In the opening and the end game the chess player can fall back to a considerable extent on the labour of others.

In the middle game, however, you are on your own.

Very little clear-cut instruction can be given on this phase of the game, but there exists an extensive field of theory. A lot of this theory is based on personal preferences, but certain aims, and the means of achieving these aims, are endorsed by all authorities. It is with this field of accepted theory that we are concerned in this chapter.

A lot has been said already on the subject. Pawns and pieces established on, or controlling, centre squares also exert their influence on both wings.

Most pieces, we know, have greater scope when in the middle of the board. A knight posted on a central square can be transferred to any position in two or three moves whereas a knight on the edge of the board would require several moves to reach a vital point on the other wing.

As in warfare, the breakthrough in the middle is the most effective, the defence forces being split into two camps which, being to a degree interdependent, are the more easily destroyed.

A wing attack, even if successful, may not be decisive. In practice, however, the wing attack is the more common because, as a result of the necessity of central concentration in the early stages of the game, a deadlock is frequent here.

The vexed question of when and when not to exchange has been long encumbered by prejudice.

Be guided only by the position; if you are ahead in material, endeavour to force exchanges and so increase your strength ratio; if behind, avoid exchanges, particularly of queens, and remember that endings with bishops of opposite colours are very often drawn. Do not let favouritism affect your judgement: many otherwise good players admit to preferences for this or that piece and avoid exchanging even when to do so would be to their advantage.

Ask yourself the following questions when contemplating an exchange:

1. Am I ahead in material and well placed for the end game?

2. Which of the two pieces, mine or my opponent’s, is the stronger or likely to become the stronger?

3. Am I losing time by taking his piece off, and would it not be better to let mine be taken first?

Let the answers determine your course of action.

The importance of the pawn structure is difficult to overestimate. Pawns can be battering-rams for the attack, bulwarks for the defence; and they can also be grave liabilities in either.

Because of the great influence that pawn formations exert on the middle game, and to a lesser degree on the opening and end game, a comprehensive survey of their diverse functions and their merits and demerits is given. Again, generalization has been necessary, and the relative position of the pieces, material and temporal factors must also be taken into account.

A pawn is isolated if there is no friendly pawn on either of the two adjacent files. Because it cannot receive pawn support, an isolated pawn is weak.

Pawns are said to be doubled if there are two of the same colour on a file. Doubled pawns are unable to support each other and are particularly vulnerable to attack. Their value is relatively slight (one pawn is able to block two hostile pawns that are doubled). Doubled, isolated pawns are weaker still. Occasionally pawns may be trebled or even quadrupled on a file. Sometimes, however, doubled pawns can provide extra central control or open a file for a rook.

A passed pawn is one which is faced with no hostile pawn either on the same file or on one of the two adjacent files.

A passed pawn is a distinct asset, particularly in the ending, since it will command the attention of an enemy piece to restrain its advance.

A backward pawn, as its name implies, is a pawn that has been “left behind” and thereby deprived of its pawn support. It is weak because to all intents and purposes it is isolated. A backward pawn on a half-open file (a file with no enemy pawns) is particularly vulnerable to attack.

Pawns standing side by side or supporting one another are said to be united. United pawns are strong.

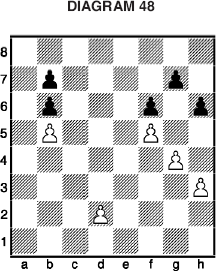

Diagram 48 gives examples of the pawn types mentioned. The white pawns on b5 and d2 are isolated. The two black pawns on b6 and b7 are doubled and isolated. They are blocked by the single white pawn.

The white pawn on d2 is a passed pawn, notwithstanding that it has not yet moved and is isolated. Black’s pawn at g7 is backward; it cannot advance without being captured by the white pawn at f5. Both the pawn formations on the king’s side are composed of united pawns.

A pawn formation is a series of united pawns; it may be mobile or static in character.

(a) Mobile.The strongest mobile formation is line abreast, provided the pawns have ample piece support.

(b) Static.The strongest static pawn formation is one in the form of a wedge with the apex in the centre, or a single diagonal chain directed towards the centre. A chain extending outwards from the centre of the board is weak. Diagram 49 will make this clear. The White pawn structure is strong, that of Black weak. White controls by far the greater space. The structure is static (none of the pawns can move) and the play would therefore be confined to the pieces. Such formations are uncommon; but chains of three pawns, as in the last diagram, occur in many games at one stage or another.

Structures of three united pawns are very common, and every combination, together with general remarks on the intrinsic value of each, is given below. For combinations of four or more pawns, the assessment has only to be extended. Orientations and reflections of a basic structure are not included.

(A) Very strong. The pawns command a line of five squares immediately in front of them. If any one is attacked, it may advance one square when it will automatically be defended.

(B) Strong, particularly if the advanced pawn is nearest the centre of the board.

(C) Strong if the apex is towards the centre, weak if away from the centre. Any bishops remaining on the board must also be taken into account. If White has a bishop on the opposite colour to that on which the pawns stand, their value is enhanced; on the other hand, if Black has a bishop on the opposite colour, it will diminish the value of the structure. The reason for this has already been explained in Chapter 4.

(D) Strong if combined with a bishop on the opposite colour.

(E) Moderately strong if the backward pawn is nearest to the edge of the board, weaker if nearest the middle.

(F) Generally weak, but, if the centre pawn can be advanced, will be strong. The “hole” is an ideal post for a hostile piece.

(G) Weak, particularly if there is a single black pawn in front of the foremost white pawn.

(H) Weak, but slightly better if the double pawn is away from the centre.

(I) Weak, but not so weak as (G) or (H).

(J) Very weak. Again the question of the opposite-coloured bishops will arise.

Supposing Black has castled on the king’s side, and the moment is propitious for attack, which pawn or pawns should White advance?

The choice usually falls between the f-pawn and the h-pawn. It must be remembered that pawns are easily blocked by opposing pawns. But a defender will often be compelled to weaken the attacker to make a profitable sacrifice.

White sometimes advances the g-pawn to drive away an enemy piece (usually a knight) at f6, or to attack a pawn that has been played to h6. You must be careful, when advancing like this, not to expose your own king. In this respect the advance of the g-pawn is especially important since it provides the most shelter for the king.

Here we are concerned primarily with the defence of the king after castling, the rules given holding good, however, for defence under most circumstances.

Pawns are at their strongest in their initial positions, and the golden rule is: “Don’t move a pawn until you are forced to.” The reason for this is that a pawn once moved offers a target and creates structural weaknesses. The exception to this rule is a pawn advance to the third rank in order to fianchetto a bishop.

The defence of the castled king depends to a large extent on the make-up of the attacking forces. Supposing White, who has castled king’s side, is under fire from Black. The most vulnerable point is h2 (compared to f2 prior to castling), particularly if Black has retained the king’s bishop. White must be careful of the move h3 if Black’s queen’s bishop is still on the board, for the sacrifice Bxh3 is a common way to break open the king’s position since, after gxh3, the king is stripped bare.

The main pawn positions that can arise in front of a castled king, together with remarks on the strong and weak points of each, are given in outline:

(A) Strong; particularly if there is a knight at f3 to guard the h-pawn.

(B) Strong; particularly if Black has not the same coloured bishop.

(C) Quite strong; but not so favourable as the first two. Vulnerable to pawn attack.

(D) Quite strong if there is also a knight at f3. May be dangerous if Black has retained the bishop that can attack the h-pawn, or if Black is able to advance the g-pawn with impunity.

(E) Strong; particularly if a knight can be brought to f3.

(F) Weak, but not unduly so, particularly if f4 can be played in safety.

(G) Very weak if the black queen is on the board supported by one or more of the following: (1) Queen’s bishop; (2) One or both knights; (3) A pawn that can be established at f3 or h3 (i.e. either of the holes formed by the advance of the g-pawn). As has been seen in Chapter 4, it is not difficult to mate a king in this position. Of course, if the white king’s bishop is still on the board and can be brought to g2, the position immediately becomes strong (see (B)).

(H) Structurally weaker than (G), this pawn formation does not, however, offer Black quite so many mating opportunities, but almost any hostile man established at g3 will prove a source of embarrassment.

(I) Weak. If White has a bishop at g2 and a knight at f3, the position is considerably improved. Black’s best way of storming this position is by h5 h4, attacking the g-pawn and threatening by exchange to open the h-file.

All other pawn formations in front of a castled king are bad; if the rook has been moved away, each position is proportionately worse. The criterion in all the examples, and in (G) and (H) in particular, lies in whether Black has adequate force and is sufficiently well placed to carry out an attack. If the end game is reached, the pawn structure, so far as the defence of the king is concerned, is inconsequential.

General handling of the pieces in the middle game has already been covered. The bishops and rooks need open lines on which to operate; the knights strong central squares immune from pawn attack. Two bishops co-operate well, covering diagonals side by side. Queen and knight work together harmoniously, as do rook and bishop. Two or more pieces exercising the same function on a file, diagonal or rank can be powerful; for example, queen and bishop (the queen in front of the bishop) attacking a square, especially in the field of the enemy king. Also two rooks, rook and queen or two rooks and queen on a file or rank (the queen behind the rook(s) here). As far as the ranks go, the seventh and occasionally the eighth are the only two that come in for consideration, as on these the major pieces are secure from pawn attack.

Every move by either side may result in a change of square values. A weak square may be said to be a hole in the pawn formation – the result, in the majority of cases, of a backward pawn. This weak square will be a strong point for the other side, and since, by definition, it is immune from pawn attack, it will be an ideal post for a piece. Weak squares may be only temporarily weak, however. The creation and exploitation of weaknesses is one of the fundamentals of master chess.

Blocked positions are not common in chess, although one wing may become paralysed as the result of the rival pawn formations interlocking.

If it is intended to attack on one side of the board, it is often advisable to seal the other side in order to forestall any possible counter-attack in that quarter. This can be accomplished by timely pawn advances.

In a close position, in particular, the ultimate pawn skeleton should be considered with regard to the end game. Open positions are often decided by direct attack in the middle game, and here precise calculation is paramount.

In open games, which can arise from close openings it should be noted, the prestige of the pawn suffers; but often exchanges result in some neglected pawn proving the decisive factor.

There are several traps for winning material that are perennial. It is consequently well worthwhile to commit them to memory. (The examples given are basic structures which must be recognized in game settings and are not, of course, game positions complete in themselves.)

(A) Knight. Be careful to leave an escape square for a knight after playing it to the side of the board, otherwise the advance of a hostile pawn may win it. The same care should be taken if a knight is on the fifth rank with an enemy pawn behind controlling the two best escape squares.

Example: (i) WHITE: N on h4, Ps on e5, f2, g2; BLACK: Ps on e6, g7, h7. If White plays 1. f3?, Black wins the knight by 1. . . . g5.

(ii) WHITE: N on e5, Ps on d4, e3, f4; BLACK: K on e8, N on e7, Ps on d5, e4, f7, h5. Black wins the knight by 1. . . . f6.

(B) Bishop. The trapping of a bishop by pawns was demonstrated in Chapter 4. Another common device is the shutting in of a bishop that captures an undefended rook’s pawn.

Example: WHITE: B on e3; BLACK: R on c8, Ps on a7, b7, c7. If White now takes the pawn – 1. Bxa7, Black plays 1. . . . b6, closing the bishop’s escape route and threatening Ra8 and Rxa7.

(C) Rook. A bishop is sometimes able to shut in a rook, winning the exchange.

Example: WHITE: R on e4, P on a2; BLACK: B on d6, Ps on a5, b7. If White now attacks the a-pawn, disaster awaits: 1. Ra4? Bb4 (now the rook cannot escape) 2. a3 b5, winning the exchange for a pawn.

(D) Queen. A queen can be trapped if she ventures too far into enemy territory, particularly if she has only one line of retreat.

Example: WHITE: Q on a1; BLACK: K on c7, R on d8, B on b7, Ps on a7, b6. If 1. Qxa7? Ra8 and the queen cannot escape.

In Chapter 4 we remarked on the power of the rook on the seventh rank and we also investigated the potentialities of the discovered check. A type of position not by any means uncommon illustrates the devastating effect of the combination of these two forces: WHITE: R on e7, B on a1: BLACK: K on g8, Q on a8, Ns on d7, f8, Ps on a7, b7, c7, g7. Here the black queen, apparently secure in the corner, falls along with all of Black’s queen’s side men; 1. Rxg7+! Kh8 (the only square) 2. Rxd7+(discovered check) Kg8 3. Rg7+ Kh8 4. Rxc7+ (discovered check) Kg8 5. Rg7+ Kh8 6. Rxb7+ (discovered check) Kg8 7. Rg7+ Kh8 8. Rxa7+ (discovered check) Kg8 9. Rxa8.

Before going on to practical examples of middle game play, a few general maxims will not come amiss.

(a) Watch for forks. To someone not familiar with the moves of the pieces, the fork is a perpetual source of worry, particularly where knights are concerned. Even experienced players frequently overlook queen forks, which, because queens are long-range pieces, are often difficult to see. But all pieces are able to fork, and you should keep tactical as well as strategic considerations in mind at all times.

(b) Watch the back rank. Even if no immediate danger threatens, a “hole” for the king by moving up a pawn is always a sound investment if time and position permit.

(c) Do not attack undefended pieces for the privilege of driving them to better squares. Such pieces are best left “hanging” as they may become ideal targets for combinations at a later stage.

(d) After castling K-side, be careful of advancing the f-pawn if the hostile king’s bishop can check. There is a prosaic finesse winning the exchange which is common to such positions:

WHITE: K on g1, Q on d1, R on f1, Ps on f4, g2, h2; BLACK: B on e7, N on g4 or e4. White has just played 1. f4? Play now runs 1. . . . Bc5+ 2. Kh1 Nf2+ (forking king and queen) 3. Rxf2 Bxf2. Black has won a rook for a bishop.

(e) Do not bring rooks into play via the wings. Development of this nature is almost invariably bad.

(f) If you intend to attack, be careful to keep a fluid pawn formation: do not block the position or allow your opponent to do so.

(g) Finally, remember that in chess timidity pays no dividends – play aggressively!

When discussing the question of an attack with pawns on a castled king, it was pointed out that it is often advisable to castle on the opposite side. Here is a good example of this type of game taken from club play.

|

White |

Black |

1. |

e4 |

e6 |

2. |

d4 |

d5 |

3. |

exd5 |

exd5 |

4. |

Bd3 |

Nf6 |

5. |

Ne2 |

Be7 |

6. |

Nbc3 |

c6 |

7. |

Bf4 |

Bg4 |

8. |

f3 |

Bh5 |

9. |

Qd2 |

Nbd7 |

10. |

Ng3 |

Bg6 |

11. |

Nf5 |

0-0 |

12. |

Ne2 |

Re8 |

13. |

g4 |

|

White, having established a strong knight at f5, judges the moment right for attack. Notice these points:

(a) White’s pieces are all in play.

(b) Black’s queen’s bishop is open to attack from the advancing pawns. Black decided not to play Bxf5, as after gxf5 White would have an open file along which the white rooks would threaten the black king.

(c) White’s pawn at f3 immobilizes the knight at f6, the square e4 otherwise providing a splendid outpost for this piece.

13. |

. . . |

Nf8 |

14. |

0-0-0 |

a5 |

Black correctly appraises that the best chance lies in counter-attack on the queen’s wing. However, prospects do not look good and the text move is too slow. From now on White dominates the game.

15. |

h4 |

White threatens h5, which would force White to take off the knight as the bishop has no escape square.

15. |

. . . |

h5 |

16. |

Neg3 |

|

White wishes to recapture on f5 with a knight, and so sacrifices a pawn to this end.

16. |

. . . |

hxg4 |

17. |

fxg4 |

Nxg4 |

These exchanges are fatal for Black, who now opens the g-file as well as allowing the h-pawn to advance.

18. |

h5 |

Bh7 |

19. |

Qe2 |

Nf6 |

20. |

Qg2 |

|

White has gained time and is in a position to exploit the open file. The immediate threat is the curious 21. Nxg7, and the king would not be able to recapture because of 22. Nf5++ Kh8 and 23. Qg7#. The power of the double check is admirably demonstrated: the knight is en prise to the bishop and there are notionally three pieces that Black can interpose between the king and the queen. But a double check prescribes a king move and nothing can be done to avert mate.

20. |

. . . |

Ne6 |

21. |

Be5 |

|

Indirectly attacking the weak g-pawn.

21. |

. . . |

Kh8 |

The black king evades the indirect file attack of the white queen only to walk into the indirect attack of the white bishop on e5. Black could have offered more resistance by playing Ng4, blocking the g-file.

22. |

h6 |

g6 |

To avoid the opening of the h-file, which would be terminal, Black is compelled to advance the g-pawn. Now however the knight at f6 is pinned and Black cannot escape the loss of a piece.

23. |

Nxe7 |

Qxe7 |

24. |

Rdf1 |

Kg8 |

25. |

Rxf6 |

Nf8 |

26. |

Nh5 |

Nd7 |

Black cannot capture the knight as the pawn is pinned.

27. |

Bxg6 |

An example of bulldozer tactics to crush a weak king’s position: Black’s last defences are stripped.

27. |

. . . |

fxg6 |

28. |

Rxg6+ |

Bxg6 |

29. |

Qxg6+ |

Kf8 |

30. |

Bg7+ |

Kg8 |

31. |

h7# |

|

Black watched passively as White’s forces gathered strength, instead of initiating early action in the centre or on the queen’s side. Black’s position was cramped, making it difficult to marshal a defence – notice that at the end of the game, the queen’s rook still stood on its starting square.

One lesson at least may be drawn: it rarely pays to adopt wait-and-see tactics in the middle game.

When engaged in a struggle on one wing, an eye should be kept on the possibility of a quick switch-over to the other wing if the opportunity presents itself.

Here is another game in which White never for one moment loses sight of the whole board.

|

White |

Black |

1. |

e4 |

e5 |

2. |

Nf3 |

Nc6 |

3. |

Bb5 |

a6 |

4. |

Ba4 |

Nf6 |

5. |

0-0 |

Nxe4 |

6. |

d4 |

b5 |

7. |

Bb3 |

d5 |

8. |

dxe5 |

Be6 |

Up to here, identical with the game given in Opening 5 in the last chapter.

9. |

Qe2 |

Be7 |

10. |

Rd1 |

Na5 |

11. |

Nbd2 |

Nxd2 |

12. |

Bxd2 |

Nc4 |

13. |

Bxc4 |

bxc4 |

14. |

b3 |

cxb3 |

15. |

axb3 |

|

White has gained a positional advantage. The black a-pawn is isolated on a file open to the white rooks. The threat is Rxa6.

15. |

. . . |

Qc8 |

16. |

Ra5 |

|

This square is momentarily safe from bishop attack so White takes the opportunity of doubling rooks.

16. |

. . . |

Qb7 |

17. |

Rda1 |

Bc8 |

18. |

Bg5 |

|

An attempt to prevent Black castling. If Black plays now 18. . . . f6, White wins quickly by 19. exf6 and the black bishop is pinned.

18. |

. . . |

Bb4 |

19. |

R5a4 |

0-0 |

20. |

Qd3 |

Bd7 |

A trap. If now 21. Rxa6 Bb5! would win the white queen in exchange for rook, minor piece and pawn. However, Black did not expect White to walk the plank, and his real intention was to establish the bishop at b5, relieving the weak a-pawn and freeing the queen’s rook for action elsewhere. Black is blind to White’s plan, although White’s last move, coupled with the presence of the two white minor pieces on the king’s side were a warning that White might not be wholly concerned with what was happening on the queen’s side. The next move comes as a complete shock.

21. |

c3 |

Bxa4 |

Black can do no better than accept the offer of the exchange.

22. |

Rxa4 |

Bc5 |

23. |

Rh4 |

Switching to the king’s side. White threatens mate on the move by Qxh7.

23. |

. . . |

f5 |

The alternatives were: (a) 23. . . . g6, permitting Bf6 and a set-up similar to example H of Mating Combinations (Chapter 4), when White can force mate in a few moves; or (b) 23. . . . h6, allowing the sacrificial combination 24. Bxh6! and Black’s king’s position is hopeless. This second type of position – when the king is denuded of pawn protection – has also been referred to previously, an endorsement of how frequently these standard positions can arise.

24. |

exf6 e.p. |

White takes the pawn en passant. It cannot be recaptured without quick loss, as Qxh7+ is still threatened.

24. |

. . . |

g6 |

25. |

Ne5 |

c6 |

26. |

Nxg6 |

|

As in the previous game, White sacrifices a piece on g6 to break open the position. Here it cannot be taken without mate in two following (26. . . . hxg6 27. Qxg6+ Qg7 28. Qxg7#).

26. |

. . . |

Rf7 |

27. |

Ne5 |

Re8 |

28. |

Qg3 |

|

28. Nxf7 would be a bad mistake. 28. . . . Re1+ 29. Qf1 (forced) Rxf1+ 30. Kxf1 Qxf7 and wins. This bears out the maxim “Watch the back rank.”

28. |

. . . |

Qa7 |

Black cannot well avoid the double check, for Kf8 or Kh8 would be met with decisive checks from the bishop and knight respectively.

29. |

Bh6+ |

Kh8 |

30. |

Ng6+ |

Kg8 |

Black cannot capture the knight: 30. . . . hxg6 31. Bf7++ Kg8 32. Rh8#.

31. |

Ne7++ |

Kh8 |

32. |

Qg7+ |

Rxg7 |

33. |

fxg7# |

|

A delightfully conducted attack. (See diagram 72.)

A breakthrough in the centre in the early stages of the game is not common, since it can only be achieved when the opposition is disproportionately weak. This example shows condign punishment meted out to a timid player.

|

White |

Black |

1. |

c4 |

e5 |

2. |

Nf3 |

e4 |

3. |

Nd4 |

d5 |

4. |

e3 |

c5 |

5. |

Nb3 |

d4 |

6. |

d3 |

|

White was worried about being left with a backward d-pawn.

6. |

. . . |

exd3 |

7. |

Qxd3 |

Nc6 |

8. |

exd4 |

cxd4 |

Black has got a passed pawn in the centre. Can it be held? If so, White’s game is already bad as the pawn exercises restraint over the white minor pieces. White will take at least two moves to bring another piece to bear on the intruder (Nbd2–f3), and meanwhile the queen is exposed to attack.

9. |

a3 |

White is afraid of Nb4 because after 10. Qe4+ Be6 11. Nxd5 Qxd5 12. Qxd5 Nc2+ 13. K moves, Nxd5 and Black has won a piece for a pawn. This line is by no means forced however, and the text is a waste of time.

9. |

. . . |

Qf6 |

10. |

N1d2 |

Bf5 |

11. |

Ne4 |

|

This loses, but White had nothing better due to Black’s command of the centre.

11. |

. . . |

Qe6 |

Pinning the knight and threatening to win it next move. Observe how the white pieces get tied up in trying to prevent the loss of this piece.

12. |

f3 |

Nf6 |

13. |

Nd2 |

|

Since the knight on e4 is unable to move, this means the knight on f3.

13. |

. . . |

0-0-0 |

White is completely tied up. The text brings the rook to guard the advanced pawn. White can do nothing about the terrible threat of 14. . . Ne5! attacking the queen and preparing a further advance of the formidable and now secure pawn.

14. |

Kd1 |

To unpin the knight.

14. |

. . . |

Ne5 |

15. |

Qb3 |

d3 |

16. |

Nxf6 |

gxf6 |

17. |

Qa4 |

|

Paralysis has set in, and White is reduced to moving the queen again.

17. |

. . . |

Bc5 |

Black guards the a-pawn, brings the last minor piece into play and unites the rooks, all in the one move.

18. |

Nb3 |

Nxf3 |

An unnecessary sacrifice. Black could have won more convincingly by playing d2, followed, when White takes the pawn, by Be3, leaving White hopelessly pinned.

19. |

gxf3 |

White has no option but to accept: Qe1# was threatened. Here 19. Bd2 was useless 19. . . . Nxd2 20. Nxd2 Bg4+ 21. Nf3 (not 21. Kc1 Qe1#) Rhe8 22. Kc1 (22. Qa5 is no better) Bxf3 23. gxf3 Qe1+ 24. Qd1 Be3+ etc.

19. |

. . . |

d2 |

The pawn which has been the cause of all White’s troubles is now sacrificed to force the win. Whichever white piece captures (although again there is no option) will be pinned.

20. |

Bxd2 |

Rhe8 |

21. |

Bh3 |

|

White had to prevent mate at e1.

21. |

. . . |

Qe2+ |

22. |

Kc1 |

Bxh3 |

23. |

Re1 |

Qxe1+! |

A mistake, overlooking Black’s queen sacrifice. The best defence was Nxc5.

23. |

. . . |

Qxe1+! |

24. |

Bxe1 |

Rxe1+ |

25. |

Kc2 |

Bf5+ |

26. |

Kc3 |

Re3# |

A pleasing finish. Note how White’s forces were split in two by the centre thrust and how, until near the end, neither of the white bishops or rooks had even moved. In the final position it will be seen that both the centre files are controlled by the black rooks and both bishops are occupying the best possible squares relative to the position, whereas not one of the white pieces is well placed.

The Q-side attack differs fundamentally from the K-side attack in that there is no obvious target. This is only true in the broad sense, for in effect any weakness constitutes a target; but a weakness is not strictly a weakness unless it can be exploited. A Q-side attack may be desirable for one or more of several reasons; it may be to counter a K-side attack, it may be because the K-side is either blockaded or barren of opportunity, or it may be because the dispersal of the pieces is such as to be conducive to action on this wing. In the Q-side attack the balance of pawns engaged is of prime importance. By early exchanges it is common to find one player left with three pawns against two on the Q-side and with, say, three against four in the centre and on the K-side. In any case, the attacker’s plan should be governed to a large extent by the pawn ratio and the pawn structure, for weaknesses are created primarily by pawns through their inability to retrace their steps.

The attacker therefore launches an assault with the intention of exploiting (or creating) a weakness in order to achieve an advantage in material, space or time.

The attacker must be prepared to change his plan at any apparent change of weaknesses (i.e. when the defender disposes of one weakness only to create another).

The example appended is from Master play (Euwe-Medina London 1946), and I have selected it for its simplicity of idea and execution.

|

White |

Black |

1. |

d4 |

d5 |

2. |

c4 |

e6 |

3. |

Nc3 |

Nf6 |

4. |

Bg5 |

Be7 |

5. |

e3 |

h6 |

6. |

Bh4 |

0-0 |

7. |

Rc1 |

Ne4 |

8. |

Bxe7 |

Qxe7 |

9. |

cxd5 |

Nxc3 |

Not of course 9. . . . exd5 10. Nxd5!

10. |

Rxc3 |

exd5 |

11. |

Bd3 |

c6 |

12. |

Ne2 |

Nd7 |

13. |

0-0 |

Nf6 |

14. |

Qb1 |

|

Up to here the game has followed well-trodden paths. White now perceives that the king’s side is sterile of opportunity, the centre is closed (there is little chance of being able to force e4), and therefore the future of the game lies on the queen’s wing.

Although White has the pawn minority on this side (two to three), the Black pieces are not well placed whilst White can manoeuvre freely. The text move prepares the advance of the b-pawn.

14. |

. . . |

a5 |

Temporarily delaying the advance of the pawn.

15. |

a3 |

Bd7 |

White has succeeded in creating a small weakness in the black position: either the b- or c-pawn is going to be permanently backward.

b4 |

axb4 |

|

17. |

axb4 |

Ra4 |

Black has obtained compensation in the open rook’s file. There follows a typical manoeuvre in which Black moves the rook up to attack an undefended piece and is thereby able to double rooks on the file.

18. |

Rb3 |

Not 18. b5 cxb5 19. Bxb5 Rb4 20. Rb3 Bxb5 21. Rxb4 Bxe2 22. Rxb7 Qe4 forcing the exchange of queens and leaving Black with a material advantage. Subtle resources frequently lurk in innocent-looking positions.

18. |

. . . |

Rfa8 |

19. |

b5 |

g6 |

20. |

bxc6 |

Bxc6 |

Now the black b-pawn is isolated. The d-pawn is also isolated. Black could have avoided both these contingencies by recapturing with the pawn, but then the bishop would have been shut in, a white rook would have been able to occupy the seventh rank, and the advance c5 would probably never have been playable.

21. |

Bb5 |

Ra2 |

22. |

Nc3 |

R2a3 |

23. |

Rc1 |

Ng4 |

24. |

Rxa3 |

Rxa3 |

25. |

Nd1 |

|

Black threatened Qh4 with a winning attack by: 25. . . . Nxe3 26. fxe3 Qxe3+ 27. Kh1 Rxc3.

25. |

. . . |

Qc7 |

g3 |

|

Black threatened Qxh2+. White correctly estimates Black’s attack to be of little consequence as Black has not now time to take advantage of White’s weakened pawn position.

26. |

. . . |

Qa5 |

27. |

Bxc6 |

bxc6 |

28. |

h3 |

Nf6 |

29. |

Rxc6 |

|

The weak pawn falls. Black’s next move enables White to switch flanks and proceed to a direct attack on the black king.

29. |

. . . |

Ra1 |

30. |

Qb8+ |

Kg7 |

31. |

Qe5 |

|

Wrong would have been 31. Rxf6, hoping for 31. . . . Kxf6 32. Qe5# because of the reply 31. . . . Rxd1+ 32. Kg2 Qe1 and now White, faced with a mate threat, has nothing better than 33. Rxf7+ Kxf7 34. Qc7+ Kf6 35. Qd6+ etc.

31. |

. . . |

Rxd1+ |

White has not sacrificed a piece because the black knight is pinned and cannot be saved.

32. |

Kh2 |

Qd8 |

If 32. . . . Qe1, White gets there first with 33. Qxf6+ and mate in two.

33. |

Rd6 |

Qxd6 |

There is nothing better. If 33. . . . Qc7 34. Qxf6+ Kh7 35. Rd8 threatens mate on the move and the queen must be given up. Or 33. . . . Qe8 34. Qxf6+ Kh7 35. Kh2 and the black d-pawn will fall. But not 35. Rd8? Qe4+ and Black wins.

34. |

Qxd6 |

Rd2 |

35. |

Qe5 |

|

And Black prolonged the game a few more moves before resigning.

The game, logical throughout, is a lesson in model play on the part of White who created weaknesses and exploited them sufficiently to win a pawn, and then attacked the compromised defence structure that remained. Even if Black had not gone in for the faulty combination that cost the game, it would not have been long before White’s extra pawn would have made itself felt. The isolated d-pawn would also have been difficult to defend against the combined assault of the White pieces, and the bolder but swifter death was to be preferred.

To give you practice in assessing positions where it is often possible to force immediate wins, some examples from play are given. In all cases White, to move, wins. No solution is longer than six moves, and the examples are given in order of difficulty. Solutions are given on page 158.

Diagram 75: 1. Qxh7+ Kxh7 2. hxg6#.

Diagram 76: 1. Qxh7+ Kxh7 2. Nxf6+ Kh8 3. Ng6#.

Diagram 77: 1. Qxg7+ Kxg7 2. Bc3+ Kg6 (Kg8 3. Nh6#) 3. Nf4#.

Diagram 78: 1. Bf8 dis+ Bh5 2. Qxh5+ gxh5 3. Rh6#.

Diagram 79: 1. Rd8+ Rxd8 2. Qa2+ (and now White has the Philidor’s Legacy) Kh8 3. Nf7+ Kg8 4. Nh6+ Kh8 5. Qg8+ Rxg8 6. Nf7#.

Diagram 80: 1. Ra8+ Kxa8 2. Ra1+ Kb8 3. Ra8+ Kxa8 4. Qa1+ Kb8 5. Qa7+ Kc8 6. Qa8#.