Appendix H. Cheat Sheet

By popular demand, this “cheat sheet” is loosely based on the little recap/summary boxes from the end of each chapter. The idea is to provide a few reminders, and links to the chapters where you can find out more to jog your memory. I hope you find it useful!

Initial Project Setup

-

Start with a User Story and map it to a first functional test.

-

Pick a test framework—

unittestis fine, and options likepy.test,nose, orGreencan also offer some advantages. -

Run the functional test and see your first expected failure.

-

Pick a web framework such as Django, and find out how to run unit tests against it.

-

Create your first unit test to address the current FT failure, and see it fail.

-

Do your first commit to a VCS like Git.

The Basic TDD Workflow

-

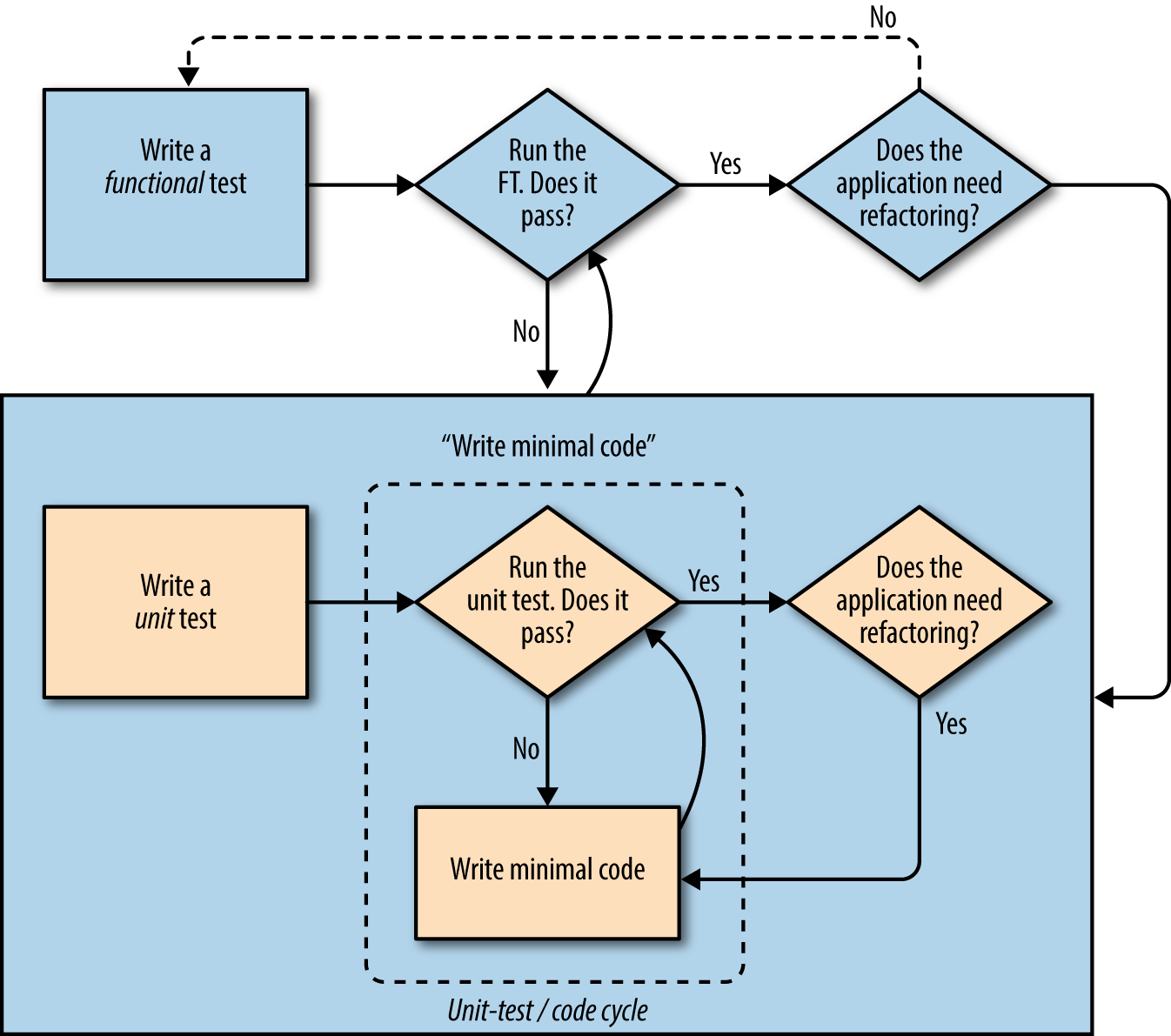

Double-loop TDD (Figure H-1)

-

Red, Green, Refactor

-

Triangulation

-

The scratchpad

-

“3 Strikes and Refactor”

-

“Working State to Working State”

-

“YAGNI”

Figure H-1. The TDD process with functional and unit tests

Moving Beyond Dev-Only Testing

-

Start system testing early. Ensure your components work together: web server, static content, database.

-

Build a staging environment to match your production environment, and run your FT suite against it.

-

Automate your staging and production environments:

-

PaaS vs. VPS

-

Fabric

-

Configuration management (Chef, Puppet, Salt, Ansible)

-

Vagrant

-

-

Think through deployment pain points: the database, static files, dependencies, how to customise settings, and so on.

-

Build a CI server as soon as possible, so that you don’t have to rely on self-discipline to see the tests run.

Relevant chapters: Chapter 9, Chapter 11, Chapter 24, Appendix C

General Testing Best Practices

-

One test file per application code source file.

-

Consider at least a placeholder test for every function and class, no matter how simple.

-

“Don’t test constants”.

-

Try to test behaviour rather than implementation.

-

Try to think beyond the charmed path through the code, and think through edge cases and error cases.

Relevant chapters: Chapter 4, Chapter 13, Chapter 14

Selenium/Functional Testing Best Practices

-

Use explicit rather than implicit waits, and the interaction/wait pattern.

-

Avoid duplication of test code—helper methods in a base class and the Page pattern are possible solutions.

-

Avoid double-testing functionality. If you have a test that covers a time-consuming process (e.g., login), consider ways of skipping it in other tests (but be aware of unexpected interactions between seemingly unrelated bits of functionality).

-

Look into BDD tools as another way of structuring your FTs.

Relevant chapters: Chapter 21, Chapter 24, Chapter 25

Outside-In, Test Isolation Versus Integrated Tests, and Mocking

Remember the reasons we write tests in the first place:

-

To ensure correctness and prevent regressions

-

To help us to write clean, maintainable code

-

To enable a fast, productive workflow

And with those objectives in mind, think of different types of tests, and the trade-offs between them:

- Functional tests

-

-

Provide the best guarantee that your application really works correctly, from the point of view of the user

-

But: it’s a slower feedback cycle

-

And they don’t necessarily help you write clean code

-

- Integrated tests (reliant on, for example, the ORM or the Django Test Client)

-

-

Are quick to write

-

Are easy to understand

-

Will warn you of any integration issues

-

But: may not always drive good design (that’s up to you!)

-

And are usually slower than isolated tests

-

- Isolated (“mocky”) tests

-

-

Involve the most hard work

-

Can be harder to read and understand

-

But: are the best ones for guiding you towards better design

-

And run the fastest

-

If you do find yourself writing tests with lots of mocks, and they feel painful, remember “listen to your tests”—ugly, mocky tests may be trying to tell you that your code could be simplified.

Relevant chapters: Chapter 22, Chapter 23, Chapter 26