CHAPTER 7

Promoting Word Consciousness

Word consciousness—and especially understanding the power of word choice—is essential for sustained vocabulary growth. Words are the currency of written language. Learning new words is an investment, and students will make the required investment to the extent that they believe that the investment is worthwhile.

—Judith Scott and William Nagy, Vocabulary Scholars

Words are indeed the “currency of written language,” as Scott and Nagy so nicely put it. Moreover, as Scott and Nagy also note, students are likely to make the required investment needed to learn vocabulary only if they believe that the investment is worthwhile. Thus, one of the major long-term goals of vocabulary instruction is to assist students to gain a deep appreciation of words and to value them, a goal that has been termed “word consciousness.” Simply stated, word consciousness refers to awareness of and interest in words and their meanings. As defined by Anderson and Nagy (1992), word consciousness involves both a cognitive and an affective stance toward words. Word consciousness integrates metacognition about words, motivation to learn words, and deep and lasting interest in words.

Students who are word conscious are aware of the words around them—those they read and hear and those they write and speak. This awareness involves an appreciation of the power of words, an understanding of why certain words are used instead of others, and a sense of the words that could be used in place of those selected by a writer or speaker. It also involves, as Scott and Nagy (2004) emphasize, recognition of the communicative power of words, of the differences between spoken and written language, and of the particular importance of word choice in written language. And it involves an interest in learning and using new words and becoming more skillful and precise in word usage.

The process of acquiring vocabulary is complex, and for many students acquiring the rich store of words that will help them succeed in and beyond school is a challenge. With tens of thousands of words to learn and with most of this word learning taking place incidentally as students are reading and listening, a positive disposition toward words is crucial to students’ success in expanding the breadth and depth of their word knowledge over the course of their lifetimes. Word consciousness exists at many levels of complexity and sophistication, and can and should be fostered among preschoolers as well as among students in and beyond high school. Fortunately, many word-consciousness activities are easy to implement and will not take much of your time or your students’ time.

Two factors, both of which I have already discussed, argue for the importance of word consciousness. First, there is the growing realization that for all learners—from primary-grade children to college students—motivation and affect are every bit as important to learning as cognition (see, Guthrie & McPeake, 2013; Moje & Speyer, 2014; National Research Council, 2004; Pressley et al., 2003; Stripek, 2002; Wigfield & Eccles, 2002; Wentzel & Wigfield, 2009). Word consciousness is the motivational and affective component of the multifaceted vocabulary program described in this book. Second, there is the increasing evidence that lack of vocabulary is a key factor underlying school failure for disadvantaged students (Becker, 1977; Biemiller, 2004; Chall et al., 1990; Fernald et al., 2013; Hart & Risley, 1995; White et al., 1990), and represents a significant challenge for many English learners (August et al., 2005), particularly with the advent of the Common Core (Coleman & Goldenberg, 2012). Kindling students’ interest and engagement with words is a vital part of helping all students, but particularly less advantaged students, develop rich and powerful vocabularies. The National Research Council (2004) sums up the cost of disengagement for less advantaged students particularly well: “When students from advantaged backgrounds become disengaged, they may learn less than they could, but they usually get by or they get second chances; most eventually graduate and move on to other opportunities. In contrast, when students from disadvantaged … backgrounds become disengaged, they … face severely limited opportunities” (p. 1).

In the remainder of this chapter, I discuss a number of specific approaches to fostering word consciousness in all students and in a variety of contexts—in reading, in writing, and in discussion. They include Modeling, Recognizing, and Encouraging Adept Diction; Promoting Wordplay; Providing Intensive and Expressive Instruction; Involving Students in Original Investigations; and Teaching Students About Words (Graves & Watts-Taffe, 2008). In general, the approaches are arranged from those that are less informal and less time consuming to those that are more formal, more time consuming, and more demanding on the learner, although this is not a hard-and-fast progression. Finally, in the last section of the chapter, I describe an instructional activity that is intended primarily to teach individual words but is also an excellent vehicle for fostering word consciousness.

MODELING, RECOGNIZING, AND ENCOURAGING ADEPT DICTION

Modeling adept diction, recognizing skillful diction in the texts students are reading, and constantly encouraging students to employ adept diction in their own speech and writing are starting points in building word consciousness. As with teaching in general, modeling is critical. Specifically, it is vital to model both enthusiasm for and proficiency in adept word usage.

Consider the difference between asking a student to close the door because it is not quite closed and asking her to close the door because it is ajar, the difference between describing the color in a student’s painting as greenish-yellow as opposed to chartreuse, or the difference between describing Russell Wilson as an excellent athlete or a consummate athlete. When students hear unfamiliar words used to describe concepts they are familiar with and care about, they become curious about the world of words. In addition, they learn from experience that word-choice possibilities are immense and varied. As their “word worlds” open up, so too do the wider worlds in which they live.

Another opportunity to model, recognize, and encourage adept diction is to use the tried-and-true word-of-the-day approach. Allocating time each day to examine a new word can be effective with students of all ages. The word can be teacher selected or student selected, and might be chosen from books, magazine articles, or newspapers, or from heard contexts such as television programs, discussions, and other teachers. It often works well to begin with teacher-selected words and to present each word and its meaning, including both definitional and contextual information, an explanation of why it was selected, and examples of how it relates to the lives of one or more members of the class. When appropriate, adding relevant pictures, gestures, concrete objects, and drama increase students’ enthusiasm and understanding. Further, a period for student questions and comments allows for the type of deep processing necessary for effective word learning (Stahl, 1998).

Scott et al. (1996) have studied vocabulary as a vehicle for connecting reading and writing. Within the context of literature discussion groups, they assign one student the role of word hunter, whose job it is to look for particularly interesting uses of language in the literature read by the group. This student might, for example, draw the group’s attention to Sharon Creech’s use of the word lunatic in Walk Two Moons (1994) to describe a mysterious stranger. Why doesn’t the author use mentally ill or weirdo? How does the author’s word choice relate to the character who first uses the word to describe the mysterious fellow? Such discussions can lead students to more thoughtful word choices in their own writing.

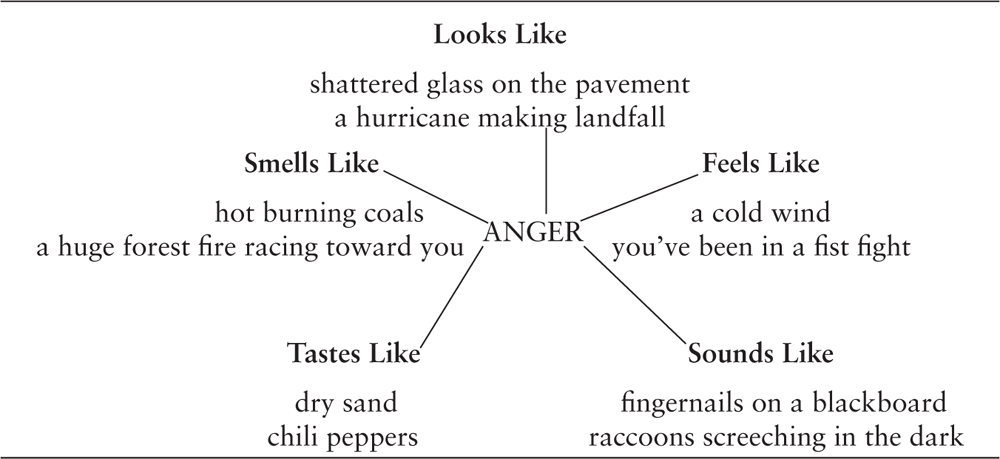

Figure 7.1. Sensory Web for Anger

Another way to encourage adept diction in students’ writing and speaking is to scaffold their use of new words. They might construct sensory webs for words likely to be useful in their writing or for words they have read and would like to understand more fully. In such webs, the lines leading outward from the word itself provide places for students to fill in what the word smells like, tastes like, looks like, sounds like, and feels like. Scott and her colleagues (1996), for example, report that one of the 6th graders they worked with wrote that anger smells like “hot burning coals,” looks like “shattered glass on the pavement,” tastes like “dry sand burning in the desert,” sounds like “fingernails screeching on the blackboard,” and feels like “a cold wind gripping you all over.” Figure 7.1 shows this student’s responses along some additional ones.

A related technique used by Scott and her colleagues to help students expand the word choices used in their writing is to have students brainstorm words related to a key word. For the word anxious, one student came up with the related words shaky, fidgeting, worried, apprehensive, nervous, and impatient.

In an extension of the 1996 work, Scott et al. (2012) developed a word-consciousness program for upper-elementary students in classes with large numbers of English learners. One of the main goals of this project was to increase the word consciousness of teachers. This, I believe, is terribly important because unless teachers themselves become more word conscious their students are certainly not likely to become so. Teachers in the project examined word-learning theories, read a variety of rich literature, engaged in wordplay and games, and looked for opportunities to promote vocabulary learning across the curriculum. As a result, teachers became more aware of words, began to reflect on their own knowledge and use of words, and began to connect their own processes of learning to how their students were learning.

PROMOTING WORDPLAY

Children learn at a very young age that printed words convey meaning. But words do much more than convey meaning. Words and phrases can simultaneously feel good on the tongue, sound good to the ear, and incite a riot of laughter in the belly. Verbal phenomena such as homophones and homographs; idioms, clichés, and puns; and onomastics (the story of names) offer myriad opportunities for investigating language. And wordplay books and other interesting books about words are available for children of all ages, as well as for adults. Students of all ages get real pleasure out of words that sound alike, words that look alike, and words that look nothing like what they mean.

Moreover, it needs to be emphasized that wordplay is not a frill. As Blachowicz and Fisher (2012) explain, it is an activity firmly grounded in sound pedagogy and in research:

- Wordplay is an important component of the word-rich classroom.

- Wordplay calls on students to reflect metacognitively on words, word parts, and context.

- Wordplay requires students to be active learners and capitalizes on possibilities for the social construction of meaning.

- Wordplay develops domains of word meaning and relatedness as it engages students in practice and rehearsal of words. (p. 190)

Homophones and Homographs

Homophones present many opportunities for enjoyment and learning. Children delight in images such as those of a “towed toad,” a “sail sale,” or a “Sunday sundae.” One activity that many children enjoy is drawing such homophone pairs, and one approach that has proven useful is to have students fold a piece of drawing paper into quadrants so they can write homophone pairs in the boxes on the left side of the paper and draw corresponding pictures in the boxes on the right side of the paper. Games such as Homophone Bingo and Homophone Concentration offer additional possibilities for experimenting with homophones.

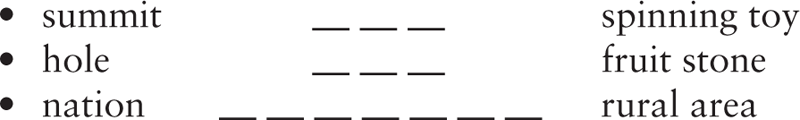

Some words, of course, not only sound alike, but are spelled alike—and still have more than one meaning. In fact, a large proportion of English words have more than one meaning. These homographs allow for a variety of games, including the following one, taken from Richard Lederer’s Get Thee to a Punnery (1988), a wordplay book for adults. In each of the lines below, students insert a word that means the same as the word or phrase at either end; the number of blanks indicates the number of letters in the missing word.

Having students complete such puzzles can be fun and entertaining, but having them create such items can be even more valuable. As with many wordplay activities, making up items of this sort is well within the reach of many children, and provides an active, creative, and rewarding learning experience.

Idioms, Clichés, and Puns

Children are often fascinated by idioms such as “A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush” and “Don’t count your chickens until they’re hatched.” Representing as they do the language of particular groups, idioms reflect particular periods of time, particular regions of the country, and particular cultures. Children can enjoy drawing or dramatizing the literal meanings of idioms such as “Don’t look a gift horse in the mouth,” “Roll with the punches,” and “food for thought,” and contrasting them with their figurative meanings. On a different note, remember that idioms can present a particular problem to English learners. As I will again discuss in Chapter 8, because the literal meanings of the words don’t apply, students just learning English may find them incomprehensible and thus confusing. It is important, then, to be on the lookout for potentially troublesome idioms and clarify their meaning for ELs. The Longman American Idioms Dictionary (Urban, 2000) provides a listing of over 4,000 of them.

Clichés are often thought of as being unimaginative and trite. But in fact they are examples of language use that has endured over time, expressing familiar sentiments and wisdom that are timeless. They are at once phrases that many are familiar with and expressions of shared human experience, making them accessible and important forms of language for students to experience. Teachers can kindle students’ word awareness by being “down to earth” with them, warning them about “jumping out of the frying pan into the fire,” and repeatedly playing around with phrases such as “until the cows come home.”

Like clichés, puns are memorable and often quite clever. Advertisers often use them in songs and jingles, noted authors make use of them, and newspapers frequently employ them in headlines. In Romeo and Juliet, for example, the dying Mercutio can’t resist a pun as he exclaims, “Look for me tomorrow, and you will find me a grave man.” The day after the Minnesota Vikings’ kicker muffed a short field goal that led to the team’s ouster from the playoffs, the Minneapolis Star-Tribune ran the headline “Kicked Out!” And even the prestigious New York Times employs them from time to time, as seen in this line, “Balloons have become a high flying business and sell at inflated prices.”

Onomastics

Onomastics, the study of names, is yet another form of wordplay, one that Johnson, Johnson, and Schlicting (2004) have examined in some depth. Words derive their names from various sources, and you can expand students’ knowledge of these sources in two ways. First, you can occasionally mention the derivation of a name as part of the overall attempt to raise students’ word consciousness. Second, you can explain one or more of the various sources of words and let students search for words derived in those ways. For example, some words, which Johnson and his colleagues term eponyms, are named after people. The sequoia redwood is named after Chief Sequoya (1770?–1843), the Geiger counter after Hans Geiger (1882–1945), and beef Wellington after the first Duke of Wellington (1759–1852). Students can look up these historical figures and learn just what they did to warrant their names becoming a permanent part of our language. Alternatively, you might give students names that are derived from people and ask students to trace the story behind them. Some examples Johnson and his colleagues suggest are cobb salad, maverick, frisbee, and Tony Award.

As another example, some names, which Johnson and his colleagues (2004) term aptronyms, are particularly appropriate for a person’s profession. Johnson and his colleagues located a Doctor Smart, who is a professor; a family named Woods, who own a lumberyard; and a Ms. Carb, who manages a bakery; and my wife once had a surgeon named Les Sharp. Students might enjoy making up aptronyms for people in various professions, for example, Ruth Decay or Dennis Drill for dentists. These are just two of a number of forms of onomastics Johnson and his colleagues discuss, along with other sorts of wordplay including expressions, figures of speech, word associations, word formations, word manipulations, word games, and ambiguities. All are worth considering.

Wordplay Books

A wide array of books lend themselves to raising word consciousness and to learning a host of interesting facts about words. Books are available for every age and grade level, and they deal with many aspects of words. There are alphabet books, books that include extensive wordplay, books in which words play a central role, books about wordplay, books filled with word games, books about the history of words, books of proverbs, books about slang, and books about nearly any other aspects of words you could think of. The county library I use—which I would characterize as a medium-size library—lists over 741 entries under the term word books. A search on the Amazon website with the term word books yielded 12,743 items. Of course, a careful search of the library or Amazon results would reveal that not all of those books are the sort of books I’m describing here, but a lot of them are. My point is that there are far more word and wordplay books than I can possibly describe here. Consequently, I am listing a few books in each of several categories to suggest the range of books available, but I encourage you to check your local library, your local bookstore, and web sources such as Amazon for many more titles.

Two wonderful alphabet books are Judith Viorst’s The Alphabet from Z to A (With Much Confusion on the Way) (1994) and Michael Escoffier’s Take Away the A (2014). Each combines clever illustrations with inviting text and appeals to both young and highly sophisticated readers, and Escoffier’s book adds the imaginative insight that subtraction of a single letter from a word can sometimes form a very different word, as when “beast” becomes “best.” Oliver Jeffers’s Once Upon an Alphabet: Short Stories for All the Letters (2014) is a different sort of alphabet book, as it includes an intriguing and sometimes bizarre short story representing each letter.

Two books that highlight the richness of language are Fred Gwynne’s The King Who Rained (1970) and Louis Sachar’s Holes (1998), which won the 1999 Newbery Medal. The first revolves around words with multiple meanings, and the second is filled with interesting words, some of which provide clues to the central puzzle of the novel, and others of which, like “Stanley Yelnats,” the palindromic name of the protagonist, are simply fun.

Some books with plots centering around words are Andrew Clements’s Frindle (1998), Julia Cook’s My Mouth Is a Volcano (2008), and Nicki Grimes’s Words with Wings (2013). Clements’s novel tells the story of Nick, who invents the word frindle, convinces kids in his school to use it instead of the word pen, and watches as his word spreads to the city, the nation, the world, and even the dictionary. Cook’s book tells the story of Louis, who wants to get his words out so much that they wiggle, jingle, and erupt out of his mouth, interrupting others. And Grimes’s sensitive verse novella tells the story of Gabby, a daydreamer whose words fostered her creativity and allowed her to shine.

Two wordplay books are Richard Lederer’s Pun and Games (1996), intended for middle-grade students, and Get Thee to a Punnery (1988), intended for adults but also appropriate for high school students. Pun and Games includes, as recorded in the subtitle, “jokes, riddles, daffynitions, tairy fales, rhymes, and more wordplay for kids,” while Get Thee to a Punnery contains lots of puns but also some challenging word games. Additionally, Blachowicz and Fisher’s “Keep the ‘Fun’ in Fundamental” (2012) provides dozens of wordplay activities as well as sources for still more activities.

Finally, two books about words and language appropriate for teachers are Greenman’s Words That Make a Difference—and How to Use Them in a Masterly Way (2000), and Pinker’s The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language (2000). Almost all of Words That Make a Difference is exactly what a vocabulary book is not supposed to be—an alphabetical list of words and their definitions. But two things save it from being a bad book and make it a very good one. Accompanying each word and definition is a short passage from the New York Times in which a skilled writer used the word in a clever, memorable, and appropriate way. Additionally, the words are at just the right level of difficulty—ones that we have heard but don’t use because we are not quite sure of them—and many are appropriate for stretching high school students’ vocabularies. The Language Instinct, on the other hand, is very much what a book about language directed at a general audience ought to be. In it, Pinker, an eminent MIT linguist, gives his theories about the nature, origin, and development of language. Although not all agree with Pinker, the book is definitely interesting, exciting, accessible, and filled with ideas to share with students. Publishers Weekly called it “a beautiful hymn to the infinite creative potential of language.”

PROVIDING RICH AND EXPRESSIVE INSTRUCTION

In keeping with the plan for this chapter to present less formal and less time-consuming activities earlier, the first activity described in this section—Scott and her colleagues’s Gift of Words technique (Scott & Nagy 2004) for encouraging students to incorporate more interesting and sophisticated vocabulary into their writing—is the least formal and least time-consuming activity. The next two activities—Beck and McKeown’s Rich Instruction and Duin’s Expressive Instruction (Beck, Perfetti, & McKeown, 1982; Duin & Graves, 1987, 1988 McKeown & Beck, 2004;)—are more deliberately structured and more time consuming.

The basic logic underlying Scott’s program is this: Reading and writing are reciprocal processes. Significant word learning—and, I would say, the opportunity to develop word consciousness—requires children to be immersed in situations in which rich, precise, interesting, and inventive use of words is valued. Employing quality children’s literature that contains rich, precise, interesting, and inventive use of words; encouraging students to identify these apt and creative uses of language; honoring these words and phrases by posting them prominently around the room; and frequently calling students’ attention to them creates such an environment. Thus, Scott immerses students in good children’s literature, encourages them to select words and phrases they value, and has them post these words and phrases in the classroom. She then encourages students to “borrow” the words and phrases they have identified in their reading and use the words in their writing. Next, she designs writing activities that encourage use of rich and varied vocabulary, and suggests students “catch” the words and phrases on the board, modify them to fit the subjects they’re writing about, and use these modifications of professional writers’ phrasing in their own writing.

One of the books the children read, enjoyed, and found many interesting words and phrases in was Natalie Babbitt’s Tuck Everlasting (2009). A number of words and phrases from Tuck were copied and posted abound the classroom, and a number of students were able to incorporate these in their writing. For example, one of the phrases from Tuck that a student decided to use was “a great potato of a woman.” In the student’s writing, this phrase became “a long string bean of a man,” an interesting transformation and a very vivid image.

Another and more elaborate borrowing came from the following paragraph of Babbitt’s novel:

“So,” said Tuck to himself. “Two years. She’s been gone two years.” He stood up and looked around, embarrassed, trying to clear the lump from his throat. But there was no one to see him. The cemetery was very quiet. In the branches of the willow behind him, a red-winged blackbird chirped. Tuck wiped his eyes hastily. Then he straightened his jacket again and drew up his hand in a brief salute. “Good girl,” he said aloud. And then he turned and left the cemetery, walking slowly. (p. 138)

Recast by a student, the prose was transformed into this poem:

In Loving Memory

Winifred Foster

Jackson

Dear Wife

Dear Mother

1870–1948

“So,” said Tuck to himself

gone two years

Embarrassed

clear the lump from his throat

Quiet cemetery

Black bird chirped

Wiped his eyes

“Good girl,” he said out loud

Quickly departed

Sadness filled the air.

—Kirn (Scott et al., 1994, p. 43)

We think it is especially noteworthy that in activities such as these students are both learning something about vocabulary and learning something about, and perhaps coming to appreciate, the author’s craft.

I described how Beck and McKeown’s Rich Instruction and Duin’s Expressive Instruction can be used to teach individual words in Chapter 5. Here, I describe how they can be used for fostering word consciousness. Since the two include similar activities, I describe them together. The first step is to select a small set of words that are semantically related. One set used by Beck and McKeown—rival, hermit, novice, virtuoso, accomplice, miser, tyrant, and philanthropist—contains words that refer to people. A set used by Duin—advocate, capability, tether, criteria, module, envision, configuration, and quest—contains words that can be used in talking about space exploration.

The next step, the central part of the instruction, is to have students work extensively and intensively with the words, spending perhaps half an hour a day over a period of a week or so with them, and engaging in a dozen or so diverse activities with them—really getting to know them, discovering their shades of meaning and the various ways in which they can be used, and realizing what interesting companions words can be. Beck and McKeown’s activities, for example, included asking students to respond to words like virtuoso and miser with thumbs up or thumbs down to signify approval or disapproval; asking which of three actions an accomplice would be most likely to engage in—robbing a bank alone, stealing some candy, or driving a getaway car; and asked such questions as “Could a virtuoso be a rival? Could a virtuoso be a novice? and Could a philanthropist be a miser?” Duin’s activities included asking students to discuss how feasible space travel might soon be, asking them how a space station could accommodate handicapped persons, and asking them to write brief essays called “Space Shorts” in which they used the words in dealing with such topics as the foods that might be available in space.

The third step, which was used only in Duin’s Expressive Instruction, is to have students write more extensive essays using as many of the taught words as possible, playing with them and exploring their possibilities. Duin’s students appeared to really enjoy this activity. As their teacher observed, “Students who were asked to write often and use the words in written class work showed great involvement in their writing.” The students also showed that they could indeed use the new words. One student, for example, noted that “the space program would be more feasible if we sent more than just astronauts and satellites into space,” and then suggested that designers should “change the whole configuration of the space shuttle so that it could accommodate more people.”

Finally, I would add a fourth step—that of directly discussing with students the word choices they make, why they make those choices, and how adroit use of words makes our speech and writing more precise, more memorable, and more interesting. Note that when either Rich Instruction or Expressive Instruction is used for the purpose of fostering word consciousness, the main goal is to get students involved with and excited about words. Using these clever and intriguing approaches several times a year would be a substantial contribution to reaching this goal.

INVOLVING STUDENTS IN ORIGINAL INVESTIGATIONS

The activities described in the previous sections call students’ attention to words in various ways—some of which are more deliberate than others. This section addresses the role of still more systematic efforts—research conducted by students themselves—in the development of word consciousness. Such original investigations centered on vocabulary provide a wealth of opportunities for increasing word consciousness. An array of options for investigations exist, some centered on text, some on speech, and some on interviews of language users.

Investigations focusing on written text are particularly doable because the data sources are readily available. One option, appropriate for secondary students, is to investigate the vocabulary used in various texts. For example, students might compare the typical number of words in articles in USA Today and the New York Times. As part of such a study, they could use some metric of word difficulty to examine the differential difficulty of the vocabulary in the two papers, perhaps tallying words beyond the first 10,000 most frequent in The Educator’s Word Frequency Guide (Zeno, Ivens, Millard, & Duvvuri, 1995). Such a study could lead to fruitful discussions of why those differences exist, as well as a discussion of the reading process and text features associated with lower and higher levels of text difficulty.

Investigations of spoken language are somewhat more difficult because the language must be recorded before it can be analyzed. One source of spoken language that is readily accessible is television. Middle-grade students might enjoy analyzing the vocabulary used in cartoons, looking perhaps for colorful adjectives used by the characters. Similarly, secondary students might enjoy comparing the terminology used in police dramas, medical series, news broadcasts, and other types of programs. More demanding tasks might involve recording language use in natural settings. I can still remember a really interesting study of the speech of short-order cooks done by a University of Minnesota student 20 years ago. In a similar vein, students could work in small groups to study vocabulary use within particular contexts such as the school cafeteria, the gym during basketball practice, or places where they work. Students with very young siblings might record 10 minutes or so of talk a week over a period of a month and draw some conclusions about the contents of their younger siblings’ vocabularies and any changes in that content over time.

Attitudes toward words and phrases or usages of different groups offer still other possibilities. Students could compile a list of currently used “hip” words from their peers, compile a list of past hip words from their parents or other adults, and interview representatives of both groups on their reactions to the words. Greenman (2000), for example, has listed a number of now-dated hip expressions that make me cringe just hearing them but that I am quite sure I used rather extensively and proudly as a youngster. Students might take such a list and interview their parents and other adults to see if they used them in the past, if they now use them, and what their present response to them is. Students could ask similar questions of their peers.

Alternatively, or in addition, students could collect contemporary terms from their peers, and ask their parents and other adults if they know their meanings and how they react to them. It would be interesting to compare not only the actual words used to represent various concepts but also the concepts the words represent. Which new words represent the same concepts that were important to teenagers 25 or 30 years ago? Which words represent concepts that are important to teenagers today but were less important, or even unheard of, 25 or 30 years ago? Comparing a dictionary published 40 years ago with one published more recently is another way to study changes in words and concepts.

Another possibility, this one particularly appropriate for Internet users, is for students to investigate usage variation across geographic areas. Minnesotans, for example, use rubber binders to hold things together. Is their use restricted to Minnesota? Wisconsin students look for a bubbler if they’re thirsty. What do Californians, New Yorkers, or Floridians drink from? Email offers a convenient way to ask these and other questions about geographical differences in word usage.

Still another possibility is to engage students in “explorations” such as those suggested by Andrews in Language Exploration and Awareness: A Resource Book for Teachers (2006). In the following investigation, a modified version of one Andrews presents, junior or senior high students explore the language of uniforms:

Directions for Exploring the Language of Uniforms: Prepare a poster of photographs and drawings of people dressed in formal and informal uniforms. Then lead a class discussion using the following prompts:

- Give some examples of formal and informal uniforms.

- Why do people wear uniforms?

- What happens when a person is “out of uniform” when he or she is expected to be wearing one?

- Describe some formal and informal “uniforms” that you wear. Why do you wear them?

- What statements do various uniforms make about the people wearing them?

- Based on our discussion of uniforms, how would you describe the language of uniforms? How is the language of uniforms similar to and different from the language we typically speak?

More ambitious than any of these investigations, however, and an excellent example of the sort of learning experience that investigations can provide and the quality of work students are capable of, is a project completed by Scott Rasmussen and Derek Oosterman (1999), two seniors at Minnetonka High School in Minnesota. Scott and Derek’s project, which they completed as part of an advanced placement psychology class, was designed to investigate procedures for teaching vocabulary. Their goal was to “determine the best means of vocabulary acquisition in high school students” (p. 1). They began with a review of the literature. Based on their reading, they then developed this set of hypotheses:

Methods with a weightier impact on neural connections will have greater success in encoding, storage, and retrieval. Processing is theorized to be stronger when it is applied (1) continuously and frequently, (2) approached explicitly and actively, or (3) aided with creative clues incorporating several senses. (p. 1)

To investigate these hypotheses, Scott and Derek worked with three English teachers and 12 high school classes, and arranged a number of experimental comparisons. For example, in one experiment,

Classes were presented the words in ways successively involving more and stronger sensory clues. The first class was a control, and took the test with absolutely no instruction, or with zero senses involved. The next class was presented the information visually on an overhead, but with no auditory instruction. The third class was presented the information verbally, but with no visual information. The last class learned with the aid of both the verbal sense with the overhead and the auditory sense with the researchers reading the words and definitions. (pp. 1–2)

The hypothesis investigated in this part of the study was confirmed: Incorporating more senses led to better word learning, with the four groups described above receiving scores of 42%, 77%, 74%, and 86%, respectively. Not surprisingly, other results confirmed some of their hypotheses and failed to confirm others.

The point is not so much what Scott and Derek learned about vocabulary instruction as the extent to which the experience is likely to leave them with a heightened awareness of words. I have corresponded with one of these young researchers, Scott, about his work, and he reports that he now pays more attention to words than he used to. “Before the study,” he wrote, “I never gave vocabulary much thought…. In regular conversations and school classes now, I am increasingly cognizant of how words can influence perception and meaning.” Although investigations as complex as Scott and Derek’s are likely to be rare, almost any study in which students examine some lexical phenomena is likely to leave them more conscious of words.

Having presented a complex and lengthy example of an original investigation, I will end the section with a very simple one, one appropriate for a variety of ages, and one you can use repeatedly when you have a few minutes available. Google Ngrams (books.google.com/ngrams) allows you or a student to submit words or phrases and trace the usage of them over time. For example, the Ngrams home page gives an example of the names Frankenstein, Albert Einstein, and Sherlock Holmes, showing that the name Frankenstein first occurred in about 1800, Sherlock Holmes in about 1850, and Albert Einstein, in about 1920. It also shows that all three names are still frequently used, with Frankenstein being the most frequent, Einstein the next most frequent, and Holmes the least frequent. You could show students this result, ask them to choose some real or imagined characters they are familiar with, and enter the names in Ngrams to see when these characters were mentioned and how they have continued to appear or have become less frequent over time. For example, as shown in Figure 7.2, adding Martin Luther King to that list would show that Dr. King’s name first became prominent in the late 1950s, rose in popularity until about 1970, dropped somewhat in popularity from 1970 to 1980, has gained in popularity since that time, and now appears much more frequently than Frankenstein, Einstein, or Holmes.

Figure 7.2. Google Ngrams Chart for Albert Einstein, Frankenstein, Martin Luther King, and Sherlock Holmes

TEACHING STUDENTS ABOUT WORDS

Most of the activities discussed thus far encourage students to become aware of words, manipulate them, appreciate them, and play with them in ways that do not involve explicit instruction from you. In this section of the chapter, I consider some knowledge about words that teachers and teacher educators should definitely have and the possibility of explicitly instructing students on some of these. The section draws heavily on a chapter by Nagy and Scott (2000) in which they discuss the complexity of word knowledge and the role of metalinguistic awareness in learning words.

The Complexity of Word Knowledge

According to Nagy and Scott (2000), if we are to understand the processes underlying students’ vocabulary growth—and, I would add, if we are to effectively assist that growth—we must recognize at least five aspects of the complexity of word knowledge. These aspects are incrementality, multidimensionality, polysemy, interrelatedness, and heterogeneity. More recently, Scott and Nagy (2004) added a sixth aspect, understanding the role of definitions, context, and word parts in vocabulary learning.

Incrementality. Word learning is incremental; that is, it proceeds in a series of steps. As Clark (1993) has pointed out, the meanings young children initially assign to words are incomplete, but over time these meanings become increasingly refined until they eventually approximate those of adults. Dog, for example, may at first refer to any small animal—dogs, cats, hamsters, squirrels—and only later be applied exclusively to dogs. School-age children and adults take a similar course in learning many of the words they eventually master. Dale (1965) attempted to capture this incremental nature of word learning by proposing four levels of word knowledge: (1) never having seen it before; (2) knowing there is such a word, but not knowing what it means; (3) having a vague and context-bound meaning for the word; and (4) knowing and remembering it. Dale’s fourth level could be further broken down—into, for example, having a full and precise meaning versus having a general meaning, or using the word in writing versus only recognizing it when reading. However levels of word knowledge are defined, it is clear that reaching high levels is no mean task. McKeown, Beck, Omanson, and Pople (1984) found that even 40 high-quality instructional encounters with words did not bring students to a ceiling. It is also clear that high levels of word knowledge are needed to effect reading comprehension, and that only very rich instruction produces such high levels (Beck et al., 2013; Stahl & Fairbanks, 1986; Stahl & Nagy, 2006).

Multidimensionality. The second aspect of word knowledge, its being multidimensional, is in some ways a qualification of the first. Although it is useful to think of levels of word knowledge, in actuality there is no single dimension along which differences in word knowledge can be considered. As I pointed out in Chapter 2, Calfee and Drum (1986) note that knowing a word involves “depth of meaning; precision of meaning; facile access …; the ability to articulate one’s understanding; flexibility in the application of the knowledge of the word; the appreciation of metaphor, analogy, word play; the ability to recognize a synonym, to define, to use a word expressively” (pp. 825–826). To this, I would add a central theme of this chapter, that word knowledge has both a cognitive and an affective component.

Polysemy. The third aspect of words, polysemy, refers to the fact that many words have multiple meanings. Polysemy is more frequent than it is often thought to be; a lot of words have multiple meanings, and the more frequent a word is the more likely it is to have two or more meanings. Additionally, it is worth recognizing that the multiple meanings of words range from cases in which the meanings are completely unrelated (the bank of a river versus the bank where you cash checks) to cases in which the differences are so subtle that it is difficult to decide whether or not they are indeed different meanings (giving Mary $10 versus giving Mary a kiss). Moreover, words virtually always gain some meaning from the context in which they are found, with the result that meanings are infinitely nuanced.

Interrelatedness. The fourth aspect of words to note is their interrelatedness: A learner’s knowledge of one word is linked to her knowledge of other words. To use Nagy and Scott’s example, “How well a person knows the meaning of whale depends in part on his or her understanding of mammal. A person who already knows the words hot, cold, and cool has already acquired some of the components of the word warm, even if the word warm has not yet been encountered.”

Heterogeneity. The fifth aspect of words to be concerned with is their heterogeneity: What it means to know a word is dependent on the type of word in question. To again use Nagy and Scott’s example, “knowing function words such as the or if is quite different from knowing terms such as hypotenuse or ion.” But it is not just different words that require different sorts of knowing. Different word users require different sorts of word knowledge. As a potential purchaser of a diamond engagement ring, a young man is certainly better served if he has some knowledge of diamonds. As a seller of diamond rings and possibly a large-scale purchaser of diamonds, a jeweler needs and typically has considerably more knowledge of diamonds than her customers. And as the artisan and artist who shapes a beautiful stone from an unremarkable piece of rock, a diamond cutter must have both richer and quite different knowledge than the jeweler.

Definitions, Context, and Word Parts. This last aspect of words that Scott and Nagy consider includes topics that I have discussed in detail in Chapter 6 as part of teaching students word-learning strategies. The point that Scott and Nagy make about the need for students to understand word-learning strategies is that in addition to knowing how to use word-learning strategies, students need to know some things about word-learning strategies. Most notably, students need to understand when to use these strategies, when not to use them, and the strengths and limitations of each of them. Dictionary definitions, for example, are useful for checking on the meaning of a word you think you know or for getting some general idea of a word’s meaning. They are not useful for learning rich and precise meanings of words. Somewhat differently, it is useful for students to understand that many English words come from Latin and Greek roots.

The Role of Metalinguistic Awareness in Word Learning

What sorts of metalinguistic awareness of words and word learning are important to teachers and to students? The question with respect to teachers can be easily answered. Everything in this section of the chapter, everything in Nagy and Scott’s chapter, and a good deal of the information contained in the references to this chapter and to Nagy and Scott’s chapter is important for teachers. Understanding incrementality, multidimensionality, polysemy, interrelatedness, and heterogeneity, cannot help but be valuable to you as you work with students. Additionally, Andrews’s Language Exploration and Awareness (2006) offers a number of insights about words and about other aspects of language that teachers and teacher educators should find useful, and Zwiers’s Building Academic Language: Meeting Common Core Standards Across the Disciplines, Grades 5–12 (2014) provides useful information on the broader topic of academic language and what teachers need to know to help students meet the Common Core standard. Also, a chapter by Nagy (2007) contains an extremely convincing argument for the importance of metalinguistic awareness.

The answer with respect to students is not as easily arrived at. While some metalinguistic awareness about words and word learning can certainly be valuable to students, just what students need to learn and how they can best learn it are matters yet to be decided. One could attempt to directly teach students a body of knowledge about words much like instruction in traditional grammar was once used to teach knowledge about sentences. But I strongly suspect that such an attempt would yield poor results, and perhaps even produce the negative attitude toward words that grammar instruction often produced toward language study. Instead, it seems likely that much of this knowledge should be imbedded in students’ ongoing work with words and be brought to conscious attention as appropriate opportunities arise.

Here are three examples. Polysemy can be appropriately dealt with when students are being instructed in using dictionaries or when they are actually using them to look up word meanings. Certainly, one of the principles students should follow when looking up definitions is to choose the definition that fits the context in which they find the word, and this means recognizing that words have different meanings that are both shaped and revealed by context. Incrementality can be appropriately dealt with when students are learning to use context to unlock word meanings. Something that students learning to use context clues to identify word meanings need to recognize is that a single instance of a word in context is likely to reveal only a small increment of a word’s meaning, but that each additional instance of the word in context is likely to reveal another increment. Finally, interrelatedness can be appropriately dealt with when students are learning new concepts, particularly when they are learning concepts in a relatively unfamiliar domain. Students who are studying literary elements of narratives, for example, will need to learn the meanings of rising action, falling action, and plot as part of learning the meaning of climax; and the context of their doing so provides an excellent opportunity for introducing the notion of the interrelatedness of words.

Additionally, students will learn a lot about words as part of engaging in many of the informal learning experiences described throughout this chapter. The adept diction that professional writers use is possible because there are so many different words available to choose from. Much wordplay—puns, for example—works because words have multiple meanings. And intensive instruction is necessary because word learning is an incremental process. These and other insights about words can be briefly pointed out as students are involved in these various activities.

Figure 7.3. Give Me a Big W?

As these considerations of teaching students about words demonstrate, some approaches to word consciousness are fairly complex and academic, and such approaches certainly have a place. Nonetheless, we need to remember that one definite purpose of word-consciousness work is to foster our students’ enthusiasm about words, a fact illustrated in Figure 7.3.

AN ACTIVITY THAT BOTH FOSTERS WORD CONSCIOUSNESS AND TEACHES INDIVIDUAL WORDS

I have presented each of the four parts of the comprehensive vocabulary program described in this book in separate chapters so that I could describe each part thoroughly. But of course in your classroom, the parts will often be intertwined. Here as an example of this is an activity that both fosters word consciousness and teaches individual words. The approach was designed by Manyak (2007) and has been termed Character Trait Analysis. There are many colorful and sophisticated words that authors use to describe the characters in stories or informational books that students read or that you read to them. Focusing on these words gives students a vocabulary with which to describe these characters and gives you an opportunity to introduce some interesting words.

Figure 7.4. Character-Trait Words Supplied by Manyak (2007)

Kindergarten Terms: brave, careful, cheerful, clever, confident, considerate, curious, dishonest, foolish, gloomy, grumpy, honest, intelligent, impatient, irresponsible, patient, reliable, selfish, ungrateful, wicked

1st-Grade Terms: arrogant, calm, cautious, considerate, cowardly, courageous, cruel, dependable, fearless, ferocious, gullible, humble, inconsiderate, loyal, mischievous, miserable, optimistic, pessimistic, undependable, wise

2nd-Grade Terms: argumentative, bold, careless, conceited, envious, faithful, independent, insensitive, irritable, modest, predictable, self-assured, sensible, stern, sympathetic, stern, supportive, timid, unpredictable, unreliable

3rd-Grade Terms: admirable, appreciative, carefree, demanding, indecisive, egotistical, innocent, insensitive, irritable, modest, persistent, prudent, rambunctious, rash, sensitive, spiteful, sympathetic, tolerant, trustworthy, unsympathetic

4th-Grade Terms: assertive, cordial, cunning, defiant, fickle, haughty, hesitant, indifferent, meek, menacing, noble, perceptive, pompous, reckless, ruthless, skeptical, submissive, surly, unassuming, uncompromising

5th-Grade Terms: apprehensive, compliant, corrupt, cross, depraved, dignified, discreet, docile, ethical, frank, glum, ingenious, lackadaisical, malicious, plucky, prudent, rebellious, selfless, sheepish, sullen

Fortunately, and this is what gives this approach great potential for fostering word consciousness, Manyak (2007) has provided sets of character-trait words for each of grades 1–5. These are shown in Figure 7.4. If teachers within a school would all agree to teach the words for their grade level and review those from previous grade levels each year, students would be repeatedly exposed to a set of interesting and useful words, and teachers would be making a coordinated and conscious effort to teach these words. Here is how the procedure works:

- Explain to students that there are lots of interesting and colorful words that describe characters, and tell them that they are going to work with some of these words.

- Choose a text with some interesting characters that can be described with colorful terms such as those listed in Figure 7.4.

- Choose from the grade-appropriate list six or so terms appropriate for your students and the text you have selected.

- Introduce the terms, define them, and tell students they can be used to describe the characters in the upcoming reading.

- Read the text aloud, stopping after characters have been described and soliciting character-trait terms from the list to describe them. List these on the board as you go.

- After reading the selection, go back to the list and explain what you have been doing. Also, point out that character-trait terms can also be used to describe and understand real-life figures students learn about in history, science, and other subjects. Celebrate students’ use of these terms, tell them that when you read other selections you will sometimes focus on these terms and additional character-trait terms, and as always celebrate and advertise word consciousness.

This approach can of course be modified for older students and for somewhat-different purposes. Lists can be made for grades 6 and up, and again it would be terrific for fostering students’ word consciousness as well as for nurturing teachers’ attention to word consciousness if lists could be developed for each grade, with teachers in successive grades agreeing to both teach their list and review those from lower grades. In middle and high school, it would probably work best to coordinate the use of lists for various subject matters: English teachers could work with one set of lists, social studies teachers with another, and so on. Again, it is important to note that character-trait terms apply not just to characters in stories but can be useful in describing real-life figures.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The purpose of this chapter has been to define and elaborate on the concept of word consciousness, to argue for the importance of word consciousness as a deliberate goal of vocabulary instruction, and to suggest some approaches to fostering word consciousness. The student who is word conscious knows a lot of words, and she knows them well. Equally importantly, she is interested in words, and she gains enjoyment and satisfaction from using them well and from seeing or hearing them used well by others. She finds words intriguing, recognizes adroit word usage when she encounters it, uses words adroitly herself, is on the look out for new and precise words, and is responsive to the nuances of word meanings. She is also cognizant of the power of words and realizes that they can be used to foster clarity and understanding or to obscure and obfuscate matters. Given the size and complexity of the task of learning tens of thousands of words, developing students’ word consciousness so that they have both the will and the skill to improve their vocabularies is hugely important. However, despite the importance and complexity of the vocabulary-learning task, it makes good sense to keep most efforts to foster word consciousness light and low keyed. Whenever possible word-consciousness activities should encourage a playfulness like that shown in these snippets of wordplay I recently came across:

- If ignorance is bliss, why aren’t more people happy?

- Why is the man who invests all your money called a broker?

- When cheese gets its picture taken, what does it say?

Or playfulness like that shown by these winners of the Washington Post’s annual contest in coming up with alternative meanings for words:

- flabbergasted—appalled over how much weight you have gained

- lymph—to walk with a lisp

- coffee—the person upon whom one coughs