1 Early Rome

1. Finding the religion of the early Romans

The origins of Roman religion lay in the earliest days of the city of Rome itself. That, at least, was the view held by the Romans – who would have been very puzzled that we should now have any doubt about where, when or how most of their priesthoods, their festivals, their distinctive rituals were established. Roman writers, from poets to philosophers, gave detailed accounts of the founding of Rome by the first king Romulus (the date they came to agree was – on our system of reckoning – 753 B.C.): he consulted the gods for divine approval of the new foundation, carefully laying out the sacred boundary (the pomerium) around the city; he built the very first temple in the city (to Jupiter Feretrius, where he dedicated the spoils of his military victories); and he established some of the major festivals that were still being celebrated a thousand years later (it was at his new ritual of the Consualia, for example, with its characteristic horse races and other festivities, that the first Romans carried off the women of the neighbouring Sabine tribes who had come to watch – the so-called ‘Rape of the Sabines’).1

But it was in the reign of the second king Numa that they found even more religious material. For it was Numa, they said, who established most of the priesthoods and the other familiar religious institutions of the city: he was credited with the invention of, among others, the priests of the gods Jupiter, Mars and Quirinus (the three flamines), of the pontifices, the Vestal Virgins and the Salii (the priests who danced through the city twice a year carrying their special sacred shields – one of which had fallen from the sky as a gift from Jupiter); and he instituted yet more new festivals, which he organized into the first systematic Roman ritual calendar. Henceforth some days of the year were marked down as religious, others as days for public business. Appropriately enough, this peaceable character founded the temple of Janus, whose doors were to be shut whenever the city was not at war. Numa was the first to close its doors; 700 years later the emperor Augustus proudly followed suit – but it was a rare event in Rome’s history.2

Roman writers recognized that their religion was based on traditions that went back earlier than the foundation of the city itself. Long before Romulus came on the scene, the site of Rome had been occupied by an exile from Arcadia in Greece, King Evander, who had brought to Italy a variety of Greek religious customs: he had established, for example, rites in honour of Hercules at what was called the ‘Greatest Altar’ (Ara Maxima) and it was because of this, so Romans explained, that rites at the Ara Maxima were always carried out in a recognizably Greek style (Graeco ritu).3 Evander was also believed to have entertained the Trojan hero Aeneas, who had fled the destruction of his own city and sought safety (and a new site to re-establish the Trojan race) in Italy. (Fig 1.1) This story found its definitive version in Virgil’s great national epic, the Aeneid – which includes a memorable account of the guided tour that Evander gave Aeneas around the site of the city that was to become Rome. Aeneas himself had a major part to play in the foundation of the Roman race, bringing with him the household gods (Penates) of his native land to a new home and renewed worship among the Romans. But he did not found the city itself; he and his son established ‘proto-Romes’ at Lavinium and Alba Longa. Only later was the statue of the goddess Pallas Athena that Aeneas had rescued from Troy (the Palladium) moved to the temple of Vesta in the Roman Forum, to be tended by the Vestal Virgins throughout Roman time.4

Fig. 1.1 Terracotta statuette of Aeneas carrying his father Anchises, one of several found in a votive deposit in Veii, fourth century B.C. Aeneas’ escape from burning Troy symbolizes the birth of a new Troy in Italy, a myth widely known in archaic Latium and Etruria – and not at that time restricted to Rome. (Height 0.21m.)

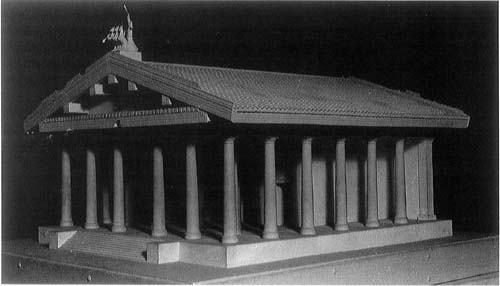

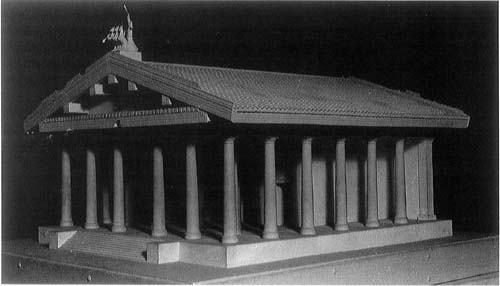

The kings that followed Numa also contributed – though in a less dramatic way – to the religious traditions of Rome. The rituals of the fetial priests, for example, which accompanied the making of treaties and the declaration of war (part of these involved a priest going to the boundaries of enemy territory and hurling a sacred spear across) were devised under the third and fourth rulers, Tullus Hostilius and Ancus Marcius; the fifth king, Tarquin the Elder, an immigrant to Rome from the Etruscan city of Tarquinii, laid the foundations of the temple of Jupiter, Juno and Minerva on the Capitoline hill (a temple that became a symbol of Roman religion, and hundreds of years later was widely imitated across the whole of the Roman empire); the sixth, Servius Tullius, marked the new city’s growing dominance over its Latin neighbours by establishing the great ‘federal’ sanctuary of Diana on the Aventine hill, for all the members of the ‘Latin League’. By the time the last king, Tarquin the Proud, was deposed (traditionally in 510 B.C.), and the new republican regime with its succession of annually elected magistrates established, the structure of Roman religion was essentially in place. Of course, all kinds of particular changes were to follow – new rituals, new priesthoods, new temples, new gods; but (in the view of the Romans themselves) the basic religious framework was pretty well fixed by the end of the sixth century B.C.5

There is, then, no shortage of ‘evidence’ about the earliest phases of Roman religion; the Greek historian of Rome, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, for example, devotes four whole books of his history (much of it concerned with religious institutions) to the period before the Republic was established, the first two covering only to the end of Numa’s reign.6 The problem is not lack of written material, but how we should interpret and make sense of that material. For all the accounts we have of Rome’s earliest history are found in writers (Dionysius amongst them) who lived in the first century B.C. or later – more than 600 years after the dates usually given to the reigns of Romulus and Numa. None of our sources is contemporary with the events they describe. Nor could their authors have read any such contemporary accounts on which to base their own: so far as we know, there were no writers in earliest, regal Rome; there was no account left by Numa, say, of his religious foundations. Even for the earliest phases of the Republic (in the fifth and fourth centuries B.C.), it is very hard to know what kind of information (or how reliable) was available to historians writing three or four centuries later.7

Judged by our own standards of historical ‘accuracy’, these ancient accounts of early Rome and its religion are inadequate and misleading; they construct an image of a relatively sophisticated society, more like the city of the first century B.C. than the hamlet of the eighth century. Projections of the contemporary world back into the distant past, they are more myth than history. It is certain that primitive Rome was under the control of men the Romans called reges (which we translate as ‘kings’, though ‘chieftains’ might be a better term). But many modern historians would now be very doubtful whether at least the two earliest of them – Romulus and Numa – existed at all, let alone whether they carried out the reforms ascribed to them. That, of course, is precisely the point. The writers we are referring to (historians such as Dionysius or Livy; poets such as Virgil or Ovid) set little store by ‘accuracy’ in our narrow sense. For them, the stories of early Rome, which they told, retold and (sometimes no doubt) invented, were ‘true’ in quite a different way or, better, were doing a different kind of job: they were using the theme of the city’s origins as a way of discussing Roman culture and religion much more generally, of defining and classifying it, of debating its problems and peculiarities. These stories were a way in which the Romans (or, in the case of Dionysius and others, the Greek inhabitants of the Roman empire) explained their own religious system to themselves; and as such they were inevitably embedded in the religious concerns and debates of their writers’ own times. As we shall see, for example, stories of the apotheosis of Romulus (into the god Quirinus) were told with particular emphasis, elaborated (some might say invented), around the time of Julius Caesar’s deification in the 40s B.C. Romulus’ ascent to heaven offered, in other words, a way of understanding, justifying or attacking the recent (and contested) elevation of the dead dictator.8

These images of early Rome are central to the way the Romans made sense of their own religion; and so too they are central to our understanding and discussion of Roman religion. It would be nonsense to ignore the figure of ‘Numa’, the father of the Roman priesthood and founder of the calendar, just because we decided that King Numa (715–672 B.C.) was a figment of the Roman mythic imagination. We shall return to this early history at many points through this book – using (for example) Ovid’s explanations of the origins of particular festivals as a way of rethinking their significance in the Rome of Ovid’s own day, or exploring the way the myths of Aeneas and Romulus were used to define the position of the first emperor Augustus (and were themselves re-told in the process). But this earliest period will not bulk particularly large in this first chapter on the religion of early Rome.9

This chapter is concerned with what we can know about the religion of Rome before the second century B.C., when for the first time contemporary writing survives in some quantity. This was the period in which the distinctive institutions of later periods must have taken shape. But how can we construct an (in our terms) ‘historical’ account of that religious world, when there are no contemporary written records beyond a few brief, and often enigmatic, inscriptions on stone, metal or pot? This first section concentrates on that question of method: reviewing particular documents and literary traditions which have been claimed to give a privileged access to accurate information on the earliest phases of Rome’s religion; exploring some of the recent archaeological discoveries from Rome and elsewhere which have changed the way we can talk of particular aspects of that religion; and discussing various theories that have been used to reconstruct its fundamental character.

One group of documents that has often been given a special place in reconstructions of early Roman religion is a group known (collectively) as ‘the calendar’. More than 40 copies (some of them, admittedly, very fragmentary) of a ritual calendar of Roman festivals, inscribed or painted on walls, survive from Rome and the surrounding areas of Italy, mostly dating to the age of Augustus (31 B.C. to A.D. 14) or soon after.10 No two of these calendars are exactly the same: the lists of festivals are slightly different in each case; and the additional information on the festivals that is regularly included ranges from terse notes on the god or temple involved to more extended entries of several lines, apparently drawn from antiquarian commentators, describing or explaining the rituals. None the less the calendars are all recognizably variations on the same theme, selecting from the same broad group of festivals. We shall be referring to these calendars in many contexts through the chapters that follow. For the moment, we want to stress one small but significant feature in their layout that they all have in common: some of the festival entries are inscribed in capital letters while others are in small letters. The capital-letter festivals are essentially the same group from calendar to calendar, roughly 40 in all – and including, for example, the Lupercalia, the Parilia, the Consualia, the Saturnalia. It seems virtually certain that they form an ancient list of festivals, preserved within the later documents.11

But how ancient? We do not know when the characteristic form of time-keeping that underlies these calendars was introduced at Rome – maybe in the course of the republican period, maybe earlier; nor do we know whether its introduction coincided with the fixing of this particular group of capital-letter festivals, or not. It is hard to forget completely the mythic ‘Calendar of Numa’: certainly some of these festivals contain strange-seeming rituals and have often been interpreted as reflecting archaic social conditions; besides, though some of these festivals (such as those we mentioned above) were still very prominent in the first century B.C., some were totally obscure at the time the calendars were being inscribed; and in no case can it be proved that a capital-letter festival was introduced later than the regal period.12 On the other hand the idea of the ‘Calendar of Numa’ (that is, of a very early canonical group of festivals) could be misleading. Even accepting, as is likely, that the capital-letter festivals do represent some ancient list, the purpose of that list remains quite uncertain: not necessarily the oldest festivals of all; perhaps, the most important at some specific date; perhaps even the most important to some individual on some specific occasion, that has somehow become embedded in the tradition.13 We certainly cannot assume that any festival not in capitals must be a ‘later’ introduction into the calendar.

A list of the names of early festivals on its own, however, tells us little – without some idea of their content and significance. Here we must turn to a variety of later sources which offer details of the rituals of these festivals and of the stories, traditions and explanations associated with them. By far the richest source of all is Ovid’s Fasti, a witty verse account of the first six months of the Roman calendar and its rituals.14 Ovid, however, was writing in the reign of Augustus and much of what he has to offer does not consist of traditional Roman stories at all, but of imported Greek ones. So, for example, explaining the odd rituals of the festival of the goddess Vesta (one of our capital-letter group), which involved hanging loaves of bread around asses’ necks, he brings in a farcical tale of the Greek god Priapus: once upon a time, he says, at a picnic of the gods, this grotesque and crude rapist crept up on Vesta as she sprawled, unsuspecting, on the grass; but an ass’s bray alerted her to his approach – and ever after, on her festal day, asses take a holiday and wear ‘necklaces of loaves in memory of his services’.15 Some of these stories were no doubt introduced by Ovid himself, in the interests of variety or for fun; some may already have been, before his day, incorporated into educated Roman speculation (or joking) about the rituals. But either way it is certain that Ovid’s stories do not all date back into the early history of Rome, even if some elements may do. As a source of the religious ideas of his own time Ovid is invaluable; as a source for the remote past, he is hard to trust.

It is not just a question, though, of Ovid being peculiarly unreliable; and the answer does not lie simply in looking for other ancient commentators on the calendar who have not ‘polluted’ their accounts with anachronistic explanations. The fact is that the rituals prescribed by the calendar of festivals were not handed down with their own original ‘official’ myth or explanation permanently attached to them. They were constantly re-interpreted and re-explained by their participants. This process of re-interpretation, found in almost every culture, including our own (the annual British ritual of ‘Bonfire Night’ means something quite different today from three hundred years ago),16 is precisely the strength of any ritual system: it enables rituals that claim to be unchanging to adopt different social meanings as society evolves new needs and new ideas over the course of time; and it means, for example, that a festival originating within a small community whose main interests were farming can still be relevant maybe 600 years later to a cosmopolitan urban culture, as it is gradually (and often imperceptibly to its participants) refocussed onto new concerns and circumstances.17 But at the same time it means that the interpretation of the ‘original’ significance of a festival, especially in a society that has left no written documents, is not just difficult, but close to impossible. The fact that we can trace the same names (Lupercalia, Vinalia etc.) over hundreds of years, or even the fact that the ceremonies may have been carried out in a similar fashion throughout that time, does not allow us to trace back the same significance from the first century B.C. to the seventh.

The calendar is a prime example of how tantalizing much of the evidence for the religion of early Rome is. Again, it is not that there is no evidence at all. Here we have a remarkable survival: fossilized within later traditions of calendar design, traces of a list of festivals whose origins lie centuries earlier; traces, in other words, of an early Roman document itself, not a first-century B.C. reconstruction of early Roman society. The problem is how to interpret such traces, fragmentary and entirely isolated from their original context.

Other documents and direct evidence from the early Republic, and even the regal period, are almost certainly preserved in the scholarly and antiquarian tradition of historical writing at Rome in the late Republic and early empire. For the Romans, the greatest of their antiquarians was the first-century Varro, who compiled a vast encyclopaedia of Roman religion with the express purpose, he said, of preserving the ancient religious traditions that were being forgotten or neglected by his contemporaries. This extraordinary polymath would certainly have been able to consult many documents (inscriptions recording temple foundations, for example, religious regulations, dedications) no longer available to us and he would no doubt have quoted many in his work. It is hard not to regret the loss of Varro and the fact that his religious encyclopaedia survives only in fragments, quoted as brief dictionary entries or in the accounts of later Christian writers who plundered his work and that of other antiquarians solely in order to show how absurd, valueless and obscene was the religion of the classical world that they were seeking to destroy and replace. On the other hand, some of these quotations are quite extensive, and the substance of Varro’s work may also be preserved in many other authors who do not refer to him directly by name. The loss may not, after all, be as great as we imagine.18

Thirty-five books of Livy’s History do, however, survive – out of the original 142, which covered the history of Rome from its origins to the reign of the emperor Augustus. Livy’s History is in many respects preoccupied (as we have already seen) with the issues and concerns of first-century B.C. Rome; and more generally the picture we derive from his writing may be very much an artificial historiographic construction, expressing an ‘official religion which reflected little of the religious life of the community, or perhaps only that of the élite. On the other hand, Livy does claim to know many individual ‘facts’ about religious history going back at least to the early Republic, sometimes even quoting ancient documents or formulae. How accurate can this information have been?

Some of the documents (for example, his quotation of the particular religious formulae used in the declaration of war) are almost certainly fictional reconstructions or inventions, which may have little in common with the formulae actually used in early Rome.19 But many of the other brief records (of vows, special games, the introduction of new cults, innovations in religious procedure, the consultation of religious advisers and so on) are not likely to be inventions. The pieces of information they contain are not obviously part of an ideological story of early religion; and many of them appear (from the form in which they are recorded, or the precise details they record) to preserve material from the early Republic, if not earlier. Perhaps the clearest example of this comes not from Livy himself, but from the elder Pliny. In his Natural History (written in the middle of the first century A.D.), Pliny notes the precise year in which the standard procedure for examining the entrails of sacrificial animals (‘extispicy’) was amended to take account of the heart in addition to other vital organs.20 This information almost certainly comes from some early source: not only does there seem to be no reason for such an odd piece of ‘information’ to have been invented, but it is also dated in a unique way – which it is very unlikely that Pliny would have made up. The date of the change is given by the year of the reign of the rex sacrorum, that is the ‘king of rites’ or the priest who carried on the king’s religious duties when kingship itself was abolished; this makes no sense unless this system of dating continued in use in priestly records even though it was abandoned for every other purpose when the Republic was founded; if so Pliny (or his source) must have found this ‘nugget’ in some priestly context.

This gives us one hint on how information of this type might have been preserved and transmitted from the earliest period of Rome’s history to the time when the literary tradition of history writing started. Priests in Rome had traditionally kept records to which they could refer to establish points of law; and (as we shall discuss later in this chapter) the pontifices, in particular, were said to have kept an annual record of events, including, but not confined to, the sphere of religion. Writing down and recording was a significant part of the function of priests.21 It is certainly possible that Livy, Pliny and other writers (or the sources on which they drew; there was after all a two-hundred year tradition of history writing at Rome before Livy, mostly lost to us) had access to priestly records with information stretching back centuries. If so (and many modern historians have hoped or assumed that this was the case) then many of their points of fact about religious changes, decisions or developments in early Rome may be more authentic than we would otherwise imagine.

On the other hand, priestly record keeping had (for our purposes) its own limitations. Only changes, not continuities, would have been recorded; and then, presumably, only changes of a particular kind, the ones the priestly authorities noticed and chose to record in their collegiate books. Many other changes will have happened over the course of years without record – through mistakes, neglect, forgetfulness, unobserved social evolution, the unconscious re-building of outmoded conceptions; many of these would never even have been noticed, let alone written down. So even if we could gather together these occasional recorded facts (the foundation of a new temple, the introduction of a new god) and arrange them into some sort of chronological account, it would make a very strange sort of ‘history’. A history of religion is, after all, more than a series of religious decisions or changes. Once again, it is not a question of having no ‘authentic’ information stretching back to the early period; it is a question of having very little context and background against which to interpret the pieces of information that we have.22

If evidence of this kind offers only glimpses of the earliest religious history of Rome, modern scholars have tried to construct a broader view by setting the evidence against different theories (or sometimes just different a priori assumptions) about the character of early religions in general and early Roman religion in particular, and about how such religions develop.23 These theories vary considerably in detail, but they have over all a similar structure and deploy similar methods. First, the earliest Roman religion is uncovered by stripping away all the ‘foreign’, non-Roman elements that are clearly visible in the religion of (say) the late Republic. Even in that period, some characteristics of Roman religion must strike us as quite distinct from the traditions of the Greeks, Etruscans and even of other Italic peoples that we know of. The Roman gods, for example, even the greatest of them, seem not to have had a marked personal development and character; while a whole range of ‘lesser’ gods are attested who were essentially a divine aspect of some natural, social or agricultural process (such as Vervactor, the god of ‘turning over fallow land’, or Imporcitor, the god of ‘ploughing with wide furrows’24); there were few ‘native’ myths attaching even to the most prominent rituals; the system offered no eschatology, no explanation of creation or man’s relation to it; there was no tradition of prophets or holy men; a surviving fragment of Varro’s encyclopaedia of religion even reports that the earliest Romans, for 170 years after the foundation of their city, had no representations of their gods.25 These characteristics have been interpreted in all kinds of different ways. Some modern scholars have seen them as simple primitive piety – which seems, in fact, to have been the line taken by Varro (who claimed that the worship of the gods would have been more reverently performed, if the Romans had continued to avoid divine images). But at the same time, the temptation is seldom resisted to summarize all this by saying that the Romans were artless, unimaginative and supremely practical folk, and hence that everything involving art, literary imagination, philosophic awareness or spirituality had to be borrowed from outside – whether from Greeks, Etruscans or other Italians.26

The second strand of the argument treats the ‘development’ of Roman religion as effectively a ‘deterioration’: the ‘healthy’ period of ‘true’ Roman religion is retrojected into the remote past; the late Republic is treated as a period when religion was virtually dead; the early Republic then provides a transitional period in which the forces of deterioration gathered strength, while the simplicities of the early native religious experience were progressively lost. Among the mechanisms of this deterioration that have been proposed are: (a) the contamination of the native tradition by foreign, especially Greek, influences; (b) the sterilization of true religiosity by the growth of excessive priestly ritualism; (c) the alienation of an increasingly sophisticated urban population from a religious tradition that had once been a religion of the farm and countryside and failed to evolve. In the case of (c), it is hard to believe that any ancient city lost its involvement with, and dependence on, the seasonal cycle of the agricultural year, let alone the relatively small-town Rome of the third century B.C. The other two suggestions are harder to refute, but no less arbitrary. A different approach will be taken in what follows, but we can point out at once that neither foreign influences nor priestly ritualism necessarily cause the deterioration of a religious system; and we will argue too (especially in chapter 3) that it is much harder than many modern writers have assumed to decide what is to count as the ‘decline’ of a religion.27

But there is an even more fundamental challenge to this simple scheme of development. Recent work, particularly in archaeology, has cast doubt on the idea of an early, uncontaminated, native strand of genuine Roman religion; and it has suggested that, rather than seeing pure Roman traditions gradually polluted from outside, Roman religion was an amalgam of different traditions from at least as far back as we can hope to go. Leaving aside its mythical prehistory, Roman religion was always already multicultural.

Archaeological evidence from the sixth century B.C., for example, has shown that (whatever the political relations of Rome and Etruria may have been)28 in cultural and religious terms Rome was part of a civilization dominated by Etruscans and receptive to the influence of Greeks and possibly of Carthaginians too. A dedication to the divine twins Castor and Pollux found at Lavinium, which uses a version of their Greek title ‘Dioskouroi’, shows unmistakably that we have to reckon with Greek contacts;29 some of these contacts may have been mediated through the Etruscans, others coming directly from Greece itself – while it is perfectly possible that there were connections too with Greek settlements in South Italy. Even more striking Greek elements have been revealed by a recent study of the earliest levels of the Roman forum. From this it has become possible to identify almost certainly the early sanctuary of the god Vulcan (the Volcanal); and in the votive deposit from this sanctuary, dating from the second quarter of the sixth century B.C., was an Athenian black-figure vase with a representation of the Greek god Hephaestus. In other words, there was already in the early sixth century some identification of Roman Vulcan and the Greek Hephaestus, and the Greek image of the god had already penetrated to his holy place in the centre of Rome.30 In a different way, the discovery of a religious phenomenon widespread throughout central Italy has similar disturbing implications for the conventional image of early Roman religion. Several sites have now produced substantial deposits of votive offerings dating back to at least the fourth century B.C., which consist primarily of small terracotta models of parts of the human body (Fig 1.2);31 this suggests that there were a number of sanctuaries soon after the beginning of the Republic to which individuals went when seeking cures for their diseases: at these sanctuaries they presumably dedicated terracottas of the afflicted part. This implies not only a cult not mentioned in any surviving ancient account, but also a type of religiosity which the accepted model of early Roman religion seems to exclude: for it implies that individuals turned to the gods directly in search of support with their everyday problems of health and disease. On the accepted model, they would have looked for and expected no such help, practical or spiritual. Another study has suggested that inscriptions discovered at Tor Tignosa near to Lavinium come from a cult in which incubation was practised: that is to say, people came to sleep in the sanctuary in the hope of receiving advice or revelation from the deity in a dream.32 In this case both Virgil and Ovid describe the use of such a technique in early – or rather mythical – Italy;33 but their evidence was always thought suspect on the grounds that divine communication through dreams was a characteristically Greek practice, not compatible with the religious life of the early Romans and found in Italy only later when specifically Greek incubation-cults were introduced.34

Fig. 1.2 Votive terracottas from Ponte di Nona, 15km to the east of Rome. They were made in the third or second centuries B.C. for a sanctuary on the site abandoned in the late Republic, but were buried together during building operations in the fifth century A.D. This particular deposit included a majority of feet and eyes, perhaps reflecting the sanctuary’s curative specialities. (Foot, length 0.3m.; eyes, width 0.05m.)

This much more complex picture of early Roman religion undermines some of those narrative accounts of Roman religious history that have been most influential over the last hundred years. So, for example, it is hard to sustain the once popular and powerful idea – influenced by early twentieth century anthropology – that Roman religion gradually evolved from a primitive phase of ‘animism’ (where divine power was spread widely through all kinds of natural phenomena) to a stage where it had developed ‘proper’ gods and goddesses;35 if we abandon the idea of an original core of essential Romanness, then we must abandon also any attempt to discover a single linear progression in the history of Roman religion. In this spirit, rather than trying to extract a small kernel of primitive ‘Roman’ characteristics from the varied evidence of the first century B.C., a different strategy has been to define the central characteristics of early Roman religion comparatively – that is by comparison with societies with a similar history. In the rest of this section, we shall look in greater detail at the most influential of these comparative approaches, its main claims and its problems.

The lifetime’s project of the historian Georges Dumézil (1898–1986) was to combine evidence from many different Indo-European societies and traditions in order to discover the internal structure of the systems of mythology that were, he claimed, the common inheritance of all these peoples. His theories were based on the much broader and older idea that the societies which speak languages belonging to the ‘Indo-European’ family (including Greek, Latin, most of the languages of modern Europe, as well as Sanskrit, the old language of North India, and Old Persian) shared more than language; that they had, albeit in the far distant past, a common social and cultural origin.

Dumézil believed that the mythological structure of the Romans and of other Indo-Europeans was derived ultimately from the social divisions of the original Indo-European people themselves, and that these divisions gave rise to a ‘tri-functional ideology’ – which caused all deities, myths and related human activities to fall into three distinct categories: 1. Religion and Law; 2. War; 3. Production, especially agricultural production. This was an enormously ambitious claim, and at first Dumézil’s theories drew very little acceptance. But in time he convinced some other scholars that this tri-partite structure could be detected both in the most archaic Roman religious institutions and in the mythology of the kings, especially in that of the first four.36 On his view, Romulus and Numa were the symbols of the first function (one a ruler, one a priest); Tullus Hostilius, the third king, and Ancus Marcius, his successor, represented the second and third functions respectively (the inventors of war and of peaceful production).37

In Dumézil’s perspective, the earliest gods also reflected these three functions – as gods of law and authority, gods of war, gods of production and agriculture. The familiar deities of the Capitoline triad (Jupiter, Juno and Minerva) failed to fit the model; but he found his three functions in the gods of the ‘old triad’ –Jupiter, Mars, Quirinus. Although this group was of no particular prominence through most of the history of Roman religion, they were the gods to whom the three important priests of early Rome (the flamen Dialis (of Jupiter), flamen Martialis and flamen Quirinalis) were dedicated – and Dumézil found other traces of evidence to suggest that these three had preceded the Capitoline deities as the central gods of the Roman pantheon. They appeared to fit his three functions perfectly: Jupiter as the king of the gods; Mars the war-god; Quirinus the god of the ordinary citizens, the farmers.38

Dumézil’s work has prompted much useful discussion about individual festivals or areas of worship at Rome.39 There are, however, several major problems with his Indo-European scheme overall. If Dumézil were right, that would mean (quite implausibly) that early Roman religion and myth encoded a social organization divided between kings, warriors and producers fundamentally opposed to the ‘actual’ social organization of republican Rome (even probably regal Rome) itself. For everything we know about early Roman society specifically excludes a division of functions according to Dumézil’s model. It was, in fact, one of the defining characteristics of republican Rome (and a principle on which many of its political institutions were based) that the warriors were the peasants, and that the voters were ‘warrior-peasants’; not that the warriors and the peasant agriculturalists were separate groups with a separate position in society and separate interests as Dumézil’s mythic scheme demands. In order to follow Dumézil, one would need to accept not only that the religious and mythic life of a primitive community could be organized differently from its social life, but that the two could be glaringly incompatible.

This point is reinforced by the character of the gods in the old triad. Even supposing Dumézil were right about their very earliest significance, all three soon developed into the supposed domains of at least one and possibly both of the others. Jupiter, the god of the highest city authority, also received the war-vows of the departing general and provided the centre of the triumphal procession on his return; but he also presided over the harvest in the vineyards.40 Mars, the god of war, protected the crops and was hence very prominent in the prayers and rituals of the farmer.41 Quirinus, who was anyway far less prominent in republican times, was certainly connected with the mass of the population and with production, but also appears as a war god like Mars; while his appearance as the divine aspect of Romulus puts him also into the first (kingly) function.42 Outside this triad even apparently ancient deities do not readily fall into one of Dumézil’s three categories. Juno, for example, who is sometimes very much a political goddess in Rome and the surrounding area, is also a warrior goddess and the goddess of women and childbirth. It is well established in studies of Greek polytheism that the spheres of interest of individual deities within the pantheon were more complicated than a one to one correlation (Venus/Aphrodite = goddess of love) would suggest; and that the spheres of deities were shifting, multiple and often defined not in isolation, but in a series of relationships with other gods and goddesses. It may well be, in other words, that Dumézil’s attempt to pin down particular divine functions so precisely was itself misconceived.43 But, even if that were not the case, it is hard to find any of the main deities at Rome that does not cross some or all of Dumézil’s most important boundaries.

Dumézil’s theorizing shows us once more how powerful in accounts of early Roman religion is the mystique of origins and schemata. But in the end we are confronted with an imaginary Roman tradition of the history of their early religion; with individual pieces of information preserved in later writing either randomly or (in the case of priestly record keeping) by a process of selection we can hardly guess at; with glimpses of different kinds of information and different kinds of religious experience; and with a variety of theories that attempt to explain the information we have. This is both too little and too much. Probably most important for our understanding of Roman religion is the mythic tradition, with its tales of Romulus and Numa, the origins of customs and rituals, that was one of the most powerful ways of thinking about religion that the Romans devised. But, as we have seen, it was not a ‘history’ of religion in our terms.

We have adopted a quite different approach for exploring the history of Roman religion. We have not followed the method, so often tried before, of seeking the ‘real’ religion of Rome by stripping away the allegedly later accretions, but rather have used precisely the opposite method. The next three sections (2–5) of this chapter analyse the central structural characteristics of Roman republican religion, very largely based on evidence that refers to the last three centuries of that period. In doing so we have not restricted ourselves to the contemporary first-century B.C. material of Cicero and Varro, but have drawn on the account of Livy (writing after the end of the Republic) for the third and second centuries B.C. We do this on the principle that the structural features of any religion change only slowly, and that the third-century system as described by Livy is recognizably similar to the first-century world we know from contemporary sources. In other words we claim that (for all the early imperial interpretation he cast on his material) Livy understood well enough the functioning of the republican religious system to represent it in its broad outlines.

We also accept, however, that the further back in time we attempt to project this picture, the more risk there is that it will be seriously misleading. It is virtually certain that some of the features of republican religion that we identify (for example, some of the priesthoods and priestly colleges) stretched back, in some form, into the earliest period of Rome’s history; and that more could be traced back at least to the very earliest period of the Republic itself. On the other hand it is also certain that an overall picture valid for the third century B.C. would be quite invalid for the period of the kings, and in some respects for the early Republic too. There were major breaks in the history of Rome not only at the time of the ‘fall of the kings’ (traditionally put in the late sixth century B.C.) but also in the last decades of the fourth century, when we can detect radical changes in the nature of the Roman state. It may well be, in fact, that the developed institutions of the Republic (which we and the Romans tend to push back to the years immediately following the end of the monarchy) largely took their distinctive shape at that time.

The risks of assuming too much continuity (religious and political) from the very beginning of the Republic can be well illustrated by considering the tradition about patricians and plebeians. In the late Republic the patricians were a closed caste of ancient clans, while the plebeians were all the other Romans. At that date the patricians had very few political privileges, but some particular priesthoods were restricted to them alone; and in chapter two we shall see how the division applied in the main priestly colleges where places had to be held in certain numbers by patricians and plebeians. It is certainly the case that conflict between patricians and plebeians (and the plebeians’ claim to a share in the privileges of patricians) was a major feature of the late fifth and early fourth centuries B.C. And both ancient and modern historians have tended to assume that the distinction applied in an even stronger form in earlier periods: that in the first years of the Republic and even under the monarchy, all the rich, noble, office-holding families were patrician; all the others plebeian. In fact this assumption is very flimsy: it is very possible that there were more than two status groups in the fifth century B.C.; and quite certain that power was not limited to patricians – for example the recorded names of some of the early magistrates are not patrician; and in fact the kings all have non-patrician names. It seems fairly clear that there were radical changes in Roman society between 500 and 300 B.C., marked in part by the increasing rigidity of the patrician/plebeian distinction; we must reckon with the possibility that religious authority changed radically in its character too.44

Our argument is that by starting with the developed republican structure we are providing an introduction to the ideas and institutions that will recur throughout this book. At the same time, we are defining a framework within (and against) which to interpret the evidence about earlier Rome, by beginning to assess how similar or different the earliest conditions may have been. Accordingly sections 5 and 6 of this chapter will return to consider the transition from monarchy to Republic, and the character of religious change in the early republican years.

2. The priests and religious authority

In the late Republic, one of the most distinctive features of the Roman religious system was its priestly organization, consisting of a number of ‘colleges’ and other small groups of priests, each with a particular area of religious duty or expertise. Two underlying principles stand out: first, the sharp differentiation of priestly tasks (priests were specialists, carrying out the particular responsibilities assigned to their college or group); second, collegiality (priests did not operate as individuals, but as a part or as a representative of the group – there was no specific ritual programme for any individual, while any member of the college could properly perform the rituals). This is the basic structure that Roman writers ascribed (mythically) to Numa; and they assumed that it operated in the early republican period too – where, we are told, there were three major colleges of priests: the pontiffs (pontifices) the augurs (augures) and the ‘two men for sacred actions’ (duoviri, later increased to the ‘ten men’ decemviri sacris faciundis);45 a fourth college, the fetials (fetiales), was perhaps of comparable importance. These four colleges, whose members normally held office for life, were consulted as experts by the senate within their own area of responsibility, and on those issues the senate would defer to their authority. Other groups of priests had ritual duties, on particular occasions or in relation to particular cults, but were not, so far as we know, officially consulted on points of religious law.46

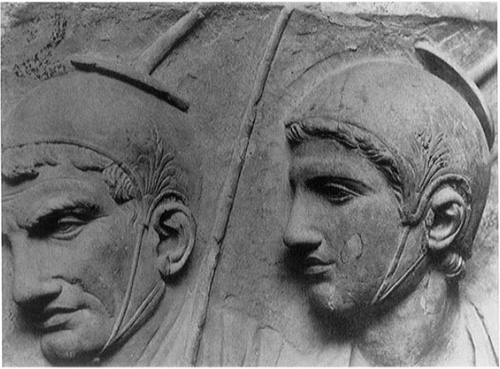

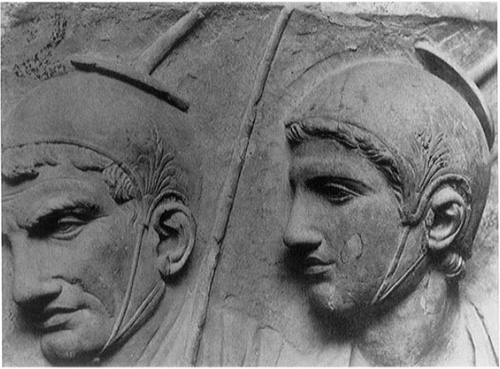

Fig. 1.3 Heads of two flamines, from the south frieze of the Ara Pacis, Rome (4.3); their religious importance is marked by their leading the procession of priests (behind Augustus as pontifex maximus, but ahead of all the other priests) and they are distinguished by their head-gear, a bonnet with a projecting baton of olive-wood (apex). (Height, c. 0.2m.)

This general view of the colleges needs some qualification in particular cases. First, the college of pontifices had a far more complex structure than the others. They had a recognized leader (the pontifex maximus), who, from the third century B.C. onwards, was elected publicly from the existing pontifices, not, as before, chosen by his colleagues. The college also contained a number of other priestly officials: as full members, the rex sacrorum and the flamines of the gods Jupiter, Mars and Quirinus; and in some sense associated with the college, even if not ‘members’, the Vestal Virgins, the scribes of the pontifices, and the twelve lesser flamines.47 The fifteen flamines, through the very nature of their priesthood, suggest a different principle of religious organization: each had his own god to whom he was devoted; he had his ritual programme which he himself, individually, had to fulfil; and he was to a greater or lesser degree restricted in his movements and behaviour. It is a reasonable guess that this represents a very old system of priestly office holding; that the flamines had once been independent of the colleges, but were later subordinated to the pontifices.48

The haruspices (diviners) were a second set of priests whose activity diverged from the standard collegiate pattern. One of their main areas of expertise was the interpretation of prodigies. Prodigies were events, reported from Rome or in its territories, which the Romans regarded as ‘unnatural’ and took as dangerous signs or warnings – monstrous births, rains of blood, even strokes of lightning. These had to be considered by the senate, who took priestly advice and recommended action to avert the danger.49 The history of this priestly group is complicated by the fact that ancient writers refer to ‘haruspices’ fulfilling a wide variety of functions quite apart from the interpretation of prodigies; and it is far from clear whether we are dealing with a variety of religious officials (all going under the same name) or a single category.50 It is clear, however, that there was no such thing as a haruspical college until the end of the Republic51 – although this did not prevent their being consulted by the senate much earlier. In fact, some of the reports of such consultations in the early Republic describe them as being specifically summoned to Rome from Etruria to give advice on prodigies.52 If those reports imply that the haruspices were literally foreigners, outside experts in a particularly Etruscan variety of religious interpretation, that would of course explain their lack of a Roman-style collegiate organization. But so also would the possibility (as may well have been the case later) that these officials were not literally foreign themselves, but were seen as ‘foreign’ in the sense that they were the representatives of a foreign religious skill. For even if modern archaeology has increasingly come to argue that Etruria and Rome were part of a shared common culture in the sixth century B.C. and even later, Roman imagination in the centuries that followed did not see it that way: for them Etruscan religious traditions were different and alien, and sometimes powerful for that very reason. In this case, a different priestly organization might have been one way of defining and marking as different the religious traditions those priests represented. The ‘Etruscan-ness’ of the haruspices might, in other words, count as the first of several instances we shall discuss in this book where Roman religion constructively used the idea of foreignness as a way of differentiating various sorts of religious power, skill and authority; the first instance of ‘foreignness’ as a religious metaphor, reflected here in priestly organization.53

These various priestly groups at Rome were not ranked in a strict hierarchy of religious authority. The basic rule, even for those that we think of as the more ‘important’ colleges, was that each group had their own area of concern and of expertise, within which sphere the others never interfered. The pontifex maximus had some limited disciplinary powers, but mostly in relation to the priests and priestesses of his own college – the Vestals, the rex and the flamines; in the Republic he had no authority over the whole of the priestly structure of the city, let alone control more generally over the relations between the Romans and their gods.54 But this raises the question of where such authority did lie, and how priestly power was defined and exercised. In the rest of this section we will show that the capacity for religious action and for religious decision-making was widely diffused among different Roman authorities (not only priests); that there was no single central power that controlled (or even claimed to control) Roman relations with their gods; and that the position of the priests can only be understood in the context of the rest of the constitutional and political system of the city. The first step will be to examine the work of the major colleges.

Fig. 1.4 Bronze mirror from Vulci, late fourth B.C., with the name Kalchas inscribed next to the figure. Kalchas is the Greek prophet of the Iliad, but is here shown as an Etruscan diviner and – surprisingly -winged: he examines a liver (see 7.4b); other entrails are on the altar. The iconography suggests that Etruscans, as well as Romans, were using foreignness to define their own religious traditions. (Height, 0.18m.)

The augures were the experts in a variety of techniques used to establish the will of the gods, known as ‘taking of the auspices’ (auspicia).55 The best-known and probably the earliest of these techniques involved observing the flight and activity of particular species of birds, but the augurs also dealt with the interpretation of thunder and lightning, the behaviour of certain animals and so on (one way of discovering divine will was by feeding some special sacred chickens and seeing if they would eat).56 They were not, however, concerned with every kind of communication with the gods: the augurs were not consulted about the interpretation of prodigies; and seem to have had nothing at all to do with the reading of entrails at sacrifices, which was the business of officials known (again) as haruspices. The augures did not themselves normally take the auspices. It was usually the city magistrates who carried out the ceremonies and the observations required in their roles as war-leaders or as political or legal officials; and they passed on the right to take the auspices year by year to their successors.57 In normal cases, an augur would be present as adviser, perhaps as witness; and after the event, the augural college would be the source of judgement on the legality of what had been done or not done.

These procedures were integrally bound up with the definition of religious boundaries and religious space – one of the most technical and complex areas of Roman religious ‘science’. Occasionally signs from the gods might come unasked, in any place and on any occasion;58 but normally the human magistrate would initiate the communication, specifically seeking the view of the gods on a particular course of action or a particular question. On these occasions the place of consultation and the direction from which the sign came were crucially important. The taker of the auspices defined a templum in the heavens, a rectangle in which he specified left, right, front and back; the meaning of the sign depended on its spatial relationship to these defined points. These celestial rectangles had a series of equivalents on earth to which the same term was applied. Confusingly, a ‘temple’ in our sense of the word might or might not be a templum in this sense: the ‘temple’ of Vesta, for instance, was strictly speaking an aedes (a ‘building’, a house for the deity) not a templum; while some places that we would never think to call ‘temples’ were templa in this technical sense –such as the senate-house, the comitium (the open assembly area in the forum in front of the senate house), and the augurs’ own centre for taking auspices, the auguraculum.59 All these earthly temples were ‘inaugurated’ by the augurs, after which they were said (obscurely to us and probably to many Romans too) to have been ‘defined and freed’ (effatum et liberatum).

Augural expertise, therefore, concerned not just the interpretation of signs but the demarcation of religious space and its boundaries. They operated as a system of categorizing space both within the city and between the outside world and Rome itself; this categorization in turn corresponded to the different types of auspices. One of their most important lines of division was the pomerium, the sacred and augural boundary of the city; it was only within this boundary that the ‘urban auspices’ (auspicia urbana) were valid; and magistrates had to be careful to take the auspices again if they crossed the pomerium in order to re-establish correct relations with the gods.60

The realm of the augures provides one of the clearest examples of the convergence of the sacred and the political. All public action in Rome took place within space and according to rituals falling within the province of the augurs. The passing of laws, the holding of elections, discussion in the senate – all took place within spaces defined by the application of augural ritual (the senate, for example, could only meet in a templum); each individual meeting was preceded by the taking of the auspices by the magistrates responsible. It followed that the validity of public decisions was seen as dependent on the correct performance of the rituals and on the application of a network of religious rules, whose maintenance was the augurs’ concern; and in the constitutional crises of the late republican period, their right to examine whether a religious fault (vitium) had occurred in any proceeding of the assemblies gave them a critical role in public controversies. All these augural processes were central to the relations between the city and the gods, and to the legitimacy of public transactions. This is why the augurs were so important politically.

We get a glimpse, however, of a strikingly different image of the augurs in one of the stories told about Rome’s earliest history. If the records of augural activity through the Republic stress the technical, sometimes legalistic, skill of the augurs, embedded at the heart of the political process, a story told by Livy of the early augur Attus Navius and his conflict with King Tarquin presents the priest as a miracle worker in conflict with the political power of the state (here represented by the monarch).61 Challenging the power of the king, so the story goes, Navius claimed that he would carry out whatever Tarquin had in his mind; Tarquin triumphantly retorted that he was thinking of cutting a whetstone in half with a razor – which Navius promptly and miraculously did. A commemorative statue of Navius apparently stood in the forum (in the centre of Roman political and religious space) through most of the Republic.62 There are many ways to interpret this story and the vested interests that may have lain behind its telling (that it is, for example, a reflection of later conflicts between augurs and a dominant political group; or that it is a surviving hint of a very different type of early priestly activity; and so on); but on almost any interpretation, it is a strong reminder that recorded details of priestly action do not account for the whole of the priestly story; that the historical tradition (in our sense) has its limitations. Priests had a role in Roman myth and imagination, which also determined the way they were seen and operated in the city. In this case, it is not just a question of stories told, or read in Livy. When the republican augur went about his priestly business in the Forum, he did so under the shadow of a statue of his mythical, miracle-working predecessor.

The pontifices had a wider range of functions and responsibilities than the augurs, less easily defined in simple terms. As a starting point, we might say that their religious duties covered everything that did not fall specifically within the activities of the augures, the fetiales and the duoviri. Like these other colleges, they were treated as experts on problems of sacred law and procedure within their province – such matters as the games, sacrifices and vows, the sacra connected with Vesta and the Vestals, tombs and burial law, the inheritance of sacred obligations. Their powers of adjudication do not seem at first sight to lie in areas as politically charged as those dealt with by the augurs; but these issues were, as we shall see, of central importance to public and private life at Rome and the pontifices continued throughout the Republic to be as distinguished as the augures in membership.63

The pontifices were unlike other priestly colleges in several respects. We have already seen that their collegiate structure was rather different from the others; they also differed in having functions that took them right outside the limits of religious action – ‘religious’, that is, in our sense. At its grandest, the role envisaged for them by Roman writers is as the repository of all law, human or divine; Livy suggests that, down to 304 B.C., the formulae, the precise form of words without which no legal action could begin, were secrets known only to the pontifices.64 The significance and history of their legal role is a difficult problem. It is certainly possible that there was a specific ‘religious’ origin here; that pontifices were the earliest source of legal advice for the citizen, essentially on matters of religious procedure, such as the rules of burial – but that, since religious and non-religious law overlapped extensively, the range of advice they offered and the area of their expertise gradually widened.65 More certainly, the pontificeswere responsible for the calendar; for the supervision of adoptions and some other matters of family law; and for the keeping of an annual record of events.

Their control of the calendar goes beyond interest merely in the annual festivals, although that would have been part of their task; the calendar also determined the character of individual days – whether the courts could sit, whether the senate or the comitia (assemblies) could meet. The priests were responsible, amongst other things, for ‘intercalation’. All systems of timekeeping face the problem of keeping their yearly cycle in step with the 365 days 5 hours 48 minutes 46.43 seconds (more or less) that it actually takes for the earth to circle the sun. Modern Western calendars solve this problem by adding an extra day to their 365 day calendar once every four years (in a leap year).66 The Roman republican calendar of 355 days needed to add (‘intercalate’) a whole month at intervals that were determined by the pontifices. The college also fixed the celebration of some of the important festivals which had no set date; and the sacred king (rex sacrorum), a member of the college, had the task of announcing the beginning of each month (perhaps a survival from an earlier form of the calendar when months began when the new moon was observed). The everyday organization of public time was pontifical business.67

The pontifices’ concern with adoptions, wills and inheritances inevitably involved some elements of strictly religious interest – since each of these areas affected a family’s religious obligations (sacra familiaria) and raised problems about who would maintain them into the next generation. The college’s duties in this area would very likely have drawn them into wider issues of the continuity of family traditions and the control of property, where conflicts would have demanded adjudication between families or between clans (gentes).68 The most (to us) unexpected of pontifical duties was, perhaps, the recording of events. A fragment preserved from the history of Cato the Elder (written in the first half of the second century B.C.) states that they were responsible at that time for ‘publishing’ the great events of the day on a whitened board, displayed in public;69 these public reports, according to other writers, formed the basis of a permanent annual record, known to Cicero and, at least allegedly, going back to the earliest times.70 We do not know exactly what this record contained, or when it was first kept. Roman writers seem to refer to it, however, as one of the college’s traditional duties.

We are faced then with a range of what we should call ‘secular’ functions, as well as the ‘religious’ ones. One possibility is that the pontiffs were not an exclusively religious body in early Rome; but, rather than imagine that the ‘priests’ were not wholly ‘religious’, it is more helpful to think that what counted as ‘religion’ was differently defined. In almost all cultures the boundary between what is sacred and what is secular is contested and unstable. One of the themes underlying the chapters of this book will, precisely, be the gradual differentiation of these two spheres and the development, for example, of a religious professionalism at Rome that tried to distinguish itself sharply from other areas of human activity. But for the pontiffs of the very early period, there is no reason to assume that some of their tasks seemed more or less ‘religious’ than others, more or less ‘priestly business’.

What, however, of the apparently wide diffusion of their responsibilities, from burial to record-keeping, and beyond? Is there any possible coherence in these different tasks? A central focus of interest? Of course, coherence very much depends on who is searching for it. Different pontifices, different Romans, at different periods may have made sense of their combined responsibilities in quite different ways. But one guess is that there was a closer connection than we have so far stressed between their interest in family continuity and their practice of record-keeping; and that many of their functions shared a concern with the preservation, from past time to future, of status and rights within families, within gentes and within the community as a whole – and so also with the transmission of ancestral rites into the future. This gave the calendar too a central role, with its organization of the year’s time into its destined functions, and its emphasis on past ritual practice as the model for the future. The pontifices, in short, linked the past with the future by law, remembrance and recording.

Two other colleges have duties which bring them close to the central workings of the city. The fetials (fetiales) controlled and performed the rituals through which alone a war could be started properly; to ensure that the war should both be, and be seen to be, a ‘just war’ (bellum iustum).71 The most detailed accounts of their activities date from a period when much of their ritual must have been modified or discontinued; but, if Livy is to be believed at all,72 they were in early times responsible both for ritual action and for what we should call diplomatic action – conveying messages and demanding reparations. Later on, they could still be called upon by the senate, to give their view on the correct procedures for the declaration of hostilities.73 The duoviri sacris faciundis were the guardians of the Sibylline Books.74 The Books themselves will be discussed in a later section,75 but it is clear enough that the prophetic verses which they contained, and which the college kept and consulted on the senate’s instructions, were believed to be of great antiquity. When prodigies were reported, one of the options before the senate, instead of consulting the haruspices, was to seek recommendations from the Books. These recommendations repeatedly led to the foundation or introduction of foreign cults, normally Greek and celebrated according to the so-called ‘Greek rite’ (Graeco ritu).76 In these cases the priests may have had some continuing responsibility for the new cult; but there is no evidence that the duoviri exercised any general supervision over Greek cults – to match the supervision that the pontifices came to exercise over Roman ones. Both fetiales and duoviri kept within closely defined areas of action.

All the priests we have looked at exercised their authority within a set of procedures that involved non-priests as well as priests, the ‘political’ as well as the ‘religious’ institutions of the city. Priests themselves were not part of an independent or self-sufficient religious structure; nor do they seem ever to have formed a separate caste, or to have acted as a group of specialist professionals, defined by their priestly role. From the third century onwards, the historical record preserves the names of a good proportion of augures and pontifices; from this it is clear that priests were drawn from among the leading senators – that is, they were the same men who dominated politics and the law, fought the battles, celebrated triumphs and made great fortunes on overseas commands.77 Although they were in principle the guardians of religious, even of secret, lore, they were not specially trained or selected on any criterion other than family or political status. The holders of the less prominent priesthoods (such as the Salii or Arval Brothers) are less well known to us; but there is little, if any, sign that they were chosen as religious specialists. That is not to say that priests, or some of them, did not become experts in the traditions and records of their colleges; some of them vaunted the technicalities of their discipline and by the late Republic (as we shall see in Chapter 3) proclaimed themselves expert in the history, procedures and religious law of their colleges. But they were always (and arguably by definition) men with a bigger stake in Rome than narrowly ‘religious’ expertise. Cicero regarded this situation as one of the characteristic and important features of the tradition of Rome and as a source of special strength: that (as he put it) ‘worship of the gods and the highest interests of the state were in the hands of the same men.’78

There is no doubt that by the middle Republic, the priest-politician was an established figure; whether this situation goes right back to the beginnings of the Republic must be more open to debate – though it is usually assumed that it does. The names of some very early priests of the Republic are handed down in the historical tradition; but we cannot be certain that these names are accurately recorded, let alone whether the men concerned were consuls, or other leading magistrates, as well. (It is only later that we can make such confident identifications of individuals.) In some particular respects, the early republican situation must have been different from the later one: the number of priests in the major colleges was far smaller – two or three, as compared to eight or nine after 300 B.C.; and again, they were almost certainly all members of patrician families – plebeians seem to have become members of the duoviri when they were increased to ten in 367 B.C., and of the pontifices and augures only in 300 B.C.79

But might there have been an entirely different model of priesthood in the earliest Republic (and so also in the regal period)? Might there have been an earlier pattern of office-holding which sharply divided religious from political duties? Even in the later period, some priests were prevented by traditional rules from entering other areas of public life. The sacred king (rex sacrorum) was prevented from holding any office; but – insofar as he was thought to have taken over the religious functions of the deposed king – he is a very special case (to which we shall return in Section 5 of this chapter). The major flamines were sometimes prevented by their duties or by the regulations of their priesthoods from holding or exercising all the duties of magistrates; the flamen Dialis, for example, was forbidden by these rules to be absent from his own bed for more than two consecutive nights – so obviously could not command an army on campaign.80 Such restrictions were, step by step, relaxed in the later Republic, until the flamines came to play the normal role of an aristocrat in public life. One speculation is that all the other priests too had originally been excluded from public life and from warfare; but that they had followed the same route as the flamines (towards a mixed, religious-political career) at a much earlier date. On this view, the very early colleges would have represented much more specialized religious institutions; but as time went on the priestly offices (which unlike the short-term elected magistracies gave their holder a public position for life) might have become tempting prizes for the aristocratic leaders of the day – who gradually brought priesthoods within the sphere of a political career.

It would be difficult to disprove this theory; but on balance the view that the priestly colleges had always been part of political life seems more likely to be right. The fundamental difference between the colleges of priests and the flamines might not, in any case, be best defined by their political activity. The crucial distinction lies rather in their numbers. The flamines, as we have seen, essentially acted as individuals: the flamen Dialis, especially, had a ritual programme that only he could perform – so rules to keep him in the city had a particular point (quite apart from preventing a military or political career). It is a central characteristic of the augures and the pontifices, on the other hand, that they were full colleagues – one could always act instead of another, so that limitations on their movements as individuals would never have been so necessary. If the flamines represent (as they most likely do) some very early pattern of priestly office-holding, that model is distinguished from the later one by its non-collegiality; and the political differences follow from that.81

The authority exercised by the priestly colleges can only be understood in relation to the authority of magistrates and senate. In general, the initiative in religious action lay with the magistrates: it was they who consulted the gods by taking the auspices before meetings or battles; it was they who performed the dedication of temples to the gods; it was they who conducted censuses and the associated ceremonies; it was they who made public vows and held the games or sacrifices needed to fulfil the vows. The priest’s role was to dictate or prescribe the prayers and formulae,82 to offer advice on the procedures or simply to attend. Again, when it came to religious decision-making, it was not with the priests, but with the senate that the effective power of decision lay. To take one example: when a piece of legislation had been passed by the assemblies, but by some questionable procedure, the priests might be asked by the senate to comment on whether a fault (vitium) had taken place; but, subject to the ruling the priests offered, it would be the senate not the priests who would declare the law invalid on religious grounds.83 The procedure for dealing with the annual prodigy-reports suggests much the same relationship; the senate heard the reports and decided to which groups of priests, if any, they should be referred; the priests replied to the senate; the senate ordered the appropriate actions to take place; it was often the magistrates who carried out the ceremonials on the city’s behalf.84

To the modern observer, this procedure makes the priests look rather like a constitutional sub-committee of the senate, but this may be a misleading analogy. It is true that the priests lacked power of action, but on the other hand they were accepted as supreme authorities on the sacred law in their area. Once the senate had consulted them, it seems inconceivable that their advice would have been ignored. And when smaller issues were at stake – such matters as the precise drafting of vows, the right procedure for the consecration of buildings, the control of the calendar – the priests themselves must in practice have had freedom of decision. This follows the pattern we have already seen at several points in this chapter of the close convergence of religion and politics: religious authority in the general sense has to be located in the interaction (according to particular rules and conventions) of magistrates, senate and priests, each college in its own sphere. This implies that, even if they were not sole arbiters, the priests must from a very early period have occupied a critical position in Roman political life, and they must often have been at the centre of controversy over points of ritual and religious procedure with all the political consequences that were entailed. So too, priests must always have been liable to the charge that they were prejudiced in favour of friends and against enemies, that personal or ‘political’ interests were determining their ‘religious’ decisions. The idea that Roman priests had once been quite innocent of politics is only a romanticizing fiction about an archaic society.

3. Gods and goddesses in the life of Rome

The first characteristic of Roman gods and goddesses to strike us must be the wide range of different types, all accepted and worshipped. At one extreme, there were the great gods – Mars, Jupiter, Juno and others – each having a variety of major functions, traditions, stories and myths; some of these stories originated in the Greek world, but when told, re-told and adapted in a Roman context they became a central part of a specifically Roman view of their gods. At the other extreme were deities who performed one narrowly defined function or who appeared only in one narrowly defined ritual context. As we have seen, even parts of a natural or agricultural process (such as ploughing) could have their own presiding deity;85 and the possibility of still further unnamed or unknown gods and goddesses was sometimes admitted and allowed for in ritual formulae: for example, an inscription on a republican altar found on the Palatine hill in Rome runs, ‘To whichever god or goddess sacred, Gaius Sextius Calvinus, praetor, restored it by decree of the senate.’86 The time-honoured way of dealing with this variety in the Romans’ conception of their gods has been to claim that the gods had become ‘frozen’ at different points in their evolution: the functional deities represent an early stage of development, when primitive man worshipped powers residing in the natural world, but did not yet see those powers as ‘personalities’;87 it was only later that the fully-blown, characterful gods and goddesses emerged as well. But whether or not that evolutionary scheme helps to explain the varieties of divine powers we find at Rome, the important fact is that throughout the republican period, all the types seem to have co-existed with no sign of uneasiness – any more than there seems to be any uneasiness about adding to the pantheon by introducing new deities from outside Rome or recognizing new divine powers at home. It may be that the priests did attempt to list and classify the gods; but, if so, this does not seem to have produced any general convergence of the different types or to have produced (as was sometimes the case in the Greek theological tradition) elaborate genealogies of the different ‘generations’ of gods to explain the differences between them.

There are only a few traces of intermediate categories (like ‘heroes’ in Greece) that lay between gods and men. It may be that the dead should be seen as such a category, since they did (as we shall see) receive cult at the festivals of the Parentalia and Lemuria – not as individuals but as a generalized group, under the title of the di Manes or divi parentes (literally, ‘the gods Manes’ or ‘the deified ancestors’).88 And, with the exception of the founders – Aeneas, Romulus and perhaps Latinus (the mythical king of the Latins) – men did not become gods, either when alive or after death;89 even these three exceptions are equivocal, because it is not clear how far they themselves became gods, or how far they became identified with gods which already existed (Aeneas with Indiges, Romulus with Quirinus, Latinus with Jupiter Latiaris).90 Dramatic interaction, however, between humans and gods did occasionally take place: Mars had sexual intercourse with the virgin Rhea Silvia and so begot Romulus; Numa negotiated banteringly with Jupiter and slept with the nymph Egeria; Faunus or Inuus seized and raped women in the wild woods; Castor and Pollux appeared in moments of peril.91 But these mythical or exceptional transactions apart, Roman writers represent communication between men and gods primarily through the medium of ritualized exchange and the interpretation of signs – not through intervention, inspiration or incubation. We have already seen that evidence from archaeology can suggest a rather wider picture;92 but for most of this section we shall be concentrating on written material (prayers, vows and formulae), and on the distinctive characteristics of communication between Romans and their gods.