Gilled Mushrooms

Some of the most difficult mushrooms to identify accurately are gilled mushrooms, or agarics. There are more than two thousand species of agarics in North America. Identifying most of them to family or genus on the basis of field characteristics, including spore print color, is not an insurmountable task for the well-studied amateur with a few good books. Identifying them to species is another matter. In many cases, the only way to distinguish one species from its closest relatives is through examination of microscopic and chemical characteristics.

Most of the deadliest species are gilled mushrooms, so be extra careful about the identification of the edible species. There are, however, a good number of fairly distinctive edible agarics that can be safely identified on the basis of field characteristics alone. In some cases, several species are difficult to tell apart, but each is edible; some of these groups share a common set of key identifying characteristics.

One important characteristic is spore print color, which is listed as a key identifying characteristic for most of the edible gilled mushrooms covered in this book. Under no circumstances should anyone forgo determining spore print color—or any other field characteristic—if it’s listed as a key identifying characteristic. Too many over-anxious novices have made regrettable errors simply because they didn’t have the patience to make a spore print. For the many species of gilled mushrooms that don’t require spore print color as a key identifying characteristic, we have listed it at the end of the mushroom’s full description.

When you become proficient at identifying gilled mushrooms, you might consider expanding your collecting to other agaric species that aren’t included in this book. Most mushroom field guides tell which species are known to be safe for the table, and truly advanced mycophagists can eventually double the number of edible mushrooms they can identify. If you do eventually progress to that level, we hope one thought will stick in your mind: be ever cautious about identifications. Carelessness can make even the most experienced mushroom hunter sick . . . or worse.

Agaricus campestris

Meadow Mushroom (Agaricus campestris)

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

1.Cap fleshy, dome shaped to flat, 1-1/2–5 inches wide; top surface smooth, dry, white or off-white

2.Gills pink, pinkish brown, or dark brown; very closely spaced; free from stalk at maturity

3.Gills covered at first by white, membranous partial veil; mature specimens have membranous white ring around stalk

4.Stalk white, thick; no volva present

5.Found in grass on lawns or pastures, not near trees

6.Flesh white; color unchanged when cut or bruised; no unpleasant odor

7.Spore print dark chocolate brown

DESCRIPTION: The cap is at first dome shaped, nearly flat in larger specimens, and its surface is white, dry, and smooth, graying and cracking somewhat in maturity. The cap flesh is thick, soft, and white. The gills are bright pink at first, very crowded, often slightly attached to the stalk when young but always free in age. In small buttons, the gills are covered by a white membranous partial veil. As the mushroom expands, the veil ruptures to expose the gills, which darken until they’re a rich chocolate brown. The ruptured veil leaves a white membranous ring around the stalk. The stalk is white, less than three inches long, and one-half to three-fourths inch thick. There is no volva around the stalk base. Mature specimens reach a height of up to four inches and a width of five inches. There is no unpleasant odor and no bruising effect associated with this species. The spore print is dark chocolate brown.

FRUITING: The Meadow Mushroom is sometimes found singly, but it is usually grouped or scattered, less frequently in small clusters, in grass on lawns or pastures, especially in moist spots. It can be found throughout North America, usually during summer and fall. The mycelium is perennial, producing mushrooms in the same spot year after year.

The Meadow Mushroom

This is the first kind of mushroom I ever enjoyed. When I was eight, my father invited me to “go mushrooming” in the local cow pastures. I was sure I didn’t like mushrooms, but I was certainly willing to go for a walk with my dad, especially in a place where we might have to flee from an ornery old bull.

I don’t recall whether we found any mushrooms that crisp, early autumn morning, but I do remember the first time I hesitantly tasted Mom’s “Creamed Meadow Mushrooms on Toast.” This, I knew at first bite, was serious good food, quite unlike those horrid cans of pieces and stems.

For several years afterward, when I got off the school bus each fall afternoon, I’d grab a wire-handled tomato basket and head straight for the back pastures of the nearest dairy farm to find a side dish for supper.

To this day, the first one of us that finds some Meadow Mushrooms dutifully notifies the other. And I still like to go out and soak my sneakers on the dew-drenched grass with Dad.

–DAVID FISCHER

SIMILAR SPECIES: Some deadly Amanita species look similar in the button stage; however, these Amanitas lack the Meadow Mushroom’s characteristic pink to brown gills and dark chocolate brown spore print. Also, Amanita species always grow under or near trees. The Meadow Mushroom is sometimes found under trees, too, so if you choose to gather it near trees, examine each specimen very carefully to confirm the other key identifying characteristics. Be especially certain that each specimen has pink to brown gills and no volva.

There are a number of poisonous Agaricus species. Most grow under or near trees. Some are quite similar to the Meadow Mushroom, but they have an unpleasant odor frequently described as “creosotelike,” and most of them bruise yellow, at least on the base of the stalk.

The Spring Agaricus (A. bitorquis or A. rodmani) is edible. Its cap is tannish, its gills are grayish pink at first, and it grows primarily on hard-packed ground in late spring and early summer. The Horse Mushroom (A. arvensis), which is edible (see next entry) is much larger than the Meadow Mushroom. It bruises yellow but has a pleasant odor. The Prince (A. augustus), also edible (see p. 40), has a yellowish brown scaly cap. Like the Horse Mushroom, it bruises yellow but has a pleasant aroma.

EDIBILITY: This is perhaps North America’s best known, most popular edible wild mushroom. Probably every dairy farmer on the continent has either gathered it or been asked by others for permission to scour the cow pastures.

Although it is next-of-kin to the button mushroom found at the grocery store, the Meadow Mushroom is far richer in flavor. It is superior in any recipe that calls for its relatively bland, cultivated brother.

Some people eat the Meadow Mushroom raw, but we must advise against this practice in light of its preference for well-manured soil. Cooking thoroughly will destroy potentially harmful bacteria.

When this species is fruiting, scanning lawns and cow pastures from a car, with or without a pair of field glasses, can be a very effective foraging technique. Also, the Meadow Mushroom tends to be abundant, especially in moist cow pastures. Usually a large quantity can be located in the area where the first specimens were found. A return trip to the same place a week later will often yield a bonus crop.

HORSE MUSHROOM

Agaricus arvensis

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

1.Cap large (four to eight or more inches wide), round; surface dry; white to cream, bruising yellowish; smooth to slightly cracked

2.Gills pale gray to pink in young specimens, chocolate brown at maturity; free from stalk

3.White partial veil leaving white, membranous skirtlike ring on stalk; lower surface of partial veil or ring has white cottony patches

4.Stalk thick, white, bruising yellowish; no volva present

5.Found on lawns and pastures, not near trees (spruce excepted)

6.Odor pleasant, anise- or almondlike

7.Spore print dark chocolate brown

Horse Mushroom (Agaricus arvensis)

DESCRIPTION: The cap is round and large, two to eight inches in diameter. It is white to cream, bruising yellowish within three minutes. The cap surface is smooth but slightly cracked in large specimens. The gills are free from the stalk. They are pale gray to pink, finally aging to chocolate brown. The partial veil is white and membranous, with white cottony patches on its undersurface. In mature specimens, it leaves a skirtlike ring on the stalk and remnants on the edge of the cap. The stalk is three to six inches long, thick (1/2–1-1/2 inches) and smooth surfaced, white to cream, bruising yellowish. There is no volva at the base of the stalk. This mushroom has a pleasant odor, similar to almonds or anise. The spore print is dark chocolate brown.

FRUITING: The Horse Mushroom appears singly to grouped or scattered, sometimes in fairy rings, on lawns, in pastures, or around spruce trees. It is quite common in urban areas, and it’s found throughout North America, fruiting from midsummer through early fall. The mycelium is usually perennial, producing mushrooms year after year.

SIMILAR SPECIES: Some deadly Amanitas look similar in the button stage; however, they lack the Horse Mushroom’s dark chocolate brown spore print and thick, sturdy, robust stalk. The white Amanita species also have a volva at the stalk base; Agaricus species do not.

The Yellow-foot Agaricus (Agaricus xanthodermus), a poisonous West Coast species (see page 153), usually has a darker and rougher cap surface, but some specimens are reportedly white and smooth enough to be confused with the Horse Mushroom. Both species bruise yellowish, but A. xanthodermus‘s odor is strong and foul.

Several other poisonous Agaricus species occur under or near trees. But few of them have the white cap of the Horse Mushroom, and those that do have a disagreeable creosotelike odor.

EDIBILITY: Like other yellow-staining Agaricus species, the Horse Mushroom can accumulate large amounts of heavy metals, so avoid roadsides and industrial areas when collecting this species.

The Horse Mushroom’s flavor makes it a very popular species. Its relatively huge size and coloration—it is often mistaken from a distance for a Giant Puffball—make it hard to overlook. Unfortunately, insect larvae find it as delicious as mycophagists do. Lucky is the mushroom hunter who finds several large specimens that haven’t been invaded.

Its flavor is not extremely rich, but it’s certainly not delicate. The taste is somewhat like the distinctive aroma: mild, pleasant, and nutty, reminiscent of almonds or anise. When cooking, be careful not to overwhelm it with other flavors.

Surprisingly, the Horse Mushroom is regarded suspiciously by many of the same rural folk who are thoroughly familiar with the Meadow Mushroom and the Giant Puffball. This is unfortunate for them but fortunate for those who have adopted it as a favorite edible.

PRINCE

Agaricus augustus

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

1.Caps of buttons dome shaped but usually flat on top (like a marshmallow); caps of mature specimens nearly flat and at least five inches wide

2.Cap surface shows white flesh between fibrous, yellowish brown scales

3.Cap flesh white, staining yellow when cut or bruised

4.Mature specimens have white, membranous, skirtlike ring; no volva present

5.Odor fragrant, anise- or almondlike

6.Spore print dark chocolate brown

DESCRIPTION: The cap is large (four to ten inches wide, sometimes even larger), with white flesh showing between fibrous, yellowish brown scales. The cap is initially marshmallow to dome shaped, expanding until it is quite flat; the edge of the cap is often upturned in mature specimens. The flesh is thick and white, bruising yellowish. The gills are white in very young specimens, become pinkish, and finally turn brown; they are closely spaced and free from the stalk. In the button stage, the Prince’s gills are covered by a white, membranous veil that bears cottony patches on its lower surface. The stalk is three to eight inches long and 3/4–1-1/2 inches thick; it is white and silky near the top and fibrous to somewhat scaly below, becoming brownish in age. The stalk usually extends well down into the ground. Mature specimens have a white, membranous, skirtlike ring on the stalk. This mushroom has a fragrant odor reminiscent of anise or almonds. There is no volva. The spore print is dark chocolate brown.

ST Prince (Agaricus augustus)

FRUITING: This robust mushroom is primarily a western North American species, though it has been reported from many other parts of the continent. It fruits on the ground—singly, in groups, scattered, sometimes even in small clusters—mostly in late summer and fall but sometimes even in springtime. Although the Prince is “naturally” a woodland species primarily associated with various conifers, it is also found in many other habitats (e.g., in grassy areas or disturbed soil, along paths or roads).

SIMILAR SPECIES: The Prince’s overall form and dark chocolate brown spore print distinguish it as a species of the genus Agaricus; its specific description, large size, and pleasant aroma effectively rule out its close relatives. The odor is an important characteristic for all species of this large genus, in that the species that cause digestive upset consistently have a distinctly unpleasant odor of phenol (like creosote). Dangerous Amanita species have a volva and produce white spore prints; Stropharia species have dark purplish brown spore prints and attached gills.

EDIBILITY: This regal Agaricus, like other yellow-staining species of the genus, can accumulate a large amount of heavy metals, so don’t collect it near roads or industrial areas.

The Prince is one of the favorites among devoted mycophagists in western North America, where it is most common. Like many of its relatives, the Prince is consistently rated as a choice edible: meaty, flavorful, and frequently abundant enough to fill a freezer. As a close relative of the Agaricus found on grocery store shelves, the Prince is suitable for use in any general recipe calling for mushrooms.

Some people eat this species raw, but we cannot recommend it. Especially when the Prince is found near agricultural or settled areas, there is no way to rule out the presence of bacteria that could cause gastrointestinal upset.

Like all mushrooms, the Prince should be eaten in moderation when trying it for the first time. Some people react to certain proteins present in various mushroom species, and the genus Agaricus is no exception.

WINE-CAP STROPHARIA

Stropharia rugosoannulata

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

1.Cap two to ten inches wide, dry (slimy only when wet), smooth or cracked; dome shaped to flat; purplish red to reddish brown

2.Gills closely spaced, attached to the stalk but notched; white, becoming purplish brown

3.Stalk fairly thick, solid, with yellowish white to purplish brown ring with radial lines on the upper surface; no volva present

4.Found on the ground, especially in wood chips, sawdust, lawn mulch, gardens, or near compost heaps

5.Spore print dark purplish brown

DESCRIPTION: The cap is two to ten inches wide; initially dome shaped but then expanding until flat or even depressed at the center; and the color of red wine (purplish red to reddish brown), fading to pale yellowish brown at maturity. The cap surface is smooth, and the cap flesh is thick and white to yellowish white. At first, the gills are covered by a white, thick, wrinkled, membranous partial veil that is packed tightly against and between the gills. When the mushroom matures, the partial veil leaves a ring on the stalk that bears distinct radial lines on the upper surface and toothlike projections on the lower edge. In small, immature specimens whose gills are still covered by the partial veil, the gills are white; once the cap expands and ruptures the veil, the gills begin to turn purplish brown, eventually becoming nearly black. The stalk is white, often tinted yellowish below the ring and/or purplish brown above it. The stalk is three to five inches high, typically 1/2–1-1/2 inches thick, and is slightly enlarged at the base. Thick white strands of mycelium (rhizomorphs) are usually attached to the stalk base. The spore print is dark purplish brown.

FRUITING: The Wine-cap Stropharia is found scattered or in groups, sometimes almost clustered, often in large numbers. It typically appears on or near mulch, compost, sawdust, or wood chips. It is found throughout most of North America, fruiting from late spring through early fall. Its mycelium will usually continue to produce mushrooms throughout the season until the substrate has been depleted.

SIMILAR SPECIES: Hard’s Stropharia (S. hardii) is not known to be edible or poisonous. It is similar in stature, but the cap is yellowish brown, lacking the Wine-cap Stropharia’s distinct purplish brown coloration. No other species can be considered as a look-alike if one considers all the key identifying characteristics listed above.

EDIBILITY: Although opinions differ concerning the quality of this mushroom’s flavor, many mycophagists rate it as choice. However, avoid gathering it from garden mulch or other places where shrubs or other ornamental vegetation may have been treated with fertilizers, pesticides, or similarly dangerous chemicals.

In some places, the Wine-cap Stropharia has been cultivated commercially. If you have a compost heap or a pile of untreated garden mulch, you can try “planting” pieces of this species’ cap there in the spring. By the summer’s end, if you keep it well-watered, there’s a good chance that you’ll be able to gather a basketful. This species generally makes an excellent substitute for the grocery store mushroom. It can be gathered in sufficient quantity to last through winter.

Wine-cap Stropharia (Stropharia rugosoannulata)

SHAGGY PARASOL, REDDENING LEPIOTA, AND PARASOL MUSHROOM

Lepiota rachodes

L. americana

L. procera

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

1.Open caps more than three inches wide, with white flesh showing between tan or pinkish to reddish brown fairly concentric scales

2.Cap flesh thick, white; not staining immediately brown when cut

3.Gills free from stalk, very closely spaced, white to dingy white or tinted reddish

4.Thick, white, membranous partial veil covering gills at first, then leaving a movable, bandlike ring on upper stalk

5.Stalk smooth, much thicker at middle or base; white at top, tan to reddish brown below, bruising yellow, orange, or reddish brown; or stalk slender, showing white between tiny brownish scales; base bulbous

6.Thickest part of stalk (or its base) at least one inch thick

7.No volva present

8.Spore print white, not greenish

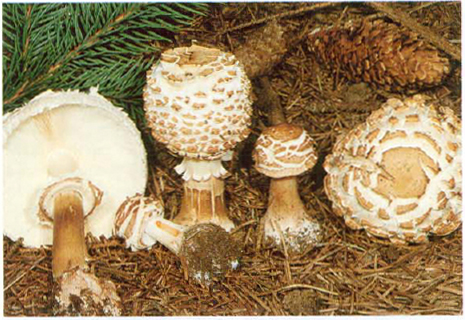

Shaggy Parasol (Lepiota rachodes)

DESCRIPTION: The Shaggy Parasol (Lepiota rachodes) is initially a button with a smooth well-rounded tan or light brown cap two to three inches wide; it has broad, white, closely spaced gills that are covered by a thick, white, membranous partial veil. The stalk is white at first, with an enlarged base. The Reddening Lepiota (L. americana) button is similar, but the button cap is slightly smaller (one to two inches wide) and more reddish brown. Its stalk is thickest at the middle. The Parasol Mushroom (L. procera) button is two to three inches wide at first, tan to brownish, egg shaped, and covered with woolly fibers or scales.

As these mushrooms mature, the cap surface breaks up into distinct, tannish to reddish brown, concentric scales showing white flesh between. The Shaggy Parasol’s scales are coarse, and each scale is fairly smooth surfaced; the other two species’ scales are cottony or woolly. The caps are eventually nearly flat, up to six inches (Reddening Lepiota), eight inches (Shaggy Parasol), or ten inches (Parasol Mushroom) wide, with a brownish or reddish brown disk or knob (umbo) at the top center of the cap. The veil ruptures, exposing the gills and leaving a thick, membranous, white, bandlike, movable ring on the upper stalk. (The ring may break and fall off, but it must be present to confirm identification.)

In all three species, the cap flesh is thick and white. In the Reddening Lepiota and the Shaggy Parasol, the cut flesh quickly stains yellow to pinkish orange, then slowly turns reddish brown. The Parasol Mushroom’s flesh exhibits no immediate staining effect.

In all three species, the stalks remain white or off-white above the ring, but age or bruise tan to brown (Shaggy Parasol) or reddish brown (Reddening Lepiota) below the ring. When mature, the stalks are up to six inches high and one-fourth to one inch thick, except for the Parasol Mushroom: its stalk is no more than one-half inch thick (except, perhaps, at the very base), and may grow as high as a foot or more. It is slender, with a slightly bulbous base, and is covered with tiny brownish scales showing white between them. The surface of the stalk of the Shaggy Parasol and the Reddening Lepiota sometimes breaks into tough, curved scales that peel away from the middle of the stalk.

Reddening Lepiota (Lepiota americana)

These three species produce white spore prints.

FRUITING: The Parasol Mushroom is found on the ground on lawns and in open woods. The Shaggy Parasol and the Reddening Lepiota are typically found on the ground under trees or near stumps, in wood chips or sawdust, in gardens, or on lawns with high wood content. The Shaggy Parasol is associated especially with conifer needles, particularly spruce. The authors have also discovered it growing indoors at the base of potted Norfolk Island pines.

All three species may be found from midsummer through midfall. The Shaggy Parasol usually doesn’t appear before late summer; it and the Parasol Mushroom are often collected during winter in the southern United States. The Reddening Lepiota usually grows in groups or clusters; the Shaggy Parasol in close groups or fairy rings; and the Parasol Mushroom either singly, in loose groups, or well scattered.

The Shaggy Parasol is found throughout much of North America. The others are widely distributed, but the Reddening Lepiota is uncommon and the Parasol Mushroom unknown west of the Rocky Mountains.

SIMILAR SPECIES: Several of the key identifying characteristics above are intended to rule out two poisonous species in the Lepiota family—the Green-spored Lepiota and the Browning Parasol. The Green-spored Lepiota (Chlorophyllum molybdites; see p. 154) is difficult to distinguish at first look, especially from the Parasol Mushroom. But the gills of the Green-spored Lepiota quickly develop a greenish tint, and the spore print is pale green. This unhandy look-alike causes acute nausea and vomiting that last for at least a day or two, so make sure the spore print is white, not pale green.

Parasol Mushroom (Lepiota procera)

The Browning Parasol (Lepiota brunnea) is so similar to the Shaggy Parasol that, until quite recently, it was considered to be merely a variety of L. rachodes. It can, however, be distinguished by its distinct staining characteristic: the flesh quickly stains brown when cut or bruised, without first staining yellow to pinkish orange. The Browning Parasol has only been reported from the West Coast, primarily in California; it causes gastric upset, but not nearly as severe as that caused by the Green-spored Lepiota.

There are many smaller species of Lepiota that are poisonous, even deadly; however, they are rather dainty little mushrooms, not large and robust like the edibles. Don’t gather the edible species unless the opened caps are each more than three inches wide, and do carefully confirm all key identifying characteristics.

These large Lepiota species are classified by some mycologists in a separate genus—Macrolepiota, which simply means “large Lepiota.” Others classify one or another of the large Lepiota mushrooms as either Leucoagaricus or Leucocoprinus species.

EDIBILITY: These three Lepiota species are delicious edibles. The Parasol Mushroom and its shaggy brother are especially prized by those who know them. Strong-flavored, large, and sometimes abundant, they’re a welcome find for mycophagists who are just starting to stock up on wild mushrooms for winter. They’re not very moist to begin with, so drying thin slices of these is a fine way to save a large collection for later use. Canning, pickling, and freezing all work well, too. The Reddening Lepiota is not so highly prized as the other two species, but it is regularly collected for the table in areas where it’s more common than its big brothers.

All three of these meaty, edible Lepiotas are capable of soaking up quite a bit of butter, oil, or margarine, so it’s a good idea to cook them long and slow, using a moderate amount of butter or oil. You can add a splash of water if the mushrooms threaten to dry out as you sauté them.

Each of these mushrooms is particularly tasty baked or broiled, either stuffed first with just a dab of garlic butter or served with a dollop of seasoned sour cream. The Reddening Lepiota takes on a red wine color when cooked; you can be creative in deciding what it should accompany as a side dish. The Shaggy Parasol, on the other hand, becomes rather black when cooked; for this reason, it is especially appropriate for use in meat gravies.

SHAGGY MANE

Coprinus comatus

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

1.White egg- to bullet-shaped mushroom, three to ten inches high

2.Cap surface covered with white to reddish brown, delicate, flaky scales

3.Caps dissolve into thick, black liquid, starting at edge, as they mature

4.Stalk white, slender, hollow

5.Gills extremely crowded, free from stalk; initially white, tinting pink to gray before turning black and dissolving

6.Found on lawns, pastures, or soil

DESCRIPTION: The cap is egg- to bullet-shaped, dry, and white except at the top center of the cap, which is invariably tan to reddish brown. The cap surface, except at the top center, is covered with delicate white to reddish brown flaky scales. The gills are extremely crowded and free from the stalk; they are initially white, soon off-white or grayish, tinting pinkish starting at the edge of the cap, and finally becoming black and dissolving into a thick, black liquid. Initially, the gills are protected by a delicate, cottony, white veil that either remains as a movable ring around the lower part of the stalk or breaks and falls off. The stalk is white, hollow, smooth or with delicate white fibers, usually thicker at the base, three to ten or more inches high and one-half to three-fourths inch thick at the middle. The spore print is black.

FRUITING: This common mushroom is found singly or in groups, sometimes scattered about an area, on lawns, in pastures, or almost anywhere on the ground. It is found throughout most of North America, usually fruiting from late spring through early summer and again from late summer through early fall, but almost year-round in the southern states. It frequently appears in the same place twice each year for several consecutive years, especially in places where it is abundant.

SIMILAR SPECIES: The Shaggy Mane is a very common member of the Inky Cap (Coprinus) genus of mushrooms. Some Coprinus species are poisonous; however, none more than superficially resemble the Shaggy Mane. There are no dangerous look-alikes. Some other Coprinus species are also edible; one, the Mica Cap, is covered in this book (see next entry). Most of the Coprinus species share the strange method of spore dispersal called “deliquescence”: the gills literally dissolve into a thick, black liquid; the spores are then carried by insects or water rather than by the wind.

Shaggy Mane (Coprinus comatus)

EDIBILITY: Most dedicated mycophagists have eaten this common, abundant, and distinctive species. Most consider it excellent, though others use less enthusiastic terms. It is perhaps the most tender edible mushroom covered in this book, and it is especially suitable for sauces, soups, or gravies.

It is important to cook these mushrooms very soon after picking, or the gills will soon begin their process of autodigestion. This process will occur even in the refrigerator and, in fact, quite rapidly in the freezer. It can be delayed only by cooking or parboiling the mushrooms before storing them.

The stalks do not dissolve, though. They can be removed and stored in the refrigerator for several days. If you hold the mushroom cap in one hand, and gently but firmly twist the stalk with the other, they will easily separate from each other. Frequently, the gills will already have started turning pinkish or dark gray near the edge of the cap; if so, just cut off the lower portion of the cap.

Once the stalks have been removed, the caps are ideal for stuffing. They should be lightly sautéed first; otherwise, autodigestion may occur in the oven.

Shaggy Manes, which are called “Lawyer’s Wigs” in England, can often be gathered by the bushel—if you hurry. On a hot, sunny day, Shaggy Manes can dissolve in as little as three to four hours, leaving nothing but a small disk atop the stalk, still dripping the black liquid that contains the mature spores.

Coprinus micaceus

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

1.Cap yellowish tan to yellowish brown, bell or dome shaped, less than two inches wide

2.Cap covered with tiny, crystalline granules; cap also has radial lines, especially prominent near edge

3.Gills whitish to gray, turning inky black and dissolving in mature specimens

4.Stalk white, smooth to minutely fibrous, no more than three inches high; no ring, partial veil, or volva present

5.Found in dense clusters on rotting wood or wood debris

DESCRIPTION: This common member of the Inky Cap genus (Coprinus) is small—typically two to three inches high and one to two inches wide. Initially, each mushroom is completely enclosed in a universal veil; however, this veil is very fragile and breaks up when the mushroom is extremely small, leaving only tiny, glistening, crystalline granules on the cap. These granules rub or rinse off easily, but they must be present in order to confirm identification. The surface of the cap is radially furrowed or lined, especially near the edge. It is yellowish tan, invariably richer in color at the center of the cap; the color fades to gray in mature specimens. The cap is dome, bullet, or bell shaped. The gills are initially white, turning grayish and finally blackish as they dissolve into an inky goo, as happens in most species of this genus. Also, there are no partial gills: each gill extends from the edge of the cap to the stalk and is attached to it. The stalk is white and very slender (one to three inches long and one-eighth to one-fourth inch thick), and its surface is either smooth or minutely fibrous. Usually some capless stalks are evident in each cluster, still standing even though their caps and gills have dissolved and melted away. The spore print is inky black.

Mica Cap (Coprinus micaceus)

FRUITING: The Mica Cap grows exclusively on well-decayed wood, including completely or partially buried wood. It is very adaptive in terms of wood type but has a decided preference for deciduous wood. It always grows in clusters, sometimes with hundreds, even thousands, of specimens on a single log. Its range includes most of North America, and it fruits from midspring through midautumn.

SIMILAR SPECIES: The micalike granules on the cap surface combined with the dissolving gills typical of the genus Coprinus make this species unmistakable. However, because many little brown mushrooms, commonly referred to as “LBMs,” are poisonous, even deadly, be sure to confirm all five of the key identifying characteristics listed above.

EDIBILITY: Although unusually small for a popular edible mushroom, this species is made worthwhile by the sheer number of specimens in a typical fruiting. Like its big brother, the Shaggy Mane, the Mica Cap has a wonderful flavor and a very tender texture. It must, of course, be gathered and cooked fresh, while the gills are still whitish or light grayish.

Because it is quite fragile, harvesting the Mica Cap is a bit time-consuming. But, if enough specimens are still in good condition, it is certainly worth the effort. Because it often fruits in midspring, even before the Yellow Morels are out, it is frequently the first edible wild mushroom that can be gathered fresh each year.

Because of its small size, the Mica Cap dries quickly enough to preserve it that way, provided you have access to a food dehydrator. Otherwise, the gills will start dissolving, and the mushrooms will be a useless mess. And, like all Coprinus species, the Mica Cap cannot be refrigerated because it will dissolve nonetheless. Enjoy it fresh.

FAIRY RING MUSHROOM

Marasmius oreades

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

1.Cap one to two inches wide, smooth, minutely suedelike; light tan with slightly darker central knob, or umbo

2.Gills white or yellowish white, well spaced, slightly attached to stalk or free

3.Stalk 1-1/2–3 inches high, pale yellow to light tan, slender, minutely suedelike, very pliable; no ring, veil, or volva present

4.Found on lawns

5.Spore print white to light tan

DESCRIPTION: The cap is initially dome shaped, soon becoming distinctly bell shaped with a raised knob, or umbo, at the top center of the cap. The cap is one to two inches wide, off-white to light tan on top, and the upper surface is smooth but minutely suedelike. The gills are off-white to pale yellowish tan, fairly well spaced but somewhat less so in small specimens. The gills are barely attached to the stalk. The stalk is slender (less than one-fourth inch thick) and one to three inches high. It, too, is minutely suedelike, essentially the same color as the top of the cap, and very resilient: it can be bent or twisted substantially without breaking in two (this is a very important characteristic to ascertain). This mushroom typically is fragrant. The spore print is white to light tan.

Fairy Ring Mushroom (Marasmius oreades)

FRUITING: This common mushroom is found on lawns throughout North America, fruiting from late spring through early summer. As the common name we use here implies, this species frequently forms fairy rings, essentially circle-shaped patterns of mushrooms, on lawns. Sometimes the entire circle may not be evident, though. Frequently they will fruit in an arc-shaped pattern or simply in a line or in a small group.

SIMILAR SPECIES: One species, the poisonous Sweating Mushroom (Clitocybe dealbata; see p. 158), named for a symptom it typically produces, is sometimes mistaken for the Fairy Ring Mushroom. The Sweating Mushroom, however, can be easily distinguished. The entire mushroom is white to off-white; also, its gills are much more closely spaced and broadly attached to the stalk, usually descending it somewhat. The stalk of this poisonous, so-called look-alike is somewhat tough, but it can be broken without much effort. In contrast, the stalk of the Fairy Ring Mushroom is very difficult to break. The main cause of confusion between these two mushrooms is careless picking. Lawn-inhabiting species of Inocybe will be ruled out by their brown spore prints. As with all edible mushrooms, each specimen should be examined to avoid unpleasant mistakes. Marasmius oreades is also called the “Scotch Bonnet” by some mushroom hunters.

EDIBILITY: This small mushroom, which is very common yet unnoticed by most people, is a popular edible in many parts of the world, including much of Europe. Like almost all small mushrooms that are popular edibles, it makes up for its size by its abundance. A large lawn can yield enough Fairy Ring Mushrooms in one fruiting to make a huge casserole or a large pot of gravy, and the mycelium will usually fruit several times each summer.

The stalks are worthless in the kitchen—they are far too tough to eat. Discard them after you’re sure you’ve identified the mushroom specimens properly. The caps, though, are very tasty and tender. They lend themselves very well to drying; in fact, they are often already well dried by the time they’re picked. Like other species of the genus Marasmius, the Fairy Ring Mushroom revives (reabsorbs enough water to look fresh again) readily when soaked or sprayed with mist from a spray bottle of the sort used for houseplants.

PURPLE-GILLED AND COMMON LACCARIAS

Laccaria ochropurpurea L. laccata

Purple-gilled Laccaria (Laccaria ochropurpurea)

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

1.Cap slightly depressed at center

2.Gills pink (Common Laccaria) or purple (Purple-gilled Laccaria), producing no latex when cut

3.Gills attached to stalk, sometimes descending it slightly (Common Laccaria only)

4.No partial veil, ring, or volva present

5.Found growing in moss or soil

6.Spore print white (Common Laccaria) or pale lilac (Purple-gilled Laccaria)

DESCRIPTION: The Purple-gilled Laccaria (Laccaria ochropurpurea) cap is 1-1/2–6-1/2 inches wide; it is initially purple to brownish purple, fading to grayish white at maturity. The cap is rounded in young specimens, nearly flat—usually with a slight central depression—in mature ones. The cap surface is smooth to slightly roughened. The cap flesh is dull white, often water soaked, and has a slightly disagreeable taste. The gills are pale to dark purple, widely spaced, and have thick edges; they are attached to the stalk. The stalk is grayish white to brownish purple, usually the same color as the cap surface, and slightly roughened. It is two to six inches long and three-eighths to three-fourths inches thick, not noticeably enlarged toward but frequently curved near the base. The spore print is pale lilac.

Common Laccaria (Laccaria laccata)

The cap of the Common Laccaria (L. laccata) is quite rounded and pinkish orange to pinkish brown in young specimens. As it matures, it fades to grayish white and becomes nearly flat, typically with a slight depression at the center. Also, the cap edge is typically uplifted and wavy in mature specimens. The cap ranges in width from one-half to three inches. The cap surface may be smooth or slightly roughened. A longitudinal section reveals thin, water-soaked, pinkish orange to pinkish brown flesh; it has no distinctive taste. The gills are pinkish brown to dingy pink, widely spaced, and thick edged; they are attached to the stalk, often descending it slightly. The stalk is nearly the same color as the cap surface and measures one to four inches long and one-eighth to one-fourth inch thick; it isn’t noticeably narrower or thicker near the top or bottom, but it’s usually twisted or curved. The surface of the stalk is typically roughened by vertical streaks. The spore print is white.

FRUITING: The Purple-gilled Laccaria is found singly or in groups on the ground in grassy areas or under deciduous trees (especially oak) during summer and fall throughout eastern North America.

The Common Laccaria is also found either singly or in groups on the ground in poor soils and in damp mossy or boggy areas. It fruits during summer and fall throughout most of North America.

SIMILAR SPECIES: Several other species of Laccaria are found in North America; most require microscopic examination and understanding of the scientific literature for positive identification. However, those that match all the characteristics described above have been collected and eaten without any adverse reactions. No Laccaria species are suspected of being poisonous.

EDIBILITY: Both of these species are good edibles, though neither has attained widespread gourmet status. They make mediocre side dishes but deserve rave reviews for their wonderful contribution to soups, sauces, and gravies. Each is firm in texture, which also makes them perfectly suitable for stews.

The stalks of the Common Laccaria tend to be elongated and rather fibrous and tough when found growing in sphagnum moss. On the brighter side, specimens gathered in bogs are almost invariably free of insect larvae and require little cleaning. Its frequent habitat in bogs makes the Common Laccaria a reliable and welcome find during droughts or dry spells when few other edible wild mushrooms can be found.

ROSY GOMPHIDIUS

Gomphidius subroseus

Rosy Gomphidius (Gomphidius subroseus)

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

1.Cap slimy, one to three inches wide; rosy pink to dull red, dome shaped to sunken at the center

2.Gills white to grayish, partially descending stalk

3.Stalk slimy, white, tapering to a narrow, yellow base

4.Thin, slimy, partial veil or ring; no volva present

5.Flesh of cap and upper stalk white, but yellow at stalk base

6.Spore print brownish black to black

DESCRIPTION: The cap is one to three inches wide, slimy, rosy pink to dull red; it is dome shaped at first, becoming flat to sunken at the center in age. A small, pointed knob, or umbo, is sometimes present at the center of the cap surface. The gills of young specimens are covered by a slimy, colorless partial veil; at maturity, it remains on the stalk as a thin, slimy ring. The gills are white at first, becoming grayish in age; they partially descend the stalk and are typically soft and waxy. The stalk is white but covered with a colorless layer of slime; it is one to three inches long and one-fourth to three-fourths inch thick, tapering to a narrow, yellow base. The ring around the upper part of the mature stalk is thin and slimy, usually tinted blackish from the spores. A longitudinal section reveals white flesh except at the stalk base, which is lemon yellow. The flesh has a mild taste. The spore print is brownish black to black.

FRUITING: This mushroom is found scattered or in groups on the ground under conifers, especially Douglas fir, during summer and fall. It is most common in the Pacific Northwest, but it also occurs in California, the Rocky Mountains, and rarely in mountainous areas from Virginia to North Carolina.

SIMILAR SPECIES: There are several other Gomphidius species in North America; they are all edible. Each species differs from the Rosy Gomphidius by one or more of the key identifying characteristics listed above.

EDIBILITY: The Rosy Gomphidius is a fleshy, mild-flavored mushroom. Some mycophagists place it high on their list of favorites, while others consider it mediocre. You’ll have to decide for yourself. For aesthetic reasons, the slime layer should be removed before cooking. It can be wiped off easily.

WOOLLY CHROOGOMPHUS

Chroogomphus tomentosus

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

1.Cap surface matted, feltlike to woolly, one to three inches wide, dull orange to brownish orange, dome shaped to nearly flat

2.Gills thick, widely spaced, dull orange to grayish orange, partially descending stalk

3.Stalk dull orange to brownish orange, dry, feltlike to woolly, tapering to a narrow base

4.Partial veil or ring thin and fibrous, often indistinct; no volva present

5.Flesh yellowish orange to brownish orange

6.Spore print grayish black to black

DESCRIPTION: The cap is dull orange to brownish orange, one to four inches wide; the surface is dry, covered with a feltlike or woolly mat of fibers. The cap is dome shaped when young, becoming nearly flat at maturity. The gills of young specimens are covered by a fibrous, pale yellow to dull orange partial veil that only sometimes leaves a noticeable ring of fibers near the top of the mature stalk. The gills are dull orange to grayish orange at first, becoming grayish orange to gray in age; they are widely spaced and partially descend the stalk. The stalk is 2–7-1/2 inches long and three-eighths to three-fourths inch thick, tapering downward to a narrow base; its surface has the same color and texture as the cap. The flesh is yellowish orange except at the stalk base, which is brownish orange. The flesh has a mild taste. The spore print is grayish black to black.

Woolly Chroogomphus (Chroogomphus tomentosus)

FRUITING: The Woolly Chroogomphus grows scattered or in groups on the ground under conifers, especially hemlock and Douglas fir. It is found during summer and fall along the West Coast and in the Rocky Mountains.

SIMILAR SPECIES: C. leptocystis, a very similar, edible species found under conifers during autumn in the Pacific Northwest, has a grayer cap. Other Chroogomphus and Gomphidius species have slimy to sticky cap surfaces.

EDIBILITY: This mushroom is usually plentiful during moist periods in autumn. It is appreciated more for its abundance than for its taste, which is a rather subjective matter among those mushroom fanciers who have tried it.

BROWNISH CHROOGOMPHUS

Chroogomphus rutilus

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

1.Cap surface sticky, one to four inches wide, reddish brown to orangish brown or greenish brown; cap dome shaped, often with a pointed knob, or umbo

2.Gills brownish yellow or greenish brown to grayish brown; widely spaced, partially descending stalk

3.Stalk tapering to a narrow base; dull brownish yellow to dull orange, often with reddish tints

4.Partial veil or ring thin and fibrous, often indistinct; no volva present

Brownish Chroogomphus (Chroogomphus rutilus)

5.Flesh pale brownish yellow to pale orange

6.Spore print grayish black to black

DESCRIPTION: The cap has a sticky, reddish brown to orangish brown or greenish brown surface; it is one to four inches wide, dome shaped, usually with a small, pointed knob, or umbo, at the center. The gills of young specimens are covered by a fibrous, pale orangish brown partial veil that may or may not leave a visible ring near the top of the mature stalk. The gills are brownish yellow to greenish brown at first, becoming grayish brown in age; they are fairly widely spaced and partially descend the stalk. The stalk is two to seven inches long and three-eighths to three-fourths inches thick, tapering downward to a narrow base; it is dull brownish yellow to dull orange, often with reddish tints in age. The flesh of the cap and stalk is pale brownish yellow to pale orange but darker toward the stalk base. The flesh has a mild taste. The spore print is grayish black to black.

FRUITING: This species is found scattered or in groups on the ground under conifers, especially pine trees. It is found from late summer through fall and into early winter in areas with milder climates. Its range includes much of North America.

SIMILAR SPECIES: The Wine-colored Chroogomphus (C. vinicolor), which is edible, is nearly identical, but it is smaller and grayish brown with wine-red or reddish orange stains. Gomphidius species have white cap flesh. Like other Chroogomphus species, C. rutilus was previously classified in the genus Gomphidius.

EDIBILITY: The Brownish Chroogomphus is often abundant during cool, rainy periods, particularly in the Pacific Northwest. Like many of its equally mild-flavored relatives, it has a close circle of devotees. Those who truly enjoy it appreciate the lack of competition from other mushroom hunters, though this species is perhaps the most popular edible in the Gomphidius family.

Cantharellula umbonata

Grayling (Cantharellula umbonata)

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

1.Small, gray cap with a small, pointed, central knob, or umbo

2.Gills forked, descending stalk; white to cream colored, slowly bruising yellow to reddish

3.Stalk slender, sturdy, off-white

4.Found only in moss on the ground, not on moss-covered wood

5.Gills do not produce latex when cut

6.Spore print white

DESCRIPTION: The cap is 1/2–1-1/2 inches, rarely two inches, in diameter. The cap surface is smooth and gray, typically with a small but distinct central knob, or umbo. The gills are repeatedly forked; they are white with a creamy or grayish tint. The gills bruise yellow to red, usually within ten minutes or so; they descend the stalk noticeably, and they produce no latex when cut. The stalk is off-white and slender but sturdy. The spore print is white.

FRUITING: The Grayling is found only in moss, usually in fairly sunny areas. It typically appears scattered about in a bed of moss, fruiting during cool periods from late summer through late fall. It tends to reappear in the same spot year after year; its known range is limited to northeastern North America.

SIMILAR SPECIES: The key identifying characteristics presented for the petite Grayling are very reliable. The only other species likely to be mistaken for this little mushroom are very small Lactarius species. They must be ruled out by cutting across the gills of a fresh specimen to determine whether latex is produced.

This species was formerly classified as Cantharellus umbonatus, the Knobbed Chanterelle.

EDIBILITY: The diminutive but distinctive Grayling tastes as delicious as the true chanterelles do, making it one of the smallest mushrooms worth gathering for the table. Once you’ve located the first few specimens, keep looking around in the same bed of moss and in others nearby; you’re likely to find plenty more for your basket. Be especially careful to examine every specimen you pick, though, to make sure no other little mushrooms are inadvertently collected.

The Grayling is on the very short list of gilled mushrooms that can be dried without a significant loss in quality. The stalks may be slightly chewy after the mushrooms have been reconstituted, but the caps will certainly be just as tender and tasty as they are when fresh. Sauté them lightly, with just a dab of butter. Their size limits their versatility, but their rich, wonderful flavor makes them exquisite as a simple side dish. The flavor is strong enough that a fair quantity can even be used as a pizza topping. Omelets and other recipes that need only a small amount of mushrooms are appropriate for smaller collections.

BLEWIT

Clitocybe nuda

Blewit (Clitocybe nuda)

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

1.Cap dome shaped to flat, smooth, lilac with gray or tan tints, two to six inches wide

2.Gills pale violet to pinkish brown, notched at stalk

3.Stalk pale violet to brownish lilac; no ring, veil, or volva present

4.Spore print pale pinkish tan

DESCRIPTION: The cap is rounded to almost flat, two to six inches wide; it’s purplish, but usually with some grayish or tannish areas. The cap surface is smooth and dry to moist. The gills are light purple, often tinted pinkish brown; they are closely spaced and attached to, but notched near, the stalk. The stalk is also purplish, with a white, silky sheen most noticeable in young specimens. It usually has an enlarged base and is rather stout—one-half to one inch thick and only one to three inches high. The spore print is pale pinkish tan.

FRUITING: Blewits are sometimes found singly but usually in groups, scattered or in small clusters, on or near leaves, pine duff, compost piles, old wood chips or sawdust, and on lawns under pine trees. They can be gathered throughout much of North America from late summer through late fall.

SIMILAR SPECIES: Few species of mushrooms—none of which are closely related—share the overall purplish coloration of the Blewit’s cap surface, gills, and stalk. The distinctive spore print color will rule out other purplish mushrooms, including the poisonous Lilac Fiber Head (Inocybe lilacina) and Cortinarius species, which have brown and rusty-brown spores, respectively. The Blewit is also classified as Lepista nuda.

EDIBILITY: The Blewit is highly regarded among dedicated mycophagists, not only for its wonderfully rich flavor, but also for its frequent abundance. Its texture is very close to other fleshy, gilled mushrooms; it is accordingly versatile in the kitchen—a good all-purpose mushroom.

When it is found fresh and collected in quantity, the Blewit provides an excellent opportunity to stock up on wild mushrooms for the cold days of winter. Blewits can be frozen fresh with satisfactory results, but they retain their flavor better and take up less freezer space if they’re partially cooked before freezing. Drying thin slices also works well, but freezing is the superior option.

ORANGE-LATEX, ORANGE BOG, AND FROSTED ORANGE-LATEX MILKIES

Lactarius deliciosus

L. thyinos

L. salmoneus

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

1.Cap orange, somewhat concentrically zoned; or cap white and slightly velvety when young but orange and smooth when mature

2.Gills orange, immediately exuding an orange latex when cut

3.Stalk orange; no ring, partial veil, or volva present

4.Latex mild tasting (taste a tiny bit and then spit it out)

DESCRIPTION: The Orange-latex Milky (Lactarius deliciosus) has an orange cap, 2–5-1/2 inches wide, with three to six rusty orange concentric zones. It is dome shaped when young, expanding until nearly flat, typically with a slightly sunken center. Fresh caps are moist and sticky. Green stains often develop in age, especially near the cap edge. The gills are orange, somewhat crowded, and attached to the stalk; they fade to orangish yellow in age and stain green when bruised. When cut, the gills immediately exude an orange latex that tastes mild. The stalk is orange, one to three inches long and three-eighths to one inch thick; its surface is smooth, sometimes with tiny, shallow pits. The stalk also usually develops green stains in age or when bruised. The flesh of both cap and stalk is pale yellow, staining green; it is somewhat fragrant and tastes mild.

DA Orange-latex Milky (Lactarius deliciosus)

Orange Bog Milky (Lactarius thyinos)

The Orange Bog Milky (L. thyinos) is very similar to the Orange-latex Milky; however, the cap has alternating concentric zones of orange and pale yellow, and it is usually somewhat slimy. Also, the stalk of this species is sticky and often distinctly pitted. The orange latex slowly stains the gills and other parts of the mushroom dull red, not green. As with the Orange-latex Milky, the flesh is somewhat fragrant and tastes mild.

The Frosted Orange-latex Milky (L. salmoneus) is also quite similar to the Orange-latex Milky. Its characteristic differences include a smaller, carrot-orange cap that is typically covered by a white, slightly velvety coating, especially in young specimens. As the mushroom matures, the white coating is worn away, exposing the orange cap surface. The gills, latex, and stalk of this species are also orange. The flesh of both cap and stalk is orange; again, it is somewhat fragrant and mild-tasting.

The spore prints of these species range from off-white to pale yellow.

FRUITING: These lactarii are found singly, grouped, or scattered on the ground in woods during summer and fall. The Orange-latex Milky is found in much of North America under conifers, especially pine. The Orange Bog Milky occurs in northeastern North America west to Michigan; it prefers bogs or wet woodlands, typically in moss. The Frosted Orange-latex Milky is found under pines in the southeastern United States from Florida to North Carolina and Texas.

Frosted Orange-latex Milky (Lactarius salmoneus)

SIMILAR SPECIES: Some fleshy Lactarius species found in North America are poisonous or cause adverse reactions. The key identifying characteristics rule them out.

EDIBILITY: Although the Orange-latex Milky is especially popular in Europe and the Soviet Union, these species are less highly rated by North American mycophagists. The texture is often somewhat granular, and the flavor is usually not outstanding. However, the flavor of these mushrooms and such strong-flavored freshwater fish as trout balance each other quite well when they are sautéed together. Pickling or use in stews brings out these common species’ best flavors, and they are often abundant enough to make collecting them worthwhile.

Lactarius rubrilacteus

Bleeding Milk-cap (Lactarius rubrilacteus)

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

1.Cap two to five inches wide, orange to orangish brown or reddish brown, with concentric zones and sometimes with green tints

2.Stalk pale orange to pale orangish brown, hollow, distinctly narrower at base; no partial veil, ring, or volva present

3.Gills dull orange to pale reddish brown

4.Gills immediately exuding dull red to orangish red latex when cut; latex mild-tasting (taste a tiny bit and then spit it out)

DESCRIPTION: The cap is round topped with an inrolled edge at first, becoming broadly vase shaped. The cap is smooth and sticky, two to five inches wide; it is orange to orangish brown or reddish brown overall, with several concentric zones typically alternating in color between a pale yellowish orange and a dark orangish brown or reddish brown. Buttons may be green overall; mature specimens may have greenish stains or streaks on the cap surface. The cap flesh is thick, creamy white, and mild-tasting; it may slowly stain greenish after being exposed to air. The gills are dull orange to pale reddish brown, sometimes with greenish stains when bruised or older; they are closely spaced and attached to the stalk, sometimes descending it a bit. When cut, the gills immediately produce a scanty (especially in dry weather), mild-tasting latex that is dull red to orangish red. The stalk is pale orange to pale orangish brown; it is usually smooth, but it may have tiny, shallow pits. The stalk is 1–2-1/2 inches long and 3/8–1-1/8 inches thick at the middle, tapering to a narrower base; it is hollow, especially at maturity. The spore print is pale yellow.

FRUITING: This mushroom occurs from the Pacific Northwest south to California; it has also been found in New Mexico. It is found scattered or in groups on the ground under conifer trees; it fruits during summer and autumn.

SIMILAR SPECIES: The edibility of L. barrowsii, which is known only from New Mexico, has not been established; its cap lacks zones and is paler (whitish to pinkish tan), and its latex is darker, a port wine red. It is only considered a look-alike because its gills do stain green when bruised or in age.

The Bleeding Milk-cap was previously classified as L. sanguifluus.

EDIBILITY: The Bleeding Milk-cap is highly rated. It is a firm, tasty mushroom that makes a fine substitute in recipes that call for the better-known Orange-latex Milky.

INDIGO, SILVER-BLUE, AND VARIEGATED MILKIES

Lactarius indigo

L. paradoxus

L. subpurpureus

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

1.Cap concentrically zoned; dark blue, grayish blue, silvery blue, or wine red overall, with or without greenish stains

2.Gills dark blue, grayish blue, or reddish brown; slowly staining greenish in age or when bruised; slowly exuding a scant dark blue, wine red, or wine brown latex when cut

3.Stalk dark blue, grayish blue to grayish green, or wine red with dark reddish brown pits; with or without greenish stains; no ring, partial veil, or volva present

DESCRIPTION: The Indigo Milky (Lactarius indigo) has a concentrically zoned dark blue to grayish blue or silvery blue cap that typically develops greenish stains in age or when bruised. The cap is two to six inches wide; it is dome shaped with an inrolled edge when young, then becomes nearly flat and typically has a slightly sunken center at maturity. Fresh caps are moist and sticky. The gills are dark blue to grayish blue at first, eventually fading to greenish yellow, and slowly staining green when bruised or in age; they are fairly crowded, and are attached to the stalk. When cut, the gills exude a scant dark blue latex that slowly changes to dark green. The stalk is dark blue to grayish blue, 3/4–3-1/2 inches long and 3/8–1 inch thick; its surface is smooth and typically dry. The flesh of both cap and stalk is whitish, quickly staining blue when cut and slowly turning greenish; the flesh and latex taste mild to slightly bitter or somewhat peppery.

The Silver-blue Milky (L. paradoxus) has a concentrically zoned, grayish blue to silver blue cap that often has pinkish brown tones near the edge, and pale green stains in age or when bruised; it is 1–3-1/4 inches wide. Immature caps often lack concentric zones, and have a silvery sheen overall. The cap is dome shaped with an inrolled edge when young, expanding until it is nearly flat, typically with a somewhat sunken center. Fresh caps are moist and sticky. The gills are reddish brown, somewhat crowded, and attached to the stalk; they become grayish green in age, and stain green when bruised. When cut, the gills exude a scant reddish brown latex that slowly changes to green. The stalk is pinkish gray with green stains in age or when bruised; it is 1–1-3/4 inches long and 3/8–3/4 inch thick. The surface of the stalk is smooth and typically dry. The flesh of both cap and stalk is pale green and slowly darkens after exposure to air; it tastes mild to slightly bitter or somewhat peppery.

Indigo Milky (Lactarius indigo)

Silver-blue Milky (Lactarius paradoxus)

Variegated Milky (Lactarius subpurpureus)

The Variegated Milky (L. subpurpureus) has a somewhat concentrically zoned dark wine red to pale pink cap that develops green stains in age; it is one to four inches wide, dome shaped with an inrolled edge when young, becoming nearly flat with a typically sunken center at maturity. Fresh caps are moist and sticky. The gills are wine red, becoming green-spotted in age and staining greenish when bruised; they are closely spaced and are attached to the stalk. When cut, the gills exude a scant, wine red latex that tastes mild to faintly peppery. The stalk is wine red, 1–3-1/2 inches long and 1/4–5/8 inch thick; its surface is smooth but has small, shallow, dark reddish brown pits. The flesh of both cap and stalk is whitish to pale pink, staining red and then greenish; it tastes mild to slightly peppery.

The spore prints of these species range from pale cream to yellow.

FRUITING: These lactarii are found singly, grouped, or scattered on the ground in woods during summer and fall; the Silver-blue Milky is also collected as late as February in its southern range. The Indigo Milky is found in eastern North America, west to Michigan and south to Texas; it prefers oak and pine woods. The Silver-blue Milky occurs from southeastern Canada to Florida and west to Texas. It grows under oak, pine, and palmetto palm trees, especially on wooded lawns. The Variegated Milky grows in mixed woods, especially hemlock and pine, from southern Canada to the Gulf Coast region.

SIMILAR SPECIES: Some fleshy “Milky” (Lactarius) mushrooms found in North America are poisonous or cause adverse reactions; the key identifying characteristics provided here easily rule them out.

EDIBILITY: The flavor and texture of these three species are quite similar to those of most of the other Lactarius species covered in this book. They are not generally regarded as choice, although they certainly have their following. Like most Milkies, they are suitable for a wide variety of recipes such as casseroles, and in some years these mushrooms can be collected in great quantity, filling the baskets of those who like to get their mushrooms fresh from the woods.

VOLUMINOUS-LATEX, HYGROPHORUS, AND CORRUGATED-CAP MILKIES

Lactarius volemus

L. hygrophoroides

L. corrugis

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

1.Cap and stalk dry, reddish brown to orangish brown, smooth to wrinkled, lacking concentric zones of alternating colors

2.Gills whitish to pale yellow, immediately exuding white to cream latex when cut

3.Latex tastes mild or slightly sour, not bitter or peppery (taste a tiny bit and then spit it out); latex doesn’t become yellow after exposure to air

4.Cap and stalk flesh white; mild-tasting, not bitter or peppery; odor pleasant or fishlike

5.Stalk has no partial veil, ring, or volva

Voluminous-latex Milky (Lactarius volemus)

Hygrophorus Milky (Lactarius hygrophoroides)

DESCRIPTION: The Voluminous-latex Milky (Lactarius volemus) cap is dry, orangish brown, and two to five inches wide; its surface is smooth to slightly wrinkled and lacks concentric zones of alternating colors. It is typically flat; in mature specimens, there is a slight depression at the center of the cap. The gills are closely spaced and attached to the stalk; they are pale cream, slowly staining brown when bruised. When cut, the gills produce abundant white latex that has a mild taste and slowly turns a cream color (not yellow) and stains the gills brown. The stalk is two to four inches long and three-eighths to three-fourths inch thick, narrowing slightly at the base; it is orangish brown. The flesh of the cap and stalk is white, mild-tasting, and has a mild to fishlike odor, especially noticeable in mature specimens.

The Hygrophorus Milky (L. hygrophoroides) has an orangish brown cap and well-spaced white to cream-colored gills that descend the stalk noticeably and exude a mild-tasting white latex that neither changes color nor stains the gills.

Corrugated-cap Milky (Lactarius corrugis)

The Corrugated-cap Milky (L. corrugis) has a reddish brown, distinctly wrinkled cap and closely spaced, pale yellow to yellowish brown gills that exude plentiful white latex that stains the gills brown. The flesh of the cap and stalk is white, mild-tasting, and has a mild to distinctly fishlike odor.

The spore prints of these species range from white to cream or pale yellow.

FRUITING: These mushrooms are found singly, scattered, or in groups on the ground in woods. They occur throughout eastern North America and west to Minnesota and Texas. All three species fruit from early summer through early autumn.

SIMILAR SPECIES: None of the many other North American Lactarius species have the unique combination of key identifying characteristics listed above.

EDIBILITY: All three of these species are widely rated as choice edible wild mushrooms by those mycophagists who’ve tried them. They are firm, meaty mushrooms that can be prepared and enjoyed in a wide variety of recipes. Casseroles and thick sauces are especially suitable. They frequently fruit in large numbers; so this, along with their fairly large size, makes them a prize find for the mushroomer.

Oudemansiella radicata

Rooted Oudemansiella (Oudemansiella radicata)

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

1.Cap tannish brown to gray, two to four inches wide, covered with a translucent, wrinkled, rubbery cuticle

2.Gills white, well spaced, attached to stalk

3.Stalk long, slender, white at top, whitish tan to grayish brown at base; long, rootlike appendage below ground; no ring, veil, or volva present

4.Found on the ground in deciduous woods or on lawns

5.Spore print white

DESCRIPTION: This is a tall, slender, and graceful gilled mushroom. The cap is slightly rounded to almost flat, one to four inches wide, and quite thin fleshed. It is covered with a rubbery, translucent cuticle that is fairly wrinkled—especially near the center of the cap—and there is usually a central knob, or umbo. The cuticle is very slippery when moist. The gills are white, fairly well spaced, and fairly resilient (bending considerably without breaking); they are attached to the stalk. The stalk is slender, no more than one-half inch thick except at the very base (where it is thickest), and white near the top but usually streaked with grayish tan to brown hues toward the base. The stalk is three to ten inches tall, except in very immature specimens. Holding the base of the stalk gently but firmly and pulling up slowly will reveal the “root”; it is three to six inches long, tapering to a point. (This underground appendage is sometimes difficult to pull up, especially on lawns.) The spore print is white.

FRUITING: This distinctive species is very common in deciduous woods and on lawns throughout eastern North America and into the Midwest during summer and fall.

SIMILAR SPECIES: The edible O. longipes is nearly as tall and slender stalked, but it has a smaller, brown, velvety cap. No other mushroom species really come close to matching the key identifying characteristics listed above, especially if one considers the distinctive cap cuticle and the rootlike stalk appendage. The Rooted Oudemansiella is classified as Xerula furfuracea by some mycologists; it was previously called Collybia radicata.

EDIBILITY: This mushroom has a wonderful flavor, though some people complain that the rubbery cuticle makes it undesirable. Since the cuticle is almost impossible to remove, it is wise to cook the Rooted Oudemansiella until the top surface of the cap is well browned and dry. Grilling works very well. The stalk tends to be a bit chewy, but it can be removed quite easily. Mushroom hunters who are familiar with this species often collect the caps only and leave the stalks standing in place.

The long stalk has its advantage: insects never seem to get to the cap until at least a couple of days after the mushroom fruits. If you gather a good quantity, these handsome mushroom caps are thin fleshed enough that they dry quickly. Unfortunately, the cuticles are just as rubbery after the dried mushrooms have been reconstituted. Again, the best bet is to cook them until the top surface of each cap is dry.

GYPSY

Rozites caperata

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

1.Cap orangish yellow to orangish brown, with a faint white coating, especially at the center; two to six inches wide, egg shaped to nearly flat

2.Gills of young specimens covered by yellowish white, membranous partial veil

3.Gills pale yellowish white to dull brown; closely spaced, attached to stalk

4.Stalk pale yellow to yellowish brown, moderately thick

5.Stalk of mature specimens has distinct, membranous, yellowish ring

6.Found on the ground in woods

7.Spore print rusty brown

DESCRIPTION: The cap is orangish yellow to orangish brown, with a distinct white coating, especially near the center. The cap is two to six inches wide, egg shaped at first but nearly flat at maturity. The cap flesh is thick and white. The gills of very young specimens are covered by a yellowish white, membranous partial veil. The gills are initially pale yellowish white, becoming yellow and finally dull brown. The stalk is pale yellow to yellowish brown, two to five inches long and three-eighths to three-fourths inch thick; it is narrower toward the top. All but the smallest specimens whose gills are still covered by the partial veil have a distinct, yellowish, membranous ring near the top of the stalk. The spore print is rusty brown.

FRUITING: The Gypsy is usually found scattered, often in groups and rarely singly, on the ground in woods. It is primarily a fall mushroom but often fruits during cooler periods from middle to late summer. Its range includes many parts of northern North America, but it most frequently occurs in the Northeast and the Pacific Northwest; it also occurs at higher elevations in the southern United States.

Gypsy (Rozites caperata)

SIMILAR SPECIES: Few mushrooms of this size produce rusty brown spore prints and have membranous partial veils or rings. Diligent confirmation of all the key identifying characteristics listed above will rule out all other species.

EDIBILITY: The Gypsy is an excellent edible mushroom, often collected in large quantities in the northern corners of the United States. It is equally common and popular in many parts of Europe, where it is sometimes sold commercially. This tender-fleshed mushroom should be preserved, prepared, and cooked like most other fleshy gilled mushrooms.

WHITE MATSUTAKE

Tricholoma magnivelare

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

1.Caps of buttons white, two to five inches wide, with cottony, inrolled edges

2.Expanded caps large and robust (at least four inches wide) with yellowish brown to reddish brown fibers and scales

3.Flesh thick and firm, with spicy, fragrant odor; white, not changing color when cut

4.Gills very closely spaced; attached to but notched near stalk; white, staining pinkish brown when bruised

5.Gills of buttons covered by thick, white, cottony-membranous partial veil

6.Stalk white with yellowish brown to pinkish brown scaly patches beneath a thick, membranous ring

7.Ring white on top, yellowish brown to pinkish brown below

White Matsutake (Tricholoma magnivelare)

DESCRIPTION: The cap is white at first, fairly smooth surfaced, and rounded, with a cottony, inrolled edge; it develops yellowish brown to reddish brown fibers and scales and is nearly flat in age. The cap is 2–7-1/2 inches wide. The cap flesh is thick, firm, and white and does not change color when cut or bruised. The gills are white, staining pinkish brown when bruised; they are very closely spaced, attached to the stalk, and notched near it. The gills of young specimens are covered by a thick, white, membranous partial veil. The stalk is white in young button specimens. As the mushroom matures, the partial veil ruptures, leaving on the stalk a thick, white, membranous ring that is white on the upper surface and yellowish brown to pinkish brown on the lower surface. In mature specimens, the stalk is white above the ring, but below the ring, the stalk is covered by scaly, yellowish brown to pinkish brown patches. The mature stalk is two to six inches long and 3/4–1-1/2 inches thick, narrowing toward the base. This species has a distinctly spicy, fragrant odor. There is no volva or universal veil. The spore print is white.

FRUITING: This large mushroom is found singly or in groups, on the ground in wet or sandy soil under conifers, especially hemlock and fir. It occurs throughout much of northern North America—from Maine west to the Rocky Mountains and the Pacific Northwest—fruiting from late summer through fall, even into late winter in places with relatively mild climates (such as the Puget Sound area).

SIMILAR SPECIES: The Fragrant Tricholoma (T. caligatum), which is edible (see next entry), shares the White Matsutake’s distinct, spicy aroma, but it has a smaller, reddish brown cap and a white partial veil or ring with reddish brown patches below. The Imperial Cat (Catathelasma imperialis), also edible (see p. 74), has a larger, dingy grayish brown cap and a thick stalk with a flaring, double-layered ring and lacks the other species’ distinctive aromas. The White Matsutake is sometimes classified as Armillaria ponderosa.

EDIBILITY: This fleshy, robust mushroom is usually rated as an excellent edible, though a few people find it too rich and aromatic for their tastes. It is especially popular among Japanese Americans, who know it from their ancestors’ home across the Pacific Ocean.

One large cap will liven up a big soy sauce stir-fry, but this fragrant mushroom works well in any recipe that calls for the typical commercially available mushroom or any other fleshy variety. If you’re looking for a mushroom whose character will not be lost amid strong cheeses and such, the White Matsutake is an excellent candidate.

FRAGRANT TRICHOLOMA

Tricholoma caligatum

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

1.Cap two to five inches wide; rounded to nearly flat; whitish or tan between reddish brown to brown scales and hairlike fibers

2.Gills white, staining brownish in age; closely spaced, attached to stalk

3.Stalk white to pale tan above a flaring, membranous, white to brownish ring

4.Stalk covered with reddish brown to brown scales and fibers below ring; no volva present

5.Fragrance distinctly spicy

6.Spore print white

DESCRIPTION: The cap is two to five inches wide, dome shaped to nearly flat; it has whitish to brownish flesh showing between dry, flattened, reddish brown to brown scales and fibers. The cap flesh is thick and white. The gills are closely spaced and attached to the stalk; they are white, often staining brownish in age. The gills of young specimens are covered by a whitish, membranous partial veil that later remains on the stalk as a white to brownish ring. At first, the ring is flared open at the top. The stalk is two to four inches tall and 3/4–1-1/4 inches thick, sometimes thickest at the middle; it is white to pale tan above the ring but covered with reddish brown to brown scales and fibers below the ring. This mushroom has a distinctly fragrant, spicy aroma. The spore print is white.

FRUITING: The Fragrant Tricholoma is found singly or scattered and occasionally in groups on the ground in woods and typically fruits in late summer or fall. It is especially associated with oak and pine trees on the East Coast and with various conifers on the West Coast. Its range includes many parts of North America, excluding the Midwest and the Rocky Mountains, but it is only common in eastern North America.

SIMILAR SPECIES: Some varieties of this species apparently lack the spicy aroma (some reportedly smell unpleasant); such specimens are nonetheless pleasant after cooking. The edible Fetid Tricholoma (T. [or Armillaria] zelleri) has orangish brown scales and fibers, and an unpleasant odor and taste; like the unpleasant-smelling varieties of the Fragrant Tricholoma, it is enjoyable once cooked. The White Matsutake (T. magnivelare), also edible (see preceding entry), shares the spicy aroma; it is larger, and is not as distinctly scaly and hairy as the Fragrant Tricholoma. The Fragrant Tricholoma is sometimes classified as Armillaria caligata and called the Fragrant Armillaria.

SM Fragrant Tricholoma (Tricholoma caligatum)

EDIBILITY: This is rated as a choice edible mushroom. Its taste and aroma are remarkably similar to those of the White Matsutake; we, therefore, refer you to that species’ “Edibility” section for culinary suggestions.

IMPERIAL CAT

Catathelasma imperialis

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

1.Cap six to sixteen inches wide, dome shaped to nearly flat; dingy gray to dingy brown

2.Gills broad, closely spaced, descending stalk; yellowish to gray, sometimes tinted greenish

3.Stalk thick, tapered downward to a pointed base; two-layered ring on stalk; no volva present

DA Imperial Cat (Catathelasma imperialis)