CHAPTER 3

Selecting Vocabulary to Teach

Sometimes when I look at what my students are reading and try to figure out which words to teach and which not to teach, I almost cry.

—Sarah Kingsley, 3rd-Grade Teacher

As the previous chapter demonstrates, we know a great deal about the American English lexicon and about vocabulary instruction. As a result, most of the instructional suggestions I will make throughout this book are straightforward and easily followed. Unfortunately, as Sarah Kingsley’s lament suggests, this is not the case with selecting vocabulary to teach. As I explained in Chapter 2, the best evidence available indicates that achieving students build a vocabulary of something like 50,000 words by the time they graduate from high school, and are thus learning 3,000–4,000 words a year. The most ambitious vocabulary program I am familiar with, Content Rich Vocabulary Instruction (Goldenberg et al., 2013), taught about 450 words over the course of a year, and observations indicate that even the most ambitious teachers typically teach far fewer than that, perhaps 300. Deciding to teach which of the thousands of new words students encounter each year is a major challenge.

In order to decide which words to teach, it is necessary to know both what words students need to know and what words they already know. These are the matters I discuss in the major sections of the chapter—Selecting Vocabulary to Teach from the Texts Students Are Reading, Some Word Lists to Consider, and Assessing Students’ Word Knowledge.

SELECTING VOCABULARY TO TEACH FROM THE TEXTS STUDENTS ARE READING

Although there are some situations in which you may teach words from a specific list, particularly with younger children or English learners, for the most part you are likely to be selecting words to teach from the selections students are reading. In this section of the chapter, I will discuss a version of an approach several colleagues and I developed called Selecting Words from Instructional Text or SWIT (Graves, Baumann et al., 2014). Two beliefs underlie this approach. One is that the principal goal in teaching the vocabulary from a selection students are reading is to support their comprehension of the selection and, particularly with informational text, to support their understanding of a particular subject matter. The other underlying belief is that while the differences between selecting vocabulary from narrative texts and informational text are relatively small, they are important to keep in mind, particularly because with the advent of the Common Core the use of informational texts has become more common in many classrooms.

Figure 3.1. Key Processes of the SWIT Approach

In describing the SWIT approach, I will first discuss four types of words to teach, next consider how many words to teach at one time, then briefly describe four levels or intensities of instruction (levels that will be fully discussed in Chapter 5), and finally give examples of the SWIT procedure with elementary students reading a narrative text, primary-grade students reading an informational text, and high school students reading an informational text. Key processes of the SWIT approach are shown in Figure 3.1.

Types of Words to Teach

As shown in Figure 3.1, the approach deals with teaching four types of words, each of which I describe here.

Essential Words. Essential words are crucial for comprehending the text students are reading. In narrative texts, these words often relate to understanding the central story elements and the characters and their actions. Essential words in narratives often appear just once or a few times in a given text (Hiebert & Cervetti, 2012). In Andrew Clements’ Frindle, for example, typically read in the upper elementary grades, Essential words might include troublemaker, dictionary, and launch. Essential words in informational texts are necessary for understanding the content of the text and key concepts in the content area the text represents. These words are likely to be conceptually complex and are often repeated several times in the text (Hiebert & Cervetti, 2012). In Charles Van Doren’s A History of Knowledge: Past, Present, and Future, for example, which might be read in an AP history class, Essential words might include social equality, absolute tyranny, and totalitarianism. Without understanding the meanings of Essential words, students’ comprehension and learning from text will be impaired significantly.

Widely Useful Words. These words have broad, general utility for students’ reading and writing, and thus have importance beyond the selection students are currently reading. Some of the words I listed as Essential words, for example, dictionary and totalitarianism, would be considered Widely Useful words if they were not essential to understanding the selection students were reading. Widely Useful words are identified not only in relation to the text itself and their prevalence outside of the text, but also in relation to the vocabulary sophistication of the students. For example, Widely Useful words from a text for 10th-grade students would be quite sophisticated, words like inhospitable and perplexing. Widely Useful words from a text for 6th-grade students would likely include some fairly complex words used by advanced language users, words like discord and inevitable. And Widely Useful words from a text for 2nd-grade students would include words not likely to be known by many 2nd graders, but they would be of higher frequency than the Widely Useful words identified for 6th graders, words like accommodate and reconcile.

More Common Words. These are higher frequency words that are not likely to be understood by students who have limited vocabulary knowledge. More Common words must be taught to students whose vocabularies lag significantly behind their age- or grade-level peers because of limited exposure to sophisticated language, fewer world experiences, limited prior knowledge, or the fact that they are learning English as a second language. These students need to acquire More Common words so that they can accelerate their vocabulary growth. These words are not the most common in our language—for example, they are less common than the 220 Dolch Sight Words—but developing language learners need to learn them in order to understand most written texts. Examples for ELs or other students who have mastered basic words but still have limited vocabularies might include words like consider and recent.

Imported Words. These are words that enhance a reader’s understanding, appreciation, or learning from a text but are not included in it. For narrative texts, Imported words may capture key thematic elements (for example, prejudice) or address important character traits (for example, gullible); for informational texts, they may connect to or enhance key concepts presented in the text (for example, democracy, environmentalism). Carefully selected Imported words will help students analyze and extend what they learn from the text.

How Many Words to Teach

Deciding how many words to teach is frequently a challenge because many selections contain more words that at least some students in your class don’t know than you have time to teach. Moreover, there is a limit on how many words you can teach, or at least how many students are willing to learn. Generally, when teaching something the length of a short story or chapter, most teachers suggest teaching no more than 10 words. And most instructional studies (for example, Baumann et al., 2009–2012; Beck, Perfetti, & McKeown, 1982; Carlo et al., 2004; Lesaux et al., 2010; Lesaux et al., 2014 and Snow et al., 2009) taught about 10 words in their units, which typically lasted about a week. Still, because students need to learn about 3,000–4,000 words per year, you would like to teach as many as is reasonable. Thus, while you may not want to teach more than 10 words for a particular selection or segment of a selection, you can increase the number students learn by teaching words in all content areas, not just in reading and language arts; by suggesting words or sets of words students can learn on their own; by teaching word-learning strategies thoroughly and repeatedly encouraging students to use them; by immersing students in rich and varied language experiences; and by fostering students’ word consciousness.

Types or Intensities of Vocabulary Instruction

Because there are typically more words to teach than there is time to teach them, vocabulary instruction should be the least intensive, most efficient form necessary to provide students with the knowledge they need to understand word meanings and comprehend the texts containing the words. Here are four intensities of instruction that are possible: (a) Providing Rich Instruction on specific words whose meanings are complex and essential to comprehending the text, (b) Providing Introductory Instruction for words that have clear-cut definitions or are not essential to comprehending the text, (c) Giving Students Glossaries for words that you do not directly teach, and (d) Suggesting Words for students to learn independently, perhaps using their context, word-part, or dictionary skills.

In summary, the process of selecting the types and numbers of words to teach, as well the nature of the instruction, involves considerable judgment and decision making on the part of teachers. I illustrate this decision-making process and further describe the SWIT approach in the following three sections. The first of these deals with a narrative text and the next two with informational texts.

Using SWIT with an Elementary-Grade Narrative Text

Jacquelyn, a 4th-grade teacher, has her students read a selection each week from their literature anthology and participate in small literature-discussion groups in which they read related texts at their instructional levels. This week, the common selection is an excerpt from the classic Newbery Medal–winning Island of the Blue Dolphins (O’Dell, 1960). This short novel tells the story of Karana, a young Native American girl who was left alone on a beautiful but isolated island off the coast of California for 18 years. Over that period, Karana survived, showed great courage and self-reliance, and found a measure of happiness in her solitary life. In the excerpt that the class will read, Karana attempts to paddle to the mainland but has to turn back when her canoe begins to leak. Jacquelyn uses the SWIT process to identify and teach words from this Island excerpt.

1. Identify Unfamiliar Words

Jacquelyn reads the selection carefully, underlining in pencil those words she believes are likely to be Unfamiliar to a number of her students. She identifies 15 words as potentially Unfamiliar: advice, ancestors, befall, calm, faint, fortune, headland, kelp, lessened, omen, pause, pursued, sandspit, serpent, skirted. She then creates a chart like that shown in Figure 3.2 that lists these words in column 1.

2. Identify the Four Types of Words to Teach

Jacquelyn returns to the chapter and determines which of the 15 words are Essential, Widely Useful, or More Common, and decides if she should add any Imported words, which she lists at the bottom of the chart. In doing so, she tries to think like the 4th graders in her classroom—who have varying levels of vocabulary, reading ability, linguistic facility, and prior knowledge—in order to identify the words that will best facilitate their comprehension of the reading selection and general vocabulary development.

Essential Words. Jacquelyn focuses first on words whose meanings students need to know to understand the selection. She considers central narrative elements and O’Dell’s portrayal of Karana. For example, she determines that the words advice and ancestors, which occur in the following passage, are necessary for students to understand Karana’s cultural heritage and motivation to leave the island:

Figure 3.2. Types of Unfamiliar Words and Types of Instruction for Words from Island of the Blue Dolphins

I remembered how Kimki, before she had gone, had asked the advice of her ancestors who had lived many ages in the past, who had come to the island from that country, and likewise the advice of Zuma, the medicine man who held power over the wind and the seas [italics added]. (pp. 57–58)

In contrast, Jacquelyn decides that students’ comprehension of the chapter would not be impaired if they did not know the word serpent, which O’Dell uses simply to name a constellation Karana saw. From going through the excerpt, Jacquelyn decides that the following five words are Essential: advice, ancestors, fortune, omen, pursued. Jacquelyn places checks ![]() in the Essential words column of her chart.

in the Essential words column of her chart.

Widely Useful Words. Jacquelyn reviews the chart looking for Unfamiliar words that, although not Essential for comprehending the selection, are Widely Useful for students to know for general, long-term reading and writing development. Jacquelyn decides that two words are Widely Useful (befall and faint), and she places checks in the Widely Useful column of the chart.

More Common Words. Jacquelyn next determines which of the remaining words are More Common words that are not likely to be understood by her students who have limited vocabularies, particularly the English learners in her class. Jacquelyn determines that two words fall into this category (pause and calm) and places checks in the More Common column of the chart.

Imported Words. Jacquelyn recognizes that the theme of the Island excerpt revolves around Karana’s determination to overcome the obstacles she faced while attempting to paddle from the Island to the mainland. Therefore, she decides to teach determination, which she writes in the Imported row at the bottom of her SWIT chart.

3. Determine the Optimal Type of Instruction

Having chosen which words to teach, Jacquelyn next determines which of the four forms of instruction described earlier is best suited for each word. She does this by considering (a) how abstract or concrete each word is; (b) which of the four types of words it is, making sure that Essential words are taught in a way that ensures that students learn them well; and (c) if her students can determine the words’ meanings independently.

Applying these criteria, Jacquelyn determines that four words—the Essential words advice, ancestors, and omen from the selection and the Imported word determination—will require Powerful Instruction, and that six words—befall, calm, faint, fortune, pause, and pursued—can be taught using Introductory Instruction. Jacquelyn places an ![]() in the appropriate Type of Instruction column in the table. In all, she will directly teach a total of 10 words. This leaves six words she identified as unfamiliar—headland, kelp, lessened, sandspit, serpent, and skirted. Jacquelyn decides that her 4th graders can learn these words independently and places an

in the appropriate Type of Instruction column in the table. In all, she will directly teach a total of 10 words. This leaves six words she identified as unfamiliar—headland, kelp, lessened, sandspit, serpent, and skirted. Jacquelyn decides that her 4th graders can learn these words independently and places an ![]() in the Handout List column on her chart. Her completed list is shown in Figure 3.2.

in the Handout List column on her chart. Her completed list is shown in Figure 3.2.

4. Implement Vocabulary Instruction

At this point, Jacquelyn provides Powerful Instruction for the four words she has identified as needing it and Introductory Instruction for the six words she has decided can be taught using a less time-consuming approach. She also hands out the list of the remaining six unfamiliar words, telling students to use their context skills, word-part skills, dictionary skills, or each other to be sure they know the words’ meanings.

In addition to initially teaching these words, Jacquelyn plans a variety of review activities. As I have emphasized in previous books (Graves, 2006, 2009; Graves, August, & Mancilla-Martinez, 2013) and will again emphasize in Chapter 5, and as many vocabulary authorities have emphasized, it is essential that students repeatedly see, use, and review all new words (Baumann, Kame’enui, et al., 2003; Blachowicz & Fisher, 2000; Silverman et al., 2014).

Using SWIT with a Primary-Grade Informational Text

Alex is a 3rd-grade teacher who gives particular attention to teaching academic vocabulary (Baumann & Graves, 2010) within content domains. His school uses the Seeds of Science/Roots of Reading program (www.scienceandliteracy.org). Alex is teaching the “Soil Habitats” unit from this program, and students will be reading Earthworms Underground (Beals, 2007). The book begins with an introduction that is followed by six colorfully illustrated short chapters that address how earthworms breathe, move, eat, protect themselves, reproduce, and adapt to their environment. Although Earthworms is a short book with a limited amount of text on each page, like many informational books, it contains a number of conceptually challenging words.

This example of SWIT deals with the first three chapters of Earthworms: “Introduction,” “How Earthworms Breathe,” and “How Earthworms Move.” The sections in this example are parallel to those presented for the narrative excerpt from Island, but emphasize how SWIT is used with informational text.

1. Identify Potentially Unfamiliar Words

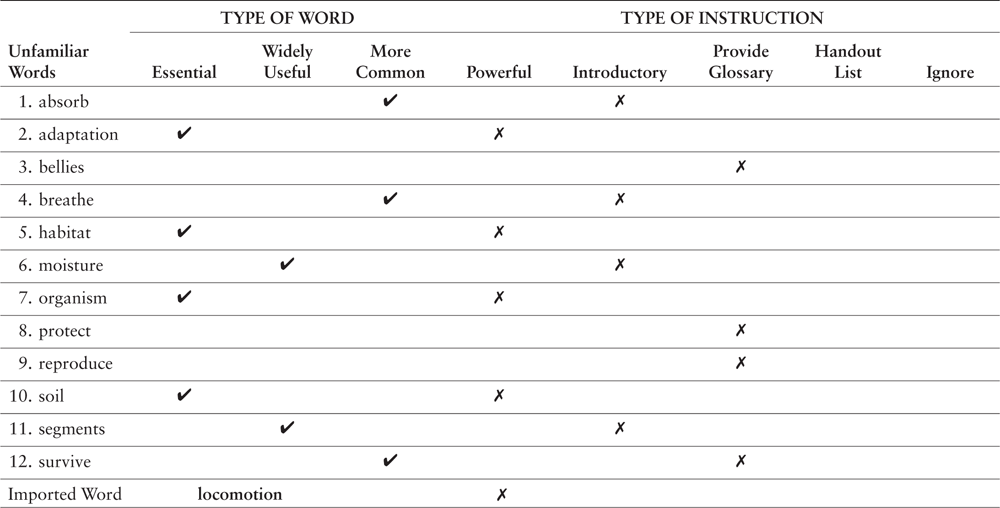

Alex reminds himself that for informational texts he should teach the word meanings students need to understand the content and learn from the text, which in this case are important science concepts related to soil and earthworms. Applying this mindset, he identifies 12 potentially unfamiliar words in the three chapters: absorb, adaptation, bellies, breathe, habitat, moisture, organism, protect, reproduce, soil, segments, and survive. He lists these on the chart shown in Figure 3.3.

2. Identify the Four Types of Words to Teach

Alex returns to the three chapters and analyzes the potentially unfamiliar words to determine which are Essential, Widely Useful, and More Common; if any words should be Imported; and if any of the unfamiliar words do not require instruction.

Essential Words. Alex determines that adaptation, habitat, organism, and soil represent key science concepts that are integral to understanding both this text and crucial concepts of biology and that students will meet repeatedly as they progress through school, so he designates them as Essential words. As you probably recognized, identifying the Essential words in this text is a relatively easy task. It is often the case that Essential words are considerably easier to identify in informational texts than in narratives.

Widely Useful Words. Alex further determines that moisture and segments are Widely Useful words that students will come across not just in the Earthworms text or in science books but in their reading generally.

More Common Words. And he notes that breathe, survive, and absorb are More Common words that many of his students know but that his English learners and other students who struggle with vocabulary may not know.

Imported Words. There is a particularly interesting section of text that explains how earthworms use hairs and segments to move through the ground, so Alex decides to teach the Imported word locomotion.

Alex decides not to teach 4 of the 12 words he identified as Unfamiliar. He notes that protect and reproduce appear only once in these chapters and that there is an entire chapter devoted to each of these words/concepts later in the book, so he decides to wait and teach them then. Alex also knows that soil has been discussed many times in preceding books in the unit, so he eliminates it. Additionally, after rereading the chapters, Alex decides that bellies does not merit class time. Thus, Alex decides to teach 8 of the 12 words he identified as potentially Unfamiliar, along with the Imported word locomotion.

Figure 3.3. Types of Unfamiliar Words and Types of Instruction for Words from Earthworms Underground

3. Determine the Optimal Types of Instruction

As Jacquelyn did with Island, Alex considers the type and nature of the words he will teach and how they are used in the text to determine the type of instruction most appropriate for each. As a result of this analysis, Alex determines that adaptation, habitat, organism, locomotion, and survive will require Powerful Instruction and that absorb, breathe, moisture, and segments can be taught through Introductory Instruction, and places ![]() ’s in the appropriate columns in the table. Although he is not directly teaching 4 of the 12 words he identified as unfamiliar (bellies, protect, reproduce, and survive) he decides to provide students with a glossary for these words, and places an

’s in the appropriate columns in the table. Although he is not directly teaching 4 of the 12 words he identified as unfamiliar (bellies, protect, reproduce, and survive) he decides to provide students with a glossary for these words, and places an ![]() in the Provide Glossary column. Figure 3.3 shows his completed list.

in the Provide Glossary column. Figure 3.3 shows his completed list.

4. Implement Vocabulary Instruction

Having completed his assessment of which words to teach and how to teach them, Alex now engages students in Powerful Instruction or Introductory Instruction as appropriate, and hands out the glossary with the words he does not directly teach. As did Jacquelyn, he realizes that the initial instruction is just the first step in a series of experiences with these words that will lead to students’ thoroughly learning them and using them over time, and therefore provides opportunities for students to see, use, and review the words.

Using SWIT with a Secondary-School Informational Text

Margaret has been teaching high school history for 15 years, and she absolutely loves the job. For the past 3 years, she has taught 11th-grade American history, and this is both her favorite grade level and her favorite history topic. Her school has a required American history textbook and she uses that much of the time, but she often supplements the textbook with both primary source documents and selections she finds particularly insightful and well written. One of her favorite books and one that she believes has a tremendous amount to say to today’s youth is Doris Kearns Goodwin’s No Ordinary Time. Subtitled Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt: The Home Front in World War II, this Pulitzer Prize–winning political and social history and biography reveals the inner workings of the White House and the lives of the President and First Lady from the years leading up to World War II to shortly after Franklin’s death.

In the scenario described here, the class is reading an eight-page passage (pp. 246–253) about events surrounding the signing of Executive Order 8801, which outlawed discriminatory hiring practices in the defense industry. While the vocabulary Goodwin uses in this passage is not extremely difficult, this is a book written for adults and some of the wording will certainly challenge some 11th graders.

1. Identify Potentially Unfamiliar Words

As Margaret begins to examine the vocabulary in the section, she realizes that some of the terms she wants to teach will be ones that students have some familiarity with, but she wants to be sure students thoroughly understand them. With this in mind she identifies 19 potentially unfamiliar words: abolish, articulate, astronomical, chloroform for the masses, converge, convictions, decorous, discrimination, Emancipation Proclamation, equitable, Executive Order, fervent, flagrant, fundamental, impasse, phenomenal, raconteur, substance, and vehemently. She lists these on the chart shown in Figure 3.4.

2. Identify the Four Types of Words to Teach

Next, Margaret identifies the Unfamiliar words as Essential, Widely Useful, and More Common; decides whether to add any Imported words; and decides if any of the unfamiliar words do not require instruction. Clearly, as she begins the task of word selection, she realizes she cannot teach all of these words.

Essential Words. Margaret decides that deeply understanding discrimination, equitable, Executive Order, and Emancipation Proclamation is crucial to understanding and appreciating the importance of this passage.

Widely Useful Words. Margaret further determines that fundamental, articulate, vehemently, and converge are Widely Useful words that students will come across in their reading both inside and outside of class.

More Common Words. And she notes that abolish and convictions are More Common words that some of her English learners and students who struggle with vocabulary may not know.

Imported Words. Since she has already identified 10 words to teach and since she still has 9 words on her list of Unfamiliar words that she is not directly teaching, Margaret decides not to add any Imported words.

As I just noted, Margaret decided not to teach 9 of the 20 words she identified as Unfamiliar. Her principal reason for doing so is simply that she thinks 10 words are as many as she has time to directly teach for this selection. Moreover, most of her 11th graders are capable of learning words on their own.

3. Determine the Optimal Types of Instruction

Because she wants students to thoroughly understand all four of the Essential words she identifies—discrimination, Executive Order, equitable, and Emancipation Proclamation—Margaret will use Powerful Instruction with all of these. She will also use Powerful Instruction with fundamental, because she wants students to thoroughly consider what human rights are fundamental. She will use Introductory Instruction with the other three Widely Used words and the More Common words—articulate, vehemently, converge, abolish, and convictions. And because her 11th graders are quite capable of learning vocabulary on their own, she will ignore the other words. Having made these decisions, she places ![]() ’s in the appropriate columns on her chart. Figure 3.4 shows her complete chart.

’s in the appropriate columns on her chart. Figure 3.4 shows her complete chart.

Figure 3.4. Types of Unfamiliar Words and Types of Instruction for Words from No Ordinary Time

4. Implement Vocabulary Instruction

Having completed the task of determining which words to teach and how to teach them, Margaret engages students in Powerful Instruction or Introductory Instruction as appropriate, and she encourages students to be on the lookout for words they do not know and use whatever approaches they typically use to learn these words. She also plans and later executes review of all of the words, and encourages students to review on their own.

As I have said, and as Sarah Kingsley’s lament that opened the chapter indicates, selecting vocabulary to teach is a demanding task. There is no way around that, but judicious use of word lists, the next topic i consider, can make it somewhat less demanding.

SOME WORD LISTS TO CONSIDER

As I said at the beginning of the chapter, I believe that in the majority of situations, you will choose words to teach from the selections students are reading or listening to, rather than by considering lists of words to teach. Nevertheless, word lists can be useful as an adjunct to your professional judgment, and there are some situations in which you may decide to teach words from a specific list. Moreover, the Common Core specifically calls for teaching “general academic and domain specific” vocabulary, and several of these lists are specifically designed to identify such vocabulary. Here are brief descriptions of several lists, ordered from those that are primarily useful with younger students to those that are primarily useful with older students. Each description ends with a suggestion for how the list might be used.

The First 4,000 Words

The First 4,000 Words (Graves, Sales, & Ruda, 2008) is a list of the most frequent 3,600 English word families (where a family is defined as the base word and its common inflected forms, as in want, wants, wanted, and wanting) ordered by frequency. It is available at www.thefirst4000words.com. This list was constructed by Graves et al. (2008) from work completed by Hiebert (2005) and Zeno et al. (1995). These 3,600 word families make up 80–90% of the words found in a typical text; if students cannot read them, they will repeatedly stumble when reading all but the most basic texts. Some words from the beginning of the list, the middle, and the end are shown in Figure 3.5.

Figure 3.5. Sample Words from The First 4,000 Words

Most English-only students arrive at 1st grade with most of the words on The First 4,000 Words list already part of their listening vocabularies, and gradually incorporate them into their reading vocabularies by about the 4th grade through a combination of learning them as sight words and using their decoding skills. Thus, the majority of English-only (EO) students do not need to be taught the meanings of these basic words. However, some students—English learners with very small English vocabularies and children who have been exposed to relatively little oral language during the preschool years—do need to learn the words on this list. I would use this list to ensure that newcomers and other students with very small vocabularies know the most common words so that they are not repeatedly stumbling as they read. In Chapter 4, I describe The First 4,000 Words program, an individualized, web-based program that some colleagues and I (Fehr et al., 2011; Graves et al., 2008; Sales & Graves, 2009b) designed to teach these words.

The Vocabulary of Core Reading Programs

The Vocabulary of Core Reading Programs (Graves, Elmore, et al., 2014) is based on a frequency count of the vocabulary in the grade 1–6 books of four current best-selling core reading programs and contains about 26,000 word families. This work is part of an ongoing project titled the Landscape of American English that a group of colleagues and I are currently working on (Graves, Elmore, Fitzgerald, & Stenner, 2015). The work is available in a number of versions, including grade-level lists, and can be obtained by going to https://metametricsinc.com/american-school-english/. All versions include the frequency of each word or family listed. Samples of high-, medium-, and low-frequency words from the 1st-grade list and from the complete list are shown in Figure 3.6. The versions for each grade level are probably the most useful for teachers. I recommend using the appropriate grade-level list in addition to other criteria in selecting reading vocabulary to teach. That is, I recommend following the SWIT guidelines, using the list as an aid to your professional judgment in deciding which words to teach. Importantly, the list is also useful in deciding which words not to teach. About 40% of the words appear only once and about 50% only twice. If a word is infrequent, there are probably other words more deserving of instructional time.

Figure 3.6. Sample Words from the Vocabulary of Core Reading Programs List

The Vocabulary of Elementary Level Content-Area Texts

The Vocabulary of Elementary Level Content-Area Texts (Fitzgerald, Elmore, & Stenner, 2015) is another part of the Landscape of American English project and shares most characteristics of the core reading program list. It is based on a frequency count of the vocabulary in the grade 1–5 books of four current best-selling math, science, and social studies series, and contains about 30,000 word families. Various versions of this work are available by going to https://metametricsinc.com/american-school-english/. Samples of high-, medium-, and low- frequency words from the math series and the science series are shown in Figure 3.7. I recommend using the appropriate content-area list in addition to other criteria in selecting vocabulary to teach. That is, I recommend following the SWIT guidelines, using the list as an aid to your professional judgment in deciding which words to teach. As is the case with the vocabulary in core reading programs, many of the words in these content texts appear very infrequently and so this list too is useful for identifying words that are not deserving of instructional time.

A List of Content-Area Words

Marzano (2004) has created a list of approximately 8,000 words and phrases taken from standards’ documents and representing 11 subject areas (math, science, language arts, history, geography, civics, economics, health, physical education, the arts, and technology). The terms in each of these areas are further classified into four grade-level ranges (K–2, 3–5, 6–8, and 9–12). Thus, in all Marzano presents 44 different lists (K–2 math, K–2 science, K–2 language arts, etc.). Typical words from four of these lists are shown in Figure 3.8. These lists identify the sorts of domain-specific academic vocabulary emphasized in the Common Core, and can be used along with your professional judgment when choosing subject-matter vocabulary to teach. If, for example, there is a good deal of overlap between the content words you have selected to teach using these other sources and the words on Marzano’s list, then you have some validation for teaching the words you have selected. If, on the other hand, there is little overlap between the content words you have selected to teach and the words on Marzano’s list, then the words you have selected and the procedures you used in selecting them probably deserve a second look.

Figure 3.7. Sample Words from the Vocabulary of Elementary Level Content-Area Texts

Figure 3.8. Sample Terms from Marzano’s List of Content-Area Words

The Middle School Vocabulary Lists

The Middle School Vocabulary Lists (Greene & Coxhead, 2015) are somewhat similar to Marzano’s list. They were derived from a large sample of middle school textbooks, and consist of separate lists for English grammar and writing, health, math, science, and social studies/history. Each list contains the 300–400 most frequent word families in that subject. The lists are ordered by frequency, although no frequencies are provided. The first 20 families from the English grammar and writing list are shown in Figure 3.9. Like Marzano’s list, these lists contain the sorts of academic vocabulary emphasized in the Common Core, and I would use these lists in the same way I would use Marzano’s list.

The Academic Word List

The Academic Word List (Coxhead, 2000) is a list of 570 word families of general academic vocabulary. Coxhead developed the AWL by surveying textbooks, professional journals, and other academic writing. She included materials that represented 28 academic domains (for example, history, psychology, economics, biology, mathematics). The words are not among the approximately 2,000 frequent English words on the General Service List (West, 1936/1953), are not content-specific words, and do not appear frequently in narrative texts, but they do appear frequently in expository texts across subjects like history, biology, and psychology. Although the list was constructed using college-level texts, it is divided into 10 sublists, with the first sublist containing the more frequent words and therefore the words most likely to be appropriate for younger students. In fact, one recent vocabulary program for 6th graders (Lesaux et al., 2010; Lesaux et al., 2014) and one for 6th–8th graders (Snow et al., 2009) focused exclusively on words from this list. Examples from the first sublist are analyze, concept, estimate, occur, and respond. Even though the list was constructed using college-level texts, it may be useful to use along with your professional judgment in choosing general academic vocabulary to teach to middle and secondary students. As is the case with using Marzano’s list, good overlap between the words you have selected using your personal judgment or other sources and the AWL validates your choices, whereas little overlap may suggest you reconsider your tentative word selection and your procedures in selecting them. The AWL is available at www.victoria.ac.nz/lals/resources/academicwordlist, and some words from the list are shown in Figure 3.10.

Figure 3.9. The 20 Most Frequent Word Families from the English Grammar and Writing Section of the Middle School Vocabulary Lists

Figure 3.10. Sample Words from The Academic Word List

The Academic Vocabulary List

I described The Academic Word List because it is widely known and used. However, Gardner and Davies (2013) recently completed the Academic Vocabulary List, another list of general academic vocabulary that was designed as a replacement for The Academic Word List. Gardner and Davies’s list has several advantages over Coxhead’s, particularly for use in the United States; and it seems likely that it will become increasingly used. Among the advantages that the authors see in their list as compared to The Academic Word List are that it (1) is based on a much larger, newer, and more representative list of words, (2) is based solely on texts published in the United States rather than largely on texts published in New Zealand, (3) was constructed using lemmas (words with a common stem, related by inflection only, and coming from the same part of speech) rather than word families (stem plus all inflections and derivations containing the stem), and (4) does not exclude words from the General Service List. As is the case with The Academic Word List, although this is not an ideal list for use with secondary students, it may be useful along with your professional judgment or other sources in choosing general academic vocabulary to teach to secondary students, and I would use it in the same way I would use The Academic Word List. The Academic Vocabulary List is available in several formats at www.academicvocabulary.info/, and some sample words are shown in Figure 3.11.

Figure 3.11. Sample Words from the Academic Vocabulary List

ASSESSING STUDENTS’ WORD KNOWLEDGE

If you are going to spend your time and your students’ time teaching individual words, you want to know which words students know and which words they don’t, and you want to know whether or not students have learned and retained the words you have taught. That way, you don’t spend time “teaching” students words they already know or failing to teach words that they don’t know, and you find out whether your instruction is successful. Of course, with tens of thousands of words to learn, you can’t check students’ knowledge of each word before deciding whether to teach it, and you probably can’t check students’ knowledge of all the words you teach. But you can get some idea of the size of each of your student’s vocabularies and the words they have learned with various types of assessments. Here I discuss three types: commercially produced tests, teacher-made tests, and student self-assessments.

Commercially Produced Tests

Commercially produced tests have the huge advantage of already being available. You don’t have to create them yourself. Many of them also have the advantage of being norm referenced. That is, you can compare your students’ scores on the tests with the scores of large groups of students on whom the tests have been normed, and ask how the scores of the students in your class or any particular student in your class compares with those of other students in the same grade. On the other hand, as Pearson, Hiebert, and Kamil (2007) have pointed out, most commercially produced tests tell you nothing about students’ knowledge of any particular set of words. That is, they tell you that Student A knows more words or fewer words than Student B or that Student A knows more words or fewer words than the average student at her grade level. But they tell you nothing about which particular words or set of words your students do or don’t know. Here, I briefly describe four such tests.

Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test. The Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT; Dunn & Dunn, 2007) is an individualized test of listening vocabulary. Although testing a single student takes only about 15 minutes, giving the test to an entire class is, of course, time consuming. The PPVT is something you would probably only use if you have some students you suspect of having very small vocabularies, and it is quite likely that a specialist rather than a classroom teacher would administer the test. The PPVT can be used with a range of ages; so while you are probably most likely to use it with primary-grade children, you could also use it with older students. Like all the tests described here, the PPVT needs to be interpreted with caution when used with English learners. The test is a series of sets of four pictures representing words of increasing difficulty. In giving the test, you sit with a student, say a word, and ask her to point to the picture represented by the word. Norms for the latest version of the test were developed in 2006–2007 and appear to appropriately represent today’s U.S. population. An item similar to those used in the PPVT is shown in Figure 3.12. The word being tested is grapes.

Figure 3.12. Sample Item Similar to Those Used in the PPVT

Listening Vocabulary Test. The Listening Vocabulary Test (Sales & Graves, 2009a) is a 40-item, group-administered test that assesses students’ knowledge of the approximately 4,000 most frequent English words, The First 4,000 Words list, which I have previously described. It has both disadvantages and advantages compared to the PPVT. The major disadvantage is that it provides no norms; thus you cannot compare your students’ performance to that of students in a norm group. Its major advantages are that it is group administered, making it much more feasible for a classroom teacher to use, and it is referenced to a specific group of words, the approximately 4,000 most frequent English words. As I have noted, these approximately 4,000 words make up 80–90% of the running words students will encounter in their reading. Thus, knowing these words is vital to successful reading. The test is intended for elementary students who are not likely to have the majority of the most frequent 4,000 English words in their oral vocabularies. In giving the test, the administrator says a word and children choose the best response from a set four pictures. The test takes about 30 minutes to give, but because it is given to the class as a whole, it is not nearly as time consuming as individually administered assessments. An item from the test is shown in Figure 3.13. The word being tested is different.

Reading Vocabulary Test. The Reading Vocabulary Test (Sales & Graves, 2009c) tests students’ ability to read the same words that are on the Listening Vocabulary Test. It is designed for elementary students who are not likely to have the majority of the 4,000 most frequent words in their reading vocabularies. In taking the test, students view a single picture representing each word and select a word from one of four written alternatives. An item from this test is shown in Figure 3.14. The word being tested is help.

Figure 3.13. Sample Listening Vocabulary Test Item for Different

Figure 3.14. Sample Reading Vocabulary Test Item for Help

The Gates-MacGinitie Reading Tests. The Gates-MacGinitie Reading Tests (MacGinitie, MacGinitie, Maria, Dreyer, & Hughes, 2000) are widely used and typical of many commercially produced tests. The Gates-MacGinitie tests are group-administered, norm-referenced reading tests that come in a variety of levels from prereading through adult. The earliest levels do not include a test of reading vocabulary, but the tests for grade 2 and higher do, and the vocabulary test can be given by itself. Norms for the latest version of the test were developed in 2006 and appear to appropriately represent today’s U.S. population. An item similar to those used in the Gates-MacGinitie Reading Tests is shown in Figure 3.15. The test is easy to administer to classroom-size groups, and giving it takes about 20 minutes.

Teacher-Made Tests

Unlike most commercially produced tests, teacher-made tests can be referenced to a particular set of words. You might, for example, construct a test on the potentially difficult words in an upcoming unit, an upcoming reading selection, or the glossary of a textbook you are using. This makes it possible to draw conclusions such as “It looks like about a third of my students are really going to be challenged by the vocabulary in our unit on the Constitution,” “Kimberly cannot read any of the words I identified as potentially difficult in Will Hobbs’ Crossing the Wire,” or “It looks like my class knows about half of the words that are glossed in our health text.” Of course, teacher-made tests can also be used to test students’ knowledge of words you have taught, to check the effectiveness of your instruction. Here, I describe two forms of teacher-made tests, one for testing oral vocabulary and primarily intended for use with younger children and the other for testing reading vocabulary in students of various ages.

Figure 3.15. Sample Item Similar to Those Used in the Gates-MacGinitie Reading Tests

It was an interesting era.

- kind of food

- type of sport

- period of time

- way of talking

Yes/No Tests. Several forms of a yes/no test have been used to test oral vocabulary in young children. The form described here is taken from Silverman et al. (2014). Using this approach, you ask children questions about words to which they respond yes or no. More specifically, you ask four questions on the same word. For example, in testing the word habitat, you might ask:

- Does habitat mean a place where an animal lives?

- Does habitat mean food that an animal eats?

- Is a rainforest a habitat?

- Is an elephant a habitat? (Silverman et al., 2014)

You score and interpret the test by giving one point for each correct response, and assume that the more points children get on a word, the more likely it is that they know the word and are not just guessing.

Multiple-Choice Tests. Multiple-choice tests can be useful in testing reading vocabulary in students of various ages, although constructing multiple-choice tests does require some time. In constructing multiple-choice tests, I suggest providing three options rather than the more usual four options because three-option items are considerably easier and less time consuming to construct. Here are some guidelines:

- Keep things simple and uncomplicated for yourself and your students. For example, make the question stem simply the word you are testing.

- Make the correct answer a clear and concise definition, doing everything you can to keep the words in the answer simpler than the word you are testing.

- Make the two distractors distinctly wrong. This is not the place for testing fine distinctions in meaning.

- While the distractors should be distinctly wrong, they should not be obviously wrong. All three alternatives should be about the same length and use the same syntax. Avoid alternatives that are silly or otherwise blatantly incorrect.

Figure 3.16. Sample Teacher-Made Multiple-Choice Items

Grade 3

ache

- a type of soup

- a steady pain

- a small boat

Grade 6

fanatic

- very unreasonable

- most acceptable

- sometimes unhealthy

Grade 10

defamation

- changing the direction of a moving object

- damaging the reputation of someone or something

- purchasing more goods than you can use

A sample item you might use with 3rd graders, an item you might use with 6th graders, and an item you might use with 10th graders are shown in Figure 3.16.

In addition to testing students on their word knowledge, you can use a multiple-choice test to check your knowledge of which words your students do and do not know. By constructing and giving a test with five words you are pretty sure most of your students know, five words you are pretty sure most of them don’t know, and five you are uncertain about, you can begin to get an idea of how much you know about your students’ vocabularies. If their performance squares with your predictions, great. If it does not, you need to work at learning more about their word knowledge. Only when you have a good sense of the words your students do and don’t know can you effectively choose words to teach.

Student Self-Assessments

When time constraints make it impossible to create an actual test, there is a satisfactory alternative. Simply create, duplicate, and hand out a list of words. Give students the list, and explain what they are to do and the purpose of the exercise. What they are to do is put a check mark beside the words they know. The purpose of their doing so—and it’s really important to stress this with your students—is for them to indicate whether they know each word so that you can teach those they don’t know. It is not to give them a grade or in any way penalize them for not knowing some of the words. My experience has been that students are quite adept and truthful in identifying words they don’t know in this way. Of course, asking students whether or not they know a set of words is something you can do much more frequently than giving a test.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

At the beginning of the chapter, I noted that selecting vocabulary to teach is not an easy task. Whether or not you agreed then, I strongly suspect you agree now. It involves identifying the small number of words that you have the time to teach from a very large number of words you might teach. And that in turn involves knowing what words your students do and don’t know, knowing what words are important in the individual selections your students read, and knowing what words are important and students will need to deal with in all the materials used in your class and in the materials they will read outside of your class.

Clearly, selecting what words to teach is a significant task. But it is a doable one. Once you become proficient with the SWIT approach, the task becomes much easier. For example, while you may want to use a chart such as those used by Jacquelyn, Alex, and Margaret to identify the types of unfamiliar words you are dealing with and what types of instruction to provide the first few times you use the SWIT procedure, with practice you will internalize the procedure and not need the chart. Also, the more vocabulary assessments you give—both formal assessments and simply asking your students which words they do and do not know—the better your intuitions on which words need instruction and which words do not will become.

Additionally, the lists that I have described and given examples of can be helpful along with your professional judgment in identifying words worthy (and unworthy) of instructional time. As I said before, except for ensuring that students with very small vocabularies know The First 4,000 Words, I am not suggesting teaching these lists. I am also not suggesting that you consult these lists any time you are trying to identify words to teach. What I am suggesting is that you get copies of the appropriate lists, and through a process of perusing them, considering the words that appear in the material your students are reading, and checking with your students on which words they do and do not know, you gradually hone your perceptions of which words to teach.

Finally, I want to bring up something I did not bring up earlier in the chapter. This is the importance of getting students in the habit of considering the vocabulary in the material they are reading and themselves deciding which words they need your help with, which words they can learn using context or word parts, and which words they can learn using the dictionary or each other as resources. Working together, you and your students can make informed choices about which words to study, and this shared experience will benefit both you and your students in the short run and your students once they leave your class and school and need to learn words independently.