4

The Work of Henry and Elizabeth Cloud at Umatilla

As a boy, general council chair of the Umatilla Reservation, Antone Minthorn, recalled seeing Henry around his Indian agent house—a two-story, white wooden-framed house on the west end of the tree-shaded Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) grounds. He would watch Henry practice his golf drive, and sometimes Antone would go looking for the lost balls. Viola Wocatse, receptionist at the Yellowhawk Clinic, also remembered Henry. She said he did a lot for the young people, encouraging them to work in the summers. She described him as both strict and nice, inspiring those around him to learn about their world. Sonny Picard, a refuse-truck driver, said that if you got in trouble, Henry would be right there and get you out of jail. Margarite Red Elk recollected Cloud as a very helpful superintendent: he got around among the people—and this marked a change from the former superintendent’s distancing himself from Umatilla Natives. Elizie Farrow remembered one day when a government car pulled up with a big Indian as its passenger. Henry introduced himself and said he hoped to be the next superintendent.1

In August 1939, after Cloud’s involvement in the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) and his short-lived tenure as superintendent of Haskell, he suffered a significant demotion. His pay plummeted, and he lost his platform on the national stage. The downgraded position was agency superintendent, or Indian agent, of the Umatilla Reservation in Pendleton, Oregon. The Umatilla Reservation includes Umatilla, Cayuse, and Walla Walla tribes. The federal government, according to Cloud’s daughter Marion Hughes, offered him the job with the hope he would quit and as a punishment for his critique of the Indian Service.2 Cloud’s decade or so as an Indian agent of Umatilla was challenging. Federal-government officials thrust him into the midst of factional reservation politics: issues around hunting, fishing, timber, and agriculture, as well as land-lease problems. Although his Yale education had served him well—providing him with powerful networks and funding sources—it also linked him to white, settler-colonial forces. In other words, Cloud’s identity as a well-educated modern Native put him in the middle of reservation politics. Cloud’s identity and Indian agent role could also place him on the side of his white predecessor, Omar L. Babcock. Cloud’s tenure as Indian agent, however, diverged from Babcock’s. Cloud challenged white racist attitudes, supported Umatilla Natives in their struggles over fishing and hunting rights, combined white and Indigenous rhetoric in his writing and speeches, worked to be transparent regarding his goals and objectives, and ultimately supported tribal sovereignty. Meanwhile, Elizabeth founded the Oregon Trail Women’s Club for Umatilla women, an Indigenous and gendered hub that boosted Native women’s pride in their tribal identity, developed a modern Native identity, and encouraged college education.

The Umatilla Reservation is in the Umatilla River Valley. On the western edge is the city of Pendleton and toward the east are the Blue Ridge Mountains of Oregon. White settlers traveled west along the Oregon Trail, plowing the ground, erecting homes, and building up their colonial infrastructure—all to settle and stay in land belonging to Indigenous people. Around 80,000 acres of land of the reservation was farmland of wheat or peas. About half of the reservation had transferred into white ownership, because of the Allotment Act of 1887 and the forced removal of Natives onto the Umatilla Reservation after the signing of the treaties of 1855. The BIA held the remaining 30,000 to 40,000 acres of Indigenous land in trust for Native owners. Land ownership looked like a checkerboard, with white and Native parcels of 160, 80, and 40 acres intermingled. Natives owned portions of land, sometimes sharing each parcel among six or more adults and children. Most of the Indigenous-owned farmland was leased to white farmers, who owned sprawling and expansive ranches surrounding the reservation.3 Native Americans had difficulty farming their own land, often lacking the funds to purchase the necessary equipment. And since they needed money to survive, Indigenous peoples were compelled to lease land, once again suffering land dispossession and settler colonialism—leasing land to white settlers ultimately eliminated Natives from access and use of their own land.4 Even further, Umatilla Natives received exploitatively low land-lease payments, while white farmers reaped the land’s profits. With such limited access to money and land, Umatilla Natives barely survived, forced to rely mostly on hunting and fishing, low land-lease payments, and government assistance.5

As a result of the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, many tribal governments were forced to follow non-Native models of political decision making and economic distribution. Tribal-government leaders often occupied—and still occupy—challenging positions as go-betweens. Leaders, once elected, must work with the settler-colonial institutions of the BIA and Congress. Cloud, as a “good” Indian and an Indian agent, represented an instrument of the state, the BIA. He was implicated in the very governmental apparatus created to keep Indigenous people dependent on colonial institutions—a role that ultimately pitted him against “bad” Indians. In other words, “traditional” Natives often saw Cloud as their enemy.

Cloud’s oldest daughter, my aunt Marion Hughes, explained why her father was transferred to Umatilla after working on the national stage:

When he [Cloud] was in the Indian Service . . . he never kept quiet with criticism. . . . That was one reason they offered him the Pendleton job at [the] Umatilla reservation. . . . They thought he would quit and they were trying to get him out of their hair and he said, “I’ll take that job. I love that country,” which shocked the wits out of them. Their ploy didn’t work. So, he was there ten years and he did a whale of a difference in Pendleton. . . . [Whites] had previously used the Umatilla and Nez Perce Indians for the Roundup parade.6

After taking this job, Cloud suffered a major cut in pay. At his previous position he earned $4,600, and, as an Indian agent, he received $3,200.7 According to Cathleen Cahill’s book Federal Fathers and Mothers, the Indian Service often employed Indigenous peoples, and their superiors encouraged them to model the ideals of assimilation (e.g., submission to whites) to “bad” Indians. But when Natives became critical of the Indian Service or their loyalty to superiors was in question, they would be transferred to another location in the Indian Service to work.8 My aunt Marion’s description of Cloud’s reassignment to Umatilla shows how he was punished for being a bad Indian, who was critical of the BIA. Cloud’s transfer emphasizes his Ho-Chunk warrior identity—he fought his superiors, who wanted him to leave the Indian Service. Instead, he told the Indian Service, “I love that country.” This declaration alludes to his Native connection to land and his making another Indigenous hub—a sense of connection not based in geographic space. Relying on his identity as a Ho-Chunk warrior, Cloud taught his daughter to fight rather than surrender.

Cloud’s sharp intelligence, expertise, and connections had been relied on regarding the investigation of Native conditions throughout Indian Country, the writing of the Meriam Report, and later the development and passage of the IRA. And now, as punishment for his critique of the Indian Service, he was sent to the Umatilla Reservation as an Indian agent. His new, paternalist position meant fellow Natives could easily hate him. At the same time, to keep his job, he had to listen to and implement his superiors’ goals. Although criticizing the Indian Service was in his comfort zone, other Indigenous peoples despising him was not. Federal officials, rather than rewarding him for improving the BIA and helping change government policy from assimilation to cultural pluralism as part of the IRA, demoted him. He was no longer in the national spotlight and was forced into the challenging settler-colonial position of Indian agent.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs buildings were positioned under gigantic old trees. My mother, Woesha, and my father, Robert, lived there with Henry and Elizabeth in the Indian agent’s house after my father returned home from military service when World War II ended. In a 1988 interview my dad discussed how challenging Cloud’s role on the Umatilla Reservation was. “But he [Cloud] also had trouble—during the three months that essentially I was on the [Umatilla] reservation in Pendleton where he was addressed as ‘The Major’ because in the old days when the Army ran the reservations it was always a major who was the superintendent . . . some of them just hated his guts.” My parents witnessed how incredibly difficult Cloud’s role was as representative and arm of the federal government and how tribal members—especially the older ones—loathed him.9 Natives at Umatilla saw Cloud as either an assimilated Native or “white.” As an Indian agent, he wore a suit, drove a government car, and played golf—markers or masks of a modern, assimilated, and even white status. Cloud dressed impeccably, wearing a three-piece suit every day, which very well could have alienated him from the impoverished Natives of Umatilla. In addition, his middle-class, Yale-educated status could represent many negative white attributes to other Natives. His clothing style and education most likely supported tension between him and other Indigenous people. Among whites, in contrast, his modern Native attributes could help him perform a “good” Native role and mask his underlying warrior identity.

Undeniably, these class markers are still relevant in Native communities today, both on the Winnebago Reservation in Nebraska and for tribal members of the Ho-Chunk Nation in Wisconsin. In an August 2011 interview, John Blackhawk, tribal chair of the Winnebago tribe of Nebraska, discussed his choice to wear jeans and a T-shirt as he went about his work as tribal leader. He wanted members of his tribal council to focus on the work at hand rather than get distracted by issues of hierarchy.10 In contrast, during an August 2011 interview, Jon Greendeer, tribal president of the Ho-Chunk Nation, discussed his decision to dress professionally, claiming his professional attire did not negate his respect for Ho-Chunk culture. He argued that one can wear professional dress and maintain traditional elements of Ho-Chunk culture.11 While today one can be viewed as Native while dressing professionally in tribal communities, during Cloud’s tenure as superintendent, a suit and tie could easily represent whiteness.

Henry Challenged Racism and Settler Colonialism

When Cloud took his job as superintendent of the Umatilla Reservation in August 1939, some businesses displayed signs in their windows stating, “No Indians allowed.”12 These signs were in restaurants, bars, and card rooms. Leah Conner, the daughter of the Clouds’ close friend and employee Gilbert Conner, babysat Cloud’s granddaughter, my cousin Gretchen. In 1988 Conner discussed how in the town of The Dalles, when Indigenous peoples went to the movies, they had to sit in the balconies. They were forced to sit there, because they lived at Celilo Falls, a salmon fishing site, and whites complained they smelled of fish.13

Fig. 14. Cloud wearing a three-piece suit as Indian agent of Umatilla Reservation. Photograph courtesy of the Cloud family.

Cloud challenged this sort of racism. He gave several sermons to this effect at a Presbyterian church in Pendleton. Within a year after Cloud’s arrival, according to his daughter Marion, there were fewer signs of Native prejudice.14 For example, sometime during World War II, Henry brought the Umatilla Indian Young Peoples’ Choir to church, and in his sermon he said,

They are organized to rally the Indian youth to the Standard of Christ, to carry forward the torch which the Nazarene, a mere youth himself, passed on to adventurous youth for each succeeding generation. They speak the tongue of their people. They know how to reach the hearts of their people. These Indian youths, out in quest of the larger, richer life, know the thought-life of their people. They know the actual living conditions of the whole Umatilla Reservation. They know that there is vast need for improvement in the life of their people. But they also know, and this is important, the many good things prevailing among their people come down to them from ancient times. They know that without the teachings of the white man a great many of their families from generation to generation have lived the hygienic principles of cleanliness as nature taught them, have been faithful to old custom marriages surpassing by far the average moral code practice of the general white population. These achievements form the true index to their pride—a racial characteristic.

Cloud finished his sermon by saying, “These young people, because of their Christian faith, will be the true interpreters of their people by word and example. They have faith in the future of America. They are supporting our national defense 100 percent.”15 As a Ho-Chunk intellectual, Cloud contests the racist, settler-colonial notion that Indigenous peoples are inherently dirty by emphasizing that Umatilla elders had taught these young, Christian Native young men to be clean and that this cleanliness was an inherently racial characteristic. Portraying Natives as dirty, primitive, and uncivilized was a way for white settlers to justify stealing Indigenous land and work to eliminate our tribal identities in federal boarding schools—both acts of settler colonialism.16 He also disputes the gendered settler-colonial Christian notion that Indigenous peoples’ “old custom” marriages were immoral. Gendered settler colonialism involved U.S. policies regarding the federal boarding-school system, which worked to destroy Native kinship systems, trying to supplant them with the heteronormative, patriarchal Eurocentric model of the nuclear family.17 By emphasizing that Native custom marriages far surpassed the average morals of whites, Cloud challenges the white Christian practice of looking down on Native marriage practices.

In addition, Cloud discusses that the young people knew the “tongue” of their people, meaning they knew their Native languages, which challenged the federal government’s attempt to eradicate Indigenous languages. Cloud, as a Native Christian man, highlights that these Christian, young men are the ones who will lead their people into the future and challenges the racism and marriage practices of white settlers. Thus, he brings an Indigenous Christian perspective to bear on colonialism. He emphasizes that these Indigenous peoples supported national defense, showing Natives were “good U.S. citizens,” not just “bad Indians,” who were not Christian and “primitive.” One could argue that his Christian faith was an example of an oppressive religion. Certainly Christianity has been involved in many settler-colonial processes, including creating federal boarding schools and forcibly inserting the white nuclear family into Indigenous family relations. Cloud’s discussion shows a complicated response: he challenges settler-colonial practices while emphasizing the importance of Christianity. Thus, Cloud was a “good” and “bad” Native simultaneously. Cloud highlights that Native Americans can have a complicated identity too—Christian and a veteran and still be Indigenous.

In 1940 Cloud defied Pendleton’s white community by writing to John Collier, the commissioner of Indian Affairs, complaining that the Indigenous community at Umatilla was being used as a tourist attraction as part of the Pendleton Round-Up. In his letter to Collier, Cloud challenged racism on a national level:

By financial inducement and privileges bestowed in one form or another approximately 1,000 of our Indian people in full Indian regalia, comprising men, women and children, are led to participate in the “Pendleton Round-Up.” It is universally admitted that this Indian participation and the Indian section is the heart and central attraction for the white population. Some go so far as to say that were the Indians left out of it, that immediately the “Pendleton Round-Up” would become a gigantic flop. . . . The outstanding impression one receives is the commercialization of the Wild West in which the Indian plays the chief role. . . . The “Happy Canyon” performance in the evenings is a little piece of Indian pageantry combined with a portrayal of pioneer-village days and life with some true historical flavor along with characteristic gambling features that used to obtain in all the towns of the Pioneer West. “Happy Canyon” and the “Pendleton Round-Up,” however, at their best, cannot be said to be of real educational value for the Indians or the citizens in general.18

The Natives of Umatilla suffered from severe poverty and dressing up in their traditional Native dress for white audiences’ money and enjoyment was certainly an important way for them to support themselves economically and put food on the table. In this quote Cloud emphasizes how whites profited from Indigenous peoples’ performances of their Native identities, implying whites’ marketing of Native American identities was central to the financial success of the Pendleton Round-Up. In this way Cloud points to whites taking advantage of Indigenous peoples’ poverty. These two events were not Indigenous-controlled and Indigenous people did not receive the lion’s share of the profits from their own performances. Cloud’s description of the Pendleton Round-Up as a “commercialization of the Wild West” recalls Buffalo Bill Cody making cowboys into heroes during Wild West shows. In these performances moving west and killing Native Americans were associated with moral, cultural, and racial progress. Furthermore, BIA officials discouraged Natives’ participation in Wild West performances a few decades before because they worried it undermined assimilation.19 Indeed, Cloud’s letter to Collier is a challenge to the “commercialization of the Wild West” through public performances, especially insofar as it naturalizes settlers’ colonization of the land and genocide of Native people.

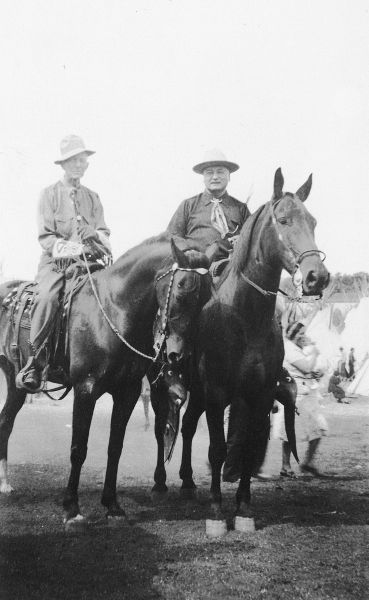

Fig. 15. Cloud in Pendleton, Oregon, at Pendleton Round-Up, serving as grand marshal. He is the rider wearing the dark shirt. His horse was called “Snippy.” Photograph courtesy of the Cloud family.

Beginning in 1910 the Round-Up is Pendleton’s most cherished rodeo event, central to the town’s identity and a powerful symbol of the settler heritage of the white residents. Surrounding Native communities have always been encouraged to participate, and many looked forward to their annual involvement. Each year Indigenous peoples set up camp on the Round-Up grounds and participate in the rodeo. During their first year of involvement, organizers invited Native Americans and U.S. soldiers to perform a pretend battle using blank ammunition. But the Natives refused to be shot at with blank ammunition and the soldiers could not come.20 Symbolic violence was not the only kind of violence. The rodeo can be dangerous, with riders and animals injured and killed. In 1913, for example, three Indigenous women died in a horse race. Dorothy McCall wrote that, in response to these women’s tragic accident, a man in the stands said, “What’s the matter with you people? After all, they’re only Indians!”21 This comment points to racist whites’ assumption that Native women are not fully human, and our death is of no concern.

“Happy Canyon Indian Pageant and Wild West Show” continues today under the guise of a cultural performance about the settling of the American West. It begins with a portrayal of the Native American way of life prior to the coming of the white man. Then Meriwether Lewis and William Clark arrive and, soon after, so do the prairie schooners of the pioneers of the Oregon Trail. Fighting breaks out between Indigenous peoples and white settlers, and peace returns only when Indigenous peoples are taken to live on the reservation. The performance concludes with a reenactment of a frontier town’s noisy and disorderly Main Street mishaps, and, ultimately, Indigenous peoples disappear.22 The title “Happy Canyon” points to the underlying settler-colonial purpose of this Wild West show: the outcome is a happy one, where, as a result of colonialism and dispossession, white settlers and Natives are content. The Happy Canyon performance fits within frontier symbolism and narratives that emphasize the heroic acts of the first pioneers and the explorers’ “discovery” and settlement of the region. The narrative structure of these frontier histories tells of a heroic struggle between the forces of good and evil. Violence is taken for granted and viewed as the motor that drives history-as-progress. In other words, the violence is accepted as the natural progression of the “good” white settler—who must kill “bad” Indians, the impediments to civilization. And ultimately white settlers emerge as the rightful inheritors of the land and resources.

Fig. 16. Cloud at the Pendleton Round-Up. He wears a long dark coat and is being honored with feathered regalia, according to our cousin Susan Freed-Held. Photograph courtesy of the Cloud family.

Cloud offered an alternative to the settler-colonial narratives reinforced by the Pendleton Round-Up and Happy Canyon. Cloud’s request of Collier’s support for a change in Indigenous peoples’ involvement included “the totality of Indian life. . . . To do this, it is necessary to present the arts and crafts along with all the historical features of the aboriginal American, involving the antiquity of [the] Indian on this continent so far as archaeology will reveal, his racial history . . . and the Indian’s particular ethnological background along with the distinctive features of his own culture.” Cloud discussed that exhibits highlighting Native culture and ethnology were possible and that “with proper organization and management,” Indigenous painters, artisans, and singers could be encouraged to perform, turning the Round-Up into a wonderful Indian educational event. He emphasized a growing interest in Natives and wrote, “A study of the cultural background of the Indians has so much of social implication to our modern day civilization loaded with maladjustment of one kind or another. May not America discover something in the evolution of American Indians here on this continent for the last 30,000 years.”23 Cloud’s idea of transforming the Round-Up and “Happy Canyon” from a Wild West show and tourist attraction into an educational event challenged the federal government’s assimilation campaigns. Cloud’s educational events could have encouraged participants to understand cultural relativism and respect Native cultures as equal to Western culture. At the same time, it is likely that the cultural performances he imagined did not expose the colonialism that had caused so much damage to Native Americans.

Cloud worked to open up lines of communication with Collier, who was also trained as an anthropologist, by using their shared discipline’s settler-colonial assumption that one could learn from Indigenous peoples’ cultures—and that this knowledge could help to correct the “maladjustment” of modern society and improve modern culture. In this way Cloud strategically used a dominant narrative that typically romanticizes Indigenous peoples and laments their destruction by the forces of European expansion. In so doing, these narratives project ideal images of the past, contrasting them with the current moral-social decline of contemporary industrial society. Cloud’s use of this dominant discourse allowed him to use a hegemonic historical perspective for a Native goal: transform the white settlers’ frontier pageant into a performance that incorporates Indigenous culture and history.24 Particularly, his use of the term “evolution” alludes to classic anthropology’s assumption that Natives occupy a space on the lower end of a continuum between primitive and civilized. Thus, his utilization of this term is problematic and could point to a hierarchy created within the Native cultural performances he hoped to organize. It also shows how he deliberately used dominant discourses whites would understand to reach his own anti–settler-colonial goals. Cloud’s doubleness speech was a Ho-Chunk creative strategy that aided his ongoing efforts.25

Elizabeth and the Oregon Trail Women’s Club

In 1940, while Henry was working to transform the Pendleton Round-Up, Elizabeth founded the Oregon Trail Women’s Club. This Indigenous women’s organization was the first of its kind on the Umatilla Reservation. It belonged to the white women’s national organization, the General Federation of Women’s Clubs (GFWC). Through both this membership and an affiliation with the Oregon Federation of Women’s Clubs, Elizabeth brought the club in contact with mainstream women’s organizations.26

Even though Native women are mostly missing from the historical literature regarding the (largely white) women’s clubs’ movement around the turn of the century, they were pivotal and vital players. In these clubs white women provided help to Indigenous peoples and other disadvantaged groups. In 1921, for example, the GFWC put Indian welfare on their national agenda. White women’s clubs influenced by the GFWC’s call to action provided paternalistic help to Native Americans. They donated clothing, studied Natives, and wrote to legislators in protest of the mismanagement of Native affairs. They even taught domestic practices to traditional Indigenous women—assuming they were inferior homemakers and caregivers. Indeed, all of these white women’s efforts were done without consulting Natives themselves.27

Margaret Jacobs, in White Mother to a Dark Race, argues that white women were intimately tied to settler colonialism through their involvement in federal boarding schools. In these Native federally run schools, white women reformers assumed traditional Native women were unfit for motherhood. Instead, white women taught young Indigenous girls’ white notions of domesticity and gender roles.28 In both federal boarding schools and mainstream women’s clubs, white women imparted white notions of gender to Native females as part of an assimilationist settler-colonial program.

Yet Indigenous women did participate in these mainstream women’s clubs at an organizational level. Like their white women colleagues, these Native club women were usually middle- or upper-class Christian wives and mothers. They were mostly mixed of Native and white descent and had formal education. These Indigenous women combined their Native and modern identities as they discussed their rights as members of their tribal nations and the U.S. nation-state. For example, by forming the Oregon Trail Women’s Club for Umatilla Indigenous women, Elizabeth used these mainstream clubs to support Indigenous women’s senses of tribal identity, as well as a place for their empowerment.29

Similarly, African American middle-class women used white women’s clubs to help “uplift” their race. These African American women taught poor and working-class African American communities white, middle-class values. While these African American club organizers and leaders have been criticized for supporting white culture and not emphasizing enough African American culture or practices, they have also been revered and celebrated for improving their communities and increasing educational opportunities for African Americans.30 Similarly, Native American club women, who were viewed as “assimilated” and of a higher class than traditional Indigenous women, used these white women’s clubs to support a white worldview, encouraging traditional Native women to become more assimilated. At the same time, just like African American women in similar mainstream women’s organizations, Elizabeth worked to improve conditions for Native Americans. Elizabeth and other Indigenous women in these mainstream women’s clubs occupied a complicated position. They encouraged Native women to mimic white women’s norms and roles—thus implicating themselves in settler colonialism—while encouraging the empowerment and maintenance of their tribal identities. Alongside other Indigenous club women, Elizabeth encouraged Native women to combine their tribal and modern identities.

During interviews conducted in 1988 and 2010, Leah Conner, daughter of a women’s club member, portrayed Elizabeth as strong, gentle, ladylike, and lighthearted. She described the purpose of the club as for Native women’s empowerment. The club developed family and community relationships, helping women take on leadership roles within their tribal community and “improve” their dress and appearance. Conner discussed how Elizabeth encouraged the women to make their own handicrafts—including contemporary buckskin crafts and beadwork—and show these Native arts to others. Elizabeth also encouraged them to have teas and luncheons. Elizabeth encouraged Conner to attend college, which was something she had never considered before. Connor attended Willamette University and the University of New Mexico. She successfully received her bachelor’s degree at Eastern Oregon State College at LaGrand, her master’s degree in education from Oregon State University, and a BFA from the University of Washington. Conner also described the club as the most positive feminine movement on the reservation, comparing Elizabeth to Eleanor Roosevelt, discussing their similar strengths and work ethic. According to Conner, Elizabeth did not just talk about things but took action and was able to get Native women from the three different tribes on the reservation to work together. The Oregon Trail Women’s Club members respected and honored Elizabeth’s role as a teacher and a leader and in 1950 supported her nomination as American Mother of the Year.31

The Oregon Trail Women’s Club was a Native hub under the guise of a settler-colonial name, a subversive trickster strategy of camouflage. Through this subversive naming tactic, Elizabeth secured the support of the GFWC, a settler-colonial women’s organization. Elizabeth used this organization to empower Native women and support the development of modern Native identities.

Henry’s Heart Attack

On September 3, 1942, while Elizabeth was busy organizing the Oregon Trail Women’s Club, and Henry was serving as superintendent, he suffered a major heart attack. I can only imagine how hard Henry worked and how stressful his Indian agent position was. I am certain his busy and taxing job contributed to his heart attack. Elizabeth encouraged their children to return home immediately because they feared Henry might die. My mother, Woesha, for example, traveled from the Jicarilla Apache Reservation, where she was working. She did not leave Pendleton until her father was recovering. Elizabeth wrote Bess Page, Henry’s white adoptive cousin, that Henry “suffered terribly for over a week. . . . He must be in bed from six to eight weeks, and cannot return to work until January the first. Marion and Ed came down from Portland. . . . Henry said to tell you he is coming out with a rejuvenated heart, and a boyish figure. He is cut to 1,200 calories a day. He is able to joke a little, so I know he is feeling stronger.”32

Page responded to Henry that he should starting thinking about some of his priceless Winnebago [Ho-Chunk] material: “You know better than the rest of us how important it is that memories such as yours get onto paper. You know back in your mind you have had the thought of writing up the medicine lodge lore of your uncle and grandfather, and your early pre-school experiences, but you never had time for it. . . . Do try it. You have in Elizabeth an excellent critic right at your elbow.”33

Henry answered in a letter of September 28, 1942, emphasizing his love and sense of family was all-encompassing, contained both Natives and whites and supported his sense of a Ho-Chunk–centric hub, including family near and far, and his beloved horse, Snippy.

While for the moments, I am concerned to know from my physician as to whether or not I am to give up my riding horse, “Snippy,” and very much loved game (golf). (I was stricken while out practicing golf at 7:30 am on Sept. 3rd). I shall make these sacrifices if it is necessary. You have struck a very responsive chord in me when you outline a writing future. I may have been spared to do just such a line of work by which America may get a better understanding of the Indian. . . .

My little Grandson, “Buzz,” (nick named by me) left me today for Portland with his parents. He looked so sweet in ribbons and woolens. He is twenty days old today taking his first extended trip. He name is “Edward Roe Cloud Hughes.” He is the first to carry on the name “Roe” and “Cloud.” My other little grandson waiting in heaven [who passed away] with my little boy and namesake was called “Michael Henry Freed.” These dear daughters of mine draw me closer to them by naming their little ones after me.

Ramona [his daughter] left for Vassar Saturday night this week. She looked radiant as a senior at Vassar now and so happy to leave knowing full well that I am now clear out of the woods. . . . I’m only weak from losing 30 pounds. . . . My face for once shows rather high cheekbones. . . . Indians have sent wild flowers from the mountains here. Neighbors have brought eggs, corn and jars of jelly. . . . I had preached six Sundays in succession, and carried on the work of the superintendency at the same time when the blow came. I had hurt my leg, and went on crutches to the pulpit. The load may have been heavy, but the joy was great too.34

Henry chose to use “Roe” as his middle name, since the Roes informally adopted him as their son. His daughter Marion passed down the name by giving her son “Buzz” the name Roe as his middle name. Henry relied on the Roes while he was a Yale student, as discussed in chapter 1. Henry and Elizabeth reached out to whites as integral to their work for the betterment of Native Americans. Yet, as discussed in chapter 2, Mary Roe’s relationship with Henry as a colonial mother was challenging and difficult. I chose not to continue using the Roe name throughout much of this book manuscript in an effort of decolonization. My choice might be challenging for some, as Henry decided to use Roe as part of his name, and I sincerely believe he did love Mary and Walter Roe. As a Native feminist scholar, however, I argue his decision to become their informally adopted son was influenced by his highly racialized settler-colonial environment, where Native men were seen as nonmen and as children and lower on the evolutionary scale than whites, and he suffered deeply as an orphan after losing his Ho-Chunk mother, father, and grandmother from a horrible flu epidemic. In other words, Henry very likely felt that he had to make a family connection with the Roes to be successful in the white environment of Yale University, including receiving loans. At the same time, I want to honor the positive aspects of Cloud’s loving relationship with Bess Page, Cloud’s white adoptive cousin, who supported Henry as he was convalescing in the hospital after his heart attack. She also urged him to write about Ho-Chunk culture, respecting him as a Ho-Chunk intellectual. And her encouragement of Henry shows how, to some extent, he had “Nativized” Bess. She emphasized her appreciation for Ho-Chunk culture and took part in Cloud’s sense of a Ho-Chunk family or hub. This letter also shows how much he loved and stayed connected to his grandson, who was alive, and his grandson and son, who had passed away.

When Cloud left the hospital, Dr. J. P. Brennan advised that he take at least two months off from living at an altitude of 1,100 feet in Pendleton. This meant he had to leave the reservation and take a break from the terrible strain of his job. Elizabeth and Henry decided to stay with Ed and Marion Hughes, their daughter and her husband in Portland, from mid-November 1942 until the end of the year.35

Henry and Ho-Chunk Studies

In 1944, while Elizabeth was busy working with the Umatilla women as part of the Oregon Trail Women’s Club, Henry wrote another correspondence to his adopted white cousin, Bessie. They exchanged letters about how to examine history from a Native American perspective. She had sent him her chapter about Indian and white relations in Virginia in the 1600s and requested his feedback.36 In response, he wrote,

After ten or more points you bring out as to why the Indians attacked the English so violently in 1622 in Va. [Virginia], I think more should be made of the fact of the Indian dispossessed. Show how this process can be so painful to them.

According to the English Diaries the English looked upon the Indians as inferior, fit to be servants to the English and as the Indians occupied the best corn lands, most fertile spots to be found in the country enjoyed the deer and wild fowl, the English longed for these very lands and as shiploads of them came over there was need for more and more of this land. Then too their domesticated animals ran all over the place destroying cornfields causing disturbances not only in Va. but also in other settlements. If there is one thing an Indian resents, it is to be thought of as inferior. As a matter of fact, he thinks or measures himself as superior. . . . Hence pride is one of the most outstanding of Indian nature. Yet was it not [Jonathan] Yardley who took Opechancanough [chief of the Powhatan], by the back of his hair and utterly humiliated him for corn? No man can do that to a chief and not hear from it later. An Indian never forgot such arrogance. He was humiliated by that act [in front of] the whole tribe. . . .

They [English] people prospered on corn, tobacco, cattle, swine and poultry on lands which the Indian considered rightfully his own. They ruthlessly disinterred the bones of the leader of the Powhatan federation, Powhatan in 1621. The resting place to the Indian is terribly sacred. . . . Above all things to alarm the Indians were the English’s imported epidemics. . . . In these times, Indians are losing their lands by the loans ostensibly made as a gesture of friendship on the part of the whites, and then find themselves dispossessed of their lands later when unable to repay. . . . If you put these very strong elemental feelings of the Indians which interpreted by the Indians as jeopardizing their existence then the attack assumed economic, racial and rancor from high handed treatment as casus belli rather than cruelty per se.37

In this quote Cloud makes a convincing analytical case against settler colonialism, discussing how the actions of the English—dispossessing Natives of our land, humiliating our chiefs, digging up of the bones of Powhatan, treating us as inferiors, bringing disease, and jeopardizing Natives’ very existence—should be viewed as justification for Natives’ acts of war. He discusses how the English’s disrespectful behavior would encourage Natives to fight back. His Native-centric view of history attacks the underlying assumptions that work to normalize settlers’ behavior to dispossess Natives of our land. Settler-colonial histories describe a heroic fight between good and evil, seeing Native Americans as evil and settlers as good. Cloud undermines this good-versus-evil binary by asserting that Indigenous peoples were justified to wage war against the English, and their behavior was not “cruelty per se.” He contests seeing white settlers’ behavior toward Natives as based on goodness, friendship, or benevolence by discussing the land loss, when Natives could not pay back the loans provided by the English “ostensibly” as gestures of friendship.38 He exposes how settlers profited from their occupation of stolen Indigenous land. Moreover, Cloud’s intelligent and perceptive consideration of how the English’s maneuvers revolved around land dispossession and economic pursuit reveals how colonialism works.

Cloud’s analysis of the English’s colonial behavior and his highlighting of a Native warrior perspective demonstrates his overall ability to discuss a Native approach to history, and how his Ho-Chunk cultural perspective was vital to his intellectual inquiry. In these ways his intellectual analysis is foundational to the creation of Ho-Chunk studies, which includes later scholars such as Amy Lonetree, Truman Lowe, Tom Jones, David Lee-Smith, Woesha Cloud North (his daughter), George Greendeer, Angel Hinzo, and Allen Walker.39 Cloud labors to open lines of communication between himself and his white cousin Bessie, urging her to comprehend Natives’ rightful retaliation against the English’s unfair treatment. By trying to sensitize Bessie to a Native approach to history, culture, and colonialism, Cloud developed a supportive Native hub or network in the midst of his white family, helping him maintain his identity as a Ho-Chunk man and an intellectual.

Elizabeth and Umatilla Native Women Unite in Protest

A few years later, in 1946 or 1947, the Native women at Umatilla joined with Elizabeth Bender Cloud to denounce an article written by a Portland writer, Elsie Dickson, who was the white woman called “The Hat,” for her stylish bonnet. The title of her original article is unknown but appeared in the Elks Club’s national magazine. It described Dickson’s experience at the Pendleton Round-Up. The matter was summed up in a second article by Elsie Dickson that appeared in a local paper, “Indians Heap Provoked Blonde Writer ‘The Hat’ May Lose Part of Scalp,” where she interviewed Elizabeth Bender Cloud. Dickson wrote that the women of the reservation denounced her original article “through Mrs. Henry Roe Cloud . . . herself head of Indian Women’s Affairs, Oregon Federation of Women’s Clubs,” who had found the following excerpt offensive:

Since the Indians accepted only silver dollars, a man with a sack was posted at the exit to dole out the money. It was also part of the Round-Up tradition to shoot any injured steer and hand it over to the Indians for a barbeque. Squaws used to flock like flies around a carcass until not so much as a grease spot was left on the grounds.

Indians are still hard-money people but they’ve raised the ante considerably and when a steer is handed to them they delicately cut off the hams and leave the rest where it lies. Like the rest of the rodeo, they’ve turned it into big business.40

In this quote Dickson racializes Native women as squaws and compares them to flies—two dehumanizing and colonial blows. Dickson points to Natives’ exploitation as part of “big business.” She describes how impoverished Natives would cut off a portion of meat and leave the rest, portraying Natives as wasteful—a common settler-colonial construction.

Elizabeth Bender Cloud told Dickson the following in order to set the record straight:

In reply to this, the Indian women state: “Meat issued to the Indians at the Round-Up has, for the last 15 years, come from the city butcher shops. Some two years ago, however, one injured steer was killed and from this one Indian man was allowed to cut off two hind quarters and the rest went to the slaughter house.

No carcasses have been left over which the Indians could flock like flies. And Indians, as a group, have long ago abandoned that conduct of life which would cause sickness and infection diseases among them. At the 1946 Round-Up the federal government maintained a man to spread disinfectant to rid the Indian encampment of flies. This was in addition to a supervising nurse and helper.

Indian self-respect and morale are fostered by such measures, and the Indians, themselves, are proud and grateful.

Not an Indian on this reservation would eat until “not so much as a grease spot would be left on the grounds.” Hoover may have met such type of eaters in Europe, but it is not so on the Umatilla Reservation.41

The Native women, unfortunately, used settler assumptions in their response. When they emphasized Natives no longer left carcasses that drew flies and expressed gratitude for a federal-government employee spreading disinfectant, they portrayed themselves as “good” Indians. As integral to settler colonialism and the elimination of the Native, white settlers viewed us as inferior and in need of civilization to remedy our inherent deficiencies.42 Elizabeth and the women of the Oregon Trail Women’s Club, as modern warrior women, voiced their anger and fought back against racist epithets of Native women and Indigenous people overall. They said Natives were not wasteful and the unused meat was returned to the slaughterhouse. Therefore, the Oregon Trail Women’s Club seemed to be also a training ground for teaching Native women to become warrior women.

The Oregon Trail Women’s Club’s twenty-five members showcased Native American culture at the GFWC’s national convention held in Portland. They made miniature sets of moccasins for table favors and showed a pageant of Indian fashions, named “The New Look in the Long Ago.” Elizabeth spoke and Henry attended as an important guest.43 Elizabeth very well could have named the Native fashion show, and choosing this title was an Indigenous intellectual challenge to dominant assumptions of Natives. Rather than portraying Natives as static relics of the past, whose Native culture and presence were vanishing, the title asserts a creative combination of traditional and modern, emphasizing that Native women were staying Indigenous into the present day. Furthermore, Henry’s presence in the audience shows his support of Elizabeth’s subversive work with the Native women of Umatilla.

The Indian Agent’s Role in Umatilla Reservation’s Challenges

In 1939 Natives of the Umatilla Reservation confronted particularly difficult issues. The reservation is a consolidated agency with tribal members of the Umatilla, Cayuse, and Walla Walla tribes. The diversity in membership led to a considerable amount of intertribal tension and factionalism. There was incredibly strong and intense struggle and conflict regarding salmon fishing and land grazing between whites and Natives, and Cloud, as the new superintendent, had to make decisions about the distribution of these resources. Meanwhile, white settlers built dams on the Columbia River, threatening the already dwindling salmon population, which was a crucial resource, supplying greatly needed income and food for Natives. As superintendent, Cloud coordinated the agency’s reaction to these various threats, often with a limited budget. And this budget continued to decrease in the late 1930s and early 1940s, as the country turned its focus on the war and away from Indian New Deal’s agendas.44

On October 10, 1941, early in his ten-year career as an Indian agent, Cloud spoke before the Wildlife Society at the chamber of commerce in Pendleton, Oregon. During this speech Cloud emphasized Ho-Chunk and Indigenous perspectives on “conservation,” a settler-colonial term:

My few remarks tonight, I hope, will show something of the Indian attitude on the question of the conservation of game. If the same should be destroyed through uncontrolled, wanton destruction the white hunter cannot hunt for sport and the Indian hunter cannot hunt for subsistence.

To my mind, conservation of game is justified not so much to supply hunting of opportunity to the white man for sport and to the Indian for subsistence. Conservation rightly viewed is for national self-sufficiency—to preserve the balance existing for ages in nature and for ultimate national defense.

Conservation of game bulked large in the Red Man’s philosophy. According to tradition animals were created before man. Priority of existence carried to the Indian mind the endowment of greater powers. The great Creator gave the animals something more than He gave to man. Animals therefore were akin to the beings known as supernaturals. Animals belong to the category of creatures meriting worship and adoration from man. It was believed that the animals also could do the work of supernaturals. These [supernaturals] had power and control over the Red man’s most vital interests—over sickness and health, victory or defeat in war, success on the hunt and chase. In the foregoing I have used some big words simply to say that when the Indians’ respect for the animal kingdom amounts to a religion, wanton destruction of game can find no room in his thinking. Such practice has never been heard of in Indian experience. From time immemorial game was the means of subsistence for the Indian. Its conservation meant self-preservation of the Indian race itself. . . .

When Indians killed deer, buffalo or any other game they never wasted any portion or part. The hair was made into mattress material. Pads were made of it while it was wet for pack saddles. Ropes were made out of buffalo hair. Indian trunks were made out of buffalo hide. The tail was used for head dress, and in buckskin dresses. The hoof was heated to be cut for ornamental dress purposes. When cut and strung, it had a clear, ringing sound. The Indians ate the inside of the hoof. Tripe was cut, its contents emptied, cleaned thoroughly and cured by smoking for winter food, or boiled for eating immediately. The lungs were soaked for winter use. The bones were cut into pieces and preserved for soup making in winter. It was cut very thick and hung up. Sometimes it was broken up for tallow by making it into cakes. The meat was sliced very thin and hung to dry in the sun and also inside the tepee. The ear a most valuable dish for the Indian. The skin was peeled and the ear gristle was eaten as a great delicacy. The hide, Indians made into gloves, moccasins and ready to wear clothing. The horns were used for drinking purposes, rings for decoration of the hand, awl handles for scraping hair off the hide. Elk hides were used for robes with hair retained like buffalo robes. When hair is removed, Indians use it for blankets and robes, and for panoply decorations with long fringes on horses. The bearskin being waterproof was used for drum coverings and as throw rugs.45

In this speech Cloud as a Ho-Chunk intellectual emphasizes how Natives relate to animals. For Indigenous peoples, Cloud argues, animals are integral to religion and spiritual philosophy and even valued above humans—as opposed to the whites’ assumption that humans are superior to animals. In this way Cloud tries to create understanding between whites and Natives about vastly different approaches to conservation. As opposed to white hunters, who killed animals for sport, Natives relied on hunting to feed their families. They used every single part of the animal for multiple purposes, and this approach, Cloud argues, supports “self-sufficiency,” “national defense,” and the future of the nation. He argues for a Native and environmentally sustainable approach to hunting and conservation that could ultimately contribute to humanity’s very survival as human beings. His Ho-Chunk intellectual work recalls his commentary on Bessie’s manuscript, when he insisted on a Native perspective. Similarly, he argued to Bessie that choices Native people made were extremely rational. Thus Cloud repeatedly defied the stereotypes that Natives were less intelligent than whites and lower on the socioevolutionary scale. Cloud not only opened up lines of communication between whites and Natives but also validated Indigenous knowledge and perspectives to define conservation and contributed to Ho-Chunk knowledge and studies.

Cloud deeply respected the Ho-Chunk approach to hunting he learned from his relatives, who had a close spiritual connection to animals. For example, Henry cherished the large buffalo hide he used as a blanket. According to his son-in-law, Raleigh Butterfield, Elizabeth would tease him and say, “That thing is so heavy. How can you sleep under that? It’s so heavy it will crush you!”46 Cloud’s buffalo blanket not only kept him warm at night but also could remind him of fond memories of his childhood on the Winnebago Reservation surrounded by his Ho-Chunk family. This buffalo blanket symbolized his Ho-Chunk hub that protected him and kept him warm throughout his life. Through this hub he connected to his Ho-Chunk identity and tribe, despite his geographic separation. The blanket also might have elicited beautiful childhood memories of learning to hunt, respecting the animals one killed, offering prayers for the animal, and seeing the sacrifice of one’s life for another’s survival. Indeed, Henry and Elizabeth, with other family members, would hunt and fish together in the gorgeous mountains and streams surrounding the reservation. These trips must have also supported Ho-Chunk and Ojibwe hubs, both of them possibly connecting to memories from their childhoods with their beloved relatives on their reservations.

Cloud’s Support of Native Fishing Rights

Potentially one of the earliest letters ever mailed to Cloud as an Umatilla Indian agent concerned fishing. On August 17, 1939, the Yakima Indian agent, M. A. Johnson, sent him a copy of the correspondence he had already mailed to the commissioner of Indian Affairs. Johnson wrote about the negotiations between the federal government and tribes about restitution for damage to and loss of Native fishing and camping sites caused by the flooding of land behind the Bonneville Dam. The federal government’s proposal included the purchase of six replacement sites. Eventually, the tribes and Johnson agreed to the proposal and requested the secretary send additional instructions. Johnson wrote that the settlement should not be viewed as reimbursement “for the loss to the run of the fish which may develop in later years due to the construction of Bonneville Dam.”47

Whites damming the Columbia River and flooding numerous spiritually vital fishing sites caused much pain and sorrow for Native Americans of the Pacific Northwest. Rivers are dammed to provide more water for farming, electrical power, and other uses, but in the process the rushing water kills plants, animals, and many living things. The survival of Natives depended on fishing for thousands of years. The fish were considered a gift from our Creator, so losing access to fishing places marked not only the depletion of an important food source but also a spiritual assault. Natives can no longer walk on our sacred lands, connect to our Creator, or witness the beauty of the amazing river. We can no longer give thanks to the fish for offering their lives for our survival. Throughout the twentieth century the cultural differences between Natives and white settlers played out on the stage of the Columbia River and its surrounding lands, on the lives of animals and fish. Still today Natives believe our people and what white settlers call “nature” are one. Our Creator provides fish—and all life—for sustainable use, not wanton exploitation.48 This cultural divide and conflict also points to the process of settler colonialism working not only to eliminate Native peoples from our land as integral to building dams but also to control nature for monetary profit.49

Fig. 17. A proud Elizabeth showing off fish caught on a fishing trip with her beloved Henry near Pendleton, Oregon. Photograph courtesy of the Cloud family.

Natives were the first ones to exchange fish for other goods in the Umatilla Valley. In other words, Native Americans had their own “monetary system” that relied on fish as a unit. In 1944 Cloud asked tribal members from the three Umatilla tribes to compile a list of items their ancestors bartered for in exchange for fish. He learned that they traded fish for drums and cradles, beaver medicine bags, snowshoes, shields, tomahawks, ropes and rawhide thongs, natural dyes, baskets, cooking utensils made of wood burls, mortars and pestles, scrapers for hides, obsidian and flint knives, arrowheads, dressed buckskin, elk and deer meat, buffalo, roots, saddle blankets, buffalo-hide tents and teepees, pipes, bows and arrows, wampum, buckskin clothing, and buffalo robes.50 This wide range of goods received in exchange for fish shows how valuable fish were to Umatilla Natives. Fish provided them with food and an incredibly long list of needed supplies, cooking utensils, and precious spiritual items. In effect, fish functioned as money, refuting white settlers’ assumptions that Natives were “undeveloped” and needed to learn to make “productive” use of animals. Furthermore, when settlers built dams, millions of fish died, Indigenous camping and hunting sites were flooded, and the Indigenous peoples’ survival methods greatly decreased. In other words, dams significantly contributed to widespread poverty. Cloud likely collected this information to use it as ammunition in support of tribes’ struggles for reparations for losses caused by the flooding caused by dam building.

Natives’ legal rights to catch fish were based on 1855 treaties between tribes and Oregon governor Isaac I. Stevens. But, in 1939, when Cloud was superintendent of Umatilla, the interpretation of the treaties had become controversial. One 1855 treaty, article 3, states, “The exclusive right of taking fish in all of the streams, where running through or bordering said reservation, is further secured to said confederated tribes and bands of Indians, as also the right of taking fish at all in the usual and accustomed places, in common with the citizens of the territory, and of erecting temporary building for curing them.”51 Whites could mistakenly view this provision not as protecting Natives’ right to fish but as allowing them to fish too.

The treaties of 1855 proclaimed the coming of a new order on the Columbia Plateau. To acquire title to Indigenous lands, while forcibly removing Natives to reservations, the U.S. government had to designate signatory tribes, delineate their differing regions, and determine appropriate “head chiefs” for negotiations. Federal officials partitioned the land into ceded areas, broke up kinship networks, and grouped inhabitants into confederated tribes, which encouraged later strife. Before the treaties it was kinship that structured access to prime fishing sites, not one’s status as a “treaty Indian” or not. As soon as Cloud became superintendent, he worked to protect Native fishing rights. As part of his role, he was in charge of the Celilo Falls fishing site. This meant frequent, 225-mile trips to and from Celilo for meetings of the Celilo Fish Committee, which was made up of three members from the reservations as well as representatives of the Indians who lived at Celilo and Rock Creek, to the southeast.52

The Columbia River Natives (who were not federally recognized) and members of tribes from the Umatilla, Yakima, and Warm Springs Reservations all had the right to fish at Celilo. But they were in constant disagreement with one another and whites over the fishing sites, partly because Natives had only seven and a half acres on which to camp and fish. Cloud also advised the Celilo Fish Committee, a local intertribal body organized to help govern the activities of the Native fishermen at Celilo Falls. This committee originated in 1934 to negotiate settlements, resolve disagreements, and provide a (somewhat) unified Indigenous voice in debates about the salmon catch on the upper Columbia River.53 Cloud was a de facto member of the committee. He acted as an adviser. During his first three years as an Indian agent at Umatilla, his involvement with the Fish Committee likely took up most of his time. Cloud balanced and represented various points of view in his role. Dreading losing state cooperation on other matters, the Indian Service took nearly an ambivalent position on Native treaty rights regarding off-reservation fishing. The Fish Committee needed a strong supporter of Indigenous treaty rights, and the Umatilla Natives asked Cloud to advocate for their particular tribal interests too.54

There was much distrust between the tribal nations who shared Celilo Falls. By court decision Yakima Natives, for example, were given access to the site a short time ago, and the smaller tribal nations disliked sharing the fishing site with the three-thousand-member tribe. The smaller tribal groups also resisted the Natives of the Warm Springs Agency from being allowed to fish and have access to Celilo Falls. Cloud often was compelled to act as both mediator and manager among the various groups. For example, Cloud was a leader, who persuaded the superintendents of the reservations who fished at Celilo Falls to agree to the Fish Committee’s strategy to give identification cards to authorized Natives so that the police could identify trespassers at Celilo Falls.55

Cloud discussed his involvement in the Celilo situation in an interview after he left his post as superintendent of Umatilla. He remembered working with other superintendents to improve the difficult living and fishing conditions at Celilo by trying to gain funds from the federal government:

Fortunately, I have ten-year experience with the Celilo situation. Chief Tommy Thompson and his small band belong to the Warm Springs Agency, Warm Springs, Oregon. . . . This small band at once surrendered all their rights under the 1855 treaty and became thereafter virtual squatters on the Celilo fishing location. The treaty Indians, on the other hand, namely the Umatilla and Yakima tribes, did not oust this small band of Indians but permitted them to continue this occupation of the Celilo fishing site. Reasons of humanity, moral considerations, beside [sic] Indian generosity have been exercised in Tommy Thompson’s favor. The Federal Government on its part have [sic] not pressed the technical requirements of law under the treaties but have proceeded to remedy the untoward situation at Celilo.56

Cloud calls Tommy Thompson and his people “virtual squatters,” because they were not treaty Indians and from a colonial perspective had legally lost their “right” to live and fish at Celilo and were therefore legally trespassers and unlawful tenants. He then discusses that it was “humanity, moral considerations,” and “Indian generosity” that stopped Umatilla and Yakima Natives from ousting them from living and fishing there, and that the federal government also did not follow the technical requirements of the law. Cloud’s discussion demonstrates how Natives challenged the naturalizing of settler-colonial constructions based on treaty-related legal definitions regarding who could live and fish at Celilo. His statement also shows how the federal government did not rely on these settler-colonial constructions either, not forcing Tommy Thompson and his people from leaving Celilo. Further, choosing not to oust Tommy Thompson and his people was a way to honor Native kinship.

Natives and non-Natives had overwhelmed the Celilo fishing area. Starting in the mid-1860s the use of industrial processing and canning techniques transformed the salmon runs of the Columbia River into a profitable commodity. Specifically, Seufert Brothers Company, the biggest packing operation, deteriorated the problems at Celilo. In 1930 the company made several cableways that connected the Oregon shore to various islands. The company would rent the cables to Natives, and they could climb into a fish box and use a zip line to ride above the roaring waters to stands built on the opposite shore, where they could fish. This cable system drew an increasing number of newcomers to Celilo. Most were Natives from reservations, who wanted to make money from selling fish, because the damming of streams, including the Yakima and Umatilla, had pushed many Indigenous peoples away from traditional fishing sites. Local Indigenous peoples and others from as far away as Alaska joined the crowds of whites in search of seasonal work and economic relief from the Great Depression.57

While Cloud was Indian agent, he used his settler-colonial position to gain additional monies from the federal government for the Natives at Celilo. He continued in the same interview after he left his post: “For ten years as Superintendent of Umatilla Indian Agency, I with the superintendents of Yakima and Warm Springs struggled to bring about Congressional appropriations for Celilo. We worked for $250,000.00 and finally got only $125,000.00. This amount was adequate for only the major improvements, namely housing, drying sheds, water system, electrical utilities and sewage disposal. The crying need for an underpass and road to the fishing locations will have to come from the railroads involved and the State of Oregon. The State Highway Commission should get busy with their improvements.”58

Sampson Tulee Court Case

The Sampson Tulee court case presented Cloud an additional opportunity to act as mediator. A Yakima Native, Tulee fished at Celilo Falls. He, along with other Natives who fished there, struggled with Washington State laws developed to regulate and control Indigenous people’s right to fish. The state had never been very welcoming of the Indigenous fishermen. By 1937 Washington enforced license fees on them. Natives immediately protested, arguing that these fees violated the 1854–55 Stevens Treaties that protected their right to fish without state interference in the “usual and accustomed places.” Washington State and Indian Service officials anticipated that Tulee’s case would resolve this treaty-related conflict and issue. After Tulee’s arrest his case began its journey through the court system.59

Cloud and Celilo fishermen monitored this case closely. Like most treaty-related cases, it was not decided quickly. The Fish Committee regularly gave Tulee’s family fish since he was in jail for close to a full year—an instance of them taking care of community members. Because state officials avoided working with the Fish Committee, Cloud became the negotiator, who argued for Natives to continue to fish at the site while the case moved through the courts. In the beginning Natives were allowed to fish if they had fishing licenses. Eventually Cloud and others persuaded Washington State not to charge Natives the fees for fishing licenses until after the ruling.60

In late 1942 the Tulee case was resolved, even though obscurely. The Supreme Court decided that the state could not collect license fees if the objective was to limit Natives’ right to use traditional fishing sites. In this aspect Natives won, as the court determined that requiring Natives to have fishing licenses was illegal. The court, however, also ruled that the state could still control the Natives’ catch and fishing seasons for conservation purposes. This judgment gave the state wide-ranging powers over Natives. Around eighteen months later, in the fall of 1944, the Northwest superintendents’ council was still uncertain about what the decision meant for their reservations and jurisdictions. They delegated Cloud the job to examine the Tulee decision and present his findings at their December meeting.61

Cloud gave a speech at the December 8 and 9, 1944, Northwest superintendents’ meeting. He discussed the distressing purpose of reservations:

The reservation so-called in our American history came into being for the first time in this particular Northwest area in the process of this treaty making. . . . The creation of a reservation at that time was as everyone knows, for the purpose of keeping Indians in subjection by confinement in limited areas and particularly to protect and encourage settlement of the country by whites.62

Cloud’s analysis of settler colonialism as based in land dispossession and the removal of Natives to reservations reveals how Indigenous intellectuals were discussing the reality of colonialism almost eighty years ago. And this early analysis laid powerful groundwork for present-day discussions of colonialism and struggles for Native rights in Indigenous studies. Settler-colonial discourse, according to Penelope Edmonds, imagines Natives and their relationship to land as an earlier stage of human development, prior to private property. This evolutionary logic legitimized the violent and “legal” dispossession of lands without Native consent.63

Cloud emphasizes, from an Indigenous perspective, Natives’ right to fish in locations both on and off the reservation—in the “usual and accustomed places,” according to the 1855 Umatilla, or Yakima, Treaty. In his talk Cloud makes it clear he was not a lawyer, which explains his qualifying assertions with “my personal opinion” and “the purposes of discussion”:

[For] the purposes of discussion today on this important question, I will state as my personal opinion that the legal status of “usual and accustomed places” outside Indian reservations in the light of the Yakima or Umatilla Treaty of 1855 is the same as the status of the reservation proper. I think you will grant me the contention that there were Tribal domains clearly recognized by all tribes as affording Indian tribes more than sufficient wildlife resources to maintain that standard of living to which they were accustomed. Inter-tribal wars came about when tribes invaded these respective domains at the time when the treaty was made. These very domains were clearly comprehended as economic units in terms of hunting and fishing by Governor Stevens and the United States Commissioners who spoke on behalf of the United States. The Indians no less comprehended for no one knew their environment as they did. A glance at the original exterior boundaries of these domains set apart at that time is proof sufficient of this fact governing the situation.64

Cloud uses the dominant logic of economics to enlarge fishing rights to include hunting rights, a Native-centric objective. This shows how Cloud utilizes the colonizer’s language for Native goals, as he did previously, when he fought for Geronimo’s freedom and support of the Fort Sill Apaches’ struggle over land with the federal government. Once again Cloud’s mixture of Native and dominant rhetoric is a form of doubleness speech, using colonial language for Native objectives.

Again linking hunting and fishing, Cloud argues that the “domain” where Indians fish and hunt are protected under the treaty. In the same speech to other superintendents, Cloud said,

As a matter for discussion only, I will say that the activity known as hunting and fishing denoted an Indian economic activity. This activity was the outgrowth of the problem of self-preservation. While “fishing” as such might be termed as an enterprise by itself of our coast tribes, Indians in the Northwest area carried forward this means of making a livelihood along with hunting as an inseparable unit of activity. Game and wildlife abounded along the wooded areas of streams as well as fish in the rivers. The domain reserved under the Treaty was an economic unit which could not be torn apart and parts or portions thereof defined as having certain specific activities and rights as distinct from certain other parts or portions with activities along with excusive rights or privileges. There is no denying the fact that the Supreme Court considers a fishing case as the defendant Sampson Tulee was taken in the act of fishing. The place involved may have also been an exclusive fishing area.65

Cloud continues to expand fishing rights to include hunting by arguing that Natives’ perspectives of their treaty includes both hunting and fishing and that whites’ perceptions of the law does not influence Natives’ own legal conceptions of their treaty. In this way Cloud emphasizes an Indigenous perspective of the treaty, stressing that white perspectives are irrelevant and Natives deserve rights, because they gave up huge expanses of land in exchange:

It is well to state that Indians believed their treaty was one law and hence to them it meant that one law governed their hunting and the same one law governed their fishing. What legal decisions the whites came to about their fishing as such did not alter one iota their conceptions as to the inherent meaning of the treaty agreement to them. The courts have been wont to declare that this treaty must be interpreted in the light of the understanding the Indians had of its intrinsic meaning. The Indian understood the Treaty that he was protected in his hunting rights in consideration of the vast territory be relinquished to the whites. This meant that he had the utmost freedom to hunt and fish within the boundaries of his reservation, as well as along streams bordering his reservation and also in the “usual and accustomed places.” One phrase of the treaty has apparently been allowed to go by default as the “usual and accustomed places” were guaranteed to them along with the guarantee of the reservation itself. Everyone knows their guaranteed usual accustomed places outside the reservation boundaries have been allowed to be occupied one after the other until now hardly any usual and accustomed places remain notwithstanding the fact that a hundred or more such places have been surveyed and claimed as such by delegations of Indians of the many such locations have been allowed to be claimed—dams have destroyed many and civilization’s water pollutions have destroyed many others.66

While Natives as part of their treaty had been guaranteed to hunt and fish both on the reservation and in their “usual and accustomed places,” Cloud astutely emphasizes, white settlers had overrun many of these Indigenous sites. Places had been lost to flooding caused by dams and water pollution created by settler-colonial industry. In other words, Cloud strongly implicates white-settler society and civilization as the cause of Natives’ loss of their treaty-guaranteed hunting and fishing sites. As such, Cloud ultimately challenges the impact of settler colonialism, again showing his Ho-Chunk–centric intellectual lens.

Cloud ends this speech with a discussion how the state of Washington was already ignoring the Supreme Court ruling: the state closed the Klickitat River to Native fishing. Cloud argued that this prohibition goes against the Tulee Sampson decision:

The bold claim has been made here by me that the state is now at liberty to enforce conservation measures inside an Indian reservation by restrictions as to hunting of a regulatory nature. Our Department attorneys have taken the stand that this move for conservation of game by the state must confine itself to regulation and most important of all it must be reasonable regulation. It is my understanding that the present Klickitat fishing case takes the aspect of absolute prohibition as opposed to regulation on the part of the state. The state has not imposed seasons, limits, or kind of catch but simply has closed an area of certain dimensions. This is an instance of unreasonable regulation for the purpose of conservation as a locality protected by treaty.67

Through the example of the Klickitat fishing site, Cloud reveals the federal government’s conversation measures as merely a way to control treaty rights. He also contrasts the state and federal definitions of the ruling here, as both are concerned with regulating Native fishing. The word “conservation” is imbedded in settler-colonial environmental discourse that juxtaposes dominant society against Natives’ treaty rights to fish. Settlers believe they have a right to control the waterways to protect fish as an exploitable resource, ultimately interfering with Natives’ treaty rights to fish in the “usual and accustomed places.” But, using a Ho-Chunk–centric lens, Cloud argues that the government’s action is an “unreasonable regulation” that goes against Natives’ fishing rights.

Cloud’s Ho-Chunk intellectual stance, in support of Natives’ treaty rights, foreshadows the powerful 1960s Indigenous activism. This movement, based on treaty rights, resulted in huge political, social, and educational gains. During the 1960s and later, returning to the treaties was a favored tactic for Natives to struggle for tribal sovereignty, self-determination, and power. Thus, Cloud’s appeal to the treaties in his fight for Indigenous rights was a harbinger of activism to come, breaking crucial intellectual ground in Native studies.68 Cloud’s analysis of the treaties could also point to a larger intellectual conversation among Natives that predated the 1960s and the Red Power movement, which anthropologists, historians, and Native-studies scholars need to explore today. Similarly, Cloud’s astute intellectual insight and development of a Native-studies curriculum at the American Indian Institute precede the formation of Native Studies programs on university campuses largely as a result of Indigenous activism of the 1960s.69 His daughter and my mother, Woesha Cloud North, took part in the powerful 1960s Indigenous political movement. She taught at Red Rock School on Alcatraz during the Native occupation of the island, and she fought for Native rights. She must have heard about Henry’s struggle in support of tribes’ hunting and fishing rights, and perhaps his fight encouraged her role in the occupation of Alcatraz Island. She also could have listened to her mother discuss her support of Native women joining male-dominated tribal councils as part of her involvement in the National Congress of American Indians, as discussed in the next chapter. Her parents’ labor as Native activists and intellectuals could have influenced her decision to live on Alcatraz Island during the Native occupation. Her parents’ work as Native intellectuals also must have motivated her to teach in Native studies at colleges, such as San Francisco State University; California State University, Fresno; and University of Nebraska, Lincoln, where she ultimately received her doctorate in 1978.

Cloud’s Vexed Role as an Indian agent

At the beginning of Cloud’s tenure as an Indian agent, Umatilla Natives welcomed him as a Native superintendent, which was unusual in the Indian Service at that time. Omar L. Babcock, the superintendent who preceded Cloud, had served one of the longest terms in the Indian Service. He had been the superintendent when Cloud was growing up on the Winnebago Reservation close to forty years before. This fact was emphasized in the press. Babcock controlled the agency strictly and was the kind of Indian agent Cloud frequently condemned. Under Babcock there was little participatory democracy for Natives. In contrast, the tribal council preferred Cloud’s comparatively open and informative manner.70