10

Unlearning Incentives

The iron rule of nature is: You get what you reward for.

—Charlie Munger

I can vividly remember the day not that long ago when I had the opportunity to sit in on an executive strategy team meeting of one of the world’s largest banks. I was invited to give my perspective on the necessary conditions for creating high-performing organizations, specifically the required leadership mindset and behaviors, and compare and contrast it with what the bank was doing. The meeting ran two hours, but the first 90 minutes or so were devoted to the attendees trying to outdo one another in terms of how well their businesses were performing, and the exceptional figures they were getting—evidenced by their perfect records and positive indicators of success.

There was a shift during the last 30 minutes of the meeting, however, when the attendees started to discuss topics of interest to the company as a whole—specifically, what was the bank’s purpose, where they should go in the future, and how they could improve the ways in which they worked together.

The room went quiet for a minute, and then the person responsible for the largest individual component of the bank spoke up. “Basically,” the executive said, “we’re designed as a business to compete against one another, and the side effect of this design is that we don’t share information with one another. We constantly look for opportunities to improve our individual businesses instead of working together to improve the overall performance of the bank.”

It was true. This high-power team of executives would never be able to move the entire organization in the direction they wanted if they kept optimizing just for themselves. To be even more successful as an organization, these executives would need to stop doing what had brought them individual success in the past and start doing what would bring the bank success in the future.

While that’s all well and good, the realization and admission on the part of the executive leadership team was illuminating. It brings us to the heart of a question that would determine their ultimate success: What are the incentives driving these financial executives to change the way they work and their own behavior?

The big question (and challenge) for executives is what motivates and enables them to take the risk, to innovate, or to unlearn what has brought them success in the past? Most executives are measured on very specific business outputs and financial metrics, and if they can demonstrate a percentage point more effectiveness or more efficiency, they’re guaranteed to get their big bonus payouts. If that’s the case (and it often is), then why would any executive take a course of action that is uncertain, risky, or unknown—even if the payoff was 25 percent or greater effectiveness or efficiency?

In this situation, what would you do?

Leaders in most organizations today are massively incentivized to do what they’ve always done and squeeze a little bit more out of the existing system, versus taking a risk and unlearning what has delivered past success. When you pair up this reality with how executives are conditioned to compete with one another, which doesn’t foster collaboration across the organization, this leads to a tremendous gap between potential performance and the performance that is actually experienced in organizations.

I’m reminded of what former General Electric CEO Jack Welch once said: “Any jerk can have short-term earnings. You squeeze, squeeze, squeeze, and the company sinks five years later.”1 The incentives in most organizations favor short-termism, local optimization, and what’s easy to measure—practices that work against long-term success. In this chapter, I concentrate on unlearning incentives by exploring how to move the focus from individual outputs that benefit just a limited number of people or departments, to system-level outcomes that benefit the entire organization.

Incentives and Unlearning

How do people let go of what has made them successful in the past to find extraordinary results in the future? One of the reasons people get trapped doing the same things they’ve always done is because of organizational incentives that drive their behaviors. These incentives are often financial in nature, including pay raises and bonuses. Research shows, however, that relying on pay for performance may actually drive negative behaviors and disincentivize people from modifying what they do.2

Consider the example of a CEO and other executives who run a company. A significant portion—likely the majority—of the executives’ incentive structure is based on the performance of the company. If the stock price goes up or profitability increases, executives will get big bonuses. So immediately, their minds go straight to their bonuses and not on doing what is necessary to create an exceptional company or a great place to work.

If you create a contingent relationship with your employees based on rewards by saying, “If you do this, you will get that,” then they will have a natural tendency to focus on the “get that” part of the equation. If, for example, you tell managers that they will get a bonus for reducing operating costs, then the managers will put their full focus on taking costs out of the system, perhaps even to the detriment of the overall organization and its long-term growth prospects. And as the magnitude of the “get that” increases—as bonuses rise into the tens and hundreds of thousands of dollars—then executives and other employees will do whatever it takes to earn them.

Research shows that the percentage of company payrolls dedicated to bonuses versus pay raises has increased considerably since 1991, when 5 percent of company payrolls was devoted to raises and 3.1 percent to bonuses. As of 2017, this figure had increased to just 2.9 percent of company payrolls devoted to raises, and 12.7 percent to bonuses.3 However, these figures don’t reveal the full extent of the problem with bonuses and the contingent relationships companies create with their top executives. According to an article in Fortune, 90 percent of CEOs’ total pay is composed of performance bonuses, including long-term incentive pay—leaving just 10 percent to CEOs’ salary. As of 2014, the median of these CEO bonus payouts was $7.1 million—up 6 percent from the year before.4 Median CEO pay for the 100 largest companies reached a record $15.7 million in 2017.5

With this much at stake, which outcomes will CEOs naturally put their greatest focus on? The risky ones that could jeopardize their bonuses, or the status quo of past success they are certain will guarantee they will “get that”? What would you do?

When the stakes and rewards are this high, leaders are faced with two options: Do I stick with what’s known that has brought me results in the past, and then squeeze the system to get the 1 or 2 percent more that I need to guarantee my bonus? Or do I be courageous, embrace uncertainty, and unlearn? Do I do something different that I’ve never done before with the potential upside of extraordinary results—or the potential downside of massive failure? Inevitably, 99 times out of 100, they choose to stick with what they’ve always done. Indeed, the companies these men and women work for get what they reward.

Existing incentive structures are one of the biggest inhibitors for driving innovation in any organization. Leaders think they’ve designed them to lead innovation in the company, but they actually have the reverse effect. They provide rewards at the individual level while extracting systemic-level costs.

It’s time to unlearn individual pay-for-performance incentives and relearn to create the conditions for authentic motivation, courageous behaviors, and exploring risky initiatives in a controlled manner to get the breakthroughs to achieve extraordinary results. The strategy is that you don’t suddenly change everything you’re doing and work in a new way. Think big but start small. Pick one or two initiatives in your portfolio that you can experiment with in a safe-to-fail manner. Instead of betting the farm, you’re placing a $1 bet on a new way of recognizing people and their contributions. When you start to see the benefits of those small experiments, that evidence will encourage you to take on more audacious experiments, uncertainty, and risks.

Breakthroughs Happen When You Align Effort to Outcomes

Another problem leaders often encounter is measuring the output of individuals without tying their performance to—and making visible their contribution toward—the system-level outcome. Leaders need to define a system-level outcome, a purpose, and a mission that people can believe in, clearly understand, and are motivated to achieve. Then they must ensure that individuals can see alignment with what they want to achieve, their contribution, and the system-level outcomes they are impacting.

Providing clarity of system-level outcomes, helping people get started, and then providing support along the way is the responsibility of leadership. All too often, companies aren’t clear about what the purpose of the business is or the mission to achieve, and employees aren’t clear how their contribution ties to either.

At Netflix, the key role of leadership was to make sure everybody clearly understood what were the top priorities of the organization at any given time. They then encouraged people to do what they believed would be most effective in achieving those very clear objectives that the entire company was working toward.

In her book Powerful: Building a Culture of Freedom and Accountability, Patty McCord—who served as the chief talent officer at Netflix—explains that her litmus test was being able to stop any of the company’s employees, at any level of the company, in a break room or elevator and ask them this question: “What are the five most important things the company’s working on for the next six months?” If they couldn’t reel them off one, two, three, four, five, ideally using the same words used in communications to the staff, then Patty knew that Netflix leadership was failing to do its job, not the individual.

If people don’t understand or are not clear on the intent of the company, they can never move toward it. And if you don’t incentivize people to achieve the intent and measure that as success, then they will optimize for other objectives, the easy-to-measure incentives that are attainable to them but not necessarily the intent of the company.

The majority of people are measured on their activity, not what they contribute to system-level outcomes. This occurs because individual activities are much easier to measure. Companies and managers often claim that it’s too hard to measure system-level outcomes, so they don’t—or they communicate them poorly while failing to ensure the alignment of work to these system-level outcomes. The result is that people become disengaged from their work; they can’t see the outcomes they are affecting. They lack clarity about what they’re trying to achieve so everyone just does what they need to do to guarantee the “get that” side of the contingent equation—the outputs that are easiest to measure for which they will be rewarded. Leaders must unlearn that hard-to-measure outcomes are rarely achieved by completing only easy-to-measure tasks.

People want to have a sense of contributing to the greater good—of their organizations, their communities, and the world at large. Employees are most satisfied in their work when there is a strong link between what they do and compelling system-level outcomes they’re contributing toward. When the link is weak or absent, then motivation and performance are sure to suffer.

The Science of Incentives

One of the grand challenges of leaders everywhere is: How do you motivate people to do what you want them to do—especially if it is something they don’t wish to do? As you know from Behavior Design, everyone is different, and different behaviors motivate different people in different, often unintended ways.

It’s evident there is a fundamental disconnect and behavior matching problem within organizations. According to the 2017 Gallup State of the Workplace report, 85 percent of employees globally are either actively disengaged (18 percent) or not engaged (67 percent) at work. Says Gallup, “This latter group makes up the majority of the workforce—they are not your worst performers, but they are indifferent to your organization. They give you their time, but not their best effort nor their best ideas. They likely come to work wanting to make a difference—but nobody has ever asked them to use their strengths to make the organization better.”

What is the result from all this lack of employee engagement in their work? A whopping $7 trillion in lost productivity globally.6 While a lack of engagement doesn’t explain the entirety of employee motivation issues (one can be engaged but not want to do something because one disagrees with it), I believe there is a connection.

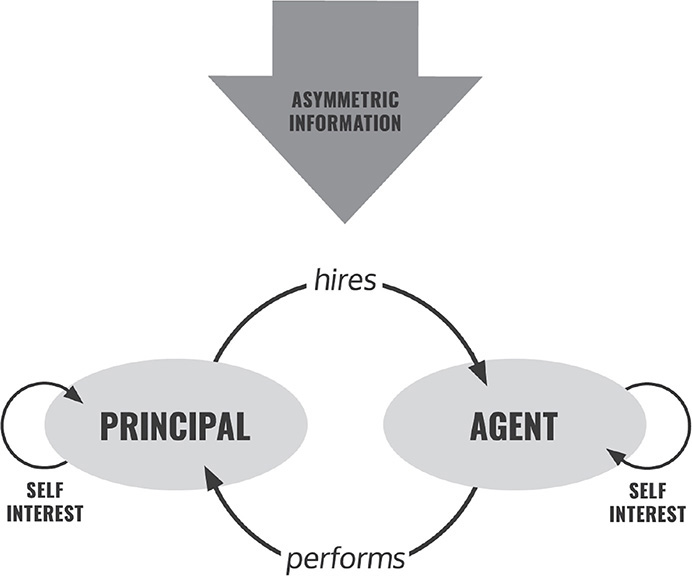

In 2016, MIT economist Bengt Holmström (along with Oliver Hart) received the Nobel Prize in Economics Sciences for his work in the field of contract theory, including addressing the “principal-agent” problem, which according to the Financial Times is “the problem of motivating one party (the agent) to act on behalf of another (the principal).”7 There are a variety of relationships where this problem can occur, including relationships between employees and managers, CEOs and shareholders, patients and doctors, and so forth (Figure 10.1).

FIGURE 10.1. The relationships between principal (P) and agent (A)8

As part of his work on contract theory, Holmström aimed to study, experience, and observe how the principal-agent model, the prevailing approach to incentives, thinks. His first discovery was that the model makes too many inferences based on the principal’s viewpoint of the agent’s performance. It asks, “How much does this performance show that the agent did what the principal wanted them to do?” The problem being that the principal rarely, if at all, sees what the agent actually does. If employees have a successful outcome, for example, then their manager believes they worked hard to achieve the desired outcome. If, however, employees have unsuccessful outcomes, then their manager believes that they didn’t work hard to achieve the desired outcome—they must not have been motivated or had the desire to succeed. The reality is many factors can impact outcomes. Customers might not want the product you created, an unexpected issue may arise, or you can be unlucky with timing.

People also don’t just produce effort. The work they do is multidimensional, and the time devoted to quality versus quantity of output ultimately determines performance. How people are incentivized determines in great part where they will focus their effort. But people struggle with measures that aren’t well aligned with the entire package of what is being incentivized, and they struggle with assessing hard-to-measure tasks.

Holmström identified and cautioned that when tasks get complex you shouldn’t zero in on one incentive. When people do, they focus on what’s easy to measure and not on what is hard to measure—which typically happens to be the desired outcome. We must incentivize hard-to-measure tasks that lead to desired system-level outcomes, not easy-to-measure tasks.

Attempts to improve performance by linking it to pay will not result in the desired outcomes. This leads to poor results, yet this is the prevailing approach in most organizations—an approach that has existed since the Industrial Era when managers walked around measuring outputs of work with their checklists, ticking the boxes for what each employee was doing. Many leaders today continue to hold on to this Industrial Era conditioning and mindset, which needs to be unlearned.

Consider the recent Wells Fargo scandal that resulted from employees being rewarded by the company for creating up to 3.5 million bogus accounts.9 The system-level outcome Wells Fargo was aiming for was better customer satisfaction and increased usage of their products and services. What’s one easy-to-measure indicator of that? The number of new accounts opened. The more accounts opened, the better the customer satisfaction must be, or so Wells Fargo’s executives thought.

The initiative was at first successful; but, when Wells Fargo employees ran out of real customers to open new accounts, they created fictitious customers and were rewarded by the company for it. That is, until this practice was revealed to the public.

When you optimize locally, create strong incentives based on pay for performance, and measure only the behaviors that are easy to measure, the focus turns toward the individual employee’s activity, not the system-level outcomes. You end up with unintended consequences and deviant behavior. In the case of Wells Fargo, the company paired an easy-to-measure “if this” (the number of new accounts) with bonuses (the “get that”) meant to increase productivity output. These bonuses caused employees to focus on the rewards, resulting in unintended consequences and greater risk, brand damage, and $185 million in fines.10

In his research, Holmström recommended when unlearning the principal-agent model for incentives and relearning a new system, consider the following questions.

“What if there were no incentives?” In cases where employees have clarity of purpose in their work, alignment on how their efforts contribute to achieving it and appreciation for their efforts are enough to prompt the desired behaviors.

“What if there needs to be an incentive?” When incentives are required to motivate an employee to work harder or perform a less satisfying or undesirable task, modest financial incentives such as a small bonus can have a significant effect. But not all incentives must be financial: You can offer personal development, career paths, family flexibility, and other nonfinancial rewards.

Holmström’s winning thesis framed how pay for performance doesn’t solve the incentive problem but is the problem. And the key first step to remedying the problem is a mix of easy-to-measure tasks along with hard-to-measure ones.

Relearning What People Really Want

Employees want to be appreciated, and companies actually have many instruments to make people feel appreciated and motivate them in their work, beginning with job design. 3M famously encouraged its technical employees to spend 15 percent of their time pursuing their own ideas, a remarkably progressive program that started in 1947. This practice resulted in a variety of product innovations for the company, including Post-it® Notes. Companies can provide career advancement opportunities, allow employees to work from home, offer open time off, and much more.

When incentives are done right, people feel appreciated and engaged in their work. When done wrong, employees put in the minimum amount of effort to get the most out of the incentive system. This only leads to negative outcomes for all parties and incentive theater.

A few years ago, researchers for employee engagement firm TINYpulse conducted a survey of more than 200,000 employees working for more than 500 organizations. Among other items, the survey asked respondents this question: “What motivates you to excel and go the extra mile at your organization?” The survey provided 10 possible answers, which rank as follows:

• Camaraderie, peer motivation (20 percent)

• Intrinsic desire to do a good job (17 percent)

• Feeling encouraged and recognized (13 percent)

• Having a real impact (10 percent)

• Growing professionally (8 percent)

• Meeting client/customer needs (8 percent)

• Money and benefits (7 percent)

• Positive supervisor/senior management (4 percent)

• Believing in the company/product (4 percent)

• Other (9 percent)11

As you can see, money and benefits ranked well below peer motivation, feeling encouraged and recognized, having a real impact, and professional growth.

Transforming Talent and Incentives at Capital One

Drew Firment is the former technology director of cloud engineering at Capital One and the current managing partner at A Cloud Guru. In his position at Capital One, Drew worked with executives and teams from each of Capital One’s distinct business groups across the enterprise—including card, retail, and commercial banking—on cloud adoption and talent transformation. Drew learned firsthand the power of incentives and creating systems that encourage employees to give their best by appreciating the outcomes of their efforts.

Capital One wanted to achieve a number of system-level outcomes, including faster delivery, less expensive operations, and increased product innovation. The company realized that these outcomes would best be achieved by utilizing the cloud. It was a strategic priority for founder and CEO, Richard Fairbank. Said Richard, “Increasingly, we’re focusing on cloud computing and building the underlying capabilities such that product development will be faster and more effective over time.”

For the cloud adoption program, the organizational strategy was to migrate Capital One’s systems from on-premises data centers to the public cloud as quickly as possible, in a manner that was well-architected, secure, and cost-efficient.

To make this happen, it would be necessary to translate the organization’s strategy to divisional objectives, then align with department plans, and finally drive individuals to the right actions and behaviors. It was critical to establish intent and a common answer to “Why does this matter?” and “What’s the opportunity for me?” for all parties.

When organizations want to achieve breakthroughs, they must first define the system-level outcomes the company is trying to achieve. Then they must communicate them clearly, ensure people understand them, and measure them (even if they are hard to measure). It’s vital to connect people’s individual efforts to the system-level outcomes they are aiming to achieve and show how they are contributing to them. The same is true with adopting new behaviors.

Drew points out that Capital One is loaded with ambitious Type A personalities and has a culture geared toward high performers and high achievers. But like that of many large enterprises, its performance management system was a barrier. With an annual review process tied directly to compensation, individuals were incentivized for the short term. Says Drew:

Although what really needs doing is things that are the long-term, hard-to-measure, system-level outcomes—a team is generally incentivized for what they’re going to deliver within the performance management cycle. When your compensation is tied to short-term objectives, you end up delivering short-term outcomes.

Drew knew that a focus on the short-term, easy-to-measure activities wasn’t going to lead to the long-term, system-level outcomes Capital One’s CEO identified: increasing the speed and effectiveness of product delivery to customers. This would require moving Capital One to the cloud and lead to another set of outcomes: improving the speed, quality, and cost of cloud migrations with an eye on the underlying individual talent transformation that fuels Capital One’s innovation.

Relearning the Definition of Success

During a pivotal leadership meeting, Drew was inspired to take action. It didn’t make sense to use an abstract maturity model to measure organizational performance and cloud adoption. Instead, the leadership team should be specific about what success looked like—based on three key outcomes set by Capital One’s CIO—and then measure it using the underlying audit trails available in the cloud. Even if it turned out to be hard to measure, they needed to be aligned to system-level success. It might not be perfect, but it would create a shared understanding of purpose, and where the organization and the people within it stood with regard to achieving their mission. According to Drew, the best system would provide:

a very clear destination, understanding your current position with real-time data, and directions that are consumable. You provide visibility with a dashboard and instrumentation that allow individuals and teams to self-assess if they’re on track or in need of repair. This helps to align individual efforts to organizational outcomes.

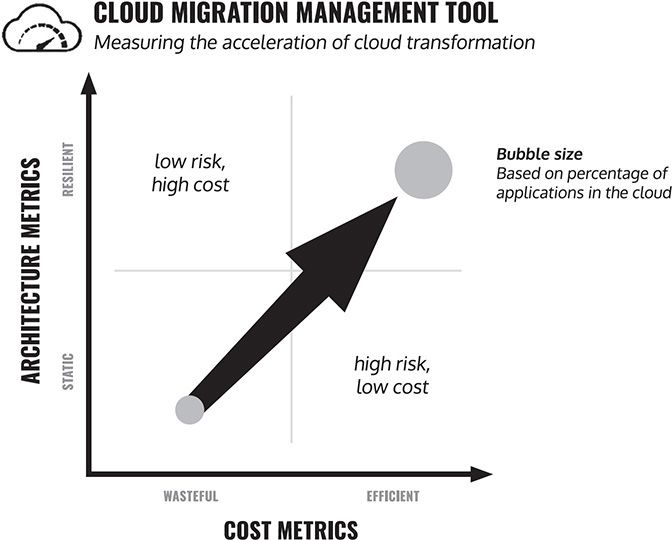

Drew was convinced that reframing measures of success would provide the breakthrough Capital One needed. The past behavior of applying abstracted maturity models had to be unlearned, and the group needed to relearn to focus on defining their own specific, hard-to-measure, system-level outcomes to achieve the extraordinary results they desired. Drew partnered with a developer and created the Cloudometer (Figure 10.2). This system measured the metrics that mattered—the speed, quality, and cost of cloud migrations—and individual talent transformation.

FIGURE 10.2. The Cloudometer

Then came the harder part: figuring out how you incentivize the who to do the how to get to the what and why.

Some approaches worked, while others did not.

On the “what worked” side of the equation, Drew realized that to achieve the strategic objectives, a massive transformation of cloud computing skills would be necessary. Providing individuals with a career path for achieving a valuable, industry-recognized cloud certification offered a professional growth incentive, while also enabling people with the skills to achieve their department objectives. Remember BJ Fogg’s tactics to create new behaviors? Give people training, new tools, and resources, or make the new behavior really easy to do. Then make them feel successful as quickly as possible as they exhibit the new behaviors.

Drew created a Cloud of Fame where the names of employees who earned their certifications were publicly displayed for all to see. It became a badge of honor for those who earned a place on it—they knew their contributions were recognized and appreciated by the organization—while gamifying the process of personal development and healthy cross-company competition. In addition, when employees earned their certifications, Drew sent an e-mail message to his or her manager, that manager’s manager, and that manager’s manager—three levels up. Individuals’ efforts to learn cloud computing were reinforced as valuable, creating positive peer pressure for others to participate and contribute.

While divisional-level certifications were inherently a vanity metric and easy to measure, it created a very visible information radiator for sharing the competency levels of teams, and provided a leading indicator for the rate of training uptake of individuals adopting the skills required to achieve the desired system-level outcomes. Correlating and mixing the easy-to-measure increased competency levels with improvements in system-level, hard-to-measure key performance indicators (KPIs) visualized in the Cloudometer reinforced the value of supporting individuals in their personal journeys. As individuals earned their certifications, providing visible recognition of their accomplishments was also important to success. Each small achievement—or tiny step—helped people feel successful and appreciated as they worked to realize greater system-level outcomes.

On the “what didn’t work” side of the equation, for a few departments supporting legacy maturity models, their hardened culture was too strong to influence. Those managers who held onto their individual, localized status-quo metrics didn’t move. This layer of frozen middle management was a strong barrier between their staff and the disruptive strategies threatening the status quo. People do what their managers reward. If they reward output, that’s all you’ll get. If they reward contributions toward system-level outcomes, then people will focus on that. Remember: The KPIs you communicate to the team—what you make visible and signal you’re looking at to employees—will lead to the behavior you get.

Most of the individuals within these departments recognized the opportunities presented by a shift to cloud computing. Even so, they inevitably prioritized actions that would be valued and rewarded by those in control of their end-of-year ratings and financial incentives, not the bank’s system-level success.

Safety and Transparency

Drew recognized the need to align organizational or system-level incentives to achieve Capital One’s desired outcomes, and he worked within the company to do this. Capital One is a metrics-driven company, and KPIs are used to highlight the misalignment of team-level activities and adoption of new practices with organizational outcomes. But success would ultimately be found in moving all the departments from only easy-to-measure metrics to a mix of easy- and hard-to-measure metrics, from vanity metrics to actionable ones, and from science fiction to harsh facts. But transparency is a double-edged sword. Says Drew:

In my experience, slow adoption in the early phases of transformation is usually masked by internal marketing and wishful bias. The early phases of Agile in enterprises is a great example—many teams faked Agile by implementing meaningless ceremonies while reciting the manifesto. Real transformation occurred once organizations shifted from useless vanity metrics (for example, the number of story points or tasks completed) and focused on outcome-based metrics (for example, percentage increase in customer satisfaction or reducing time to market).

Similar to Agile adoption, cloud transformation was initially slow, and masked by the enthusiasm within the echo chamber of early pioneers. Establishing a visible set of key performance indicators in the Cloudometer created visibility into the slow rate of adoption. The outcome-based measurements were critical to triggering the need to better align system-level incentives with outcomes. The visible display of outcome-based metrics was very uncomfortable for many departments since it exposed their gaps in skills and execution. In a culture that is incentivized based on a distribution curve, that information could be misused for political and personal gain when comparing individual and team performance during end-of-year calibrations.

If it’s not safe to share the negative information and use it to improve the system, then people won’t risk the exposure. People will share only the positive information—the information that won’t get them in trouble—or game it to get their reward. As a result, improvements are based on poor quality of information, and thus the system never really gets smarter. It’s theater. Drew was fortunate to work with leaders who provided him the air cover and psychological safety to share the correct information which revealed the gaps but enabled them to be addressed—the positive effect of negative information. This was vital to success.

Breakthroughs Create Positive Unintended Consequences

With individual actions aligned to visible system-level outcomes, a new behavior emerged in Capital One with learning communities. Individuals began to work in cooperative groups to learn cloud computing, which created opportunities for community leaders to pay it forward by facilitating sessions and helping peers on their own personal transformation journey.

Unlike past technologies that had a much longer shelf life, cloud computing was evolving rapidly with constant releases of new features from Amazon Web Services (AWS). The old training methods (such as instructor-led training) couldn’t scale or keep pace. The organization had to unlearn how to learn and shift to a continuous learning paradigm that relied on self-sustaining and empowered learning communities—as Ed Hoffman did at NASA.

Capital One encouraged people to build knowledge in cloud computing starting with AWS certifications. They didn’t support a fixed mindset of, “Good, you’ve got your certification. You’re done.” They championed a growth mindset of “Great achievement! How can you apply it and help others?” They were encouraged to better themselves and their teams, and that’s what people were recognized for, not just for completing a specific activity or certification.

As a company, Capital One realized innovating its technology systems required talent transformation. “We have a strategic imperative for a pretty dramatic transformation of our technology capabilities as a company. And this is a transition from being a company with an IT organization or an IT shop to really being a technology-led company. The hardest part of that transition is really a talent transformation,” said Rob Alexander, CIO of Capital One.

Unlearning Incentives in Your Organization

When designing incentives, remember Charlie Munger’s words: “You get what you reward for.” Identify your desired system-level outcomes, then make visible and clearly signal to employees what behavior you are looking for. If you change KPIs, that impacts behavior. Financial incentives can be effective—as can a variety of nonmonetary incentives. If you decide to go the financial route, keep in mind that a small bonus can have a great effect.

The problem I saw with individual incentives such as in the large bank mentioned at the beginning of this chapter is that it created lots of negative competition among people in the organization, which led to them actively trying to trip up one another. While the system worked for the individual, the organization suffered in the long term because people were optimizing for what was good for them, and rarely optimizing for what the company was trying to accomplish.

The executive leadership recognized the need to unlearn, and we worked together to relearn their definitions of success, switching individual activity to shared system-level outcomes. We mixed easy- and hard-to-measure KPIs that people could clearly align their effort as contributing toward, resulting in greater clarity for teams, collaboration between departments, and significant returns for the organization.

Achieving system-level outcomes requires creating an environment of psychological safety for people to work within. Transparency in how information is treated is key to creating such an environment and to the ultimate success of the organization.

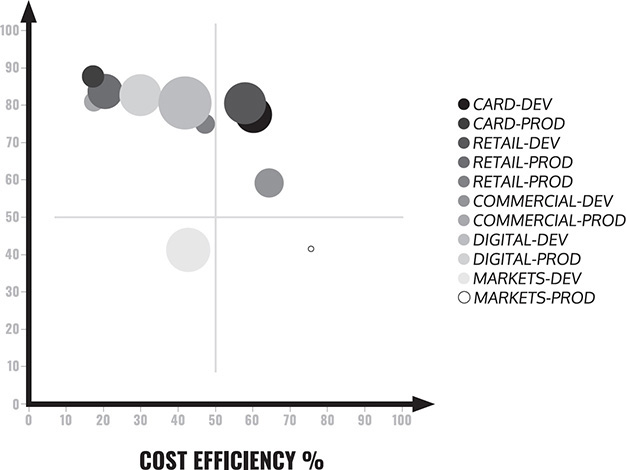

Capital One’s Cloud Center of Excellence (CCoE) designed and operated a massive talent transformation program that increased cloud fluency throughout the organization. More than 15 percent (and counting) of the technology group has earned AWS certifications, enabling the organization to reach beyond the tipping point of critical mass toward a sustainable transition to the new operating model. One of the key ways of measuring success was tracking the number of AWS certifications and correlating the impact on migrations using the Cloudometer management tool to visualize, measure, and demonstrate how training contributed toward achieving the desired system-level outcomes the CEO had defined (Figure 10.3).

FIGURE 10.3. The Cloudometer system-level outcomes

Today, Capital One, the tenth largest bank in the United States, has the highest percentage of virtualized infrastructure of any major bank in the country, all residing in the cloud. They had an amazing transition, and Drew helped drive the talent transformation with an innovative approach that intersected strategy, engineering, and education at scale.