CHAPTER V

THE LOWER EXTREMITY

THE lower extremity comprises:—

- The buttock.

- The groin.

- The thigh.

- The knee.

- The popliteal space

- the leg.

- The ankle.

- The foot.

- The toes.

The buttocks are the massive parts of the body which lie at the bottom of the back on each side of the middle line. With the exception of the breast in females, there is no part of the healthy body in either sex which owes less of its shape to bone, and more to fat and muscle, than the buttock (Figs. 20, 21, 41, 42, 106, 107, 108, and Plates).

The great size of the region is peculiar to the human species. The maintenance of the erect position in bipeds is rendered possible by the development of the great gluteal muscles, but the thick layer of subcutaneous fat prevents their contours from being seen as well as they would be otherwise.

Without the powerful development of these muscles the erect position could never have been attained by man, yet once actually adopted, the maintenance of the attitude is facilitated by the ligaments on the front of the hip-joint, and economy of strength is observed by this relegation of constant duty to inextensible ligaments.

If these muscles were dissected away from the underlying bones, a deep and broad groove would be found between the great trochanter of the femur and the prominent portion of bone known as the tuberosity of the ischium, upon which we sit and from which the hamstring muscles arise. Now, this groove in the living body is not only completely filled up by muscles and fat, but it is overfilled, so that its position is marked by a massive prominence which prevents the bones from forming obvious landmarks in this region.

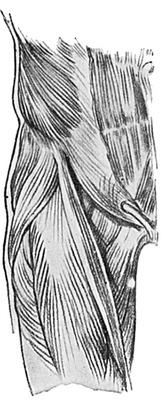

Fig. 41.—Gluteal Muscles and Ilio-tibial Band. Outer side of upper part of thigh.

The skin is thick and coarse, and the fat, even in ordinary individuals, is nearly an inch thick.

The boundaries of the buttocks are as follows:—

The upper limit is formed by the crest of the ilium, from which several large muscles arise—some passing upwards to the abdominal wall, some downwards to the thigh. The prominences formed by these muscles when well developed are separated by a groove, which does not accurately correspond, though it does roughly, to the iliac crest (vide Chap. VII.).

Internally the two buttocks are separated from each other above by the flattened termination of the spinal furrow, which is here supported by the upper 104 part of the sacrum, or, more precisely, by the upper three sacral vertebrae, the individual spines of each of which are easily felt, and sometimes seen. Below the sacral vertebræ the two buttocks are separated by a deep narrow cleft, continuous between the thighs with the perineum.

The lower limit of the buttock is formed by a well-marked furrow, the natal fold, sloping outwards and downwards from the median cleft, and running just below the level of the tuberosity of the ischium. The natal fold does not pass much beyond the middle line of the back of the thigh, for it then tapers rapidly away and turns slightly upwards, and leaves the outer half of the lower limit of the buttock quite ill defined. The natal fold does not correspond to, but crosses more horizontally, the very oblique lower border of the gluteus maximus (Fig. 42). Further, it becomes less and less well marked as the thigh is flexed (Plates XI., XIV., XXXVIII.). It is very important to grasp and bear in mind these two facts.

The Outer boundary of the buttock is ill defined, but corresponds to a vertical line through the great trochanter of the femur.

On each side of the sacrum the buttocks, are supported by the os innominatum, especially by the iliac part of that bone and by the tuberosity of the ischial part, which is easily palpable beneath the lower margin of the gluteus maximus.

The two tuberosities of the ischia form oval prominences upon which the body is directly supported in the act of sitting, no muscle actually intervening between the bones and the superficial fascia and skin. It follows that when the subject bends the hip beyond the right angle which is employed in sitting, the tuberosity emerges from under cover of the gluteus maximus and becomes visible, and from it the hamstring muscles can then be seen to arise (Fig. 42).

The position of the tuberosity of the ischium, although it cannot in all positions be seen, can always be felt. Not far away are two other bony landmarks of great importance, with which the student is already familiar—the anterior superior spine of the ilium, and the tip of the great trochanter of the femur. If a rule be laid upon the anterior superior spine and also upon the tip of the great trochanter, its continuation will pass through the most prominent part of the tuberosity. This line is absolutely constant in the normal individual; it is called “Nélaton’s line” and is obliquely placed, being directed from the front round the side of the buttock, backwards, downwards, and finally a little inwards.

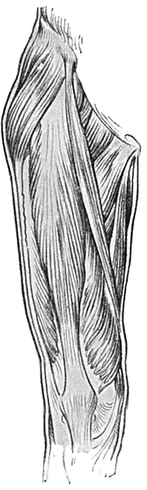

Fig. 42.—Muscles of the Back of the Right Thigh and Popliteal Space.

It is only in fat persons that the buttocks are pendulous, and in such case their most prominent part is a little below and internal to the tuberosity of the ischium.

It has already been pointed out that the fat in this neighbourhood is usually thick, and the outlines of the muscles consequently obscured; but if the body is bent forwards and then slowly raised, the gluteus maximus coming into vigorous action may generally be demonstrated.

The buttock is relatively larger in the female, because the pelvic skeleton is larger, and it is more rounded, because in this part, as in the thigh and chest, the female is apt to have a thicker covering of fat.

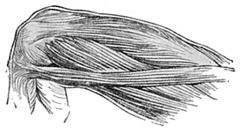

The gluteus maximus (Figs. 41 and 42, pp. 104, 106, and 20 and 21, pp. 75, 76) is one of the largest muscles in the body. It is made up of exceptionally coarse and thick muscle fibres, between the bundles of which lie quantities of fat and fibrous tissue. It forms a regular quadrate mass, which is directed obliquely from near the middle line at the base of the spine to the upper part of the femur, and that well-marked portion of the deep fascia of the thigh known as the ilio-tibial band.

The muscle has its origin from the back part of the crest of the ilium, from the sides of the sacrum and coccyx, and from the adjacent ligaments. Its upper and lower borders are parallel with each other. The upper border passes forwards and outwards, and somewhat rapidly downwards from the crest of the ilium; the lower border does not correspond accurately to, but rather cuts across, the outer part of the natal fold, and is continued onwards to the back of the upper extremity of the shaft of the femur.

The upper part of the insertion is into fascia forming the ilio-tibial band (Fig. 41, p. 104), and is not quite so prominent as the lower part, which is inserted into the femur.

In that part of the buttock which lies above the upper sloping border of the gluteus maximus and below the crest of the ilium, there is an extensive but shallow depression. This is occupied by the fibres of the gluteus medius, a fan-shaped muscle passing from the outer surface of the iliac bone to the outer part of the great trochanter of the femur.

The chief action of the gluteus medius is to draw the lower limb away from the middle line of the body; of the gluteus maximus, to extend the hip-joint, as in raising the body from the position of the quadruped to that of the biped. By its attachment to the ilio-tibial band it also steadies the knee-joint. When it is in action, the ilio-tibial band is rendered taut, and produces a flattening, or even a furrow, upon the outer side of the thigh (Fig. 44).

Fig. 43.—The Muscles in the Region of the Groin.

The Groin (Figs. 25, 27, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47) is a shallow oblique furrow which separates the abdomen above from the thigh below. It may, in fat persons, be obscured, or indeed overhung, by the fat of the abdominal wall (vide infra). This shallow furrow is continuous with the iliac furrow, which nearly corresponds to the crest of the ilium, on the side of the body. Its extent is from the anterior superior spine of the ilium to the pubic region, and its general direction is downwards and inwards. The furrow has a very slight convexity downwards and outwards, corresponding to the underlying and very important thickening of the tendon of the external oblique muscle named “poupart’s ligament.”

The anterior superior spine of the ilium (Figs. 8, 9, 43 to 47), from which the ligament passes, is a small oval prominence of bone on the side of the front of the body. The long axis of the oval is directed downwards and inwards.

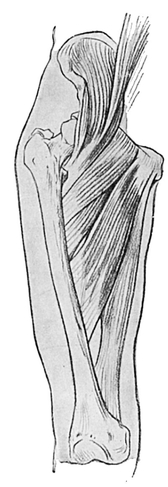

The Thigh extends from the groin and buttock to the knee and popliteal space. It tapers considerably from above downwards, especially in the female (vide )Plates, and becomes more circular as it approaches the knee. It is slightly constricted just above the knee, so that at the joint the limb slightly expands again (Fig. 44).

The outer side of the thigh is flattened; the inner side slopes from the inner end of the fold of the groin downwards and slightly outwards. Immediately below the furrow of the groin several important muscles are grouped in a region known as Scarpa’s triangle, and some of them form very obvious surface markings.

The chief ridge is due to the long tailor’s muscle, or sartorius. (Figs. 43, 44, 45). Its course is very long and somewhat sinuous, reaching from an origin at the anterior superior spine of the ilium to an insertion at the upper end of the inner surface of the tibia, just below the knee, so that it passes over and acts upon two joints—the hip and the knee.

Fig. 44.—Muscles on the Front of the Right Thigh.

At its beginning the sartorius is directed downwards and inwards across the front part of the thigh, here forming the outer boundary of a slight hollow called Scarpa’s triangle. At the junction of the upper and middle thirds of the thigh it reaches the inner side, and is directed downwards with a slight inclination backwards. It then passes down on the inner side of the knee, and finally turns forwards to reach its insertion into the tibia.

Fig. 45.—Inner Side of Thigh, showing Ridge formed by the Sartorius Muscle.

Fig. 46.—Vasti Muscles (shaded), Adductor Muscles (outline). Front of Right Thigh.

The outline of this muscle will usually be seen, even in fat persons, if the subject holds his limb so that the knee is flexed, and the hip flexed and strongly abducted, and rotated outwards (Fig. 45). This is the old-fashioned tailor’s customary position while sitting on his bench; hence the name of the muscle. It should, however, be understood that several other muscles are concerned in producing this movement.

Of the adductor muscles on the inner side of the thigh only the adductor longus needs mention here (Figs. 46 and 47). It passes from the front part of the pubic bone to the back of the middle of the femur. It starts above as a tendon and becomes much broader as it passes down. It lies in a doubly oblique plane—i.e. not only does it slope from above downwards and outwards, but also from before backwards, so that its inner and lower margin is much more prominent than its outer and upper margin. The adductor longus passes behind the sartorius and bounds Scarpa’s triangle internally.

Poupart’s ligament bounds this triangular hollow above. The apex of the triangle is formed below by the meeting of the adductor longus and the sartorius. The inner part of the hollow is deeper than the outer, where the head of the femur pushes the muscular floor of the triangle forwards.

Fig. 47.—Ilio-psoas and Adductor Muscles of Thigh.

The upper end of the large superficial internal or long Saphenous vein passes upwards in the inner half of the triangle to within an inch and a half below the inner end of Poupart’s ligament, where it dips down among the deep structures to join the main vein of the limb, the common femoral vein. It is rarely visible unless abnormally large, or the subject very thin.

The quadriceps muscle (Figs. 43 to 46, and Plates) is a great mass lying deep to the sartorius on the front and sides of the thigh. It consists of four parts: the first three, the vastus internus, vastus externus, and rectus femoris, all produce obvious surface markings; but the crureus, which forms the fourth head of the muscle, although responsible in great part for its bulk, producing the general anterior convexity of the thigh, which is well seen in Fig. 45, is completely covered up by the other three heads.

The quadriceps mass emerges from under cover of the sartorius and passes to the knee. Its three visible constituents are:—

1. The rectus femoris, (Fig. 44), forming the superficial anterior part of the mass. It pursues, as its name implies, a nearly vertical course, starting from the anterior superior spine of the ilium with a slight inclination inwards, and reaching to the upper border of the knee-cap.

2. The vastus internus (Figs. 44, 46), giving rise to a large prominent mass on the inner side of the lower half of the thigh. Good development of this muscle is one of the characteristics of great strength. In some positions of the limb its surface presents an oblique groove, some two or three inches above and internal to the knee-cap, best demonstrated perhaps when the subject stands on both legs but leans most of his weight on one. The groove will be noticed in the limb upon which the greater pressure is made, and it is directed downwards, inwards, and backwards (Plates XXVI., XXVII.).

3. The vastus externus (Figs. 44 and 46, pp. 109, 110), on the outer side of the thigh, extending from the great trochanter above to the patella below. On the general prominence formed by this muscle there is a shallow longitudinal groove or flattening produced by the ilio-tibial band (Plates XXII., XXVI., XXVIII. C), a longitudinal thickening in the deep fascial envelope of the thigh (the fascia lata), into which two muscles are inserted above, viz. the gluteus maximus and the tensor fasciæ femoris (Figs. 41, 44).

As a rule this groove is not obvious at a higher level than the middle third. Near the knee the band becomes more obvious as a ridge which terminates below in the external tuberosity of the upper end of the tibia, and lies a short way behind the tendon of the biceps muscle. The tensor fasciœ femoris muscle, so called because it is inserted into (the front of) the ilio-tibial band, which is only a very strongly developed part of the deep fascia of the thigh, forms a prominent ridge running downwards from the anterior superior spine, with a decided inclination backwards (Figs. 43, 44).

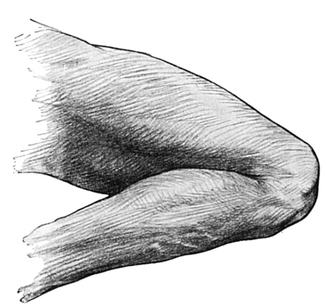

Fig. 48.—The Flexed Knee.

Into the top end of the ilio-tibial band is also inserted the gluteus maximus muscle, but from behind. The band is very frequently taut and obvious, because in most positions of the limb the muscles inserted into it have to be thrown into action in order to maintain the erect posture.

In the middle third of the thigh, and on its inner side, where the sartorius is passing nearly vertically downwards, this part of the muscle may not (as indicated in Fig. 45, p. 110) form a definite ridge, but may lie at the bottom of a groove which separates the adductor group of muscles behind from the quadriceps mass in front (Plates IX. and XXI.).

The adductor magnus muscle is chiefly responsible for the mass of the adductor group, although very little of it can be seen to produce a distinctive ridge. In its lower part the tendon of the muscle is capable of demonstration, forming a small ridge which ends just above the internal condyle of the femur in the adductor tubercle. This can always be felt, and can in some spare limbs be seen(Fig.47, p.111).

The great trochanter of the femur is easily felt in the upper part of the outer side of the thigh, covered to a certain extent, and therefore obscured, by the insertion of the great gluteal muscle. The actual position of the bone is marked by a slight hollow, yet the surrounding muscles form a pronounced general convexity in this region (vide Plates).

The back of the thigh is, as we have already seen, marked off from the buttock by the deep fold of the nates, which is the lateral and inferior continuation on each side of the deep median groove passing downwards from the coccyx and lying between the two buttocks.

Starting from the middle line, the two natal folds diverge, and each one curves at first downwards and outwards, then directly outwards, and finally even a little upwards and outwards, to terminate by gradually fading away at a point usually a little external to the middle line of the thigh (Plates XI. and XII.).

The bulk of the prominent muscularity of the back of the thigh is due to the hamstring muscles, along its whole length. They are three in number, and lie close together in the upper part of the thigh, where their superior attachments to the tuber ischii are concealed beneath the gluteus maximus, and they form when in action a single wide ridge (Fig. 42, p. 106).

The biceps, the largest, so called from its having a second head of origin from the femur.

The semi - membranosus, so called because it forms in its upper and lower parts a flat membranous band.

The semi-tendinosus, so called from its long thin tendon below, which is almost, if not quite, as long as the muscular portion.

These three muscles pass down the back of the thigh and, forming the “strings” of the “ham” or popliteal region (Figs. 42, 49, and 50), reach the bones of the leg below the back of the knee. It is of great importance to observe the manner in which they descend from their upper to their lower attachments.

Fig. 49.—Muscles of the Popliteal Space and Calf of the Leg.

Just before reaching the middle of the back of the thigh, the single ridge formed by their combined origin from the tuber ischii splits into two; the outer and larger and more prominent is the biceps, while the inner is the semi-tendinosus, lying upon the semi-membranosus.

The two heads of which the biceps is composed cannot be distinguished from each other without dissection; the ridge it forms is single.

Not so, however, the inner ridge. Although it is true that in the upper part of the thigh the semi-tendinosus cannot be distinguished from the underlying semi-membranosus, this is by no means the case in the lower part; for here a secondary ridge or crest, sharp and prominent and formed by the tendon of the semi-tendinosus, lies upon the main eminence, which is broader and is formed by the semi-membranosus (Fig. 42, p. 106).

Fig. 50.—The Guter Side of the Knee.

These two main ridges, one on each side of the middle line of the back of the thigh, diverge as they travel down the thigh, till the biceps, passing to the outer side of the popliteal space, gains its lower attachment in the head of the fibula; while the other two muscles, passing the popliteal space well to the inner side, gain their insertions on the inner surface of the upper end of the tibia with the sartorius.

These ridges differ, then, in constitution and direction, but there is yet another difference to be carefully studied. The biceps muscle is inserted into the fibula by a moderately long, rope-like tendon (Fig. 50). The ridge produced by the biceps muscle itself therefore narrows rapidly into this tendon as it travels down past the middle of the back of the thigh, and it is not obscured by any other structure This point is one of great importance.

Similarly, the semi - tendinosus muscular belly rapidly gives place to its much smaller tendon as it is traced downwards.

But the main inner ridge, formed by the semi-membranosus, narrows comparatively little. The semi-tendinosus stands out much less conspicuously than the biceps.

Upon the outer side and in front of the bicipital ridge is a well - marked groove, succeeded by the ilio-tibial band, stretching from the gluteus maximus to the knee. In front of this band, again, lies the flattened outer side of the thigh, the muscular bulk of which is chiefly contributed by the vastus externus.

Fig. 51.—Muscles on Inner Side of Lower Half of Thigh.

The Region of the Knee (Figs. 45, 48, 49, 50, 51, and 52).

It will have been observed that in the thigh the general shape of the limb is chiefly due to the large and important muscles. But very different causes influence the shape of the knee, for the chief prominences are formed not by muscles, but by the underlying bones. These are the patella, the lower end of the femur, and the upper portions of the tibia and fibula.

When the knee is viewed from the front it will be observed that the inner side is much more prominent than the outer, and shows, especially in women,- a marked convexity, while the outer side is generally flat, but may even present a slight concavity (Fig. 52).

The upper and lower limits of this concavity, or flattening, lie wider apart than the limits of the internal convexity. In other words, the external concavity occupies a considerable length of the limb, while the internal convexity is short and sharp. It is produced by the internal condyle of the femur and the internal tuberosity of the tibia. The eye will not tell you where the femur ends and the tibia begins unless the knee is flexed. In a sitting position when one knee is crossed over the other, the internal tuberosity of the tibia is seen to be slightly more prominent than the internal condyle of the femur. In muscular subjects the prominence of the vastus internus very much obscures the bold outline of the internal condyle (Fig. 51), but the internal tuberosity of the tibia is not similarly obscured by superjacent muscles. In thin persons, of course, the bony prominences are much more obvious, and in them the internal condyle may be observed to begin abruptly, about the point at which the adductor tubercle, for the insertion of the tendon of the adductor magnus, is found on the inner side of the knee, half-way between the anterior and posterior surfaces.

In fact, it is the absence of great muscle-masses which allows the bony prominences about the knee to be so clearly recognised.

Although the external condyle of the femur may easily be felt upon the outer side of the limb, it is not usually seen as a marked prominence; nor is the external tuberosity of the tibia, and chiefly because of the biceps tendon and the ilio-tibial band (Fig. 50).

The most prominent bony point upon the outer side of the knee is that produced by the head of the fibula. Like many other prominences this one lies. in well-covered persons, at the bottom of a slight depression. But if the knee is bent it forms almost always a definite prominence below the external tuberosity of the tibia and indeed well below it, so that the fibula is excluded from the knee-joint (Fig. 50).

The tendon of the biceps accounts for the well-marked ridge when the forcibly flexed knee is examined from the outer side, and will guide the finger down to the head of the fibula. In front of the bicipital ridge, notice the longitudinal groove, and in front of that again, the longitudinal prominence formed by the ilio-tibial band.

On the front of the knee, the patella or knee-cap is most obvious when the knee is extended or semi-flexed. It is the oval eminence which lies opposite the upper two-fourths of the convexity of the inner surface of the knee and the middle two-sixths of the concavity of the outer surface (Fig. 52).

Fig. 52.—Muscles on the Front of the Right Knee.

The patella is much less noticeable when the joint is completely flexed. This is due to the fact that as the knee is bent the patella shifts from its position on the front of the femur to the inferior surface of that bone, here to lie in a groove and so to bury itself not , only between the condyles of the femur, but also in the triangular space between the lower end of the femur and the upper end of the tibia (Fig. 48, p. 113).

The upper and lower edges of the patella are not so obvious as its lateral margins. The quadriceps muscle of the thigh is attached to the upper border and the ligamentum patellœ is fixed to the lower border, which is more pointed than the upper. The patella thus forms a connecting link between the quadriceps muscle and the ligamentum patellae. The-latter produces a well-marked ridge, and narrows as it descends to terminate in the tubercle of the tibia, upon which bone it acts as the tendon of insertion of the quadriceps muscle. The patella is the largest of the sesamoids, or little bones specially formed in tendons at the places where they glide over bony prominences. The ligamentum patellae stands out conspicuously as the knee is extended, i.e. straightened out (Fig. 52).

The tubercle of the tibia, the ligamentum patellœ, and the pointed lower part of the patella receive the body weight when the kneeling posture is assumed, and the skin over them is very coarse. The front of the knee is marked by numerous transverse furrows, analogous to the wrinkles of the face, and to the lines of flexion upon the fingers and upon the palm of the hand.

When the leg is forcibly straightened, the loose fat which lies between the ligamentum patellae and the tibia is squeezed and forms a slight bulging on each side of the ligament.

The vastus internus forms a much more obvious muscle-mass, just above the patella level, than does the vastus externus, and presents in the muscular a curious groove directed downwards, inwards, and backwards (vide p. 122). The maintenance of the erect posture depends both at hip and knee rather upon ligaments than on muscles, so that the Quadriceps is often off duty, and then the patella falls somewhat forward.

The ham, or popliteal space (Figs. 42 and 49, pp 106, 115), is the hollow behind the knee. But it must be remembered that it is a hollow only when the knee is bent, for when the limb is straightened out a prominence takes the place of the hollow. This is chiefly caused by the shape of the lower end of the femur and of the upper end of the tibia, both of which, but especially the former, are prominent, and press backwards the soft fat and other contents of the popliteal space, such as the main artery and vein and nerves of the lower limb.

The hollow of the ham proves on dissection to be diamond-shaped, with its vertical axis at least three times the length of the horizontal. The apices of the diamond may as a rule be easily seen without dissection, but the more obvious one is the upper.

The upper sides of the diamond are longer than the lower; thus there is more length in the part lying above the horizontal line joining the lateral angles of the diamond than there is in the part lying below.

It will be remembered that the hamstring muscles, as they pass down the thigh, form two ridges which diverge from each other. At the angle of divergence is the upper apex of the popliteal space. This is situated at the junction of the middle with the lower third of the back of the thigh. It will be quite plain that the biceps forms the upper and outer boundary, and the semi-membranosus and semi-tendinosus the upper and inner boundary of the diamond.

The lower sides of the diamond are formed by the two heads of the gastrocnemius muscle, and are much less prominent than the upper sides; in fact, they lack definition until dissected. The upper parts of the gastrocnemii are overlapped by the muscles which form the upper boundaries of the popliteal space.

There is yet another muscular ridge to be noticed in connection with the inner side of the knee. This is obliquely placed and directed from behind the prominence which is formed by the internal condyle of the femur, downwards and forwards, to terminate on the inner surface of the tibia, at or about the level of its tubercle (Fig. 42; Plate XXVI.).

The ridge is due to the tendons of the gracilis, sartorius, and semi-tendinosus muscles, all three of which have a common insertion, though they arise from the os innominatum at very different points nearly equidistant from each other. The gracilis arises from near the symphysis pubis, the sartorius from the anterior superior spine, and the semi-tendinosus, from the tuber ischii.

The external concavity and the internal convexity mentioned above in connection with the sides of the knee will repay close and careful examination, as they differ considerably in young children and adults of both sexes (vide Plates). The difference between the male and female is nowhere more pronounced in the limbs than in the region of the knee. The inward convexity is much more marked in the female than in the male, and in the child than in the adult, and is due in both sexes, first, to the inclination inwards of the femur as it extends downwards from the hip to the knee, and secondly, to the large size of the internal condyle.

Owing to the larger relative, and, frequently, absolute, distance between the acetabula of the pelvis, which is an exact indication of its breadth, the femoral inward slant is more pronounced in the female than in the male.

The line of the knee-joint itself is transverse; the legs lie parallel to each other, but the thighs incline towards one another, and so some slight degree of that condition which, when exaggerated, is called “knock-knee” is apparent even in the normal subject.

By the Leg (Figs. 48, 49, 50, 53, and Plates) is meant anatomically only that part of the subject which extends from the knee to the ankle. It is thicker and more circular in the upper part or calf, owing to the relatively large size of those muscles, which are usually well developed because in constant use. Legs vary more in extent of muscular development than appears to correspond with their variation in strength. Very extensive muscular development, such as appears to be aimed at by some exponents of so-called “physical culture,” is no more necessary or desirable from the point of view of health, strength, or efficiency than from the point of view of beauty.

The leg is smaller in its lower half, and oval in cross section. The decreased calibre is due to the replacement of the muscles by their tendons, and the level at which this takes place varies in different types or nationalities; the negro has a high calf, just as the Scandinavian has a high cheek-bone.

Fig. 53.—The Inner Side of the Right Leg.

Immediately below the knee the leg is not so thick as it is a little lower down, and again after rapidly and gracefully tapering below the calf it increases a little in thickness when the actual ankle-joint is reached (Fig. 53).

The Bony Landmarks of the Leg.—The shin is formed by the inner surface of the tibia (Fig. 53), which is directed forwards as well as inwards, and by the sharp anterior border of the same bone. The anterior border of the tibia is named the crest; it pursues a sinuous course down the front of the leg, and is easily felt all the way from the tubercle of the tibia to the ankle-joint.

The crest is, in its upper two-thirds, slightly concave forwards, and in its lower third slightly convex.

The inner surface of the tibia, which extends subcutaneously along the whole length of the bone, tapers somewhat as it is traced downwards, but becomes expanded again in the region of the ankle-joint.

The crest and inner surface, which together form the shin, are for the most part immediately subcutaneous. In the upper part of the leg, however, the thin spreading tendons of the sartorius, gracilis, and semi-tendinosus muscles cover the inner surface as they come forwards below and inside the knee (Figs. 44, 51); and in the lower part of the leg, the crest of the tibia is obscured by the passage of the dorsal extensor tendons from the leg to the foot.

As an analysis of these tendons can readily be made without dissection, their relative positions will be described in more detail later (p. 127).

The bony prominences of the tibia and fibula in the region of the knee have already been noticed (p. 117); and with the exception of the shin, nothing more can be felt or seen of the bones till the region of the ankle is approached. Here the expanded lower portions of the tibia and fibula become again subcutaneous, and form two well-marked prominences, the malleoli, situated one on each side of the ankle.

The Internal malleolus of the tibia (Fig. 56), is more massive, but shorter and less prominent, than the external malleolus of the fibula (Fig. 57). The relative positions of these pointed lower extremities of the leg bones are as follows:—

The tip of the external malleolus is situated a full half-inch below and half an inch behind the corresponding point of the tibia. The external surface of the fibula is immediately subcutaneous for nearly three inches above the tip of its malleolus, but above this it is buried by the adjacent tendons and muscles.

The internal malleolus can be traced up into the subcutaneous shin.

Although the inner border of the tibia may be identified by the sense of touch, it is obscured from view by the bulging of the subjacent calf muscles on the back of the leg (Fig. 53).

In addition to the bony, muscular, and tendinous prominences, a careful inspection of the leg, which has habitually less fat than the thigh, will reveal three superficial structures, viz. the internal saphenous vein, the external or posterior saphenous vein, and the musculo-cutaneous nerve. They are all difficult to see except in thin subjects—and especially difficult is the nerve.

The internal, or long Saphenous, vein has already been described in the thigh (p. 111). In the leg it forms a blue line or ridge, just in front of the internal malleolus, and passes up the limb, just behind the shin, to the inner side of the knee, near the posterior aspect of which it lies. This vein receives several tributaries from the front and sides of the leg, and is liable to be dilated at intervals, or to pursue a very tortuous course in those who are the subject of varicose veins.

The short, or posterior saphenous, vein passes behind the external malleolus and reaches the back of the leg, where it occupies the middle line. Its course is straight to the back of the knee, and as it passes in this upward direction it lies between the two bellies of the gastrocnemius muscle.

If the foot is strongly bent downwards and inwards, the musculo-cutaneous nerve may occasionally be demonstrable as a faint, obliquely longitudinal ridge in the lower half of the front and outer side of the leg.

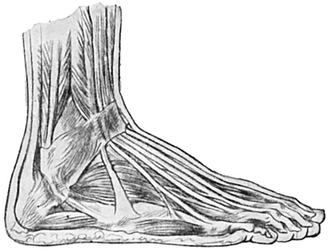

The prominences made by muscles in the leg are numerous, and fall into three groups. The first group comprises four muscles, three of which can usually be identified, and lies between the tibia and fibula on the front of the leg. The tendons of these muscles may be traced in favourable circumstances for their entire course as they pass to the upper surface of the foot.

The second group, which is made up of two muscles, lies on the outer side of the fibula, and its tendons also pass to the foot, but behind and below the external malleolus. This group is the smallest of the three.

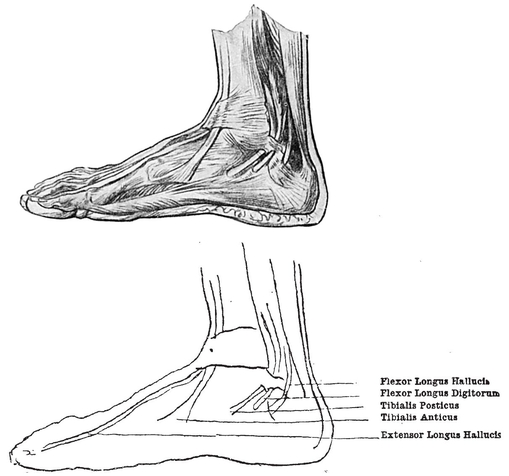

The third group, which lies on the posterior aspect of the leg, may be further subdivided into the superficial massive muscles, which are inserted by the tendo Achillis into the heel, and the deep muscles and tendons which pass onward behind the inner malleolus to reach the sole of the foot, where for the most part they cannot be detected without dissection.

The first or anterior group of leg Muscles are the extensors of the foot and toes. They comprise, from within outwards, the tibialis anticus, the largest; the extensor longus hallucis ; the extensor longus digitorum, the longest; and the peroneus tertius, the smallest, which may be regarded as part of the extensor longus.

The tibialis anticus (Figs. 50, 53) forms a prominent muscular mass on the outer side of the crest of the tibia, in the*upper two-thirds of the leg, best seen when the toes are forcibly raised. The inner border of the muscle is separated, except in fat persons, by a groove from the crest of the tibia, and its outer border by another groove from the adjacent extensor longus digitorum. The tibialis anticus is often sufficiently bulky to endow the front of the leg with a longitudinal convexity, so that its contour viewed from the side is curved distinctly forwards when the muscle is in action (Fig. 48 and Plate XXI.).

This curve, due to a muscular prominence, must be carefully distinguished from any forward bowing of the tibia, which may be present, but only as a deformity. It has already been pointed out that the upper half of the normal tibial crest is slightly concave forwards.

In the lower third of the front of the leg, the muscular belly of the tibialis anticus gives place to a strong tendon, which may be rendered so prominent by forcible action of the muscle (as in raising and inverting the foot) that the ridge which it produces may be seen through the boot (Fig. 59).

As the tendon passes downwards to the foot, this ridge is found to be directed slightly inwards, and to pass over the lower end of the shin and part of the ankle-joint, slightly internal to the mid-point between the two malleoli. When the body is raised on tiptoe, both muscle and tendon stand out well.

The extensor longus digitorum (Figs. 50, 53) lies upon the outer side of the tibialis anticus in the upper third of the leg, in close relation to the fibula. The two muscles are separated by a groove which ends above in the head of the tibia, and not in the interval between the fibula and tibia. As this groove is traced downwards, it is interrupted or filled by the tendon of the extensor longus hallucis, coming to the surface and appearing to the outer side of the tibialis anticus (Fig. 53).

The ridge formed by the extensor longus digitorum muscle broadens out just above the ankle-joint previous to dividing into four tendons. This ridge is external to the mid-point between the two malleoli.

The peroneus tertius (Fig. 53, p.123) is a small muscle which forms a slight elevation on the front of the leg in its lower third; but as its muscle is continuous with the ridge formed by the extensor longus digitorum, it has no defined limit above.

The muscle, in passing towards the foot, diverges a little from the extensor longus digitorum, and its tendon passes to the outer part of the dorsum of the foot (Fig. 54).

The second or external group of leg muscles comprises the two peronei:—longus and brevis—as they run down the outer surface of the fibula.

The peroneics longus (Figs. 49, 50) lies behind the brevis and obscures its outline. Both peronei become tendinous in the lower third of the leg, and pass behind and below the external malleolus to the sole of the foot. The two tendons may usually be demonstrated, and they preserve the same relative position as the muscular bellies (Fig. 54).

The third or posterior group of leg muscles is the largest and the most characteristic of the three groups. Its great size is due chiefly to the two superficial members of the group, though there are four other deeper and much smaller members. The gastrocnemius and soleus are very large, and lie upon the other muscles, the gastrocnemius being most superficial of all. This is the group that forms the calf of the leg.

The gastrocnemius (Figs. 48, 49, 53) has two prominent heads, an inner and an outer, both extending about half-way down the leg and separated by a deep vertical groove; the inner head is longer and broadei than the outer.

The most prominent part of the calf of the leg lies at about the junction of the upper and middle thirds. The explanation of this is, that while the gastrocnemius arises from the lower end of the femur between the upper and diverging boundaries of the ham, the soleus (Figs. 49, 50, 53), at least in its main part, arises from the tibia and fibula considerably below the knee-joint. And although the gastrocnemius is responsible, so to speak, for the superficial expression of the calf of the leg, it is the soleus which chiefly influences its size and its general shape.

The gastrocnemius, in the lower half of the leg, tapers rapidly as it is traced downwards, and a very prominent longitudinal ridge is formed, which passes to the back of the os calcis or heel. The ridge is due to the presence of the thickest and strongest tendon in the body, the Tendo Achillis (Fig. 49, p. 115), which is the name applied to the conjoined tendons of insertion of the soleus and the gastrocnemii. It is about one inch broad at its lowest part, convex from side to side, and slightly concave from above downwards. The skin covering it is scored by transverse furrows, caused by the movement of the ankle-joint; few and deep and striking in the infant (Fig. 58), more numerous and more superficial in the adult.

The edges of the soleus become prominent on each side of the gastrocnemius, and are seen to melt away completely into the tendo Achillis about three or four inches above the heel (Fig. 49).

The lateral parts of the calf, which, as has been pointed out, are formed by the soleus muscle, may easily be distinguished (even in the front view of a muscular leg), as they bulge outwards beyond the inner border of the tibia on the inner side of the leg, and the peroneus longus muscle on the outer side (Plate XXVI.). The four deep muscles of the calf are completely covered by the gastrocnemius, the soleus, and their tendo Achillis, and cannot be seen without dissection.

On each side of the tendo Achillis there is a marked hollow. These hollows are continuous with depressions lying behind and below each malleolus, and gradually disappear as they are traced upwards.

The functions of these two large muscles, viz. the gastrocnemius and the soleus, are of great interest. By raising the back part of the os calcis, which lies behind the axis of the ankle-joint, they forcibly depress the foot, and are thus, as will be seen later, of great use in the act of walking (Fig. 60). Further than this, the gastrocnemius assists in maintaining the erect attitude by means of its action upon the knee-joint, and so is in constant use. This explains why the muscle is so membranous compared with the soleus, as, for constant use, membrane, which is a lowly organised but elastic tissue, is much more economical than muscle, which is very highly organised.

It is important to notice that the tendo Achillis does not extend as far as the lowest level of the back part of the os calcis, but only to its middle (Fig. 49). The lowest level of the backwardly projecting os calcis forms the actual heel, and is obscured by a very thick pad of fat, upon which the weight of the body is received when the heel is brought to the ground in the act of walking or jumping.

When the leg is viewed from the side, the calf of course presents a marked convexity occupying the upper two-thirds of the leg in white races—decidedly less in negroes.

Fig. 54.—Extensor and Peroneal Muscles and Tendons of Foot. Outer surface and Dorsum.

The Ankle is the joint at which the foot is set on to the leg at about a right angle. The malleolar prominence on each side, the several tendons on the front of it, and the one large tendo Achillis at the back, with hollows on each side of it, have already been described with the lower part of the leg.

There is a marked, and not easily explicable, difference in individuals in the girth of the limb at, and just above, the ankle.

The Foot (Fig. 55), although constructed in much the same way as the hand from the scientific anatomist’s point of view, differs from it in many respects, all of which are of great importance to the student of art.

Fig 55.—The Dorsum of the Foot.

Thus the angle which the main axis of the foot makes with the leg is rather more than a right angle. Further the foot is usually turned outwards at an angle of about ten degrees from the strictly antero-posterior line. This angle of torsion of the foot upon the axis of the leg varies, however, very much. It may amount to nothing at all, or it may be very much greater than usual.

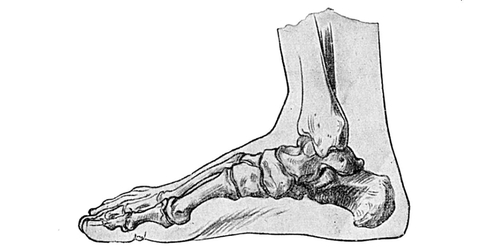

Fig. 56.—Bones of Right Foot. Inner side.

Formerly drill instructors commonly taught that the outward pointing of the toes was essential to powerful walking and running; further observation has, however, demonstrated that the athlete in making a big effort is prone to invert rather than evert his toes (Plate XXVII. C, XXVIII. B).

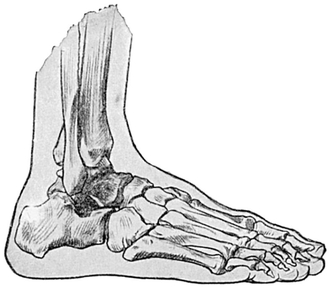

Fig. 57.—Bones of Right Foot. Outer side.

The foot is broader and flatter in front than behind, where it is thicker and more cylindrical. The comparatively great breadth in the neighbourhood of the toes is the characteristic feature of a natural and beautiful foot, and it is a thousand pities that this fact is not recognised by the genius which directs the fashions emanating from the boot factories.

The great breadth of the foot is especially well seen in infants, partly because there is less arching of the foot than in an older subject (Fig. 58).

In the natural state the foot is broadest at the root of the toes, or perhaps a little behind this level. The breadth is a little less at the points of the toes, unless the body is raised on tiptoe, when the broadest part is at the level of the toes (Plate XXVII. C). As indicated before, the foot becomes narrower as it is traced backwards.

Fig. 58.—To show the attitude and proportions of an infant who is learning to walk.

Various bony prominences mark the surfaces and borders of the foot. A description of these must presuppose a knowledge of the relative positions of the internal and external malleoli, which have already been described.

On the inner surface (Figs. 56, 58, 59) of the foot the following bony points may be recognised:—

The tubercle of the scaphoid or navicular bone produces a prominence one inch below the tip of the internal malleolus and one inch and a half in front of it. Though actually situated chiefly upon the under surface of the bone, this tubercle cannot be felt so well upon the sole of the foot, owing to the thickness of the structures there lying superficial to it.

If the upper and lower levels of the inner surface of the foot be observed, the tubercle of the scaphoid will be found to lie half-way between them. One inch and a half in front of the tubercle of the scaphoid, and about a finger’s breadth below it, is the projection formed by the base of the first metatarsal bone, much more easily felt than seen (Fig. 56).

Fig. 59.—Tendons on Inner Side of Ankle and Foot.

Three fingers’ breadth in front of this is a better marked prominence, made by the head of the same bone. Inclined almost directly forwards from it, but also slightly outward, i.e. towards the middle line of the foot, the inner border of the great toe shows a projection a little beyond its centre, due to the base of the terminal phalanx.

Upon the outer border (Figs. 54, 55, 57, 58, 60) of the foot the chief prominence is made by the tuberosity of the fifth metatarsal bone, some two inches below and two inches in front of the external malleolus.

Fig. 60.—The Dorsum of the Foot.

From the tuberosity of the fifth metatarsal bone the outer border is continued forwards, with a very slight inclination outwards. It is interrupted at the level of the root of the little toe by a small prominence, caused by the presence of the head of the same metatarsal bone.

On the upper surface of the foot, when in an easy position, no prominences are noticeable, except the knuckles of the toes, and occasionally that portion of the astragalus which lies immediately below and a little in front of the ankle-joint.

The heads of all the metatarsal bones, but especially that of the first, may be observed forming a ridge near the roots of the toes. This ridge is directed obliquely from within outwards and slightly backwards. Near the toes it may Occasionally be found broken up into five separate prominences, formed by the individual heads of the metatarsal bones, with slight intervening grooves.

Many important points may be demonstrated by the study of an imprint of the sole of the foot. This may be done in sand, as Crusoe discovered, or by taking two pieces of brown paper, one wet and the other dry, and stepping from one to the other so that as much of the wetted sole as possible shall press upon the dry paper.

The imprint is broadest at the line of the metatarsal heads, and quite narrow at the heel; but between these two it is even narrower and confined to the outer side of the foot, because the middle part of the inner side of the sole does not touch the ground at all. This is of great importance, for it indicates that the foot is arched from before backwards.

The arch of the foot is by no means a simple one. We have just demonstrated that it is much more pronounced on the inner than the outer side of the foot. Moreover, dissection reveals the fact that in addition to the longitudinal arch there is a transverse one. Strictly speaking, therefore, it would be more correct to call the “arch” of the foot its “dome.”

A complete examination and understanding of these arches can only be gained by dissection; but it is obvious that their integrity is of great value in the artistic “set” of the foot. If they give way, the result is a very unsightly deformity, with flatness and spreading out and eversion of the whole foot.

The posterior pier of the arch is formed by the os calcis, and the anterior piers by all the bones of the tarsus and metatarsus, except the astragalus. The astragalus forms the keystone. This antero-posterior arch projects the dorsum upwards as the convex “instep,” while to the corresponding concavity in the sole the name of “waist ” is given (Fig. 56).

The pier or pillar in front of the keystone is much longer than the pier at the back, and, moreover, it is made up of several constituents, whereas the posterior pillar has only one, viz. the os calcis. This anatomical fact explains why a person prefers when jumping from a height to land upon the fore or mobile part of the foot, rather than upon the heel or single and rigid part, as the resulting jar to the body is much less.

Again, though the anterior pillar is made up of many bones, it may be resolved into two halves, outer and inner. The inner half was shown by the wet and dry brown-paper test to be the more pronouncedly arched. There is more spring and elasticity about this inner half of the antero-posterior arch.

The surface form of the foot must be studied in greater detail. The student must all the time be careful to bear in mind the various bony landmarks already described; otherwise he will get into difficulties.

The surfaces of the foot may be taken as four in number, viz. the upper, lower, inner, and outer, though the last is so narrow as to be little more than a border. The surfaces are not distinctly demarcated from each other except at this outer border.

The upper surface of the foot will be described first, as it is in many ways the most characteristic portion (Figs. 54, 55, and 60). It is set somewhat obliquely, so that it runs from the ankle downwards, forwards, and outwards. This surface presents the convexity already alluded to as the “instep,” which, be it remarked, is more pronounced in women than in men.

There are slight depressions below and above the actual instep, very shallow, and continuous with each other on the outer side of the dorsum of the foot, where the instep is not present.

Then there are blue lines, or faint ridges, due to subcutaneous veins, to be noticed. A very easy and excellent way to make these veins more apparent than usual is to put the foot in hot water, rubbing meanwhile the leg with the palm of the hand in a downward direction.

It will be found in many cases that there is little regularity in the arrangement of these veins at or near the toes, yet as they are traced backwards towards the ankle they form an irregular arch, convex forwards, whose two extremities give origin to the two saphenous veins. One of these, usually the larger of the two, passes upwards on the leg in front of the internal malleolus, and will be readily recognised as the beginning of the long or internal saphenous, which has already been described, in the regions of the leg, knee, and thigh. The external saphenous vein is usually smaller, and passes upwards on to the leg behind the external malleolus.

Beneath these veins other structures may be seen, but before any further consideration is given to the foot, the toes must be briefly described.

The toes, or digits of the foot, are shorter and less slender than those of the hand. They are numbered one to five from within outwards, whereas the digits of the hand are numbered from without inwards. In the process of evolution the foot has undergone rotation inwards and the hand rotation outwards.

The great toe corresponds closely to the thumb. It has much less range of movement, however, partly because its evolution has been impeded by the wearing of boots, but chiefly because in man the foot is associated with standing and progression rather than with prehension.

This toe is usually the longest of all from. base to tip, although, like the thumb, it has only two phalanges; but the second toe tip may project further. It is always much more slender than the first.

The second toe is frequently bent and crowded on to or under the great toe, in those who have been accustomed to wear tight and pointed boots.

The third, fourth, and fifth toes are progressively smaller in every dimension.

The toes, numbering from one to five, spring from the front of the foot at progressively diminishing distances from the ankle. In other words, the foot is shorter on the outer than the inner side, and the line of the base of the clefts between the toes is curved backwards as it proceeds outwards.

Each of the four outer toes possesses three bones or phalanges, except that it is not rare to find the terminal and middle phalanges of the little toe conjoined —an indication probably of its commencing involution. The knuckles are very similar in number and constitution to those of the hand, though they are not nearly so prominent.

The first row lies at the root of the toes, and can only be well made out by forcibly flexing the toes.

The line made by joining the second row is curved from within outwards and backwards, and runs parallel with the line of the clefts; and if this line be continued inwards, it will pass through the second knuckle of the great toe.

The line of the third row of knuckles, confined, of course, to the four outer toes, passes similarly from within outwards, and decidedly more backwards than the line of the second row. A continuation of this line inwards would pass across the base of the nail of the great toe.

There are transverse lines on the under surfaces of the toes that correspond with the knuckles.

The club-like ends of the four inner toes are larger than the bases; the fifth toe usually tapers to a pointed extremity.

The nail of the great toe is four times as large as the next, and the succeeding nails progressively diminish in size.

Returning now to the foot, the tendons of the muscles which have already been described as forming the anterior group in the leg are as a rule very plainly seen, as they run forward in the dorsum of the foot, and are easily demonstrated and studied by making the toes strain to assume different positions. The degree of voluntary control over the movements of the individual toes varies considerably in different people.

There is a small but conspicuous soft mass on the outer part of the dorsum, just in front of the external malleolus and outside the tendons of the extensor longus digitorum (Figs. 54, 60). It is bluish, and has been likened in size and shape to an oyster. It is due to a small muscle known as the extensor brevis digitorum, but it has often been mistaken, even by those who should know better, for a bruise. Four tendons proceed from the front of this small muscle and pass to the four inner toes. The innermost tendon may be seen passing to the great toe. When a person is standing upon tiptoe the other tendons may with some difficulty be seen lying a little to the inner side of the ridges formed by the large tendons and passing to the upper surface of the toes.

The extensor brevis is the only muscle on the dorsum of the foot; all the other and larger tendons come down from the muscles of the leg.

It will be remembered that the muscles of the leg are divided into three main groups. The anterior group passes in front of the ankle-joint, and its tendons are found on the upper surface or dorsum of the foot; the external group passes behind the external malleolus; the posterior group passes chiefly into the os calcis as the tendo Achillis, but also the deeper tendons behind the internal malleolus, to be lost to view in the sole of the foot, where their precise arrangement is unimportant to the art student.

Fig. 61.—The Dorsum of the Foot.

The various groups are enclosed on their way to the foot in sheaths or tubes of soft tissue, containing an oily fluid, and are kept in place by bands of fascia, specially developed to tie the tendons down tightly at the ankle and to form tunnels for them to run through. The most important of these so-called annular ligaments (Figs. 53, 54, 59) is situated on the front of the ankle-joint. This pulley arrangement ties the tendons tight to the bones, and so at once obscures them from view and enables them to alter their direction, while the oiled sheaths reduce to a minimum the friction of their play in the tunnels.

Of the anterior group, the thickest tendon, and one which produces a very prominent ridge, is the tibialis anticus. This can easily be traced by eye and finger as it passes inwards to the base of the metatarsal bone of the great toe, and terminates at a point midway between the tip of the internal malleolus and the head of the first metatarsal bone (Fig. 54).

On its outer side the tendon of the extensor longus hallucis passes slightly inwards to the terminal small bone of the great toe, producing a distinct ridge in the concavity already described between the summit of the instep and the great toe. On the outer side of this tendon a faint ridge, widening out and eventually dividing into four, may be detected passing to the four outer toes. This is the extensor longus digitorum. The tendon of the peroneus tertius may be detected, in favourable cases only, passing to the region of the tuberosity of the fifth metatarsal bone.

The outer surface of the foot shows the tendons of the muscles of the outer group which lie behind and below the tip of the external malleolus. If the foot be depressed and turned inwards, they will be found to be two in number and to diverge gradually from each other, that of the peroneus brevis passing forwards to the tuberosity of the fifth metatarsal, and lying above the tendon of the peroneus longus, which inclines more downwards to disappear in the sole of the foot.

The oyster-like extensor brevis digitorum muscle is visible on this aspect of the foot. Below its prominence and that of the external malleolus there is a longitudinal valley, and below this again the outer edge of the sole touches the ground throughout its entire length, and presents the prominence of the styloid process of the fifth metatarsal about half-way.

The inner surface of the foot is wide at the back part, but gradually tapers to a border in front. It contains in its concavity the tendons of the posterior deep group of muscles which come from the leg. They are too deeply placed to be identified by the eye, though they may be felt just below the tip of the internal malleolus (Fig. 59).

Below and behind the internal malleolus is a deep fossa; another fossa below and in front is limited in front again by the tendon of the tibialis anticus. The inner edge of the sole, which bounds this surface of the foot below, is arched all the way from the heel to the head of the first metatarsal bone, and at the highest point of this arch the tubercle of the navicular can be distinctly felt and even seen. In front of the large rounded head of the metatarsal bone the first phalanx of the great toe presents somewhat of a waist, which hardly touches the ground, until the terminal phalanx buried in a massive pulp or “ball,” and covered again by denser skin, is reached.

The sole is provided, for the purpose of resisting pressure, with a skin so thick, and a superficial and deep fascia so dense that few landmarks can be seen or felt; it will be observed that the skin of those parts which have had to adapt themselves to the habitual reception of the weight of the body—or, in other words, of those parts which our imprint experiment showed to touch the ground—is the thickest of all. Thus, the balls of the toes, the bases of the toes, and the heel, with the outer part of the sole, are covered with very thick skin, whereas comparatively thin skin covers the waist of the foot on the inner side.

The heel and the bases of the toes receive the chief impact in walking, and form marked prominences.

One longitudinal furrow may be observed in the skin of the sole. This is a broad one lying in the middle line.

The lines of flexion in the toes are arranged as in the fingers, but are less obvious, owing to the fact that the toes are not used for grasping as are the fingers.