CHAPTER 4

Providing Rich and Varied Language Experiences

You can’t build a vocabulary without reading. You can’t meet friends if you … stay at home by yourself all the time. In the same way, you can’t build up a vocabulary if you never meet any new words. And to meet them you must read. The more you read the better. A book a week is good, a book every other day is better, a book a day is still better.

—Rudolf Flesch and Abraham Lass, Professional Writers

This chapter has two major purposes. The first is to emphasize the fact that, since most words are learned incidentally, students need to be immersed in rich reading, listening, discussion, and writing experiences throughout the school day. Given the size of the vocabularies that students eventually acquire—receptive vocabularies of something like 50,000 words by the time they graduate from high school—only a small number of the words students need to learn can be directly taught. Thus, we need to do everything possible across students’ 13 years of schooling to facilitate and encourage activities that will support incidental word learning. The first section of the chapter describes such activities.

The second purpose of the chapter is to stress that during the primary grades most of the new words children learn will come from listening and discussion, and to describe some powerful approaches to building vocabulary through listening and discussion. Building vocabularies through listening and discussion is important for both students who arrive at school with substantial vocabularies and those who arrive at school with relatively small vocabularies. Children who come to school with substantial vocabularies will not learn many new words from the reading they do because the books they are able to read in kindergarten and 1st–2nd grades are made up largely of words that are already in their oral vocabularies. Building their vocabularies through listening and discussion is even more crucial for children who come to school with relatively small vocabularies, a situation faced by many children living in poverty and many English learners. These children need to build their oral vocabularies in order to acquire a bedrock of oral vocabulary on which they can build their reading vocabularies and catch up with their peers (Hart & Risley, 1995, 2003; Hiebert, 2014; Neuman & Wright, 2014).

Ensuring that all children, both those who come to school with rich vocabularies and those who come to school with smaller vocabularies, develop vocabularies of breadth and depth has always been important. However, the adoption of the Common Core has made it even more important because one of the central tenets of the Common Core is that all children need to be reading grade-level material. Children cannot read grade-level material without developing grade-level vocabularies, and many children need to substantially build their stores of words to achieve grade-level vocabularies.

The chapter is divided into three sections. The first section describes ways of promoting incidental word learning. The second section describes a well-researched procedure for building primary-grade children’s oral vocabulary and several versions of that procedure. The third section describes word-consciousness activities for the primary grades.

PROMOTING INCIDENTAL WORD LEARNING

In the quotation that introduces the chapter, Flesch and Lass (1996) make a hugely important point. Children cannot build rich and powerful vocabularies without reading a great deal. In fact, over time, wide reading makes the single largest contribution to vocabulary development, much more than does listening, discussion, or writing. When I first developed the four-part approach to vocabulary development described in this book, this part of the program was titled “Promoting Wide Reading.” However, I have since changed that title because wide reading is not the only language experience students need to build rich and deep vocabularies. In addition to reading widely, students need other language experiences: They need to hear spoken language in a wide variety of situations. They need to engage in frequent discussions in which they interact with other students, with teachers, and with other mature language users in real communicative situations. And they need to write a lot, for writing provides students with the opportunity and the incentive to really focus on words and choose just those words that will best convey their intended message to their intended audience. This attention to listening, reading, discussion, and writing is another feature of this chapter consistent with the Common Core, which emphasizes the interrelatedness of the language arts. In the remainder of this section, I briefly discuss promoting incidental word learning though listening, reading, discussion, and writing.

Listening

In promoting students’ incidental word learning through listening, your most powerful tool is the vocabulary you use in the classroom. Whatever grade level you teach, it is worthwhile making a deliberate effort to include some new and somewhat-challenging words in your interactions with students. As I stressed in Chapter 3, identifying words to focus on as you interact with students is no mean task, but the goal is clear. You want to introduce children to some new and somewhat-challenging words, to repeatedly pique their interest in words. By “new and somewhat-challenging words,” I generally mean words the Common Core would categorize as general academic vocabulary, words that are new to students but that do not represent new and challenging concepts. General academic vocabulary consists of words that are used across domains—for example, in English, and history, and science—and not just in a single domain such as health or music. Of course, what constitutes new and somewhat-challenging words differs from one grade level to another and for students with various levels of word knowledge. The ones to focus on are those that are not known by many students in your classroom and are thus a bit of a stretch. For typical primary-grade students, these might be words like commotion, prowl, and timid. For typical middle-grade students, they might be ones like adjacent, exuberant, and ponder. And for typical secondary students, they might be ones like abstruse, extricate, and sophistry. For students with smaller vocabularies, some of the words to focus on should be more frequent and less sophisticated. However, students with smaller vocabularies also need to learn the sophisticated words their peers are learning.

Note that at this point I am not talking about teaching these words, I am simply talking about using somewhat-challenging words from time to time, sometimes pausing to explain their meanings but often just letting students hear them. For example, you might tell a group of 7th graders who have just come in from lunch and brought with them their cafeteria conversations that the cacophony they have brought in with them will not be needed that afternoon. The goal is to expose students to some new and challenging words and to pique their interest in such words.

Reading

In promoting students’ incidental word learning through reading, considerations include recognizing the importance of wide reading, helping students select books and other texts that will promote vocabulary growth, and facilitating and encouraging their reading widely. Most words are learned from context, and the richest context for building vocabulary for students beyond the primary grades is books. Books, as Stahl and Stahl (2004) point out, are “where the words are.” Testimony to that fact is shown in Figure 4.1. As can be seen, even children’s books contain about one-third more rare words than prime-time adult TV shows and nearly twice as many rare words as adult conversational speech. If we want to help students increase their vocabularies, we need to get them to read more (Anderson, Wilson, & Fielding, 1988; Elley, 1996). Some reading, of course, can and should be done in class. I very strongly recommend some sort of in-class independent reading program in the elementary grades, particularly if the students are not avid readers. But there is only so much class time available. To really build their vocabularies, students need to read a lot outside of school. Unfortunately, both my informal conversations with teachers and students and empirical evidence indicate that many children do very little reading outside of school (Anderson et al., 1988; National Assessment of Educational Progress, 2003; United States Department of Labor, 2014) and that students who fail in reading also do not do a lot of reading in school (Allington, 1977, 2009). For example, in their study of how 5th-grade students spend their time out of school, Anderson and his colleagues (1988) found that 50% of the children read from books less than 4 minutes a day and 30% of the children read from books less than 2 minutes a day. Similarly, data gathered as part of the National Assessment of Educational Progress (2003) showed that about one-fourth of the students questioned reported reading no books outside of school in the previous month. Finally, a recent survey by the United States Department of Labor (2014) indicated that on the average teenagers read for only about 8 minutes per day.

Figure 4.1. Frequency of Rare Words in Various Sources

The starting point for encouraging wide reading is a well-stocked classroom library, a library with books that you know well, books appropriate for the various levels of readers in your classroom, and books that include appropriately challenging vocabulary. As Figure 4.1 suggests, newspapers and magazines are also valuable parts of the classroom library, and are likely to contain the sort of challenging words students need to learn. While nothing can replace the immediacy and convenience of a classroom library, as children progress through elementary school and into the secondary grades, school and community libraries become increasingly important. Unfortunately, in poorer neighborhoods, classroom libraries, school libraries, and even community libraries are likely to have very meager resources (Neuman & Celano, 2001). Thus, one task that teachers, schools, and communities face is doing everything possible to make books widely and conveniently available for students.

But just having books available is not enough. Something must be done to entice children to read the books. Many possibilities exist here. Teachers of young children can read books aloud and then invite children to take the books home to reread. Teachers at all grade levels can read parts of books in class and encourage students to read the rest of the book at home. Teachers at all grade levels can give book talks that preview and advertise books the same way movie previews advertise upcoming films. Students can be encouraged to share the books they read with each other. Teachers can become familiar with individual student’s interests and with individual books and thus recommend particular books to particular students. Students can be required to do some reasonable amount of reading outside of class. Some sort of in-class independent reading activity can be undertaken, particularly for students who, even with all of your efforts, are not likely to do much reading outside of school. Whether you call it DEAR (Drop Everything and Read), SSR (Sustained Silent Reading), or USSR (Uninterrupted Sustained Silent Reading), for students who do not read much out of school, some sort of ongoing, structured, long-term in-school silent reading program is an essential element. So too are summer reading programs such as that described by White, Kim, Kingston, and Foster (2014).

Discussion

I turn now to promoting students’ independent word learning through discussion. The key to having discussions that will prompt students to use more sophisticated vocabulary is to give them meaty and somewhat academic topics to talk about. As shown in Figure 4.1, casual conversations, even casual conversations among college graduates, do not include a lot of sophisticated vocabulary. If students are going to use sophisticated words, they need to discuss sophisticated ideas and to read multiple sources on a topic. This means talking about academic topics that students spend some time on and gain familiarity with—topics they are reading about, investigating in the library and on the Internet, and, when possible, writing about. Such discussions might focus on science topics such as the ecology of freshwater lakes, social studies topics such as barriers to ordinary people running for public office, and sophisticated literary topics such as the motivations that prompt a character’s action. Some sources of meaty discussion topics include Wiggins and McTighe’s Understanding by Design (2005), their Understanding by Design Guide for Creating High High-Quality Units (2011), and Wiske’s Teaching for Understanding (1998).

Writing

The keys to promoting students’ independent word learning through writing are similar to those for discussion. Students need to write about topics that they care about, that they have spent some time on, and that are at least somewhat sophisticated. They also need to write with a purpose and for an audience. This is the case because it is only when you are writing with a real purpose and for an audience that you have identified and care about that you are likely to ask the most important questions about the words you use in your writing: Here, for example, are some questions you might pose about words to middle and secondary school students:

- Does this word really capture my meaning?

- Is it the very best word to say just what I want to say?

- Will the people to whom I am writing understand this word?

- Will they find this word appropriately formal or informal as the situations demands?

Similar, but simpler, questions can be used with younger students. The goal is to get students to realize that the words they use in their writing are very important, that the words they use will affect both the clarity of what they write and the reaction their writing receives from others, that they should choose and use words wisely, and that honing their word choices should be one of the last steps in editing their writing.

In concluding this section on promoting incidental word learning, I want to make a point that has recently been stressed by Dickinson (2014) and by Neuman and Wright (2014). We need to begin promoting word learning long before children arrive at kindergarten, because a great deal of learning takes place (or fails to take place) well before children enter school. Although the Dialogic Reading procedure described later in this chapter is targeted toward preschool students, this book deals primarily with instruction for school-age children. Both Dickinson and Neuman and Wright, however, suggest some excellent procedures for use with preschool children.

DIRECTLY BUILDING PRIMARY-GRADE CHILDREN’S ORAL VOCABULARIES

In this second major section of the chapter, I turn from the matter of indirectly promoting word learning, something that is necessary for all students at all grade levels, to directly building children’s oral vocabularies, something necessary in the primary grades, particularly for children who enter school with small vocabularies. In kindergarten, most children can’t read. And in 1st and 2nd grade, they certainly do not read a lot. Moreover, as I mentioned earlier in the chapter, most of the books that primary-grade children read themselves include relatively few words that are not already in their listening vocabularies (Biemiller, 2004; McKeown & Beck, 2004). If children are going to learn really new words, words that are not already in their oral vocabularies, they are going to have to learn them through oral language activities. And the most powerful oral language activity that has been developed for use in classrooms is interactive oral reading.

Characteristics of Effective Approaches to Interactive Oral Reading

Over the past 30 years, there have been a number of naturalistic studies of mothers reading to their preschool children. And over the past several decades, there have been a number of experimental studies in which researchers, teachers, parents, and aides used specific procedures in reading to children with the goal of building their vocabularies, comprehension, and language skills more generally. Here, I call these approaches “interactive oral reading.” The approaches used in effective interactive oral reading studies have a good deal in common and suggest the general characteristics of effective procedures for building vocabulary in this way. On the following few pages, I discuss these characteristics and give some examples of them, drawing on the work of De Temple and Snow (2003) and Neuman and Wright (2014), as well as on my own experiences and synthesis of the literature.

In effective interactive oral reading, words are explicitly defined. The teacher provides student-friendly definitions or explanations of the words. For example, after reading the sentence “When Anansi said the word seven, a peculiar thing happened,” you might say, “Peculiar means strange or different” (Neuman & Wright, 2014). These definitions can come before the reading, during the reading, or after the reading; and they often come more than once.

Effective interactive oral reading requires carefully selected books and carefully selected words. The books need to be interesting and enjoyable for children, and they need to stretch children’s thinking a bit. Of course, the books also need to include some challenging words that are worth studying and will enhance children’s vocabularies. The difficulty of the books will differ markedly depending on the oral vocabularies of the children you are working with. For example, the stories written for The First 4,000 Words (Graves, Sales, & Ruda, 2008), one of the programs described later in the chapter, are about 200 words long and written for children just beginning to read. As another example, Valerie Flournoy’s The Patchwork Quilt, one of the books used in the Text Talk program (Beck & McKeown, 2005), another program described later in the chapter, is 25 pages long and designed for 2nd or 3rd graders.

Effective interactive oral reading is deliberately interactive. Both the reader and the children play active roles. The reader frequently pauses, prompts children to respond, and follows up those responses with answers and perhaps more prompts. Children respond to the prompts or questions, elaborate in some of their responses, and perhaps ask questions of their own. Additionally, the interactions are frequently supportive and instructive (Weizman & Snow, 2001). In other words, the reader scaffolds children’s efforts to understand the words and the text, as illustrated in the following excerpt:

5-Year-Old Child and His Mother Reading Jill Murphy’s What Next, Baby Bear!

Child: I want to have … what are those? Those are those are little little um volcanoes.

Mother: Little volcanoes. Well yeah. Kind of. They’re craters.

Child: Craters?

Mother: Yeah.

Child: And the fire comes out of it?

Mother: No. They just look like volcanoes but they’re not.

Child: Yeah, they’re on the moon.

Mother: Yeah. (Taken from De Temple & Snow, 2003, p. 27).

Effective interactive oral reading usually involves reading the book several times. This allows the children and the reader to revisit the same topic and the same words several times, and it allows the children to begin actively using some of the words they have heard and perhaps had explained in previous readings.

Effective interactive oral reading directly focuses children’s attention on a relatively small number of words. Most programs focus on 5–10 words per book, although one program discussed later in this chapter teaches 24 words per book. As noted, in some cases, the word work comes during the first reading, in some cases during subsequent readings, in some cases after the book has been read, and in most cases more than once.

Effective interactive oral reading requires the adult readers to read fluently, with appropriate intonation, and with expression. Skilled adult readers effectively engage children using an animated and lively reading style.

Effective interactive oral reading requires that students repeatedly encounter the words taught. Not only must students encounter the words several times during the interactive oral reading lessons, they must also frequently encounter the words after they have initially learned them, and they must encounter the words in varying contexts. There is no solid information on just how many times a student needs to encounter a word to solidify his knowledge of it. That number will differ hugely with different students and different words. However, setting a goal of 20 repetitions would be reasonable.

Neuman and Wright (2014) provide the following useful list of key steps to keep in mind as you plan interactive oral reading lessons:

- Identifying words that need to be taught;

- Defining these words in a child-friendly way;

- Contextualizing words into varied meaningful formats;

- Reviewing words to ensure sustainability over time; and

- Monitoring children’s progress and reteaching if necessary.

Research-Based Interactive Oral Reading Programs

A number of interactive oral reading programs have been developed and tested. One of the earliest was Dialogic Reading (Whitehurst et al., 1988; Whitehurst et al., 1994; Zevenbergen & Whitehurst, 2003). This is a one-to-one picture-book interactive oral reading technique designed for preschoolers. It can be used by teachers, teacher aides, other caregivers, and parents to foster vocabulary development and language development more generally. There are two video tapes designed to train parents and teachers to use Dialogic Reading (Read Together, Talk Together Parent Video, 2002; Read Together, Talk Together Teacher Training Video, 2002). Another and much different interactive oral reading program, Text Talk, was developed by Beck and McKeown (2001, 2007) and is available as a commercial program (Beck & McKeown, 2005). The program is particularly strong in providing robust and interesting instruction. It differs from other interactive oral reading programs in that it teaches more sophisticated words and it teaches fewer words, only about 100 each year. Two other programs—one I have named Words in Context (Biemiller, 2001, 2009; Biemiller & Boote, 2006) and the other titled The First 4,000 Words (Fehr et al., 2011; Graves, Sales, & Davison, 2009; Graves et al., 2008; Sales & Graves, 2009b)—are described just below.

Words in Context. Words in Context (Biemiller, 2001, 2009; Biemiller & Boote, 2006) is an interactive oral reading technique intended for kindergarten through 2nd-grade children. The procedure includes some very direct instruction, more direct than that provided in some of the other approaches. Also, Words in Context differs from some of the other programs in that vocabulary development is the sole concern. The procedure is directly motivated by the fact that the vocabularies of disadvantaged children lag well behind those of their more advantaged peers and that the instruction needed to make up that gap needs to be “early, direct, and sequential” (Biemiller, 2001).

The first step in using Words in Context is to select books. The program uses one book per week, and in order to teach the number of words necessary to markedly increase disadvantaged students’ vocabularies, the program should be used for at least 1 year and preferably for 3 years. About 30 books are needed for each year. As it has usually been implemented, the approach uses narratives, but informational books could certainly be used as well and doing so would be consistent with the Common Core goals. Typical of books appropriate for kindergarten are Norman Birdwell’s Clifford at the Circus and Phoebe Gillman’s Jillian Jiggs. Typical of those appropriate for grade 1 are Alice Schertle’s Down the Road and Dayal Khalsa’s Julian. And typical of those appropriate for grade 2 are Leo Lionni’s Alexander and the Wind-up Mouse, and Stephanie McLellan’s The Chicken Cat.

The next step is selecting words. Unfortunately, as with Text Talk and Dialogic Reading, with Words in Context selecting words “remains an art, not a science” (Biemiller & Boote, 2006). Words are selected based on the teacher’s intuition that they (1) are known by some but not all children at the grade level at which you are working and (2) are not rare or obscure words and thus are likely to be useful to children as they progress into the upper elementary grades. Some samples of words that have been used with the procedure and the percentages of students Biemiller and Boote (2006) reported as knowing the words prior to instruction are shown in Figure 4.2.

Two important characteristics of these words should be noted. First, they are not rare and obscure words. They are words that children are likely to hear or use themselves in speaking, and they are words that they are likely to find in the books they read in the elementary years. Second, they span a range of difficulty. Since Words in Context is a whole-class approach, the goal is to include some words that will be a challenge for most of the children and some that will be a challenge for only some children.

Select about 24 words from each book. Students will not remember all the words that are taught, but Biemiller (2009) estimates that if this number of words were taught each week over a school year, children might learn 400 words. While such learning will not result in children with the smallest vocabularies catching up with those with larger vocabularies, it is a significant improvement over what they would know without instruction.

Figure 4.2. Sample of Words Used with the Words in Context Program and Percentages of Students Knowing Them

The third step is to implement the procedure over 5 days, as shown below.

Teaching Procedure for Words in Context

- Day 1. Read the book through once, including some comprehension questions after reading it but not interrupting the reading with vocabulary instruction. (Experience has shown that children may object to interrupting the first reading of the book with vocabulary instruction.)

- Day 2. Reread the book, teaching about eight words. When you come to a sentence containing a target word, stop and reread the sentence.

After rereading the word, give a brief, student-friendly definition. For example, after reading the sentence “It seemed like a good solution” in a 2nd-grade book, pose the question, “What does solution mean?” Then, answer your question with something like, “A solution is the answer to a problem.” Remember to keep the definitions simple, direct, and focused on the meaning of the word as it was used in the story.

At the end of the day’s instruction, review the words taught by rereading the sentence in which they appeared and the definition you gave. - Days 3 and 4. Reread the story two more times, teaching about eight new words each time. As on Day 2, briefly define the words as you come to them and review all of them at the end of the reading.

- Day 5. Review all of the words taught during the 5-day period, this time using a new context sentence to provide some variety but giving the same definition.

Used in this way, the procedure will require about half an hour a day, and will result in students learning a significant number of words over the course of a year. Of course, if the procedure is used from kindergarten through 2nd grade—and this is Biemiller’s goal and what really needs to happen if children with smaller vocabularies are to catch up with their peers—an even more significant number of words will be learned.

The First 4,000 Words

The First 4,000 Words (Fehr et al., 2011; Graves et al., 2009; Graves et al., 2008; Sales & Graves, 2009b) is an individualized, web-based program for ensuring that children in 1st–4th grades with very small oral vocabularies learn the approximately 4,000 most frequent English words. Thus, unlike other programs, it focuses on a specific, empirically identified set of words. Results of a preliminary study that taught 100 words indicated that students in the web-based treatment condition significantly (p < .01) outperformed students in the control condition with an effect size of 1.1 (Fehr et al., 2011). Results of a second study in which students completed as much of the entire program as they could in approximately 2 months indicated that students who studied a word missed on the pretest were 1.6 times more likely to answer it correctly on the posttest if they encountered it in the online lesson than if they did not (Davison, 2011).

The program is based on the fact that the English language includes a relatively small number of frequent words, which together make up the vast majority of running words in anything children read (Hiebert, 2005, 2014). For example, the first 100 words account for about 50% of the words students will encounter, the first 1,000 words about 70%, and the first 5,000 words 80–90%. Just how important it is to know these words is shown in Figure 4.3, which shows an intermediate-grade text and how much of it children could read if they knew the 500; 1,000; 2,000; or 4,000 most frequent English words.

As can be seen, even with a vocabulary of only 500 words, a student could read a lot of the words in this text. However, he would not be able to read nearly enough words to comprehend it. Once a student has acquired a vocabulary of about 4,000 words—with the help of the teacher and some use context—he can begin to comprehend texts of this sort. The First 4,000 Words program helps students build the basic oral vocabulary they need to support a basic reading vocabulary.

The specific words used in The First 4,000 Words program are a set of approximately 3,600 words taken from The Educator’s Word Frequency Guide (Zeno, Ivens, Millard, & Duvvuri, 1995), the most recent large-scale frequency count of American English, and modified from work conducted by Hiebert (2005). The complete word list is available at www.thefirst4000words.com.

This is how the program works:

- Students are pretested in intact classrooms with a paper-and-pencil test to see which students qualify for the program. Even in classrooms with substantial numbers of children living in poverty and English learners, many of the students will already know these words, and only a half a dozen or students are likely to quality for the program. But for students who do qualify for the program, learning these words is absolutely crucial.

- Based on their pretest results, qualified students are placed in the program at the level at which they know about 80% of the words.

- Each student moves through the program at his own pace, and can move up or back depending on his performance on online tests on each of 360 units, each of which deals with 10 words.

Figure 4.3. Intermediate-Grade Passage Showing What Students Could Read If They Knew the 500; 1,000; 2,000; or 4,000 Most Frequent English Words

Panel 1: Knowing only the 500 most frequent words, a student could read only the words shown here:

Could it be an _______? The year before, _______ had seen one for the first time when his mother took him to a _______ _______ in _______, _______ _______. He had _______, _______, as the _______ a _______ by _______ on the _______ of a_______ that was _______ on the _______. Now _______ an _______ was right here in _______, and about to _______ over his house. Not _______ to _______ a thing,_______ the _______ and _______ up the _______ of the house to its _______. From there he had a good _______ of the _______, _______ the _______ place. And in the_______, _______ ever_______, he saw the _______.

Panel 2: Knowing the 1,000 most frequent words, a student could read the words shown in this version:

Could it be an _______? The year before, _______ had seen one for the first time when his mother took him to a _______ in _______, _______. He had watched,_______, as the _______ gave a _______ by _______ on the _______ of a _______ that was _______ on the ground. Now maybe an _______ was right here in_______, and about to _______ over his house. Not _______ to _______ a thing,_______ opened the window and _______ up the _______ of the house to its_______. From there he had a good view of the _______ River, _______ past the_______ place. And in the sky, coming ever _______, he saw the _______.

Panel 3: Knowing the 2,000 most frequent words, a student could read the words shown in this version:

Could it be an airplane? The year before, Charles had seen one for the first time when his mother took him to a flying _______ in _______, Virginia. He had watched, _______, as the _______ gave a _______ by _______ oranges on the_______ of a _______ that was _______ on the ground. Now maybe an airplane was right here in _______, and about to fly over his house. Not _______ to _______a thing, Charles opened the window and climbed up the _______ roof of the house to its _______. From there he had a good view of the _______ River, _______ past the_______ place. And in the sky, coming ever closer, he saw the plane.

Panel 4: Knowing the 4,000 words, a student would be able to read all the words in the version below except those that are underscored:

Could it be an airplane? The year before, Charles had seen one for the first time when his mother took him to a flying exhibition in Fort Myer, Virginia. He had watched, enthralled, as the pilot gave a bombing demonstration by dropping oranges on the outline of a battleship that was traced on the ground. Now maybe an airplane was right here in Minnesota, and about to fly over his house. Not wanting to miss a thing, Charles opened the window and climbed up the sloping roof of the house to its peak. From there he had a good view of the Mississippi River, flowing languidly past the Lindbergh place. And in the sky, coming ever closer, he saw the plane.

Source: Giblin, 1997, p. 3.

- In each unit, a student is taught only those of the 10 words that an online pretest indicates he does not know.

- Following the pretest, the student participates in three shared reading experiences. In Shared Reading 1, the passage is visible to the student with the missed words highlighted, and it is read to the student without interruption. In Shared Reading 2, the student has a variety of options for interactive work with the words he missed. In Shared Reading 3, the student listens to the story again and has four options: listen to a sentence again, listen to the definition of a word, hear the passage again, or move on.

- The shared reading experiences are followed by two games centering on the words missed and a unit posttest that is identical to the unit pretest. If a student does well on the posttest, he moves on to the next 10-word unit. If he does not do well, he participates in a remediation activity.

The four panels in Figure 4.4 show grayscale versions of various aspects of the program.

Panel One shows The Treehouse Studio. Again, this is where the student is pretested on the 10 words from each unit. In this example, the student hears the word clock and presses the picture of the clock to show his understanding.

Panel Two shows The Cozy Cave, the setting where the shared reading is done.

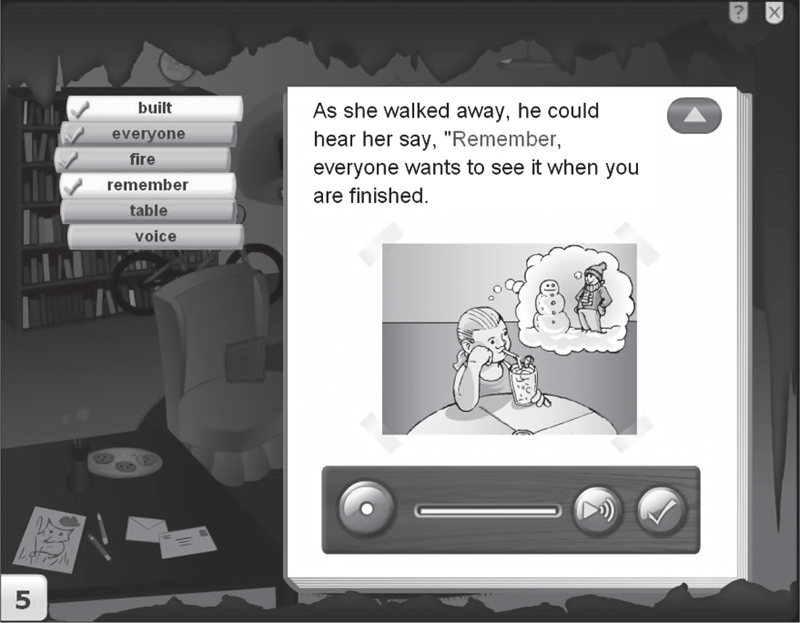

Panel Three shows the second of the three shared-reading sessions. The student missed six words on the unit pretested—built, everyone, fire, remember, table, and voice—and thus concentrates on them. In this example, the student clicked on remember, and the sentence you see appeared on the screen and was read aloud to him. The student then has the options of clicking on the button at the bottom left and saying the word, clicking on the speaker button and hearing what he said, and clicking on the check button to see if he got it correct. Work with the other words is similar.

Figure 4.4. Some Screenshots from The First 4,000 Words Program

Panel One.

The Treehouse Studio

Panel Two.

The Cozy Cave

Panel Three.

A Shared-Reading Lesson

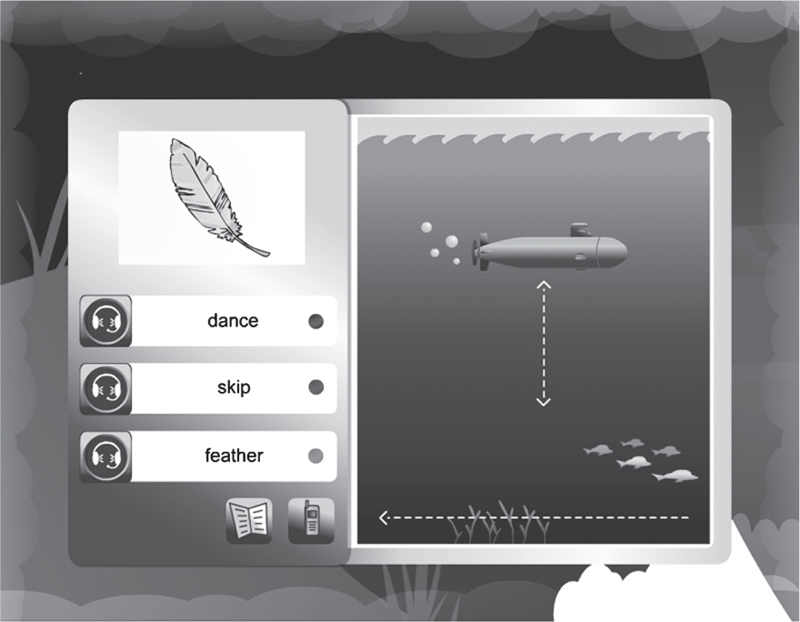

Panel Four.

A Word Game

Finally, Panel Four shows a typical game following the three shared readings. Clicking on the correct word, in this case feather, makes the submarine go faster and deeper, earning points that show up on a counter. It the student wants to hear a word, he clicks on the microphone button to the left of that word. If he wants a hint, he clicks on either of the help buttons at the bottom.

While assisting students in incorporating the 4,000 most frequent words is going to take a considerable period of time—months and years, not days and weeks—doing so is well worth the time spent. Without these words, there are few texts a student can read; with these words, the world of reading opens up to him. Of course, most children will not start at the beginning of the list; even children with small vocabularies may know many of the most frequent words and begin at some point well into the list.

MindPlay, www.mindplay.com, is currently developing a commercial version of The First 4,000 Words, and a modified version of the program that employs tutors instead of using web-based instruction has recently been developed (PRESS Research Group, 2015).

WORD-CONSCIOUSNESS ACTIVITIES FOR THE PRIMARY GRADES

Given the smaller vocabularies that many children living in poverty and many English learners bring to school, direct attempts to build their vocabularies with procedures like Dialogic Reading, Text Talk, Words in Context, and The First 4,000 Words make good sense. At the same time, it is important to recognize that such approaches can do only some of the work necessary to narrow the vocabulary gap. Other activities—activities that permeate the school day and school year, extend into students’ lives outside of school, and get students interested in words and excited about them—are an absolute necessity. The goal of such activities is to make students consciously aware of the words they and others encounter and use, really value words, and want to learn and use more of them. In Chapter 7, “Promoting Word Consciousness,” I describe word-consciousness activities for all grade levels. Here, I give two examples of word-consciousness activities particularly appropriate for primary-grade children as a reminder of the absolute necessity of such activities for primary-grade children with small vocabularies.

The first activity was developed by Blachowicz and Obrochta (2005) and is termed Vocabulary Visits. Vocabulary Visits focuses on content-area vocabulary. It provides in-depth study of a group of words, and at the same time makes vocabulary learning fun and gets students interested and excited about words. The procedure is modeled after field trips that students greatly enjoy and learn from. As is the case with well-run field trips, Vocabulary Visits (1) prepares students for the journey; (2) encourages use of various senses; (3) provides mediation and assistance by an adult; (4) involves exploration, talk, reading, and writing; and (5) includes follow-up activities. Doing all this might take several weeks. Here is how the procedure unfolds:

- Identify a central topic, a brief informational book on the topic, and a brief video related to the topic. Topics abound: Skeletons, recycling, Colonial America, healthy foods, and how animals help people are just a few of the myriad possibilities. Select the core vocabulary that you want to emphasize. Choose a photo likely to stimulate discussion on the topic, and make it the focal point of a large poster prominently displayed in the classroom.

- Introduce the topic and ask students to talk briefly about some things they know about the topic. Have each student generate a list of words related to the topic and collect the lists. Then, put the words students generated on the poster.

- Preteach key vocabulary related to the video and reading selection.

- Show the video. Ask students for words describing what they see, hear, and feel. Add these words to the poster with post-its, and group related words.

- Read a passage in the book aloud using interactive reading techniques. Have students give “thumbs up” when they hear one of the words. (This seemingly tangential activity is an important part of the procedure, since it keeps students involved and focused on the key words.) Add some key words to the poster if students don’t supply them.

- Read the remaining passages, again having students give thumbs up when they hear one of the words, and again adding key words if students don’t supply them. Reorganize the words as seems appropriate.

- Do extension activities such as word games, sorting, writing, and reading new topically related books.

- Evaluate students’ learning by having them again generate a list of words related to the topic, and comparing their initial lists with their final ones. As a less direct form of evaluation, you can also have students summarize their favorite of the books or create their own book on the topic.

Figure 4.5. Some Core Words (in Roman) and Student-Supplied Words (in Italics) for a Vocabulary Visits Session on Skeletons

Figure 4.5 shows some core words and some words students supplied for a Vocabulary Visits session on skeletons.

The second activity, a particular version of the widely used word-of-the-day approach, was developed by Katch (2004), who teaches 4-, 5-, and 6-year-olds. Here is how it unfolds:

Shortly before beginning the activity, establish the concept of “special words,” words for things that children love, would really like to have, or perhaps even fear: Christmas, kitty, daddy, and ghost are examples. Also before beginning the activity, put each child’s name on a card and tack the cards on a corkboard so that each child has a column for his words.

Each day, have one child bring in his special word, put it in his column on the corkboard, read it, talk about what makes it special, and read each of the special words that other children have brought in. After one row is completed, children start a second row, again reading both the words they contribute and other children’s words until there are too many words to read every day. At that point, the child who brings in a word for the day reads all of his words but only one of the rows of words. As the school year progresses, make it a point to highlight individual words over time, perhaps mentioning whose word it is and its special meaning or perhaps using the word to review some aspect of letter-sound correspondences. Part of the goal is to feature and celebrate these special words, “The Most Important Words” as they are referred to in the title of Katch’s article. More generally, however, the goal is to highlight, celebrate, and kindle children’s interest in words generally.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Providing rich and varied language experiences—experiences in reading, writing, listening, and discussing—is vitally important. This is something we need to do for all students at all age and grade levels and all levels of proficiency. Students can only develop rich and powerful vocabularies if they engage in many and varied activities that invite, motivate, and prompt them to learn and use sophisticated and appropriate words. Providing special help for primary-grade children who enter school with relatively small vocabularies—including English learners with small English vocabularies—is also vitally important. Interactive oral reading activities such as Dialogic Reading, Text Talk, Words in Context, and The First 4,000 Words are the most thoroughly researched and theoretically sound ways of doing that. Adding a focus on word consciousness for primary-grade children to these more formal approaches will further promote vocabulary growth, as well as make the classroom a more lively and interesting place for children and teachers alike. Together, these approaches will go a long way toward enriching the vocabularies of all children as they move toward the Common Core goal of being “college and career ready” when they complete their K–12 schooling.