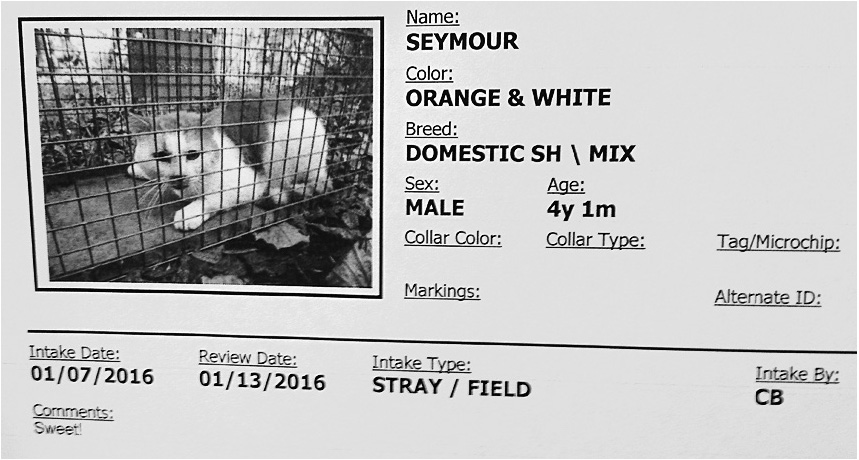

This shelter review form shows Seymour in a humane trap when he was taken in to the shelter. You can see his fearful aggressive body language in the photo.

Sara Bennett

Sara Bennett, MS, DVM, DACVB

A beautiful orange and white cat had been hanging around Susan’s house for weeks. He looked thin but alert. He was skittish and would not let her get close. She began leaving him food, and he would creep up to eat as soon as she left the area. After several weeks of feeding him, Susan could get closer and closer to him.

One very cold night, he decided he would come into the safety and warmth of the garage. Feeling bad for him, Susan eventually let him into the house. Things went downhill from there. He hid all the time, hissed when she came near, and did not use a litter box. Her good deed became a disaster.

Cats who live outdoors without much human intervention are free to express their normal behaviors, but that freedom comes with risks. They can suffer injuries from cars and trucks, attacks and possible death from dogs or other animals, hostility from some humans, parasites, and other medical problems. They also may endanger other species through their prodigious hunting ability.

Often these cats come into our homes, but because of their lack of prior exposure to a home environment and what it entails, they are fearful and may have difficulty adjusting. Many require specific interventions (including medication) to make them comfortable with indoor life and human companionship.

In this chapter, you will learn how to help and understand feral cats—whether it is just one cat or a large group—and find up-to-date information on trap-neuter-return programs and feral cat colony management strategies and sanctuaries.

The subject of outdoor cats can be a volatile one. There are many different points of view, including those of cat lovers, veterinarians, and wildlife advocates. It is no secret that cats living outside have a higher risk of disease and injury and that they prey on wildlife such as small rodents, lizards, and birds. Some suggested solutions to the “problem” of outdoor cats include keeping cats strictly indoors; bringing all free-roaming cats to an animal shelter or euthanizing them; or trapping, neutering, and releasing or relocating all free-roaming cats.

While all of these ideas could be viable options for individual cats, none of them works well as a “one size fits all” solution.

Are all outdoor cats the same? Definitely not. A cat found outside may belong to someone who lets him go outside. An outdoor cat might also be someone’s indoor cat who got lost after accidentally getting outside. Worst case, an outdoor cat may be a socialized cat who was dumped outside. And some outdoor cats may truly be feral cats.

What’s the difference between an indoor-outdoor cat and a feral cat? The answer lies in socialization. A feral cat is the offspring of domestic cats but has had little or no contact with people, especially during his sensitive developmental socialization period as a kitten. This cat will behave essentially like a wild animal, even though he still belongs to a domesticated species. He will fear people and do everything he can to avoid them. If he can’t, he will defend himself against them, just as he will if he encounters any predator.

Socialization: A learning process that occurs only during the sensitive socialization period when kittens are especially receptive to being exposed to different environments, situations, and individuals of their own and other species. If they’re exposed in a positive manner to people, other cats, dogs and other animals, handling, and a variety of different environments and situations, they will be less likely to be fearful of them later in life. In cats, this period is generally accepted to be between two and seven weeks of age for prime socialization to people. The term “socialization” is often incorrectly used when what is really meant is exposure, since socialization occurs only during a specific period of time in early life.

Domestic cat:Felis catus, a small, typically furry, carnivorous mammal. Feral, semi-feral, stray, and pet cats are all domestic cats. They are all the same species; the difference between them is the level of social experience they have had with people.

Stray cat: A domestic cat who is unowned. Typically, these cats live outside and work to gain the necessary resources—such as food, water, and hiding and resting places—on their own, without the help of the people living in their territory. A stray cat may have a variable level of socialization. He could previously have been an owned cat who escaped outside or got lost, been abandoned, or been born and lived his entire life outside. The biggest difference between a stray cat and a feral cat is the level of social experience with people. Stray cats have some experience with people; feral cats have none.

Feral cat: An offspring of domestic cats who has had little or no contact with people. This cat will behave essentially like a wild animal for his entire life, even though he belongs to a domesticated species. He will avoid and be afraid of people.

Community cat colony: A stable group of cats living together in a neighborhood and managed by the people living in the area. These cats share food sources, might have preferred associates (cats who like one another and choose to spend time together), and might help raise one another’s offspring. Ideally, if the colony is managed by one or more human caretakers, most of the cats in the group will have already been spayed or neutered, so breeding will be minimized.

Colony caregiver: A person or group of people who act as caregivers for a colony of cats. These people help monitor the cats’ health, supplement feeding as needed, and identify newcomers to the colony who need to be captured and spayed or neutered, and who may have a disease or injury that needs to be treated.

Trap-neuter-return (TNR): A program in which feral cats are trapped, spayed or neutered, and then returned to the colony where they were trapped. This process also includes examination by a veterinarian, treatment for whatever health issues are treatable, and vaccinations.

Classical conditioning: A process whereby an individual makes an involuntary emotional association with something that had no previous meaning to them, because that thing has now been paired with something inherently pleasant or unpleasant. Also called Pavlovian conditioning. An example is a cat learning that the sound made by a clicker means a treat is coming, and so the cat begins to show more positive responses when he hears the click. Alternatively, a cat might learn that his carrier comes out only when he has to go to the veterinarian, a frightening experience, so he begins to hide whenever he sees the carrier. (See chapter 6 for more on this topic.)

Capturing: A training method that uses positive reinforcement (see chapter 6) to reward desired behaviors that are spontaneously displayed by an animal. This can be done at a distance by using a reward marker such as a clicker and then tossing treats to the animal when he shows the desired behavior. This method is particularly suited to training fearful or aggressive animals.

What would happen if all outdoor cats were captured and taken to a shelter? For owned cats whose owners let them outside, owned cats who have become lost, and possibly even cats who were intentionally dumped outside, this might not be a bad thing. They all have a chance to be reunited with their owners—if those owners decide to go looking for them. But sadly, most cats brought to shelters as strays, even friendly cats who are clearly not feral, are never claimed by an owner. Some do get adopted by other families, but they will usually only be chosen if they look and act like an enjoyable companion.

Deciding which cats to put up for adoption isn’t as simple as choosing those cats who look like friendly house pets for the adoption floor and putting back outside (or euthanizing) the rest. Even the best-run shelter is a stressful place for a cat, which translates to fearful behavior. That means most cats in shelters are probably not showing you their true personality because they are so stressed. Of course, a truly feral cat will be highly stressed in a shelter. But so will a shy owned cat or an older house cat who is used to being pampered.

All kinds of cats who might make great pets can be seen hiding in the corner of their shelter enclosures, or even acting aggressively when approached, since they are afraid and cannot get away. Cats who are stressed also are much more likely to get sick, further reducing their chances of being adopted. Fear-related behavior does not tell us anything about a cat’s level of socialization. How can we reliably tell fearful and feral cats apart? It’s a question all shelters struggle with.

What would happen if all feral cats were trapped, neutered, and returned? Known as TNR, this is a process whereby outdoor cats are trapped, spayed or neutered, and then returned to the outdoors. Typically, this process also includes examination by a veterinarian, treatment for medical problems, vaccinations, and humane euthanasia if a cat is too ill or injured to survive outside.

The “R” in TNR can be a little controversial. It can mean returning the cat to the environment where he was trapped, releasing him either back to the place where he was found or somewhere else, or relocating him to a different location.

The current standard of care emphasizes returning the cat to the environment from which he came, if at all possible. Cats are very bonded to their home territory and will go to extreme lengths to get back there if they find themselves in a different place. This can be quite perilous for a cat, especially if he has to travel across busy streets and highways, where the risk of being hit by a car is high. Cats within an existing colony are usually not welcoming to newcomers, so an unfamiliar cat dropped off at another cat colony might be chased off or injured in a fight.

Relocation might be necessary if a cat comes from an area where he is at great risk of injury, if the area where he lives is somehow changing (for example, a building is being put up on a formerly empty lot), or if he is living in an environmentally sensitive area, such as a wetland refuge. The best way to relocate cats, however, is as a colony, so that at least they do not have the stress of trying to establish new social bonds. The cats should be supervised by the colony caregiver for the first few days to ensure that they become used to their new location and can find plenty of food and shelter—factors that are critical to them considering it their new home.

TNR is most effective as a way to control feral cat populations if most of the cats in a colony are trapped and treated in a short amount of time. Dr. Julie Levy and her team at the University of Florida found that trapping, neutering, vaccinating, and returning 75 percent of the cats in a targeted neighborhood led to a significant decrease in the size of the feral cat population in that area and also reduced the number of cats brought in to the local shelter. This approach essentially creates a stable nonbreeding colony of cats. The resident cats will chase off other cats who might want to settle down there (and breed), and eventually, as the cats become older and die, the colony will disappear on its own.

Generally, a colony of TNR cats is managed, meaning it has a person or group of people who act as caregivers. These people help monitor the cats’ health, supplement feeding as needed, and identify newcomers to the colony who need to be trapped and spayed or neutered, or who need to be treated for a disease or injury. The goal in managing a colony is to make sure that the number of cats doesn’t exceed the population the environment can support (food and other resources), and also that the caregivers and the surrounding community aren’t overwhelmed. TNR programs help caregivers meet this goal in a humane manner.

If the environment cannot sustain the number of free-roaming cats and keep them safe, what is the best option for the cats, the wildlife sharing the area, and the people the cats live among? Often a combination of strategies ends up being the solution. That means targeted TNR; adopting out friendly and well-socialized cats and kittens; and educating the community about the importance of spaying or neutering and vaccinating their cats, keeping their cats on their property and not letting them roam the neighborhood, and not dumping them outside.

When a plan like this is implemented, the cats will have less competition for food and less disease, the wildlife will be subject to less predation, and the people in the community will have less public health risk and nuisance from feral cats. It is important to remind residents that allowing feral cats to stay in their community and also spaying or neutering them costs less for the community and the organizations trying to help manage the cats than keeping them all in a shelter of any kind, including an enclosed sanctuary.

Community involvement is key to the success of such a program, because people in the neighborhood play a crucial role in monitoring the cat colony and educating their neighbors about humane care. There is a deep bond between colony caregivers and the cats they care for, and many consider the cats their pets, even if they cannot touch them.

When outdoor cats are trapped as part of a TNR program, the cats who are friendly to people, as well as young kittens, can be taken to a shelter and offered for adoption. The TNR team working in the community can help educate the people who live there and those who care for the cats about why it is important to get the cats spayed or neutered and vaccinated, and offer resources to help them do so. This is a more effective approach than just coming in and taking control of the situation.

Cats taken from a high-risk area will be candidates for strategic relocation to an area that’s safer for them and the local wildlife and where a colony caregiver can help acclimate and monitor them. These cats might also be considered for a working cat program, such as pest control in barns, warehouses, or other places where their keen skills as hunters will be valued.

What should we do with shelter cats? Remember, even the best-run shelters are stressful for cats. The cats are away from their home territory, possibly separated from their beloved people, out of their routine, and out of their element. There are so many novel sights, sounds, and smells. Because cats’ senses are much more acute than ours, if we think something is loud or strong-smelling, you better believe the cats are even more offended by it. In addition, everything is unfamiliar and out of their control, and they may not have adequate places where they can hide and feel safe. Cats are hardwired to hide when they’re frightened, and if they can’t, they become very distressed.

It is important to be able to identify cats who have some level of socialization with people, so that they can be moved to the adoption floor or to foster homes. Cats with no positive social experience—feral cats—should not be housed in the shelter any longer than is absolutely necessary, because the shelter environment is even more stressful and frightening for them. Ideally, they should be quickly identified, spayed or neutered, vaccinated, and returned to their colony.

It is inhumane to keep feral cats housed in a shelter without adequate facilities specifically for them (some shelters have a safe outdoor enclosure where cats can live with minimal handling and supervision) or to try to adopt out a feral cat as a house pet. Attempting to tame and acclimate such a cat to an indoor-only home would be extremely stressful for the cat and have a low chance of success. These cats are easily frightened and can become defensively aggressive very quickly, because they perceive any attempted human interaction as a life-threatening situation.

How do we determine which cats are socialized and which are feral? There is a difference between a socialized cat found outdoors and a truly feral cat. A socialized cat may begin to show some social behaviors around people after he has had a few days to acclimate. A truly feral cat will never show any social behaviors, no matter how much time has passed.

That is why it is so important to give cats time to acclimate when they first enter the shelter. A sweet house cat may seem like a terrified feral cat when he first comes in. Ideally, acclimation means one to three days in a quiet room away from the hustle and bustle of the shelter, especially somewhere the cat won’t hear any barking dogs. Each cat should be given somewhere to hide inside his enclosure, and his food should be placed near the back of his cage so that he doesn’t have to go to the front—where he will feel more vulnerable—to eat.

A quiet, calm, pleasant, patient caregiver should look after the cat on a fixed schedule. This person can spot clean the cage for a few days, rather than deep clean it every day. The cat should be monitored for signs of potential interest in social interaction with the caregiver. The ASPCA has developed a series of behaviors to watch for, called the Feline Spectrum Assessment (www.aspcapro.org/research/feline-spectrum-assessment), that might suggest some level of previous socialization. If the caregiver sees any of these behaviors, the cat can be placed on the path to being adopted.

This shelter review form shows Seymour in a humane trap when he was taken in to the shelter. You can see his fearful aggressive body language in the photo.

Sara Bennett

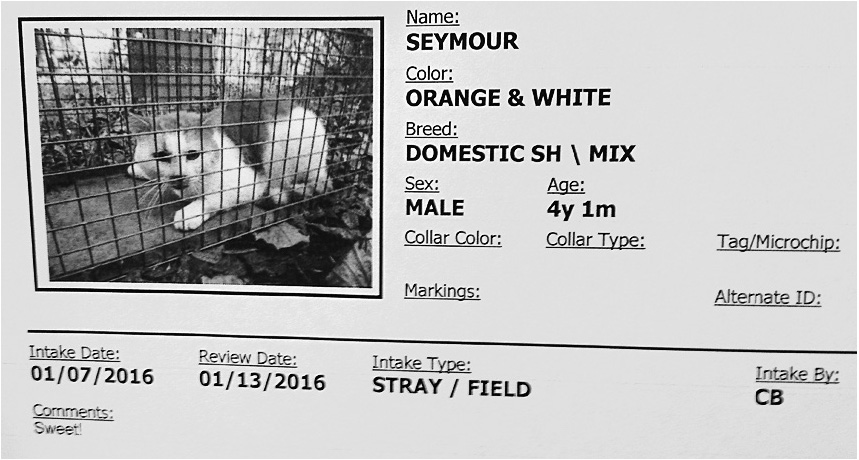

Look at the change in Seymour after he became acclimated to his cage at the shelter. He is lowering his head for a pat.

Sara Bennett

What about kittens of feral cats? The socialization period for kittens is the developmental stage when they are especially receptive to being exposed to different environments, situations, and individuals of their own and other species. If they’re exposed in a positive manner to people, other cats, dogs and other animals, handling, and a variety of different environments and situations, they are less likely to be fearful of them later in life.

The most sensitive socialization period is between two and seven weeks of age. When kittens of feral mothers are exposed to people during that time, they usually become acclimated to regular human contact and can make good pets. Kittens who are not exposed to people in a positive manner before three to four months of age will most likely always be afraid of people and should be considered feral.

This exposure must be done slowly, by a patient, friendly, positive person. Give them a day or two to acclimate to the environment, then handle them for very short periods three to four times a day. They can be separated from one another during this time but otherwise should be kept together for their emotional well-being and social development. Start with the least fearful kitten, to avoid getting the other kittens scared and upset if the one you handle reacts with fear.

Begin the handling exercise by gently picking the kitten up in a towel, then softly stroking him on the head. He can be hand-fed now, too. Remember, if you do it slowly and gently enough, the kitten should not react with fear, but rather become more relaxed over time and even start to enjoy some of the handling and stroking. If the kitten shows fear, slow down.

How do you acclimate a feral cat to a new environment? If you have to relocate an adult feral cat, you can try to help him learn about his new home. For example, if the cat is placed in a barn, at first keep him in a large crate or a small room, such as a tack room, with his food, water, bed, scratching and hiding areas, and litter box inside. He can have regular visits from his new caregiver for meals and spot cleaning. After several days, he can start to have more space, such as being let loose in the tack room or barn when his caregiver is present, but he should be returned to the crate or tack room when the caregiver leaves. If you let him out at mealtimes, he’ll stick around for the food, which will help create the association that this is now home.

After about three weeks, the cat can be let loose in the barn for longer periods. It is possible that he might still disappear for a day or two, but if the caregiver keeps putting out food at mealtimes, most likely he will eventually turn up for dinner.

Hopefully, the fearful but social cat has been either adopted into a quiet home or placed in a foster home. That’s great, because he is out of the stressful shelter environment. But now what? There are many things you can do to try to help this kitty feel more comfortable and less fearful in his new home.

One of the most common mistakes we make when bringing a fearful, shy cat home is to make his world too big, too fast. Rather than give him immediate access to your entire home and pushing him to meet all the family, two-legged or four, on that first day, take it slow.

First, set up a room just for him in your home. It should be a quiet, comfortable room that is not used frequently by the rest of the family. He should have his litter box, food and water, a comfortable resting area, a place to hide, a scratching surface, and something to play with in this space. (See chapters 2 and 3 for some ideas about the best way to set up litter boxes, feeding stations, and resting areas.) The addition of a plug-in diffuser with synthetic feline facial pheromone (Feliway Classic) can help some cats feel more relaxed.

Even in his own quiet room, kitty will need a hiding spot. A box, crate, or carrier will do—anything that he can climb into so that he can feel hidden and secure. He’ll be more likely to use his safe space if you put it up off the floor somewhere—on a shelf or the top of a bookcase, for example. It’s okay to block off access to places where you don’t want him to hide, such as underneath a sofa, but only if you have provided him with another suitable option.

The hiding spot will be more appealing if you line it with a blanket or towel and cover it with another one. You can spot clean this bedding to remove large amounts of hair, but don’t wash it frequently. This will help ensure that the space smells like the cat and is familiar and comforting. If you need to wash it, put a new piece of bedding in with the old for a day or two before you remove the old bedding to wash.

If you think your cat would enjoy sitting by the window, try putting a hiding spot at window level. The opening should not face the window, but look off to the side. That way, he can go in the hiding spot, poke out his head to look outside if he wishes, then immediately retreat inside if he wants to hide.

The next most important thing you can give a shy kitty is time—quiet time alone to acclimate. Just as cats in the shelter need a day or two to begin to get used to their surroundings, your shy cat will need the same thing in your home. Remember, this is an unfamiliar environment for him. Put him in his room and do not disturb him or allow people or other pets to visit him for the first few days. You can go in quietly to refresh his food and water and scoop his litter box, but do not try to interact with him when you are there. Just take care of his housekeeping and leave.

On the third day, try sitting quietly in his room for several minutes. This is a good time to read a magazine, check your email, or even meditate. The goal is for him to get used to you being there, so ignore him if he ventures out of his hiding spot. Let him control how much distance there is between you.

After a few days of this, if he is venturing out while you are in his room, you can begin to add some short, neutral interactions. These can be as simple as reading aloud from your favorite book, talking softly to him, or even rolling a toy around a little. If he ventures near, toss a small morsel of yummy food in his general direction. Do this using a low, underhand toss, so you don’t have to move your arm too much and it doesn’t seem as if you’re throwing something at him.

Don’t be offended if he scurries back to his hiding spot or doesn’t eat it right away. You’ve just changed the game, so he needs time to figure it out. Remember, if he eats the food treat, even if it takes him several minutes, he can still learn through classical conditioning to associate you with good things (see chapter 6).

Favored treat flavors for kitties include cheese, sardines, anchovy paste, meat baby food, and yogurt. Many commercial treats contain these ingredients. Or you can freeze these foods in small ice cube trays to facilitate delivery. Another idea is to make a small food-dispensing toy so that you can roll the treat to him. One half of a plastic Easter egg works great to send a little anchovy paste across the room to him in a nonthreatening way.

You can use food-dispensing toys to offer your new cat some enrichment that doesn’t force him to interact with you. They will give him an opportunity to seek out and work for his food. You can buy toys made for cats, or you can make them yourself out of small plastic containers or cardboard toilet paper rolls. (See “The Three-Minute Food-Dispensing Toy” in chapter 11.) Fill a toy with food and put it in the cat’s room before you go to bed so that he will have access to it throughout the night.

You can also add short play sessions using a fishing-pole toy or a string toy. (Never leave a cat alone with string or yarn, however, to avoid accidental ingestion.) These toys will create positive interactions that feel safe to the cat (far enough away that they do not involve touch) and will help him learn to trust you.

Don’t despair if it takes several weeks to see improvement. A survey done by Dr. Sheila Segurson, DACVB, the research director of Maddie’s Fund, found that most foster caretakers and new owners reported it took at least two weeks for a fearful cat to begin to come out of his shell and interact. Remember to keep to a regular schedule for his feeding, cleaning, and visits, so that he knows what to expect throughout the day. This can be very helpful in reducing anxiety.

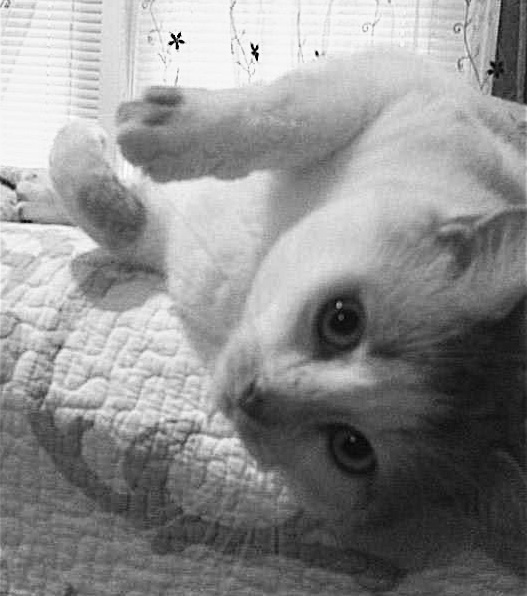

Here is Seymour, calm, relaxed, and happy in his new home.

Sara Bennett

After a few weeks, you can begin to try some more social interactions. Start by asking for a nose touch as a way to initiate an interaction. Hold out your index finger near his nose and let him choose to touch your fingertip (or not). If he does, you can then stroke him between his ears, on his cheeks, or under his chin. Do this using only one hand, and for no more than three seconds, then pause and ask for another nose touch. If he offers his nose again, you can pet him for another three seconds. If he doesn’t offer his nose, just leave him alone. You can also try this with brushing rather than petting.

Watch your cat’s body language closely during all of these interactions to see if he is interested in interacting or would prefer to be left alone. Signs that he is more relaxed and interested include a leg stretched away from his body, his tail loose behind his body, or his whiskers or ears forward. Signs that he is more worried or would prefer to be left alone include his head and neck tucked close to his body, his legs or tail wrapped or tucked close to his body, his whiskers back flat against his face, or his ears to the side or back.

If your cat shows signs that he would prefer to be left alone, respect this and do not force an interaction. The more you honor his preferences, the more he will begin to trust you. (See chapter 1 for more information on reading cat body language.)

You can also incorporate short, fun training sessions into your cat’s daily routine using positive reinforcement training (see chapter 6). This is a great way to help teach a shy cat that interactions with people are safe. During these training sessions, use a clicker or a word, such as “good” or “yes,” to mark the moment he does something you like, then follow it with a food treat.

For example, if he touches his nose to your finger, say “good” with a happy tone of voice and give him a tiny morsel of food. Repeat and repeat and repeat. When you know he is likely to do this behavior whenever you hold out your finger, you can start to use a word to cue the behavior. For example, a common cue for a nose touch is “touch.” Say “touch,” then hold out your finger. When he touches it, click or say “good,” then give him a treat.

If your cat is too fearful to approach your finger, you might try using a target stick rather than your finger. The stick can be any long, thin object, such as a pen or pencil, a chopstick, or an extendable pointer.

The cat approaches for a nose-to-finger touch, a friendly greeting. This is a natural behavior.

Rebecca Gast

You can easily capture the nose-to-finger touch behavior by using a target stick instead of your finger.

Lisa White/Courtesy of Karen Pryor Academy’s Better Veterinary Visits Course

You can also teach your cat to come on cue by saying his name, then picking up his food scoop or opening the food bag. As soon as he gets to you, give him a morsel of food.

These training exercises use a technique called capturing, where you simply wait for the cat to offer the desired behavior, then reward it, rather than trying to lure, prompt, or force him into doing it. This technique is especially great for shy or fearful animals and is used frequently when training exotic or zoo animals.

Once your cat has begun to come out and investigate when you enter his room, or at least doesn’t run away immediately when you enter or move around, you can begin to offer him some freedom to leave the room. Give him access to another room or two. Do this at quiet times and for short periods, but make sure he has appropriate hiding spots in those rooms and can also get back to his safe room if he feels he needs to.

You can begin to introduce him to other people, too. Have another person accompany you into his room during housekeeping or interaction time. Initially, they should stay quiet and still. Once he starts venturing out and taking treats, they can begin to participate in the same kinds of positive interactions you’ve been having.

You can gradually introduce other pets of any species by putting up a baby gate or a screen door in the doorway to your cat’s room. (Don’t bring other pets into the safe room.) Dogs should be on a leash so they don’t rush the gate and can be moved away quickly and safely if they bark or frighten the cat. The best response is for both parties to ignore each other through the gate. Use food rewards for both pets when they show appropriate behavior during a session.

It is important to realize that your fearful cat may always have some limitations. Though he might warm up to you and your family, newcomers and visitors may always be a problem. We see this behavior in feral cat colonies with regular caregivers, too. The cats might learn to accept and perhaps even allow brief periods of touching by one or two very familiar people, but the same luxury is not afforded to other people, even if they are quiet, calm, and patient, and bear good things such as food.

In your home, don’t be surprised if your guests never meet your cat, because he runs off to hide as soon as he hears them at the door. That is okay. As long as he has a safe place to hide and nobody bothers him, he will recover and come back out within a few hours of the guests leaving. This is an appropriate coping strategy for him.

Be his advocate and advise guests not to seek him out or try to touch him or interact with him if he does venture out. Guests can toss a yummy food treat or a favorite toy in his direction but should otherwise ignore him. Remember that shy cats are easily frightened and can become defensively aggressive very quickly, because they perceive any unwanted human interaction as a life-threatening event. If a visitor pushes your cat’s limits and goes looking for him, this extreme fear response could result in a significant setback for him and potentially undo much of the hard work you’ve patiently put into gaining his trust.

Another possibility is that your cat may be willing to be around you and even enjoy your company, but he doesn’t want you to touch or pet him. That is also okay. You can interact with him through play—using toys you can toss or objects on fishing poles or strings—or even through training. Over time, some cats will learn to tolerate and perhaps even appreciate brief touching or petting. But remember to always respect your cat’s boundaries and limitations. You and your cat can have a healthy and fulfilling relationship without cuddling.

What if your cat doesn’t start to come out of hiding in his room? After at least two weeks of quiet with no interactions, it might be time to consider whether you can make some adjustments to help him feel more secure, or whether a medication or supplement might help reduce his anxiety and fear.

Remember, this is not just about you not being able to interact with him; it is also about his well-being. It is not healthy for him to be so frightened all the time that he never feels comfortable enough to leave his safe place.

Look at the hiding spots he has available. Can he truly feel hidden and secure in all of them? If not, perhaps you can reinforce them. Some cats feel better when they have a bed in a box inside an even bigger box, with a blanket placed over half the opening.

Sit quietly in the room and listen for a few minutes. Are there sounds your kitty can hear that might be frightening? Can he hear your dog barking in the next room, or the TV or video games downstairs? If so, think of ways you can reduce those noises. Cover the windows so the dog can’t see things outside to bark at, move the dog crate, or ask the kids to play video games in a different room. Or perhaps add some white noise or relaxing music to the cat’s room. (Two possibilities created especially for cats are the website Music for Cats, www.musicforcats.com, and Through a Cat’s Ear, a CD/MP3 series available from various outlets.) Remember that if you do this, you don’t want the volume to be higher than normal conversation. It doesn’t help to try to drown out loud noise with more loud noise.

If these steps don’t help reduce your cat’s fear in a few weeks, or if he starts to get so frightened that he reacts with hissing, swatting, growling, charging, or biting when you enter his safe room or when guests come over, it’s time to speak to your veterinarian about the possibility of adding a medication or supplement. There are many options that are appropriate and safe for cats. This is where a good relationship with a veterinarian who is knowledgeable about animal behavior is crucial. She can help guide you through the steps of reviewing your environment, management, and interactions to make the best choices for your cat.

One of the most important factors to consider and discuss with your veterinarian is how you will get the medication or supplement into your cat. He is already so fearful that trying to catch him and forcibly give him a medication will likely make things worse rather than better, and could even push him to show more aggression toward you. Finding a way to offer the medication in an appetizing fashion so that you don’t have to touch him to administer it will result in much less stress than trying to give him a medication forcibly by mouth, by applying it transdermally (to the skin), or even by injection.

The good news is that there are some name-brand formulations of behavior medications that come in highly palatable, chewable tablets and can be given to cats as a treat. Additionally, several generic formulations can be mixed with a special food that your cat enjoys. Some supplements are very tasty, too, and often cats will eat them like treats. (See appendix B for more information on giving meds to your cat.)

For some situations, there are veterinary prescription diets that may diminish anxiety and are quite palatable to cats. Again, talk to your veterinarian about this option.

The debate about whether it’s always best to keep cats strictly indoors is part of a larger debate about the best ways to keep cats as pets. Ultimately, you need to strike a balance between a cat’s physical and behavioral health needs.

This decision can be influenced by many variables. One is cultural. In some parts of the world, including some developed countries, people view it as irresponsible to let cats outdoors. In other areas, it is considered irresponsible to keep cats indoors all the time. While the decision to keep a cat indoors may be intended as a way to increase his life span and protect his health, doing so might not always be in the best interest of the cat if his environmental needs cannot be met.

Many socialized house cats are fine with staying indoors. They can be pampered with readily available food, water, resting spots, and indoor toilets (litter boxes). From some cats’ perspective, this is truly the lap of luxury. Ideally, these cats are well taken care of by the family veterinarian, including regular checkups, appropriate vaccinations, deworming, parasite control, and spaying or neutering. Their risk of injuries from fighting, predation, or being hit by a car is exceedingly low. But this is ideal only as long as their owner can provide for all of their basic needs, which go far beyond access to food, water, and a clean litter box.

Indoor cats also need regular positive social interaction—play, petting, grooming, and training. They need to satisfy their feline urges to hunt, climb, hide, and scratch. These needs can be met with food-dispensing toys, vertically placed resting options such as shelves and cat towers, and appropriate scratching surfaces. But for some cats, all that is still not enough.

Some cats require more enrichment than their owners are able to provide, and they become stressed or frustrated with the limitations of always staying indoors. Behavior problems can result, including aggression during play, inappropriate predatory behavior, destructive scratching, and house soiling.

Outdoor (or indoor-outdoor) cats, while they can enjoy a more fully enriched and varied environment, are exposed to risks that indoor-only cats do not encounter. They are at greater risk of infectious diseases, internal and external parasites, poisoning (intentional and unintentional), and injury due to trauma, such as being hit by a car or attacks from other animals or humans. Anyone with an outdoor space, however, can create a safe outdoor environment that will meet the needs of an active cat with a drive for a high level of novelty and variety.

The first step to letting your cat outdoors safely is teaching him to come when he is called. This is really quite simple, if you think about what a cat does when he hears his food bag or can opened at mealtime. Before opening the food, you can simply say your cat’s name and a cue such as “here, kitty.” He will come running in anticipation of being fed. Over several repetitions, he will learn that his name plus “here, kitty” means come to you, because a reward (food) awaits.

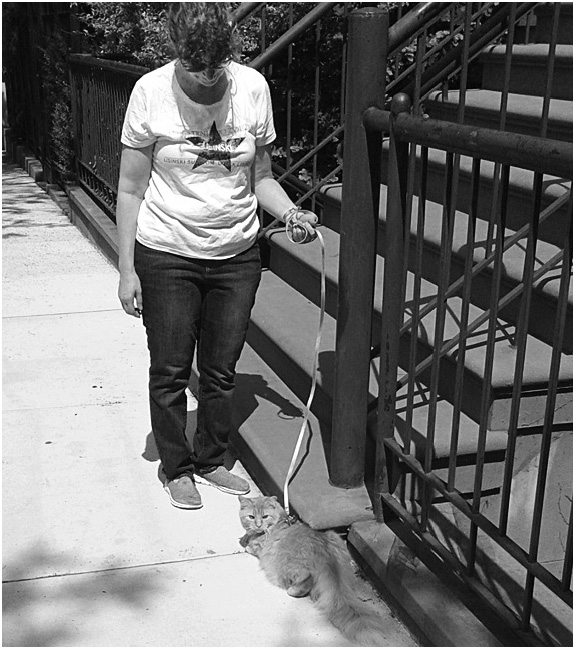

Spike can enjoy his neighborhood safely on a harness and leash.

Craig Zeichner

If you have an outdoor space, the next step is to put up specialized cat fencing or create an enclosed cat space, so that he can come and go as he pleases in this designated space and also be safe from the risks of wandering or intruders. In this way, you will not only minimize the chances of your cat getting hurt but also ensure that he will not bother your neighbors or any wildlife in your yard. (See chapters 3 and 5 for some ideas about creating an outdoor space for your cat.)

If you don’t have an outdoor space, you can train your cat to wear a harness and leash. Leash walks are not just for dogs anymore! This is another way to offer safe outdoor time to active cats.

Of course, all cats should have appropriate identification (ideally a microchip), updated vaccinations, and parasite management, but these are even more important for a cat who enjoys outdoor time.

Feral cats should be considered wild animals. People should not attempt to make them house pets. This is extremely stressful to the cats and can be dangerous.

Trap-neuter-return programs that target a specific area and catch as many cats as possible in a short amount of time, along with community involvement to help manage a cat colony, is one of the most humane, economical, wildlife-sparing, and effective strategies to manage outdoor cats.

How fearful a cat in an unfamiliar situation is does not tell us whether the cat is socialized to people. Feral cats and socialized cats can both show extreme fear in a shelter.

One of the biggest mistakes people make when adopting shy or fearful cats is making their world too big too fast. Slow and steady wins the race.

Start small when bringing a shy or fearful cat into your home. Remember to give him a quiet safe room where he can acclimate, and allow him to be in charge of the pace and intensity of his interactions. This will empower him to feel more confident and safe.

Never underestimate the power of a good hiding spot. Every single cat in every single housing situation—whether in a cage in a shelter, a group room in a rescue, or our own homes—should have easy access to a hiding spot. This can save a cat’s life and definitely improve his welfare by giving him the chance to perform a highly motivated species-specific behavior. Not being able to hide can lead to tremendous emotional and physical stress for a cat.

All cats should have enrichment in their daily lives. This is not optional! Enrichment includes core resources such as food, water, litter boxes, resting spots, and hiding spots. Physical activities such as play and hunting for food are also important. Don’t forget training, a great way to add to social and physical activity and also to strengthen the relationship between you and your cat.

Some cats will become social with their human family but will never be comfortable with visitors. Don’t force the issue or let people seek out your cat when he wants to be left alone.

Above all, respect who your cat is. Remember that his personality is molded by genetics, his previous experiences, and learning, much of which we cannot control. But we can allow him to be the cat he is, whether that’s the life of the party, the shy wallflower, or the untouchable. All cats are beautiful and enrich our lives in their own ways.