Chapter 5

Tawney's Century, 1540–1640: The Roots of Modern Capitalist Entrepreneurship

The Weber-Tawney Thesis on Protestantism and Capitalism: The Role of Protestant Dissenters in the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions (1660–1820)

One of the very most remarkable features of the Industrial Revolution era is that Non-Conformists or Dissenters—those Protestants who refused to conform to the officially established Church of England1 —accounted for a remarkably high proportion, perhaps one half, of the scientists and inventors listed in the Royal Society (founded 1660) and the related Lunar Society of Birmingham (founded 1764).2 Even more important for the history of entrepreneurship is the fact that they also accounted for at least half of the known entrepreneurs (and other business leaders) of the Industrial Revolution era itself, up to circa 1820. Yet Dissenters were then a very small minority: consisting of about 1,250 congregations in later eighteenth-century England, comprising about 5 percent and certainly under 10 percent of the population.3

There is no agreed upon explanation for this extraordinary phenomenon. Some various hypotheses will be offered in the subsequent discussion of the role of religion in the early-modern English and Scottish economies, in the context of the very well known, and still hotly debated Weber-Tawney thesis. For a variety of reasons that will soon become apparent, the focus of this discussion is on Richard Tawney (1880–1962), unquestionably one of the very most important economic historians that England has ever produced: in particular, on his role in seeking to explain the emergence of modern capitalist entrepreneurship in what is now commonly called “Tawney's century,” 1540–1640.4 The central thesis of this current study, however, is that all of the events and turning points leading to the rise or dramatically significant expansion of modern forms of capitalism, per se, of a truly modern capitalist ethos, and thus of entrepreneurship, took place, not in Tawney's century, but rather in the following century, 1640–1740, the one preceding the modern Industrial Revolution era. Indeed, this thesis is indicated by the very statement that begins this study.

With deeply held Christian and Fabian socialist views, Tawney had become fascinated with the relationship between Protestantism and the emergence and development of modern capitalism, and implicitly of modern capitalist entrepreneurship.That led, in 1926, to the publication of his most famous book: Religion and the Rise of Capitalism. While highly esteemed for the vast amount of new information that it supplied on both religion and society in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England, the book's chief importance lies in explaining, elaborating on, and propagating the much earlier thesis on this issue, initially published (in 1904–5) in German: Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism.5

Neither author, it must be stressed, ever proposed that Protestantism was responsible in any way for the actual birth of European capitalism, for they were well aware that its origins were purely medieval. Furthermore, they were far from being the first scholars to make a link between Protestantism and modern capitalism, a linkage involving a wide variety of theories. Their goal was instead to provide an analytical framework, in the context of historical sociology, to explain how one particular form of Protestantism—Calvinism—ultimately influenced the development of the “ethos” or “spirit” or mentalité of modern European capitalism, in ways that distinguished it from earlier forms of capitalism.6 Weber and Tawney both agreed that Calvinism (ultimately) played such a role by the socio-psychological consequences of its three essential doctrines or components.

The first is the doctrine of predestination, which in essence stipulates that God, being omnipotent, determines (has determined, will determine) who are the very few to be the so-called Elect: those who shall enjoy eternal salvation with God. All the rest of mankind, because of original sin and free will, have and will have condemned themselves to eternal perdition in hell, and thus they are completely incapable of gaining salvation on their own.7 Even for the most devout of faithful Calvinists, such a bleak doctrine must have seemed unpalatable, indeed horrifying. But Calvin scorned those who sought to find positive signs of their Election, replying that to do so was inherently sinful. A century or so later, however, that strict Calvinist view could and did no longer prevail: perhaps because of pressure of public opinion in predominantly Calvinist lands (see Pettegree, Duke, and Lewis 1994; Riemersma 1967; Little 1969), and perhaps because of the evolving impact of the other two doctrines of this Calvinist triad: in Weber's terminology, the “calling” and “worldly asceticism.”

The doctrine of the calling was also based on the principle of God's omnipotence, so that obviously the world existed according to his will, as he had ordained it; and thus it was the duty of every man and women to serve God by fulfilling his or her calling—in whatever honorable (nonsinful) occupation one had gained—to exercise his or her utmost ability, in order to achieve the greatest possible degree of success in doing so.8 Calvin himself had been trained as a lawyer, and deemed that to be an honorable calling, as were not only those of other professional persons (e.g., doctors, professors, theologians), but also businessmen, and thus entrepreneurs. Indeed that list implicitly includes merchants, financiers, industrialists, retailers, storekeepers, and also industrial craftsmen or artisans, all so necessary for the maintenance and prosperity of a well-ordered civil society.

For many businessmen, what better, more tangible sign of success in one's calling could be found than profit? That meant profit maximization, which surely is the very essence of modern microeconomics. As so many came to believe, such proof of success in one's calling should also mean a positive, indeed certain, sign of one's Election. In turn, to the extent that so many in Calvinist societies came to equate such success in their calling with Election, that society in turn came to view such success, and success in profitable business enterprises in particular, with far greater approval, as a socially desirable goal, than ever before, in medieval society.

Nevertheless, by the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, an individual entrepreneur or businessman's success in his calling, when measured by profits (or “the bottom line,” as many would say today), was strictly conditional on how that person utilized those profits, in terms of the Weber-Tawney concept of “worldly asceticism.” If profits were spent largely on “conspicuous consumption,” such an individual risked incurring social opprobrium: that is, for worshipping Mammon,9 and not God. If consuming profits in this fashion was sinful, then the obvious and most laudable alternative—both socially and theologically—was to reinvest those profits in the business enterprise: that is, to increase the capital stock and scale of the enterprise, better enabling the entrepreneur to innovate and to increase subsequent profits, and thus better able to be dedicated to one's calling, for the greater glorification of God.

The Weber-Tawney thesis has, of course, engendered an enormous amount of debate from the 1920s, continuing to the present day; and a reexamination of that debate would serve no useful purpose in this study.10 In my own view, whether or not the Weber-Tawney thesis has any real significance for the history of entrepreneurship in England, and for the evolution of a more truly “capitalist” economy, the relevance will be found not in “Tawney's century” itself—when so many Calvinists seemed to be hostile to capitalism (and usury)—but rather in the succeeding century, 1640–1740.11

First, during the era of the English Civil War, Commonwealth, and Cromwell's Protectorate (1642–59), Calvinists—both Puritans and Scottish Presbyterians—played a very major role in winning that war against the Crown and the Cavalier or royalist factions; and furthermore, in then governing England during the Commonwealth-Protectorate era and in altering the nature of the established Church of England.12 In 1659, the year after Cromwell's death, the army terminated the Protectorate of his son Richard, and then forced the dissolution of the Long Parliament. The new parliamentary Convention that replaced it in April 1660 then invited Charles II (1660–85) to resume his throne.The ensuing Restoration Parliaments enacted two statutes to rid England of any Calvinist, and therefore Republican, influences within the English church and governments (national and local): the Corporation Act of 1661 and the Test Act of 1673.13

Together these statutes required anyone seeking to hold any church or government-related position (including the army, local justices, education, etc.) to swear oaths to conform to the Thirty-nine Articles of the Church of England and to take communion annually within the established church. As noted earlier, those Protestants who refused to do so were thus known as Non-Conformists or Dissenters. Along with Calvinists and Presbyterians, this group included such other Protestant sects as Baptists, Quakers, Unitarians, and later the Methodists.14 When, however, the Catholic King James II (1685–88) was deposed in the Glorious Revolution, his successors, his daughter Mary II (1689–94) and her husband the Dutch prince William III of Orange (1689–1702), insisted that Parliament protect the religious rights of his Calvinist coreligionists, in the Toleration Act of 1689 (not including Catholics or Unitarians).15 That act did not, however, annul the provisions of the Corporation and Test Acts, so that Dissenters remained barred from all the aforementioned government, and government-related and church-related, positions and schools.

Do these sociopolitical events and circumstances themselves explain why Dissenters came to play such a vital and clearly disproportionate role in the ensuing age of the Scientific Revolution (from 1660) and then in the Industrial Revolution era itself? Or should the answer be sought in the socio-psychological evolution of Calvinist Protestantism, as indicated in the Weber-Tawney thesis? Or are there yet other, alternative if complementary explanations?

Certainly one obvious explanation for that disproportionate role, to be sought in the first hypothesis, is the Dissenters' minority status: yet one without the burden of true oppression, in enjoying that “halfway” house of full religious but only partial social toleration. Thus their obvious challenge. Finding themselves excluded from the normal avenues of wealth, power, and social prestige, now available only to members of the established Church of England, the Dissenters instead sought to succeed and prosper in alternative avenues that did remain open to them: namely, in the worlds of business enterprise, commerce, finance, and industry (but also commercial agriculture). Perhaps they also experienced a deep psychological compulsion and social drive to prove themselves, both in their own eyes and in the eyes of society: so that such minority status did not mean inferior social status.

Another explanation, one that T. S. Ashton has offered, is “the fact that, broadly speaking, the Nonconformists constituted the better educated section of the middle classes,” which was chiefly due to the role of the so-called Dissenting Academies (1948, 19). They were the educational institutions that the Dissenters had been forced to establish, after having been barred from the traditional church- and state- sponsored schools and universities. Many of these academies were modeled after Scottish Presbyterian schools, which, in Ashton's view (endorsed by many others), were “in advance of that of any other European country at this time,” as were Scottish universities.16 Such schools focused upon or emphasized mathematics, the physical and biological sciences, and modern languages (English, French, and German especially). Also included in the curriculum were such practical subjects as accounting, surveying, and engineering. Necessarily eschewed—if only on grounds of opportunity cost—were the traditional subjects long favored by Church of England schools, “public” (i.e., private), and state grammar schools: Greek and Latin language and literature, philosophy, theology, and history. Even if history and Latin were also taught in the Dissenting academies, they were not taught within the same framework (theological) and emphasis; for indeed many Dissenters viewed Latin with some suspicion as still the fundamental language of the Catholic Church.

In Ashton's view, and certainly in the view of many other historians, the education offered by the Scottish schools and the English Dissenting academies was one more in tune with the objectives of the post-1660 Scientific Revolution and then of the British Industrial Revolution, and one more likely to inspire profitable innovations and entrepreneurship in both. Nevertheless, this Ashton thesis does not really tell us why these schools were so different from and better than the traditional schools: why in particular they were so much oriented to the worlds of science and business. One answer may be that those designing the curriculum in the Scottish schools and Dissenting academies were not encumbered by centuries of tradition and church-sanctioned and aristocratic social requirements. Another may be market demand: most of the students came from predominantly middle-class families that were then involved in the world of business, commerce, finance, and engineering.

Even to the extent that both explanatory models are valid, they do not permit us to discard the essence of the Weber-Tawney thesis, in particular the subsequent ways in which English society, in the later seventeenth, eighteenth, and early nineteenth centuries, came to interpret the Calvinist doctrines discussed above. For a better historical perspective, let us recall that in France, in 1685—just four years before William III's Toleration Act—King Louis XIV had revoked the Edict of Nantes, which Henry IV (a Calvinist forced to convert to Catholicism to gain the throne), had promulgated in April 1598, in order to grant full religious rights and full civil liberties to France's Protestant Huguenots, thereby ending the country's horribly divisive and destructive Wars of Religion (1562–98). The revocation of the Edict of Nantes soon led to the expulsion or emigration of a high proportion of the nation's Huguenots, many of whom were, like the Dissenters, disproportionately active in trade, commerce, and banking.17 While many refugee Huguenots fled to Protestant Holland and Protestant German states, some also came to England, where they made valuable contributions to the growth of the English business community, in trade and banking in particular (see Crouzet 1991).

Stanley Chapman, in his impressive monograph Merchant Enterprise in Britain(1992), provides much additional supporting evidence for the unusual economic and social role of the Dissenters in the Industrial Revolution era, stressing in particular the importance of their international mercantile connections with coreligionists abroad (especially in the American colonies), indeed the vital importance of both their family and religious ties for providing the necessary trust involved in “the transmission of credit and trading reports.” For all economic transactions involving principal-agent relationships—perhaps accounting for the majority of economic transactions in European economic history—have vitally depended on trust and confidence between all participants, in order to obviate the high transaction costs of enforcing agreements and monitoring a multitude of activities. Certainly, most economists would quickly recognize the importance of principal-agent relationships that were based on both knowledge of and trust in those with common religious, social, and business activities, and a common need of coreligionists and family members to unite for protection against hostile forces. Or as David Landes has so cogently and pithily observed: “In banking [and trade], connections count.”18 Finally, Chapman contends that economic ideology played almost as important a role in the striking mercantile success of the Quakers and Unitarians in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (1992, 43–47).

There are, of course, many other possible or hypothetical relationships between Protestantism and the development of modern forms of capitalism and of capitalist entrepreneurship in particular that have concerned a wide variety of historians and sociologists, but cannot be considered in this study.19 That question of relationships includes a deeper sociological analysis of the Protestant “work ethic,” which pertains as much to artisans, tradesmen, and professionals, as to entrepreneurs. One other possible relationship, and a major difference between Protestantism and Catholicism, that has not been so well studied is the question of confession and guilt. Well known, of course, is the power and prevalence of the Catholic confessional, in which the penitent, in confessing his or her sins by the sacrament of penance, to a hidden priest, receives absolution or formal remission of sin: that is, forgiveness and thus the (temporary) removal of guilt. Protestants had and have no such confessionals, and no such absolution and thus no such removal of the stain of guilt. To what extent were Protestants, and not just Calvinists and other Dissenters, motivated to achieve success in order to absolve themselves of guilt—not so much guilt for actual sins committed but guilt for not living up to their ingrained ideals, including those of the Protestant “work ethic”?20

Protestants in England's Glorious Revolution and the Ensuing Financial Revolution

Finally, any analysis of the relationship between Protestantism and capitalism, and the role of the Dissenters, in the century from the end of the Civil War and Cromwell era to the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution, must also be seen in the context of major constitutional and institutional changes. Those were principally the product of the aforementioned Glorious Revolution: the overthrow of King James II (168588), and his replacement by Mary II and her Dutch stadhouder husband William III of Orange. Well known is the 1989 article of Douglass North and Barry Weingast on the consequences of this Glorious Revolution. Those consequences included not just the quasi-religious freedom offered by the Toleration Act of 1689, but more so the final establishment of the supremacy of Parliament—of the House of Commons over finances. That in turn also brought about the establishment of judicial independence and the rule of law and property rights, as much in the market economy—greatly reducing transaction costs (as defined by North)—as in the political sphere and civil conduct. The most specific and immediate example was the 1689 Bill of Rights, establishing the rule of law over royal supremacy.21

Perhaps of equal importance, especially for this study on entrepreneurship, is what the British still call the Financial Revolution, whose chief institutional features were clearly imported from William's Dutch Republic (The United Provinces).22 That led to the establishment of a permanent funded national debt—the responsibility of Parliament, not of the Crown—based on the government's sale of fully negotiable perpetual annuities (Dutch renten), traded on the London and Amsterdam stock exchanges, and financed by the levy of excise (consumption) taxes authorized by Parliament.23

Any such seemingly radical reinterpretation of economic history, on critical “turning points,” has naturally and recently provoked a considerable reaction in the periodical literature (see Sussman and Yafeh 2006; Stasavage 2003, 2007). Though I do not believe that the critics have succeeded in negating the North-Weingast thesis, the nature of this study on British entrepreneurship, along with lack of space, precludes any further analysis of this debate, except to note one relevant point: the relationship between a major religious issue, for Protestants as well as Catholics—the usury doctrine, and the origins and nature of the Financial Revolution.

As I have contended elsewhere, those origins lie in the vigorous resuscitation of the antiusury campaign in the early thirteenth century, following the Church Council Lateran IV, in 1215, and the contemporary establishment of the two mendicant preaching orders—the Franciscans and Dominicans—preaching hellfire and damnation for those guilty of the mortal sin of usury: both for those who exacted and those who paid any interest on a loan. There is considerable evidence that, from the 1220s, in many towns in northern France and Flanders, more and more merchants and financiers, fearing such damnation, preferred to accept much lower returns on annuities (rentes, renten) purchased from urban governments than the far higher interest rates that they would have earned on loans or debentures. As the papacy soon determined, as early as 1251 (Innocent IV), the rente or annuity was not a loan, and hence not subject to the usury doctrine, because the purchaser had surrendered his capital in perpetuity to the seller, and thus had no right to redeem or reclaim his investment, while the seller could later choose to redeem the annuity at par. By the sixteenth century, the sale of annuities (rentes) was displacing loans as the predominant form of public borrowing in western Europe: thus, providing the precedents for England's own Financial Revolution (Munro 2003a, 2008c; Tracy 1985, 1995, 2003).

The relevance for seventeenth-century England is simply the fact that most Protestants had continued to be as hostile to usury as most Roman Catholics had been, and probably even more so. We have been led to believe, however, that after Elizabeth I's Parliament of 1571 had amended the usury laws to permit interest up to 10 percent—so that henceforth usury came to mean any interest charges above that limit—public hostility to “normal” interest waned. But such a view is far from the truth. Even Elizabeth's statute used hostile language in stating (in an almost contradictory fashion) in its preamble that “all Usurie” was “forbydden by the lawe of God.”24 In fact, Elizabeth had merely restored her father's statute of 1545 (Henry VIII), which had then been repealed under the even more Protestant regime of Edward VI, in 1552: “Usurie is by the worde of God utterly prohibited, as a vyce moste odyous and detestable.”25

Furthermore, John Calvin (1509–64) and Martin Luther (1483–1546), the two major initiators and leaders of the Protestant Reformation, did not really have the more liberal views commonly attributed to them on the usury issue. Only grudgingly did these religious leaders accept interest payments: but only on investment loans and only to a maximum of 5 percent.26 Calvin himself clearly voiced his disapproval in stating that “it is a very rare thing for a man to be honest and at the same time a usurer.”27 He had also contended that all habitual usurers should be expelled from the church (Noonan 1957, 365–67); and indeed in Holland, the Calvinist synod of 1581 had decreed that no banker should ever be admitted to communion service (Parker 1974, 538). Subsequently, in the seventeenth century, an English Puritan minister observed that “Calvin deals with usurie as the apothecarie doth with poyson”;28 and early in that century the renowned Sir Francis Bacon (1561–1626) had contended that “Usury is the certainest Meanes of Gaine, though one of the worst.”29 According to Richard Tawney, the English Puritan clergy continued to preach against the “soul-corrupting taint of usury” to the very eve of the English Civil War (Wilson 1925, 106–34, esp. 117; Tawney 1926, 91–115, 132–39, 178–89).

It is thus important, in the early-modern history of usury laws and the origins of England's own Financial Revolution, to note that, although Elizabeth I had set the maximum interest rate at 10 percent (1571), subsequent Parliaments lowered that legal maximum, evidently in accordance with the long-term decline in real interest rates: to 8 percent in 1623, to 6 percent in 1660, and finally to 5 percent in 1713, the rate that continued to prevail until Parliament finally abolished the usury laws in 1854.30 Hence another point of significance about England's Financial Revolution, in establishing its own permanent funded national debt: it was entirely based on annuities, and not on loan instruments (bonds and debentures), and thus it was also fully exempt from these usury laws, with such a low legal maximum.31 One indication of the success of the Financial Revolution was the fall in the interest rate on government borrowing from the 14 percent return on the Million Pound Loan of 1693 (in fact a lifetime annuity, marking the inception of the Financial Revolution) to the 3 percent return on consols in 1757, with the completion of Pelham's Conversion.32

That reduced considerably the extent to which government borrowing, principally to finance warfare, “crowded out” capital investments for private enterprise; and the fully negotiable consols themselves provided British entrepreneurs with an exceptionally valuable form of collateral in borrowing capital, both working and fixed capital.33 Few entrepreneurs were and are able to survive without borrowing at some time in the development of their business enterprises.

Tawney's Thesis on “Agrarian Capitalism” and the “Rise of the Gentry” Debate

Tawney had first achieved academic fame, not with Religion and the Rise of Capitalism, but much earlier, in 1912, with his study on the enclosure movements and the evolution of “agrarian capitalism” in Tudor-Stuart England: The Agrarian Problem in the Sixteenth Century. Subsequently, almost three decades later, in 1941, he achieved even greater fame, but then trenchant opposition, opprobrium, and misfortune, with his famous article on “The Rise of the Gentry.” His goal was to explore both the social and economic origins of the English Civil War, and also of modern capitalism. In his view, the English gentry were or largely became agrarian “capitalists,” who were imbued with an entrepreneurial spirit and profit-maximizing motivations, far more so than typical members of the traditional, military-oriented, aristocracyy—or, more properly speaking, the peerage: that is, dukes, archbishops, marquesses, earls (= European counts), viscounts, and barons.

The term gentry has to be understood as a unique English social institution, in its relation to the genuine aristocracy.34 For the English aristocracy differed in many important respects from continental forms. In the first place, only the eldest son, by the law of primogeniture, inherited the noble or aristocratic title, along with the attached estates, and thus the right to sit as a peer in the House of Lords. All other offspring were commoners under law (even if having a lifetime courtesy title of Lord), while on the continent they would have been considered members of the aristocracy. Therefore, many members of the English gentry were the younger sons and relatives of these peers; and consequently—as Tawney was really loathe to admit—they were generally indistinguishable economically, socially, and politically from the peers. Certainly they were not a separate social class. Furthermore, while all knights (cavalry horse soldiers) were considered to be aristocrats on the continent (noblesse d'épée), they were all legally commoners in England; and they were also the major component of the House of Commons in medieval and early-modern England. The English gentry also consisted of those second-generation gentlemen farmers whose fathers—often of bourgeois or even yeomen origins—had purchased manorial estates and who then bred their children to emulate the lifestyles of a lesser landed nobility, though without (in Tawney's view) losing their bourgeois acquisitive and entrepreneurial instincts.35

Tawney's thesis begins again with the question of Protestantism: namely, Henry VIII's break with Rome to establish an independent Church of England, in 1534 (Act of Supremacy), a break that was solidified with the dissolution of the monasteries in the years 1536–41. Initially, most of the monastic lands, accounting for perhaps 20 percent of the developed arable lands of England, were either given as rewards or sold to Henry's aristocratic supporters—to ensure that they would support him against Rome. But during the following century—from 1536 to the outbreak of Civil War in 1642—about 90 percent of those monastic lands (according to most estimates) passed into the hands of the gentry.36

In Tawney's view, the economic mechanism that lay behind this vast transfer of land to the gentry was the Price Revolution: in particular the variety of responses to this long sustained inflation, commencing just before 1520 and lasting until the mid-1650s.37 Tawney contended that the traditional feudal aristocracy were suffering from three related problems during the Price Revolution era. First, most aristocrats' estates were in the form of hundreds or more manors scattered across not just England, but across the British Isles. That scattering made estate management very difficult to undertake, all the more so since much of their estate income was in the form of fixed feudal dues and relatively fixed (nominal) rents for both freehold and copyhold peasant tenures. Consequently, their estate incomes did not rise with inflation.

The second problem was that many of the aristocracy were still imbued with a feudal mentality that scorned any thought of commercial estate improvements and profit-maximization—certainly not any form of “agrarian capitalism,” as Tawney envisaged it—and also any thought of seriously disrupting the lives of their tenants, many so loyal to their lords over many generations. The third and related problem was that their political, military, and social statuses, so necessary to maintain their aristocratic rank, were becoming increasingly expensive to maintain, especially when many such costs—chiefly military and court services—were rising faster than the consumer price index, or the overall price level.38

Whether all or most of these factors were really true of the Elizabethan aristocracy, clearly many did opt for the line of least resistance in coping with inflation: namely, to live off their capital by selling lands, especially recently acquired lands that were not governed by aristocratic estate entails. That meant chiefly their lands of monastic origin, though many aristocrats were also finally forced to sell patrimonial estate lands as well. The Tudor and early Stuart monarchs were similarly forced to sell off crown lands, for the very same reasons.39

Many of the gentry, on the other hand—again, in Tawney's view—did not face such enormous demands on their time and energies. Furthermore, in having far smaller estates, often with only a few manors, they had a commensurately greater ability to engage in rational estate management, and indeed to engage in the enclosures that became so prominent in Tudor-Stuart and Hanoverian England, so that by the early eighteenth century about 70 percent of the cultivated arable land of England had been enclosed.40 Such enclosures eliminated communal peasant tenancy rights and permitted the engrossing or amalgamations of the scattered plow strips constituting the former peasant tenancies into compact farms under single unified management, whether undertaken by the landlord himself or by his tenants, who leased lands at market rentals. That allowed both gentry landlords and their major tenants, now freed from peasant property rights and their communal constraints, to engage in the New Husbandry, most of which was imported from the Low Countries. Thus much of the gentry, whether they managed their own estates, as capital farms, or let their enclosed lands to tenant farmers, on relatively short-term leases, were able to capture much more of the economic rent (Ricardian rent) that accrued with the steady rise in the real values of most agricultural commodities—economic rents that would otherwise have been captured by those freehold and copyhold tenants enjoying fixed, nominal money rents.

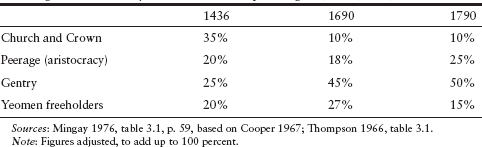

What is the current evidence for the extent of such land transfer? According to statistics from various sources (unavailable to Tawney), presented in table 5.1, the gentry's share of English arable lands rose from about 25 percent in 1436—thus indicating that the gentry had already “risen” long before 1536—to 45 percent in 1690, and to 50 percent by 1790.

Those gentry gains, up to 1690, appear to have come chiefly from the Church and the Crown, whose share fell from 35 percent in 1436 to just 10 percent in 1690, while the shares for the peerage (aristocracy) fell only from 20 percent in 1436 to 18 percent in 1690. But these figures are highly misleading, in not revealing that a considerable proportion of aristocratic land holdings in 1690 consisted of estates that were held by many former gentry who had acquired peerages after 1660 (when the ranks of aristocrats had been seriously depleted, for various reasons). As this table indicates, and as H. J. Habakkuk had contended, they undoubtedly provided a major reason why this rejuvenated aristocracy, so vastly different from that of the Elizabethan era, was able to regain its share of land holdings to about 25 percent, a century later, in 1790. Note, from this table, that the gains in both aristocratic and gentry landholdings, from 1690 to 1790, came chiefly at the expense of yeomen freeholders.

We should not assume that these new peers had shed their former gentry customs, culture, and socio-economic and especially entrepreneurial outlooks. Indeed, many of them—such as Norfolk's Second Viscount Charles Townsend of Rainham (1675–1738), known as Turnip Townsend—were major proponents and practitioners of the New Husbandry.41 Of course one can find many variations, with some gentry who failed as capitalist farmers, or those who simply failed to engage in rational estate management, and contrary examples of some aristocratic landowners who did cope with inflation and prospered—though most such examples are really found among the aristocracy of gentry origins, in the post-Restoration era.

In general, the Tawney thesis on the “rise of the gentry”—even if the gentry had risen long before Tawney's century—deserves more support and credit than most istorians seem willing to grant it. For unquestionably, Tudor-Stuart England did experience the transfer of a vast amount of productive lands into the hands of those more likely, more able, more willing, and certainly more predisposed to engage in rational estate management, and other commercial enterprises, indeed to engage in entrepreneurial profit-maximization.42 Furthermore, as Tawney and many others have noted, a high proportion of these gentry, especially in the seventeenth century, were Puritans—the most renowned example being Oliver Cromwell himself (see Cliffe 1984, 1988).

TABLE 5.1

Percentage of Land Held by Various Social Groups in England, 1436, 1690, and 1790

The extent to which at least a significant number of the English gentry and their major leasehold tenants did become or act as genuine “agrarian capitalists,” employing significant innovations in market-oriented mixed husbandry (i.e., combining the cultivation of grain and other arable crops with livestock raising, both sheep and cattle), with the aim of maximizing profits, has yet to be fully explored. But consider, for example, the ingenuity and entrepreneurship of the Herefordshire gentleman farmer Roland Vaughan, who, in 1589, invented and then popularized the “floating meadow” (or water meadow). This capital-intensive innovation involved the use of sluice gates, dykes, and canals to divert water from streams or rivers to flood the meadows or parts of the arable in November, and then to drain them in March. That provided a thermal blanket, under the ice, to protect the underlying soil from freezing and to promote far earlier and more intense germination, yielding as much as an eightfold increase in hay production.43

Certainly the very character of English agriculture did change dramatically from this period, especially with the far more widespread diffusion of convertible husbandry, which led to major increases in agricultural productivity. In essence, convertible husbandry meant the alternation in the use of agricultural land between arable and pasture (as opposed to the previous regime of permanent arable and permanent pastures) over a cycle of five or more years, the cultivation of a wider variety of crops, including far more powerful nitrogen-fixing legumes (clover, alfalfa-lucerne, sainfoin), other fodder crops, and industrial crops, thereby eliminating the need for fallowing parts of the arable. It also provided far more efficient pastures and thus a far more productive form of livestock raising. That in turn vastly improved livestock feeding (with more fodder crops from the arable) and the size of cattle and sheep herds. Equally important, enclosures and convertible husbandry also permitted selective breeding of livestock, which had been virtually impossible with the previous communal grazing system of open field peasant agriculture. Convertible husbandry became the very heart of the later so-called Agricultural Revolution, in providing the most efficient and productive form of agriculture before the advent of modern chemical fertilizers.44

The greatest and most widespread diffusion of convertible husbandry, especially with the cultivation of the new legumes, came during the period of an agrarian recession, from the 1660s to the 1740s, when the behavior of relative prices promoted a shift from grain growing to fodder and industrial crops, and especially a much greater shift to livestock products. At the same time, a fall in grain prices, while wages and other farm costs were rising, created a price-cost squeeze, which in turn provided a strong incentive for farmers to increase efficiencies per unit of labor and per acre of land. Convertible husbandry, along with the introduction of floating meadows, required very large infusions of capital, which were generally obtained by mortgaging enclosed lands; and mortgaging was also virtually impossible to undertake with communal peasant open field farming. Those landowners and tenants-in-chief who did engage in mortgage financing, and those who succeeded in vastly increasing rents and profit margins, certainly were entrepreneurs, in any sense of the word, and well deserve to be called agrarian capitalists.45

One may cavil, however, that while many such gentry did become, in Tawney's terminology, genuine agrarian capitalists and were responsible for promoting important innovations in agricultural productivity, such developments are not really relevant to a study on entrepreneurship—even if they did promote English economic development. The proper response is that the Tawney thesis on agrarian capitalism is highly relevant, in two respects, if we may now draw on the wisdom of Joseph Schumpeter (1883–1950).

Schumpeter on Entrepreneurship

First, many of us who have written on this theme have been inspired by the work of Schumpeter: especially his classic essay on this subject, but also his many other publications.46 His views on the historical development of entrepreneurship do not seem to be confined merely to the worlds of industry, commerce, and finance. In my view, he would have implicitly accepted Tawney's “agrarian capitalism” (if he accepted the thesis itself) as an integral part of the evolution of modern entrepreneurship. Indeed, his definition of entrepreneurship is exceptionally broad: that which succeeds in “transforming or combining factors into products [and services].” Schum-peter comments further: “If there is not necessarily any sharp dividing line between entrepreneurial activity and ordinary management,” nevertheless, “the distinction between adaptative and creative response to given conditions may or may not be felicitous, but it conveys…an essential difference.” For Schumpeter, an apt synonym for an entrepreneur is a business innovator—someone who proves successful in introducing and maintaining productive and profitable economic changes in his or her enterprise. Especially important for this study is Schumpeter's view that “the entrepreneurial function need not be embodied in a physical person or, and in particular, in a single physical person” (Schumpeter 1949, 254–55).

Certainly in this study one basic objective is an investigation of the economic, social, and cultural forces that induce profitable innovations as the key to economic growth. A related objective is to demonstrate that innovations, especially technological innovations, have been fundamentally the products of capitalist entrepreneurship, in all four key sectors of the economy, including agriculture. Above all, we must always be clear in distinguishing between mere inventions—many of which were never successfully applied in their day (e.g., Hero of Alexandria's steam pump, of circa 60 CE)—and entrepreneurial innovation: the successful, productivity-increasing, and profit-maximizing application of new techniques and new technologies in some business enterprise, including agricultural enterprises.

Another justification for examining the role of the early-modern English gentry in such entrepreneurial innovations is simply the long-accepted fact that many gentry landowners did not draw even the greater share of their incomes from leasehold rentals. Nor did they confine their enterprises to agriculture. For they also invested in mining, metallurgy, and textiles. We must remember that many capitalistic industrial enterprises—in mining and metallurgy especially—were necessarily found on gentry estates; and much of the capital investment in these enterprises came from gentry landowners, for clearly they had a disproportionate amount of the nation's wealth to make such investments (see in particular Simpson 1961). The extent to which they financed and promoted or engaged in English industrial development in the early-modern era is yet another avenue of research that needs to be more fully explored, despite several important recent studies.47 Even more important would be a fully-researched historical analysis of those gentry, and especially the well-educated and the socially, economically, and politically well-connected sons of gentry who became successful, profit-maximizing entrepreneurs in business itself, as usually the term is understood: in industry, commerce, and finance.

The Hamilton-Keynes Thesis on Profit Inflation and the Rise of Industrial Capitalism during the Price Revolution Era, and the Gould Alternative

Pre–World War II scholarship on economic issues in Tawney's century (1540–1640), especially those involving the Price Revolution, includes two other scholarly names, once renowned, if not so much today, for clearly neither had Tawney's intellectual caliber. Yet both remain important for raising very important issues for any scholar analyzing the origins of early-modern industrial capitalism and related issues of capitalist entrepreneurship. We simply cannot dismiss them for supposed defects in their scholarship, if they did succeed, in this fashion—that is, by investigating such critical issues—in promoting our understanding of the evolution of early-modern English entrepreneurship, and industrial capitalism.

The first was Earl Hamilton (1899–1989), professor of economics at Chicago (1949–69), and President of the Economic History Association in 1951–52. His chief claim to fame in economic history is in providing some statistical foundations for an explanation of the inflation of the European Price Revolution era based on a quantity theory of money, in many publications, from 1928 (Hamilton 1928, 1929a, 1929b, 1934, 1936, 1942, 1947, 1952). Since the time of the French philosopher Jean Bodin (1566) a majority of scholars had in fact assumed that the primary cause of the Price Revolution was the influx of silver from the Americas (Bodin 1946; Wiebe 1895). That inflation had in fact begun much earlier—in Spain, England, the Low Countries, Italy: from at least the 1520s, long before any significant amounts of Spanish-American silver had arrived in Europe. Some economic historians, on discovering this fact, unfortunately leapt to the false conclusion that the true, fundamental cause of this inflation was instead population growth. In fact the initial causes were monetary, but in the form of the south German–central European silver mining boom (ca. 1460–ca. 1550) and a financial revolution in the 1520s, issues that need not detain us here, except to note that Hamilton himself had also perceived the importance of these two issues, and did not (contrary to popular opinion) contend that the influx of American silver provided either the initial cause of the Price Revolution or the predominant cause of Spanish inflation during its final phase, in the first half of the seventeenth century.48

Hamilton's second claim to fame, and the one far more relevant to the theme of this study on entrepreneurship, was his 1929 thesis that the inflation of the Price Revolution was fundamentally responsible for the birth of modern industrial capitalism through the mechanism of “profit inflation.” In truth, Hamilton really owed his fame to the fact that the eminent economist John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946) had so strongly and publicly endorsed Hamilton's thesis; and indeed it was Keynes himself who actually coined the term profit inflation (in 1930).49

In essence, Hamilton and Keynes argued that in this era industrial wages lagged behind prices, particularly in England (but not so much in Spain), thereby producing growing profits, the bulk of which English entrepreneurs chose to invest in larger-scale, more capital-intensive forms of manufacturing industries and other industrial or commercial enterprises, for example, overseas joint-stock trading companies (see below).

To be sure, in England, as in many other European countries, nominal or money wages generally did lag behind consumer prices; and such a phenomenon can be found in many other eras as well (including the twentieth century). Unfortunately for Hamilton, however, he used wheat prices to measure the price level. From the 1950s, most economic historians have instead preferred to measure changes in the price level by following the model of Henry Phelps Brown and Sheila Hopkins: by constructing a weighted “basket of consumables” consumer price index. In their index, about 80 percent of the commodity weights consist of foodstuffs: wheat, rye, peas, barley, malt (for beer), butter, cheese, meat, and fish. The remaining 20 percent is in common industrial products: chiefly textiles and fuels.50 In all price indexes for this era, grain prices rose the most, by a very substantial degree, followed by those for wood fuels, and livestock. Prices for industrial manufactures did rise, as well, but by a far lesser degree. It is far from clear that in various individual industries prices of manufactures rose more than did the wages for those who produced them.

Under such circumstances, one may ask why English industrial entrepreneurs would have necessarily, by the Hamilton model, invested their supposed extra profits, if any, in larger-scale, more capital-intensive forms of industry, when labor had become relatively so cheap, and, in real terms, had become even cheaper. Furthermore, if the real wages of industrial labor had declined, from a rise in their cost of living, industrialists in general would have achieved market gains only if the real incomes of those engaged in other economic sectors–agriculture, commerce, and finance—experienced a more than compensatory rise. That was an important issue that neither Hamilton nor Keynes (nor indeed most other historians) ever really considered.

With the now better-observed long-term behavior of relative prices and wages in early-modern Europe, we may confidently assert that Hamilton and Keynes were not justified in contending that industrialists enjoyed any verifiable profit inflation. Indeed, no economic historian can make such a contention without measuring, industry by industry, the long-term relationships between industrial wages and the wholesale prices for the manufactures that wage-earning employees produced. For the later sixteenth- and seventeenth-century southern Low Countries, arguably then one of the most advanced industrial regions in Europe, I myself have found evidence for the very opposite of profit inflation: a rise in industrial wages (for building craftsmen) that was, overall, greater than the rise in the industrial price index. And yet that did not seem to impair the profits and fortunes of most industrialists and entrepreneurs in the seventeenth-century southern Low Countries (Munro 2002).

Whether or not, in this and other eras, inflation reduced the factor cost of labor in this and other sectors of the economy may seem to be an interesting if moot question. Yet this question raises two very important and more major issues: (1) what has been the historical impact of inflations and deflations upon all factor costs of production; and (2) how have industrial entrepreneurs reacted to such changes in their real factor costs: that is, have such changes proved to be yet another spur to entrepreneurial innovation?

One of the very few economic historians to explore this vital issue was John D. Gould, though regrettably without much success in affecting historical interpretations. In a now all but forgotten article, published in 1964, Gould contended that inflation generally reduced an arguably even more important factor cost: namely, the cost of capital. Thus, insofar as early-modern entrepreneurs had borrowed funds for capital investment by contracts that specified the payment of annual interest and finally the repayment of the principal, in current money-of-account terms, the inflation of the Price Revolution era had cheapened the costs of previously borrowed capital. Any contrary contention that lenders of this era—when annual rates of inflation were still low by modern standards—had responded by raising their interest rates is fully negated by abundant evidence that nominal interest rates were continuously falling in the sixteenth century (in Flanders, from 20.5 percent in 1511–15 to 11.0 percent in 1566–70), so that in fact, with inflation, real interest rates fell even further.51

Finally, we may observe that insofar as the Price Revolution did cheapen capital costs, it did so in ways that more directly promoted larger-scale, more capital- intensive forms of manufacturing industries. One may also argue that it similarly promoted larger-scale capital-intensive agricultural and commercial enterprises.

Perhaps, however, the real significance of the ill-formulated Hamilton thesis is that it provoked his colleague John Nef into producing an alternative thesis to explain the early-modern origins of genuine industrial capitalism in Tudor-Stuart England, and one that certainly involved rational if risk-taking innovative entrepreneurship.

The Nef Thesis Revisited (with Wrigley and Hatcher): The Tudor-Stuart Energy Crisis and an Early Industrial Revolution

John Nef's counterthesis on this same theme was that England experienced a veritable “energy crisis” in Tawney's century, 1540–1640, and one that entrepreneurs largely resolved (in Nef's view) in the form of an “early industrial revolution.” This “revolution” involved very significant industrial innovations, specifically important technological innovations in fuel consumption, and also necessarily in the form of far larger-scale and genuinely capitalist forms of enterprise.52

The traditional medieval and early-modern industrial economies had been fundamentally wood-based—for both fuels and construction. In Nef's view, the energy crisis took the form of soaring wood and wood charcoal prices, rising as much as or even more than grain prices, and certainly to a far greater extent than industrial prices. The implicit culprit was population growth. Indeed, as we now know (and better than Nef), the population of England and Wales well more than doubled in this era: rising from about 2.250 million in the 1520s to reach a peak of 5.773 million in the mid-1650s.53 That demographic expansion, combined with a disproportionate growth in urbanization, and a rapid growth in shipbuilding for overseas trade, led to a far more extensive deforestation than was experienced in any other region in northern Europe.

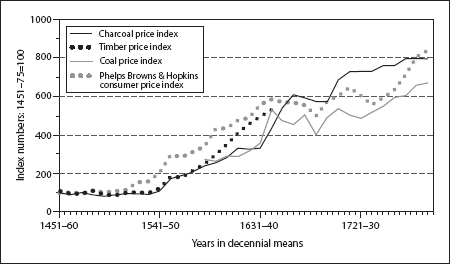

Furthermore, as Nef contended, England enjoyed a singular advantage over any other European region afflicted by a similar fuel crisis: in enjoying an abundant supply of readily accessible, relatively cheap coal, easily transportable by water (river or seaborne) in much of England. Thus a continuing divergence between wood charcoal and coal prices provided industrial entrepreneurs with a strong cost-price and profit incentive to shift from wood fuels, or wood charcoal, to coal. This contention subsequently, from the mid-1950s, aroused considerable, and generally very hostile, criticism from a wide variety of scholars.54

In this respect, two very important defects in Nef's analyses of fuel prices must be noted, though they were not defects that his opponents fully, clearly, and convincingly dealt with. First, as many opponents indeed noted, he made the absurd claim that England had suffered a “national” energy crisis during this century, when there were no national markets for wood, wood charcoal, or coal and when available evidence for some regional markets indicates often significant disparities in fuel prices. Nor could there have been any national market with such serious deficiencies in overland transportation and commercial facilities. Charcoal, it should be noted, was not a commodity that could then have been easily transported, chiefly because of its friable nature: that is, its physical instability, such that any agitation or disturbance causes the charcoal to crumble into unusable dust. Instead, in Tudor Stuart England, there were purely regional, local markets: in some such markets, wood remained abundant—and there charcoal was typically created at the forest site. In other regions, it soon became scarce and expensive, especially in relation to coal.

The other defect was to state, on the basis of insufficient data samples, that a serious divergence in charcoal and coal prices had already occurred by the later sixteenth century. My detailed comparative analysis of various sets of wood, charcoal, and coal prices in the same regional markets (see figure 5.1) indicates that, for a wide variety of such regional markets, the most marked divergence in relative prices did indeed take place—contrary to the assertions of some critics—but generally not until after the 1640s, when coal prices starting falling while charcoal prices (nominal and real) generally continued to rise.55 Nevertheless, for some specific local markets, such as Cambridge and Westminster, the price of a ton of coal was well under half the price of a ton of charcoal—when both had about the same calorific (heating) utility—indeed before the 1640s.56

If an industrial shift from charcoal to coal, purely on the basis of relative prices, were the only story to be told, it would not be worth serious consideration in a history of early-modern English entrepreneurship. The real interest lies in the entrepreneurial responses in the form of technological innovations, and consequent increase in industrial scales, that such a change in the choice of fuels necessitated: made necessary in the sense that without such innovations many industrial entrepreneurs would have faced failure and bankruptcies. The basic technological problem involved in choosing coal over wood charcoal lies in the fact that coal is a very dirty fuel that contaminates most products with which it comes into contact. Charcoal, conversely, is a form of pure carbon, and the purest of all available fuels, explaining its worldwide use over many millennia.

There were two possible solutions to the fuel contamination problem. For this early-modern era, the first and indeed only technological solution was the construction of a reverberatory furnace to separate the coal fuel, and its noxious fumes, from the manufactured product. The second solution, which came much later, only with the advent of the Industrial Revolution era, was the distillation and purification of coal, transforming it into coke. That process in turn proved successful only after long, arduous, and costly experimentations, which themselves reveal a true entrepreneurial spirit among many industrialists, in the course of the later seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.57

Figure 5.1. Price Relatives for Fuels (Wood, Charcoal, and Coal) and the Phelps Brown and Hopkins “Basket of Consumables” (Revised Version), 1451–60 to 1781–90, in decennial means. Base 1451–75 = 100 for all indexes.

The first solution, the reverberatory furnace, is first described in Vanoccio Birunguccio's De la pirotechnica, about 1540, though we do not know who were the original inventors or entrepreneurs, those who first succeeded in achieving this vital technological advance. It was a very large-scale and complex brick kiln furnace that transmitted heat by convection and reflection (“reverberation”)—reflecting heat from the roof of the furnace onto the product being manufactured, while isolating the coal fuel itself and the fumes by eliminating the chimneys and using underground pipes to exhaust the fumes and to draw in fresh air.58 This new furnace also required hydraulic machinery, with large water-powered leather bellows, in order to inject air into the burning coal fuels to achieve the required high levels of combustion. Such technologically complex furnaces obviously required a quantum leap in the scale of capital investment. That in turn meant a dramatic change from simple artisanal production to true industrial capitalism, employing not traditional artisans (owning their own capital), but wage-earning laborers, indeed factory workers.

Would this far more costly furnace technology have threatened the profit margins of the new industrial capitalists? Whatever their initial fears and expectations, the answer is no. For Nef's so-called industrial revolution in fuel technologies in fact entailed three separate sets of cost reductions. First, this new and very capital-costly fuel technology required a commensurately large increase in industrial scale, which in turn ultimately meant a sharp fall in the marginal costs of production. Those changes in scale economies, however, had to be based upon and justified by a very large increase in market sales, from both a general population growth and disproportionate urbanization (discussed below) and an expansion of the market economy itself with the requisite commercial-financial institutions (also discussed below). In other words, the success of this industrial innovation depended upon a large enough increase in production and sales to distribute the initially high fixed costs over the production run, so that unit costs fell. Second, industrial capitalists achieved gains in transaction, organizational, and labor costs by concentrating production in one centralized, factory-like unit. Third, of course, they benefited by substituting relatively cheaper coal for ever more costly charcoal, at least generally so from the 1640s. Nef's chief point, therefore, is that industrial entrepreneurs, facing this “energy crisis”—even if Nef misdated the real era of crisis—could have survived to prosper only by engaging in a technological change that in turn demanded radical changes in industrial and commercial organization, to achieve much larger economies of scale.

What examples of the new “industrial capitalism,” specifically for early-modern (later Stuart-Hanoverian) England, did Nef and other historians of the British coal industry, such as John Hatcher, provide? The chief examples are the following innovative industries: glass (perhaps the first such industry, ca. 1610),59 beer (brewing with hops), bricks, clay tiles, pottery making, lime-burning (construction and agriculture), soap, paper, gunpowder, brass wares, salt (seawater evaporation), alum and dyestuffs, sugar refining (post-1660). In the field of metallurgy, the new coal-burning industries included those of calcining ores (burning out impurities before smelting); copper-based industries, especially those making brass and bronze alloys; metallic processes in separating silver from lead; the final finishing of many metals, for example, in drawing wire or making nails. None of these was truly new, of course, in terms of the product, but rather in terms of industrial technology; and many did become important as import-substitution industries.

To reiterate the other key point: such industries could have been successful in achieving the necessary scale economies only if they had found sufficient mass markets to consume these products. Such was not the case for export markets, for none of these “new” industries was responsible for any significant exports (except a few industrial products exported to West African and American markets). They were far more successful in the domestic market: thanks to the aforementioned population growth. Although, as noted earlier, the population of England and Wales had reached a seventeenth-century peak of 5.773 million in 1656, and although that population thereafter did experience some decline and stagnation, it rose again from the 1720s to reach a level of 6.757 million in 1761, on the eve of the modern Industrial Revolution era. But far more dramatic and certainly far more important was the growth of London itself. Having been relatively insignificant in 1500, with a population of only about 50,000, it had grown to 200,000 by 1600, to 350,000 in 1650—when it had become indisputably the largest city in Europe—and to 550,000 in 1750. That provided a concentrated mass-market with much lower transaction costs from the very density of sales.60

Equally important was the fact that such products as glass, bricks, soaps, dyestuffs, beer, brass- and bronze-wares enjoyed significant price elasticities of demand, so that cost and then competitive price reductions ensured a more than proportional increase in the quantity demanded and consumed. The same effect was achieved, in this era of steadily rising real-wage incomes, from the 1650s, for those products that similarly enjoyed a high income elasticity of demand.61

Other major manufacturing industries of this era did not, however, enjoy any such changes and benefit from this new furnace technology. Woolen textiles, which collectively remained by far England's most important manufacturing industry, producing by far its overwhelmingly dominant exports until the eighteenth century (92.5 percent by value, to the 1640s), did not undergo any truly significant technological changes, not even with the rise of the so-called New Draperies, until the true Industrial Revolution of the later eighteenth century, that is, from the 1760s.62 Indeed productivity in the eighteenth-century woolen industry remained about the same as that documented for the fifteenth century (Munro 2003b, 1988).

Furthermore, England's other major and growing industry, iron manufacturing, proved to be unable to use the new furnace technology. Until the early eighteenth century, it remained fully dependent on charcoal (and also on water power). The technological reason for that is very simple: smelting iron ore requires the direct contact of the ore, as ferric oxide (Fe2O3), with the fuel, so that the carbon in the charcoal unites with the oxygen in ferric oxide to liberate the iron (Fe) while producing carbon dioxide: CO2. The initial solution to that problem, and at the same time, the previously indicated second solution to the overall “coal problem,” came in 170910 with Abraham Darby's development of coke fuels. That fuel was the successful result of distilling coal into coke in an airless furnace, as a virtually purified form of carbon.63 It did not, however, then produce an “industrial revolution,” because initially coke fuels were more expensive than charcoal fuels, and coke-smelting also required extra refining costs, to eliminate the silicon (which, however, improved the quality of cast iron). Coke-smelting became fully cost-effective and thus successful, indeed “revolutionary,” only with application of John Smeaton's piston air pumps (replacing bellows, ca. 1760) and then James Watt's steam engine to power them, in 1776. It should be noted that most of the trenchant opposition to the Nef thesis concerns his views—and those of T. S. Ashton—on the supposed “tyranny of wood and water,” in curbing the growth of early-modern iron industry. This is a story beyond the scope of this chapter, belonging to the study of the eighteenth-century Industrial Revolution.64

In summary, and in all these respects, it is fair to criticize the Nef thesis by contending that no industrial revolution took place in Tudor-Stuart (or even early Hanoverian) England: there was no significant growth of the industrial sector, whether in terms of outputs, exports, or employment. Furthermore, no significant transfers of labor and resources from the agrarian to the industrial, commercial, financial, and service sectors took place in either Tawney's century or the following century: none to compare with those of the later eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Nevertheless, we must not overlook the important fact that coal was assuming an ever greater role in the British industrial economy from the sixteenth to eighteenth century, well before the onset of the Industrial Revolution. John Hatcher has contended that “in the latter half of the seventeenth century, sweeping changes occurred in the pattern of industrial coal consumption,” so that “by 1700 coal was the preferred fuel of almost all fuel consuming industries, and access to coal supplies had already begun to exert a determining influence over industrial location” (1993, 450, 458). Even if the aforementioned textile industries did not, as noted earlier, undergo any significant technological changes in this era, certainly none involving power, nevertheless they also experienced a major growth in coal consumption for many of their industrial processes: from combing to dyeing to finishing; and in the production of dyestuffs and mordants (Tann 1973; Wrigley 1988, 78; Hatcher 1993, 442–44). Hatcher estimates that British coal output (England, Scotland, Wales) had expanded almost twelvefold: from about 227,000 tonnes in 1560 to about 2,640,000 tonnes in 1700, when it was supplying about half of England's fuel needs (1993, table 4.1, p. 68). Anthony Wrigley has furthermore observed that British coal output was then at least five times greater than the combined output in the rest of the world. By 1800,British coal output had expanded at least fivefold, to about 15 millions tonnes a year, which was at least five times greater than the aggregate coal output in continental Europe.65 By 1830, according to Michael Flinn's estimates, Great Britain was producing 30.861 million tonnes (34.024 million tons), almost twelve times as much as Britain had produced in 1700.66

The aforementioned rapid and dramatic growth in London's population itself had a major impact on the English coal-mining industry and trade, for that growth could have occurred only with and because of massive imports of coal, especially for domestic heating, chiefly by sea from Newcastle, into London. Certainly London could not have imported enough wood to supply the city's need for both domestic and industrial fuels. As Wrigley has pointed out, a ton of coal produces “about twice as much heat as the same weight of dry wood.” Furthermore, noting that an acre of woodland then produced only about two tons of dry wood a year, he contends that the heat produced by one million tons of coal (mined and seaborne) would have required one million acres of forested land.67

Coal, as so many historians have contended, became the essential core of European industrialization in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, both promoting and permitting very major technological changes, which, by their very nature, were also entrepreneurial changes.68 Indeed, Wrigley has put forward the seminal thesis that English economic growth and the Industrial Revolution both depended upon a shift from an “organic” (wood) to a “mineral”-based economy (coal).69 Coal, distilled into coke, replaced charcoal almost everywhere in metallurgy (amalgamating smelting and refining, with vastly increased scales of production); coal-fired steam engines ultimately replaced water-mills, while later coal-fired steam turbines produced a new and very cheap form of power in electricity. And finally, coal also subsequently, and much later, became the fundamental base for a new set of very innovative chemical industries that also constituted part of the so-called Second Industrial Revolution, especially from the 1870s.

In sum, and in retrospect, Nef had supplied the essence of a good case for explaining why England was the birthplace of the modern Industrial Revolution: its entrepreneurial, technological, and industrial primacy in using coal, as the essential ingredient for modern industrialization. But he seriously compromised his case by using poor data, and by exaggerating his claims of growing industrial output in Tudor Stuart England. Perhaps his most serious fault was one of chronology. To reiterate the primary thesis in this historical analysis of English entrepreneurship: the Nef thesis, and Tawney's theses as well, have a much greater validity for the century following Tawney's century—the century preceding the Industrial Revolution. Those innovative entrepreneurial developments in that century indeed do help us better to understand the nature of the forms of the ensuing Industrial Revolution, from the 1760s, especially, and thus obviate concerns about a temporal gap between Tawney's century and the Industrial Revolution.

Overseas Expansion and Changes in Commercial-Financial Structures

The Atlantic Ship

There remains, however, one further set of English economic and entrepreneurial developments in Tawney's century—actually beginning in the previous century, but in the Iberian peninsula—that demands our attention in this study: the age of overseas maritime exploration, colonization, and trade. That in turn ultimately brought about economic “globalization.” The combination of technological innovation and entrepreneurial ingenuity that physically and economically made this possible—indeed in a very major form of industrial capitalism for this early-modern era—was the development of the so-called Atlantic ship or full-rigged ship.70 Portuguese shipyards, responding to demands from those oceangoing mariners who had been unable to cope with the Atlantic trade winds off the African coast, had initiated this industrial and commercial transformation by copying and adapting the triangular lateen-sail rigging of the Arabic coastal ship, in fact, a very small boat, known as the dhow; but the result was a much larger ship (40 to 200 tonnes) known as the caravel, with correspondingly much larger masts. It was that lateen-rigging that provided the caravel with the maneuverability to cope with these Atlantic trade winds, and allowed Portuguese mariners, from 1434, to advance south of Cape Bojador (26° N), and thus to commence their commercial and colonial acquisitions along the West African coast, and ultimately to Asia (India and the East Indies) in a highly successful search for both gold and spices, with the aid of a much improved oceangoing ship.

Subsequently, some unknown Iberian shipyards made the next advance in ship rigging, perhaps in the mid-fifteenth century, by combining the large square canvas sails of the northern Hanseatic cogge—providing power and speed—with the caravel's lateen sails: a small lateen spritsail on the bow, the square sails in the middle, and a large lateen sail on the rear or mizzenmast. These full-rigged or Atlantic ships, better known as carracks and galleons, were much larger than the Portuguese caravels, expanding in size to 600 tonnes in the early sixteenth century and then to 1,500 tonnes by the 1590s. A major factor in that increased scale was the addition of naval artillery: up to fifty or sixty cannons, placed both on deck and below deck. It was this large, full-rigged, heavily armed ship that allowed Europeans to dominate the world's oceanic trade routes up to the nineteenth century. Indeed, it may be considered, along with Gutenberg's printing press (ca. 1450), as the most important technological innovation of the fifteenth century—certainly a marvel of European entrepreneurship.

Another major aspect of this new age of overseas expansion was, of course, the vast influx of Spanish American treasure, silver, especially, which did so much to fuel and promote the ongoing inflation of the Price Revolution era (see Munro 2003c). But surely the more important economic function and consequence of that vast influx was in providing Europeans with essential means of expanding their trade with Asia: all the more so, since silver generally commanded a higher value in relation to both gold and goods in Asia than in Europe. That in turn was the prime consideration in western Europe's subsequent achievement of economic globalization.

The Crises in English Trade with the Antwerp Market in the 1550s

If we date the beginnings of this new era of overseas expansion with Portugal's capture of the Moroccan port of Ceuta in 1415, and then with the Portuguese and Spanish acquisitions in Africa, Asia, the Atlantic islands, and the Americas, to, say, the 1520s, the English appear to have been remarkably slow to seek out these new overseas business opportunities. One reason may have been that English exports, once predominantly in the form of raw wool, were by the 1520s almost entirely in the form of woolen cloth—accounting (as indicated earlier) for at least 90 percent of the total value of all exports. Almost all of this export trade was directed to the cross-Channel port and market of Antwerp.

Indeed, the original “tripod” or three-legged foundation upon which Antwerp had gained its role as the preeminent commercial, financial, and industrial center at the dawn of the modern era, from circa 1460 to circa 1560, had consisted of first, English woolen cloths; then, south German metals (silver, copper), fustians, and banking; and finally, from 1501, the Portuguese royal staple for the spice trade from the East Indies. English cloth merchants, having been excluded from Flanders, the Baltic, and the Mediterranean, had found only this one available outlet, in the Antwerp market (the Brabant fairs), where German merchants avidly sought their woolens, and had them finished in the Antwerp region, as their chief return cargo, just as the Portuguese later sought south German silver, copper, and banking to conduct their new African and Asian trades (see Munro 1994, 1999).

The English cloth trade boom, from circa 1460 to 1552—almost entirely coinciding with the Tudor enclosure movement (then chiefly for sheep pastures—reached its culmination, followed by disaster, in the Great Debasement of 1542–52, which Henry VIII and his successors had undertaken to finance their wars. Then, in mid-1552, Northumberland's Protectorate government abruptly revalued the English coinage by 253 percent (a 3.5-fold increase in silver contents). The obvious consequence of this drastic revaluation was a sharp rise in the foreign exchange value of the pound sterling, and hence a sharp increase (if not fully proportional) in the overseas cost of buying English woolens, whose sales soon plummeted on the Antwerp market.71

Since the previous debasements had provided such a stimulus to cloth exports, the Antwerp market may have already experienced a glut, so that exports might have fallen even without the revaluation (though probably not as much). From 1546–50 to 1551–55, London's quinquennial mean cloth exports had fallen by 10.4 percent: from 123,780 broadcloths to 110,888 broadcloths; and in 1560s London's mean exports fell to just 85,952 broadcloths (an overall decline of 30.5 percent).72 By the end of that decade, the outbreak of the Revolt of the Netherlands (1568–1609) made Antwerp quite inhospitable to English trade. But long before those events, the English had already undertaken their new search for alternative trading ports, and that involved a radical change and transformation in business organization in the form of the joint-stock company.

The New Joint-Stock Companies of the Later Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries

The very first such overseas joint-stock trading company, the Muscovy or Russia Company, was established in May 1553, in the direct aftermath of the Antwerp crisis.73 It is also the first (historically verifiable) joint-stock company, a revolutionary new form of business organization.74 The founders of this new venture subscribed a capital sum of £6,000 through the sale of stock, that is, shares of ownership, with a par value of £25 (i.e., 240 shares). This capital was then invested, with additional expenditures of £4,000, in the purchase of three ships and trading goods. Two ships were lost in the ice of the White Sea en route to Russia (which then had no Baltic port); but the third, under Richard Chanceller, the expedition's leader, did reach Archangel. He successfully negotiated a trade treaty with Czar Ivan IV (“The Terrible”). On his return, Chancellor obtained a royal charter that incorporated the new company “as one bodie and perpetuall fellowship and communaltie,” with a monopoly on all trade with Russia and adjacent regions in Asia. By 1563, the capital stock had been increased to £33,600, with permission to call upon a further £60 from each of the 240 shareholders (i.e., an additional £14,400 to bring the total capital to £48,000).75