CHAPTER 2

An Introduction to Leveraged Finance

The leveraged loan markets and high‐yield bond markets play a critical role in helping finance speculative‐grade borrowers. These debt contracts have a variety of special features that make them unique in the financial markets. They are key to the restructuring of distressed firms because leveraged structures are more likely to become distressed than nonleveraged structures. Investment banks, hedge funds, and private equity funds (PEs) pay close attention to this special segment of the financial markets.

Both the leveraged loan markets and high‐yield bond markets in the United States have experienced fast growth since the end of the 2008–2009 financial crisis. Both markets experienced a record amount of new issuance in 2013 – over $600 billion of leveraged loans and over $330 billion of high‐yield bonds issued in total (based on data from Standard & Poor's Leveraged Commentary & Data (S&P LCD) and SIFMA). Total issuance in both markets declined shortly after 2013, when concerns about deteriorated underwriting standards led the Federal Reserve, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency to issue new leveraged lending guidelines.1 By 2017, however, issuance had returned to the peak level reached earlier ($651 billion in leveraged loan issuance and $284 in high‐yield bond issuance).

In this chapter, we provide a brief introduction to these two major instruments for speculative‐grade financing. We touch on important features of credit agreements and bond indentures that govern the rights and responsibilities of the creditor and the borrower. We also discuss how lenders design contracts to protect their claims. Finally, this chapter introduces debt subordination, which is important to understanding creditor rights in bankruptcy and performing the reorganization and waterfall analysis (discussed in Chapter 3, Chapter 5, and Chapter 6 herein).

LEVERAGED LOANS: OVERVIEW

Leveraged loans are a segment of the syndicated loan market focusing on lower credit borrowers. They emerged in the mid‐1990s as a new asset class. The expanded investor base resulted in significant growth in demand for this loan segment. The fast growth of this market and the need for uniform market practices and standardized trading documentation prompted the formation of the Loan Syndications and Trading Association (LSTA) and the Loan Pricing Corporation (LPC). The standardization of loan documents contributed to the increase in market liquidity and efficiency, which, in turn contributed to the growth of a robust, liquid secondary market.

There are various definitions of leveraged loans. Many practitioners use a yield‐spread cutoff. For example, loans with a spread over LIBOR above 150 basis points would be referred to as leveraged loans. Practitioners also refer to loans that are rated below investment grade, which refers to credit ratings at Ba1 or below by Moody's and at BB+ or below by S&P or Fitch as leveraged. Compared to investment‐grade loans, leveraged loans typically carry higher interest rates, larger fees, more stringent collateral requirements, and more and tighter covenants. Leveraged loans are issued for purposes ranging from refinancing, financing mergers and acquisitions (including leveraged buyouts (LBOs)), and recapitalizations (e.g., dividend recaps) to general corporate purposes.

Like other syndicated loans, leveraged loans are structured, arranged, and administered by commercial and investment banks. These banks, known as arrangers and agents, charge a fee for their investment banking and administration services. The lead arranger structures the loan and credit agreement and solicits interest from potential lenders. It is also referred to as the book runner, acting as the “top dog” in a syndication. The agent bank manages servicing and administration of the loan after syndication. There are many other titles assigned to participants performing various roles in the lending process (e.g., administrative agent, syndication agent, documentation agent, etc.).

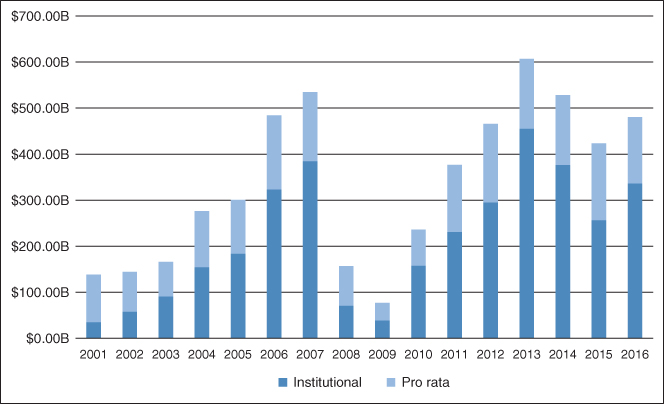

Figure 2.1 shows the amount of annual leveraged loan issuance. The pro rata portion consists of revolving credit and amortizing loans, which are typically issued to and held by banks, while the institutional portion consists of nonamortizing term loans, which are typically held by institutional investors. The figure shows that revolving credit and amortizing loans accounted for about half of the total issuance in the early 2000s but only about one‐third in recent years, suggesting an increasing involvement by nonbank institutional investors in the leveraged financing markets. The main lenders in this market segment include collateralized loan obligations (CLOs), loan mutual funds, high‐yield funds and hedge funds, and finance and insurance companies. According to S&P LCD, as of the end of 2017, CLOs accounted for 64% of the institutional market share, and hedge funds, high‐yield funds, and loan mutual funds account for approximately 30% of the institutional loan market share, while insurance companies and finance companies account for the rest.2

FIGURE 2.1 Leveraged Loan Annual Issuance, 2001–2016

Source: Image created based on data from S&P Global.

The shift in the identity of the lenders from banks to nonbank institutions occurs not only at the stage of loan origination but also through turnover that occurs in the secondary market. In secondary market trading, institutional investors take part in a syndicated leveraged loan through either an assignment or participation. Through assignment, the buyer of the loan becomes the direct lender of record and receives interest and principal payments directly from the agent bank. The buyer is entitled to all voting privileges of the other lenders of record. In contrast, through participation, the buyer takes a share of an existing lender's loan. The buyer does not generally have full voting rights, except for material changes in the loan document such as interest rate, maturity, and collateral. Assignments may be subject to borrower consent, while participations are granted without consent unless they appear on the disqualified institutions (DQ) list, which comprises entities identified by the borrower as not permitted to own its debt.3

While the precise identity of nonbank institutional lenders at origination is not publicly observable, a number of academic studies suggest that their entry into this market expanded the supply of capital and led to a lower cost of capital for borrowing firms. Ivashina and Sun (2011) show that corporate loan spreads tend to fall during times when institutional loans are syndicated more quickly, and that syndication speed depends on flows of capital to large institutional investors. Nadauld and Weisbach (2012) focus on the role of securitization and show that loans which were more likely to be purchased by CLOs carried lower interest rate spreads, suggesting that securitization was associated with a lower cost of borrowing. Benmelech, Dlugosz, and Ivashina (2012) show that borrowers whose loans were securitized did not experience adverse outcomes (declines in credit quality) compared to borrowers whose loans were not securitized.

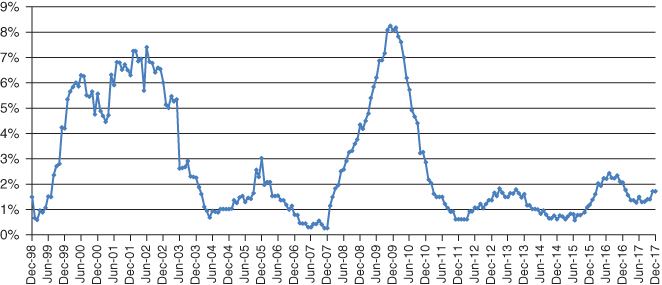

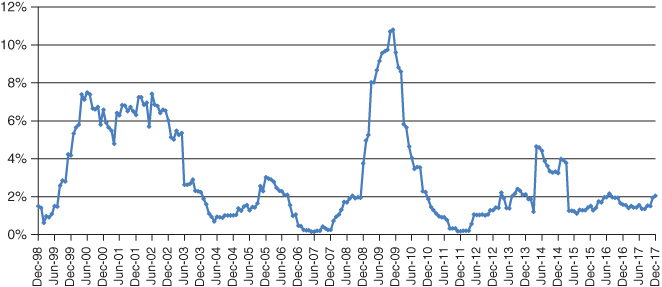

Figures 2.2a and 2.2b present the S&P/LSTA 12‐month default rate (both by issuer count and dollar‐denominated amount) on leveraged loans from 1998 to 2017. In most months since March 2013, the dollar‐denominated loan default rate exceeded the issuer‐denominated rate due to defaults by only a few relatively large issuers. Note that the average default rates of leveraged loans are generally lower than those for bonds (Figure 1.4).

FIGURE 2.2a S&P Leverage Loan Index 12‐Month Moving Average Default Rate (by Issuer Count), 1998–2017

Source: Altman and Kuehne (2018b).

FIGURE 2.2b S&P Leverage Loan Index 12‐Month Moving Average Default Rate (by Dollar‐Denominated Amount), 1998–2017

Source: Altman and Kuehne (2018b).

Conditional upon a default, the identity of the holders of the loans impacts a firm's ability to renegotiate its debt. A longstanding belief, with both theoretical and empirical basis, is that debt which is more dispersedly held is subject to holdout problems and therefore more difficult to renegotiate (Gilson, John, & Lang, 1990; Asquith, Gertner, and Scharfstein, 1994). The most recent study to examine this question is by James and Demiroglu (2015), who study 344 debt restructurings from 2000 to 2012. Confirming the earlier studies, these authors find that firms are most likely to be able to restructure out of court when the firm relies on a single bank. Firms that rely on institutional loans, in particular those which have been securitized, are more likely to restructure in bankruptcy. An important additional finding is that firms that rely more on securitized loans are more likely to use prepackaged bankruptcies. They further find that firm level recovery rates and the likelihood of emerging from bankruptcy are not related to the lender identity.

There are two major instrument types within the leveraged loan universe: revolving credit facilities (revolvers) and term loans.

Revolvers

A revolving credit facility, like a corporate credit card, allows the borrower to draw down, repay, and reborrow up to a specified credit limit over the life of the loan. The facility is primarily used to meet temporary working capital needs. Lenders, typically commercial banks, are committed to providing funds if conditions for lending are met. Revolvers typically have a 364‐day maturity (the 364‐day facility) due to banks' concern about the regulatory capital requirement for issuing loans with a maturity over one year to speculative‐grade borrowers.

Interest rates are quoted as a base rate or London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) plus an applicable margin.4 Common base rates are the prime rate and federal funds rate. A floor is often imposed on LIBOR or the base rate. For example, a LIBOR floor of 1% suggests that 1% will be used as the base rate if LIBOR is below that threshold. The applicable margin is typically a spread of 150–400 basis points. Lenders typically adopt performance‐based pricing for the revolving credit facility. For example, the applicable margin or the spread can be tied to specific financial ratios (e.g., interest coverage ratio or leverage ratio) or the credit rating of the borrower.

Banks impose various types of fees on the revolver. These typically include an upfront fee, paid at loan closing, with the largest share going to the lead arranger; a commitment fee, charged on the daily average undrawn balance; a facility fee, charged on the entire amount of the facility; an administrative fee, paid annually to the administrative agent for its services; and others. The lender often imposes extra interest (typically 2% above the applicable rate) if the borrower defaults.5 These fees can at times add up to over 500 bps, imposing additional costs on the borrower over and above the interest rate.

For speculative‐grade companies, borrowing under a revolver is almost always secured by collateral, which can be substantially all assets of the borrower. The amount of credit available is determined from the borrowing base, defined as the value of specified assets of the borrower. Since most revolvers are short term, the most common types of assets in the borrowing base are current assets, including cash and marketable securities, accounts receivable, and inventory. Commodity and energy producers typically pledge reserves as the borrowing base. The credit available is generally calculated as the product of the advance rate (the maximum percentage of the borrowing base the lender is willing to extend for the loan) and the value of those assets.

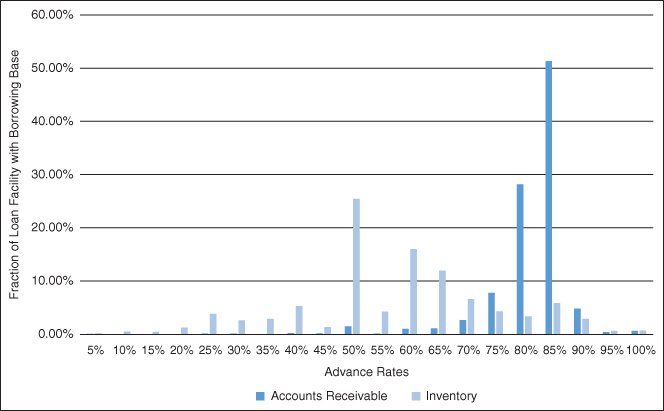

Figure 2.3 shows the percentage of revolvers using accounts receivable and inventory as the borrowing base, based on 10,061 revolving facilities initiated by US corporations (both investment‐grade and high yield) between 1996 and 2016, drawn from Thomson Reuters' LPC Dealscan database. The figure shows that the typical advance rates for accounts receivable are between 75% and 85%, while they range from 50% to 65% for facilities relying on inventory. This is intuitive, because receivables are considered a more liquid and safer current asset than inventory, which is subject to a large potential discount if it becomes necessary to sell in order to raise immediate cash.

FIGURE 2.3 Advance Rates Based on Various Borrowing Bases

Source: Authors' compilation based on Thomson Reuters' LPC Dealscan.

Term Loans

Term loans are installment loans that have scheduled interest and principal payments. They typically have a longer maturity than revolving facilities. The most common maturities for term loans are five to eight years. There are two types of term loans, and they differ in whether a progressive prepayment of principal is required. An amortizing term loan (Term Loan A, or TLA), normally syndicated to banks along with the revolving facility, sets up a payment schedule for the borrower to pay down the principal over time, before maturity. In contrast, a nonamortizing loan (Term Loan B, Term Loan C, etc.), normally syndicated to institutional investors, often has debt structured with a balloon principal payment at maturity.

LENDER PROTECTION

Classic finance theories suggest that severe incentive conflicts arise between debtholders and shareholders. These conflicts of interest are manifested in distributions to shareholders, whereby shareholders are paid a large amount of cash dividends; claim dilution, whereby shareholders have a preference for issuing new debt with equal or greater priority to existing debt; asset substitution and over‐investment, whereby shareholders prefer risky projects even if they carry negative NPVs; and underinvestment, whereby shareholders pass up positive NPV projects. Lenders take actions by imposing various protection clauses in the creditor agreement for their own protection. We provide a brief overview of the standard clauses for lender protection specified in a typical credit agreement below.

Conditions Precedent

Conditions precedent are conditions that must be met for a borrower to receive its funds. There are initial conditions, which must be met at deal closing, and ongoing conditions, which must be satisfied at each borrowing (e.g., under a revolver). A lender that believes a condition has not been satisfied is legally entitled to decline to lend. Some examples of conditions precedent are legal opinions from a borrower's legal counsel; no material adverse change (MAC) of a business, condition, assets, and operations; and environmental due diligence.

Representations and Warranties

Representations and warranties are given by a borrower to assure the bank that the borrower has provided accurate facts and information. Representations and warranties, particularly those that relate to legal condition, are often covered by the opinion of the borrower's counsel. If a representation is inaccurate, which may be considered a default, lenders have the legal right to stop lending and even demand repayment of loans.

Mandatory Prepayments

This section ensures that company funds are not used to benefit other parties at a lender's expense. Mandatory prepayments are typically tied to asset sales, debt issuance (debt issuance sweep), equity issuance (equity issuance sweep), excess cash flow (excess cash flow sweep), and change of control.

Prepayments tied to asset sales require a borrower to use a fraction, or all, of the proceeds from the sale to pay down debt. Similarly, a debt issuance sweep and an equity issuance sweep require the borrower to make prepayments using the proceeds of debt issuance or equity issuance, respectively. Excess cash flow sweep requires that some percentage of the borrower's excess cash flows is applied to prepay outstanding loans. Excess cash flows are typically defined as the excess of EBITDA over the sum of (i) capital expenditures (ii) the aggregate amount of debt service (iii) the tax payment amount, and (iv) any decreases in working capital, for an agreed‐upon accounting period. However, the actual definition highly depends on what is specified in the contract and can be complicated. In fact, just the definition of EBITDA may take up to a full page of the credit agreement. Finally, the loan contract often requires the firm to retire the debt upon a change of control, unless not applicable because of a “debt portability” carve‐out in the loan documents. An increasing number of portability clauses have been used in institutional term loan contracts, enabling the firm to avoid having to refinance its debt upon a change of control.

There are many other types of prepayment requirements, most of which are specific to the revolving facilities. For example, a “revolving clean downs” clause requires a borrower to have no outstanding amount drawn under the revolving facility for a period of 30 days during each calendar year. For asset‐based lending (ABLs), prepayments are required when there are negative shocks to the value of the underlying collateral. ABLs are commonly used by commodity producers, such as exploration and production companies, in the energy sector. These companies typically pledge their underlying reserves as the borrowing base for ABLs. The advance rates depend on the nature and the value of the reserve (rates being higher for proved reserves than for probable or possible reserves). This creates potential problems when underlying commodity prices experience large swings. When the price of oil plummeted, for example, not only did commodity producers lose their revenue streams, but the value of their collateral also shrank as a result, resulting in lenders accelerating the loan payments. This can further exacerbate the financial constraints faced by these companies.

Covenants

There are three primary types of loan covenants: affirmative covenants, negative covenants, and financial covenants.

Affirmative covenants impose conditions and actions that a borrower must take. There are generally three categories: disclosure covenants, standard covenants, and other covenants. Disclosure covenants focus on information disclosure and delivery, such as borrowers submitting timely financial statements, compliance certificates, notices of material events, and so on. Standard covenants require borrowers' proper maintenance of books, records, and property; compliance with law; tax payments; and so on. Other affirmative covenants range from insurance and inspection rights to the use of proceeds and pari passu ranking, that is, of equal seniority ranking.

Negative covenants, also known as incurrence covenants, require borrowers to either meet certain requirements before taking actions or refrain from taking certain actions that may negatively affect a borrower's ability to repay a loan or the value of the collateral. For example, lenders may restrict borrowers from issuing additional debt, regardless of seniority, to avoid claim dilution. Lenders also often prohibit borrowers from using assets as collateral for another loan – a “negative pledge.” Borrowers may be restricted from making large distributions to shareholders via dividend payments or stock repurchases. All of these actions provide lenders with a firm grip on corporate actions that may negatively affect their stake.

Financial covenants, also known as maintenance covenants, require a borrower to achieve a prespecified level of financial performance throughout the life of a loan. Financial covenants can be date‐specific, performance based, or a hybrid type. Date‐specific covenants test a borrower's financial condition on a specific date. Typical covenants include requirements for a borrower's tangible net worth, debt‐to‐equity ratio, current ratio, working capital level, and so on. They are mostly based on a firm's balance sheet information at a specific time. Performance‐based financial covenants, such as coverage ratios (interest coverage ratio, debt service coverage ratio, fixed charge coverage ratio), capital expenditure, and lease payments, tend to be “flow”‐based and rely on information from income statements and cash flow statements. The hybrid type, such as the debt to EBITDA ratio, relies on information from both the balance sheet and income statements, and can be a rolling measure over several quarters.6

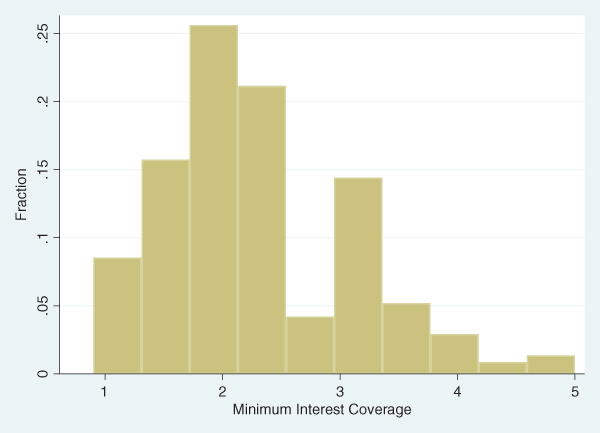

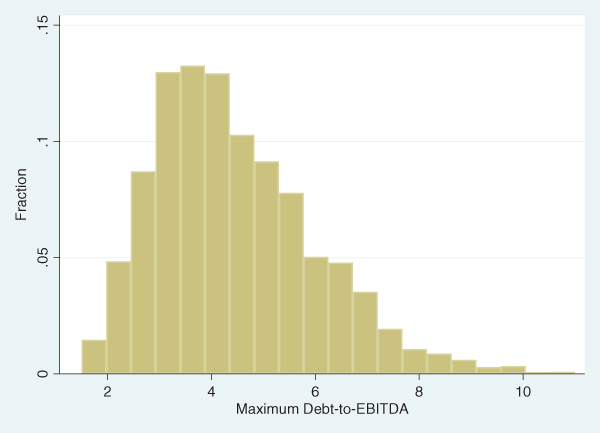

Figure 2.4a plots the histograms of interest coverage and Figure 2.4b plots debt‐to‐EBITDA covenants for all leveraged loans listed in Thomson Reuters' LPC Dealscan from 1996 to 2016. The figure shows that interest coverage, when required by the lender, tends to concentrate in the 1.5–3 range. The debt‐to‐EBITDA covenant typically requires the ratio to have the maximum value of 3–5.

FIGURE 2.4a Interest Coverage Covenant Distribution (U.S. Leveraged Loans, 1996–2016)

FIGURE 2.4b Debt‐EBITDA Coverage Covenant Distribution (U.S. Leveraged Loans, 1996–2016)

Source: Author's compilation based on Thomson Reuters LPC Dealscan.

Some leveraged loans carry affirmative and incurrence covenants, but not traditional maintenance covenants. These loans increasingly appear in periods of easier credit, such as prior to the 2008–2009 financial crisis. These “covenant‐lite” loans contain many borrower friendly terms. For example, they may allow an unlimited amount of debt so long as the borrower meets the incurrence test, or even allow unlimited dividends, subject to satisfying a leverage test. According to S&P LCD, these loans made up 75% of new institutional loans in 2017 and accounted for about 80% of the U.S. institutional leveraged loans as of February 2018. This represented a dramatic increase from 2010, when covenant‐lite loans constituted less than 10% of new institutional loans. The total outstanding amount of covenant‐lite loans stood at a record high of over $600 billion as of mid‐2017. Regulators showed concerns over the fast rise of covenant‐lite loans in the leveraged loan market from 2010 to 2014, which was perceived as a reflection of weakened bank lending standards.

Several academic studies examine the economic rationales for the fast development of covenant‐lite loans. Becker and Ivashina (2016) find that covenant‐lite loans are overwhelmingly used when the institutional ownership is high. They suggest that covenant‐lite loans mitigate bargaining frictions in loan syndicates by reducing the likelihood of ex post bargaining that is triggered by covenant violations. Further, Berlin, Nini, and Yu (2016) find that covenant‐lite loans are not used in isolation, and are usually structured together with a revolving facility that is not covenant‐lite. They refer to the structure with concentrated control rights assigned to revolving lenders as “split control rights.” Yet another positive view of covenant‐lite loans is that they are more likely to be used when moral hazard problems are less severe – empirically, Billett, Elkamhi, Popov, and Pungaliya (2016) show that they are more often used by firms that are larger and that have lower leverage, higher profitability, and better liquidity. Still, a primary concern with covenant‐lite loans is that a future performance decline might not trigger intervention by lenders to protect their interests. If the firm value were to fall significantly more prior to a default, lenders may not be adequately compensated for the risk of lower future recoveries.

Loan Contract Renegotiations

Loan contracts are designed in a state‐contingent manner to grant lenders strong control rights through ex post renegotiations. These contract terms are often renegotiated during the life of the loan contract. Amendments to the contract range from revisions to one single covenant to the change of the whole collateral package.

A growing number of academic studies (including Roberts and Sufi, 2009a; Denis and Wang, 2014; and Roberts, 2015) demonstrate that loan contracts are frequently renegotiated before their originally stated maturity. The timing of the renegotiation coincides with the arrival of new information regarding the borrower's credit quality, investment opportunities and collateral, and macroeconomic conditions. Besides modifications to pricing‐related items, such as interest rate, amount, and maturity, covenants are most often modified. This is intuitive because, at times, companies find their investments and financing strategies are constrained by existing covenants. These firms can either retire the old debt and issue new debt or negotiate with lenders to make amendments to covenants and grant waivers.

Default and Remedies

The precise definition of default is generally laid out in the “Events of Default” section of a credit agreement. These events typically include failure to pay principal or interest on time (payment default), false representation (defined in the “Representations and Warranties” section in a credit agreement), default on other debt (within cross‐default or cross‐acceleration clauses), insolvency or bankruptcy, and other events (e.g., invalidity of liens or guarantees, ERISA events, etc.).

Events of default are meaningless unless they are associated with remedies or actions that lenders can act on. They typically include stopping lending, terminating commitments, “accelerating” payments, demanding “cover” (cash collateral) for letters of credit, foreclosing on collateral, instituting suit for past‐due payments, and demanding payment from guarantors. In the event of default, lenders are not required to follow through on these actions, but they serve as an important consideration for staking out their bargaining positions against the borrower, shareholders, and junior creditors.

Covenant Violations

Covenant violations are triggered when a borrower violates one or more covenants (financial covenants, typically) laid out in the credit agreement. Covenant violations do not trigger actual default but are trip wires that allow the lender to gain control of the borrower. Covenant violations are often referred to as technical default.

Recent academic studies, including Dichev and Skinner (2002), Chava and Roberts (2008), Roberts and Sufi (2009a), Nini, Smith, and Sufi (2012), and a long list of follow‐up studies, empirically examine loan covenant violations and their effects on corporate investment and financing policies. These studies document that, because lenders set tight covenants initially, covenant violations occur relatively often. Such violations are not necessarily associated with financial distress. Rather, lenders use such defaults to gain indirect control of a borrower's major corporate policies by making amendments to the credit agreement. The borrower's capital investment, net debt issuance, and shareholder payout decline sharply after covenant violations. Interestingly, borrowers rarely switch lenders following a violation.

HIGH‐YIELD BONDS

High‐yield bonds are composed of bonds issued by two types of companies. The first type, referred to as “fallen angels,” are securities issued by companies that at one time (usually at issuance) were investment‐grade but, like most of us, get uglier as they age and “migrate” down to noninvestment‐grade or “junk” level status. When the modern age of the high‐yield market began in the late 1970s, just about 100% of this very small market was made up of these fallen angels. Fallen angels may be the result of consumer preference changes or technological transformation. For example, large retailers such as JC Penney and Sears used to be rated investment grade, but they were downgraded to junk due to changes in consumer spending patterns. The other source of high‐yield bonds is original‐issue securities, which receive a noninvestment grade rating at birth due to their aggressive capital structure and high‐risk nature. Examples are debt issued by LBOs, startups, and firms emerging from bankruptcy.

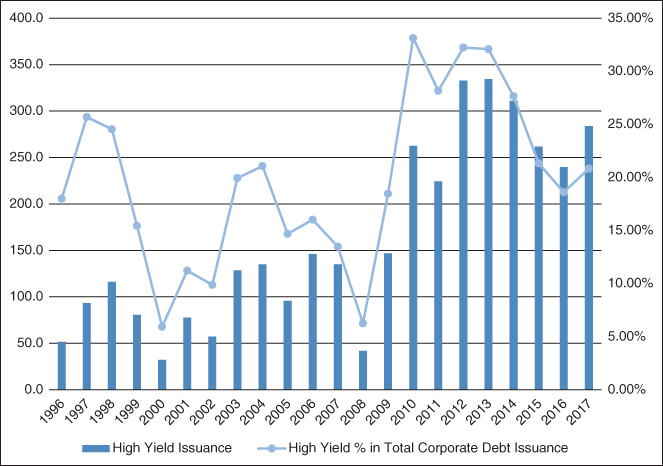

High‐yield bond offerings are not typically registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Most come to the market under the exception of Rule 144A – companies place bonds with investors privately and then register them with the SEC a few years later (or never register them with the SEC). High‐yield bond issuance is cyclical. However, as Figure 2.5 shows, the high‐yield markets have experienced an unprecedented boom since the 2008–2009 financial crisis (based on data from SIFMA), and the high‐yield market share of the total US corporate debt markets has remained around 20% to 30% in recent years. Major investors in this market are mutual funds, pension funds, insurance companies, and collateralized debt obligations (CDOs).

FIGURE 2.5 High‐Yield Bond Annual Issuance

Source: Based on data from SIFMA.

Two special types of high‐yield bonds are commonly issued by non‐investment‐grade companies: discount (zero coupon) notes and pay‐in‐kind (PIK) notes. Discount notes do not pay cash coupons and are issued at a discount to their face value. The value of a discount note increases as it moves closer to maturity. PIK notes allow speculative‐grade issuers to pay interest by issuing additional bonds (hence “in kind”) instead of cash. After the “interest” is paid, the next interest payment will be made on the original bonds plus those issued for the PIK payment. “Toggle” bonds are special types of PIK notes; they allow companies the option to either pay the notes in kind or pay cash. Toggle bonds have gained in popularity against traditional PIK notes in recent years. See Chapter 9 for a comprehensive discussion of the high‐yield markets.

DEBT SUBORDINATION

The priority of debt in the capital structure is determined by various factors, including seniority status, security and lien ranking, corporate organization structure, and guarantees. These factors could allow a class of seemingly senior debt to be ranked lower in priority than a class of junior debt in bankruptcy. In this section, we briefly describe the three major types of debt subordination.

Contractual Subordination

This refers to a situation where creditors of a particular class agree to contractually subordinate themselves in priority to another creditor group. Since bank loans are typically senior and secured, contractual subordination often refers to the inclusion of a subordination clause in a bond indenture.

The subordination clause typically specifies that one set of (subordinated) unsecured noteholders or bondholders agrees to subordinate its cash flow claims to another set of creditors. A standard subordination clause for a senior subordinated note, for example, would include the following provisions:

- The payment of obligations owing in respect to the notes is subordinated in right of payment to all existing and future senior indebtedness of the issuer;

- The notes are senior in right of payment to all existing and future subordinated indebtedness of the issuer;

- The notes in all respects rank pari passu in right of payment with all existing and future senior subordinated indebtedness of the issuer, and they will be senior in right of payment to all existing and future subordinated indebtedness of the issuer.

The description of the subordination is usually followed by an extensive set of definitions. For example, the subordination section would clearly state that, in the case of insolvency, bankruptcy, or liquidation, all senior indebtedness must be paid in full (most likely in the form of cash or equivalents) before subordinated obligations are paid. With a subordination clause in place, subordinated noteholders are contractually subordinated to senior debtholders.

Lien Subordination

Secured Lending and Lien Perfection Debt can be secured against assets of companies through the granting of collateral. Secured lenders are given security interests and legal rights to repossess and realize the collateral to satisfy their claims in the case of bankruptcy. However, because secured lenders are “stayed” from foreclosure in bankruptcy, they cannot repossess the collateral during bankruptcy reorganization; however, they receive adequate protections for their claims and enjoy the highest priority in the capital structure.

Pledgeable assets that can be used as collateral range from current assets to long‐term assets. They can be both tangible (such as real estate and equipment) and intangible (such as rights, patents, and other intellectual properties).7 For most secured debt, companies pledge a specific type of asset for secured borrowing. At times, companies may pledge substantially all their assets as collateral. Typically, a borrower and all lenders need to contractually agree (typically through a Guarantee and Collateral Agreement) that the security interest has been created and granted.

To properly secure an asset, lenders must “perfect” a lien – an interest in property to secure payment of a debt or performance of an obligation against the asset. Lenders need to verify that a borrower has publicly filed and stated that the beneficiary of the collateral has prior rights to the pledged collateral. Lenders must make a public announcement and record the pledge in a public registry. In practice, since secured transactions are governed by state law and the interpretation of Article 9 of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC), a lien is deemed to be “perfected” once a UCC financing statement has been filed in the office of the secretary of state in the state where the borrower is incorporated and a public announcement is made.

The timing of lien perfection matters to how debt claims are ranked in bankruptcy. If multiple creditor classes are using the same collateral as security, the date of perfection can be used for seniority ranking. Lenders should be concerned that perfection can lapse after several years or if the borrower changes its name or status.

Second‐ (Junior‐) Lien Loans The market for second‐lien loans, one of the most significant innovations in the U.S. leveraged loan market, has grown rapidly in the past two decades, from less than $1 billion annual issuance in the late 1990s to $40 billion in 2014. The popularity of second‐lien loans can be attributed to their advantages for the borrower compared to the issuance of unsecured notes. Second‐lien loans have better pricing, provide better access to investors who invest in secured loans (e.g., CLOs), and are easier to renegotiate (given their more concentrated ownership structure) than high‐yield bond debt. CLOs had been the predominant investors in second‐lien loans in the 2000s; however, over the past several years, the major investors have shifted to high‐yield funds and distressed hedge funds, which, as an investor base, account for more than 70% of annual issuance as of 2015.8

Second‐lien lenders typically have their rights restricted by first lien lenders through an intercreditor agreement. The agreement prohibits second‐lien lenders from exercising any rights regarding the collateral until the first lien lenders are paid in full. In nature, they are subordinated in lien to first‐lien lenders. Other salient features of the intercreditor agreement include provisions that require second‐lien lenders to waive rights (e.g., waivers to adequate protection) and vote along with the first lien lenders. Some of these waivers pertain only to the “standstill” period (typically 90–180 days after default). The primary goal of including these provisions is that the first lien lenders want the second‐lien lenders to be silent. Thus, second‐lien lenders are often referred to as the “silent seconds.”

Some of the provisions and restrictions for second‐lien lenders are specific to postbankruptcy issues. For example, first‐lien lenders may require second‐lien lenders' preconsent for firms to use cash collateral. They also want second‐lien lenders to remain silent to the lifting of automatic stay and the sale of collateral. The agreement may preclude the second‐lien creditors from providing DIP financing absent the first lien holders' approval. Because of the silent second provisions, second‐lien lenders effectively lose their separate vote for the credit agreement – they must support the agreement put forward by the first‐lien lenders. However, this may depend on whether the first‐lien and the second‐lien lenders are documented in one creditor agreement or separate agreements. Being treated as two lending facilities and drafted in separate contracts increases the likelihood that they will be treated as separate classes by a bankruptcy judge, allowing the second‐lien holders to have great opportunities to play an active role in the bankruptcy reorganization process.9 There are at times cases for a crossing lien and split collateral structure, where the first‐lien and the second‐lien lenders are structured as two separate credit facilities.10

Structural Subordination

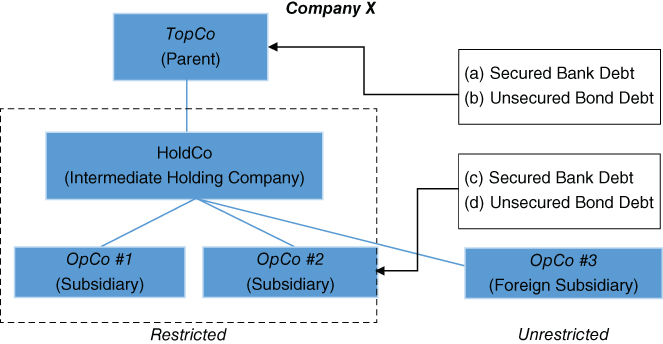

Corporate organizational structure matters to ranking the priority of debt and, thus, the potential debt recovery. If a borrower were a holding company with all real assets and operations at the subsidiary level, any debt incurred at the holding company level would be subordinated to debt incurred at the subsidiary level, regardless. This is referred to as structural subordination. In general, lenders want to be close to the real assets of a company to avoid structural subordination. We use the corporate organization of the company shown in Figure 2.6 to illustrate how structural subordination works.

FIGURE 2.6 Organization Structure and Debt Structure of Company X

Suppose Company X is a corporation with three levels of entities in its corporate reorganization structure. TopCo is the parent company that directly wholly owns HoldCo, an intermediate holding company that owns three subsidiaries, two domestic and one in a foreign country. Neither TopCo nor HoldCo owns real assets or operations, except for their equity ownership of the owned entities. The three subsidiaries own and control all assets and operations. Suppose there are four classes of debt issued by various entities of the company as a whole. TopCo has secured bank borrowing (a), with all its assets used as collateral, and an unsecured debt (b) outstanding. Similarly, OpCo #2 has a secured loan facility (c) and an unsecured debt (d). How do we rank the seniority of the four classes of debt?

The general principal is to follow how close the debt is to operations and assets – the closer, the better. The secured bank debt (c) is secured by the operations and assets of OpCo #2 and is clearly ranked highest in seniority. Debt (d), while unsecured, is still at the operating company level and has access to cash flows; therefore, it is ranked second. Bank debt (a), which is essentially secured by TopCo's equity ownership of the three OpCos through the intermediate holding company HoldCo, acts as a residual claim to debt classes (c) and (d) and, therefore, is ranked third in the capital structure. Finally, unsecured debt (b) is the last in line. Secured bank debt (a) and unsecured debt (b) are said to be structurally subordinated by debt (c) and debt (d), while debt (d) would be contractually subordinated to (c), based on existing security agreements.

Note that the credit agreement for the loan (c) or indenture of bond debt (d) may contain restrictions and covenants that apply to all other subsidiaries and even HoldCo. These entities, shown in the dashed box, are known as the restricted subsidiaries. Those that are outside the box, often foreign subsidiaries, are unrestricted subsidiaries and are not bound by the credit agreement.11

Debt guarantees may complicate the priority ranking of debt. There are, in general, three types of guarantees: upstream (subsidiary guaranteeing debt that is issued by the parent or holding company), downstream (the holding or parent company guarantees debt that is issued by a subsidiary), and cross‐stream (one subsidiary guarantees debt that is issued by another subsidiary). Suppose there is an upstream guarantee from OpCo #2 to the debt issued by TopCo. If both OpCo #1 and OpCo #2 were insolvent, the unsecured debt obligations of OpCo #2 and debt obligations of TopCo would share the same level of priority and rank pari passu. Therefore, an upstream guarantee effectively improves the recovery of debt of TopCo.