8 Roman religion and Christian emperors: fourth and fifth centuries

Roman religion changed fundamentally in the fourth century A.D. The city of Rome itself ceased to be the primary residence of the emperor or the main centre of government from the late third century A.D. The military threats posed by ‘barbarians’ on the northern frontiers of the Rhine and Danube impelled emperors to spend more of their time in the north: Trier in Germany, Sirmium in Serbia and Milan in northern Italy all developed as imperial centres. No emperor lived in Rome after the early fourth century A.D.; indeed after the reign of Constantine (306–337) there were only two imperial visits to the city in the course of the fourth century. A major factor in Rome’s changing role was the division of the empire in A.D. 286 into two halves – east and west. Each half was the primary responsibility of one ‘Augustus’ aided (from A.D. 293) by a junior ‘Caesar’. The east also had its own imperial centres (Nicomedia in north-west Asia Minor and Syrian Antioch; then Constantinople founded by Constantine in A.D. 330). This division of responsibility – which was partly a tactical, military response to external threats to the security of the empire, but also became the basis for a whole new politics of imperial rule – persisted to the end of our period, in the early fifth century, and beyond; even though from time to time one ‘Augustus’ (like Constantine) proved able to control the whole empire and resembled once more an emperor of the old type. In the eyes of some Rome was still the grand old imperial capital and life went on much as usual; for others, no doubt, it looked more like a ‘heritage city’, a tourist ghost-town. But even if the image of Rome, as cultural capital, would remain indelibly imprinted on the empire, it was increasingly displaced from the centre of the political and military stage, occupying a marginal position even in the western half of the empire. The history of Roman religion in the fourth century can be seen in part as a response to this displacement of Rome.

The upholders of traditional Roman religion at this period were also faced with a new threat. Christians ceased to be systematically harried by the imperial authorities and became instead the recipients of imperial favour. This did not mean, however, a reversal of some simple dichotomy between pagans and Christians, the latter now victorious over their persecutors. Christians themselves (as we have already seen in earlier chapters) were far from uniform and much imperial attention was devoted to distinguishing ‘true’ from ‘false’ Christians. Nor did Christians make a simple, blanket rejection of all ‘paganism’; there were serious debates as to what was to count as ‘Christian’, how far the traditional customs and festivals of Rome were to be regarded as specifically ‘pagan’, or how far they should be seen as the ancient cultural inheritance of the city and its empire. To what extent, in other words, could Rome reject its ‘religion of place’ without jeopardizing its own cultural identity?

The major change in the fourth century is not so much the defeat of paganism as its change of status. In the face of an imperially backed Christianity, support for the traditional cults of Rome was no longer taken for granted as part of the definition of ‘being Roman’; they became a matter of choice, an elective religion. This situation arose from the actions that Constantine took in favour of Christianity (which we discuss in section 1), as well as from the measures that he and subsequent emperors introduced against practices defined (or re-defined) as unacceptable: heresy, illicit divination and (finally) the official cults of Rome themselves (see below section 2). We trace in Section 3 the growth of the Christian community at Rome (partly, no doubt, a consequence of imperial support), the series of major churches founded at this period as well as the development for the first time of a specifically Christian iconography in visual representation. Finally (in section 4) we explore the continuance of traditional cults at Rome alongside, or in opposition to, Christianity. By the 380s A.D., certainly, some members of the senatorial class were ostentatiously (and piously) maintaining what they defined and championed as the ‘traditional’ cults of Rome in the face of Christianity. The vitality of this group did not survive the sack of Rome by the Goths in A.D. 410, but our period ends with the death of the western emperor Honorius (A.D. 393–423) and the installation by the eastern emperor of a new emperor in the west in A.D. 425 – a vivid symbol of Rome’s now subordinate position in an empire that still clung to its heritage of (lost) cultural omnipotence.1

1. Constantine and the church

By the late third century Christians were well established in Rome, and elsewhere in the empire – even though they probably formed only a small minority of the population, and their growth may have been held back by periods of persecution.2 The persecution initiated by Diocletian in A.D. 303 was still a recent memory3 when in A.D. 312 Constantine marched on Rome and defeated his rival Maxentius outside the city at the Battle of Milvian Bridge. This battle (which might otherwise have been remembered as just one chapter in the repeated and inglorious story of Roman civil war) is said to have marked a crucial turning point in the history of Christianity – and so in the history of the western world. A Christian, writing at most four years later, claimed that as the result of a dream Constantine had inscribed ‘the heavenly sign of God’ on his soldiers’ shields just before the decisive conflict.4 That is, on the eve of the Battle of Milvian Bridge, Constantine was believed to have abandoned the traditional deities of Rome in favour of the Christian god.

The conversion of Constantine was among the most unexpected events in Roman history, and remains highly controversial. Even supposing that what happened at and before the battle was central to Constantine’s support of Christianity (which is, of course, far from certain), almost every aspect of that support has been debated ever since. Was he sincere in his adherence to Christianity? How far did he conflate Christianity with elements of traditional cults? From what date is Constantine’s firm support of Christianity to be dated – from A.D. 312 or later? (He was not formally baptized until his deathbed, but this was not uncommon in early Christianity).5 The questions are unanswerable. Nonetheless Constantine’s own version of what he said and did at that time tells us exactly how to see the matter. We are told that many years later he declared on oath to a Christian bishop, Eusebius, that before the battle he had seen by day a vision in the skies of the cross inscribed with the words ‘By this, conquer’, and that the following night Christ had appeared to him in a dream bearing the same sign. Constantine himself (according to Eusebius) recalled the victory as a Christian victory, and is said to have put up in Rome a statue of himself holding the cross.6 Others may have declined to accept this Christian interpretation;7 but, for his part, Constantine certainly soon proceeded to act in favour of the Christian church.

Within a month or two of the battle Constantine joined with the eastern emperor Licinius in calling for the toleration of Christian meetings and the rebuilding of churches.8 In the first months of A.D. 313, in what were to be the first of a series of moves by which imperial favour and imperial resources were put behind Christianity, he restored church property in Africa (and doubtless other provinces), made huge donations to the church from the imperial treasury and granted exemption to the clergy from compulsory civic public duties.9

Fig. 8.1 Two medallions illustrate Constantine’s public position. (a) Constantine with Sol (Sun) as a guardian god behind him. Other traditional gods were dropped from the coinage under Constantine; Sol, (which, arguably, had a Christian interpretation), continued until the 320s A.D. (b) Constantine on a silver medallion struck for presentation in A.D. 315. On his helmet is the chi-rho monogram, often used as an abbreviation of ‘Christ’. Such Christian emblems remained fairly unobtrusive on coinage until the fifth century A.D.

These actions were without precedent. Though previous emperors had ended persecution of Christians by restoring property, no previous emperor had given the church money, let alone money on this scale. (The annual rents on the land he gave to the church came to over 400 pounds of gold per year – a substantial sum, though only 10% of the income of the wealthiest senator.) The exemption from the burdens of civic office represents a yet more striking innovation. Such exemption was a privilege that had previously been granted only to groups such as athletes, doctors and teachers that were seen as particularly meritorious within traditional Roman culture. The only priests to have held the privilege were those of Egypt (following a particular local tradition); otherwise ordinary civic priesthoods were compatible with membership of local councils, and entailed only limited immunities. Constantine’s extension of exemptions to (orthodox) Christian clergy marked a new recognition that the Christian church was of benefit to the state; or rather perhaps annexed the church as a benefit to the state. When the emperor Galerius had ended persecution of the Christians in A.D. 311, he had expressed the hope that the Christians would pray to their god ‘for our welfare, and that of the state and their own’. Constantine accepted this logic in stating the reason for the grant: so that the clergy

shall not be drawn away by any deviation or sacrilege from the worship that is due to the divinity, but shall devote themselves without interference to their own law. For it seems that, rendering the greatest possible service to the deity, they most benefit the state.

No longer was the safety and success of Rome entrusted to the traditional state religions alone.10

In addition to grants of money to the Christian authorities, Constantine was also personally responsible for the foundation of new church buildings. In Rome he paid for five or six churches, which fundamentally changed the profile of the Christian community.11 Probably only a year or two after the Battle of Milvian Bridge work began on a great ‘basilica’ with an adjacent baptistery. Known as the Basilica Constantiniana (now St. John Lateran), this became the principal church of the city. Other buildings were erected in memory of the martyrs of Rome. And a decade later (probably in the mid 320s) the basilica of St. Peter’s was started. The significance attached to the earlier monument to St. Peter determined the location and level of the church.12 The surrounding, largely pagan, cemetery was levelled off to provide a foundation at the appropriate height, and the trophy was enshrined in the apse, projecting about three metres above the floor of the basilica. The Christian community in Rome had now for the first time a monumental setting.

The designs of these Constantinian basilicas varied, but all were derived from a type of secular public building that had long been a feature of Rome and other Roman towns – the traditional basilicas that lined, for example, the Roman forum, with a large central space (or nave) and aisles running down each side. Following this pattern the Basilica Constantiniana was a huge hall, some 100 metres in length, with two side aisles giving a total width of about 54 metres. St. Peter’s was on the same scale, but its design differed somewhat. Here the central nave was again flanked by two aisles, but between the nave and the apse was a crossing, wider than the aisles, which focussed the building on the trophy of St. Peter in the apse. The overall dimensions are impressive: the nave was 90 metres long, the total length 119 metres and the width 64 metres. In front of the church was a large open area, equal in size to the body of the church, surrounded by arcades. The dimensions are comparable with the grand imperial buildings of the past: the Forum of Augustus was 125 by 118 metres, and the (secular) Basilica in Trajan’s Forum, the largest basilica ever built in Rome, 170 metres (or 120 metres within the apses). The differences between the design of St. Peter’s and that of the Basilica Constantiniana relate closely to their different functions. The latter with its contemporary baptistery was the principal church of the city, designed for regular use on festal days, while St. Peter’s was a martyr’s shrine, used for burials and commemorative feasts. But the crucial point is that both these buildings, in taking the overall design of the secular basilica, strikingly reject the form of traditional religious, temple architecture of the Roman world – whose function had been principally to house the deity. Logically enough (for, unlike pagans, Christians congregated in the house of their god), the new, monumental Christian architecture was derived from the vast halls that the traditional pagan culture of Rome associated with law-courts and market-places and other places of public assembly. Despite their size, Constantinian church buildings in Rome remained, literally, peripheral to the city. There is no church building under Constantine in the ancient heart of Rome, with its prestigious temples and shrines. Only the Basilica Constantiniana and a chapel inside an imperial palace were – just – inside the walls of Rome (but outside the pomerium), and they both lay on property owned by the emperor. The other Constantinian basilicas were, like St. Peter’s, martyrs’ shrines and covered cemeteries; they all lay outside Rome in the areas of Christian burial and at least some were again on imperial estates.13 Constantine sought not to rewrite the religious space of Rome, but to provide Christians with their own, supplementary space alongside.

2. Imperial religious policy

Constantine started a pattern of imperial intervention in favour of Christianity that finally helped Christianity to triumph over paganism. But the process was much more complicated than that apparently simple outcome might suggest. Emperors did not regard all Christians with favour, nor did they at first seek to eliminate all elements of the traditional cults.

From the outset, Constantine’s support for Christians was selective. Already in A.D. 313 his interventions in Africa were directed not simply to ‘Christians’, but to ‘the Catholic Church of the Christians’. As he had been informed, there was a division in the African church. One group recognized Caecilian as bishop of Carthage, while the other denied his authority (on the grounds that he had been consecrated by a bishop who had himself handed the Scriptures over to the Roman authorities in the Diocletianic persecutions) and elected a rival bishop. Constantine had decided that Caecilian’s church was to be the recipient of his benefactions, but the other party petitioned the emperor to put the matter to ecclesiastical arbitration. After two such arbitrations had gone against them, the opposition, now headed by Donatus, appealed to Constantine himself. The emperor had investigations made in Africa, in A.D. 315 gave judgement in favour of Caecilian, and perhaps in A.D. 317 ordered the confiscation to the state of Donatist churches. Constantine was not an indifferent and passive authority. As he wrote in A.D. 314 to one of his officials involved in the Donatist case, ‘I consider it absolutely contrary to the divine law (fas) that we should overlook such quarrels and contentions, whereby the Highest Divinity may perhaps be roused not only against the human race but also against myself, to whose care he has by his celestial will committed the government of all earthly things.’14 Although it is hard ever to see such disputes from anything but the winning, ‘orthodox’ side, it is clear that imperial authority would not tolerate such dissension within the church; in fact, the authority of the emperor over the Christian communities was defined and displayed precisely in his insistence in adjudicating between rival groups, in eradicating dissension. By the same token, the emperor could not stay clear of manipulation by the politicized churches, but was drawn constantly into the arena of socio-religious politics. This was the new currency.

A decade later, after Constantine had defeated the eastern emperor and united the empire in his own hands (A.D. 324), he discovered that the eastern churches were divided even more deeply than the African church was. Whereas the Donatists had disputed the validity of the ordination of a bishop, the new issue was ostensibly doctrinal. A man called Arius argued on philosophical grounds that as God was eternal, unknowable and indivisible, his Son could not properly be called God; though created before all ages, the Son was created after the Father and out of nothing.15 Doctrinal disputes within the church were not new, but previously it was the church authorities themselves that had sought to define and exclude ‘heretics’.16 But with Arianism Constantine himself took action. In A.D. 325 he moved a forthcoming council of bishops from Ancyra (modern Ankara) to Nicaea (modern Iznik in north-west Turkey), an attractive city more accessible for western bishops, and more convenient for Constantine himself. He personally attended at least the major sessions – and for the first time an emperor, with all the backing of his wealth, influence and temporal power, personally sought to establish Christian orthodoxy. Under his direction the council reached general agreement on the form of words to be used in the statement of Christian beliefs known as the ‘creed’ (this particular form of words, which still underlies the phraseology used in some modern Christian churches, is given the title the ‘Nicene Creed’, after the city of Nicaea). Meanwhile, Constantine exiled those who dissented – Arius, two of his supporters and their followers. Not only had Constantine sought doctrinal unity; he now, again for the first time, imposed the penalties of the criminal law on ‘heretics’. The fusion of religious rule and imperial authority could not be more dramatically displayed.

Despite imperial interest and actions in favour of ‘orthodoxy’, Donatists and Arians continued to be influential, and there were numerous other ‘heretical sects’ in the fourth century. From Constantine onwards emperors spasmodically penalized such sects, their religious meetings were banned or any place where they met was confiscated.17 In addition, other measures were sometimes taken that had the effect, or indeed the aim, of marking out these alternative Christian communities as heretical – at the same time as punishing their heresy: rights to bequeath or receive property by inheritance might be restricted; they might be refused exemptions from the burdens of civic office, or banned from the imperial service. But inevitably the definition of ‘orthodoxy’ varied. Two of Constantine’s successors in the east supported Arianism and so acted against the supporters of the Nicene creed. But the principle remained that the sanctions of imperial authority were available to decree and determine orthodoxy; orthodoxy followed imperial power; political resistance could be heresy.

Constantine and later emperors also took action against a range of non-Christian cult practices. In the later fourth century emperors legislated against Judaism: Christian converts to Judaism lost their property, while Jews were banned from an increasing range of public offices, both local and imperial. Though traditional cults as a whole came to be classed as superstitio, for much of the fourth century the term remained ambiguous and was a useful tool in the hands of different groups. As Christians had argued since at least the third century A.D., Christianity was the religio. But, if so, what was superstitio? Until the early fifth century Judaism was termed either a religio or a superstitio, depending on whether the legislator was favourable or hostile.18 The ambiguities are neatly encapsulated in a regulation of A.D. 323. Constantine was concerned by reports that the Christian clergy of Rome had been compelled by people ‘of different religiones’ to perform sacrifices; he laid down that they must not be forced to attend rites ‘of another’s superstitio’.19 And in A.D. 337 Constantine warned a town in Italy that a temple there to his family ‘should not be polluted by the deceits of any contagious superstitio’.20 Within a Christian frame of reference this would imply that there were to be no pagan sacrifices at the temple, but Constantine was writing to non-Christians, who might interpret him as ruling out (for example) only illicit divinatory types of sacrifice. Constantine may in fact have deliberately played upon the ambiguities of the term, which might usefully evade any very precise definition.

There is certainly no clear evidence for a simple campaign by Constantine and his successors against ‘paganism’. Imperial ordinances were directed only at particular aspects of the traditional cults, and might always be seen as part of a long-standing tradition of imperial action against superstitio. Thus Constantine threatened severe punishment on those who used ‘the magic arts’ against someone’s life or to arouse sexual desire; however, he exempted magic for medicinal or agricultural purposes. These categories are familiar from the earlier empire.21 Similarly, Constantine forbade diviners to practise in private houses; ‘those who wish to engage in their superstitio should practice their own ritual in public’. Again, Roman law had long banned some types of consultations of diviners. From A.D. 357 all divination (with the exception of that performed by state haruspices) was assimilated to indubitably noxious magic and banned.22 The new conflation of divination and magic helped to generate a spate of trials and an atmosphere of fear and suspicion. Accusations of magical practices were levelled in the highest circles; those who had achieved untoward prominence were wide open to accusations of having employed occult arts.23 Pagans were doubly vulnerable. Christians, who ‘knew’ that they worshipped demons, could easily and incontrovertibly suggest that they manipulated them to gain vain knowledge and for illicit purposes.

Other elements of paganism, however, which were superstitio only in the Christian sense remained untouched by Constantine and for the next few decades. Constantine certainly by A.D. 315 (and perhaps from A.D. 312) declined himself to take part in official sacrifices on the Capitol at Rome (or elsewhere),24 but he remained pontifex maximus, appointing another member of the pontifical college to perform his duties, as emperors had always done when absent from Rome. Though the Saecular Games were not performed, as calculations suggested they should have been, in A.D. 314, the official cults of Rome (and other cities) seem to have continued without restrictions. Thus the Roman priesthoods continued to perform their traditional functions. If lightning struck the palace or other public buildings in Rome, Constantine permitted the haruspices to investigate the meaning of the portent; the pontifices retained supervision of tombs; and when the (Christian) emperor Constantius II (A.D. 324–361) visited Rome in A.D. 356, as pontifex maximus he appointed new priests from the senatorial order.25

Traditional temples in the city also received imperial protection. Despite Constantius’ proclaimed desire to root out all superstitio, he decreed that temples at Rome should not be violated – on the grounds, so it is reported, that traditional popular amusements originated there. And he was remembered (by the pagan Symmachus) as taking an intelligent interest in the temples during his visit to Rome: ‘He read the names of the gods inscribed on the pediments, enquired about the origin of the temples, expressed admiration for their founders and preserved these rites for the empire, even though he followed different rites himself.’26 Though a Christian official might in the 370s close a sanctuary of Mithras, pagan officials are found restoring temples at Rome during the fourth century, and until the sixth century emperors ordered that Roman temples be preserved. Only then was a temple in Rome (the so-called Temple of Romulus) converted to Christian usage, and for this imperial permission was needed. Elsewhere, by contrast, from the mid fourth century on emperors ordered that temples should be closed (perhaps from fear of their use for illicit divination), thus giving implicit sanction to zealous Christian bishops who sought actively to destroy them.27 In Rome itself, temples seem to have been detached from the taint of superstitio, partly (as the story of Constantius’ curiosity indicates) because of their prominence in the city’s history and heritage.

Not all emperors were Christian. The fourth-century sequence of Christian emperors was interrupted, albeit briefly, by Julian (sole emperor A.D. 361–3), who attempted to revive traditional cults throughout the empire; he planned a network of high priests who would take responsibility for promoting cults in their areas. This policy was presumably welcomed in various parts of the empire, and amongst those still loyal to traditional cults. In Rome the sanctuary of the Syrian gods on the Janiculum, which had previously been destroyed, was revived in the fourth century, perhaps during the reign of Julian. But, in general, Julian showed little interest in traditional cults at Rome,28 and died before his ideas could have much effect anywhere. The following, Christian, emperors continued the earlier trend of action against superstitio.

Until the 370s these Christian emperors were prepared to accept an arm’s length relationship with the official cults of Rome, but in (apparently) A.D. 379 the emperor Gratian resigned the position of pontifex maximus and in A.D. 382 decided to remove the financial support of the cults of Rome. Such immunities from public service that the Vestals and the Roman priesthoods enjoyed were abolished; the revenues of their lands were confiscated and used (as an extra affront) to pay the wages of porters and baggage-carriers; the altar of the goddess Victory (Victoria) in the senate house, on which senators, since the time of Augustus, had sacrificed before each meeting, was removed (the altar had already been removed once by Constantius II, but on that occasion had soon been replaced). The senate protested to the emperor Gratian, when he refused the office of pontifex maximus, but no emperor was again to be (even nominally) head of Roman religion.29

The practice of sacrifice also fell under an imperial ban. Since Constantine, sacrifice had been in disfavour in imperial circles – but he and his successors took action directly only against magic and private divination. So, for example, nocturnal sacrifices, long characteristic of magic, were prohibited; but Vettius Agorius Praetextatus, a well known traditionalist and governor of Achaia at this time, immediately persuaded the emperor not to enforce this ban in Greece – thus permitting the Eleusinian mysteries to continue; and in Rome and other major cities of the empire official sacrifices were for a time left untouched.30 However, in A.D. 391 the emperor Theodosius prohibited all sacrifices, closed all temples, and threatened Roman magistrates with special penalties if they broke the ban. The following year the prohibitions were repeated and made more specific. Sacrifice for the purpose of illicit divination was to be severely punished, even if it had not involved an enquiry about the welfare of the emperor. The forbidden curiosity that we saw alleged against Apuleius in chapter 5 became part of the rationale for a general prohibition on pagan sacrifice.31

The effect of Theodosius’ prohibitions in Rome was, however, limited. The ban of 391 was promulgated throughout the empire, but by 392 Theodosius was no longer in control of the west, and the western emperor Eugenius attempted to conciliate the pagan aristocracy by restoring the endowments that had been removed by Gratian – not to the priests directly, but to leading pagan senators, who would put them to their proper use. As we shall see, some traditional cults of Rome continued into the fifth century, but repeated imperial enactments continued to clamp down on the practices of paganism.32 We cannot tell how far the repetition of these bans on traditional religion was a consequence of widespread disobedience; how far the series of different laws addressed subtly different aspects of traditional cult; or how far the point of the legislation was the public declaration of the emperor’s support for Christianity. But the overall message is clear enough: true (that is, now, Christian) religion was to be promoted and those addicted to superstitio punished.

3. The growth of the Christian church

The general pressure of imperial authority in favour of catholic, i.e. orthodox, Christianity affected the range of choices open to people in Rome. In the second and third centuries A.D. there had been first the state cults and then a great variety of religious groups (followers of Isis, Mithras, Jahveh or Christ). From Constantine onwards the choice was simplified – or reversed. Partly because of imperial patronage, Christianity increasingly became the base-line, while it was the traditional cults that now became the option, the matter of choice. Even members of the senatorial order, whose religious, political and social identity had long been bound up with traditional cults, now found that the upholding of those cults was something they could choose or reject. At one level these choices were exclusive: it would have been hard, for example, to make a public claim to be a Christian and at the same time to perform animal sacrifices to the Capitoline triad. But, even so, it was not a total polarity. Some Christians, as we shall see, also attempted to incorporate elements of their traditional Roman heritage.33

The growth in the number of Christians in Rome (and elsewhere in the empire) continued in the fourth century. Some of these were more visible than others: particularly women of the senatorial order, prominent in the later fourth century for their parade of virginity, self-starvation and other ascetic practices. But overall the number of individual Christians is impossible to estimate; we know for certain only that the number of priests in Rome had risen by the end of the fourth century to around 70, and that by the early fifth century Rome had 25 principal centres of worship (and maybe 15 others). Along with this specifically Roman growth, the movement within the church from the Greek language to Latin continued; in the course of the fourth century the liturgy was turned into Latin.34 The Christian church was now divided, like the empire itself, into east and west.

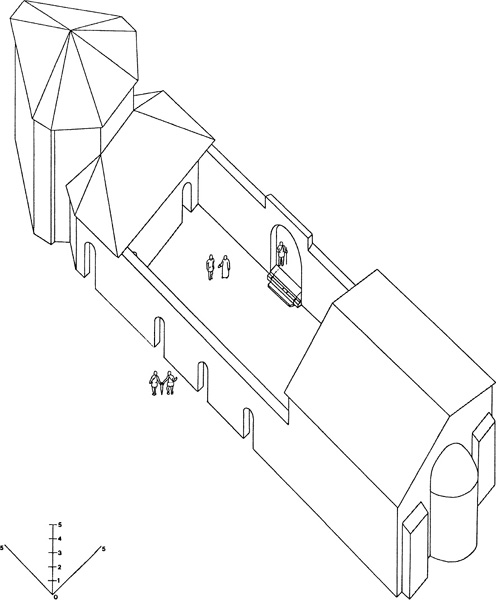

Church building continued on the lines established by Constantine.35 The churches were built in all the residential districts of Rome, so that finally (in the fifth century A.D.) there were almost no houses more than 500–600 metres from a church that was regularly open for worship. In the fourth century there were still no churches in the monumental centre of the city, though one was built at the foot of the Palatine near the Circus Maximus. This may be connected to patronage and land-ownership. After Constantine only one more church in our period was an imperial foundation, but to build in the monumental centre (which was mainly ‘public land’) imperial permission was needed. The rate of the building in the fourth century is not dramatic, but ecclesiastical and private patronage was responsible for five new churches, in addition to other religious buildings. Thanks in part to Constantine, the church itself (as an institution, rather than a building) was now wealthy, and was also successful in tapping the resources of the Roman élite into its monumental building schemes. This was not a simple shift of private patronage from pagan temples to Christian churches, but a striking contrast with the pagan traditions established under Augustus: for since the beginning of the empire, public building in Rome – both religious and secular – had been the monopoly of the emperor himself, from which the rest of the élite were effectively excluded. After three centuries of imperial monopoly, in other words, Christianity found a role once more for the non-imperial, élite patron of monumental religious building in the capital.

The development of St. Peter’s is symptomatic of ecclesiastical building in this period, showing the involvement and patronage of the Roman élite, the church hierarchy and the emperor himself: Damasus, the bishop of Rome, drained the marshy area round Constantine’s church and added a baptistery (A.D. 366–84); between A.D. 390 and 410 a rich Roman lady built a mausoleum for her husband off the apse of the church; while around A.D. 400 the emperor Honorius built a mausoleum for himself and his family, opening off the south crossing of the church. In addition, the approach to the church was monumentalized (using forms of architecture that had once adorned the secular centres of cities). A monumental portico was built (perhaps in the late fourth century), running due east from the church and linking up with one of the bridges over the Tiber. These lavish schemes helped to make St. Peter’s a major focus not just for Rome, but also for Christians from elsewhere. The Christian pilgrims of the early fourth century seem to have ignored Rome in favour of the Holy Land, but by the end of the fourth century they were certainly drawn to Rome.36

The martyrs Peter and Paul were of central importance to the Roman church. Bowls, medallions and statuettes commemorated them jointly; they shared a feast day; and under Damasus were seen as citizens of Rome. United in harmony (unlike Romulus and Remus – whose original foundation of Rome was marked by the murder of Remus by Romulus), they were now the true founding heroes of the city.37 Depiction of this harmony formed part of the claim of the Roman church to high status. Peter was believed to have come to Rome with Paul, and from him the bishops of Rome followed in (allegedly) unbroken sequence. But there was as yet no overall claim by the church in Rome to primacy over all the Christian communities in the world. The Roman church had, as in the third century, considerable authority in Italy, Gaul, and Spain (for a time) – but even in Italy this was probably dependent on the vigour of particular bishops; with Africa, on the other hand, the Christian church at Rome had only loose connections, and in the East it had no special standing at all.38

The adherence of people in Rome to the Christian church raised problems of identity and status. The celebration of the ancient festivals of Rome seems to have remained popular throughout the fourth century A.D. And the games associated with them (the ostensible reason, as we have seen, for Constantius’ preservation of Roman temples) continued to draw great crowds. Maybe all these crowds were entirely pagan; but there is little reason to think so – after all, the Christian writer Ausonius could write an affectionate poem on the Roman festivals.39 The Christian audience presumably thought of their own attendance at such occasions in a variety of different ways – some little troubled by the contradictions that must have been glaring to others, some (we may guess) seeing no connection between these popular amusements and their own personal religion, some (as at every period) being much stricter and more exclusive Christians than others. For many senators, though, the matter must have been particularly pressing. Christian senators, in general, were as determined as their pagan colleagues to maintain the prestige of Rome and the senate in a changed world. And yet the traditional identity of Rome (for the élite at least) was derived from its traditional cults.

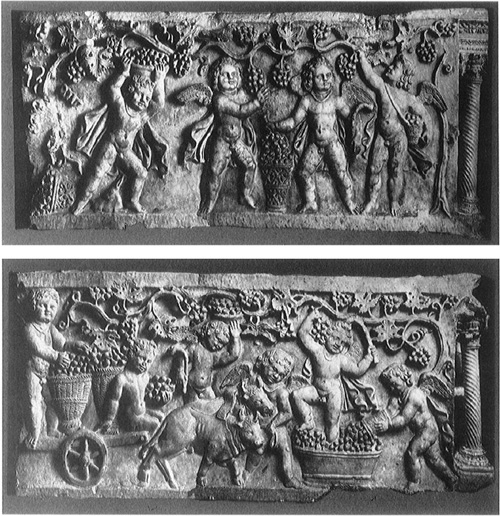

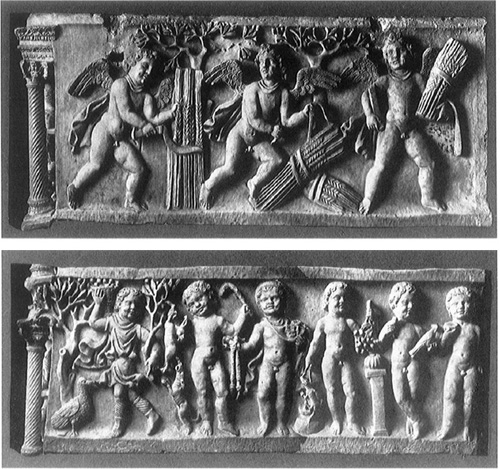

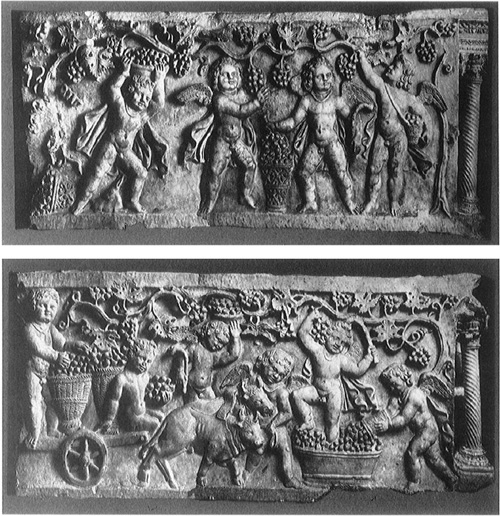

By the mid third century some senators had become Christians, but seem to have kept their Christianity a private matter.40 Later senators were not so circumspect. Junius Bassus, prefect of the city of Rome, died a Christian in A.D. 359. His sarcophagus, which was placed in the crypt of St. Peter’s next to the martyr’s memorial, uses a classical style, but an iconography derived principally from the Old and New Testaments (Fig. 8.2). This is more revolutionary than it might seem at first sight. In the period before Constantine there was (to our knowledge) no specifically Christian iconography – at least there is no trace of the repertoire of Christian images (the Good Shepherd, Christ Ascending, Christ on the Cross) that were later to become standard. This sarcophagus symbolizes the emergence of Christianity and Christian images onto the public stage. But, even here, at either end of the sarcophagus were representations of winged putti engaged in harvesting grain and grapes, scenes common on non-Christian sarcophagi of the period.41 A similar pattern is seen in the mausoleum of Constantine’s daughter Constantina (a building known now as the church of Santa Costanza), which was built between A.D. 337 and 361. In the cupola were mosaics (now destroyed, but known from earlier drawings) depicting biblical scenes above a marine landscape with putti; while the (surviving) ceiling of the ambulatory around the central cupola, shows grape-harvesting and (among other motifs) medallions with putti and female figures.42 The newly created Christian imagery did not mark a complete break with traditional, pagan iconography. Though it generated some distinctively Christian images, it also incorporated, and no doubt at the same time re-interpreted, themes from the pagan past.43

Upper class Christians also negotiated a delicate relationship to specifically pagan festivals. In A.D. 354 a lavish volume, the work of one of the leading scribes of the day, was presented to a rich Christian in Rome.44 The book consists primarily of a calendar which lists all the festivals celebrated in Rome, both those in honour of the emperor and those for the traditional gods. The entry for each month is also accompanied by an illustration, which in some cases seems explicitly pagan. For January there is a man offering incense, probably a ward magistrate sacrificing to the Lares Augusti; April has a man dancing, probably at the festival of Magna Mater; a priest of Isis is featured in November; and December depicts the celebration of the Saturnalia. These representations of pagan religious festivals were presumably welcomed by the recipient of the book, but the title page has a strongly Christian dedication, and five of the 12 supplementary texts are also Christian: a list of the dates in which Easter had fallen between A.D. 312 and 358, and a continuation for the future 50 years; the dates of burial of bishops of Rome; a calendar of the martyrs of Rome; the list of bishops of Rome; and a Christian chronicle down to A.D. 334 (though this may not have been part of the original book). Even the lists of Roman consuls in the book record four Christian events (the birth and death of Christ; the arrival in Rome and martyrdom there of Peter and Paul). The juxtaposition of the two traditions is striking – and it raises again the question of the varieties of Christian adherence, and what is to count as ‘Christian faith’. One explanation of the text is that there was a category of people (the recipient of this book being one) whose Christianity was purely nominal, and whose hearts were still in the old world. But this seems unlikely at this period: for most of the fourth century, and certainly under Constantius II when the book was created, there was little political advantage in being a Christian; despite curbs on pagan practices, emperors appointed both pagans and orthodox Christians to positions of high responsibility. ‘Nominal Christianity’ would hardly have been an advantage; indeed, the pressures of the local context on the Roman élite strongly favoured the traditional practices. We are more likely dealing with a group of people who became Christians without seeing the need (or, maybe, being willing) to give up elements of traditional Roman practice; without being prepared to jettison what made Rome Roman. Maybe, after all, both festivals of Isis and of Peter and Paul could enhance the dignity of Rome.45

Fig. 8.2 The sarcophagus of Junius Bassus. Upper level of the front: Abraham and Isaac; Peter’s arrest; Christ enthroned; Christ’s arrest; Pilate’s judgement. Lower level: Job’s distress; Adam and Eve; Christ’s triumphal entry; Daniel; Paul’s arrest. On the lid: a mask of Sol; a relief (lost); averse inscription about Bassus’ public funeral; a funerary banquet – common on earlier non-Christian monuments; a mask of Luna. The two ends show putti harvesting grapes (this page) and grain (next page, top) and with flowers and birds (next page, bottom). (Height of sarcophagus, 1.41m.; width, 2.43m.; depth, 1.44m.)

4. The traditional gods

Rome in the fourth century A.D. remained for some people a city characterized by the worship of the ancient gods. Others could find there great diversity. Scattered through the city were Christian meeting places, which were gradually receiving distinctive, monumental form, and on the periphery of the city were the prominent Christian foundations of Constantine. The Jewish community continued to flourish; Jewish catacombs were in use through the fourth into the fifth century A.D. and the synagogues may have become more lavish.46 However, the upholders of the old order might choose to ignore these monuments. As we have seen, the pagan historian Ammianus Marcellinus, when describing the visit of the emperor Constantius II to Rome in A.D. 357, depicted the (Christian) emperor admiring the temples and other ancient ornaments of the city.47 This account tendentiously suppresses any mention of Christianity or Judaism in Rome. In a similarly tendentious way, two fourth-century catalogues which list many of the buildings of the city area by area note traditional temples, from the Capitolium to the Pantheon; they give a total of 80 ‘gold gods’ and 84 ‘ivory gods’ (the gold and ivory were the material of the cult statues). But they too systematically exclude mention of any Jewish or Christian buildings. What observers saw of the religious buildings of Rome very largely depended on what they chose or refused to see.48

The traditional monuments of the city were duly restored in the course of the fourth century A.D. by the Prefect of the City, who had taken over the functions of the Curator of the Sacred Buildings of the early empire. In the mid century one Prefect repaired a temple of Apollo, and another had pulled down private houses that abutted temples and restored the images of the Consenting Gods (Di Consentes) in the Forum, while a little later the emperor ordered another official to restore a temple to Isis at Portus (near Ostia, the port of Rome). The cult of Vesta also retained four days for her rituals in the official calendar and was specifically mentioned in a contemporary description of Rome, though the major series of third-century statues of Vestals, sometimes sponsored by grateful clients of the priestesses, has only two extant successors in the fourth century. Even after the reforms of Gratian, when the responsibility of the Prefect of the City was redirected toward the Christian buildings, instead of the traditional temples, the monuments of pagan religion were not entirely neglected by the imperial authorities. Under the emperor Eugenius (A.D. 392–4) some temples were again restored and as late as the 470s a Prefect of the City is known to have restored an image of Minerva.49

The traditional religious practices of Rome were not mere fossilized survivals. They did not incorporate elements of Christianity or Judaism (in this sense they were quite different from Christianity, with its frequent assimilation of pagan symbolism); but there were continuing changes and restructuring through the fourth century. Our best evidence comes, again, from the Calendar of 354.50 Here we can see that games in honour of the emperor continued to be remodelled and adjusted to the new rulers. There were games to mark the birthdays of Septimius Severus and Marcus Aurelius (as there had been in the army calendar found at Dura Europus). But only 29 such occasions in the course of the year were in honour of previous dynasties; the remaining 69 were for birthdays and victories of the house of Constantine. The cycle of festivals in honour of the gods was also reworked – as is clear if we look at the evidence of just one month, April. Ancient festivals were still marked, and we may presume celebrated, over many days: April includes festivals to Venus, Magna Mater, Ceres and Flora, as well as the Birthday of the City, as the Parilia was by now known. But about half of the festivals of the Republic do not feature in this calendar, including in April the Fordicidia, Vinalia and Robigalia. However, other festivals have been added: the celebration of the birthdays of the god Quirinus, and of Castor and Pollux, and a festival in honour of Sarapis. The date at which these festivals entered the official calendar is unknown. Quirinus and Castor and Pollux had had temples in Rome since the republican period, but had no celebrations on these dates in the early empire; Sarapis had a (modest) sanctuary built by Caracalla, under whom the festival may have originated, but there was already a popular festival in the first century A.D.51 This fourth-century calendar thus honoured a range of deities of diverse origins.

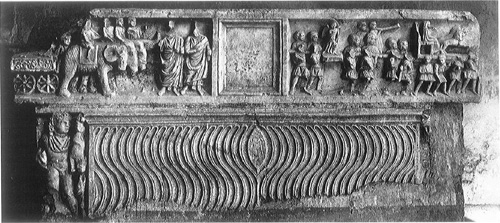

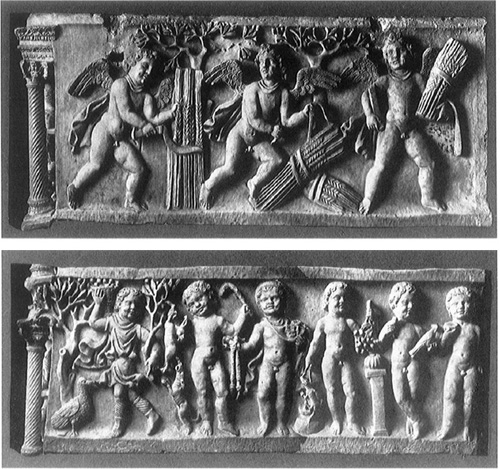

Fig 8.3 A sarcophagus from Rome, c. A.D. 350. On the left, four elephants pulling a wagon (on which was presumably a divine or imperial image), preceded by two men in togas. On the right, an image of Magna Mater, with her two lions, is carried on a ferculum; behind her an image of Victory. Between them a trumpet is played. The scenes depict the carrying of divine images to the circus, and commemorate the celebration of circus games by the deceased. (Height, 0.40m.; length, 2.05m.)

The process of incorporation of once foreign cults into the ‘official’ religion is most visible in the priesthoods held by members of the senatorial class. Until the end of the fourth century senators continued to be members of the four main priestly colleges, but they were in addition priests of Hecate, Mithras and Isis. For senators to associate themselves with these cults in Rome is an innovation of the fourth century, and this change has been interpreted in many modern accounts of the period as the emergence of a new religious ‘party’ in Rome: the senatorial supporters of Oriental cults, as against the upholders of ancestral Roman cults.52 There is, in fact, very little evidence to suggest such a split.53 Those who did not hold priesthoods of Oriental gods were not necessarily hostile to those who did, and conversely many of the priests of Isis, Hecate and Mithras were also members of at least one of the four ancient priestly colleges. The change is better seen as a trend toward assimilating into ‘traditional’ paganism cults in Rome which had not previously received senatorial patronage. Though Hecate and Mithras were not incorporated into the official calendar, some senators at least wished to place them within the bounds of religio. Faced with the new threat posed by imperial patronage of Christianity, senators redefined (and expanded) their ancestral heritage.

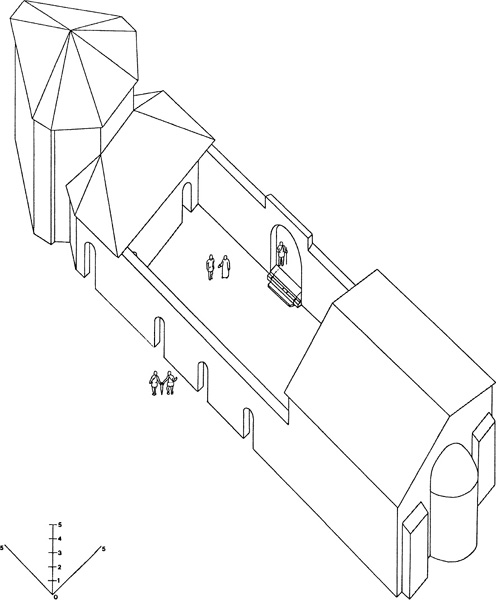

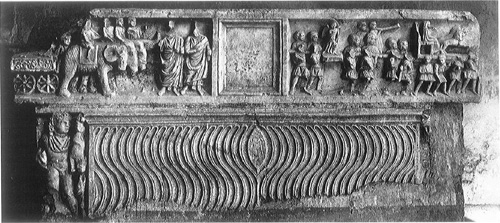

The process of change is also visible in cults long established in Rome which sometimes received new and heady interpretations. In the fourth century the cult of Magna Mater placed a new emphasis on the practice of the taurobolium.54 Inscriptions from the Vatican sanctuary record that some worshippers repeated the ritual after the lapse of twenty years; one claimed that he had been thereby ‘reborn to eternity’ – which seems to mark a radically new significance. Magna Mater by this date was not simply an ‘Oriental’ deity; she had after all received official cult in Rome for over five hundred years and was intimately connected with the destiny of Rome. The reinterpretation of the taurobolium in what was by now an ancient cult of Rome shows clearly how even such ancestral religions could still generate new meanings: in this case, a new intensity of personal relationship with the divine. The cult at the Syrian sanctuary on the Janiculum also seems to have changed during this period – losing much of its specifically Syrian focus.55 The sanctuary, which had been destroyed in the mid third century, was rebuilt in the fourth century. (Fig 8.4) Beneath the main cult statue of Jupiter Heliopolitanus a human skull was buried, which probably indicates an (illegal) human sacrifice to the deity.56 In the other main chamber was a large triangular altar surrounded by a number of sculptures: Dionysus in gilded marble, an Egyptian pharaoh of black basalt and a relief of the Seasons(?). Beneath the altar a male bronze idol entwined with a snake lay in a casket with numerous eggs broken over it, presumably to symbolize the rebirth of the initiate. In the second-century phase, so far as we know, the main deity was a strongly Romanized form of a Syrian god; in the fourth century, the cult incorporated elements of diverse origin: Syria, Greece, Egypt. And there is some evidence that the cult now offered a form of ‘rebirth’ to the initiate.57 The exact reasons for these changes in the cult of Magna Mater and of Jupiter Heliopolitanus are unclear; but a partial explanation at least must lie in the development of Christianity. Though old cults did not adopt elements of Christianity, they did adapt old procedures to offer a new eschatology and to enhance the involvement of the initiate.

Fig. 8.4 Reconstruction of the Syrian sanctuary on the Janiculum, Rome, fourth century A.D. The cult statue of Jupiter was in the apse at one end of the building (bottom right), and the triangular altar in the irregular-shaped room at the other.

Christianity did, however, pose a critical threat to the restructured traditional cults of Rome. When state funding of public rites in Rome was abolished and the altar of Victory removed from the senate house in A.D. 382, Symmachus as Prefect of the city of Rome wrote a lengthy memorandum to the emperor arguing for the restoration of the status quo. The traditional religious customs had served the state well for centuries; the altar of Victory was where senators swore oaths of loyalty to the emperor; the ancestral rites had driven the Gauls from the Capitol (an argument used also by Livy); the imperial confiscation of funding had caused a general famine in the empire. Symmachus’ arguments were directed not so much against Christianity, as in favour of toleration of the traditional cults: every people had their own customs and rituals, which were different paths to the truth. His memorandum was countered by two letters from Ambrose, bishop of Milan, to the emperor, which argued forcefully that it was the Christian duty of the emperor to fight for the church.58 After A.D. 382 with the partial exception of the (brief) reign of Eugenius (A.D. 392–394), the traditional cults did not receive the toleration Symmachus urged; and even Eugenius, himself a Christian, made only limited concessions to ‘paganism’. There was now only one true religio.

The argument between traditionalists and Christians extended to other contexts. One (Christian) poem, which probably dates either to the period of Symmachus’ memorandum or to the period of favour for traditional cults under Eugenius, attacked an unnamed Prefect of the city of Rome and consul for his participation in a wide range of pagan rituals, from Etruscan divination to the taurobolium.59 According to the poem, he supplicated Isis and mourned Osiris, he celebrated the festival of Magna Mater and Attis, with full trappings, including lions to draw the image of Magna Mater through the city, he held the festival of Flora, and his heir built a temple to Venus. For some, eclecticism was the way of truth; for others, like the author of this poem, it illustrated the vacuity of paganism.60 After the fall of Eugenius, Theodosius’ ban on sacrifices was more effectively applied, and the secular implications of the old calendar revised. The ancient distinction between ‘festival days’ dedicated to the gods and ‘working days’ on which (among other things) law-courts could sit was abolished. Now law cases could be heard on all days, except Easter, Sundays and the conventional breaks for the summer time and autumn harvesting and for imperial and other anniversaries. It was subsequently underlined that ‘the ceremonial days of pagan superstitio’ were not to be counted among the holidays. Traditional public festivals were not thereby banned, but they were officially marginalized in favour of Christian festivals. The last pagan senatorial priests are attested in the 390s: the Arval cult seems to have ended in the 340s, and the sanctuary was dismantled from the late fourth century onwards; the series of dedicatory inscriptions from the sanctuary of Magna Mater on the Vatican runs from A.D. 295 to 390; and the last dated Mithraic inscription from Rome is from A.D. 391 (slightly later than from elsewhere in the empire).61 Some Christians went on the offensive, destroying pagan sanctuaries, including sanctuaries of Mithras.62

But traditional religious rites were very tenacious, and their demise cannot be assumed from the ending of dedicatory inscriptions. Emperors through the fifth into the sixth century elaborated Theodosius’ ban on sacrifices – presumably in the face of the continuing practice of traditional sacrifice; while a pagan writer travelling up from Rome through Italy in the early fifth century observed with pleasure a rural festival of Osiris.63 In Rome the death of Symmachus in A.D. 402 was commemorated by two pairs of small ivory panels with strongly traditional imagery (a woman offering incense on an altar; another woman holding inverted torches, a sign of mourning, in front of a flaming altar), and a few years later the old ways were revived at a time of crisis: during the siege of Rome by the Goths (A.D. 408–9), when Christianity was not obviously helping, the Prefect of the city, after meeting diviners from Etruria, attempted to save the city by publicly celebrating the ancestral rituals with the senate on the Capitol.64 Around A.D. 430 a Roman writer, Macrobius, sought to recreate the religious learning and debate of the age of Symmachus, a generation before, in a long academic dialogue (including Symmachus himself as one of the ‘imaginary’ speakers) that centres on the interpretation of Virgil’s Aeneid, but also covers a vast range of classical culture and learning, from the jokes of the emperor Augustus to the different varieties offish.65 But most striking of all (given the date of its composition) is the complete exclusion of Christianity – an exclusion which acted to align classical culture and traditional religion.

This was not the dead hand of antiquarianism. We saw in our Preface how, even at the end of the fifth century A.D., the Lupercalia was still being celebrated in the city – by pagans and Christians; and how the bishop of Rome found it necessary both to argue against the efficacy of the cult (as some Christian writers had done for three hundred years) and to ban Christian participation.66 We wondered then, at the very start of our exploration of Roman religions, how we should interpret his action; how we should understand the significance of this (or any) pagan ritual over its history of more than a thousand years; or what the Lupercalia could possibly have meant in the Rome of Gelasius.

One thing is clear enough. The action of Christian bishops did not mean the ending of the old festivals, either at Rome or elsewhere in the empire.67 It was not simply a question of ‘paganism’ successfully resisting Christianity. There is, after all, no reason to assume that those who continued to watch the scantily clad young men race round the city thought of themselves as ‘non-Christian’. The boundary between paganism and Christianity was much more fluid than that simple dichotomy would suggest and much more fluid than some Christian bishops would have liked to allow. Fixing the boundary raised all the issues of interpretation that came with living in a self-consciously historic culture: could, in short, the heritage of Roman tradition, its places and rituals, be accommodated within a Christian context? Could Romulus and Numa and the other heroes of early Rome, could the rituals and institutions that were inextricably attached to their names, ever simply be excluded from the cultural inheritance of those who counted themselves Romans – whether Christian or not?68