CHAPTER 11

Applications of Distress Prediction Models: By External Analysts

In Chapter 10, we discussed the evolution of the Z‐Score model, and other distress prediction techniques, and included a list of applications of the models. Figure 11.1 shows that list again. In the next three chapters, we revisit this applications subject, elaborating on many of suggested, or already experienced, applications, including several that were not discussed earlier. This first chapter concentrates on those applications performed by analysts who are external to the distressed debtor (left‐hand column of Figure 11.1) in order to improve their position or to exploit profitable opportunities presented by distressed firms and their securities. Chapter 12 explores in greater depth, via a case study, the unique application related to managerial efforts for formulating and implementing a turnaround strategy. And in Chapter 13, we apply our updated distress prediction model, called Z‐Metrics™, in a “bottom‐up” analysis of the default assessment of sovereign debt.

| External (to the Firm) Analytics | Internal (to the Firm) and Research Analytics |

|

|

FIGURE 11.1 Z‐Score's Financial Distress Prediction Applications

Source: E. Altman, NYU Salomon Center.

Lenders and Loan Pricing

Perhaps the most obvious application of distress prediction/credit scoring models is in the lending function. Banks and other credit institutions are continuously involved in the assessment of credit risk of corporate, consumer, sovereign, and structured counterparties. The importance of credit‐scoring models for specifying the probability of default (PD) has been heightened and motivated immensely by the requirements of Basel II and Basel III and the necessity for banks to develop and implement internal rating based (IRB) models. We hope that the decision of U.S. regulators (e.g., the Federal Reserve Board) not to require most banks in the United States to conform to Basel II will not serve to demotivate banks from developing these models – but we fear that it will, in many cases. On the other hand, banks in many other parts of the world, particularly Europe, have been encouraged, with great success, to modernize their credit risk systems by the requirements under Basel II.

One of the important dimensions of the lending function is to specify the “price” of credit (i.e., the appropriate interest rate). The use of credit scoring models permits the specification of the PD in the determination of LGD in the pricing algorithm. For example, in Figure 11.2, we use a corporate loan rated as BBB by an internal scoring model to begin the LGD process (see our discussion in the prior Z‐Score chapter) and pricing decision. The PD and recovery rate assumptions are given (0.3% per year and 70.0%, respectively) and the expected loss of 0.09% per year is quantified.

|

Given: Five‐Year Senior Unsecured Loan Risk Rating = BBB Expected Default Rate = 0.3% per year (30 b.p.) Expected Recovery Rate = 70% Unexpected Loss (O') 50 b.p. (0.5%) per year BIS Capital Allocation = 8% Cost of Equity Capital = 15% Overhead + Operations Risk Charge = 40 b.p. (0.4%) per year Cost of Funds = 6% Loan Price(1) = 6.0% + (0.3% × [1 – .7]) + (6[0.5%] × 15%) + 0.4% = 6.94% Or Loan Price(2) = 6.0% + (0.3% × [1 – .7]) + (8.0% × 15%) + 0.4% = 7.69% |

(1) Internal Model for Capital Allocation

(2) BIS Capital Allocation Method

FIGURE 11.2 Risk‐Based Pricing: An Example

The next step is to add the required amount to the loan price based on the unexpected loss. We can do this in two ways – based on either economic capital criteria or regulatory capital requirements. Economic capital requires an additional cost in making the loan for unanticipated losses based on the degree of conservatism of the lending institution (i.e., its own risk preference). For example, the bank with a high‐risk avoidance preference – that is, one that wants to attain a high credit rating for itself – will require a very high confidence interval for not exceeding a particular loss. In our example, we utilize a six‐standard‐deviation requirement, sometimes referred to as the required average return on capital (RAROC) approach of an AA bank. The estimated standard deviation of 50 basis points per year (given) is then multiplied by 6 to arrive at the required amount of capital (300bp) for this lending capital requirement, which is then multiplied by the bank's net opportunity cost (15%) for not investing and this product is added to the expected loss and other costs to arrive at the required economic capital (6.94%). We suggest using the net cost of equity (cost of equity minus the risk‐free rate) for the calculation of the opportunity cost (15%). We also factor in other operating costs by adding an estimated 40 basis points per year to cover such noncredit items as overhead and operating risk charges, (the latter is required under Basel III).

So, for the economic capital computation, in our example, the result is a required price, or interest rate, of 6.94%. This compares to the old Basel I regulatory capital requirement calculation, based on a flat 8% instead of the 3% (6 × 0.5%) economic capital, and the regulatory capital interest rate is higher by 0.75%, at 7.69%. One can now see why most banks will prefer the Basel II framework. Again, accurate scoring models are critical to the modern pricing structure. Even if a bank, or nonregulated institution, does not use or cannot use economic capital pricing criteria due to competitive conditions, the economic pricing analytics based on risk rating criteria will be helpful to ascertain how far from the actual price charged is the one based on economic pricing. Note that our example does not incorporate correlation and concentration issues in the pricing function. Such factors add to the complexity of credit decisions and should be considered by the portfolio management group of the financial institution.

Bond Investors

Beyond the financial institution lender of commercial loans, other financial institutions (e.g., shadow banks) and individuals can profit from a well‐tested and appropriate credit scoring system in their fixed income strategies. Perhaps the most obvious application is to determine whether to invest in a debt instrument selling at, or near, par value. The determination of PDs is important for investment‐grade as well as junk bonds. Indeed, about 22% of all defaulting issues from 1971–2017 and 19% from 2007–2017 were originally rated as investment grade by the professional rating agencies!1 So the professional manager should include default risk analysis, as well as yield and concentration considerations, in his or her deliberations of investment grade decisions. If the investment‐grade company has a financial profile of a lower‐rated entity, the required rate of return should reflect that. The calculated financial requirement can be determined by both counterparties' bond rating equivalent (BRE), discussed earlier in Chapter 10.

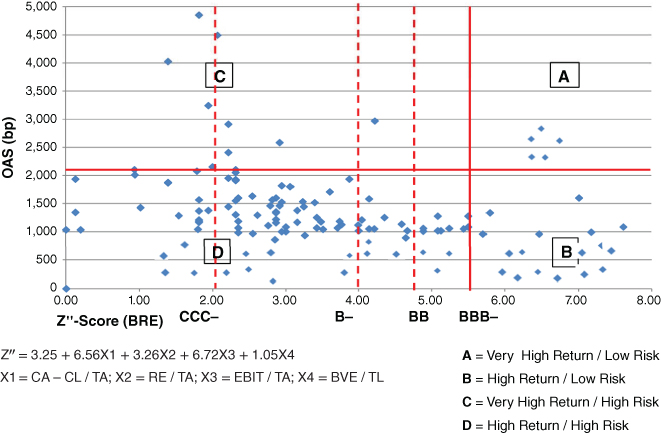

For bonds selling in a distressed condition (i.e., 1,000 basis points or more above Treasuries), the key question to ask is whether the company will continue to migrate to an even lower credit quality (or, in fact, default) or whether the PD is sufficiently low to assess that its price will return to par (assuming it had already migrated down, perhaps even to a “fallen angel” downgraded condition). The upside potential, from distressed to par, provides equity‐type returns that are far greater than returns expected from a typical debt portfolio. Indeed, the average return on a portfolio of non‐investment‐grade bonds in 2009 was about 60%, as a large proportion of those corporate bonds that were distressed as of the end of 2008 returned to par or above‐par value in about one year. Probably the onset of the benign (forgiving) credit cycle had a lot to do with this incredible run, but one's conviction to select securities that are selling at “deep junk” or distressed‐yield levels can be heightened when the credit model ascribes a higher BRE to the security than the one derived from the market. This “Quality‐Junk” investment strategy can be shown in Figure 11.3, whereby higher‐yield bonds from companies in quadrants A and B, with high BREs, are particularly attractive candidates.

FIGURE 11.3 Return/Risk Tradeoffs – Distressed and High‐Yield Bonds, as of December 31, 2012

The Type II error – that of selling, or not buying, the distressed security when in fact its price returns to par – is always possible but the cost involved is not an important one for most traditional debt investors. Where it does matter, however, is in the case of a distressed debt or highly leveraged hedge fund investor. We strongly believe that a disciplined investor will find credit scoring and default risk models of considerable benefit in the investment process. And, combining rigorous credit risk default probability models with the selection of low‐volatility distressed securities (see Altman, Gonzalez‐Heres, Chen, and Shin 2014) for a discussion of this yield‐spread criteria) will, in our opinion, provide a potentially very attractive fixed‐income investment strategy. That is, to select distressed or attractively high‐yield spread companies with acceptable default probability attributes.

Common Stock Investing

We were surprised to find that in our discussions with data vendors, like S&P Global's Capital IQ (part of S&P Global's Global Market Intelligence) and Bloomberg, LP, that there were more “hits” from equity‐market investors/analysts on the Altman Z‐Score “page” than from Bond and Fixed Income investors/analysts. So it seems that equity investors are interested in preservation of capital as well as in achieving “alpha” returns or matching some index of performance. One way of preserving capital is to avoid investing in securities of companies that eventually go bankrupt. In most cases, defaulting companies' equity securities are completely or mostly wiped out.

In addition to avoiding financial distress of corporate issuers, investors take comfort with strategies that provide a “strong balance sheet,” whether for value investing or in the selection of companies that have desirable growth prospects and low probabilities of default. Such a strategy might fit into a long‐short equity approach. And, we have found several investment management “packagers” who offer investors this long‐short strategy through equity “baskets,” whereby the selection of “long” purchases are firms' equities with high Z‐Scores and the “shorts” are selected from those firms with low Z‐Scores. A variation on the long‐short strategy approach is to just concentrate on going long or going short, but not both, based on the Z‐Score criterion.

Examples of equity selection “baskets” are Goldman Sachs' “Strategy Baskets,” which combined the preservation of capital goal with dividend yields and growth prospects.2 The main idea was that companies with strong balance sheets, based on Z‐Scores above a certain high level, for example, 4.0, will outperform firms with weak balance sheets, for example, below 2.0, especially in tight or stressed credit conditions. So, a long‐short strategy based on these criteria will provide excess returns, especially when combined with high dividend growth prospects, if both are available. The Goldman Long GSTHWBAL/Short SPX strategy returned 12.9% for the period February 2008 to December 2008 compared to an S&P 500 performance of –31.2%, as reported in Kostin, Fox, Maasry, and Sneider (2008).

A more recent example of a common stock strategy based on Z‐Scores is the “STOXX Strong Balance Sheet Indices,” a strategy that selects the financially fittest companies on the European, Japanese, and U.S. Stock Exchanges.3 Launched in 2014, their indices are based on relatively high Z‐Scores' companies with a three‐year track record of scores of 3.5 and higher. Financial firms are excluded from the STOXX indices since the Z‐Score model did not include this sector. Indeed, it is the case that the original Z‐Score model's data contained only manufacturing firms (see discussion in Chapter 10) but it has been liberally applied across all industrial sectors in some cases.

Many of the vendors who reference the Z‐Score selection strategy discuss the approach with particular reference to distressed market conditions, see for example, Gutzeit and Yozzo (2011) and the aforementioned Goldman Sachs 2008 publication. We believe that the strategy has both equity and fixed‐income securities potential in any market condition, but in most cases will trail market indices' performance in strong bull markets. For one thing, the equity's past performance is encompassed in the Z‐Score via the X4 variable, market value of equity/total liabilities, and if the market has been strong, high Z‐Score firms may have peaked, or at least performed very well already. And many times, low Z‐Score firms, if they do not default, will outperform market indices in strong bull markets.

Other Investment Applications

A number of other investment banks and their brokerage operations have used the Z‐Score for a variety of analytical purposes to serve their clients' specific needs. For example, Morgan Stanley Dean Witter utilized a “Z‐Score” methodology to quantify retail REIT portfolios credit risk exposure based on their tenants' financial health, see Ostrowe & Calderon (2001). JPMorgan's Asia Pacific Equity Research, Smith & Dion (2008), applied Z‐Scores to information technology and health care sectors in Asia. And Merrill Lynch, Bernstein (1990), analyzed the financial health of S&P industrials during the entire decade of the 1980s and found that despite record levels of earnings and cash flows, the overall financial strength based on Z‐Scores had deteriorated. We addressed this seeming anomaly in Chapter 10 on the Z‐Score's 50‐year retrospective. The financial health of firms in 2016 were compared to 2007. Bernstein's concern was prescient as the market had serious problems with a big spike in defaults in late 1990 and early 1991. Stronger Z‐Score firms, however, made a remarkable comeback in their stock prices and also with high‐yield bond returns later in 1991.

Finally, Altman and Brenner (1981) utilized the Z‐Score to analyze a short‐sale strategy, whereby a portfolio of “shorts” was accumulated based on the first time a Company's Z‐Score dropped below a cutoff‐score. After adjusting for market returns, this short‐sale strategy demonstrated significant excess returns for at least 12 months after the Z‐Scores'deterioration was first indicated. Their analysis of a two‐factor model's findings indicated market inefficiency since the Z‐Score's variables and the weightings were public information at the time of our tests. A single‐factor market model's results, however, were mainly consistent with market efficiency tests in that the “new” Z‐Scores seemed to be digested in market prices instantaneously.

Security Analysts

One of the fundamental axioms in finance is that the debt analyst is, and should be, far more focused on the downside possible movement of securities than is the common equity analyst. So, an obvious tool for the debt analyst is a default prediction model. Both traditional ratio analysis, and one or more distressed prediction models, would seem to be a prudent addition to the security analyst process. As noted earlier, we were surprised to learn that equity analysts log‐into our Z‐Score model from data providers more than do debt analysts.

The analyst should also consider a type of pro‐forma distressed prediction treatment of the entity, especially where a heavily leveraged condition is likely to change through a series of steps (e.g., asset sales and debt paydowns). We have seen in Chapter 6 of this volume that highly risky capital structures can lead either to a healthy and high return scenario or to a default, depending on management's success in reducing debt and improving its rating equivalent status. The analyst earns his or her analytical status, in our opinion, by providing realistic expectations and forecasts about the likely success of management to achieve its target capital structure and cash flow goals. It is clear that highly leveraged companies, especially just after a major restructuring transaction, will be evaluated by most credit scoring techniques as a distressed situation. We advocate realistic pro‐forma scenario analytics, as well as current financial statement criteria, in the analysis process.

Regulators

Regulatory institutions, particularly bank examination department personnel, should be aware of and comfortable in evaluating credit risk systems used by constituent banks and other institutions. One of the challenges of the new Basel III framework is the role of the regulators, especially when evaluating the Pillar I capital requirement specifications of banks and in the Pillar II regulatory oversight function. Bank examiners need to be trained to evaluate the various credit scoring and probability of default/loss given default (PD/LGD) estimates used by banks. And, the various possible PD assessments on the same counterparty from numerous banks will serve as useful inputs in this process.

In addition, it is quite common for a nation's central bank, like the Banque de France, Banca Italia (now the ECB), or the U.S. Federal Reserve, to utilize its own credit scoring evaluation system to assess the credit quality of bank portfolios and to monitor the assessments made by their individual bank customers.

Auditors

In a very early application of the original Z‐Score model, we discussed (Altman and McGough 1974) the potential use of credit scoring models to assist the accounting firm audit function to assess the going‐concern qualification condition of customer accounts. We concluded, at that time, that while a reasonable proportion (about 40%) of bankrupt companies did receive a going‐concern qualification in the year just prior to filing, the Z‐Score approach predicted well over 80% of those entities as in the “distress‐zone”. Note that we now advocate using the bond rating equivalent (BRE) benchmark (see Chapter 10). Indeed, the accounting profession is very sensitive to its responsibility and has argued that it should not be liable for not qualifying a firm's financials just because it is in a highly risky, low rating‐equivalent condition.

Our experience with accounting going‐concern models involved building one for the now defunct Arthur Andersen (AA) franchise in their desire to establish criteria for going‐concern qualifications and to use in assessing whether to take‐on a new auditing client. We called that model “A‐Score,” which could be interpreted as with Altman, Arthur, or Andersen. Instead of using publicly available bankrupt firm data, like we did in building the Z‐Score model (1968), we utilized a combination of public firm bankruptcies and firms which defaulted from Arthur Andersen's historic database, as well as those that did not. Utilizing a logistical regression technique applied to this database, resulted in a highly accurate audit‐risk model, which was used for many years at the discretion of their local offices. Unfortunately, it was apparently not used in the infamous Enron case, which led to AA's downfall. Tests using our Z″‐Score model (Chapter 10) did show that Enron's BRE fell to single‐B where the agencies' rating was triple – B!

Despite the obvious potential conflict between a very rigorous professional auditor's posture with respect to going‐concern qualifications, and its desire to not cause problems for its customers and perhaps lose an account that it gives a going‐concern qualification, it would seem that auditors should be aware of and, indeed, use credit scoring models and other failure assessment techniques. These approaches can add objective feedback in their own assessments as well as in their discussions with the clients about their financial condition and plans going forward.

Bankruptcy Lawyers

One of the most prominent players in the bankruptcy and distressed firm arenas is the bankruptcy lawyer. The decision to take a firm into bankruptcy is a momentous one. While most bankruptcies are involuntary and decided on only as a last resort, whether to file and the timing of the filing are critical decisions. The longer a firm puts off the decision, the less likely, in most cases, it is that the reorganization will be successful. At the same time, if a successful turnaround can be managed out of court, then most likely the costs of financial distress will be lower than if the turnaround is achieved in bankruptcy (see Gilson, John, and Lang 1990). Usually, the bankruptcy lawyer is the prime adviser to the management of the firm as to whether to file and when to do so. Typically, the bankruptcy law firm will recommend to the ailing company potential consultants and paths of actions to take surrounding the bankruptcy or out‐of‐court restructuring decision. Such consultants, also discussed later in this chapter, might be turnaround and other restructuring specialists, bankers for bailout financing or, DIP financing, and so forth.

While there may be unmistakable signals of financial distress, lawyers can also productively use financial distress prediction models in their advisory work for clients. Whether the firm is mildly or deeply distressed is an important determinant. As we will explore in Chapter 12 of this book, management itself can use such models in its determination. Lawyers can benefit from the implications of a failure prediction model in such areas as the failing company doctrine (see below) and the once‐important issue of deepening insolvency. We now turn to these topics.

Legal Applications

Failure prediction models have had a number of direct applications in the legal arena over the years. These include such areas as (1) the failing company doctrine, (2) avoidance of pension obligations, and increasingly lately (3) the fiduciary responsibility of owners, managers, directors, and other corporate insiders like professional advisers. The last area relates to a concept and condition known as “deepening insolvency.”

Failing Company Doctrine

One defense against an antitrust violation by firms attempting to merge is the argument that an otherwise illegal merger should be permitted to occur if one or both of the merging entities would have failed anyway and its market share would likely have been absorbed by the other entity. We wrote in detail about this so‐called failing company doctrine in the first edition of this volume (Altman 1983) and in Altman and Goodman (1981, 2002), but space limitations in this edition preclude an exhaustive treatment.

Essentially, the failing company doctrine can be invoked if it can be shown that, while competitors that are trying to merge are unquestionably linked, either geographically or by market segment, at least one party was on the verge of bankruptcy and extinction. Examples might include two newspapers competing in a standard metropolitan area and one paper's demise would almost certainly result in its market share going to its closest competitor. This occurred in the antitrust dispute involving the Detroit News and the Detroit Free Press in the early 1980s. Using several of the Z‐Score models, one of the authors argued, in a deposition, that at least one of these entities would likely fail within a short period of time – both were in very bad shape. The court's solution was to permit the merger but to require the independence of the editorial staffs. Both entities remained in existence but the ownership with respect to revenues, costs, and profits was combined. Concerns about newspaper costs, labor relations, and other negative antitrust results were outweighed by the likely scenario of a single major newspaper for the city if the merger was not permitted.

Another example was the potential combination of two low‐priced beer companies in the Northeast of the United States in the early 1070s – Schaefer Beer and Schmidt's of Philadelphia. Both firms competed for the low‐end price customers of the beer market. We argued that Schaefer was a likely failing company and that while Schmidt's would surely absorb Schaefer's market share if the merger were permitted, it would happen anyway if it were not. The plaintiff, in this case Schaefer itself, which did not want to be taken over by Schmidt's, argued that it was not failing since it was not receiving a going‐concern qualification from its auditors (see earlier discussion) and its major creditor was not calling in its now long overdue loans, which had been nonperforming for almost two years. The judge agreed and essentially ruled that Schaefer was not failing because it had not failed – yet! Another beer, Stroh's of Milwaukee, which did not compete directly with either company, soon purchased Schaefer. A related issue to this case is whether the firm was in a so‐called zone of insolvency or not. We now turn to that issue.

Deepening Insolvency4

The theory of deepening insolvency, as discussed in Kurth (2004), originated with two federal cases in the early 1980s, In re Investors Funding Corporation and Schacht v. Brown. The simple argument was made that a corporation is not a biological entity for which it can be assumed that any act that extends its existence is beneficial to it. This argument is in stark contrast to the fundamental premise of the turnaround management industry and the principles underlying the Bankruptcy Code that the estate, involving creditors, shareholders, and employees, typically benefits if a distressed company can be reorganized successfully. A deepening insolvency argument, on the other hand, argues that the efforts to save an obviously dying entity can benefit some at the considerable expense of others. For example, the managers, advisers, and others trying to save the entity receive payments during the failed turnaround period, which results in lower recoveries after bankruptcy to others, such as creditors.

Deepening insolvency was increasingly being recognized, Kurth observes, as an independent course of action. This action could argue that a bankrupt company, or its representatives, may recover damages caused by professionals, such as advisers, accountants, investment bankers, and attorneys, who have either facilitated the company's mismanagement or misrepresented its financial condition in such a way as to conceal its further deterioration from an insolvent condition into deepened insolvency and bankruptcy. One recognized method of calculating damages is to measure the extent of the company's deepening insolvency.

Several questions emerged around this legal argument. How do you know that a firm is in the zone of insolvency, and how do you measure its deepening condition? Is it enough to simply say that as long as a firm has not gone bankrupt, defaulted on its debt obligations, or participated in a distressed restructuring (e.g., an equity‐for‐debt swap), it is not in the zone of insolvency? We do not believe so! A firm may be in an insolvent condition, but still not be defaulted.

The courts seemed to rely on a comparison between the fair market value of the firm's assets and the market value of its liabilities to determine whether it was insolvent. This criteria is essentially the basis for distressed prediction from the KMV model, first commercialized in the 1990s and sold to Moody's in 2002. See our references to KMV in Chapter 10 of this book and a more in‐depth discussion in Caouette, Altman, Narayanan, and Nimmo (2008). Incidentally, we would argue that the appropriate comparison benchmark for assets is not the market value of debt, but its book value, since the latter is what needs to be repaid to creditors. This is especially true if you measure asset value as the sum of the market value of debt plus equity – as most financial economists do.

In any event, we would also argue that a reasonable test of whether a firm is in the insolvency zone is to calculate its bond rating equivalent or failure score using several statistical measures. In particular, we advocate using the Z‐Score models and other techniques, such as the Moody's/KMV expected default frequency (EDF) approach. If both classify the firm as “in default” (e.g., a Z‐Score below zero and a KMV EDF of 20 or more), then its likely survival as a nonbankrupt or nondefaulted entity is seriously in doubt. Deteriorating scores will indicate a deepening condition, although we cannot argue that the deterioration is linear with respect to the change in score. Certainly, a firm with a Z‐Score of –2.2 is in worse condition than one with a score of –0.2. The use of the Z‐Score model in deepening insolvency cases and analyses was discussed by Appenzeller and Parker (2005).

A final note about the deepening insolvency legal claim. Most legal analysts point out that the original purpose of the argument was based on the bankruptcy that resulted after the insiders had perpetrated a type of Ponzi scheme or some other action that resulted in fraud or embezzlement, enriching its operators or advisers at the expense of unsuspecting creditors. And, it is argued that the guilty parties knew, or should have known, that the firm's chance of survival was unlikely. So, while we can help to specify whether or not the firm has a failing company profile, we cannot say for sure whether some turnaround strategy could not be successful.

Certainly, if the firm's true condition was known, but not revealed by those who could profit from continuing existence, then a legal cause for damages would seem to be valid. If, however, everything was revealed and best efforts were made to protect the remaining interests of owners, we would be reluctant to say that a firm's Z‐Score in the distressed zone, or a rating equivalent of D, means that it could not be saved. What we are arguing for is a clear and unambiguous metric of a firm's financial condition rather than relying only upon an expert's fair valuation of the firm's assets.

The next chapter of this book shows how a manager, with the assistance of the Z‐Score model, successfully used his business acumen and judgment to manage a financial turnaround. The essence of this case study is that all the indicators of financial distress were transparent and the strategy of simulating corrective actions with respect to a likely outcome on the firm's “health index” was not only appropriate, but also prudent. Even if these actions had failed, we do not believe that deepening insolvency would have been a legitimate argument in this case.

Bond Raters

While bond‐rating agencies do not use failure prediction models to reach their rating conclusions, we would argue that the results of one or more well‐tested and successful models could assist in the process. Obviously, Moody's saw great benefits in the output from the KMV EDF model since it paid a handsome sum to acquire KMV. Yet raters legitimately argue that such items as industry analysis, interviews with management, and a longer‐perspective “through the cycle” approach will determine their rating designations and that a model's point‐in‐time perspective should not be the basis for rating decisions. See Loeffler (2004) and Altman and Rijken (2004 and 2006) for discussions on rating stability, accuracy, and comparisons between through‐the‐cycle versus point‐in‐time models.

Risk Management and Strategy Advisory Consultants

Basel II has also been an important catalyst for the growth in risk‐management consulting firms. Entities such as Oliver‐Wyman (purchased by Mercer in 2002), Algorithmics (purchased by the Fitch Group in 2005 and sold to IBM in 2011), RiskMetrics (purchased by MSCI in 2010), Kamakura, CreditSights, and the risk‐management divisions of the other major rating agencies (e.g., KMV/Moody's, SPGlobal's Risk Solutions, Fitch Information Services) have prospered as the appetite for modern credit risk systems has grown. Most of these firms have developed credit risk tools that include scoring, structural, or hybrid combinations of these two credit‐scoring models. In addition, consulting and credit risk assessment entities, providing services related to valuation and portfolio management, might find that objective credit risk tools are helpful in their assessment of clients, for example, CreditRiskMonitor's FRISK system.

A related area of management consulting advice can be in mergers and acquisitions (M&A). A distressed firm could be encouraged to solicit a purchasing/strategic partner when its condition, assessed objectively, indicates going‐concern problems. This would especially be helpful if potential acquirers do not share the same internal assessment. Obviously, the price of the acquisition will be reduced if it is generally known that the firm is in a highly distressed condition. Accurate early‐warning models, however, can give a competitive advantage to users – whether they are the target or the acquiring firm.

Restructuring Advisers: Bankers, Turnaround Crisis Managers, and Accounting Firms

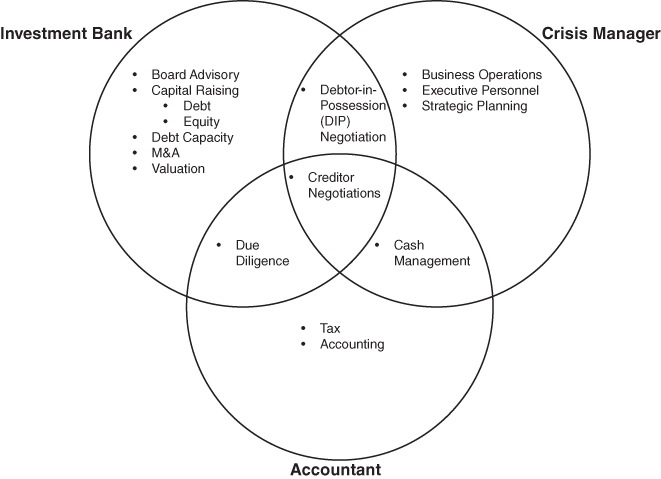

Four of the most prominent types of professionals that have emerged as important players in the distressed firm industry are (1) restructuring specialists, usually from boutique investment banks, (2) corporate turnaround or crisis managers from operations management consultants, (3) restructuring consultants from traditional accounting firms and (4) asset‐backed lenders. Figure 11.4 illustrates their relationships, overlaps and primary functions in the distressed firm industry.

FIGURE 11.4 Comparison of Financial Advisers' Roles

Source: Lazard Freres, 2005.

The competitive landscape in the turnaround consulting industry has evolved over the years. In the mid to late 1980s, the market was led by accounting firms and the efforts by the larger investment banks that had placed large amounts of debt in the highly leveraged restructuring boom (primarily ill‐fated leveraged buyouts and leveraged recapitalizations). For example, Drexel Burnham Lambert was a leading proponent of the out‐of‐court restructuring in the 1980s. In the early 1990s, with the huge increase in large Chapter 11 bankruptcies, some investment banks and new boutique divisions of smaller banks sprung up to fill the void caused by conflicts of interest from the larger investment bank under‐writing firms. More of these boutiques, sometimes as offshoots from the large accounting firms or investment banks, emerged in the 2001–2005 period, and the larger underwriters put resources into distressed refinancing, especially since M&A activity slackened in that period.

In addition to these advisers and consultants, a fairly active banking market emerged to provide funding at the bankrupt stage, such as debtor‐in‐possession (DIP) financing, and exit‐financing at the emergence stage. Many of the major commercial banks and also firms like GE Capital, Congress Finance, and CIT Finance became major players in this sector in the period from 2000–2007. After the financial crisis of 2008/2009, however, distressed firm lenders abandoned the market due to their own capital constraints, for example, GE and CIT.

Although definitely not mutually exclusive, the turnaround consultants play a role as advisers for the restructuring of the firms' assets (operations consultants known as crisis managers) and liabilities (restructuring bankers and accountants). The number of specialists in these fields swelled to over 20,000 globally in 2017, and many are members of the increasingly prominent Turnaround Management Association (TMA; website: www.turnaround.org). This professional, educational, and networking organization, based in Chicago, Illinois, had 55 chapters globally (33 in the United States and 22 abroad) with over 9,000 members in 2017.5

Turnaround managers can be hired to assist a firm to avoid filing for bankruptcy or, once in a legal bankrupt condition, to assist in the reorganization of the firm's assets and liabilities. Probably the three largest turnaround management consulting organizations are Alvarez and Marsal, AlixPartners, and FTI. These firms also typically provide financial and capital structure advice. While these three firms are relatively large, each with more than 1,000 full‐time employees, most turnaround management companies are quite small, with fewer than 10 full‐time consultants. There are also a number of relatively large turnaround management specialists in the 20‐ to 100‐employee range that can provide a full spectrum of advisory services. Often, these professional consultants have had prior experience as full‐time corporate managers in such areas as finance, marketing, operations, human resources, and information systems and have chosen to work with ailing companies to assist in their corporate renewal. In addition to their primary operation functions, these firms often assist in such areas as creditor negotiations, cash, and even strategic management. For example, McKinsey & Co. recently started a sizeable restructuring group. In the past 20 years, a new position has been created to deal with the many complex reorganization issues of companies in crisis – the chief restructuring officer (CRO) – not to be confused with another CRO acronym, the chief risk officer.

Corporate restructuring advisers from investment banks tend to specialize on the “right‐hand side” of the balance sheet, with particular emphasis in assisting the management of distressed companies (or the operations turnaround specialist) to acquire needed capital during the restructuring period and to sell unprofitable or other assets to acquire cash. One type of financing that has proven to be crucial to the early phase of the Chapter 11 process is debtor‐in‐possession (DIP) financing, whereby the new creditors typically have a super priority status over all existing creditors. We discussed this financing mechanism earlier in this book. At the other end of the restructuring period is the so‐called exit financing, whereby the firm needs to emerge from Chapter 11 with sufficient capital to conduct business on a going‐concern basis. Again, the boutique investment bank is a key player in these exit‐financings. Indeed, many times the provider of DIP financing is the same lender of exit financing and/or the distressed investor in the pre‐emergence phase becomes the new owner of the emerged firms' equity securities.

Some of the larger restructuring advisers that specialize in advising debtors are the boutique investment bankers like Lazard Freres, PJT Partners (formerly the Blackstone Group), Miller Buckfire, N. M. Rothschild & Sons, Evercore, and Greenhill, although there are also several smaller successful operations. On the creditor advisory side, the largest advisers are Houlihan Lokey Howard & Zukin, Jefferies, Chanin, FTI, and Giuliani Partners. The latter two are carve‐outs or sales of divisions from accounting firms.

Bankruptcy Reform Bill Impact on Advisory Firms

Leading up to the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005 (BAPCPA), restrictions in the 1978 Bankruptcy Code had historically limited participation of the larger investment banks in Chapter 11 restructuring work, especially if a bank was the underwriter of the debtor's securities within three years before the bankruptcy. While there were exceptions to this restriction and sometimes a formal appeal from one of the stakeholders groups was necessary to eliminate a major investment banking firm (e.g., the switch from UBS to Lazard as the debtor's adviser in the 2005 Trump Casinos & Entertainment Chapter 11), large underwriters were generally restricted under the premise that they were not disinterested professional.

With the passage of BAPCPA, the competitive landscape for distressed firm advisory work changed somewhat. Signed into law on April 17, 2005, and implemented October 17, 2005, this law impacted corporate bankruptcies, as well as consumer filings. It now permits heretofore excluded investment banks to be advisers as long as there is no clear conflict with the financing or other advisory work that helped cause the bankruptcy. Disinterestedness still requires that an entity not have an interest materially adverse to the interests of the estate or any class of creditors as equity security holders, by reason of any relationship or connection or interest in the debtor. So, while a current or former underwriter may be deemed not to still be disinterested, the prospect that other disinterested bulge‐bracket firms will be eligible is very real. In fact, the large investment banks have not entered the financial advisory market in any material way, but continue to provide asset‐backed financing, for example, DIP loans, in the distressed firm market.

We advocate that both the turnaround managers (who are trying to save the business either before filing for Chapter 11 or while in bankruptcy‐reorganization) and restructuring debtor advisers can effectively use distress‐prediction credit scoring models as an early warning tool to assess the financial health of an enterprise or as a type of post restructuring barometer of the health profile of an entity as it emerges. If the firm still looks like a distressed, failing entity upon emergence, then its chances for subsequent distress, indeed the “Chapter 22” situation, would likely be higher than the renewal process should provide. Unfortunately, based on the frequent occurrence of “Chapter 22” or other forms of continued distress (like distressed sales), it appears that the restructuring process is not always successful. Indeed, Gilson (1997), in a study of the success of Chapter 11s, found that too often firms emerge with excessive leverage or operating problems, and Hotchkiss (1995) found that emerging firms often do not perform as well as their industry counterparts. On the other hand, Eberhart, Altman and Aggarwal (1999) found that emerging equities do extremely well in the post‐Chapter 11 one‐year trading period. And recent (2003–2004) evidence (e.g., J.P. Morgan 2004) supports that conclusion.

In conclusion, we advocate that firms be advised to emerge looking like going concerns and that rights offerings as well as equitylike securities, including options and warrants for junior creditors and old equity holders, be used wherever possible so as not to burden the “new” firm with too much fixed cost debt in the early years after emergence.

Government Agencies and Other Purchasers

Many of the larger U.S. government agencies have a policy to screen their vendors as to their staying power and independence from government support should they become distressed. A related issue is whether the vendor will be able to deliver the goods and services that are contracted for. We have learned, over the years, that one of the screens used by government agencies and their auditing counterparts is the Z‐Score model(s). For example, the U.S. Department of Defense had this policy, as did the government's Accounting Audit Agency. If an entity fares poorly by the Z‐Score screen, then it will be screened even more closely and/or passed over as a possible vendor. As such, both the government and those firms seeking to become, or remain, suppliers to the federal or state government should understand the pros and cons of using an automated financial early‐warning model, such as Z‐Score. We would especially suggest that any agency using such an approach do so in conjunction with other screening tools – especially qualitative methods like interviews with existing customers of the vendor.

The use of financial screening models by purchasing agents should not be restricted to public agencies. Indeed private enterprises should also be concerned about the health of their suppliers. This is especially true if the purchaser practices something like a just‐in‐time (JIT) inventory approach to its production process. For example, computer manufacturers, like IBM or Dell, wanted to be assured that the keyboards in their PC fabrications be available at the precise time that the rest of the computer is about ready to be shipped. Another industry where the health of vendors, and of the manufacturers themselves, was of vital concern is the U.S. auto industry in 2005–2007. As its fragile condition became more obvious, going‐concern and staying power probabilities were a pervasive issue. Indeed, many medium and large auto‐part suppliers succumbed even before the major auto manufacturers bankruptcies in 2009 (i.e., Chrysler and GM); some as early as 2004–2005. A related issue to the manufacturer is the cost of supporting a vendor if the latter is sustaining continuing losses and is in jeopardy of failing and having to be bailed out. This was a common occurrence in Japan, and may still be.

M & A Applications

A final left‐hand column of Figure 11.1 application of our Z‐Score model relates to both highly leveraged finance (e.g., LBOs) takeovers and ordinary merger and acquisition selections. As noted earlier, distress predictions are fundamental to any merger transaction that involves massive debt financings. The high profile risk of default involving LBO takeovers was perhaps the major cause of the financial crisis of the late 1980s to early 1990s. Analysis of the acquired firm's existing default vulnerability, as well as post‐LBO scenarios, should be a prominent focus for the private‐equity fund.

With respect to ordinary M&A activity, acquirers are sometimes interested in “bottom‐fishing” to pay a very small price to a firm with good restructuring potential. A reasonable rule of thumb is to purchase a firm in distress for no more than three‐times EBITDA. Of course, many distressed firms have negative EBITDA, so a prospective estimate of cash flow is relevant. We discuss distressed firm valuations earlier in this volume (Chapter 5).