7 Roman religion and Roman Empire

What was the impact of Roman religion on the provincial communities of the Roman empire? We have already discussed the spread of so-called ‘oriental religions’ outside the city of Rome itself. But what of the ‘official’ cults? How far did the inhabitants of the empire acquire Roman religious identities? Was the impact of Rome strikingly different in different parts of the empire? Was it different at different periods? Or among different classes and groups of people? As we shall see, the historical development of imperial religion produced some remarkably idiosyncratic effects (the emperor Augustus, for example, depicted in traditional Egyptian style as a pharaoh offering cult to Egyptian gods), as well as some curiously ironic enigmas (as when the Roman governor of Egypt circulated the emperor Claudius’ message to the Alexandrians that they should not worship him as a god – with a covering edict calling him precisely that, ‘our god Caesar’).1 In what follows, we shall explore such representations as part of the operation of imperial power across the Roman world.

The point of this chapter is to show, first, that Roman imperialism did make a difference to the religions of its imperial territory; and, second, to explore how we might trace the impact of Roman religion outside Rome, principally in the period after the reign of Augustus. Of course military conquest and the imposition of foreign control (whether in the form of taxation, puppet government or military occupation) inevitably impacts on cultural life – both in the imperial centre and in the provincial territories. No one can be culturally unaffected by imperialism. But its impact comes in a wide range of forms, and is experienced very differently by the parties involved – whether conquering or conquered, peasant or aristocrat, the native resistance or the local collaborators. Imperialism is, besides, constantly re-interpreted in culture and religion, as we can see very simply in the different images of the emperor himself that are found throughout the Roman provinces – not just the relatively standardized portraits on the coins that flood the Roman world, but the (to us) almost unrecognizable images from Nile sanctuaries with the emperor in the distinctive guise of Egyptian pharaoh or Ptolemaic king. Religion and culture are regularly put to work on imperialism’s behalf, incorporating the conquering power into local traditions. But at the same time religion and culture may always work against imperialist power, in reasserting the distinctiveness of native traditions against the forces (whether military or cultural) of occupation. It is a plausible suggestion that ‘native’ rebellions in the Roman empire tended to fight under the banner of local deities.2

Within these different perspectives, we shall delineate some of the most characteristic features of Rome’s religious impact on the empire. Rome did not generally seek to eradicate ‘native religious traditions’ nor systematically to impose her own religious traditions on her conquered territories. (Roman religion’s identity as a ‘religion of place’ – strongly focussed on the city of Rome – would anyway make unlikely any wholesale direct export.) On the other hand there was borrowing and interchange at various levels between Roman cults and religious practices through the empire; Roman gods, for example, or at least (and this may not be the same thing at all) gods with Roman names, were widespread across the imperial territories, throughout our period. But such borrowing was not the same everywhere, from Scotland to the Sahara. We shall disentangle some of the factors which affected the impact of Roman religion on the world outside Rome, and how that impact was experienced. These factors include formal political rights and privileges (communities of Roman citizens outside Rome being much closer to the religion of Rome itself than non-citizens), as well as wealth and class (local élites in the provinces showing greater interest in ostensibly Roman deities than their poorer compatriots). But we shall also consider how different religious and cultural traditions in the conquered territories affected patterns of ‘Romanization’: the Roman authorities treated the Jews, for example, differently from the Druids; while the western part of the empire, with only a limited history of urban culture on the ‘classical’ model, imported Roman institutions, (whether willingly or not) more directly than did the eastern part; there, by contrast, Greek civic life and cults often worked towards the accommodation of Rome; there, the Roman conquerors found religious traditions that they recognized as already like their own, or even as the ancestors of their own.3

All these factors (and others, as we shall see) intersect – and sometimes conflict – to produce the complex pattern of Rome’s religious influence on its empire. In section 1, however, we concentrate on the legal status of the different provincial communities and their constitutional relationship with Rome. In one sense influence literally radiated from Rome: it was strongest in Italy itself and in the camps of the Roman army, wherever it was stationed; elsewhere it was felt in proportion to the official Roman status of the town or group concerned, and their formal links to Rome itself. If some Roman pressures were exercised everywhere, the particular legal status of the community made a fundamental difference to its religious life. Let us explain first how these statuses differed.

Throughout the first two centuries A.D. (until, that is, the emperor Caracalla completed the restructuring of such distinctions by granting citizenship to most of the free population of the empire) there were three principal types of provincial community under the empire: coloniae, municipia, and towns without any specifically Roman status at all. Roman coloniae were, with the army, the main context in which the Roman religious system was replicated abroad.4 Coloniae were communities of Roman citizens settled outside Italy. In the middle Republic they were mostly landless citizens from Rome itself, and in the first centuries B.C. and A.D. mostly ex-legionaries who received land in return for their military service; these foundations ceased altogether after the early second century A.D. They were designed to be clones of Rome in all respects: Latin was the official language, even when they were established in the Greek world; some coloniae made a point of boasting ‘seven hills’, just like Rome. So too, in their religious institutions, these ‘mini-Romes’ abroad explicitly mirrored the institutions of the capital.

In the Latin west (especially in North Africa, Spain and Southern France) there was also a second category of towns with Roman status, known as municipia.5 These towns had been granted the so-called ‘Latin right’ by the Romans, which meant that individual members of the community gained some of the rights of Roman citizens and their ex-magistrates automatically became full citizens. It seems that when they received this status the new municipia also received a new constitution directly from Rome. After Vespasian granted the Latin right to towns in Spain, these municipal constitutions were standardized (under Vespasian’s son, Domitian); fragments of seven copies of the standard municipal regulation survive from Spain which clearly show the direct influence of Roman practice on institutions outside Rome.

Communities without Roman status fell into two main types: towns in the East, whose principal language was Greek, and whose own ancient religious traditions were deeply embedded in the fabric of urban life; and towns without municipal status in the West, often of much more recent foundation, in areas that were themselves more recently conquered, or without a long history of loyalty to Rome. Both these types of community (though much more commonly and directly those in the west) borrowed elements from the Roman system, though less directly than coloniae or municipia; and their religious institutions might be subject to Roman regulation. We shall discuss the religious impact of Rome on communities without Roman status in section 2.

Of course, as we have already implied, juridical status – even if a useful starting point – was not everything. The adoption and adaptation of Roman religious custom by local communities depended on much more than constitutional position (and on more, for that matter, than any of the other factors that we have so far mentioned): individual interests within the province, local perceptions of cultural and religious identity, calculations of advantage, no doubt, in relation either to the Roman government or the ‘native’ élite, or both. Besides, the religious practice or beliefs of individuals might always (as at Rome itself) go against the grain of the regulations laid down for the community as a whole. Just as there must have been some individuals in municipia or coloniae who lived in a resolutely non-Roman religious world, so too in towns without any formal Roman status, there must have been some whose religious experience was in many respects Roman.

The religious history of other empires may also help us at the outset to understand the pattern of religious influence in the Roman empire. The religious impact of the centre in the periphery of empires varies greatly, often depending on how integrated the empire is (a theme we touched on in chapter 5). In some cases the central power makes stringent religious demands on its dependent territories. This is particularly clear, for example, in the highly integrated Inca empire (where the nobility directly administrated their provincial territories and there were strong reciprocal obligations between rulers and subjects). Significantly, the Inca transported the images of the major gods of the vanquished to their capital and, in return, the subjects were compelled to accept new, Inca, idols and to maintain places of worship in the same manner as in the capital. A hostile contemporary account claims that the eleventh Inca king killed all priests of the subject peoples and destroyed even their less important shrines – because the priests had refused to give him information. At all events the Incas attempted to create a tightly centralized system, of administration and religion.6 Likewise, in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the massive overseas expansion of Japan was accompanied by the export of state Shintoism: shrines were built, for example, in Formosa, Korea and Manchuria, not just for the Japanese residents overseas, but as part of a new-found ‘world civilizing mission’.7 This is a model not far different from the British empire, which also attempted to impose its own religion (Christianity) on its colonies and to eradicate ‘unacceptable’ or ‘uncivilized’ native religious practices, though unsystematically, with varying energy and many varieties of self-deception and chauvinism.8

The Roman empire, on the other hand, operated according to a quite different pattern. In general, it was relatively diffuse and unintegrated – neither systematically imposing its own cults on the conquered, nor systematically removing the cults of their subjects to the capital.9 But, as we have already implied, one aspect of integration was particularly important within the vast geographical and political extent of the Roman empire: that is, Roman citizenship. The bearers of Roman citizenship were, it seems, expected to recognize Roman gods; an expectation which overlaps neatly with the juridical status of the different communities we have outlined (from coloniae as full citizen communities to towns without Roman status, which might have included no Roman citizens at all). Despite increasing religious choices in the imperial period, the identity of religion and state was maintained: those who counted as ‘Roman’ in civic terms counted as ‘Roman’ in religious terms too.

In exploring these issues, we shall consider the process by which local and Roman gods apparently merged with each other and were often referred to, and presumably worshipped, under a composite title. In Roman Britain, for example, as in many other provinces in the West, we find a wide variety of these hybrids, ‘Mars Alator’, ‘Sul Minerva’ and so on.10 In most cases, however, we have only the record of a mixed divine name; we can only guess what that name meant, which deity (Roman or native) was uppermost in the minds of the worshippers, or whether the two had merged into a new composite whole (a process often now referred to as ‘syncretism’); we do not know, in other words, how far the process was an aspect of Roman take-over (and ultimately obliteration) of native deities, how far a mutually respectful union of two divine powers, or how far it was a minimal, resistant and token incorporation of Roman imperial paraphernalia on the part of the provincials. Signs of ‘syncretism’, then, always need to be interpreted. For example, to understand why most deities in the eastern part of the empire did not merge with Roman counterparts, but retained their individual personalities and characteristics, whereas in the west pre-Roman gods acquired Roman names, or non-Roman and Roman divine names were linked, we need to investigate much more deeply the nature of Roman religion outside Rome; we need also to attend to the agenda of all those groups involved in developing a new Roman imperial world view – throughout the empire and over the centuries.11

Another theme, central to this chapter, is the ‘imperial cult’ offered to the Roman emperor or his (deified) predecessors, with temples, festivals, prayers and priesthoods in every province of the empire. The historian Cassius Dio in the third century A.D. saw cult of the emperor as one unifying factor in the religions of the vast imperial territory, one aspect of worship that all Roman subjects shared. After noting the establishment of temples to Augustus in Asia and Bithynia, he goes on to say: ‘This practice, beginning under him, has been continued under other emperors, not only among the peoples of Greece, but also among all the others insofar as they are subject to the Romans.’12 We have chosen to consider various aspects of imperial cult together in section 3 partly because of Dio’s claim of its universality across the Roman empire, and his suggestion that this form of shared religious practice was one aspect of ‘belonging’ to that empire. On the other hand, we do not want to suggest (and Dio comes nowhere near claiming) that there was a single entity, the same throughout the empire, that can be identified as ‘the imperial cult’. There was no such thing as ‘the imperial cult’; rather there was a series of different cults sharing a common focus in the worship of the emperor, his family or predecessors, but (as we shall see) operating quite differently according to a variety of different local circumstances – the Roman status of the communities in which they were found, the pre-existing religious traditions of the area, and the degree of central Roman involvement in establishing the cult. Besides, there was no sharp boundary between imperial cult and other religious forms: the incorporation of the emperor into the traditional cults of provincial communities, his association with other deities, was often just as important as worship which focussed specifically and solely on him. Nor was imperial cult necessarily the most powerful marker of Romanization in religion: in specifically Roman communities abroad (coloniae and municipia), imitations of the transformed system of Augustan Rome were often a far more important aspect of religious Romanization than any direct worship of the emperor.

The sources for this chapter are different in their emphasis from those we have used before.13 In attempting to reconstruct provincial viewpoints on the processes of Romanization in the provinces, we have ample evidence from one section of the provincial population only – the educated writers from the Greek world in the first two centuries A.D., some of whom (like Plutarch and Lucian) discuss various aspects of Greek and Roman religion and their interaction.14 Otherwise the bulk of the evidence for Roman influence on religion in the empire comes from inscriptions or from visual images: sculptured reliefs depicting gods or emperors, for example, may provide evidence for the native or Roman characteristics of a particular deity, or for how an emperor is imagined within the divine system; inscriptions reveal the names of the gods, the religious offices and sometimes the particular rites of towns in Italy and the empire. But at the same time these objects may challenge interpretation. How can you tell, for example, if a statue of Jupiter found in a provincial town is the result of Roman imposition or of enthusiastic provincial imitation of Rome? How can you know whether a temple to Roman deities in a distant province was the focus of loyal worship by the provincial community or the focus of their resentment at Rome’s dominance? Besides, it is all too easy to patronize provincial aspirations and ideology. Is a rough, ‘unclassical’, Celtic image of a Roman deity to be written off as a demonstrably naive failure by the local craftsman to reproduce metropolitan style? Or is it motivated by a desire to assert local, ‘tribal’ difference from the dominant, imperial, classical culture?

This chapter emphasizes the changes wrought under Roman rule; so we pay little attention to the relatively unchanging civic cults of the Greek east that continued throughout the period. Yet especially in the west, but also in parts of the near east, the evidence for pre-Roman religious life is very scanty – with few, if any, surviving pre-Roman inscriptions, and few if any images carved in stone, let alone any trace of literary accounts.15 It is often impossible, then, to specify precisely the individual changes brought about by Rome and Roman influence. We can, however, deploy the evidence we have to assess the overall impact of Rome on the religious life of the empire, and the factors which intensified or diminished that impact – both east and west, from the classical world of the Greek city states to the tribal societies of Britain and Gaul.

1. Roman religion outside Rome

Throughout the empire the Roman authorities tended to promote a variety of Roman religious practices. Whatever differences there were in the impact of Rome, it was a general rule that governors and other Roman officials favoured Graeco-Roman (rather than ‘native’) gods in whichever province they were stationed, and the governor’s staff regularly included haruspices for the proper interpretation of sacrifices performed on the Roman model. Even more important was the expectation that governors right across the empire would ensure that the provincials, presumably in the context of the provincial assemblies (which consisted of representatives of the individual towns), performed the annual vota (vows followed by sacrifice) for the emperor and the empire.16 Evidence for this is widespread: the practice was recorded by the Christian writer Tertullian in North Africa; coloniae in southern France and Dacia offered vota; a town in Portugal made a dedication to the emperor as a result of the annual vow.17 Even rabbis in Palestine noted the prevalence of the practice; and Greek cities too sacrificed annually ‘on behalf of the emperor’ – even though such ‘vows’, in the technical sense of promising a sacrifice if something did (or did not) happen, were a peculiarly Roman practice in the context of public civic sacrifices.18 These vota were in fact an institution common to all types of provincial community – which is particularly striking given that, as we shall see, communities of different statuses and culture had very different relations to Roman religion.

On the other hand, Roman provinces were not Rome; and the religious rules governing practice in Rome itself did not apply directly elsewhere in the empire. Instead Roman authority was mediated through the governor, according to similar – but not always exactly the same – principles as operated in the city. So, for example, according to Roman lawyers, land in the provinces could not, strictly speaking, be religious or sacred as it was not consecrated by the authority of Rome; it could only be treated as religious or as sacred.19 But inevitably such legal rules were not always a clear guide to religious practice. The problem of the two categories of land faced Pliny when he was governor of Pontus-Bithynia. In relation to religious land (used for burials) he asked the emperor, as pontifex maximus, whether he could permit people to rebury the bodies of their relatives which had been disturbed by river erosion. Trajan replied that provincials could not be expected to consult the pontifices, and that local custom should be followed.20 Despite Pliny’s uncertainty, in the provinces emperor and governor filled the role occupied in Italy by the pontifices. On another occasion, Pliny wrote to the emperor about sacred land. He enquired whether it was religiously proper for the town of Nicomedia to move a temple, though, to his surprise, there was no ‘law’ which laid down the location of the temple or other conditions applying to it – in Roman terms, that is, no ‘law of dedication’, laying down the location and other conditions of the temple. Trajan pointed out that only Roman and not foreign territory could receive such a law.21 The actual Roman rules did not apply to ordinary provincial land, but governors were told firmly in the instructions (mandata) issued to them by emperors to preserve sacred places.22 The role of the governor included supervision of religious matters along essentially Roman guidelines.

For the rest of this section, however, we shall be concentrating on the different legal and constitutional statuses that affected how the influence of Rome was felt in different communities. We shall explore Rome’s control over the religious practices of the empire and the adoption of Roman religious practices outside the city in a sequence moving out from Rome: Italy, the army, and provincial communities with Roman status, coloniae and municipia. All these, with the partial exception of municipia, consisted of Roman citizens, and all held some consistent patterns of religious practices in common. At the same time we shall show the hybrid complexities that cut across this relatively simple pattern: the very different forms of accommodation with Rome that were attempted even by communities of the same constitutional type; the different significances that could attach to the ‘same’ religious institutions, rituals and symbols.

Italy formed the core of the empire. All the free-born population of the peninsula up to the Alps had been Roman citizens since the time of Julius Caesar. Italy was not a ‘province’ (it was not, for example, subject to Roman taxation); but remained, in principle, a collection of self-governing communities. Some towns preserved their religious institutions from pre-Roman days, including practices utterly at variance with Roman traditions – burying their dead within the city limits, for example, which was strictly prohibited at Rome.23 However, at least when it suited them, Roman officials did claim authority over the religious institutions of Italy. This is neatly illustrated by an incident under Tiberius, when the equestrian order in Rome vowed a gift to ‘the temple of Equestrian Fortune’ for the health of Livia, only to discover that there was no such shrine in Rome itself. But such a temple was discovered at Antium, a town fifty kilometres south of Rome, where (according to Tacitus) the senate decided that the gift could be placed, ‘since all rituals, temples and images of the gods in Italian towns fall under Roman law and jurisdiction’. Neither the senate nor any other group of Roman officials did actually exercise day to day control of Italian shrines; but in this case at least it was convenient (and presumably seemed plausible) for them to stake a theoretical claim to Roman power over the religious institutions of the rest of the peninsula. Likewise when the Roman authorities moved to expel undesirables from the city, they normally specified expulsion from both Rome and Italy. The Roman college of pontifices also sometimes gave permissions to Italians to repair tombs or move corpses from one tomb to another, and, soon after the death of Julius Caesar, a Roman law seems to have instructed Italian communities to set up statues of divus Julius. Of course, in practice many Italians must have repaired tombs without the permission of the Roman priests, and we do not know how many obeyed the order to erect statues of Caesar; but in both these cases the parade of Roman authority over the peninsula as a whole is significant.24

The uniquely close relationship between Rome and the rest of Italy is visible most clearly in a series of documents we have already discussed from different points of view in earlier chapters: the surviving painted and inscribed calendars of festivals. In all, forty-seven such calendars survive (often in small fragments), dating mainly to the reigns of Augustus and Tiberius, and all but one coming from Italy (the exception being a colonia in Sicily).25 Of these forty-six imperial Italian calendars, twenty-six are from Rome itself (many, it seems, having been for the use of private associations in the city); the other twenty come mostly from the towns in the vicinity of Rome – generally on public display in the civic centres of the towns concerned.26 The level of detail given in the Italian calendars varies greatly, but all differ from and apparently replace earlier, pre-imperial, Italian calendars and all are mutually compatible, recognizably versions of the same overall system of religious time-keeping. Strikingly they give practically no festivals peculiar to the local city, but only differing selections from the official festivals of the city of Rome. This raises acutely the question of the relationship between the calendar and religious practice. Would it really have been the case, for example, that such rituals as the Lupercalia, so closely tied to the topography of Rome, would have been celebrated in all the Italian towns that chose to mark it on their calendars? And if it was not celebrated, then what function did those calendars have? Why display in the local forum a series of festivals that your own town did not actually carry out? However we choose to answer such questions, it is clear that some towns in Italy – and this seems not to have been the case in the provinces – chose to parade the official Roman religious calendar as (or as if it were) the framework for their own lives.27

Some of the religious links between Rome and the Italian towns derived directly from historical links in the distant past. The ancient communities nearest Rome, for example, had been Rome’s ‘Latin’ allies in the early republican period and shared a variety of common cultural forms stretching back almost into prehistory and to Rome’s status as a ‘Latin’ city. Thus Alba Longa, Lavinium, Tibur and other Latin towns had one or more of the following priests: flamen Dialis, Vestal Virgins, rex sacrorum, and Salii.28 The Salii and the rex sacrorum (and, once, the flamen Dialis) are also found in a few towns in northern Italy, but otherwise these offices appear almost nowhere else in the Roman empire, except in Rome itself. Interpretation of this common culture could vary, of course. In those early days the religious influence did not necessarily flow from Rome outwards; and some Italian communities might choose to give themselves (not Rome) priority in the relationship – suggesting that if they shared some of Rome’s most distinctive practices, that was because Rome had adopted them from the Latins, not the other way round. A shared religious history, in other words, could be the focus of rivalry and conflicting interpretations.

But historical links could also be invented. In the early empire, ancestral ties between the Latin towns and Rome were emphasized by a new flowering of such (allegedly) ancient cults. For example, at Lavinium 30 km south of Rome, where there was no settlement in the late Republic, Italians of equestrian rank from the reign of Claudius on held a priesthood which supposedly continued the cult of the Lavinian Penates (the deities that Aeneas had brought from Troy), participating at ceremonies of the Latin League on the Alban Hill, and, on one occasion at least, renewing the ancient treaty with Rome, first made in the fourth century B.C.29 In the second century A.D., after the renewal of civic life at Lavinium, local men from the town began to hold the office, which is attested until the middle of the third century. This is a case of ancestral similarities between the religious practices of Rome and Italy being re-emphasized in the early empire through what was almost certainly an invented tradition. For some observers and participants, no doubt, it was all a picturesque, quaintly antiquarian show; but such instances of constructive archaism also served as another way of representing the religious links between Rome and its Italian neighbours.

Outside Italy, the body of men which most clearly stood for Rome was the army. In the professional standing army, established for the first time under the emperor Augustus, Roman citizenship remained a precondition for service in the legions (though it might be granted at recruitment); they were gradually recruited from a wider and wider area, so that, by the early second century A.D., they had only a tiny proportion of men from Italy itself – but the rules of citizenship governing recruitment continued to emphasize that the men were troops in the service of Rome. The other main body of troops, the auxiliaries, were not Roman citizens in the early empire, though they were commanded by officers who were citizens and they themselves might receive citizenship on discharge; later it became not uncommon for those who were already Roman citizens to enlist in the auxiliary forces. The official religious life of both sets of troops was predominantly Roman; though that could mean different things and be interpreted in different ways.

The specifically Roman character of official religious life in the army was enshrined in an official Roman calendar which specified the year’s religious festivals for both legionaries and auxiliaries; this was different in form from the civic calendars of Italy we have just discussed, but (crucially, as we shall see) shared some of their major celebrations. The archives of an auxiliary cohort, the ‘Twentieth Palmyrene’, stationed at Dura Europus on the eastern Euphrates frontier, included a papyrus copy of this calendar which still survives.30 The calendar was written in Latin, the official language of the army, and in neat capital letters throughout. This particular copy obviously received considerable use before it was discarded; the frequent rolling and unrolling of the papyrus had distorted the original shape of the roll and two patching jobs had been necessary. It was certainly not just an official ordinance kept in the files and ignored.

The festivals to be celebrated by the cohort demonstrate how the restructured religious system of Augustan Rome was, in a modified form, repeated in the army. First, some of the major festivals of Rome (the Vestalia, for example, or the Neptunalia) were marked on the appropriate day by a sacrifice in the army camp too; so too were the circus games established in Rome by Augustus in 2 B.C. at the dedication of the temple of Mars Ultor. The ‘Birthday of Rome’ also appears, presumably added to the calendar under Hadrian, to replace an earlier celebration of the Parilia (as we saw in chapter 4). A second group of celebrations honours the reigning emperor, his family and predecessors. The deified emperors and empresses whose birthdays were celebrated by the army seem to correspond exactly to those whose birthdays were celebrated at this time by the Arval Brothers at Rome, marked in their inscribed record; that is, the cohort’s calendar was in step with at least one version of official practice in Rome. And on 3 January vows were taken for the well-being of the emperor and the eternity of the Roman empire, with sacrifices to the Capitoline triad – again in accordance with practice at Rome itself.31

The forms of ritual prescribed for the army unit were also the same as those performed in Rome – including (as in state cult) both animal sacrifices and offerings of wine and incense (supplicatio). The rules for animal sacrifices were also for the most part identical to those followed in the capital: male deities were offered male victims, and female ones, female victims; Mars received a bull, as was standard; the genius of the emperor received a bull and the divi received oxen. The overlap with the Arval record is again striking: the military calendar even used the same abbreviations for ‘ox’ (‘b.m.’) and ‘cow’ (‘b.f.’) as the Arval Brothers, abbreviations which are not otherwise attested outside Rome. On the other hand, there were a few differences too. At Dura deified empresses (divae) received only supplicationes, not cows in sacrifice as in Rome.

Of course, both officers and men also worshipped other gods, apart from those honoured and listed in the calendar. We have already noted, for example, the popularity of Mithras in the Roman army. There was, in fact, a temple of Mithras at Dura which was used by soldiers – although no mention is made of the god in our document; and we shall return below to other examples of the varied religious life of a military unit. Presumably this calendar was not intended to regulate the private religious worship of individual soldiers; rather it formed the basis of the official cycle of ceremonies carried out by (or on behalf of) the cohort as a whole, as a Roman institution. Although the Dura calendar is the only surviving example, it is a fair guess that all army units possessed, and in principle followed, a ritual calendar on this model – which may, in fact, with alterations and adaptations, go back to a calendar first issued to the legions under Augustus himself. Rome, in other words, made a version of its own religious system the basis of the religion of the Roman army.

This guess is supported by a variety of evidence suggesting a common basis to the official religious activity of army units. There is certainly a good deal of material to show that the gods and festivals recorded in the Dura calendar did recur in other military contexts throughout the army.32 For example, from the Roman fort at Maryport, just south of Hadrian’s Wall, a series of 21 altars and plaques survives officially dedicated to Jupiter Optimus Maximus in the course of the second century A. D. by three different regiments, perhaps on 3 January when vows were made ‘for the well-being of the emperor and the eternity of the empire’. Or again, at another fort near Hadrian’s Wall (the third century A.D. legionary supply base at Corbridge) we can see the traces of the rituals that the legion’s official calendar prescribed, even though we do not possess any written version of the document itself. Inscriptions and carvings from Corbridge attest many of the cults known in the Dura calendar: Jupiter, Victoria, Concordia; and the ‘rose festival of the standards’, which appears twice in the Dura calendar, is depicted there on a decorative relief which probably formed part of the shrine for the standards. The specifically Roman focus of the legion’s official religious activity is further attested by a shrine in the base which clearly evoked the foundation of Rome: a relief carving on the pediment showed the wolf suckling Romulus and Remus, This scene was repeated in another camp halfway across the empire: an early third-century inscription from a fort on the Danube refers to the dedication of a signum originis, that is a statue of the wolf with Romulus and Remus.33

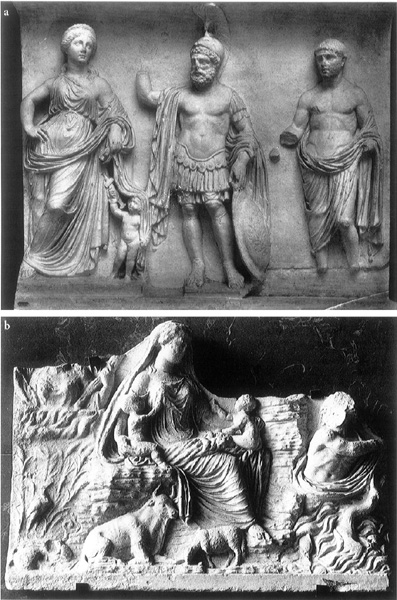

In general the arrangement and personnel of army camps throughout the empire conformed to the system implied by the Dura calendar.34 In the centre of the camp, at the rear of the headquarters building, was the shrine which housed the legionary standards and imperial and divine images. This shrine is actually called a Capitolium on one inscription.35 In front of the headquarters building was a platform where the commander took omens from the flight of birds. The army had on its staff specialist religious personnel: the victimarii, who killed the animals, and the haruspices, who took the omens from the animals’ entrails. Scenes of military sacrifice, on exactly the standard Roman pattern and attended by the appropriate specialists, are depicted on reliefs from Trajan’s column in Rome (in scenes from Trajan’s campaigns in Dacia, modern Romania) and from the Antonine Wall in Scotland.36 (Fig. 7.1) This re-enactment of the most central and characteristic ritual of Roman official religion was one of the most striking ways in which the army paraded that religion across the known world; in the case of Trajan’s column, that diffusion was then monumentalized in Rome itself, displaying in the very centre of the city the Roman army ritually enacting their ‘Romanness’ on the frontier.

Fig. 7.1 A scene from Trajan’s column showing the ritual purification of the Roman army, before an assault on the Dacians. A bull, sheep and pig – to form the sacrifice known as suovetaurilia – are led in procession round a Roman camp and in through a gate; they are followed by the victimarii (shown semi-clad) whose function was to perform the killing of the victims. Within the camp the emperor Trajan, head duly veiled, pours a libation over an altar in front of the standard-bearers. (Height, c. 0.80m.)

The official prescription of Roman gods did not, however, prevent the worship of other gods. After all, by the second century A.D., most Roman soldiers came from places other than Rome and Italy and may well have wished to maintain their original identity within a Roman framework; their religious interests must have been as cosmopolitan as those of any group of ‘Romans’. For example, an auxiliary cohort from Emesa in Syria, which was raised in the 160s and served for a long period (from the later second to the mid third century A.D.) in Pannonia on the Danube frontier, maintained a dual allegiance to Roman and to Syrian gods, to Jupiter Optimus Maximus and to Elagabalus.37 This was not just a matter of individual devotion. Both gods were worshipped officially by the cohort as a whole as well as by individual officers and men. In contrast, the civilian community outside the camp honoured neither Jupiter Optimus Maximus nor Elagabalus, but a variety of local and other gods.38 By the second century most soldiers served close to their homeland (the distance of the Emesene cohort from their native territory was unusual in this period), and soldiers and even high-ranking officers sometimes made offerings to local deities.39 This must have made it easier, for those soldiers who wished, to maintain all kinds of ‘native’ traditions of worship. But even so the dominant religious system of the army as an institution remained modelled on that of Rome.

After the army, it was Roman coloniae that mirrored the religious institutions of Rome itself most closely. This is clearly illustrated by the regulations for the colonia founded by Caesar in 44 B.C. at Urso in southern Spain that we noted in chapter 3. The surviving copy of the regulations is a re-inscription of the original rules, dating from the late first century A.D. – effectively reaffirming the peculiarly Roman nature of Urso more than a century after its foundation (perhaps to maintain her superiority over other Spanish towns which had received the ‘Latin right’).40 This Roman character is evident in almost all the regulations for the life of the colonia, but is particularly striking in the detailed, and well-preserved, clauses of the document that refer to priesthoods. As we saw, the two main priestly groups were pontifices and augures; and ‘as at Rome’ (the regulations specifically refer to the model of Rome) the priests were to be free from military service and public obligation; they also had the right to wear special clothes at games and sacrifices and to sit at games in the same privileged seats as the town-councillors. Their functions too were similar to those of their Roman prototypes: the augures, for example, were to have jurisdiction over the auspices and all matters concerning them.41

Much the same priestly organisation and duties are found in all other coloniae. As late as A.D. 322, some 200 years after it had become a colonia, an embassy from Zama Regia in north Africa to the governor consisted of ten men, of whom the first named were the four pontifices and two augures; similarly, at Timgad (also in North Africa), over 250 years after the foundation of the colonia, the council included the four members of the colleges of pontifices and augures as well as other priests of the cult of the emperor.42 An inscribed altar from the colonia of Salona (on the eastern Adriatic coast) gives a glimpse of a local pontifex at work: the inscription records that at the dedication of the altar a pontifex dictated the words to the local magistrate – just the procedure that was adopted at Rome.43 Of course, local priestly functions could never be exactly identical to those in the capital: the authority of both pontifices and augures, for example, was restricted by that of the governor (who himself had the right to authorize the moving of corpses – in Rome a pontifical responsibility). But overall the symbolic structures of coloniae emphasize their status as ‘mini-Romes’ from the very moment of their foundation, conducted with rites that echoed the mythic foundation rituals of Rome itself: the auspices were taken and – like Romulus in the well-known myth – the founder ploughed a furrow round the site, lifting the plough where the gates were to be;44 within this boundary, which replicated the pomerium of Rome, no burials could be made; the land within the pomerium was public land which could not be expropriated even by the local council.45

Much of this similarity is due to direct Roman initiative. The original religious regulations for the coloniae and the form of their foundation rituals were devised by the Roman authorities; and coloniae in the late Republic and early empire may also have received specific instructions, directly from Rome, on the establishment of new Roman practices. Priests of the deified Julius Caesar (flamines divi Julii), who was officially deified at Rome, are found outside Rome only in Roman coloniae, in both the eastern and western parts of the empire. A relief honouring one such flamen in the colonia of Alexandria Troas in north west Turkey even shows the distinctive hat (apex) worn by flamines in Rome.46 The fact that this cult is found only in coloniae may suggest that they were responding to official instructions from Rome, issued perhaps in 42 B.C. when Caesar’s deification was finally ratified. Certainly in A.D. 19, when the senate passed a lengthy decree on the funeral honours for the emperor Tiberius’ son Germanicus, provincial coloniae were explicitly instructed to set up a copy, and their magistrates were barred from transacting public business on the anniversary of the death of Germanicus.47 At this period, coloniae were expected to move in step with Rome.

But even without direct instructions, throughout their history coloniae might themselves choose to follow, and parade, Roman models. This was clearly the case in the inscription from Salona, whose introductory formulae involving pontifex and magistrate we have just mentioned. What follows this introduction are the regulations governing the rituals at the altar (the ‘law of dedication’, which Pliny had wrongly expected to find in a non-Roman town):48 some of these are spelled out; for the rest it is stated that they ‘shall be the same as the law pronounced for the altar of Diana on the Aventine’. This ancient set of rules in the Aventine sanctuary in Rome originally governed the relations between Rome and her Latin allies.49 Here the colonia of Salona, some 170 years after its foundation, chose to adapt this model to articulate its own ritual rules and at the same time to emphasize its privileged relationship to Rome. Two other similar documents from Roman coloniae, one from Narbo in southern France, the other from Ariminum (Rimini) in Italy, refer to the Aventine model in framing their own cult regulations.50

How exactly the population of more distant coloniae gained access to the Roman ritual knowledge implied by these and other rules is unclear. It is certainly possible that in some cases they had very little access to that knowledge; and that Roman models were more of a display than a rule book to be followed to the letter. On the other hand, the governor’s staff and army units stationed in the provinces included Roman religious experts (haruspices and victimarii), who might have been able to offer advice on points of detail; so too might the governor himself.51 More puzzling, in fact, is the question of what general idea of ‘Roman religion’ (if, by that, we mean the religious institutions and practices of the capital) the population of such places would have had – who, though Roman citizens, might have been resident hundreds of kilometres from Rome for generations. One possible channel is Varro’s Religious Antiquities. This treatise, of the mid first century B.C., remained even under the empire the only general work on the Roman religious system. That provincials did turn to it for inspiration is suggested by the effective (polemical) use made of it by the Christian Tertullian, writing in north Africa.52 But even this book will have been hard going, and difficult to apply to particular local issues. The problem is a useful reminder, however, that any such statement as ‘the coloniae imitated the religion of Rome’ is always liable to be a shorthand for ‘the coloniae imitated their own image (or conflicting images) of the religious institutions of the capital’.

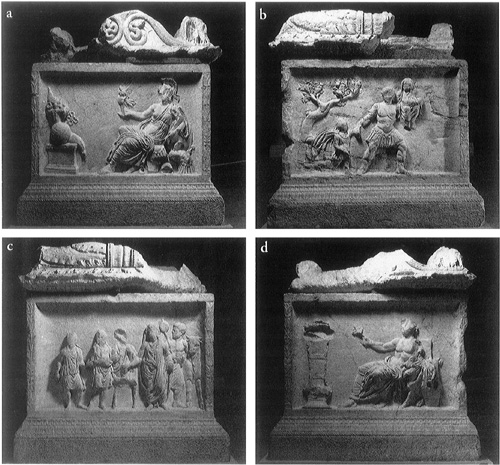

This is not to say that the population of a colonia was always in danger of ‘misunderstanding’ the religion of Rome; but rather that imitation of the religion of the capital must in practice always have been a creative process, involving adaptation and change. Two altars from the colonia of Carthage illustrate different ways in which images of (and derived from) Rome might be represented and constructively reinterpreted in a colonia. One, a grand public altar, of Augustan date, stood on the outskirts of the Augustan colonia. (Fig. 7.2) Two of its large sculpted panels survive. One represents Mars Ultor standing between Venus Genetrix and a figure probably to be identified with divus Julius. The other shows a seated female figure, with children in her arms, her lap full of fruit, animals at her feet. This figure is closely based on the scene of ‘Earth’ on Augustus’ Ara Pacis in Rome, though the personified breezes which flank the figure on the original monument have been replaced with a sea god (a Triton) and a female divinity carrying a torch.53 On the other face, the figures of Mars, Venus and (probably) divus Julius are almost certainly derived from statues (not necessarily cult-statues) from the temple in the Forum of Augustus; Mars and Venus are even represented on statue bases, marking them out as statues, not simply deities. It is likely that the altar was produced locally, in Carthage, though we do not know how knowledge of the Roman monuments was disseminated. That is, the colonia here, in its own religious monuments, was explicitly combining themes from two of the major Augustan buildings at Rome itself; with direct ‘quotations’ (as in the statues), adaptations (as in the new flanking figures for Earth, perhaps deities with a particular local relevance) and, of course, a wholly new juxtaposition of scenes. The colonia was expressing its own version of Roman identity, through a creative imitation of Rome itself.54

Fig. 7.2 Two reliefs from altar in Carthage. (a) Left to right: Venus, Mars; probably divus Julius, as strongly implied by the star on his forehead, rather than an Augustan ‘prince’. Mars must be Mars Ultor, the cult-image from his own temple in the Forum of Augustus (see 4.2a). If, as is now suggested (see Steinby(1993–) II.291–2 for discussion), the temple had only a single cult–image, then Venus and divus Julius must have been located elsewhere in Mars’ temple – as statues, but not cult-images. (Height, 0.98m; width, 1.13m.) (b) ‘Earth’, flanked by deities. For the Roman prototype, see fig.4.6. (Preserved height 0.80m., width 1.13m.)

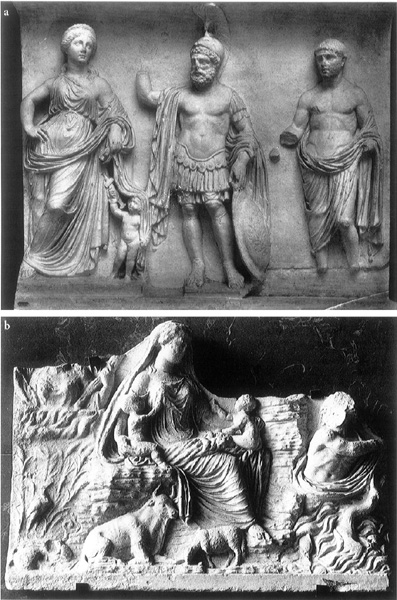

The second, and much smaller, altar was found close to an inscription recording the building of a temple to the Augustan family – by a wealthy individual (probably an ex-slave) at his own expense, on private land near the centre of the colonia; the donor (so the inscription also records) became perpetual priest of the new cult. Almost certainly the altar belongs to this temple, and dates to the last decade of Augustus’ reign.55 (Fig. 7.3) The scenes on the four sides of the altar again reflect central Roman themes. On the front is Roma, seated on her armour, with a miniature shield and winged victory on her outstretched right hand. The figure may be a version of the Roma (now very fragmentary) which balanced ‘Earth’ on one side of the Ara Pacis; but, if so, the altar with its globe and cornucopia in front of her must be adaptations of the original design; while the figure of Victory on her hand carries a shield modelled on the ‘Shield of Virtue’ awarded to Augustus by the senate.56 The scenes on either side of the altar show Aeneas leading Ascanius and carrying his father Anchises out of Troy (a scene immortalized in Virgil’s Aeneid, and represented in the Forum of Augustus);57 and sacrificers, who perform their ritual in the distinctively Roman manner with togas over their heads (perhaps recalling similar scenes on the Lares altars of Rome). Finally, on the rear of the altar, to match the figure of Roma, is Apollo (whose temple Augustus had built on the Palatine), seated in front of a tripod. This altar is also a creative juxtaposition of Augustan themes and images, Roma, Aeneas and Apollo, perhaps again influenced by specific monuments in the capital. In this case, the imagery particularly serves the interest of the donor, ineligible (as an ex-slave) for membership of the local council, but nonetheless here proudly asserting his position within the community and within the Roman imperial world. If indeed we read (as may be intended) the main officiant in the sacrificial scene as the donor himself, we see him displaying his own (Roman) piety within a version of imaginary Rome.

Fig. 7.3 Altar from Carthage. (a) Roma. (b) Aeneas carrying Anchises and leading Ascanius. (c) Sacrifice at an altar, (d) Apollo. (Total height, 1.18m.; width, 1.16m.; depth 1.03m.)

Imitation of Roman religion in the coloniae was, then, less rigid than the regulations we started with might have suggested. And although coloniae in general borrowed, sometimes closely, from Rome, there was no immutable blueprint. Different coloniae were Roman in very different ways and made different kinds of accommodation with the central imperial power. This is illustrated very clearly in their choice and layout of temples, and (particularly) in the varied distribution of Capitolia throughout the different coloniae.58 A Capitolium, in the sense of a temple of Jupiter, Juno and Minerva on the model of the Capitoline temple at Rome, provided a very clear link with the capital. Some coloniae certainly built Capitolia immediately at the time of their foundation: there are second-century B.C. coloniae in Spain with their own Capitolia, and the regulations from Urso specify major games in honour of the Capitoline triad (though we do not know if the town actually had a Capitolium).59 Other coloniae built Capitolia only later, if at all. The colonia of veteran soldiers at Timgad, for example, established in A.D. 100, did not include a Capitolium in the forum, where there was only a small temple which may have related to the emperor; and, when building of a Capitolium began circa A.D. 160, it was sited outside the original area of the colonia.60 The options were even wider when a colonia was not founded completely afresh, but when an existing town received some Roman colonists – and so took on the status of a colonia. For example, at Heliopolis (modern Baalbek in Lebanon), which lay in the territory of the colonia of Berytus, a great new civic temple was begun in the Augustan period when ex-soldiers were settled there. The basic design is Roman (with some local adaptations) and the expense of construction, plus the use of imported red Egyptian granite for the portico, strongly suggests financing from Rome, even from the emperor himself. But the name of the main deity, Jupiter Optimus Maximus Heliopolitanus, shows clearly how even the Capitoline god could absorb and display the influence of local culture and conditions.61

Towns with the status of municipia (where local citizens had the so-called ‘Latin right’ and some even full Roman citizenship) shared some of the Roman religious features of coloniae; their principal priesthoods, for example, were named after, and modelled on, Roman institutions –pontifices , augures and haruspices. And from the second century A.D. onwards municipia in north Africa also began to build their own Capitolia; Thubursicu Numidarum in Algeria, for example, which became a municipium after A.D. 100 (perhaps c. A.D. 106), dedicated a Capitolium in A.D. 113. A cult that in the first century A.D.had been confined to coloniae (and Rome itself) was taken over by municipia as part of their display of Roman status. But interestingly, that sequence may also be reversed; and on more than one occasion we can see the building of a Capitolium as part of a claim for Roman status (rather than a boast of Roman status already acquired). At Numluli, which lay in the territory of Carthage, some local citizens who had achieved high status in Carthage dedicated a Capitolium for the local Roman citizens and for the village itself. The building of the temple clearly displayed allegiance to Rome, but it was almost certainly a part of an attempt to gain the status of municipium for Numluli which it certainly later held. Similarly at neighbouring Thugga, which also consisted of a group of Roman citizens and a village in the territory of Carthage, a Capitolium was built at just the time that the group of Roman citizens was granted imperial permission to receive legacies; the building of the Capitolium, with its Roman-style cult of the Capitoline triad, was presumably intended to promote their recognition as an independent community.62 Roman religious institutions in the provinces were not merely reflections, then, of different levels of Romanization; they were also useful counters in the competition for prestige, honour and status that was one of the defining features of provincial culture across the Roman world.

Roman citizens did not, of course, live only in coloniae and municipia; even in the early empire, when Roman citizenship was a privilege virtually restricted to members of the élite, groups of citizens were found (as at Numluli and Thugga) outside communities with any formal Roman status. In many respects these citizens would have lived and worked indistinguishably from their non-citizen neighbours; but for some purposes they might have formed distinct groups within their non-Roman communities. The religious activity of these groups was, no doubt, one of the ways in which they re-affirmed and displayed their ‘Roman’ status; and at the same time it must have been one of the channels that spread specifically Roman religion more widely through the provinces. At Thinissut, a non-Roman town in north Africa, the Roman citizens who traded there made a dedication to Augustus god’.63 They probably had in mind the living emperor, who (as we have seen) was not usually the recipient of direct dedications in Rome itself; but, in this alien context, worship of the emperor may have served to mark the boundary between Roman citizens and the non-citizen subjects of Rome. The position of the dedication may itself be significant: for the inscription comes from a site overlooking a Punic sanctuary of Baal and Tanit. This juxtaposition is in one way a striking illustration of the varied religious culture of this small African town – but at the same time it must have served to emphasize the difference between the Roman cult of the emperor and the Punic traditions of Baal and Tanit.

Individual Roman citizens too could adopt similar strategies. At Vaga, another non-Roman town in north Africa where there had long been Italian traders and Roman citizens, one Marcus Titurnius Africanus restored a shrine of Tellus (Earth), dating the record – in conventional Roman form – by the consuls of 2 B.C.; and in the Greek city of Nicaea (in Bithynia) an Italian trader dedicated statues of the Capitoline triad to the local god, albeit with a Greek inscription.64 We also read of celebrations of the festival of Saturnalia by Roman students studying in Athens – or by one retired soldier living in the Egyptian Fayum, who wrote to his son to order ten cocks from the local market for the festival.65 Individuals no doubt reminded themselves (as much as the community at large) of their Roman status by making specifically Roman religious gestures.

This general pattern of Roman religious influence in the empire – with its concentration on those groups and places with some formal Roman status – is cut across by a whole variety of different factors. We conclude this section by exploring two of those complexities: first the spread of different forms of what could count as ‘Roman’ cult among provincial communities; secondly the different impact of Roman deities on the élite and non-élite.

Throughout the Roman world there were wildly different images of ‘Roman’ religion; as we saw in our discussion of coloniae, different communities in the provinces must have constructed their own versions of what they thought was Roman. Of course in earlier chapters of this book we have raised just this question in relation to Rome itself: what was to count as official Roman religion? The negotiability of that category even at the very centre of the Roman world, the changing definitions of ‘Romanness’, is obviously relevant to the ‘export’ of Roman religion to provincial communities – as is clearly illustrated in the cult of Magna Mater.

This cult, as we have seen, was ‘officially’ introduced to Rome in the late third century B.C. From there, it became a common feature of the towns of Italy and the provincial coloniae and municipia in North Africa, Spain, the Danube region and especially Gaul;66 at first the cult members seem to have been limited to ex-slaves and others of low formal status, but from the mid second century A.D.local dignitaries too are found within it. In other words, a cult of eastern origin spread through the Roman world not from its eastern ‘home’, but from Rome and so as a ‘Roman’ cult. By the mid second century A.D., in fact, the cult in Italy and at least the western provinces was under the general authority of the Roman priests, the quindecimviri, who had originally been responsible for the introduction of the cult to Rome. The priests of Magna Mater in Italy and Gaul are sometimes even given the title ‘quindecimviral priests’; and an inscription from the territory of the colonia at Cumae in southern Italy preserves the text of a letter from the college of quindecimviri in Rome, authorizing the local priest of Magna Mater, whom the town had recently elected, to wear the special armlet and crown (the priestly badge of office) within the territory of the colonia.67

There is also a striking reference to a direct link with the city of Rome in an inscription from the colonia of Lugdunum (modern Lyons), recording the performance of a taurobolium (the cult’s characteristic sacrifice of a bull). This text refers to the ‘powers’ (‘vires’ – probably the genitals of the sacrificed animal) being ‘transferred’ from the Vatican sanctuary (‘Vaticanum’). It is not exactly clear what that means. It seems unlikely (though not impossible) that the bull’s genitals should have been taken from the Vatican in Rome to Lugdunum. More likely, perhaps, there was a ‘Vatican sanctuary’ in Lugdunum itself – but, if so, its name (and no doubt other aspects of its cult) derived directly from the Roman model.68 In either case, the direct or indirect dependence of the Lugdunum cult on Rome was unusual. Unlike, for example, the cults of Isis or Mithras, which had no ‘headquarters’ there, the cult of Magna Mater claimed authority from the centre, which had officially adopted the original cult.

Significantly the inscription also states that this taurobolium was performed (as many were at Rome) on behalf of the emperor, as well as the local community – another link with the capital.

The cult of Magna Mater exposes the shifting ambiguities of Roman status, and the expanding definition of what might count as Roman in the provinces: under the general authority of the quindecimviri, she counted both as a ‘foreign’ god (the quindecimviri had, as we have seen, specific responsibilities for cults of Greek origin in the city of Rome) and as a ‘Roman’ god (overseen even in provincial contexts by Roman priests). One of the most striking features of Roman imperialism is that (especially in the west) the spread of Roman religious culture through the empire was marked by the diffusion of cults that in the context of Rome itself claimed a ‘foreign’ origin. It was not only the Capitoline triad, but Magna Mater and Mithras, who could stand for ‘Roman’ religion in the provinces.

Wealth and power are also factors that we have not so far considered in plotting the patterns of Roman religious influence in provincial communities. By and large, in every kind of community the local élite tended to display less interest in local indigenous cults than in the universal deities associated with the Roman empire.69 For example, in the colonia of Timgad, magistrates and priests in the course of the second and third centuries A.D.made a series of dedications in return for their offices to principally Roman deities: Jupiter, Victoria, Mars, Fortuna and so on; one text neatly indicates that the declared purpose of its dedicator was ‘the celebration of public religio and the embellishment of his noble city’.70 In southern France, which had been under Roman control since the late second century B.C., we can detect a significant distinction between (in one aspect at least) the religious practice of the local urban élite and those outside that group. ‘Mars’, the most prominent god of the area, appears in inscribed dedications sometimes with a range of local epithets and sometimes without: the dedications with local epithets are usually associated with dedicators who did not come from old established or distinguished families; Roman functionaries and members of the local élites are much more commonly associated with those without local epithets. In addition, 90% of the dedications to Mars with local epithets are found outside the towns.71 Even in this area, which seems at first sight to be strongly Roman in tone overall (note, for example, the name ‘Mars’), those of higher local status chose to display their relationship with gods who were more obviously part of the Roman system.

Religious display must have been central in the competition for status, both inside and outside the local community. We can only guess how different it might have felt to make a dedication to Mars rather than Mars Alator; we can only guess what costs (as well as benefits) there might have been in publicly displaying allegiance to explicitly Roman gods. But it is clear enough that local élites expressed their own status, as against their social and political inferiors, by parading close ties with the gods of Rome.

2. Controls and integration

The religious impact of Rome on communities without formal Roman status was quite different; it was much less a matter of imitation, much more a question of various forms of control and integration. Roman authorities moved to suppress (or ‘emend’) religious forms that seemed to be a focus of opposition to Roman rule – whenever and wherever they found them. But in other respects there appears to be a clear distinction between their approach to the pre-Roman religions in the west and those in the east. In the Greek east the civic cults seem to have continued, outwardly unaffected by Rome; but in the west local gods were transformed and integrated into the Roman pantheon. This distinction, however, raises the question of how we can identify different degrees of ‘Romanization’; what counts as the transformation of religion under the impact of a conquering power; how far we can assess fundamental changes in religious ideology from its outward forms.

Priesthood was an area of particular concern. In four different areas, we can see how the Romans restricted the power of native priests in the provinces; in all these cases, the priesthoods were organized quite differently from the traditional model of Graeco-Roman city-states (where priests were civic officials, with strict limitations on their authority, drawn in rotation from the local élites) and, to the Romans at least, represented an alternative system of power capable of rivalling their own; often these priesthoods were based on rich and powerful temple institutions.72

Egypt was annexed to the Roman empire in 30 B.C.; here temples, with their powerful priesthoods and widespread landholding, had traditionally been a major focus of religious and political authority. After annexation the Romans were faced with the problem of negotiating their relationship with these powerful religious institutions.73 In detail, the pattern of Roman action in Egypt is very varied: some temple lands were confiscated in 24–22 B.C. (the temples either leased these lands back to be cultivated for revenue or accepted a direct state subsidy); but extensive lands were also granted (or confirmed) to a temple of Isis in the south of Egypt, and some ‘sacred land’ continued to be administered directly by religious officials. Overall, however, even where existing religious institutions were not abolished by the Romans, there is a clear trend towards increasing Roman supervision, if not direct control. All people attached to sanctuaries had to be registered from 4 B.C. onwards; from the mid first century A.D.onwards temple property and dues owed to the state by the temples also had to be recorded. The temples fell within the responsibility both of the office of the so-called ‘Idios Logos’ (the ‘Special Account’, which handled financial and administrative matters) and of the Roman governor, aided by a separate Roman official, known as the High Priest of Alexandria and All Egypt. This High Priest vetted requests to circumcise candidates for the Egyptian priesthood,74 and adjudicated on the qualifications of those already in the priesthood. The Romans probably did not devise all these regulations entirely themselves; they represent in part at least a development of the practices of earlier rulers of the country, the dynasty of Ptolemaic kings (for after all temple power was likely to be a challenge to any secular authority, not just the Romans). However they illustrate a strong assertion of Roman control of Egyptian religious institutions – not just in general, but right down to the level of individual priests, their qualifications and marks of office.

The religious organization of two other parts of the eastern Mediterranean also posed problems for Rome and similar methods of control were introduced. When Judaea passed from the rule of a client king to direct Roman administration in A.D. 6, the Roman governor (as earlier King Herod) appointed or dismissed the High Priest of the temple; as a further attempt to restrict its potential power base, the office was made technically an annual one – even though in practice (as a compromise, perhaps, between Roman authority and Jewish tradition) the holder was regularly re-appointed. The Romans oversaw the finances of the temple and restricted the competence of the Jewish council, the Sanhedrin. But otherwise the day to day temple organization was unaffected by Rome (though new sacrifices on behalf of the empire were now offered there); and Jews in other provinces and in Italy were permitted to continue sending a regular tax and gifts to the temple – until, that is, it was violently destroyed by the Romans following the Jewish revolt of A.D. 66–70. At that point a special, humiliating Roman tax replaced these contributions to the temple: Jews now had to pay not towards the temple at Jerusalem, but in perpetuity for the rebuilding of the temple of Jupiter Capitolinus in Rome (burned down the previous year).75

In Asia Minor too there were temples whose priests wielded considerable secular power. Again Roman responses varied; but all tended towards neutralizing any threat that the priestly organization might represent. When a Roman colonia was established at Pisidian Antioch, for example, the sanctuary of the god Men lost its territories and its sacred slaves, but elsewhere the Romans encouraged a gradual evolution towards priesthood much more on the Graeco-Roman norm. In Cappadocia and Galatia there had been four major temple estates, inhabited by ‘sacred serfs’ (hierodouloi) and ruled by priests. Under Rome, the cults continued to be prestigious, but the communities were transformed into Greek-style city-states and the priesthoods tended to become multiple and to be held (annually) by the local hellenized aristocracy.76

In the west any indigenous priesthoods that predated the conquest by the Romans came under pressure. The Romans attempted actively to suppress the Druids for their ‘magical’ practices and promotion of superstitio, though repression may, in fact, have increased their self-consciousness and cohesion.77 In other cases the message to local élites was clear, even without drastic action by the Roman authorities: local styles of priesthoods were transformed into a Roman pattern. Occasionally, the ancient names were preserved, but the ubiquitous Roman titles of flamen and sacerdos in towns in the Latin west sometimes at least were the result of a reinterpretation of indigenous priestly offices. Civic priesthood on the Graeco-Roman pattern was the norm and as a result, with the exception of the Druids, no indigenous priestly group in the west appears to have posed a threat to the Roman order.

Roman forms of control operated in broadly similar ways, with broadly similar aims everywhere; but in other respects the effects of Roman rule on religious life in the east appear very different from those in the west. In mainland Greece and Asia Minor, where Greek language and culture were dominant and respected by Rome, the religious life of the towns did not, to all appearances, change radically under Roman rule. In Athens, for example, the central cult remained that of Athena Polias on the Acropolis, and the Eleusinian Mysteries continued to have immense prestige.78 Since time immemorial the celebration of the mysteries had involved a grand annual procession between the city of Athens and the sanctuary at Eleusis. In A.D. 220 the people of Athens in fact voted to enhance the grandeur of the procession by increasing the participation of the youth (ephebes) of the city: ‘Since we continue now as in previous periods to perform the mysteries, and since ancestral custom along with the Eumolpidae <sc. the Athenian clan with charge over the mysteries> ordains that care be given that the sacred objects be carried grandly here from Eleusis and back from the city to Eleusis...’79 ‘Ancestral custom’ could be the sanction not for fossilization but for the evolution of cults within a traditional framework. Earlier, probably in the Augustan period, there was a major reorganization of sanctuaries throughout Attica (the region around Athens): new leases of sacred properties were drawn up, to place the finances of the cults again on a proper footing. This ‘restoration’ of ancestral cults even involved moving several earlier temples from outlying sites in Attica in to the agora in the centre of the city – presumably allowing worship to continue in a new ‘heritage’ setting.80 The ancestral cults formed the core of religious life in Athens (and other Greek cities): Isis and Sarapis were important as they had been in the Hellenistic period, but the other elective cults attested in Rome made little impact on Athens.

On the other hand, there was inevitably a good deal of adaptation as a consequence of Roman conquest; at the very least, traditional cults would have taken on new meanings in the context of a Roman province. We shall see in the next section how ancestral Greek religion provided the framework for various forms of worship of the Roman emperor. It is also clear that the Roman calendar had an increasing influence in the east – though it was not here a question of simple provincial imitation of the central model. When the province of Asia decided to honour Augustus by creating a new calendar, the assembly chose to start the year not, as in the orthodox Roman calendar, on 1 January, but on another date of Roman significance, 23 September, which was the emperor’s birthday. (According to the inscription recording this change of calendar, the precise date of 23 September came as a suggestion of the Roman governor – a glimpse of the complex background that must lie behind many decisions of this kind.)81 The Roman authorities also sometimes sought to control the finances of civic sanctuaries. In the very early Augustan period a Roman official in the province of Asia issued an extensive regulation to Ephesus on religious finances, a regulation known from its subsequent revision in A.D. 44: for example, priests (who would no longer have to buy their offices) would not receive subventions from the city, and public slaves were not to dedicate to the goddess their own slaves who would then be reared at the expense of the goddess. Whether this reform was driven by Roman desire to ensure the financial stability of local cults, or by their desire to eradicate religious practices that did not conform to their own model of piety, it is a clear case of Roman intervention in a civic cult of the Greek world.82

In most cases, however, we are not dealing with a straightforward opposition between the continuity of local civic cults and Roman interference. All Roman activity in relation to the cults of the Greek world (from generous subvention to drastic eradication) must have been open to various interpretations. If, for example, a Roman official had paid for the restoration of a Greek temple, would that have counted as Roman respect for traditional civic cults? Or would it have been instead (or at the same time) a mark of Roman take-over, of Rome’s domination of those cults? At the very least, a restoration by Rome must have carried a different significance from a restoration by the local city itself. Even if not outwardly ‘Romanized’, traditional religion was now operating within a context of Roman power and empire. And it was often the local inhabitants themselves who were instrumental in parading the Roman associations of traditional cult. We do not know who placed the statue of the emperor Hadrian that (as Pausanias records) once stood within the Parthenon – but at the very least it must have been authorized by the local Athenian officials. It was, however, certainly they who decided to honour the emperor Nero, emblazoning his name across the architrave of the Parthenon.83 In both these cases we can easily understand how the Roman presence could have seemed to some like an outrageous intrusion of the imperial power into one of the most holy cult places of Greece; or, equally, like the incorporation of Rome within the venerable traditions of Greek religion. ‘Continuity’ or ‘change’ can be matters of interpretation.

In the west, however, where Latin was the dominant language and where there was no unified and prestigious cultural system when the Romans arrived, the religious position of Rome’s subjects was very different from in the Greek east. There was, unsurprisingly, a range of religious continuities as well as resistances to the cults practised in Rome: a calendar in general use in Gaul in the late second century A.D.perpetuated local traditions, and (to judge from names of adherents that are recorded) the ‘Oriental’ cults were of little importance among the indigenous populations.84 However, a crucial aspect of religious change (quite different from anything we saw in the east) was that indigenous gods became widely reinterpreted, by the locals and others, in a Roman form. As we noted at the beginning of this chapter, this process of transformation is difficult to plot – not least, we may now add, because the native deities generally become visible to us only under Roman rule, with increased use of writing on durable surfaces and more iconographic representations in stone. However, the excavation of a sanctuary in the Italian Dolomites, an area conquered by Rome only in the first century B.C., offers a glimpse into the changes in one sanctuary from pre-Roman times onwards.85 Among the finds, which run from the third or second century B.C. through to A.D. 340, are bronze dippers used for drinking the sacred waters from a sulphurous spring. They were inscribed with the name of the god (Trumusiatis or Tribusiatis), initially in the local language (Venetic), then with the same name transcribed into Latin characters and, only in the most recent ones, with the Graeco-Roman name Apollo. It would be a crude oversimplification to suggest that under the sign of Apollo the cult lost all trace of its native roots; after all there is no suggestion of any major change in the rituals through this period. But at the same time it would be little short of a romantic fallacy to argue that nothing had really changed, and exactly the same native god lurked behind his new classical name. The change (or not) of language and names is not merely a cosmetic issue. At the very least, to call a god not Trumusiatis, but Apollo, was to relate the local healing god to the broader classical pantheon.