CHAPTER 5

Teaching Individual Words

Consider the power that a name gives a child. Now this is a table and that a chair…. Having a name for something means that one has some degree of control…. As children get more words, they get more control over their environment…. Language and reading both act as the tools of thought to bring representation to a new level and to allow the formation of new relationships and organizations…. To expand a child’s vocabulary is to teach that child to think about the world.

—Steven Stahl and Katherine Dougherty Stahl, Vocabulary Scholars

As Stahl and Stahl so eloquently note, having a name for something gives children a tremendous advantage. As children’s vocabularies grow, so do their abilities to think about their world, to exercise some control over it, and of course to communicate their thoughts to others. As I noted in earlier chapters and will again note in this one, over their years of schooling, students are faced with learning a truly astounding number of words, many more than we could possibly teach them one by one. However, the fact that students need to learn more words than we can possibly teach them does not mean that we should not teach them some words. In fact, we should teach them a lot of words.

Teaching individual words pays a number of important dividends. First, and most obviously, teaching a child a word leaves her with one fewer word to learn independently. Second, teaching individual words gives students a store of words that they can use to explore and understand their environment. Third, teaching individual words can increase students’ comprehension of selections containing those words. Fourth, teaching individual words can increase the power and overall quality of students’ speech, writing, and communications skills. Finally, and very importantly, teaching individual words demonstrates our interest in words, and teaching them in engaging and interesting ways fosters students’ interest in words.

In this chapter, I discuss a number of effective ways to teach individual words. Using different ways of teaching individual words is important for several reasons. For one thing, different words represent different learning tasks. For example, some of the words you teach will be words that are in students’ listening vocabularies but that they don’t recognize in print, while others will be words that are not in students’ listening vocabularies and that represent new and difficult concepts. For another thing, in different situations you will have different goals for teaching a word. In one case, for example, you may just want to introduce the word so that students won’t stumble over it when they see it in an upcoming passage. In another, you will want to give students deep, rich, and lasting meanings for a word. Yet another reason for using different ways of teaching words is that some students will learn best with some methods while other students will learn best with other methods. And yet one more reason for using different methods is to provide some variety for both students and yourself. If each and every time you taught vocabulary, you taught it in just the same way, both you and your students would soon tire of the approach.

This chapter is divided into four sections. In the first section, “Preliminaries to Teaching Individual Words”, I discuss several factors that need to be considered before you actually teach words, including the various learning tasks that different words represent. In the much-longer second section, Methods of Teaching Individual Words, I describe and give examples of instructional methods to fit the variety of word-learning situations students face. In the third section, Selecting Among the Methods and Teaching Vocabulary to Improve Reading Comprehension, I discuss these two critical topics. In the fourth and final section, Repetition and Review, I note the absolute necessity of providing students with plenty of repetition and review of newly learned words and describe several methods of providing it.

PRELIMINARIES TO TEACHING INDIVIDUAL WORDS

In this section, a precursor to the discussion of specific procedures for teaching individual words, I discuss five topics: how many words students need to learn over the elementary and secondary school years, levels of word knowledge, various word-learning tasks that students face with different words, providing student-friendly definitions, and some general principles of vocabulary instruction.

How Many Words Must Students Learn?

As I explained in Chapter 2, across the years of schooling achieving students learn a huge number of words. Most students enter school with relatively large oral vocabularies, perhaps 10,000 words, and quite small reading vocabularies, perhaps numbering only a few words. Ahead of them lies a sizable task. The work of Anderson and Nagy (1992); Anglin (1993); Miller and Wakefield (1993); Nagy and Anderson (1984); Nagy and Herman (1987); Snow and Kim (2007); Stahl and Nagy (2006); and White et al. (1990) suggests that students learn from 3,000 to 4,000 word families each year and can read around 50,000 words by the time they graduate from high school.

Obviously, students learn many more words each year than we can teach directly. Teaching the 3,000 to 4,000 or so words that students learn each year during a 180-day school year would mean teaching something like 20 words a day. This does not, should not, and could not happen. However, as I have noted, the fact that we cannot directly teach all of the words students need to learn does not mean that we cannot and should not teach some of them. Moreover, the figures I have given here are for average students. As I noted in Chapter 2, children growing up in poverty and English learners may have much smaller vocabularies, making teaching individual words even more important for them.

Levels of Word Knowledge

Another factor to consider in teaching individual words is the level of word knowledge that students need to achieve. As noted in Chapter 2, word knowledge exists on a continuum ranging from absolutely no knowledge of the word to rich and powerful knowledge of the word. Here, again, is the continuum Beck and her colleagues have suggested:

- No knowledge

- General sense: for example, mendacious has a negative connotation

- Narrow, context-bound knowledge

- Has knowledge of a word but not able to recall it readily enough to use it in appropriate situations

- Rich, decontextualized knowledge of a word’s meaning, its relationship to other words, and its extension to metaphorical uses (Beck et al., 2013, p. 11)

Certainly, no single encounter with a word is likely to produce all of these types of knowledge. On the other hand—and this is a critical point underlying the task of teaching individual words—no single encounter with a word needs to produce all of these types of knowledge. Instead, any encounter with a word can be considered as only one in a series of experiences that will eventually lead students to mastery of the word. Even a brief encounter with a word will leave some trace of its meaning and make students likely to more fully grasp its meaning when they again come across it. Moreover, brief instruction provided immediately before students read a selection containing the word may be sufficient to prevent their stumbling over it as they read.

As a consequence, the methods described in this chapter include relatively brief instruction that serves primarily to start students on the long road to full mastery of words, as well as more time-consuming, extensive, and ambitious instruction that enables students to develop thorough understandings of words and perhaps use the words in their speech and writing. It is important to recognize that, while students need not learn all words thoroughly, they must learn most words they will encounter frequently in reading well enough that their responses to them are automatic, that is, instantaneous and without attention (LaBerge & Samuels, 1974). Otherwise, the need to shift from attention to larger units of meaning—clauses, sentences, and entire passages—to individual words will overload memory limitations and thwart the meaning-getting process.

The Word-Learning Tasks Students Face

As I have noted, all word-learning tasks are not the same. Word-learning tasks differ depending on such matters as how much students already know about the words to be taught, how well you want them to learn the words, and what you want them to be able to do with the words afterwards. Here, I consider seven tasks students face in learning words, some of which are quite different from others and require quite different sorts of instruction.

Learning a Basic Oral Vocabulary. As noted, many children arrive at school with substantial oral vocabularies, perhaps numbering 10,000 words. However, some linguistically less advantaged children come to school with meager oral vocabularies; and of course some English learners come to school with very limited English vocabularies. For such children, building a basic oral vocabulary of the most frequent English words is of utmost importance. Because learning a basic oral vocabulary is so important, I discussed it at length in a separate chapter—Chapter 4. It will not be considered further in this chapter.

Learning to Read Known Words. Learning to read known words, words that are already in their oral vocabularies, is the major vocabulary-learning task of beginning readers. Such words as surprise, stretch, and amaze are ones that students might be taught to read during their first 3 years of school. By 3rd or 4th grade, good readers will have learned to read most of the words in their oral vocabularies. However, the task of learning to read many of the words in their oral vocabularies remains for many less-proficient readers and for some English learners.

Learning New Words Representing Known Concepts. A third word-learning task students face is learning to read words that are in neither their oral nor their reading vocabularies but for which they have an available concept. For example, the word goulash, meaning a type of stew, would be unknown to a number of 3rd graders. Similarly, the word ensemble, meaning a group of musicians, would be an unknown word for many 9th graders. But in both cases the concepts are familiar. All students continue to learn words of this sort throughout their years in school, making this one of the major word-learning tasks students face. It is also a major learning task for English learners, who, of course, have a number of concepts for which they do not have English words.

Learning New Words Representing New Concepts. Another word-learning task students face, and a very demanding one, is learning to read words that are in neither their oral nor their reading vocabularies and for which they do not have an available concept. Learning the full meanings of such words as equation, impeach, and mammal is likely to require most elementary students to develop new concepts, while learning the full meanings of such words as mass, enzyme, and fascist will require most high school students to develop new concepts. All students continue to learn words of this sort throughout their years in school and beyond. Once again, learning new concepts will be particularly important for English learners. Also, students whose backgrounds differ from that of the majority culture will have internalized a set of concepts that is at least somewhat different than the set internalized by students in the majority culture. Thus, words that represent known concepts for some groups of students will represent unknown concepts for other groups.

Learning New Meanings for Known Words. Still another word-learning task is learning new meanings for words that students already know with one meaning. Many words have multiple meanings, and thus students frequently encounter words that look familiar but are used with a meaning different from the one they know. Students will encounter such words throughout the elementary grades and beyond. Teaching these words occupies a special place in content areas such as science and social studies because words often have different and important meanings that are critical to comprehension in particular content areas. The meaning of product in mathematics and that of legend in geography or history are just two examples of such words.

Clarifying and Enriching the Meanings of Known Words. The meanings students originally attach to words are often imprecise and only become fully specified over time; thus, another word-learning task is clarifying and enriching the meanings of already known words. For example, students initially might not recognize any difference between brief and concise, not know what distinguishes a cabin from a shed, or not realize that the term virtuoso is usually applied to those who play musical instruments. Although students will expand and enrich the meanings of the words they know as they repeatedly meet them in new and slightly different contexts, some more direct approaches to the matter are warranted.

Moving Words into Students’ Expressive Vocabularies. Still another word-learning task is moving words from students’ receptive vocabularies to their productive vocabularies, that is, moving words from students’ listening and reading vocabularies to their speaking and writing vocabularies. Sixth graders, for example, might know the meaning of the word ignite when they hear it or read it, yet never use the word themselves; and 12th graders might know the word huckster but not use it. Most people actively use only a small percentage of the words they know. Assisting students in actively using the words they know will make them better and more precise communicators. This is particularly true of English learners, who are likely to have small expressive vocabularies as they begin learning English and who need a lot of practice and encouragement to use the words they know.

Providing Student-Friendly Definitions

Virtually all effective vocabulary instruction is likely to include a definition. And not any definition will do. Instructional definitions should be what Beck, McKeown, and Kucan (2002, 2013) have described as “student friendly.” Traditional dictionary definitions are often brief, phrased in ways that provide little information to learners, and include words that are more difficult than the word being defined. Such definitions are of little use to many students trying to learn an unknown word. Student-friendly definitions, by contrast, are longer, often written in complete sentences, phrased in ways that are as helpful as possible to second-language learners, and do not include words more difficult than the word being defined. Also, sentences that give an instance of the thing named can be a useful add-on to a student-friendly definition. Figure 5.1 shows some examples of both traditional and student-friendly definitions. For more examples of student-friendly definitions, take a look at the Collins COBUILD New Student’s Dictionary (2005). While most dictionaries do not use student-friendly definitions, the Collins COBUILD includes largely student-friendly definitions. Another source of student-friendly definitions and sentences that use the target word in context is Wordsmyth (www.wordsmyth.net/).

Figure 5.1. Traditional and Student-Friendly Definitions

Traditional Definitions

Dazzling: Bright enough to deprive someone of sight temporarily. (Microsoft Word 2016 for Mac)

Climate: The prevailing weather conditions of a particular region. (American Heritage Dictionary, 2001)

Contagious: Transmissible by direct or indirect contact; communicable. (American Heritage Dictionary, 2001)

Student-Friendly Definitions

Dazzling: If something is dazzling, that means that it’s so bright that you can hardly look at it. After lots of long, gloomy winter days, sunshine on a sunny day might seem dazzling. (Beck et al., 2002, p. 55)

Climate: Climate is the normal weather of a place.

Contagious: A contagious disease can be caught by touching people or things infected with it, or sometimes by just getting close to them. The flu is a very contagious disease.

Some General Principles of Vocabulary Instruction

Before turning to the second main section of this chapter, Methods of Teaching Individual Words, one additional preliminary task remains, which is providing some general principles of vocabulary instruction. The following set of principles come from my own thinking and many other vocabulary authorities, including Herman and Dole (1988); Stahl (1998); Beck and her colleagues (2002); Biemiller (2004); Nagy (2005); Stahl and Nagy (2006); Kame’enui and Baumann (2012); Goldenberg et al. (2013); Blachowicz et al., (2013); Lesaux, Kieffer, Kelly, and Harris (2014); and Ford-Connors and Paratore (2015). Although I have described these as principles, guidelines would perhaps be a better word. They are not absolutes and should be followed only when you deem them appropriate. Moreover, they virtually always come at the cost of time, a factor I will consider after listing them.

- Include both definitional and contextual information. That is, give students both a definition of the words being taught, and have them work with the words in context.

- Involve students in active and deep processing of the words. Engage students in activities that lead them to consider the words’ meaning, relate that meaning to information stored in memory, and work with the word in creative ways. Such activities might include putting the definition of a new word into their own words, giving examples and nonexamples of situations in which the word can be used, examining ways in which the new word relates to them personally, and recognizing similarities and differences between the new word and words they already know.

- Provide students with multiple exposures to the word. You might, for example, define the word, use it in a sentence, ask students to use it in a sentence, involve students in recognizing appropriate and not-so-appropriate uses of the word, and play games involving the word.

- Review, rehearse, and remind students about the word in various contexts over time. Having taught a word before students read a selection, ask them to note its occurrence in the text, and then discuss the word and the context in which it occurred after students read. Then, throughout the weeks and months following initial instruction, look for and point out other occurrences of the word, ask students to look for and point out other occurrences, and occasionally have a brief review of some of the words taught.

- Include discussion as a prominent part of instruction. Discussion is one method of actively processing word meanings, discussion gives student the opportunity to hear and use the word in a variety of context, and discussion enables students to learn from each other.

- Spend a significant amount of time on the word. During this time, involve students in actively grappling with the word’s meaning. With words as with learning in general, time on task is crucial. The more time you spend on a word, the better the chance that students will build rich and deep meanings for the word.

These are sound principles, but each of them should be prefaced with the phrase “for the strongest possible results.” There is a definite cost of teaching in order to achieve the strongest possible results. Doing so takes time. Because there are many more words that could be taught than you can possible teach and because you have many things to do other than teach words, your time is definitely limited. Often, it will be necessary to teach words in ways that do not consume large amounts of time and do not in fact produce the strongest possible results. In these cases, think of your initial instruction on a word as just that—initial instruction, an initial experience that starts students on the long road to learning full and rich meaning for the word.

METHODS OF TEACHING INDIVIDUAL WORDS

As noted, the instruction needed for some word-learning tasks is much more complex than that for others. In this, the longest section of the chapter, I provide detailed descriptions and examples of methods of teaching individual words that accomplish each of the word-learning tasks I have described. Note, too, that instruction appropriate for some of these tasks will promote deeper levels of word knowledge than others.

Building Children’s Oral Vocabularies

Building children’s oral vocabularies was a major topic of Chapter 4 and will not be dealt with in this chapter. However, I do want to once again stress that for children who enter school with small vocabularies—linguistically disadvantaged children and some English learners—building their oral vocabularies is of utmost importance. As explained in Chapter 4, the primary vehicle for doing so is interactive oral reading.

Teaching Students to Read Known Words

In learning to read known words, the basic task for the student is to associate what is unknown, the written word, with what is already known, the spoken word. This is a decoding task. Students need to associate the written word, which they do not recognize, with the spoken word, which they know. To establish the association between the written and spoken forms of a word, students need to see the word at the same time that it is pronounced, and once the association is established, it needs to be rehearsed and strengthened so that the relationship becomes automatic. I have listed these steps below to emphasize just how straightforward the process is.

Procedure for Teaching Students to Read Known Words

- See the word

- Hear the word as it is seen

- Rehearse that association a myriad of times

Of course, there are a number of ways in which each of these steps can be accomplished. Students can see the word on the board, on a computer screen, or in a book that they are reading or you are reading to them. They can hear the word when you say it, when another student says it, or when a voice simulator pronounces it. They can rehearse the association by seeing the word and pronouncing it a number of times, writing it, and playing games that require them to recognize printed versions of it. However, wide reading in materials that contain many repetitions of the words and that are enjoyable and easily read by students is by far the best form of rehearsal for these words and an essential part of students’ mastering them.

Teaching New Words Representing Known Concepts

Here, I describe three approaches to teaching new words representing known concepts. These require differing amounts of teacher time, differing amounts of class time, and differing amounts of students’ time and effort; and they are likely to yield different results.

The first method, Context-Dictionary-Discussion, takes the least amount of preparation on your part while taking a fair amount of class time. It will provide students with a basic understanding of a word’s meaning and give them practice in using the dictionary. As shown below, it consists of three steps. In this and most of the descriptions of teaching methods I give, I will present examples of the instruction using two words, one typical of words for primary or elementary students and one typical of words for middle-school and secondary students.

Context-Dictionary-Discussion Procedure

- Gives students the word in context.

- Ask them to look it up in the dictionary.

- Discuss the definitions they come up with.

Excel: To get into the Olympics, a person must really excel at some Olympic sport.

Subscript: Nicole, a student in Ms. Green’s 3rd-hour mathematics class, had used the term x to refer to three different quantities, and thus she added subscripts to distinguish the three terms.

The second method, the Context-Relationship Procedure (Graves & Slater, 2008), takes quite a bit of preparation time on your part. However, the classroom presentation of words in this way takes only about a minute per word, and I have repeatedly found that students remember quite rich meanings for words taught in this fashion. Here is how it is done.

Context-Relationship Procedure

- Create a brief paragraph that uses the target word three or four times and in doing so gives the meaning of the word.

- Follow the paragraph with a multiple-choice item that checks students’ understanding of the word.

- Show the paragraph (probably on an overhead), read it aloud, and read the multiple-choice option.

- Pause to give students a moment to answer the multiple-choice item, give them the correct answer, and discuss the word and any questions they have.

Conveying: The luncheon speaker was successful in conveying her main ideas to the audience. They all understood what she said, and most agreed with her. Conveying has a more specific meaning than talking. Conveying indicates that a person is getting her ideas across accurately.

Conveying means

___ A. putting parts together.

___ B. communicating a message.

___ C. hiding important information.

Rationale: The rationale for my wanting to expose students to a variety of words and their meanings is partially that this will help them become better thinkers who are able to express their ideas more clearly. Part of that rationale also includes my belief that words themselves are fascinating objects of study. My rationale for doing something means my fundamental reasons for doing it.

Rationale means

___ A. a deliberate error.

___ B. the basis for doing something.

___ C. a main idea for an essay.

Vocabulary Self-Collection Strategy

The Vocabulary Self-Collection Strategy (Ruddell & Shearer, 2002) differs from the techniques I have described thus far in that it is specifically designed so that students, rather than the teacher, select the words to study. Because of this, it is particularly useful for getting students interested and excited about words. Here is how it is typically done:

- Emphasize the importance of vocabulary and the importance of students taking charge of their own learning.

- Ask each student to select several words that they do not know the meaning of, want to study, and think important for the class to learn. You can specify a set of words to choose from or allow students to choose their words from any sources: school reading, recreational reading, the Internet, TV, conversations, popular songs, or anyplace else they come across an interesting and important word.

- Tell students to bring in their words to class and choose one to focus on. They should then explain where they found the word, what they think it means, and why it is important for the class to know. Also bring one word yourself.

- Once words are submitted, use discussion and perhaps the dictionary to clarify their meanings, and have students record the words and definitions in a vocabulary journal.

- During the week, work with the words in various ways using discussion and other interactive techniques.

- At the end of the week, evaluate students on their ability to explain the words’ meanings and to use them in sentences.

While these steps describe the form the Vocabulary Self-Collection Strategy typically takes, like other instructional techniques, it can be modified to fit you and your class.

Teaching New Words Representing New Concepts

The dividing line between words that represent known concepts and those that represent new concepts is not a precise one. Words fall on a continuum, ranging from those that clearly represent known concepts to those that clearly represent new and challenging concepts. Moreover, a word that is likely to be a new concept for most 4th graders may be a familiar concept for most 10th graders. For example, the word ecological might represent a new concept for most 4th graders but a familiar one for most 10th graders, while the word margin (as in buying stocks on margin) is likely to represent a new concept to anyone not familiar with the stock market. This section describes two very robust procedures for teaching new and potentially challenging concepts, while the upcoming section on Clarifying and Enriching the Meanings of Known Words describes several other procedures that can used to teach new concepts. The first procedure described here was developed by Frayer, Frederick, and Klausmeier (1969), and is often called the Frayer Method. It is a very powerful, although definitely time consuming, approach. I will present the major steps of the methods with examples for the word/concept globe and the word/concept perseverance.

Frayer Method

1. Define the new concept, giving its necessary attributes. When feasible, it is also helpful to show a picture illustrating the concept.

- A globe is a spherical (ball-like) representation of a planet.

- Perseverance is a trait that a person might possess. A person demonstrates perseverance when she remains constant to some purpose or task over some extended period despite obstacles.

2. Distinguish between the new concept and similar but different concepts with which it might be mistaken. In doing so it may be appropriate to identify some accidental attributes that might falsely be considered to be necessary attributes of the new concept.

- A globe is different from a map because a map is flat. A globe is different from a contour map, a map in which mountains and other high points are raised above the general level of the map, because a contour map is not spherical.

- Perseverance differs from stubbornness in that perseverance is typically seen as a positive quality and the goal toward which one perseveres is typically a worthwhile one. Conversely, stubbornness is usually seen as a negative quality, and the goal pursued by a person who is being stubborn is often not a worthwhile one.

3. Give examples of the concept and explain why they are examples.

- The most common globe is a globe of the earth. Globes of the earth are spherical and come in various sizes and colors.

- A much less common globe is a globe of another planet. A museum might have a spherical representation of Saturn.

- A person who graduates from college despite financial responsibilities that require her to work full time while in college would be demonstrating perseverance because the goal is worthwhile and it takes a long and steady effort to reach it.

- A person who learns to ski after losing a leg in an accident is demonstrating perseverance for similar reasons.

4. Give nonexamples of the concept.

- A map of California

- A map of how to get to a friend’s house

- Someone who goes fishing a lot just because she enjoys it is not demonstrating perseverance because there is no particular purpose here and no obstacles.

- Someone who waters her lawn once a week is not demonstrating perseverance because there is no particular challenge in doing so.

5. Present students with examples and nonexamples and ask them to distinguish between the two.

For globe:

- An aerial photograph of New York (nonexample)

- A red sphere representing Mars (example)

- A walking map of St. Louis (nonexample)

- A ball-shaped model of the moon (example)

For perseverance:

- Reading an interesting book that you thoroughly enjoy (nonexample)

- Completing a canoe trip from the headwaters of the Mississippi to New Orleans (example)

- Eating a dozen donuts because you are really hungry (nonexample)

- Completing a 3-mile cross-country race even though you were out of breath and dead tired after less than a mile (example)

6. Have students present examples and nonexamples of the concept, have them explain why they are examples or nonexamples, and give them feedback on their examples, nonexamples, and explanations.

The second procedure I suggest for teaching new and challenging concepts was described by Nagy (1988). It requires less teacher time, although it still requires a good deal of class time. I have named it Focused Discussion. In the following discussion, the key concept is stereotype.

Focused Discussion

Divide the class into two groups, assigning a recorder for each group. The groups will each be brainstorming word associations. One group should brainstorm as many words or phrases as they can connect with the word city. The other group should brainstorm words or phrases connected with the phrase small towns. The recorder in each group should write down the words and phrases brainstormed.

After giving the groups about 3 minutes for the brainstorming session, ask each recorder to read the group’s list. Encourage students to ask questions about the words and allow them to express further ideas about the aptness of the words on their lists. Then introduce the concept of stereotype to the students, explaining it in terms of oversimplified and formulaic views and attitudes about people, places, and institutions. Ask the students whether or not any of the ideas on their lists reflect stereotypes of big cities or small towns and the people who live in them. Spend some time discussing stereotypes, noting that people and places do not often fit the stereotyped images used to describe them (Nagy, 1988, p. 22).

Semantic Mapping

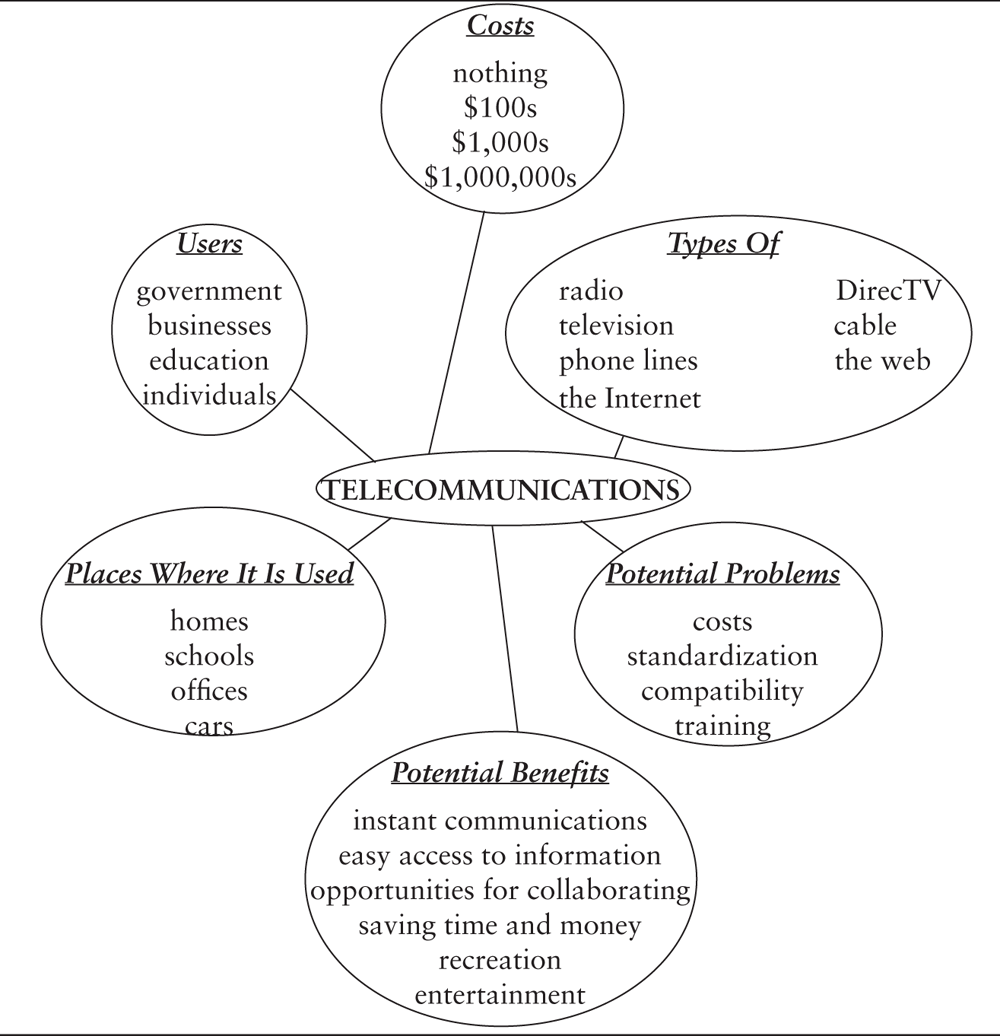

The third method of teaching words representing new concepts I recommend is Semantic Mapping (Heimlich & Pittelman, 1986). With this method, the teacher puts a word representing a central concept on the chalkboard; asks students to work in groups listing as many words related to the central concept as they can; writes students’ words on the chalkboard grouped in broad categories; has students name the categories and perhaps suggest additional ones; and discusses with students the central concept, the other words, the categories, and their interrelationships. Figure 5.2 shows a semantic map for the word tenement that students might create before or after reading a social studies chapter on urban housing.

Figure 5.2. Semantic Map for the Word Tenement

Figure 5.3. Semantic Map for the Word Telecommunications

Figure 5.3 shows a semantic map for the word telecommunications. Since many students know a good deal about telecommunications, it might work well for them to begin the map before reading a selection dealing with the topic and then complete the map after they have read the passage.

Teaching concepts with the Frayer Method, Focused Discussion, or Semantic Mapping takes a good deal of time. These methods also require a good deal of thought on the part of both you and your students. However, the fruits of the labor are well worth the effort, for with these methods students can gain a new idea, another lens through which they can interpret the world. Additionally, it is important to remember that if you have a difficult concept that students need to learn, teaching it is going to take some time. Teaching a new and difficult concept as though it is merely a new label—for example, teaching it using the Context-Dictionary-Discussion Procedure—will not get the job done.

Methods Particularly Appropriate for Social Studies, Math and Science, and Literature

Here, I describe three methods. All three provide in-depth instruction. The first, the Six-Step Procedure, is particularly appropriate for social studies. The second, Examining Conceptual Networks, is particularly appropriate for math and science. The third, Rich Instruction, is particularly appropriate for literature. However, the fact that they are particularly appropriate for these subject areas does not mean they are inappropriate for other subject areas. They can be useful whenever in-depth instruction is called for.

The Six-Step Procedure

The Six-Step Procedure was developed by Marzano (2004) to use for vocabulary instruction in content areas. Here is a slightly modified version of the procedure along with a middle school example based on one Marzano provides for the term deductive reasoning:

- Provide a description, explanation, or example of the new term.

Deductive reasoning is a thinking process that begins by considering what is known and then proceeds to identifying what must be true but is not stated. - Ask students to restate the description, explanation, or example in their own words and record these in notebooks.

One student might restate the definition like this: “Sometimes you can show that something must have happened because some other things happened before it. You can prove things using deductive reasoning” (Marzano, 2004, p. 96). - Ask students to construct a picture, symbol, or graphic representing the term and add these to their notebooks.

A student might draw a flowchart with arrows going from the heading “Things You Know Are True” to several blocks representing things that are true and then arrows going from those blocks to the heading “This Must Be True Because of the Things Above.” - Engage students periodically in activities that help them add to their knowledge of the terms in their notebooks.

Ask students to describe a time they have used or could use deductive reasoning and add those descriptions to their notebooks. - Periodically ask students to discuss the terms with one another.

Ask students to share their examples of using deductive reasoning in small groups and to identify any questions or confusions that come up and to share these with the class to get them cleared up. - Involve students periodically in games or other activities that allow them to play with and manipulate the terms.

Engage students in a Pictionary-like game with deductive reasoning and other terms they have been working. Have students in timed small groups draw pictures of the terms. Then have the small groups take turns presenting their pictures to the large group. The winner is the group whose picture elicits the term it represents in the shortest time.

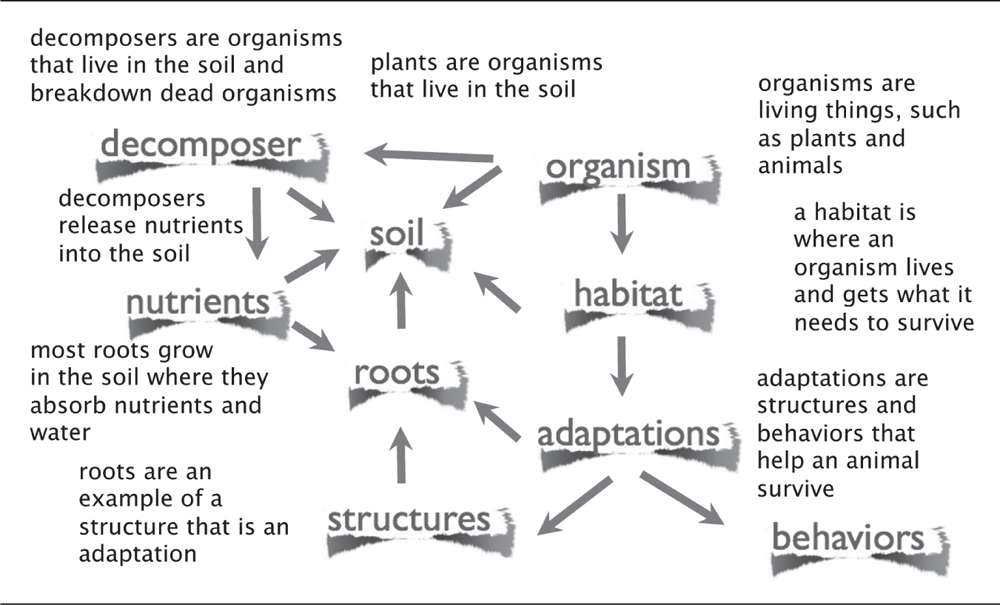

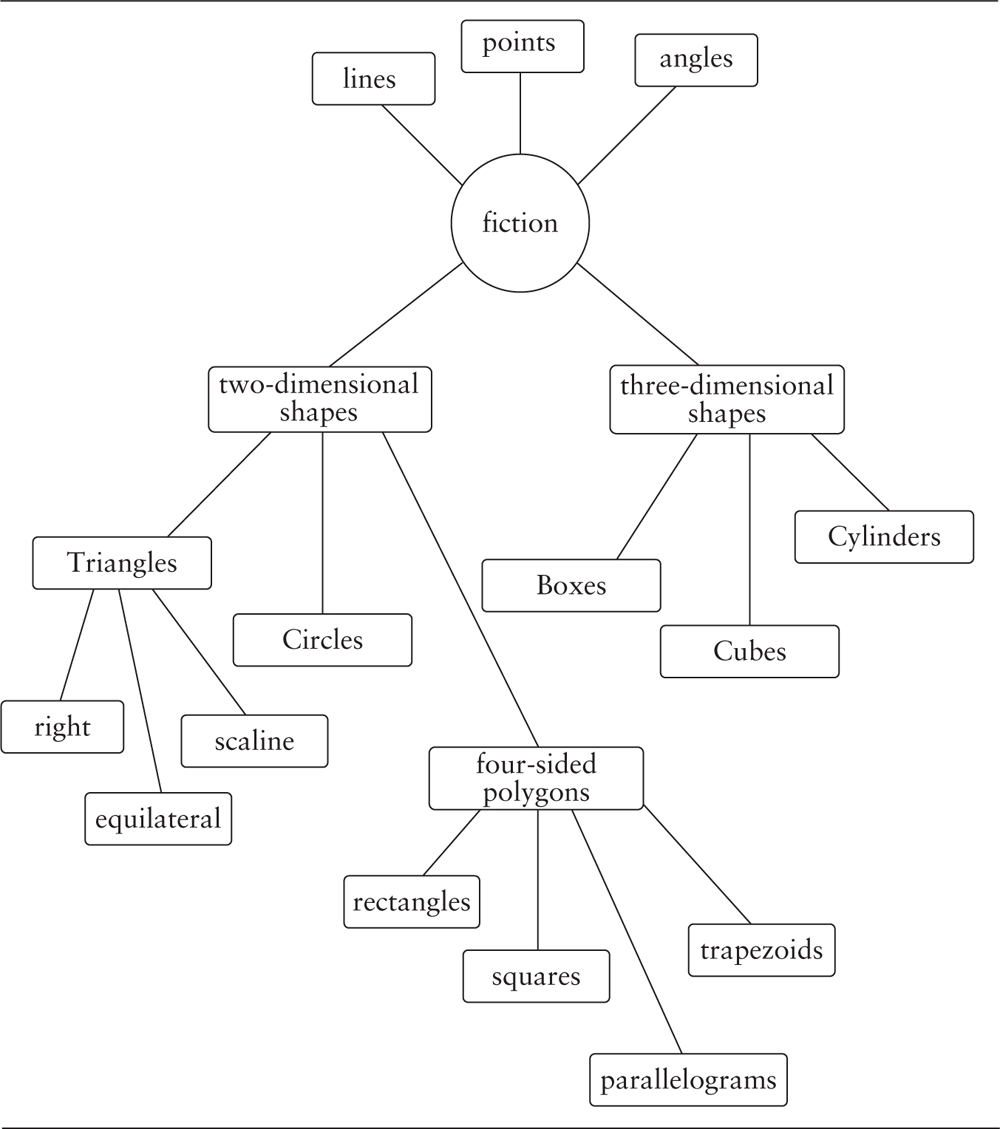

Examining Conceptual Networks

The procedure of Examining Conceptual Networks is much like Semantic Mapping, except that there is no designated set of steps like those I described for Semantic Mapping. A conceptual network is a group of interrelated concepts. Typically, networks are displayed graphically with a series of lines connecting the concepts, and the lines are labeled to show the relationships between them. As Pearson (2009) has pointed out, “Learning the academic language of science means forming rich conceptual networks.” The same is true of math, social studies, and many other disciplines. Words, and sometimes phrases, are labels for concepts and ideas. Because of this, Pearson continues, “Excellent vocabulary development is nearly indistinguishable from vigorous subject matter teaching.” Figure 5.4 presents a conceptual network for a unit on soil habitats taken from the Seeds of Science/Roots of Reading program (www.scienceandliteracy.org), a science and reading program for grades 2–5, and Figure 5.5 presents a conceptual network of geometric shapes that might be used in a middle school geometry class.

Figure 5.4. Conceptual Network for Soil-Habitat Vocabulary

Figure 5.5. Conceptual Network for Geometric Shapes

As I noted, there is no designated set of steps for Examining Conceptual Networks. What is important, however, is that the process be interactive and involve a good deal of student thought about the concepts under consideration and their interrelationships as well as a good deal of student talk. Here are a few ways in which the networks shown in the above figures might be examined: As one possibility, you could present the soil-habitats network without any labels at the beginning of a unit, put a version of it on the wall throughout the unit, and have students identify the relationships among the concepts, add them to the graphic, and support their additions with evidence from the text they are reading or other sources as the unit progresses. As another possibility, you could present the geometric-shapes network at the beginning of a geometry course, tell students that they will be studying each of these shapes over the course of the semester or year, and as the course progresses, have them keep and share notebooks in which they describe the various shapes and how they are both related to and different from each other. As a third possibility, you could present the geometric-shapes network with just some of the concepts (perhaps shapes, two-dimensional shapes, three-dimensional shapes, points, lines, angles) entered, and have students fill in and define the other concepts as the course progresses.

Rich Instruction

Rich Instruction is designed to give students deep and lasting understanding of word meanings. It can also be used to teach new concepts if the concepts are not too difficult and students have some information related to them. The procedure has been described in several publications by Beck and McKeown and their colleagues (Beck, Perfetti, & McKeown, 1982; Beck et al., 2002, 2013; McKeown & Beck, 2004) and has taken several forms. Here is a version that can be used in a number of situations. For the sake of simplicity, this example deals with a single word—ambitious. Usually, however, Rich Instruction is used to teach a set of words.

- Begin with a student-friendly definition.

- ambitious—really wanting to succeed at something

- Arrange for students to work with the word more than once. One encounter with a word is very unlikely to leave students with a rich and lasting understanding of its meaning. Two is a minimum, but more are desirable.

- Provide the word in more than one context so that students’ understanding is not limited to one situation. The several contexts need not come at the same time.

- Susan’s ambition to become an Olympic high jumper was so strong that she was willing to practice 6 hours a day.

- Rupert had never been an ambitious person, and after his accident he did little other than watch television.

- Engage students in activities in which they need to deal with various facets of the word’s meaning and in investigating relationships between the target word and other words.

- Would you like to have a really ambitious person as a friend? Why or why not?

- Which of the following better demonstrates ambition? (1) A stockbroker gets up every day and goes to work. (2) A stockbroker stays late at work every day, trying to close as many deals as possible before leaving.

- How likely is it that an ambitious person would be lethargic? How likely is it that an ambitious person would be energetic? Explain your answers.

- Have students create uses for the words.

- Tell me about a friend who is very ambitious. What are some of the things she does that show how ambitious she is?

- Encourage students to use the word outside of class.

- Come to class tomorrow prepared to talk about someone who appears to be ambitious. This could be a stranger you happen to notice outside of class, someone in your family, someone you read about, or someone you see on TV.

Teaching New Meanings for Known Words

New meanings for known words may or may not represent new concepts for students. If the new meanings do not represent new and difficult concepts, the procedure for teaching new meanings for known words is fairly simple and straightforward. The approach termed Introducing New Meanings is one appropriate method.

Introducing New Meanings

- Acknowledge the known meaning.

- Give the new meaning.

- Note the similarities between the meanings (if any).

Product

- something made by a company

- the number made by multiplying other numbers

- The similarity is that in both instances something is produced or made by some process.

Wax

- a material used to make candles and polish things

- to grow bigger

- In this case, there does not appear to be any similarity in the meanings.

If the new meanings to be learned represent new and difficult concepts, then one of the methods described earlier for teaching concepts—the Frayer Method, Focused Discussion, or Semantic Mapping—is likely to be more appropriate.

Clarifying and Enriching the Meanings of Known Words

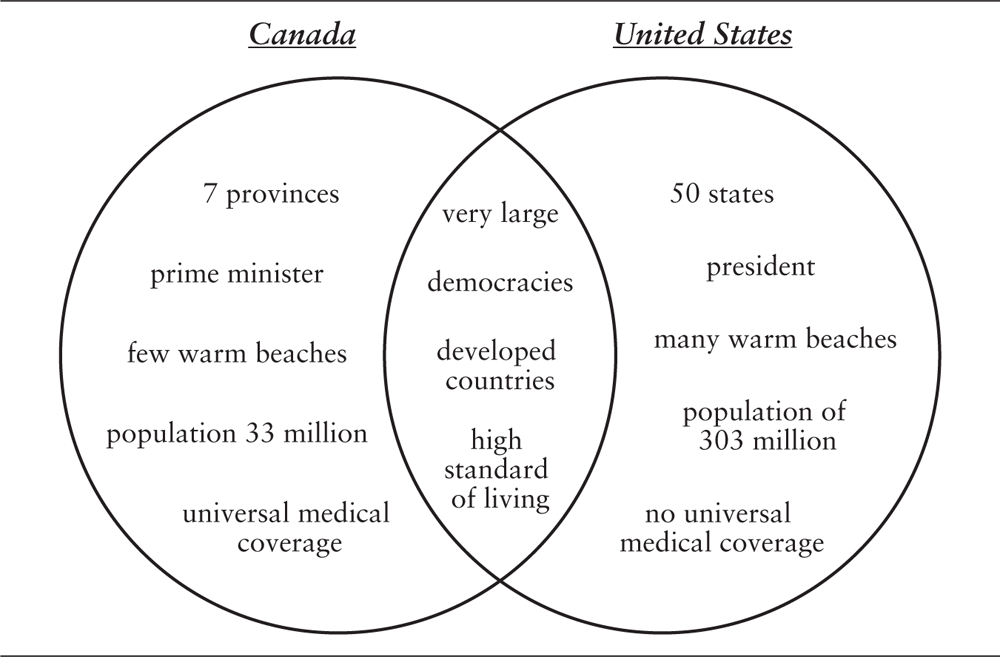

Here, I present a simple, straightforward, and frequently used approach to clarifying and enriching the meanings of known words—Venn Diagrams.

Venn Diagrams

Venn Diagrams are an excellent vehicle for clarifying and extending word meanings. With Venn diagrams, you typically investigate the meanings of two words, in the process figuring out which attributes the words share, which are exclusive to one word, and which are exclusive to the other word.

- Choose two words with similar but not precisely the same meanings.

- Draw an empty Venn Diagram, two overlapping circles, on the chalkboard or an overhead.

- Discuss the meaning common to both words and the meaning unique to each word, and fill in the Venn Diagram accordingly.

- Alternately, students can complete Venn Diagrams in pairs or small groups and share their findings with the class.

Figure 5.6 shows a Venn Diagram for the terms short stories and essays that might be used in the elementary grades, and Figure 5.7 a Venn Diagram for the terms Canada and the United States that might be used in middle school.

Moving Words into Students’ Expressive Vocabularies

Students can be encouraged to move words into their expressive vocabularies by your providing a model of precise word use, your encouraging students to employ precise and mature words in their speech and writing and recognizing appropriate diction when they display it, and your providing time and encouragement for various sorts of wordplay that prompt students to work with words they might otherwise not speak or write. Probably the best opportunity to help students build their expressive vocabularies is when they are honing their writing or finalizing relatively formal oral presentations. One of the last steps that professional writers and public speakers take in finalizing their work is to examine their word choices. Doing so might involve students asking and answering several questions about the words they have used.

Figure 5.6. Elementary-Grade Venn Diagram for Short Stories and Essays

Figure 5.7. Middle-School Venn Diagram for Canada and the United States

Some Questions About Word Choices

- Do the words I have used precisely convey my meaning?

- Are they at an appropriate level of sophistication for my audience?

- Are they appropriately forceful and colorful for my topic?

In addition to routinely emphasizing the importance of the words students use in their speech and writing, it makes good sense to occasionally put the spotlight on words in some concentrated and robust instruction. Duin (Duin & Graves, 1987, 1988) developed and tested an approach to such concentrated and powerful instruction modeled on Beck and Mc Keown’s Rich Instruction, which I described earlier in this chapter. Duin’s approach, termed Expressive Vocabulary Instruction, can be used with upper elementary through junior high students to focus their attention on the words they use in their writing over a period of a week or so.

Expressive Vocabulary Instruction

- Words are taught in groups of around 10 related words presented over a period of 3–6 days. The words are not necessarily semantically related, but they do lend themselves to writing on a particular topic. A set of words Duin has used with an essay about space includes feasible, accommodate, tether, criteria, module, retrieve, configuration, and quest.

- Students work extensively with the words, spending about half an hour a day with the 10 to 15 words taught during the 3 to 6 days of instruction and doing 5 to 10 activities with each word.

- Instruction is deliberately varied in order to accomplish various purposes. Students define words, use them in sentences, do speeded trials with them, make affective responses to them, compare them to each other and to other concepts, keep a written record of their work with them, are encouraged to use them outside of class, and do several short writing assignments with them.

- Examples of the tasks Duin has used include the following: Students discussed how feasible space travel might be for them in the near future. They were asked if they thought their school could find a way to better accommodate handicapped students. They distinguished between new words, such as retrieve, and related words, such as return, by filling in sentence frames with the more appropriate of the two words. They wrote brief essays called “Space Shorts” employing the words in dealing with such topics as the foods that would be available in space, and judged each others’ use of the words.

Duin’s work has indicated that students working with this sort of instruction use a substantial proportion of the taught words in essays targeted to using the words and that the essays of students who have received the instruction are judged markedly superior to those of students who have not received it. Equally important, her work has shown that students thoroughly enjoy learning and using words in this way. These findings can be taken as a recommendation for helping and encouraging students to experiment with new, precise, and vivid vocabulary in their writing.

SELECTING AMONG THE METHODS AND TEACHING VOCABULARY TO IMPROVE READING COMPREHENSION

In the preceding section, I discussed seven different word-learning tasks and over a dozen instructional procedures. Although this is a lot of procedures and there is wide agreement that different procedures are needed for different tasks (Graves, 2014; Kamil & Hiebert, 2005; National Reading Panel, 2000; RAND Reading Study Group, 2002), I do not want to suggest that choosing a procedure should be difficult and time consuming. Nor is it the case that only one procedure is appropriate in any one situation. For example, the Context-Relationship Procedure, one of the procedures I suggest in the section on Teaching New Words Representing Known Concepts can be used for teaching new concepts as long as the new concepts are not too difficult. Similarly, Semantic Mapping, one of the procedures I suggest in the section on Teaching New Words Representing New Concepts, can also be used for clarifying and enriching the meanings of known words. It is probably a good idea to initially use only a few of the procedures and use them repeatedly, so that both you and your students are familiar with them. Then, over time, you can introduce additional procedures and get your students familiar with them. Moreover, when you are preteaching vocabulary before students read a section—something that you are likely to do frequently—you will probably use only one or perhaps two procedures even though the words you are teaching represent somewhat-different learning tasks. Using more than one or two procedures at one time is likely to become cumbersome and is not necessary.

The topic of preteaching vocabulary leads naturally to the topic of teaching vocabulary to improve comprehension, a frequent and very important goal of vocabulary instruction. The richer the instruction is, the more thoughtful processing it requires of students, the more thoughtful discussion it requires, and the more it is focused on important content of the selection that students are reading or are about to read, the greater the likelihood that the instruction you provide will improve students’ comprehension of the selection they are reading or are about to read. Thus, procedures like the Frayer Method, Focused Discussion, Semantic Mapping, the Six-Step Procedure, Examining Conceptual Networks, and Rich Instruction are particularly likely to improve comprehension. At the same time, all of these procedures take valuable classroom time, and you will need to decide when to use these more powerful and more time-consuming procedures and when some less powerful and less time-consuming ones will be more appropriate.

REPETITION AND REVIEW

No matter how well we initially teach a word, it is much more likely that students will internalize and remember the word if they see it again and, better yet, actively work with it in a review. Sometimes, review can be very brief and simply embedded in class discussion. For example, noting that the word catastrophic, which you have previously taught, appears again in the selection students are reading, you might say something like, “You might have noticed that the word catastrophic, which we learned several weeks ago, comes up again in today’s chapter. Again, a catastrophic event is a really serious event, something that would produce widespread damage, like a hurricane might.”

At other times, repetition will involve specific procedures. Here are three time-efficient procedures for reviewing words students have already been taught.

Anything Goes

With Anything Goes (Richek, 2005), you begin by prominently displaying the words to be reviewed where everyone in the class can see them and explaining to students that occasionally you are going to point to some of the words displayed and ask questions about them. For English learners, it is helpful to include a picture of the word or a first-language cognate or translation of the word. Often you’ll post a particular set of words for a week, but you can certainly put them up for a longer or shorter period. Once the words are posted, you can ask students to do any of the following:

- Define the word

- Give two of its meanings

- Use it in a sentence

- Give an example of the thing named or described by the word

- Say where you would find the word or the thing named or described by the word

- Explain the difference between two of the words, or between one of the words on the list and some other word

- Give the past tense, plural, or -ing form of a base word

- Give the root of words with prefixes or suffixes

- Give prefixed or suffixed forms of root words

Note that you certainly wouldn’t use all of these with any one word. You’ll typically use two or three of them with each word—whatever seems enough. Suppose the list included 10 words, including melody, agenda, and mention. You might ask students to define melody, give an example of a melody, and say where they might hear a melody. Then, you might ask them to use agenda in a sentence, tell you where they are likely to find an agenda, and say the plural of agenda. After that, you might ask them to use the word mention in a sentence, tell you something that they might mention to a friend, and explain the difference between “mentioning” something and “discussing” something.

Once you have worked with Anything Goes enough that you think most of your students understand the way it works, you may want to post the list of prompts on the board, discuss them, and invite students to sometimes do the prompting. If you do this, you can save class time by sending the list home with students and asking them to prepare prompts for two or three of the words. Of course, you can always make generating prompts group work. The time the groups spend generating prompts is likely to be well spent, although this will increase the time spent on the review significantly.

Connect Two

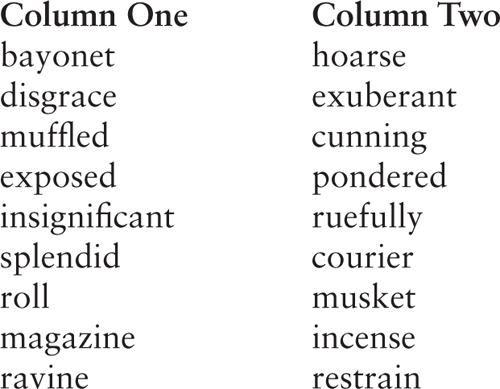

With Connect Two (Blachowicz, 1986; Richek, 2005), you give students two columns of perhaps 10 words each, and ask them to identify similarities or other relationships between a word in column one and a word in column two. Here are some words that Richek has used to illustrate the procedure:

Children may at first come up with relationships that are superficial, such as that bayonet and cunning have the same number of letters. That is fine to start with, but what you want to encourage the children to do is search for meaningful relationships that require deep processing. Modeling can be useful here as it so frequently is, so you may want to explain that you are looking for deeper relationships and model a few of those. You might, for example, note that muffled and hoarse have to do with sound, that a person is not likely to be exuberant about being disgraced, and that a bayonet might be attached to a musket. Soon, children with begin finding meaningful relationships, and the thought processes they engage in while doing so will help them remember the words and deepen their understanding of them.

Word Wizard

Word Wizard (Beck et al., 1982) was developed some years ago and is now widely used. It is almost too simple. You give students a list of the words they are reviewing and ask them to find the words used outside of class. When students find a word, they record the context in which it was used and report their findings to the class, earning a point for each instance they report.

In their work, which was with 4th graders, Beck and her colleagues (1982) went all out to make Word Wizard a big deal. They first advertised the notion by creating and distributing leaflets titled “You Can Be a Word Wizard.” One part of the leaflet, which included engaging graphics, described what a Word Wizard was and the various levels of word wizardry students could achieve by earning points by finding the words they were learning in class outside of school. These included Word Wildcat, Word Whirlwind, Word Winner, Word Worker, and Word Watcher, along with the ultimate level, Word Wizard. Another part of the leaflet explained how points are earned:

If you hear a word—on TV, on the radio, on the street, or at home [today of course we would add on a video, a CD, your iPod, or the Internet]—you can earn one point. Just tell your teacher where you heard or saw the word and how it was used (Beck et al., 2002, p. 119).

On the back of the leaflet, students were reminded to look for their name on the Word Wizard chart. The Word Wizard chart was a large and colorful chart with students’ names and space for tallying their sightings of words. In class, students’ sightings were heartily celebrated, and much was made of their efforts. All in all, the activity was really well received by the students and engendered a lot of interest in vocabulary. In fact, Beck and her colleagues noted that the children had a terrific time locating and bringing in the words. And the procedure isn’t just for challenging words like those Beck and her colleagues used. Richek reported success with the procedure when a primary-grade EL teacher used it to reinforce common words like bed, table, and television.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Although teaching individual words is only one part of a comprehensive vocabulary program, it is a very important part. It is also a relatively complex part in terms of both planning and delivering the instruction. Planning involves recognizing the part that teaching individual words plays in students’ overall vocabulary development, considering the levels of word knowledge you want students to achieve, and selecting vocabulary to teach. Instruction involves identifying the word-learning task or tasks represented by the words you are teaching, choosing an appropriate method or methods of instruction, and of course creating and providing that instruction. My goal in the chapter has been to provide you with the information you need to do all of this and do it well.

Thus far in the chapter, I have concentrated on appropriate approaches for teaching individual words. Unfortunately, there are also a number of inappropriate approaches, and some of these are widely used. In concluding the chapter, I briefly list several things not to do when you teach vocabulary.

Things Not to Do in Teaching Vocabulary

- Give students words out of context and ask them to look them up in the dictionary

- Have students do speeded trials with individual words

- Have students complete word mazes

- Teach words as though they were merely new labels for existing concepts when in fact they represent new and challenging concepts

- Teach spelling when you mean to be teaching vocabulary (Teaching spelling is certainly important, but teaching both spelling and vocabulary will require more time than teaching only vocabulary. You need to decide when you want to spend that additional time.)

- Assume that context will typically yield precise word meanings

In this chapter, I have described a number of things that you, the teacher, can do to teach words. In the next chapter, I describe ways in which you can teach children to learn words on their own.