CHAPTER 8

Immunobullous and Other Blistering Disorders

Rachael Morris‐Jones

Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

Introduction

Blisters, whether large bullae or small vesicles, can arise in a variety of conditions. Blisters may result from destruction of epidermal cells (a burn or a herpes virus infection). Loss of adhesion between the cells may occur within the epidermis (pemphigus) or at the basement membrane (pemphigoid). In eczema there is oedema between the epidermal cells, resulting in spongiosis. Sometimes, there are associated inflammatory changes in the dermis (erythema multiforme/vasculitis) or a metabolic defect (as in porphyria). Genetic conditions (Epidermolysis bullosa) affecting adhesion structures can lead to skin fragility, blistering, and epidermal loss.

The integrity of normal skin depends on intricate connecting structures between cells (Figure 8.1). In autoimmune blistering conditions autoantibodies attack these adhesion structures. The level of the separation of epidermal cells within the epidermis is determined by the specific structure that is the target antigen. Clinically, these splits are visualised as superficial blisters which may be fragile and flaccid (intraepidermal split) or deep mainly intact blisters (subepidermal split). Therefore, the clinical features can be used to predict the level of the underlying target antigen in the skin.

Figure 8.1 Section through the skin with (a) intraepidermal blister and (b) subepidermal blister.

Pathophysiology

Susceptibility to develop autoimmune disorders may be inherited, but the triggers for the production of these skin‐damaging autoantibodies remains unknown. In some patients possible triggers have been identified including drugs (rifampicin, captopril, and D‐penicillamine), certain foods (garlic, onions, and leeks), viral infections, hormones, ultraviolet (UV) radiation and X‐rays.

Bullous pemphigoid results from IgG autoantibodies that target the basement membrane cells (hemidesmosome proteins BP180 and BP230). Studies have demonstrated a reduction in circulating regulatory T‐cells (Treg) and reduced levels of interleukin‐10 (IL‐10) in patients with bullous pemphigoid, which partially correct following treatment. Complement activates an inflammatory cascade, leading to disruption of skin cell adhesion and blister formation. The subepidermal split leads to tense bullae formation.

Pemphigus vulgaris results from autoantibodies directed against desmosomal cadherin desmoglein 3 (Dsg3) found between epidermal cells in mucous membranes and skin. This causes the epidermal cells to separate, resulting in intraepidermal blister formation. This relatively superficial split leads to flaccid blisters and erosions (where the blister roof has sloughed off). Pemphigus foliaceus (PF) is a rare autoimmune skin disease characterised by subcorneal blistering and IgG antibodies directed against desmoglein 1 (Dsg1) usually manifested at UV‐irradiated skin sites.

Dermatitis herpetiformis (DH) is caused by IgA deposits in the papillary dermis which results from chronic exposure of the gut to dietary gluten triggering an auto‐immunological response in genetically susceptible individuals. IgA antibodies develop against gluten‐tissue transglutaminase (found in the gut) and these cross‐react with epidermal‐transglutaminase, leading to cutaneous blistering.

Differential diagnosis

Many cutaneous disorders present with blister formation. Presentations include large single bullae through to multiple small vesicles, and differentiating the underlying cause can be a clinical challenge (Table 8.1). The history of the blister formation can give important clues to the diagnosis, in particular the development, duration, durability, and distribution of the lesions – the ‘four Ds’.

Table 8.1 Differential diagnosis of immunobullous disorders – other causes of cutaneous blistering.

| Other causes of cutaneous blistering | Key clinical features | Diagnostic tests | Further reading |

| Epidermolysis bullosa | Neonatal period fragile skin, blisters, erosions usually at sites of pressure/trauma | Skin biopsy done at specialist centres to identify the level of the split and the defect in adhesion | Chapter 8 |

| Erythema multiforme | Target lesions with a central blister, acral sites | Skin biopsy for histology | Chapter 7 |

| Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis | Mucous membrane involvement, Nikolsky‐positive, eroded areas of skin | Skin biopsy for histology | Chapter 7 |

| Chickenpox | Scattered blisters in crops appear over days | Viral swab to detect varicella zoster virus (VZV); serology | Chapter 14 |

| Herpes simplex/varicella zoster virus | Localised blistering of mucous membranes or dermatomal | Vesicle fluid for viral analysis | Chapter 14 |

| Staphylococcus impetigo | Golden crusting associated with blisters | Bacterial swab for culture | Chapter 13 |

| Insect bite reactions | Linear or clusters of blisters, very itchy | Clinical diagnosis | Chapter 17 |

| Contact dermatitis | Exogenous pattern of blisters | Patch testing | Chapter 4 |

| Phytophotodermatitis | Blisters where plants/extracts touched the skin plus sunlight exposure | Clinical diagnosis | Chapter 6 |

| Porphyria | Fragile skin with scarring at sun‐exposed sites | Urine, blood, faecal analysis for porphyrins | Chapter 6 |

| Fixed drug eruption | Blistering purplish lesion/s at a fixed site each time drug taken | Skin biopsy for histology | Chapter 7 |

Development

If erosions or blisters are present at birth then genodermatoses (Epidermolysis bullosa) must be considered in addition to cutaneous infections. Preceding systemic symptoms may suggest an infectious cause such as chickenpox or hand, foot and mouth disease. A tingling sensation may herald herpes simplex, and pain, herpes zoster. If the lesions are pruritic, then consider DH or pompholyx eczema. Eczema may precede bullous pemphigoid.

Duration

Some types of blistering arise rapidly (allergic reactions, impetigo, erythema multiforme and pemphigus), while others have a more gradual onset and follow a chronic course (DH, pityriasis lichenoides, porphyria cutanea tarda, and bullous pemphigoid). The rare genetic disorder epidermolysis bullosa is present from, or soon after, birth and has a chronic course.

Durability

The blisters themselves may remain intact or rupture easily and this sign can help elude the underlying diagnosis. Superficial blisters in the epidermis have a fragile roof that sloughs off easily leaving eroded areas typically seen in pemphigus vulgaris, porphyria, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, staphylococcal scalded skin, and herpes viruses. Subepidermal blisters have a stronger roof and usually remain intact and are classically seen in bullous pemphigoid, linear IgA, and erythema multiforme. Scratching can result in traumatic removal of blister roofs, which may confuse the clinical picture.

Distribution

The distribution of blistering rashes helps considerably in making a clinical diagnosis (Boxes 8.1 and 8.2). In general, immunobullous diseases present with widespread eruptions with frequent mucous membrane involvement. Herpes infections usually remain localised to lips, genitals, or dermatomes. Photosensitive blistering disorders involve sun‐exposed skin.

Clinical features of immunobullous disorders

Clinical features of the different immunobullous disorders (Table 8.2) are discussed in the following subsections.

Table 8.2 Clinical features of immunobullous disorders.

| Immunobullous disorder | Typical patient | Distribution of rash | Morphology of lesions | Mucous membrane involvement | Associated conditions |

| Bullous pemphigoid | Elderly | Generalised | Intact blisters | Common | None |

| Mucous membrane pemphigoid | Middle‐aged or older | Varied | Erosions, flaccid blisters, scarring | Severe and extensive | Autoimmune disease |

| Pemphigoid gestationis | Pregnant | Periumbilical | Intact blisters, urticated lesions | Rare | Thyroid disease |

| Pemphigus vulgaris | Middle‐aged | Flexures, head | Flaccid blisters, erosions | Common | Autoimmune disease |

| Dermatitis herpetiformis | Young adults | Elbows, knees, buttocks | Vesicles, papules, excoriations | Rare | Small bowel enteropathy (gluten‐sensitive), lymphoma |

| Linear IgA | Children and adults | Face and perineum (children) Trunk and limbs (adults) | Annular urticated plaques with peripheral vesicles | Common | Lymphoproliferative disorders |

| Paraneoplastic pemphigus | Older patients | Mucous membranes (mouth/eyes) skin sites | Severe erosive stomatitis, polymorphous skin lesions | Rare | Lymphoproliferative disorders, carcinoma, thymoma, sarcoma |

Bullous pemphigoid

This usually presents over the age of 65 years with tense blisters and erosions on a background of dermatitis or normal skin (Figure 8.2). The condition may present acutely or be insidious in onset, but usually enters a chronic intermittent phase before remitting after approximately five years. Some patients have a prolonged pre‐bullous period in which persistent pruritic urticated plaques (Figure 8.3), or eczema, precedes the blisters. Characteristically, blisters have a predilection for flexural sites on the limbs and trunk. Mucous membrane involvement occurs in about 20% of cases (Figure 8.4). Blisters heal without scarring. Potential triggers include vaccinations, drugs (non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)), furosemide, ACE (angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors and antibiotics), UV radiation, and X‐rays. In children bullous pemphigoid usually follows vaccination, where the condition characteristically affects the face, palms, and soles.

Figure 8.2 Bullous pemphigoid.

Figure 8.3 Urticated plaques in pre‐bullous pemphigoid.

Figure 8.4 Bullous pemphigoid: showing mouth erosions.

Pemphigoid gestationis

This rare autoimmune disorder usually occurs in the second/third trimester of pregnancy. Mothers may have other associated autoimmune conditions. Acute‐onset intensely pruritic papules, plaques, and blisters spread from the periumbilical area outwards (Figure 8.5). Mucous membrane involvement can occur. Babies may be born prematurely or small for dates and can have a transient blistering eruption that rapidly resolves. The maternal cutaneous eruption usually resolves within weeks after birth, but may flare immediately post‐partum.

Figure 8.5 Pemphigoid gestationis on the abdomen.

Mucous membrane pemphigoid (cicatricial pemphigoid)

Patients usually present with painful sores in their mouth, nasal and genital mucosae, and may complain of a gritty feeling in their eyes. Cutaneous lesions occur in around 30% of patients; tense blisters may be haemorrhagic and heal with scarring (Figure 8.6). Scalp involvement can lead to scarring alopecia (Figure 8.7). Symptoms from mucous membrane sites can be very severe, with chronic painful erosions and ulceration that heals with scarring.

Figure 8.6 Mucous membrane pemphigoid: scarring skin eruption.

Figure 8.7 Mucous membrane pemphigoid on the scalp.

Ocular damage (Figure 8.8) can include symblepharon (tethering of conjunctival epithelium), synechiae (adhesion of iris to cornea), and fibrosis of the lacrimal duct (dry eyes) resulting in opacification, fixed globe, and eventually blindness.

Figure 8.8 Mucous membrane pemphigoid: eyes.

Pemphigus vulgaris

Although it is a rare condition, it is more common on Ashkenazi Jews, individuals from India, Southeastern Europe, and the Middle East. Seventy percent of patients develop oral lesions in chronic progressive pemphigus vulgaris. Mucous membrane involvement may precede cutaneous signs by several months. Skin lesions do, however, occur in most patients and are characterised by painful flaccid blisters and erosions arising on normal skin (Figure 8.9). The bullae are easily broken, and even rubbing apparently normal skin causes the superficial epidermis to slough off (Nikolsky sign positive).

Figure 8.9 Pemphigus vulgaris on the trunk.

Slow‐healing painful erosions occur in the mouth, particularly on the soft/hard palate and buccal mucosae, but the larynx may also be affected. The oral cavity lesions may be so severe that patients have difficulty eating, drinking, and brushing their teeth (Figure 8.10). Recognised drug triggers of pemphigus vulgaris include rifampicin, ACE inhibitors, and penicillamine. Paraneoplastic pemphigus is clinically similar to pemphigus vulgaris but with an associated underlying malignancy such as non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma or chronic lymphocytic leukaemia.

Figure 8.10 Pemphigus vulgaris in the mouth.

PF tends to affect patients in middle age and is characterised by flaccid small bullae on the trunk, face, and scalp that rapidly erode and crust. Dugs may induce PF; the most commonly reported are penicillamine, nifedipine, captopril, and NSAIDs.

Dermatitis herpetiformis (DH)

This is an intensely pruritic autoimmune blistering disorder that affects Northern Europeans who are young/middle‐aged adults and is associated with an underlying gluten‐sensitive enteropathy. Several human leukocyte antigen (HLA) types have been identified in patients with DH, most patients carry the HLA DQ2 or HLA DQ8 haplotype and 10% of patients report an affected relative. Cutaneous lesions are characteristically intermittent and mainly affect the buttocks, knees (Figure 8.11) and elbows. The intense pruritus leads to excoriation of the small vesicles which are consequently rarely seen intact by clinicians. Most patients do not report any bowel symptoms unless prompted; but may experience bloating and diarrhoea. Low ferritin and folate can result from malabsorption. Small bowel investigation reveals abnormalities (villous atrophy, raised lymphocyte count) in 90% of patients. There is an increased frequency of small bowel lymphoma in patients with enteropathy.

Figure 8.11 Dermatitis herpetiformis on the knees.

DH patients should be encouraged to follow a strict gluten‐free diet, as this should control the cutaneous and gastrointestinal symptoms and is thought to reduce the risk of small bowel lymphoma. Patients should avoid wheat, rye, and barley. Dapsone and sulfapyridine can be used to control symptoms if dietary manipulation is unsuccessful. DH is a chronic condition and therefore lifelong management is needed.

Linear IgA

Children and adults can be affected by this autoimmune subepidermal blistering disorder. The clinical picture is heterogeneous, ranging from acute onset of blistering to insidious pruritus before chronic tense bullae. In children, the blisters tend to affect the lower abdomen and perineum, whereas in adults the limbs and trunk are most commonly affected (Figure 8.12). Blisters are usually intact and are classically seen around the periphery of annular lesions (‘string of beads sign’) or in clusters (‘jewel sign’). Mucous membrane involvement is common. Reported drug triggers include vancomycin, ampicillin, and amiodarone. Management is similar to that for DH, with patients responding to dapsone and sulfapyridine.

Figure 8.12 Linear IgA on the trunk.

Investigation of immunobullous disease

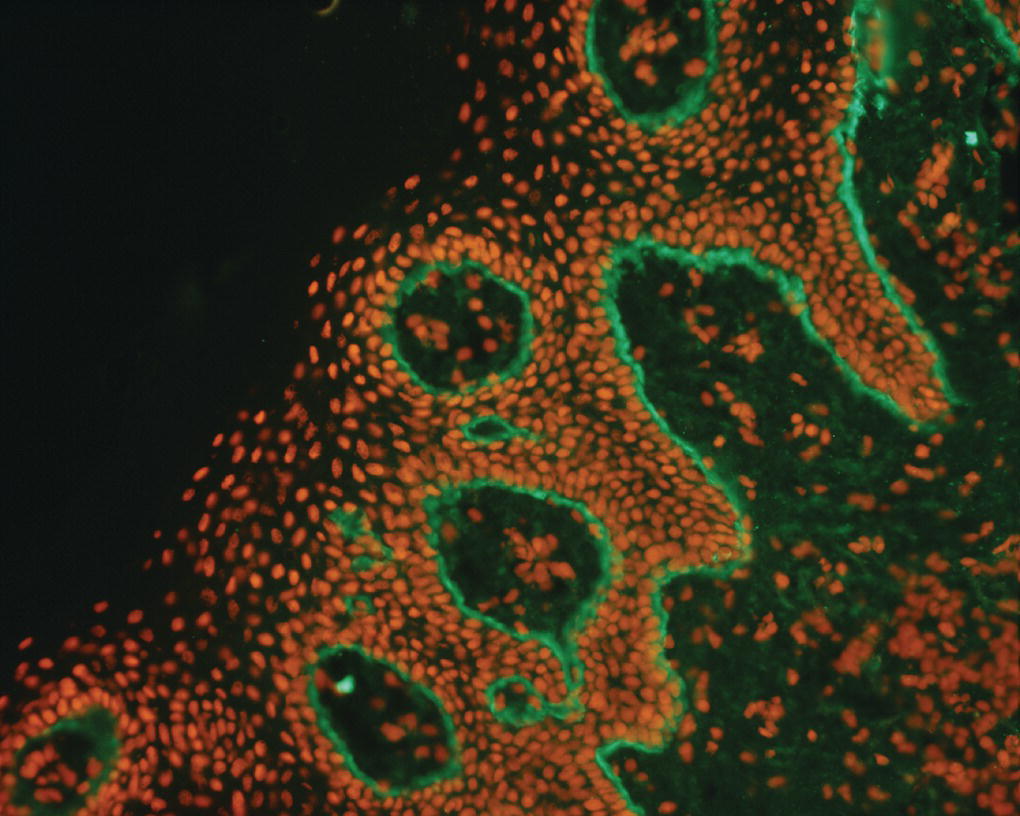

The gold standard for diagnosing immunobullous disease is direct immunofluorescent analysis of perilesional skin. Skin biopsies are taken across a blister/erosion; the lesional part is sent for histopathology and the adjacent skin sent for direct immunofluorescence (Table 8.3). The histological features can be diagnostic or supportive of the diagnosis. The level and pattern of immunoglobulin staining on direct immunofluorescence is usually diagnostic. Indirect tests involve taking the patients serum and applying this to a substrate such as monkey oesophagus or salt‐split human skin substrate (Figures 8.13–8.16). Circulating intercellular antibodies may be detected in patients with pemphigus, leading to titre measurement which may help guide management.

Table 8.3 Skin biopsy findings in immunobullous disorders.

| Immunobullous disorder | Histology features | Immunofluorescence features |

| Bullous pemphigoid | Subepidermal blister containing mainly eosinophils | Linear band of IgG at the basement membrane zone |

| Pemphigoid gestationis | Subepidermal blister containing mainly eosinophils | Linear band of C3 at the basement membrane zone |

| Mucous membrane pemphigoid | Subepidermal blister with variable cellular infiltrate | Linear band of IgG/C3 at the basement membrane zone |

| Pemphigus vulgaris | Suprabasal split (basal cells remain attached to basement membrane, looking like ‘tombstones’) | IgG deposited on surface of keratinocytes in a ‘chicken‐wire’ pattern |

| Dermatitis herpetiformis | Small vesicles containing neutrophils and eosinophils in the upper dermis | Granular deposits of IgA in the upper dermis (dermal papillae) |

| Linear IgA | Subepidermal blisters with neutrophils or eosinophils | Linear deposition of IgA at the basement membrane zone |

| Paraneoplastic pemphigus | Suprabasal split leading to acantholysis with lichenoid interface dermatitis, features can be variable | IgG or C3 at the basement membrane (indirect IgG Rat bladder) ELISA serum antibodies to envoplakin and periplakin |

Figure 8.13 Histopathology of bullous pemphigoid.

Figure 8.16 Immunofluorescence of pemphigus vulgaris.

Management of immunobullous disease

Tense intact blisters can be deflated using a sterile needle (the roof of the blister should be preserved as this provides a ‘natural wound covering’). Use of non‐adherent dressings or a bodysuit can be used to cover painful cutaneous erosions. Liquid paraffin should be applied regularly to eroded areas to help retain fluid and prevent secondary infection.

In most cases of immunobullous disease immunosuppressive treatments are required. Bullous pemphigoid presenting in an elderly patient may respond to intensive potent topical steroids to affected skin. Reducing courses of systemic corticosteroids can be helpful in the short term to reduce the pruritus and development of new lesions, but most patients are maintained on doxycycline or azathioprine in the longer term. Other treatments used include methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, and the anti CD‐20 biological agent rituximab.

Severe forms of pemphigoid gestationis may require high doses of systemic corticosteroids which can usually be rapidly reduced during the post‐partum period. Care should be taken if mothers are breastfeeding as most drugs pass into breast milk.

Mucous membrane pemphigoid is chronic and resistant to many treatments, making management difficult. Oral disease may respond to topical steroids and tetracycline mouthwashes. Ophthalmic disease should be managed carefully as scarring can result in blindness. Topical steroid drops and mitomycin may be useful, but usually systemic immunosuppression such as mycophenolate mofetil is required.

The management of pemphigus vulgaris has been transformed by the use of rituximab which is a biological agent with anti‐CD20 activity that depletes antibody‐producing B‐cells. A dose of 1 g of rituximab given at day 1 and 15 induces remission in 70% of patients by 70 days and 86% of patients at 6 months. About 40% of patients will subsequently relapse after two infusions of rituximab usually after many months and studies show that when they receive further infusions of rituximab at 500 mg, further disease remission can be achieved. In most cases, all other immunosuppressive medications can be stopped, leading to a reduction in long‐term morbidity and mortality induced by medications.

A gluten‐free diet is an effective way of controlling the cutaneous eruption of DH as well as relieving gastrointestinal symptoms and reducing the risk of developing small bowel lymphoma. Dapsone or sulfapyridine are both helpful in controlling the disease.

Paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP) usually responds to treatment of the underlying tumour. However, it can continue for up to two years after resection of, for example, a thymoma. High‐dose oral prednisolone (1 mg/kg/day) can help to diminish the cutaneous lesions; however, the oral involvement is often refractory to treatment. The use of rituximab has been disappointing in the management of PNP, though some patients with underlying non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma do respond.

Further reading

- Burge, S. and Wallis, D. (2011). Oxford Handbook of Medical Dermatology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Groves, R. (2016). Immunobullous Diseases. In: Rook's Textbook of Dermatology, 9e (ed. C.M. Griffiths, J. Barker, T. Bleiker, et al.). Chichester: Wiley.

- Hertl, M. (2011). Autoimmune Diseases of the Skin: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, Management. New York: Springer‐Verlag/Wein.