6

6

From Shanty to Lace Curtains

A charming cottage garden in the front yard of the restored Mary Hafford House overflows with plants familiar from the Emerald Isle.

TERRY MOLTER

Many immigrants arriving in America received a less-than-welcoming reception, but few faced widespread discrimination to the extent the Irish did. Yankees resented them in part due to the long history of mutual hostility between the Irish and the English. In addition, the majority of the Irish proudly and openly supported the Roman Catholic Church, which invited further criticism. Some described them as brutish, quarrelsome, unkempt, and even dirty, and they carried a reputation for drinking too much whiskey. Yet their gifts for storytelling and music brought admiration.

The Irish came to America seeking employment, a place to live, and enough food to sustain themselves. They arrived with limited skills, most having labored on small farms in their homeland. Willing to work hard, they readily accepted employment that required arduous manual labor, including jobs in mines, in the logging industry, and in construction, working on roads, railroads, and canals.

Some Irishmen toiled in Wisconsin’s lead mines as early as the 1820s and 1830s. But with the onslaught of the Great Potato Famine in Ireland after the mid-1840s, their fellow countrymen began arriving in massive numbers. A destructive fungal disease swept through the Emerald Isle’s potato crops, wreaking havoc on the country’s main food source. This devastation, combined with years of social and political oppression and continuing economic struggles, led to massive emigration. Between 1845 and 1854, approximately 1.5 million people left Ireland, and the vast majority journeyed to America.1

By midcentury, twenty-one thousand people of Irish birth lived in Wisconsin; by 1860 that number had more than doubled to fifty thousand.2 Most gravitated to cities, preferably near a Catholic church, close to other family members, and where job opportunities existed. Some went on to purchase and farm their own land, which had been just a dream in the Old Country. They brought optimism that with good old-fashioned hard work and a bit of Irish luck a better life could be obtained and they could exert at least some control over their lives.

A woman willing to wash laundry for others during the nineteenth century could earn extra income to support her family.

NANCY L. KLEMP

The story of the Irish is also one of strong women and their determination to sustain and help improve the lives of their family members. More women came to America from Ireland than from any other European nation. Many arrived unmarried and in search of work. Just as the men did, the Irish women experienced discrimination and accepted jobs others might avoid. Many became domestic servants, while others took positions in factories and textile mills or worked on farms. Money earned and sent back to the homeland frequently paved the way for other family members to come to America.

Married women also found ways to earn extra income and contribute to the family’s finances. On the farm they sold poultry and dairy products. Women with children invariably chose to work at home and took in mending, laundry, and piecework or even housed boarders. These assertive and resourceful women viewed themselves as fairly self-sufficient, which proved especially beneficial to the unfortunate many who became widows due to the dangerous work their husbands pursued. Mother represented the center and the strength of the Irish immigrant family. The affection between parents and their children, and among siblings, strengthened through immigration. Kinship was key to Irish existence.

Little documentation exists about gardens of the nineteenth-century Irish in Wisconsin. Gardens of their homeland and those of densely Irish settlements in the eastern United States offer some insight into traditional gardening styles and favorite plants.

In Ireland the stately country homes of the wealthy showcased extensive gardens, often enclosed and protected by stone walls. These gardens of the elite, with their formal paths, decorative flower and shrub borders, and espaliered fruit trees,3 hardly bore a resemblance to the rural countryside peasant farms and gardens.

Eighty percent of all farms in Ireland measured fewer than fifteen acres during the first half of the nineteenth century.4 A tenant farmer planted three-quarters of his land to be harvested for the landlord in exchange for the opportunity to use the remaining quarter for his own family’s needs. The vast majority of that land was planted to potatoes, which were inexpensive and easy to grow and store, generally producing large quantities of nutritious food for people and livestock.5 When the crop did well, it was not unusual for a working man to eat fourteen pounds of potatoes at a meal.6 An average consumption of eight pounds of that popular vegetable per day for each family member was well documented.7 A small family of two parents and three children could easily consume a bushel of potatoes each day, and the Irish valued large families: the entire family contributed labor to the farm, so more hands meant more help. Also, Irish superstition equated large families with success in the crops and livestock.8

Once the previous year’s harvest had been depleted, meal options looked lean. Milk, occasionally fish, and even more rarely meat supplemented the nineteenth-century Irish diet that relied so heavily on the potato. It seems that the Irish never grew a wide variety of vegetables. E. Estyn Evans noted in Irish Folk Ways that by the time the plow replaced cultivation by hand and spade “a vegetable garden [was] a rare thing, at best a tiny plot left to the care of the woman.”9 Cabbage, leeks, onions, turnips or rutabagas, cresses, and edible seaweed, as well as oats and wheat for bread received occasional mention in his extensive study, but the preponderance of the potato in the diet cannot be overemphasized.

In the eastern United States, more than two thousand Irish immigrants settled in northern Delaware in the nineteenth century to work in the E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company’s black powder industry. Families there maintained “very small” kitchen gardens, averaging thirty to forty feet wide by forty to sixty feet long. Rectangular beds predominated, with a straight central path through the garden and two-foot paths around the edges. Men turned and fertilized the garden plots; women and children planted and maintained them. As in their homeland, the entire family worked together at harvest time. Inexpensive and easily grown and stored vegetables dominated the gardens. Several rows—and sometimes as much as half the garden—of potatoes ensured a supply of the familiar staple. Cabbage, too, earned space in the garden. Other vegetables grew in lesser quantities, as the Irish immigrants eagerly adopted new foods, preferably those that could be boiled for mealtime.10 In the Emerald Isle, built-in ovens had been rare. The long-standing Irish tradition of boiling vegetables, soups, stews, and porridges continued to be the most popular method of food preparation in their newly adopted country.

Sir Walter Raleigh receives credit for introducing both potatoes and cabbage to Ireland in the 1580s.1 At that time suspected to be poisonous to people, both vegetables originally found use as animal feed. More than one hundred years later they were deemed safe for human consumption but were considered fit only as food for peasants. Potatoes, of course, became the primary food of Ireland.

Even before it met the dinner kettle, cabbage had been lauded for its healing properties. Medieval textbooks recommended a poultice of thoroughly macerated fresh green cabbage leaves to treat burns, gout, sore legs, ulcers, and wounds.2 By the end of the eighteenth century the Irish appreciated cabbage for its value as high-yielding animal fodder as well as its versatility at the family dinner table.

Large, firm heads of cabbage—such as this Late Flat Dutch variety—store well, ensuring a long season of usage.

NANCY L. KLEMP

Rutabagas and turnips, inexpensive and easily grown, were also adapted to uses beyond the kitchen. With the top cut off and the bottom trimmed to sit flat, a hole was carved into the top of the vegetable so a candle could be seated into the opening. Traditionally these homemade candleholders were lit and placed in the front windows of the house at Christmastime to provide an especially warm glow.3 At Halloween, these same vegetables were hollowed out and carved to resemble faces. Placed inside and lit, candles accentuated the carvings. This Irish tradition continued in America and grew in popularity when the New World pumpkin became the vegetable of choice to be carved into jack-o’-lanterns.

The jack-o’-lantern blended the Irish tradition of hollowing and carving a turnip or rutabaga with the New World pumpkin to create an American symbol of Halloween. This image appeared in the September 1875 issue of The Ladies’ Floral Cabinet and Pictorial Home Companion.

NOTES

1. Margaret M. Mulrooney, Black Powder, White Lace: The du Pont Irish and Cultural Identity in Nineteenth-Century America (Hanover, NH, and London: University Press of New England, 2002), 175.

2. Patrick Logan, Irish Country Cures (New York: Sterling Publishing Co. Inc., 1994), 105, 110.

3. Christmas in Ireland (Chicago: World Book Inc., 1985), 65.

The monotonous diet of the Irish country folk revolved around potatoes—rows and rows of potatoes.

GERALD H. EMMERICH JR.

Irish Cobbler potatoes

NANCY L. KLEMP

A typical nineteenth-century Irish-American home in Wisconsin would likely have included a small vegetable garden—rectangular with a straight path cut through the center—in the backyard, out of view to the casual visitor. Potatoes would have dominated the space, accompanied by smaller beds of cabbage, leeks, onions, rutabagas, turnips, and parsley. The Irish immigrants were observant and quick to adopt new plants they met, but they did not abandon those associated with their ethnic heritage.

The Irish viewed America as a true land of opportunity, a country in which they could gain respectability and rise in society. Putting the image of dirty, disorderly, uncomfortable shanty homes behind them, men became successful breadwinners, and women sought to create genteel home environments. Decorative objects and furnishings appropriate for a parlor dressed up the front room of the house. That front room might combine the functions of the kitchen and dining room as well as the parlor, and the decorative pieces might be homemade or secondhand rather than newly store-bought finery, but they were indicative of the Irish intention to acculturate into American society. Attractive plant stands showcased charming potted plants. Linen tablecloths and white lace curtains, in particular, symbolized the refinement and respectability they sought. By displaying Irish linen and Irish lace, the quickly adapting immigrants identified pride and loyalty to their Irish heritage as well as to America.

Mary Ward Hafford, her husband, Matthew, and their young son immigrated to America from Ireland in 1864. By the time they settled in the Village of Hubbleton, Jefferson County, in 1867, they had two additional children. Matthew passed away suddenly in 1868, and Mary found herself needing to earn support for her family.11 Exhibiting the strength and spirit of strong Irish women before her, she became a washerwoman, which enabled her to care for her children at home while doing laundry for others. Through hard work she prospered, and although she never learned to read or write English,12 Mary lived the dream of seeing her children receive a formal education and become respected members of the community. She purchased property and in 1885 moved into her own newly built home.13 Modest but comfortable, this home in America represented Mary Hafford’s climb up the social ladder and her rise in respectability, and it gave her a place to proudly hang her lovely Irish lace curtains.

When the Mary Hafford home was relocated from the Village of Hubbleton to Old World Wisconsin, it was rebuilt atop a hill overlooking a restored prairie.

LOYD HEATH

THE ROSE: THE QUEEN OF ALL FLOWERS

THE ROSE: THE QUEEN OF ALL FLOWERS

For centuries roses truly have been considered the queen of all flowers. In 1825 Elizabeth Kent penned words of enthusiasm for the beloved rose:

Poetry is lavish of Roses; it heaps them into beds, weaves them into crowns, twines them into arbors, forges them into chains, adorns with them the goblet used in the festivals of Bacchus, plants them in the bosom of beauty,—Nay, not only delights to bring in the Rose itself upon every occasion, but seizes each particular beauty it possesses as an object of comparison with the loveliest works of nature:—as soft as a Rose leaf; as sweet as a Rose; Rosy-clouds; Rosy-cheeks; Rosy-lips; Rosy-blushes; Rosy-dawns, etc., etc.1

NOTE

1. Elizabeth Kent, Flora Domestica, or The Portable Flower-Garden (London: Taylor and Hessey, 1825), 265.

Fragrant old-fashioned roses invite visitors to pause outside the restored home of Mary Hafford at Old World Wisconsin.

TERRY MOLTER

PLANTS BEYOND THE KITCHEN GARDEN

PLANTS BEYOND THE KITCHEN GARDEN

Although the early Irish immigrants rarely planted gardens exclusively of flowers, they brought memories and an appreciation of all living things from the beloved land left behind. Even Irish horticulturalist William Robinson (1838–1935) carried the inspiration of the woodlands and wildflowers as well as the simple gardens of the cottagers of his native country into his writings and garden designs for the elite of England and beyond.

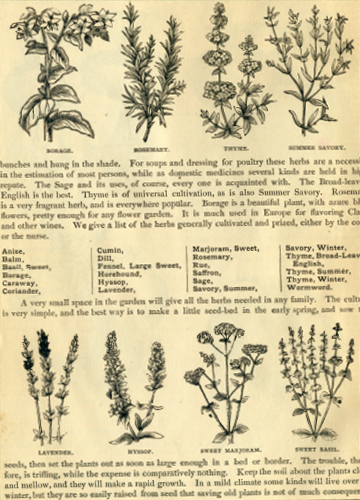

A listing of “sweet and pot” herb seeds available for purchase from Vick’s Seed Company in 1876

VICK’S FLOWER AND VEGETABLE GARDEN

Those remembering the Old Country might have chosen to plant some of the following plants, all fondly remembered from their Irish homeland: buttercup, wild carrot, white daisy, foxglove, heather, iris, Johnny-jump-up, lavender, lily, corn marigold, pot marigold, may flower, nasturtium, periwinkle, primrose, rose, wallflower. Yarrow might be cut on Midsummer’s Eve and hung in the house to ward off illness.

Familiar herbs included lemon balm, chamomile, sweet cicely, hyssop, lovage, marjoram, parsley, southernwood, and tansy. Some were used for tea, others became ingredients in sachets or insect repellent blends, and some added their magic to potions and spells.

Elderberry, holly, rowan, and whitethorn also earned respect. Ferns grew so fern seed—said to render men invisible—might be collected for its magical powers!1

NOTE

1. E. Estyn Evans, Irish Folk Ways (New York: The Devin-Adair Company, 1957); Patrick Logan, Irish Country Cures (New York: Sterling Publishing Co. Inc., 1994); Terence Reeves-Smyth, The Garden Lover’s Guide to Ireland (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2001); William Robinson, The English Flower Garden (New York: The Amaryllis Press, 1984).

Even when they were far from wealthy, Irish-American women enjoyed creating warm and welcoming home environments.

TERRY MOLTER

Fragrant lilacs, roses, and lavender welcome visitors to the Mary Hafford House, which was restored to its 1885 appearance after being moved to Old World Wisconsin from the Village of Hubbleton, Jefferson County, in 1980. Inspired by plants familiar from Hafford’s homeland, a small cottage garden abounds with flowers and herbs. Located in the front yard near the main entrance to the house, the garden is situated to be admired. This small, well-tended jewel is lush with sweet pinks, violets, and wallflowers; delicate harebells and daisy-like chamomile; cowslips and calendulas in shades of sunshine gold; umbels of soft white yarrow; and spiky hyssop. Alpine strawberries luxuriate among the flowers, and gray santolina, placed intermittently along the borders, stands guard against inquisitive bunnies. Inside the house, a wire plant stand in the front room holds treasured potted plants such as ivy and flowering and rose-scented geraniums.

By 1885 Mary Hafford had been in America for more than twenty years. Comfortably settled in her community, she was mindful of current gardening and decorating trends. By planting a decorative garden in the front yard in the American style and filling it with plants of her homeland, she maintained her ties and loyalty to both countries.

Irish Recipes

Irish Recipes

Tea and Irish soda bread in the Mary Hafford House at Old World Wisconsin

LOYD HEATH

Irish Soda Bread

This classic hearty Irish bread is a wonderful accompaniment for soups, stews, and boiled dinners. Our recipe, from the Miller family of County Roscommon, dates to 1857. Baking soda serves as the leavening agent.

6 cups flour (or 4 cups whole wheat flour and 2 cups white flour)

1 teaspoon of bicarbonate of soda (baking soda)

1 teaspoon salt (if using buttermilk, add about 2 tablespoons)

1 cup buttermilk, sour milk, or fresh milk (if using fresh milk, add 1 teaspoon of cream of tartar to dry ingredients)

Mix dry ingredients together and make a well in the center. Add enough milk to make a thick dough. Stir with wooden spoon, mixing lightly. Add a little milk if using whole wheat and it seems too stiff. Put onto lightly floured board or table and flatten dough into circle about 1½ inches thick. Put on baking sheet or pie pan. Cut a large cross over it with floured knife to ensure even distribution of heat. Let stand for about 20 to 25 minutes before baking. Bake in moderate [350 to 375 degree] oven for about 40 minutes.1

Boiled Dinner

Boiled foods are traditional in Ireland. Any vegetables may be added and simmered until tender. Root vegetables are especially well suited for this one-pot meal.

In a large kettle or saucepan simmer pork hocks and pork pieces in several quarts of cold water. Season with salt and pepper. Prepare cabbage, carrots, potatoes, and onions by first slicing into hunks (and then mincing finely in a large chopping bowl with a chopping knife, if desired). Add to pork stock. Small potatoes and onions can be added whole. Serve from platter onto deep dishes or soup bowls.2

This engraving shows the comparative size and growth habit of the leading varieties of carrots in 1876: 1. Long Orange; 2. Orange Belgian Green-Top; 3. Early French Short-Horn; 4. White Belgian Green-Top; 5. Early Very Short Scarlet; 6. Half-Long Scarlet Stump-Rooted; 7. Altringham; 8. Half-Long Scarlet

VICK’S FLOWER AND VEGETABLE GARDEN

Creamed Cod Over Boiled Potatoes

Salt cod added flavor to the mountains of bland potatoes consumed by the Irish in the nineteenth century.

codfish, salted and dried (salt cod)

cold water

2 potatoes

1 small onion, chopped

salt

flour

butter

milk

Flake cod and place it in a pan of cold water; allow it to soak overnight. In the morning place the cod in fresh cold water in a covered saucepan. Heat the cod on the stove to scalding point; do not boil.

Wash potatoes and cut off ends; let them stand in cold water for a few hours. Put the potatoes and onion into a pan of boiling water, cover, and keep boiling constantly. After 15 minutes, throw in some salt and boil for another 15 minutes. Test with fork.3

After draining the cod, add flour, butter, and milk to make a cream sauce. Serve immediately over boiled potatoes.

Borreen Brack

Borreen brack translates to “speckled loaf”—a reference to the currants in the bread. Traditionally the loaves were measured by the size of a woman’s fist: two fists long, two fists wide, and one fist thick. A “small spoon” is equal to a teaspoon.

1 cup scalded milk

½ cup freshly churned butter, salted

3 large eggs

⅔ cup sugar

1 large spoon of barm (beer yeast)

5 cups flour

1 small spoon salt

1 small spoon allspice

1½ cups currants

melted butter

additional sugar

Pour scalded milk over butter to melt; cool. Mix well eggs, sugar, and barm and add to cooled milk mixture. Mix in flour, salt, allspice, and currants. Knead the dough thoroughly and then place in a buttered bowl and cover. Let rise to double in bulk. Turn out and punch down. Divide dough and put into 2 buttered pans. Cover and let rise again until doubled in bulk. Bake at 350 degrees for 30 to 45 minutes. By this time it should be browned and done. Brush the loaves with melted butter and sprinkle with sugar.4

Fresh Fruit Bottled

Bottling fresh fruit offered an alternative to drying as a method of preservation in a damp climate. Burning a match in the bottle displaced air and replaced it with a sulfurous acid gas that acts as a preservative.

fresh fruit of all kinds (let the fruit be full grown)

Have some perfectly dry glass bottles and some nice soft corks. Burn a match in each of the bottles and quickly place fruit in to be preserved. Gently cork the bottles. Put them into a very cool oven until the fruit has shrunk away a fourth. Beat the corks in tight, cut off the top, cover with wax. Keep in a dry place.5

Sponge Cake

A simple sponge cake, made from this recipe dating to 1876, provides a perfect sweet touch to the end of any meal. A “quick” or hot oven referred to how fast the oven was burning and was equivalent to 400 degrees.

3 eggs

1 cup sugar

1 cup flour

1½ teaspoons baking powder

Separate the eggs and beat yolks and sugar together. Mix in flour and baking powder. Beat egg whites until stiff but not dry; fold into mixture. Pour into a well-oiled loaf pan and bake in a quick oven.6

Potato Candy

This is another tribute to the Irish sweet tooth—and another recipe for potatoes!

1 cup warm, unseasoned mashed potatoes

½ teaspoon salt

2 teaspoons vanilla

about 2 pounds confectioners’ sugar

Combine potatoes, salt, and vanilla in mixing bowl. Sift sugar over potatoes, about 1 cup at a time, stirring constantly, until mixture is like a stiff dough. Knead well, adding more sugar as needed. Cover with a damp cloth and chill until a small spoonful can be rolled into a ball. Shape into small balls. Makes about 2 pounds.7

Cough Syrup

This cough syrup recipe seems a bit intense, but it is surely preferable to an old Irish treatment for whooping cough that recommended boiling the droppings of sheep in milk and giving the mixture to the patient!8

One pint of the best vinegar. Break into it an egg and leave in the shell and all, overnight (or longer). In the morning it will all be eaten except the white skin, which must be taken out. Then add one pound of loaf sugar and take a tablespoon three times a day, for an adult. This is a most excellent remedy for a cough in any stage.9