JANUARY 15, 2014

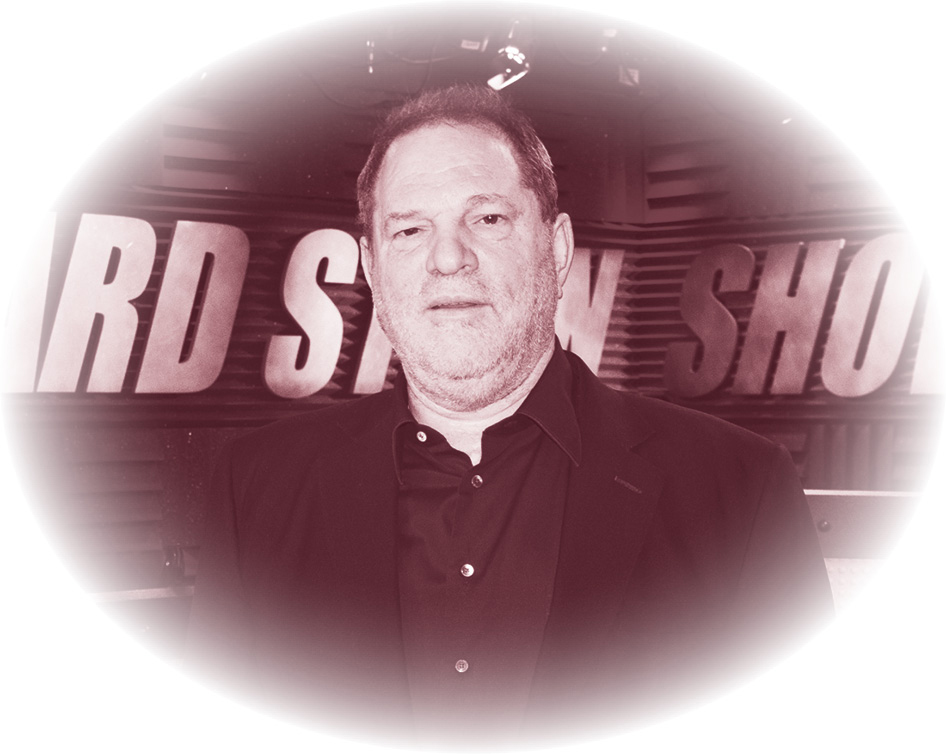

I went back and forth about whether or not I should include this interview. I really struggled with it, right up until the very last draft. I lost a lot of sleep over it. I would wake up in the middle of the night and lay in bed thinking about Harvey Weinstein—which, let me tell you, is a far cry from my usual midnight masturbatory fantasies of stepmom porn. I wanted the book to generally be very positive, and when I reread this interview, a heavy feeling came over me. The common thread between these conversations is honesty. Each person lets their guard down and is completely candid, whether it’s Conan O’Brien talking about depression, or Jon Stewart discussing his complicated relationship with his father, or Sia describing her bipolar II diagnosis. It takes guts to be so forthcoming, and I’m in awe of how brave these guests are to get so personal. I have so much respect for them, and I’m honored that they choose to place their trust in me. That’s not something I take lightly. So I wrestled with putting Harvey in the book, as well as the Bill O’Reilly interview that comes later, because they didn’t show the same honesty and introspection as everyone else, and I didn’t want to reward them for that. I didn’t want to give them any further attention or recognition. More than anything, though, my reluctance to include Harvey’s interview was because I didn’t want to cause any more pain to the women who came forward. I didn’t want to offend or upset them. I took the interview out and put it back in a few times, but ultimately I decided to keep it in—Bill’s too—because, as I mentioned earlier in the introduction, I think it is an important reflection of our times.

Not only did I question Harvey about the highs of his career—his incredible films and the coveted place he held in show business—but I delved into the casting couch. We discussed sex and the power of the producer, and Harvey gave all of the appropriate answers. Like a good Boy Scout earning a merit badge, he said all the right things, and clearly understood the destructive nature of abusing that power and the devastation that would occur if he were out of control. Reliving the conversation only makes me angrier. When I asked him if he ever took advantage of his position, he laughed it off and told me, “It doesn’t work that way . . . the movies are too expensive. The risks are too great. It doesn’t happen that way.” He treated my question as if it was ridiculous, not even in the realm of possibility for anything inappropriate to happen.

When I think about this, it all seems so tragic and sad. It reads like a story Harvey would make into a movie. A lonely boy who loved to read, made brilliant movies and careful choices, against all odds was embraced by the cool kids, threw the best Golden Globes after-party but, ultimately, tragically destroyed his life—and the lives of others, as we are learning. How could someone so brilliant not see what he was doing? In the end, I’m just pissed off for the women who were hurt.

Howard: What would you call your job? Are you a movie mogul?

Harvey: No.

Howard: You are.

Harvey: What I am is a guy who makes movies. I like to be called a filmmaker, if you will.

Howard: The thing that amazes me about you is how you pick these movies. From the earliest part of your career, you walk into a room, people hand you scripts, they pitch you ideas. You must get this all day.

Harvey: Yup.

Howard: Some movies might seem obvious to us. “Oh yeah. Of course, Harvey. Put money into these.” But there are certain movies that you have made in your career that I would have said, “Are you out of your fucking mind?” The one where he’s the stuttering king. What the hell is the name of that—?

Harvey: The King’s Speech.

Howard: Who would put money into this thing? You think, “Yeah, it’ll be a little art film.” The film grossed $414 million. Even you had to be shocked.

Harvey: You know, Howard, when I was a boy, I got my eye poked out. Born in Brooklyn, grew up in Queens.

Howard: Do you have one eye?

Harvey: I have a bad eye. And I couldn’t go to school. There was a librarian next door. I was bored to death. There was no three hundred channels. And radio wasn’t cool. You hadn’t arrived on the scene yet. So I asked Frances Goldstein, the seventy-two-year-old librarian—I said, “Help me do something.” And then, at twelve, I fell in love with books. I fell in love with literature. I started with H. G. Wells’s Outline of History through War and Peace. I’d read two or three books a week.

Howard: Is that the key? You’ve got to love to read.

Harvey: The key is, the scripts are in the words. When I read The King’s Speech, you could even tell in the script, Howard, how moving it was. The story of this friendship, the story of this guy overcoming something—it moved me emotionally. And I felt if it moved me emotionally then it would move audiences. So this whole mogul thing is complete bullshit.

Howard: How many scripts do you read a week?

Harvey: I read probably five or six, and the company probably reads a hundred.

Howard: Most guys at your level don’t read the scripts that much anymore, right? They just kind of check out and hire people to read for them.

Harvey: I’ll give you the best Hollywood story that I’ve never been able to say on the air, and I’ll tell it to you first. This is what I do. I’m not the mogul. But this is what I do. Years and years ago, John Gordon, a producer who used to work for me, and Kevin Smith, the guy who created Clerks, say, “Yeah, we just read a script by these two young actors. It’s fantastic. It’s called Good Will Hunting. We want you to read it. They need a million dollars. They just got their script out of Warner Brothers and they need one million dollars, otherwise Warner Brothers is going to make the movie with DiCaprio and Brad Pitt, and it’s going to be directed by Michael Mann.” I read the script. I have a meeting with these guys. Kevin Smith and John Gordon are there. They say, “What do you think of the script?” I say, “I think the script is great, but on page sixty the guy who Robin Williams played and the other professor, they give each other a blow job. I don’t understand that blow-job scene.” And Matt and Ben said to me, “We wrote that for studio executives. You were the only one who ever pointed it out. We had meetings with Warner, MGM, Paramount. We just wanted to see who the fuck read this goddamn thing.”

Howard: That is an amazing story.

Harvey: And that is how Good Will Hunting got made.

Howard: The movie business is so scary. It’s like gambling, really, when you think about it. You could have the best script in the world, the best movie, and then it just all screws up. And when it doesn’t go right, it has to be heartbreaking.

Harvey: It’s human nature, unfortunately, that you have to deal with. You have a beautiful script, and if the director’s drunk or, you know . . .

Howard: Here’s what I think is brilliant. The movie The Artist. $15 million to make. I wouldn’t have put a dime into this thing. If you told me, “Howard, I’m gonna give you a gift. If you put a million dollars into The Artist, I’m gonna give you part of the gross.” I would have said to ya, “Fuck you. You’re insane.” It grosses $133 million. On paper, you think, “Well, it doesn’t have a superhero. What am I gonna do with this movie?”

Harvey: Howard, I call my company. I go, “Guys, I wanna do a movie.” They go, “Great.” This is after The King’s Speech wins an Oscar. “But I’ve got a few things I want to talk to you about. Black and white.” And the guys go, “Black and white? You just won the Oscar. That’s fine.” I say, “It’s gonna have French guys in the movie, but the subtitles will be in English.” They go, “Okay, it’s a foreign-language film. We’ve done that before with you.” I say, “There’s one other little caveat: it’s silent.” They go, “You’re doing a silent movie?” They literally bring me to the board of directors, and the big thing for me—I’m so used to autonomy, Howard, I didn’t even know we had a board of directors.

Howard: Like, who are these guys? Who is this board of directors?

Harvey: I mean, Goldman Sachs is on the board.

Howard: These are the guys who put up the money.

Harvey: [Advertising group] WPP. They’re part of the financial structure of the company. We put in money, they put in money. And these guys are going, “You’re sure? Black and white? Silent movie?”

Howard: People still challenge you, though?

Harvey: They challenged me on that one. And they’re right to challenge me. But I just had an instinct.

Howard: Have you ever been stopped from doing a movie by your board of directors and regretted it?

Harvey: I developed a project called Lord of the Rings. Maybe you heard of it.

Howard: Now, this is an amazing story to me, the Lord of the Rings story.

Harvey: When I was in college, I had hair. I remember my hair. And I sat around and smoked cigarettes. Everybody was into The Lord of the Rings. And I loved it. It was action, heroic. You know, the subtext was World War II, and how do we deal with evil. So when the opportunity came to me to do this—’cause I had done Peter Jackson’s Heavenly Creatures with Kate Winslet. First time she made a movie. First time Peter got nominated. So Universal and I were going to combine on Lord of the Rings. They said, “This is a daunting project.” They drop out. Now it’s just me.

Howard: Daunting because financially it’s a lot. How much does it cost to make?

Harvey: At the time, it was going to cost $180 million to do the three. But more importantly, to develop the technique, the thing that you see, the thousands of armies, the amazing special effects, I had to write a check for $10 million to develop a company called Weta. And then we wrote the three scripts. I loved the scripts. And then we were able to show Disney what it looked like: ten thousand individual soldiers fighting. The battle scene was great.

Howard: Clear something up for me. You sell your film company, Miramax, to Disney. You make a lot of dough on that. It seems like the right decision to make, but you were in the middle of trying to get Lord of the Rings done. Disney looks at Lord of the Rings and says, “Forget it. We don’t want it.”

Harvey: Michael Eisner in particular. I don’t want to blame all of Disney. There were a lot of executives there who wanted to do it. But the boss of the studio said to me, famously, “I don’t think anybody’ll see this.” And I go, “Michael, there are so many students and people around the world who’ve read these incredible books. And these three scripts are great.” He goes, “I don’t believe that. And these hobbits and elves and dwarfs and, you know, whatever—”

Howard: It’s make-believe. We don’t believe in Spider-Man either. But he still said no. Let’s not be so arrogant to say Michael Eisner didn’t get it. A lot of people would have balked at the price tag. You’ve got balls of steel and you’ve got some special vision.

Harvey: So what I said to him was, “Look, we executive-produce the thing individually, and we can get 5 percent of the gross if we do this.” And Michael said, “All right, I’ll split it with you. Nobody’s going to see it. Your gross is not going to be worth anything.” Well, the three movies grossed $2.3 billion. I actually said to Michael, “I want it for my kids, for their college education. And now I’m just shopping for which university to buy.” Is Harvard for sale?

Howard: Yes, everything’s for sale.

Harvey: Okay, I’m going there today.

Howard: So Disney did participate?

Harvey: They got half of the gross.

Howard: How much did the three movies gross altogether?

Harvey: $2.3 billion in the theaters and another probably $2 billion in the ancillaries—$4 billion.

Howard: Do the math for me. Five percent of $4 billion. I could never figure that out.

Harvey: But then some goes back to the theaters. It’s about $100 million, $125 million. So they probably got sixty and we got sixty. But I have to split with my brother. My mom likes that.

Howard: Sixty million dollars is a lot of money. But doesn’t it sort of freak you out that you had to give away half of that to Disney? Because you really were the guy who was behind pushing this thing through. Does that keep you up at night?

Harvey: No.

Howard: It doesn’t?

Harvey: No. It bothered me at the time. Now we have The Hobbit, and Warner Brothers is saying to us we have the first Hobbit. The other two don’t count. “You only get one Hobbit.” I go, “But you need three movies to tell the story of The Hobbit.” They go, “No, it’s only one movie.” I go, “Well, why do you keep calling the other two The Hobbit?” Anyhow, welcome to Hollywood.

Howard: Those Golden Globes look like fun, Harvey. It must be great to be the king. Who was at your table?

Harvey: First of all, there was a magnum of champagne at my table. Does that happen at the Academy Awards? We had a few drinks—

Howard: That makes it fun, doesn’t it?

Harvey: Yeah. So Meryl Streep was at my table, Julia Roberts was at the table, Taylor Swift was at the table. These were all nominees from our company. Idris Elba was at the table, and there were guests, husbands, you know. And then U2 was at the other table with Chris Martin, with my brother.

Howard: That’s fun. Then you threw a party afterward, right?

Harvey: Mm-hmm.

Howard: And the list of people at the party, I read in the paper, was like something fucking crazy. Everyone’s gotta go to your party.

Harvey: They don’t have to go. What they understand about our parties is we don’t compete. So in the room, I’m making a movie with Amy Adams next year. I’m not mad that she won. I’m doing something with Bradley Cooper. I’m happy that he’s nominated.

Howard: Why is it important to throw these parties? Does it make it so everyone wants to do business with you?

Harvey: First of all, it’s cathartic. No matter what anybody says, nobody’s that cool. You do get into it. You do want to win. I mean, in those hours that you’re there. And you want to let off steam at the end of it. So it’s just a fun way of getting people together.

Howard: Silver Linings Playbook was your movie, wasn’t it?

Harvey: Yeah.

Howard: What did that make, like $430-something million?

Harvey: It grossed $130 [million] in the US and about another $120 million—a quarter of a billion dollars. It was a $20 million movie.

Howard: Be honest with me: did you expect that movie to break that big?

Harvey: Again, I never expect anything to do anything. But I will tell you that David O. Russell is one of our premier directors. I mean, he will go down in history as great as great can be. He writes beautifully, and he directs even better.

Howard: So when he came to you with that, you were just like, “Okay, I read it. Boom, I’m giving you the money to make the movie.”

Harvey: See, Howard, here’s the difference. Your show is going to clean up my reputation once and for all. Silver Linings, a young woman in my office came to me when I first started the Weinstein Company—this is how long it takes to get your own production slate. Previous to that, I was doing old movies and Miramax things that I developed. She came to me and said, “Read this book. It’s called Silver Linings Playbook.” I said, “Is it a best-seller?” She said, “No, it’s just great.” I read the book. I bought the rights to the book.

Howard: How much did you pay?

Harvey: Fifty grand, against an option for another hundred or two hundred thousand if it gets made. And I hired David O. Russell to write the screenplay. I said, “David, here’s a book. Read it. If you’d like to write this screenplay, I’d love you to write it, and then you can go on to direct it.”

Howard: Wow. So really his project in every single way.

Harvey: It’s his project, except we found the book. And so this is the thing that people go, “Oh, he’s a mogul.” The image of a mogul I have is a guy who smokes cigars, not a guy who reads three books a week and ten or twelve scripts.

Howard: At the end of the day, you’re a guy who loves to read, and when you see a good story, you know it.

Harvey: Yeah, that’s it. That’s what I do.

Howard: But what about the accoutrements? I mean, your wife is gorgeous.

Harvey: Thank you.

Howard: By the way, how old are you now? Sixty-one?

Harvey: Yeah.

Howard: You got a one-year-old?

Harvey: I have an eight-month-old.

Howard: That couldn’t have been your idea.

Harvey: [laughs]

Howard: The fuck is that? Are you home at all with this kid? I mean, good Lord.

Harvey: Of course.

Howard: Are you? No you’re not.

Harvey: [laughs] Yes I am, Howard. By the way, that kid travels everywhere with us. Everywhere.

Howard: Why not stay single? I gotta figure every starlet in Hollywood wanted to at least blow you, you know what I’m saying?

Harvey: [chuckles]

Howard: Did you ever get to experience the . . . I’m gonna say the mogul aspect? Do a little coke, hang out with, you know, I don’t know, Julia Roberts. Give you a hand job. Something. You never got any of that?

Harvey: Howard, as you know only too well, it doesn’t work that way.

Howard: It doesn’t really?

Harvey: No. I’ll tell you who it works that way for. It works that way for the actors. You know producers are—

Howard: No, come on. Every girl knows that if she’s a competent actress and she could get on your good side, you could make her a star over-fucking-night. Don’t fucking tell me it doesn’t work that way.✦

Harvey: Howard, I wish. The movies are too expensive. The risks are too great. It doesn’t happen that way.

Howard: You can’t walk into the room, pull your pants off, and say, “Okay, honey, let’s talk. . . .”

Harvey: John Frankenheimer, the great director, told us stories about his day in the movies. We were born way too late.

Howard: I’ve read about the great moguls, the Louis B. Mayers. They got blow jobs.

Harvey: [laughs] I assume. But these guys, this round, nothing.

Howard: Really?

Harvey: Really. I hate to disappoint you.

Robin: It’s not even fun anymore.

Howard: I know a few famous directors. I’ve asked them the same question.

Harvey: Directors are different because directors can make the decisions on the casting.

Howard: I’ll tell you, though, I know a couple of famous directors. I’m not going to embarrass them by telling, because I’ve talked to them off the air. They tell me they never really got laid that much.

Harvey: It’s really nothing. Nope.

Howard: Well, maybe that’s an honorable thing too. Because, really, to abuse your power—

Robin: Yeah, shouldn’t women be able to get into the movie business without all that?

Howard: Hell, no.

Harvey: Of course. Not only that, but you have women like Meryl Streep and Julia Roberts who are deeply committed to excellent causes. And Charlize Theron—

Howard: She’s a great beauty, Charlize Theron.

Harvey: Not only are they great beauties, but they’re so bloody intelligent and brilliant. You sit down with a girl like that, you don’t want to do stupid shit. You want to just talk to them and say, “Be in my movie, please.” Because you know what they do? They enhance the material.

Howard: There are big fucking egos on these films. It’s got to be kind of a weird thing. When you’re partying with everybody at your big parties, you’re trying to be loose. You’re trying to be the fun guy, the guy everyone wants to do business with. But then when you’re actually doing business with people, you’ve got to come off like a fucking executive who means business. It’s almost like parenting, being in your role. Like, you’ve got to walk in and show everybody: enough with the bullshit.

Harvey: How come it doesn’t work that way with my kids?

Howard: I know. Well, that’s a whole different story.

Harvey: I mean, I have four daughters. I say, “Girls, let me tell ya. I’m Dad. This is how it is. This is what we’re going to do.” And they say, “Dad, please stop. You’re annoying. Whatever. We’ve got more important things to do.” They’re all texting, you know, etcetera.

Howard: I can be so effective at work and so in control, and then when I’m around my kids I’m like, “I don’t know what to do, because nobody’s listening. Nobody cares.”

Harvey: My kids say, “Dad, come on, you don’t know what’s going on. You don’t know the music. You don’t know this, you don’t know that. Here are the books you should be doing. Here’s the film you should be making.” And when I get to the office and someone says, “Can I get you a coffee? Can I get you a water?” And I say, “Thank you, dear God.” People asked me how I mellowed out: I have four daughters, one son. Those four daughters, I mean . . .

Howard: Do they want to be in the business?

Harvey: No. I mean, they all know the business.

Howard: Your wife, what a powerhouse. She’s talented. She has the clothing line. And boy oh boy, sex with her must be through the roof.

Harvey: [laughs]

Howard: I see her as very sexual. Some women, you see them, you don’t get too charged up. Do you worry about her running around behind your back at all?

Harvey: No.

Howard: How do you know?

Harvey: She’s a great woman.

Howard: You know that she loves you and you love her.

Harvey: Yes, yes. It’s the same thing you have with Beth.

Howard: It’s a solid marriage.

Harvey: It’s a solid marriage.

Howard: You’re very happy.

Harvey: I love her. She’s great.

Howard: And you don’t dream about strange pussy or anything?

Harvey: [laughs] I dream about Lord of the Rings.