7

Unlearning Management

You manage things; you lead people.

—Rear Admiral Grace Hopper

CEOs, executives, and managers who hold onto legacy thinking and outmoded methods such as command and control—telling people what to do and exactly how do it— are not only micromanaging through control systems designed by themselves and for themselves, they are also limiting the potential of the entire organization. This kills innovation and strips all human creativity, ingenuity, and expression from others’ work. Followers gradually become robots simply focused on executing work—not thinking, not questioning, not believing they have any control over what they do. People are squeezed to reduce costs and deliver more output sooner. They forget what it is to problem-solve for themselves, and they embrace disempowerment to the point that having to think for themselves sparks fear.

This learned helplessness halts extraordinary breakthroughs—progress is at best marginal and at worse backward, resulting in perverse outcomes such as the avoidance of accountability or any decision making without sign-off from authoritative superiors. When no decisions are made at the edges of the organization—where the information is richest, the context most current, and the employees closest to customers, the organization grinds to a halt. Executives and managers complain they don’t understand why people don’t take initiative, but their followers know nothing else but how to follow, never to lead. They live in fear of making the wrong decision, or any decision for that matter; hence, indecision is the result—the outcome that causes the most frustration and dysfunction for all.

Leaders can actually gain more control by taking their hands off the wheel and allowing those employees closest to the situation to make decisions at speed and take accountability for the results. But first executives and managers must unlearn much of their leadership conditioning, which today is still based on an Industrial Era that has long passed. Instead, they must provide clarity of purpose, intent, and direction for what is needed and why it matters, and then stop, shut up, and listen. Let people in the organization with the most context and knowledge of their domains figure out how to get there.

Leaders must leave behind their fixed, Industrial Era mindsets and relearn that they no longer have (or need to have) all the answers—their people do. And for endless breakthroughs to be achieved, they simply need to provide intent and direction, and then get out of the way as people solve the challenges in front of them in ways that are best aligned to the intent they have been provided. The role of leadership is to provide context for what is to be achieved, and why that matters, and then create a system of work that enables people to identify how to achieve those desired outcomes based on the best actions in their current context under their own control.

Your Leadership Conditioning Is an Obstacle to Unlearning

The majority of managers have risen to their current positions based on their competency to know what to do, when to do it, and always having the answer or solution at hand rather than helping others discover the answers and solutions. In fact, these managers are rewarded for this behavior with promotions, pay raises and bonuses, recognition in the company, and ongoing dopamine hits to their brains and egos.

But the higher they rise, the more difficult it is for them to know what to do and when to do it in every circumstance—the span of control is too large, and the mountains of data coming in from all over their organizations too great, and their two or three tried-and-trusted tactics are blunted. The end result of this very common situation is the Peter Principle, where managers rise to their highest level of incompetence and battle to stay there for fear of being found out. They are unhappy and inefficient, and they inhibit further progress for others.

They don’t understand or know how to do something and don’t recognize the deficit, stagnating in what Noel Burch described as “unconscious incompetence.”1 This is a state that many people long reside in until they can be humble enough to recognize their deficit or be willing to take in new information that highlights it, and then be courageous enough to take action and unlearn—becoming consciously incompetent—to relearn and break through.

Many miss these vital but subtle inflection points to unlearn, failing to realize that leadership is about making other people successful by helping them discover the answers for themselves and guiding them along the way. Worse still, many fail to let go of their past success and situational awareness of how the world used to be when they performed that task, role, or responsibility. They fail to recognize the systems and approaches that worked for them then may not work for others now. The world and all of us within it have transformed into something new and different. This is why the Cycle of Unlearning is an effective system to let go of past success to achieve extraordinary results.

One strategy to unlearn your leadership conditioning is to change the environment to stimulate and inspire new ways of experiencing and seeing the world. When we do this, we break out of our regular day-to-day perspective, leave the myopic mindset behind, and immerse ourselves in a new, generative environment. This isn’t the annual Innovation Day off-site; it isn’t the quarterly leadership get-together, and it’s definitely not the week-long innovation theatre tour in Silicon Valley to dream up how to save your business—only to return to the same daily rituals at your desk.

The CEO of the global financial organization I worked with found his breakthrough by making space to reflect on the outcomes both he and the team were achieving as part of their daily work. Yet to achieve this breakthrough they needed to be willing to commit to and acknowledge the necessary conditions to unlearn their own behavior, relearn new skills and new perspectives, and break through many of the obstacles to their own and their organization’s effectiveness (which, coincidentally, were often designed, championed, and implemented by themselves). This prolonged, dedicated, and deliberate practice of new behavior built empathy, understanding, and insight into how to improve themselves and their systems of work. And it created a new kind of leader, practicing a new way of leading. At International Airlines Group we took an even more radical approach by taking six leaders out of the business for eight weeks to deliberately practice unlearning. What are you willing to do?

Real leadership is leaving a team, an initiative, or a business—whatever situation you decide to tackle—in a better state than when you started, with new skills, capabilities, and knowledge to cope with the road ahead, even after you’re long gone. How many leaders can honestly say they have achieved this? Unlearning management is relearning leadership, and in this chapter, we’ll consider why this is required, and how to do it.

The Problem of Legacy Leadership Conditioning

Imagine for a moment that you have been transported back in time to a factory in about 1918, and your job is to lead a group of people whose responsibility it is to manufacture gasoline internal combustion engines for a variety of farm equipment. As a leader at that time, you were steeped in the work of Frederick Taylor, whose groundbreaking book, The Principles of Scientific Management, was published in 1911. Taylor’s principles, which were quickly adopted by American businesses—from farms, to factories, to small businesses, to government, and more—sought to remove inefficiencies from work processes and to use science to maximize productivity that was measured primarily in output.

In practice, Taylor’s principles, aka Taylorism, prescribed the exact steps a worker was expected to perform in whatever job he or she was assigned. So in your imaginary 1918 factory, let’s say there is a worker assigned the job of bolting the engine’s valve head onto the cylinder block, using eight six-inch steel bolts. Using Taylor’s principles, a manager would determine the most efficient sequence of steps the worker should apply to do the job—pulling a bolt from the bin in one motion, pushing it into the hole at the top of the valve head, securing the bolt with exactly 10 turns of a wrench, and then repeating the sequence for the other seven bolts.

As the manager of this department, you know through activity time measurement that this is the most efficient sequence, and that it can be completed in 45 seconds. Now, what if your worker has an idea they believe will make the process even more efficient? You wouldn’t be interested in hearing about it, since you assume that the problem has already been solved (by you and some other educated individuals), and the worker is there simply to execute the solved problem. “Get back to work—you’re wasting time,” you would likely tell the worker. And that’s exactly what they would do, or risk being out of a job.

Unfortunately, many managers still live in this legacy Industrial Age fantasy world, where employees are not encouraged to consider new, alternative, or more innovative ways to address problems, as managers have already “solved” them and lost curiosity in pursuing them any further. A worker’s role is not to think, just do. Yes, this leadership conditioning and behavior still prevails in the majority of twenty-first-century organizations—and is still taught, modeled, and learned. In fact, for the majority of organizations, their systems of management enforce this behavior, and in most cases, reward it. As Gary Hamel, globally recognized business thinker and faculty of London Business School, once wrote about this turn of events, “Your company has 21st century internet-enabled business processes, mid-20th century management processes, all built atop 19th century management principles.”2

People model and are conditioned by the leadership behaviors of those before them. These legacy systems of managing must be unlearned.

While that command-and-control approach might have worked 100 years ago when only a handful of people in most companies were educated, and the work people performed was repetitive and manual, it clearly no longer works in the world we live in today—a world where volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity (VUCA) are baked into all aspects of an individual’s role and the workplace. No matter how educated today’s manager may be, it’s not possible for one person to hold all the information required in their head to build a product, to operate an organization, or to really do the entirety of anything.

One person can’t know all that each member of his or her team knows. It’s unrealistic, and it’s limiting for both the manager and the teams who operate in that model.

Relearning Leadership

Years ago, management guru Peter Drucker introduced the idea of a new kind of worker, the knowledge worker—“people who apply knowledge, rather than manual skill and muscle, to work.”3 According to Drucker, knowledge workers can’t (and shouldn’t) be supervised or managed in the same way that workers in factories used to be. Says Drucker:

To make the right decision the knowledge worker must know what performance and results are needed. He cannot be supervised. He must direct, manage, and motivate himself. And that he will not do unless he can see how his knowledge and work contribute to the whole business.4

Great leadership consists of clearly defining purpose, intent, and the outcomes to be achieved, and then creating systems that allow people to figure out for themselves (by way of experimentation) the best ways to achieve those desired outcomes. While it may seem counterintuitive, the breakthrough that every manager needs to discover and practice is that you become a better and more effective leader when you let go, relinquish control, and empower the people you lead to take control and make their own decisions.

The job of leaders is to design systems that enable people to experiment with potential options and learn as quickly, as cheaply, and as safely as possible while they discover how to achieve the desired outcomes. These are outcomes that leaders and their teams agree upon together, a shared understanding of what accountability means.

When leaders communicate intent, they help employees start to think for themselves, begin real problem solving, and build organizational capability. Leaders can coach and guide teams through asking questions, suggesting aspects to consider, and creating feedback loops relative to the level of VUCA or the challenge the group faces. The higher the level of VUCA, the shorter the loop must be, making the feedback faster, the risk smaller, and the challenge safer to fail. This encourages employees to make decisions for themselves, become psychologically accountable for their work, and learn by doing.

The Myth of Military Command and Control

Whenever I say that leaders should loosen their reins when it comes to command and control, suggesting that it will increase performance and result in better outcomes, someone will invariably chime in, “Hang on a second—the army is a high-performance organization, and it uses command and control!”

In reality, the army relinquished command and control by its leaders in the nineteenth century, after the Napoleonic War. In that war, Napoleon pioneered the idea of maneuver warfare, in which he gave small, decentralized teams of soldiers the authority to move around the battlefield and make decisions for themselves based on the situation and their skills.

Napoleon’s army was successful in doing this because Napoleon clearly communicated the intent of the mission—the what and the why—and the expected outcomes to his troops. The soldiers knew the intent of what was to be achieved—for instance, to take the hill from the enemy—and they were given the freedom to determine how they would accomplish this outcome, quickly reacting to the realities on the ground and adapting their tactics in real time.

This approach sprang from the reality of the age. As armies became larger—with commanders separated by many miles—communication and close coordination between the units became increasingly difficult, leading to potentially deadly outcomes. Giving smaller groups of soldiers the authority to move on their own, without awaiting orders from on high, provided them with greater agility and a crucial advantage on the battlefield.

This approach to military leadership was further developed by the Prussian Army, and in particular by Helmuth von Moltke (perhaps best known for his saying, “No plan survives contact with the enemy”) after he was appointed Chief of the Prussian General Staff. In 1869, he issued a directive titled “Guidance for Large Unit Commanders,” which sets out how to lead a large organization under conditions of uncertainty. Moltke explained, “A favorable situation will never be exploited if commanders wait for orders. The highest commander and the youngest soldier must be conscious of the fact that omission and inactivity are worse than resorting to the wrong expedient.” The philosophy became known as Auftragstaktik or mission command.

Under mission command, leaders describe their intent—communicating the purpose of the orders, along with the key outcome to be achieved—and then trust their people closest to the situation, who have the richest information, to make decisions aligned with achieving that outcome.

Unlearning Command and Relearning Control

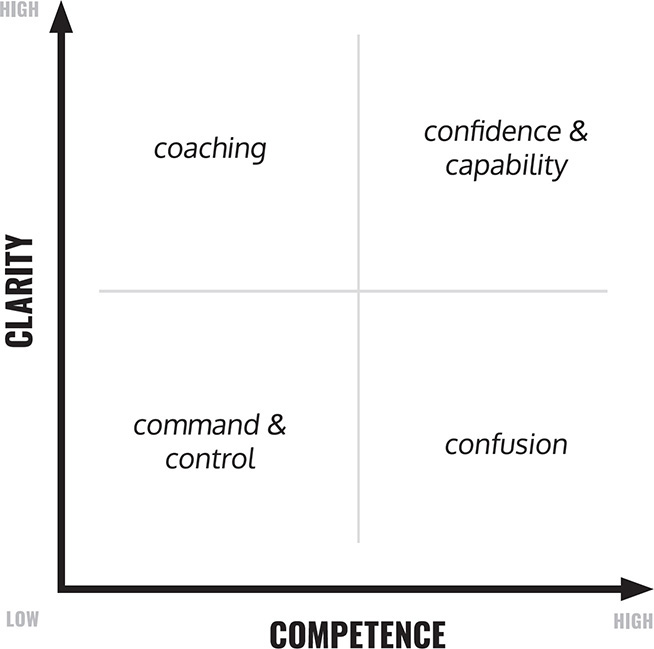

When starting managers on the path of unlearning management and relearning leadership, I often draw my model of Clarity vs. Competence (Figure 7.1) to frame the legacy behavior to be unlearned and the aspiration or outcome to be achieved: leaders having the confidence that their team is capable of making good decisions for themselves. The two axes are clarity on why they should perform the mission and what’s important, and whether the people have the competence to make the decisions required to perform the mission.

FIGURE 7.1 Clarity vs. Competence

Clarity is the responsibility of leadership. Napoleon tested the clarity of his orders by having one of his lowly corporals shine his boots during briefings with his commanders, knowing the corporal would be listening in on the conversation.5 Following the brief, Napoleon would ask the corporal if the plans made sense. If he answered “yes,” then they would go forward with the plans. But if he did not understand them or was confused, then Napoleon and his staff would make changes or draft new plans that were clearer and more easily understood.

Competency is a capability that can be built up in people by giving them skills by training, tools to use, and safe-to-fail opportunities to practice new behaviors to improve over time. As BJ Fogg suggests, helping people get started with new behaviors such as better decision making means starting small and making it easy to do. Then coach them and increase responsibility as they become more competent. As competence grows within employees, leaders also gain more confidence to relinquish control.

One of my favorite examples of this approach comes from Turn the Ship Around!, a book by retired Navy Captain David Marquet. Captain Marquet was made commander of the US Navy nuclear submarine USS Santa Fe, the worst performing submarine in the entire Navy fleet. During a routine drill simulating a fault in the reactor, Marquet came to the realization that having just one point of command during the drill made it inherently inefficient, potentially putting the crew and the boat in jeopardy. So except for taking responsibility for launching weapons that would result in the death of human beings—the boat’s missiles and torpedoes—Marquet vowed to never give another order. Or when framed as an outcome-based unlearn statement:

I will unlearn decision-making in twelve months.

I will know I have when:

100 percent of decisions bar launching weapons will be made by the crew.

This meant going against established Navy policy, which outlined in great detail exactly what decisions the captain was required to make, including when to submerge the boat, start up the reactor, shut down the reactor, connect to shore power, disconnect from shore power, and so forth.

Marquet decided that, instead of giving orders and instructions, he would give the people under his command intent—and he would ask for their intent in return. For example, Marquet says that instead of giving an order during a training exercise such as, “Left full rudder, steady course 255,” he would first tell the officer that his intent was to position the ship near an enemy submarine for attack, and ask, “Where do you think we should position the ship?” The sailor would respond with his or her intent, “Over here,” and Marquet would confirm, “Great idea—go there.”

As a result, Marquet’s officers stopped waiting to receive orders and started requesting and clarifying the mission’s intent. They began taking psychological ownership for decision-making and built confidence in their capability to take action without having to always ask for permission.

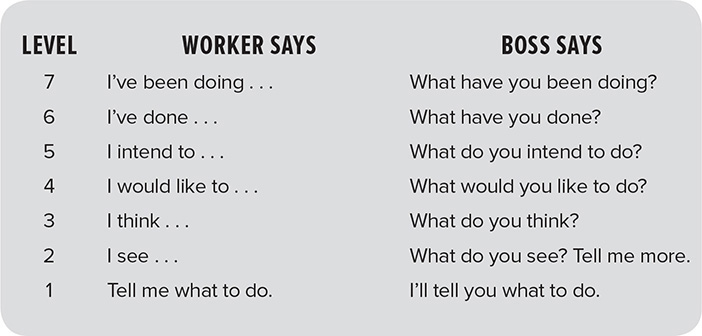

Marquet moved decision-making authority to the point and the person in the submarine who were closest to the richest source of information required to make that decision. Captain Marquet delegated command and gave control to every member of the crew, creating leaders at all levels. He didn’t do this all at once. Marquet thought big but started small. He did this by working his way up what he calls the Ladder of Leadership, starting at Level 1 with the desired outcome for all crewmembers to achieve Level 7 (Table 7.1).6

Marquet uses the words “boss” and “worker” to denote hierarchy. The words could be “parent” and “child” or “teacher” and “student.” At the bottom of the ladder, you have detailed task-by-task instructions for workers to do. At the top, workers are determining what should be done, and reporting back what they have been doing.

TABLE 7.1. The Ladder of Leadership

The ladder ties into the tension between the learning anxiety employees have about making decisions without clarity, and the confidence they have in their own competence to make these decisions. There are two columns of the ladder—one for workers and one for bosses—to be used by leaders to spark conversations with their employees and encourage them to think and scale their leadership impact. By using this approach, says Marquet, “Together, you will move up the Ladder of Leadership.”7

As workers demonstrate clarity of intent and competence in decision making, leaders develop more confidence in their capability and step up to the next level of prompting questions they ask workers. Similarly, as workers gain more confidence in their capability, they lead with their statement of what action they’ve taken based on the intent of the mission. The Ladder of Leadership also makes words like empowerment observable and measurable and gives you words to practice and evaluate where you and your teams are.

Under Captain Marquet’s leadership, the USS Santa Fe became one of the most highly decorated ships in the fleet—going from worst to first to record scores in Navy history for operational efficiency.

One executive I work with from a well-known Silicon Valley technology company wanted to figure out how to grow the company’s customer base by 15 percent in the next six months while creating more autonomy and accountability for her people. She was thinking big, so I encouraged her to start small by asking the teams come back with three options, explain the pros and cons of each of them, and the recommendation that they’re making—the one they believe should be done to achieve the company’s desired outcome. The leader would listen and then agree to try an experiment. The higher the level of VUCA, the more she should encourage smaller, faster, safer-to-fail experiments with short feedback loops to gauge how the team is progressing toward the outcome both she and the team are seeking.

The intent was to invest in the best option to increase the customer base by 15 percent in six months, grow the decision-making capabilities of the team, and increase the leader’s confidence in them. When a team was highly uncertain about how to achieve the desired outcome, the leader would encourage the team to go out and try lots of different options, run experiments every few days, or weekly, and report back on their progress. If a team had less uncertainty, perhaps they would come back just once every two weeks, monthly, or when the team had made an impactful discovery or needed further clarity.

As the teams saw their leader relinquish command and give them control to decide what experiments to run, at what frequency, and when to report back, they took ownership and became more engaged in their work. Both the leader and the team started small by designing short feedback loops into the process, and as they gained confidence in the results and new way of working together, they accelerated the speed of innovation. They also learned when to seek or share the new information they discovered with one another as a result of rapidly experimenting—using the new information to course-correct, validate, or update their direction and innovate at speed. The group didn’t achieve the 15 percent increase in six months; they did it in 16 weeks. This is how you can start small to unlearn management and relearn leadership at all levels.

Control is created not by telling people what to do but by designing feedback loops into the system of work to help teams measure against the outcomes they’re achieving, how they’re moving toward them, and what they’re learning along the way.

Introducing a fundamental behavior like this is not easy for someone whose leadership conditioning has been to own command and hold onto control by telling people what and how to do their work. It will feel unsettling and uncomfortable, and there’s always the chance that this discomfort will persuade you to go back to your old ways of leading. But if you persevere and give up control to your people—one small step up the Ladder of Leadership, one small step at a time—you will create greatness in others, which is the best possible outcome for any leader, especially at scale.

The Flow Zone

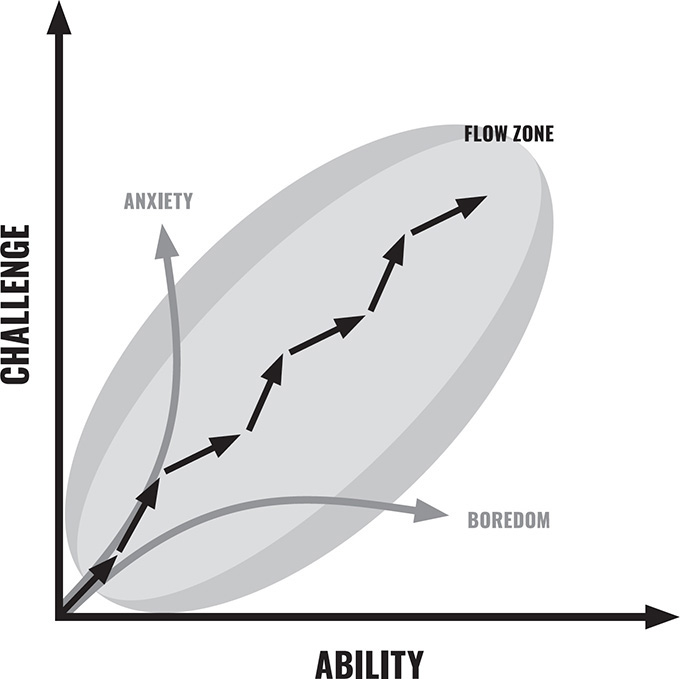

There are many ways to model the transition to relearning leadership control and to letting go, but one I find particularly interesting is dynamic difficulty adjustment, an idea that came from the world of video game development. When people design a video game, they want players to enjoy and become engaged in the experience. If a game is too complex or too difficult, players will become frustrated or anxious, causing them to quit in a short amount of time. If a game is too easy, then players will become bored and also quit in a short amount of time. The ideal outcome is to design a game that isn’t so complex or difficult that it causes players to quit, but that is interesting or challenging enough to avoid causing players to get bored.

In Figure 7.2, this ideal outcome is illustrated in the flow zone, which refers to Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s idea of flow—“a state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter; the experience is so enjoyable that people will continue to do it even at great cost, for the sheer sake of doing it.” The flow zone shows where challenge and ability are balanced, and flow naturally occurs.

FIGURE 7.2. The Flow Zone8

According to Csikszentmihalyi, there are eight characteristics of flow:

• Complete concentration on the task.

• Clarity of goals and reward in mind and immediate feedback.

• Transformation of time (speeding up/slowing down of time).

• The experience is intrinsically rewarding.

• Effortlessness and ease.

• There is a balance between challenge and skills.

• Actions and awareness are merged, losing self-conscious rumination.

• There is a feeling of control over the task.9

However, people are different, and what one player finds complex, difficult, and frustrating, another player will find simple, easy, and boring. Flow is broken, and the game player quits. What is a game designer to do?

They create interactive video games, such as Candy Crush, that incorporate dynamic difficulty adjustment—a system that scales the difficulty of the game up or down in real time, depending on the player’s skill level. While this might seem on the surface to be commonsensical, it requires the designer to do something he or she might not want: to give up control over how the game is played and delegate this crucial duty to the software itself.

Games provide safe-to-fail environments for people to unlearn, relearn, and break through. This is why the military runs simulations and war games, and why gamers keep playing and playing games to develop their skills and improve. Augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) will only accelerate this process in the future.

The concept of dynamic difficulty adjustment can be applied to a leadership setting. Some people find certain behaviors easy, while others find the same behaviors hard. This ties back to the axes of clarity and competence—clarity of intent (and confidence in what decision needs to be made) and the competence of taking action, based on the capability, skill level, and experience they have from making those decisions before. The idea is to develop everyday employees so they feel confident and capable of making decisions and taking the lead themselves—without the constant command and control of the organization’s leaders. But leaders must feel confident and the team must be capable for them to delegate decisions down to the appropriate person. Both parties have to work their way into the zone.

When you encourage people to start thinking and making decisions for themselves, or you start asking questions to see if they understand the mission’s intent—and they reply with their intent—you get evidence that you’re developing confidence and capability and moving up the Ladder of Leadership by unlearning management and relearning leadership.

When you start to ask questions like, “What do you think we should do?” others start to build psychological ownership and accountability because they’re making the decision. They start explaining what it is they’re trying to do, and why they have decided to do it—their own intent. Your job as a leader is to let go of your legacy behavior and create a system that allows and supports your people to make good decisions themselves, for which you provide clarity of intent and seek to build the competence for others to provide their intent in return.

Alan Mulally, who served as CEO of Boeing Commercial Airplanes and Ford Motor Company (he turned the latter around from a $17 billion loss to profitability), used his Working Together Management System to manage both companies. The system involved gathering together his top managers every week to review their business plan and to identify any problems. When a problem was identified, managers were required to find the people in the company closest to the problem and who were in the best position to solve it. Mulally firmly believed that the job of his leadership team was not to solve every problem. Instead, it was to identify problems and then find the people most qualified to solve them.

To unlearn Industrial Era management and command and control, relearn leadership, and break through to this intent-based world, leaders have to embrace the Cycle of Unlearning to identify ways that they can slowly start to let go of giving every command and controlling every decision. To accomplish this requires being confident in the capability of the people who report to them to competently take control of the decisions that need to be made. This is one of the most important problems I come up against, especially when working with leaders. They have a mindset and conditioning that the reason they’ve become a leader or a manager in the company is because they knew all the answers—that was the foundation of their competence. So when people would ask them questions, they felt they had to have the answer to demonstrate their competence and maintain command by exercising control.

While it feels good to get the dopamine hit when you have the correct answer, it prevents the discovery of new options and it makes it unnecessary for other people to think, creating the learned helplessness that renders people fearful of making any decisions at all. Worse, it stops people from even contributing.

One of the things I do as a consultant is to help leaders get out of the business of making decisions and get into the business of helping others make good decisions that are aligned with the intent that they’re trying to move toward. It’s a subtle but very powerful shift. This is what leaders must unlearn, and then relearn, with safe-to-fail opportunities for them and their people they lead to develop confidence and capability together, if they want to be more effective, more successful, break through, and achieve extraordinary results.

Relearn to Move Decisions to the Information

Some believe that you’re either born a leader or not, and if you’re not born a leader, then you can never be all that good as one and you shouldn’t even try. This, of course, is rubbish, and grounded in the fixed mindset described by Carol Dweck. There are systems that allow anyone to discover how to be a good leader—perhaps even a great one.

This is one of the premises that I have to teach people all the time. High-performance individuals and companies create systems that allow the people closest to the richest sources of information to have the authority to make decisions, because they have the most context of the situation and the competence of skills required for how best to take action. Moving authority to the appropriate individual is what creates the accountability. Leadership responsibility is to clarify the desired outcomes, not the individual’s actions.

It’s important to note that leaders don’t just randomly trust their people. Individuals and organizations create systems that give them trust or fast feedback, if the aspiration or outcome they wish to achieve is not possible, flawed, or must be corrected—thus providing control. This requires creating and scaling systems of work that encourage people to take responsibility and accountability by giving them opportunities to run safe-to-fail experiments with tight feedback loops. This allows leaders to relinquish command when they see evidence of competence in their employees, and they gain confidence in their ability to make good decisions and take control. This is the environment high performers don’t only thrive in—they seek it.

There’s a great story that Adrian Cockcroft, VP of Cloud Architecture Strategy at Amazon Web Services, tells about the time he was at Netflix. Adrian was in a meeting with a group of senior executives from major banks, retailers, and others, and the executives complained that they were unable to do the same level of innovation because they didn’t have great engineers like Netflix did. Adrian looked around the table and saw the names of all the companies in attendance. His reply was, “But we got them from you! We just create an environment where we told them what we wanted, and got out of their way to achieving it.”

In some respects, the management innovation that I’m asking my clients to unlearn is to stop making decisions and let other people make decisions. Toyota has long believed that first-line employees can be more than cogs in a soulless manufacturing machine; they can be problem solvers, innovators, and change agents. While American companies relied on staff experts to come up with process improvements, Toyota gave every employee the skills, the tools, and the permission to solve problems as they arose and to head off new problems before they occurred. Toyota’s real advantage was its ability to harness the intellect of “ordinary” employees. In fact, if you ask executives what Toyota does, they won’t say they build cars; they’ll say they build great people who build great cars.

Toyota pioneered the use of Andon cords strung above the assembly lines in their manufacturing plants; now wireless yellow call buttons serve the same purpose.10 When there is a serious problem that can’t be quickly and easily resolved, assembly line workers have the authority to push the yellow call button, which immediately stops the assembly line of the entire factory and illuminates a sign above the workstation, which indicates exactly where the problem is.

When an employee pushes the button, the first thing the manager does is “go-and-see” the problem immediately by stopping whatever he or she is doing and physically walking over to the workstation in question—not making a call to the workstation from his or her office on the executive floor or sending an email demanding action and answers. A key element in Toyota’s Production System and work process is that the managers actually go to the workstations where the problems are to see it for themselves. The managers thank employees for finding the problems, and then ask the workers a series of five questions to aid the employees in problem solving to address the obstacle they have discovered. In his book Toyota Kata, Mike Rother describes this as the Coaching Kata:

1. What is the target condition?

2. What is the actual condition now?

3. What obstacles do you think are preventing you from reaching the target condition? Which one are you addressing now?

4. What is your next step (next experiment)? What do you expect?

5. When can we go and see what we have learned from taking that step?

The managers don’t tell the employees how to fix the problem or correct it for them. Instead, they work together to devise an experiment that improves the system of work.

It’s not about the leader solving the problem. It’s about coaching the employee to improve their capability and competency of doing the work, so they can better solve problems. And it requires employees to think and come up with different options, examine them, explain their intent, and the upsides and downsides of each of the options. What’s the potential benefit of each? What’s the potential cost or impact? As a leader, your role is to teach employees how to evaluate the various options and develop a position about what they think should be done.

The question for leaders is how they can move decision making to the appropriate individual and have the confidence necessary to delegate authority. The journey starts small: to manage uncertainty by way of the feedback loops you design into your systems of work, then building both your own and the team’s confidence and capabilities to explore problems and figure them out.

Amazon’s Leadership Principles: Scaling a System of Confidence and Capability of Leadership

Amazon Web Services (AWS) has set the bar high for the provision of innovative public cloud services to some of today’s largest and most successful companies. In the final quarter of 2017 (Q4 2017), AWS’s revenue surged to $5.11 billion—a revenue growth rate of 44.6 percent, taking AWS revenue to $17.46 billion for the year and accounting for approximately 10 percent of Amazon’s entire revenue for 2017.11 Long story short, AWS continues to ward off an array of competitors in the cloud, including Microsoft and Google.

I am convinced that a significant reason for AWS’s success, and for the continued success of Amazon overall, is its approach to leadership. This approach to scaling their system of leadership—which among other things pushes decision making down from leaders to employees—is baked into Amazon’s leadership principles. These principles represent the organizational intent of the company and how to respond to any situation. Everyone in Amazon is expected to follow these principles. It is a codification of their behavioral norms. It is not just for “leaders,” as everyone in the organization is considered to be a leader in whatever it is they do. What follows are a few examples (all of the principles can be found here at amazon.jobs/principles).

Learn and Be Curious

Leaders are never done learning and always seek to improve themselves. They are curious about new possibilities and act to explore them.

Think Big

Thinking small is a self-fulfilling prophecy. Leaders create and communicate a bold direction that inspires results. They think differently and look around corners for ways to serve customers.

Bias for Action

Speed matters in business. Many decisions and actions are reversible and do not need extensive study. We value calculated risk taking.

Earn Trust

Leaders listen attentively, speak candidly, and treat others respectfully. They are vocally self-critical, even when doing so is awkward or embarrassing. Leaders do not believe their or their team’s body odor smells of perfume. They benchmark themselves and their teams against the best.

Have Backbone; Disagree and Commit

Leaders are obligated to respectfully challenge decisions when they disagree, even when doing so is uncomfortable or exhausting. Leaders have conviction and are tenacious. They do not compromise for the sake of social cohesion. Once a decision is determined, they commit wholly.12

This subset of Amazon’s principles is a way to create a system that allows people to make decisions that are aligned with what the company values and its leadership intent. There’s nothing that says employees should launch a new product or service—or not. The principles provide the dynamics to challenge employee thinking at every level.

As you build your own system, define intent of what great leadership is and then hold one another accountable to it. This will enable you to scale the system of leadership to your entire organization—566,000 people in Amazon’s case.13

Great Systems of Leadership Lead Themselves

When leaders and teams create great systems and behavioral norms, people want to protect them. And one of the best ways to protect these systems is to ensure that the people you hire and retain in the organization are aligned with the intent of your systems—and remove those that aren’t. If someone doesn’t value what the system values, then he or she is not the correct member for the system—for your organization.

One of my favorite stories that exemplifies this is the hiring process for surgeons at the Mayo Clinic. The Mayo Clinic attracts some of the top medical practitioners and surgeons in the United States and internationally, which provides the clinic with a remarkably talented pool of candidates to draw from. What separates one top surgeon from another is less technical and more behavioral, and the clinic ardently searches for team players in its hiring.

To help determine which of these many talented individuals is most likely to fit in Mayo’s organizational culture, the members of the interview team always ask this question: “Tell us about the most difficult surgery you’ve performed.” And then they listen closely to the surgeon’s response—counting how many times they say “I” versus “we.” If the ratio of “I” to “we” is over a certain amount, the surgical candidate won’t be offered a position at the Mayo Clinic. The belief is that surgery is such a complex and difficult task that no one person can do it on his or her own. Surgeons need a great team to support them. That is the system that Mayo Clinic values, and candidates who aren’t aligned with the system are rejected to ensure that it is protected.

In his book Principles: Life and Work, investor and entrepreneur Ray Dalio presents six principles for getting the culture right in any organization. These principles are based on the application of hedge fund quantitative thinking and computerized machine learning processing to decision-making processes in human systems. They have their own system of leadership based on clarity and competence captured in the principles they value:

• Trust in radical truth and radical transparency.

• Cultivate meaningful work and meaningful relationships.

• Create a culture in which it is okay to make mistakes.

• Get and stay in sync.

• Believability weight your decision making.

• Recognize how to get beyond disagreements.14

Dalio aims for radical transparency about how people get to the decisions they want. He asks the question, “Instead of saying I’m right, how could I create a system to help me know if I was right?” The answer is to use radical transparency, real-time colleague feedback, and algorithmic processing power to create an idea marketplace where people are encouraged to speak up, tell the truth, and have their believability rated and ranked to inform the group decision making.

In one example, Dalio has a system for meetings where people receive real-time feedback from other people in the meeting about how they are performing. So I might be in a meeting talking about leadership, and other meeting participants will be asked, “On a scale of one to ten, how believable is Barry right now?” And you get that real-time feedback from everyone in the meeting. It’s radical transparency, but it’s also a data-informed, automated approach; people are providing feedback and collecting data as you’re going.

The end result is an automated system of leadership and an environment where people can make decisions based on others’ demonstrated confidence and capability. While it may not be for everyone, it shows how human systems can and are being augmented with technology, in search of higher performance.

By helping your people get better at making decisions, you can get better at letting go of making all the decisions yourself. Great leaders provide clarity of intent and the outcomes to be achieved, and they build competence in their people to be confident and capable in making those decisions. For most leaders, this requires unlearning the way they lead, and letting go of making all the decisions.

What we’re trying to do is move decision-making authority and accountability to where the information is richest, and to the people closest to it. The reason many companies are slow and languid is because employees aren’t allowed to make decisions. They have to have meetings and run their ideas up and down the chain of command. They have to get through a jungle of bureaucracy and red tape, just to get in front of a leader for a sign-off—or a rejection. Whatever the decision turns out to be, the process is too slow. What you really want leaders to do is communicate the outcome and then let the teams make the decisions on how best to get there—just like mission command.

This requires leaders taking their hands off the wheel. You might think that’s too great a leap to make—that there’s too much at risk—but you can think big, start small, and teach your teams how to make good decisions. When you have decisions that are highly uncertain, make feedback loops shorter and faster, gather information, adjust, and go again. Fundamentally, it comes down to unlearning your legacy leadership conditioning and relearning the better behaviors that will make you a better leader and make your people better leaders, too. The breakthrough occurs when you’ve got all your people leading, and they’re scaling the leadership in your organization.

You can’t do it by yourself, but with everyone rowing as one, with a singular mind, you can scale your leadership—and your ability to do more, deliver greater impact, and grow.