propose to do in this life.71

In this quote Cloud opposes the colonial notion that Natives were an inferior race by emphasizing that these young students should not be ashamed of their Alaska Native identities, but instead very proud. He disputes the settler-colonial historical narrative about a heroic struggle between good and evil, viewing Indigenous peoples as evil and settlers as good. Cloud critiques this good-versus-evil binary by arguing that one of the founding fathers of the United States, Benjamin Franklin, learned from the Haudenosaunee constitution and introduced Native concepts into his formulation of the U.S. Constitution. In Cloud’s historical rendering, Natives were not evil, but instead they had ideas of “world import” that were so powerful they influenced the writing of the U.S. Constitution.

In this way Cloud portrays Natives as intellectuals in their own right, who had systems of government that were equal (if not better) than the colonial government. Cloud also emphasizes that the Haudenosaunee had “self-government.” The idea of “self-government” has a settler-colonial connotation in which tribal governments become subsets to the U.S. colonial nation as part of the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. Regardless of the colonial meaning of the word, Cloud’s discussion assumes that Natives had their own powerful governments and were sovereign nations before the advent of the colonizers. Cloud’s analysis is a pathbreaking Ho-Chunk intellectual insight about tribal sovereignty and nationhood that predates later Native studies scholarly discussions, including Vine Deloria Jr.’s and Clifford Lytle’s important 1984 book, The Nations Within.72 This was a strong prosovereignty stance, strikingly different from his earlier speech to the white reform group, Friends of the Indian (see chapter 1). His divergent and opposing viewpoints allude to two diverse audiences, the ultraconservative white reform group and the young Alaska Natives. These viewpoints must have been influenced by Cloud’s age while delivering these two speeches—at the time of the first speech, he was in his twenties, and the second, his sixties—and the influence of the racist years of the early twentieth century. Furthermore, Cloud emphasizes a Ho-Chunk warrior philosophy that revolves around summoning courage, confronting fear, standing up, and facing all challenges. He encourages Native students to rely on these Ho-Chunk educational values and philosophy to attain a modern vocation. Cloud, therefore, inspires Native students to combine traditional and modern identities. Cloud was a modern educated Ho-Chunk warrior and an intellectual, and he encouraged these Alaska Native students and, I am certain, American Indian Institute students to follow in his footsteps.

Cloud described founding the American Indian Institute to graduating Alaska Native students at Mount Edgecumbe High School in Alaska in 1949:

I founded the American Indian Institute for young [Indian] men in the states. And there I taught them the work system. They had to work, rich or poor—that was the life of the institution. An Osage boy came [to the school] from the Oklahoma country and he had money from oil, royalties. We had him work along with the other boys. We harvested great fields of wheat. He stood at one end of the field of wheat and looked way down yonder and had to shuck this wheat. After perspiring heavily at the end of one row, he turned to me and said, “I now know what goes into a loaf of bread.” He had been receiving $3000 every three months. He did not have to work, but after graduation he took a job just like any boy would and rose in that job until he became an official in the Greyhound lines.73