Chapter 7 Leveling Up with Design

Chapter Objectives

Chapter Learning Objectives

Hone your creativity.

Prepare your mind for design.

Apply the design hierarchy.

Discover the elements of art.

Understand the element of shape.

Learn how color works.

Explore typography.

Understand the principles of design.

Chapter ACA Objectives

For full descriptions of the objectives, see the table on pages 270–276.

DOMAIN 1.0

WORKING IN THE DESIGN INDUSTRY

1.5, 1.5a, 1.5b

![]() ACA Objective 1.5

ACA Objective 1.5

Now that you have a good grasp of the tools in Adobe InDesign CC, you’ll start learning how best to use them. Much as with any other skill, understanding how a tool works and becoming a master craftsperson are two completely different levels of achievement. In many ways, they’re distinct ways of thinking about the tools you’ve learned to use.

![]() Video 7.1

Video 7.1

Design School: Introduction

As an example, think about carpenters. Their initial level of learning covers tools such as saws, hammers, and drills. They learn how to use the tools correctly and when to apply specific techniques, including cutting with or against the grain and joining the wood at the joints. Using the right techniques, carpenters can theoretically build anything.

You’re now at the point at which the only way to get better is to practice and learn the thought processes that a master craftsperson goes through to create amazing, creative, and unique work. The beauty of this stage is that it’s when you start to become an artist. Being good at using any tool is not just about knowing how it works and what it does. It’s about knowing when to use it and what techniques to apply to create something new.

Creativity Is a Skill

![]() Video 7.2

Video 7.2

Design School: Creativity Is a Skill

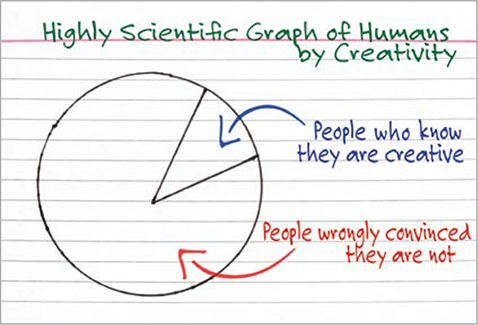

Let’s look at a highly scientific and statistically accurate diagram (Figure 7.1).

Okay, so perhaps the diagram isn’t exactly statistically accurate and maybe my methods weren’t scientific, but it’s still true. Creativity is a skill that you can learn and improve with practice. But there’s only one way to guarantee that you’ll never be more creative than you are now: give up.

The biggest creative problem some people have is that they give up. Some give up before even making their first effort. Others give up after their fifth effort or after 15 minutes of not creating a masterpiece. Nobody creates a 15-minute masterpiece. A big difference between a great artist and a terrible one is that a great artist has tried and failed, made some adjustments, and tried again. The next try may also lead to failure, but the artist pushes forward. The artist isn’t deterred by bumping into a problem, because it’s all part of the learning and creative process.

Of course, you can’t know how far you can take your creative skills until you start practicing and expanding those skills. But if you never use them, they’ll only grow weaker. Remember that every effort, every new attempt, and every goof-up builds strength.

Getting a Creative Workout

This chapter is about developing your creative skills and flexing your creative muscles. It’s about turning the craft of being a visual designer into a natural ability. Even if you take the big step of becoming an Adobe Certified Associate, you need to realize that passing the test is just getting through the tryouts. When you get that credential, it’s like being picked to be on a professional football team. It’s certainly something to be proud of, but the real goal is the Super Bowl! You have a lot more work ahead, but it’s fun and rewarding work.

This book introduces you to exercises that help you explore and enhance the skills you already have. Getting beyond the basics of creativity and design is just a matter of applying your existing skills in ways you’ve never tried. That’s all there is to creativity.

Prepping Your Mind

Preparing your mind is the most important part of increasing your creative skills. For most of us, it’s also the hardest because today’s culture is so focused on instant success and efficiency that people learn to fear the essence of creativity: failure.

Failure—and more specifically, the ability to take failure in stride—is the key ingredient to developing your artistic skillset. This is especially true if you’re a beginner and you aren’t entirely happy with your current abilities. Just face that you’re a design baby—and start acting like one!

Yes, I just encouraged you to act like a baby. But I mean an actual infant, not a grown person who is throwing a fit. Babies are fearless and resilient when they fail. They keep trying. They don’t give up. Most of the time, they don’t even realize that they’re failing because they haven’t yet learned that concept.

That’s what you need to tap into. In art, there are no failures—there are only quitters. Tap into your inner infant! Try and fail, and try and fail, and try and fail. Eventually, you’ll take your first step. You may quickly fail again on your second step, but don’t give up. Babies don’t know that they’ve failed. They just know that they got a little bit closer. They know what every true artist knows and what the rest of us need to remember but have forgotten along the way: Failure is the path.

The Design Hierarchy

![]() ACA Objective 1.5

ACA Objective 1.5

![]() Video 7.3

Video 7.3

Design School: The Design Hierarchy

Most of us recognize art when we see it, but nobody can agree on how to create it. In an attempt to provide a framework, artists have developed a list of elements of art, the building blocks of art, and principles of design, the essential rules or assembly instructions of art. Although every artist understands the importance of the elements and principles of art, there is no official list of those elements and principles that all artists agree on. This can be incredibly frustrating. How can you study and learn about something that nobody can fully identify?

Celebrate this fact—the lack of an “official” list means that you can’t be wrong. A sculptor and a painter see and approach their art in different ways. A movie producer approaches her art differently than a costume designer approaches his. But all of these artistic people still study and embrace the elements and principles to guide their art.

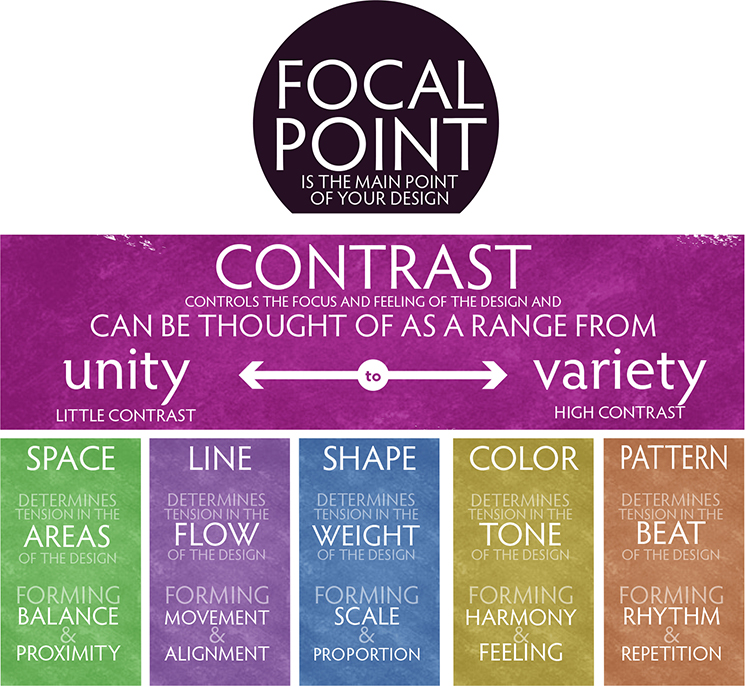

Applying the Design Hierarchy

The design hierarchy shown in Figure 7.2 is one way to understand and think about the artistic elements and principles. This isn’t the ultimate approach to understanding and interacting with the artistic elements and principles. (An “ultimate” approach probably doesn’t exist.) It is more an organized starting place that might help you focus your design skills.

Design, unlike art, generally has a purpose. It’s often about creating or accomplishing something specific rather than about simply enjoying or exploring an artistic impulse. A design task might require that you advertise a product, communicate an idea, or promote a cause or specific issue. I find it much easier to think about artistic elements and principles in terms of design, and you can use a design task as a framework on which to “hang” your creative quest when those vague artistic elements and principles seem confusing or muddled.

Thinking through these building blocks can also serve as a great little exercise when you’re looking at a piece of work that you are not happy with but can’t quite figure out why. Sometimes, just rolling through the following elements and principles in your mind can be an excellent creative checklist.

Start with a Focal Point

The focal point is what your design is all about. In an advertisement, it’s your “call to action” phrase that will motivate the consumer. For a cause, it’s the primary message that your cause is trying to get across. In visual design, it could be the navigation elements or the major interactive elements. It’s the primary idea that you want people to take with them, like the title of a book or chapter. It’s the “sales pitch” of your design.

The focal point should be the most memorable aspect of the design. In a symmetrical or radial design, center the focal point for the most emphasis. In an asymmetrical design, let it fall on one of the natural focal points, which you’ll learn about shortly when you study space.

Critical Question: Do people know where to look in my design?

Create Focal Points Using Contrast

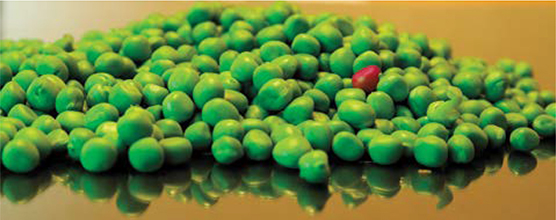

Contrast creates a focal point by generating “tension” in the image (Figure 7.3). Place one red golf ball in a pile of 10,000 white golf balls, and you’ll notice it immediately. The most dramatic way to create contrast is to vary the most common characteristic of the elements in the design. If you have a number of multicolored circles that are the same size, then varying the size of one circle, regardless of its color, will create a contrast that draws the eye. Keep the shape the same size, but make it a star instead of a circle to generate the same tension.

Establishing unity in a design is essential to allowing you to create tension. Without a degree of unity, you cannot create a focal point and the eye struggles to find something to focus on. Design is about forcing a focal point to be where you want it. When too many different, unrelated elements are present in your design it makes chaos, and the viewer will not know where to look.

Critical Question: Does my design lack sufficient contrast to see the important features clearly?

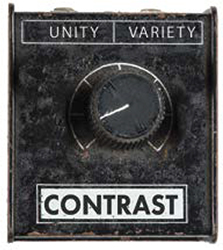

Ranging from Unity to Variety

Imagine that contrast can be described as the “tension” in the image, and that contrast is a range from low contrast, which we call unity, to high contrast, which we call variety. Compositions with very low contrast have very little tension, and these designs are generally perceived as peaceful and calm but can sometimes feel emotionless, cold, and lifeless. Compositions with very high contrast have a lot of tension; they’re generally perceived as energetic, lively, active, and hot, but sometimes they feel unpredictable or emotional (Figure 7.4).

A Framework for Connecting the Dots

The following framework connects artistic elements and principles to help you at the onset of the creative journey. They’re good starting points. Remember that with any design, you’re not trying to define the artistic elements and principles as much as you’re trying to embrace and apply them. As with every study of the artistic elements and principles, you won’t arrive at a destination. Rather, you’ll embark on a journey. These connections should help you make sense of the elements and principles long enough to find your way to understand and apply them.

Create Balance and Proximity by Arranging the Elements in your Compositional Space

Tension develops among the various areas of your composition; unify the design with symmetry and equal spacing, or vary it using asymmetry and grouping elements.

Critical Question: Does my design use space to help communicate relationships?

Create Movement and Alignment by Arranging your Elements Along Lines

Tension is created in the direction or flow of your composition; unify the design with strict alignment or movement along straight or flowing lines, or vary it with random, chaotic movements away from any single line or flow.

Critical Question: Does my design use lines to communicate order and flow?

Create Scale and Proportion by Carefully Designing Shapes in your Composition

Tension is created among the sizes of elements in your composition; unify the design with similar or related sizes of elements, or vary it with a mix of unrelated sizes. Keep in mind that a paragraph has a shape, and a group of elements has a shape. Look at areas as well as objects in your design.

Critical Question: Does my design consider the message sent by the size of shapes I create?

Create Themes and Feeling by Using Typography, Colors, and Values in your Composition

Tension is created among elements of different types, values, or colors. Unify the design with related types, colors, and values, or vary it with clashing colors or extreme differences in values or type.

Critical Question: Does my design consider the message sent by the typography, color, and value I used?

Use Repetition and Rhythm to Create Patterns and Texture in your Compositions

Tension is created among elements with different texture or patterns. You can unify design with simple repetition to produce predictable patterns and rhythms, or vary it by using complex, irregular, or chaotic patterns and rhythms.

Critical Question: Does my design consider the message sent by the patterns and textures I designed?

Wrapping Up the Design Hierarchy

If you’re familiar with the basic artistic elements and principles, this hierarchy might be a framework you can use. But the goal of art is to continually explore the elements and principles. The next section covers them all, along with some challenges designed to help you dig a little deeper.

The Elements of Art

![]() ACA Objective 1.5a

ACA Objective 1.5a

![]() Video 7.4

Video 7.4

Design School: The Elements of Art

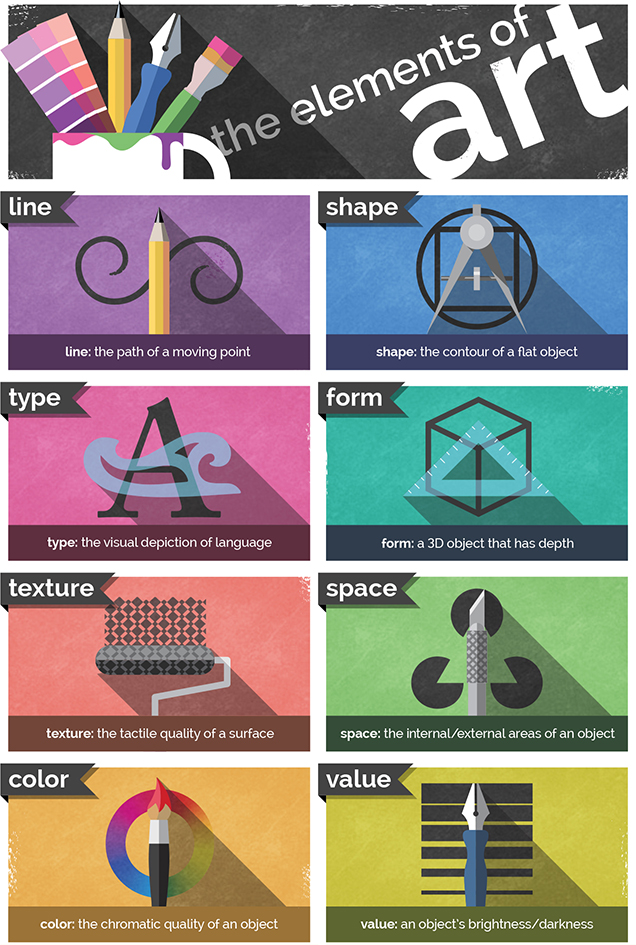

The elements of art (Figure 7.5) are the building blocks of creative works. Think of them as the “nouns” of design. The elements are space, line, shape, form, texture, value, color, and type. Many traditional artists leave type off the list, but for graphic designers it is a critical part of how we look at design (and besides that, type is really fun to play with).

The Element of Space

![]() Video 7.5

Video 7.5

Design School: The Element of Space

Space is the first element of art to consider (Figure 7.6). It also happens to be one of the most abused, overlooked, neglected, and underrated elements in design. You can look at and consider space in multiple ways.

Space as your Canvas

The most basic way to look at space is as your canvas or working area. In InDesign, you start a new document and specify its dimensions to create your space. Sometimes the dimensions are specified and provided to you, such as when you’re designing for a specific project size or screen resolution. But sometimes you can create a fun way to work by giving yourself an uncommon space to design in.

Space as a Creative Tool

Another important way to look at space is as a design element (Figure 7.7). The inability to use space well is an obvious sign of a new designer. A crowded design practically screams “newbie”! It takes a while to use space well, and it requires some practice. Start learning to use space as a creative element and you’ll see a drastic increase in the artistic feel of your designs.

When used properly, space can provide the following benefits to your designs:

Creating emphasis or focus: When you have space around an object, it tends to give it emphasis. Crowding things makes them seem less important.

Creating feeling: Space can be used to create a feeling of loneliness, isolation, or exclusivity. It can also be used to create a feeling of seriousness or gravitas.

Creating visual rest: Sometimes space is needed to simply create some visual “breathing room” so that the other elements in your design can speak as intended.

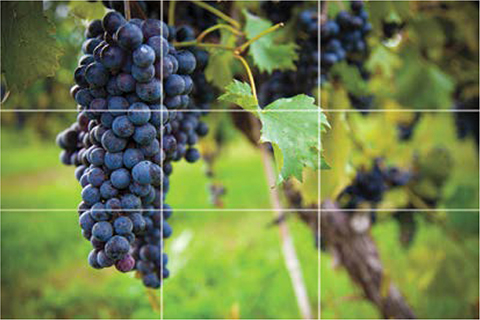

The Rule of Thirds

Tip

Beginning designers center everything, which can contribute to a static look and boring feeling. One way to get started with the rule of thirds is to simply stop centering things. You’ll notice that you tend to move elements quite naturally to a focal point suggested by the rule of thirds.

The rule of thirds (Figure 7.8) is critical in photography and video, and it also applies to all visual arts. To visualize it, think of the rule of thirds as a tic-tac-toe board overlaid onto your design. Two horizontal and two vertical divisions create nine equal boxes on your design. The basic rule is that major elements of your design should fall on the dividing lines, and the areas of emphasis for the design should fall on the intersections. Using this rule in your designs creates compositions that have much more interest, tension, and visual strength.

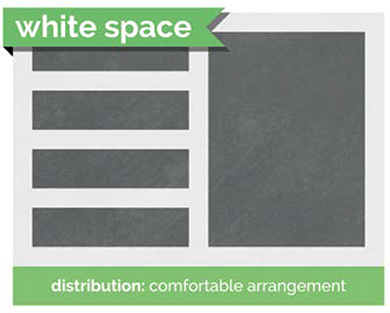

Negative Space

In the design industry, people use the term negative space, or “white space,” to refer to blank areas in the design, even if you’re working on a colored background. Negative space (Figure 7.9) is one of my favorite creative uses of the element of space. It can be fun to explore using negative space to create clever logos or designs.

Tip

You can see an awesome collection of updated examples of negative space online at www.brainbuffet.com/design/negative-space.

Note

For many people, the terms negative space and white space are interchangeable. If you’re unclear about what someone is asking for, seek clarification. Art and design are not entirely technical, accurate, and organized processes, so you’ll need to get used to lots of “mushy” terms that are used in multiple ways.

Sometimes you can place a boring idea in negative space to get moving in a new, creative direction. It can be tough for beginners to even “see” negative space, but once you look for it, you’ll start to see creative uses of it everywhere. Begin to use it and your design skills will jump up a level.

From here on out, the elements get much easier to understand because we can think of them as things (whereas we tend to think of space as the absence of things, or “nothing”). Learn to use space well. The ability to do so is the mark of an experienced and talented artist.

The Element of Line

![]() Video 7.6

Video 7.6

Design School: The Element of Line

The meaning of line is pretty obvious. Although technical definitions such as “a point moving through a space” exist, we are all aware of what a line is. A line is exactly what you think it is: a mark with a beginning and an end (Figure 7.10). Don’t overthink the basics. We’re going to dig deeper than that, but let’s start with the basic idea and then build the new understanding on it.

Common Line Descriptors

The following qualities are often associated with lines, and thinking about the ways lines are used or drawn can help you determine the meaning that your lines are giving to your design.

Tip

Having a hard time remembering horizontal and vertical directions? “Horizontal” (like the horizon) has a crossbar in the capital “H” that is a horizontal line itself. Vertical starts with the letter “V,” which is an arrow pointing down.

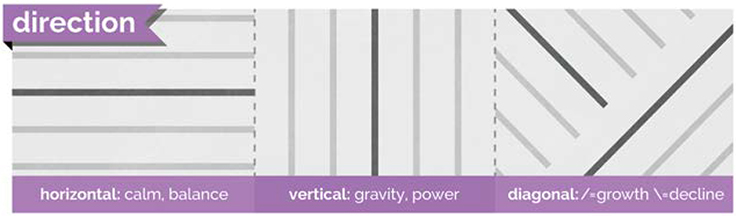

Direction (Figure 7.11): The directions of the lines in your art imply certain feelings or subconscious messages. Vertical lines tend to express power and elevation, whereas horizontal lines tend to express calm and balance. Diagonal lines often express growth or decline, and they imply movement or change.

Figure 7.11 Line direction can communicate feeling in your designs. Weight (Figure 7.12): The weight of a line describes its thickness. Heavy or thick lines generally represent importance and strength, and they tend to feel more masculine. Light or thin lines generally communicate delicacy and elegance, and they tend to represent femininity.

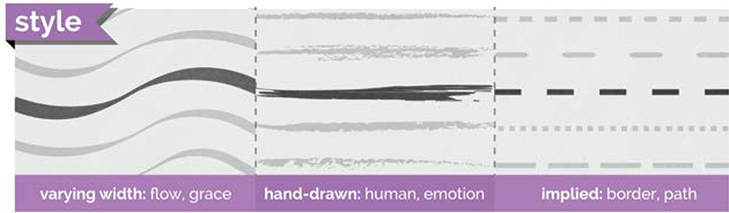

Figure 7.12 The weight of your lines communicates different feelings or concepts as well. Style (Figure 7.13): A line style is an effect, such as a double line or dotted line. Varying-width lines are useful for expressing flow and grace. Hand-drawn lines look as if they were created with traditional media such as paints, charcoal, or chalk. Implied lines are lines that don’t really exist—like dotted or dashed lines, or the lines we create when we line up at the grocery checkout. These implied lines are powerful tools for designers; individual things can feel unified or grouped together when they are aligned (you’ll find out more about implied lines in a moment).

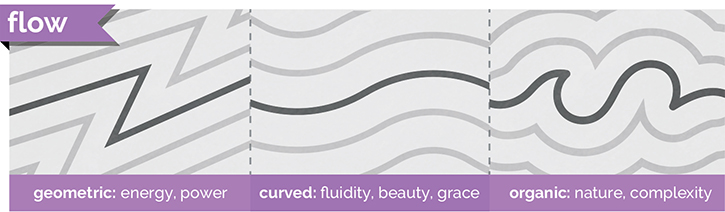

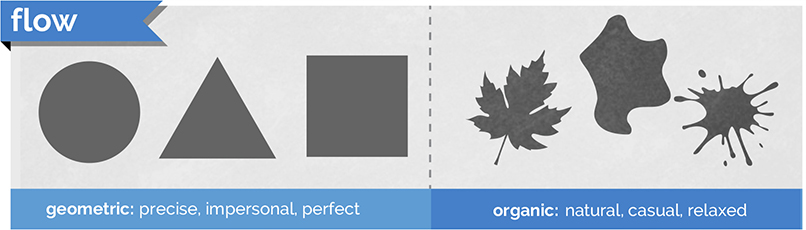

Figure 7.13 Line styles are the most popular way to communicate feeling. Flow: We’ve created this word for the category that is related to the energy conveyed by lines and shapes. Geometric lines tend to be straight and have sharp angles; they look manmade and intentional. Geometric lines communicate strength, power, and precision when used in design. Curved lines express fluidity, beauty, and grace. Organic lines are usually irregular and imperfect—the kind of lines you find in nature or as the result of random processes. Organic lines represent nature, movement, and elegance. Chaotic lines look like scribbles and feel unpredictable and frantic. They convey a sense of urgency, fear, or explosive energy (Figure 7.14).

Figure 7.14 Line flow can communicate energy. Implied lines: If you look at the leftmost line of these paragraphs, you can see a “line” formed by the beginning of each line of type. Pay attention to the implied lines you create using the design elements in your artwork. Think of creative ways to use and suggest lines, and pay attention to what you might be saying with them. Make sure the message that all your lines send matches the intent of your work. Implied lines are similar to negative space; learning to work with them can boost your design skills exponentially (Figure 7.15).

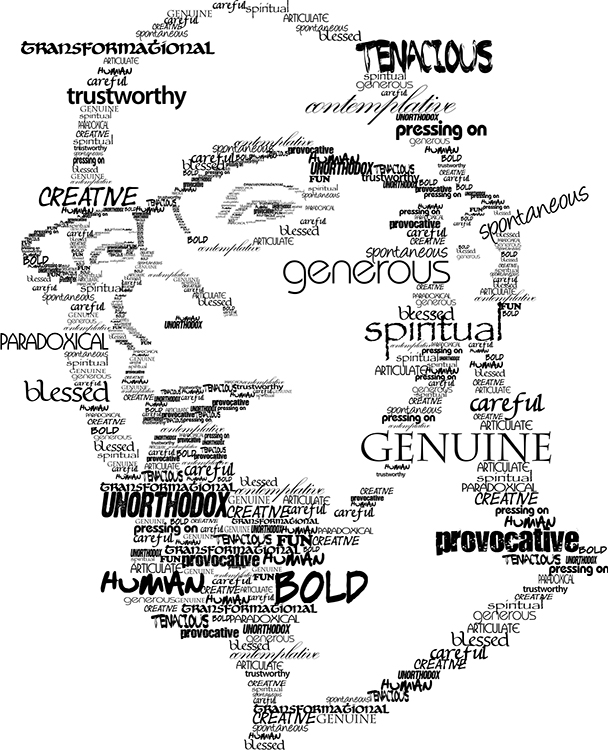

Figure 7.15 Typographic portraits are excellent examples of the use of implied lines. Here you can see the image of a face, even though there is nothing but carefully arranged text.

The Element of Shape

![]() Video 7.7

Video 7.7

Design School: The Element of Shape

The next element needs little introduction: Shape (Figure 7.16) can be defined as an area enclosed or defined by an outline.

We’re familiar with shapes such as circles, squares, and triangles, but there are many more shapes than that. Those specific shapes are created in geometry, but what about the shape of a hand or cloud (Figure 7.17)? These are shapes too, and we often use the same descriptors for shapes as we do for lines.

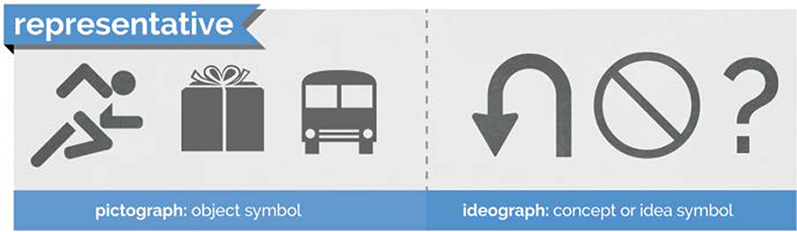

Representative Shapes

A pictograph (or pictogram) is a graphic symbol that represents something in the real world (Figure 7.18). Computer icons are pictographs that often suggest the function they represent (like a trash can icon to delete a file). Other examples of pictographs are the human silhouettes often used to indicate men’s and women’s restrooms. They’re not accurate representations of the real objects, but they are clear representations of them. Ideographs (or ideograms) are images that represent an idea. A heart shape represents love, a lightning bolt represents electricity, and a question mark represents being puzzled. Representative shapes are helpful in communicating across language barriers and can be valuable when you are designing for multicultural and multilingual audiences.

The Element of Form

![]() Video 7.8

Video 7.8

Design School: The Element of Form

Form (Figure 7.19) describes three-dimensional objects, or at least objects that look 3D. The best way to visualize form clearly is to consider that circles, squares, and triangles are shapes, whereas spheres, cubes, and pyramids are forms. Like shapes, forms are basically divided into geometric and organic types. Geometric forms, such as a cube, are common to us. We are also familiar with organic forms such as the human form or the form of a peanut. When you work with 3D in applications, these forms are often referred to as “solids.”

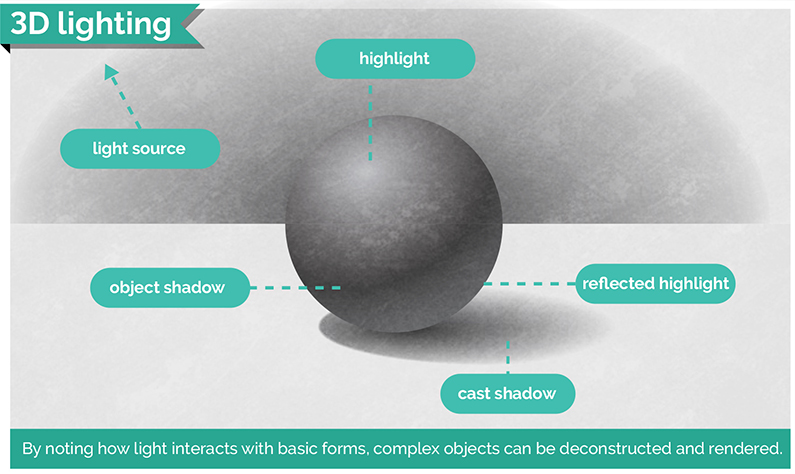

3D Lighting

In art and design, we place a special focus on the techniques that make images appear 3D in a 2D work of art. You have some standard elements to consider when you want to create a feeling of depth and form. Figure 7.20 explains the standard elements of a 3D drawing.

Highlight: The area of a form directly facing the light; appears lightest.

Object shadow: The area of the form that is facing away from the light source; appears darkest.

Cast shadow: The shadow cast on the ground and on any objects that are in the shadow of the form. One thing to remember is that shadows fade as they get farther from the form casting the shadow. Be sure to take this into account as you’re creating shadow effects in your art.

Light source: The perceived location of the lighting in relation to the form.

Reflected highlight: The area of the form that is lit by reflections from the ground or other objects in the scene. This particular element of drawing a 3D object is most often ignored but provides believable lighting on the object.

The Elements of Pattern and Texture

![]() Video 7.9

Video 7.9

Design School: The Elements of Pattern and Texture

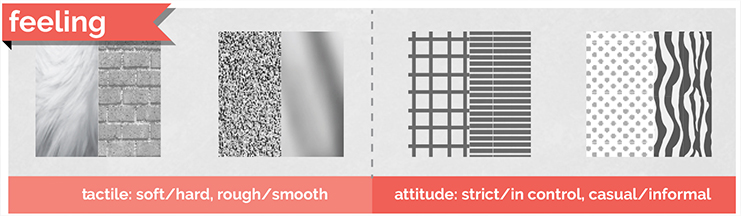

Pattern (Figure 7.21) can be defined as a repetitive sequence of colors, shapes, or values. Pattern is technically a different concept from texture, but in graphic design it’s often regarded as the same thing. Let’s face it: All of our “textures” are just ink on paper or pixels. Any repetitive texture might also be considered a pattern. (Think of “diamond plate” or “tile” textures. They’re just a pattern of Xs or squares.)

Texture (Figure 7.22) can describe an actual tactile texture in real objects or the appearance of texture in a 2D image. It’s important to use texture to communicate feeling and authenticity in your art or designs. If you want to depict something elegant, soft, or comfortable, you could use a texture that resembles fabric or clouds. To represent strength or power, you might choose textures that represent stone or metal. And you could represent casual, informal, or nostalgic feelings using a texture that represents weathered wood or worn paint.

As you work more as a designer, you’ll start to notice the nuances and subtle differences between textures and patterns. For now, just think of them as the visual qualities of your shapes and forms that can’t be described by color and/or value alone.

The Element of Value

![]() Video 7.10

Video 7.10

Design School: The Element of Value

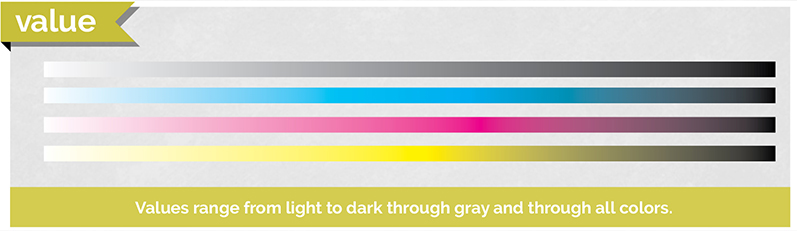

Value (Figure 7.23) describes the lightness or darkness of an object. Together with color, value represents the entire visible spectrum. You can think of value as a gradient that goes from black to white. But remember that value applies to color as well, and you can have a spectrum that fades from black, through a color, and then to white. From this comes the idea of a “red black” or a “blue black” introducing a hint of color to your blacks (Figure 7.24). You’ll explore that concept later in this chapter.

Professionals in the art and design industry sometimes use the term value, but clients rarely use it. Clients will just ask you to lighten or darken a graphic or text, or sometimes use tint, shade, or tone in place of value. Technically, these terms are different, but many people use tone, shade, tint, and value interchangeably. As always, when clients use a term and you’re not exactly sure what they mean, ask for clarification. Sometimes clients don’t know exactly what they mean, so asking ensures that everyone is on the same page.

The Element of Color

![]() ACA Objective 1.5

ACA Objective 1.5

![]() Video 7.11

Video 7.11

Design School: The Element of Color

When you think about it, color is hard to define. How would you define color without using examples of colors? Check out its definition in a dictionary and you’ll find that defining color doesn’t help you understand it. Color is best experienced and explored (Figure 7.25).

We have so many ways to think about color and so many concepts to dig into that exploring color is a lifelong pursuit for most artists and designers. Color theory is a deep and complex study. You’ll explore the basics here, but remember that this is just the on-ramp to understanding color. Grasp these concepts and you’ll still have a lot more to learn.

Color psychology is a relatively new discipline and an interesting study that focuses on the emotional and behavioral effects that colors have on people. The colors you choose really do matter. For our purposes, we’ll define color as the perceived hue, lightness, and saturation of an object or light.

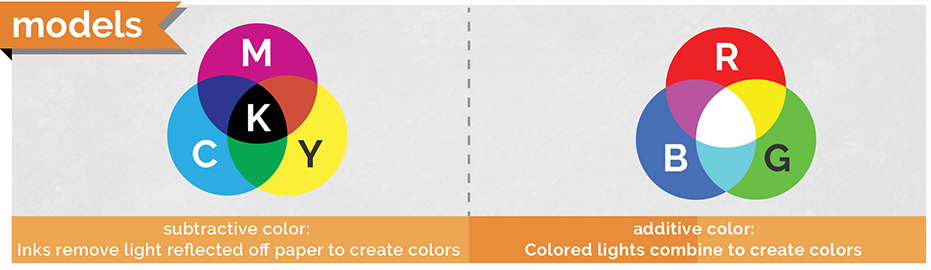

How Color Works

Color is created in two ways: combining light to create additive color and subtracting light to create subtractive color (Figure 7.26). In InDesign, the intent you select when creating a new document defines how the color is created.

Tip

In InDesign, set the intent of a new document (File > New > Document) to Web or Digital Publishing to work with additive color and RGB.

Tip

In InDesign, set the intent of a new document (File > New > Document) to Print to work with subtractive color and CMYK.

Additive color is created by combining light. This is how your monitor works, and the most common color mode for additive color is RGB. The letters RGB stand for red, green, and blue, which are the three colors used to create digital images. Monitors and electronic devices are dark when turned off, and you create colors by adding light to the screen. When designing for web or digital publishing in InDesign, you’ll work with additive color.

Subtractive color is created by subtracting light. This is the color system you learned in early art classes in which red, blue, and yellow were the primary colors. For print, we use CMYK, which is cyan, magenta, yellow, and black. We start with a white surface (the paper) that reflects all the light back to us. Then we subtract color by using paints or inks that limit the light that is reflected back to the viewer. When creating InDesign documents for print, you work with subtractive color.

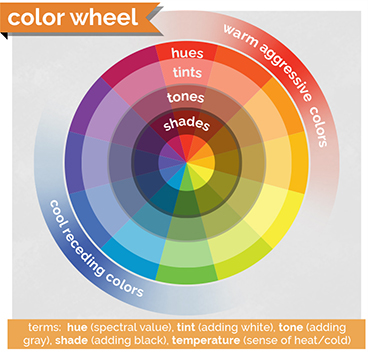

The Color Wheel

Sir Isaac Newton invented the color wheel (Figure 7.27) in the mid 1600s. The color wheel offers a way to display and build all the colors possible using paint. It’s a common exercise in beginning art classes to create a color wheel when learning to mix and experiment with colors. In digital imaging, it’s not as important to go through this exercise, but if you have a chance, give it a try. It’s interesting to see how all of the colors can mix to obtain the infinite colors and shades the human eye can perceive.

The color wheel is important because many color theories we use are named after their relative positions on the color wheel. They’re a lot easier to remember if we use the color wheel to illustrate.

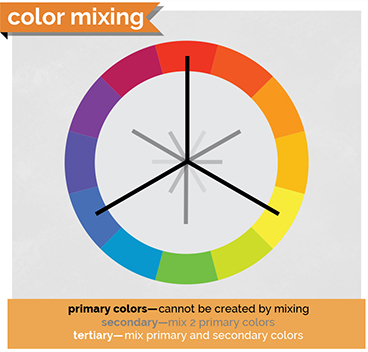

The first thing to realize is that some colors are classified as primary colors. These colors can be combined to create every other color in the visible spectrum. For subtractive color used in traditional art, the primary colors are red, blue, and yellow. For additive colors, the primary colors are red, blue, and green.

The colors that are created when you combine primary colors are called secondary colors because you can create them only by applying a second step of mixing the colors. When we mix secondary and primary colors, we get another set of colors, known as tertiary colors. Figure 7.28 illustrates how these colors are built.

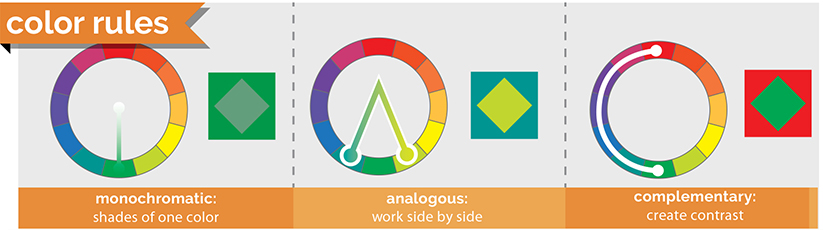

Basic Color Rules

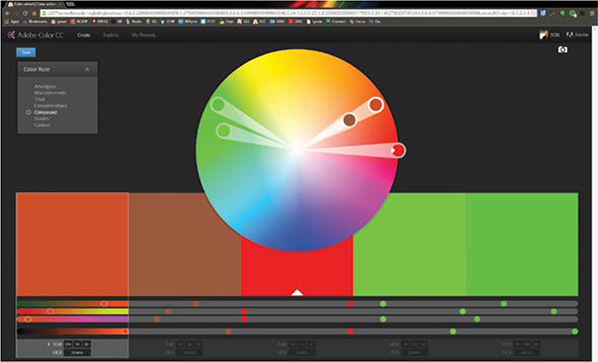

Color rules (also called color harmonies) are a great way to start picking colors for your design projects. The color rules (Figure 7.29) are all named for their relative locations on the color wheel. We will cover some of the basic color rules and the impressions they tend to communicate.

The three most common ways of thinking about colors (and, really, the basis of all color rules) are as monochromatic, analogous, and complementary color schemes.

Monochromatic: Monochromatic colors, as you’ve probably guessed, are based only on different shades and tints of the same color. They tend to communicate a relaxed and peaceful feeling, and you’ll create little contrast or energy in art using these colors.

Analogous: If you want to add a little more variation while maintaining a calm feeling, consider analogous colors. Analogous colors sit side by side on the color wheel, and they tend to create gentle and relaxing color schemes. Analogous colors don’t usually stand out from each other; they seem to work together and can almost disappear together when overlaid.

Complementary: Complementary colors are opposite each other on the color wheel. Complementary color combinations are high in contrast and normally very vibrant, so use with caution. When overused, complementary color can be very “loud” and can easily cross over into visually obnoxious if you’re not careful. You can remember this rule with the alliterative phrase “Complementary colors create contrast.”

If you want to explore color combinations, visit http://color.adobe.com and explore the Adobe Color CC website (Figure 7.30). It’s an amazing way to browse other people’s color collections, or grab colors from an image you like and create a color set to use for your projects. When you register with your free Adobe ID, you can save the color themes you find or create and bring them into your Adobe apps to use and share with others.

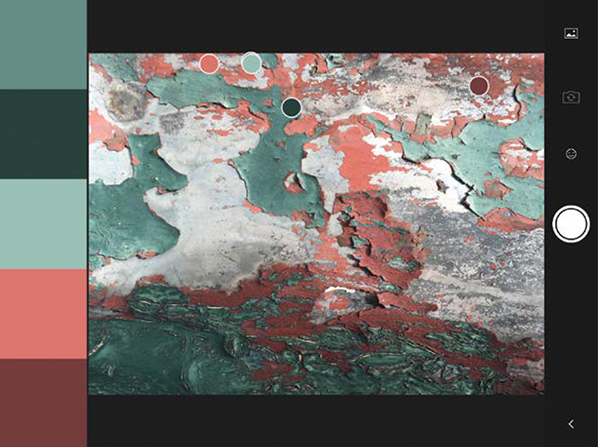

Adobe Color is also part of a free app for iOS and Android. Open the Adobe Capture CC app (Figure 7.31) and select Colors, open an image or point your phone camera at something, and create a color theme. Experiment with creating custom themes from your favorite blanket, a sunset, your goldfish, or your crazy uncle’s tie-dyed concert shirt from Woodstock.

Color Associations

We tend to associate different things with different colors. As a designer you must learn to recognize and properly use the right color for the message you want to convey. Again, this isn’t a science, and you’ll need to consider more than this chart when developing your color-picking strategies. But understanding colors and their associations (Figure 7.32) can be useful to produce the right “feel” in your images. You can evoke interesting feelings and contrasts by capitalizing on these associations in your interactive design work.

The Element of Type

Type (Figure 7.33) is generally not considered a traditional element of art, but it can be a critical part of your work as a designer. Typefaces carry a lot of emotional meaning, and choosing the proper typefaces for a job is a skill that every designer needs (yet many don’t have). Like color, this area of design is so deep and has so many aspects that entire books and college courses are focused only on typography. We can’t reduce it to simple rules such as “Use three typefaces, maximum. When in doubt, use Helvetica. And never use Chiller.” (Even though that’s not a bad starting point!)

![]() ACA Objective 1.5b

ACA Objective 1.5b

Working with type is often like being a marriage counselor or matchmaker. Every typeface has a personality, and you need to carefully match the type in your design work so it has a compatible relationship with the overall feeling of the piece. The typefaces you use also need to work together. It takes time and experience to master this balance, but over time you can become a skillful typeface matchmaker. Most artists have a few fonts they tend to lean on heavily, and that’s okay—especially at the beginning.

![]() Video 7.12

Video 7.12

Design School: The Element of Type

Tip

Check online at www.brainbuffet.com/design/typography for a list of fonts and typography-based resources to help you dig a little deeper with this concept.

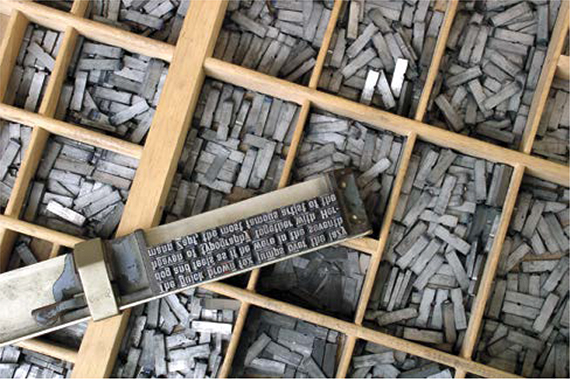

Typography

Typography is the art of using letterforms and type arrangement to help the language communicate a message. As mentioned, type can be its own topic of study and can easily get overwhelming. We skim the surface here but hope that as you move forward in your design, you’ll dig a little deeper. Let’s get some vocabulary out of the way first.

Technically, a typeface (Figure 7.34) is the letterform set that makes up the type. Helvetica, Arial, Garamond, and Chiller are examples of typefaces. In brief, it’s the “look” of the letters. A font is a specific collection of characters from the typeface in each of its sizes and styles. So 12 pt. Arial Narrow and 12 pt. Arial Bold are different fonts of the same typeface. The same is true for two different sizes of the same typeface.

Font files for your computer generally contain all sizes of a particular typeface in a single style, like bold, italic, or condensed. Having a set of font files that have multiple styles is often called having a “font family” for that particular typeface.

From now on, let’s use the term font, because that’s also the name of the file you’ll install when you add typefaces to your computer, and it’s the most common term. Few people will bother splitting hairs in these differences, which really don’t exist anymore for computer-generated type.

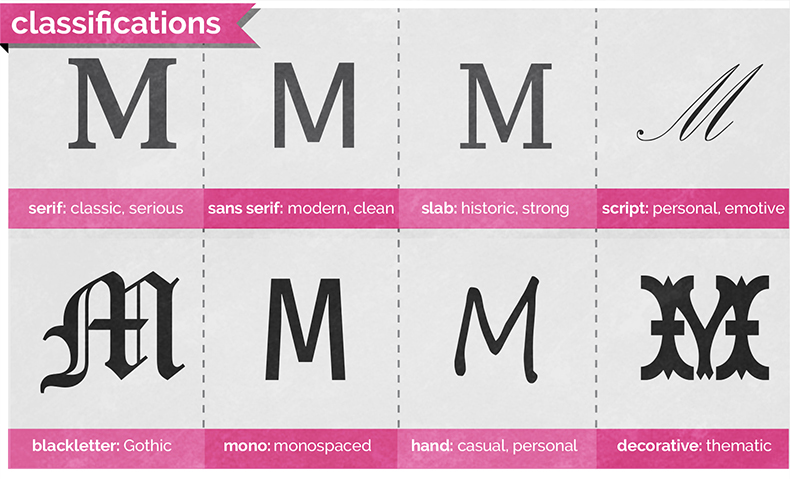

Type Classifications

There are many different ways to classify typefaces, but we’ll rely on the Adobe Typekit classifications for the purposes of this chapter. Generally, people divide fonts into two main categories of type that should be used for large areas of type: serif and sans serif (Figure 7.35).

Serif fonts are often associated with typewritten documents and most printed books. Generally, serif fonts are considered to be easier to read in larger paragraphs of text. Because so many books use serif fonts and early typewriters produced them, serif text often feels a bit more traditional, intelligent, and classy.

Sans serif fonts do not include serifs. Sans is a French word that migrated to English and simply means “without.” Sans serif fonts are often used for headlines and titles for their strong, stable, modern feel. Sans serif fonts are also preferred for large areas of text for reading on websites and screen reading.

Beyond these basic types of text we use in our documents, designers use other typefaces that are not appropriate for large areas of type because they’re not easy to read in a long paragraph. Most designers consider the following fonts to be “decorative” for that reason.

Slab serif fonts (also called Egyptian, block serif, or square serif) are a more squared-off version of a typical serif font. These fonts bridge the gap between serif and sans serif fonts and generally feel a bit more machine-built. The simple design tends to make them feel a bit rougher than their serif counterparts.

Script fonts (also called formal or calligraphical) have an elegant feeling. These fonts are great to use for invitations to formal events, such as weddings, and in designs where you want to convey a feeling of beauty, grace, or feminine dignity. If you are designing for a spa, for a beauty shop, or for products or services, script fonts will carry a feeling of relaxed and elegant beauty.

Blackletter fonts (also called Old English, Gothic, or textura) feature an overly ornate style and are often used to title formal documents such as certificates, diplomas, or degrees, as well as by old German Bibles and heavy metal bands. It conveys a feeling of rich and sophisticated gravitas, often hinting at a long history of tradition and reliability.

Monospaced fonts (also called fixed-width or nonproportional) use the same amount of horizontal space for each letter. Typically, fonts use a variable spacing technique called kerning. (You’ll learn more about kerning later in this chapter.) Monospaced fonts, in contrast, use the same width for every character. Monospaced fonts are good to use when you’re trying to make something look impersonal, machine-generated, or retro-geeky because typewriters and early computers used monospaced fonts.

Handwritten fonts (also called hand fonts) simulate handwriting. They are popular for adding a personalized, casual, or human touch to your designs and are often used on junk mail to try to trick you into opening that “Special limited time offer just for you!” (don’t fall for it). Handwritten fonts are prefect for communicating casual and friendly feelings, but they can be tough to read in a larger block of text.

Tip

Want to create a font based on your own handwriting? Go to www.calligraphr.com to create a font from your handwriting for free.

Note

Each character of a font, whether it’s a letter, number, symbol, or swash, is called a glyph.

Decorative fonts (also called ornamental, novelty, or display) don’t fall into any of the other categories. They also tend to convey specific feelings. Decorative fonts should be used sparingly and intentionally. Never use a novelty font just because you think it looks cool; that’s a typical newbie move. Make sure you are striving to convey something specific when using decorative fonts.

Dingbat fonts (also called wingdings) are a special type of font that doesn’t have an alphabet but instead consists of a collection of shapes or objects.

Type Talk

You’ll need to learn a lot of jargon concerning type when working in the design industry. Some of it is commonly used in discussion about design, and some of it will help you discuss fonts when you’re trying to find the perfect typeface for your design.

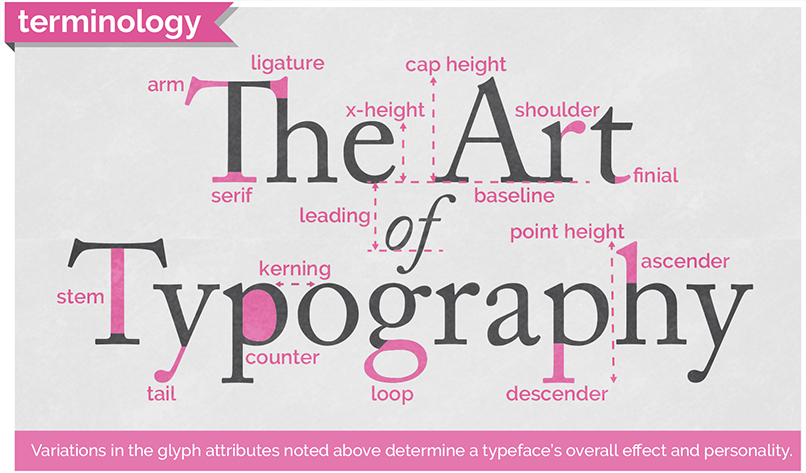

Typographic Anatomy

Figure 7.36 illustrates many of the terms used when discussing typography. Software has no settings for these options, so we won’t go into detail about them. When you start to study typography and learn these terms, you will more easily discern the differences between typefaces. It’s easiest to understand these terms by simply looking at the illustration. You will hear these terms in the industry, and when you’re looking for a specific font, knowing these terms will allow you to more easily describe what you’re looking for. Let’s face it: You can’t get too far professionally if you’re always using words like “doohickey” and “little hangy-downy thingy.” These terms are descriptive, like ascenders and descenders; anthropomorphic, like arms, shoulders, and tails; or architectural, like counters and finials.

The Holy Trinity of Typography

Three main concepts of typography exist: kerning, leading, and tracking, known as “the trinity of typography” (Figure 7.37). As a designer, you need to master these concepts. The terms defined here affect the ways that the letters are spaced from each other vertically or horizontally.

Kerning is the space between specific letter pairs. For example, the first two letters in the word “Too” are closer than the first two letters in the word “The” because the letter “o” can tuck under the crossbar of the “T.” A high-quality font file will have a good set of kerning pairs for specific letter combinations, but for some professional work (and with poorly designed fonts) you might need to get in there and tweak the kerning. Adjusting the kerning between specific letters can help you perfect your type presentation in logos and headlines.

Tracking is the overall space between all the letters in a block of text. It allows you to compress or expand the space between the letters as a whole, rather than just between specific pairs, as you do with kerning. Adjusting tracking can greatly affect the feeling that text conveys. Experiment with tracking to help create various feelings in headlines and titles.

Leading is the amount of space between the baselines of two lines of text. The baseline is the imaginary line that text sits on. Whereas word processing applications tend to limit you to single and double-line spacing, professional design software lets you manipulate the leading to set a specific distance between multiple lines of text. Doing so can create great-looking space in a design or even overlap with your paragraph text. Experiment with this option in your work. You can change the mood of text by adjusting only the leading of a paragraph.

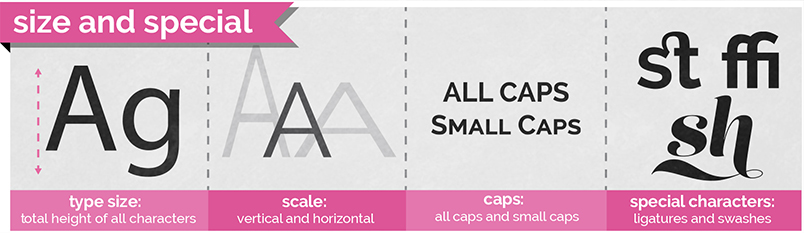

Size, Scale, and Small Caps

The terms that appear in Figure 7.38 are available in the Character panel of the interface for most Adobe design applications.

Type size is traditionally the height from the highest ascender to the lowest descender in a font, expressed in points (1/72 of an inch). Today, it’s more of a guideline than a firm definition, so most designers set the appropriate type size by eye. Different fonts of the same point size can appear to be much different in physical size if the ascenders and descenders are different from each other.

Tip

Higher-end typefaces may provide a small caps face that is much nicer than using the setting in software. If this is critical for your design, look for a font that supports this feature.

Note

To enable or disable the use of ligatures for text in InDesign, select the text and then select or deselect the Ligatures setting in the Character panel menu.

Note

To access swash alternates for selected text in InDesign, choose Type > Glyphs. Select the letter in the text to replace, and then in the Glyphs panel click and hold the mouse pointer on the letter to see if a swash replacement is available. In InDesign CC (2018), alternate glyphs appear as a context menu when you select text.

Vertical and horizontal scale are terms that describe the function of stretching letters and distorting the typeface geometry. Because they distort the typeface, use them with caution. They should be used only when you are trying to express a specific feeling and should not be used in blocks of type, because readability can suffer with either of these adjustments.

All caps and small caps are similar in that they both use only the uppercase letterforms for each letter, but ALL CAPS makes all the letters the same size, whereas small caps sets capital letters at the size of a lowercase letter such as “o”. Small caps tend to increase readability compared to all caps, but both cap formats should be avoided in large blocks of text because they are more difficult to read than standard text.

Ligatures and swashes are special alternative settings offered with some fonts to combine letters or add stylized touches to certain letter combinations or letters. For example, when the “Th” combination touches in a headline, you can replace it with a single ligature that looks much better. Swashes add flowing and elegant endings to letters with ascenders and descenders. Both of these are normally reserved for type that is expressing an especially elegant or artistic feel.

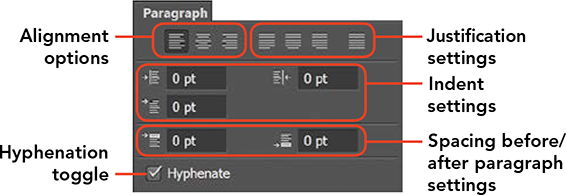

Paragraph Settings

Paragraph settings affect an entire paragraph rather than selected words (Figure 7.39). These options adjust the alignment of the paragraph: left, centered, or right. Justified text aligns a straight edge on both edges of the paragraph with the ability to dictate how the last line is aligned. Indent settings let you choose how far the entire paragraph is indented on each side or in just its first line. Paragraph spacing settings are similar to leading but apply to paragraphs—instead of lines of type within them—and you also can set the space above or below paragraphs. Hyphenation allows you to determine if and when words should be split with hyphenation.

Wrapping Up the Elements

As you’ve seen in this chapter, the elements are the building blocks or the raw materials of design. But what turns these elements into art is applying the principles of design to the way you arrange these elements on your workspace. In the next section, you’ll explore these principles, which are a framework that help you arrange your work in an artistic way.

The Principles of Design

![]() ACA Objective 1.5a

ACA Objective 1.5a

![]() Video 7.13

Video 7.13

Design School: The Principles of Design

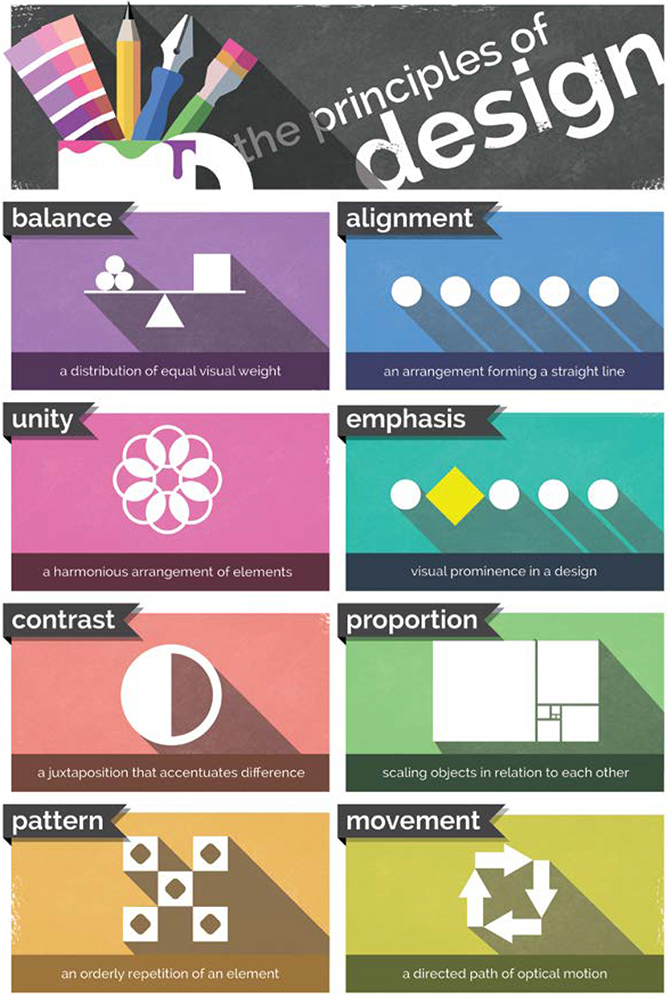

Much as with the elements of design, different artists and schools of thought will generate different ideas about what makes up the principles of design (Figure 7.40). For a young artist, this can be frustrating. Sometimes you just want someone to tell you the answer.

But after you understand the principles, you’ll appreciate that no one can point to a universal list of artistic principles. If there’s no correct answer, there’s also no wrong answer either. Creatively, you always have another way to approach your art, and becoming an artist doesn’t mean that you learn to see any one approach. Becoming an artist means that you learn to see.

Until you explore design principles, you will not be ready to understand them. Therefore, definitions are not as helpful as hands-on work. But truly grasping the principles and experiencing them is the only way to grow as an artist. This is the beginning of a lifelong exploration of beauty and creativity.

The bottom line is this: Don’t get hung up on names or descriptions. Try to engage with each idea as a loosely formed concept that remains fluid and flexible rather than defining boundaries. By studying principles, you’re trying to do just the opposite—move in directions that have no boundaries. The goal of all good art and design is to explore new ways to use the elements and principles, and not to repeat what’s been done in the past. You’ll examine these principles to start your understanding of something, not to limit it.

The Principle of Emphasis, or Focal Point

![]() Video 7.14

Video 7.14

Design School: The Principle of Emphasis

Emphasis (Figure 7.41) describes the focal point to which the eye is naturally and initially drawn in a design. Some art has a focus that’s obvious. Most marketing and advertising is that way. Other art invites you to step in and explore. It might encourage an exploration of color or texture, but it has no specific point other than the color or texture.

Think of emphasis as the main point or primary idea in a piece of art. You can move the viewer’s eye to a specific point in the design by making something different. You can easily find examples right on the pages of this book. Chapter headings are larger than the rest of the type. Glossary terms are a different color. Even the simple process of italicizing words or putting them in boldface makes text stand out. The human eye is naturally drawn to unique things. If you want to make something stand out, make it different.

Careful use of contrast is critical to master because a typical design newbie tries to make everything special and unique. As a result, nothing stands out. The design looks random, not cool. Give a piece some unity, and it will feel right. You can then emphasize what’s truly important.

The Principle of Contrast

![]() Video 7.15

Video 7.15

Design School: The Principle of Contrast

Contrast generally creates visual interest and a focal point in a composition. If you think about it, a blank canvas is a canvas with no contrast. As soon as you begin to alter the surface and create contrast, you also start to create a focus. The principle of contrast can be defined as a difference in the qualities of the elements in an image. To use contrast is to create something different from the surrounding pieces of the composition.

Many artists limit their understanding of contrast by confining it to color or value. But contrast is much more than that. Any difference between one thing and another creates contrast. You can have contrast in size, texture, value, color, or any of the defining characteristics you learned about in exploring the elements.

The most important thing to remember about contrast is that all contrast creates some emphasis, and if you have too much emphasis, you will have no focal point.

The Principle of Unity

![]() Video 7.16

Video 7.16

Design School: The Principle of Unity

Unity generally communicates calm, peaceful, or cool feelings in your art. The principle of unity (also called harmony) requires that the things that go together should look like they belong together (Figure 7.42). The elements in your design should feel like a family. This doesn’t necessarily mean that everything needs to be the same, just that they should share some similar traits. When you have no unity, you can have no focal point and, therefore, no emphasis.

Note the headings of the different sections in this chapter. They make it easy to find the content you are looking for when skimming the book. Even the breaks between paragraphs help distinguish one concept from another. But all of the words in this paragraph belong together because they share a unity of typeface, spacing, color, and so on.

Unity is important in your compositions so that when you create contrast it draws the viewer’s eye where you want it to go. In design, more than in art, we are interested in guiding a viewer’s perceptions. Design generally tends to be much more intentional than art. Both are important, however, and beginning with design can make your experimentation with artistic elements and principles much more effective and productive.

The Principle of Variety

![]() Video 7.17

Video 7.17

Design School: The Principle of Variety

Variety tends to communicate energy, heat, and high emotion in a design. When applying the principle of variety, you use different elements in an image to create visual interest. In many ways, it is the exact opposite of unity. You can think of unity and variety as being at the opposite ends of contrast. Unity is establishing a low degree of contrast in a composition. Variety does the opposite and brings a higher amount of contrast to the composition.

Variety is a principle that normally needs to be used sparingly. Too much variety quickly moves your art from interesting to chaotic and disorganized (Figure 7.43). Beginning artists and designers sometimes have a hard time properly using variety. They get a bit carried away and lose all sense of focus or unity. Beware of that tendency!

The Principle of Balance

![]() Video 7.18

Video 7.18

Design School: The Principle of Balance

Balance suggests that the arrangement of things in an image should not be evenly distributed. This is not to say that everything should be centered, or that placing something in the top right means you should mirror it with something similar in the top left. That’s how a nondesigner lays out a composition. Experienced artists learn to properly balance all the elements—including space—in their compositions.

Tip

Many artists and designers characterize pieces that are out of balance as “leaning to the left,” “leaning to the right,” or “top-heavy.” Over time, you’ll develop these feelings too and be able to spot when art seems like it might physically tip over.

Balance comes in many forms; three examples are symmetrical, asymmetrical, and radial balance.

Symmetrical: Symmetrical balance is what most students latch on to at first. It occurs when you can divide an image along its middle and the left side of the image is a mirror image of its right (or the top reflects the bottom). Using a seesaw analogy, a symmetrical balance would have two equally sized people equally distant from the fulcrum. This is the easiest balance to execute, but it conveys a very intentional, formal, and mechanical feeling.

Asymmetrical: Asymmetrical balance (Figure 7.44) achieves balance with different elements on each side (or the top and bottom) of an image. Imagine an adult on a seesaw with a child. They can balance, but only if the adult is closer to the fulcrum and the child is farther away. To achieve asymmetrical balance, you need to use space to counterbalance the different weights on each side.

Figure 7.44 This image, though asymmetrical, is well balanced. The bright sun is offset by the visual weight of the rocks in the lower right. Radial: Radial balance (Figure 7.45) is a circular type of balance that radiates from the center instead of the middle of a design. Many artists get the feeling that they’re viewing a radially balanced image from above. This kind of balance is almost always circular. An excellent example of radial balance is a kaleidoscopic image, which can feel balanced and unified but also typically feels more static than the other types of balance.

Figure 7.45 This image has a radial balance.

The Principle of Proportion or Scale

![]() Video 7.19

Video 7.19

Design School: The Principle of Proportion or Scale

Proportion, sometimes called scale, describes the relative sizes and scale of things. If you’ve ever seen a drawing and observed that “the head is too small” or “the body is too fat,” you’re evaluating the proportion. It’s simply the sense that things seem to be the proper size relative to each other.

You can manipulate proportion and scale to create emphasis. Things that are larger than they should be appear stronger, more important, or more powerful. Take the chapter headings in this book. By making the headings disproportionately large, we’ve indicated importance and emphasis. You can also reduce the perceived value, strength, or importance of something by reducing its scale.

The Principles of Repetition and Pattern

![]() Video 7.20

Video 7.20

Design School: The Principles of Repetition and Pattern

The two principles of repetition and pattern—along with movement and rhythm—seem to be the most confusing and difficult to grasp. As a matter of fact, some artists and writers more readily connect pattern and repetition with rhythm than with movement. In this introductory look at these concepts, think about the simplest and most concrete uses of them here. As always, you’re encouraged to explore these areas much more deeply on your own.

Repetition is a principle that is pretty easy to grasp: repeating an element in your design. Repetition can convey many things, but it often represents importance, movement, or energy. Think of an illustration of a ball moving or a cartoon of a bird flapping its wings. Just repeating a few lines can convey a sense of motion.

Pattern happens when different objects repeat in a sequence. The best way to think about the difference between repetition and pattern is that repetition is done with a single element (such as pinstripes on a suit), whereas pattern happens with a collection of elements (such as a floral pattern on fabric). Pattern also happens when elements are repeated consistently and, at some point, eventually move past repetition and become a pattern.

Another important way to think about repetition is to share certain traits of the elements in your design. Doing so brings some unity to those elements and lets the viewer know they’re related. For example, you could repeat the colors of the logo in headers and bold type or repeat the same colors from a photo into the header text of an associated article in a magazine. Repetition of this kind conveys a sense of unity in the design.

The Principles of Movement and Rhythm

![]() Video 7.21

Video 7.21

Design School: The Principles of Movement and Rhythm

Movement and rhythm are similar, much as repetition and pattern are. They modify an image much the way an adverb modifies an adjective. They explain a feeling that the elements create, rather than making specific changes to the elements.

Movement refers to the visual movement in an image. Depending on the context, it can refer to the movement the eye naturally follows across an image as it moves from focal point to focal point, or the perceived movement or flow of the elements in the image.

Movement can also refer to the “flow” of an image and is a critical principle to consider in your work. It’s more a feeling than a concrete visual aspect of your design. When something “doesn’t feel right,” it may be that the flow is uncertain or contradictory. If you haven’t considered the flow of your design, analyze it and create a flow that guides the viewer through your design. The more linear your flow, the more your design will convey a sense of reliability, consistency, and calm. A more complex flow can convey a sense of creativity, freedom, or even chaos.

Rhythm refers to the visual “beat” in the design, a sense of an irregular but predictable pattern. Just as a rhythm is laid down by a drummer, a design’s rhythm is creative and expressive, rather than a consistent pattern or repetition. Depending on the design you’re working on, rhythm may or may not be a critical principle to consider. A predictable rhythm can convey a sense of calm and consistency, whereas an erratic or complex rhythm can convey a sense of urgency or energy.

These two principles tend to be the most subjective, so be sure to clarify anything you’re unsure about when discussing these principles with a client. Because they’re more a feeling than a specific element or technique, it takes a little experience to get a handle on them. But these are just like all of the principles; once you start looking for them, you’ll start to see them.

Wrapping Up the Design Concepts

![]() Video 7.22

Video 7.22

Design School: Wrapping Up Design School

As a visual designer, you must understand the elements and principles so that your work can communicate clearly to your audience. Learning the technical basics of InDesign is fairly easy, and they can be mastered by people who will never “make it” in the industry.

Take the time to develop your design skillset and to remember that it is a skillset. You’ve got to practice and continue to develop your craft to level up those skills. Using InDesign without having a design sense is like starting up a jet airplane without a pilot. It’s powerful, but it won’t have a path or a destination. The artistic elements and principles are the wings and controls that let you harness that power and get your art to go where you want it.

Invest the time and effort to practice and refine your design sense. You’ll find that your personal art not only grows more impressive over time, but that the entire world opens up and becomes much more interesting, beautiful, and detailed.

InDesign is about learning to create visual designs with exceptionally high quality and detail, but becoming an artist and refining your skills is about learning to see.

Open your eyes… and enjoy the beauty you’ve been missing that’s all around you!

Tip

Connect with us at www.brainbuffet.com/design to see our ever-growing collection of design-related resources, or follow us on Twitter at @brainbuffet for weekly resources, inspiration, and freebies to use with your design projects.