3 Religion in the late Republic

On 29 September 57 B.C. the pontifical college met in Rome to decide the fate of Cicero’s house. Cicero’s savage repression of the conspiracy of Catiline in 63 B.C. (a dastardly revolutionary plot, or a storm in a tea-cup, depending on your point of view) had rebounded on him. Publius Clodius Pulcher, his personal and political enemy, had taken advantage of Cicero’s illegal execution of Roman citizens among the conspirators without even the semblance of a trial; and in 58 B.C. – with his old enemy clearly in mind – had passed a law condemning to exile anyone who had failed to adopt the proper legal procedures in putting a citizen to death. Cicero was forced to leave the city, while Clodius promptly celebrated his victory with the destruction of Cicero’s house and by consecrating on part of its site a shrine to the goddess Liberty, Libertas (a devastatingly loaded, or intentionally irritating, choice of deity, no doubt – for it was the principles of libertas that Cicero was charged with violating). But, in the switchback politics of the 50s, the tables soon turned once more. By 57 Cicero had been recalled, and the senate, faced with the problem of his property, referred to the pontifices the question of whether or not the consecration of the site had been valid; whether or not, in other words, Cicero could have his land back. After hearing representatives from both sides, the college decided that, as the consecration had been carried out without the authorization of the Roman people (and so was invalid), the site could be returned to Cicero. The senate confirmed the decision – and Cicero set about re-building.1

What sets this incident apart from any of the religious events we have touched on in earlier chapters is the survival of the speech that Cicero delivered to the pontifices on the occasion of the hearing. We do not, in other words, come to this piece of priestly business through the formal record of problem and decision, in the few sentences (at most) that Livy would normally choose to allot to such matters; we do not meet it as part of history, business done and decided. Cicero’s speech (even though altered or embellished, no doubt, after delivery for written circulation) takes us right into the uncertain process of religious decision making, into the heart of the contest. It does not reflect or record the discourse of religion; it is that discourse.

Of course, we know (as did ancient readers) that Cicero won the case. And so his words inevitably enlist us as admiring witnesses to the winning arguments in priestly debate, the successful repartee of religious conflict, the clever flattery directed to the priests by this pleader in the pontifical court. For example, when Cicero opens with the impressive lines:

Among the many things, gentlemen of the pontifical college, that our ancestors created and established under divine inspiration, nothing is more renowned than their decision to entrust the worship of the gods and the highest interests of the state to the same men – so that the most eminent and illustrious citizens might ensure the maintenance of religion by the proper administration of the state, and the maintenance of the state by the prudent interpretation of religion,2

we should not forget that this is not only an astute analysis of the overlap of political and religious officials in the late Republic, the interplay of religion and politics. It is also an expert orator’s estimation of how a group of Roman priests would wish to hear their roles defined; as well as, no doubt, a reflection of what a wider readership (of the ‘published’ version of the speech) would be expected to think an appropriate opening in a speech given to the pontifices... All these issues are the subject of this chapter; the formal adjudication of the religious status of Cicero’s property is only one aspect of the religion of the late Republic; equally important is how that adjudication is presented and discussed at every level.

Cicero’s speech On his House is not an isolated survival, a lucky ‘one-off’ for the historian of late republican religion. A leading political figure of his day, the most famous Roman orator ever, and prolific author – Cicero’s writing takes the reader time and again into the immediacy of religious debate and the day-to-day operations of religious business. Another surviving speech, originally delivered to the senate in 56 B.C., deals directly and at length with the response given by the haruspices to a strange rumbling noise that had been heard outside Rome, and attempts (once more in conflict with Clodius) to settle a ‘correct’ interpretation on the enigmatic words of the diviners.3 And in many others, religious arguments (and arguments about religion) play a crucial part, even if not as the main focus of the speech: Cicero’s notorious opponent Verres (one time Roman governor of Sicily, on trial for extortion) is, for example, stridently attacked for fiddling the accounts during a restoration of the temple of Castor in the Roman forum;4 Pompey, on the other hand, gets Cicero’s full backing for a new military command on the grounds that he is particularly favoured by the gods.5 Outside the public arena of forum or senate-house, Cicero’s surviving correspondence (particularly the hundreds of letters to his friend Atticus) gives at some periods an almost daily commentary on all manner of ‘religious’ news: from the discovery of a case of sacrilege and its upshots, to Cicero’s despair at the death of his daughter Tullia and his elaborate plans to build her a ‘shrine’ (fanum) and to achieve her apotheosis.6

We shall look in more detail in the following sections at many of these examples; but we shall look too at Cicero’s theoretical analysis of the religion of his own time. For he was not only a major actor on the political scene and a vivid reporter of day-to-day events (in religion, politics or whatever sphere); he was also the leading philosopher, theologian and theorist of his generation – which was itself the first generation at Rome to develop an analytical critique of Roman customs and traditions. Of course, many Romans from as far back as the foundation of their city must have wondered about the existence or character of the gods, or the reasons for their worship; but it was the late Republic that saw the transformation of that speculation (partly through the influence of Greek philosophy) into written, intellectual analysis. Cicero himself wrote carefully argued treatises On the Nature of the Gods and On Divination (where he put all kinds of Roman divinatory practice, from prodigies to dream interpretation, under a sceptical microscope); and in his book On the Laws (inspired by Plato’s work of the same name) he even devised an elaborate code of religious rules for an ideal city – not so very different from an idealized Rome. This new tradition of explicit self-reflection is another factor that sets the history of late republican religion apart from earlier centuries.7

Cicero’s writing dominates the late Republic, and inevitably focusses our attention onto the years from the late 80s to the mid 40s, the period of his surviving speeches, letters and treatises. In most of his arguments (such as that over his house, or on the response of the haruspices) the view of ‘the other side’ is lost to us, except as it is represented (or mis-represented) by Cicero himself. There is, for example, no surviving trace of Clodius’ speech to the pontifices in which he must have made his counter-claims in favour of the shrine of Liberty; and we have only Cicero’s allusions to Clodius’ rival interpretation of the haruspical response. So, in what follows, we shall on occasion be prompted to wonder what these religious debates as a whole might have looked like, not just Cicero’s side of the argument.

But Cicero, though dominant, is not the only surviving witness of late republican religion; not the only surviving author of the period to define, debate and write late republican religion for us. Even without Cicero, the list of relevant contemporary material far outstrips anything we have found in earlier chapters of this book: from Lucretius’ philosophical poem On the Nature of Things (which attempts to remove death’s sting with a materialist theory of incessant flux)8 to Catullus’ poem on the self-castration of Attis, the mythical consort of the goddess Magna Mater (whose introduction to Rome was discussed in chapter 2);9 from the surviving fragments, quoted in later writers, of Varro’s great encyclopaedia of the gods and religious institutions of the city (the work of a polymath who outbid even Cicero in antiquarian learning)10 to two long autobiographical accounts from the pen of the pontifex maximus himself (better known as Julius Caesar’s Gallic War and Civil War).11 It is in all this writing that we can glimpse for the first (and arguably the only) time in Roman history something of the complexity of religion and its representations, the different perspectives, interests, practices and discourses that constitute the religion of Rome.

In the light of this apparent prominence of religious concerns in the writing of the first century B.C., it may come as a surprise that the religion of this period has so often appeared to modern observers to be a classic case of religion ‘in decline’, neglected or manipulated for ‘purely political’ ends. If (as we have already seen) intimations of decline have been an undercurrent in the modern accounts of almost every period of republican religious history, here in the first century B.C. those intimations are horribly fulfilled; here the scenario offered us is not merely that of a few sacred chickens unceremoniously dumped overboard, but of whole temples falling down, priesthoods left unfilled, omens and oracles cynically invented for political advantage...12

Many factors have worked together to make this grim picture seem plausible. In part, religion has been conscripted into a narrative of political decline in the last century of the Republic: over the hundred years of (more or less) civil war from the Gracchi to the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 B.C., in which rival Roman generals battled it out for control of most of the known world, the traditions of the (free) Republic sank into autocracy; and religion, predictably, sank with the best of them.13 But there is more underlying the view of religious decline than simply a convenient model of the collapse of republican Rome. One of the reasons that decline has entered the analysis is precisely because several ancient writers themselves chose to characterize the religion of the period in this way. The poet Horace, like other authors writing under the first emperor Augustus, looked back to the final decades of the Republic as an era of religious desolation – at the same time, urging the new generation to restore the temples and, by implication, the religious traditions:

You will expiate the sins of your ancestors, though you do not deserve to, citizen of Rome, until you have rebuilt the temples and the ruined shrines of the gods and the images fouled with black smoke.14

And this view of neglect is apparently borne out not only by Augustus’ own claim (in his Achievements) that he had restored 82 temples in his sixth consulship (28 B.C.) alone, but also by various observations in late republican authors themselves. Varro, for example, explained his religious encyclopaedia as a necessary attempt to rescue from oblivion the most ancient strands of Roman religious tradition – offering a baroque (and grossly self-flattering) comparison of his project with Aeneas’ rescue of his household gods from the burning ruins of Troy.15

The first two sections of this chapter will explore further the apparent contrast between these two images of Roman religion in the late Republic: on the one hand, its centrality within a wide range of ancient writing, its generation of new, explicitly religious forms of expression in Roman theology and philosophy; on the other, its decline and neglect, as witnessed and lamented by Romans themselves. We will consider, in particular, what kind of comparison is possible between the religious life of the late Republic and earlier (or later) periods; and how we can ever evaluate claims that this (or any) religion is in decline, what it would mean, for example, to know that a religious system was demonstrably ‘failing’ – then or now.

In the second part of the chapter, we will turn to other aspects of the religion of the period: from the involvement of religious practice and conflicts in the political battles of the end of the Republic, through the deification of Julius Caesar, to the changing relations of Roman religion with the growing Roman empire. But through all these discussions we shall attempt to highlight the particular importance of contemporary religious discourse and debate, and the new ways of representing religion that were characteristic of the Ciceronian generation. To be sure, we do not imagine the urban poor or the rural peasants (who made up the vast majority of the Roman citizens at this, as at every, date) participating in the kind of theoretical discussions staged for us by Cicero; those discussions were the pastime of a very few, even among the élite. But it was a pastime that was to change forever the way Roman religion could be understood and discussed by Romans themselves. For the revolution of the late Republic was as much intellectual as it was political, as much a revolution of the mind as of the sword; and religion was part of that revolution of the mind.

1. Comparative history?

The controversy around Cicero’s house, with which we opened this chapter, reveals some of the problems that face anyone trying to compare the status and ‘strength’ of religion between, say, the middle and late Republic (between, that is, the periods discussed in this and the last chapter). As we saw, Cicero’s speech before the pontifices took us right into the middle of religious conflict, into a world of religious rules that were not fixed (or at least were open to challenge), into the inextricable mixture of religious, political and personal enmity. It is a totally different kind of representation of religious business from the brief, ordered, retrospective account of a historian such as Livy, on whom we depend for almost all we think we know of religion in the middle Republic.

The modern observer is faced with (at least) two quite separate possibilities in comparing the Ciceronian-style account of the first century with the Livian style of the third or early second centuries. The first is that in religious terms these two periods really were worlds apart; that by the late Republic the ordered rules of religious practice that typified the earlier years, and are reflected in Livy, had irrevocably broken down into the conflict and dissent of which Cicero’s speeches, on this and other occasions, are a significant part. The second is that the apparent difference between the two periods lies essentially in the mode of representation: the difference, in other words, is between the contribution of an engaged participant (Cicero) and the narrative of a distanced annalistic historian (Livy). On this model, if we still had Livy’s account of the argument over the consecration of Cicero’s house, it would be hard to distinguish from those earlier disputes (between pontifex maximus and flamen, for example), where Livy gives us just the bare bones of the conflict, the final decision and very little more. And so, conversely, if we still had the words spoken by the different parties in the disputes so tersely related by Livy they would look just as charged, just as personally loaded, just as challenging to the idea of religious consensus as anything spoken by Cicero. Livy himself hints as much when – in recounting the argument of 189 B.C. between the pontifex maximus and the flamen Quirinalis (who wished to take command of a province, against the will of the pontifex) – he briefly mentions ‘the vigorous quarrels’ in the senate and assembly, ‘appeals to the tribunes’, the ‘anger’ of the losing party.16 Scratch the surface of the Livian narrative, in other words, and you would find a whole series of speeches very like Cicero’s.

Neither of these views is particularly convincing, at least not in an extreme form. Although there clearly is a difference of reporting, and a wholly different purpose in the different accounts, we are not dealing simply with a different rhetorical style. It is hard to believe that there was no difference in the character and importance of religious arguments in the two periods; hard to believe that while the Republic lurched to its collapse, it was business as usual in the religious department. If nothing else, the simple fact of the circulation of such speeches as Cicero s, the fact that this kind of religious argument was available to be read outside the meeting at which it was originally delivered, speaks to some difference in religious atmosphere in the last years of the Republic.17 The problem is, what difference? And how are we to characterize the complex of similarities and differences that mark the late republican changes?

Some of the same issues are at stake when we come to explore the contrasts between the last decades of the Republic and the early imperial period; and to explore the repeated claims in Augustan literature that the new emperor brought a new religious deal, after the impious neglect that had marked the previous era. It is obviously important to recognize that the Augustan régime was inevitably committed to that view of religious decline and restoration; that, if the traditional axiom that proper piety towards the gods brought Roman success still meant anything, then the disasters of the civil wars that finally destroyed the Republic (and Rome too – almost) could only signify impiety and neglect of the gods; and that this predetermined logic of decline says a lot about Augustan self-imaging, but little perhaps about the ‘actual’ conditions of the late Republic. It is also the case that many of the nostalgic remarks of Cicero and Varro, that appear to confirm the sad state of religion in their own day, may be just that – nostalgia; and nostalgia, as a state of mind, can flourish under the healthiest of régimes. On the other hand, none of these considerations is sufficient to prove the republican decline of religion merely an Augustan fiction, or just intellectual nostalgia. Varro, for example, supplied a great deal of information about cults and practices that had lapsed by his own time, which he identified (nostalgically maybe) as evidence of decline. Besides, it may be that the nostalgia of the late Republic, the pervading sense (whatever the truth) that religion was somehow in better shape in the past, is one of the most important characteristics that we should be investigating.

The problems in trying to judge this period of religious history against its neighbours, to calibrate its religious strengths and weaknesses, are almost insurmountable. And it is probably not worth the effort; after all, what would it mean to say, of our own time, that the twentieth century was less or more pious, less or more religious, less or more concerned with theology, than the nineteenth?18 There is, however, one area where we can test the difference in levels of piety that is proclaimed between the late Republic and what preceded and followed it: temple foundation and repair. We saw in chapter 2 how temple building could be a useful indicator of changing religious preferences among the Roman élite; we now take that discussion of the material setting of religion forward into the late second and first centuries B.C., with some rather different questions in mind. At the same time, we shall be able to see one of the contributions that archaeology can make to our understanding of religious history even in a period that is so well documented by literary texts.

The questions we will be looking to answer are these: what happened to the religious buildings of the city during the late Republic? were ancient temples duly tended and repaired? were new temples founded? how different was the late republican pattern from what had gone before? Once again comparison between Livy and Cicero is central to the issue. Livy records, as we have seen, an impressive series of temple buildings and dedications up to the mid second century B.C. (where his surviving text breaks off).19 Cicero, from time to time, focusses on a particular crisis surrounding a temple: Verres’ supposedly fraudulent restoration of the Temple of Castor, for example, or the accidental destruction of the temple of the Nymphs in street riots in 57 B.C.20 Otherwise temples only feature prominently again in the Augustan literature that claims the restoration of the dilapidations of the previous generation and vaunts its own lavish temple building schemes (some of which still survive).21 It is clear from this bald summary how modern observers have come to conclude that the late Republic was a particularly low point in care for the religious buildings of the city – which is itself seen as a significant index for respect for religion more generally. It is also clear, from what we have already said, that there can be no simple comparison between Livy’s text on the one hand (with its regular inclusion of information on major religious dedications) and Cicero’s writing on the other (where temple matters intrude only when out of the ordinary or relevant to some oratorical purpose at hand); or between Cicero and the pietistic boasts found in some Augustan writers.22 But can we go further than that, to show (for example) that the Augustan representation of late republican temple dilapidation – however crucial to Augustan self-representation – is, in late republican terms, a mis-representation?

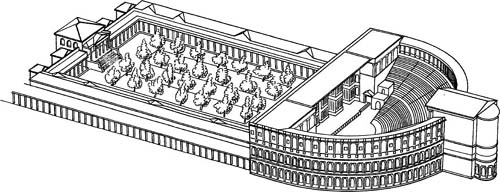

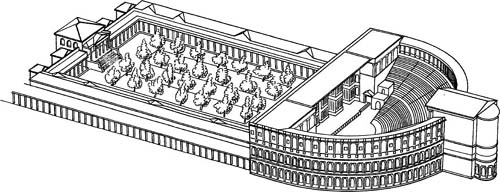

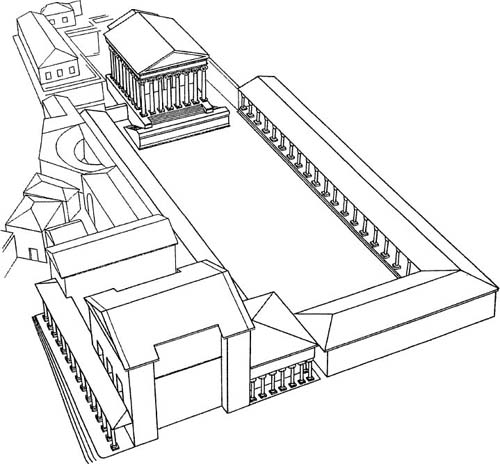

Fig. 3.1 Pompey’s temple and theatre-complex on the Campus Martius in Rome (dedicated 55 B.C.), according to one of the many possible reconstructions. The temple of Venus Victrix is on the far right, approached by the stepped auditorium of the theatre; beyond the stage, to the left, a garden surrounded by colonnades. (Map 1 no. 35) (Overall length of the theatre and garden, c. 260m.)

For once, we believe that we can – up to a point. A careful search through the casual references (often in later writers) to religious building projects of the period, combined with the surviving evidence of archaeology, can produce a clear enough picture of the regular founding of new temples and the continued maintenance of the old through the last years of the Republic. The great generals of the first century B.C. seem to have followed the pattern of their predecessors in founding (presumably out of the spoils of their victories) new temples in the city.

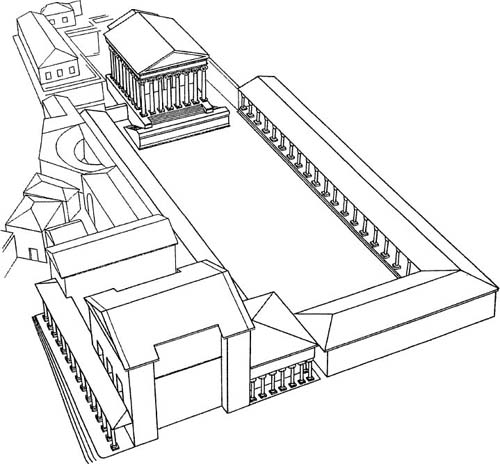

Pompey (to take just one of these generals) can be credited with at least three foundations: a temple of Hercules (briefly alluded to in Vitruvius’ handbook On Architecture and Pliny’s Natural History);23 a temple of Minerva (also known from a brief discussion by Pliny);24 and a much more famous temple of Venus Victrix, ‘Giver of Victory’ (Fig. 3.1).25 This temple of Venus has often been underrated as a religious building because it was part of a lavish scheme, closely associated with a theatre – as if its real purpose was (or so many modern observers, and ancient Christian polemicists, have thought)26 merely to give respectability to a place of popular entertainment. In fact, whatever Pompey’s real motives, it fits into a long Italian tradition of just such ‘theatre-temples’ and is not a smart new invention at all.27 Caesar too was involved in major religious building. His new forum was centred around a temple of Venus Genetrix (‘the Ancestor’ – both of the Romans and his own family, the Julii), dedicated in 46 B.C. (Fig. 3.2); and he planned (though did not live to complete) a huge new temple of Mars, which (according to Suetonius) was to be the biggest temple anywhere in the world.28

Fig. 3.2 Caesar’s Forum (a possible reconstruction). The temple of Venus Genetrix stands at one end of the open piazza. (Map 1 no. 10) (Overall length of temple and forum, c.l33m.)

Even outside the circle of the most powerful figures of the period, other foundations by less prominent members of the élite can also be traced. There are, for example, three inscriptions surviving from Rome that mention a ‘caretaker’ (aedituus) of the temple of Diana Planciana. It seems very likely that the name ‘Planciana’ refers to the founder of the temple, probably Cnaeus Plancius, who issued coins bearing symbols of Diana in 55 B.C. Plancius was not a leading figure in late-republican Rome; though he was important enough to be elected aedile in the mid-50s B.C. and was defended by Cicero (in his speech For Plancius) against a charge of electoral corruption.29

A very similar picture emerges if we consider the restoration of existing temple buildings. The repair and upkeep of the Capitoline temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus was clearly prestigious enough to be the object of competition between leading magistrates: for example, in 62 B.C. Julius Caesar as praetor tried to remove responsibility for the upkeep from Quintus Lutatius Catulus (and give it to Pompey) on the grounds that he was taking too long over restoration.30 But other, less illustrious, temples had facelifts too. Cicero, for example, refers in his letters to his own embellishment of the temple of Tellus (Earth);31 and one of the few thoroughly excavated temples in the city, the temple of Juturna (Temple A, in the site known as the Largo Argentina), appears from the surviving remains to have been extensively refaced in the middle years of the first century B.C.32

We have more than enough material then to undermine any strident claims (whether made by ancient or modern authors) that the religious environment of the late Republic was in a state of complete neglect or collapse. We can be confident, at the very least, that those claims are seriously exaggerated; they may even be quite ‘wrong’. But this is not the end of our problem. Unless we are to convict the Augustan authors of wilful deception, we shall still be faced with wondering in what sense, for them, the claims of religious dilapidation were ‘true’. One possibility is that they were (in a limited sense) literally true, but only at the very end of the Republic as a result of the sustained and vicious bout of civil war which followed Caesar’s assassination in 44 B.C. It is also possible, however, that they were true only in the sense of the traditional symbolic logic of Roman piety: the proper worship of the gods leads to Roman success; Roman failure stems from the neglect of the gods; the temples of the city must have been neglected during a period of Roman political failure. But even (or especially) if that is the case, those claims – false or not by other criteria – remain religious claims that demand our attention, not dismissal.

Besides, there may be a large gap between the fabric of the religious buildings of the city of Rome and the religious ideology, attitudes and devotion of its citizens. We are well aware from our own experience that there sometimes is, and sometimes is not, a connection between the upkeep of religious buildings and the upkeep of ‘faith’; and the connection is equally hazardous for Rome. We can never know what any Roman ‘felt’, at any period, when he decided to use his wealth to build a temple to a particular god; still less how Romans might have felt when entering, walking past or simply gazing at the religious monuments of their city. If the continued upkeep of temple buildings is, in other words, an index of continuity of expenditure on religious display, it is not necessarily an index of continuity of attitude, feeling or experience. As we move on through this chapter to look at different areas of the Roman religious world, we shall keep in mind what might count as an index of that experience.

2. Disruption and neglect?

Many of the contemporary, or near contemporary, accounts of religious conflict in the late Republic do suggest extraordinary disruptions in the religious life of the city. Irrespective of any model of development or decline; irrespective, that is, of any suggestion that the situation was worse then than in the periods that immediately preceded or followed it; irrespective of the political turmoil that almost inevitably implicated the religious institutions of the state... irrespective of all such considerations, religion in the last decades of the Republic was conspicuously failing, neglected, abused, manipulated, flouted. That at least (as we have already noted) has been the view of many modern commentators.

This section examines two of the major incidents, the causes célèbres, of late republican religious ‘abuse’. It reveals a set of religious rules, a religious ‘system’, that is often disrupted during this period; sometimes unable to adapt to all the strange and unprecedented circumstances that it faced; occasionally pushed to the limit of what political advantage might be extracted from it;33 overloaded, certainly, by the enormous political stakes that were now entailed in almost every public conflict (it was, after all, control of the whole world that Caesar and Pompey fought out in the civil war of the 40s B.C.). But, crucially, neither of these incidents, nor any of the others we might have chosen to highlight, attest an atmosphere in which religious traditions were simply violated: we find, for example, no case where the formal decision of a college of priests was blithely contravened; no clear case where the proper religious procedures (however problematically defined) were simply ignored.

At the same time, this section will pose the question of what constitutes religious neglect, as it explores two particular cases of religious traditions that changed or died out during the period. Here we shall meet again the challenge of different points of view, different judgements passed on the same events. So, for example, some observers (ancient or modern) will interpret the disappearance of a particular priesthood, or the neglect of a particular tradition, as an indication of the strength of the religious system overall; it is, after all, only a dead system, a religious fossil, that preserves all its traditions, no matter how far circumstances have changed; any living religion discards some of the old, while bringing on the new; in short, it adapts. But for other observers the same disappearance, of a ritual (say) carried out for centuries, or of a priesthood that (however quaintly old-fashioned) evoked some of the most hallowed traditions of the city, will mark a crucial stage in Rome’s disregard for its gods, its collective amnesia about their worship. The point is, as we shall see, that ‘neglect’ is always a matter of interpretation; and accusations of neglect almost inevitably appear hand in hand with boasts of adaptation and updating. Both sides of the coin have to be taken seriously.

Bibulus watches the heavens

As consul in 59 B.C., Julius Caesar introduced into the assembly a notoriously controversial piece of legislation to redistribute land to veteran soldiers; the bill was implacably opposed by his colleague in the consulship, Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus. The precise details of the conflict are far from clear. But it seems that at the beginning of the year Bibulus offered objection to Caesar’s proposals in the traditional way: he appeared in the Forum and declared to the presiding magistrate that he had seen (or that he would be watching for) evil omens, preventing the progress of legislation.34 We, of course, do not know what exactly these omens were, or what it would have meant for Bibulus to claim to have seen them. But the logic of this kind of procedure (which has an established place in Roman voting and legislation)35 is clear enough: if the gods support and promote the Roman state (as they do), then they will make known their opposition to legislation that is against the interests of the state. The snag, of course, is that there could be vastly different views on what legislation is in fact ‘good for Rome’.

As the year went on, however, there was more and more rioting and civil disturbance. And Bibulus himself became the object of such violent assaults from partisans of Caesar that he took refuge in his own house; too frightened to go out, perhaps, he simply issued messages that he was watching the sky for omens (de caelo spectare). The assemblies went ahead despite these objections and the land bill and other controversial legislation were passed.36 These laws were to prove vulnerable to all kinds of challenge, on the grounds that their passing had violated religious rules. On one occasion in 58 B.C., according to Cicero, Clodius himself arranged a public meeting (contio) with Bibulus and a group of augurs. This was not a formal session of the priestly college, followed by a formal priestly ruling on the problem, but a chance, it seems, for Clodius to put the hypothetical question to the priests: if you were to be asked, as priests, if it was legal to conduct an assembly while Bibulus was watching the heavens, what would you say? Cicero claims (but he would...) that the augurs replied that such an assembly would not be legal.37 In fact, however, no such question was ever formally put to them as a college; and Caesar’s legislation remained challenged, but in force.38

One way of looking at this incident is as a flagrant example of the heedless flouting of religious rules in the last phase of the Republic: Bibulus had followed traditional procedures (validated by the augurs in their discussion with Clodius), but Caesar and his friends had simply ridden roughshod over them all. Cicero presumably reasoned that way, as have many modern observers – who have seen in this incident a clear case of the absolute domination of religious concerns by factional politics; and blatant disregard for religious obligations where they conflicted with secular ambitions. But this is only one side of the story. Through all the partisan ranting of Cicero in favour of Bibulus’ objections, one thing is clear: that the status of Caesar’s legislation was, and remained, controversial. Caesar (the pontifex maximus) did not, in other words, simply get away with total disregard for religious propriety. We need to try to get closer to what might lie at the centre of the controversy.

It seems very likely that a question mark hung over the effective status of Bibulus’ own actions. He claimed through much of his consulship to be ‘watching the heavens’, but he did not – as was, we assume, the traditional practice – declare this in person to the presiding magistrate before the assembly took place; instead, he sent a series of runners carrying messages of what he was doing...! Such a procedure could have been seen in at least two completely different ways. On the one hand it must have been argued that, once Bibulus had incarcerated himself at home and started simply to send messages that he was watching the heavens’, his objections had no validity; for ill omens only constituted proper obstruction to public business if announced in person, on the spot.39 On the other, it must also have been arguable that, since violence made it impossible for Bibulus to attend the assemblies and follow the standard procedures, the religious objections should stand, however procedurally incorrect. And even some of Caesar’s own supporters seem to have taken the line (or so, again, Cicero would have us believe) that the legislation should be re-submitted, this time with all the proper observances.40

It is now (and almost certainly would have been then) hard to resolve those two opposing views. That is of course the point. We have no precise idea of the terms that governed the declaration of ill omens, but it seems very likely that, while they may have assumed the presence of the objector at the assembly concerned, they did not directly stipulate it.41 For the conventions of this religious practice had taken shape over a period when the effects of the prolonged urban violence of the last decades of the Republic could hardly have been foreseen; earlier generations, in other words, would not have thought to legislate for an objector who was too scared to go out. If so, it would not have been the case in 59 of not following the religious rules, but of not knowing what were the rules to follow.

All kinds of factors come together to make Bibulus’ objections to Caesar’s legislation in 59 such a cause célèbre. Beyond the accusations and counter-accusations over the uncertainty of the religious rules themselves, there was also the fact that an enormous amount was at stake in any decision; if Bibulus’ objections were valid, then the whole legislative programme of Caesar’s consulship would have to be annulled (as well as all the legislation passed by Clodius as tribune).42 It may well have been the republican tradition to improvise the religious rules as was necessary, but too much was at stake here for that improvisation to work smoothly: the legislative and constitutional chaos that would have followed the annulment of all decisions made in the face of Bibulus’ objection is unthinkable. The sheer scale of political business (and its implications) presumably was a distinctive feature of the political and religious world of the late Republic. Whether or not it amounts to a proof of a failing religious system depends on your point of view.

The trial of Clodius

A slightly earlier incident of religious conflict provides a second example of these difficulties in applying the traditional rules. This was the controversy of 62–61 B.C., after the invasion of ceremonies of the Bona Dea (traditionally restricted to women only) by Cicero’s adversary – so it was believed – Publius Clodius Pulcher. This incident was apparently followed immediately by faultlessly correct action: the Vestal Virgins repeated the ritual; the senate asked the Vestals and pontifices to investigate, and they judged it to count as sacrilege; the consuls were instructed to frame a bill to institute a formal trial; Julius Caesar (in whose house the ceremonies had taken place) even divorced his wife as a direct result of the scandal.43 So far, so good; but some of the quarrels and disagreements that were to surround the trial itself again suggest uncertainty in how such a process should be handled, and in the eyes of some, no doubt, a breakdown in the city’s ability to control religious disorder.

We should recognize straight away that the act of sacrilege on its own (however outrageous to contemporary observers) is not particularly important for our view of late republican religion. It is hard to imagine that there had not always been this kind of isolated, high-spirited attack on the traditional conventions of ritual; for no religion anywhere has succeeded in getting everyone to obey all the rules all the time, and most religions (we suspect) have not particularly sought to.44 Nor is the fact that Clodius was eventually acquitted itself a strong signal of religious failure. For despite the fulminations of Cicero (who, predictably, attributed the acquittal to bribery of the jury), very few people could have known – and we and Cicero are certainly not among them – whether Clodius was guilty or not. The problems are much more to be located in the squabbles over whether there should be a formal trial at all, and how the jury was to be composed.

Throughout his account of these events in his letters to Atticus, Cicero huffs and puffs – deriding (as he had to45) almost every aspect of the procedure, from the mistaken tactics of his own allies to the failure at one stage in the voting proceedings to produce any ballot papers with the option ‘yes’ on them. At the same time, though, he makes it absolutely clear that the handling of the sacrilege was high on the public agenda, a major focus of debate. Part of this debate may well have been prompted by all kinds of personal enmities and loyalties, by the interests of factional politics; for a conviction on such a charge would certainly have put Clodius’ whole career in jeopardy. But this is not at all to suggest that there was widespread acceptance of behaviour that appeared to flout traditional, religious rules; quite the reverse, in fact, if we imagine that Clodius’ career really was in danger. The problems lie, rather, in formulating the details of the judicial action, in establishing a procedure for dealing with this particular religious crime – in the context of such ruinously high stakes. Cicero, we should remember, reports no claim that the disruption of the festival didn’t matter, or that such religious business was the concern only of a few old grey-beards.

The flamen Dialis

For more than seventy years, from 87 or 86 B.C. to 11 B.C., the office of flamen Dialis, the ancient priesthood of Jupiter, was left unfilled.46 Not surprisingly, this has been seen as a classic example of religious neglect. Some ancient authors write in approval of Augustus’ appointment of a new priest after the long gap, as one component of his ‘revival’ of traditional religion.47 For many modern writers, the lapse in the office has been one of the clearest signs of the Roman élite’s lack of interest in religion at this period or, at least, of their shifting priorities: they were, in other words, no longer willing to countenance the inconvenient taboos of this venerable office (particularly when those taboos, as we have seen, could obstruct a full political and military career). All this is true, so far as it goes. Augustus very likely did vaunt his re-appointment of a flamen Dialis, as a sign of a new religious deal after decades of neglect; and so it might well have appeared to many observers at the time. No doubt also there were some members of the Roman aristocracy (as we know already from centuries earlier) who found the archaic restrictions on this particular priest more than irksome.48 None the less, if we examine the circumstances that lie behind the first vacancy in the priesthood in the 80s, we shall find them to be rather more complicated than simple unwillingness to undertake the office; and we shall find the degree of neglect of the rituals normally undertaken by the priest much less than is often assumed. In the case of the flamen Dialis we can glimpse some of the complex stories that might lie behind any instance of apparent neglect of traditional ritual.

The story starts in the civil wars in the 80s B.C. When Rome was under the control of Cinna and Marius, in 87 or in early 86, the young Julius Caesar was designated as flamen Dialis, in succession to Lucius Cornelius Merula, who had committed suicide after the Marian takeover of the city. But before Caesar had been formally inaugurated into the office, Rome had fallen once more to Sulla, who annulled all the enactments and appointments made by his enemies.49 It is impossible now to reconstruct how the Roman élite viewed the vacant flaminate, or Caesar’s status in relation to the priestly office that arguably he already filled. It is impossible to know whether or not Caesar himself was privately relieved to find a convenient way out of a priesthood that would, in due course, almost certainly have conflicted with his political ambitions. But we can see that it was Sulla’s action in dismissing Caesar, in the confusion of civil war, that represented the first step in the suspension of the priesthood; not, that is, some general agreement that the office no longer mattered.

The crucial decision, of course, was what should happen to the various rituals usually carried out by the flamen: the absence of a priest was one thing, the failure to fulfil the proper rituals of the state was quite another. We have already seen that the peculiar position of the flamines as individual priests of their deity could be seen to demand that the rituals assigned to them were carried out by them alone, outside the collegiate structure of the pontifical college (which would normally imply the interchangeability of one priest with another). On the other hand, if you chose to think of the flamines as regular members of the pontifical college, it would be clear enough that, in the absence of a flamen, his duties could fall to the other pontifices. This is, in fact, precisely what Tacitus states, when he puts into the mouth of the flamen Dialis of A.D. 22 the claim that, over the long years when the priesthood was unoccupied, the pontifices performed the rituals: ‘the ceremonies continued without interruption’ and even though the office was vacant ‘there was no detriment to the rites’.50 Of course, this particular priest has an axe to grind himself; for these are his arguments in support of his own claim to be allowed out of Italy to hold the governorship of the province of Asia. But, even so, he gives us a further clue as to how the long vacancy in the office might have developed. Suppose there was a brief period when there was widespread uncertainty about who was (or was not) the flamen Dialis; suppose then (as we have seen was almost certainly the case) the pontifices took over the rituals of the vacant priesthood; and suppose this situation carried on, as a temporary measure, for a whole year, for the complete annual cycle of ceremonies normally performed by the flamen ... Is that not already the makings of a new system? Has it not already habituated the Roman élite to a change of roles amongst the priestly hierarchy? Has not the lapse in the tenure of the flaminate been effectively masked?

Yes and no. For some Romans, the performance of the rituals was probably what really counted, the absence of an archaic priest, with a strange pointed hat, much less. For others, the vacancy in an office which (as its odd taboos underlined) represented the most ancient traditions of Roman piety, stretching back as far as you could trace into the mythical origins of the city, must have seemed a clear sign that Rome was disastrously failing in its obligations to the gods. Still others (presumably the vast majority) would never even have noticed the absence.51 For us, however, the circumstances surrounding the lapse in this office (more than the simple fact of the lapse itself) highlight the close interrelationship between the disturbances of civil war and the apparent ‘neglect’ of religion; as well as the various tactics of change and adaptation (in this case a growth in the ritual obligations of the pontifices) that might accompany such lapses.

The changing ceremony of evocatio

Our next example focusses even more strongly on these changes. The geographical expansion of Roman imperial power underlies several of the most striking losses and adaptations in the religious traditions of Rome during the late Republic. Various rituals of war, for example, that originated in the now distant days when Rome was fighting her Italian neighbours were no longer appropriate (and in some cases almost impossible to carry out) when Rome’s expansion was far overseas. One of the clearest instances of this is the ritual of the fetial priests on the declaration of war. It had been traditional fetial practice to proceed to the border of Rome’s territory and to hurl a ritual spear across into the enemy’s land: a first symbolic mark of the coming war. But when Rome’s enemies were no longer her neighbours, but lived hundreds of miles away overseas, that particular ritual became practically impossible to carry out – short of packing the priests off on a boat, and waiting maybe months for them to make the journey. Instead the ritual was retained in a new form: a piece of land in Rome itself, near the temple of Bellona, was designated (by legal fiction) ‘enemy ground’ and it was into this that the priests threw their spears. Whether this was a case of lazy sophistry, conscientious adaptation to new circumstances or imaginative creativity, the ritual continued to be carried out – but in a new form.52

The ritual of evocatio undergoes a similar, but more complex, change. As we have seen, the tradition here was that the Roman commander should press home his advantage in war by offering to the patron deity of the enemy a better temple and better worship in Rome, if he or she were to desert their home city and come over onto the Roman side. The best recorded occasion of this practice was the evocatio of the goddess Juno, patron of Veii, who deserted the Veians for the Romans in 396 (thus ensuring Rome’s victory), and who was worshipped thereafter at Rome with a famous temple on the Aventine Hill.53 It has often been thought that this practice had entirely died out at Rome by the late Republic. For the temple of Vortumnus (founded in 264 B.C.) is the last temple in the city clearly to owe its origin to this particular ritual; for whatever happened at the evocation of Juno from Carthage in 146 B.C. (even if we do not bracket it off as an antiquarian fantasy), there is no evidence that it resulted in the building of a new temple for the goddess in Rome.54 But an inscription discovered in Asia Minor suggests that the practice did not die out; rather, it was performed differently.

This inscription was discovered, on a building block, at the site of the city of Isaura Vetus, taken by the Romans in 75 B.C. It refers to the defeat of the city and to the fulfilment of a ‘vow’ of the Roman commander, echoing in its language some of the formulae used (as other, literary, accounts suggest) in the ceremony of evocatio. The most plausible explanation is that this inscribed stone comes from a temple dedicated by the Roman general to the patron deity of Isaura Vetus, who had been ‘called out’ of the town in the traditional way; but that on this occasion the temple offered to the deity was not in Rome itself, but on provincial territory.55

This is just one piece of evidence, fragmentary at that. But it may allow us to construct a different account of the late republican history of this ritual: not that it entirely died out, but that the location of the promised temple changed. If this is the case, it could be seen as a relaxation, a ‘watering down’, of the traditional religious obligations of the ritual. But it could also be seen in the context of changing definitions of ‘Roman-ness’, of what counted as ‘Roman’. Whereas in the early Republic to offer a rival deity a Roman home meant precisely offering a temple in the city itself, at the end of the Republic by contrast, imperial expansion, and the changing Roman horizons that went with it, meant that provincial territory could now be deemed Roman enough to stand for Rome. We may be dealing then with one feature (of which we shall see more later) of Roman religious adaptation to a vastly expanded empire.

The disruption of religion in the late Republic will continue to baffle its modern observers, as (no doubt) it baffled ancient observers too. It is not difficult to spot all kinds of ‘impieties’ and ‘failures’, or to be struck by the outrage of Cicero at some of the events he witnessed, by the irresolvable conflicts that threatened those whose business it was to handle Roman relations with the gods smoothly. But, not surprisingly (and appropriately enough), it is far less easy to evaluate or generalize. We have already emphasised, in discussing the four incidents that we have chosen in this section, how different interpretations follow from different points of view, and different starting points; how the same incident can be seen as outright neglect and constructive adaptation, cynical self-seeking and uncertain fumbling after the proper religious course of action. The same would be true if we were to look in any detail at any of the other particular causes célèbres we have not examined here: from accusations of forging oracles to priestly ‘manipulation’ of the calendar.56

Paradoxically, though, one thing does seem to be clear through this extraordinary array of different views, interpretations and debates: namely that religion remained throughout this period a central concern of the Roman governing class, even if principally as a focus of their conflicts. There was, in other words, a consensus that religion belonged high up on the public agenda. In the next section we shall explore this consensus further, as we look more closely at the role of religion within public, political debate from the late second century onwards.

3. The politics of religion

As part of Roman public life, religion was (and always had been) a part of the political struggles and disagreements in the city. Disputes that were, in our terms, concerned with political power and control, were in Rome necessarily associated with rival claims to religious expertise and with rival claims to privileged access to the gods. That was the view of Livy, for example, who – from his early imperial standpoint – perceived the political struggles of the early Republic partly in terms of struggles against patrician monopoly of religious knowledge and of access to the divine. In the final stages of his account of ‘The Struggle of the Orders’, he gives a vivid picture of the passing of the lex Ogulnia in 300 B.C., the law which gave plebeians designated places in the pontifical and augural colleges. The patricians, according to Livy, saw such a law as a contamination of religious rites, and so liable to bring disaster on the state; the plebeians regarded it as the necessary culmination of the inroads they had already made into magisterial and military office-holding.57 It would have made no sense in Roman terms to have claimed rights to political power without also claiming rights to religious authority and expertise.

The struggles of the late Republic and the ever intensifying political competition provide even clearer testimony of the inevitable religious dimension within political controversy at Rome. It was not just a question of arguments being framed (as we shall see clearly later) in terms of the will of the gods, or of divine approval manifest for this or that course of action. As political debate came to focus, in part at least, on the opposition between optimates and populares– on the clash, that is, between those who voiced the interests of the traditional governing class and those who claimed to speak for, and were in turn backed by, the people at large – religious debate too seems to have become increasingly concerned with issues of control between aristocracy and people: with attacks on the stranglehold of the optimates over priestly office-holding and with attempts to locate religious (along with political) authority more firmly in the hands of the people as a whole. The historian Sallust, for example, who interprets the conflicts of the late Republic very much in these terms, puts into the mouth of Caius Memmius (tribune 111 B.C.) a virulent attack on the dominance of the nobles, who

walk in grandeur before the eyes <of the people>, some flaunting their priesthoods and consulships, others their triumphs, just as if these were honours and not stolen goods.58

The juxtaposition of ‘priesthoods’ and ‘consulships’ here is not an accident. Those who resented what they saw as the illicit monopoly of power by a narrow group of nobles would necessarily assert the people’s right of control over both religious and political office, over dealings with the gods as well as with men.

One of the clearest cases of the assertion (and rejection) of popular control over religion is found in the series of laws governing the choice of priests for the four major priestly colleges. As we have seen in earlier chapters, the traditional means of recruiting priests to most of the colleges was co-optation: on the death of a serving priest, his colleagues in the college themselves selected his replacement (on what principles, we do not know). It was only in the case of the choice of the pontifex maximus from among the members of the pontifical college that a limited form of popular election had been practised, since the third century B.C.59 The process of co-optation had been first formally challenged (so far as we know) in 145 B.C., when Caius Licinius Crassus introduced a bill to replace the traditional system with popular election.60 That bill, as we saw in chapter 2, was defeated; but a similar proposal introduced in 104 B.C. by Cnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus (consul 96) succeeded: the priests of the four major colleges (pontifices, augures, decemviri and triumviri) retained the right to nominate candidates for their priesthoods, but the choice between the candidates nominated was put in the hands of a special popular assembly, formed by 17 out of the 35 Roman voting tribes – the method of election already used for the pontifex maximus. The priests themselves no longer had complete control over the membership of their colleges.

Roman writers offer various interpretations of this measure. Suetonius, in particular, stresses the personal motives of Domitius: having himself failed to be co-opted into the pontifical college, he proceeded out of pique to reform the method of entry.61 We cannot judge the truth of such allegations; and, indeed, all kinds of personal or narrowly political motives may have lain behind Domitius’ proposal. But the details of the law itself suggest that a delicate compromise between the interests of the people and the traditional priestly groups may have been at work here. On the one hand, the electoral assembly was (as we have noted) already used in a priestly context; while the definition of that body as being just less than half of the normal popular assembly (seventeen out of the thirty-five tribes) suggests that here, as with the election of the pontifex maximus, there might have been some compunction about asserting outright popular control over priestly business. It was also the case that the college could exclude any candidate of whom they did not, for whatever reason, approve. On the other hand, the requirement that each member of the college should make a nomination for election, and that no more than two priests could nominate the same candidate, looks like an attempt to ensure that the assembly had a real choice, that the college could not fix the election in advance. However guarded, this reform clearly represents a political and religious challenge to the dominance of the traditional élite, a claim for popular control over the full range of state offices.62

The regulations for priestly elections remained a live issue for years. Domitius’ law was repealed by the dictator Sulla, as part of his re-assertion of traditional senatorial control; but it was later re-enacted in 63 B.C. by the tribune Labienus – in the last of the series of laws which undid the various controversial aspects of Sulla’s reforms, after his retirement. Labienus was a well-known radical and at that time a friend of Julius Caesar; support for the ‘popular cause’ inevitably involved support for popular control of human relations with the gods.63

Another challenge to traditional religious authority can be detected in the events of 114–113 B.C., when a number of Vestal Virgins were declared guilty of unchastity and put to death (as was the rule) by burial alive in an underground chamber. The story starts in 114, when the daughter of a Roman equestrian had been struck dead by lightning, while riding on horseback; she was found with her tongue out and her dress pulled up to her waist. This was declared a prodigy and interpreted by the Etruscan haruspices as an indication of a scandal involving virgins and knights. As a result, in December 114, according to traditional practice, three Vestal Virgins were tried for unchastity before the pontifical college; one of them was found guilty and sentenced to death. In reaction to the acquittal of the other two Vestals, Sextus Peducaeus, tribune of 113 B.C., carried a bill through the popular assembly to institute a new trial – this time with jurors of equestrian rank and a specially appointed prosecutor, the ex-consul Lucius Cassius Longinus. This new trial resulted in a death sentence for the other two Vestals.64 The traditional competence of the pontifices to preserve correct relations with the gods had been called into question, while the power of the people to control the behaviour of public religious officials had been asserted.

On other occasions rival claims by individual politicians to privileged access to the gods provided the focus of political debate: a man could demonstrate the correctness of his own political stance by showing that he, rather than his political opponent, was acting in accordance with divine will. This was clearly the case in 56 B.C., when Cicero and Clodius engaged in public debate over the interpretation of a prodigy – Cicero’s speech On the Response of the Haruspices (as we have already mentioned) representing one side of the argument. The haruspical response to the strange noise that had been heard on lands outside Rome had alluded to various causes of divine anger with the city: the pollution of games (ludi); the profanation of sacred places; the killing of orators; neglected oaths; ancient and secret rituals performed improperly.65 Yet (no doubt following the traditional pattern of such responses) much still remained unclear and unspecific, in need of further interpretation and debate.

In the arguments that followed Clodius and Cicero offered their own quite different interpretations of what the haruspices had actually meant, item by item. Clodius, for example, claimed (rather convincingly, we are tempted to suggest – despite Cicero’s scorn) that the ‘profanation of sacred places’ was a reference to Cicero’s destruction of the shrine of Liberty. Cicero himself, on the other hand, in his surviving speech, related ‘the pollution of games’ to Clodius’ disruption of the Megalesian Games (held in honour of Magna Mater) and claimed that the ‘ancient and secret rituals performed improperly’ were the rituals of the Bona Dea, reputedly invaded by Clodius a few years earlier.66 Much of this debate was clearly a series of opportunistic appeals to a conveniently vague haruspical response; a crafty exploitation of religious forms at the (political) expense of a rival. But at the centre of the argument – what they were arguing about – was a priestly interpretation of a sign sent by the gods. When both Clodius and Cicero claimed as correct their own, partisan, interpretation of the prodigy, each was effectively attempting to establish his own position as the privileged interpreter of the will of the gods. Divine allegiance was important for the Roman politician. In the turbulent politics of the mid 50s, it must inevitably have been less clear than ever before where that allegiance lay. Connections with the gods (as well as the alienation of the divine from one’s rivals) had to be constantly paraded and re-paraded.

Underlying these apparently deep divisions over the control of religion and access to the favour of the gods, there was (as we noted at the end of the last section) a striking consensus of religious ideology. Cicero’s speeches offer a clear instance of this. Loaded, partisan, aggressively one-sided – they were the most successful works of political rhetoric that the Roman world had ever known, constantly admired and imitated. In speech after speech, Cicero enlists the support of his listeners (and later his readers) with appeals to the gods and to the shared traditions of Roman religion and myth. In the first of his speeches against Catiline, for example, delivered in 63 B.C. to the senate (meeting in the temple of Jupiter Stator on the lower slopes of the Palatine), part of his persuasion of the wavering senators draws on the traditions of the particular temple in which they are assembled. He not only evokes Jupiter ‘the Stayer’ (‘who holds the Romans firm in battle’ – or ‘who stops them from running for it...’), but interweaves allusions to the mythical foundation of the temple, vowed by Romulus in the heat of his battles with the Sabines. He offers, in other words, a mythical model for the kind of threat he claims the city faces from Catiline, and by implication presents himself as a new founder of Rome. Privately, many senators may have been irritated, disbelieving or amused by these claims; but it seems clear enough that Roman public discourse found one of its strongest rallying cries in such appeals to the city’s religious traditions.67

But this public religious consensus is important too in the conflicts and disagreements of late republican politics; it is not just a feature of grand Ciceronian appeals to ‘unity’ in the state. Crucially, there is no sign in any Roman political debate that any public figure ever openly rejected the traditional framework for understanding the gods’ relations with humankind. Political argument consisted in large part of accusations that ‘the other side’ had neglected their proper duty to the gods, or had flouted divine law. It was a competition (in our terms) about how, and by whom, access to the gods was to be controlled – not about rival claims on the importance or existence of the divine. So far as we can tell, no radical political stance brought with it a fundamental challenge to the traditional assumptions of how the gods operated in the world. There were, to be sure, as there always had been, individual cults and individual deities that were invested (for various reasons) with a particular popular resonance. The temple of Ceres, for example, as we have seen, had special ‘plebeian’ associations from the early Republic; likewise the cult of the Lares Compitales (at local shrines throughout the regions (vici) of the city) was a centre of religious and social life for, particularly, slaves and poor (and was later to be developed by Augustus precisely for its popular associations); while Clodius’ dedication of his shrine to Liberty on the site of Cicero’s house no doubt had, as must have been the intention, a popular appeal.68 There were always likely to be choices and preferences of this kind in any polytheism. But if these cults did act as a focus for an entirely different view of man’s relations with gods, no evidence has survived to suggest it.

The particular quarrels between Clodius and Cicero well illustrate the religious consensus that operated even (or especially) in disagreement. These battles are known, as we have already remarked, almost entirely from the side of Cicero, who constantly characterized Clodius as ‘the enemy of the gods’ – whether for the invasion of the rites of the Bona Dea, or the ‘destruction of the auspices (in his reforms of the rules for obnuntiatio in 58 B.C.). The truth that may lie behind any of these allegations is now impossible to assess (and in many cases always was). More important is the fact that Clodius appears to have returned in kind what were, after all, quite traditional accusations of divine disfavour. As we have seen from Cicero’s defence in his speech On the Response of the Haruspices, Clodius did not disregard or even ridicule Cicero’s religious rhetoric; he did not stand outside the system and laugh at its silly conventions. He turned the tables, and within the same religious framework as his opponent, he claimed the allegiance of the gods for himself, and their enmity for Cicero. It was similar with other radical politicians. Saturninus (tribune in 103 and 100 B.C.), for example, protected his contentious legislation by demanding an oath of observance (sanctio) sworn by the central civic deities of Jupiter and the Penates in front of the temple of Castor in the Forum;69 and Catiline kept a silver eagle in a shrine in his house, as if taking over for his uprising the symbolic protection of the eagle traditionally kept in the official shrine of a legionary camp.70 The question, then, was not whether the gods were perceived to co-operate with the political leaders of Rome; but with which political leaders was their favour placed?

But this raises yet another question, which we will turn to consider in the next section: quite how close is the co-operation of men and gods, quite how easy is it to draw a distinction between the divine and the human?

4. Divus Julius: becoming a god?

The honours granted to Julius Caesar immediately before his assassination suggest that he had been accorded the status of a god – or something very like it: he had, for example, the right to have a priest (flamen) of his cult, to adorn his house with a pediment (as if it were a temple) and to place his own image in formal processions of images of the gods. Shortly after his death, he was given other marks of divine status: altars, sacrifices, a temple and in 42 B.C. a formal decree of deification, making him divus Julius. Ever since the moment they were granted, these honours – particularly those granted before his death – have been the focus of debate. If you ask the question ‘Had Caesar officially become a Roman god, or not, before his death? Was he, or was he not, a deity?’ you will not find a clear answer. Predictably, both Roman writers and modern scholars offer different and often contradictory views.71 Some speak stridently for, some stridently against, his manifest divinity; taken together they attest only the impossibility of fixing a precise category for Caesar, whether divine or human.72

It is, nevertheless, certain enough that the honours granted to him before the Ides of March 44 B.C. likened him in various respects to the gods, assimilated him to divine status. That assimilation itself could be understood in different ways: both as an outrageously new, foreign, element within the political and religious horizons of the Roman élite, and as a form of honour which had strong traditional roots in Roman conceptions of deity and of relations between political leaders and the gods. On the one hand, that is, particular inspiration for various of Caesar’s divine symbols may well have been drawn from the East, and the cult repertoire of the Hellenistic kings; the public celebrations on Caesar’s birthday, for example, and the renaming of a calendar month and an electoral tribe in his honour have clear precedents in the honours paid to certain Hellenistic monarchs.73 On the other hand, some aspects of Caesar’s divine status are comprehensible as the developments of existing trends in Roman religious ideology and practice. The boundary between gods and men was never as rigidly defined in Roman paganism as it is supposed to be in modern Judaeo-Christian traditions. Even if, as we have seen, the mythic world of Rome was more sparsely populated than its Greek equivalent with such intermediate categories between gods and men as ‘nymphs’ and ‘heroes’, it did incorporate men, such as Romulus, who became gods; the Roman ritual of triumph involved the impersonation of a god by the successful general; and in the Roman cult of the dead, past members of the community shared in some degree of divinity.74 There was no sharp polarity, but a spectrum between the human and the divine. Throughout the late Republic the status of the successful politician veered increasingly towards the divine end of that spectrum. Caesar, in some senses, represented a culmination of this trend.

Rome’s political and military leaders had always enjoyed close relations with the gods. The logic of much of the display and debate discussed in earlier sections of this chapter (and in earlier chapters) was that magistrates and gods worked in cooperation to ensure the well-being of Rome; that the success of the state depended on the common purpose of its human and divine leaders. But there is another side to that logic: successful action, political or military, necessarily brought men into close association with the gods. So, as we have seen, in the ceremony of triumph the victorious general literally put on the clothes of Jupiter Optimus Maximus: in celebration of the victories that had been won through his cooperation with the gods, he slipped into the god’s shoes.75

But it was not as simple as that bare summary might suggest. The parade of any association between gods and men inevitably raised all kinds of questions: just how close was the association, for example, and how permanent? quite how literally was it to be taken? The story of the slave at the triumph constantly reminding the general that he was a man (not a god), offers its own clear antidote to the outright identification of man and god that might be implied by some of the ceremony itself: for those who chose to hear them, the slave’s words effectively stated that this was a general dressed up as Jupiter, acting, playing a part, not a general to be identified with, indistinguishable from, his divine model. Besides, even if for some the identification of man and god went closer than that, the triumph was by definition a temporary state; if the general stepped into Jupiter’s shoes, it was just for a day.76 Much the same was true for office-holding itself in the practice of the early and middle Republic. Magistracies and military commands were, by definition, temporary – held according to traditional practice for just a year at a time; if they brought their holders into proximity with the gods (even if not the extreme proximity reserved for the triumph), that proximity did not last long.

The late Republic set a new pattern of dominance, breaking with those earlier conventions. As the great political leaders of the age increasingly managed, by the repetition and extension of offices and by series of special commands, to exercise power at Rome for long periods, in some cases almost continuously, so they came to claim long term association with the gods. Sometimes adopting the symbolism of the triumph, sometimes using other marks of proximity to the divine, they displayed themselves (or were treated by others) as favourites of the gods, as like the gods, or ultimately as gods outright. So, at least, one version of the background to Caesar’s deification would run.

Already by the late third or early second century B.C. there are clear hints of the divine elevation of powerful political and military figures. We have already seen, for example, the close association that Scipio Africanus claimed (or was accused of claiming) with Jupiter Optimus Maximus.77 A little later Aemilius Paullus, after his victory over the Macedonian king Perseus at Pydna in 168 B.C., is said to have been granted not only a triumph, but also the right to wear triumphal dress at all Circus games.78 We should think very carefully about what this honour was, and what it might signify. Paullus was allowed to dress in the costume of Jupiter, with purple cloak and crown, and reddened face just like the statue – and so to appear at these regular public (and religious) gatherings of huge numbers of the Roman people. Maybe the fancy dress would have gone unnoticed; or maybe many of the participants would have been struck (impressed, outraged...) by the presence of their general-as-Jupiter. But, however it was perceived, this honour for Paullus must represent an important break with the temporary honorific status conferred by the traditional triumphal ceremony – extending its association of man and god beyond the moment of the ceremony itself. It was to be an honour granted again to Pompey in 63 B.C.79 and later, with even further extensions, to Caesar: the dictator was allowed to wear such costume on all public occasions.80

The leading political figures of the last decades of the Republic displayed (or were popularly granted) other marks of assimilation to the gods. This never amounted to a ‘formal’ decree of recognition as a god (like that granted to Caesar after his death, when he became officially divus Julius); but nevertheless the distinctions between some of the leading figures in the state and the gods were increasingly blurred. The political dominance of Marius, for example, seven times consul and triumphant victor over the renegade African king, Jugurtha, and over the Germans, was matched by his religious elevation. Not only did he go so far as to enter the senate in his triumphal dress – a display of religious and political dominance amongst other members of the élite from which he was forced to draw back; but after his victory over the German invaders he was promised, by the grateful people so it is said, offerings of food and libations along with the gods.81 This kind of outburst of popular support for a favoured political leader was no doubt temporary and informal (to the extent that it was sanctioned by no official law or decree); it also had earlier precedents – in, for example, the brothers Gracchi, who had received some sort of cult after their deaths at the places where each had been killed.82 But Marius seems to have set a pattern of cult for the living. Fifteen years later, in 86 B.C., the praetor Marius Gratidianus issued a popular edict, reasserting the traditional value of the Roman denarius, and was rewarded ‘with statues erected in every street, before which incense and candles were burned’. It may be significant that Cicero connects these divine honours with the independent action of Gratidianus in issuing the edict in his own name, without reference to his colleagues – so directly linking divine status with (claims to) political dominance.83

Association with the gods could also be seen in the form of the protection or favour that a politician might claim from an individual deity. Venus, in particular, ancestor of the family of Aeneas (and so by extension of the whole Roman people) became prominent in the careers of several leading men of the first century B.C. Such divine protection was in itself a relatively modest claim (compared with some of the honours we have just been considering). But this parade of divine favour developed, particularly in the hands of Pompey and Caesar, into a competitive display of ever closer connections with the goddess.

At the beginning of the first century B.C. Sulla, the dictator, claimed the protection of Venus in Italy and of her Greek ‘equivalent’, Aphrodite, in the East. He advertised this association not only on coins minted under his authority, but also in his temple foundations and in his dedication of an axe at Aphrodite’s great sanctuary at Aphrodisias in Asia Minor – apparently following the goddess’ appearance to him in a dream. But Sulla’s titles too incorporated his claims to her divine favour. In the Greek world he was regularly styled Lucius Cornelius Sulla Epaphroditus, and in the West he took the name Felix as an extra cognomen – a title which indicated good fortune brought by the gods, in this case almost certainly by Venus.84