CHAPTER 7

A Harder Case

Art Byrne of West Hartford, Connecticut, presides daily over his own United Nations. Within the main plant of the Wiremold Company, of which he is president and CEO, are representatives of twenty-four nationalities. A substantial fraction of the workforce is foreign born and 30 percent list a language other than English as their original tongue.

Wiremold’s polyglot workforce produces a set of objects which Art Byrne describes as “splendidly mundane”: wire management systems that route complex combinations of power, voice, and data wiring through buildings, and power protection devices such as surge protectors and line conditioners, which protect sensitive electronic equipment from voltage fluctuations.

Wiremold employees use simple production machinery—plastic injection molding machines, stamping presses, and rolling mills—to make products for mature and highly competitive markets. The workforce is organized by the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, one of the most traditional unions in the United States. The main plant was built in the 1920s and has been expanded over the years by hodgepodge additions of one small annex after another, making continuous flow and transparency difficult to achieve.

In short, Wiremold is the typical instance of “smokestack” America: a “low-tech” product made with “low-tech” tools by a unionized, immigrant, aging workforce with limited skills, working in an ancient facility; the type of firm which has had great difficulty in world competition in the past twenty years.

When Art Byrne arrived in September 1991, Wiremold was in a profound crisis, with declining sales, deteriorating production assets, and practically no profits. Four years later, the company has more than doubled its sales with the same workforce, increased wages, upgraded its physical plant, entered into a permanent growth trajectory, and become outstandingly profitable. How this happened is an object lesson in leaning American industry

.

“We Nearly JITd Ourselves to Death”

In the late 1970s, family-owned Wiremold, which had been a successful manufacturer of wire raceways since 1900, switched from family to professional management and, in the words of Orrie Fiume, its longtime vice president for finance, “asked what we wanted to be when we grew up.” The wire raceway business seemed to have practically no growth potential, so Wiremold decided to enter the surge protector business. These are the ubiquitous devices, generally found on the floor under your desk, which protect your personal computer from the electric company.

The easiest route seemed to be through an acquisition, and after some searching, Brooks Electronics of North Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, was acquired in 1988. Brooks brought with it not only an established market position but also a close acquaintance with W. Edwards Deming. President Gary Brooks had embraced Deming’s Total Quality Management (TQM) in the early 1980s, struck up an acquaintance with Deming, and taken not only his entire management but half of his total workforce to Deming’s weeklong seminars.

When Brooks was acquired, TQM was embraced by Wiremold as well, and the management of Wiremold was soon enrolled in the Deming seminars. As Orrie Fiume notes, “Deming’s Fourteen Points were a perfect fit with our values and we all loved the principles. There was only one problem: Deming teaches what he called the ‘Theory of Management,’ or what I call a philosophy of change. But like a lot of good management theories, it was critically short on implementation details.”

By 1989, Wiremold was ready to try harder at implementation, and sent its vice president for operations to visit Japanese factories. He came back praising the concept of Just-in-Time (JIT) and immediately set about pulling down inventories and reducing lot sizes. What he could not do, because no one knew how, was introduce flow and pull by reducing changeover times for Wiremold’s tools and building to a level schedule.

As Orrie Fiume remembers, “Our customer service went completely

to hell! We soon discovered that our MRP had years earlier had a 50 percent extra margin added to the safety stock calculation. We also discovered that our reliance on enormous batches and mountainous inventories meant not only that we could tolerate slow tool changes but that we could skimp on tool maintenance. If a tool was installed in a machine and found to be defective, there was plenty of time to send it out for maintenance and get it back before we actually ran out of parts. Our tools had deteriorated to a shocking extent without the management ever realizing what was happening.

”

Between 1989 and 1991, Wiremold slid steadily from record profits toward breakeven. Some of the problem was lost sales when Wiremold couldn’t deliver, but total sales went down only a few percent. The real problem was costs, as Wiremold paid express freight, added a whole customer service staff to explain why deliveries would be late, and paid to fix its tools. As Fiume notes wryly, “We nearly JITd ourselves to death by doing it the wrong way.”

By 1991, Wiremold’s longtime president was ready to retire, creating the opportunity to find a chief executive who could actually implement a lean system. As Fiume recalls, “You might think we would have simply gone backward to large batches and massive inventories, but something had permanently switched over in our minds as a result of exposure to Deming and the rudiments of lean thinking. We gave no thought to going back to the old way, but instead set out to find someone who could implement the new way.”

The Change Agent

For Art Byrne, the “light went on” in 1982 when he was general manager of a small business unit, the High Intensity and Quartz Lamp Division, within the vast General Electric Corporation. One of his manufacturing managers had gone on a study trip to Toyota and had come back with amazing stories about inventory reductions due to JIT. Byrne began to read the available literature, then took his own trip, and was soon ready to give JIT a try. In one of the first JIT applications in GE, Byrne and his colleagues were able to reduce in-process inventories in his business unit from forty days down to three. He remembers, “It seemed like a miracle.”

Art Byrne’s problem was not with JIT but with GE. “I hated the ‘make-the-month’ mentality where everything was evaluated on the basis of short-term financial performance, and I became convinced that I would never be allowed to take the more difficult next steps in creating a lean organization. I already knew that when you try to create continuous flow there is going to be a step backward for every two steps forward, and I doubted that GE’s instant-results management culture could deal with it.”

So Byrne left to become a group executive of the Chicago Pneumatic Tool Company, a manufacturer of small air-driven tools for industrial users. However, he had hardly arrived at Chicago Pneumatic in 1986 when it was taken over by the Danaher Corporation (which we heard about in

Chapter 6

), and Art Byrne was soon put in charge of eight Danaher companies

.

The Knowledge

One of the Danaher firms in Byrne’s portfolio was the Jacobs Equipment Company (commonly known as Jake Brake) of Bloomfield, Connecticut. The sales and marketing vice president of this firm was George Koenigsaecker,

1

a particularly eager advocate of lean ideas who had made numerous study trips to Japan, including to Toyota, and read every book and article he could find on lean production.

When he was promoted to president of Jake Brake at the end of 1987, Koenigsaecker and his new operations vice president, Bob Pentland,

2

began moving machinery from process villages, tearing out conveyors (which are really moving warehouses), and setting up their first cells to make truck engine components in single-piece flow. They began to get dramatic results, but neither Koenigsaecker nor Pentland felt they knew as much as they needed to know, and they were constantly looking for ways to learn more.

Early in 1988, Koenigsaecker noticed that a weeklong seminar and kaizen

event on the Toyota Production System was being held at the Hartford Graduate Center and in the plant of a nearby firm. He, Pentland, and Byrne decided to attend. The organizer of the course was Masaaki Imai, then becoming well known for his book, Kaizen.

The other instructors were Yoshiki Iwata, Akira Takenaka, and Chihiro Nakao of the Shingijutsu consulting group in Japan, whom none of the Danaher group had ever heard of.

After the Danaher delegation had listened to the first day of the Shingijutsu presentation on TPS and discovered that they had worked for years as pupils of Taiichi Ohno in his efforts to spread lean thinking through Toyota’s supplier group and beyond, they thought they were on to something. Koenigsaecker approached the instructors about visiting Jake Brake.

As Bob Pentland remembers, “We had never met a Japanese-style teacher, or sensei,

and we weren’t prepared for being turned down cold. Iwata simply said ‘no’ and stalked away. However, George is a uniquely persistent person and kept approaching Iwata, first at lunch, then at the afternoon coffee break, then at the end of the day. Every time he posed the question through Iwata’s translator, the answer was a brusque ‘no.’ The next day George was at it again, before class, at lunch, and during coffee breaks. Finally, at the end of the second day, Iwata and his colleagues agreed to go to dinner, probably so George would stop asking.

“The minute we sat down to dinner, I pulled out a layout of our plant with the new single-piece-flow cell [identical to the Lantech cells described in

Chapter 6

] which we had just created. I laid it on the table in front of Iwata, and asked him whether we were doing the right thing. There was a long, frosty silence. Finally, Iwata said, ‘If I come to your plant, will you do

whatever

I tell you to do?’ George and I said, ‘Of course.’ Iwata responded, ‘If this is true, roll up the drawing, let me eat my dinner in

peace,

and I will come to your plant this evening.’”

When they arrived at the plant around 10:00 P.M.

, the Japanese team took one look at the new cell and pronounced it all “no good.” They explained that among other problems it was laid out backwards (the work should have been flowing counterclockwise) and it would be necessary to move all the machines immediately. Koenigsaecker and Pentland had done no preparation for the visit and they knew their union leaders would be upset about the abrupt changes (which they were), but it was also clear that this was the test: “Would we do immediately exactly what they told us?” So everyone pitched in to reconfigure the cell and by 2:00 A.M.

it was running again, with results far better than before.

With this introduction to the “just-do-it” mind-set of the lean sensei,

Koenigsaecker knew he had entered a new world. “My whole notion of how much improvement was possible in a given period of time was fundamentally and permanently altered. I also realized that these guys could be a gold mine for the Danaher group.”

Koenigsaecker and Pentland assumed that they had passed the critical test and that arranging a consulting relationship would be easy. So they were dismayed when Iwata abruptly headed out of the plant once the cell was running, explaining that he had done what he could but that Jake Brake managers were hopeless “concrete heads” beyond his ability to help further.

Fortuitously, the kaizen

event held during the rest of the week at another Hartford area firm ran into the entrenched resistance of the firm’s management, which refused to do any of the things the sensei

requested. By Friday, the Danaher delegation was ready to ask for help again. This time Iwata responded that Danaher managers seemed to have no idea how to operate their business but that compared with the other American managers he had just met, there was at least some hope. However, he and his colleagues also said they were too old to learn English and that America was too far away.

Art Byrne was determined not to give up and arranged to meet them in Japan a short time later. There, after asking for help a third time, he finally got an agreement for a one-week trial to see if Danaher was truly serious.

The first day of the trial was conducted at the Jacobs Chuck Company, another Danaher subsidiary, in Charleston, South Carolina, which manufactures drill chucks for small electric drills of the type most of us have in our home tool kit and for industrial models as well. Byrne and Jacobs president Dennis Claramunt thought they would start with a one-hour plant tour and go from there. However, after five minutes, Iwata, Takenaka, and Nakao announced they had seen enough. “Everything is no good,” they announced through their translator. “Will you fix it now?”

Two teams were formed immediately, one with Iwata to work on final

assembly and the other with Takenaka and Nakao to work on machining the steel bodies for Jacobs’s industrial drill chucks. Byrne and Claramunt followed Iwata but were soon interrupted by Jacobs’s manufacturing engineers, who were upset that Takenaka and Nakao were demanding to move all of the heavy machinery used for machining the chucks during the lunch hour.

Claramunt told the engineers to let Takenaka and Nakao do whatever they wanted and then went to the machining area with Byrne after lunch to see what was happening. With their sleeves rolled up and pry bars in hand, Takenaka and Nakao were working furiously to move the massive machines out of their departments and into the proper sequence for single-piece flow while Jacobs engineers and the rest of the workforce stood with their mouths hanging open.

On one level it was pure theater; the Japanese visitors surely understood what an extraordinary scene they were causing. But on another level, they were prying Jacobs loose from their bureaucratic, departmentalized, batch-and-queue past. As Byrne remembers, “By moving those machines themselves in only a few minutes—when many hadn’t been moved in years and Jacobs executives would never have dreamed of touching any machinery themselves—they demonstrated how to create flow and what a few determined individuals can do. Neither Dennis nor the rest of the Jacobs work-force was ever the same again. They all threw away their reservations and got to work.”

So Danaher passed the test and Japanese advisers agreed to work intensively for Danaher as their exclusive North American client. “With our sensei

on board and with the full backing of the Rales brothers as they began to grasp these ideas in mid-1989, we had the knowledge and the authority to push lean thinking faster and faster.”

By 1991, Art Byrne had introduced lean thinking all the way across the eight companies in his group, with spectacular results. He was also instrumental in spreading lean thinking in the five other Danaher companies, led by John Cosentino, who became a true believer. The transmission device was Byrne’s innovation of the “presidents’ kaizen”

in which the presidents of all of the Danaher companies and their operations vice presidents were required to participate hands-on every six weeks in a three-day kaizen

event in a Danaher plant. They moved machines themselves and in many cases learned the realities of the shop floor and the ordering and scheduling system for the first time. (One of these companies was Hennessy Industries, where Ron Hicks, whom we met in the last chapter, made the transition from “concrete head” to lean thinker through his experiences in presidents’ kaizen.

)

However, Byrne was growing restless. Like most change agents, he wanted to run his own show, but the top jobs at family-controlled Danaher

were unavailable. Wiremold, on the other side of Hartford, had heard about Byrne’s work at Danaher, and a match was made.

The Leaning of Wiremold

When Art Byrne arrived at Wiremold in September 1991, he found about what he expected, a classic batch-and-queue system in production operations, order-taking, and product development. Products took four to six weeks to go from raw materials to finished goods. Orders took up to a week to process. New products, even when they were nothing more than a reshuffling of existing parts, required two and a half to three years to progress from concept to launch. As a result, only two or three new products were being launched each year. Thick departmental and functional walls were everywhere, damming up the flow of value and making it impossible to see.

Byrne quickly realized that by applying lean techniques he could run the company at its current sales volume with half the people and half the floor space. Given the financial situation, he had to take immediate action. So, as his first step, he tackled the excess-people problem.

Dealing Up Front with Extra People and Anchor-Draggers

In November 1991, Art Byrne announced that the crew was too large to keep the ship afloat and offered a generous early retirement package to the aging workforce in the plants and to the office staff. Although he believed that only half the workforce was needed, he set the headcount reduction goal at 30 percent, knowing that as soon as he got the product development system working right, sales growth would absorb the remaining excess people.

Almost all of the eligible hourly workers took the retirement offer, but only a small fraction of the office staff accepted. Art and Judy Seyler, his vice president for human resources, therefore conducted a “de-layering.” They classified every job in management as either:

• value creating (defined as the ability of Wiremold to pass the costs of the job along to the customer),

• nonvalue creating (from the standpoint of the customer) but currently necessary to run the business (for example, the environmental expert helping the company meet government regulations, Type One

muda

), or

• nonvalue creating and unnecessary (Type Two

muda

)

They then classified each manager as either:

• able to create value,

• able to create value with some development of skills, or

• unable to create value, even with development (usually due to unwillingness to change their attitudes about the organization of work)

After years of creating lean organizations, Art had concluded that about 10 percent of existing management will not embrace the new system. “Lean thinking is profoundly corrosive of hierarchy and some people just don’t seem to be able to make the adjustment. It’s essential that these anchor-draggers find some other place to work—after all, there’s still plenty of hierarchy out in the world—or the whole campaign will fail.”

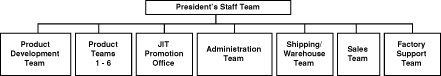

The people in the first two categories were therefore matched up with jobs in the first two categories to create a new organization structure (com-pare

Figure 7.1

with 7.2) with a new roster of players. Employees not finding useful jobs were given a generous severance and within thirty days of Art’s arrival the new structure and player roster was in place. Only one outsider was recruited, Frank Giannattasio, the new vice president for operations.

F

IGURE

7.1: O

LD

W

IREMOLD

O

RGANIZATION

As Judy Seyler looks back on this event, she notes

that it was terribly traumatic in a hierarchical, paternalistic organization in which no one had ever been asked to leave. “Even though the financial cost was very large,

particularly given our lack of profits, Art was determined to be generous with people while making it clear that in the future everyone must create value by working together in a different way.”

F

IGURE

7.2: N

EW

W

IREMOLD

O

RGANIZATION

When the headcount reductions were completed, Art Byrne called a meeting of the entire workforce of the parent company and announced that no one would ever lose their job as a result of the improvement activities that would start immediately. “The bad part is over; now we will all learn how to continuously create more value so that we never have bad days again.”

Byrne was in effect giving job guarantees to his union workforce without asking anything in return except that they be open-minded to change. “I’m certain that 99 percent of American companies wouldn’t do this, but taking away the fear of job loss is at the very core of a lean conversion. Think of it logically from a human perspective rather than as some corporate bureaucrat. If I asked you to help me reduce the number of people needed to make a particular product from five down to two, and after you did, I followed up by laying off three people, one of whom was your cousin and another a good friend, what would you say to me when I asked you to help me do the same thing a month later for another product?”

Teaching People How to See

Based on his experience in “leaning” eight separate businesses in the Danaher group, Byrne had concluded that the single most effective action in converting an organization to lean practices is for the CEO to lead the initial improvement activities himself. “This is where most American companies fail right at the outset. CEOs want to delegate improvement activities, partly because they are timid about going out on the shop floor or to the engineering area or to the order-taking and scheduling departments to work hands-on making improvements. As a result, they never really learn anything about change at the level where value is really created. They continue to manage in their old by-the-numbers manner, which kills the

improvement activities they thought they started. The fact is that big changes require leaps of faith in which the CEO must say ‘Just do it,’ even when ‘it’ seems contrary to common sense. If the CEO spends time in real operations learning just how bad things really are and begins to see the vast potential for improvements, he or she will make the right decision more often.”

Because no one else in the company understood lean principles, Art Byrne led the initial training sessions himself. Using a manual he had written, he conducted two-day sessions on lean principles for 150 employees followed immediately by three-day kaizen

exercises so employees could use the skills they had just learned. (This was very different from Wiremold’s previous improvement activities, conducted as part of TQM, where improvement teams met weekly for an hour or two, mostly to plan improvements to be implemented weeks or months later.)

Byrne then gathered his managers and union head together and took them on “the walk of shame” through every part of the plant and through the engineering and sales departments. “There was muda

everywhere and my managers were now able to see it. I told them that we were going to convert every process, including product development and order-taking, into continuous flow and that we were going to learn how to pull. I also told them that I was going to get them the best help in the world, from Iwata and Nakao, who were at the end of their exclusive agreement with Danaher and ready to work for Wiremold.”

Attacking Every Value Stream Repeatedly

Soon hundreds of weeklong kaizen

activities were under way (and continue to this day), involving practically every employee, as every value stream in Wiremold was repeatedly evaluated for ways to make it flow better and pull more smoothly. Wiremold’s assumption is that every stream can always be improved in pursuit of perfection and that every stream must be improved in pursuit of perfection. Equally important, it is presumed that results can be achieved very quickly, the common expression being that “if you can’t get a major improvement in three days you are doing something wrong.” Once this mentality is reinforced by results—and employees begin to believe management’s guarantee that no job will ever be lost due to improvement activities—improvement can become self-sustaining

.

Re-creating the Production Organization to Channel the Value Stream

When Art Byrne de-layered the Wiremold organization (again, see

Figure 7.2

) he did far more than remove tangential jobs and frills that could no longer be afforded. He smashed the departmental barriers to focus every-one’s efforts on the value stream by creating dedicated production teams for each of Wiremold’s six product families. The purchasing, manufacturing, and scheduling (MRP) groups within the Operations Department, the Engineering Department, and the “process villages” (stamping, rolling, molding, painting, assembly, etcetera) in the plants were eliminated, with their personnel reassigned to product teams provided with all of the resources needed to produce a specific product family.

Let’s take Tele-Power[H23008] Poles as an example. (These are the steel or aluminum columns extending from floor to ceiling in open office settings, with power and communications outlets on every side of the column to permit a host of adjacent workstations to plug in. They are offered in an enormous variety of shapes, lengths, plug configurations, and colors.) Team leader Joe Condeco was given complete responsibility, and profit-and-loss accountability, for Wiremold’s “pole” products from initial launch through their production life. More radically, the team leader, the product planners, the buyers, the factory engineers, the production supervisors, and the production associates were all co-located on the factory floor immediately adjacent to the realigned machinery producing the poles in single-piece-flow cells.

The team was given its own punch presses and rolling mills, as well as assembly equipment, so it could be self-sufficient. Before, the assembly activity was dependent on the Rolling Mill Department for their bases and covers. Despite large stocks on hand, they would often lack the right base or enough covers. When they asked the Rolling Mill Department for more of a missing item, the response would often be, “Sorry, but the master schedule generated by the MRP system calls for us to make other items now. You’ll have to wait until next week or take your problem to a higher level.” Now the Tele-Power[H23008] team has all of the equipment it needs. There can be no excuses.

The new setting was initially a great shock to the “white collars” who had always worked in a remote office and seen themselves in a very different light from “factory workers.” (Wiremold soon implemented a casual dress code based on Art Byrne’s belief that “neckties cut off circulation to the brain and inhibit teamwork.” This was another problem for office workers who somehow felt that their appearance rather than their skills and their

contributions made them special.) Reassignment to product teams was also a shock to the process specialists working in the process villages like the Rolling Mill Department who had traditionally hoarded their tricks of the trade. However, everyone soon came to like it. For the first time, they could actually see value flowing!

Introducing a Lean Financial System and “Scoreboard”

To get the production teams to work in accordance with lean principles, Wiremold needed to junk its traditional system of standard cost “absorption” accounting, which allocated costs by labor and machine hours in accordance with mass-production thinking. Production managers knew from experience that they had to “absorb” allocated overhead by spreading it over as many machine and labor hours as possible. This system gave an overwhelming incentive to keep every worker and every machine busy—to “make the numbers”—by producing inventory, even if the inventory consisted of items no one would ever want.

As Orrie Fiume remembers, “Standard cost and variance analysis were declared dead as concepts immediately after Art’s arrival. We looked at Activity Based Costing but knew it wasn’t the answer. Its advocates will tell you it is based on cost drivers, but in reality it’s just a different method of allocating overhead. There is still too much allocation of aggregated costs downward. We were determined to work from the bottom up.”

The key to the new way of thinking was to organize production by product families, then let each product team do its own purchasing and buy all its own tools. A simple system could then be devised to assign real costs to each product line. Today, more than 90 percent of the costs involved in making a Tele-Power[H23008] pole, for example, come from product-specific cost analysis. Only a small fraction of cost is an allocation outside the control of the team, specifically occupancy costs for whatever space the team is using in a plant. And even in this case, the team is charged only for the space it actually uses, so costs can be reduced by using less.

Some elements of the old standard cost accounting system are retained in the computer because the financial statement needs them—for example, the value of in-process inventories. However, these are deemphasized in evaluating the performance of the product teams, which are told to concentrate on the cost of manufacturing instead. Similarly, the financial implications of running down the inventories during the transition period were not shown to the product team leaders for fear they would do the wrong thing.

3

In addition to a simple profit-and-loss calculation, Wiremold’s production

teams were given a new “scoreboard” consisting of some simple, quantitative performance indicators:

• productivity of the product team (expressed as sales per employee),

• customer service (expressed as percent of products delivered on time),

• inventory turns, and

• quality (expressed as the number of mistakes made by the team)

The team leaders and their teams can see these indicators at all times because they are prominently posted. In addition, the two primary ways to improve are obvious. First, smooth the flow of products through the system, with no backflows for reworking quality problems, no scrap, and no in-process inventories. Then, make only those products customers actually want, because productivity is measured as end-market sales (not additions to in-process inventories) per employee.

To keep everyone marching at the same pace, Wiremold equips the scoreboard with a set of expectations as well. Specifically, team leaders and their teams are expected to:

• reduce defects, as shown in the quality indicator, by 50 percent every year;

• improve productivity, expressed as sales per employee in constant dollars, by 20 percent every year;

• deliver 100 percent of products

exactly

on time;

• increase inventory turns to a minimum of twenty per year; and

• increase profit sharing to 20 percent of straight wages (as explained in a moment)

“Variance analysis” is still performed but not based on variances from standard costs. Instead, when the trend line starts to diverge from performance targets, the team collectively searches for the root cause of the variance rather than maneuvering to “make the numbers,” as in the old days.

Running Down Inventories

Because Wiremold is privately held and the board of directors understood what was happening, the special financial problem of inventory reduction in a lean transition was not a major concern. For a publicly traded company, however, rapidly running down inventories can be a real problem, one worth a brief digression. As firms move from batch-and-queue to flow systems,

enormous amounts of cash are suddenly made available from freed-up inventories. (This offers the firm a special strategic opportunity, as we will see in a moment.) The problem is that the removal of these inventories increases production costs, as shown on the financial statement,

and can easily wipe out profits.

Let’s take a simple example. Firms typically calculate their costs of production and profits in the following manner, as shown in the left-hand column of

Table 7.1

.

T

ABLE

7.1: C

ONSEQUENCES OF

I

NVENTORY

R

EDUCTIONS FOR

P

ROFITABILITY

Now, suppose that the new “lean” management takes in-process inventory down dramatically from $576,000 to $100,000 while holding everything else constant (except, of course, material purchasing, because products are being made largely from the inventories already on hand). Running the numbers again, as shown in the right-hand column, it’s apparent that the new management, while trying to “do the right thing,” has moved the company from a $153,000 profit to a $36,000 loss (even as cash flow has zoomed).

This phenomenon can be very bad for publicly traded companies unless the management actively explains the situation to stockholders in advance. The only alternative to education is a slash-and-burn campaign of head-count and cost reduction (in the direct labor and indirect manufacturing cost accounts) to restore short-term profits. This can, however, easily set back the introduction of lean thinking or even make it impossible if the traumatized workforce refuses to cooperate with lean initiatives

.

Creating a “Lean” Function

To help the product teams continuously improve, Art Byrne created a new function, the JIT Promotion Office (JPO). The old Quality Department, some of the training activities formerly conducted by the Personnel Department, and several high-potential associates from different areas of the firm were grouped under the JPO. With the JPO, the task of working through the entirety of Wiremold, value stream by value stream, could be speeded up.

The product team leader and the JIT Promotion Office jointly evaluate the value stream for the product to determine what types of kaikaku

and kaizen

activities should be performed and when. A team leader from the product team and a facilitator from the JPO are then assigned to each improvement team (which might be a subset of the product team, the whole team, or some portion of the team plus outside experts with needed skills). Because the team leader will go back to her or his job on the product team once the kaizen

is finished, the facilitator from the JPO shoulders the critical responsibility for seeing to the completion of the follow-up work invariably resulting from a weeklong improvement effort.

In addition to planning and facilitating improvement exercises, the JPO teaches every employee the principles of lean thinking (identifying the value stream, flow, pull, and the endless pursuit of perfection) plus lean techniques (standard work, takt

time, visual control, pull scheduling, and single-piece flow in particular) and periodically reteaches them. As Frank Giannattasio notes, “This is an enormous but critical challenge. Your middle management, in particular, feels threatened by the lean transition and the removal of all those safety nets. When in doubt, they will take you right back to making batches and building inventories unless you reinforce the message through continued teaching, coupled with continuous hands-on improvement exercises.”

Offering Ironclad Job Guarantees in Return for Flexibility

As we noted earlier, Art Byrne knew that if the value stream for every product was going to be unkinked continuously, people would continually be left by the side of the stream. Resistance to continuous improvement would be chronic unless he guaranteed that workers would not be out on the street, even if their specific job was eliminated. He also knew that the existing work rules in Wiremold’s union contract—restricting stampers to stamping, painters to painting, molders to molding, and so on—would make

it impossible to introduce flow and to continuously improve every activity. Finally, he knew that his workforce would have a very hard time differentiating layoffs due to weak demand from layoffs due to kaizen.

Therefore, once the initial retirement offer was accepted, Art went immediately to his union and offered job guarantees for the remaining workers in return for their cooperation in working in a new way.

The union was suspicious at first. Wiremold’s former director of labor relations had been an old-fashioned hard-liner and the union presumed that any management offer of job guarantees must contain fine print which somehow reversed its on-the-surface meaning. In the end, however, the union decided that Byrne would deliver on his promises.

Curiously, for reasons Art Byrne finds hard to understand, executives in many companies in the Hartford area were more skeptical about his job guarantee offer than his union. “People tell me all the time that I’m crazy to make an ironclad guarantee of jobs. They say, ‘What if something goes wrong and your sales fall off?’ But my view is that management has five lines of defense before showing people the door: (1) reduce overtime, (2) put the extra people on kaizens

(to get a future payback), (3) in-source some components from marginal suppliers we plan to drop anyway (remembering that our equipment is now highly flexible), (4) cut the workweek across the board, and, most powerful, (5) develop new product lines to grow the business. Our employees are now all highly skilled in process improvements and only a concrete head would fire skilled people due to short-term business fluctuations.”

Re-creating the Product Development System to Channel the Value Stream

The product development system Art Byrne found in the fall of 1991 was clearly not going to grow the business. Engineering vice president Steve Maynard remembers that thirty products were under development and all were making slow progress. “We had long queues between the stages in development, we had departments within engineering with batch production, and we had expediters. There were absolutely no priorities except that some projects at some times had ‘the voice of the president’ behind them and received expeditious treatment.” The average project actually making it through the system took three years, but many stragglers were lost in action along the way.

Fortunately, Steve Maynard already knew what to do. He had learned, at a University of Hartford seminar in the fall of 1990, that Quality Function Deployment and dedicated development teams are an unbeatable combination. The seminar was affiliated with MIT’s Laboratory for Manufacturing

and Productivity, and MIT professor Don Clausing, one of the disseminators of the “House of Quality” concept,

4

took Steve through the steps needed to introduce the “voice of the customer” in a highly structured, continuous-flow development process.

However, back at Wiremold, the senior management was so busy with the ongoing TQM effort that there was no time for another program. They told Steve Maynard, “Wait until next year.” Fortunately, by “next year” Art Byrne was on the scene. “When I first met Art, I said, ‘What do you think about QFD and dedicated development teams?’ He said, ‘Do both immediately. And by the way, your new target for product development time is now three to six months, not three years.’ We were off and running within a week.”

Steve Maynard’s first step in the fall of 1991 was to start formal in-house training in QFD, using a consultant for technical support.

5

All the senior executives attended this training, just as every manager, no matter how senior, no matter what their job, participated in shop-floor

kaizen

activities. Art Byrne’s theory was that every manager in an organization must understand the basic activities of that organization, notably product development, production operations, and sales/scheduling, and that the only way to learn was intense exposure to systematic principles.

Next, Maynard and the senior management team asked an obvious but previously neglected question: What businesses are we really in? They reviewed the thirty ongoing development programs and “deselected” those—most of them, in fact—which did not support a specific business: tele-power, power and data management, plastic products, etcetera.

6

This shrunk the number of projects dramatically, and those which remained were prioritized. These projects were then placed in a product plan, showing their target dates for introduction.

For each program judged worthy of continuing, Maynard designated a three-person team consisting of a marketer, a designer/product engineer, and a production/tool engineer. The team was sent to talk directly with prospective customers in the building design and construction community to come up with a broad definition of the product through an initial QFD process. They asked the “value question” described in

Chapter 1

and came back saying, for example, “What we really need is a Tele-Power[H23008] Pole which can accommodate any height of ceiling, which can be ordered in a very wide range of colors, and which is unobtrusive.”

Steve Maynard remembers the amazement among many Wiremold old-timers when these teams were formed. “They asked me, ‘Why have we got a tool-design guy out in the field talking to customers? Doesn’t the need for specialization and the division of labor require that tool designers stick to designing tools?’ The security many of them felt in the old

departmentalized,

everything-in-its-place way of organizing work was truly striking.”

Once the broad definition of the surviving products was determined, a truly multifunctional team was formed to develop a detailed product specification in engineering language. The team was co-located in a dedicated space in the Engineering Department and included the team leader from the appropriate product family (Tele-Power[H23008] Poles in our example) plus the production planner, the production/tool engineer (a member of the original three-person, product-definition team), and a buyer. The team was told to achieve a target cost determined by estimating the market price and subtracting an acceptable margin.

When the precise specification of the product was accepted, detailed part and tool design was conducted by the team, again working to target cost. Toward the end of the process, the whole team moved its desks to the factory floor to go through process-at-a-glance and standard work exercises with the production team handling the product. (Remember that thinking about manufacturability has been present from the beginning. The production/tool engineer was on the original definition team.)

By mid-1992, Wiremold was ready with its first product under the new regime. It had taken only six months and tool costs were only 60 percent of what had been originally budgeted, based on past experience. Even as Wiremold’s managers in the physical production and order-taking process were learning how to see, Wiremold’s marketers, product designers, and engineers were learning how to hear the voice of the customer and how to make designs flow quickly and directly through the development process.

7

Fixing the Order-Taking Process

The third key activity of any business is order-taking, scheduling, and delivery, and Art Byrne made no distinction between this “business process” and the firm’s physical production. It was subjected to the exact same kaikaku

and kaizen

process at the same level of frequency as every production activity.

As in most batch production organizations, Wiremold’s order entry and shipping was disconnected from physical production. A master schedule in the MRP system, based on market forecasts, was supposed to ensure that adequate stocks of finished goods were always on hand in a massive centralized warehouse, so that when an order was received it could be processed and then shipped from inventory.

The orders themselves were also processed in a batch mode through a central Customer Service Department. This department entered orders throughout the day into a computerized order-processing system. The

orders

were processed overnight in a batch and, if inventory was on hand, pick lists of what to ship were printed out the next morning in the Shipping Department. Over the next two or three days the Shipping Department at the warehouse would gather the goods and send them to Wiremold’s distributors.

However, items on a customer order often were not available, despite large inventories, so very few orders were shipped complete. Instead “backordered” items were shipped over an extended period as they became available. Because of the MRP system and the large batches in each production run, it was not unusual for a single customer order to ship over many weeks or months. Also, because most orders had delayed items, a large Customer Service Department was needed to keep track of orders and to respond to customer questions about delayed items.

The end result of all this handing off of orders and the massive warehouse was that it took almost a week to process and ship an order when everything was in stock. Yet most orders called for items which were delayed for extended periods and the system had many potential sources of errors. The Customer Service Department found it very difficult to keep up with its dual role of making customers happy about delayed or incorrect shipments and spurring the rest of Wiremold to get the job done right.

After a series of kaizen

teams went through the entire series of activities—from order-taking to shipping—it was possible to shorten the order-receipt-to-ship time from more than a week to less than a day. To achieve this, orders were sent to shipping four times during the day (rather than in one big batch overnight) and the central warehouse was closed, freeing up 70,000 square feet of space. Upon receipt of the orders, shipping circulated carts past the small finished stock racks at the end of each product team’s production process.

As the shipper withdrew parts from the rack and pushed empty parts containers down a return chute, this became the signal—the only signal—for the product team to make more of a given part. (The MRP system which formerly kept track of the movements of individual parts within the Wiremold production system was gradually given the much smaller task of long-term capacity planning and ordering parts from suppliers not yet on pull systems.)

This new approach, which required many fewer people and resulted in fewer errors, could only be introduced over a period of about two years as Wiremold began to convert from batches to product teams with single-piece flow. Parts which had been produced in one-month batches were soon being produced every day, a feat which required that many machines be changed over twenty to thirty times per day rather than the former three to four times per week

.

Although Wiremold’s competitors in the electrical industry are now being forced to match its quick-shipping capability, they seem to be doing it the way so many American firms are achieving “just-in-time,” by maintaining even larger inventories of finished units or by switching to a “Max-Flex” system such as we saw at Lantech, in which mountains of component parts are prepared in advance so that final assembly can be conducted in direct response to customer orders. Both approaches are inferior to a truly lean pull system from start to finish.

Linking Compensation to Profits

Wiremold had always paid base wages at slightly above the average level for the Hartford area. It then tried to reward its workers for good results through a profit-sharing plan funded with 15 percent of pretax profits, paid quarterly in the form of a check, and by contributing shares of company stock as the employer contribution to a savings plan. The problem was that, in the years just prior to Art Byrne’s arrival, there had hardly been any profits and stock values had slumped. In addition, the old batch production system made it hard for employees to see any connection between their own efforts and the success of the firm.

Art Byrne resolved to keep the existing profit-sharing arrangement but to steadily increase profits (“by working smarter than our competitors”) and to show everyone the financials so that the reasons for profitability would be clear. During the first years of “lean management,” profits at Wiremold have increased from 1.2 percent of wages in 1990 to 7.8 percent in 1995, and Byrne is still strongly committed to increasing profit sharing to 20 percent of every employee’s pay.

Improving Suppliers

After many internal improvements were made, it became increasingly apparent that many of Wiremold’s problems were external. Purchased goods and raw materials accounted for a significant percentage of Wiremold’s total costs, yet no effort had ever been made to improve supplier performance. Instead, Wiremold’s traditional purchasing operation had concentrated on controlling supplier profit margins by ordering every part and type of material competitively from multiple sources.

Kaizen

teams moved quickly to dramatically reduce the number of suppliers, from more than 320 in 1991 to 73 by the end of 1995. This was essential

if Wiremold was going to be able to take time with each supplier to improve its performance. But then it was necessary to start with the most critical suppliers and teach them to see.

In April 1992, a Wiremold kaizen

team paid a first visit to Ryerson, a giant steel fabricator much larger than Wiremold, with fabrication facilities spread all across North America. Ryerson supplies Wiremold with large rolls of steel which Wiremold stamps or bends to make the cases for many of its products. Ryerson had adopted state-of-the-art techniques to the extent that it had just begun to deliver to Wiremold every day, “just-in-time.” However, at the back of Ryerson’s plant, the Wiremold JIT team found just what they had expected: a neat row of steel coils, each a day’s supply for Wiremold, fifty days in a row produced by Ryerson in one enormous batch. Just-in-time had been nothing more than an inventory shuffling exercise because Ryerson didn’t know how to produce in small lots.

The Wiremold team therefore went to work on Ryerson’s massive steel cutting machines, which took two shifts to change over from one cutting pattern to the next. This, of course, was the cause of the massive lot of coils laid out in the shipping area. In a short time it was possible to bring changeover times down from two shifts to about thirty minutes, and Ryerson began to meet Wiremold’s needs each day for delivery during the day.

Even better, from both Ryerson and Wiremold’s standpoint, Ryerson was soon able to produce for all of its other customers on a true “Just-in-Time” basis, driving down costs across the board. Wiremold, of course, expected something from Ryerson in return for its trouble, and negotiated a range of special services—like absorption of materials cost increases for extended periods and extra-short runs of steel for certain low-volume applications. As a result of Wiremold’s proactive stance toward a key supplier, Wiremold, Ryerson, and all of Ryerson’s other customers were much better off, a win-win-win achievement for lean thinking.

Devising a Growth Strategy

Art Byrne notes that “our production system and its needs are fundamental to our strategy.” Because the application of lean thinking to batch-and-queue organizations liberates tremendous amounts of resources—people (including engineers and managers), space, tools, time (to get to market much faster), and cash

—it is both possible and necessary to grow rapidly. It is possible to grow rapidly because the means are self-generated; it is necessary to grow rapidly to provide work to support the job guarantees which are the social basis of the system. In consequence, Wiremold has grown rapidly along three tracks

.

One important means of growth for a lean organization is to rethink what can be done in continuous flow. We believe that many organizations try to do too much—in particular, to control suppliers of “key” technologies. But many organizations, like Wiremold before Art Byrne arrived, also do too little in the way of physical production because they imagine that scale economies require the purchase of many items from firms using enormous, high-volume machines in centralized plants to supply these items in massive batches to many customers.

Cord sets are a nice example. Wiremold products use enormous numbers of cord sets—the wire and plug ends used to connect surge protectors and other power conditioning devices to a power source. In the past, these were produced in large batches by cord set manufacturers supplying many firms like Wiremold across a range of industries. The problem was that Wire-mold’s production was constantly being jeopardized by the lack of the proper cord sets as sales trends changed. Wiremold would have brown when only white cords were wanted or have twelve-foot cords when the customer wanted fifteen-foot cords. Resolving these shortages often took two to four weeks due to the batch production methods of cord set suppliers.

When Byrne arrived at Wiremold he asked, “Why can’t we produce cord sets, indeed at the same rate and in continuous flow with our end product?” And, as is usually the case, when Wiremold’s tool engineers looked at the economics of cord set production, they found that the cost and time savings from using small, simple machines merged into the production sequence for the finished product not only overcame the problem of having the right cord set on hand as demand shifted, but also reduced the cost per cord set. So, Wiremold has begun to supply its cord set needs in-house. After all, Wiremold has plenty of excess space, plenty of extra people, and cash readily available to buy or make the necessary, simple machines.

Any would-be lean producer needs to look at this issue more generally, asking in each case, “What physical activities can we incorporate directly into a single-piece-flow production process?” Doing this also reduces the number of suppliers dramatically, making improvement of the remaining suppliers much easier.

Wiremold’s second growth strategy has been to buy up small firms with allied product lines (and who use batch-and-queue methods) in order to increase the scope of Wiremold’s product offerings. The first wave of inventory reductions at Wiremold (during the first two years of comprehensive kaizen

activities) produced $11 million in cash. This money was used to buy five firms with complementary product lines generating $24 million in sales volume.

In essence, Wiremold was able to convert $11 million of muda

(in the form of inventory), which would have cost about $1.1 million in carrying costs (assuming 10 percent as the cost of money and storage), into $24

million in new sales volume, which at a 10 percent operating margin generates $2.4 million in income. The $3.5 million income swing is highly significant for a company the size of Wiremold (with about $250 million in annual sales). Equally important, because the product lines of the five firms were complements to existing lines, Wiremold’s sales force suddenly had a much more complete range to offer customers, which helps increase the overall growth rate.

The fact that Wiremold freed up approximately 50 percent of the space in all of its operations (excepting the central warehouse, which was totally eliminated) greatly helped the acquisition campaign. While Art Byrne’s philosophy is to retain and upgrade existing management, several of the companies purchased were available because the family management could no longer run them successfully and wanted out. This provided consolidation opportunities.

For example, two of the firms purchased were consolidated into Wire-mold’s Brooks Electronics operation in Philadelphia. Prior to the acquisitions, the three companies had operated independently, utilizing 114,000 square feet of space. Now, the combined operation has increased its total sales significantly, yet is located in Brooks’s original 42,000 square feet of space. Inventory has been reduced by 67 percent, the number of employees needed to run the combined operation has been reduced by 30 percent, and the surplus buildings have been sold.

In effect, Art Byrne and Wiremold are running a lean vacuum cleaner across the world of batch-and-queue thinking in the wire management industry. Each time Wiremold’s vacuum sucks up a batch-and-queue producer it spits out enough cash to buy the next batch-and-queue producer! Because of Wiremold’s need to grow to utilize freed-up resources, this process can and must be repeated indefinitely. (As we will show in

Chapter 11

, the first firm to adopt lean thinking in any industry can and must perform this same feat.)

The third and final element of the Wiremold growth strategy is the rapid introduction of new products, utilizing the new product development system with its dedicated teams and Quality Function Deployment methods described earlier. For example, the new product line described in

Chapter 1

has increased sales by 140 percent, both by creating a new niche in the market and by stealing sales from competitors unprepared to match Wire-mold’s pace of product introduction.

All three strategies are critically dependent on the lean techniques introduced in production, order-taking, and product development. Indeed, the rapid introduction of these techniques is

Wiremold’s fundamental strategy. Art Byrne remembers that in previous jobs he had often wanted to go faster with application of these techniques but his senior bosses were usually more

interested in massive long-range “strategic” planning efforts which they believed should take precedence. “To my way of thinking, this is exactly backwards. Introducing lean techniques in every business activity should be the core of any company’s strategy. These provide both the opportunity and the resources to generate and sustain profitable growth. Profitable growth is what the strategic planners of the world are always seeking, but find hard to achieve because their company’s operations can’t deliver on their strategies.”

The Box Score After Five Years

As we will see in

Chapter 11

, three years is about the minimum time required to put the rudiments of a lean system fully in place and two more years may be required to teach enough employees to see so that the system becomes self-sustaining. Wiremold’s performance over the five-year period from the end of 1990 to the end of 1995 is therefore a good test of the potential of lean thinking. The results are quite striking.

To begin with product development, time-to-market has been consistently reduced 75 percent, from twenty-four to thirty months down to six to nine months. Sixteen to eighteen new products are being introduced each year (compared with two to three in the period through 1991), but the engineering/design headcount has stayed the same.

Several new computer-aided design technologies might be assigned some of the credit for these gains, except that these techniques were adopted in 1990–91, before

the time-to-market and productivity gains. As we have emphasized throughout this volume, advances in hard technologies can be useful and in many cases are very important, but they are unlikely to yield more than a fraction of their potential unless they are incorporated in an organization which can make full use of them. By placing product designs in single-piece flow with a dedicated, multiskilled, co-located team and no interruptions, Wiremold has eliminated backflows and rework in the development process while also reducing manufacturing costs and dramatically spurring sales with products which accurately address customer needs.

The rethinking of order-taking, scheduling, and shipping has produced the same results. The old batch system, which needed more than a week to receive, process, and ship a typical order, now needs less than a day. Past-due orders are now less than one tenth of their 1991 level and continue to fall as Wiremold refines its pull system through all six product teams. Order entry errors have been practically eliminated, and misrouted or unanswered queries in the much smaller Customer Service Department have fallen from 10 percent to less than 1 percent

.

In physical production, the results are exactly as we would expect. The amount of plant space needed to produce a given volume of product has been cut by 50 percent and productivity has been increasing at a rate of 20 percent per year. The time for raw materials and components to travel from the receiving dock to the shipping dock in Wiremold’s plants shrank from four to six weeks to one to two days. Inventory turns have increased from 3.4 in 1990 to 15.0 in 1995.

To make this possible, Wiremold has continued to reduce setup times on all of its machines and to convert all production activities for its product families to single-piece flow. For example, punch presses with large progressive dies that used to take two to three hours to change are now changed in one to five minutes; rolling mills which took eight to sixteen hours to change over in 1991 can now be changed in seven to thirty-five minutes; plastic injection molding machines that took two to four hours to change over in 1991 can now be done manually by one Wiremold employee in two to four minutes. As a result, machines that previously shifted from one product to the next two to four times per week, now change products twenty to thirty times a day.

By aggressively implementing single-piece flow, operations requiring five to eight operators in 1991 are conducted with one to three employees today. By utilizing single-piece flow, JIT, and Total Productive Maintenance in the largest and most complicated assembly operations, productivity has been increased by 160 percent over three years. Equally important, single-piece flow has been instrumental in reducing defects by 42 percent in 1993, another 48 percent in 1994, and another 43 percent in 1995, almost at Wiremold’s target rate of 50 percent per year indefinitely. At the same time, standard work, takt

time, and visual control have been slashing accidents and injuries, which are down by more than half compared with 1991.

Putting the improvements in product development, order-taking, and physical production together, we find that sales per employee more than doubled, from $90,000 in 1990 to $190,000 in 1995. However, this and the figures just cited are all relative to Wiremold’s previous performance. The indicators which truly count in the marketplace are sales, profits, and market share. Happily, between 1990 and 1995, Wiremold’s sales in its core wire management businesses—owned before the lean vacuum cleaner was turned on—more than doubled in an otherwise stagnant electrical equipment market and profits of the whole firm—including the new businesses—increased by a factor of six. What’s more, the growth rate, including acquisitions of related businesses, is picking up, in line with Wiremold’s strategy of doubling its sales every three to five years for the foreseeable future.

All of these indicators are summarized in

Figure 7.2

, a “box score” for Wiremold under lean management

.

T

ABLE

7.2: W

IREMOLD

U

NDER

L

EAN

M

ANAGEMENT

But What About Firms with More Severe Problems?

The Wiremold story is extraordinary. The firm has been transformed in a remarkably short time and now gives every prospect of growing rapidly into an industrial giant. What’s more, we could repeat this story in dozens of medium-sized firms we have discovered across the United States during research for this book.

Wiremold was a greater challenge than Lantech, given the age and narrow skills of its workforce, the stagnation of its core market, and the entrenched us-versus-them mentality of the old management and union, but is it still a fair test of lean thinking? After all, Wiremold has only fourteen hundred employees, operates primarily in two neighboring countries (the United States and Canada), and has relatively simple product and process technologies. What about the aging industrial giants who present the most visible managerial challenges? What about the publicly traded, mass-production firm with tens of thousands of employees, global operations, complex technologies housed in deep technical functions, and a complex network of component systems suppliers? Can lean techniques produce the same results, and in the same time frame? We turn now to Pratt & Whitney, which is truly the acid test of lean thinking.