CHAPTER 3

An Overview of the U.S. Bankruptcy Process

To best understand the U.S. bankruptcy process, it is helpful to briefly review the previous statutes and codes that have helped to form the present system. In this chapter, we trace the developments leading to the current U.S. Bankruptcy Code. We then provide a comprehensive summary of the most important features of Chapter 11 of the Code, which are key to enabling the reorganization and survival of firms via court supervised bankruptcy proceedings.

EVOLUTION OF THE U.S. BANKRUPTCY PROCESS

The Constitution empowers the U.S. Congress to establish uniform laws regulating bankruptcy. By virtue of this authority, various acts and amendments have been passed, starting with the Bankruptcy Act of 1800. A number of revisions were enacted and led to the establishment of the Bankruptcy Act of 1898, known as the Nelson Act. These early acts in the nineteenth century established the modern concepts of debtor‐creditor relations. The three most important Bankruptcy Acts subsequently passed since the beginning of the twentieth century are: in 1938, the Chandler Act, replacing the inadequate earlier statute; in 1978, the Bankruptcy Reform Act of 1978, providing the standard until recently; and in 2005, the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act.

Equity Receiverships of 1898

The Bankruptcy Act of 1898 provided only for a company's liquidation and contained no provisions allowing corporations to reorganize and thereby remain in existence postbankruptcy. Reorganization could be effected through equity receiverships, which were developed to prevent disruptive seizures of property by dissatisfied creditors who were able to obtain liens on specific properties. Receivership in equity is not the same as receivership in bankruptcy. In the latter case, a receiver is a court agency that administers the bankrupt's assets until a trustee is appointed.

Equity receivership was extremely time‐consuming and costly, as well as susceptible to severe injustices. Courts had little control over the reorganization plan, and the committees set up to protect security holders were usually made up of powerful corporate insiders who used the process to further their own interests. The initiative for equity receivership was usually taken by the company in conjunction with a friendly creditor. There was no provision made for an independent objective review of a plan. Since ratification required majority creditor support, it usually meant that companies offered cash payoffs to powerful dissenters to gain their support. The procedure led to long delays and charges of unfairness, and essentially was replaced by provisions of the temporary Bankruptcy Acts of 1933 and 1934.

The Chandler Act of 1938

In 1933, a new bankruptcy act was hastily drawn up and enacted during the great depression. This act was short‐lived; in 1938 it underwent a comprehensive revision and was thereafter known as the Chandler Act. For our purposes, the two most relevant chapters of the Chandler Act were those related to corporate bankruptcy and to attempts at reorganization, namely Chapter XI and Chapter X.

A Chapter XI arrangement was a voluntary proceeding and applied only to the unsecured creditors of corporations. The debtor's petition for reorganization usually contained a preliminary plan for financial relief. The court had the power to appoint an independent trustee or receiver to manage the corporate property or, in many instances, to permit the old management team to continue its control throughout the proceedings. During the proceedings, a referee would call the creditors together to go over the proposed plan and any new amendments that had been proposed. If a majority in number and amount of each class of unsecured creditors consented to the plan, the court could confirm the arrangement and make it binding on all creditors. The plan typically provided for a scaled‐down creditor claim, a composition of claims, and/or an extension of payment over time. New financial instruments could be issued to creditors in lieu of their old claims.

The prospect of continued management control and reduced financial obligations made Chapter XI particularly attractive to incumbent management. Further, the debtor could borrow new funds that had preference over all unsecured indebtedness (essentially debtor‐in‐possession financing – see the discussion later in this chapter). When successful, Chapter XI arrangements were of relatively shorter duration and thus less costly than a more complex Chapter X proceeding.

Chapter X proceedings applied to publicly held corporations, except railroads, and to those that had both secured and unsecured creditors. The process could be initiated voluntarily by the debtor, or involuntarily by three or more creditors with total claims of $5,000 or more. In most cases, a Chapter XI was preferred by the debtor because Chapter X automatically provided for the appointment of an independent, disinterested trustee. The bankruptcy petition for a Chapter X had to contain a statement explaining why adequate relief could not be obtained under Chapter XI. The aim of this requirement was to make a Chapter X proceeding unavailable to corporations having simple debt and capital structures.

The independent trustee was charged with developing and submitting a reorganization plan that was “fair and feasible” to all the parties involved, including creditors as well as preferred and common stockholders. In addition, the trustee was charged with the day‐to‐day management responsibilities, but usually delegated such tasks to the management (old or new). In most Chapter X proceedings, the trustee was aided by various experts, as well as by committees representing the creditors and stockholders, to develop and present a reorganization plan. In the case of railroad bankruptcies, the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) was charged with this task.

Another important participant in Chapter X proceedings was the SEC. The SEC was charged with rendering an advisory report if the debtor's liabilities exceeded $3 million, but the court could ask for SEC assistance regardless of liability size. The advisory report usually took the form of a critical evaluation of the reorganization plan submitted by the trustee and an opinion as to the fairness and feasibility of the plan. Preparing the report involved comprehensively valuing the debtor's existing assets and comparing the value with the various claims against the assets. Ultimately, the decision whether the firm was permitted to reorganize and submit the plan for final acceptance rested with the federal judge.

The Chandler Act provided that the Chapter X reorganization plan, after approval by the court, be submitted to each class of creditors and stockholders for final approval. Final ratification required approval of two‐thirds in dollar amount and one‐half in number (or a majority in number, in the case of Chapter XI) of each class of creditors and stockholders (if total liabilities were less than total asset value). If the plan, as accepted by the court, completely eliminated a particular class – such as the common stockholders – the excluded group had no vote in the final ratification, though it could always file a suit on its own behalf. Common stockholders were eliminated when the firm was deemed insolvent in a bankruptcy sense, that is, when the liabilities exceeded a fair valuation of the assets.

Up until 1978, the Chandler Act continued to provide for the orderly liquidation of insolvent debtors under court supervision. Regardless of who filed the petition, liquidations were handled by referees who oversaw the operation until a trustee was appointed. Payments of receipts usually followed the so‐called absolute priority doctrine, under which claims with higher priority had to be paid in full before lower priority, or subordinated, claims could receive any funds at all. The liquidation fate was primarily observed for small firms. However, reorganization attempts of some larger firms were not successful, and liquidation often eventually occurred. A glaring example of a failure to successfully reorganize was the billion‐dollar W.T. Grant case. The firm voluntarily filed under Chapter XI in 1975 and attempted to reorganize rather than waited for any of its creditors to compel it to file under Chapter X. However, the company was forced to liquidate several months later in 1976. In contrast, several other large reorganizations of that era were successful, including the billion‐dollar (in assets) United Merchants & Manufacturing Chapter XI proceeding in July 1977.

The Bankruptcy Reform Act of 1978

Forty years after the passage of the Chandler Act, Congress passed the Bankruptcy Reform Act of 1978, which revised the administrative and to some extent the procedural, legal, and economic aspects of corporate and personal bankruptcy in the United States. The decision to reform reflected a near doubling in the annual rate of bankruptcy filings over the prior 10 years, the largest increase being in personal bankruptcies. Further, referees under the Chandler Act often had problems administering their duties and made suggestions for substantial improvement of the Act.

The 1978 Act created a U.S. Bankruptcy Court in each of 94 districts where there was a U.S. Federal District Court. The new court system was not fully established until April 1, 1984. The bankruptcy court is given exclusive jurisdiction over the property, wherever the debtor is located. All cases under the code and all civil actions and proceedings arising from its enforcement are held before the bankruptcy judge unless he or she decides to abstain from hearing a particular proceeding that is already pending in the state court or in another court that is believed to be more appropriate. Bankruptcy judges were initially appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate. Since the Bankruptcy Amendments and Federal Judgeship Act of 1984, the court of appeals for the circuit in which the district is located has been responsible for the appointment of bankruptcy judges for that district. The term of appointment for bankruptcy judges is 14 years. Also, under the 1978 Code, the role of the SEC as the public's representative has greatly diminished.

The new act went into effect on October 1, 1979, and is divided into four titles, with Title I containing the substantive and much of the procedural law of bankruptcy. This part, known as the “Code,” is divided into eight chapters: Chapter 1 (General Provisions), Chapter 3 (Case Administration), and Chapter 5 (Creditors, the Debtor and the Estate), which apply generally to all cases; and Chapter 7 (Liquidation), Chapter 9 (Adjustment of Municipality Debt), Chapter 11 (Reorganization), Chapter 13 (Adjustment of Debts of Individuals with Regular Income), and Chapter 15 (U.S. Trustee Program), which apply to specific debtors and procedures.

Chapter 7: Liquidation Chapter 7 provides for an orderly liquidation supervised by a court appointed trustee. Chapter 11 enables corporations to reorganize under bankruptcy court supervision, and is the main focus of our text. Economically, liquidation (reorganization) is justified when the value of the assets sold individually is greater than (less than) the going concern value of the business.

The filing is commenced either by firms filing a voluntary petition or by creditors filing an involuntary petition against the debtor in the bankruptcy court in the judicial district where the company is incorporated, resides, or has its principal place of business or assets. Filing for Chapter 7 triggers an automatic stay, which freezes all collections against the firm. A trustee is then appointed to replace the company's management. The trustee operates the debtor's business for a limited period if doing so is in the best interests of the bankruptcy estate and is consistent with its orderly liquidation. Proceeds from the liquidation are distributed to creditors according to the absolute priority rule (APR). After liquidation, the firm ceases to exist.

Chapter 7 has been more often used by small businesses than Chapter 11. Figure 3.1 shows that there were twice as many Chapter 7 filings as Chapter 11 filings by U.S. businesses between 1990 and 2017. This result is intuitive as many small businesses have no hope for rehabilitation, and perhaps no ability to overcome the relatively larger costs of a Chapter 11 proceeding (see Chapter 4 herein). In contrast, Chapter 7 has rarely been filed by large U.S. public firms, which account for less than 10% of such bankruptcy filings (Source: bankruptcydata.com). Chapter 7 is sometimes used by larger corporations that initially enter Chapter 11 but are unable to reach a viable reorganization plan, or that need to distribute cash proceeds and any remaining assets to claimants after the firm's assets have been substantially sold in Chapter 11.

FIGURE 3.1 Number of Business Chapter 11 and Chapter 7 Filings

Source: United States Courts Form F-2 (http://www.uscourts.gov/).

Chapter 11: Reorganization An extremely important change in the 1978 Code involved the new Chapter 11 for business rehabilitation, consolidating much of the older Chapters X and XI. Under Chapter 11, the management as “debtor‐in‐possession” continues to operate the business unless the court orders a disinterested trustee for cause, or it is determined to be in the best interest of the creditors and/or the owners. Cause includes fraud, dishonesty, incompetence, or gross mismanagement, either before or after commencement of the case.

U.S. law imposes no obligation on a company's board to commence court proceedings upon insolvency (see Chapter 8 herein). When a firm does file under Chapter 11, there is no required insolvency test, either on a cash flow basis or balance sheet basis. The vast majority of filing debtors, however, are insolvent in some sense. In some cases, contingent events, which could cause insolvency, have been argued successfully as reasons to seek protection under the Bankruptcy Code. Examples of these contingent events include a number of Chapter 11 filings due to asbestos litigations and tort claims in the early 2000s.1

The 1978 Code contains a number of provisions important in enabling the debtor to reorganize, including but not limited to: an automatic stay; an exclusive period during which only the debtor can propose a plan of reorganization; the ability to use cash collateral and/or obtain postpetition financing; the ability to assume or reject leases and other executory contracts; the ability to sell assets free and clear of liens; the ability to retain and compensate key employees; and the ability to reject or renegotiate labor contracts and pension benefits. These specific features are explained in detail in the second portion of this chapter.

Most firms that file for Chapter 11 are not ultimately reorganized. In some cases, while at the time of filing it is estimated that the going concern value of a firm exceeds its liquidation value, the business might continue to deteriorate to such an extent that liquidation become inevitable. Many small firms are unable to successfully reorganize under Chapter 11. A firm can confirm a liquidating Chapter 11 plan, or convert the case to a Chapter 7 liquidation (Chapter 7 herein discusses evidence regarding bankruptcy case outcomes).

Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005

The U.S. Congress enacted a revised Bankruptcy Act on April 20, 2005, called the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005 (BAPCPA). Although the most controversial and publicized aspects of the Act impact consumer (personal) bankruptcies by making the laws significantly less debtor friendly, the new Act has many important provisions that impact corporate bankruptcies. Examples include amendments to provisions for the debtor's exclusivity period for proposing a reorganization plan, the composition of creditors' committees, treatment of vendors, treatment of commercial leases, the use of key employee retention plans, and employee retirement benefits.2 In general, as with consumers, the new Act is viewed as more favorable to creditors. Most of these provisions went into effect on October 20, 2005, six months after the Act was passed.

In addition to major changes to specific sections of the 1978 Code, the BAPCPA enacted a new Chapter 15 on cross‐border insolvencies. Chapter 15 is the successor to Section 304 of the 1978 Bankruptcy Code, and is based on the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) “Model Law” which provides a legal framework for cross‐border cooperation and communication between courts (see Chapter 8 for a detailed discussion of cross‐border insolvency).

A PRIMER ON CHAPTER 11

In this section, we explain some of the most important issues in Chapter 11 reorganization today. While we do not intend to provide a full legal reference, we describe the most up‐to‐date practice after the enactment of the 1978 Code, with amendments made by BAPCPA.

Venue Choice

A firm may voluntarily file for bankruptcy as long as it does so for legitimate business reasons. However, any three or more creditors holding unsecured claims aggregating to at least $15,775 (as of 2017) may submit an involuntary petition against the borrower under Chapter 7 or Chapter 11. Firms may choose to make a voluntary filing in a different bankruptcy court after creditors file an involuntary petition. For example, in the Caesars Entertainment Operating Company case, an involuntary petition was filed by three major creditors – Appaloosa Investment, OCM Opportunities Fund, and Special Value Expansion Fund – on January 12, 2015, in the District of Delaware. The company filed a voluntary petition on January 15 in the Northern District of Illinois. The Delaware court transferred the involuntary case to the Illinois court two weeks later.

Where is a company required to file its bankruptcy petition? The U.S. system provides a degree of latitude to some debtors in choosing the location or “venue” for the case. According to the U.S. Code Title 28 Chapter 87 Section 1408, a U.S. business can file for bankruptcy in one of the following four locations: (1) the place of domicile or residence, which can be the state of incorporation; (2) the principal place of business, which tends to be the corporate headquarters; (3) the principal place of assets; or (4) any district where a bankruptcy case is pending against the firm's affiliate.

Larger firms, which typically conduct business nationwide and have assets located in multiple states, therefore have some ability to select the court for their filing. For example, on the morning of June 1, 2009, Chevrolet‐Saturn of Harlem, a dealership in Manhattan owned by General Motors itself, filed for bankruptcy protection in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York, followed by General Motors Corporation (the main GM in Detroit) and other GM subsidiaries filing in the same court. Some scholars (e.g., LoPucki, 2005) argue that this practice of “forum shopping” enables firms to choose debtor‐friendly venues, leading to inefficient reorganizations in some cases. Others argue that sophisticated debtors choose courts that have more expertise in dealing with complex cases.

In the two and one half decades between 1990 and 2017, more than half of U.S. public firms with at least $50 million in book assets filed their petitions in only two courts: the U.S. Bankruptcy courts for the District of Delaware and Southern District of New York (source: bankruptcydata.com). The topic continues to be debated, to the point where two U.S. senators introduced a bill in January 2018, the Bankruptcy Venue Reform Act, to prevent forum shopping.3

Judge Assignment

After a petition is filed, a judge is assigned to the case within hours. The majority of bankruptcy courts state that they use a blind rotation system to randomly assign cases to one of the active bankruptcy judges in their divisional office. However, courts that at times have a large caseload relative to their capacity have recruited district judges, visiting bankruptcy judges from other districts, or retired bankruptcy judges to oversee cases. For example, seeing a sharp rise in the number of bankruptcy filings from the late 1990s to the early 2000s, Delaware employed all three types of judges.

Although some people are skeptical that judges are truly randomly assigned, a few studies provide empirical evidence that bankruptcy case characteristics are independent of judge characteristics (e.g., Bernstein, Colonnelli, and Iverson, 2018; Chang and Schoar, 2013; and Iverson, Madsen, Wang, and Xu, 2018). These studies also examine the effect of judges' experiences and preferences on bankruptcy outcomes. They find that judges' on‐the‐bench experiences have a strong impact on bankruptcy duration, the probability of emergence, and the debtor's post‐emergence performance, and that their pro‐debtor preferences strongly explain the propensity to grant or deny certain motions.

Automatic Stay

An important aspect of reorganization law is to resolve the “collective action” problem by preventing individual creditors from taking actions that would jeopardize reorganization efforts and allowing the debtor to continue running the business without direct interference from creditors (see, for example, Baird, 2010). This is accomplished with Section 362 of the Bankruptcy Code, which governs the automatic stay in bankruptcy. Specifically, no claimant can foreclose on collateral, collect payment, enforce a judgment from a previous lawsuit, create or perfect a lien on property, sue to recover past claims (including taxes owed against the debtor), or refuse to pay an amount owed to the debtor once the firm is under court supervision in bankruptcy.

There are some limited instances where a judge may grant lifting the stay.4 Under the Code (Section 361), the debtor is required to ensure that the value of the secured creditors' claims are “adequately protected” through the reorganization process; the judge may grant relief from the automatic stay upon observing evidence of “cause, including the lack of adequate protection of an interest in property of such party in interest.” The adequate protection provision requires that if using, leasing, or selling a secured lender's collateral results in a decrease in its value, or if the debtor grants a security interest in the collateral to a new lender, the debtor must compensate the secured lender with a cash payment equal to the decrease in the collateral value, an additional or a replacement lien on other assets, or the “indubitable equivalent” of the lender's interest in the collateral.

Operating in Bankruptcy: The Concept of the Debtor in Possession (DIP)

The United States Trustee Program, a division of the U.S. Department of Justice, supervises the administration of a bankruptcy case and serves as the “watchdog over the bankruptcy process.”5 The United States Trustee is appointed and supervised by the Attorney General and charged with the responsibility of supervising the administration of a bankruptcy case. Specific responsibilities of the U.S. Trustee include the following, each of which we describe in further detail in this chapter: appointment of a trustee in Chapter 7 cases and some Chapter 11 cases; taking legal action as needed to enforce the requirements of the Bankruptcy Code; reviewing professional fees; appointing an unsecured creditors' and other committees for the case; and reviewing disclosure statements. Their primary objective is to make sure that the debtor is operating in good faith and in conformity with the Bankruptcy Code and other laws.

Despite this oversight, Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code presumes that managers will remain in possession and control of a corporate debtor, and continue to operate the business. In doing so, the “debtor in possession” or “DIP” has a fiduciary duty to protect and preserve the assets of the bankruptcy estate and to administer them in the best interest of the creditors. Operating the ongoing business requires the use of the debtor's assets, sales and leasing of property, and so on. The debtor is able to conduct these activities so long as they are “in the ordinary course of business.” Transactions beyond the reasonable day‐to‐day business or customary practices, such as the sale of an essential business division, require approval of the court and potential intervention by the judge and/or creditors.

“First Day Motions” and Events Early in the Case

Chapter 11 provides certain immediate protections for the debtor, such as the automatic stay. Further, the debtor's counsel typically seeks a number of court orders in the first days of the case to facilitate the transition into bankruptcy and minimize disruption to operations. Typical motions are to maintain bank accounts and cash management procedures, to approve payments for prepetition wages and to critical vendors (suppliers), to retain advisors and professionals, and for the use of cash collateral and approval of postpetition financing. Other important decisions, including the appointment of committees and rejection or assumption of unexpired contracts such as leases, are made within a short time of the filing.

Treatment of Vendors A vendor that has not received payment for goods delivered to an insolvent customer has rights to get back or “reclaim” those goods under the Uniform Commercial Code's reclamation statute (UCC Section 2‐702), as well as provided for under the BAPCPA (Section 546(c)). If the customer has filed for bankruptcy, vendors enjoy a reclamation period for goods delivered up to 45 days after shipment or up to 20 days after the customer's bankruptcy filing (if the 45‐day period ended after a customer's bankruptcy filing). If the vendor fails to provide notice of its reclamation claim, it can still assert an administrative priority claim for the value of goods received by the debtor within 20 days prior to bankruptcy filing.

Given these complex rules, and the uncertainty of reclaiming goods or being repaid prior to the resolution of the bankruptcy case, vendors are very likely to tighten their trade credit policy as a customer becomes financially distressed and its chances of a bankruptcy filing rise. This can exacerbate a distressed firm's financial condition, if not triggering the filing itself. For example, when a news story published in September 2017 reported that Toys 'R' Us was considering a Chapter 11 filing, nearly 40% of vendors refused to ship goods without cash payment, precipitating a liquidity crisis for the firm.6

Once the firm has filed for bankruptcy, vendors may refuse to continue to provide goods unless their prepetition invoices are paid in full. Therefore, critical vendors are given preferential treatment for their claims over other unsecured creditors. DIP financing can provide the funding to make payments to vendors, and so to some extent alleviate vendor concerns for shipping goods after the filing date. However, motions to approve these payments are often subject to objections filed by the unsecured creditors that are effectively subordinated. For example, in the Kmart 2002 bankruptcy case (Gilson and Abbott, 2009), the company sought to pay prepetition claims to more than 2,000 vendors, worth more than $300 million. The judge's order was challenged by some of Kmart's unsecured creditors, leading to the ultimate rejection of the critical vendor payment by the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals.

Utilities that provide essential services to the debtor are treated differently than typical commercial vendors. Under the BAPCPA, the debtor must provide “adequate assurance of payment” to these providers in the form of a cash deposit, letter of credit, prepayment, or surety bond within 30 days of a bankruptcy filing (Section 366).

Retaining Professionals Financial and legal professionals provide a number of services for the debtor. These include (but are not limited to) negotiating with creditors, building financial models and valuation analyses, performing liquidation analyses, capital raising efforts, strategic business analyses, and employee retention efforts. See also Figure 4.1, describing the roles of professionals often retained in bankruptcy cases.

Professional fees and expenses incurred after the filing of the case are granted the legal status of an administrative expense (Section 503(b)). These fees have priority in payment over any other unsecured claims. For fees incurred prior to filing, professionals can waive prepetition claims and apply to be paid as an administrative expense. Attorneys and financial advisors are typically compensated on a time basis. However, financial advisors' compensation structure may include incentive bonuses, known as a restructuring fee or success fee, that are paid out to advisors upon the completion of a case, such as consummation of a restructuring or a sale. These fees, at times, add up to a large amount (see Chapter 4 herein for a detailed discussion on bankruptcy costs).

Under the old 1978 Bankruptcy Code, most of the large investment banks that participated in continuous underwritings of stocks and bonds for corporations were essentially prohibited from advising debtors who file for bankruptcy protection. This restriction was due to the “disinterestedness role” regarding any prior activities for three years before the filing for the debtor, regardless of whether such securities were still outstanding. The disinterestedness standard was reduced after BAPCPA because the old rule was repealed. Under Section 327 of the current Code, professionals can be retained so long as they are not found to be conflicted based on past activities. For example, an individual elected to the board or who held a prior management position with the firm cannot be retained as a professional. More broadly, an entity found, by reason of any relationship to or interest in the debtor, to have an interest adverse to the interests of the estate or any class of creditors or equity holders cannot be retained.

Financing in Chapter 11: Cash Collateral and DIP Financing Making payments for postpetition and even some prepetition expenses (for wages or to vendors, for example) is critical to debtor's ongoing business and successful reorganization in bankruptcy. The debtor also needs sufficient liquidity to fund working capital, maintenance and repair expenses, and payments for professionals during the case. Such payments require use of the debtor's cash, but that cash may already serve as collateral for secured claims. One important source of funds may be to access cash that already serves as collateral for secured claims. Section 363(c) of the Code specifies that the debtor may not use, sell, or lease cash collateral unless “each entity that has an interest in such cash collateral consents” or “the court, after notice and a hearing, authorizes such use, sale, or lease.” A second important source of funds is DIP financing.

Section 364 of the Code grants the debtor and the trustee the power to obtain postpetition credit with court approval. Specifically, the debtor is encouraged to obtain unsecured financing as an administrative expense. If the debtor is unable to obtain unsecured credit, the court may authorize the debtor to obtain a special form of postpetition credit known as DIP financing. A DIP loan is credit (1) with priority over any or all administrative expenses—a “super‐priority” administrative claim, (2) secured by a lien on property that is not otherwise subject to a lien, or (3) secured by a junior lien on property that is subject to a lien. The court can also authorize credit to be secured by a senior or equal lien on property that is already subject to a lien – the “priming lien” provision – only if credit would be unavailable otherwise and the prepetition lien that is subordinated (or primed) by the DIP loan is adequately protected.

The proportion of large U.S. companies in Chapter 11 that took DIP loans grew from less than half in the 1990s (Bharath, Panchapegesan, and Werner, 2010; Dahiya, John, K., Puri, and Ramırez, 2003) to two thirds after the turn of the century (Gilson, Hotchkiss, and Osborn, 2016; Li and Wang, 2016). There has been tremendous interest from both practitioners and academics regarding various aspects of these loan contracts.7 Companies that need immediate access to this type of loan typically file a DIP financing motion to the court on the day of, or shortly after, the bankruptcy petition.

Eckbo, Li, and Wang (2018) provide a comprehensive study of specific features of 407 loan facilities obtained by large public U.S. firms from 2002 to 2014. DIP loans usually take the form of revolving lines of credit, accompanied by a term loan and/or a letter of credit. The tenure of the loan is short term, typically ranging between one month and two years, suggesting that the funds are intended to match cash flow cycles and provide working capital, as well as to pay for operating expenses. In addition to interest costs, lenders can charge various fees. The total cost of the loan (spread and fees included) can be as high as 20%. In addition, the DIP contract may include restrictive covenants and required payments based on “milestones” such as filing a plan and disclosure statement or completing a sale of assets by a certain date. Thus, while DIP loans can be an important source of financing during the restructuring process, they may also serve as a power tool for senior lenders to exercise control over bankrupt companies.

Who provides the DIP financing? Prepetition lenders may gain an advantage by leading the arrangement of DIP financing as they can control collateral and be in a better position to recover their prebankruptcy exposure. Some DIP contracts may require the borrower to use part of the proceeds to repay the prepetition loan. The ability to “roll‐up” some or all of prepetition loans into the DIP loan can be attractive to prepetition lenders. Lenders that specialize in distressed debt financing includes commercial banks, asset‐backed lenders, investment banks, and alternative investors such as hedge funds and PE firms (Li and Wang, 2016).8 Some specialized investors provide DIP financing with the goal of positioning themselves as the future owners of the company, by converting the loan into a majority equity stake when the firm is restructured – a so called “loan‐to‐own” strategy.

While lending to a firm in bankruptcy requires specialized expertise, DIP lending is remarkably not a very risky endeavor given the minimal loss rates and the large spreads and fees charged (see Moody's, 2008). The most publicized loss to a lender on a DIP loan occurred in the 2001 WinStar bankruptcy, with DIP lenders' recovery in the range of 20–30%. Since then, according to Moody's, there has been no major default on a DIP loan except in in the case of ATP Oil & Gas Corp., where the DIP facility was deemed impaired.9 Even in this case, the eventual recovery to the DIP lenders was close to par. DIP loans have become increasingly attractive of late, with the active involvement of both traditional financial institutions and alternative investors. For example, in the Westinghouse (2017) case, there were 32 potentially interested financing parties and 14 of them submitted binding offers for the DIP loan.10

What are the effects of DIP financing on Chapter 11 outcomes? Conceptually, DIP financing enables the debtor to remain liquid during the most difficult days after filing and to invest in positive NPV projects that would not have been possible without the additional credit. Detractors of this type of financing might argue that it leads to overinvestment, giving managers the incentive and means to accept extremely risky or negative NPV projects. Empirical evidence from Dahiya, John, Puri, and Ramirez (2003) shows that DIP financing has a positive correlation with the eventual likelihood of reorganization, and that firms that obtain DIP financing from existing lenders tend to spend less time in bankruptcy.

Appointment of Committees The U.S. Trustee is responsible for the appointment of an official committee to represent the interests of unsecured creditors (the “UCC”). Importantly, the UCC's costs for professional advisors, such as attorneys or accountants, are paid by the debtor. The UCC ordinarily consists of unsecured creditors holding the seven largest unsecured claims who are willing to serve. The UCC does not control the business and assets of the debtor, but rather consults with the debtor on administration of the case and monitors the business operation. Specifically, the Code (Section 1103) permits the UCC to: review and discuss the progress of the case with the management team, investigate the financial condition and operation of the business, participate in the formulation of a reorganization or liquidation plan, ask the court to appoint a trustee or an examiner, and request that the court dismiss a case or convert a case to Chapter 7. The UCC typically files objections with the court for actions taken by the debtor they deem to negatively affect enterprise value and debt recovery, for example for approval of executive retention and incentive bonuses or exclusivity extensions. At times, ad hoc committees of creditors are formed when there is no official committee appointed, or when dissident debt holders do not want to join the official committee. However, the cost of professionals hired to assist an ad hoc committee is typically borne by the committee itself.

Academic studies show that the UCC is formed in less than half of Chapter 11 cases with over $10 million in assets (Waldock, 2017). The members of the UCC are mostly trade creditors, though hedge funds, private equity funds, and other activist investors also often seek representation. Their presence occurs in over 30% of the largest Chapter 11 cases filed from the late 1990s to early 2010s (Goyal and Wang, 2017; Jiang, Li, and Wang, 2012).

Because Chapter 11 affects the interest of claimants besides unsecured creditors, the U.S. Trustee or the court has the discretion to appoint additional committees as appropriate. If such a committee is appointed, the bankruptcy estate pays its fees and expenses. Most common is an official equity committee, but even this occurs in less than 10% of Chapter 11 cases of large U.S. public firms in the past two decades (Goyal and Wang, 2017). Appointment of an equity committee considers several factors including whether there is any substantial likelihood of a meaningful distribution to equity holders, which may be unlikely for a more severely insolvent debtor.

Replacing Management with an Independent Trustee It is possible under the Bankruptcy Code (Section 1104) that management is replaced by a court‐appointed independent trustee (not to be confused with the U.S. Trustee's office) if there are “reasonable grounds to suspect” that the debtor's current CEO, CFO, or board members participated in “fraud, dishonesty, or criminal conduct in the management of the debtor or the debtor's public financial reporting either before or after the commencement of the case.” When appointed by the court, the trustee takes control of the business, displacing the DIP. While required in a Chapter 7 liquidation, the appointment of a trustee in Chapter 11 cases is not common, and will occur only by the court on its own initiative or after a motion brought by the US Trustee or a party of interest. In many cases, the board of directors will have already removed officers of the company prior to entering Chapter 11, avoiding the disruption of a trustee being appointed postpetition. It is also possible that the U.S. Trustee recommends a court appointed examiner to investigate specific issues of fraud or mismanagement. While the use of an examiner is rare, it has been important in some large and significant Chapter 11 cases, including Enron and Lehman Brothers.

Rejection/Assumption of Leases and Other Executory Contracts An executory contract is a contract between the debtor and another party under which both sides still have important performance remaining. Common examples include real estate leases, equipment leases, development contracts, and licenses to intellectual property. Section 365 allows debtors to choose whether to keep (“assume”), abandon (“reject”), or transfer (“assume and assign”) their executory contracts, within time limits provided by the Bankruptcy Code.

A controversial change under the 2005 BAPCPA shortened the time for a debtor to reject a lease to within 120 days of filing, with the bankruptcy court permitting only one 90‐day extension beyond that (without landlord consent). A contract is deemed rejected if the debtor does not assume the contract by the deadline. Critics have argued that the accelerated timeframe for these decisions does not provide debtors with sufficient time to analyze performance and make adequate business decisions regarding these contracts. This and other changes under BAPCPA have been blamed for contributing to the failure of reorganization attempts of several large retailers, such as Circuit City in 2010, and other firms that have entered bankruptcy with a large number of commercial leases.

If a lease is rejected, the debtor can walk away from its obligations under the contract and the lessor will be entitled to an unsecured prepetition claim against the debtor, in an amount equal to the greater of one year's rent or 15% of unpaid rent on the unexpired lease (not to exceed three years' rent). Such terms start on the earlier of (1) the petition date or (2) the date on which the lessor repossesses the leased property, or the lessee surrenders it. In contrast, all prepetition and postpetition obligations for those leases that the debtor assumes become administrative expense priority claims. The debtor also has the right to assume and assign a lease to a third party, commonly a buyer of some assets, as long as the buyer is expected to be able to perform under the contract.

The debtor has the right to assign a lease to a third party willing to pay more than contracted rent, without permission from the lessor, and garner any revenues generated. Sometimes firms sell property designation rights—which involves transferring the debtor's right to decide which contracts to assume, to whom they will be assigned, and under what terms—to a third party, for a price. The purchaser, often property management companies, are willing to pay cash to the debtor and assume the responsibility to market the leases. The leases can, therefore, become a valuable asset, especially those with below‐market rates. However, property owners may file objections on reassignment of leases to third parties, based on business or moral grounds.

Generally, a debtor will assume or assign leases with good terms and renegotiate or reject those with unfavorable terms. In fact, the threat of rejecting bad leases often gives the debtor considerable negotiating leverage over lessors to modify terms. Rejection and assignment of leases have saved many large retail and airline firms in bankruptcy millions of dollars in operating expenses.11 Lemmon, Ma, and Tashjian (2009) show that rejecting lease contracts in bankruptcy constitutes a large portion of asset restructurings. With the accelerated timetable of a maximum 210 days to decide, the debtor is not given sufficient time to analyze performance and decide whether to assume or reject leases in bankruptcy and therefore often makes decisions even before filing bankruptcy.

The debtor firm is also equipped with rights to assume and reject supply contracts via Section 365. The debtor can use these rights as a threat to renegotiate terms of their prepetition contracts, potentially saving millions of dollars for the debtor but squeezing margin for their suppliers. Academic studies (e.g., Hertzel, Li, Officer, and Rodgers 2008; Kolay, Lemmon, and Tashjian 2016) find that customer bankruptcy is generally bad news for suppliers, which experience negative equity returns when customers file for bankruptcy, particularly when the costs of replacing those customers is high.

Developing and Confirming a Plan of Reorganization

Unless the case is dismissed or converted to Chapter 7, for the debtor to be able to emerge from bankruptcy, the court must confirm a plan of reorganization. The plan specifies who the claimants are, what those claimants will receive in the restructuring (and therefore what the new capital structure will look like), and other aspects regarding the disposition of assets. Therefore, it is important to review how the plan is developed, what the plan must achieve in order to be approved, and the process for parties to agree to a plan. The plan must be accompanied by a “disclosure statement” that contains sufficient information about the debtor to enable claimants to make an informed judgment whether to accept the plan.

Exclusivity Period The 1978 Code gives the debtor an exclusivity period of 120 days after the petition to file a plan. Other parties, such as the trustee, a creditors' committee, an equity security holders' committee, a creditor, an equity security holder, or any indenture trustee, may file a plan only if a trustee has been appointed, if the debtor has not filed a plan within 120 days of filing, or if the debtor's plan is not accepted within 180 days of filing. However, the frequency with which courts granted extensions to this period prompted the writers of the 2005 Act to limit exclusivity periods to a maximum of 18 months (plus two months to permit solicitation and plan confirmation).

One interesting statistical trend of the past four decades is the time spent in bankruptcy from filing to emergence. Prior to the passage of the BAPCPA in late 2005, the median time in default was about 24 months. Since 2006, the median time has decreased by more than half to 11 months, due in part to limits on extending exclusivity and to a large increase in prepackaged Chapter 11 filings (see Altman and Benhenni, 2017; Altman and Kuehne, 2017).

Absolute Priority and Classifying Claims To receive any distribution under a reorganization or liquidation plan, a creditor must file a proof of claim and an equity holder must file a proof of interest. Under a plan, claims are grouped into classes of “substantially similar” claims and ranked according to their seniority. These classes typically include the following, though more complex plans can specify a number of separate classes within these broader groupings.

- Secured creditor claims, that is, those that have specific assets as collateral. Secured claims have priority over all other claims to the extent that the liquidation value of the collateral is greater than the amount of the claim. If the collateral value is sufficient, postpetition interest can accrue as part of the secured claim. The debtor may be able to utilize the collateral for its benefit during reorganization to the extent the secured claims are “adequately protected” (see above). If the collateral value is insufficient to cover the full amount of the secured claim, the balance is considered as an unsecured claim.

- Priority administrative expense claims, which include trustee fees, legal fees, and other service fees. Although ranked lower than secured claims, the court requires these fees be paid in order for a plan to be confirmed. Other administrative claims include (with exceptions as specified in Section 503) necessary costs accrued in the ordinary course of the debtor's business or financial affairs after the commencement of the case; for example, for payments to suppliers as described above. In contrast, in a Chapter 7 liquidation, the only administrative claims allowed are trustee, legal, and professional fees, which are paid from the liquidation proceeds before secured claims.

- Other priority claims, including prepetition employee wages, unpaid contributions to employee benefit plans, customer claims (money in connection with the future use of goods or services from the debtor), claims of governmental units such as taxes and penalties, and employee injury claims. Prepetition employee wages are allowed with a limited dollar amount from up to 180 days before the filing (or the cessation of the debtor's business, whichever occurs first).

- Unsecured claims, which include unsecured bonds, trade claims, legal claims, insurance claims, and so on. Senior debt has priority over all debt that is specified as subordinated to that debt, but has equal priority with all other unsecured debt. The terms of most loan agreements spell out these priorities. In addition, the organizational structure of the company matters to the priority ranking of the debt claims (see Chapter 2 herein).

- Prepetition equity holder claims – preferred and common stockholders, in that order.

The proposed plan lays out the distributions to be made to each class of claimants. Distributions are made after the plan has been confirmed in cash or in the form of claims on the reorganized firm. The lowest priority class or classes that are entitled to receive any distribution typically receive shares of stock in the reorganized firm.

Most reorganization plans are guided by the “absolute priority rule” or “APR” (Section 507), which means that higher priority claims must be paid in full before a less senior claim can receive anything. In practice, plans are a negotiated agreement involving each class that is entitled to vote on the plan. Thus, a plan can violate absolute priority, such that a more junior claim receives some payment while more senior claims are not paid in full. This arrangement is often expedient and permits compromise with creditors who would otherwise vote against a plan.

Deviations of APR were common in the 1980s and 1990s but have become less frequent since the 2000s (see Chapter 7 for empirical evidence). APR deviations are guided by the “best interest test” (see below) whereby no impaired creditor class receives less value than would have been received in a liquidation. In essence, absolute priority serves more as a guideline for a Chapter 11 plan than as a requirement.

Reorganization Valuation The centerpiece of a reorganization plan is a valuation of the debtor as a continuing entity. Valuation involves a forecast of expected postbankruptcy “free cash flows” based on the underlying business plan for the restructured firm. The specific valuation methodologies applied to these forecasts are discussed in Chapter 5. The total enterprise value can incorporate other assets such as excess working capital, tax loss carry‐forwards, and other considerations. If the estimated value of the going concern value is less than the total amount of allowed claims, the firm is insolvent in a bankruptcy sense.

Waterfall Distribution The reorganization value is distributed to classes following absolute priority. Strictly following absolute priority, once the value available for distribution has been exhausted, claims falling below that amount receive no distributions. For an insolvent debtor, prepetition equity holders and perhaps additional lower priority claims receive no distribution under the plan.

Figure 3.2 provides a simple illustration of the waterfall analysis based on a hypothetical situation. Suppose the company has three classes of debt, senior secured loans, senior unsecured notes, and subordinated notes, and equity interests. The revolver and term loans are pari passu (on equal footing). The distribution of value has high‐ and low‐case scenarios. The table shows that in a low‐case scenario, where the firm's value is worth $800, the value is split between revolver and term loans, with each recovering 80% of its claim amount, leaving no recovery to the junior claimants. In the high‐case scenario, the firm's value is large enough to cover the value of claims up to subordinated notes, which receive a recovery of 50%. In both scenarios, equity holders receive zero recovery. The distribution to different classes of claims can be in the form of cash, new debt, and new equity of the reorganized entity (see Chapter 5 herein for an example of Cumulus Media for how waterfall distributions work in practice).

| Distribution of Value | Recovery Rates | |||||||

| Claim Amount | Low Case | High Case | Low Case | High Case | ||||

| Distributable value | — | $800 | $1,400 | $800 | $1,400 | |||

| Secured debt | ||||||||

| Revolver | $200 | $160 | $200 | 80% | 100% | |||

| Term loan | $800 | $640 | $800 | 80% | 100% | |||

| Available to lower claims | — | $0 | $400 | — | — | |||

| Unsecured debt | ||||||||

| Senior notes | $200 | $0 | $200 | 0% | 100% | |||

| Available to lower claims | — | $0 | $200 | — | — | |||

| Subordinated notes | $400 | $0 | $200 | 0% | 50% | |||

| Available to lower claims | — | $0 | $0 | — | — | |||

| Equity interests | — | $0 | $0 | 0% | 0% | |||

FIGURE 3.2 A Simple Illustration of the Waterfall Analysis

Voting and Confirmation of the Plan Once a Chapter 11 plan and an accompanying disclosure statement have been approved by the court and distributed, each claim holder within a class entitled to vote can cast its ballot to accept or reject the plan. A plan may specify that the rights of certain claims or interests are unaltered by the plan, for example, when secured debt is reinstated and will be paid as originally scheduled. Such classes are referred to as “unimpaired,” are deemed to accept the plan, and so do not vote on the plan. Certain classes may receive no distribution under the plan, for example, for prepetition equity holders of an insolvent firm; such classes are deemed to reject the plan and again do not vote. The remaining voting classes are considered “impaired” and entitled to vote on the plan. A plan is deemed accepted by a class of creditors if at least two‐thirds in amount, and more than one‐half in number of voting claims within the class are cast in favor of the plan (Section 1126(c)). Shareholders (if entitled to vote) are deemed to have accepted the plan if at least two thirds in amount of the outstanding shares voted are cast for the plan (Section 1126(d)).

A hearing is held after the 60‐day voting period to determine whether the plan meets various requirements such that it can be confirmed by the court. The plan must be accepted by each class of claims or interests entitled to vote or not impaired, known as a consensual plan; or, a nonconsensual plan can be confirmed over the dissent of a class of creditors through a procedure known as “cramdown” (Section 1129(b)). At least one class of impaired claims or interests must accept the plan. For example, if the only class affected by the plan comprises a mortgagee, the plan cannot be confirmed without the mortgagee's consent.

The cramdown procedures enable the court to confirm a nonconsensual plan provided it does “not discriminate unfairly” and is “fair and equitable” to each class of claims or interests impaired. In general, a plan does not discriminate unfairly if it provides a treatment to the class that is substantially equivalent to the treatment provided to other classes of equal rank. The test for what is fair and equitable differs for secured creditors (either retaining their lien or receiving a new claim with a present value equity to their original claim), unsecured creditors (either receiving payment equal to the amount of their claims or the holders of more junior claims receive nothing under the plan), or equity interests (either retaining their interests or any more junior class of interests receives nothing).

In some instances, the obstacle in reaching a consensual plan is a disagreement over the firm valuation on which the plan is based. For example, a class of junior creditors may argue that the plan value is unrealistically low, and under a more appropriate valuation methodology a higher value would justify a large share of distributions to be made under the plan (see Chapter 5 herein). In such cases, the judge may order a full valuation trial to resolve the dispute, with a finding of a sufficiently higher value meaning that the plan could not be confirmed. More typically, however, the threat of such litigation is sufficient to reach a settlement leading to a consensual plan.

A confirmed plan must also satisfy several further requirements of the Bankruptcy Code, including the “best interest” and the “feasibility” tests. The best interest test requires that the creditors must receive or retain under the plan not less than the amount they would receive or retain if the debtor were liquidated under Chapter 7. Thus, the disclosure statement typically includes a liquidation analysis based on balance sheet accounts, which in the case of a reorganization generally show a significantly lower value that would be realized under a hypothetical fire sale of assets – satisfying the best interest test and further justifying the decision to reorganize. The feasibility test requires the debtor to show that confirmation is not likely to be followed by further need for financial reorganization or liquidation not contemplated within the plan. The cash flow analysis used to determine the debtor's reorganization value can be used to demonstrate that the firm is expected to generate sufficient cash flow to meet its post‐emergence obligations.

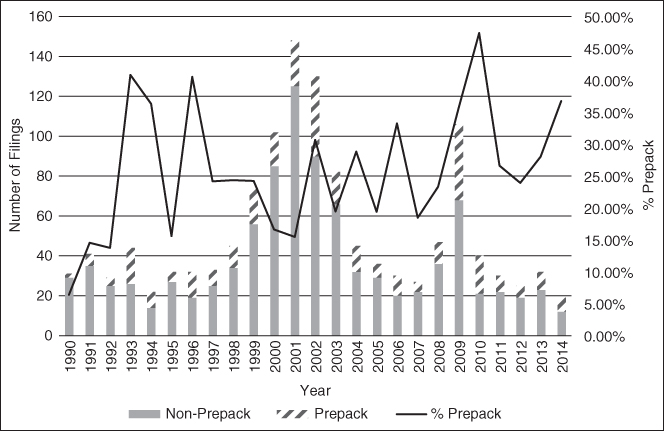

Prepackaged Chapter 11 An interesting innovation since the early 1990s is the use of a prepackaged bankruptcy, commonly known as a “prepack.” Prepacks combine the time‐ and cost‐saving attributes of an out‐of‐court restructuring with the voting requirements (only two thirds of a class need to approve a plan) and other advantages of an in‐court Chapter 11 proceeding. Under Section 11 USC.1126(b) of the Code, debtors are permitted to negotiate with creditors prior to filing and to accept prepetition votes with proper disclosure, that is, adequate disclosure and a reasonable time for analysis, discussion, and voting. In other words, the debtor reaches agreement on a plan with most of its creditors and solicits their votes in advance of actually filing for Chapter 11. This type of bankruptcy is frequently used by large U.S. firms, accounting for as much as one third of the total Chapter 11 filings by large U.S. firms from 1990 to 2014 (Figure 3.3). The BAPCPA increased the attractiveness of prepacks by loosening restrictions on information disclosure while creditors' votes are being solicited.

FIGURE 3.3 Prepackaged/Prenegotiated Chapter 11 Filings by U.S. Firms with $50 Million Assets

A prenegotiated arrangement is similar to a prepack except that the formal solicitation of the acceptance of the plan is done after the petition is filed. Before filing, the firm asks key creditors to sign a “lock‐up” agreement, typically referred to as a Restructuring Support Agreement (RSA), in which they agree to vote for the plan and other terms of the RSA once the firm is in Chapter 11.

A few dissenting creditors could effectively stall or stop a prepackaged arrangement, for example by filing an involuntary petition. However, the BAPCPA permits vote solicitation to continue after the filing of the petition as long as it began before and the process complies with applicable nonbankruptcy laws, usually the relevant securities laws. Thus, dissenting creditors now need to file their involuntary petition before solicitation begins, and the tactic of forcing a voluntary filing will no longer interfere with soliciting acceptance for a prepack.

There are many advantages of a prepackaged filing when compared to the regular “free fall” Chapter 11. First, a company negotiating a prepackaged Chapter 11 has a defined exit strategy from the bankruptcy before the legal process starts, which may dramatically increase its chances of emerging as a going concern. Second, while it still may take several months to emerge, the average time in bankruptcy of these cases is far less than the almost two‐year average of all Chapter 11s. Tashjian, Lease, and McConnell (1996) find evidence that the cost of a prepackaged Chapter 11 falls in between the costs of a conventional Chapter 11 and an out‐of‐court restructuring.

It is worth noting that an accelerated bankruptcy is not in every distressed company's best interests. For companies that suffer from more serious business problems that can be more effectively addressed through an extended stay in Chapter 11 or that have more complex debt structures that hinder soliciting votes prepetition, a prepackaged or prenegotiated Chapter 11 will be less attractive or feasible (Gilson, 2012). On the other hand, if a firm's value might significantly deteriorate upon a Chapter 11 filing, as was argued for General Motors in 2009, a prepack can enable the firm to quickly restructure and minimize its loss of value from losing customers, suppliers, and other costs.

Plan Execution Confirmation is followed by a plan “effective” date. Distributions of cash and new claims, as specified in the plan, are made to allowed claims, and prepetition claims are either cancelled or reinstated. For example, when prepetition stockholders receive no distribution under the plan, the original shares are cancelled, and newly created shares are distributed. Securities issued under a plan are exempt from registration with the SEC. Note that if a plan is approved, it is binding on all members of a given class. The plan may satisfy or modify any lien, waive any default, and merge or consolidate the debtor with one or more entities.

A plan must provide adequate means to put in place its postbankruptcy capital structure. Typically, the firm will have arranged postpetition credit known as “exit‐financing,” for example, a new or reinstated revolver and term loan, as well as other debt financing to fund operations post‐emergence. During the 2008–2009 economic crisis, lack of availability of such financing made it difficult for some firms to reorganize.

An additional ingredient to some successful bankruptcy restructurings lies in the debtor's ability to raise new equity capital for the emerging firm. An equity infusion by existing or new investors can signal to the market that real economic value still exists in the firm's assets. Various courts have invoked a so‐called “new value exception” or “new value doctrine” to the absolute priority rule, which permits existing equity holders to hold equity interest in a reorganized debtor based on additional contributions to the business even where more senior, dissenting classes of creditors are impaired. Specifically, using new value exception, the plan proponent typically includes a provision to allow equity holders to contribute to the reorganized debtor's new estate value in order to retain existing interest or to receive new equity even though one or more senior classes of claimants are not to receive full payment under the plan. Another increasingly common form of equity contribution at emergence occurs via a rights offering, whereby certain prepetition claimants are given rights to purchase additional stock in the emerging company. Rights offerings are sometimes “backstopped” by a group of creditors particularly interested in owning a majority of the postbankruptcy equity, giving them the ability to exercise rights given to other claimants less interested in contributing cash to own additional post‐emergence shares.

OTHER KEY ASPECTS OF CHAPTER 11

Key Employee Retention and Incentive Plans

Key Employee Retention Plans (KERPs) and Key Employee Incentive Plans (KEIPs) are compensation schemes designed to award senior managers who are deemed critical to the restructuring and continuation of the business. A large fraction of US public firms adopted these plans in bankruptcy to retain key managers. However, there are ongoing debates on whether these plans are schemes for rewarding failed management teams at the expense of other stakeholders or optimal contracts awarded when the bankrupt firm needs to retain human capital the most. A detailed discussion of these plans is provided in Chapter 6 herein.

Asset Sales

Asset sales outside of a firm's ordinary course of business are conducted using Section 363 of the Code, which establishes a formal process for companies to sell assets on an expedited basis. Section 363 sales have several advantages compared to selling assets outside of bankruptcy or through a Chapter 11 plan. First, Section 363 sales are subject to the debtor's discretion and judge's approval, but not to a creditors' vote. In contrast, asset sales through a plan must be voted on by creditors. Second, assets are sold “free and clear of liens and encumbrances” meaning that the lender will have a lien on the proceeds of the sale only after the sale, thereby exempting the buyer from the old lender's security interest in the assets transferred. Third, because the final sale is approved by and implemented through a bankruptcy court order, the validity of the transaction is generally immune to later legal challenges.

To sell assets under Section 363, a debtor must file a sale motion describing the bidding and selling procedures. Typically, a stalking horse – an initial interested buyer with whom the debtor has entered an asset purchase agreement – is identified. Key stakeholders of the bankrupt firm, including secured creditors, unsecured creditors, and United States Trustees, among others, can file formal objections to the proposed sale. If the court approves the bidding procedures, a date is set for submitting qualified bids and for an in‐court auction. A final sale hearing is held and the judge approves the sale to the winning bidder from the auction, or an auction is not held if there are no further bidders. This process can take just a few weeks to complete.

Note that judges are permitted to consider nonprice factors in choosing the winner of an auction. Judges may defer to the debtor's business judgment and the fairness of the bidding procedures to determine whether the winning sale is highest or best. For example, in Polaroid's 2009 Section 363 auction, the judge awarded the sale to the second‐highest bidder, which had a better track record of buying and managing bankrupt company brands (Gilson, Hotchkiss, and Osborn, 2016). Break‐up fees are awarded to stalking horse bidders if they are not the winning bidders.

Assets sold through Section 363 range from a piece of equipment (Maksimovic and Phillips, 1998) or real estate property (Bernstein, Colonnelli, and Iverson, 2018) to substantially all of the operating assets of the company (Gilson et al., 2016). Intellectual property such as patents have become a frequently sold asset through Section 363 (Ma, Tong, and Wang, 2017). The buyers can be any interested party, including industry competitors, financial institutions, and even the debtor's creditors. In fact, Section 363(k) allows secured creditors, including a DIP lender, to “credit bid” for assets using their allowed secured claims instead of cash to bid up to the value of their claim. A DIP credit agreement may contain provisions requiring the lender's approval of the bidding procedures, or of the Section 363 sale itself.

Preferences and Fraudulent Transfers

The 1978 Code and the subsequent amendments made by the BAPCPA grant the trustee or debtor the power to avoid (i.e., reserve or clawback) preferential transfers (Section 547) and fraudulent transfers (Section 548). What is the difference between these two types of transfers? We here illustrate it using a simple example. Suppose a firm has outstanding debt to two different creditors. In the first scenario, the firm pays off one creditor and then files for bankruptcy a few weeks later. In an alternative scenario, the firm decides not to pay off either creditors and instead gives the cash to a friendly equity owner. The transaction made in scenario 1 is known as a preferential transfer, which gives preferential treatment to one creditor over another. The transaction made in scenario 2 is known as a fraudulent transfer that harms both creditors. In essence, preferences refer to the redistribution of the value of the debtor between creditors. In contrast, the fraudulent transfers provision allows for bringing cash or other value back into the bankruptcy estate, which should benefit all creditors. However, these transfers can be avoided only through litigation, which is always costly.

According to the Code, preferential transfers can be avoided if such transfer was made while the debtor was insolvent and within 90 days of the bankruptcy petition date, or between 90 days and one year before the petition date if such creditor at the time of the transfer was an insider. Certain defenses are available against preference avoidance actions. For example, the transfer may not be voided if the payment was a debt incurred and paid in the ordinary course of business of both parties, or the payment was made according to ordinary business terms. As such, payments will be allowed if they meet industry standards and are in the ordinary course of that business. These provisions, as part of the amendments of BAPCPA, make it difficult for the debtor to recover preference claims against a creditor.

Transfers of assets away from the debtor can be voided if the company performed the transfer with the intent to hinder, delay, or defraud creditors, or if the company received less than a reasonably equivalent value and the company was insolvent on the date when the transfer occurred. Therefore, to determine whether a constructively fraudulent transfer occurred requires valuation analysis to determine whether the company was insolvent at the time of transfer and whether the company received reasonable equivalent value in the transaction. The statutory limitation for the fraudulent transfer look‐back period is two years. However, fraudulent claims are recognized under state law. There are subtle differences in state law on the look‐back period, which ranges between three and six years.

The typical fraudulent transfers involve the following transactions: asset sales before Chapter 11 filing, asset transfers within corporate entities, loan guarantee provisions between corporate entities within the parent company, and leveraged buyouts (LBOs). In fact, in nearly every LBO there is some prospect of fraudulent transfer litigation. Plaintiffs can argue that certain knowledgeable creditors, like banks, unfairly benefited from these leveraged transactions, which eventually fail and result in losses to junior creditors. The centerpiece of the claim is that banks and other “insiders” knew or should have known that the restructuring would likely result in a failure to meet the debtors' liabilities, but went along with the deal to derive its “own benefit” from upfront fees, priority payments, and so on.

Claims Trading

One of the most important advances in the bankruptcy process since the enactment of the 1978 Code is the fast development of markets for trading claims in bankruptcy. Before the act went into effect, the only claims that were routinely traded in the financial marketplace were publicly registered debt securities. The market expanded dramatically in the 1980s and continued to grow rapidly in the 1990s and 2000s. There is tremendous turnover in the ownership of debt claims once firms become distressed because of the entry of specialized distressed debt investors. Given these trends, some say claims trading has transformed U.S. corporate bankruptcy to a market‐driven process.

The bankruptcy rules for the trading of claims (Rule 3001(e)) were amended in August 1991, making it easier to purchase claims. These rules apply to all claims but have a particular focus on claims that are not publicly traded. Judges will not get involved in ruling on trading of claims unless an objection is lodged. The amount paid for a claim and any other terms of the transfer does not have to be disclosed.

In general, the claims trading markets are composed of a few overlapping segments that vary in liquidity, rules, and regulation. They are public debt, bank loans, trade claims, and other claims such as tort claims, insurance claims, and derivative claims. Bonds are traded over‐the‐counter and are regarded the most liquid type. There is little counterparty risk involved because of the use of large financial institutions as broker‐dealers. Identities of counterparties are typically not known, making comprehensive due diligence impossible.

The second type is bank loans, which are typically syndicated and traded in slices. Active trading of private claims, such as bank loans of bankrupt firms, was not evident in the 1980s but took off in the 1990s, particularly with the establishment of the Loan Syndication and Trade Association (see Chapter 2 herein). Distressed loans emerged as a new asset class. This market segment attracted enough attention that several large broker‐dealers were making regular markets. Specialized distressed debt investors that intend to gain control of the bankruptcy reorganization process frequently purchase loan claims even before a bankruptcy filing. Holding prepetition loan claims grants these investors an advantageous position in supplying DIP financing.

Purchasers of trade debt have more uncertainty and challenges than the purchasers of loans and bonds. Counterparty risks and due diligence requirements are much higher for trading these claims. For example, verifying the validity of a claim may prove to be challenging, and, as a result, the purchaser has much uncertainty about how much of the claim will be allowed. This market is occupied by a group of specialized investors (e.g., Argo Partners, ASM Capital), who typically purchase claims after the schedules of claimholders or proofs of claims are filed. Trading other bilateral claims, such as tort claims and derivatives claims, possesses similar characteristics and risks to trading trade debt and are also governed by Rule 3001(c). However, the market for these claims is much smaller.

Because members of the UCC and other official committees typically have access to material nonpublic information about the debtor, members of the committee are prohibited from trading securities of the company without disclosing this fact to the counterparty. The SEC has filed several complaints against parties that traded debt claims while serving on creditors' committees. Restricted debt holders are careful to ensure the counterparty is aware that they have material nonpublic information when they trade by executing a “big‐boy” letter with the counterparty, though such a letter does not fully eliminate the litigation risk. Some debt holders may choose to forgo access to material nonpublic information in favor of having freedom to trade by not joining the UCC.

Hotchkiss and Mooradian (1997) are among the earlier academic studies showing the impact of claims trading on the dynamics of the bankruptcy case. More recently, Ivashina, Iverson, and Smith (2016) examine transfers of claims during bankruptcy using data obtained from four leading providers of claims administrative services for Chapter 11 cases. This data includes information on claims transfers from proofs of ownership transfer required to be filed (under Rule 2001(e)) for all claims that are not syndicated bank loans or public debt securities. They document that active investors, including hedge funds, are the largest net buyers of claims in bankruptcy. Trading leads to a higher concentration of ownership, particularly among claims whose holders are eligible to vote on the bankruptcy plan and among claims that represent the “fulcrum” security in the capital structure.

Accounting and Tax Issues

This section introduces two accounting and tax issues that are particularly important to Chapter 11 companies. These issues are complex and require the expertise of tax accountants. Our objective is to provide a simple introduction.

Net Operating Losses (NOLs) are negative taxable income that can be used to offset taxable income in profitable years (Section 172 of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC)) and thus are an extremely important element in any reorganization, especially if the value of the new firm is relevant, as it almost always is. In contrast, net operating loss carryforward questions are irrelevant in a straight liquidation. Theoretically, as the value of a firm is the discounted expected value of its future after‐tax earnings plus the present value of tax loss carry‐forwards, preserving NOLs in Chapter 11 reorganization is an important concern for a company.12

NOLs can be carried back up to two years and forward up to 20 years for most taxpayers. Since a bankrupt firm most likely incurs losses before filing, NOLs are typically applied to future tax years. NOLs are used on a first‐in and first‐out basis (i.e. oldest NOLs are applied first). The Tax Reform Act of 1986 made sweeping changes in the rules governing the use and availability of NOL carryforwards, following certain changes in the stock ownership of a loss corporation. Specifically, if the percentage of stock owned by one or more 5% shareholders increases by more than 50% within a three‐year period, annual limitation on use of NOLs (equal to the product of market value of equity prior to ownership change multiplied by the long‐term exempt rate set up by the IRS) is applied. That is, the Chapter 11 firm must track the stock ownership of (only) 5% percent shareholders. All shareholders with less than 5% ownership are considered a single 5% shareholder.

Generally, preserving NOLs is easier in a formal bankruptcy than in a private workout (see Chapter 4 herein) as the bankruptcy entity can benefit from two statutory carveouts (the insolvency and bankruptcy exceptions) from Section 382 limitations. The first carveout (Section382(l)(5)) allows the debtor that undergoes a change of ownership in bankruptcy to emerge without Section 382 limitations if:

- Shareholders and creditors of the company end up owning at least 50% of the reorganized debtor's (voting power and value of) stock of the newly reorganized company in exchange for discharging their interest in and claims against the debtor, and

- 50% of equity was given to “old and cold” creditors (defined as those holding claims for at least 18 months as of the filing date), ordinary business creditors, and equity holders.