Figure 9.1 Constraining the penultimate step in hurdles to encourage finding ‘fixed principles’ in the movement regarding efficiency over the hurdles.

9 A constraints-led approach to coaching track and field

Introduction

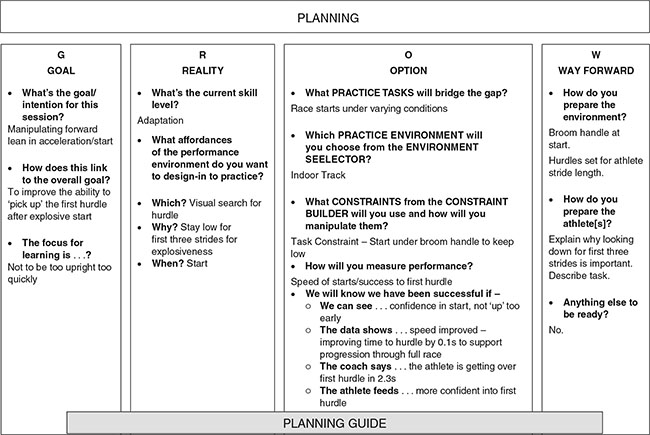

The aim in this chapter is to demonstrate how the constraints-led approach (CLA) can be applied in the context of performance level track and field (T&F) athletics using specific examples from hurdles. Here, we draw on the experiences of Matt Wood, who is the Director of Coaching and lecturer in Sport Performance for Athletics at Cardiff Metropolitan University. Matt is also currently undertaking a professional doctorate examining non-linear pedagogy, utilising constraints-led methodologies in a track and field talent development environment. It is important to note that the case study and examples presented are an amalgam of various coaches and athletes and are not a representation of any one person. First, we consider some of the complexities of coaching T&F and, in contrast to the misconception that the CLA is purely a game centred approach (Harvey et al., 2018), show how the CLA can be applied just as effectively in individual sports. While much traction has been gained in the deployment of CLA in team sports due to the obvious issues of co-adaptation, chaos, complexity and self–organisation; the use of the CLA in individual sports is often questioned for legitimacy and this can result in coaches being more comfortable with the ‘drill’-based approach to learning motor control and movement patterns in reputedly more ‘closed’ skill as they are supposedly ‘repeatable’ (but see Chapters 2, 3, 5 and 7, where we discuss the ideas of repetition without repetition that refute this idea). We offer a reflection on some key principles when coaching a sport like T&F using a CLA and refer to the GROW model as in previous chapters. In the next section we discuss some of the underpinning principles of a CLA approach in T&F, before describing a case study of an athlete, Natalie, outlining a CLA to coaching sprint hurdle starts.

Avoid thinking ‘technical sports’ can only be drill-based

Given its highly technical nature, the most prevalent approach to coaching hurdles has been to break the task down to optimise each sub-component using the design of coaching drills to elicit athlete development. For example, some coaches will prescribe take-off and landing distances for their hurdler, although individual differences in factors such as flexibility, agility, sprint capability and body size of each hurdler means there is no one-size-fits-all technical model for hurdling. In contrast to the prescriptive approach to coaching of technique, a CLA would promote a task simplification approach, and instead of directing athletes’ attention on internal movement co-ordination, the focus would be on adaptation to the performance environment. This means that learning needs to occur with performance in mind (i.e. keeping the ‘real’ race in mind) and afford the learner the opportunity to develop a wide range of capacities required to succeed in a performance environment. For example, a key component in mastering hurdle technique is to bring the hurdle stride as close to the sprint stride as possible, allowing the athlete to ‘run over’ the hurdles without breaking stride to ‘jump’. This can be very challenging for a novice or young hurdler, with the height and distance apart of each hurdle resulting in a focus of jumping over the hurdle rather than running over it. A coach who adopts a CLA would therefore match the task difficulty to individuals by simplifying the task and providing a range of reduced-height hurdles as well as different distances between the hurdles (Moy et al., 2014). A focus on learning to race by running over hurdles allows the coach to emphasise adaptation to environmental and task constraints. The contextual nature of performance is an important contributing factor to learning for athletes, and this should be considered just as prominently in individual sports as it is in team sports. For example, learning to hurdle in the rain, in windy conditions or on a wet surface, or simulating racing to qualify for a final, rather than a decontextualised focus on technique development. We provide a case study of Natalie in this chapter while also outlining other as examples of how we might utilise principles of a CLA in hurdles.

Principles of a CLA in track and field – more than just designing drills

While the ideas and concepts in ecological dynamics highlight that there is no one optimal model of executing a skill, there are a limited range of functional movement solutions due to the interaction between individual, task and environmental constraints. For example, fundamental biomechanical principles and structural constraints such as anatomy allied to the narrow task constraints associated with T&F events (e.g. the requirement to leave by the back of the circle in shot putting and discus, the specific weight and balance of the javelin or the requirement to take off behind a narrow take-off board in long and triple jumps) highlight that within each event, there are a number of signature positions or ‘anchors’ to which athletes pass through as the movement unfolds. We might refer to these positions as fixed principles. For example, in sprint hurdles, a fixed principle might include a specific body shape that the coach can recognise (i.e. it looks like hurdling) when going over the hurdles (i.e. staying low at the start, or positioning the landing leg for touchdown to decrease ground contact to maintain velocity through the take-off stride). In the case study later in this chapter, we show how keeping low and being fast through the first few steps may be important to consider when designing practices to improve the start, for a hurdler who is attempting to improve this part of their performance.

A key role of the coach in T&F constraints-led coaching is to ensure that the constraints employed encourage learners to ‘find’ these fixed principles. For example, for age group hurdlers, taking off from the ‘right place’ can be problematic as the distance between and height of hurdles changes as they move from one age group to the next. Consequently, in order to help a young athlete who is in transition between age groups and needs to re-calibrate his or her stride patterns to adapt to a new set of competition specifications, spatial markers such as cones can be placed before a hurdle (see Figure 9.1), to act as a guide for the learner, providing the opportunity to re-calibrate his or her actions and enable a take-off position that affords the athlete the opportunity to ‘hit’ the ‘fixed position’ when clearing the hurdle (i.e. the cones act as constraints to afford).

Purpose over process

A key requirement of adopting a CLA in T&F is to ensure that the primary goal or intentions of the practice task are not trumped by the constraints employed. T&F, similar to other sports, is susceptible to devices and gadgets that purport to be the magic bullet to enhance performance. It is therefore essential that any devices employed in practice must support the attainment of the primary goal. For example, if the goal is to increase a runner’s speed, any constraint added should not act to significantly slow the athlete down, per se. For example, one task constraint widely used by coaches as well as strength and conditioning practitioners is ‘Speed–Agility–Quickness’ ladders. However, the movement patterns that are developed have been questioned by top coaches, who suggest they actually lead to lower knee lift and reduce stride length in attempts to increase cadence. Clearly, there is a need to better understand the fidelity of training practices to performance environments that move beyond the (purported) scientific analysis of physiological development and better understand how practices such as SAQ impact on skill adaptation and therefore performance outcomes.

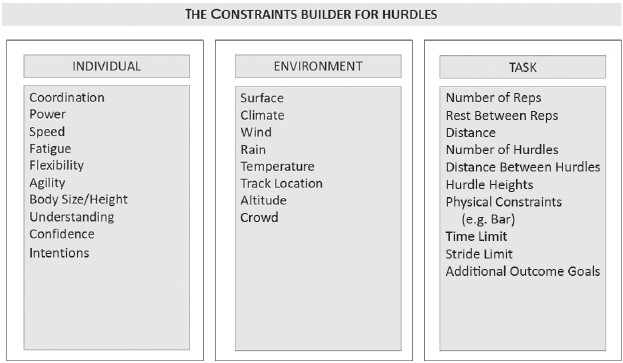

External focus of attention

A key principle for the adoption of CLA in T&F is the use of an external focus of attention to help athlete’s self-organise movements. For example, in hurdling, markers can be placed on the track (after the hurdle) to encourage the athlete to bring (coaches sometimes refer to this as the ‘snap’) his or her foot down quicker and therefore closer to the hurdle and ensuring that the horizontal breaking force is limited (a hurdler will need to land in an aligned vertical position), enabling the athlete to continue their running stride without a break in their momentum. Figures 9.2 to 9.4 illustrate how using an external marker can help a hurdler who is ‘jumping’ over the hurdle (Figure 9.2) to instead ‘run’ over it (Figures 9.3 to 9.4).

Figure 9.1 Constraining the penultimate step in hurdles to encourage finding ‘fixed principles’ in the movement regarding efficiency over the hurdles.

Figure 9.2 Without an informational constraint to provide opportunities for external focus of attention, here we see the hurdler perform a ‘jump’ over the hurdle rather than running over it.

Throughout Figures 9.2 to 9.4 the use of constraints focuses on functionality and considers the principles of ecological dynamics and the constraints-led approach. In summary, CLA is an effective approach for T&F coaches who can apply the theory to practice underpinning their session design. In fact, in many ways, CLA is easier to use with individual sports as the only concern is to support the development of intra-individual–environment co-ordination, in contrast to team sports where inter-individual–environment co-ordination also needs consideration. To further demonstrate how CLA can be used in T&F, we describe the CLA session design process using the case study of Natalie, an up and coming talented 16-year-old athlete.

Case study – Natalie

The current landscape – knowing the athlete (session intention for Natalie)

Before deciding on the session intention, it is important to understand the current landscape for the performer(s). When collecting information about Natalie, the coach, Matt, needed to gather both qualitative and quantitative information in order to develop learning and performance environments that elicit development. Natalie is a good national level athlete with international aspirations. Her current UK U20 ranking is top 30 for hurdles and high jump and top 25 for heptathlon. She is a senior champion for hurdles and high jump and is still only aged 16 years old. Natalie takes part in a few other sports (some team sports and individual sports) but is predominantly focussed on hurdling given that she shows a great deal of promise in this discipline. Matt is aware that the components that are key to Natalie, are speed (sprinting and a slight forward lean) and hurdle clearance time. Specifically, to keep the speed high and minimise flight time, Matt is keen to work with Natalie to understand her capabilities to perform (in terms of her take-off distance, clearance of hurdles and landing, etc.)

Figure 9.3 With the introduction of markers on the floor, the athlete searches for this informational constraint and this can promote self-organisation to develop the stride pattern to ‘run over’ the hurdles.

Specifically, Matt has identified that he needs to help improve Natalie’s starts, something she is also aware of. When Matt first started coaching Natalie, he posed a number of questions when trying to understand her performance history and aspirations (see Chapter 8 where we discuss the importance of this in detail) and one key aspect was that her background in other team sports meant that she had never really developed her race starts, as often her speed was exhibited in games. Using video analysis of Natalie’s movement patterns and studying her aspirational split times (see Figure 9.6), Matt was able to identify that Natalie was ‘coming up too early’ and needed to stay lower to the ground for longer. In Figure 9.5 you can see that the effect that coming up too early is having on Natalie’s posture as her leg is in front of her body and this stride length is causing her to create breaking force in her running stride. The aim in a hurdle start is to ‘set up’ the first hurdle clearance while running at optimal speed to be able to get into a good rhythm when running over the hurdles. With regards to her ‘start’, Natalie is trying to experiment with staying low for as long as possible giving her sight of the first hurdle as well as generating the optimal speed she wants to achieve for competitive racing times. Previous coaching interventions have left Natalie feeling as though she is just focussed on the competition (e.g. going from race-to-race) without having the specific developmental focuses she needs to improve her overall goals. Consequently, this has resulted in Natalie practising by focussing on ‘running fast’ and not on developing the required running rhythm for hurdling that would result in her developing an appropriate stride pattern that enables her to take off from an optimal position at the first hurdle. She has found in the past, that she is trying to run too fast (which sounds counter-intuitive but there is a balance to strike with the technical demands of the hurdles, and often the stride between hurdles is overlooked in development as athletes are encouraged to just sprint) and this often leaves her over-stepping with her landing leg, creating too much breaking force and foot contact time (which also brings about deceleration). Natalie is keen to develop and puts a lot of pressure on herself to sprint fast, but Matt has realised the need to work with Natalie on achieving a good balance between Natalie’s body position (form) and speed. Matt and Natalie have worked together to agree on the body position that is to be achieved, and although this is, essentially, a qualitative judgment (feel, look, haptics and aesthetics), it is also measurable as Matt and Natalie have agreed some split times (Figure 9.6) to have some goals that are measurable in line with Natalie’s aspiration to become one of the best athletes in the world. Consequently, Matt developed a session focussed on improving the start and worked with Natalie to focus on her acceleration and particularly on her body height during the first three or four steps of this phase. Figure 9.5 demonstrates the GROW model for planning these particular hurdles sessions.

Figure 9.4 The introduction of a tennis ball cut in half, and placed in the landing pattern of this athlete provides an external focus for the athlete to search for.

GROW planning process

In the following section, a completed example of the four-step GROW planning process (Figure 9.5) is utilised to demonstrate the approach taken for the particular case study. After identifying the goals for the session, Matt considered the Reality and Options to shape the Way Forward. In line with his goal, he decided to add in a task constraint of a 150 cm high horizontal bar placed 120 m in front of the blocks. Natalie would therefore have to stay low by maintaining a more functional body position and keep her head down in the first few strides before ‘coming up’. It also made her initially focus on getting through the barrier and delayed her focus from shifting to the first hurdle too early. Matt was also keen for Natalie to understand the importance of a fast start, without losing her rhythm and body shape over the hurdles so while they had an overall season goal in mind it was important to focus her body shape, which the constraint of introducing the bar is helpful for. Rather than her just giving her a general goal to run quicker though, Matt set the goal of reducing her current time to the first hurdle of 2.8 s to 2.5 s in line with the best times for her age group at the level of competition she is aspiring to reach.

What is the goal/intention for this session?

The goal of the session was to manipulate the forward lean in the acceleration/start phase of the hurdles.

How does this link to the overall goal?

The session will enable Natalie to develop a more explosive start by improving her ‘pick-up’ as well as enabling her to ‘sight’ the first hurdle.

Figure 9.5 Using the GROW model to plan a hurdles session.

The focus for learning?

The focus on learning here was to understand that staying low allowed Natalie to get an explosive start to the hurdles as well as achieve rhythm and a balanced state so that she could run over the hurdles effectively. This also links to the impact of contact time (foot contact acts as a decelerating rate limiter) and the position over the hurdles (if an athlete is sprinting, as opposed to running at an optimal pace which is fast, but rhythmical).

What is the current skill level?

The current skill level was identified as being in the ‘adaptability’ level, as Natalie is already a high performing athlete.

What affordances of the performance environment do you want to design-in to the practice?

The aim of the training session was to develop a fast, rhythmical start, attuning to the first hurdle in order to get over it at running pace and with a good body position that doesn’t slow Natalie down. The practice environment provided needed to include task constraints that would afford/invite the type of movement solution that Natalie needs to find.

Figure 9.6 Ideal times for the sprint starts.

Selecting the practice environment

Using the environment selector, Matt’s focus on the sprint start resulted in him selecting a short indoor space in a hall. This environment allowed him to keep Natalie’s focus on the start of the hurdles (in an outdoor space Natalie tends to want to just run the full 100 m as she likes the feel of a full race). The decision also allowed him to have a representative environment as the track surface is the same as Natalie’s home race track, and while there was not enough space to run a full 100 m, Natalie was, in fact, able to do more than simply practise her start and Matt expanded the practice to a four-hurdle start in order to afford Natalie the opportunity to ‘feel like’ the race and get a feel for how a good sprint start sets her up for the rest of the race.

Figure 9.7 The environment selector for hurdles.

Choosing the constraint to afford

Matt used the constraint builder to select the constraints he wanted to use to ‘invite’ Natalie to develop a more functional body position, one that would allow her to maintain eye contact with the floor at the start of the sprint, in order to stay low and visually attune to the first hurdle as she developed her optimal speed and rhythm into the first hurdle. To do this, Matt chose a mixture of individual, task and environmental constraints. As discussed in the earlier section, by selecting an environment where he was able to replicate the environment of the ‘real’ race, it afforded Matt the opportunity to direct Natalie’s intentions towards running optimally but with rhythm and control. Matt chose to add in the task constraint of the bar as well as replicating the competitive nature of her event by asking Natalie to focus on times to the first hurdle and create competitive environments by getting her to focus on some of her favourite world class athletes and their times to the first hurdle. This use of a virtual competitor (i.e. a time constraint) allows Natalie to compare her progress with other elite performers.

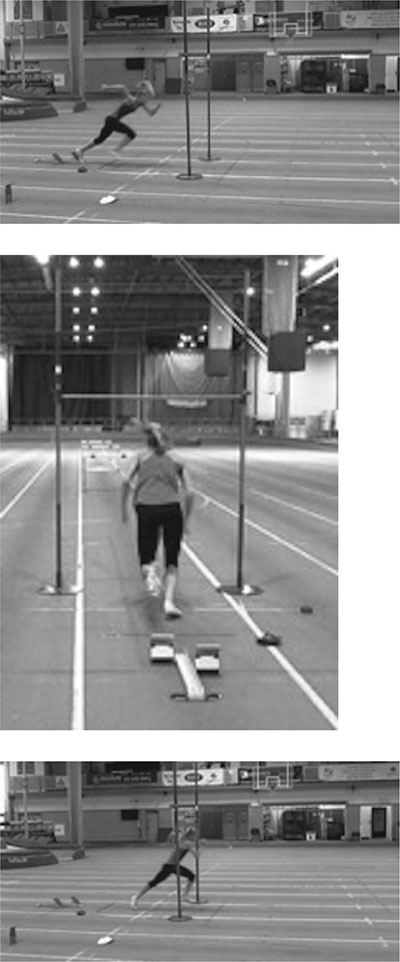

Figure 9.8 Using a bar as a constraint to afford staying low to concentrate on the first three explosive steps.

We will know we’ve been successful if . . .

There is an improvement in the times that are recorded for the ‘start’ of the race. This is recorded by measuring the times to the various hurdles. We will see a rhythmical and balanced running style that is compact and does not show signs of deceleration. This can be measured by witnessing the placement of the landing foot in effective positions that allow for velocity to be maintained or improved through the hurdles.

The session planner

Overview: once the practice environments and constraints had been completed, it was easy for Matt to fill in the details of the session planner. The dials in Figure 9.10 show how Matt manipulated the purpose and consequence of the practice task. In particular, the dials show that Matt increased the level of representativeness (of a full race) from Task 1 to Task 2 by adding more hurdles to the practice. While he did not structure a full 100 m sprint, he did add four hurdles to stimulate more competition by providing Natalie with ‘goal’ times to meet for each hurdle. This is a key part of meeting the session intention as Natalie will only manage this time with a good body position. Matt supplemented this by manipulating the task constraints by changing the height of the bar. This constant adjustment was important in inviting Natalie to get into a good position and seeing the response of Natalie to self-organising and improving her sprint starts and improving her awareness for how she started best.

Figure 9.9 The constraints builder for hurdles.

Task 1: a pre-test. Matt set up Task 1 to provide a baseline of Natalie’s current ‘start times’ to the first hurdle as well as to video her form in order to get both qualitative and quantitative measures such as video analysis of her body shape and also the quantitative measure of time. This task was completed without any additional constraints. Matt simply asked Natalie to try different things to get a quicker start and see how that felt.

Task 2: in Task 2, Matt set up a bar (seen in Figure 9.11) to focus Natalie in order to stay low and get under the bar. He started by placing the bar at 150 cm so that Natalie had to organise into a strong and balanced position (seen in Figure 9.12). Matt then lowered it and adjusted it throughout the session to find the optimal affordance. Natalie and Matt discussed the height of the bar at the start of each ‘sprint’ and discussed the feeling at every point. They discussed the feeling of running under the bar. Did it feel different? Comfortable? Did she feel like it was aiding or hindering her start? Natalie had to attune to the information provided and in adapting to the environment stays low to produce the body position and movement required in accelerating through the first phase of the start.

Figure 9.10 The session plan for sprint starts in hurdles.

Figure 9.11 Athlete getting ready to start.

Task 3: in Task 3 Natalie was required to ‘race’ through the first four hurdles while attempting to match or beat the competitive times of her favourite athletes as a ‘virtual’ opponent (e.g. a time constraint).

Session reflection

Matt used the bar to manipulate the forward lean in acceleration in order to improve Natalie’s performance and functional movement. The bar therefore achieved Matt’s key focus, which was to ensure that Natalie did not attempt to achieve an upright running posture too early in the run. The times that Natalie was successful, she was able to accelerate into her stride patterns and attune to the visual cue of the first hurdle, a key reference point for Natalie on race days. By staying low, and adapting her movement patterns to the bar, Natalie was able to produce greater acceleration. In order to stay low, she is encouraged to look at the ground and ‘search’ for the first hurdle only once she is through the bar. This is typical of hurdlers who will explode through the first few steps before searching for the visual cue of the first hurdle. While the race (and phases of the race) are practised, it is not as simple as always running the same number of strides, with the same power, explosion and height of the hurdle, and as such it is important to practise with representative and variable practice opportunities.

Figure 9.12 Going under the bar and accelerating through the first phase.

There are a number of nuanced and complex challenges that we have come across in developing a session that utilises a CLA in hurdles. Do the cones over-constrain? Is it really an affordance to run under a bar? In using the GROW model approach to design a constraints-led session, it is helpful when reviewing a session. The intention was to try to help Natalie stay low and increase her pace through the first three-step phase. In staying lower, and not lifting her head to visually focussing on the first hurdle until she had passed through the bar, she is able to focus on her pace through the start. In reflecting on the session, we can identify that there are some issues with using constraints and ‘getting it right’. Much of this is to do with knowing your athlete as we have discussed at length in previous chapters. We must respect the athlete’s relationship with a performance environment. When trying to build constraints into session design it is important to recognize key sources of environmental information that underpin the functionality of an athlete’s relationship with that environment in adapting actions to meet the problem faced. This is a key task for coaches and practitioners. In this particular session there are some fixed principles that are important. Using the bar as a task constraint, we are able to afford Natalie the opportunity to act by staying low, looking at the ground before raising her head to attune to the first hurdle and therefore act on the invitation (distance to the first hurdle means the athlete will coordinate and adapt their stride length to meet that first challenge). The use of the bar meant that the session intention was met as it was clear that Natalie was able to maintain pace and adapt her movement solution to the constraint. The invitation to act is implicit in the design of the learning environment and can also be explicitly guided by the coach by inviting the athlete to attune to the need to stay low and produce acceleration in the first phase of the race. These external foci lead to greater learning opportunities. Finally, it is important to consider individual differences, in so much as we need to assess constantly the physical, psychological, technical, strategic and emotional parameters of an athlete in order to meet the needs of the learner.

Summary

In this chapter we utilised a case study to demonstrate the use of the CLA for individual, technical sports. The examples from hurdles were used to show how the CLA can be used in an individual discipline like track and field and that, as coaches, we should not be afraid to explore the affordances in convergent sports in the same way we do in divergent sports. Utilising some guiding principles (Here we spoke about Purpose over Process and External Focus of Attention) to guide how we design constraints-led environments, we can support athletes at the performance level to explore the landscape of affordances available to them in order to invite action in convergent sports in a similar way to those of team sports, but with greater emphasis on the freezing and unfreezing of degrees of freedom in order to elicit the control of variability and instability in coaching. We have provided brief examples of how a CLA could enhance the practice of athletics coaches. We will build on these ideas in more detail in a forthcoming book in the series: A Constraint-Led Approach to Track and Field Coaching. This book will be jointly written by ourselves and international athletics coaches and movement science specialists from Physical Preparation backgrounds (S&C / EIS) coaches who will provide the unique examples from their own work with performance and development athletes. We look forward to sharing and discussing further ideas with you there.