Appendix D: Preparing for Further Psychology Studies1

This appendix was written by Jennifer Zwolinski, University of San Diego.

In Module 3, you learned about the work that different types of psychologists do and where they do it. Here you will find answers to important questions about pursuing the study of psychology: Will psychology be the right college major for you? What are the various levels of psychology education, and what kinds of jobs are available at those levels? What are some ways you can improve your chances for college success, and for admission to graduate school?

The Psychology Major

What Could You Do With a Degree in Psychology?

Lots! As a psychology major, you would graduate with a scientific mindset and an awareness of basic principles of human behavior (biological, developmental, mental disorder–related, social). This background would prepare you for success in many areas, including business, helping professions, health services, marketing, law, sales, and teaching. You could even go on to graduate school for specialized training to become a psychology professional.

How Do You Know If Psychology Is the Right Major for You?

To see if you would be well matched with a major in psychology, start by considering the questions below.

Do you:

- enjoy learning about the ways we think and behave, and why?

- appreciate the value of applying the scientific method to answer questions?

- have an interest in a career that requires interpersonal skills?

- want to learn critical thinking and analytical skills?

- want to learn communication and presentation skills?

- want to gain computer skills in data processing, and research methodology skills such as assessment and statistics?

- want to work in human or animal services?

- have a desire to apply psychological principles to understand or solve personal, social, organizational, or environmental problems?

If you answered “yes” to most or all of these questions, then psychology may be the right major for you.

How Popular Is the Psychology Major?

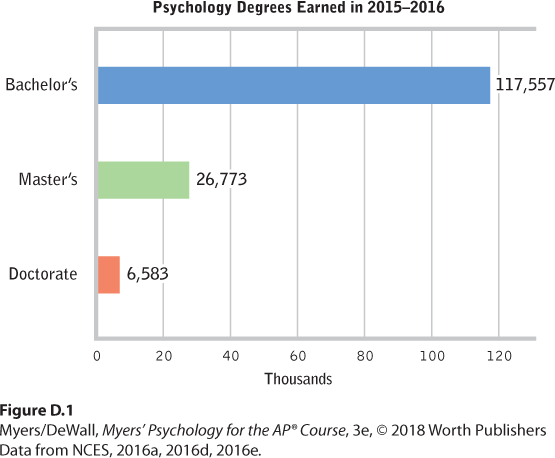

Psychology is a very popular major. In 2014–2015, psychology was the fourth most popular major—6 percent of all degrees conferred. Business (19 percent), social science and history (11 percent), and health professions and related programs (8 percent) occupied the top three spots (NCES, 2016a). In 2015, more than 117,000 psychology majors graduated with a bachelor’s degree from U.S. colleges and universities (NCES, 2016a) (Figure D.1).

Figure D.1 Number of psychology degrees conferred by level of degree: 2015–2016

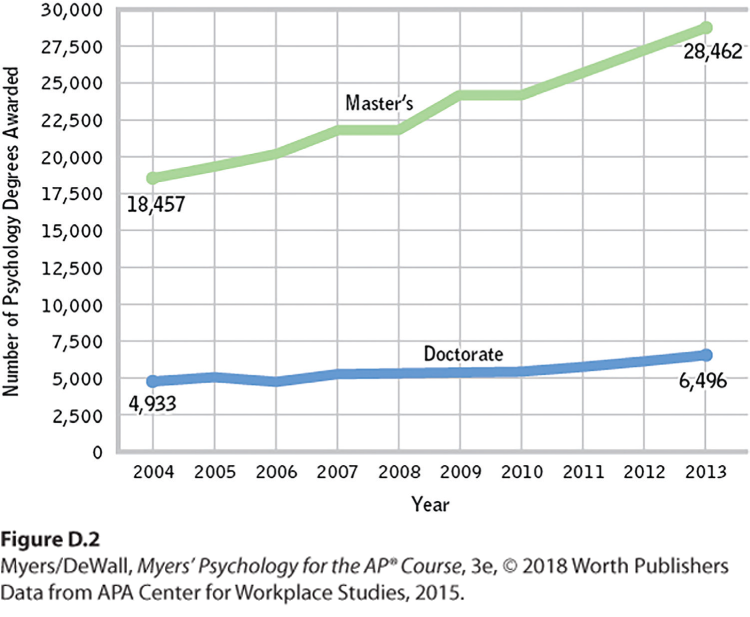

Given that this number has been steadily increasing since 1970 (NCES, 2016a), it is very likely that psychology will remain a popular major among undergraduate students. The popularity of psychology is observed at the graduate level as well. Over the last decade, the number of graduate degrees in psychology has increased dramatically—by 32 percent at the master’s level and 54 percent at the doctoral level (APA Center for Workplace Studies, 2015) (Figure D.2). As of 2013, of the 2.5 million workers whose highest degree was in psychology, approximately 1.4 million of them held a bachelor’s degree (Christidis et al., 2016a).

Figure D.2 Number of psychology master’s and doctoral degrees awarded by year: 2004–2013

Who Is Studying Psychology at the Undergraduate and Graduate Levels?

In 2015, a full 77 percent of the graduating psychology majors with bachelor’s degrees were women. In that same year, approximately 79 percent of master’s degree recipients were women (NCES, 2016b), and 75 percent of doctorate recipients were women (NCES, 2016c). Although 75 percent of all psychology doctorate recipients in 2015 were Caucasian, since 2005, the racial/ethnic diversity of doctorate recipients has grown, with a 12 percent increase among Black/African Americans, a 36 percent increase among Hispanics/Latinos, and a 46 percent increase among Asians (Christidis et al., 2016b).

What Are the Main Reasons That Undergraduate Students Choose to Study Psychology?

One study found that the number one reason psychology majors chose their major was a positive experience in their Introduction to Psychology class (Marrs et al., 2007). Other research has found that the top five reasons students choose a psychology major are that it provides the ability to help others, incorporates interesting subject matter, produces a better understanding of self and others, includes good career or salary potential, and offers the ability to conduct research (Mulvey & Grus, 2010).

What Types of Skills Would You Learn as a Psychology Major?

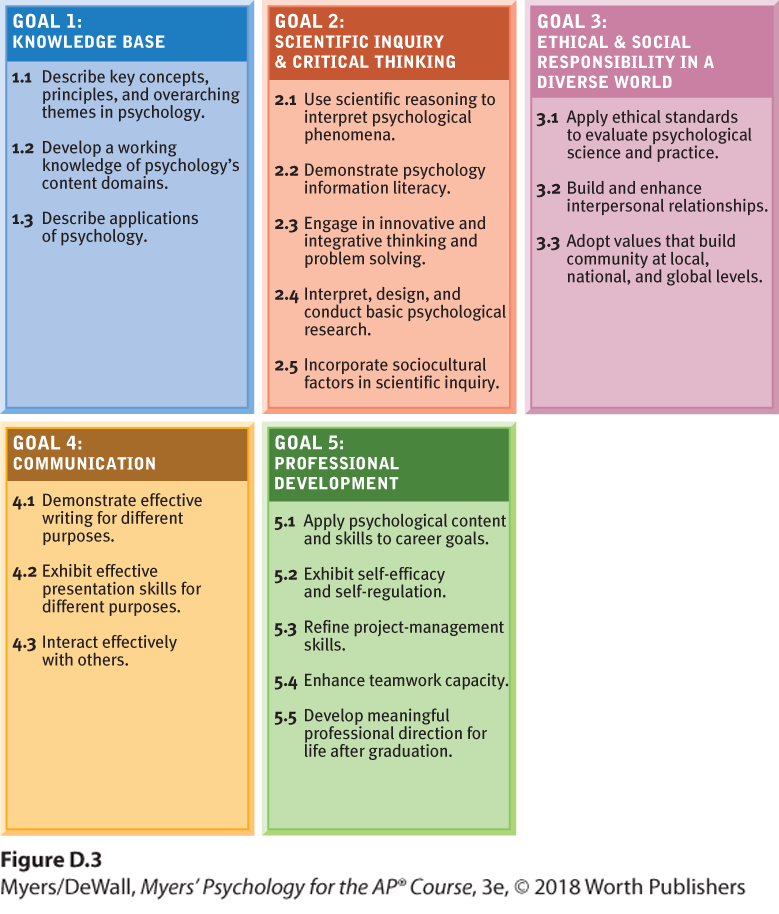

The wide range of skills that psychology majors develop makes this major a “premier choice” for versatile career preparation (Halonen, 2014). This skill set is guided by the American Psychological Association’s (APA) learning goals and outcomes for psychology majors (Figure D.3).

Figure D.3 APA Guidelines for the Undergraduate Psychology Major: Learning Goals and Outcomes

(APA, 2013. For complete Guidelines, see apa.org/ed/precollege/about/undergraduatemajor.aspx)

Across all occupations, the skill set that twenty-first-century employers value includes social perceptiveness, reading comprehension, critical thinking, and speaking and active listening skills (Carnevale & Smith, 2014). These skills align with APA’s learning goals and outcomes (Figure D.3), which means that psychology majors will be well prepared for numerous professional opportunities and a range of graduate training options. In addition to exceptional interpersonal and communication skills, psychology majors develop a number of methodological skills that result from the focus on the scientific study of human and animal behavior. The study of statistics and research methodology contributes to a scientific mindset that emphasizes exploring and managing uncertainty, critical thinking and analytical skills, and logical thinking abilities. The ability to analyze data using statistics, conduct database searches, and integrate multiple sources of information are helpful in a number of professional settings. Prospective employers appreciate the excellent written and verbal communication skills among students who present their research projects at conferences and master APA style.

Career Options with a Degree in Psychology

What Could You Do With a Bachelor’s Degree in Psychology?

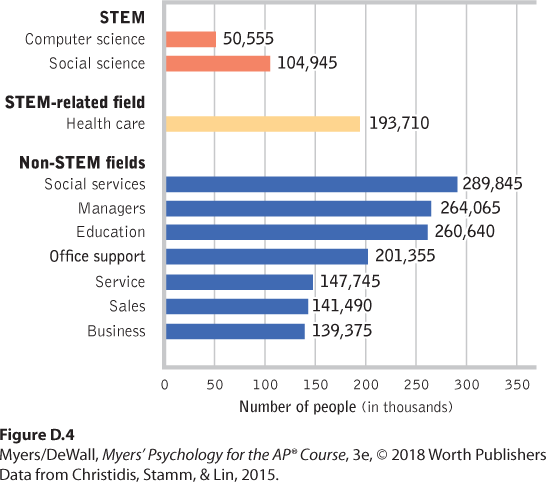

A psychology major would prepare you for many possible career paths. About 40 percent of students with a bachelor’s degree in psychology attend graduate school or receive professional training, which means the majority of psychology majors will be in the job market after graduation (Halonen, 2014). About 10 percent of Americans with a psychology bachelor’s degree work in STEM occupations (science, technology, engineering, and math), with over half of that group working in the social sciences. Another 10 percent work in STEM-related occupations, with most of that group working in health care (Christidis et al., 2015) (Figure D.4). The remaining 80 percent work in non-STEM fields (Christidis et al., 2015). Most individuals with a bachelor’s degree in psychology find work in business administration, sales, or education (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2015), with many others working in public affairs, the service industries, and computer programming (APA, n.d.). Popular occupations include employment counselor, interviewer, personnel analyst, probation officer, or writer (APA, n.d.). If you choose to work more directly in the field of psychology, a bachelor’s degree will qualify you to work as an assistant to psychologists, researchers, or other professionals in community mental health centers, vocational rehabilitation offices, and correctional programs (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2015).

Figure D.4 Where do people work with a bachelor’s degree in psychology?

A second option for psychology majors after graduation is to pursue a graduate master’s or doctorate degree in psychology. (More on this below.)

A third option is to pursue advanced training in other disciplines such as law, business, education, or medicine.

Drew Appleby provides a list of 300 careers that would be of interest to psychology majors (2016)—including those pursuing advanced degrees. The list includes links for more information about professional responsibilities, salaries, and job outlook for each of these positions. (See teachpsych.org/psycareer.)

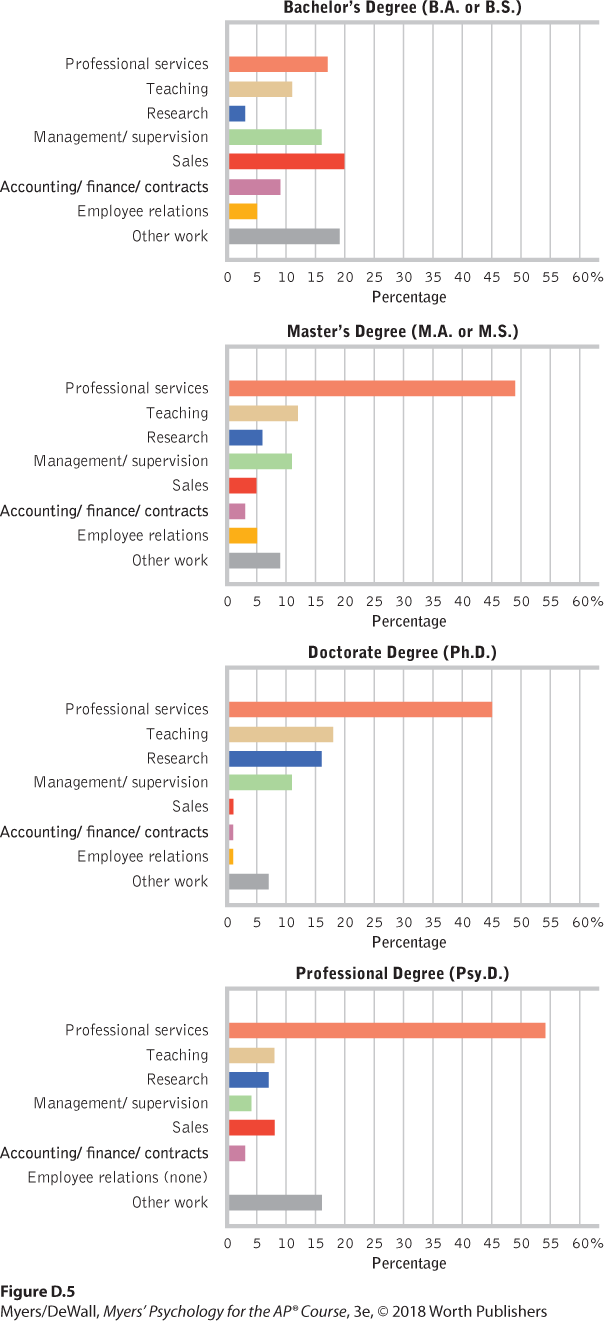

According to 2013 data from the National Science Foundation, career paths differ depending on the type of psychology degree that individuals received (Figure D.5). For example, about half of individuals with graduate degrees in psychology worked in professional services, which includes positions in health care, financial and legal services, and counseling. In comparison, whereas some individuals with a bachelor’s in psychology worked in professional services, many of them worked in sales, management/supervision, and other work fields (Stamm et al., 2016).

Figure D.5 Where do people work with varying psychology degrees?

How Can You Maximize Your College Success and Later Job Prospects With a Major in Psychology?

Betsy Morgan and Ann Korschgen (2009) offer the following helpful tips for increasing your chances of getting a job after graduation. Many of these tools will benefit students who plan to apply to graduate school as well.

- Get to know your instructors. Talk with them about the field of psychology and get their advice on your career plan. Ask them to support you on an independent study internship or research project. By learning more about your skills and ambitions, faculty members can help you accomplish your goals. This may even result in an enthusiastic reference for future employment.

- Familiarize yourself with available resources. Talk to alumni and senior students. Your college’s Career Services can help you identify and market your job skills and emphasize your knowledge and abilities in your resume. They can also help you to network with other alumni who are working in your area of interest who can help you to prepare for the career that you want. I’ve included some other helpful online resources at the end of this appendix.

- Volunteer some of your time and talent to campus or community organizations, such as Psi Chi (the national honor society in psychology) or your college’s psychology club. In addition to showing that you are an active citizen in your department, you will gain important skills, such as meeting and event planning, how to work with a group, and improved communication skills, all of which enhance your marketability.

- Participate in an internship experience. Many employers want students to gain relevant experience outside the classroom. Internships are offered during the school year as well as the summer break. Some are paid and others are not, but you may be able to earn course credit while completing your internship. In addition to gaining relevant work experience before you graduate, you will increase your network of mentors who can provide supervision and support for your career goals as well as letters of endorsement when you apply for jobs.

- Take courses that support your interests and plans. Although the psychology major offers a range of skills that will benefit you in the job market, don’t assume the psychology curriculum will offer all the skills necessary to get a job in your area of interest. Add courses to increase your knowledge base and skills. This will also show prospective employers that your specific interests are in line with the demands of the job.

If you work hard now and plan ahead, you may be able to avoid regrets later. A Pew Research study asked college graduates whether (1) studying more, (2) starting their job search earlier, (3) choosing a different major, or (4) gaining more job experience during college would have helped them to get a better job (Pew Research Center, 2014). About three quarters of the group reported that doing at least one of one of these things would indeed have helped them to earn a better job. Graduates’ number one regret? Not getting enough job experience during college.

What Type of Salary Could You Expect With a Degree in Psychology? Would a Graduate Degree Increase Your Income Potential?

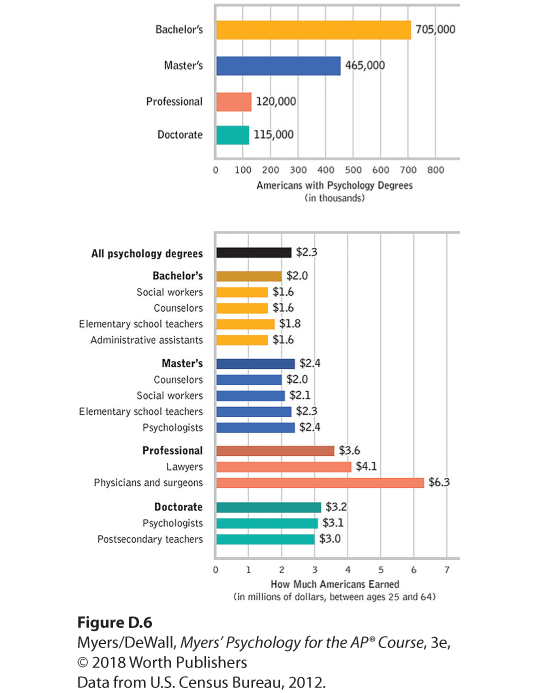

In 2013, the average starting salary for a BA degree recipient was $35,108 (NCES, 2015). By comparison, the 2013 average starting salary for master’s degree recipients was $51,935, and for doctoral recipients was $53,458 (NCES, 2015). In this same year, the median salary for full-time, doctoral-level psychologists was $80,000 (Lin et al., 2017). The highest salaries were for individuals with doctorates in general psychology ($110,000) and industrial/organizational psychology ($108,000), with the lowest salaries for individuals with doctorates in educational psychology ($73,000). Psychologists with a doctoral (Ph.D.) degree had a higher median salary than those with a professional (Psy. D.) degree ($84,000 vs. $70,000) (Lin et al., 2017). Across a lifetime, individuals with a psychology bachelor’s are expected to earn $2,001,000, whereas individuals with a doctorate in psychology are expected to earn $3,157,000 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2012) (Figure D.6). Clearly, earnings tend to increase with education, and higher levels of education will almost always yield greater financial rewards over the course of a career (Carnevale, 2016).

Figure D.6 Salary comparison for psychology degree pathways

Among early-career psychologists, clinical neuropsychologists reported the highest median first year salary of $72,500, followed by clinical child psychologists ($65,850), and clinical psychologists and industrial/organizational psychologists (both $65,000) (Doran et al., 2016).

Psychologists rank number seven (tied with medical scientists) among the top-paying occupations for those with doctoral degrees. The lifetime salary in 2009 dollars was $2,515,000 for graduate level psychologists, compared to the average lifetime salary for all doctoral occupations of $3,252,000 (Carnevale et al., 2011).

Of course, earning potential should not be the only reason that individuals choose a major. Job satisfaction is another important consideration.

What Kind of Job Satisfaction Could You Expect If You Work in a Psychology Field?

In 2015, an impressive 88 percent of U.S. employees reported that they were overall satisfied with their jobs, marking the highest level of job satisfaction in the last 15 years (Society for Human Resources Management, 2016). In a study of 27,000 Americans, the most satisfying jobs were those that involved “caring for, teaching, and protecting others, and creative pursuits” (Smith, 2007, pp. 1–2). Most of the occupations with the highest-ranking happiness levels involved helping others, using technical and scientific expertise, or using creativity (pp. 1–2). A bachelor’s degree in psychology can increase the likelihood that you will be working in a job that fosters these skills (Landrum, 2009).

High levels of job satisfaction have also been observed among individuals who attend graduate school in psychology. In 2009, a full 72 percent of new doctoral recipients indicated that their primary occupation was their first choice. Most new graduates with a Ph.D. are fairly satisfied with their current position in terms of salary, benefits, opportunities for personal development, supervisors, colleagues, and working conditions (Michalski et al., 2011).

Postgraduate Degrees

Why Should You Consider Attending Graduate School in Psychology?

If you choose to earn a graduate degree in psychology, you will be in good company. About 45 percent of those with a bachelor’s degree in psychology or social work go on to graduate school (Carnevale et al., 2015). Those with graduate degrees in psychology earn 33 percent more, on average, than psychology majors with only a bachelor’s degree (“By the numbers,” 2016). In addition to a higher salary and strong job satisfaction, a graduate degree in psychology will give you proficiency in an area of psychological specialization and increased opportunities to work in diverse areas of psychology. Also, individuals with the highest degrees in psychology have the highest rates of full-time employment (Christidis et al., 2016a).

Job prospects in the field of psychology are much better for individuals with graduate degrees. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2015), job prospects will be best for those in clinical, counseling, or school psychology positions for candidates with a doctoral or education specialist degree and postdoctoral work experience. Individuals with a master’s degree will face keener competition for positions in psychology than those with a doctoral degree.

Employment for psychologists is expected to grow 19 percent from 2014 to 2024, which is faster than average for all occupations. Employment will grow because of increased demand for psychological services in schools, hospitals, social service agencies, and mental health centers (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2015).

What’s the Difference Between a Master’s Degree and a Doctorate Degree in Psychology?

Both degrees would prepare you for more specialized training in psychology and increase your job opportunities in the field of psychology beyond the bachelor’s degree.

A master’s degree in psychology requires at least two years of full-time graduate study in a specific subfield of psychology. In addition to specialized course work in psychology, requirements usually include practical experience in an applied setting or a master’s thesis reporting on an original research project. You might acquire a master’s degree to do specialized work in psychology. As a graduate with a master’s degree, you might handle research and data collection and analysis in a university, government, or private industry setting. You might work under the supervision of a psychologist with a doctorate, providing some clinical service such as therapy or testing. Or you might find a job in the health, government, industry, or education fields. You might also acquire a master’s degree as a stepping stone for more advanced study in a doctoral program in psychology, which would expand the number of employment opportunities available to you.

It takes more time to complete a doctoral degree in psychology, relative to a master’s degree. Among graduates who earned a research doctorate (Ph.D.) in psychology in 2013, the average time to degree completion was 7 years after starting graduate school, or 8.3 years after finishing their bachelor’s degree (Lin et al., 2017). The doctoral degree you choose to pursue would depend on your career goals. You may choose to earn a doctor of philosophy (Ph.D.) in psychology if your career goals are geared toward conducting research, or a doctor of psychology (Psy.D.) if you are more interested in becoming a practicing clinician. Training for the Ph.D. culminates in a dissertation (an extensive research paper you will be required to defend orally) based on original research. Courses in quantitative research methods, which include the use of computer-based analysis, are an important part of graduate study and are necessary to complete the dissertation. Psy.D. training may be based on clinical (therapeutic) work and examinations rather than a dissertation. Many psychologists who earn a Ph.D. in clinical or counseling psychology conduct research and practice as psychotherapists. If you pursue clinical and counseling psychology programs, you should expect at least a one-year internship in addition to the regular course work, clinical practice, and research. It is important to note, however, that psychologists with Psy.D. degrees are not the only ones who work as psychotherapists; some types of counselors and therapists may practice with only master’s degrees.

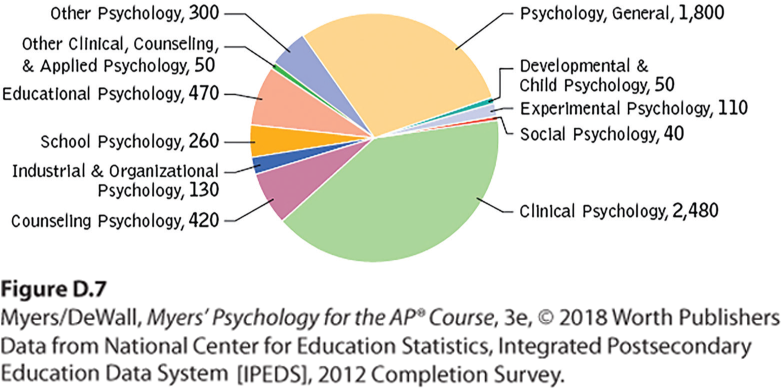

Figure D.7 lists by subfield the Ph.D.s earned in the United States in 2012, the most recent year for which these data are available. Among the doctorates awarded in the 2011–2012 academic year, the most popular subfield was clinical psychology, followed by general psychology. Of these doctorates, the majority were classified as research/ scholarship (74 percent), with fewer designated as professional practice (24 percent) or other types (1 percent) (APA Center for Workplace Studies, 2014).

Figure D.7 Number of doctorate degrees awarded by psychology subfield in 2012

Preparing Early for Graduate Study in Psychology

Competition for openings for advanced degree programs in psychology is keen. If you plan to go to graduate school after college, there are a number of things you can do in advance to maximize your chances of gaining admission to the school of your choice.

The first step is to take full advantage of your opportunities in high school. By enrolling in challenging elective courses and working hard to develop an academic skill set, you will have paved the way for success in college. Successful students also take the time to learn effective study skills and to establish disciplined study habits. Involve yourself in extracurricular activities, gain some experience in the world of work by taking on a part-time job, and look for opportunities to volunteer in your school and community. In addition to helping you grow as a person, becoming a well-rounded student with high standards helps you to earn scholarships and increases your chances of being accepted by the colleges and universities of particular interest to you.

During your first year at college, continue to maximize opportunities and obtain the experience needed to gain admission to a competitive program. Kristy Arnold and Kelly Horrigan (2002) offer a number of suggestions to facilitate this process:

- Network. Get to know faculty members and the psychology department by attending activities and meetings. This will be especially helpful when you apply to graduate school or for a job, because many applications require two to three letters of reference. Become involved in psychology clubs and in Psi Chi, the national honor society in psychology. These meetings will help you connect with other students who have similar interests and expose you to a broader study of the field.

- Become actively involved in research as early as possible. Start by doing simple tasks such as data entry and data collection, and over time you will be prepared to conduct your own research project under the supervision of a research mentor. Consider applying for summer research positions through your university or from other organizations such as the American Psychological Association Summer Science Fellowship program or the National Science Foundation Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) program, which will test your interest in academic careers and build your skills for future study in psychology.

- Volunteer or get a job in a psychology-related field. Getting involved in this way will demonstrate your willingness to apply psychological concepts to real-world settings. Further, it will showcase your ability to juggle a number of tasks successfully, such as those required for work and school—an important skill for graduate school success.

- Maintain good grades and prepare early for the GRE. Demonstrate your ability to do well in graduate school by successfully completing challenging courses, especially those related to your interests. (See “Use Psychology to Become a Stronger Person—and a Better Student” in Module 2, and the final section in Module 33 for tips on how to do well in this and other courses, and how to improve your retention of the information you are learning.) In your junior year of college, you should begin studying for the Graduate Record Exam (GRE), the standardized test that applicants to graduate school must complete. Many graduate programs in psychology require both the general GRE and the psychology subject tests. If you start preparing early and maintain high grades, you will be ready for success in your graduate school application and study.

For More Information

How Can You Learn More About the Psychology Major and the Field of Psychology?

- Talk with as many people as possible who have experience in the discipline of psychology. Your psychology teacher or school counselor may have some tips. Try to learn about opportunities to contact psychology majors, graduate students in psychology, psychology instructors and advisors, and other professionals who trained in psychology or who work in the field.

- Read books, such as those listed at the end of this appendix.

- Take advantage of online resources, which can help you to determine whether you would be well matched for a major and a career in psychology.

- Watch online videos showcasing different careers in psychology, such as those found at drkit.org/psychology.

- Play the Career Interest Game (career.missouri.edu/career-interest-game).

- Get more information about specific jobs in psychology from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the Occupational Information Network (O*NET), or the Occupational Outlook Handbook (OOH).

- Visit the websites of the American Psychological Association (apa.org) and Association for Psychological Science (psychologicalscience.org). The APA has a lot to offer high school students who are interested in learning more about psychology. To learn more about membership at the high school level (which includes subscriptions to APA journals and mobile apps), visit apa.org/membership/hs-student/index.aspx. You can also become a member of the Psychology Student Network (apa.org/ed/precollege/psn/index.aspx).

- Learn more about the national honor societies in psychology, Psi Chi and Psi Beta.

What Are Some Books That Can Help You to Learn More About the Major, Careers, and Graduate School in Psychology?

American Psychological Association. (2017). Graduate study in psychology, 2016 edition. Washington, DC: Author.

Hettich, P., & Landrum, R. E. (2014). Your undergraduate degree in psychology: From college to career. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kuther, T., (2016). The psychology majors handbook (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Wadsworth Cengage.

Landrum, E., & Davis, S. (2013). The psychology major: Career options and strategies for success (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

Morgan, B., & Korschgen, A. (2014). Majoring in psychology? Career options for psychology undergraduates (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Silvia, P. J., Delaney, P. F., & Marcovitch, S. (2016). What psychology majors could (and should) be doing: A guide to research experience, professional skills, and your options after college (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Sternberg, R. (2016). Career paths in psychology: Where your degree path can take you (3rd ed). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.