CHAPTER 8

Special Considerations for English Learners

All students need direct instruction of vocabulary, but it is especially imperative for ELs. They need much more exposure to new vocabulary than their native English-speaking classmates.

—Jodie Haynes, EL Specialist

As the number of English learners in the United States continues to grow, providing ELs with the best possible vocabulary instruction becomes increasingly important and part of virtually every teacher’s job. As August and Shanahan (2006) note, ELs rarely reach the same level of text-level skills as their native English-speaking counterparts, and one important reason for this is their limited proficiency with English vocabulary. Not only do many ELs not know as many words as their native English speaking peers, but they often have less in depth knowledge of the words they do know (Hogan, 2015). Because the vocabulary learning task many ELs face is large, we need to promote their word learning in as many ways as possible. Thus, the “direct instruction” to which Haynes refers in the opening quotation refers not just to teaching individual words but also to the other ways of promoting word learning described in this book, to providing rich and varied language experiences, teaching word-learning strategies, and fostering word consciousness.

Fortunately, the vast majority of approaches that are effective for native English speakers are equally effective for English Learners. However, as Goldenberg (2008) notes, some approaches will be most effective with ELs when they include some accommodations. In the remainder of this chapter, I first discuss some general principles of effective instruction that are applicable for all students but particularly important for students who may struggle in school. Next, I discuss effective instruction for ELs. After that, I consider some modifications or emphases to make to each part of the four-part program to better serve ELs. And finally I describe supporting ELs reading with Scaffolded Reading Experience.

SOME GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF EFFECTIVE INSTRUCTION

Providing the best instruction possible is of course a goal with all students; however, it is particularly important for English Learners, who need and deserve the very best instruction we can possibly provide. Here, I list principles from two lines of research and theory. The first set might be termed traditional principles, and comes from research and theory developed in the 1960s and 1970s (see, for example, Anderson & Pearson, 1984; Brophy & Good, 1986; Gardner, 1987). The second set grows out of constructivist and social cultural theory, which became prominent in the United States in the 1980s and 1990s (see, for example, Gaffney & Anderson, 2000; McVee, Dunsmore, & Gavelek, 2005), and some other recent considerations, specifically the emphasis on motivation (Guthrie, 2015; Wentzel & Wigfield, 2009), transfer (Dewitz & Graves, 2014; Perkins & Salomon, 2012; Salomon & Perkins, 1989), and teaching for understanding (Gardner, 1998; Perkins, 1998).

Traditional Instructional Principles

- Focus on academically relevant tasks, that is, on important topics, skills, and strategies that students really need to master. Time is at an absolute premium in the classroom and something we cannot afford to squander on unimportant matters.

- Employ active teaching. Know your subject well, be the instructional leader in your classroom, and actively convey the content to be learned to students in presentations, discussions, and demonstration.

- Foster active learning. Give students opportunities to manipulate and grapple with the material they are learning. For example, after students learn a new word, you might have them distinguish between contexts in which it is clearly appropriate and ones in which it does not quite fit.

- Distinguish between instruction and practice. Instruction consists of teaching students knowledge, skills, or strategies. Practice consists of asking students to use the knowledge, skills, or strategies that they have already been taught.

- Provide sufficient and timely feedback. Whenever possible, respond to students’ work with immediate and specific feedback.

Instructional Principles Motivated by Constructivist and Sociocultural Theory and Other Current Considerations

- Ensure that students are active participants in their own learning. Meaningful learning, learning that gives students the ability and motivation to use the knowledge and skills they learn, requires students to actively engage in that learning.

- Scaffold students’ efforts. Provide students with the temporary support they need to complete tasks they cannot complete independently.

- Provide instruction in students’ zone of proximal development. Instruct students at a level that challenges them but allows them to achieve with effort.

- Follow the gradual-release-of-responsibility model. Begin instruction on difficult topics by initially doing much of the work yourself; then over time give students increasing responsibility for the work until eventually they are doing all of it.

- Use cognitive modeling. Think aloud for students, demonstrating the thinking you employ as you complete a task you are teaching them to do.

- Use direct explanation. In teaching strategies, (1) give students a description of the strategy and when, how, and why it should be used; (2) model it; (3) work along with students as they use the strategy; (4) gradually give students increased responsibility for using the strategy; and (5) have students use the strategy independently.

- Ensure that students contextualize, review, and practice what is learned. Real learning takes time, effort, and a lot of practice.

- Teach for understanding. Teach in such a way that students understand topics fully, remember important information, and actively use what they have learned.

- Teach for transfer. Transfer seldom occurs automatically. If you want students to use what they have learned in one context in a new context, you need to show them how to do so.

EFFECTIVE INSTRUCTION FOR ENGLISH LEARNERS

A number of educators have made recommendations for effective instruction with English learners. Three that are particularly applicable here are Claude Goldenberg’s basic tenets for working with ELs; Graves, August, and Mancilla-Martinez’s recommendations for tailoring vocabulary instruction to ELs; and Lisa Delpit’s principles for working with poor urban children, many of which apply to ELs.

Goldenberg’s Broad Generalizations About Teaching English Learners

Claude Goldenberg has written extensively about powerful instruction for English learners (Goldenberg, 2008, 2013; Goldenberg & Coleman, 2010; Goldenberg & Wagner, 2015). Here are three of his generalizations that serve as fronting for the more specific advice I give in the next several sections of the chapter:

- Teaching students to read in their first language promotes higher levels of reading achievement in English. Beginning reading instruction is not the topic of this book or something that most of you reading this book can control, but it is still worth knowing this research-based finding.

- What we know about good instruction and curriculum in general often holds good for ELs as well. The fact that what generally holds does not always hold is important to note. It means that we can rely a good deal on what we know about good teaching generally, but need to be always ready to modify our instruction.

- ELs sometimes require instructional accommodations when instructed in English. In many cases, these accommodations will be simple and easily implemented. At other times, however, they will not be simple and may require a substantial amount of your time and effort.

Graves, August, and Mancilla-Martinez’s Recommendations on Vocabulary Instruction for English Learners

In writing a book focusing specifically on vocabulary instruction for English learners, Diane August, Maria Mancilla-Martinez, and I (Graves et al., 2013) developed a number of recommendations designed to maximize the effectiveness of instruction. Here are the central ones:

- More words will need to be taught. Some of these will be basic words; some will be general academic vocabulary; and some will be domain-specific academic vocabulary. As Wright and Neuman (2013) found in their study of core reading programs, instruction sometimes focuses on words that are too simple. But that does not mean that students do not need to master a basic vocabulary. As I pointed out in Chapter 3, it is absolutely crucial that students know the first 4,000 most frequent English words, words that make up 80–90% of the words appearing in virtually any text they will read. At the same time, knowing less frequent words that occur across a variety of texts, and less frequent words that appear in various subject matters such as social studies, math, and science is also crucial (Graves, 2015b; Neuman & Wright, 2014; National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers, 2010). All in all, this means that ELs have a huge word-learning task. They need to learn words at a faster rate than their English-only peers in order to catch up with them.

- More words are likely to represent new concepts and not merely new labels. Many words that are familiar concepts for native English speakers raised in the United States may represent new concepts for English learners, particularly for ELs who have come to the United States from a different culture. At the same time, we need to remember that the fact that an EL does not know an English word does not mean he does not know the concept represented by the word.

- Making use of ELs’ strengths in their first language will often prove beneficial. There was a time when many authorities recommended against using students’ native language. Thankfully, that time is over. Allowing each student to use his native language and using it yourself if possible can provide very strong scaffolding for your ELs. Some of the many places you can use students’ first language are in preteaching vocabulary, previewing an upcoming selection, providing background information prior to their reading in English, and reviewing newly taught and particularly challenging upcoming tasks or assignments, as well as in teacher-student interactions and instructional conversations.

- ELs are likely to need more instruction, multiple exposures, and multiple contexts. Unfortunately, providing more instruction, multiple exposures, and multiple contexts takes time. One of the major challenges in teaching ELs is to somehow find this time.

- Rhymes, poems, and games can be particularly useful. Don’t think of these as simply games; think of them as powerful vehicles for instruction and for practice. For example, you might ask students to act out word meanings.

- Pictures, demonstrations, concrete objects, and video are likely to be both needed and effective. So too are visuals, gestures, graphic organizers, other types of graphics, concept maps, and models of the task to be done. All of these nonlinguistic devices support students’ use of the new language they are learning.

- Partnering ELs with strong native English speakers and partnering ELs with weaker English skills with those ELs with stronger English skills are very often effective strategies. In fact, this is something I would definitely try in classes with ELs.

- Identify and clarify potentially difficult vocabulary before students read a selection. Doing so is very important, but as explained throughout this book, this is only one part of a comprehensive vocabulary program.

- Give ELs the tools they need to learn words on their own, and be sure these tools are at an appropriate level. This means providing classroom sets of dictionaries such as the Collins COBUILD New Student’s Dictionary (2005), the Vox Spanish and English Student Dictionary (2012), and the Scholastic Dictionary of Idioms (Terban, 2006). It also means locating simpler dictionaries if your students need them and creating glossaries of particularly useful words and phrases for your students and your classroom.

Delpit’s Principles for Working with Poor Urban Children

Some years ago, Lisa Delpit (1996) developed a set of principles for working with poor urban children. Many of the children who do not speak English as a native language are urban and poor. Many are not. However, most of what Delpit says applies to children who are learning a second language, even if they are not poor or urban. In fact, it is reasonable to suggest that these principles apply to all children. Here, I list those that seem particularly relevant for English learners.

- “Whatever Methodology or Instructional Program Is Used, Demand Critical Thinking.” Often, we fall into the trap of thinking that students who are from lower socioeconomic classes or who speak a different language are not as bright as other students. Consequently, we often reason that they cannot handle critical thinking. All students need and deserve to develop and use critical thinking skills, and all students are capable of doing so.

- “Ensure That All Children Gain Access to Basic Skills, the Conventions and Strategies That Are Essential to Success in American Education.” We sometimes dumb down the curriculum for children who do not meet the traditional standards. Further, we may begin teaching non-native speakers with less emphasis on skills than middle-class children typically receive. This will not work! All students need to master the building blocks that lead to becoming fully literate.

- “Provide the Emotional Ego Strength to Challenge Racist Societal Views of the Competence and Worthiness of the Children and Their Families.” English learners all too often encounter racism and classism. We must support second-language students’ egos and help them build the sort of self-worth that will lead them to persevere when they encounter challenges. Creating an “I can do it!” attitude in your ELs and conveying to them that you as their teacher hold an “I can help you do it!” attitude are crucial.

- “Recognize and Build on Students’ Strengths.” The importance of building on students’ strengths is such a truism, repeated so often, that it often does not have a great deal of meaning for many of us. Just how do we “build on a strength”? What building on strength means is that we should begin with what a child can do best and work toward those things that a child does not know or does not do well. Give students challenges they can meet and a steady diet of success by scaffolding their efforts as they move from the known to the new, and then gradually release responsibility to the students themselves as their competence and confidence grows.

- “Use Familiar Metaphors and Experiences from the Children’s World to Connect What They Already Know to School Knowledge.” We know the importance of background knowledge. Instead of assuming that all children enter your classroom with the same background knowledge, learn what your English learners do and don’t know, and use that as the basis of teaching.

- “Create a Sense of Family and Caring.” It is crucial that all students feel that they are a valuable part of the class and will be supported in their efforts by both you as the teacher and by the other students. Make your classroom a literate environment, an environment in which children respect each other, support each other, and feel free to make use of their English skills even if those skills are not fully developed.

- “Monitor and Assess Needs and Then Address Those Needs With a Wealth of Diverse Strategies.” Effective teaching cannot be done without careful assessment and evaluation of what students know and learn. We need to be vigilant to ensure that we use a wide range of techniques for gauging students’ strengths and weaknesses and creating ways to build on their strengths. These techniques are likely to include the use of formal tests, but they will also include talking to students, carefully observing them as they work at school tasks, and seeking insights from parents and others in your ELs’ home communities.

- “Honor and Respect Children’s Home Cultures.” Knowledge that has been gained in children’s home culture constitutes a strength that can be brought into the classroom and used as the basis for successful learning in school. The goal is to support students’ attempts to maintain their cultural identities and to support their becoming successful in the mainstream culture represented by the school.

- “Foster a Sense of Children’s Connection to Community—To Something Greater Than Themselves.” The purpose of learning in school is to be able to do something beyond school. Of course, given the nature of our society, students have to do well in school to do well beyond it. Consider talking to students about the contributions of others in their community and what they can contribute as they become adult members of the community.

As I have said, Delpit’s principles are clearly applicable to all students, but they are particularly applicable to English Leaners. All children need and deserve the sorts of instruction and support that Delpit suggests. Children who come to school having to master a new language, and quite possibly a new culture, especially need and deserve them.

SUGGESTIONS FOR MODIFYING EACH OF THE FOUR PARTS OF THE PROGRAM

As Goldenberg (2008, 2013) noted, what we know about good instruction and curriculum in general usually holds for English learners, but ELs will sometimes need accommodations. This is true with respect to the four-part vocabulary program described in this book. Much of the four-part program will serve native English speakers and ELs equally well, but some parts of the program need to be modified. Here, I discuss possible modifications for each part of the program.

Providing Rich and Varied Language Experiences

Like their English-only counterparts, English learners need rich and varied experiences in listening, discussion, reading, and writing. Here, I emphasize four points to keep in mind as you work to provide ELs with such experiences. First, because ELs have had less experience with English outside of school, they need more experiences in school. This means devoting more time to providing those experiences. After-school programs and summer-school programs have some real potential here. If ELs are to catch up with their EO (English only) classmates (who are continuing to build their vocabularies), they need extra time to do so. Second, while we know that using an EL’s native language can be extremely useful, we also know that ELs need to spend as much time as possible dealing with English. This means that ELs’ native languages should be used judiciously.

It is also very important to remember that many ELs are among the students that need to build their oral English so that they can use their oral vocabularies to understand and contribute to what is happening in the classroom and as a foundation for building their reading vocabularies. The interactive oral reading techniques I described in Chapter 4 are definitely appropriate for primary-grade ELs with small oral English vocabularies, and with modifications can be made appropriate for older ELs with small oral English vocabularies.

Finally, an idea put forth by Nation (2014) for building the vocabularies of college-age students learning English as a foreign language suggests the importance and potential benefits of substantial amounts of independent reading for any students working to learn English. Nation argues that a vocabulary of about 9,000 word families would allow college-level students to read 98% of the running words in a wide range of texts and “estimated that readers can move from elementary levels of vocabulary knowledge in a second language (knowledge of 2,000 word families) to a very high level (knowledge of 9,000 word families) after a total 1,223 hours of reading, about one hour a day over three years” (Krashen & Mason, 2015, p. 11). While school-age ELs are unlikely to read 1 hour a day for 365 days day a year, Nation’s analysis shows the importance and potential of independent reading.

Teaching Individual Words

Maximizing English learners’ learning of individual words requires somewhat greater modifications than does providing ELs with rich and varied language experiences. There are three main differences that require modifications.

First, English learners have smaller English vocabularies than many of their English-only classmates, in many cases considerably smaller vocabularies. Therefore, ELs will need to learn more words, in many cases considerably more words. This means that you need to spend more time teaching vocabulary, although as I noted above finding that time is a real challenge. It also means that ELs should spend time learning words independently or perhaps working with an EO classmate. The words they work on can be ones you identify as likely to be unfamiliar to your ELs when using the SWIT procedure described in Chapter 3 to identify useful words to teach from individual selections. Or they can be words from some of the word lists described in Chapter 3:

- The First 4,000 Words (Graves, Sales, & Ruda, 2008)

- Words Worth Teaching in Kindergarten Through Grade 2 list and Words Worth Teaching in Grades Three to Six list (Biemiller, 2009)

- Landscape of American English list of the vocabulary of core reading programs (Graves, Elmore et al., 2014)

- Landscape of American English list of the vocabulary of elementary content content-area programs (Fitzgerald, Elmore, & Stenner, 2015)

Clearly, you will need to choose among these lists and choose words within the lists, and equally clearly you will need to make some assessment of your ELs’ vocabularies. Information on possible assessment procedures are provided in Chapter 3.

A second difference in teaching individual words to ELs is that some ELs lack a basic English vocabulary of frequent words, words that most EO students will have acquired before beginning school. As I noted in Chapter 3, The First 4,000 Words, the most frequent English words, make up 80–90% or more of the words students will encounter as they read. If students cannot read these words, they must to learn to do so, and they need to do so quickly, so that they are not constantly encountering unknown words as they read and become frustrated with learning to read and quite possibly with school generally. I recommend using the Reading Vocabulary Test to test ELs in grades 4 and above that you suspect do not know many of these words (Sales & Graves, 2009c), identifying students who do not know a substantial number of these words, and systematically teaching the words beginning at the point in the sequence (the words are listed from most frequent to least frequent) at which students know less than 80% of the words.

The third difference in teaching individual words to ELs is that some words that merely represent new labels for known concepts for EO students will represent new concepts for ELs. Thus, instead of using one of the procedures for teaching new words representing known concepts such as Context-Dictionary-Discussion or the Context-Relationship Procedure, you may need to use one of the procedures for teaching new concepts, such as the Frayer Method or Semantic Mapping. Admittedly, these more robust procedures take more time, a resource always at a premium with ELs, but be that as it may, extra time may be what it takes to get the job done.

Teaching Word-Learning Strategies

Teaching word-learning strategies is the part of the four-part program requiring the greatest modifications for ELs, all of them additions. ELs need the same word-learning strategies that EO students do, but they also need work in three other areas.

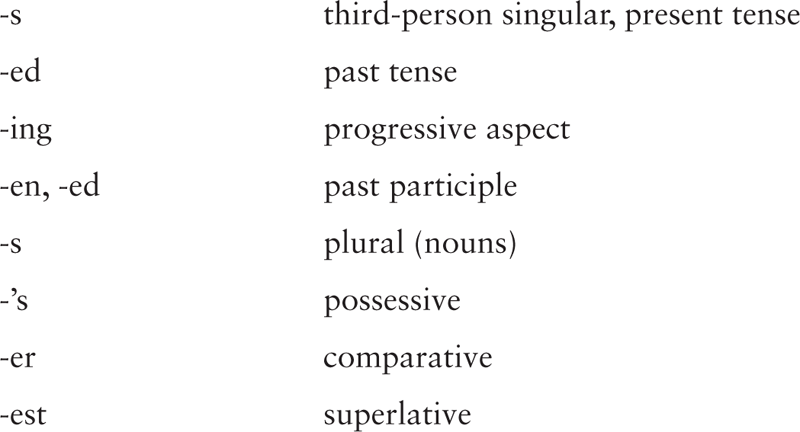

First, unlike students who learn English as their first language, many ELs do not have tacit knowledge of the grammatical functions of English inflections and therefore need to be taught how to deal with them. For example, they may not know that -ed indicates the past tense. Fortunately, the number of inflections is quite limited, as can be seen from the list below:

In keeping with the schedule suggested in the Common Core, you could begin this work in kindergarten; however, ELs of many ages may need to learn to deal with English inflections. In teaching inflections, it is important to first explain the difference between roots (the part of the word that caries the meaning and has no parts added) and inflections (a letter or letters added to the end of the word that changes it just a bit). For example, -s or -es added to a word sometimes indicates that there is more than one. The word plant refers to a single plant, while the word plants refers to more than one plant. Similarly, the word horse refers to one horse, while the word horses refers to more than one horse. Showing pictures of one plant and a group of plants and one horse and a group of horses, with each picture labeled with the correct form of each word, should be helpful. After you introduce an inflection, students should have opportunities to practice with it as a group, in pairs, and eventually on their own. Reviewing students’ work is also important. Finally, inflections might be grouped together for instruction by type—those related to verbs, possessives, and comparatives and superlatives. After students have mastered one inflection, teach another and then give them practice working with more than one inflection at a time. With students in grades 2 and above, you can reinforce their awareness of inflections by having them find and underline inflections they have learned in material they are reading in class and then discuss the meanings of the inflection and the inflected word as a group. You can also ask students to work with a partner to make up their own sentences using particular inflections.

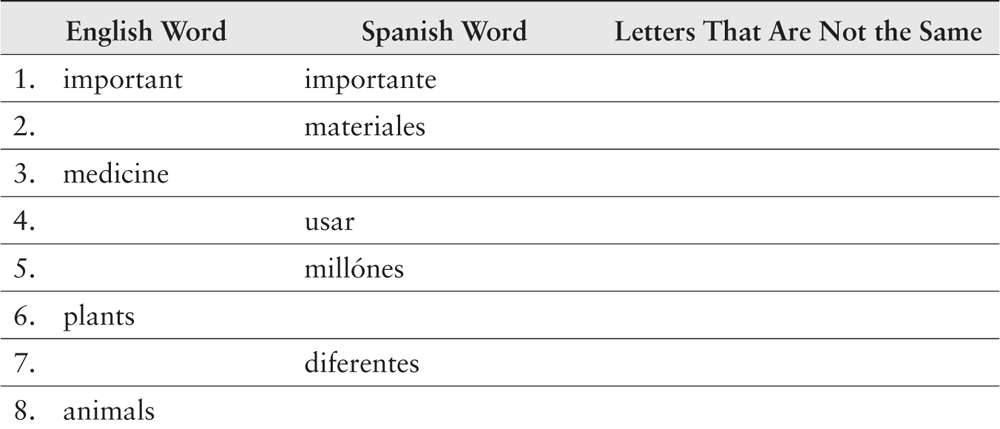

Using cognates is another word-learning strategy that is important and only relevant for ELs. Cognates are words that have similar spellings, similar meaning, and sometimes similar pronunciations across two languages. Teaching Spanish-speaking children to take advantage of their cognate knowledge is a particularly powerful tool because many English words that are cognates with Spanish are high-frequency Spanish words, but low-frequency English words. Thus, students are likely to know the words in Spanish but lack the English label. Moreover, many of the words that are cognates are words that have importance and utility; they are characteristic of mature language users and appear frequently across a variety of domains, and they have instructional potential because they are words that can be worked with in a variety of ways so that students can build rich representations of them and their connections to other words and concepts. Examples include singular/singular, event/evento, and portion/porción.

Research supports the commonsense notion that students are more likely to recognize cognate pairs that sound alike and are spelled alike (for example, amorous/amoroso). In addition, students’ levels of first-language literacy and first-language knowledge of a word’s meaning influence the ease of recognizing cognates. Cognate strategy instruction generally helps students draw on their first-language knowledge by (1) briefly explaining what cognates are, (2) giving students an opportunity to find cognates in authentic text, and (3) helping students realize that while cognates are similar in sound, spelling, and meaning, there is a range in how similar cognates are (August et al., 2005). Figure 8.1 shows a worksheet useful in introducing the concept of cognates, and Figure 8.2 illustrates some instruction on the cognate strategy.

Learning to deal with idioms is another word-learning strategy uniquely important for English learners. The English language is rich with idioms, expressions such as “bird in the hand” and “wet blanket.” The Longman American Idioms Dictionary (2000), for example, lists over 4,000 of them. These seldom present difficulties for native English speakers, who grow up using these expressions. But they can be extremely confusing to ELs. A student who has learned the words feather and nest may think he understands them. But then he reads that “it may not be good thing to feather your nest.” What is he to do? Even though he knows all the words, the sentence makes no sense.

Instruction in learning to deal with idioms is straightforward. First, present several examples of idioms: bird in the hand, wet blanket, feather your nest, rumor has it, and the like. Next, explain what an idiom is, saying something like, “An idiom is a group of words having a meaning different from the meanings of the individual words.” Present more examples, and ask students if they know any idioms. Then, explain that dealing with idioms is simple, saying something like, “When you come across a group of words that you know but the group together makes no sense, ask an English-only classmate or your teacher what the phrase means.” That is really all there is to the initial instruction. Finally, to solidify ELs’ understanding of the concept of idioms and give them practice in dealing with them, have them collect idioms they come across, and from time to time share and discuss these in class.

Figure 8.1. Cognate Strategy Instruction: Introduction to Cognates

Directions:

- Look at the word televisión in Spanish and television in English. What do you notice?

- Cognates are words that mean more or less the same thing in English and Spanish, sound alike, and look alike.

- What is the English word for problema? Are problema and problem cognates? Why or why not?

- What English word means the same thing as the Spanish pie? Are pie and foot cognates? Why or why not?

- Let’s work as a class to come up with some other cognates and false cognates. I’ll write them in the chart.

Figure 8.2. Cognate Strategy: Rainforest Cognate Hunt

Directions:

- Listen and follow along as I read the first sentence in “About the Amazon.”

- What cognate is in the first sentence?

- Now work with a partner to find cognates in the rest of the passage.

- With your partner, complete the chart using the cognates you find in the passage.

About the Amazon

The Amazon rainforest is important. It has a lot of materials, food, and medicine that we use. It is always hot. There are millions of plants and trees and many different animals.

Fostering Word Consciousness

Fostering word consciousness is another part of the four-part program that requires little modification for English learners. Just as with EO students, we want ELs to become aware of the words around them, appreciate the power of words, understand why certain words are used instead of others, and get a sense of the words that could be used in place of those selected by a writer or speaker. The types of instruction that will foster word consciousness are also the same for ELs and EO students: Modeling, Recognizing, and Encouraging Adept Diction; Promoting Wordplay; Providing Rich and Expressive Instruction; Involving Students in Original Investigations; and Teaching Students about Words (Graves & Watts-Taffe, 2008).

Regarding special considerations for English learners, I have only three suggestions: First, remember that fostering word consciousness is very much an affective endeavor; motivation is absolutely crucial. Second, keep the option of letting students use their native language firmly in mind. For example, create a game in which small groups of ELs and EO students work together to identify the cognates in a passage students are reading. Third, remember that some word-consciousness tasks—for example, understanding why an author might have chosen one word over another—are very challenging. ELs are likely to need a lot of support from you with such tasks.

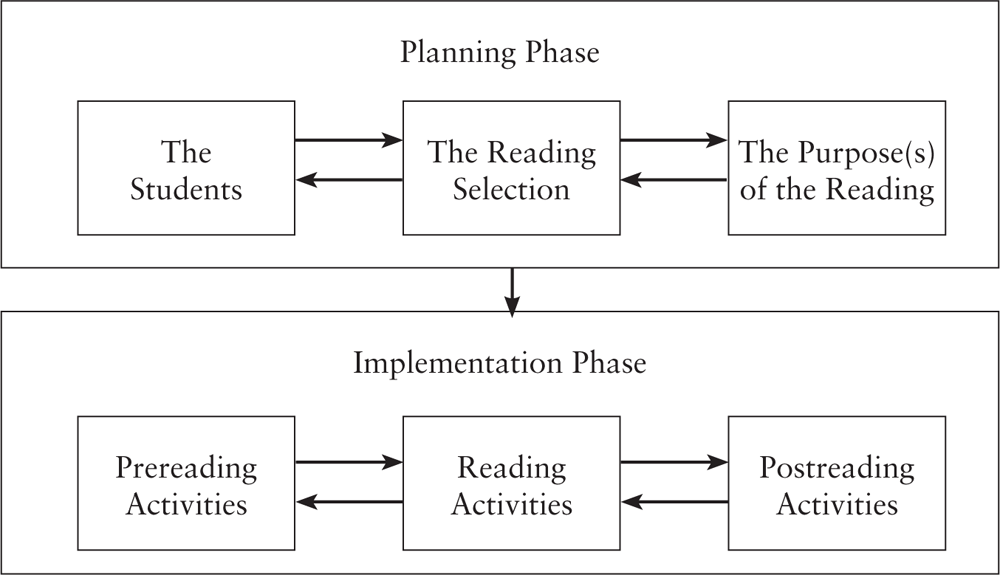

SUPPORTING STUDENTS’ READING WITH SCAFFOLDED READING EXPERIENCES

Over the same time period that I have been concentrating on vocabulary instruction, I have developed and used an approach to supporting students’ reading that I term a Scaffolded Reading Experience, or SRE (Appleman & Graves, 2011; Fitzgerald & Graves, 2004; Graves & Graves, 2003; Graves, Palmer, & Furniss, 1976; Graves, in press). As shown in Figure 8.3, an SRE has two phases—a planning phase and an implementation phase. During the first phase—planning—the teacher considers the students, the selection they are reading, and their purposes for reading. During the second phase—implementation—the teacher selects those prereading, during-reading, and postreading activities that will lead students to a successful reading experience. The SRE framework is appropriate for virtually any combination of students, texts, and purpose or purposes; but the specific pre-, during-, and postreading activities as well as the number of such activities that are employed in any particular situation will differ hugely. In general, with less proficient students, more difficult selections, and more challenging purposes, more scaffolding is needed. Conversely, with more proficient readers, less difficult selections, and less challenging purposes, less scaffolding is needed.

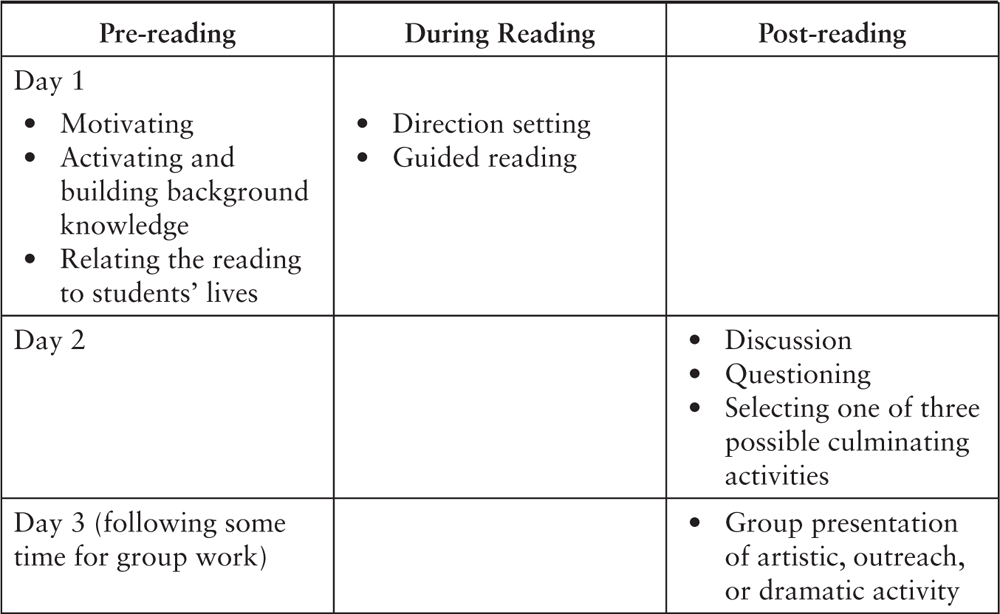

The scaffolded-reading framework is flexible and adaptable because it presents a variety of options—possible pre-, during-, and postreading options—from which you choose those best suited to lead a particular group of students to success with a particular text and a particular goal or set of goals. These options are shown in Figure 8.4.

Figure 8.3. The SRE Framework

Prereading activities prepare students to read the upcoming selection. They can serve a number of functions in helping students engage with and comprehend text. These include piquing students’ interest in the selection, reminding them of things they already know relevant to the selection, and preteaching aspects of the selection that they may find difficult, such as complex concepts and troublesome words. Of course, English learners can and should read some texts without prereading assistance, but when texts are challenging or when you want students to understand them deeply, pre-reading activities can set the stage for a truly productive and rewarding reading experience. Most of the prereading activities shown in Figure 8.4 are self-explanatory, but a few may deserve clarification. The activities include both “Activating Background Knowledge” and “Building Text-Specific Knowledge” because in some cases students already have the requisite knowledge to deal with a passage while in other cases that knowledge needs to be taught. “Preteaching Vocabulary” and “Preteaching Concepts” are distinguished because, as I explained in Chapter 5, teaching words for which students already have concepts is a very different and easier task than teaching words representing new and potentially difficult concepts. To avoid repetition, the two activities specifically designed for ELs (“Using Students’ Native Language” and “Involving ELs’ Communities, Parents, and Siblings”) are listed only among the prereading activities. However, they are equally useful as reading and postreading activities. Finally, the key word in “Suggesting Strategies” is suggesting. While teaching comprehension strategies is an important part of fostering adolescent literacy, SREs are designed to foster learning from text. The SRE approach assumes that students have been taught strategies—both vocabulary strategies such as using word parts and comprehension strategies such as making inferences—elsewhere.

Figure 8.4. Optional Activities in an SRE

Prereading Activities

Relating the Reading to Students’ Lives

Motivating

Activating Background Knowledge

Building Text-Specific Knowledge

Preteaching Vocabulary

Preteaching Concepts

Prequestioning, Predicting, and Direction Setting

Using Students’ Native Language

Involving ELs’ Communities, Parents, and Siblings

Suggesting Strategies

During-Reading Activities

Silent Reading

Reading to Students

Supported Reading

Traditional Study Activities

Student Oral Reading

Modifying the Text

Postreading Activities

Questioning

Discussion

Writing

Drama

Artistic and Nonverbal Activities

Application and Outreach Activities

Reteaching

During-reading activities include both things that students themselves do as they are reading and things that teachers do to assist students as they are reading—students’ reading silently, their taking notes as they read, teachers reading to them, and the like. A few during-reading activities deserve further explanation. “Silent Reading” is deliberately listed first because this is the most frequent mode of reading students will use outside of school and should therefore be the most frequent mode of reading in school. “Supported Reading” refers to activities that focus students’ attention on particular parts of a text as they read it. For example, students might complete a semantic map of key concepts as they read an expository passage. “Modifying the Text” refers to activities such as presenting material on audio- or videotapes, simplifying the text, or having students read only part of it.

Postreading activities provide opportunities for students to synthesize and organize information gleaned from the text so that they can understand and recall important points. They also provide opportunities for students to evaluate an author’s message, his stance in presenting the message, and the quality of the text itself. And they provide opportunities for students to respond to a text in a variety of ways—to reflect on the meaning of the text, to compare differing texts and ideas, to engage in a variety of activities that will refine and extend their understanding of what they learn from the text, and to apply what they have learned to the world beyond the classroom. As before, a few of these postreading activities may profit from further explanation. “Drama” includes any performance, including short plays, skits, pantomimes, and readers’ theater. “Application and Outreach” activities include such things as cooking something after reading a recipe and organizing a drive to collect winter coats after reading an article on people in need of winter clothing.

Having said all this and having listed 23 possible activities in Figure 8.4, I want to stress that I am not suggesting that using more supportive activities is better than using fewer of them or that ELs should always be supported with SREs. ELs should have opportunities to read material without teacher support, particularly without prereading support, or “fronting” as it is sometimes called. I am in full agreement with authorities such as Pearson (2013) and Shanahan (2012), who note that teachers sometimes provide too much support, particularly too much prereading support, but that is not an argument that teachers should provide too little support, particularly for ELs. At the same time, when ELs or EO students cannot competently complete a reading task on their own, they need the support that will lead them to a successful reading experience rather than to failure and frustration.

The SRE described below, modified from Graves and Avery (1997), is an example of a sturdy scaffold that could be used with both ELs and with EO students.

An SRE to Support Close Reading of a Segment from a Compelling Historical Biography

Good historical biography invites us to imagine people, places, and perspectives in times past—to explore individual strengths and frailties, hopes and apprehensions, and dreams and disappointments as they intersect with the broader historical context. It makes that which seems distant both accessible and comprehensible. In closely reading the excerpt from Doris Kearns Goodwin’s No Ordinary Time (1994) discussed in the following section, English learners and English-only students will witness some of the seeds of the Civil Rights Movement, and in doing so have an opportunity to understand the state of civil rights in the United States before World War II, the differing perspectives of the key players in the episode described, and the complexity of the process of social change.

Selection

Doris Kearns Goodwin’s No Ordinary Time is a penetrating and revealing account of the personal and public lives of Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt during World II. The work, which earned Goodwin the Pulitzer Prize in history for 1995, reveals in rich detail the human stories behind the events that are too often presented as a dull parade of facts in high school history texts. One of the many events described by Goodwin is President Roosevelt’s order to end discriminatory hiring practices in the defense industry, perhaps the first precursor to affirmative action in U.S. history. The decision was a difficult and thought-provoking one for Roosevelt. In an eight-page excerpt (pp. 246–253), Goodwin describes the drama surrounding the signing of the executive order Roosevelt issued, Executive Order 8802. The SRE built around this excerpt shows how you might use the SRE approach to develop students’ reading comprehension and historical understanding. Figure 8.5 shows the SRE for this except at a glance.

Students

Supported by the SRE that surrounds it, this selection is appropriate for high school English learners and English-only students with various levels of language proficiency, reading proficiency, and background knowledge.

Objectives

- To understand the status of civil rights in the United States shortly before World War II.

- To recognize the differing perspectives of key players involved in the decision on Executive Order 8802 and the fact that such differing perspectives are present in most political decisions.

- To recognize the challenges of bringing about social change.

Description of Activities for Day 1: Prereading

Motivating, Activating and Building Background Knowledge, and Relating the Reading to Students’ Lives

Figure 8.5. The SRE for No Ordinary Time at a Glance

HELP WANTED

- Boy—Colored; as porter in drug store. Box C311.

- Experienced colored cook, female. Apply Hilltop Cabins.

- Hotel Maids. Bath maids and cleaners. Young married women; white, now unemployed; for full or part-time; experience. Call in person at Stevens Hotel, 725 S. Wabash Avenue.

- After taking some student responses, reveal that the advertisements were published in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch (6/22/1941), the Atlanta Journal & Constitution (6/16/1941), and the Chicago Tribune (6/22/1941); discuss students’ responses and concerns; and ask whether such advertisements could appear in newspapers today.

- Lead a brief discussion of contemporary prejudice and the possibility of such ads today, note that the excerpt students will be reading describes one of the events that accounts for this change. Then, set the scene by explaining the following: The first step towards ending discrimination in hiring was limited to the defense industry. The time is the summer of 1941; although the United States had not entered World War II at this point, the country was providing arms to Britain. Explain further that President Franklin Roosevelt had declared that the United States should become an “arsenal of democracy” for the Allies, thus promoting a massive production of weapons. The growth of the defense industry meant employment for many Americans, but African Americans were often excluded from all but the most menial jobs. African Americans, led by Asa Philip Randolph, were prepared to march in Washington, DC, to protest job discrimination in the defense industry.

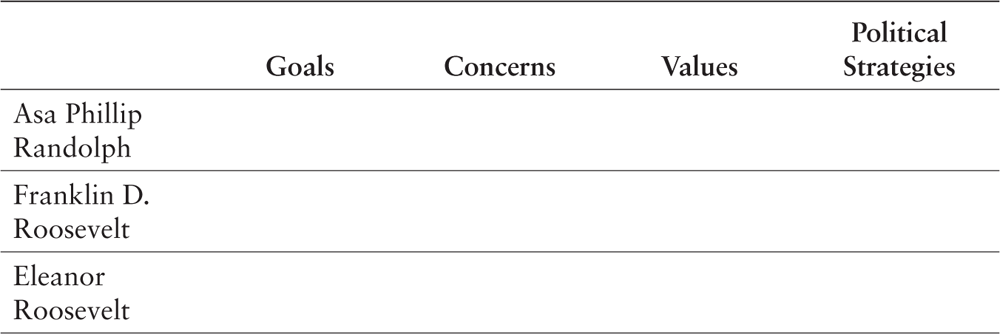

Figure 8.6. Data Matrix for No Ordinary Time

Description of Activities for Day 1: During Reading

Direction Setting and Guided Reading

- Tell students to keep these factors in mind and complete the data matrix shown in Figure 8.6 as they carefully and silently read the selection. (The matrix gives students a purpose for reading, and focuses their attention on three central characters in the drama surrounding the establishment of the Fair Employment Practices Commission: Asa Philip Randolph, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt.)

- Note that students should complete the reading at home if they do not complete it in class.

Description of Activities for Day 2: Postreading

Discussion followed by students choosing between an artistic activity, an outreach activity, or a dramatic activity for a group project.

- Engage students in a discussion based on the data matrix. Questions to explore in the discussion might include: What were the goals of the three individuals and to what degree did these goals conflict? How did their primary concerns and values differ? In what political strategies did each engage? Was Randolph justified in threatening a demonstration when the United States was embroiled in controversy abroad? Be sure that your English learners take part in the discussion, perhaps pairing them with English-only students.

- Ask students to choose one of the following three options for a group project, each of which is designed to help them understand the complexity of social change. Here again you may want to have each group include both ELs and EO students.

- Examine various perspectives on Executive Order 8802 and the social change it was designed to foster by examining editorials and commentaries published in the summer of 1941 in major newspapers and magazines such as the New York Times, Crisis, the Chicago Tribune, the Atlanta Journal and Constitution, Ebony, Time, and Newsweek. Then, arrange the editorials in a display with appropriate analytical comments. Questions you might consider include: To what degree do the writers support Randolph’s action? To what degree do they support Roosevelt’s executive order? What concerns are expressed?

- Interview three or more individuals in their late 60s and 70s about the changes they have seen in the workplace with regard to employment and equal opportunity. Topics to explore include the impact of recent immigrants, English learners, other minorities, and women in workplaces previously reserved for English-only white males and any other aspects of social change you see as pertinent. Write up the results of your interviews in a brief summary paper.

- Research the lives of the three principal figures in this episode—Asa Philip Randolph, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Franklin Roosevelt—each of whom was a leader of remarkable foresight, vision, and integrity. Then create and enact a dramatization of a conversation among the three of them, set either in 1941 or in the present day.

Description of Activities for Day 3: Postreading

Presentations of artistic, outreach, and dramatic activities

- Have groups share and discuss their displays of newspaper clippings and their responses to the questions, present and perhaps elaborate on the summary of their interviews, and present their dramatization of a conversation between Randolph and the two Roosevelts.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

This chapter, “Special Considerations for English Learners,” is the last chapter in the book. It is deliberately the last chapter for a specific reason. Everything said here rests on what I have said about vocabulary instruction for all students throughout this book. To cite Goldenberg (2008, 2013) once more, the vast majority of approaches that are effective for native English speakers are equally effective for English learners, but some accommodations will be needed. This is as true with vocabulary as it is for other aspects of the curriculum. Whether the modification is for teaching more words, teaching more basic words, teaching the use of cognates, or encouraging students to use their native language when appropriate, the recommendation here is to add to what is said throughout the book, not to develop a new approach to vocabulary instruction for ELs. Note also that much of what is described here—the traditional instructional principles, the instructional principles motivated by constructivist and sociocultural theory, the use of Scaffolded Reading Experiences, and even Delpit’s recommendations for working with poor urban children—also applies to working with English-only students. With these modifications for ELs, the comprehensive, research-based, and theory-based vocabulary program described throughout this book can be used to empower ELs and EO students to master the English vocabulary they need to succeed in school and to succeed in the endeavors they undertake once they complete their schooling.